2

Lessons Learned and Operating Changes to Consider

This chapter focuses on the value proposition and lessons learned regarding the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) manufacturing innovation institutes and suggested operating changes. The findings in the sections below were captured during the workshop breakout sessions and are based on the perceptions of representatives from each of the stakeholder groups: the DoD institutes, other DoD stakeholders, industry, academia, and other stakeholder groups.

The value proposition section summarizes the stakeholder groups’ assessments of the DoD institutes’ 20 generic offerings, identifying the top-ranked offerings based on both perceived value and the relative cost improvement achieved by the institutes versus obtaining an offering by other means.

The perspectives on current operations section presents the common strengths and weaknesses of the DoD institutes, as determined by each stakeholder group, and includes each groups’ other representative comments.

The perspectives on improvements section summarizes the operating improvements suggested for the DoD institutes by combining inputs from all sources gathered by the committee, including interviews, questionnaires, and the workshop breakout II exercise, “Keep Doing, Stop Doing, Start Doing.”

VALUE PROPOSITION BY STAKEHOLDER GROUP

Workshop participants were asked to assess 20 generic DoD institute offerings (Table 2.1). (Offering numbers are referred to below in square brackets; see also Table B.1 for definitions, including identification of which offerings rely on core

funding.) Using a scale of high, medium, and low, participants were asked to rate how well each of the offerings achieves their organization’s technical development, technical diffusion, and education and workforce development (EWD) needs. The participants were also asked to assess the relative cost and/or difficulty of delivering the offerings in the following two scenarios: (1) without partnering with the DoD institutes and (2) in partnership with the DoD institutes. The ratings were tabulated and analyzed by stakeholder group (see Appendix B).

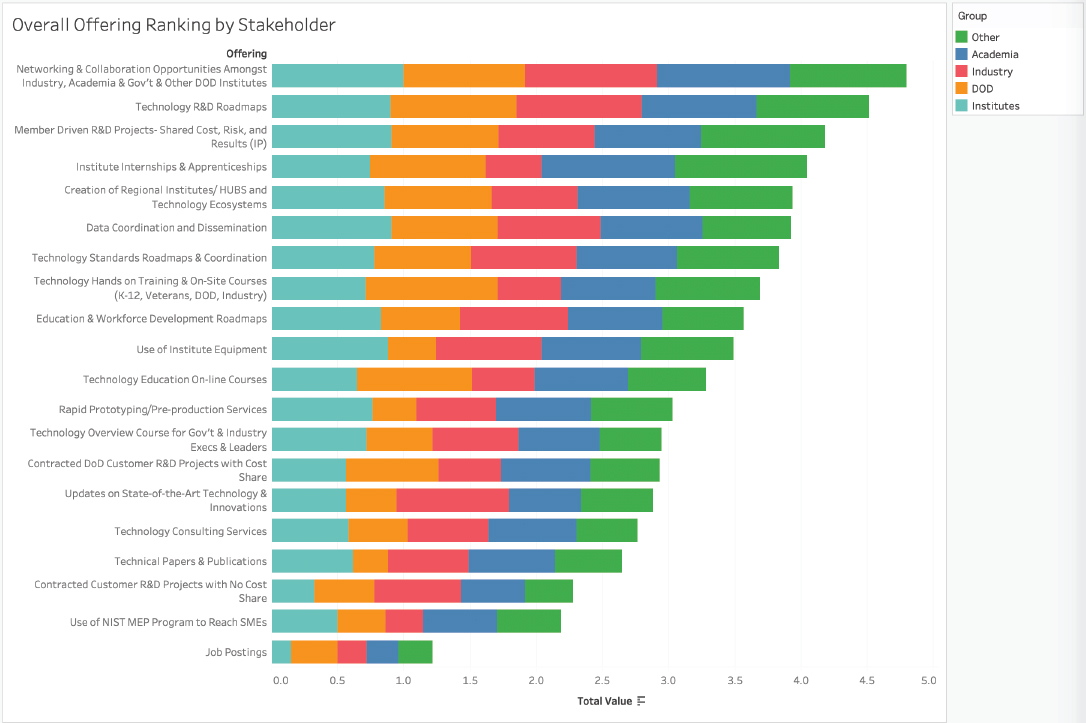

Overall, the top-eight offerings, ranked by the combined observations from all stakeholder groups (see Figure 2.1), were as follows:

