On Day 2 of the workshop, attendees self-selected into one of two tracks for focused discussions exploring aspects of the education to practice continuum. Those in the first group (Track One) followed up on the previous day’s discussion about attracting, retaining, and supporting health professions educators. They also discussed how to build a stronger connection between “disruptive innovators” across education and practice (see Box 7-1 for “Track One Context” information). Those in the second group (Track Two) shared their thoughts on potential actions they feel can be taken if the workforce—both existing and future—is to be prepared to fill an evolving role in a rapidly changing health care system (see Box 7-2 for “Track Two Context” information).

CONNECTING DISRUPTIVE INNOVATORS ACROSS EDUCATION AND PRACTICE

Opening Discussion

Bushardt and Woolforde opened the breakout session with a quote from the former president of the Macy Foundation, George Thibault (2013):

The culture change that is needed to achieve a closer linkage between education and practice in a collaborative, interprofessional environment will require leadership, careful planning, innovative uses of technology, new partnerships, and faculty development. The health care workforce for tomorrow needs to be educated and trained in settings that are models for the efficient, reliable, collaborative practice that leads to the best patient outcomes.

Although health care has changed significantly in the 5 years since Thibault made this observation, said Bushardt, the constructs and framework are still relevant today. Thibault focused on six priority areas for health professions education and these areas were reflected in the conversations held at the workshop, added Bushardt:

- Interprofessional education

- New models for clinical education

- New content to complement the biological sciences

- New educational models based on competency

- New educational technologies

- Faculty development for instructional and educational innovation

Bushardt then harkened back to insights gained during the previous day’s breakout session on envisioning future educators (see Chapter 6). He and Woolforde reviewed the various comments made in an effort to distill possible overarching themes stemming from the three questions discussed within the 12 interprofessional teams. Those themes, he said, included leadership, population health, teaching methods, technology, emotional intelligence, cognition in the future, big data, and social and health equity. Bushardt’s aim was to link those conversations with the goals of the current session.

Session Goals

Bushardt and Woolforde reiterated the objective of the current session, which was to build on ideas from the previous day’s discussions that focus on next steps for how education and educators can drive the incorporation of care delivery innovation into education. The hope, said Bushardt, is to start “building a bridge” between education and practice. Bushardt and Woolforde then asked workshop participants to reflect on the themes from the previous day’s discussions and to think about the most urgent needs so that a strong connection can be made between education and practice. In response, several people commented on the importance of shifting incentives in support of current and future health professions educators. Kathy Chappell, American Nurses Credentialing Center, pointed out how the difficulties remain the same despite years of knowing what they are. This illustrates the problem, she said, that the current education-to-practice continuum does not prioritize nor incentivize continuing professional development. Both educators and practitioners must juggle competing priorities, as in the case of clinician educators who spend time focusing on academic achievement and advancement but then have less time for seeing patients.

In order to ensure that professional development is prioritized, said another participant, it must be embedded in the system whether through accreditation requirements, employer expectations, or other mechanisms. The end goal, she added, is to “build a health care workforce for the future, whether that is [through] the student pipeline or developing new skills in the current workforce, in order to meet the changing needs of the population.”

Another misalignment of incentives, said Chappell, involves accreditation standards and the health needs of communities. For example, nursing schools focus on preparing students to pass the National Council Licensure Examination, which is acute care–oriented. The curriculum is driven by the focus of the licensure exam rather than by the needs of students or the patients and families they will serve in the future. She said, “As much as people think we need to be educating for the community setting, it’s not going to happen while the incentives are misaligned.” In order to change these types of incentives, she added, all stakeholders—including accreditors, academics, and practitioners—must be present at the table and committed to making change.

Michelle Troseth, National Academies of Practice, recognized that, while there is a big focus on the importance of interprofessional collaboration among professions, there needs to be equal focus on working interprofessionally across education and practice. Troseth explained that education is often “isolated” from practice, yet building a strong pipeline of health professions educators will necessitate drawing on the experiences and knowledge of health care practitioners and administrators. Mark Merrick, representing the Athletic Training Strategic Alliance, added that clinicians bring enormous value to education and that it would be shortsighted to only consider full-time faculty as educators; students and their future patients will be best served when they are educated by a wide variety of educators, he noted, including clinicians. This requires creating the kind of health professions education that would truly prepare students for the future of health care. However, as Merrick observed, “resistance from faculty” is a significant barrier. Some faculty, he said, do not see the need for change and “would love for us to go back to teaching it the way we did twenty years ago because that was the ‘right’ way.” Merrick further stated that, in order to affect change, there needs to be “faculty and educators who are focused on where we are going; not where we have been.”

