1

Why Indicators of Educational Equity Are Needed

If the ladder of educational opportunity rises high at the door of some youth and scarcely rises at the doors of others, while at the same time formal education is made a prerequisite to occupational and social advancement, then education may become the means, not of eliminating race and class distinctions, but of deepening and solidifying them.

This quote is taken from the report of the Commission on Higher Education, which had been established by President Truman. Issued in 1947, the report is historically significant because it represents the first time that a U.S. president commissioned a panel to analyze the country’s system of education, a task typically left to the states, as laid out in the Constitution’s 10th Amendment. The report is also significant because of the messages it carried and the sweeping changes it called for. Its recommendations included:

. . . the doubling of college attendance by 1960; the integration of vocational and liberal education; the extension of free public education through the first 2 years of college for all youth who can profit from such education; the elimination of racial and religious discrimination; revision of the goals of graduate and professional school education to make them effective in training well-rounded persons as well as research specialists and technicians; and the expansion of Federal support for higher education through scholarships, fellowships, and general aid.

The report also called for:1

. . . the establishment of community colleges; the expansion of adult education programs; and the distribution of Federal aid to education in such a manner that the poorer States can bring their educational systems closer to the quality of the wealthier States.

These goals are striking because they could have been written yesterday. In the intervening 70 years, there have been other presidential commissions charged with analyzing and evaluating the state of education in the country (e.g., the National Commission on Excellence in Education in the 1980s and the President’s Commission on Excellence in Special Education in 2001). There have been many legislative and policy efforts aimed at removing barriers to opportunity for socially and economically disadvantaged groups and holding states and school systems accountable for the academic progress of all of their students (e.g., Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 1965 and the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001). A plethora of constitutional amendments, federal and state laws, and court decisions mark the nation’s history of attempts to address educational inequities: see Boxes 1-1, 1-2, and 1-3. Despite these efforts, however, the nation has not met many of the aspirations for education equity laid out more than 60 years ago.

Access to high-quality schooling is still uneven across student groups, and “race and class” distinctions (as in the quote above) remain. In recent years, rising income inequality has increased residential segregation, as families move to places where they can afford the cost of housing, which frequently leads to areas with high concentrations of poverty. Black and Latino children are more likely than white children to live in high-poverty areas.

- The rate of black children living in high-poverty areas in 2016 was about six times higher than that for white children (30% and 5%, respectively). The rate for Latino children (22%) was about four times that for white children (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2018).

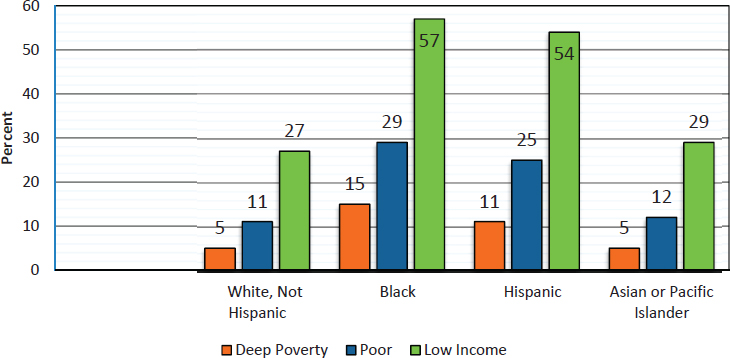

- The rate of children living in poverty in 2016 was about three times higher for black children (34%) than for white children (12%). The rate for Latino children (28%) was more than double that for white children: see Figure 1-1.

And as parental education affects family income, black children (12%) were twice as likely as white children (6%) to live in families in which the head of the household did not have a high school diploma. The rate for Latino

___________________

1 Cited by Pell Institute: see http://pellinstitute.org/indicators/.

NOTES: Deep Poverty: Under 50% of Federal Poverty Level (FPL); Poor: Under 100% of FPL; Low Income: Under 200% of FPL.

SOURCE: Data from Child Trends, 2019, see https://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=children-in-poverty.

children (32%) was more than five times that for white children (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2018).

Most school districts reflect the demographic and socioeconomic composition of their neighborhoods. School assignment policies that send all (or many) children from a high-poverty neighborhood to the same school create schools with high concentrations of children living in poverty. As we document in this report, schools serving children from low-income families tend to have fewer material resources (books, libraries, classrooms, etc.), fewer course offerings, and fewer experienced teachers. The educational opportunities available to students attending these schools are not of the same quality as those in schools in more affluent neighborhoods.

