– 3 –

Increasing American Community Survey Participation Through Improved Respondent Communication

The two days of the Workshop on Improving the American Community Survey (ACS) differed greatly not only in content but also in the overall nature of the presentations. The Day 1 material on the nexus of administrative records and third-party data with survey data necessarily drew extensively on argument through analogy; to date, no example has surfaced of a major federal household survey whose complete operational workings have been revised to account for wider use of administrative data, so there is no way to really distill “lessons learned” from past tests and experiments. Day 2 of the workshop turned to the communication processes inherent in conducting the ACS—much firmer and more familiar ground, on which the Census Bureau and the ACS have trod for decades. But, as the workshop day would make clear, firmer and more familiar ground is not easy ground, and decisions on communication contacts and strategies can have major impacts on the quality of ACS data, the burden on its respondents, and its costs.

More succinctly, it is very much as Warren Brown (Cornell University and planning committee chair) put it, with mock exaggeration, in welcoming the audience to Day 2 of the workshop: If Day 1 is very colloquially about how “we don’t need the respondents” in light of the new alternative-data world, this

second day of the workshop is very much the flip-side. The respondent is always needed in the survey context, and so efforts to make the respondent experience as positive and effective as possible are critical to success.

3.1 OVERVIEW OF RESPONDENT CONTACT STRATEGIES

In developing the workshop, the planning committee asked to begin the session on respondent communication with a de novo description of what ACS respondents actually see and what messages they are actually given. For contrast, this overview of the ACS process was followed up with a review of Statistics Canada’s implementation of its “wave methodology” for respondent interaction and its refinement over the past several iterations of the quinquennial Canadian census.

3.1.1 Census Bureau’s Current ACS Mail and Contact Strategy

The Census Bureau staff distributed copies of the full ACS mail-material “kit” as it currently stands to the workshop audience, and Dorothy Barth (U.S. Census Bureau) commented that she was the duly appointed “tour guide” through the ACS’s current mail and contact strategy. She began with a reminder of the basic numbers and scope of the ACS sample: The ACS is sent to approximately 3.5 million randomly selected addresses (housing units) per year, with the sample divided into 12 monthly “panels” (and so contain roughly 295,000 addresses) that are each nationally representative in themselves. Each panel is then subdivided into 24 nationally representative “methods panel groups” of about 12,000 addresses each. This segmentation gives the Census Bureau and the ACS Program flexibility to allocate a small number of methods panel groups to experimental questionnaires or methods without jeopardizing the bulk of ACS production. Barth said that it also allows the Census Bureau to perform tests more quickly than if a new, separate sample had to be drawn.

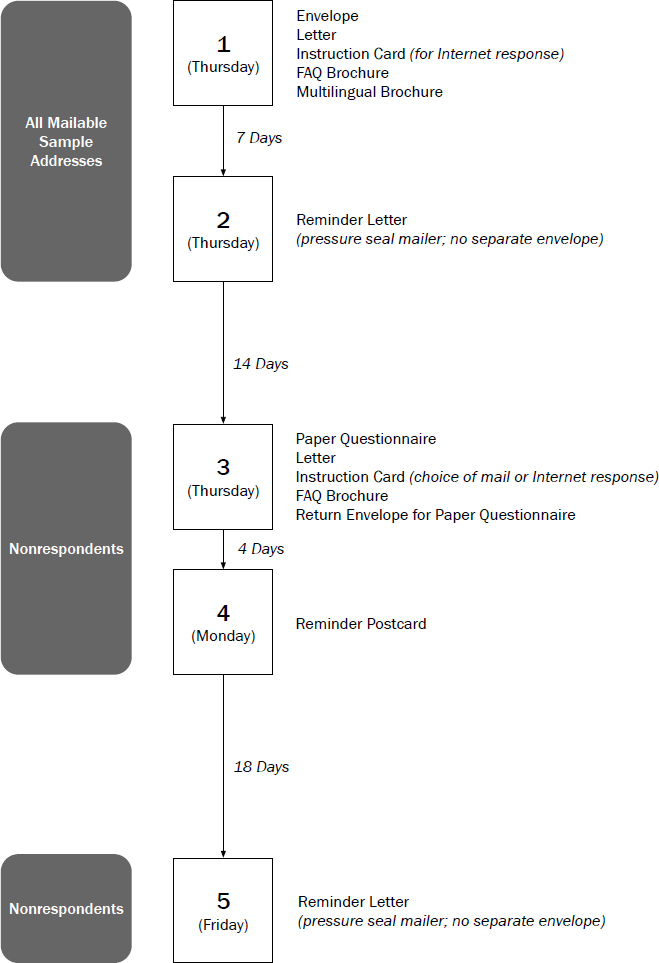

As depicted in Figure 3.1, the ACS currently makes use of 5 separate mailing attempts over 43 days before a sample address is eligible for a field interview in nonresponse follow-up. All mailable addresses1 receive Mailings 1 and 2; household addresses that have responded are removed from the mail stream for Mailings 3 and 4; and, after the longest time gap in the cycle, only those households that still have not responded are sent Mailing 5. Data collection in

___________________

1 If an address is not deemed mailable, then it may still be put into processing for personal visit and completion of the interview by computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI). Subsequent to the workshop, the Census Bureau announced (in resubmitting the ACS for review under the Paperwork Reduction Act) that it will make the Internet response channel for the ACS applicable to all addresses, not just those in the mail stream, beginning in July 2019. Hence, a Census Bureau representative will still attempt personal visits, but they will give respondents the option to complete the ACS questionnaire online (Federal Register, October 16, 2018, p. 52190).

the ACS is continuous in the sense that the mailing cycle shown in Figure 3.1 is repeated with the next monthly panel of addresses with each new month, even though the final mailing and the field interviewing for the previous month continues while mailings go out to the current month’s sample.

As Barth demonstrated, Mailing 1 consists of:

- The outer envelope, austere and official-looking and prominently featuring “The American Community Survey” and “YOUR RESPONSE IS REQUIRED BY LAW” in a box to left of the address label window.

- An Internet Instruction Card, on which is sprayed the address label for the respondent household. The card is printed on 10.75"×5.6" card stock, with the front side (containing the address label) giving directions to the http://respond.census.gov/acs website in English; importantly, it is the address label that also contains the “user ID” necessary to complete the survey online. The reverse side of the card gives the same Internet instructions in Spanish, though it is spaced differently because of the absense of the address label on that side.

- The letter reproduced in Figure 3.2, informing the recipient that they have been selected for the ACS—or, more technically, that their address has been so selected. The initial letter includes some statements about the benefits of completing the ACS as well as some confidentiality messaging, Barth noted.

- An FAQ Brochure, in trifold format on 14"×8.5" glossy stock, with short one- or two-paragraph answers to 6 questions:

- “What is the American Community Survey?”

- “How do I benefit by answering the American Community Survey?”

- “Do I have to answer the questions on the American Community Survey?”

- “How will the Census Bureau use the information that I provide?”

- “Will the Census Bureau keep my information confidential?”

- “Where can I find more information about the American Community Survey or get assistance?”

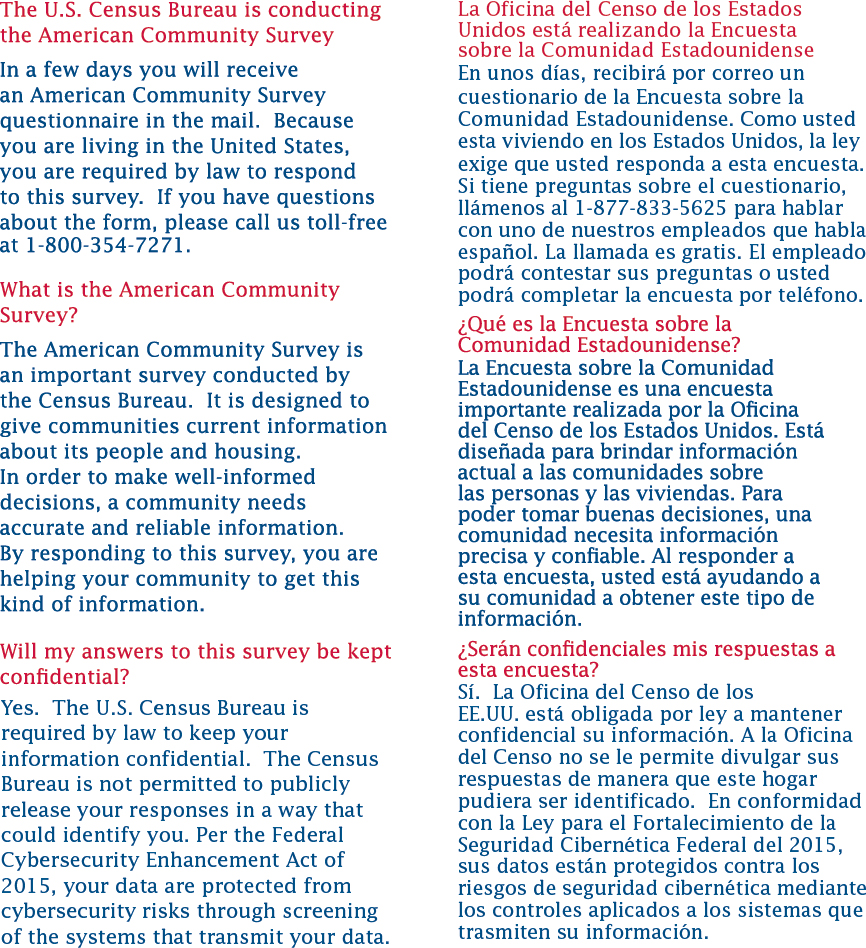

- A multilingual brochure, the English and Spanish panes of which are reproduced in Figure 3.3. It is printed on 14"×8.5" glossy stock, like the FAQ brochure, but it is folded in half twice to produce a thin brochure with 8 panes. The front “cover” pane signals that the brochure contains “Important Information from the U.S. Census Bureau”; the brochure’s panes show the text in Figure 3.3 rendered in Chinese, Vietnamese, Russian, and Korean (with the phone number given in the first paragraph of text varying by language, so that callers are routed appropriately).