A final comment from Troseth challenged everyone in the room to think differently about the gap between education and practice. Many people want to identify a specific “problem” within health care, she said, and then develop some explicit solutions to fix it. However, preparing for the future of health care is not a simplistic problem to be solved. Rather, said Troseth, providers must acknowledge that it is a complex system that

includes “paradoxes, dilemmas, and polarities.” There are multiple tensions within the system, and multiple interactions between parts of the system. She said “there is not a quick fix,” nor is there a discrete problem to solve; there are “many dilemmas that we have to manage as leaders.” With this perspective in mind, the group began to explore and discuss models—for example, polarity thinking—that use various frameworks to address complex problems like the integration of education and practice.

Implications for Faculty Development for Emerging Clinical Teachers at Distributed Sites

Julia Blitz of the Centre for Health Professions Education and Marietjie de Villiers of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, both with Stellenbosch University in South Africa, joined the first group (Track One) through a virtual connection to present their research on the views and experiences of rural clinical preceptors. Blitz and de Villiers, along with their colleague Susan van Schalkwyk, collaborated to study and understand how clinicians working in rural environments view their roles as educators (Blitz et al., 2018). This effort was initiated, said Blitz, by a request from the government of South Africa to increase the number of graduates in all health professions in order to meet the needs of their respective communities. It was also driven by a desire to move health professions education out of the academic health complexes and into more realistic care settings and communities. Blitz noted that, according to the Ecology of Medical Care concept (Stewart and Ryan, 2015), which offers a population-based snapshot of health care needs and usage, only 1 person in 1,000 ever reaches an academic health center; therefore, unless students are trained outside of these centers, they will not have the full range of skills they need to care for patients in the environments where patients are likely to be found.

A distributed clinical platform, said Blitz, extends beyond traditional academic health centers. The sites where students are placed are chosen for a variety of reasons, including accessibility, patient profile, and space for students. However, Blitz added, placing students at these sites for clinical training means there are significant “human, technological, and financial” resource limitations. The research question that Blitz and her team were trying to answer through their work was: “How do clinicians working at distant, resource-constrained, and emerging training sites view their early experiences of having been delegated the task of clinical teaching?”

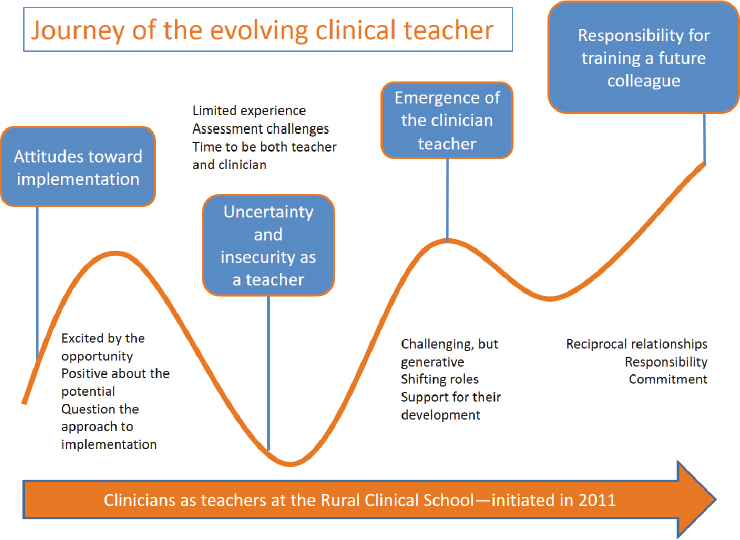

Blitz explained how their research began at a rural clinical school that was started in 2011. The researchers found that clinical teacher experiences evolved over time, she said, starting with excitement about the opportunity

but apprehension over the approach. The next phase of the journey was uncertainty and insecurity as a teacher, mixed with reservations about whether they had enough time to perform both their teaching and their clinical responsibilities. The clinician-teacher emerged in the third stage, with preceptors finding the work to be challenging but doable with the support of faculty. Finally, the preceptors saw themselves not as teachers but rather as having the responsibility for training future colleagues. In this stage, Blitz remarked, the preceptors saw reciprocal relationships between themselves and the students, as well as between themselves and the faculty. Blitz said that, at this point, “they were accepting the responsibility that they were being given and were really committing to the process” (see Figure 7-1).