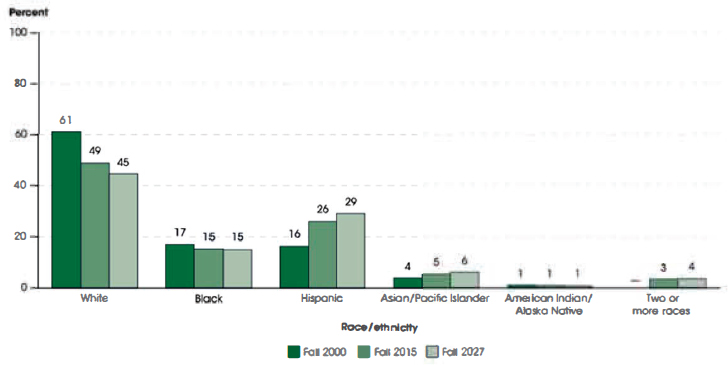

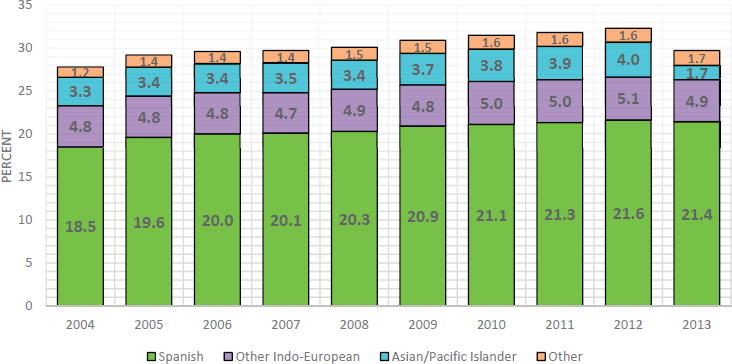

Education is sometimes characterized as the “great equalizer,” but to date, the country has not found ways to successfully address the adverse effects of socioeconomic circumstances, prejudice, and discrimination that suppress performance for some groups. The rapidly changing demographic characteristics of the population of school-age children mean new challenges for school systems. Figures 1-2 and 1-3 show some of the differences by race and ethnicity and home language.

NOTES: — Not available. Race categories exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity. Although rounded numbers are displayed, the figures are based on unrounded estimates. Detail may not sum to totals because of rounding.

SOURCE: Snyder, de Brey, and Dillow (2019, Table 203.50).

SOURCE: Data from Child Trends, 2016; see https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/dual-language-learners.

GOALS OF THIS REPORT

This report documents the work and recommendations of the 15-member Committee on Developing Indicators of Educational Equity. The committee’s charge is shown in Box 1-4.2 In accordance with this charge, the committee identified a set of key indicators that would measure the extent of disparities in the nation’s elementary and secondary education system. Their purpose would not be to track progress toward an aspirational goal measured in the aggregate per se, such as that all students graduate high school within 4 years of entering ninth grade, but to track and shed light on group differences in progress toward that goal, differences in students’ family background and other characteristics, and differences in the conditions and structures in the education system

___________________

2 The American Educational Research Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the Ford Foundation, the Spencer Foundation, the U.S. Department of Education, the William T. Grant Foundation, and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation provided support for this work.

that can exacerbate or mitigate the effects of those characteristics. Such a system of indicators could serve an important function to alert the public and policy makers to consequential disparities and suggest avenues for further investigation and policy formulation.

The committee recommends developing a system of key equity indicators that would be collected and reported on a regular, sustained basis. We call for the system to operate on a large scale with reporting mechanisms designed to regularly and systematically inform stakeholders at the national, state, and local level about the status of educational equity in the United States. The system we envision would rise to the same level of priority as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) with annual reports that allow the country to monitor progress in making education more equitable.

As most readers of this report know, the literature base on educational equity is immense. There are multitudes of studies that document disparities based on race, ethnicity, parental education, family income, native language, and other group definitions; numerous data collections that are available for use in these studies; and uncountable numbers of evaluations and recommendations. The present report is certainly not the first to suggest a set of indicators to monitor education equity.

