3

Effectiveness, Safety, and Cost-Effectiveness of Nonpharmacological and Nonsurgical Therapies for Chronic Pain

Over an approximate 10-year period from 2000 to 2010, there was an approximate four-fold increase in opioid prescribing, despite limited short-term benefits, lack of data on long-term benefits, and clear evidence of serious harms, said Roger Chou, professor of medicine, medical informatics, and clinical epidemiology at the Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine. Other pharmacological treatments for pain are also associated with similarly modest benefits, said Chou, without the risk of overdose or opioid use disorder. A systematic review that he and colleagues conducted found that of the many medications evaluated for the

treatment of low back pain, only nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, muscle relaxants, and duloxetine had small and mostly short-term effects (Chou et al., 2017). The limited effectiveness and potential for harm from pharmacological treatments has fueled interest and shifted the emphasis of treatment toward nonpharmacological therapies. However, when the new guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were published in 2016 recommending nonpharmacological therapy and nonopioid pharmacological therapy for chronic pain (Dowell et al., 2016), Chou said there was minimal direct evidence to support the recommendation at that time. Nonetheless, he said the steering committee for the scientific review that had been conducted believed the body of evidence was sufficient to support the recommendation.

Another driver for emphasizing nonpharmacological approaches has been the evolution in the understanding of chronic pain from a biomedical to a biopsychosocial model, said Chou. For example, psychosocial factors are known to predict more strongly the transition to chronic pain and severity than biological factors assessed with imaging studies and laboratory tests. Thus, he said, effective treatment strategies require addressing psychosocial contributors. In addition, improvements in function as well as pain are required for a treatment to be considered effective (Chou and Shekelle, 2010; Gatchel et al., 2007). Chou cited the STarT Back trial as one that demonstrated improved outcomes using this approach. The study stratified patients according to psychosocial factors that influence their risk of developing chronic low back pain, and then used a stepped-care approach to deliver more intensive cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) informed physiotherapy aimed at reducing disability and improving function to those at higher risk (Hill et al., 2011).

Chou described the various therapies he and his colleagues have considered when developing guidelines for the nonpharmacological treatment of pain:

- CBT, a psychological treatment that focuses on restructuring maladaptive thinking patterns and replacing them with healthier behaviors.

- Biofeedback, which uses sensors that provide feedback in order to help people control processes that are usually involuntary and thus help with relaxation and coping.

- Mind–body interventions, including meditation, relaxation, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and movement-based therapies such as yoga and tai chi.

- Exercise therapies of many different types.

- Interdisciplinary rehabilitation that combines physical and biopsychosocial approaches.

- Classic integrative alternative or complementary therapies, including manipulation, acupuncture, and massage.

- Physical modalities such as ultrasound, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), low-level laser therapy, traction, and lumbar supports.

To evaluate the evidence supporting these approaches, Chou and colleagues focused on low back pain, the leading cause of disability according to the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study and a condition reported by more than half of regular opioid users (Deyo et al., 2015; Vos et al., 2015). Recent studies indicate that the prevalence of low back pain has increased in recent years, said Chou, suggesting that the current biomedical approach of using more opioids, imaging, and surgery may not be working (Buser et al., 2018).

EXAMINING THE EFFECTIVENESS AND SAFETY OF NONPHARMACOLOGICAL APPROACHES

Most of the evidence on the effectiveness of nonpharmacological pain treatments has been collected in patients with low back pain, said Chou. He noted several challenges associated with collecting these data, including the inability to mask treatments, variability in techniques and intensity of treatments, differences among providers, the small magnitude and duration of effects, interindividual variability including the presence of psychological comorbidities, maladaptive coping behaviors, fear avoidance, catastrophizing, sensitization of the central nervous system, and concomitant use of opioids. Furthermore, data on functional effects have been limited. Studies of nonpharmacological approaches have also had methodological limitations as well as factors related to professional bias, for example, if chiropractors, rather than neutral investigators, are the sole authors involved in studies of chiropractic interventions.