The next step in their research, said Blitz, was “taking it a step more distant” and studying clinicians who were not associated with the creation of an actual rural clinical school. Blitz described the research methods they used for this next step as qualitative research with an interpretivist approach, wherein the researchers conducted in-depth, inductive interviews that were transcribed, anonymized, and coded. Blitz described the areas of research as being focused on “the three rs”—relationships, responsibilities, and resources.

SOURCE: Presented by Blitz and de Villiers, November 14, 2018.

Relationships

Relationships were of two kinds, said Blitz. First were the clinicians’ relationships with students. She explained that, as educators, the clinicians reported enjoying learning from and with students, and they understood the importance of creating a safe learning environment and of engaging the students in the work done by the clinical team. These clinicians saw their roles as part of the effort to meet the country’s health needs. However, they were less positive about their relationships with the medical school. They felt there was a lack of information about clinician responsibilities and inadequate recognition for the contributions they were making. Most of all, the clinician-educators wanted an opportunity for two-way communication with the school, said Blitz. They wanted information (from the school) about the students and they wanted to be able to give input back to the school, describing how the students performed and where the gaps in their knowledge and skills were. In other words, she noted, the “clinicians wanted to co-create the curriculum” and close the gap between the students’ education and what they needed in practice.

Responsibilities

The second focus of their research dealt with the responsibilities of students and the medical school. In this area, said Blitz, clinicians were “very clear that it was the students’ responsibility to learn” rather than the clinicians’ responsibility to teach. They also felt that faculty had the responsibility to give feedback to clinical staff on whether the students were meeting faculty’s expectations in their clinical rotations. Blitz remarked that “uncertainty about expectations” was commented on by the first and second set of clinicians they studied: Both sets were “keen and enthusiastic” but requested more feedback from faculty about how they were doing.

Resources

Regarding clinical teaching, the researchers found that clinicians were turning to their own clinical mentors (rather than the faculty of the medical school) as a pedagogical resource. Blitz commented on how the weak reliance on faculty as an educational resource was likely “a manifestation of the relationship not yet being embedded and not yet being strong enough between the faculty and the emerging clinical leaders.” The clinicians also expressed interest in belonging to a network of clinical educators, she said, that could be a resource for everyone to draw on for ideas and information.

This and other findings led Blitz to two main takeaways from her research. First, that clinician preceptors desire more preparation and support in their roles as educators. It was not sufficient to offer faculty development activities that only consisted of relevant pedagogical knowledge and skills. Organizational development, said Blitz, requires shared ownership; educators—whether full-time faculty or clinician preceptors—must have shared ownership over the educational process. Ensuring a smooth transition between education and practice requires faculty to engage existing networks of clinical practice to improve communication, she added, so that educators and clinicians can learn from each other’s knowledge and skills.

The second big takeaway was about developing sound relationships. One way to build relationships, Blitz noted, is to identify the responsibilities and needs of the parties involved. For example, students could evaluate their experiences of clinical teaching so that clinicians could receive mediated feedback and faculty development directed toward their own identified needs. Relationships between the medical school and clinicians could also be intentionally developed through communication about students and clinical teaching, she remarked. In summary, said Blitz, there needs to be a two-way dialogue between health professions educators and clinical preceptors. Preceptors need to be partners in education who can “bring the clinical practice issues to us.” Woolforde underscored that such a collaboration leading to a co-created curriculum is “disruptive in a good way” and helps “bridge the silos” between health professions educators and health care practice.

Exploring a “Bridging Model”

In the final hour of the breakout session, individual workshop participants discussed how one might potentially move forward with putting ideas into action. Bushardt started the conversation in hopes of sparking reflection and discussion. His list of themes and major takeaways were drawn from what he heard throughout the entire workshop and included the following:

- Changes in the workforce need to happen both through education of new graduates as well as through the retooling of the existing workforce.

- The current system of clinical education is not sustainable, not purposefully integrated, and not well-aligned with the practice environment.

- There are concerns from employers about the pace at which higher education can adapt to evolving practice needs.

- The generalist health professions educator is difficult to create and sustain.

- It is difficult to measure the impact of interprofessional education on patient outcomes and other effects of collaborative practice.

- Workforce and training sites are maldistributed geographically and not aligned with population needs.

- Changes to payment structures and regulatory requirements could drive rapid adoption of more practice-centered standards that have person- and population-centered care and well-being embedded directly into their models.

- It is critical to integrate voices of patients, families, and communities into decision making.

