2

Adolescent Development

Adolescence is a period of significant development that begins with the onset of puberty1 and ends in the mid-20s. Consider how different a person is at the age of 12 from the person he or she is at age 24. The trajectory between those two ages involves a profound amount of change in all domains of development—biological, cognitive, psychosocial, and emotional. Personal relationships and settings also change during this period, as peers and romantic partners become more central and as the adolescent moves into and then beyond secondary school or gains employment.

Importantly, although the developmental plasticity that characterizes the period makes adolescents malleable, malleability is not synonymous with passivity. Indeed, adolescents are increasingly active agents in their own developmental process. Yet, as they explore, experiment, and learn, they still require scaffolding and support, including environments that bolster opportunities to thrive. A toxic environment makes healthy adolescent development challenging. Ultimately, the transformations in body, brain, and behavior that occur during adolescence interact with each other and with the environment to shape pathways to adulthood.

Each stage of life depends on what has come before it, and young people certainly do not enter adolescence with a “blank slate.” Rather, adolescent development is partly a consequence of earlier life experiences. However, these early life experiences are not determinative, and the adaptive plasticity of adolescence marks it as a window of opportunity for change

___________________

1 The average child in the United States experiences the onset of puberty between the age of 8 and 10 years.

through which mechanisms of resilience, recovery, and development are possible. (Chapter 3 discusses this life-course perspective on development in detail.) This chapter explores three key domains of adolescent development: puberty, neurobiological development, and psychosocial development. Within each domain, we highlight processes that reflect the capacity for adaptive plasticity during adolescence and beyond, marking adolescence as a period of unique opportunity for positive developmental trajectories.

PUBERTY

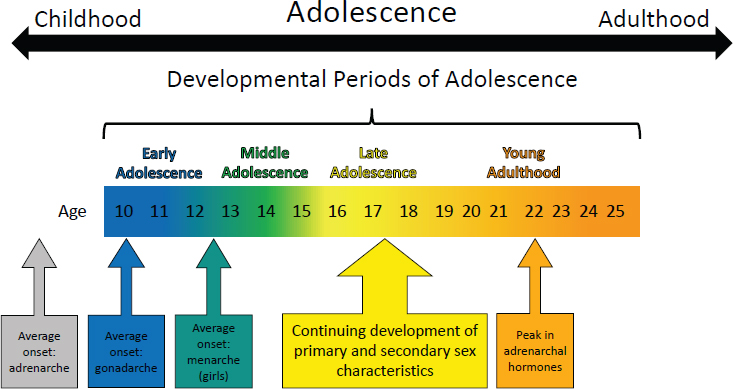

Puberty, a normative developmental transition that all youth experience, is shaped by both social and biological processes. Although often misconstrued as an abrupt, discrete event, puberty is actually a gradual process occurring between childhood and adolescence and one that takes many years to complete (Dorn and Biro, 2011). Biologically, puberty involves a series of complex alterations at both the neural and endocrine levels over an extended period that result in changes in body shape (morphology), including the maturation of primary and secondary sex characteristics during late childhood and early adolescence and, ultimately, the acquisition of reproductive maturity (Dorn and Biro, 2011; Natsuaki et al., 2014).

Two biological components of puberty, adrenarche and gonadarche, are relevant in understanding the link between puberty and adolescent wellbeing. Adrenarche, which typically begins between ages 6 and 9, refers to the maturation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, during which the levels of adrenal androgens (e.g., dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate) begin to increase. While adrenarche begins in late childhood, levels of adrenarchal hormones continue to rise throughout adolescence, peaking in the early 20’s (Blakemore et al., 2010). Adrenal androgens contribute to the growth of pubic and axillary hair. Gonadarche typically begins in early adolescence, at approximately ages 9 to 11, and involves the reactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis (for a review, see Sisk and Foster, 2004).2 The rise of gonadal steroid hormones to adult levels occurs as a result of HPG reactivation and is primarily responsible for breast and genital development in girls.

___________________

2 HPG hormones can bind within cell nuclei and change the transcription and expression of genes to regulate further hormone production, brain function, and behavior (Melmed et al., 2012; Sisk and Foster, 2004). The process begins in the brain when a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is secreted from the hypothalamus. The activation of GnRH is not unique to the pubertal transition; GnRH is also active during pre- and perinatal periods of development but undergoes a quiescent period during the first year of postnatal life until it reawakens during the pubertal transition. GnRH stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormones (FSH), which then stimulate the ovary and testes to secrete estradiol and testosterone.

The consequence of these complex changes in HPA and HPG axes at the neuroendocrine level is a coordinated series of visible, signature changes in body parts. These include a growth spurt, changes in skin (e.g., acne) and in body odor, the accumulation of body fat (in girls), the appearance of breast budding (in girls) and enlargement of testes and increased penis size (in boys), the growth of pubic and axillary hair, the growth of facial hair (in boys), and the arrival of the first period (i.e., menarche, in girls). Key pubertal events are highlighted in Figure 2-1; however, as discussed next, there is a great deal of variation in the timing and tempo of these events.

It is useful to distinguish three distinct yet interrelated ways to conceptualize individual differences in pubertal maturation. Pubertal status refers to how far along adolescents are in the continuum of pubertal maturation at any given moment. For instance, if an 11-year-old girl has just experienced menarche, she is considered to have advanced pubertal status because menarche is the last event that occurs in the process of the female pubertal transition. Pubertal status is inherently confounded with age, because older adolescents are more likely to have attained advanced pubertal status.

Pubertal timing, on the other hand, refers to how mature an adolescent is when compared to his or her same-sex peers who are of the same age. In other words, pubertal timing always includes a reference group of one’s peers. For example, a girl who experiences menarche at age 10 may be an earlier maturer in the United States, because her menarcheal timing is earlier than the national average age for menarche nationwide, which was found to be 12.4 years in a cohort of girls born between 1980 and 1984 (McDowell et al., 2007). Only 10 percent of girls in the United States

are estimated to have experienced menarche before 11.11 years of age (Chumlea et al., 2003), suggesting that the girl in this example would be considered to have early pubertal timing. Unlike pubertal status, pubertal timing is not confounded by age because, by definition, pubertal timing is inherently standardized within same-sex, same-age peers typically residing in the same country.

Pubertal tempo is a within-the-individual metric that refers to how quickly a person completes these sets of pubertal changes. For example, some boys may experience a deepening of their voice and the development of facial, axillary, and pubic hair all within a matter of months, whereas other boys may have a gap of several years between voice-deepening and the development of facial hair. Pubertal tempo has gained more attention recently with the rise of sophisticated longitudinal methodology and the resulting availability of longitudinal data on pubertal maturation (e.g., Ge et al., 2003; Marceau et al., 2011; Mendle et al., 2010).

Regardless of the metric used, most of the research on adolescent pubertal development has focused on girls. We know comparatively little about the processes, correlates, and outcomes of pubertal maturation in boys, except for the well-replicated findings that girls typically begin and complete puberty before boys. Evidence is now emerging that the relationship between puberty and structural brain development in the amygdala and hippocampus region may differ by sex (Satterthwaite et al., 2014; Vijayakumar et al., 2018). These sex differences in associations between brain development and puberty are relevant for understanding psychiatric disorders characterized by both hippocampal dysfunction and prominent gender disparities during adolescence.

It is also important to consider the pubertal development of transgender and gender-nonconforming youth. Transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals usually identify as a gender other than the one they were assigned at birth (Sylvia Rivera Law Project, 2012). Individuals who are gender-nonconforming may identify as transgender, genderqueer, gender-fluid, gender-expansive, or nonbinary. Puberty is a time that can be enormously stressful, and the fear of developing—or the actual development of—secondary sexual characteristics that do not match a child’s gender identity can be intense and even destabilizing (de Vries et al., 2011). Some transgender and gender-nonconforming youth might take medications that block puberty. Although puberty blockers have the potential to ease the process of transitioning, the long-term health effects of these drugs are not yet known (Boskey, 2014; Kreukels and Cohen-Kettenis, 2011).

