1

DoD Manufacturing USA Institutes: Background and Study Design

The importance of the manufacturing sector to the nation’s economic well-being and national security cannot be overstated.1 Manufacturing makes up 8.5 percent of U.S. employment and 11.7 percent of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP),2 but it drives 35 percent of productivity growth, 60 percent of exports,3 and 70 percent of private-sector research and development (R&D).4 Beyond the economy, manufacturing and the strength of the U.S. manufacturing supply chain are also critical to national security.5

The United States leads the world in innovation and inventions, yet many U.S. research discoveries are translated into manufacturing capabilities and cutting-edge products outside of the United States. In countries known for their manufacturing strength, such as Germany and China, this transition is facilitated by coordinated

___________________

1 National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2018, Manufacturing USA Annual Report, FY 2017, NIST AMS 600-3, August, https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.AMS.600-3.

2 Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Commerce, 2018, “Interactive Access to Industry Economic Accounts Data: GDP by Industry,” release date November 1, https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=51&step=1#reqid=51&step=51&isuri=1&5114=a&5102===.

3 International Trade Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, 2017, “National Trade Data: Product Profiles of U.S. Merchandise Trade with a Selected Market,” Trade Stats Express, http://tse.export.gov/tse/tsehome.aspx.

4 S. Ramaswamy, J. Mayika, G. Pinkus, K. George, J. Law, T. Gambell, and A. Serafino, 2017, Making It in America: Revitalizing U.S. Manufacturing, McKinsey Global Institute, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/americas, p. 75.

5 Executive Office of the President, 2017, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, Washington, DC, p. 55.

planning and national investments in advanced manufacturing programs, supporting the private sector’s push to develop new manufacturing processes and products.6,7

The challenges facing U.S. manufacturing8 jobs and supply chains have been recognized at the highest levels in the current and prior administrations.

In June 2011, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) recommended the formation of the “Advanced Manufacturing Partnership” (AMP).9 AMP was charged with identifying collaborative opportunities among industry, academia, and government that would catalyze development and investment in emerging technologies, policies, and partnerships, with the potential to transform and reinvigorate advanced manufacturing in the United States. Its first set of recommendations, “Report to the President on Capturing Domestic Competitive Advantage in Advanced Manufacturing,” was issued in July 2012.10 In the 2012 report, PCAST recommended the establishment of a national network of public–private partnerships (institutes) designed to foster innovation ecosystems for advanced manufacturing. Regarding the use of public–private partnerships, the report observed the following:

In cases where the risk to develop a novel, breakthrough technology is too great to be borne by one entity alone, public–private partnerships can accelerate the transformation of ideas to marketable goods while de-risking the investment during development. By leveraging underlying strengths that enable U.S. manufacturing enterprises to be responsive to changes in the global market, and combining them with an appropriate amount of structure, innovation in key, cross-cutting manufacturing technologies will be accelerated.

The PCAST recommendation included a statement that each manufacturing innovation institute should “receive support via a mixed funding model from industry, academia, and government, with government (state or federal) funding guaranteed for a minimum of 5 years with the potential of renewal for a total of 10 years.”

___________________

6 E. Reynolds and H. Samel, 2013, “Invented in America, Scaled Up Overseas,” Mechanical Engineering Magazine, November, https://www.asme.org.

7 G. Pisano and W. Shih, 2009, “Restoring American Competitiveness,” Harvard Business Review, July-August.

8 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), 2017, U.S. Manufacturing: Federal Programs Reported Providing Support and Addressing Trends, March, https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/683753.pdf.

9 Executive Office of the President and President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), 2011, Report to the President on Ensuring American Leadership in Advanced Manufacturing, Washington, DC.

10 Executive Office of the President and PCAST, 2012. Report to the President on Capturing Domestic Competitive Advantage in Advanced Manufacturing, Washington, DC.

Subsequently, after a nationwide outreach and engagement effort, “The National Network for Manufacturing Innovation [NNMI]: A Preliminary Design,” was issued in January 2013.11 In September 2013, a second iteration of AMP was formed—the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership Steering Committee 2.0 (AMP 2.0). The steering committee, whose members are among the nation’s leaders in industry, academia, and labor, was also a working group organized by PCAST. The AMP 2.0 final report,12 issued in November 2014, focused on a renewed, cross-sector, national effort to secure U.S. leadership in the emerging technologies that will create high-quality manufacturing jobs and enhance U.S global competitiveness.13 In December 2014, Congress passed the Revitalize American Manufacturing and Innovation Act, established an Advanced Manufacturing National Program Office (AMNPO), and authorized the Department of Commerce (DOC) to hold “open-topic” competitions for Manufacturing USA institutes. Today the NNMI is known as Manufacturing USA.