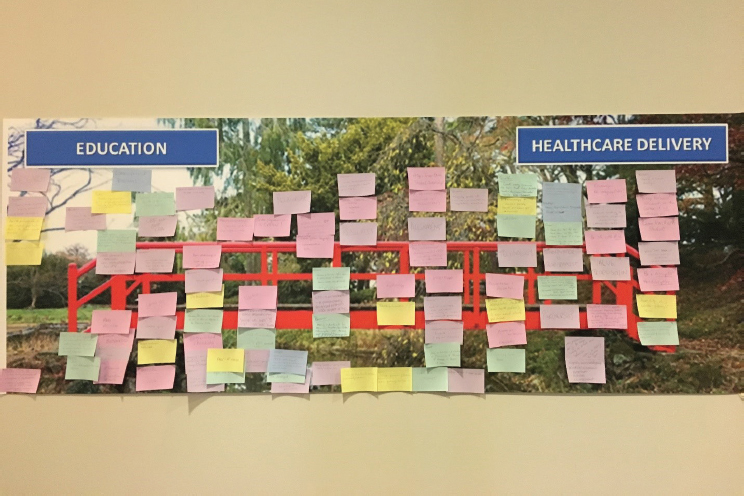

With these overarching themes in mind, Bushardt invited workshop participants to “think about enabling activities” that could help create a “bidirectional transfer and connection between education and practice.” He also asked those within the group to think about barriers that might limit or prevent strong connections between the two sectors. To encourage creativity, Bushardt asked the participants to write their ideas on small sticky notes and to adhere those they considered biodirectional enablers to the rendered railing on a nearby eight-foot-long poster of a bridge (see Figures 7-2 and 7-3); by contrast, they were to adhere sticky-note comments representing obstacles to the space under the bridge. Before starting on their task, Woolforde reminded the attendees to focus on the center of the bridge. In other words, she said, look for common space between “Education” and “Healthcare Delivery” (or practice) to identify areas where the greatest overlap and likelihood of an impact will take place for both education and care delivery.

After each person in the room affixed their education-to-practice enabler and barrier sticky-notes to the bridge image, Woolforde and Bushardt then worked with the group in an attempt to create a semblance of order out of the almost 100 sticky notes scattered across the poster. Each person in the room suggested overarching areas in which their idea, and the ideas of the others, might most appropriately fit. The end result was a set of priority issues—based on individual, interprofessional perspectives from the attendees in the room—that were subdivided into five themes. Bushardt and Woolforde presented each theme as a priority topic along with what they believed to be important actions to take within each specific area. The groupings were as follows:

SOURCES: Photo by Mike Bird on Pexels. Presented by Bushardt and Woolforde, November 14, 2018.

SOURCES: Photo by Mike Bird on Pexels. Presented by Bushardt and Woolforde, November 14, 2018.

Research and Data

- Include preceptors in research.

- Generate data that demonstrate the value proposition for clinical education.

- Use regional health data to drive curricula.

Communities of Practice

- Revise accreditation standards to use as incentives for change.

- Create competencies and evaluation instruments for distance clinical faculty.

- Recognize the importance of interprofessional education.

- Devise systems (both in academia and practice) that value time for collaboration.

Relationships

- Education and delivery must form a partnership of equals around shared goals and values.

- Relationships require shared goals, language, communication, and tools.

- Educator preparation should be intentional.

Alignment

- Align goals of education licensure, accreditation, regulation, and practice.

- Incentivize interprofessional education and collaborative practice.

- Employ interprofessional continuing professional development.

Partnership

- Develop solid infrastructure for partnerships, rather than just ad hoc meetings.

- Adopt a model, framework, approach, or infrastructure to support the partnership (e.g., polarity thinking, graduate medical education).

In addition to these themes, Bushardt called out three other areas that would factor into each of the priorities. They include resources, technology, and innovation. Resources, said Bushardt, are most often thought of

as time, money, and expertise. In her presentation, Blitz had remarked that: “The farther you go away from academic health complexes, the more limited the resources tend to become … human, technological, and financial.” With limited resources, creativity and innovation become virtual necessities.

Technology can facilitate innovation through communication and collaboration Woolforde pointed out before shifting the conversation. She asked each person in the room to state what he or she considered the most urgent issue to address in bridging educators with practitioners. Sara Fletcher of the Physician Assistant Education Association felt it was “incentivizing people early on.” Kathy Chappell for the American Nurses Credentialing Center believed it to be moving the needle: “We are revisiting the same issues. How can this group move ideas forward?” The idea for Troseth was to create strong pipelines between education and practice to bring in new ways of teaching with new partners. Steven Chesbro of the American Physical Therapy Association expressed his view that having benchmarks could be what drives education to a higher level. Accreditation is the minimum, he said, while benchmarks move beyond standards.