Chou presented data from a review published in 2007 by the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Pain Society (APS) (Chou et al., 2007). In 2007, there was some fair- to good-quality evidence of small to substantial benefits for many of the nonpharmacological therapies, although the evidence for physical modalities was so poor that the

committee was unable to estimate the magnitude of benefit. The result of this analysis led to the ACP/APS low back pain guidelines, which were the first national guidelines to recommend spinal manipulation, massage, yoga, acupuncture, and progressive relaxation as treatment options for low back pain. However, the analysis provided little guidance on the optimal techniques, intensity, duration, timing, or sequence of therapies, or on how to select a therapy for a particular individual, said Chou.

The subsequent analysis published in 2017 found more evidence to support yoga, tai chi, and MBSR, but still found little evidence to support the use of physical modalities, said Chou (see Table 3-1). This analysis led to the publication of updated ACP clinical practice guidelines, which recommended nonpharmacological therapies as the preferred treatment for chronic back pain (Qaseem et al., 2017).

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality asked Chou and colleagues to conduct another review in 2018, this time focusing on the durability of effects for noninvasive, nonpharmacological treatments for chronic pain. In this report (see Table 3-2), data from studies examining five common chronic pain conditions (low back pain, neck pain, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and tension headache) were included. Interventions were compared against usual care, sham, attention control, or wait list. The

TABLE 3-1 Effectiveness and Strength of Evidence of Nonpharmacological Treatments for Chronic Pain Versus Sham, No Treatment, or Usual Care as Described in the 2017 American College of Physicians Systematic Review on Low Back Pain

| Intervention | Magnitude of Effect | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

|

Acupuncture |

Moderate |

Low–moderate |

|

Exercise |

Small |

Moderate |

|

Interdisciplinary rehabilitation |

Moderate |

Low–moderate |

|

Massage |

No effect |

Low |

|

Psychological interventions |

Small–moderate–improved |

Low–moderate |

|

Spinal manipulation |

No effect–small |

Low |

|

Tai chi |

Moderate |

Low |

|

Yoga |

Small–moderate |

Low |

SOURCES: Presented by Roger Chou, December 4, 2018; derived from Qaseem et al., 2017.

TABLE 3-2 Comparative Effectiveness of Noninvasive Treatments for Low Back Pain Compared with Usual Care, Sham, Attention Control, or Waitlist; Effectiveness and Strength of Evidence (SOE) of Noninvasive, Nonpharmacological Interventions on Function and Pain Over Short Term (<6 Months), Intermediate Term (≥6 to <12 Months), and Long Term (≥12 Months); Number of + Signs Indicate Strength of Evidence

| Intervention | Function Short-Term |

Function Intermediate-Term |

Function Long-Term |

Pain Short-Term |

Pain Intermediate-Term |

Pain Long-Term |

| Effect Size SOE |

Effect Size SOE |

Effect Size SOE |

Effect Size SOE |

Effect Size SOE |

Effect Size SOE |

|

| Exercise | slight + |

none + |

none + |

slight ++ | moderate + |

moderate + |

| Psychological Therapies: CBT primarily | slight ++ |

slight ++ |

slight ++ |

slight ++ |

slight ++ |

slight ++ |

| Physical Modalities: Ultrasound | insufficient evidence | no evidence | no evidence | none + |

no evidence | no evidence |

| Physical Modalities: Low-Level Laser Therapy | slight + |

none + |

no evidence | moderate + |

none + |

no evidence |

| Manual Therapies: Spinal Manipulation | slight + |

slight + |

no evidence | none + |

slight ++ |

no evidence |

| Manual Therapies: Massage | slight ++ |

none + |

no evidence | slight ++ |

none + |

no evidence |

| Manual Therapies: Traction | none + |

no evidence | no evidence | none + |

no evidence | no evidence |

| Mindfulness Practices: MBSR | none + |

none + |

none + |

slight ++ |

slight + |

none + |

| Mind-Body Practices: Yoga | slight ++ |

slight + |

no evidence | moderate + |

moderate ++ |

no evidence |

| Acupuncture | slight + |

none + |

none + |

slight ++ |

none + |

slight + |

| Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation | slight + |

slight + |

none + |

slight ++ |

slight ++ |

none + |

NOTE: CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; MBSR = mindfulness-based stress reduction.