Mailing 2, sent to all mailable addresses in the sample, is a single mailing piece, bearing the text shown in Figure 3.4 but with the text aligned slightly differently. Barth said that, on the strength of 2017 testing described later in the workshop (see Section 3.2.1), the Census Bureau found it beneficial to convert Mailing 2 into a one-piece “pressure seal mailer” rather than a standard letter-in-envelope. “Pressure seal” means that the document is folded over and the three exterior sides sealed, so that the respondent removes the edges (tearing along perforations) to open the document. Figure 3.4, from the Paperwork Reduction Act approval package for the ACS, retains the formatting as a standard letter; in the new and current production version of Mailing 2, demonstrated at the workshop, the greyscale “Security” box is positioned so that it aligns with the user ID/Internet instruction box—which Barth described as a further safeguard against anyone being able to discern the user ID without opening the mailer. Barth said that the pressure seal method was economical as well as advantageous in terms of promoting response; as she noted, the 8.5"×5.5" parcel (opening to a 7.5"×10" letter) strikes respondents as “looking ‘official’ ” and feels more important with the requisite tearing off of the perforations.

Two weeks are allowed to pass for responses to come in via Internet; those responding, mailable addresses are then culled from the list and the remaining nonrespondents are sent the questionnaire mailing package, Mailing 3. This mailing consists of:

- The outer envelope, which is again austere and official looking, with a window revealing the interior address label.

- The ACS questionnaire, a 28-page booklet measuring 10.25" square, formed by folding 7 10.25"×20.5" sheets in half and stapling. The address label is sprayed on the top half of the front cover of the questionnaire booklet, folded over, for insertion into the envelope. Barth drew attention to a small box at the lower left of that front cover that contains another mention of the availability of Internet response, an icon and mention of the number to call for telephone assistance, and limited Spanish translations of the same information. The lower right pane of the cover of the questionnaire begins the interview, asking for the current date, the name of the respondent, and the basic household count.

- The follow-up letter, depicted in Figure 3.5. This letter, accompanying the paper questionnaire, is the first mention of both primary response modes to the ACS (Internet or paper), Barth said. She added that it attempts to play up the statement of benefits of completing the survey, contains some confidentiality and cybersecurity information, and “warns” the respondent that there may be follow-up by phone or personal visit.

- An Internet and Mail Response Instruction Card, very similar to the Internet Instruction Card of Mailing 1—10.25"×5.6" card stock, similar colors, English on one side and Spanish on the other—but formatted

- The same FAQ Brochure as included in Mailing 1.

- An empty, postage-paid return envelope for the paper questionnaire (measuring 10.6"×5.75" to fit the folded booklet).

differently to mention possibility of completing and returning the paper questionnaire (and because it does not have to bear the address label, as it does in Mailing 1).

Mailing 4, sent only 4 days after Mailing 3, is a basic single-piece postcard measuring 6"×4.25", shown in Figure 3.6. Barth said that the card “basically reiterates what has already been said at this point” in the process, but “we’re kind of ratcheting things up” by putting the mandatory response clause in boldface type.

Finally, after 18 days, respondent households are again removed from the mail stream and the final Mailing 5 is sent to remaining nonrespondents. As described in Mailing 2, Mailing 5 has recently been switched from a standard letter-in-envelope to a pressure seal mailer. As depicted in Figure 3.7, the Mailing 5 letter is identical in size and structure to the Mailing 2 piece; Barth noted that it retains the boldface mandatory response language from Mailing 4.

Barth closed by commenting very briefly on the rest of the ACS data collection process. Prior to October 2017, some sample households that had not

replied by mail were made eligible for computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI); however, as of that month (and as mentioned previously at the workshop), CATI was eliminated as a response option due to escalating cost-per-interview. Barth said that the Census Bureau approximates that the elimination of CATI will lead to 10 million fewer calls per year to ACS sample households, an appreciable reduction in burden. Barth also said that, in the further interest of burden reduction without affecting quality, personal interviewing for the ACS is also done using fewer visits. She explained that each address is assigned a “burden score” ahead of time, based on the estimated ease of contacting the household, and a maximum number of permissible visits is set based on that score.

3.1.2 Contrast: Statistics Canada’s Wave Methodology Approach for Census/Survey Respondent Contacts

Canada is the world’s second largest nation in land area, with the majority of its population (35,151,728 measured in the 2016 census) concentrated in the urban areas of the south and the majority of its land mass characterized by rural and remote communities. Accordingly, Patrice Mathieu (Statistics Canada) noted in opening his remarks, Canada is challenging terrain for censustaking, as the nation does every 5 years (in years ending in 1 and 6). Mathieu observed that the Canadian census has emerged into a multimode data collection anchored to the fixed reference point of Census Day in May (May 10, in the 2016 census). The Canadian census permits self-response by either electronic or paper questionnaire from May through July, although the objective of the census contact strategy is to promote completion of most self-response in May. Field interviewing for nonresponse follow-up occurs in June and July of the census year.

First introduced in the 2011 Census of Canada, Statistics Canada’s “wave methodology” is a plan for sequencing the delivery of messages and survey materials that Mathieu noted is based on the work of Donald Dillman (member of the workshop planning committee). As Mathieu described it, the goal of the wave collection methodology is to encourage response via the Internet while ensuring a high level of self-response overall. As prelude to describing the methodology, Mathieu discussed the methodology’s proven effects, as shown in two tables. Table 3.1 illustrates the response rates by the different possible channels in the 2011 and 2016 Canadian censuses, while Table 3.2 focuses on Internet response from its beginning on a small-test basis in 2001 through the 2016 census. Mathieu noted that all national statistics offices and survey organizations are dealing with the general current trend for decreasing response rates to surveys, but Statistics Canada is pleased to see the opposite trend. Mathieu said that he believed that Canada’s 68.3 percent Internet response rate was the highest online take-up rate achieved in a census until New Zealand’s

Table 3.1 Collection Response Rates in the 2011 and 2016 Censuses of Canada

| Collection Rate | 2011 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actual | Planned | Actual | |

| Census Collection rate | 98.1% | 98.0% | 98.4% |

| Internet | 53.8% | 65.0% | 68.3% |

| Paper | 31.3% | 20.0% | 20.5% |

| Self-Response | 85.2% | 85.0% | 88.8% |

| Non-response follow-up (NRFU) | 12.9% | 13.0% | 9.7% |

| Workload at start of NRFU | 4.8M | 4.5M | 3.7M |

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Patrice Mathieu.

| Census | Response Rates | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Collection | Internet | Self-Response | |

| 2001 | 98.4 | — | 75.6 |

| 2006 | 96.5 | 18.3 | 78.5 |

| 2011 | 98.1 | 53.8 | 85.2 |

| 2016 | 98.4 | 68.3 | 88.8 |

NOTE: Internet collection was only done on a small-test basis in the 2011 census.

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Patrice Mathieu.

most recent census, but it is still a mark of pride—but he conceded that the number that Statistics Canada is most proud of is the 88.8 percent overall self-response rate.