In 2018, the White House issued the Strategy for American Leadership in Advanced Manufacturing14 with goals to (1) develop and transition new manufacturing technologies; (2) educate, train, and connect the manufacturing workforce; and (3) expand the capabilities of the domestic manufacturing supply chain. The Manufacturing USA institutes contribute to all of these national goals.

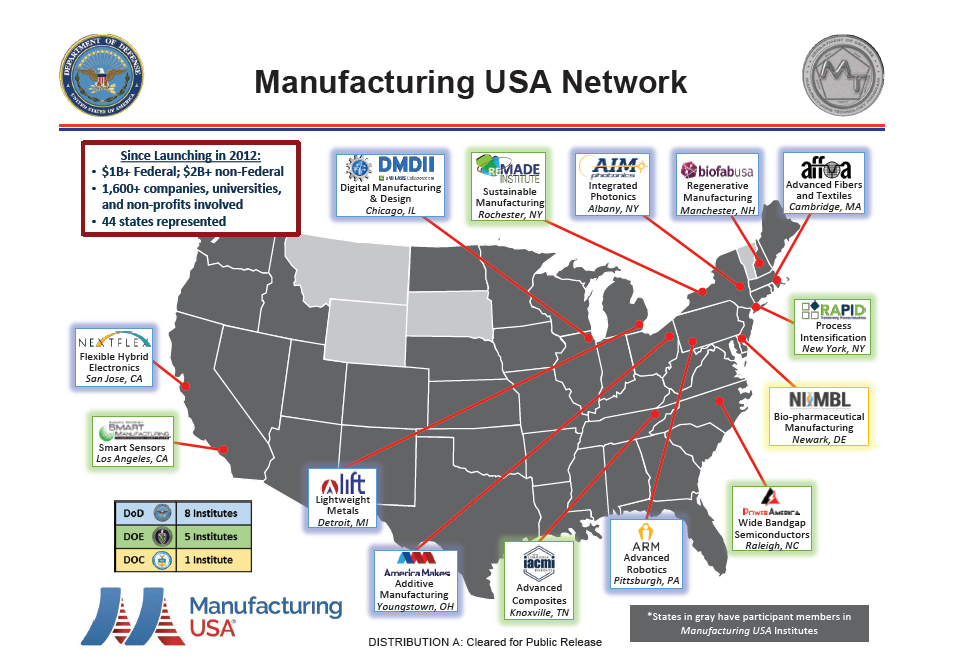

Over the past 6 years, 14 Manufacturing USA institutes have been established—8 by the Department of Defense (DoD), 5 by the Department of Energy (DOE), and 1 by the DOC (see Figure 1.1).15 To date, more than $3 billion has been invested in the Manufacturing USA institutes in establishing and operating these institutes, with greater than $2 billion from industry and nonfederal government sources.

To date, DoD has invested $600 million directly in its Manufacturing USA institutes with the understanding that the initial federal investment included onetime, start-up funding to establish the institutes within a period of 5 to 7 years. They were established by DoD through its Defense-wide Manufacturing Science

___________________

11 Executive Office of the President, National Science and Technology Council, and Advanced Manufacturing National Program Office, 2013, National Network for Manufacturing Innovation: A Preliminary Design, Washington, DC.

12 Executive Office of the President and PCAST, 2014, Report to the President Accelerating U.S. Advanced Manufacturing, Washington, DC.

13 There are also more recent reports focusing on U.S. competitiveness, such as GAO, 2018, Considerations for Maintaining U.S. Competitiveness in Quantum Computing, Synthetic Biology, and Other Potentially Transformational Research Areas, September, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/694962.pdf.

14 Executive Office of the President, 2018, Strategy for American Leadership in Advanced Manufacturing, A Report by the Subcommittee on Advanced Manufacturing Committee on Technology of the National Science and Technology Council, October, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Advanced-Manufacturing-Strategic-Plan-2018.pdf.