SOURCES: Presented by Roger Chou, December 4, 2018; from Skelly et al., 2018.

review also evaluated head-to-head comparisons; exercise was used as a standard head-to-head comparator for all conditions other than tension headache, which was compared with biofeedback. In this study, no treatments were determined to have substantial benefits; however, there was evidence for moderate long-term effects following a course of exercise therapy and slight long-term effects following psychological therapy (primarily CBT). Chou noted that for chronic low back pain, there was some evidence of persistent benefits from multidisciplinary rehabilitation, but limited benefits for other chronic pain conditions and little evidence to support the use of specific techniques, duration, intensity, or sequencing of therapies.1

Chou said little evidence showed whether the use of nonpharmacological therapies influenced opioid use and associated harms. Few harms were reported in trials of nonpharmacological treatment, including few serious harms with spinal manipulation, he added. David Elton reported similar findings when he and his colleagues analyzed data from people with neck pain who experienced cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) (Kosloff et al., 2015). They concluded there was no association between the neck pain and spinal manipulation. Indeed, he said, patients with neck pain were more likely to have a CVA following treatment by a primary care provider than a chiropractor. Few studies have looked at the effect of these treatments on depression and suicidality, Chou added.

Daniel Cherkin commented that while the conclusion of most of these studies (Qaseem et al., 2017; Skelley et al., 2018) was that both pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments were ineffective or had small average effects, responder analyses suggest about 20 percent of patients experience clinically meaningful improvements in functional outcomes. What we do not know, he said, is whether the same 20 percent would benefit from many treatments or if a different 20 percent would benefit from each specific treatment.

Kurt Kroenke agreed, but pointed out that while nonspecific effects may be discounted in trials, they are optimized in clinical practice. He suggested that the nonspecific benefits of a treatment and the role of the therapeutic relationship are underestimated. Kroenke and his colleagues have found that in clinical trials, a thorough pain history of prior treatments takes about 15 minutes, which, in itself, may be the most useful step in

___________________

1 Following the workshop, Andrew Vickers and colleagues (2018) published a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of acupuncture for chronic pain management. See https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1526590017307800 (accessed March 13, 2019).

planning to the optimal treatment strategy for the patient. Sadly, however, there is insufficient time for that in clinical practice, he said.

With regard to potential disparities, Chou said little evidence to understand differences in effectiveness among indigent or socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, despite variations in access and presence of comorbidities. Similarly, there is little evidence of age, race, or ethnicity effects, although patient expectations and beliefs can impact effectiveness and may be influenced by culture and where one lives. He agreed that more studies are needed to assess differential effectiveness in subpopulations.

Sharing information with patients and clinicians from the systematic evidence reviews that have been conducted has proved to be challenging because the reports are so long, said Chou. The Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 209, for example, is nearly 1,400 pages long (Skelly et al., 2018). He described two apps—MAGICapp2 and Tableau3—designed to make this information more accessible by allowing users to click on particular conditions and outcomes data with different interventions. Chou said there are other efforts to make these data more informative and usable, including living systematic reviews that allow evidence reviews to be continually updated, open-access reviews, and the use of novel analytic technologies.

As reported in Chapter 2, Christin Veasley mentioned some of the reasons for the lack of strong evidence to support the use of nonpharmacological therapies. Chou added that few studies report levels of adherence to a treatment protocol, which can be a significant complicating factor. To move forward and develop the necessary evidence, Veasley said a number of questions need to be addressed, including whether a stepped or adaptive approach is needed to understand the efficacy of combined therapies; whether there are core components across nonpharmacological interventions that account for efficacy that could be standardized across studies; which research models and study designs would provide the rigor needed to generate evidence in a timely manner; and how the field can evaluate the efficacy of many types of interventions across pain conditions.