The Role of Early Experiences on Pubertal Timing and Tempo

As noted earlier, the timing and rate of pubertal development vary greatly. The age at which someone matures is due to a combination of genetic and environmental influences (e.g., Mustanski et al., 2004). Early life experiences, including social risks and disadvantages, have been shown to accelerate pubertal tempo and lower the age of pubertal timing (Marshall and Tanner, 1969). Specifically, accelerated pubertal tempo and early pubertal timing have been associated with stressors, including childhood sexual abuse and physical abuse, obesity, prematurity, light exposure, father absence, and exposure to endocrine disruptors (such as chemicals in plastics, pesticides, hair-care products, and many meat and dairy items) (see e.g., Steinberg, 2014, pp. 54–55). This section reviews the literature on associations between these early experiences and normative variations in pubertal timing and tempo. We close this section with a brief discussion of these associations as a marker of adaptive plasticity.

Maltreatment

One of the most widely studied early experiences related to pubertal development is child maltreatment, and in particular, sexual abuse. A series of studies shows that the age of menarche tends to be lower for girls who experienced child sexual abuse as compared to girls who have not experienced this (Bergevin et al., 2003; Natsuaki et al., 2011; Romans et al., 2003; Turner et al., 1999; Wise et al., 2009). Trickett and Putnam (1993) suggested that the trauma of child sexual abuse introduces physiological as well as psychological consequences for children, including accelerated maturation by premature activation of the HPA and HPG axes. In addition, some studies have observed a relationship between childhood physical abuse and early maturation, though less robustly and less consistently than for sexual abuse (Bergevin et al., 2003; Wise et al., 2009), and these studies do not always control for the possibility of concurrent sexual abuse (e.g., Romans et al., 2003).

In one of the few studies to examine pubertal development longitudinally in adolescents with maltreatment histories, Mendle and colleagues (2011) followed a sample of 100 girls in foster care at four points in time over 2 years, beginning in the spring of their final year of elementary school. The previously established association between sexual abuse and earlier onset of maturation and earlier age at menarche was replicated, and in addition, physical abuse was found to be related to a more rapid tempo of pubertal development. A recent longitudinal study of 84 sexually abused girls and matched-comparison girls replicated the association between sexual abuse and earlier pubertal onset (including breast development and pubic

hair; Noll et al., 2017). Further, using this same sample, childhood sexual abuse predicted earlier pubertal development which, in turn, was associated with higher levels of internalizing symptoms such as depression and anxiety concurrently and 2 years later (Mendle et al., 2014). A third study with this sample found that earlier-maturing girls were more anxious in the pre- and peri-menarche periods than their later-maturing peers; however, their anxiety declined after menarche, suggesting a time-limited effect on mental health and the potential for recovery upon completion of pubertal maturation, as girls enter later adolescence (Natsuaki et al., 2011).

The association between sexual abuse and earlier pubertal development was recently replicated using a large population-based sample of adolescents, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health3 (N = 6,273 girls). In that study, child sexual abuse predicted earlier menarche and development of secondary sexual characteristics, whereas other types of maltreatment did not (Mendle et al., 2016). The distinctive role for early pubertal timing suggests that the heightened sexual circumstances of puberty may be especially challenging for girls whose lives have already been disrupted by adverse early experiences, yet also suggests a potential opportunity for intervention and resilience, particularly in later adolescence, once pubertal development is complete. However, the vast majority of research in this area has focused solely on girls, and we know very little about whether maltreatment is also associated with earlier pubertal timing in boys.

Other Family and Health Factors

Other family factors that may be stress-inducing yet much less extreme than maltreatment have also been associated with pubertal timing and tempo. For example, Quinlan (2003) found that the number of caretaking transitions a child experiences was associated with earlier menarche. Sung and colleagues (2016) found that exposure to greater parental harshness (but not unpredictability) during the first 5 years of life predicted earlier menarche; and a recent meta-analysis found that father absence was significantly related to earlier menarche (Webster et al., 2014), although genetic confounding may play a role in this association (Barbaro et al., 2017).

Health factors that may affect the metabolic system are also predictive of pubertal timing. For example, in girls, low birth weight (Belsky et al., 2007) and obesity/higher body mass index (BMI) (Wagner et al., 2015) have both been associated with earlier pubertal maturation. For boys, overweight (BMI ≥ 85th and < 95th percentile) has been associated with earlier pubertal maturation, whereas obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) was associ-

___________________

3 For more information on the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, see https://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth.

ated with later pubertal maturation (Lee et al., 2016), suggesting a complex association between aspects of the metabolic system and puberty in boys.

Environmental Exposures

Recently, researchers have examined whether a child’s exposure to chemicals is related to pubertal maturation by serving as an endocrine disruptor (see e.g., Lomniczi et al., 2013; Simonneaux et al., 2013; Steingraber, 2007). In the first longitudinal study of age of pubertal timing and exposure to persistent organic pollutants—chemicals used in flame retardants—researchers found that the age at pubertal transition was consistently older in participants who were found to have higher chemical concentrations in collected blood samples (Windham et al., 2015). The effects of neuroendocrine disruptors on girls’ pubertal timing may begin during the prenatal period, as there is evidence that female reproductive development is affected by phthalate or bisphenol A exposure during specific critical periods of development in the mother’s uterus (Watkins et al., 2017).

Accelerated Maturation and Adaptive Plasticity

It is clear that early experiences can factor into accelerated pubertal timing and tempo, and theorists suggest that this may be adaptive. According to Mendle and colleagues (2011, p. 8), “age at certain stressful life transitions represents a dose-response relationship with maturation, with earlier ages at these events associated with earlier development (e.g., Ellis and Garber, 2000).” Belsky et al. (1991) posited that children who are raised in harsh, stressful environments may have accelerated pubertal development to compensate for a mistrust of commitment and of investment in social relationships. According to Belsky and colleagues, early pubertal timing may serve the evolutionary biological purpose of elongating the window for reproductivity and fertility, to permit more conceptions in a lifetime. Thus, the well-documented association between adverse early life experiences and early pubertal development may itself be an adaptive response, one that reflects the plasticity in neurobiological systems during adolescence to adapt to the specific socio-cultural context.

The Social Context of Pubertal Maturation

Despite the role that stressful early life events play in accelerating pubertal timing, it is important to note that adolescence is also a period of potential for recovery. Even when an adolescent has experienced early adversity and this has precipitated earlier pubertal maturation, the social context in which that adolescent is developing can ultimately change the trajectory

of their outcomes—for better or worse. For example, closer and less conflict-laden parent-child relationships can reduce associations between pubertal maturation and behavior problems, while more conflict-laden and less close relationships exacerbate them (Booth et al., 2003; Dorn et al., 2009; Fang et al., 2009). Parental knowledge of an adolescent child’s whereabouts and activities also plays a role, as the influence of pubertal timing on problematic outcomes is weakened when such parental knowledge of adolescent whereabouts and activities is high, and it is amplified when knowledge is low (Marceau et al., 2015; Westling et al., 2008). During early childhood, a secure infant-mother attachment can buffer girls from the later effects of harsh environments on earlier pubertal maturation (Sung et al., 2016).

The Context of Biological Sex and Gender Norms

The biological changes of puberty take place in social and cultural contexts, and these dynamic person-context interactions have implications for adolescent development. For instance, the physical changes associated with pubertal maturation affect an adolescent’s self-image as much as the way he or she is treated and responded to by others (Graber et al., 2010), and culturally grounded gender norms may make these associations more salient for girls than boys. Indeed, in the United States, although menstruation is acknowledged as a normal biological event, it is nevertheless often accompanied by feelings of shame and the need to conceal it from others, particularly males (Stubbs, 2008). As a result, the arrival of a girl’s first menstrual cycle is often accompanied by embarrassment and ambivalence (Brooks-Gunn et al., 1994; Moore, 1995; Tang et al., 2003), as well as by negative feelings (Rembeck et al., 2006), including anxiety, surprise, dismay, panic, and confusion (Brooks-Gunn and Ruble, 1982; Ruble and Brooks-Gunn, 1982).