Ranking of DoD Institutes’ Offerings by All Stakeholder Groups

- Networking and Collaboration Opportunities

- Technology R&D Roadmaps

- Member-Driven R&D Projects

- Institute Internships and Apprenticeships

- Creation of Regional Institutes/Hubs and Technology Ecosystems

- Data Coordination and Dissemination

- Technology Standards Roadmaps and Coordination

- Technology Hands-on Training and On-Site Courses

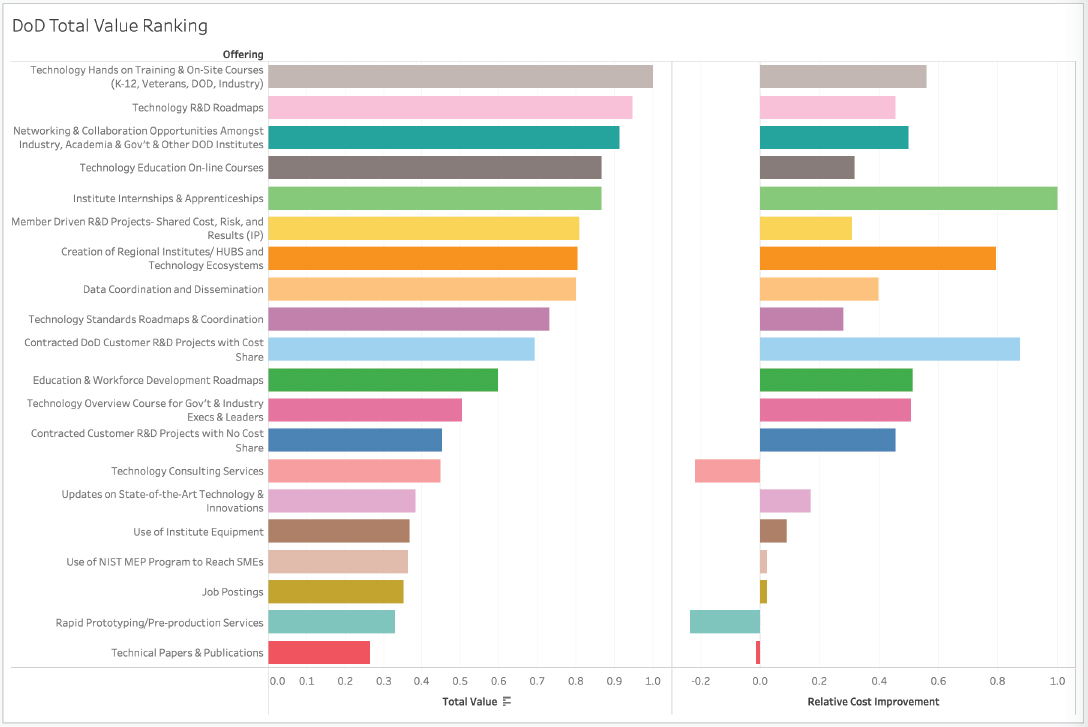

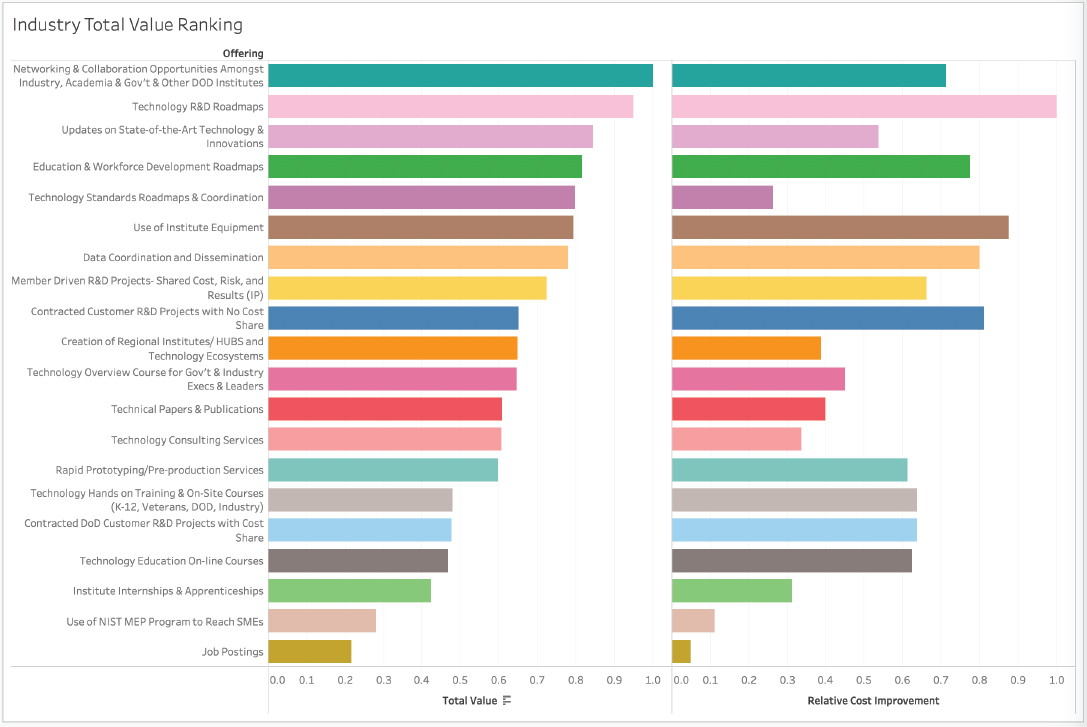

However, differences were noted between key stakeholder groups. For example, comparing the DoD stakeholder group’s ranked offerings (Figure 2.2) to the industry stakeholder group’s ranked offerings (Figure 2.3),

