5

Indicators of Disparities in Access to Educational Opportunities

As described in Chapter 4, we propose indicators that fall into two categories: indicators of disparities in students’ educational outcomes and indicators of disparities in students’ access to educational resources and opportunities. This chapter addresses the second category of indicators—those related to opportunities and resources. Table 5-1 shows the indicators we propose.

The five sections in this chapter cover each of the four domains related to opportunities, usually termed inputs or resources, and a fifth on the availability of data and measures for those four domains. In Appendix C the committee provides illustrations of the data sources and methods that could be used to develop appropriate measures for our proposed indicators.

DOMAIN D: EXTENT OF RACIAL, ETHNIC, AND ECONOMIC SEGREGATION

School segregation—both racial and economic—poses one of the most formidable barriers to educational equity. Under conditions of racial and economic segregation, black, Hispanic, and low-income students disproportionately attend schools with high concentrations of other black, Hispanic, and low-income students, while students from white and nonpoor families attend schools with other white children and children from families with more resources.

Segregation limits opportunities for children of all backgrounds to develop and enhance important life skills, such as the ability to interact effectively with diverse groups (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006). Attending

TABLE 5-1 Proposed Indicators of Disparities in Access to Educational Opportunities

| DOMAIN | INDICATORS | CONSTRUCTS TO MEASURE |

|---|---|---|

| D Extent of Racial, Ethnic, and Economic Segregation |

8 Disparities in Students’ Exposure to Racial, Ethnic, and Economic Segregation |

Concentration of poverty in schools Racial segregation within and across schools |

| E Equitable Access to High-Quality Early Learning Programs |

9 Disparities in Access to and Participation in High-Quality Pre-K Programs |

Availability of licensed pre-K programs Participation in licensed pre-K programs |

| F Equitable Access to High-Quality Curricula and Instruction |

10 Disparities in Access to Effective Teaching |

Teachers’ years of experience Teachers’ credentials, certification Racial and ethnic diversity of the teaching force |

| 11 Disparities in Access to and Enrollment in Rigorous Coursework |

Availability and enrollment in advanced, rigorous course work Availability and enrollment in Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate, and dual enrollment programs Availability and enrollment in gifted and talented programs |

|

| 12 Disparities in Curricular Breadth |

Availability and enrollment in coursework in the arts, social sciences, sciences, and technology |

|

| 13 Disparities in Access to High-Quality Academic Supports |

Access to and participation in formalized systems of tutoring or other types of academic supports, including special education services and services for English learners |

|

| DOMAIN | INDICATORS | CONSTRUCTS TO MEASURE |

|---|---|---|

| G Equitable Access to Supportive School and Classroom Environments |

14 Disparities in School Climate |

Perceptions of safety, academic support, academically focused culture, and teacher-student trust |

| 15 Disparities in Nonexclusionary Discipline Practices |

Out-of-school suspensions and expulsions |

|

| 16 Disparities in Nonacademic Supports for Student Success |

Supports for emotional, behavioral, mental, and physical health |

|

integrated and racially and culturally diverse schools can help to increase students’ comfort with diversity and understanding of different perspectives, which has been associated with improvements in critical thinking, communication, and problem solving (Kurlaender and Yun, 2005, 2007). Integrated schools have been shown to be better for all students. There is evidence that racially integrated schools are associated with greater life outcomes for all students, including higher college enrollment and success, higher lifetime earnings, a more diverse circle of friends and living arrangements in adulthood, and the important career skill of working with people from diverse backgrounds (Philips, Gormley, and Lowenstein, 2009; Siegel-Hawley, 2012; Wells, Fox, and Cordova-Cobo, 2016).1

Indicator 8: Disparities in Students’ Exposure to Racial, Ethnic, and Economic Segregation

Racial segregation—as measured by how evenly black and Hispanic students are distributed among U.S. public schools and public school districts—continues to be a problem, and recent data show that it has increased in recent decades. Measured by the proportion of schools clas-

___________________

1 For additional information, see https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-62-school-segregation-by-race-poverty-and-state/Brown-at-62-final-corrected-2.pdf; http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/system/files/School%20Segregation%20Full%20Report_0.pdf; https://www.epi.org/publication/the-racial-achievement-gap-segregated-schools-and-segregated-neighborhoods-a-constitutional-insult/.

sified as “high-minority” schools (75% or higher black and Hispanic), racial segregation increased from 9 percent in 2000–2001 to 16 percent in 2013–2014 (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2016). Some of the increase is due simply to the increasing proportion of black and Hispanic students in U.S. schools. That is, when measured by statistics describing how evenly students of different races are distributed among schools, given the current national racial composition, average school segregation levels have been relatively unchanged over the past few decades (see Reardon and Owens, 2014). The lack of progress in reducing these levels of racial segregation is due to several factors, especially the barriers to desegregation created by school district boundaries and by post-1973 changes in Supreme Court rulings. Those rulings limited the circumstances in which courts can impose desegregation orders, as well as the circumstances in which districts may voluntarily adopt race-sensitive policies to reduce segregation (Black, 2017; Yudof et al., 2011; Orfield et al., 2016).

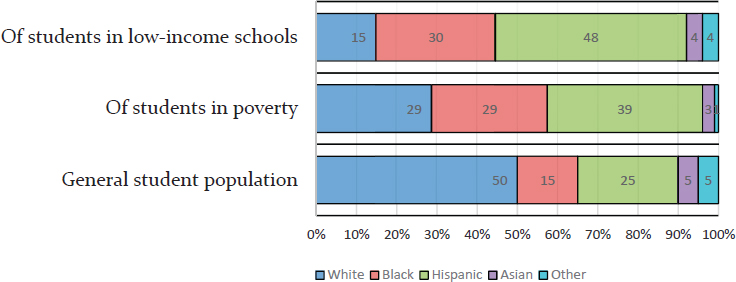

Economic segregation—as measured by how evenly poor and nonpoor students are distributed among U.S. public schools and public-school districts—has also risen steadily since the 1970s partly as a result of increasing income inequality and a rise in income-based housing segregation, especially among families with school-aged children. Sometimes referred to as “double segregation” (Orfield et al., 2016) or “hyper-segregation” (George and Darling-Hammond, 2019), these factors have led to circumstances in which black and Hispanic students are more likely than their white and Asians peers to be in schools with high levels of students from economically disadvantaged families. These patterns have been shaped by federal, state, and local schooling and housing policies, by racial and economic inequality, and by a history of housing discrimination (Orfield, 2013; Rothstein 2015). Black and Hispanic students are disproportionately likely to be low-income themselves, but they are even more disproportionately likely to be enrolled in schools with large proportions of low-income students (see Figure 5-1).

Research shows that schools that serve a majority of students from economically disadvantaged communities often lack the human, material, and curricular resources to meet their students’ academic and socioemotional needs. Consequently, their students have unequal access to the full suite of learning opportunities and resources that can promote their success and are available to children from wealthier families (Owens, Reardon, and Jencks, 2016). Indeed, school poverty rates are associated with key measures of school quality that affect learning and achievement (Bohrnstedt et al., 2015; Clotfelter et al., 2007; Hanushek and Rivkin, 2006). In one example elaborated elsewhere in this chapter, students in high schools serving high populations of students of color (defined as schools where at least 75 percent of students are black or Hispanic) or

SOURCE: Wagner (2017, p. 14). Reprinted with permission from School Segregation Then & Now: How to Move toward a More Perfect Union, Copyright 2017, National School Boards Association. All rights reserved.

high populations of students in poverty2 are less likely to have access to courses needed to prepare them for college and careers. Schools serving high concentrations of students in poverty offer fewer advanced placement (AP) courses and gifted and talented education programs (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2016).