The arrival of puberty has other social consequences, such as changing dynamics and maturing relationships with parents, siblings, and peers, as well as the emergence of peer relationships with adults. Pubertal maturation is associated with a higher incidence of sexual harassment, both by peers of the same gender and across genders (McMasters et al., 2002; Petersen and Hyde, 2009; Stattin and Magnusson, 1990). Social consequences may be exacerbated among youth experiencing early pubertal timing.

The increase in pubertal hormones (e.g., estradiol, progesterone, testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone) and the changes they drive, such as the emergence of secondary sex characteristics, is also associated with the development of substance use (Auchus and Rainey, 2004; Grumbach, 2002; Grumbach and Styne, 2003; Havelock et al., 2004; Matchock et al., 2007; Oberfield et al., 1990; Terasawa and Fernandez, 2001; Young and Altemus, 2004). At the same time, the causal direction of these findings is somewhat

mixed (Castellanos-Ryan et al., 2013; Dawes et al., 1999; Marceau et al., 2015), with variation by sex. In girls, relatively early pubertal timing and faster pubertal tempo often mark an increased risk for adolescent substance use (Cance et al., 2013; Castellanos-Ryan et al., 2013; Costello et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2014). By contrast, in boys later pubertal timing and/or slower pubertal tempo mark an increased risk for substance use (Davis et al., 2015; Marceau et al., 2015; Mendle and Ferrero, 2012). This striking gender difference in associations between pubertal maturation and substance use highlights how the same biological event (pubertal maturation) can lead to very different outcomes as a function of one’s biological sex.

Puberty and Stress Sensitivity

Puberty-related hormones influence the way adolescents adjust to their environment, for example by experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety. One mechanism through which this might occur is in pubertal hormones’ ability to alter sensitivity to stress, making adolescent girls particularly sensitive to exogenous stressors. Recent studies using salivary cortisol as an index of stress regulation have documented heightened stress reactivity and delayed post-stress recovery in pubescent adolescents (Gunnar, et al., 2009; Stroud et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2004). Cortisol is a steroid hormone released by the HPA axis, and disruption to this axis has been implicated in the development of symptoms of depression and anxiety (e.g., Gold and Chrousos, 2002; Guerry and Hastings, 2011; Sapolsky, 2000).

In fact, cortisol secretion is closely intertwined with age, puberty, and sex, which together appear to contribute to adolescent girls’ vulnerability to external stressors (Walker et al., 2004; Young and Altemus, 2004). As will be discussed in Chapter 3, cortisol, along with neuroendocrine, autonomic, immune, and metabolic mediators, usually promotes positive adaptation in the body and the brain, such as efficient operation of the stress response system. However, when cortisol is over- or under-produced it can, along with the other mediators, produce negative effects on the body and brain, such as forming insulin resistance and remodeling the brain circuits that alter mood and behavior. At the same time, as will be shown in Chapter 3, interventions during adolescence have the potential to mediate the harmful effects of stress.

Summary

In summary, puberty is shaped by both biological and social processes. Biologically, puberty occurs over an extended period during which neuroendocrine alterations result in the maturation of primary and secondary sex characteristics and the acquisition of reproductive maturity. The timing and tempo of pubertal development varies greatly, and the age at which an ado-

lescent matures depends upon a combination of genetic and environmental influences, including early life experiences. Socially, pubertal maturation and its accompanying physical changes affect how adolescents perceive themselves and how they are treated by others, and early pubertal timing especially has been shown to have social consequences. While we know a great deal about the biological processes of puberty, much of the research, particularly on the role of adverse early experiences, is based on studies of girls rather than boys and excludes transgender and gender-nonconforming youth. Thus, it is important to monitor whether or not conclusions drawn from the extant research are relevant for both girls and boys, and to consider how further study of puberty in boys, transgender youth, and gender-nonconforming youth may deepen our understanding of these dynamic processes.

Despite this limitation, research on associations between stress exposure and pubertal timing and tempo makes clear the importance of early experiences and highlights the role of social determinants of health. Stressful living conditions are related to earlier pubertal timing and accelerated pubertal tempo. While early puberty may be an evolutionarily adaptive response to context that reflects neurobiological plasticity, there are important consequences that suggest it may not be adaptive in terms of supporting a long-term path to health and well-being for youth living in the 21st century. Structural changes that disrupt the systemic factors that increase risk for early puberty (e.g., resource deprivation) as well as supportive relationships can mitigate the risks associated with early puberty, can foster positive outcomes, and may promote adolescents’ capability for resilience.

NEUROBIOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT

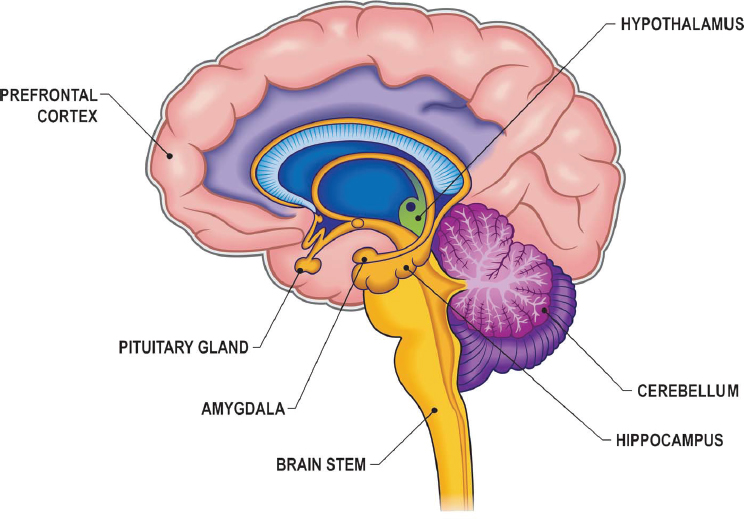

Adolescence is a particularly dynamic period of brain development, second only to infancy in the extent and significance of the neural changes that occur. The nature of these changes—in brain structures, functions, and connectivity—allows for a remarkable amount of developmental plasticity unique to this period of life, making adolescents amenable to change.4 These normative developments are required to prepare the brain so it can respond to the demands and challenges of adolescence and adulthood, but they may also increase vulnerability for risk behavior and psychopathology (Paus et al., 2008; Rudolph et al., 2017). To understand how to take advantage of this versatile adolescent period, it is first important to recognize how and where the dynamic changes in the brain are taking place; Figure 2-2 shows structures and regions of the brain that have been the focus of adolescent developmental neuroscience.

___________________

4 See Chapter 3 for a discussion of the adaptive plasticity of adolescence and the potential of interventions during adolescence to mediate deficiencies from earlier life periods.

SOURCE: iStock.com/James Kopp.

In the following sections, we summarize current research on structural and functional brain changes taking place over the course of adolescence. Our summary begins with a focus on morphological changes in gray and white matter, followed by a discussion of structural changes in regions of the brain that have particular relevance for adolescent cognitive and social functioning. We then discuss current theoretical perspectives that attempt to account for the associations between neurobiological, psychological, and behavioral development in adolescence.

Notably, the field of adolescent neuroscience has grown quickly over the past several decades. Advances in technology continue to provide new insights into neurobiological development; however, there is still a lack of agreed-upon best practices, and different approaches (e.g., in equipment, in statistical modeling) can result in different findings (Vijayakumar et al., 2018). Our summary relies on the most recent evidence available and, per the committee’s charge, we focus on neurobiological changes that make adolescence a period of unique opportunity for positive development. This is not intended to be an exhaustive review of the literature; moreover, studies tend to use “typically” developing adolescents, which limits our ability to comment on whether or how these processes may change for young people with developmental delays or across a broader spectrum of neurodiversity.

High Plasticity Marks the Window of Opportunity

Studies of adolescent brain development have traditionally focused on two important processes: changes in gray matter and changes in myelin. Gray matter is comprised of neural cell bodies (i.e., the location of each nerve cell’s nucleus), dendrites, and all the synapses, which are the connections between neurons. Thus, increases or decreases in gray matter reflect changes in these elements, representing, for instance, the formation or disappearance of synapsis (also known as “synaptogenesis” and “synaptic pruning”). New learning and memories are stored in dynamic synaptic networks that depend equally on synapse elimination and synapse formation. That is, unused connections and cells must be pruned away as the brain matures, specializes, and tailors itself to its environment (Ismail et al., 2017).