Alex Johnson of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Institute of Health Professions believed effective teaching could improve linkages. He commented that “every clinician is a teacher, so how do we frame that throughout training?” Mark Merrick with the Athletic Training Strategic Alliance felt the urgent need was in retooling the current health and education workforce: “Affecting change by bringing in a new cohort takes a long time, so we need to retool the current workforce to work interprofessionally.” The key, for him, was how to affect the future of health care by embedding education into practice. Chappell also remarked on the urgent need to build a workforce that can meet the changing health care needs of the future: “Schools, practitioners, and faculty need to be at the table. We need to align incentives for all stakeholders.”

Troseth described her vision of engaging all stakeholders through what she called a polarity map that uses a sort of yin and yang approach to promote both interprofessional education and collaborative practice. She outlined potential action steps to move forward using polarity mapping, which included

- Setting a common vision across the faculty and care providers.

- Integrating core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice into the curriculum.

- Gaining clarity on individual and team scope of practice that includes addressing areas of overlap.

- Using technology and tools to enhance live collaborative practice.

Based on the discussion, said Woolforde, it seems as if the main area that would better align health professions education with health care delivery involves a combination of relationships, partnerships, alignment, and shared values. She further clarified that such a commitment to a set of values would be demonstrated through a formal agreement or structure implemented on a community level, a national level, and everywhere in between. After further discussion Bushardt expressed his opinion on what he believed he heard, which was a keen interest in making “relationships” the highest priority. In support of this, Shirley Dinkel, Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas, added, “I think relationships come first, because without relationships you don’t have alignment or shared vision.” However, as Blitz pointed out from research, with relationships come the risk of power struggles. Creating strong ties between educators and those in the practice environment will require some thought as to how “academics enter their practice,” she said, and how perceptions of power differentials are overcome. The discussion led to a final comment by Bushardt in proposing his thematic priority list that was informed by the group’s discussions to emphasize or prioritize “building relationships” by creating a solid infrastructure for partnerships.

ALIGNING DISRUPTION WITH INNOVATION

Track Two: Prioritization

The goal for this session, said Barbara Brandt, is to “prioritize what needs to be worked on in terms of urgency.” The health care system, she reiterated, is not incrementally changing but rather is changing quickly and dramatically, and the health professions education system is not prepared for these changes. Box 7-2 provides the context for Brandt’s remarks that were shared with the workshop participants prior to the meeting.

Brandt sought to understand the participants’ views of what constitutes urgency and what related actions might be taken to better prepare educators to work jointly with those in the practice environment. To do this, Brandt asked each breakout group participant to identify three priority actions for bringing practice and education together. Each person’s list would then be discussed within small groups before their ideas were presented to the entire Track Two group. Brandt emphasized her request for urgent actions saying, “If it is not urgent at all, do not put it down.” The reported items expressed by individuals to the larger group were captured by the rapporteur and separated into the following inventory of ideas based on each individual’s proposed action list. This catalogue of ideas separated naturally into divisions starting with the creation of concepts and actions, then moving to the formation of valued activities that includes building the evidence base for the improvement of processes. Better collaboration

and alignment among all relevant stakeholders can lead to an application of team training and an escalation of interprofessional engagement. These divisions are outlined in the lists below.

Creation

- Creating opportunities for co-learning for students and practitioners.

- Creating and reforming financial streams to support health professions education in the community and at other sites.

- Creating financial and time options for health professions students to experience and work in practice settings (including communities).

- Creating a broader sense of understanding and common vision among and across the health professions and educators.

- Creating a compendium of strategies for increasing non-traditional clinical experiences.

- Creating a health care workforce that mirrors the populations served.

- Creating pathways for people in the existing workforce to do things differently; create clear routes for people to retool their careers.

Formation

- Making the case for student value in clinical settings, and/or develop new roles for students to bring value to clinical settings.

- Making changes in education and training funding to allow for training in more locations, in other types of practices, and in ways that promote the broader inclusion of professions.

- Building the evidence base about the link between health outcomes and interprofessional practice.

- Developing pre-service and continued lifelong learning that is focused on interprofessional education that translates into practice.

- Developing more standardized means of assessment.

Improvement

- Improving management processes and sharing of big data.

- Improving health workforce satisfaction and efficiency.

- Changing payment models to make time for collaborative learning; in combination with that, change perverse compensation systems that disincentivize practitioner participation in interprofessional activities.