- DoD stakeholders rated technology hands-on training and on-site courses [17] highest, while industry stakeholders rated networking and collaboration opportunities [12] highest.

- DoD stakeholders more highly valued EWD courses and internships [17, 18, 16] over research and development (R&D) projects, while industry stakeholders more highly valued roadmaps for technology [1], standards [5], and EWD [15]; use of institute equipment [8]; and data coordination and dissemination [11].

Interestingly, both DoD’s and the industry’s top-five offerings are 100 percent core funded, thus reinforcing the critical importance of core funding to the success of the DoD institutes.

Ranking of DoD Institutes’ Offerings by DoD Stakeholders

- Technology Hands-on Training and On-Site Courses

- Technology R&D Roadmaps

- Networking and Collaboration Opportunities

TABLE 2.1 Department of Defense Institutes’ Offerings

| Offering # | Generic Offering |

|---|---|

| 1 | Technology R&D Roadmaps |

| 2 | MemberDriven R&D ProjectsShared Cost, Risk, and Results (IP) |

| 3 | Contracted DoD Customer R&D Projects with Cost Share |

| 4 | Contracted Customer R&D Projects with No Cost Share |

| 5 | Technology Standards Roadmaps and Coordination |

| 6 | Technology Consulting Services |

| 7 | Rapid Prototyping/Preproduction Services |

| 8 | Use of Institute Equipment |

| 9 | Updates on StateoftheArt Technology |

| 10 | Technical Papers and Publications |

| 11 | Data Coordination and Dissemination |

| 12 | Networking and Collaboration Opportunities Amongst Industry, Academia, and Government Members and Other DoD Institutes |

| 13 | Creation of Regional Institutes/Hubs and Technology Ecosystems |

| 14 | Use of NIST MEP Program to Reach SMEs |

| 15 | Education and Workforce Development Roadmaps |

| 16 | Institute Internships and Apprenticeships |

| 17 | Technology Handson Training and OnSite Courses (K12, Veterans, DoD, Industry) |

| 18 | Technology Education Online Courses |

| 19 | Technology Overview Courses for Government and Industry Executives and Leaders |

| 20 | Job Postings |

NOTE: MEP, Manufacturing Extension Partnership; NIST, National Institute of Standards and Technology; R&D, research and development; SME, small and mediumsize enterprise.

- Technology Education Online Courses

- Institute Internships and Apprenticeships

Ranking of DoD Institutes’ Offerings by Industry Stakeholders

- Networking and Collaboration Opportunities

- Technology R&D Roadmaps

- Updates on State-of-the-Art Technology

- Education and Workforce Development Roadmaps

- Technology Standards Roadmaps and Coordination

Overall, the relative cost improvement for the institutes’ offerings was ranked by all stakeholder groups (see also Figure B.2):

Ranking of the Relative Cost Improvement for DoD Institutes’ Offerings by All Stakeholder Groups

- Technology R&D Roadmaps

- Education and Workforce Development Roadmaps

- Networking and Collaboration Opportunities

- Use of Institute Equipment

- Creation of Regional Institutes/Hubs and Technology Ecosystems

Similar to the overall value ranking, four of the top-five relative cost improvement offerings are 100 percent core funded (only “Use of Institute Equipment” [8] is project funded). This further emphasizes the critical importance of core funding to the DoD institutes’ value proposition and financial stability.

Regarding relative cost improvements, with the exception of the DoD stakeholders, all of the other stakeholder groups noted positive cost improvements for each of the 20 offerings when working with the institutes versus obtaining the offering without the benefit of an institute (see Appendix B, Figures B.3 to B.7). As for the DoD stakeholder group, they noted negative cost improvement for the following three offerings: “Technology Consulting Services,” “Rapid Prototyping/Pre-Production Services,” and “Technical Papers and Publications.”

Based on these observations, a follow-on study is merited to obtain a deeper understanding of the value proposition for the individual DoD institutes and is included as the first follow-on consensus study topic in Chapter 6.

STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVES ON CURRENT OPERATIONS

The observations contained in this section are a blend of information obtained from personal interviews with individual committee members, questionnaires from each stakeholder group discussed by the committee in open session on January 30, 2019, and from the stakeholders attending the workshop on January 28-29, 2019. The observations from the DoD institute stakeholders are a self-assessment as a group. The observations from the other four stakeholder groups (DoD stakeholders, industry, academia, and other stakeholder organizations) are their assessments of the operations of the DoD institutes from the perspective of their individual groups.

Perspectives from DoD Institute Stakeholders

Representatives from all eight DoD Manufacturing USA manufacturing innovation institutes willingly provided their frank perspectives on the current opera-

tion of the institutes, as a group and as individual institutes. A total of 26 leaders from across the institutes attended the workshop. As expected, there was substantial commonality in their perspectives as well as insights that were meant to be specific to their operation. The following common themes among the strengths, weaknesses, and perspectives, listed below, were identified. The lists are not in any particular priority order.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

Other Comments

- Formal inter-institute collaborations that leverage capabilities for integrated technologies development are opportunities.

- The huge demands for training services and tools to de-risk new technologies are opportunities.

- Foreign investments in advanced manufacturing are outpacing the United States.

- In the global market for R&D, large industry members will choose to do R&D with the countries that provide incentives.

- There is a need to formalize the relationship between all DoD services and the institutes.

- There is a need to improve the connection to the DoD Program Executive Office and requirements communities.

- Getting access to the correct individuals in acquisition programs is difficult, especially with a limited staff.

- The focus on the technology readiness level (TRL)/manufacturing readiness level (MRL) 4-7 “valley of death” is understood, but makes it difficult to satisfy DoD stakeholders looking for TRL 9/MRL 10 products for the warfighter. For some technologies, the institutes need to work at both lower and higher TRLs/MRLs.

As nonprofit organizations, the DoD institutes were established as public–private partnerships with DoD and intended to be mission-driven, conducting R&D focused on TRL/MRL 4-7 for their manufacturing technology, diffusing that technology within the partnership and beyond within the United States, and providing EWD for current and future domestic users of the technology. They were also expected to be self-sustaining, but with a substantial divergence of opinions within DoD of what “self-sustaining” means, as will become apparent from the DoD stakeholder organizations’ input that follows.

As a significant lesson learned, at the time the institutes were established there was no clear, mutual understanding of the scope of the long-term “self-sustained” mission at the end of their initial period of performance. If the future mission expected by DoD includes the current set of offerings that do not generate break-even revenue, such as the coordination of the development of standards with the standards developing organizations, the current level of funding will need to continue.

Congress will support DoD funding for manufacturing. The challenge is to sell it within DoD.

—Congressional Staff Interview

Perspectives from DoD Stakeholders

The committee received inputs from 45 representatives of DoD stakeholders. These stakeholders expressed views on the initial framework of the institutes and how it has changed since implementation; the perceived value of institutes to them as they conduct their own mission or research; and a general consensus that changes were required. Based on the responses received, the population of the DoD stakeholders was clearly bifurcated according to whether the respondent is inside or outside of the DoD Manufacturing USA institute ecosystem.

DoD stakeholders within the DoD Manufacturing USA institute ecosystem identified common themes among the strengths, weaknesses, and perspectives, listed below. The lists are not in any particular priority order.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

Other Comments

- Some level of core funding is still needed.

- A broader DoD engagement is needed.

- Other contracting mechanisms should be assessed such as Other Transaction Authorities (OTAs).

- There is the potential to have a bigger impact.

- Engagement with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Manufacturing Extension Partnerships (MEPs) needs to be assessed.

- Work on higher MRL is needed for transition.

This is about supporting the industrial base. DoD should just make the strategic decision to fund the institutes.

—DoD Stakeholder Interview

DoD stakeholders outside of the DoD Manufacturing USA institute ecosystem identified the common themes among the strengths, weaknesses, and perspectives, listed below. The lists are not in any particular priority order.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

Other Comments

- Funding should be coming from outside of DoD.

- Institutes should be funded on a project basis.

- Other contracting mechanisms should be assessed such as OTAs.

- Institutes should compete for funding like other DoD centers, institutes, and suppliers do.

- The institutes should have better alignment with DoD priorities.

- Value versus other R&D mechanisms is not evident.

- Shift the focus to lower MRLs and better coordinate efforts with the service ManTech organizations. The institutes are not set up for transition.

It’s not an innovation until it solves a warfighter’s problem.

—Pete Newell, former director of the Army Rapid Equipping Force

Within and outside of the ecosystem, there is a general opinion that something needs to be done. A number of innovative ideas were suggested. These included re-competing institutes, standardizing the experience, shifting MRL levels both up

and down, and developing a new set of standard metrics with real consequences for falling short.

