1

Introduction

Although often thought of as an age span, such as the second decade of life or “the teenage years,” adolescence is the distinct period of bio-developmental change in a person’s life that bridges childhood and adulthood. It denotes a set of developmental transitions beginning with the onset of puberty1 and ending during the mid-20s, characterized by maturation of the body, intensification of capacity for learning, and emergence of personal identity. From a social vantage point, the developmental tasks of adolescence include taking responsibility for oneself and forming relationships with others. This period of developmental maturation is underpinned by unique changes in brain structure and function.

All these transitions mark adolescence as a period of both opportunity and risk (see Chapter 2). Parents (or parent surrogates)2 typically bear primary responsibility as caretakers of their children, but the whole society

___________________

1 The average child in the United States experiences the onset of puberty between the age of 8 and 10 years. The onset of puberty may be defined by two biological components, adrenarche and gonadarche. Adrenarche, which refers to the maturation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis typically begins in late childhood, but levels of adrenarchal hormones continue to rise throughout adolescence (Blakemore et al., 2010). Gonadarche typically begins in early adolescence, at approximately ages 9 to 11, and involves the reactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. See Chapter 2 for a full discussion of adolescent development and puberty.

2 In this report, the committee uses the term “parents” to broadly encompass those adults in adolescents’ lives who are their primary caretaker. For some young people, the primary caretaker is a grandparent, aunt or uncle, step-parent, or foster parent, among others.

shares the obligation to help adolescents achieve their full potential in adulthood (Casey et al., 2010; Galván, 2014; Spear, 2010).

In the past, it was thought that the brain was entirely developed before a person entered adolescence and that cognitive functions were fully mature by then. But it is now widely understood that key areas of the brain and its circuitry continue maturing from the onset of puberty and well into an individual’s mid-20s (Giedd et al., 1999; Lenroot and Giedd, 2006). This demarcates adolescence as a sensitive period of neurodevelopment that is especially affected by the environment, including physical factors such as nutrition, trauma, and toxic exposures, as well as social factors such as the influence of parents and caregivers, peers, and teachers (Fuhrmann et al., 2015).

For these reasons, it is important to understand the potentially profound impact that an uneven social distribution of risks and resources can have on youth, privileging some while leaving disadvantaged populations behind (Steinberg, 2014; see also Chapter 4). The challenge for a caring society is to take maximum advantage of the developmental opportunities afforded by adolescence. The remarkable adaptability, plasticity, and heterogeneity of adolescent brains (Ismail et al., 2017) creates accompanying opportunities—and obligations—for individuals and agencies responsible for protecting and serving youth to help all adolescents flourish.

Over the past two decades, advances in neurobiology and neuroimaging have demonstrated the dramatic extent of brain maturation during adolescence. However, as a recent Lancet commission on adolescence has noted, this exciting advance in knowledge has not penetrated the everyday understanding of informed citizens and policy makers, including many who serve young people (Patton et al., 2016). While some youth-serving policies and programs have embraced developmentally informed changes, the wide-scale changes needed to support and bolster adolescents’ development have not yet materialized.

The challenge of educating the public is compounded by a deeply ingrained tendency to view adolescence as mainly a time of vulnerability and risk—a viewpoint that may have been reinforced in recent years by oversimplified headlines about a “mismatch” in the adolescent brain between intensifying desires and emotions (akin to “stepping on the gas”) and a more slowly developing capacity for self-regulation (“stepping on the brakes).” This preoccupation with risk leads to a tendency to attribute risk and vulnerability to developing young people, while overlooking society’s responsibility to protect and support them in their growth. To continue the metaphor, it draws attention to “risky drivers” rather than the conditions of the roads, the presence of guardrails, and the availability of driver education. A preoccupation with risk also leads to a selective valuing of policies and practices that aim to shield adolescents from harm and relative disregard for those that create incentives for discovery and innovation.

A key theme of this report is that recent advances in neuroscientific understanding have been fundamentally misunderstood by large segments of the public. The defining characteristics of the adolescent brain are malleability and plasticity. These attributes may sometimes be worrisome but they also generate unique opportunities for learning, exploration, and growth. Our society needs policies and practices that will help us better leverage these developmental opportunities to harness the promise of adolescence—rather than focusing myopically on containing its risks.

A second important theme of the report—and a major challenge for the nation—is that the promise of adolescence is now unrealized for many of our nation’s adolescents due to deeply rooted structural inequalities that underpin well-documented disparities in developmental outcomes. These structural inequalities include substantial differences in family resources, in the safety and support of neighborhoods, and the occurrence of racial/ethnic bias. (See Chapter 4.) Counteracting and erasing these disparities will require sustained, multipronged, multilevel interventions. Developmental science can tell us what to do, but only a sustained political commitment can enable us to do it.