- Changing accreditation standards to allow non-guild members to serve as preceptors and evaluators, plus align education and delivery accreditation.

- Restructuring financial and resource models for clinical education.

- Expanding the integrated accreditation system internationally.

Collaboration and Alignment

- Collaborating between organizations that represent health professions programs, health regulators, payers, business partners, policy makers, patients, and other stakeholders.

- Aligning education programs to meet the needs in workforce shortage areas.

- Aligning the future health care workforce with the community needs (e.g., geographic and profession/specialty distribution, diversity that mirrors the population).

- Aligning educational programs to meet population health needs.

- Integrating social needs and social factors into the delivery of health care.

- Integrating technology and innovation; health educators are primarily consumers of technology but, instead, need to be at the table developing technologies.

- Bringing together educational accreditors across the health professions and set core interprofessional behaviors and skills.

- Engaging employers and health care systems in understanding the urgency of workforce transformation.

- Working with industry to develop better transition-to-practice models.

Application

- Focusing training on patient outcomes, which will necessitate training in teams.

- Focusing on keeping patients and families in the center of education and practice.

- Identifying, developing, and supporting faculty practitioners to work collaboratively.

- Addressing the financial sustainability of health professions programs at the level of the individual student.

- Using the workforce need and development argument to improve clinical and community experiences for students.

- Selecting future learners differently (e.g., select people who are flexible, quick thinking, curious, and excited to be part of a team).

Escalation

- Increasing longitudinal interprofessional, community-based training.

- Increasing depth and diversity of teams in practice and education, including across disciplines and characteristics such as race and gender.

- Increasing incorporation of patient-reported outcome measures in training and practice.

- Increasing community and patient engagement through practice and education design and function.

- Collecting and using data to drive change, even when it makes people uncomfortable (e.g., be “data agitators”).

- Educating and training that links patients with teams of health professionals working collaboratively.

- Educating students across all professions about critical health systems (e.g., informatics, social determinants, delivery of care).

- Re-educating the existing workforce regarding interprofessionalism and collaborative practice.

After listing these actions, Brandt and her colleagues—Christine Arenson for Thomas Jefferson University and Gerri Lamb for Arizona State University’s Center for Advancing Interprofessional Practice, Education and Research—led the entire group through discussions on the similarities and differences between the proposed items. They also asked those in the room to consider the degree of urgency associated with each action. Breitbach remarked how some of the items were “just best practices” and should already be in place, while other items could require major policy shifts and would, therefore, take some time to implement. Malcolm Cox commented on the difference between priority and impact. Many actions are high priority, he said, but perhaps the focus should be on those actions that will generate the greatest impact. This remark triggered Maria Tassone at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Interprofessional Education to consider looking at the list differently.

She suggested that distinctive actions could be taken on the macro level (e.g., law and policy changes), on the meso level (e.g., organizational initiatives), and on the micro level (e.g., individuals and teams). The macro-level actions would likely take longer to carry out, but hold the potential for greater impacts, while the micro-level actions may have less of a system-wide impact but could be accomplished almost immediately. Caswell Evans from the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Dentistry noted that, in order to accomplish the types of sweeping law and policy changes necessary to impact macro-level issues, health professions would need to advocate for

health care advancement as a unified team. He observed that many of the health professions lobby for policy change as individual organizations. For there to be real change, he said, health professions would have to look beyond their own organizational needs, taking a broader and more inclusive approach wherein all of the health professions would come together for a combined effort toward a unified goal.