Given the breadth and depth of information that is already available, why is another report needed? What does our report contribute to the field? In the five chapters that follow, we document what is known about inequities in education and the factors that contribute to them. Much of what we say is not new or ground-breaking. Many of the indicators we propose have long formed the bedrock of attempts to measure educational achievement and attainment of education credentials. However, the committee hopes that this report, anchored in the most recent research, will bring a new and heightened level of attention to educational equity. The indicators we suggest document consequential disparities that have the potential to help policy makers, parents, and others improve education policy or practice and support both formal and informal evaluations of effectiveness. To this end:

- We propose a manageable number of key indicators that cover the full range of pre-K to grade 12 education.

- Our recommendations reflect consensus among experts from diverse areas of expertise.

- Our recommendations acknowledge and emphasize that contextual factors, including segregation, are important for education.

- We recommend high-level structures that could be used to implement our proposed indicators.

COMMITTEE’S CONCEPTION OF EQUITY

In everyday conversation, the terms equity and equality are often used interchangeably. In technical contexts, their meanings differ in important ways. Equality generally connotes the idea that goods and services are distributed evenly, that is, everyone gets the same amounts, irrespective of individual needs or assets. The “starting point” is irrelevant—including the endowments—both positive and negative—that each individual brings to a situation. In contrast, equity incorporates the idea of need. The idea of need replaces a mechanistic approach to equality in which everyone receives the same amount of whatever is being distributed. Indeed, equity means that distribution of certain goods and services is purposefully unequal: for example, the most underserved students may receive more of certain resources, often to compensate or make up for their different starting points. For other terms that are important to the committee’s work, see Box 1-5.

The committee’s specific purpose is to develop indicators that document consequential disparities and thus offer insights to policy makers, policy implementers, state school boards, superintendents, educators, researchers, and others to help improve education policy and practice and also to support both formal and informal evaluations of effectiveness. For this pur-

pose, there is a need for indicators of disparities in key student outcomes related to educational achievement and attainment of credentials and of access to educational resources (e.g., effective teachers and high-quality curricula). Indicators also need to address disparities in access to opportunities to address structural disadvantages. Accordingly, the committee’s working definition of educational inequity is three-pronged. There is an inequity when:

- there is an excessive disparity between groups with respect to an educational outcome, such as high school graduation or access to a resource;

- there is an unacceptably poor fit between resources and student needs; or

- there is inadequate effort to mitigate the effects of deleterious segregation or some structural disadvantage faced by a group of learners, such as students from financially disadvantaged families, blacks, Latinos, or English learners.

A great many circumstances qualify as inequitable under this three-pronged definition. Moreover, stakeholders, including parents and students, may have different assessments of success in reducing inequities and, indeed, what is meant by an outcome such as a “high-quality education.” Furthermore, there is no scientific basis for specifying a particular value for “excessive” or “unacceptable” or “inadequate.” When a set of indicators is identified and becomes a factor in making decisions, people using the indicators—both policy makers and those affected by policy—will need to make their own judgments as to the importance of an observed disparity and what can be done to reduce it, considering other calls on political will and resources.

In this report, we do not specifically address how much inequity is too much or what action level may be appropriate for every actor in the complex, decentralized U.S. education system. However, in our recommendation of measures for inclusion in an education equity indicator system, we do try to focus on which education inequities matter most, based on the historical record of policy preferences revealed in legislation and court decisions and research findings on the consequences for student success in later life.

GUIDING CONCLUSIONS

The committee’s review of research on between-group differences in educational attainment (such as obtaining a diploma or other credential), the effects of these differences, and the legislation targeted at reducing these differences led us to draw three conclusions that guided our work.

CONCLUSION 1-1: Educational attainment, including, at a minimum, high school completion and a postsecondary credential, is a valued goal for all children in the United States. A high-quality education is in the best interests not only of the individual, but also of society. Failing to complete at least a high school education leaves individuals vulnerable to adverse consequences in adulthood, including a higher likelihood of unemployment, low-wage employment, poor health, and involvement with the criminal justice system. Those adverse adult outcomes for poorly educated individuals have significant costs for the nation as a whole.