There are many dimensions of segregation that might be included in an indicator of educational equity. Potential indicators might include measures of racial or economic segregation and measures of residential or school segregation. There are also several ways to measure segregation. Exposure is the extent to which students of a given race or ethnicity attend schools with students of another race or ethnicity, and isolation is the inverse of exposure. Unevenness is the extent that students are evenly distributed by race or ethnicity among schools within a district or other region. If all schools have the same racial and ethnic composition as one another (and therefore the same as that of the district or region), then there is evenness (Massey and Denton, 1988).

___________________

2 The definition is based on identifying low-income students as those eligible for free or reduced-price lunch under the National School Lunch Program, sorting K–12 schools according to the percentages of eligible students, separating out high schools, and dividing the high schools into quintiles, which we reference throughout the report (ExcelinEd, 2018).

Recent research has shown that the dimension of segregation most strongly associated with achievement is the racial difference in exposure to poor schoolmates (Reardon, 2016). That is, in places where black or Hispanic students attend schools with higher poverty rates than do white students, the white-black and white-Hispanic test score gaps are larger, on average. This measure—which captures the combination of racial and economic segregation—was more predictive of achievement gaps than measures of residential segregation, of racial segregation alone, or of economic segregation alone. These findings suggest that both economic segregation and racial segregation are harmful to academic achievement, and importantly, racial segregation is harmful because it leads to the economic segregation of white and nonwhite students.

Proposed Measures for Indicator 8

The committee proposes an indicator that is focused on the difference in poverty rates in schools attended by poor and nonpoor students, by students from different racial groups, by English-language learners, and by students with immigrant or foreign-born parents. Such an indicator is readily interpretable and has historically been relatively straightforward to measure so long as school districts report reliable school-level counts of students eligible for free or reduced-price meals.3 The committee also proposes an indicator of racial segregation within and across schools.

DOMAIN E: EQUITABLE ACCESS TO HIGH-QUALITY EARLY LEARNING PROGRAMS

Early childhood learning is a strong predictor of kindergarten readiness and “one of the most common and policy relevant out-of-home experiences” that young children can have (Magnuson, 2018, p. 8). However, there are sizable differences in the availability of licensed early learning programs and in enrollment: those differences are between children growing up in disadvantaged circumstances and their more advantaged peers. And that availability gap is compounded by a corresponding disparity in the quality of programs that are available to children from families with different income levels.4

___________________

3 We note, however, that some 20 percent of schools now provide free meals to all students, regardless of their family income, under the community eligibility provision of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. As a result of this provision, in many cases these schools no longer report accurate counts of students who are poor, complicating the measurement of differences in exposure to schoolmates who are poor. In order to provide accurate measures of segregation for this measure, it would be necessary to have accurate measures of school poverty that are comparable across schools, districts, and states (see Appendix C).

4 See https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_202.10.asp.

Indicator 9: Disparities in Access to and Participation in High-Quality Pre-K Programs

Participation in an early learning program is essential for ensuring that children develop the behaviors and competencies they will need to do well in kindergarten. Research suggests that participating in preschool programs for at least 2 years prior to entry to kindergarten is beneficial for all children (see Magnuson, 2018). Investments by federal, state, and local programs have increased considerably in the past 30 years in efforts to reduce enrollment gaps and improve access to high-quality early childhood education for disadvantaged populations. Nevertheless, children from lower income families, families with lower levels of educational attainment, and households in which the parents are not proficient in English—children who could benefit most from programs—are often the least likely to enroll in them (Table 5-2 shows these data). In particular, we note that:5

- 56.4 percent of Latino 3- to 5-year-olds were not enrolled, compared with 43.2 percent of white children.

- 50.5 percent of children with foreign-born parents were not enrolled, compared with 45.3 percent of children with native-born parents.

- 60 percent of children whose parents did not graduate high school were not enrolled, compared with 56.1 percent of children whose parents are high school graduates and 36.4 percent of children whose parents have a college degree.

While participation in any preschool program can be beneficial to children, participation in high-quality programs is even more important. At present, while measures of quality exist, they vary in terms of what is measured and how it is measured. Dimensions of quality include classroom resources; curriculum; interaction quality between teachers and children; and teachers’ credentials and experience.

Programs also vary in their complexity to implement, their feasibility, and their costs, as well as the validity of the rating systems. For instance, since all states have regulations and licensing standards for child care providers, one might think that simply being licensed could be the signal of program quality. However, state licensing regulations and standards vary widely, and not all of them address issues of quality as they relate to children’s development and learning. For example, many are focused on protecting children from harm, such as by mitigating risks from inadequate

___________________

5Child Trends (2015) has tabulated these percentages since 1994, and the pattern is similar across the years.

| Population Group | Extent of Participation in Preschool, Pre-K Program | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Day | Part Day | None | |

| Race and Ethnicity | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 25.2 | 31.6 | 43.2 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 38.6 | 17.6 | 43.7 |

| Hispanic | 22.0 | 21.6 | 56.4 |

| Parental Education | |||

| Less than a High School Degree | 20.3 | 19.7 | 60.0 |

| High School Degree or Equivalent | 24.6 | 19.4 | 56.1 |

| Some College or Technical or Vocational Degree | 23.4 | 26.6 | 50.0 |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 30.1 | 33.6 | 36.4 |

| Immigrant Status | |||

| Both Parents Native Born | 27.1 | 27.5 | 45.3 |

| One or Both Parents Foreign Born | 23.9 | 25.6 | 50.5 |

| Household Income | |||

| Less than $15,000 | 23.8 | 22.7 | 53.5 |

| $15,000-–$29,999 | 21.9 | 22.9 | 55.2 |

| $30,000–$49,999 | 24.2 | 23.2 | 52.6 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 24.0 | 27.9 | 48.1 |

| $75,000 and over | 21.7 | 32.4 | 35.9 |

NOTE: The data exclude children aged 3-5 who are enrolled in kindergarten or elementary school.

SOURCE: Information from Child Trends (2015).

supervision, poor building and hygiene standards, and unsafe practices (Workman and Ullrich, 2017). They may also specify education requirements for preschool teachers. Many stipulate fundamental components necessary for operation, but do not address the comprehensive developmental and learning needs of preschoolers.

Observational measures of classroom instructional quality are somewhat stronger predictors of children’s learning, although observations are

expensive and labor intensive, and existing research shows that the associations are small (Burchinal, Kainz, and Cai, 2011).

Although challenging to implement, quality rating and improvement systems are available and have been implemented in all states except Mississippi (see Box 5-1). More than half include an observational rating system designed to measure caregiver responsiveness and program stimulation (Tout et al., 2010).

The National Institute for Early Education Research publishes state report cards that rate early childhood programs on the basis of 10 criteria.6 The criteria are consistent across states and thus allow comparisons, but the information about program quality is limited.

These rating systems can be used at the state level to characterize the quality of a state’s early childhood education programs and possibly also reported at the school district level (or for other regions in a state). Because these rating systems differ from state to state, however, they cannot be used in a national indicator system without a major caveat: the data will only indicate provider quality in relation to what each state defines as adequate, not in relation to a national quality standard—because none exists in federal policy or in a consensus among researchers. However, even if a common measure of quality existed, it would not be useful for measuring disparities unless data on the demographics of the children enrolled at each center was known. Coordinated decision making would be necessary to select and refine a standard measure of program quality in a national indicator system, together with appropriate data collection systems.

Proposed Measures for Indicator 9

The committee proposes that Indicator 9 be measured in two ways: (1) the availability of licensed early childhood education programs and (2) enrollment in these programs. We would have liked to include access to high-quality programs as an indicator, but we cannot do so because of the inconsistencies and variability in measuring quality across states and other jurisdictions.