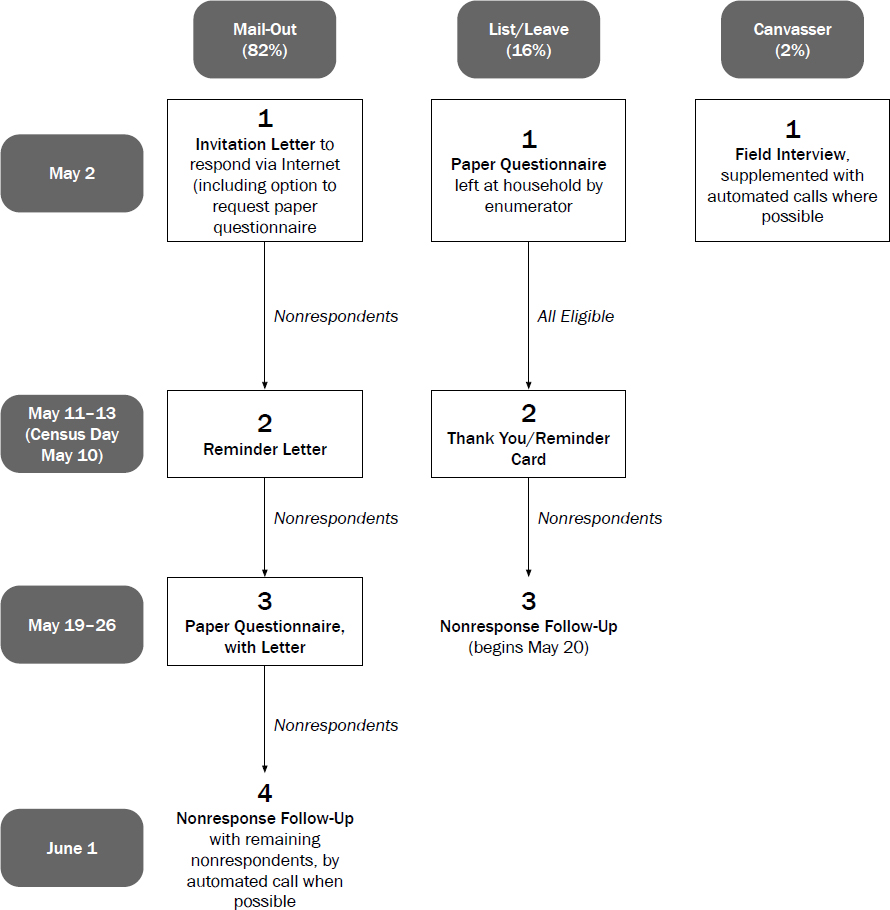

The wave methodology used by Statistics Canada in the 2016 census is illustrated in Figure 3.8; both it and Barth’s description of the cycle of ACS mailings (Figure 3.1) are redrawn slightly to be similar in style. Mathieu said that in 2016, the wave methodology “was applied more uniformly” than it had been in 2011; the earlier census had two different treatments that applied to mailout areas. In the 2016 census, there were three basic enumeration techniques used to collect the requisite information; the wave methodology focuses on the most frequently used technique, Mailout, which accounted for 82

percent of Canadian households in 2016 (and will ideally be closer to 88 percent in the 2021 census, Mathieu said). About 16 percent of households were in areas where mail delivery was deemed infeasible, typically because the mailing address could not be readily associated with a physical location (as for mail delivery to post office boxes rather than curbside). Households in these areas were enumerated through List/Leave techniques, in which a census enumerator would visit the household, add or update information about the address and its location, and leave a paper questionnaire package.2 However, under the wave methodology approach, List/Leave households are also prompted to complete the census online: List/Leave households receive an “adcard” as the second wave of contact, functioning dually as thanks to responding households and an invitation to reply electronically. The remaining 2 percent of households in the 2006 Canadian census are typically the most remote, hardest-to-contact areas, and mail delivery (or response) is wholly unviable as an option; these households are only contacted by enumerators and interviewed when contact is made, in what is dubbed Canvasser enumeration.3

The interior and exterior of the Wave 1 mailing are shown separately in Figure 3.9 and Figure 3.10. Mathieu said that Statistics Canada needed a cost-effective way to process and send a planned 13.3 million Wave 1 letters and 8.4 million Wave 2 reminder letters—the latter “on demand,” in the sense of removing responding addresses from the mailflow—all with variable-imaged addresses and secure Internet access codes. To satisfy all those constraints, Mathieu noted that they chose a self-mailer approach, very similar to the pressure seal mailer now in use with the ACS. Just as Barth noted that U.S. research suggests that the pressure seal mailer looks more “official” to respondents, Mathieu observed that “respondents appear to pay more attention” to the self-mailer format than a traditional envelope.

Figures 3.9 and 3.10 also illustrate two subtle design points:

- Statistics Canada adheres to a rigid color palette in its printed materials and mailings and, in particular, Mathieu said that the yellow hue illustrated on the mailer’s exterior has become well known as the “census color” in Canada. He said that the color itself has become a recognized, accepted symbol of the agency and the census effort.

___________________

2 Canada’s List/Leave technique is analogous to the Update/Leave type of enumeration employed in recent U.S. censuses. In the subsequent discussion period, James Wagner (University of Michigan) elicited clarification from Mathieu about the designation of enumeration type in Canada. As in the U.S. census, the determination is based on area characteristics and is applied to whole, small areas like blocks or tracts; it is not assigned at the household/dwelling level. In the line of questioning, Mathieu clarified that the core enumeration types will continue in 2021 and that the hope is to effect a 6-percent swap: elevating from 82 to 88 percent Mailout and decreasing from 16 to 10 percent List/Leave.

3 Canadian Canvasser enumeration is analogous to the Update/Enumerate type of enumeration, and variants thereof such as Remote Alaska enumeration, used in recent U.S. censuses.

- Mathieu conceded that the Canadian census mailings look “busy”—necessarily so, because they must be bilingual, English and French. Laughingly, Mathieu noted that this is a challenge because expressions in French “always take longer” to render in French and so are frequently more difficult to fit in available space than their English counterparts, to the point that Canadian questionnaires and materials are commonly designed first in French to ensure that everything will fit. But that also serves as a strength of sorts—knowing that the material must be rendered in duplicate forces rigor and prioritization in presentation.

Mathieu presented the text of the letters used in the three wave mailings, as shown in Box 3.1.4 He said that two waves of qualitative studies (as well as the results of census pretesting) were conducted to hone and establish the content of each letter. This work established the principal goals of the letters:

- To promote the Internet response channel;

- To encourage respondents to respond quickly;

- To achieve the best transition of messages, from benefits to legal aspect; and

- To be the least cluttered as possible.

The text and tone of the letters, and the way in which they address the legal requirement to complete the census in particular, was the focus of considerable attention in the discussion period following the presentations (Section 3.1.3, below).

Mathieu also noted that the national public communication program for the 2016 census was closely aligned with the wave methodology approach, reinforcing the main messages at each wave and changing them over time. Mathieu said each wave was accompanied by dominant messaging cues:

- Wave 1, the big kick-off initiated on May 2, very deliberately does not play up the mandatory nature of the census, Mathieu said (though the “Complete the census—it’s the law” appeal does still appear on the mailing exterior, as shown in Figure 3.10). Instead, the messages that are chosen to dominate are the “quick, easy, and secure” nature of census response (in a media advisory). The program of television and radio advertising in Wave 1 emphasizes the reasons why the census is important, arguing that “what’s really arriving in the mail is a chance to shape where you live,” according to Mathieu. The Wave 1 letter proposes a deadline for census response (“Please complete it by May 10”).

- Wave 2, beginning May 11, begins to play up the required-by-law nature of the census. The proposed deadline for response having now passed, Mathieu said that they did not want respondents to think that “there’s no

___________________

4 The Census Questionnaire Response referenced in the letters is an automated phone line; an option is provided for respondents to key in their ID from the form to receive a paper questionnaire.

-

point to completing the census now”—so the message stressed in media advisories for Wave 2 is “it’s not too late.” The reminder letter does not mention the previous deadline but both it and the exterior “envelope” of the mailer urge: “Complete it today.” The exterior of the mailing adds the appeal that “Delays increase census costs for every Canadian,” while the advertising program repeats the “what you’re really doing is shaping where you live” pitch.

- For Wave 3, beginning May 19, the messaging becomes blunt; Mathieu noted that the exterior of the mailing attempts a deliberate jolt to action with the prominent tag “2016 Census: Final Notice.” As became a point of discussion, the accompanying letter takes a hard line with the “required by law” message and, significantly, alludes to legal consequences of not answering. The television and radio ads in Wave 3 urge: “Please take the time to complete your 2016 Census, using the package you received in the mail.”