STUDY CHARGE AND APPROACH

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine appointed the Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications (“the committee”) to prepare a report examining the neurobiological and socio-behavioral science of adolescent development and outlining how this knowledge can be applied to institutions and systems (1) to promote adolescent wellbeing, resilience, and development and (2) to rectify structural barriers and inequalities in opportunity. (See the committee’s full Statement of Task in Box 1-1.) Sixteen prominent scholars and practitioners were included on the committee, representing a broad array of disciplines including neuroscience, developmental and social psychology, economics, sociology, adolescent health and medicine, law, and education and learning. They met and deliberated over a 15-month period to reach the findings presented in this report.

The study builds on the foundation laid by the first study in the National Academy of Medicine’s Culture of Health study series, Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. The Funders for Adolescent Science Translation (FAST) provided funding for this committee’s study and report. FAST members include the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Bezos Family Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the National Public Education Support Fund, the Raikes Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The central charge for the committee was to draw upon research from neurobiological and socio-behavioral science to highlight promising models, opportunities for translations, and policies to better support adolescents (see Chapters 2 through 4); identify research gaps (see Chapter 10); and develop evidence-based recommendations to key stakeholders serving adolescents and their families (see Chapters 6 through 9). Targets for these recommendations include government agencies and community institutions; federal, state, and local policy makers who guide the allocation of resources; and the research community. Taken together, these recommendations are intended to outline a vision in support of positive development for all adolescents.

Successful Development

In undertaking this task, the committee gave much thought to what successful maturation during adolescence entails or requires. How can we best ensure that all adolescents will flourish? A flourishing adolescent experiences high levels of emotional, psychological, and social well-being.3 The psychological and philosophical literature identifies a range of possible indicators of flourishing, including happiness, satisfaction, behavioral flexibility, growth, and resilience in the aftermath of adversity (Fredrickson and Losada, 2005). Many of the current academic discussions of flourishing focus on how best to achieve it. The central challenge is to identify a core set of conditions or capabilities that need to be supported, such as bodily health, bodily integrity, and material control over one’s environment (Nussbaum, 2003, 2011; Sen, 1993, 1999).4

The committee considered a range of capabilities that appear to be central to a flourishing adolescence and determined that the necessary conditions are good health, education, positive socialization, and the fostering of stable, supportive familial and caretaker relationships. Ultimately, the committee regards supporting and promoting flourishing during adolescence as essential for youth to transition into successful adulthood. This report therefore focuses on the youth-serving systems specifically tasked with supporting these capabilities—the health, education, child welfare, and justice systems—and discusses the role of families and neighborhoods in shaping experiences within those systems (see Chapters 6 through 9). While a number of other systems and system-level actors, ranging from religious institutions to law enforcement, also touch the lives of adolescents,

___________________

3 Flourishing is a concept that originated in Aristotle’s discussions of what it means to “do and live well,” and it is embraced as an ideal by political philosophers and psychologists alike. See, for example, Keyes (2002, p. 210).

4 For a useful summary, see https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/capability-approach/.

the systems outlined in the committee’s charge shape many of adolescents’ experiences as they develop and transition into adulthood. Each of them has a profound obligation to implement evidence-informed policies and practices to enable all adolescents to flourish.

The Age Span of Adolescence

In order to interpret the scope of its charge, the committee, inevitably, needed to define the age span of “adolescence.” At the lower boundary, it is generally accepted that the onset of puberty—at approximately ages 10 to 12—signals the beginning of the developmental processes of adolescence. The more consequential question for the committee’s work concerns the upper bound of adolescence. On the one hand, the unique period of brain development and heightened brain plasticity at the heart of the committee’s charge continues into the mid-20s. On the other hand, the socio-emotional changes associated with adolescence (e.g., forming relationships with peers and adults and developing personal identity) occur largely during the teenage years and, in everyday life, graduation from high school and leaving the family home, mark a fairly distinct social transition to “young adulthood,” typically signified by the 18th birthday (the legal “age of majority”). However, as explained in a recent National Academies report, most 18–25 year-olds experience a prolonged period of transition to independent adulthood, a worldwide trend that blurs the boundary between adolescence and “young adulthood,” developmentally speaking.