DOMAIN F: EQUITABLE ACCESS TO HIGH-QUALITY CURRICULA AND INSTRUCTION

Interaction between students and their teachers—through curriculum, coursework, and instruction—is at the heart of education. Students’ exposure to a rich and broad curriculum, challenging coursework, and inspired teaching is therefore vital for their learning and development. There is no

___________________

widespread agreement on which specific elements of curriculum, coursework, and teaching matter for student outcomes. Most of the research base is inadequate to support causal inferences about the relationships between these factors and student outcomes.

But there is evidence that these core elements are not distributed in an equitable way—in relation to either proportionality or need. Excellence in academic programming and resources needs to include not only equitable access to AP courses and other advanced coursework, but also meeting the academic needs of students on the other end of the achievement distribution. The adequacy of formal academic supports for students who are struggling to achieve is at least as important as fair access to enrichment opportunities for students at the top.

In the absence of research-based clear causal links of specific curricula, instructional practices, and courses with desired student outcomes, we are

proposing proxies based on the available research and the committee’s collective judgment.

Indicator 10: Disparities in Access to Effective Teaching

This committee is not the first to recognize the important role teachers play in promoting student learning. Indeed, there is widespread agreement that teachers are the most important in-school factor contributing to student outcomes (Aaronson, Barrow, and Sander, 2007; McCaffrey et al., 2004, 2009; Nye, Konstantopoulos, and Hedges, 2004; Rivkin, Hanushek, and Kain, 2005; Rockoff, 2004; Sanders and Rivers, 1996). These studies, which use value-added modeling (VAM) to estimate the effect of a teacher on students’ achievement test scores, have consistently found that the effects of individual teachers on their students’ achievement is substantial

and persistent. Although some scholars have identified limitations in these models (e.g., Rothstein, 2017), the large body of work on VAM has led to widespread support for claims about the importance of teachers. This is also a point of consensus among policy influencers (U.S. Department of Education, 2013).

While teacher effects on student learning have been extensively studied, recent work also finds that teachers have meaningful effects on engagement, behavioral skills, and other outcomes (e.g., Blazar and Kraft, 2017; Jackson, 2014; Ladd and Sorenson, 2017). This work also finds that teacher effects are multidimensional—those teachers who produce the best gains in student achievement do not necessarily produce the best gains in other outcomes (Blazar and Kraft, 2017; Jackson, 2014; Jennings and DiPrete, 2010; Kraft, 2019). Despite this knowledge, the field lacks useful measures of what makes teachers effective, especially with underserved student populations. For the measures that do exist, they are not available at scale for use in an indicator system.

The committee has chosen not to include other, commonly used measures of teaching effectiveness that focus specifically on teachers’ pedagogical skills or instructional practices. These strategies include observational measures, in which the supervisor or other expert rates teachers’ pedagogical quality according to key dimensions thought to characterize effective instruction, and student survey measures, in which students rate teachers’ instructional quality along similar key dimensions. There is a wealth of information about these measures, including guidance for developing, implementing, and using these kinds of measures (see, e.g., Cantrell and Kane, 2013; Gitomer and Zisk, 2015; Kane, Kerr, and Pianta, 2014). We wholeheartedly endorse use of these measures for local efforts to improve teaching, but we do not propose their use as indicators because they differ so much across jurisdictions and because they generally have not been validated for use in a large-scale indicator system.

We also have not included measures of teaching effectiveness as estimated through statistical modeling. These estimates can take a variety of forms, of which VAM is the most common. They are widely used as part of some states’ teacher evaluation systems, but this use is controversial. As the disagreements among researchers and stakeholders in the teacher evaluation field remain unresolved, the committee did not attempt to come to consensus about any of these issues.7 Any of these three measures could be used as an indicator in an educational equity system, but they could only provide information at the state or local level. We instead offer three other

___________________

7 Describing the disagreements about value-added methods is beyond the scope of this report. For reviews of this issue, see, for example, American Educational Research Association (2015); American Statistical Association (2014); and National Research Council (2010).

measures: teachers’ years of experience, teachers’ qualifications for the subjects they teach, and teacher diversity.

Teachers’ Years of Experience

Group differences in exposure to novice teachers are important to consider from an equity perspective. Overall, 5 percent of the nation’s 3 million teachers (full-time equivalent) are in their first year of teaching. However, schools serving the highest percentages of black and Latino students in their school district are more likely to employ teachers who are newest to the profession. These schools reported 6 percent of their teaching staff as being in their first year of teaching in any school, compared with 4 percent in schools with the lowest percentage (bottom 20%) of black and Latino students in their districts (Rahman et al., 2017). Of the nearly 5 million English learners nationwide, 3 percent attend schools where more than 20 percent of teachers are in their first year of teaching, compared with 2 percent of non-English learner students.

Teachers’ Qualifications for the Subjects They Teach

Teacher certification—itself a proxy for teachers having the relevant knowledge and skills to teach effectively—is not strongly associated with desired outcomes (Hanushek and Rivkin, 2010; Aaronson, Barrow, and Sander, 2007; Kane, Rockoff, and Staiger, 2008; Rockoff, 2004). However, direct measures of teachers’ knowledge seem predictive of student performance in some areas, especially math and science (e.g., Baumert et al., 2010; Hill, Rowan, and Ball, 2005; Sadler et al., 2013).

In these studies, teachers’ knowledge is typically measured by researcher-developed tests of teachers’ content knowledge or pedagogical content knowledge (e.g., Baumert et al., 2010; Hill, Rowan, and Ball, 2005; Sadler et al., 2013), though it is also possible to use existing assessments, such as college entrance exams or teacher certification exams, for this purpose. To date, however, the research on teacher knowledge has been limited to a small number of studies that do not address every grade and subject, and there is insufficient evidence regarding the appropriateness of existing knowledge tests for use in an indicator system.

In the absence of more refined measures, we propose including teacher certification in the system of equity indicators. Despite the lack of evidence that certification affects student achievement, it does provide a signal that teachers have attained a basic level of knowledge and skills, so students whose teachers lack certification might be at a disadvantage. Researchers have identified systematic between-group differences in access to certified teachers.

- Nationwide, 97 percent of teachers met all state certification or licensure requirements in the 2011-2012 school year. However, the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) reveals that nearly 0.5 million students are enrolled in schools in which 60 percent or fewer of the teachers met all state certification requirements (U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights, 2014).

- Racial disparities exist in students’ access to certified teachers: black students are more than four times as likely, and Latino students twice as likely, as their white peers to attend schools where 20 percent or more of their teachers have not yet met all state certification and licensing requirements. Nearly 7 percent of black students attend schools in which more than 20 percent of the teachers have not yet met all state certification and licensing requirements, compared with 3.7 percent of Latinos and slightly less than 2 percent of white students.

Teacher Diversity

The racial and ethnic distribution of students enrolled in public school has been gradually changing over the past few decades. As of 2015, a bare majority of public school students across the country were nonwhite; 49 percent were white.8 Specifically, public school students were 16 percent black, 26 percent Hispanic, 5 percent Asian, and 5 percent other or two or more races. By 2027, the population of students enrolled in public schools is projected to become even more diverse: 45 percent white, 15 percent black, 29 percent Hispanic, 6 percent Asian, 1 percent Native American, and 4 percent of two or more races.9

In contrast, there is far less diversity among teachers: in 2015, just 20 percent of teachers were nonwhite: 7 percent were black, 9 percent were Hispanic, 2 percent were Asian, and 2 percent were other or two or more races. In addition, nonwhite teachers are highly concentrated in certain areas: in 2011 an estimated 40 percent of schools had no nonwhite teachers, meaning nonwhite students in those schools might never experience a teacher of their own race or ethnicity (Bireda and Chait, 2011).