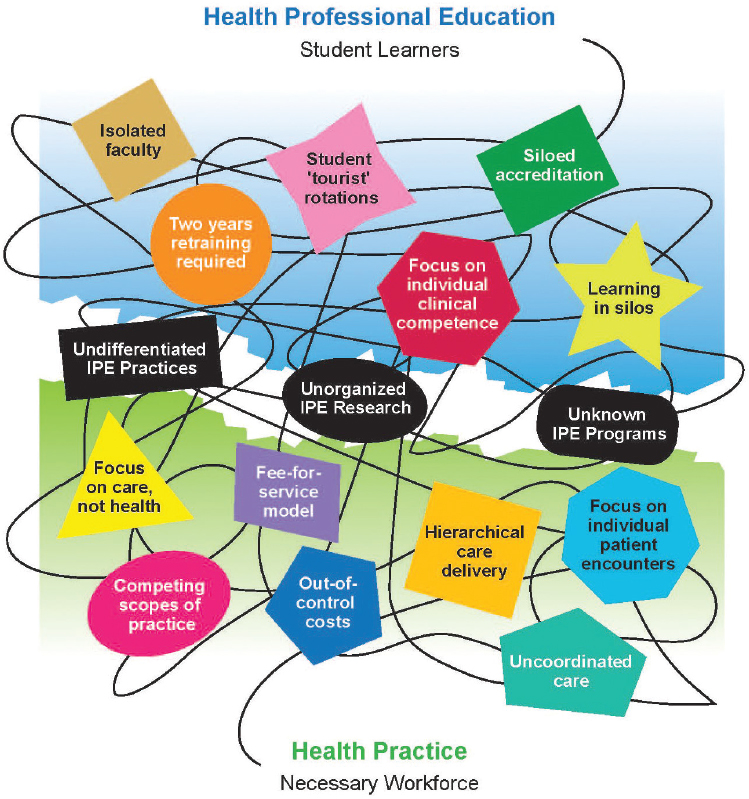

Health Professions Education in the Age of Risk and Innovation

When the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education (the National Center) was first funded in 2012, said Brandt, the gap between health professional education and practice was wide; there was an obvious need to bring the two systems together. Figure 7-4 is a visual depiction of the convoluted connections between education (in blue, above the divide) and health care practice (in green, below the divide). In the years since the establishment of the National Center, added Brandt, there have been massive changes in health care as a system.

The focus of health care is shifting from provider-driven to consumer-driven. New care delivery and payment models are encouraging new roles among existing health providers. At the same time, new roles are emerging: community health workers, care coordinators, community paramedics, etc. Technology and scientific advancements are transforming roles and responsibilities. These changes are not incremental; rather, they represent a major shift. Brandt analogized this change to the Copernican revolution, through which the world vision moved from an Earth-centered model to one where the sun was at the center of the universe. Like the widespread impact of that revolution, she said, changes in health care have resulted in a lot of confusion so that “we are actually [mired] in even more chaos and complexity” than when the National Center emerged in 2012.

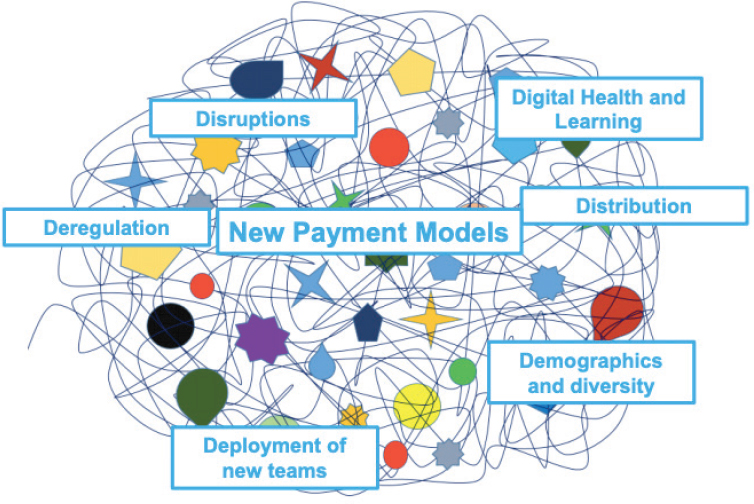

Brandt then listed what she called “The Six Ds,” which she believes could help simplify an exceedingly complex world view of health care into a structure that can more easily open communication with systems leaders (see Figure 7-5). Such conversations with C-suite executives about workforce development are grounded by these Six Ds—disruption, deregulation, distribution, demographics/diversity, deployment of new teams, and digital health/learning—and are typically based on payment models. These payment models, she said, are currently in flux with “one foot in the fee-for-service and one foot in the value-based payment” arenas. Some systems are fully invested in transitioning to value-based payments, while others are resisting change. Disruption is ever-present in the new health care system, she said, with Amazon, CVS, Google, and others entering the health care realm and developing novel ways of meeting patients’ needs.

NOTE: IPE = interprofessional education.

SOURCE: Presented by Brandt, November 14, 2018. Used with permission by Brandt and the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education.

Distribution, demographics, and diversity of the workforce alone are complex issues, Brandt underscored, as she provided the group with examples. Some states have provider shortages, while others have a surplus of providers. In some undergraduate and health professions education, enrollment is decreasing, she added, which causes concern about the future workforce. Certain health professions are rapidly expanding, while others are experiencing declining enrollment numbers. All of that impacts provider roles and models of care, as well as the structure of heath care teams,

SOURCE: Presented by Brandt, November 14, 2018. Used with permission by Brandt and the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education.