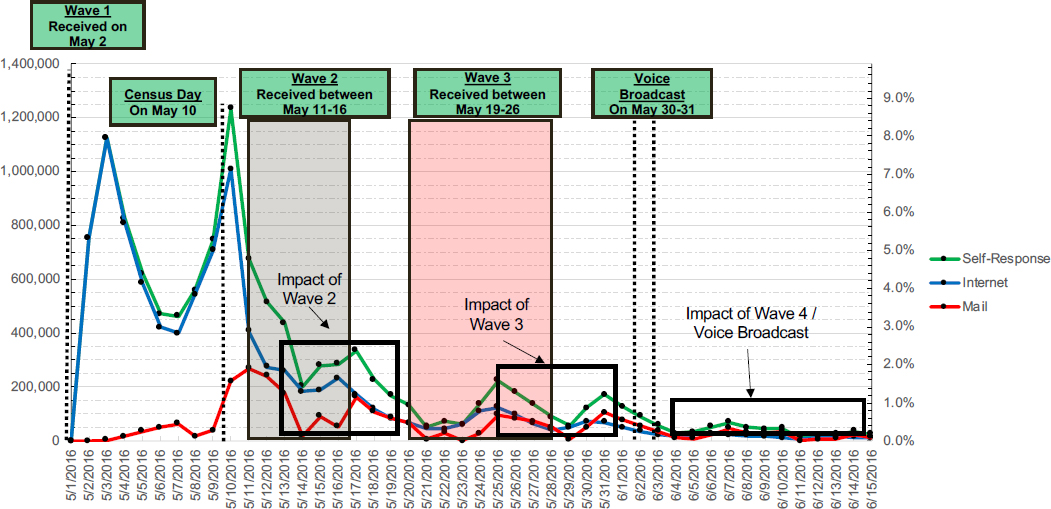

Mathieu illustrated the performance of the approach with the graph of daily response rates shown in Figure 3.11 and the table summarizing response rates shown in Table 3.3. He said that the basic features of the figure are very clear: a very sharp initial spike in interest and response when the mailers first arrive, followed by a bit of a drop-off, and then a big spike around the well-publicized Census Day itself. The boxes along the bottom of the graph in Figure 3.11 show what Mathieu described as the impact of Waves 2 and 3, some bursts of additional response amidst the strong general decreasing response levels. He noted that the self-response channels remain open through the whole nonresponse follow-up (NRFU) period, which is why there are still mild upticks visible late in the time series. He added that the “notice of visit” cards that enumerators leave at the door of NRFU households include mention that they can still self-respond/reply online. In Table 3.3, Mathieu drew particular attention to the first two numbers in the Internet response column. The List/Leave areas are primarily rural, but they still returned a higher-than-expected 23.6 percent via the Internet. Mathieu said that this success has Statistics Canada considering ways to improve on Internet take-up in 2021, perhaps by dropping a letter with Internet response options in lieu of a full questionnaire package; the challenge is doing so while still providing a mechanism for getting questionnaires to households that truly need them to participate.

Various threads of the presentation, and strengths of the Canadian approach, came together in a humorous moment in Mathieu’s presentation—when discussion of differences between Internet response in 2011 and 2016 obliged him to mention the moment when the 2016 census experienced what could have been a serious stumbling block. The 2011 census materials deliberately used slightly looser deadline text in order to diffuse the processing load of Internet

Table 3.3 Response Rates by Collection Methodologies, 2016 Census of Canada

| Method | Self-Response | Interview | Nonresponse | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHL | NRFU | Total | |||||||

| Internet | Total | Field | CSU | ||||||

| Mail-Out | 12.7 | 76.2 | 89.0 | 1.1 | 7.4 | 0.9 | 9.4 | 1.6 | 100.0 |

| List-leave | 64.1 | 23.6 | 87.7 | 0.5 | 9.3 | 1.3 | 11.1 | 1.2 | 100.0 |

| Subtotal | 20.5 | 68.3 | 88.8 | 1.0 | 7.7 | 1.0 | 9.7 | 1.5 | 100.0 |

| Canvasser | — | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 92.1 | 0.0 | 92.1 | 7.7 | 100.0 |

| Total | 20.3 | 67.6 | 87.9 | 1.0 | 8.5 | 1.0 | 10.5 | 1.6 | 100.0 |

NOTES: CHL, Census Help Line (telephone); CSU, Collection Support Units (outbound telephone call operations from census local offices); NRFU, nonresponse follow-up.

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Patrice Mathieu.

response over time, inasmuch as the 2011 census was going to be the first to take on Internet response at full scale. The materials asked households to reply “within 10 days” in 2011. Leading up to 2011, Mathieu said that “our system planners were more confident that the systems could handle the load” and manage a spike of responses on Census Day, hence the 2016 wave methodology’s emphasis of “by May 10” as a deadline. “So, of course,” Mathieu noted with a laugh—“the systems crashed on Census Day.” Indeed, the online response system had to be suspended briefly during peak demand. Statistics Canada publicly responded, quickly, with good humor—gently encouraging “Canadians being too responsive” to take a short break—while also reassuring that their data were secure and nothing had been lost. In this way, Statistics Canada was able to parlay a brief, major stumble into very positive messaging—and “that really helped us” get the higher self-response rates.

Mathieu attributed the increase in self-response in 2016, relative to the 2011 Census, to a variety of factors. Active support and promotion of online response (and electronic services, generally) following the Canadian federal election in 2015 undeniably created “favorable conditions” for census self-response, Mathieu said. Another success factor was applying the same treatment and sequence of mailings to Mailout areas. In 2011, roughly one-quarter of Mailout dwellings had received a paper questionnaire package at Wave 1, and—consistent with the Census Bureau’s experience in testing “Internet Push” versus “Internet Choice” methods—some respondents who might otherwise respond electronically will use paper if the paper questionnaire is in hand. Mathieu said that Statistics Canada’s research estimated that 25 percent of the improvement in self-response from 2011 to 2016 could be attributed to the simple change to Internet-only at Wave 1. Other success factors mentioned by Mathieu included the expansion of the Mailout group to include a bigger share of the population, the unified messaging of the census communication strategy, and the revised content of the data collection materials (including the Wave 1 letter).

Mathieu also briefly summarized two related lines of response-mode testing that Statistics Canada had engaged in prior to the 2016 census.

- Table 3.4 illustrates the basic results of a “live test” conducted as an experiment in line with the 2011 census. As mentioned earlier as a success factor in 2016, the 2011 Canadian census still sent a full paper questionnaire to a segment of the Mailout population rather than just a letter—these “Group 2” (G2) dwellings being thought to be of lower connectivity and hence lower propensity to respond by Internet. The 2011 census “live test” was a panel of addresses for which the letter and questionnaire treatments were administered against type to some households: A subsample of G2 respondents received the letter/Internet instructions only while a subsample of “Group 1” (G1) respondents (who would otherwise get the Internet instructions only) were mailed the paper

Table 3.4 Impact of Wave 1 Letter/Response Option Choice, Live Test in 2011 Census of Canada

| Method | Response Mode | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet | CHL | NRFU | Nonresponse | Total | ||

| General | ||||||

| G1—Letter at W1 | 16.3 | 71.6 | 0.7 | 9.1 | 2.3 | 100.0 |

| G2—Questionnaire at W1 | 50.1 | 25.8 | 0.8 | 20.0 | 3.4 | 100.0 |

| Live Test—Switch Methodology | ||||||

| G1—Letter at W1 | 16.3 | 71.6 | 0.7 | 9.1 | 2.3 | 100.0 |

| G1—Questionnaire at W1 | 53.3 | 32.3 | 0.5 | 11.6 | 2.4 | 100.0 |

| G2—Letter at W1 | 23.4 | 57.3 | 1.1 | 15.3 | 3.0 | 100.0 |

| G2—Questionnaire at W1 | 50.0 | 25.5 | 0.8 | 20.3 | 3.4 | 100.0 |

NOTES: CHL, Census Help Line (telephone); NRFU, nonresponse follow-up.

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Patrice Mathieu, reformatted to single table.

-

questionnaire. In the experimental G1 group that got the questionnaire, receiving the paper form was apparently a strong impetus for returning the paper questionnaire rather than completing the questionnaire online. The results for the G2 experimental group that received the letter at Wave 1 were important to the shape of the 2016 wave methodology—achieving a close-to-60 percent Internet group amongst a segment that had been deemed to be unlikely to respond by Internet.

- Statistics Canada ran a study on preferred mode of response in its 2014 census test. Mathieu summarized that test by briefly recounting some of the observations Statistics Canada had drawn from it: that contact mode is a key factor in the choice of a response mode used by a household and that contact mode choices affect households with weaker preferences more than those with stronger preferences. They found that preferences for Internet response tend to be more fluid than for paper—and that strong preferences for paper questionnaires by some respondents are “really sticky” and hard to overcome. He said that in the context of a multimode collection strategy, the method of initial contact does not seem to reduce self-response in general, as long as the respondent’s preferred mode is offered. From this work, he said, Statistics Canada concluded support for a multimode collection strongly directing respondents to use online response, while still offering a paper alternative.

Heading towards the 2021 census, Mathieu commented that Statistics Canada is aiming to reduce the amount of paper that it uses even more—-

studying, in particular, the previously mentioned use of an invitation letter (in lieu of a paper questionnaire package) for some List/Leave areas and the utility of including a paper questionnaire by default in the Wave 3 mailing. The wording of the Wave 1 and Wave 2 letters is being revised to encourage a try at online response before requesting a paper questionnaire. And, building off of 2016 successes, Statistics Canada is seeking ways to make its communication and media strategy for the 2021 census “more targeted” in nature.

3.1.3 Discussion

Darby Steiger (Westat) asked what either the Census Bureau or Statistics Canada knows about how Internet response varies by platform (phone, tablet, computer). Debbie DiLeo (Census Bureau) responded, based on research she has been doing on the topic using January 2018 ACS data. In that month, 50 percent of returns were obtained by Internet and 25 percent each by mail and CAPI/field interview. Of the Internet responses, in unweighted data, 75 percent were computer, 10 percent tablet, and 15 percent phone. Mathieu recalled that Internet response in 2016 was about 80 percent computer, 14 percent tablet, and 6 percent phone. He added that, when respondents break off entry in electronic mode and resume later, it is usually to go with a “larger” format—from phone to tablet or from tablet to computer—and not the opposite. This leads them to surmise that the census form might still be too unwieldy for some users to handle by cellphone. Statistics Canada has also found that completion times for questionnaire tend to be shorter on mobile devices, an effect that they are still working to explain.