White matter, on the other hand, is comprised of myelin. Myelin is the fatty sheath around the long projections, or axons, that neurons use to communicate with other neurons. The fatty myelin insulates the axonal “wire” so that the signal that travels down it can travel up to 100 times faster than it can on unmyelinated axons (Giedd, 2015). With myelination, neurons are also able to recover quickly from firing each signal and are thereby able to increase the frequency of information transmission (Giedd, 2015). Not only that, myelinated neurons can more efficiently integrate information from other input neurons and better coordinate their signaling, firing an outgoing signal only when information from all other incoming neurons is timed correctly (Giedd, 2015). Thus, the increase in white matter is representative of the increase in quality and speed of neuron-to-neuron communication throughout adolescence. This is comparable to upgrading from driving alone on a single-lane dirt road to driving on an eight-lane paved expressway within an organized transportation/transit authority system, since it increases not only the amount of information trafficked throughout the brain but also the brain’s computational power by creating more efficient connections.

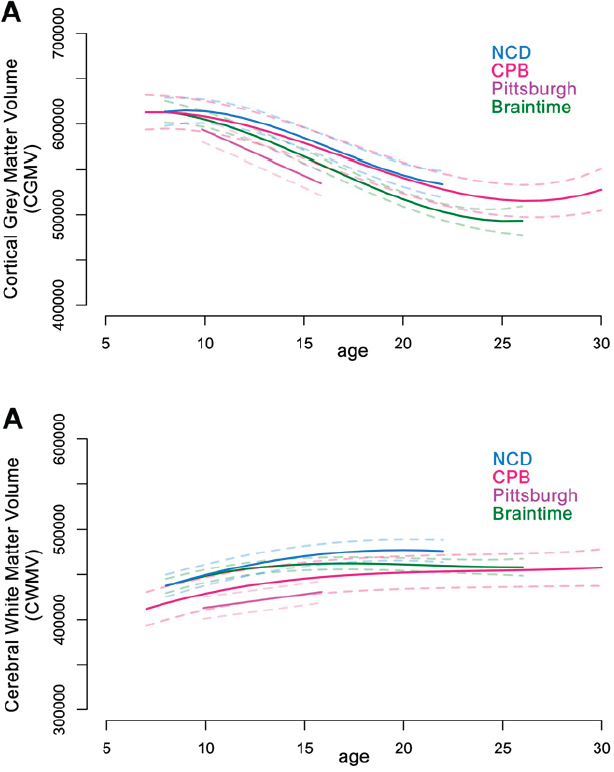

Recent advances in neuroimaging methods have greatly enhanced our understanding of adolescent brain development over the past three decades. In the mid-2000s developmental neuroscientists described differential changes in gray matter (i.e., neurons) and white matter (i.e., myelin) over the course of adolescence. Specifically, gray-matter volume was believed to follow an inverted-U shape, peaking in different regions at different ages and declining over the course of late adolescence and adulthood (Lenroot and Giedd, 2006). In contrast, cortical white matter, which reflects myelin growth, was shown to increase steadily throughout adolescence and into early adulthood, reflecting increased connectivity among brain regions (Lenroot and Giedd, 2006). The proliferation of neuroimaging studies, particularly longitudinal studies following children over the course of ado-

lescence, has enabled researchers to examine these processes in more detail and across a larger number of participants (Vijayakumar et al., 2018).

Analyses of about 850 brain scans from four samples of participants ranging in age from 7 to 29 years (average = 15.2 years) confirm some previous trends, disconfirm others, and highlight the complexity in patterns of change over time. Researchers found that gray-matter volume was highest in childhood, decreased across early and middle adolescence, and began to stabilize in the early twenties; this pattern held even after accounting for intracranial and whole brain volume (Mills et al., 2016). Additional studies of cortical volume have also documented the highest levels occurring in childhood with decreases from late childhood throughout adolescence; the decrease appears to be due to the thinning of the cortex (Tamnes et al., 2017). Importantly, this finding contrasts with the “inverted-U shape” description of changes in gray-matter volume and disconfirms previous findings of a peak during the onset of puberty (Mills et al., 2016).

For white-matter volume, on the other hand, researchers found that across samples, increases in white-matter volume occurred from childhood through mid-adolescence and showed some stabilizing in late adolescence (Mills et al., 2016). This finding generally confirms patterns observed in other recent studies, with the exception that some researchers have found continued increases in white-matter volume into early adulthood (versus stabilizing in late adolescence; e.g., Aubert-Broche et al., 2013). Figure 2-3 shows these recent findings related to gray and white matter.

The widely held belief about a peak in cortical gray matter around puberty followed by declines throughout adolescence was based on the best available evidence at the time. New studies show steady declines in cortical volume beginning in late childhood and continuing through middle adolescence. While the decrease in volume is largely due to cortical thinning rather than changes in surface area, there appear to be complex, regionally specific associations between cortical thickness and surface area that change over the course of adolescence (Tamnes et al., 2017). Discrepant findings can be attributed to a number of factors including head motion during brain imaging procedures (more common among younger participants), different brain imaging equipment, and different approaches to statistical modeling (Tamnes et al., 2017; Vijayakumar et al., 2018). There do appear to be converging findings regarding overall directions of change; however, inconsistencies in descriptions of trajectories, peaks, and regional changes will likely continue to emerge as researchers work toward agreed-upon best practices (Vijayakumar et al., 2018). Importantly, though, as Mills and colleagues (2016, p. 279) point out, it is critical to acknowledge that “it is not possible to directly relate developmental changes in morphometric MRI measures to changes in cellular or synaptic anatomy” (also see Mills and Tamnes, 2014). In other words, patterns of change in overall gray- or

NOTES: Age in years is measured along the x-axis and brain measure along the y-axis (raw values (mm3). Best fitting models are represented by the solid lines. Dashed lines represent 95-percent confidence intervals. Four longitudinal datasets from: CPB = NIH Child Psychiatry Branch (National Institute of Mental Health); NCD = Neurocognitive Development (University of Oslo); Pittsburgh = University of Pittsburgh; and Braintime = Leiden University.

SOURCE: Mills et al. (2016, pp. 277–278).

white-matter volume do not provide insight into the specific ways in which neural connections (e.g., synapses, neural networks) may change within the adolescent brain.

In fact, some neural circuity, consisting of networks of synaptic connections, is extremely malleable during adolescence, as connections form and

reform in response to a variety of novel experiences and stressors (Ismail et al., 2017; Selemon, 2013). Gray-matter reduction in the cortex is associated with white-matter organization, indicating that cortical thinning seen in adulthood may be a result of both increased connectivity of necessary circuitry and pruning of unnecessary synapses (Vandekar et al., 2015). Thus, adolescent brains can modulate the strength and quality of neuronal connections rapidly to allow for flexibility in reasoning and for leaps in cognition (Giedd, 2015).

Structural Changes in the Adolescent Brain

Two key neurodevelopmental processes are most reliably observed during adolescence. First, there is evidence of significant change and maturation in regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) involved in executive functioning and cognitive and impulse control capabilities (Crone and Steinbeis, 2017; Steinberg, 2005). In other words, areas of the brain that support planning and decision-making develop significantly during the second decade of life. Second, there is evidence of improved connectivity5 within and between the cortical (i.e., outer) and subcortical (i.e., inner) regions of the brain. Moreover, in both the cortical and subcortical regions, there are age-related and hormone-related changes in neural activity and structure, such as increased volume and connectivity (Gogtay et al., 2004; Østby et al., 2009; Peper and Dahl, 2013; Wierenga et al., 2014).

Over the course of adolescence, regions of the PFC undergo protracted development and significant remodeling. Cortical circuits, especially those that inhibit behavior, continue to develop, enhancing adolescents’ capacity for self-regulation (Caballero and Tseng, 2016). Compared to adults, adolescents have a significantly less mature cortical system and tend to utilize these regions less efficiently, and this impacts their top-down cognitive abilities including planning, working memory, impulsivity control, and decision-making (Casey and Caudle, 2013). Ongoing development of structures and connections within the cortical regions corresponds to more efficient balancing of inputs and outputs as adolescents interact with the world.