There is growing and compelling evidence that teacher-student racial match has important effects on student outcomes. These match effects appear on both short-term outcomes, such as student test scores and academic attitudes (Dee, 2004; Egalite and Kisida, 2018; Egalite, Kisida, and Winters, 2015; Goldhaber and Hansen, 2010), and long-term outcomes, such as dropping out of high school (Gershenson, Jacknowitz, and

___________________

8 See https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_203.50.asp?current=yes.

9 See https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_203.50.asp?current=yes.

Brannegan, 2017). They also are found on nonacademic outcomes, such as student disciplinary outcomes (Holt and Gershenson, 2017; Lindsay and Hart, 2017).

These effects are not small. For instance, in the Tennessee Student/Teacher Achievement Ratio (STAR) class-size study, the effects of student-teacher racial/ethnic match were as large as the effects of small classes themselves (Dee, 2004).10 In other words, students who were randomly assigned to a small class received an increase in achievement, and students (both black and white) who were randomly assigned to an own-race teacher received an equally large increase in achievement. Depending on model specification, those increases were not small in magnitude, ranging from 5 to 8 percentile points on a nationally normed achievement test. In terms of longer-term outcomes, black students randomly assigned a black teacher in the STAR study were 7 percent more likely to graduate from high school and 13 percent more likely to aspire to college than black students who were not randomly assigned a black teacher (Gershenson et al., 2018).

Given the persistent racial achievement gaps and demographic shifts in the United States, there is a new urgency to understand this phenomenon. Though more research is needed, the existing evidence suggests that the diversity of a school’s teaching staff and its match to the student body merits inclusion in a system of equity indicators.

Proposed Measures for Indicator 10

Measures for Indicator 10 should include teachers’ years of experience; teachers’ credentials for the subjects they teach; and diversity of the teaching force to which students are exposed.

Indicator 11: Disparities in Access to and Enrollment in Rigorous Coursework

Research has long shown that differences in exposure to challenging courses and instruction contribute to disparities in educational outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Gamoran, 1987; Gamoran and Mare, 1989; Oakes, 1985). These disparities can result from factors that differentially affect entire schools (between-school differences) or that differentially affect specific groups of students within a school (within-school differences). The former can arise from circumstances such as residential segregation (see Domain D, above) where access to opportunities and resources differs for schools with high and low concentrations of students in poverty. The latter can arise when students are assigned to coursework

___________________

10 For details, also see https://dataverse.harvard.edu.

using methods commonly known as “tracking,” such as assigning students to the college preparatory track or the general education track or using within-class ability groupings. While tracking may be well-intentioned as an instructional strategy, it can also mean that student groups are disproportionately placed in courses of differing levels of rigor, even if they have similar levels of ability or similar prior academic performance (Mickelson, 2005; Orfield and Lee, 2005).

In addition to organizational policies, various factors influence the within-school distribution of opportunities to students from different groups. Examples include teacher subjectivity (Dougherty et al., 2015; Grissom and Redding, 2016; Thompson, 2017); parents’ efforts on students’ behalf (Lewis and Diamond, 2015); and having a critical mass of prepared students (Iatarola, Conger, and Long, 2011). Counteracting some of these factors may require quite specific, tailored, school-level actions.

Inequitable access to rigorous coursework may be an especially serious issue for students with disabilities and English learners. Though federal law encourages the inclusion of students with disabilities in general education classrooms, they are often excluded from advanced or honors coursework.11 Even in general education classrooms, students with disabilities experience less time learning content in the grade-level standards, less instructional time, and less content coverage than their nondisabled peers (Kurz et al., 2014). Perhaps as a result, students with disabilities are much less likely than their nondisabled peers to expect to enroll in postsecondary education or take the necessary entrance exams (Lipscomb et al., 2017).

For English-language learners, the findings are similar: they have less opportunity to learn rigorous content in the classroom, often due to language barriers between them and their teachers (Abedi and Herman, 2010). They are also less likely than their English-language fluent peers to be exposed to the regular academic curricula in high school (Callahan and Shifrer, 2016; Umansky, 2016). Again perhaps because of these disparities, English learners are far less likely than native English speakers to subsequently attain college degrees (Kanno and Cromley, 2013).

Whether these disparities are caused by within-school or between-school factors, they can contribute to disparities in other desired outcomes. For example, differential access to prerequisite courses in middle school and in the early years of high school leaves many students ineligible or unprepared to take advanced courses. Some state university systems have course-taking requirements for entry that are more difficult to meet in schools that do not routinely offer all the necessary courses (Gao, 2016). In California, for example, inequities in course access and completion have resulted in large gaps in readiness for entrance to a college in either the

___________________

11 See https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-20071226.html.

California State University or the University of California system. In 2015, Asian students were about 15 percentage points more likely than white students to have taken the necessary high school coursework and about 30 percentage points more likely than black or Hispanic students (Gao, 2016). Similarly, selective colleges often use the difficulty of the students’ coursework as an important measure of student effort in making admissions decisions (Jaschik and Lederman, 2018): students who are placed in lower tracks are therefore at a disadvantage. And since many universities offer college credit for students who take and pass AP and similar exams, students who attend schools without those opportunities may be at a disadvantage.

Advanced course taking in high school is a strong indicator of opportunity to learn because it reflects both systematic differences in the availability of these courses and in who participates in them. As such, improving access to high-quality advanced coursework across several disciplines represents a potential lever for reducing group disparities in educational attainment.12

Tables 5-3 through 5-5 show the percentage of schools with high and low populations of black and Latino students (“high-minority” schools, “low-minority” schools)13 that do not offer higher level math and science courses and AP, International Baccalaureate (IB), and dual enrollment programs. Tables 5-6 through 5-8 show the same information for schools with high and low percentages of economically disadvantaged students (“high-poverty” schools, “low-poverty” schools). In most cases, high-minority schools are at least twice as likely to not offer these courses as are low-minority schools. Similarly, high-poverty schools are at least 1.5 times as likely as low-poverty schools to not offer advanced coursework in math and science and to not offer AP courses or dual enrollment programs.

Proposed Measures for Indicator 11

Indicator 11 should be measured by differential rates of enrollment and participation in gifted and talented programs, the coursework needed for college preparation, AP and IB courses, and dual enrollment programs.

___________________

12 See https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_049.asp.

13 We use the terms “high-minority schools” and “low-minority schools” as they are used by others; “minority” refers to black and Latino students.

| Subject | Quintile 1 Low Minority 20th percentile or lower in percent of minority students |

Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 High Minority 80th percentile or higher in percent of minority students |

All Schools | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Algebra 1 or higher | 12% | 764 | 13% | 689 | 17% | 939 | 21% | 1,246 | 25% | 1,371 | 20% |

| Geometry or higher | 13% | 853 | 15% | 790 | 20% | 1,097 | 26% | 1,502 | 29% | 1,591 | 23% |

| Algebra 2 or higher | 15% | 980 | 19% | 987 | 24% | 1,307 | 32% | 1,864 | 35% | 1,962 | 28% |

| Advanced Math or higher | 22% | 1,395 | 29% | 1,526 | 36% | 1,988 | 47% | 2,740 | 51% | 2,841 | 39% |

| Calculus | 40% | 2,542 | 46% | 2,446 | 52% | 2,893 | 62% | 3,625 | 70% | 3,887 | 55% |

SOURCE: ExcelinEd (2018, p. 16). Reprinted with permission from Foundation for Excellence in Education.

| Subject | Quintile 1 Low Minority 20th percentile or lower in percent of minority students |

Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 High Minority 80th percentile or higher in percent of minority students |

All Schools | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Biology or higher | 14% | 877 | 15% | 798 | 20% | 1,122 | 26% | 1,513 | 29% | 1,592 | 23% |

| Chemistry or higher | 18% | 1,163 | 23% | 1,233 | 30% | 1,662 | 39% | 2,310 | 42% | 2,312 | 33% |

| Physics | 31% | 1,990 | 37% | 1,977 | 44% | 2,443 | 53% | 3,111 | 59% | 3,265 | 47% |