Brandt noted, which will require a retooling of the current workforce so that health care teams are designed around maximizing effectiveness and efficiency. In her final comment, Brandt acknowledged that technologies (such as artificial intelligence, health trackers and wearables, and genome sequencing) are rapidly transforming health care. Health education and practice must keep up with these trends, she concluded, if the workforce is to be prepared to navigate future health care systems.

Refining Prioritization

Following Brandt’s presentation, the breakout group members returned to the list of urgent actions they had compiled earlier from individuals’ input. Lamb asked participants to reflect on whether their priorities had shifted after listening to the different perspectives of others. Following some discussion, each participant listed their top three to five priority-action items. This led to a more in-depth dialogue between Lamb and the group as participants described their own, prioritized lists and talked about the differences and overlaps in the various lists. Based on the participants’ descriptions, Lamb projected her list of urgent priorities from which action plans could be derived. That list included

- Collaborate between organizations that represent health professions programs, health regulators, payers, business, policy makers, patients, and other stakeholders.

- Create and reform financial streams to support health professions education in the community and at other sites.

- Integrate social needs and social factors into the delivery of health care.

- Integrate technology and innovation; health educators are primarily consumers of technology but, instead, need to be at the table developing technologies.

- Re-educate the existing workforce regarding interprofessionalism and collaborative practice.

- Engage employers and health care systems in understanding the urgency of workforce transformation.

- Make the case for student value in clinical settings and/or develop new roles for students to bring value to clinical settings.

- Align the future health care workforce with community needs (e.g., geographic and profession/specialty distribution, diversity that mirrors the population).

- Align educational programs to meet population health needs.

Moving Forward

Given Lamb’s list of urgent priorities, the participants discussed possible next steps for moving the items into action. First, however, Brandt and Cox noted that many of these ideas are not novel but have been discussed at length in previous publications, such as the Macy Foundation’s 2013 report Transforming Patient Care: Aligning Interprofessional Education with Clinical Practice Redesign. These sorts of reports help to emphasize the urgency and importance of these ideas, said Cox. Participants then began to discuss how to turn several of the more urgent ideas into action.

On the issue of re-educating and retooling the existing workforce, Frank Ascione with the University of Michigan Center for Interprofessional Education suggested using pilot programs and practice models to demonstrate how this can best be accomplished. Lamb added that once successful models are generated, lessons learned could be quickly spread and pilot programs scaled up, rather than “recreating the wheels over and over” through repeated demonstration projects. Erin Fraher from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill noted that academics can sometimes be reticent to use existing models, adding that implementation and dissemination science can help overcome this barrier. Another way to move this area forward, someone remarked, is to lean on existing organizations such as the

Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education and the National Academies of Practice. These organizations already prioritize education of the existing workforce and would, therefore, likely be great resources for disseminating new ideas. Finally, Joanne Spetz, a health economist with the University of California, San Francisco, said that, in order to move forward on retooling the existing workforce, it is critical that employers recognize both the urgency of doing so and the potential return on investment.

Other ideas were proposed by individual participants that could potentially be useful for moving the identified priorities forward. Those ideas included

- Developing incentive structures, such as grant programs, to encourage collaboration between education and practice.

- Using patient stories and patient perspectives to convince decision makers of the importance of interprofessional care.

- Sending an interprofessional team of representatives to lobby Congress and other entities who “hold the purse strings” in order to reform financial streams.

In considering the third bullet, Cox remarked that it is often more efficacious to suggest that money be moved around into different pots, rather than to ask for additional funds. In other words, he said, when lobbying decision makers for funds to support interprofessional education and practice, it is important “to talk about money, but not just more money.” This notion was backed by another commenter who said “there is money available, but we should make a case” for using it to promote interprofessionalism across the education-to-care spectrum by emphasizing the potential for producing better patient outcomes.

Fraher stressed the importance of interprofessional support while working together to build a better health care system: “This work is important, it is incremental, it takes courage, and we are going to get shot down—so, we need to be supportive of each other. We need to build-in the fact that we all are moving toward this together. We need that support from each other.”

REFERENCES

Blitz, J., M. de Villiers, and S. van Schalkwyk. 2018. Implications for faculty development for emerging clinical teachers at distributed sites: A qualitative interpretivist study. Rural Remote Health 18(2):4482.

Stewart, M., and B. Ryan. 2015. Ecology of health care in Canada. Canadian Family Physician/Médecin de Famille Canadien 61(5):449–453.

Thibault, G. E. 2013. Reforming health professions education will require culture change and closer ties between classroom and practice. Health Affairs 32(11):1928–1932.