With these considerations in mind, the committee interprets its charge to encompass youth ages 10 to 25. While there is a growing recognition that young adulthood is a critical life stage in itself, especially in educational and occupational terms, for the purposes of this report, the committee encompasses young adulthood within a broad conception of adolescence. While older adolescents (or young adults) differ greatly in their social roles and tasks from younger adolescents, it would be developmentally arbitrary in developmental terms to draw a cut-off line at age 18.

Although the committee has interpreted its charge as one including young adults (ages 18 to 25), it focuses most of its attention on the needs of adolescents ages 10 to 18), typically those living with their families and attending secondary schools. Thus, some chapters (Chapters 6, 8, and 9) clearly center on a subset of the population, typically because of legal definitions. In Chapters 6 and 9, for example, we focus on secondary schools and the juvenile justice system instead of higher education and the criminal justice system—although both chapters discuss the latter systems to a lesser degree. Because higher education (including technical education) and the criminal justice system are designed to serve individuals of all ages and to effectuate much more complex social purposes than specifically serving ado-

lescents, the committee does not focus the majority of its recommendations on these systems. Moreover, this committee was not constituted to take on the challenges of reforming criminal justice and higher education, notwithstanding the observation that young adults ages 18 to 25 may sensibly be characterized as adolescents from a developmental point of view. (For further understanding of the need to invest in the health and well-being of young adults, see Investing in the Health and Well-being of Young Adults (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014).)

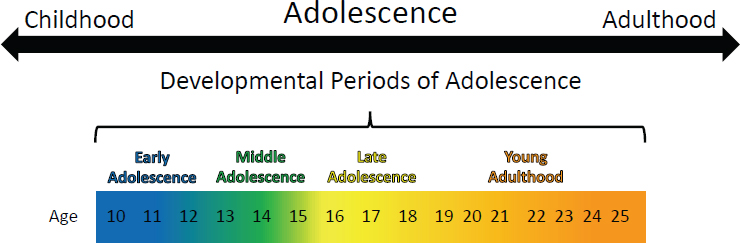

Even within the period of adolescence, much of the literature uses different terms for different phases or stages. In this report, the committee refers to adolescence as encompassing four periods—early adolescence (ages 10 to 12), middle adolescence (ages 13 to 15), late adolescence (ages 16 to 18), and young adulthood (ages 19 to 25). Figure 1-1 visually depicts these periods as shading into one another around these ages, recognizing that they are fluid and based, in part, on socially constructed transition points (e.g., from elementary to secondary school and so on).

The Life-Course Perspective

The well-being of adolescents is shaped by experiences during the prenatal and early childhood years. Fortunately, the prenatal and early childhood periods are already widely recognized to be sensitive times for development. Over the past several decades large-scale investments in supports for young children—such as Early Head Start, Head Start, and home visiting programs—have contributed to broader public awareness of the importance of prenatal and early childhood development in achieving positive outcomes for all young children. Of course, more can be done, as far too many young children enter adolescence bearing the scars of childhood adversity, including toxic stress, exposure to environmental toxins, child maltreatment, food insecurity, and limited access to high-quality early care and education.

A companion National Academies’ study on applying the neurobiological and socio-behavioral science concerning prenatal through early childhood development was under way to address these issues during the time of this committee’s investigations.5 The resulting report discusses programs and policies designed to mitigate adverse prenatal and early childhood conditions during a child’s earliest years. In accordance with our charge, this committee discusses how early life conditions, including supports and adversity, can affect adolescent development and how past developmental challenges may be mediated in adolescence (see Chapter 3). Taken together, the two reports take a life-course perspective, arguing that a strong infrastructure for young children should be extended throughout adolescence to nurture positive development for all children from birth to adulthood.

HISTORY OF ADOLESCENCE

Popular understanding of adolescence as a distinct period of neurobiological and socio-emotional development and of the duration of that period has evolved over time, shaped by social and cultural change. The first use of the word “adolescence” appears to have occurred in the 15th century, the word being derived from the Latin adolescere, meaning “to grow up or to grow into maturity.” However, the word and the concept only gained widespread popular use at the turn of the 20th century, first in the United States and later in other Western countries. Psychologist G. Stanley Hall characterized adolescence as a “new” developmental phase resulting from social changes brought about by the industrial revolution and the introduction of public schooling occurring during the Progressive era, when reformers were advocating for compulsory education and legal restrictions on child labor (Arnett and Cravens, 2006; Hall, 1904). Yet nearly 90 years after Hall’s observations, anthropologists Alice Schlegel and Herbert Barry documented evidence that the vast majority of pre-industrial societies throughout human history appear to have recognized a period that corresponds to adolescence, that is, a period when a person is no longer a child but is not yet an adult (Schlegel and Barry, 1991). More recently, anthropologists Carol Worthman and Kathy Trang have documented the biological-social mismatch that has been associated with increasingly younger ages of physical maturation accompanied by older ages of social maturation around the world, pointing to an increasingly globalized cultural construction of adolescence (Worthman and Trang, 2018).