SOURCE: ExcelinEd (2018, p. 17). Reprinted with permission from Foundation for Excellence in Education.

| Program | Quintile 1 Low Minority 20th percentile or lower in percent of minority students |

Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 High Minority 80th percentile or higher in percent of minority students |

All Schools | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Advanced Placement | 48% | 3,098 | 48% | 2,541 | 50% | 2,769 | 58% | 3,427 | 62% | 3,411 | 55% |

| International Baccalaureate | 99% | 6,313 | 97% | 5,154 | 96% | 5,303 | 95% | 5,594 | 97% | 5,380 | 97% |

| Dual Enrollment | 33% | 2,088 | 41% | 2,160 | 49% | 2,693 | 61% | 3,579 | 69% | 3,820 | 52% |

SOURCE: ExcelinEd (2018, p. 17). Reprinted with permission from Foundation for Excellence in Education.

| Subject | Quintile 1 Low Poverty 20th percentile or lower in percent of low-income students |

Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 High Poverty 80th percentile or higher in percent of low‐income students |

All Schools | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Algebra 1 or higher | 16% | 838 | 10% | 651 | 12% | 699 | 21% | 1,025 | 21% | 835 | 20% |

| Geometry or higher | 18% | 940 | 12% | 737 | 14% | 811 | 25% | 1,214 | 26% | 1,031 | 23% |

| Algebra 2 or higher | 21% | 1,105 | 14% | 897 | 18% | 1,006 | 31% | 1,523 | 32% | 1,281 | 28% |

| Advanced Math or higher | 29% | 1,528 | 21% | 1,348 | 29% | 1,631 | 46% | 2,274 | 50% | 1,975 | 39% |

| Calculus | 39% | 2,105 | 38% | 2,373 | 49% | 2,750 | 66% | 3,253 | 72% | 2,829 | 55% |

SOURCE: ExcelinEd (2018, p. 18). Reprinted with permission from Foundation for Excellence in Education.

| Subject | Quintile 1 Low Poverty 20th percentile or lower in percent of low-income students |

Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 High Poverty 80th percentile or higher in percent of low-income students |

All Schools | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Biology or higher | 18% | 978 | 12% | 776 | 15% | 835 | 25% | 1,216 | 25% | 991 | 23% |

| Chemistry or higher | 25% | 1,345 | 18% | 1,103 | 22% | 1,261 | 37% | 1,843 | 41% | 1,629 | 33% |

| Physics | 33% | 1,787 | 30% | 1,885 | 38% | 2,157 | 54% | 2,670 | 60% | 2,366 | 47% |

SOURCE: ExcelinEd (2018, p. 19). Reprinted with permission from Foundation for Excellence in Education.

| Program | Quintile 1 Low Poverty 20th percentile or lower in percent of low‐income students |

Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 High Poverty 80th percentile or higher in percent of low‐income students |

All Schools | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Advanced Placement | 41% | 2,172 | 42% | 2,667 | 50% | 2,822 | 62% | 3,042 | 65% | 2,574 | 55% |

| International Baccalaureate | 96% | 5,137 | 97% | 6,070 | 96% | 5,400 | 97% | 4,784 | 97% | 3,847 | 97% |

| Dual Enrollment | 44% | 2,335 | 34% | 2,160 | 40% | 2,266 | 58% | 2,858 | 65% | 2,562 | 52% |

SOURCE: ExcelinEd (2018, p. 19). Reprinted with permission from Foundation for Excellence in Education.

Indicator 12: Disparities in Curricular Breadth

A core mission of America’s schools is to produce “active, informed members of a democratic society” (Campbell, 2018, p. 1). A broad curriculum that includes courses in art, geography, history, civics, technology, music, science, world languages, and other subjects can contribute to this mission and help students become well-rounded individuals. While it is not known which specific combination of courses is best for students’ long-term outcomes, any educational system that differentially deprives students of exposure to a broad range of subjects is inequitable.

Every state has educational standards for a comprehensive range of subjects that, in theory, contributes to the broad education of all students and fulfills the mission of preparing them to participate in civic society. However, the emphasis that states place on those subjects and the resources they devote varies greatly. In addition, in the No Child Left Behind era, many subjects were eclipsed by an intense national focus on mathematics and reading (Dee, Jacob, and Schwartz, 2013; Ladd, 2017).

Decades of research have demonstrated that schools under the most pressure to improve test scores for purposes of accountability—which are almost always schools serving high proportions of black, Hispanic, and low-income students—often respond by narrowing the curriculum. In these schools and school systems, it is common:

- to focus on tested subjects and, within those subjects, on assignments that mimic standardized tests in terms of content and form (Au, 2007; Darling-Hammond and Wise, 1985; Firestone, Maryowetz, and Fairman, 1998; Madaus, 1988; Meherens, 1998; Newmann, Bryk, and Nagaoka, 2001);

- to restructure the school day to focus more intensively on core content areas (e.g., creating a block for literacy) (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2009); and

- to spend more time on general test-taking strategies (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2009).

Although the committee knows of no specific work linking these forms of curricular narrowing to later educational outcomes, this gap is in part due to the available data. For instance, it is not possible to know whether reducing instructional time on social studies has affected students’ civic knowledge because there is no comparable measure of civics knowledge to use as a dependent variable in such an analysis. Nevertheless, there is clear conceptual support for the idea that students’ access to a broad, diverse curriculum should not be determined by their personal characteristics or the characteristics of the schools they attend—thus, we believe curricular

breadth may be an important equity issue that merits further attention. However, we acknowledge that resource constraints will create tradeoffs when seeking to maximize overall equity. Curricular breadth in a high-needs school may be less important than, for example, academic supports for struggling students.

Proposed Measures for Indicator 12

Until measures of curricular breadth are developed and widely used, we encourage their consideration at the local level.

Indicator 13: Disparities in Access to High-Quality Academic Supports

Many students come to school needing resources or supports beyond those that are provided to most students. Some may need services to improve their English proficiency, and others may need special education services to address learning challenges. Still others may not need placement in a formalized program but could benefit from short-term tutoring or other individualized academic supports. The need for school-based academic supports is often greater when schools have a higher concentration of financially disadvantaged students, but the available resources may be less than adequate. School-based academic supports can include a variety of services, such as academic support classes, academic tutoring, early warning systems, and high school transition activities. Research suggests that academic support classes may have a positive effect on such student outcomes as average number of credits earned, high school graduation, and college enrollment.14 Data on disparities in the prevalence of these services are available through the U.S. Department of Education 2017 National Survey on High School Strategies Designed to Help At-Risk Students Graduate.15 The data are reported by school characteristic (e.g., high poverty, low poverty) and for groups of students likely to need extra help.

It is crucial that schools provide supports to address students’ academic, linguistic, and special education needs. There is a risk, however, that students might be identified for services that they do not need and that could result in reduced access to high-quality, appropriate instruction for those students.