Changes within subcortical brain regions are also reflected in adolescent capabilities. For instance, increased volume in certain subregions of the hippocampus may predict greater capacity for memory recall and retention in adolescents (Tamnes et al., 2014). Adolescents also display heightened activity in the hippocampus, compared with adults, and differential reward processing in the striatum, which is part of the basal ganglia and plays an important role in motivation and perception of reward. This neural activ-

___________________

5 “Connectivity” refers to the formation of synapses, or connections between neurons; groups of interconnected neurons form circuit-like neural networks.

ity may explain their increased sensitivity to rewards and contribute to their greater capacity for learning and habit formation, particularly when incentivized by positive outcomes (Davidow et al., 2016; Sturman and Moghaddam, 2012).

Another subcortical structure, the amygdala, undergoes significant development during puberty and gains new connections to other parts of the brain, such as the striatum and hippocampus (Scherf et al., 2013). The amygdala modulates and integrates emotional responses based on their relevance and impact in context. In conjunction with the amygdala’s substantial development, adolescents show higher amygdala activity in response to threat cues6 than do children or adults (Fuhrmann et al., 2015; Hare et al., 2008; Pattwell et al., 2012). Consequently, they are prone to impulsive action in response to potential threats7 (Dreyfuss et al., 2014). Changes in the hippocampus and amygdala may be responsible for suppressing fear responses in certain contexts (Pattwell et al., 2011). Such fearlessness can be adaptive for adolescents as they explore new environments and make important transitions—such as entering college or starting a new job away from home. Children and adults do not tend to show the same kind of fear suppression as adolescents, suggesting that this is unique to this stage of development (Pattwell et al., 2011).

A Neurodevelopmental Perspective on Risk-Taking

In recent years, researchers have worked to reconcile contemporary neuroscience findings with decades of behavioral research on adolescents. There has been a particular emphasis on understanding “risky” behavior through the lens of developmental neuroscience. Risk-taking can be driven by a tendency for sensation-seeking, in which individuals exhibit an increased attraction toward novel and intense sensations and experiences despite their possible risks (Steinberg, 2008; Zuckerman and Kuhlman, 2000). This characteristic is heightened during adolescence and is strongly associated with reward sensitivity and drive (Cservenka et al., 2013) as well as the rise in dopamine pathways from the subcortical striatum to the PFC (Wahlstrom et al., 2010). Ironically, as executive function improves, risk-taking based on sensation-seeking also rises, likely due to these strengthened dopamine pathways from the striatum to the PFC regions (Murty et al., 2016; Wahlstrom et al., 2010). Despite these stronger sensation-seeking

___________________

6 The threat cues used in the research cited here were pictures of “fearful faces,” which serve as a social cue of impending danger.

7 Impulsive action in response to potential threat was assessed using a “go/no-go” task. Simply put, this is a task in which participants are presented with two types out of three facial emotions (“happy” or “calm” or “fearful”) that are randomly assigned as “go” (stimulate action = press a button) or “no-go” (inhibit action = do not press button).

tendencies, however, by mid-adolescence most youth are able to perform cognitive-control tasks at the same level as adults, signaling their capacity for executive self-control (Crone and Dahl, 2012).

Risk-taking can also be driven by impulsivity, which includes the tendency to act without thinking about consequences (impulsive action) or to choose small, immediate rewards over larger, delayed rewards (impulsive choice) (Romer et al., 2017). Impulsive action, which is based on insensitivity to risk, is a form of risk-taking that peaks during early adolescence and is inversely related to working memory ability (Romer et al., 2011). It may also be a consequence of asynchronous limbic-PFC maturation, which is described below. Notably, impulsive actions are seen most frequently in a subgroup of adolescents with pre-existing impairment in self-control and executive function (Bjork and Pardini, 2015). In contrast, impulsive choice behaviors, which are made under conditions of known risks and rewards, do not peak in adolescence. Instead, impulsive choice declines from childhood to adulthood, reflecting the trend of increasing, prefrontal-regulated executive functions throughout adolescence (van den Bos et al., 2015). Interestingly, when given the choice between two risky options with ambiguous reward guarantees, adolescents are more inclined to explore the riskier option than are adults (Levin and Hart, 2003), showing a greater tolerance for ambiguities in reward and stronger exploratory drive (Tymula et al., 2012).

Theoretical models have emerged to explain how neurobiological changes map onto normative “risk” behaviors in adolescence. While some argue that these models and accompanying metaphors may be overly simplistic (e.g., Pfeifer and Allen, 2012), the models are nevertheless utilized frequently to guide and interpret research (e.g., Steinberg et al., 2018). We briefly discuss two of them here: the “dual systems” model and the “imbalance” model.

The “dual systems” model (Shulman et al., 2016; Steinberg, 2008) represents “the product of a developmental asynchrony between an easily aroused reward system, which inclines adolescents toward sensation seeking, and still maturing self-regulatory regions, which limit the young person’s ability to resist these inclinations” (Steinberg et al., 2018). The “reward system” references subcortical structures, while the “self-regulatory regions” refer to areas like the PFC. Proponents of the dual-systems model point to recent findings on sensation seeking and self-regulation from a study of more than 5,000 young people spanning ages 10 to 30 across 11 countries. A similar pattern emerged across these settings. In 7 of 11 countries there was a peak in sensation seeking in mid-to-late adolescence (around age 19) followed by a decline. Additionally, there was a steady rise in self-regulation during adolescence; self-regulation peaked in the mid-20s in four countries and continued to rise in five others. The researchers note that there were more similarities than differences across countries and sug-

gest that the findings provide strong support for a dual-systems account of sensation seeking and self-regulation in adolescence.

A second model, the “imbalance” model, shifts the focus away from an orthogonal, dual systems account and instead emphasizes patterns of change in neural circuitry across adolescence. This fine-tuning of circuits is hypothesized to occur in a cascading fashion, beginning within subcortical regions (such as those within the limbic system), then strengthening across regions, and finally occurring within outer areas of the brain like the PFC (Casey et al., 2016). This model corresponds with observed behavioral and emotional regulation—over time, most adolescents become more goal-oriented and purposeful, and less impulsive (Casey, 2015). Proponents of the imbalance model argue that it emphasizes the “dynamic and hierarchical development of brain circuitry to explain changes in behavior throughout adolescence” (Casey et al., 2016, p. 129). Moreover, they note that research stemming from this model focuses less on studying specific regions of the brain and more on how information flows within and between neural circuits, as well as how this flow of information shifts over the course of development (e.g., “temporal changes in functional connectivity within and between brain circuits,” p. 129).

Rethinking the “Mismatch” Between the Emotional and Rational Brain Systems

Regardless of whether one of these two models more accurately represents connections between adolescent neurobiological development and behavior, both perspectives converge on the same point: fundamental areas of the brain undergo asynchronous development throughout adolescence. Moreover, adolescent behavior, especially concerning increased risk-taking and still-developing self-control, has been notably attributed to asynchronous development within and between subcortical and cortical regions of the brain. The former drives emotion, and the latter acts as the control center for long-term planning, consideration of outcomes, and level-headed regulation of behavior (Galván et al., 2006; Galván, 2010; Mueller et al., 2017; Steinbeis and Crone, 2016). Thus, if connections within the limbic system develop faster than those within and between the PFC region,8 the imbalance may favor a tendency toward heightened sensitivity to peer influence, impulsivity, risk-taking behaviors, and emotional volatility (Casey and Caudle, 2013; Giedd, 2015; Mills et al., 2014).

___________________

8 While there may be asynchronous development of circuits within specific regions of the brain during adolescence, this does not mean that these regions are “fixed” by the end of adolescence; instead, people retain the ability for neural plasticity and change throughout the life course (see Chapter 3).

Indeed, adolescents are more impulsive in response to positive incentives than children or adults, although they can suppress these impulses when large rewards are at stake. Adolescents are also more sensitive than children or adults to the presence of peers and to other environmental cues, and show a heightened limbic response to threats (Casey, 2015). As the cortical regions continue to develop and activity within and across brain regions becomes more synchronized, adolescents gain the capacity to make rational, goal-directed decisions across contexts and conditions.