Don Dillman (Washington State University) asked whether either party knows much about the demographics of respondents who continue to choose paper versus those who respond online—and whether any sign that the major demographic gaps circa 2007–2008, when the big push to Web-based interviewing began, have closed. Mathieu replied that the gap has not closed in Canada: households that actively seek out the paper questionnaire tend to be older and larger. His organization’s sense is that making the paper option more scarce (requiring effort to obtain) will probably only serve to reinforce those differences.

Tack Richardson (MITRE Corporation) asked Mathieu whether Canada has studied the effects of its media/communication campaigns concerning the census. Mathieu indicated that they had but that media effects are always difficult to sort out with confidence; it is difficult to know what part of increased response would only have come about through communication messages, independent of the wave methodology and other improvements. Statistics Canada has tried to have a stronger social media presence and target key population groups with its media messages, generating interest in the census.

Brian Harris-Kojetin (Committee on National Statistics) asked Mathieu about continuum of wording across the three letters shown in Box 3.1. Knowing that the ACS Office has been doing work on softening the language about mandatory response or possible penalties (as discussed later in Section 3.2.1), he was interested in Canadian experience with piloting and testing (qualitatively or quantitatively) the apparent escalation of rhetoric in their letters—to the point that the Wave 3 letter comes close to threatening referral for prosecution. Mathieu answered that they had done extensive qualitative testing “before, during, and after” both the 2006 and 2011 censuses on those legal cues. Qualitative, focus-group-type work with late-responding census households found them to be more understanding of the Wave 3 letter language than threatened by it; they generally concede that they knew that response was required, and they understand why that language is there, so they do not find it rude or off-putting (even though little more than 2 weeks would have passed since Census Day, when they see that language). Mathieu said that they find that very few nonrespondents are acting out of animus toward the government or hostility to the census effort, but fail to respond for more innocuous reasons such as having busy schedules. Harris-Kojetin asked whether Canada has experienced anything like the ACS has in terms of complaints—letters to government ministers or members of Parliament. Mathieu noted that every Canadian census is accompanied by complaints from some members of Parliament that Statistics Canada has to work through. Later, Dave Waddington (Census Bureau) asked whether Canada has actually followed through on prosecution for census nonresponse. Mathieu said there have been hundreds of cases (though almost certainly less than 1,000)—but the process is slightly complicated by the inability to prosecute an address, but rather having to prosecute someone. Getting to that next step requires demonstration that Statistics Canada has made multiple contacts with a specific person, has explained the consequences for nonresponse, that the specific person is aware of those consequences, and that he or she still declined to respond. Past Canadian census law made it possible for persons to be jailed for nonresponse to the census, but that has since been removed, and Mathieu said that action never resulted in incarceration.

In later discussion, Barth returned to the side-by-side presentation of letter text (Box 3.1), commenting to Mathieu that the letters struck her as text-dense, with the eye tending to follow the clauses in boldface type. Contrasting with the ACS experience where just putting “your response is required by law” in bold type could increase response rates by 3–4 percentage points, she observed that the Canadian census letters never call out the mandatory-response language in bold type and asked if Statistics Canada had tested that variant?. Mathieu could not recall whether that specific variation was tested. He also noted that the side-by-side rendering of the text is not exactly how they appear in the printed product, and the different typestyle and arrangement on the final

letters could have an effect. Dillman added that a lot of testing surrounded the development of the U.S. census mailing package language of “your response is required by law” in the 1990s; it gave a bigger increment of response than any of the other design changes being considered. Itwas a two-pronged main message: the envelope conveyed the requirement, but the letter attempted some explanation of why response is required by law. Observing that such an explanation seems to be missing in both the ACS and the Canadian census materials, he asked why that is the case. Barth said that part of the new approach (discussed later in the workshop) on softening the mandatory-response language is intended to play up the “why,” which is the importance to the community. She said that it has always struck the ACS designers as difficult and “wordy” to attempt the explanation that “this used to be the long form,” and that they do not know whether the respondent would be attuned to or interested in that reasoning. The Bureau is considering the language for the FAQ brochure or back-of-the-letter parts of the ACS mailings. Mathieu noted that the broader communications strategy around the Canadian census has played up the benefits and the importance to the community. He is interested in testing that kind of message in the letters.

Jonathan Schreiner (Census Bureau) commented that he is usually a proponent of having one or more big differences in the various mailings a respondent sees—mainly common features in order to provide a unified appearance, to be sure, but some visual or wording differences to make each piece seem important as a new communication. He said he was struck that Canada seemed to use the same external appearance on the mailings in Wave 1 and Wave 2—and had success with it—and so asked about the testing that led to the decision to keep so much the same. Mathieu answered that part of it is operational—the same printer handles the Wave 1 and Wave 2 letters, so it is easiest on that score to keep the physical appearance consistent. He agreed that visual differences can stimulate interest, but that the opposite effect could also be argued as being strong—similarity in presentation and method can stir remembrance of something that had just slipped the mind on the first approach. Similar to the point he made in addressing Harris-Kojetin’s question, Mathieu suggested that Wave 2 nonrespondents were often “easy” cases to handle in that they tended to be people who forgot or did not have time to complete the questionnaire, and that they were not withholding response due to some hard-set concern. Mathieu also noted subtle differences in the exterior of the mailing packages, across the waves in the 2016 census and certainly between the 2011 and 2016 censuses. For instance, one of the later mailings in 2010 explicitly printed “Reminder” on the exterior, while 2016 changed the language on the exterior of the final mailing to read “Final Notice” in a way that had not been done in 2011.

Cynthia Clark (formerly, U.S. Census Bureau) asked both speakers about testing that led to the compact schedule/quick-burst mailing in the Canadian

approach and the comparatively more spread-out sequence of contacts in the ACS. Barth replied, on the ACS side, that the major difference is that the Canadian wave methodology is primarily focused on a one-shot census effort, while the ACS tries to spread effort out as a continuous measurement exercise. Mathieu agreed, adding that the Canadian census is very locked into a tight schedule—Census Day has to be in May for a number of reasons (weather, and accessibility earlier in the year, among them), but data collection has to be quick lest it conflict with summer vacations and travel. Clark followed up by asking to contrast the seeming escalation/building of messages across contacts in the Canadian approach, while the ACS approach seemed to be striking the same message themes in each of the contacts. On the ACS side, Barth noted that this would be a major focus of the afternoon’s presentations later in the workshop.

Jenny Genser (Food and Nutrition Service) commented that one reason for the high response rates in the Canadian census is that it was a census, making use of the increased publicity and awareness surrounding such a nationwide effort, while fewer people are aware of an ongoing survey like the ACS. Mathieu said that, even on the quinquennial cycle, not everyone is as aware of the census in Canada as one might expect. Statistics Canada has a good reputation, as a centralized agency for all the nation’s business, health, and population statistics, which helps; the communication strategy around the census certainly helps as well. But he said that Statistics Canada had managed to achieve response rates of 80 percent or higher even in testing in 2014, which argues for the methodology having a major effect.

Michael Schober (New School for Social Research) asked whether the Census Bureau or Statistics Canada has researched, whether in the field or “in the lab” in cognitive testing environments, what people actually read and remember in census and survey mailings. Barth said that she has conjectures but not evidence; the ACS materials are text-dense, and that kind of insight is front-and-center to her as the ACS works to redesign its messages. Mathieu said Statistics Canada does qualitative testing before, during, and after the censuses, trying to walk through the whole census process—akin to “pretend it’s May 2 and you receive this in your mailbox, what do you do?”—and talk through their thoughts in reviewing the mailing contents. The work runs the gamut of possible reactions, from people intently reading every word to people ignoring all instructions, to people responding to any direct call-to-action as a demand (if a phone number is given, they will try to call the number). But his sense is that most respondents are looking for instruction/direction or requirements (e.g., deadlines) rather than weighing the strength of any particular arguments or appeals. This point about collecting feedback about what respondents actually process in mailed messages would recur, in some detail, later in the workshop; see Section 3.4.5.

3.2 ACS TESTING ON RESPONDENT CONTACT STRATEGIES

3.2.1 Overview of ACS Tests to Boost Participation Through Improved Communication

Elizabeth Poehler (U.S. Census Bureau) summarized five major tests conducted on the ACS mailing materials since the 2016 workshop, noting the tests shared two overarching objectives: to improve self-response rates as much as possible by streamlining the materials where appropriate and to be responsive to both respondent and stakeholder concerns about the nature and tone of the mandatory-response language in the materials.

Of the Pressure Seal Mailer Test, Poehler would note that “you’ve already seen where we came down on that.”5 To explain how and why the format of two of the ACS mailings changed in late 2018, Poehler noted that the ACS has tested pressure seal mailings because they are less expensive to assemble than stuffing traditional letters into envelopes. But they were more drawn to the format because it has become recognized in the general public as an “official mailer” and one used for confidential material: the perforated, tear-off-strip format used for mailing personal identification or PIN numbers, confidential results, report cards, and other sensitive information. An added benefit of the pressure seal mailer format is that it is enclosed, making it viable to transmit Internet questionnaire access ID (considered personal information, as unique to the household) in a way that a simple postcard cannot.