Given the overrepresentation of some racial and ethnic groups in special education programs, educators have to be careful to ensure that students are not misidentified for those services. Inaccurate special education placement can be detrimental to students’ educational trajectories, locking stu-

___________________

14 See https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/high-school/academic-tutoring.pdf.

15 See https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/opepd/ppss/reports-high-school.html.

dents into a less demanding curriculum and potentially limiting exposure to challenging courses and instruction and to a diverse group of learners. The overrepresentation of black and Latino students in special education can also contribute to racially and ethnically segregated classrooms. Reports of this type of segregation have increased over time (see National Council on Disability, 2018)16 and have been the subject of lawsuits brought by the U.S. Department of Justice.17 Similarly, isolating English learners can limit their opportunities to participate in rigorous and challenging instructional programs and is likely to reduce opportunities for interactions between these students and their English-proficient peers. Concerns about linguistic isolation have increased over time and also been the subject of lawsuits.18

Proposed Measures for Indicator 13

The committee’s proposed indicator focuses on access to and participation in formalized systems of tutoring or other types of academic supports. Equity requires that all students have opportunities to participate in these kinds of programs if they demonstrate a clear need for them. At the same time, given the concerns about excessive identification of some students for special services, the indicator would need to address the extent to which services are appropriately matched to a student’s needs. To address racial, ethnic, and linguistic disparities in placement into special programs, an indicator system would need to monitor rates of identification and program placement for each group and document the extent to which identification and placement policies are applied in an equitable way. In the case of special education services, we would need measures of rates of identification in various disability categories by group and of the restrictiveness of the placements (e.g., whether and how much time students spend in separate classrooms or schools).

DOMAIN G: EQUITABLE ACCESS TO SUPPORTIVE SCHOOL AND CLASSROOM ENVIRONMENTS

Students need more than challenging courses and effective teachers to thrive academically. They also need physically and emotionally safe learning environments, with a range of supports that pave the way for them to succeed by addressing their socioemotional and academic needs. Safe, sup-

___________________

16 See https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Segregation-SWD_508.pdf.

17 See https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/education/wp/2016/08/23/justice-department-sues-georgia-over-segregation-of-students-with-disabilities/?utm_term=.f5bab3bdb748.

18 See, for example, https://datacenter.kidscount.org/updates/show/150-linguistic-isolation-still-a-challenge and https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/legal-developments/court-decisions/the-educational-implications-of-linguistic-isolation-and-segregation-of-latino-english-language-learners-ells.

portive school environments and access to academic supports, counseling, and referral to social services are especially important for students who experience chronic stressors outside of school that affect their learning and development.

This domain addresses some key school-based features that influence students’ opportunities to learn: strong school climate, the use of preventative, nonexclusionary discipline policies, and socioemotional and mental health supports. Although some of these indicators are difficult to define and measure, they are important to include in a system of educational equity indicators because research is establishing a relationship between these factors and student outcomes and because there is evidence to suggest that there are group differences in access to these supportive factors.

Indicator 14: Disparities in School Climate

School climate is increasingly recognized as an important influence on many student outcomes, with evidence that a healthy climate links directly to achievement, graduation rates, and effective risk prevention (Allensworth and Easton, 2007; Cohen and Geier, 2010; Faster and Lopez, 2013; MacNeil, Prater, and Busch, 2009; Thapa et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). Definitions of school climate vary widely, but, in general, “climate” refers to the way that a school feels to students, as well as to adults who work in the buildings and to family members (Kostyo, Cardichon, and Darling-Hammond, 2018). Aspects of climate can include safety, supportiveness of staff, absence of harassment and discrimination, connectedness among students and staff, sense of fairness, and trust of adults and other peers, among other factors.

There is some evidence that positive school climate is associated with improved outcomes for students, but moreover, schools with hostile climates can negatively affect at-risk students, having been linked to depression, low self-esteem, feelings of victimization, and lower academic achievement (Kosciw et al., 2012; O’Malley et al., 2014; Thapa et al., 2013). At present, data on equitable access to safe, supportive climates are not widely available. In one statewide analysis of Illinois schools, proportionally fewer Chicago public schools had supportive climates than suburban schools and schools in other urban areas (Klugman et al., 2015). Rural and small-town schools were the least likely to have supportive climates. Even for students in the same class and the same school, perceptions of climate can differ. Differences in perceptions of climate across population groups would help identify differences in access to supportive environments.

Climate can be measured through a variety of approaches, including surveys of students, staff, and family members, structured observations of school and classroom environments, and reviews of documentation on such

factors as school conditions and resource availability. Surveys are generally the most suitable method for inclusion in a large-scale data collection effort because they are relatively inexpensive and can be designed to gather perceptions about a broad range of aspects of climate. In addition, survey data can be disaggregated to examine disparities across groups of students.

Although surveys about climate are not routinely administered to schools across the country, several states have adopted climate measures for use in their accountability systems under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), and many school districts also administer climate surveys.19

The Chicago Consortium on School Research has developed robust measures and collected extensive longitudinal data on school climate. Research from Chicago public schools—where nearly 80 percent of students are socioeconomically disadvantaged—as well as the state of Illinois, has shown that students have higher academic achievement in schools in which staff and students report positive school climates than in schools in which staff and students report weak school climates, comparing schools serving students with similar backgrounds (Brookover et al., 1979; Bryk et al., 2010; Haynes, Emmons, and Ben-Avie, 1997; Klugman et al., 2015; Tschannen-Moran, Parish, and DiPaola, 2006). Moreover, improvements in learning gains are higher in schools that have safe, academically focused climates than in those that do not and in schools that see improvements in school climate (Sebastian and Allensworth, 2012; Sebastian, Allensworth, and Stevens, 2014; Sebastian, Huang, and Allensworth, 2017). Other research has found that teacher qualifications were only related to student achievement in schools with safe climates (DeAngelis and Presley, 2011).

Other states and school districts have also developed ways to evaluate school climate:

- Massachusetts: In 2017 the state began collecting information related to students’ socioemotional learning, health, and safety through a separate questionnaire in the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System, the state’s standardized assessment (Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, 2017).

- California: Every 2 years, California’s public school system administers the California Healthy Kids Survey to school staff and students in grades 7-9 to measure climate, student engagement in learning, health, and well-being (Austin et al., 2016).

- Nevada: To address educational equity as required by ESSA, Nevada is developing a school climate and social and emotional learning measure. The survey will be administered to students in grades 5-12

___________________

19 See https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/essa-equity-promise-climate-brief.

and will serve as a needs assessment to inform future efforts related to school climate (U.S. Department of Education, 2017).

The U.S. Department of Education also created a center to help school systems develop safe and supportive learning environments20 and compiled climate survey items that are available for public use.21 The National Institute of Justice recently issued a report focused on creating and sustaining a positive and communal school climate,22 and the Office of Civil Rights issued a report summarizing its findings from data collections on climate and safety in public schools.23

Proposed Measures for Indicator 14

At present, measures of school climate are not ready to be included in a nationwide system of equity indicators. We anticipate that measures of school climate will become more widely used as states work to comply with ESSA. In the meantime, we encourage their use at the local level.

Indicator 15: Disparities in Nonexclusionary Discipline Practices

A school’s approach to student discipline can influence students’ access to equitable learning conditions. Exclusionary discipline policies, such as in- or out-of-school suspension, remove students from the classroom, thereby reducing their opportunities to learn from instruction. As a result, these practices could negatively affect student learning and other outcomes for students who are subjected to them.

Suspensions are often imposed even for such relatively minor and nonviolent infractions as tardiness or failure to show respect to adults (González, 2012). Research suggests that suspension rates are negatively correlated with student achievement (Skiba et al., 2014) and positively correlated with a student’s likelihood of dropping out of school (Flannery, 2015; Rumberger and Losen, 2016). In Chicago, conversely, reductions in the use of suspensions were associated with improvements in students’ test scores and attendance and in perceptions of climate in schools with majority black students (Hinze-Pifer and Sartain, 2018). Suspensions themselves are also associated with school climates that are less safe (Steinberg, Allensworth, and Johnson, 2015).