___________________

5 For more information on the Committee on Applying Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Sciences from Prenatal through Early Childhood Development: A Health Equity Approach, see www.nationalacademies.org/earlydevelopment.

While a period of adolescence may have been recognized across time and culture, and a global understanding may now be emerging (Worthman and Trang, 2018), Hall’s observations a century ago about the impact of the industrial revolution in the United States are still salient. Taking young people out of the workplace and placing them in schools erased the expectation that young teens would become “bread earners” and, instead, prolonged their dependence on their parents and families. Moreover, this change gave them an opportunity to form their own peer groups. A side effect of this change was the opportunity for adolescents to experience a period of social development and freedom without the responsibilities of adulthood.

Spurred by post-World War II economic expansion, as of mid-century a discernible youth culture had emerged in the United States, defined by distinct youth styles, behaviors, and interests. The latter half of the 20th century saw the rise of youth engagement in and creation of social and political movements, including student-led civil rights protests, anti-Vietnam War protests, and divestment and anti-apartheid initiatives, through which adolescents exerted agency and actively sought to change the contexts in which they lived.

Beginning in the late 20th century and into the early 21st century, society began to recognize the emergence of “young adulthood,” sometimes thought of as an extension of adolescence. In Investing in Young Adults (2014), a committee of the National Academies suggested that young adulthood should be viewed as a distinct developmental period, reflecting the social and economic developments that have prolonged the transition to independent adulthood. For the purposes of this report, however, our committee encompasses young adulthood within a prolonged period of adolescence.

The 21st-century blurring of the age of adulthood reflects a larger point: that conceptions of when and how adolescence begins and ends are, in part, socially constructed and vary across time and place. Currently, we understand adolescence as beginning with the onset of puberty and ending when young people take on various socially defined tasks signifying adulthood. Due to trends toward earlier onset of puberty and changing societal dynamics around the commencement of adulthood, adolescence, which once lasted only a matter of years, is now conceived as a much longer period—lengthened at the beginning by the earlier onset of puberty and at the end by the increasingly protracted transition of young people into careers, marriages, and financial independence (Steinberg, 2014).

Ideas about the upper boundary of adolescence are also socially determined. They are connected to familial, social, legal, and cultural expectations regarding what it means to be an adult, and the point in time when youth “become adults” may be, and historically has been, defined in a

variety of ways.6 Today, included among the tasks signifying a successful transition to adulthood are completing postsecondary education, gaining financial independence, starting a career, and getting married. It is therefore of real consequence that these milestones are continually shifting. For example, Americans were delaying marriage, on average, until the age of 29 as of 2011; delaying child bearing, with the median age of first birth for females being 26.7, in 2015; and looking to their parents for continued financial support, with over half of 18–24-year-olds living with their parents in 2015.

With the onset of puberty happening earlier and earlier and marriage occurring later and later, adolescence in the United States now lasts roughly 15 years. While this lengthening has increased for all Americans, there is great variation in how the period has elongated. Puberty is most often beginning earlier among the nation’s poorest children, while the transition to adulthood is increasingly delayed for more affluent adolescents, who are more likely to pursue higher education and delay marriage and parenthood (Steinberg, 2014). This pattern is extremely important, because early life experiences, including social risks and disadvantages, have been shown to lower the age of pubertal timing, whereas delayed adulthood elongates the period of novel experiences and learning. As a result, longer adolescence benefits the privileged far more than the underprivileged (Steinberg, 2014, p. 177).

CONTEMPORARY ADOLESCENTS

Today’s adolescents are growing up in remarkable times. At least since the industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries, each new generation has faced a progressively modernizing world with changing expectations and opportunities for young people (e.g., see Modell, 1991). This appears to be accelerating, as adolescents in the 21st century are experiencing sometimes dramatic shifts in the social, cultural, economic, and technological environments. As they navigate their adolescent years and emerge into adulthood, demographic shifts are altering community and family life in fundamental ways. For example, today’s youth population in the United States is more culturally and ethnically diverse than ever before, while at the same time

___________________

6 For example, legal rights associated with adulthood vary in age both across and within societies. In the United States, society imposes different legal ages for driving (ranging from ages 14 to 17 among some U.S. states, with a range of restrictions on driving and age to receive full license across states), military service (age 18, or 17 with parental consent), marriage (typically age 18, with some states allowing marriage at younger ages with parental or judicial consent), voting (typically age 18, or in recent years, 16 in some countries and U.S. localities), and drinking alcohol (age 21 in the United States. but younger in many other countries). Each of these has been in some way and in certain times a marker of adulthood.

inequalities in income and opportunity among youth continues to increase. Perhaps no societal development will have a greater impact on the lives and well-being of adolescents in the 21st century than the digital revolution. Finally, although it is still too early to predict the precise effects, the polarization and intensity of political discourse in the United States and what appears to many young people as a battle for national identity are bound to have a long-term impact on current and future cohorts of adolescents.