Poehler summarized the experimental design and basic results of the Pressure Seal Mailer Test in three tables, shown as three panes in Table 3.5. All addresses in the test were sent the usual Mailing 1 and 3 materials as appropriate, with the variation being whether Mailings 2, 4, or 5 were sent in the then-standard letter or postcard format or whether they were sent in the new pressure seal mailer format. (A subtle but important point in the first pane of the table, given the later adoption of the format—most of the experimental materials in 2017 utilized a trifold pressure sealer mailer, while the Census Bureau ultimately decided to use the less-tested-in-2017 bifold format.) Turning to pane (b) of the table, Poehler noted that the pressure seal mailers did not have any impact on self-response overall before CAPI. However, restricting attention to self-response rates among those continuing nonresponse households who received Mailing 5, the pressure seal mailer format in Mailing 5 had a significantly higher response rate than the postcard format, with most of that coming through Internet response. Admittedly, Poehler said, the size of that subset was sufficiently small that the mailer format did not have a sizable effect overall, but the test offered hope that an added official-looking boost at the very end might still help.

___________________

5 For additional detail on the test and the detailed results, Poehler directed participants to https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2018/acs/2018_Risley_01.html.

Table 3.5 Experimental Design and Results, 2017 American Community Survey Pressure Seal Test

| (a) Experimental Design | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mailing 2 | Mailing 4 | Mailing 5 | |

| Production | Reminder Letter | Reminder Postcard | Additional Reminder Postcard |

| Treatment 1 (Control) (≈24,000 addresses) | No change | No change | No change |

| Treatment 2 (≈48,000 addresses) | Pressure seal (trifold) | No change | No change |

| Treatment 3 (≈48,000 addresses) | Pressure seal (trifold) | No change | Pressure seal (trifold) |

| Treatment 4 (≈24,000 addresses) | Pressure seal (trifold) | Pressure seal (bifold) | Pressure seal (trifold) |

| (b) Self-Response Return Rates (Before CAPI/Field Follow-up) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 1 (Control) | T2 | T1 vs. T2 P-value | T3 | T1 vs. T3 P-value | T4 | T1 vs. T4 P-Value |

| 53.0 (0.4) | 52.7 (0.3) | 0.57 | 53.4 (0.3) | 0.45 | 52.6 (0.4) | 0.46 |

| (c) Self-Response Return Rates (Before CAPI/Field Follow-up) for Those Mailed Mailing 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response Mode | Pressure Seal (T3) | Postcard (T2) | Difference | P-Value |

| Total Self-Response | 19.3 (0.4) | 17.9 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.6) | 0.02∗ |

| Internet | 11.2 (0.3) | 9.6 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.5) | < 0.01∗ |

| 8.0 (0.3) | 8.3 (0.3) | −0.3 (0.4) | 0.45 | |

NOTES: T1, Treatment 1 (and so forth). Standard errors are in parentheses. Significance tested based on two-tailed t-test at α = 0.1. In the test, Mailing 1 was the usual (production) initial mailing package and Mailing 3 the usual questionnaire package, as described in Section 3.1.1.

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Elizabeth Poehler.

Accordingly, Poehler said, the Pressure Seal Mailer Test showed no impact on self-response of using the new format, overall. Cost analysis suggested that implementing the pressure seal mailer format in Mailing 2 would be cheaper than continuing to use traditional letters/envelopes, and that replacing the postcard in Mailing 5 would be “close to cost neutral.” Accordingly, she said, the Census Bureau opted to take the cost benefits without impeding response, implementing pressure seal mailers for Mailings 2 and 5 starting with the September 2018 sample panel.

The Mail Design Test field-tested three bundles of revisions to the ACS mailing materials, that had been developed and refined since preliminary versions were tested in 2015. The new treatments were meant to use a friendlier and more conversational tone in the ACS mailings, staying positive by emphasizing the benefits of participating in the survey, and reducing burden through the removal or combination of materials in the mailings.6 Specifically, the Mail Design Test focused on three experimental treatments:

- The Softened Revised Design used deliberately softer language: “Your Response is Important to Your Community” rather than “Your Response is Required by Law.” It also included some modification to envelope, letters, and postcards.

- The Partial Redesign implemented the same softening of the mandatory-response language, and it used a letter for Mailing 5 rather than a postcard. Importantly, it emphasized the benefits of ACS response through inclusion of a glossy, brightly colored, one-sheet brochure titled “How Your Responses Help America”—conveying a great deal of “Why We Ask” information in accessible format. It also removed and combined some materials, notably removing the FAQ brochure (but incorporating some of its content on the back of the letter). Finally, it used a modified front page on the ACS questionnaire itself, under the theory that the questionnaire might be the main thing or even the only thing that a respondent might pull from the envelope; the new front cover placed more information about the ACS on that front sheet.

- The Full Redesign did all the same things as the Partial Redesign, but also made changes to the envelopes, letters, and postcard.

The results of the Mail Design Test are shown in four panes in Table 3.6. From pane (a), Poehler observed that all three experimental treatments had significantly lower response rates than the control group, reinforcing the message that “softening the mandatory response language doesn’t do us any favors” in terms of response rates. This shifted the study’s main interest towards comparing the three new treatments against each other. Pane (b) of the table

___________________

6 Poehler noted that the results of the Mail Design Tests, and the Adaptive Strategy test described next, were to be made available shortly at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/library/publications-and-working-papers.html.

Table 3.6 Results, American Community Survey Mail Design Test

| (a) Final Response Rates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Rate (SE) | Experimental − Production | P-Value |

| Production (Control) | 94.3 (0.3) | — | — |

| Softened Revised Design | 93.3 (0.3) | −1.0 (0.4) | 0.02∗ |

| Partial Redesign | 93.0 (0.3) | −1.3 (0.4) | < 0.01∗ |

| Full Redesign | 92.6 (0.4) | −1.7 (0.5) | < 0.01∗ |

| (b) Partial Redesign vs Softened Revised Design | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point in Data Collection Cycle | Partial Redesign | Softened Revised Design | Difference | P-Value |

| After the first two mailings | 19.0 (0.3) | 20.3 (0.3) | −1.3 (0.5) | 0.01∗ |

| After the third and fourth mailings | 39.2 (0.5) | 39.4 (0.4) | −0.1 (0.7) | 0.83 |

| After the fifth mailing | 52.9 (0.4) | 51.5 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.7) | 0.05∗ |

| (c) Full Redesign vs Softened Revised Design | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point in Data Collection Cycle | Full Redesign | Softened Revised Design | Difference | P-Value |

| After the first two mailings | 16.5 (0.2) | 20.3 (0.3) | −3.9 (0.4) | < 0.01∗ |

| After the third and fourth mailings | 34.2 (0.3) | 39.4 (0.4) | −5.2 (0.5) | < 0.01∗ |

| After the fifth mailing | 48.3 (0.4) | 51.5 (0.5) | −3.1 (0.6) | < 0.01∗ |

| (d) Full Redesign vs Partial Redesign | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point in Data Collection Cycle | Full Redesign | Partial Redesign | Difference | P-Value |

| After the first two mailings | 16.5 (0.2) | 19.0 (0.3) | −2.6 (0.4) | < 0.01∗ |

| After the third and fourth mailings | 34.2 (0.3) | 39.2 (0.5) | −5.1 (0.5) | < 0.01∗ |

| After the fifth mailing | 48.3 (0.4) | 52.9 (0.4) | −4.6 (0.6) | < 0.01∗ |

NOTES: Standard errors are in parentheses. Significance tested based on two-tailed t-test at α = 0.1.

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Elizabeth Poehler.

suggests that the Softened Revised Design had significantly higher response than the Partial Redesign treatment in the beginning (after first two mailings). There was no significant difference between the two treatments after the fourth mailing (Mailings 3 and 4). But, by the end of CATI interviewing (which was still used), self-response for the Partial Redesign surpassed that of the Softened Revised Design (by 1.4 percentage points). “There was something in those sequences of contacts that was working and not working,” Poehler said, leading to conjectures but no solid conclusions. Turning to panes (c) and (d), the Softened Revised Design had significantly higher self-response than the Full Redesign at all three points in data collection, and the Full Redesign was also bested by the Partial Redesign throughout the production process. So, Poehler noted, “something in the Full Redesign clearly did not work as hoped.” From the test overall, Poehler said that the Census Bureau had concluded that all three experimental treatments had lower overall response—and higher costs—than the control group. She said that the inclusion of the “Why We Ask” brochure in Mailing 1 was singled out as a particular misstep and that it “should not be incorporated.”