There are people in the manufacturing community, both inside and outside of the ecosystem, who would like for the original strategy to continue. In this scenario, the institutes that are seen as having value will continue to receive funding from inside and outside of DoD. There is also a group of people that would like to see the institutes focus on working leading-edge technologies with state-of-the-art equipment. The focus of this effort would be on reducing risk and training the workforce in these technologies.

Perspectives from Industry Stakeholders

The committee received inputs from more than 50 representatives of small, medium-size, and large industries. These stakeholders expressed views on the contributions of the institutes to economic growth and global competitiveness. They agreed with the original President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) Advanced Manufacturing Partnership (AMP)1 mission for the network of institutes to develop a U.S. manufacturing ecosystem in emerging technology areas and to engage in technology maturation to bridge the gap from TRL/MRL 4-7.

The leading reasons for partnering with the DoD institutes, from the perspective of industry stakeholders, were to

- Participate in the development of technology, supply-chain, and EWD roadmaps;

- Participate in precompetitive R&D to accelerate the development of emergent material and manufacturing technologies;

- Leverage facilities to develop and validate new technologies, processes, and products;

- Develop standards and supply chains for current and future product offerings;

- Partner with potential suppliers and customers;

- Access ecosystem of world-class academics in the relevant fields; and

- Access trained workforce and pipeline of graduates.

The lists are not in any particular priority order.

___________________

1 President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), Report to the President on Capturing Domestic Competitive Advantage in Advanced Manufacturing, 2012, Washington, DC, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/administration/eop/ostp/pcast/docsreports.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

Other Comments

- Investments by other nations with planned economies (Germany, Japan, China, South Korea, etc.) overshadow U.S. aggregate investment.

- Members question if there is sufficient funding support to achieve DoD and national objectives.

- Opportunities exist to expand DoD awareness of the institutes and for the institutes to contribute more significantly to DoD’s program deliverables.

- Members desire DoD to fund requirements-driven projects through the DoD institutes.

- Members desire greater access to DoD roadmaps to ensure that institute programs and resources are prioritized and aligned to deliver.

- Opportunities are needed for cross-institute interactions and initiatives—for example, 3D integration of electronics and/or photonics into functional structures would be an ideal collaboration among America Makes, NextFlex, and AIM Photonics.

- Ensure that DoD institutes are focused on delivering value to industry. Required use of DoD institute facilities, laboratories, and/or designated university researchers can restrict the business value associated with the DoD institute project investments.

- More emphasis is needed on commercialization of new capabilities through well-defined, vetted transition plans.

- Loss of federal funding and public partnership would put a program at risk.

- Tension exists between sustainability and providing access to foreign competitors.

- Disruptive technologies have the potential to supplant current areas of focus. Thus, it is imperative that institutes monitor, track, and share technology and market competitive intelligence reports with institute members and utilize this know-how to prioritize programs and manage their portfolio accordingly.

In sum, the industry stakeholders strongly support the collaborative R&D model, where industry, government, and academia partner to accelerate development of emergent material and manufacturing technologies. They view current operations as a good base to build on, but with significant room for improvements that would benefit their stakeholder community needs.

Lockheed Martin is partnering with the DoD and DOE electronics and photonics focused institutes to rapidly mature and transition emerging, high impact electronics and photonics technology innovations to LM product lines and mission platforms to significantly reduce size, weight, power and cost (SWAP-C) and provide advanced, secure capabilities to support the warfighter. These partnerships are providing the critical R&D and manufacturing ecosystems necessary for the preservation and growth of the U.S. electronics industrial base and workforce which benefits the national economy and security.

—Lockheed Martin

Perspectives from Academic Stakeholders

The committee received inputs from about 30 representatives of the academic community. These stakeholders expressed views on the contributions of the DoD Manufacturing USA institutes to their respective academic institutions with respect to education, R&D, and economic development. The lists are not in any particular priority order.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

Other Comments

- One university R&D node became the focus of regional economic development, which provides an incentive for state government to support participation in a DoD Manufacturing USA institute. This model should be studied and replicated in other DoD Manufacturing USA institutes. [13]

- Standardized EWD delivery platform will be beneficial. [15, 17, 18, 19]

- Model pushes to short-term projects despite long-term goals. [3]

- Most representatives were unaware of MEP engagement. [14]

Perspectives from Other Stakeholder Organizations

The committee received input from about 20 representatives of other government agencies and laboratories, congressional and Government Accountability Office staff, professional societies, innovation agents, and policy think tanks. These stakeholders expressed views on the contributions of the institutes to economic growth and global competitiveness but were generally not able to assess the implications for national security priorities in any detail. They agreed with the original PCAST AMP2 mission for the network of institutes to develop a U.S. manufacturing ecosystem in emerging technology areas and engage in technology maturation to

___________________

2 Ibid.

bridge the gap from TRL/MRL 4-7. Although the sample of opinions was not sufficient to represent this entire stakeholder category, the opinions reflected significant commonality regarding current strengths, weaknesses, and other important aspects of the institutes. The lists are not in any particular priority order.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

Other Comments

- Metrics should be TRL/MRL in and out for a whole technology area, creating a U.S. supply chain.