Demographic Trends

Adolescents currently represent nearly one-fourth of the entire U.S. population. According to the Census Bureau, there were approximately 73.5 million adolescents ages 10 to 25 in 2017, representing 22.6 percent of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018b).7 While in raw numbers the size of the adolescent population has grown recently, it is now declining slightly as a proportion of the population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018b). Based on a projected continued decline in fertility as well as the continued aging of the population, this trend is likely to continue for several more decades (Colby and Ortman, 2014). According to U.S. Census projections, youth (10 to 24 years old) are expected to comprise about 18 percent of the population in 2040.8 Immigration is projected to slow a little as well, although the percentage of the population that is foreign-born is expected to rise, albeit more slowly than it has been rising in recent years (Colby and Ortman, 2014).

The composition of the U.S. population overall, as well as among adolescents, has also become more racially and ethnically diverse; the U.S. population as a whole is expected to become minority majority, that is, with more than half belonging to a category other than non-Latinx White alone, by 2044 (Colby and Ortman, 2014). Because this is expected to occur more quickly among children under 18, the crossover from minority

___________________

7 Although females outnumber males at older ages, males in this age range constitute a very slight majority (51%) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018b). In the 2010 Census, 56 percent of 10–24-year-olds were non-Latinx White, 21 percent were Latinx (of any race), 14.5 percent were Black or African American, 4.6 percent were Asian, 2.6 percent reported two or more races, and less than 1 percent each were American Indian/Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018a). Just over 90 percent of adolescents are native-born; the remainder are a mix of naturalized citizens and both documented and undocumented immigrant non-citizens (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). More than one-quarter of children in the United States had at least one foreign-born parent in 2014; 22 percent were second generation, that is, native-born but with at least one foreign-born parent (Child Trends, 2014).

8 In 2040, it is estimated that there will be 66.1 million adolescents (10–24-year-olds) in the United States, or roughly 18 percent of the population. (See Table 3, National Population Projects Tables, U.S. Census, 2017, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html).

to majority of the population for adolescents ages 10 to 25 should occur much sooner, by 2020.

These broad trends intersect with several other key aspects of adolescents’ lives that are changing due to demographic trends in the overall population: the socioeconomic status of their families, and thus their own status; how and where they live, including not only migration but also the family and institutional structures they live in; and the shifting landscape of their education as well as their employment and work experiences (adolescents’ education and employment are discussed in detail in Chapter 6).

For most adolescents, socioeconomic status is linked to the status of their families. Poverty rates for families have been dropping in recent years following the Great Recession, falling from 13.2 percent in 2010 to 10.3 percent in 2017 (Fontenot et al., 2018). Poverty rates vary substantially across racial/ethnic groups, with 6.3 percent of non-Latinx White families, 7.7 percent of Asian families, 16.9 percent of Latinx families, and 19.0 percent of Black families living below the poverty line in 2017. Single-mother families have especially high rates of poverty, at almost 28 percent; one-third of Black and Latinx single-mother families were in poverty in 2017.

Youth today are also more likely to live in urban areas than in the past, a trend that has been observable for adolescents over the past 35 years. Data from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) surveys,9 which ask adolescents where they mostly grew up, shows a decline in the percentage of those reporting that they grew up on a farm or in the country, from 24.7 percent in 1976 to 16.5 percent in 2012 (Bachman et al., 1980, 2014). More adolescents have reported over time that they were living in cities or in suburbs of medium-sized cities (fewer than 100,000 people). White adolescents are much more likely to report living or having grown up on farms or in the country than are Black adolescents, and also more likely to report living in small cities or suburbs; Black adolescents report living in medium, large, or very large cities more often.