___________________

20 See https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/.

21 See https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/edscls.

22 See https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/250209.pdf.

23 See https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/school-climate-and-safety.pdf.

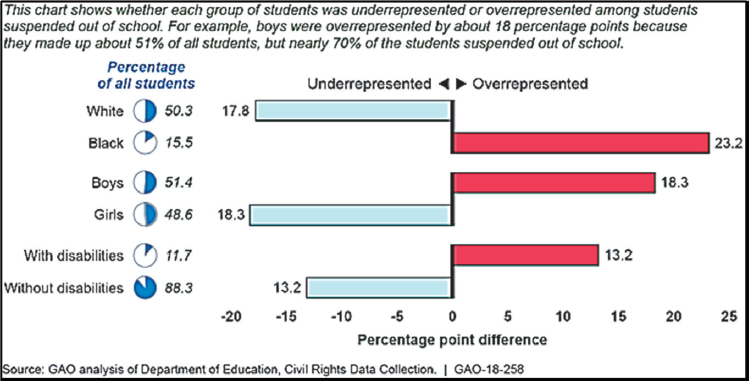

Addressing suspensions is particularly relevant to equity concerns given the large discrepancies in suspension rates across racial and ethnic groups. In California schools, for example, black students were subject to harsher disciplinary actions, including suspensions, compared with their white counterparts (Losen, Martinez, and Gillespie, 2012). Overall, black students tend to be subjected to harsher disciplinary consequences than white students, even for the same infractions in the same schools (Anderson and Ritter, 2017). More broadly, students from underrepresented groups, including students with disabilities, are suspended at disproportionate rates (U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2016; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2018). Evidence suggests that these differences can negatively affect short- and long-term outcomes for some students. Figure 5-2 shows suspension rates nationally for various groups of students.

In recent years, many school districts across the United States have enacted new disciplinary approaches that aim to reduce exclusionary practices. Many of these approaches can be classified as “restorative practices,” which aim to help students build high-quality relationships and develop conflict-resolution skills (Advancement Project, 2014; Fronius et al., 2016). Rigorous research on the effects of these changes to disciplinary policy, or on the supports that educators need to implement them effectively, is limited, but the practices do provide one potential avenue for reducing disruptions in learning due to disciplinary events. It is currently not possible to measure schools’ use of nonexclusionary disciplinary policies, the extent to which teachers are trained to use nonpunitive approaches, or the extent to which they effectively implement these approaches. More-

SOURCE: U.S. Government Accountability Office (2018, Highlights).

over, because the research on the effectiveness of these approaches is so limited, we are not endorsing the creation of an indicator of specific nonexclusionary discipline practices. Until such measures can be developed and the research base becomes more solid, suspension and expulsion rates can be used to indicate the absence of nonexclusionary methods. Although suspension rates are problematic as an indicator of responsiveness, disproportionality in suspensions is a much stronger indicator of inequity. Educators and policy makers can use these data to gather more information on the reasons for group differences that are revealed by differences in suspension rates—including differences in school or district policy—and address those causes.

Proposed Measures for Indicator 15

Suspension and expulsion rates are already being reported by states, as required under ESSA, and are ready for inclusion in the system we propose. Both in-school and out-of-school rates should be tracked.

Indicator 16: Disparities in Nonacademic Supports for Student Success

There are many ways that schools can help support students at risk of school failure. We grouped these supports into four categories, as explained below:

- Socioemotional development: examples include using specific curricular programs, embedding socioemotional learning practices into curriculum and instructing, and embedding socioemotional development into the school climate.

- Meeting the emotional, behavioral, and mental health needs of students who are exposed to violence and other stressors in their homes and neighborhoods: examples of such supports might involve providing onsite counseling or appropriate referral services that help students respond to the traumas that they face.

- Physical health: examples include providing dental or medical screenings for students who otherwise may not have access.

Research on the efficacy of these supports and their links to student outcomes is as wide-ranging as the supports themselves. In some areas, such as the effects of additional instructional time on student achievement, the research is well developed and shows that targeted increases in instructional time, such as through double-dose alge-

bra programs, can boost achievement and attainment.24 In contrast, research on how schools can develop students’ socioemotional competencies25 is less developed. Research suggests that socioemotional competencies are important because they predict later outcomes, including success in the labor market (Deming, 2015; Schanzenbach et al., 2016). Several research syntheses indicate that some instructional programs designed to promote socioemotional skill development have positive effects not only on those skills, but also on a variety of short- and long-term student outcomes, including academic achievement, disciplinary incidents, and postsecondary success (Grant et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2018; Weissberg et al., 2015). In addition, schools can promote socioemotional development through means other than adopting an explicit socioemotional skills curriculum, including through supportive school climates and the adoption of instructional practices that support the development of student agency, collaboration, and related skills (Allensworth et al., 2018; Jones and Kahn, 2017). However, the research does not support conclusions about which of these approaches might be most effective in any given context, and high-quality assessments of socioemotional competencies that could be incorporated into a large-scale indicator system are limited (see Taylor et al., 2018).

This committee’s determination is that schools and districts ought to be providing supports to meet the needs of their populations. Research suggests that the need for extra resources increases commensurate with the rate at which schools serve students with disabilities, English learners, and students from financially disadvantaged families (see Duncombe and Yinger, 2005; Gandara and Rumberger, 2008; Gronberg, Jansen, and Taylor, 2011). This indicator would involve measuring student needs at a school and tracking the level of student supports as it relates to those needs. Educational jurisdictions could track, for example, the provision of before- and after-school programs, free supplemental academic tutoring, the ratio of school counselors and school psychologists to students, and the availability of school nurses. The specific measures of this indicator would be determined locally because they would depend on the needs of the student population in a given educational jurisdiction.

Of course, having such a tailored response requires resources. Although some states have improved the equitable distribution of their resources—that is, students with greater needs receive more resources—there are still states where low-income students receive fewer resources than their more

___________________

24 See http://jhr.uwpress.org/content/50/1/108.short and https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.104.5.400.

25 Socioemotional competencies include interpersonal skills such as teamwork and social awareness and intrapersonal skills such as self-regulation and persistence (Taylor et al., 2018).

affluent peers. The most recent causal research suggests that equity-oriented finance reforms boost educational outcomes, especially for students at risk of school failure (Jackson, 2018; Jackson, Johnson, Persico, 2016; Lafortune, Rothstein, and Whitmore-Schanzenbach, 2016).

Proposed Measures for Indicator 16

Measures for Indicator 16 should include the availability of supports for socioemotional development; emotional, behavioral, and mental health; and physical health. These measures are not yet available at a national level but should be tracked at a local or state level.

REVIEW OF EXISTING DATA SOURCES AND PUBLICATIONS

A key part of the committee’s work was to investigate the potential usefulness of existing data systems and indicator reports for our proposed indicator set. Box 4-2 in Chapter 4 shows the criteria we used. Overall, while there is a wealth of information on pre-K to grade 12 education, the existing data and reports are not sufficient for the set of educational equity indicators as we have conceptualized them. Relevant information is scattered across multiple databases, which define some indicators and measure some constructs in different ways, do not provide any measures for some constructs, vary in data collection procedures, frequency, geographic detail, and coverage of student groups of interest, and are accessible through different agencies and organizations.

Tables 5-9, 5-10, 5-11, and 5-12 summarize the potential data sources for each of the nine indicators and specific constructs for each indicator that we propose for Domains D, E, F, and G, respectively. The tables also summarize the extent to which data are ready with which to develop specific measures of each construct, and if not ready, what is needed. These tables draw on the information on existing data systems in Appendix A, existing publications that include indicators of educational equity in Appendix B, and our assessment of data and methodological challenges and opportunities for educational equity indicators in Appendix C.