- Continued federal core funding is needed to strengthen the ecosystem; it takes more than 5 years.

- Review and renew/re-compete institute agreements based on value delivered.

- It is a challenge to develop joint efforts across institutes.

- Hands-on training on expensive equipment is important for SMEs.

- Precompetitive research works well for low TRL/MRL, but sharing IP and data becomes difficult as proprietary interests emerge at higher TRLs/MRLs.

In sum, the other organization stakeholders view current operations as a good base to build on, but with significant room for improvements that would benefit their stakeholder community needs.

STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVES ON IMPROVEMENTS

The observations contained in this section are regarding the DoD institutes’ offerings listed in Table 2.1 and the expanded definitions contained in Table B.1 in Appendix B. As before, the observations from the institute stakeholders are a self-assessment as a group. The observations from the other four stakeholder groups (DoD organizations, industry, academia, and other stakeholder organizations) are their assessments of the operations of the DoD institutes from the perspective of their individual groups.

The suggested operating improvements that follow for the DoD institutes are the results of combining inputs from all study sources, including interviews, questionnaires, and the workshop breakout II exercise, “Keep Doing, Stop Doing, Start Doing.” Since the “Keep Doing” inputs received were based on their perceived high importance to each stakeholder group, they have been included as part of the observations with the improvements.

Appendix C combines the observations from each of the stakeholder groups, making it easier to identify key themes across the stakeholder communities.

Perspectives from DoD Institute Stakeholders

The candidate self-improvements identified by the institutes’ senior personnel are a compilation of inputs from all eight DoD institutes. Their suggestions include the following, listed in the order of the 20 identified offerings:

Keep Doing

- Tech roadmaps that leverage diverse perspectives and expertise, eliminating or reducing investment redundancy and the need for each company to start from scratch [1]

- Member-driven R&D that eliminates duplicative investments and risk of “falling behind” [2]

- Contracted DoD customer R&D projects with cost share that eliminates challenge of capability sourcing and sole investment cost [3]

- Innovative approaches to R&D projects generated by nontraditional partnerships [3]

- Contracted DoD R&D projects with no cost share at reduced cost and risk and compress time to market [4]

- Standards coordination and adoption, eliminating confusion and wasted effort [5]

- Technical consulting, including sharing expert knowledge to accelerate adoption [6]

- Conducting rapid prototyping and managing IP in a cost-effective manner [7]

- Neutral place to use institute equipment for demonstrations, process development, and testing [8]

- Continue encouraging equipment supplies to place newest manufacturing equipment in institutes [8]

- Workshops for members (government, industry, and academia) and nonmembers on manufacturing and application topics [9]

- Serving as thought leaders and disseminating information to new stakeholders [9, 10]

- Promoting dialogue and synergies between different disciplines and eliminating unwanted sales-focused discussions [9, 12]

- Quarterly and annual project reports [10]

- Reporting process time and cost, reducing barriers to information access [11]

- Matching start-ups with large companies, creating new business opportunities [12]

- Using MEPs to address SME awareness and knowledge gaps [14]

- Technology training that reduces the manufacturing skills gap and nonstandard approaches [17]

Stop Doing

- Technical consulting not grounded in real-world use cases [6]

- Rapid prototyping and preproduction services [7]

- Holding back information that in many cases is not proprietary [11]

- Development of duplicative content in online courses available from others [18]

Start Doing

- Align roadmapping schedules with DoD key program life cycles [1]

- Coordinate roadmaps across institutes to meet core DoD objectives [1]

- Focus on lower-level TRLs/MRLs with seed money leading to new technologies [2]

- Concerted effort to accelerate project successes [2, 3, 4]

- Provide services, methods, and tools to de-risk new technologies that address huge barriers to adoption [6]

- Market rapid prototyping services to small and medium-size companies [6]

- Provide verification and validation data required for bank loans [7]

- Publish project milestones and outcomes more broadly to raise awareness of institute expertise [10]

- Rapidly translate project outcome to be more usable [11]

- Expand data sharing from members for increased institute membership value [11]

- More DoD engagement at networking events [12]

- Serve as regional coordinating body for R&D and supply chain development to establish a larger technology ecosystem with state support mechanisms [13]