The idea of asynchrony or “mismatch” between the pace of subcortical development and cortical development implies that these developmental capacities are nonoptimal. Yet, even though they are associated with impulsivity and risk-taking, we should not jump to the conclusion that the gap in maturation between the emotion and control centers of the brain is without developmental benefit. As Casey (2015, p. 310) notes, “At first glance, suggesting that a propensity toward motivational or emotional cues during adolescence is adaptive may seem untenable. However, a heightened activation into action by environmental cues and decreased apparent fear of novel environments during this time may facilitate evolutionarily appropriate exploratory behavior.” While an adolescent’s “heart over mind” mentality may compromise judgment and facilitate unhealthy behaviors, it can also spawn creativity and exploration. Novelty seeking can be a boon to adolescents, spurring them to pursue exciting, new directions in life (Spear, 2013).

If properly monitored and cushioned by parents and the community, adolescents can learn from missteps and take advantage of what can be viewed as developmental opportunities. Indeed, because adolescents are more sensitive to rewards and their decision-making ability may skew more toward seeking the positive benefits of a choice and less toward avoiding potential risks, this tendency can enhance learning and drive curiosity (Davidow et al., 2016). To avoid stereotyping all adolescents as “underdeveloped” or “imbalanced,” it is important to recognize the nuances in the different types of risk-taking behavior and to counterbalance a focus on negative outcomes by observing the connections between risk-taking and exploration, curiosity, and other attributes of healthy development (Romer et al., 2017).

The “mismatch” model provides one way of understanding adolescents’ capacity for self-control and involvement in risky behavior. A better model of adolescent neurobiological development, some argue, is a “lifespan wisdom model,” prioritizing the significance of experience on brain maturation that can only be gained through exploration (Romer et al., 2017). Indeed, growing evidence shows that adolescents have a distinctive ability for social and emotional processing that allows them to adapt readily to the capricious social contexts of adolescence, and equips them

with flexibility in adjusting their motivations and prioritizing new goals (Crone and Dahl, 2012; Nigg and Nagel, 2016).

Despite differences between neurobiological models, there is agreement that distinctions between adolescent and adult behaviors necessitate policies and opportunities intended to address adolescent-specific issues. With their heightened neurocognitive capacity for change, adolescents are in a place of both great opportunity and vulnerability. Key interventions during this period may be able to ameliorate the impact of negative experiences earlier in life, providing many adolescents with a pivotal second chance to achieve their full potential and lead meaningful, healthy, and successful lives (Guyer et al., 2016; see also Chapter 3).

Cognitive Correlates of Adolescent Brain Development

Reflective of the ongoing changes in the brain described above, most teens become more efficient at processing information, learning, and reasoning over the course of adolescence (Byrnes, 2003; Kuhn, 2006, 2009). The integration of brain regions also facilitates what is called “cognitive control,” the ability to think and plan rather than acting impulsively (Casey, 2015; Casey et al., 2016; Steinberg, 2014).

Changes in components of cognitive control, such as response selection/inhibition and goal selection/maintenance, along with closely associated constructs such as working memory, increase an individual’s capacity for self-regulation of affect and behavior (Ochsner and Gross, 2005). Importantly, each of these aspects of cognitive control appears to have distinct developmental trajectories, and each may be most prominently associated with distinct underlying regions of the cortex (Crone and Steinbeis, 2017). For example, although the greatest developmental improvements in response inhibition and interference control may be observed prior to adolescence, improvements in flexibility, error monitoring, and working memory are more likely to occur throughout the second decade of life (Crone and Steinbeis, 2017). This suggests different developmental trajectories, whereby more basic, stimulus-driven cognitive control processes develop earlier than do more complex cognitive control processes, which rely on internal and abstract representation (Crone and Steinbeis, 2017; Dumontheil et al., 2008).

Those functions that do continue to show significant developmental change during adolescence seem to especially rely on the capacity for abstract representation, which is a capacity that has been found to undergo a distinctive increase during adolescence (Dumontheil, 2014). The capacity for abstract representation can relate to both temporal and relational processes, that is, to both long-term goals and to past or future events (temporal) and to representing higher-order relationships between represen-

tations (relational) as distinct from simple stimulus features (Dumontheil, 2014). From early through late adolescence (into adulthood), this increase in abstract thinking ability makes teens better at using evidence to draw conclusions, although they still have a tendency to generalize based on personal experience—something even adults do. Adolescents also develop greater capacity for strategic problem-solving, deductive reasoning, and information processing, due in part to their ability to reason about ideas that may be abstract or untrue; however, these skills require scaffolding and opportunities for practice (Kuhn, 2009).

Recent research on cognitive development during adolescence has focused on both cognitive and emotional (or “affective”) processing, particularly to understand how these processes interact with and influence each other in the context of adolescent decision making. First, the capacity for abstract representation and for affective engagement with such representations (Davey et al., 2008) increases the capacity for self-regulation of emotions in order to achieve a goal (Ochsner and Gross, 2005). Indeed, the capacity to regulate a potent, stimulus-driven, short-term response may rely on the ability to mentally represent and affectively engage with a longer-term goal. Furthermore, such stimulus-driven, affective influences on cognitive processing, including on decision making, risk-taking, and judgment, change significantly over the course of adolescence (Hartley and Somerville, 2015; Steinberg, 2005).

Beyond individual capacities for cognitive regulation, the social and emotional context for cognitive processing matters a great deal. The presence of peers and the value of performing a task influence how motivating certain contexts may be and the extent to which cognitive processing is recruited (Johnson et al., 2009). Moreover, there is increasing evidence that some of these changes in cognitive and affective processing are linked to the onset of puberty (Crone and Dahl, 2012). Researchers have found that adolescents do better than young adults on learning and memory tasks when the reward systems of the brain are engaged (Davidow et al., 2016).

These changes in cognitive functioning may have adaptive qualities as part of normative adolescent development, even though they also make some individuals more vulnerable to psychopathology, such as depression and anxiety disorders. Notably, the flexibility of the frontal cortical network may be greater in adolescence than in adulthood (Jolles and Crone, 2012). Such flexibility may result in an improved ability to learn to navigate the increasingly complex social challenges that are part of adolescents’ social worlds, and as adolescents encounter increasing opportunities for autonomy it may prove to be adaptive. In addition, the ability to shift focus in a highly motivated way could allow more learning, problem solving, and use of creativity (Kleibeuker et al., 2016). Of particular relevance, such emerging abilities may also determine the degree to which an indi-

vidual can take advantage of new learning opportunities, including mental health–promoting interventions. With the right supports, this capacity for flexibility and adaptability can foster deep learning, complex problem-solving skills, and creativity (Crone and Dahl, 2012; Hauser et al., 2015; Kleibeuker et al., 2012).

Summary

The extensive neurobiological changes in adolescence enable us to reimagine this period as one of remarkable opportunity for growth. Connections within and between brain regions become stronger and more efficient, and unused connections are pruned away. Such developmental plasticity means adolescents’ brains are adaptive; they become more specialized in response to environmental demands. The timing and location of the dynamic changes are also important to understand. The onset of puberty, often between ages 10 and 12, brings about changes in the limbic system region resulting in increased sensitivity to both rewards and threats, to novelty, and to peers. In contrast, it takes longer for the cortical regions, implicated in cognitive control and self-regulation, to develop (Steinberg et al., 2018).

Adolescent brains are neither simply “advanced” child brains, nor are they “immature” adult brains—they are specially tailored to meet the needs of this stage of life (Giedd, 2015). Indeed, the temporal discrepancy in the specialization of and connections between cortical and subcortical brain regions makes adolescence unique. The developmental changes heighten sensitivity to reward, willingness to take risks, and the salience of social status, propensities that are necessary for exploring new environments and building nonfamilial relationships. Adolescents must explore and take risks to build the cognitive, social, and emotional skills they will need to be productive adults. Moreover, the unique and dynamic patterns of brain development in adolescence foster flexible problem-solving and learning (Crone and Dahl, 2012). Indeed, adolescence is a seminal period for social and motivational learning (Fuligni, 2018), and this flexibility confers opportunity for adaptability and innovation.