The Adaptive Strategy Test further explored the somewhat paradoxical result experienced in 2013 when Internet response was first introduced in the ACS. At that time, the Census Bureau found that the “Internet Push” strategy generally increased the take-up rate but dampened response rates in some geographic areas. So, the notion of the test was to identify areas where sending a paper questionnaire in the first mailing might result in higher self-response rates. The test was premised upon a classification of all census tracts into one of three categories—Mail Preference, Mixed Preference, or Internet Preference—based on analysis of a set of variables and indicators:

- Ratio of mail to Internet returns;

- Self-response rates;

- Prevalence of high speed Internet connections;

- Percent of population aged 65 and older; and

- Areas that showed the aforementioned dampening in self-response after Internet implementation.

Poehler noted that the same set of variables and indicators is being analyzed in support of planning purposes in the 2020 census. With this partition of geographic areas in place, the Adaptive Strategy test randomly assigned Internet Push (control) or Internet Choice treatments to housing units in Mail Preference or Mixed Preference tracts, as shown in pane (a) of Table 3.7. The basic results are summarized in pane (b) of that table: Poehler commented that the Choice method produced lower self-response rates while increasing cost (through the larger number of paper questionnaire returns). Hence, she said, the Census Bureau decided not to move forward with the Choice method.

Table 3.7 Experimental Design and Results, 2017 American Community Survey Adaptive Strategy Test

| (a) Experimental Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date Mailed | Control (Internet Push) | Experiment (Choice) |

| 9/21/2017 | Initial Mailing Package—Internet Push | Pre-Notice Letter |

| 9/25/2017 | — | Initial Mailing Package—Web and Paper Option |

| 9/28/2017 | Reminder Letter | Reminder Postcard |

| 10/13/2017 | Paper Questionnaire Package | — |

| 10/17/2017 | Reminder Postcard | — |

| 10/19/2017 | Replacement Questionnaire Package | |

| 11/2/2017 | Final Reminder Postcard | Final Reminder Postcard |

| (b) Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet Push (Control) | Choice (Experiment) | Difference | P-Value | |

| Mail Preference | 39.1 | 37.3 | 1.7 (0.6) | < 0.01∗ |

| Mixed Preference | 48.4 | 45.7 | 2.8 (0.6) | < 0.01∗ |

NOTES: T1, Treatment 1 (and so forth). Standard errors are in parentheses. Significance tested based on two-tailed t-test at α = 0.1. In the test, Mailing 1 was the usual (production) initial mailing package and Mailing 3 the usual questionnaire package, as described in Section 3.1.1.

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Elizabeth Poehler.

Poehler said that the Data Slide Test sought to make the ACS more “real” to potential respondents, and allay respondents’ concerns about the privacy of their data and the legitimacy of the ACS in general, by including a simple, accessible data tool in the ACS mailing. In 2017, the ACS developed a popular “data wheel” as an outreach item—cardboard wheels held together by a grommet that show key ACS information about different states through a window when the wheels are turned. The idea is convey that kind of “interactive infographic” tool directly in the mailings, but use of the existing data wheel is problematic on two fronts. It just barely fits in the current ACS mailing envelopes and the metal grommet holding the wheel together can cause problems with mail processing machines. Hence, the “data wheel” was redesigned into a rectangular, slide-rule format—the Data Slide—that easily fits the mailer. Hence, the experimental design of the Data Slide test was very simple: a control group went through the usual ACS sequence, a Treatment 1 group received the Data Slide in Mailing

1 (with everything else kept the same), and a Treatment 2 group received the Data Slide in Mailing 3 (keeping all else the same).

Poehler gave some very preliminary results of the Data Slide Test—preliminary, because it had only been fielded in May 2018. Poehler said that Treatment 1 (Data Slide in Mailing 1) had higher Internet returns and lower mail returns than the control group, though overall self-response was not significantly different. Treatment 2 (Data Slide in Mailing 3, which also contains the paper questionnaire) also registered insignificant change in that overall self-response was not different. But she said that analysts are still working to understand why Treatment 2 seemed to work particularly well (higher self-response, higher Internet returns, no difference in mail returns) for a subset of those who were mailed the paper questionnaire.

Poehler could only speak to the design, and not the results, of the Mail Materials Test because it was being fielded at the time of the workshop. The goal of the test is to field test the performance of five experimental treatments:

- Modified Control, which removes the FAQ brochure from Mailings 1 and 3 (shifting some “necessary” content to the back of the letter and removing the instruction card from Mailing 3);

- Emphasized Mandatory with Revised Questionnaire, which includes stronger mandatory-response messaging (through boldface type and altered placement), updated design of letters and questionnaire (the questionnaire redesign consisting of improvements to the “cover page” to emphasize the Census Bureau brand, among other things);

- De-emphasized Mandatory with Revised Questionnaire, which maintains the mandatory-response cue on the envelope (to try to get it opened) but softens the language in the mailing-package letters (Poehler conceded that there is some internal debate at the Census Bureau as to whether the “softer” language is really softer than the current language, but she said “it is definitely softer” than the Emphasized Mandatory treatment language), while using the updated design of the letters and questionnaire;

- De-emphasized Mandatory with Current Questionnaire, which is the same as the previous treatment except that it uses the current ACS questionnaire; and

- Softer/Eliminated Mandatory, which softens the mandatory-response language in the letters and removes it entirely in some cases, while using the updated design of the letters and questionnaire.

In closing, Poehler noted that future tests being considered for 2019 include variations on the use of due dates/deadlines in ACS mailings and the testing of a modified mailing schedule.

3.2.2 A View From the Private Sector

Asked to discuss the range of ACS testing described by Poehler from the perspective of a private-sector survey organization, Douglas Williams (Westat) began by commending its quality as well as the way in which the current ACS approach is based on previous research, although there might be disappointment in the test results because improvements in self-response tended to be both few and small. But Williams phrased it as a positive, that the research and testing “validates the current ACS design”—though he hastened to add “(?)” to that statement. He said that he phrased it that way, with the question mark, because the testing has not yielded that “next big thing” what will really move the needle in terms of boosting survey response. The small effects, and the failure (yet) to find a factor of major influence highlights the challenges facing the ACS and the general survey environment today.

Williams said that the testing had generated some useful knowledge about changes to the survey stimulus—the format of the mailings. In particular, he pointed out Treatment 3 of the Pressure Seal Mailer Test and the improvements achieved in Mailing 5 of the Mail Design Test.

Williams commented that the current ACS materials are, successfully, recognized as official and functional, but that the null gains in response evidenced by the Pressure Seal Mailer Test raised some questions. It remains unusual that the pressure seal mailer format—which came of interest expressly because of its official feel and its trusted nature—did not yield gains in response (though it still had compelling enough advantages in cost and production that the decision was still made to adopt the format). It is particularly unusual that the pressure seal mailer did not outperform the postcard in terms of response; the perceived difference in confidentiality or official-feel between a pressure seal mailer and a sealed envelope (letter) is arguable, but the pressure seal mailer should surely appear better on both fronts than a simple postcard. Williams noted it could be argued that Treatment 4 in the Pressure Seal Mailer Test might overuse the new concept—the last group of nonrespondents received the same stimulus, in the new format, three times. That similarity in feel and approach seems to have been very effective in the Canadian census context, but showed no apparent effect in the United States.

Turning to the Mail Design Test and the issue of mandatory-response wording in general, Williams said that the test was intended to show the “softer, gentler side of ACS” and that it produced lower response (but not much lower). The test results suggest that the mandatory-response language remains among the ACS’s most effective levers, he observed, but the question is why that language is so powerful. He suggested that people do not like being told what to do, but that casting things as consequences can be particularly compelling and may be better at motivating action than verbal appeals. The current ACS mailing materials do suggest some consequences—for instance, saying that a

questionnaire will be mailed if there is no response to an initial mailing or that an interviewer may make a personal visit—but that is a hook that could be investigated further.

In terms of informational content, Williams said that it is important to bear in mind that the decision to participate (or not) in a survey is not the long, careful, deliberative process that survey designers would like. Instead, he argued, the decision “seems largely based on heuristics, and it is a decision made quickly”—however disappointing it may be to the survey designer, respondents are exceedingly unlikely to read everything put in front of them. In that spirit, Williams cautioned to the Census Bureau not to be too hasty in abandoning the “Why We Ask” brochure; he characterized it as “right idea, too much content” and feeling a little bit like homework to read. The problem with the “Why We Ask” brochure and the Data Slide is that it is not necessarily the detail that respondents want, and that it is not readily clear to respondents why those inserts address any of their reasons for being unwilling to paticipate. Williams also suggested that the tests might have presented the innovative materials too early (in Mailing 1, which contains a lot of other information, which already could be argued to crowd out the initial request for action) or at the wrong contact (e.g., at Mailing 3, which is dominated by the paper questionnaire).

Williams suggested that, in terms of mail/paper preference, both sides of a major proposition seem to remain in play. The continued results of Internet Choice treatments, where sending the paper questionnaire along in the mailing tends to increase paper response but not Internet take-up, still seem to be performing suboptimally—as he noted was consistent with the Medway and Fulton (2012) meta-analysis—but the result was not terribly far off. If that’s true, and there does remain a segment for whom the paper questionnaire will remain the very “sticky” preference, then would a mail/paper-only treatment group work better? But, on the other hand, it could be legitimately asked: have we reached a point where a true mail/paper preference group no longer exists, with technology increasingly becoming a necessity. Williams argued that the Census Bureau is perhaps better positioned than anyone to do the analysis of web paradata, timing of responses within electronic questionnaires, the distribution of device types used to complete the survey, and so forth to inform effective prediction of response mode propensity.