Technology and the Digital Revolution

These demographic and social changes are happening alongside and often intertwined with an extraordinarily fast-paced changing world of technology, all in the context of shifting political and economic change. Through the Internet and social media, youth have broad access to information and ideas in ways that were never before possible, giving rise to new forms of digital community among youth, as well as new forms of social

___________________

9 The Monitoring the Future surveys are funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. MTF is an ongoing study of the behaviors, attitudes, and values of American secondary schools students, college students, and young adults.

action and interaction. An example of the latter is the leading role youth have taken in social movements in response to gun violence. Taken together, these broad trends have global as well as local impacts and make up the broader context for the typical developmental changes that characterize the period of adolescence for all youth.

For adolescents, the technological and digital revolution have become a key context of their development, permeating nearly every aspect of their lives. In a recent survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, researchers found that approximately 76 percent of adolescents surveyed use social media, with 45 percent indicating that they are almost always online, whether by phone or computer. When these numbers are broken down by gender and race and ethnicity, they show that girls were more likely than boys (50% vs. 39%) to identify as being “almost constantly” online, as were Latinx youth when compared to Whites (54% vs. 4%) (Anderson and Jiang, 2018).

Given adolescents’ near-constant interaction with digital technology, it is important to understand the ways in which this engagement may present opportunities for positive development, as well as potential risks. For example, engagement online and with digital media may help adolescents achieve a healthy level of autonomy by providing opportunities to associate with peers and cultures they might not otherwise encounter in their daily lives, opening the door to new interests (e.g., music, writing, coding, sports), which could benefit them as they move into adulthood (Boyd, 2014; Ito et al., 2008). This type of engagement can also provide a new way for youth to build social networks. LGBTQ youth, for example, are able to connect with each other and build supportive and empowering communities in ways that were unavailable to previous generations (Hammack, 2018). Further, in addition to forming new relationships, research suggests that online contact among young people’s existing social networks reinforces the bonds that are made offline, making them feel more connected and supported by their peers and families (Uhls et al., 2017).10

Notwithstanding the many worries that have been expressed about the possible detrimental effects of social media consumption on overall adolescent well-being, strong evidence documenting such effects has not yet emerged (Orben and Przybylski, 2019). Some specific reasons for concern are generally acknowledged, however. In recent years, bullying has been

___________________

10 While much of popular reporting today suggests that adolescents’ use of digital and social media may be creating tension between parents and youth, research is mixed about the impact of technology on family relationships. While some research has found that technology may create a barrier and limit communication with parents, there is also evidence that the use of social media, texting, and other communication technologies may offer new ways for parents and children to relate and communicate (Lee, 2009; Schwartz et al., 2014; Subrahmanyam and Greenfield, 2008).

increasingly moving from the schoolyard to the Internet. While previous generations could usually find refuge once at home, the public nature of cyberbullying makes it difficult for youth to escape, which in turn can increase the risk of mental health issues such as depression and anxiety (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). According to a recent study on adolescent well-being and social media, an adolescent’s ability to cope with bullying plays a significant role in social media’s overall impact on well-being (Schwartz et al., 2014; Subrahmanyam and Greenfield, 2008; Weinstein, 2018).

Adolescents are also at risk of negative consequences when sharing information online. Whereas in previous generations, such actions were often easily forgotten in time, for today’s youth online personal histories become part of that person’s digital footprint, which often remains connected to their name long after an initial posting (Madden et al., 2007). Laws such as the Privacy Rights for California Minors in the Digital World help by giving adolescents under age 18 the right to remove posted material, but not all states provide such protection (Costello et al., 2016). The federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998 also provides some protection, but only for youth under age 13.

The rapidly changing nature of communications technology and the influx of digital media will continue to shape young people’s development, and this context for development presents both opportunities and potential risks, making understanding the role of technology in adolescents’ lives a critical area of future research; see Chapter 10. Moreover, technology presents another context with the potential to increase inequities as not all youth have access to the benefits of digital technologies, such as youth from low-income or rural households who may be unable to access high-speed Internet at home (Anderson and Perrin, 2018).

Civic Engagement

Another potentially significant trend among 21st-century adolescents in the United States is a burst of civic engagement, somewhat reminiscent of the period of dissent during the Vietnam conflict and the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Youth today are engaging in multiple forms of “participatory politics” to amplify their voices on issues of public concern, and increasingly they are doing so through digital media (Cohen, et al., 2012). Indeed, young people are exercising agency and capitalizing on technology as a new forum for political engagement (Finlay et al., 2010; Smith, 2013). In a recent Pew Research Center survey, two-thirds of all 18–24-year-olds reported participating in some sort of political activity in social networking spaces during the past 12 months (Smith, 2013). Young people have been major contributors to the Occupy movement and other

attempts to raise awareness about inequality and promote policies that support greater equity. Through movements such as Black Lives Matter, which encompasses intersecting axes of racial and economic oppression, young people are at the forefront of advancing an intersectional approach to combatting systemic inequity and discrimination. Political organizing for school safety and reducing gun violence is another recent example.