___________________

2 For more information about MAGICapp, see https://app.magicapp.org (accessed February 6, 2019).

3 For more information about Tableau, see https://www.tableau.com (accessed February 6, 2019).

COST-EFFECTIVENESS AND COST SAVINGS FROM A SOCIETAL PERSPECTIVE

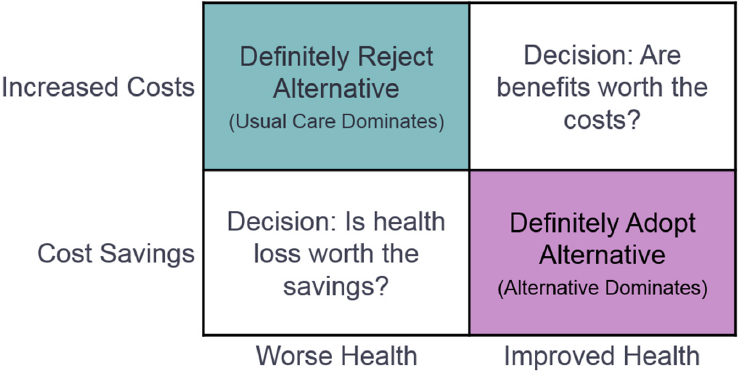

Beyond assessing whether a new treatment improves health compared to usual care, health economists such as Patricia Herman, senior behavioral scientist at the RAND Corporation, also ask about cost-effectiveness—whether the treatment increases or reduces costs compared with usual care. If health improves but costs increase, policy makers must then decide whether the additional health benefits are worth the costs, including both costs borne by patients, payers, and health systems as well as societal costs such as low productivity, she said (see Figure 3-1). A metric that health economists use to quantify the benefit of a treatment is quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), which combine increases in both length and quality of life, said Herman. Anything below $50,000 per QALY is generally considered cost-effective, adding that some interventions may be cost savings if, for example, a treatment reduces the need for surgery, imaging, or injections.

In 2012, Herman and colleagues published a systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of complementary therapies and integrative care (Herman et al., 2012). They reviewed studies that evaluated costs compared with usual care from the perspective of a hospital, payer, employer, or society in general. Herman noted that economic outcomes cannot be generalized across settings, but the information obtained in one setting can be adjusted to other settings through simulation modeling. Of the 28 higher quality

SOURCE: Presented by Patricia Herman, December 4, 2018.

studies identified, two-thirds had to do with pain and included a variety of interventions, including exercise, acupuncture, naturopathic care, massage, chiropractic, and other forms of manipulation. Five of these interventions were found to result in cost savings, while the costs of most of the others ranged from $3,000 to $28,000 per QALY. Only one exceeded the $50,000/QALY threshold. Evaluations of most of the low-cost interventions used a societal perspective that included productivity gains. Herman added that for some studies, costs might have been even lower if health care cost reductions had been captured over a longer period.

Another study using simulation modeling to assess the cost-effectiveness of cognitive and mind–body therapies for chronic low back pain was published in 2017 by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) (Tice et al., 2017). Models such as this allow researchers to fill in the gaps that exist with patient data to help understand the cost-effectiveness of interventions and to see where to target future studies, said Herman. From the perspective of the health care system and in terms of improvements in chronic pain, the ICER model indicated that two interventions—MBSR and yoga—were of high value and that two others—acupuncture and CBT—were of intermediate value. They recommended coverage for all four of those treatments, said Herman.

At RAND, Herman and colleagues have been working on a model for chronic low back pain that incorporates actual patient data on health care costs, productivity costs, and health-related quality of life for four health states: no pain, low-impact chronic pain, moderate-impact chronic pain, and high-impact chronic pain. This model allowed the researchers to carve out data from patients with different pain states to show that costs in the high-impact chronic pain group are most affected by various treatments and to determine which treatments provide the most cost savings. Thus, said Herman, the biggest benefits from a societal perspective should come from providing this group of patients with a variety of nonpharmacological interventions.

POTENTIAL RESEARCH PRIORITIES MOVING FORWARD

Chou suggested several priorities for future research on the effectiveness of nonpharmacological therapies, including

- Developing a better understanding of the long-term sustainability of intervention effects;

- Exploring whether treatments increase or decrease opioid use;

- Standardizing interventions to enable better interpretation of results; and

- Comparing nonpharmacological to pharmacological treatments.

Benjamin Kligler, director of complementary and integrative health for the Department of Veterans Affairs, added another research priority: Exploring at both a practice and systems level how best to implement new interventions and enhance access, including the best time to implement. Herman suggested additional research priorities to increase understanding of cost-effectiveness:

- Include measures of cost in all studies of effectiveness;

- Identify and target high-impact chronic pain to get the greatest impact;

- Expand the use of economic modeling using available evidence to better understand the economic impact of treatments; and

- Expand the use of simulations to enable the design of targeted trials.