- Reinvent the MEP embed program aligned to institutes that have mature outcomes ready to be shared with SMEs; program needs better definition and timing [14]

- Structure a coordinated plan and integrated roadmap to take EWD activities to multiple stakeholders [15]

- Form an industry lobby group for EWD [15]

- Focus more heavily on workforce development and balance with education outreach [17]

- Short course on specific technologies including the adoption process [18, 19]

- Increase key decision makers’ understanding of emerging technology [19]

- Centralized source to match talent to job opportunities [20]

Perspectives from DoD Stakeholders

While the representatives of DoD stakeholders had various levels of engagement with institutes, all had sufficient familiarity to comment on what to continue or generate and stop doing in each of the key institute offerings. These insights are provided below, listed in the order of the 20 identified offerings.

Keep Doing

- Keep roadmapping with better engagement with DoD roadmaps [1]

- Continue to share knowledge and data with stakeholders [1, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12]

- Establish institutes as “honest brokers” for technology [1, 9, 10, 11, 12]

- Continue funding member-driven R&D to maintain ecosystem [2]

- Continue to support product and IP creation [2, 3, 4]

- Continue to support DoD-directed projects [3, 4]

- Engage with equipment suppliers to ensure that the institute remains state of the art [6, 7, 8, 9]

- Continue to document institute status and successes through quarterly and annual reports [10]

- Maintain outreach to members and nonmembers through workshops [10, 11, 12]

- Continue to enable connection to SMEs [12, 13]

- Maintain workforce development effort of technicians and engineers through hands-on training [16, 17]

Stop Doing

- Eliminate cost-share requirement [2, 3]

- Stop funding redundant work that is going on at DoD laboratories [2, 3, 4]

- Minimize administrative reporting and meetings [2, 3, 4]

Start Doing

- Engage with maintenance and sustainment operations in roadmap [1]

- Translate project outcomes to be more usable [2, 3, 4]

- Focus on lower TRLs to lead technology [2, 3, 4]

- Create and improve business models by looking at new acquisition instruments [2, 3, 4]

- Execute quick projects to demonstrate speed of response to meet DoD need [2, 3, 4]

- Evaluate new methodologies for technology transition [6, 12]

- Create networking events for DoD engagement [12]

- Communicate the value and success of institutes more broadly across DoD [12]

- Coordinate across institutes to meet the DoD mission [12]

- Look for better model to engage NIST’s MEP network [14]

Perspectives from Industry Stakeholders

The representatives of industry had sufficient familiarity with current institute operations to offer well-informed suggestions regarding what to keep doing, stop doing, and start doing in each area of institute offerings. They believed these improvements would increase the value of offerings not only for their organization’s purposes but also for DoD. Their high-priority suggestions include the following, listed in the order of the 20 identified offerings:

Keep Doing

- Industry-led oversight/governance and technology R&D roadmapping leading to strategic investments and sustainability [1]

- Utilize technology roadmaps to organize project calls and fund projects that reduce risk of adoption of technology [1-4]

- Continue to focus on precompetitive R&D projects with clear metrics and accountability [2-4]

- Drive the development and coordination of technology standards roadmaps in order to speed transition to manufacturing and certifications [5]

- Provide access to unique equipment [8]

- Utilize webinars to provide updates on state-of-the art technology and institute programs [9]

- Create and implement robust databases—that is, leverage NextFlex best practices [11]

Stop Doing

- Competitive project calls that require industry to incur significant bid and proposal costs [2]

- Funding lower-TRL projects [2]

- Competing with members and supply base by providing prototype services; rather, serve as matchmaker to those with certified services [7]

- Showroom focus on equipment; rather, focus and utilize equipment for hands-on training and courses [17]

- Job postings. There are better providers. [20]

Start Doing

- Leverage ongoing lower-TRL projects (from the National Science Foundation and/or science and technology) as feeders to institutes [1]

- Couple technology roadmaps with EWD roadmaps and supply-chain roadmaps [1]

- Utilize DoD needs and requirements to feed institute roadmaps and define and prioritize projects [1]

- Benchmark and adopt practices identified in U.S. Manufacturing Council’s “Shaping Future of [National Manufacturing Institute] NMI Best Practices for NMI Success” (2016) [1-5]

- Require all institute-funded projects to include a well-defined transition plan to ensure capabilities in place to enable commercialization [2-4]

- Support broader engagement of supply-chain members [2-4]

- IP policy that encourages commercialization [2-4]

- Establish an IP council comprised of representatives from government, industry, and academia to collaboratively define mutually acceptable IP terms and conditions for the institute [2-4]

- Develop common cost-share/in-kind guidelines across institutes [3]