Volunteering to serve others is another measurable indicator of civic engagement. Among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the MTF surveys, 27.1 percent, 34.4 percent, and 38.8 percent (respectively) reported volunteering at least once per month in 2015 (Child Trends, 2015). However, rates of volunteering and other forms of civic behavior tend to drop when young people enter their early twenties and are no longer enrolled in high schools or colleges (Finlay et al., 2010). Similarly, 18–24-year-olds’ voting rates are consistently lower than those of older age groups, although early analyses of returns from the 2018 election show increased rates (File, 2014; Langer and Siu, 2018).

Much like the patterns observed among adults, for whom civic engagement is positively correlated with educational attainment, adolescents who plan to complete 4-year college degrees are more civically involved than those with plans for 2-year degrees or no higher education, as are those whose parents have higher levels of education (Syvertsen et al., 2011). Notably, this gap has been growing since the early 1990s (Syvertsen et al., 2011). Wray-Lake and Hart (2012) report a growing gap specifically in voting behavior by education level across cohorts, but not in other conventional political activities (such as attending meetings, donating money, working for a campaign, or wearing a button for a candidate). Females and minorities of all ages are less likely to engage in political activities (other than voting), although holding socioeconomic status and other demographic characteristics constant, Blacks have higher levels of political participation than do Whites (Fisher, 2012). Despite patterns of lower levels of political engagement among members of historically marginalized groups, in the United States there has been a recent uptick in the number of women, openly LGBTQ+ people, and (importantly for this report) young people elected to political positions (Caron, 2018; DeSilver, 2018).

In summary, the explosion of new communication technologies and the positive as well as compromising possibilities they offer, together with the shifting access to and demands for civic engagement that are now emerging, not only comprise key contexts shaping adolescents’ lives today but also suggest the agency of young people. In each context, adolescents are themselves actively influencing change in their lives and communities, while at the same time shaping the experiences and environments of their development.

THE PROMISE OF ADOLESCENCE

Having reviewed the background and context for the report as well as the characteristics of 21st-century adolescents and the world they inhabit, we return now to the committee’s basic assignment and the core themes of the report.

Adolescence is a developmental stage in which heightened neurosensitivity and normative changes in neural and hormonal development intersect with changes in young people’s social, technological, and cultural environments, opening a critically important gateway to adulthood. Brain development is complex and ongoing throughout childhood and adolescence, with different parts of the brain experiencing major changes at different times. The nature of these changes—in brain structures, functions, and connectivity—and the developmental plasticity unique to this period of life—present remarkable opportunities for learning and growth as well as amelioration of the harmful effects of childhood exposures.

While humans retain a baseline level of neuroplasticity required for experience-based learning throughout their lives, adolescent brain circuitry is exceedingly adaptable and “experience-dependent,” which means that adolescents are specially primed to learn from their particular circumstances and environments during this period (Fuhrmann et al., 2015). (See Chapter 2 for a full discussion of the developing adolescent brain.) In addition to being a period of profound cognitive transformation, adolescence is also a time of numerous biological, psychosocial, and emotional changes (see Chapter 2). The changes in the body, the brain, and behavior occurring during adolescence are interrelated and interact with one another and with the environment to shape the adolescents’ pathways to adulthood.

Because pubertal, neurological, cognitive, and psychosocial changes are occurring, adolescence is a critical period of opportunity to shape developmental trajectories. With this growth and learning, each new experience is an opportunity for the adolescent to discover new interests, develop new skills, and otherwise flourish. This heightened sensitivity and responsiveness to environmental influences also suggests that adolescence is a period during which interventions—at both the individual and societal levels—may be used to redirect and remediate maladaptation in brain structure and behavior from earlier developmental periods, that is, to achieve resilience (see Chapter 3). Adolescence therefore holds great promise to realize positive trajectories for all youth.

THE POLITICAL CHALLENGE

Here, then, lies the political challenge. How does a caring society take advantage of this critical developmental opportunity in a world character-

ized by substantial—and worsening—disparities in resources, safety, social supports, and other necessary conditions of well-being for children and adolescents? Widening income and wealth inequality in the United States has placed individuals and families that are at the lower end of the socioeconomic distribution at a historically great distance from those at the top end of the distribution (Chetty et al., 2017; Piketty and Saez, 2014). Economic inequality poses unique challenges to young people across the socioeconomic distribution and is also strongly associated with other measures of inequality.