CONCLUSION 1-2: Disparities in educational attainment among population groups have characterized the United States throughout its history. Students from families that are white, have relatively high incomes, and are English proficient have tended to have higher rates of educational attainment than other students, yet they now represent a decreasing proportion of the student population, while groups that have been historically disadvantaged represent an increasing proportion of the student population. An educational system that benefits certain groups over others misses out on the talent of the full population of students. It is a loss both for the students who are excluded and for society.

CONCLUSION 1-3: The history of constitutional amendments, U.S. Supreme Court decisions, and federal, state, and local legislation and policies indicates: (1) a recognition that population groups—such as racial and ethnic minorities, children living in low-income families, children who are not proficient in English, and children with disabilities—have experienced significant barriers to educational attainment; and (2) an expressed intent to remove barriers to education for all students. Educational equity requires that educational opportunity be calibrated to need, which may include additional and tailored resources and supports to create conditions of true educational opportunity.

COMMITTEE’S CONCEPTION OF AN INDICATOR SYSTEM

The value of an indicator system is that it brings attention to existing conditions, allows one to identify problems, provides a way to explore potential causes of those problems, and points toward actions to alleviate the problems. Equity indicators, if collected systematically and well, can allow valid comparisons of schools, districts, and states across a number of important student outcomes and resources. No one indicator by itself can tell the full story, but taken together, the set of indicators can provide a detailed and nuanced picture that speaks to policy makers and other

stakeholders about students’ educational status. Enacting change can be challenging, but it is nearly impossible if there is no information about existing problems.

What Is an Indicator?

An indicator is a measure used to track progress toward objectives or to monitor the health of an economic, environmental, social, or cultural condition over time. Different sorts of measures are used in different contexts. For example, unemployment rates, infant mortality rates, and air quality indexes are all indicators. In the field of education, school districts typically administer standardized reading assessments at specific grades to monitor how well students are meeting basic benchmarks in reading. Other commonly used education indicators include high school graduation rates, rates of truancy, ratios of teachers to students, and per-pupil expenditures, as well as measures of less quantifiable factors, such as teachers’ and students’ attitudes.

Indicators—literally, signals of the state of whatever is being measured—can cover outcomes, the presence or state of particular conditions, or the effectiveness of management approaches. They can be used to measure change over time or for comparisons among outcomes, conditions, or measures of effectiveness in different places. Although indicators are usually quantitative, they can either be straightforward measures of a single phenomenon, such as the number or percentage of students who graduate in a given year, or composite measures. A composite indicator is a measure of a more complex phenomenon, such as college readiness, and may incorporate a number of variables that capture aspects of what is being measured. Thus, an indicator is not the same thing as a statistic. As a primer on education indicators explained, statistics “need context, purpose, and meaning if they are going to be considered” indicators (Planty and Carlson, 2010, cited in National Research Council, 2012, p. 4).

Example from Economics: Monthly Jobs Report

Each month the American public receives a summary of the nation’s employment situation.3 Produced by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the summary provides key information for the current and prior month on unemployment and labor force participation, jobs, hours, and earnings. It provides unemployment rates for adult men, women, and teenagers, by race and ethnicity and by educational attainment, and job gains and losses for about two dozen sectors (e.g., manufacturing, health care).

___________________

3 See https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.toc.htm: text and Tables A and B.

These key indicators, which are eagerly awaited by the media, Congress, the executive branch, and the private sector, are only a few in a vast cornucopia of employment and unemployment data that provide more detail by worker and job characteristics and geographic areas. The summary’s role is to furnish a small set of high-quality, objective, and timely indicators of whether employment conditions are getting better or worse, overall and for key sectors. The summary often triggers further exploration of the detailed data that may, in turn, lead to policy actions, such as extending federal unemployment benefits to workers in high unemployment states.

A Possible Example from Education: Yearly Educational Equity Report

There are currently no indicators for monitoring the status of educational equity in the same way as the BLS summary does for the employment situation in the country. Yet educational equity is an equally important measure of the nation’s well-being. We draw from the labor statistics field to explain how a system of indicators would work in an educational equity context. The BLS provides a useful example because its indicators are succinct, familiar, and consistently reported. Understandably, of course, it is not an exact model of what is needed for educational equity. For educational equity, one needs to know about opportunity, and indicators need to be multidimensional, provide information about different grade levels, and meet the needs of thousands of school districts and schools.