While developmental plasticity in adolescence bears many advantages, as with all aspects of development the environment matters a great deal. The malleable brains of adolescents are not only adaptable to innovation and learning but also vulnerable to toxic experiences, such as resource deprivation, harsh, coercive or antisocial relationships, and exposure to drugs or violence. All of these can “get under the skin” as adolescents develop, or more precisely interact with the brain and body to influence development (see Chapter 3).

What is more, the majority of mental illnesses—including psychotic and substance use disorders—begin by age 24 (Casey, 2015; Giedd, 2015).

This means that we have a collective responsibility to ask, “How can we create the kinds of settings and supports needed to optimize development during this period of life?” This goes well beyond simply keeping youth out of harm’s way, and instead signals an urgent need to consider how we design the systems with which adolescents engage most frequently to meet their developmental needs. Notably, scholars studying adolescent developmental neuroscience suggest the next generation of research should consider questions that shift from understanding risk to understanding thriving, and context-specific opportunities to promote it. Such questions for the field include, “How does brain development create unique opportunities for learning and problem solving?,” “Is the adolescent brain more sensitive to some features of the social environment than others?,” and “Are trajectories of change [in cognitive control and emotional processing] steeper or quicker during some periods than others, potentially providing key windows for input and intervention?” (Fuligni et al., 2018, p. 151).

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT IN ADOLESCENCE

As described above, young people develop increased cognitive abilities throughout adolescence. These cognitive abilities provide the capacity for other aspects of psychosocial development that occur during the period. This section describes the psychosocial developmental tasks—including developing identity and a capacity for self-direction—that adolescents complete during their transition to adulthood. Understanding one’s self, understanding one’s place in the world, and understanding one’s capacity to affect the world (i.e., agency) are all processes that begin to take shape during adolescence in tandem with the physiological, neurobiological, and cognitive changes discussed above.

The trajectory of social and emotional development in adolescence may perhaps be best characterized as a time of increasing complexity and integration. As is true of their neurobiological development during the period, adolescents’ capacity for understanding and engaging with self, others, and societal institutions requires both integration and deepening. It requires adolescents to integrate multiple perspectives and experiences across contexts, and also to deepen their ability to make sense of complex and abstract phenomena.

This section begins with a summary of developmental trends in adolescent self- and identity development at a broad level, followed by a brief discussion of how these trends reflect recent findings from developmental neuroscience. From there, we discuss group-specific social identities. While there are many critical dimensions of social identity (e.g., gender, social class, religion, immigration status, disability, and others), we use race and sexuality as exemplars given the recent, monumental shifts in racial/ethnic

demographics and in the social and political climate around sexual minority status in the United States. The focus on race and sexuality is not intended to minimize other dimensions of identity; indeed, identity development is a salient process for all adolescents regardless of social group memberships. Moreover, as we discuss below, developmental scientists are increasingly calling for research that examines the intersectional nature of identities, both at the individual level as well as in ways that reflect membership in multiple groups that have historically experienced marginalization (Santos and Toomey, 2018).

Identity

Finding an answer to the question, “Who am I?” is often viewed as a central task of adolescence. Decades ago, Erik Erikson (1968) argued that during adolescence, youth take on the challenge of developing a coherent, integrated, and stable sense of themselves, and that failing to do so may make the transition to adult roles and responsibilities more difficult. Erikson’s concept of identity development assumes opportunities for exploration and choice and may or may not generalize across global contexts (Arnett, 2015; Syed, 2017). However, it has utility in the United States, where societal structures and dominant values such as independence and individuality encourage identity exploration.

Closely related to the question, “Who am I?” is the question, “How do I see myself?” (Harter, 2012). McAdams (2013) describes the developmental trajectory of “self” using a set of sequential metaphors: the “social actor” in childhood (because children engage in action) grows to become a “motivated agent” in adolescence (because teens are more purposeful and agent-driven, guided by values, motives, and hopes), and finally an “autobiographical author” in emerging adulthood, a time when young people work on building a coherent self-narrative. Studies of youth across the span of adolescence show that, for many young people, the sense of self and identity become more integrated, coherent, and stable over time (Harter, 2012; Klimstra et al., 2010; Meeus et al., 2010). Importantly, theory suggests and empirical evidence supports the idea that having a more “achieved” identity and integrated sense of self relates to positive well-being in adulthood and even throughout the life course (e.g., Kroger and Marcia, 2011; Meca et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2011).

While there is great variability across youth, there are also some distinct developmental trends in the emergence of self and identity. In early adolescence, young teens’ self-definitions are increasingly differentiated relative to childhood. They see themselves in multiple ways across various social and relational contexts, for example one way when with their family and another way when with close friends in the classroom. Although a young

adolescent may carry a great number of “abstractions” about his or her self, these labels tend to be fragmented and sometimes even contradictory (Harter, 2012). For instance, a 13-year-old may view herself as shy and quiet in the classroom, as loud and bubbly with close friends, and as bossy and controlling with her younger siblings. Longitudinal studies suggest that some perceptions of self (e.g., academic self-concept) decline in early adolescence as youth transition to middle school; however, there is a great deal of individual variability, variability across domains (e.g., academic vs. behavioral self-concept), and variability by gender (higher athletic self-concept among males vs. females; Cole et al., 2001; Gentile et al., 2009).

In middle adolescence, teens may still hold onto multiple and disjointed abstractions of themselves; however, their growing cognitive abilities allow for more frequent comparisons among the inconsistencies, and heightened awareness of these contradictions can create some stress (Brummelman and Thomaes, 2017; Harter, 2012). In this period, youth may also be more aware that their conflicting self-characterizations tend to occur most often across different relationship contexts. As in early adolescence, discrepancies between real and ideal selves can create stress for some youth, but as teens develop deeper meta-cognitive and self-reflection skills, they are better able to manage the discrepancies. To continue with the same hypothetical teen introduced above at age 13, at age 16 she might view being shy and quiet in the classroom and loud and bubbly with friends as parts of a more holistic, less fragmented sense of self.

Older adolescents have greater abilities to make sense of their multiple abstractions about self. They can reconcile what seem like contradictory behaviors by understanding them in context (Harter, 2012). For instance, older teens are more likely to view their different patterns of behavior across settings as reflecting a positive trait like “flexibility,” or they may characterize themselves as “moody” if they vacillate between positive and negative emotions in different situations. While peers are still important in late adolescence, youth may rely on them less when making self-evaluations; they also have greater capacity for perspective-taking and attunement to others, especially in the context of supportive relationships.

Emerging adulthood provides additional opportunities for experimenting with vocational options, forming new friendships and romantic relationships, and exercising more independent decision-making (Arnett, 2015; Harter, 2012; Schwartz et al., 2005). Many young adults shift from “grand” visions of possible selves to visions that are narrower and directly related to immediate opportunities. New experiences across contexts—like attending college or transitioning into the workforce—can shape whether emerging adults develop an authentic and integrated sense of self.

With the normative development of heightened sensitivity to social information, some youth may rely heavily on peer feedback in self-evaluation;

however, parents still play an important role in supporting a positive sense of self, especially when they are attuned to youths’ needs and couple their high expectations with support (Harter, 2012). Indeed, secure and supportive relationships with parents can help early and middle adolescents develop a clear sense of self (Becht et al., 2017) and can buffer youth who are socially anxious against harsh self-criticism (Peter and Gazelle, 2017).

Identity and Self: A Neurobiological Perspective

Recent advances in developmental neuroscience appear to complement decades of behavioral research on youth. For instance, the integrated-circuitry model of adolescent brain development discussed in the previous section (Casey et al., 2016), along with other models emphasizing the growing integration within and between emotionally sensitive brain regions (e.g., the limbic system) and those involved in planning and decision making (e.g., the cortical regions), correspond with the observation that adolescents develop a more coherent sense of self over time and experience. Likewise, changes observed in social and affective regions of the brain during adolescence align with behavioral tendencies toward exploration and trying new things (Crone and Dahl, 2012; Flannery et al., 2018). Although the evidence base is still growing, recent studies document how self-evaluation and relational identity processes are linked with regions of the brain like the ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) (which plays a role in the inhibition of emotional responses, in decision making, and in self-control) and the rostral/perigenual anterior cingulate cortex (which plays a role in error and conflict detection processes). In particular, activity in these regions increases from childhood through adolescence in a manner consistent with changes in identity development (Pfeifer and Berkman, 2018).