- Allow institute members to contract directly with the institute rather than requiring subcontracting with each other on projects [3]

- Seek OTA, Military Interdepartmental Purchase Request, and Contract, Cost Plus Fixed Fee opportunities [4]

- Communicate to industry what services are available. Most are unaware. [6]

- Create list of certified suppliers that can provide prototyping services [7]

- Communicate to industry what equipment is available [8]

- Utilize Manufacturing USA newsletter with links to institute newsletters to expand communications reach and impact [9]

- Communicate far, wide, and often—publicize successes [10]

- Improve cross-institute collaboration. Launch cross-institute Grand Challenge. [12]

- Promote commonalities in funding and contracting mechanisms across institutes [12]

- Better visibility and use of NIST’s MEP is needed. Communicate MEP program value proposition to SMEs. [14]

- Expand visibility to industry and increase SMEs participation in internships and apprenticeships [16]

- Institutes should adopt the Lightweight Innovations for Tomorrow (LIFT) model for EWD [17]

- Design for SMEs [17]

- Online education focused on stackable credentials for specific technical standards [18]

- Develop cross-institute overview for C-suite with clear information about return on investment [19]

Perspectives from Academic Stakeholders

Most representatives of academia were very familiar with current operations of the DoD institutes that they work with. They are in a good position to suggest what to keep doing, stop doing, and start doing in each area of institute offers, listed in the order of the 20 identified offerings.

Keep Doing

- Roadmap development [1, 5, 15]

- Standards development [5]

- Tech maturation and rapid prototyping capability [7, 8]

- Shared use of DoD Manufacturing USA institute equipment and facilities [8]

- Leverage partnerships, especially supply chains [12]

- Creating or expanding internship and apprenticeship opportunities [16]

Stop Doing

- Reduce or stop project cost share which is challenging for academia and not sustainable [2, 3]

- Stop contributing to bureaucratic drag [3, 4]

- Stop IP leakage to international competition [11]

Start Doing

- Project calls should be better aligned with the expertise, capabilities, and priorities of academia in mind [3, 4]

- Standards and material databases are critical to technology development and diffusion; however, mission-oriented agencies do not sponsor such projects. The academic group believes that development of standards or materials databases can be a unique value proposition for the DoD Manufacturing USA institutes [5, 11]

- Improved mechanisms for university faculty are needed for them to team up with industry practitioners and researchers [12]

- Most faculty would like to work on cross-institute programs; however, the current models do not support or promote cross-institute collaboration [12]

- Some universities have unique capabilities and facilities that, if properly leveraged and utilized, can become the nuclei of regional economic development, which provides an incentive for state government to support participation in a DoD Manufacturing USA institute [13]

- For EWD initiatives, the DoD Manufacturing USA institutes should standardize delivery platforms for accelerated, cost-effective technology diffusion [15, 17, 18, 19]

- The group from academia would like to see an increase of DoD Manufacturing USA institute internship positions for both undergraduate and graduate students [16]

Perspectives from Other Stakeholder Organizations

The representatives of other stakeholder organizations had sufficient familiarity with current DoD institute operations to offer well-informed suggestions regarding what to keep doing, stop doing, and start doing in each area of institute offerings. They believed these improvements would increase the value of offerings not only for their organization’s purposes but also for DoD. Their high-priority suggestions include the following, listed in the order of the 20 identified offerings:

Keep Doing

- R&D projects, but with better performance metrics and accountability [2]

- Standards development [5]

- Shared use of institute equipment, but with guaranteed time slots [8]

- Skills certification standards, but with expanded roadmaps, common curricula, and better linkage to existing programs [15]

Stop Doing

- Competing with private-sector consulting services [6]

- DoD policy discouraging collaboration with non-DoD institutes [12]

- The MEP embed program (unless evaluation shows its effectiveness can be improved) [14]

- Competing with existing online education programs [18]

- Job postings (done better by commercial systems) [20]

Start Doing

- Clarify areas of distinction and areas of collaboration among institutes [1]

- Connection to contracted R&D customers, clearinghouse for opportunities [2]

- Streamline cost accounting for cost share, use Small Business Innovation Research accounting standards [3]

- License methodologies to private-sector consulting organizations [6]

- Emphasize speed to market for prototyping services [7]

- Communicate far, wide, and often—publicize successes [10]

- Improve cross-institute collaboration. Launch cross-institute Grand Challenge. [12]

- Promote commonalities in funding and contracting mechanisms across institutes [12]

- Expand EWD collaboration with regional educational institutions [13]

- Expand participation in internships and apprenticeships [16]

- Forge stronger linkages to existing education programs, avoid duplication [17]

- Establish national skills certification, work with professional societies and educators [17]

- Online education focused on specific technical standards [18]