A great many indicators and supporting data are regularly produced, not only by federal agencies, but also by state and local agencies and nongovernmental organizations. Examples include the longstanding NAEP, the congressionally mandated annual Condition of Education of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES),4 which is backed up by the extensive data in the annual Digest of Education Statistics,5 and the education section in the annual Kids Count Data Book: State Trends in Child Well-Being of the Annie E. Casey Foundation6 (see Appendix A). Indeed, the nation’s interest in education indicators predates its interest in labor force indicators: the predecessor to NCES was established in 1867, while the predecessor to BLS was established in 1884.

However, unlike the unemployment rate and some other federal economic indicators, none of the available education indicators is officially designated as a “key” indicator,7 and there is no corresponding regularly

___________________

4 See https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/.

5 See https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/.

6 See https://datacenter.kidscount.org/publications/.

7 See https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/assets/OMB/inforeg/statpolicy/dir_3_fr_09251985.pdf.

published, eagerly awaited, widely publicized report, with supporting data, analogous to the BLS Employment Situation Summary. Because education is a key predictor of economic success in life and is included as such in the BLS Employment Situation Summary, it would seem worthwhile to have key education indicators with similar stature. Similarly, just as the Employment Situation Summary includes indicators for population groups, defined by race, ethnicity, and gender, it would seem worthwhile to have key education indicators that address groups, given the disparities that have long plagued the U.S. education system.

An “Educational Equity Summary” could usefully highlight disparities between key populations groups, such as those defined by race and ethnicity, family income, and other dimensions of public and policy interest on two critical sets of indicators: (1) educational outcomes, such as participation, achievement, behaviors, and attainment; and (2) opportunities provided by the education system, such as access to effective teachers or to high-quality preschool programs. Such information would help target interventions, research, and policy initiatives to reduce disparities. Reports such as the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Race for Results8 and NCES’s Status and Trends in the Education of Racial/Ethnic Groups9 are helpful, but they are not regularly published and do not cover the range of indicators that are needed to track educational equity and inform policy.

COMMITTEE’S APPROACH TO ITS CHARGE

The committee conducted a broad review of evidence related to educational equity and educational equity indicators, including:

- the types of positive outcomes that are important for the education system to achieve (e.g., readiness for the next level of schooling, opportunities to learn, academic performance, and engagement in school) from pre-kindergarten through the transition to postsecondary education or other rewarding pursuits;

- school and nonschool inputs and conditions that influence those outcomes;

- the extent of disparities in outcomes and in relevant school inputs;

- interventions that have been shown to improve outcomes; and

- interventions for which, even if evidence is minimal, there is a strong theoretical basis as judged by recognized experts.

___________________

Two aspects of our review were an assessment of existing data systems of potential use for indicators of educational equity and an assessment of relevant publications: see Appendixes A and B, respectively. In addition, we reviewed the data and methodological opportunities and challenges for developing K–12 educational equity indicators: see Appendix C.

The committee held five in-person meetings and numerous teleconferences. The first two meetings included open session time to speak with stakeholders and other groups that are involved with collecting data and reporting education indicators. The committee also commissioned a set of authors to conduct literature reviews to help evaluate the empirical basis for potential indicators. A subset of these authors participated in the second meeting and suggested ways to structure the analyses of the research base and recommended other potential authors. The agendas for both meetings are in Appendix D.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

Five chapters follow this introduction. Chapter 2 discusses the purposes of a system of indicators of educational equity and explains our approach to identifying indicators. Chapter 3 discusses family, home, and neighborhood contextual factors as they relate to educational equity.

Chapters 4 and 5 present our suggestions for indicators. In Chapter 4, we discuss indicators of disparities in student outcomes, and in Chapter 5, we discuss indicators of disparities in access to important resources and opportunities

Chapter 6 presents the committee’s recommendations for implementation of an indicator system, addressed to the key audiences for this report. Some useful indicators are ready for prime time for the nation, states, school districts, and schools, while others are ready for some but not all levels of aggregation, and still others require additional research and development. Recommendations also address paths forward from the report to a useful and used system of educational equity indicators.

Appendixes A and B detail the committee’s assessments of existing data and indicators for potential use in our recommended system and of relevant publications. Appendix C discusses data and methodological issues. Appendix D contains the agendas for the committee’s two public meetings. Appendix E provides biographical sketches of the committee members and staff for this project.