On the topics suggested by the recent ACS testing, Williams recommended testing of a unique-format stimulus at the fifth and final mailing only. At the time of the Pressure Seal Mailer Test, reserving the “feels official” pressure seal mailer to the final meeting was not a good option because a third contact method (telephone interviewing) was still being used in the ACS. Williams said that the effectiveness of a unique, attention-grabbing format was supported by the Mail Design Test findings, and so it is worth considering whether leveraging the power of unique format and message in the final appeal would be helpful. Williams also urged the ACS Office not to give up—“yet”—on the

informational brochures (including the “Why We Ask” brochure used in the tests). There is good material in those documents, and trying to find some way to include informational or motivational messages at reminder contacts might serve to boost Internet returns. The challenge is to provide the information in the way that people consume it, “in small doses;” Williams further suggested providing concrete, less abstract examples of how ACS data have been used. Regarding the pending test of mandatory response language, Williams suggested a gradation in the sharpness of the language—akin to the Canadian model, using soft language at the early contacts and stepping up the urgency and necessity in later contacts. Finally, Williams urged the ACS researchers to consider “consequential wording,” citing work by Tourangeau and Ye (2009) based on prospect theory. The essential idea is that human nature seems to be to fear losses more than to anticipate gains; in the ACS context, appeals and arguments keyed to the notion of states or localities losing funding might be more effective than more abstract notions of services that could be gained.

As major directions for the next phase of ACS research and testing on messaging, Williams offered four suggestions:

- Having concluded “Internet push” methods to be most effective, Williams suggested finding ways to push to Internet response more aggressively. The roughly two-thirds self-response by the Internet in some of the experiments is very good, but something like pushing out the mailing of the paper questionnaire even further would be useful to test.

- Foreshadowing a theme discussed in the next session of the workshop, Williams suggested experimenting with “push to device” reminder contacts. He noted the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ experience with trying to improve data collection in the Consumer Expenditure Survey, promoting data entry and collection via mobile device—the vision being that respondents would enter their spending information while sitting at a restaurant or while checking out at stores. He said that respondents still resisted in-the-moment data collection on that particular survey instrument on their phones and mobile devices, but they very much liked reminders and prompts via mobile device.

- Williams urged the ACS researchers to “reconsider or reinvent” the notion of survey prenotification. Rather than just advise respondents that something will be coming, he suggested that the initial contacts could be reframed to familiarize those respondents with the ACS—in small doses of information, and perhaps using “did you know?” types of factoids to introduce the range of questions in the ACS. One possibility might be to directly but conversationally address concerns about ACS response being required by law, clarifying that this helps maintain high levels of data quality.

- Finally, Williams urged attention to thinking about communication and messaging beyond or after the mail sequence. Some nonresponse, and the resulting field interviewing in nonresponse follow-up, is inevitable. The most productive message of the fifth/final mail contact could be to notify people of the personal visit and to prepare them for it (rather than just warning them of the possibility), while still “giving them the out” of forestalling the visit by responding online.

3.2.3 A View From Academia

Asked to comment on the suite of ACS testing from an academic perspective, James Wagner (Survey Research Center, University of Michigan) began by noting that the ACS “is a standard against which we measure other surveys,” in both is size and methodology. The sample sizes available for experimentation in single ACS methods panels (subsets of the whole ACS annual sample) are “astounding” relative to the sample sizes of other entire surveys. He said that survey research generally faces a “crisis of reproducibility,” the results of many small experiments being run with a lack of statistical power and generating a lot of false positives.

Against that backdrop, he said the large ACS tests provide a solid foundation but also raise fundamental questions. Response rates to the ACS have been very high and remain so, which makes them even more difficult to “improve” upon; Wagner argued that W. Edwards Deming’s notion that a class of people will never respond to any survey question remains a valid concern, and the ACS may be approaching a ceiling beyond which no improvement may be made. But, more fundamentally, Wagner asked: What does “improving” mean in the ACS context, and is “improving response rates” really the relevant metric? Wagner suggested that one way to think about “improvement” is to reduce measurement error; in that case, the first day of the workshop and its discussion of survey data compared with administrative and third-party data suggests a very different set of metrics. Alternately, “improvement” could be conflated with reducing costs; some ACS tests seems to have been expressly designed as cost-saving, he said—noting that this is definitely an important consideration. Finally, “improvement” could mean the elusive concept of reducing burden: “burden” in a broad sense, not just time spent completing the survey. Wagner said that this seems to be part of the motive for softening the mandatory-response language, precisely because that language does create another kind of stress/burden that might be necessary to connect with some possible ACS respondents, but surely not all. Whichever definition or combination of definitions prevails, Wagner urged careful consideration of the full set of features that can be manipulated and how those features are likely to impact metrics of quality, metrics that must be chosen carefully.

Wagner outlined an idealized process for testing, starting from an assumption of population heterogeneity. The premise is to identify the relevant subgroups in the population—people who need paper questionnaires in order to respond at all, people who need a strongly worded mandatory-response message to be motivated, or the like. These subgroups should be identified in conjunction with choosing the quality metrics, and vice versa; experimental strategies should be assigned in a way that optimizes cost and works best with the chosen quality metrics. Wagner noted Mathieu’s comments from earlier in the day at the workshop about the difficulty of truly “adapting” protocols and customizing them to various population subgroups, in a big production process like a census or the ACS. It is not easy, and “that’s a problem I’ve wrangled with for the last 10 years” as technical systems have for surveys. He added that the conduct of multi-arm experiments, and assigning treatments purposively rather than purely randomly, could help in testing.

Of the Pressure Seal Mailer test, Wagner noted that the total response rates were not that different; the test was able to detect higher response rates for Treatment 3 (pressure seal mailer at both Mailing 2 and 5) relative to Treatment 2 (pressure seal mailer only at Mailing 2). But the “improve response rates” metric proved relatively uncompelling, Wagner suggested, and the improvement-as-cost-reduction instinct prevailed, the pressure seal mailer format being less expensive than the traditional letter-in-envelope assembly. Wagner said that the Mail Design Test found statistically significant differences across the treatments, but joined skepticism as to whether they were “important” or practically significant. He observed that each experimental arm of this test had lower response and higher cost, and was designed to reduce burden (the stress imposed by “mandatory” messaging). He suggested that what should be asked is whether the experimental treatments lead to increased nonresponse bias, and whether the trade-off of burden reduction through these treatments is really worthwhile.

Wagner commented that the assumption of population heterogeneity explicitly motivated the Mail Design Test and asked whether different strengths of “mandatory” messaging work differently across population subgroups. He noted work from within the economic programs directorate at the Census Bureau (Thompson and Kaputa, 2017) showing that smaller and larger firms respond differently to mandatory-response messaging in establishment surveys. The questions are whether population subgroups who react differently to different types of messages can be identified ahead of time and, if not, whether they can be identified (and approaches adapted) over the course of survey administration.

Regarding the Adaptive Strategy Test, Wagner acknowledged the finding that, “in some areas, self-response went down” with the move to Internet push methods. Again, he said that the hope is to identify those areas or households in advance, for tailoring survey strategies and approaches. Borrowing terminology

from machine learning, he likened this to a feature selection problem, the construction of some classification algorithm—and, so conceptualized, the question becomes one of whether the predictive accuracy of classification can be improved. He noted that some studies in the literature indicate that offering response-mode choice reduces response—Wagner joined other speakers in citing Medway and Fulton (2012). But he argued that other works in the literature find that this impact can be mitigated by other design features, such as incentivizing response by the Internet; he pointed to work by Biemer et al. (2018) on the Residential Energy Consumption Survey, while conceding that incentives are not really viable for the ACS.

Wagner closed by noting that the Data Slide and Mail Materials Tests both suggest the need for rethinking of objectives and quality metrics. The Data Slide offers interesting information, but it does not directly address concerns over privacy or other reasons why a respondent might knowingly decline to answer the survey. He asked about more direct response to these concerns. Noting that the overall response rate was not different but that there seemed to be some higher Internet take-up, he said that it might be worthwhile to ask whether that translates into meaningful cost reduction.

3.2.4 Floor Discussion

Cynthia Clark (formerly, U.S. Census Bureau) indicated that she was at an international meeting within the last week where the theme emerged that official statistics have to be relevant to an individual in order to build trust. Arguing that the ACS is uniquely positioned to build that kind of trust through its role in the allocation of federal funds, Clark asked: Is it possible to play up that message more in the messaging being provided to respondents? Poehler replied the federal fund argument is referenced in the informational material in the package, but there has not been too much consideration to putting it into the letter. Williams noted that a better approach might be to target the state level in referencing fund allocation, as the national level figure of $685 billion might sound like “wasteful government spending.”