Recent theoretical models of value-based decision making suggest specific ways in which identity development and neural development are linked in adolescence (Berkman et al., 2017; Pfeifer and Berkman, 2018). An important premise is that while adolescents may be more sensitive to social stimuli such as peer norms and to rewarding outcomes such as tangible gains, their sense of self is still a critical factor influencing their behavior. In other words, while social norms and tangible gains and costs represent some of the “value inputs,” their construal of self and identity are also factors in their decision making. Moreover, neural evidence, like the activation observed in the vmPFC during self- and relational identity tasks, suggests that identity and self-related processes may play a greater role in value-based decision making during adolescence than they do in childhood (Pfeifer and Berkman, 2018).

Social Identities in Adolescence

As many youth work toward building a cohesive, integrated answer to the question, “Who am I?,” the answer itself is shaped by membership across multiple social identity groups: race, ethnicity, nationality, sexuality, gender, religion, political affiliation, ability status, and more. Indeed, in the context of increasingly complex cognitive abilities and social demands, youth may be more likely to contest, negotiate, elaborate upon, and internalize the meaning of membership in racial/ethnic, gender, sexual, and other social identity groups (e.g., Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). From a developmental perspective, these tasks are paramount in a pluralistic, multiethnic and multicultural society like the United States, which, as discussed in Chapter 1, is more diverse now than in previous generations.

Ethnic-Racial Identity. Currently, our nation’s population of adolescents is continuing to increase in diversity, with no single racial or ethnic group in the majority. A burgeoning area of study over the past two decades concerns ethnic-racial identity (ERI), and research in this field has found that for most youth, particularly adolescents of color, ERI exploration, centrality, and group pride are positively related to psychosocial, academic, and even health outcomes (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). ERI is multidimensional—it includes youths’ beliefs about their group and how their race or ethnicity relate to their self-definition—both of which may change over time (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). For immigrant youth, developing their own ERI may involve an internal negotiation between their culture of origin and that of their new host country, and most immigrant youth show a great deal of flexibility in redefining their new identity (Fuligni and Tsai, 2015). Regardless of country of origin, making sense of one’s ERI is a normative developmental process that often begins in adolescence (Williams et al., 2012). Indeed, given that research has consistently found ERI to be associated with adaptive outcomes, dimensions of ERI can be understood as components of positive youth development (Williams et al., 2014).

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. One of the distinctive aspects of adolescence is the emergence and awareness of sexuality, and a related aspect is the emerging salience of gender roles and expression. Adolescence is also a time when identities or sense of self related to gender and sexuality are developed and solidified (Tolman, 2011), and this occurs in a period during which sexuality and gender norms are learned and regulated by peers (Galambos et al., 1990). In this developmental context, LGBTQ youth begin to understand their sexual and gender identities.

The growing societal acceptance and legal recognition of LGBTQ youth is implicated in the recent observed drop in the age at which most of these

young people “come out,” that is, disclose their same-sex sexual identities. Less than a generation ago, LGBTQ people in the United States typically came out as young adults in their 20s; today the average age at coming out appears to be around 14, according to several independent studies (Russell and Fish, 2017).

In the context of such changes and growing acceptance and support for LGBTQ youth developing their sexual identity, it might be expected that the longstanding health and behavior disparities between these adolescents and heterosexual and cis-gender adolescents would be lessening. Yet multiple recent studies challenge that conclusion. Things do not appear to be getting “better” for LGBTQ youth: rather than diminishing, health disparities across multiple domains appear to be stable if not widening (Russell and Fish, 2017). This pattern may be explained by several factors, including greater visibility and associated stigma and victimization for LGBTQ youth, just at the developmental period during which youth engage in more peer regulation and bullying in general, especially regarding sexuality and gender (Poteat and Russell, 2013). In fact, a meta-analysis of studies of homophobic bullying in schools showed higher levels of homophobic bullying in more recent studies (Toomey and Russell, 2016). These patterns point to the importance of policies and programs that help schools, communities, and families understand and support LGBTQ (and all) youth (see Chapter 7).

Identity Complexity. Beyond race, gender, or sexuality alone, having a strong connection to some dimension of social identity—which could also be cultural, religious, or national—appears to be important for psychological well-being in adolescence (Kiang et al., 2008). Recent research also suggests that young adolescents benefit from having a more complex, multifaceted identity that goes beyond stereotypical expectations of social-group norms, especially when it comes to inclusive beliefs (Knifsend and Juvonen, 2013). For instance, a youth who identifies as a Black, 13-year-old, transgender female who plays volleyball and loves gaming is apt to have more positive attitudes toward other racial/ethnic groups than she would if she viewed racial/ethnic identity and other social identities as necessarily convergent (such as the notion that “playing volleyball and being a gamer are activities restricted to youth from specific racial/ethnic groups”; Knifsend and Juvonen, 2014).

However, context is still important, and the association between identity complexity and inclusive beliefs in early adolescence tends to be stronger for youth who have a diverse group of friends (Knifsend and Juvonen, 2014). Among college-age students there is also variation by race and ethnicity. For instance, the positive association between having a complex social identity and holding more inclusive attitudes toward others

has been found most consistently among students who are members of the racial/ethnic majority; for members of racial/ethnic minority groups, convergence between racial/ethnic identity and other in-group identities is not related to attitudes toward other racial/ethnic groups (Brewer et al., 2013). Beyond outgroup attitudes, there is evidence that social identity complexity has implications for youths’ own perceptions of belonging; for instance, Muslim immigrant adolescents (ages 15 to 18) with greater identity complexity reported a stronger sense of identification with their host country (Verkuyten and Martinovic, 2012).

Social Identity and Neurobiology

Cultural neuroscience provides some insight into how social identity development may manifest at the neurobiological level, although there is still much work to be done to understand the deep associations between biology and culture (Mrazek et al., 2015). In adolescence, evidence suggests, areas of the brain attuned to social information may be undergoing shifts that heighten youths’ social sensitivity (Blakemore and Mills, 2014), and of course, adolescents’ “social brains” develop in a cultural context. For instance, we know the amygdala responds to stimuli with heightened emotional significance; in the United States, where negative stereotypes about Blacks contribute to implicit biases and fears about them, amygdala sensitivity to Black faces has been documented in adult samples (Cunningham et al., 2004; Lieberman et al., 2005; Phelps et al., 2000).

In a study of children and adolescents (ages 4 to 16) in the United States, Telzer and colleagues (2013) found that amygdala activation in response to racial stimuli, such as images of Black faces, was greater in adolescence than during childhood. They suggest that identity processes reflecting heightened sensitivity to race, along with biological changes (e.g., those stemming from puberty) related to a “social reorientation” of the amygdala, may be among the mechanisms that explain these race-sensitive patterns of activation in adolescence (Telzer et al., 2013). Importantly, neural activation appears to vary based on the context of social experiences. Specifically, the amygdala activation observed in response to Black faces was attenuated for youth who had more friends and schoolmates of a race differing from their own (i.e., cross-race friends).

The foregoing findings converge with psychobehavioral studies that demonstrate the importance of school and friendship diversity. Attending diverse middle schools and having more cross-race friends is associated with more positive attitudes toward outsider groups, less social vulnerability, greater social and academic competence, and better mental health (Graham, 2018; Williams and Hamm, 2017). Adolescence is a period of transformation in social cognition (Blakemore and Mills, 2014; Giedd, 2015), so in

light of the findings from psychobehavioral and cultural neuroscience research on the benefits of diversity, important questions may be asked about whether adolescence is a critical period for providing exposure to difference. For instance, should we expect the benefits of exposure to diversity to be maximized if such exposure occurs during adolescence, or are benefits most likely with cumulative exposure that begins well before this period?9

Identity Development in Context