It is well documented that economic inequality strongly influences the opportunities available to adolescents from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Greater inequality often accompanies more severe residential segregation, such that young people from families with lower incomes and less wealth, and often families from nondominant racial groups, live in communities that are increasingly isolated and separated from economic and educational opportunities (Ananat, 2011; Oliver and Shapiro, 2006; Owens, 2016; Quillian, 2014; Reardon and Bischoff, 2011). In addition to this unequal and reduced access to resources, inequality contributes to the way young people perceive themselves, their place in the world, and the possibilities for their futures.

It is now understood that these inequalities shape individuals’ developmental trajectories by “getting under the skin.” For example, adolescents living in poverty often experience heightened levels of stress, which can lead not only to short-term changes in observable behavior but also to long-lasting changes in brain structure and function and in connectivity within the brain (see Chapter 3). While some of these changes may help an adolescent adapt to their particular social and physical environment, they may also make it more difficult to function in another environment should conditions change. In this way, key experiences interact with fundamental neurobiological processes to shape developmental trajectories.

The salience of environmental influences in shaping development during adolescence, together with the critical developmental importance of adolescence, make a powerful case for remedial action. The nation should ensure that all adolescents have a genuine opportunity to flourish, not only as an expression of a collective sense of justice but also as an investment in the nation’s future.

STUDY METHODS

To understand the science of adolescent development and its applications, the committee reviewed the existing research literature in disciplines such as neuroscience, developmental and social psychology, adolescent health and medicine, and education and learning. To understand the roles,

structures, policies, practices, and effects of social systems, we also reviewed pertinent research in social and behavioral sciences, law, and public policy. The committee held four in-person meetings and conducted additional deliberations by teleconference and electronic communications during the course of the study. The first and second in-person meetings were information-gathering meetings during which the committee heard from a variety of stakeholders, including the study’s sponsors, youth, researchers and scholars, and policy makers from the federal, state, and local levels. The third and fourth meetings were closed to the public to enable the committee to deliberate and to formulate its conclusions and recommendations.

Recognizing that the lived experience of young people represents an important form of evidence itself, the committee sought to hear the voices of young people in a variety of ways. First, the committee invited six adolescents from a range of backgrounds to speak at a public session in June 2017. These young people described their experiences in the foster care and juvenile justice systems as well as the health and education systems, commented on the impact on their lives of ever-changing access to technology and social media, and reflected on their hopes for the future. Second, the committee commissioned an analysis from the University of Michigan’s My Voice program to understand adolescents’ own perceptions of this period of life as well as their perspectives on inequality in their communities.11 Finally, the committee invited the Maryland Youth Advisory Council to assemble a “youth reflection panel” to comment on possible committee recommendations. In the course of all of these activities, the committee heard from youth about their priorities for the future and the greatest challenges they currently face. The insights the committee garnered from these activities are included throughout the report in text boxes highlighting “Youth Perspectives” as well as in Appendix B.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The committee’s report is organized into two parts and 10 chapters. Part I conveys the scientific findings that serve as a foundation for the report. Following this introduction, Chapter 2 summarizes the scientific literature on adolescent development, including biological, neurological, and socio-behavioral changes that show why we characterize adolescence as a period of opportunity. Chapter 3 describes the emerging science of epigenetics and the ways in which the brain, body, and environment interact to shape life-course trajectories. Chapter 4 concludes Part I by summarizing the evidence bearing on the extent to which different groups of ado-

___________________

11 MyVoice is a text-message based survey of 1,480 young people (ages 14 to 24) across the United States. The program’s methodology is described in DeJonckheere et al. (2017).

lescents are—and are not—achieving important developmental outcomes and highlights variations in achievement among different subpopulations of youth, posing the fundamental challenge we were asked to address—how can deploying knowledge of adolescent development help us rectify these disparities?

Part II begins with Chapter 5, which introduces the concept of using developmental knowledge to assure opportunity for all youth. Chapters 6, 7, 8, and 9 then focus on four key youth-serving systems—education, health, child welfare, and justice—in order to answer the question that lies at the heart of our charge: How can these systems be changed to help all adolescents flourish? Each of these chapters also discusses the ways in which families, neighborhoods, and communities can most successfully interact with each system to improve the process and outcomes of adolescent development.12 Finally, Part II concludes with Chapter 10, in which the committee outlines several priorities for research on adolescent development.

___________________

12Appendix A explains the committee’s approach to assessing the evidence. Appendix B summarizes the committee’s activities to hear from adolescents themselves and to learn from their lived experiences. Appendix C provides biographical sketches of the committee’s members and staff.