For these domains and indicators, the constructs and measures used pertain to students, categorized by groups of interest, in schools with specific characteristics. At the school level, a measure could be whether the student body is predominantly low, middle, or high income, for example—defining those three categories relative to the district as a whole, the state, or the nation. Corresponding measures for multi-school districts, states, and the nation would be the percentage of students in each group of interest attending schools with student bodies that are predominantly low, middle, or high income, however defined (see Appendix C). As noted

| Constructs | Source (Characteristics) |

|---|---|

| Indicator 8: Disparities in Students’ Exposure to Racial, Ethnic, and Economic Segregation | |

| Concentration of Poverty in Schools Racial Segregation Within and Across Schools |

Source: EDFacts (as part of ESSA reporting requirements) Frequency: Annual Geographic detail: Nation, states, districts, schools (elementary, middle, secondary, other) Student group detail: Race/ethnicity, gender, English-language status, disability status, economically disadvantaged (typically eligible/not eligible for free or reduced-price lunch) Possible measures: Percent students attending low-income, middle-income, high-income schools; percent students attending schools with high, medium, and low percentages of specified race/ethnicity groups Future potential: In the case of poverty, because states generally use NSLP eligibility as their indicator of low income, work is needed to develop an appropriate measure—e.g., by having the Census Bureau model ACS poverty data for school attendance areas or student bodies (see Appendix C) |

NOTES: ACS, American Community Survey; NSLP, National School Lunch Program.

in Chapter 4, an appropriate measure of poverty and income status more generally is needed to replace the less and less appropriate measure commonly used—namely, eligibility for free or reduced-price school lunch (see Appendix C). Note also that the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) is a lead data source for many constructs in these four domains.

| Constructs | Source (Characteristics) |

|---|---|

| Indicator 9: Disparities in Access to and Participation in High-Quality Pre-K Programs | |

| Availability of and Participation in Licensed Pre-K Programs | Source: CRDC Frequency: Biannual Geographic detail: Nation, states, districts Student group detail: Race/ethnicity, gender, English-language status, disability status Possible measures: Percent students in districts that offer pre-K; percent children ages 3-5 enrolled in pre-K when offered by district Comment: This is a proxy measure that does not address quality of programs; also, the CRDC does not capture information on other licensed programs such as Head Start (NIEER surveys of states asks about all pre-K programs they fund plus Head Start and special education—see Appendix B) Future potential: Substantial work would be required to develop standard rating systems for pre-K quality for programs offered by districts and other organizations, building on state experience with various rating systems; NIEER’s surveys ask basic facts that could contribute to a quality measure, including hours pre-K offered, whether teachers have a B.A., teacher-student ratio, etc. |

NOTES: CRDC, Civil Rights Data Collection; NIEER, National Institute for Early Education Research.

| Constructs | Source (Characteristics) |

|---|---|

| Indicator 10: Disparities in Access to Effective Teaching | |

| Teachers’ Years of Experience | Source (1): NTPS Frequency: Biannual Geographic detail: Nation (sample too small for finer detail) Student group detail: Nothing for students, but has school level (elementary, middle, secondary) and percent students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch Possible measures: Percent all students (nationwide) attending schools (by level and percent NSLP) with low, moderate, high percent teachers with, say, 5+ years teaching (select threshold based on evidence of teaching effectiveness) Source (2): CRDC Frequency: Biannual Geographic detail: Nation, states, districts, schools (elementary, middle, secondary school, other) Student group detail: Race/ethnicity, gender, English-language status, disability status Possible measures: Percent students attending schools with low, moderate, high percent teachers with 2+ years teaching Future potential: The CRCD only distinguishes teachers with 1, 2, or 3+ years teaching; could construct from SLDS as more states develop them in a comparable manner, include information on teacher experience, and provide access for statistical purposes |

| Constructs | Source (Characteristics) |

|---|---|

| Teachers’ Credentials, Certification | Source: CRDC Frequency: Biannual Geographic detail: Nation, states, districts, schools (elementary, middle, secondary, other) Student group detail: Race/ethnicity, gender, English-language status, disability status Possible measures: Percent students attending schools with low, moderate, high percent fully certified teachers; percent students in grades 7-8 and 9-12 attending schools with all math classes taught by teachers certified in math |

| Racial and Ethnic Diversity of the Teaching Force | Source: NTPS (see Teachers’ Years of Experience, Source (1), above) Future potential: Construct from SLDS as more states develop them in a comparable manner, include information on race/ethnicity of teachers, and provide access for statistical purposes; could possibly construct measures of percent students in schools with high, medium, or low percent teachers with the same race/ethnicity as majority of students in school and classroom |

| Indicator 11: Disparities in Access to and Enrollment in Rigorous Coursework | |

| Availability and Enrollment in Advanced, Rigorous Coursework | Source: CRDC Frequency: Biannual Geographic detail: Nation, states, districts, middle schools Student group detail: Race/ethnicity, gender, English-language status, disability status Possible measures: Percent students in grades 7-8 in middle schools that offer algebra I; percent students in grade 8 enrolled when offered (also has information on high school enrollment in various science and math courses) Future potential: Construct more complete measures from transcript information from SLDS as more states develop them in a comparable manner and provide access for statistical purposes |

| Constructs | Source (Characteristics) |

|---|---|

| Availability and Enrollment in AP, IB, Dual Enrollment, and Gifted and Talented Programs | Source: CRDC Frequency: Biannual Geographic detail: Nation, states, districts, high schools Student group detail: Race/ethnicity, gender, English-language status, disability status Possible measures: Percent students in high schools that offer AP (IB) (DE) (G&T) courses; percent students enrolled when offered (also has information on G&T in elementary and middle schools) |

| Indicator 12: Disparities in Curricular Breadth | |

| Availability and Enrollment in Coursework in the Arts, Social Sciences, Sciences, and Technology | Source: None at present (except that CRDC has information on science and computer science classes in high schools) Desirable possible measures: Percent students in schools (by level) that offer complete range of subjects by (most generous) state standards Future potential: Construct from SLDS as more states develop them in a comparable manner and provide access for statistical purposes |

| Indicator 13: Disparities in Access to High-Quality Academic Supports | |

| Access to and Participation in Formalized Systems of Tutoring or Other Types of Academic Supports | Source: None at present (except that CRDC has information on numbers of FTE instructional aides; it also has information about access to and enrollment in various courses for student groups, which could help identify the extent to which English-language learners and students with disabilities are receiving appropriate academic support) Desirable possible measures: Percent students in schools (by level) that have low, medium, high ratios of tutors, counselors, and other support staff per student; percent students using such resources Future potential: Further research and data collection are needed to develop useful measures for this construct |

NOTES: AP, Advanced Placement; CRDC, Civil Rights Data Collection; DE, dual enrollment (high school and college); FTE, full-time equivalent; G&T, gifted and talented; IB, International Baccalaureate; NTPS, National Teacher and Principal Survey; SLDS, Statewide Longitudinal Data System.

| Constructs | Source (Characteristics) |

|---|---|

| Indicator 14: Disparities in School Climate | |

| Perceptions of Safety, Academic Support, Academically Focused Culture, and Teacher-Student Trust | Source (1): NCES 2012 EDSCS Pilot, School Safety and Environment Modules Frequency: One-time; survey instruments are provided to states, school districts, and schools for their use Geographic detail: Nation (sample too small for finer detail) Student group detail: Race/ethnicity, gender, whether in special education Grade/level detail: Tested questions are available for school climate, including safety and environment (physical, instructional), as seen by 5th- to 12th-grade students, staff, and parents Possible measures: Percent students in schools (grades 5-6, 7-8, 9-12) with scale scores above a specified level Future potential: Use tested questions in EDSCS to develop assessments that are feasible to administer by schools at scale, nationwide and annually Source (2): CRDC Comment: School administrators provide counts on harassment, bullying, and school safety, which could be aggregated into one or more scales; however, these include only those incidents known to administrators |

| Constructs | Source (Characteristics) |

|---|---|

| Indicator 15: Disparities in Nonexclusionary Discipline Practices | |