15 Tracy Frost, Director, Manufacturing Technology, OUSD(R&E) Strategic Technology Protection and Exploitation, 2018, “DoD Manufacturing Technology Program Briefing,” DoD MFGUSA Institutes 101 Briefing 20181029, October, Unclassified/Distribution A.

and Technology (DMS&T) program element within the DoD Manufacturing Technology (ManTech) program. The stand-up of the current DoD institutes was based on three common design tenets:16

- Invest in applied research and industrial-relevant manufacturing technologies (cost-matched),

- Establish regional hubs of manufacturing excellence with national impact, and

- Focus on education and workforce development needs.

The tenet to invest in applied research and industrial-relevant manufacturing technologies was defined to be within the technology readiness levels (TRLs) and manufacturing readiness levels (MRLs) of 4 to 7. The fundamental objective of the regional hubs with national impact was to conduct ongoing technology diffusion of the resulting R&D across the U.S. defense and commercial industrial base.

SOURCE: DoD Manufacturing Technologies (ManTech).

___________________

16 Ibid.

BUSINESS MODELS USED TO STAND UP AND OPERATE THE DOD INSTITUTES

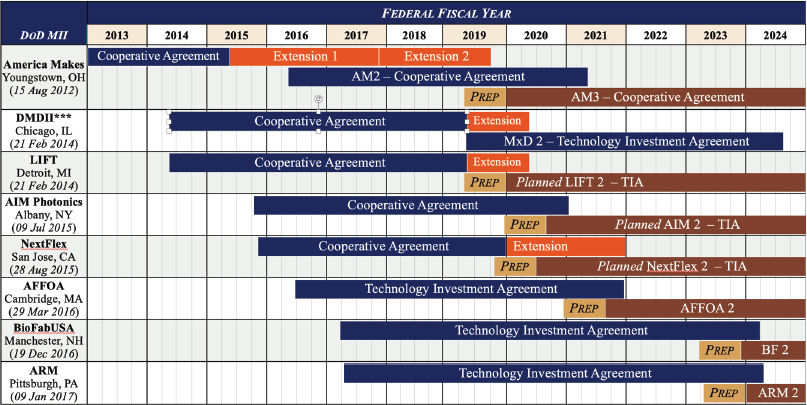

Although the DoD institutes are based on three common design tenets applied to TRL/MRL 4-7 and have common generic offerings (see Appendix B, Table B.1), their business models differ based on their operating philosophies and nuances in their technology areas. Differences also exist in DoD contract type, terms and conditions, duration, and federal start-up funding. Table 1.1 shows the schedule of initial assistance agreements for the DoD Manufacturing USA network of eight institutes.

The following are brief descriptions of the Manufacturing USA institutes established as public–private partnerships by DoD:

- AFFOA (Advanced Functional Fabrics of America) is working to enable a manufacturing-based revolution by transforming traditional fibers, yarns, and fabrics into highly sophisticated integrated and networked devices and systems.

- AIM Photonics (American Institute for Manufacturing Integrated Photonics) is working to accelerate the transition of integrated photonic solutions from innovation to manufacturing-ready deployment in systems spanning commercial and defense applications.

- America Makes (National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute) is a national accelerator and the nation’s leading collaborative partner for technology research, discovery, creation, and innovation in additive manufacturing and 3D printing.

- ARM (Advanced Robotics Manufacturing) has the mission to create and then deploy robotic technology by integrating the diverse collection of industry practices and institutional knowledge across many disciplines—sensor technologies, end-effector development, software and artificial intelligence, materials science, human and machine behavior modeling, and quality assurance—to realize the promises of a robust manufacturing innovation ecosystem.

- BioFabUSA (Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute) has the mission to make practical the large-scale manufacturing of engineered tissues and tissue-related technologies to benefit existing industries and grow new ones.

- DMDII (Digital Manufacturing and Design Innovation Institute) is working to enable factories across the United States to deploy digital manufacturing and design technologies so those factories can become more efficient and cost-competitive.

- LIFT (Lightweight Innovations for Tomorrow) is working to develop and deploy advanced lightweight materials manufacturing technologies.

- NextFlex (America’s Flexible Hybrid Electronics Manufacturing Institute) has the mission of adding electronics to new and unique materials that are part of our everyday lives in conjunction with the power of silicon integrated circuits to create conformable and stretchable smart products.

All of the DoD institutes are nonprofit tax-exempt entities as defined by the Internal Revenue Code.17 Most are 501(c)(3) organizations, while some later established institutes are 501(c)(6) organizations. Table 1.2 compares the common differences between the two types of tax-exempt entities.

One of the institutes, NextFlex, has established a for-profit C Corporation for conducting commercial business as a wholly owned subsidiary of their 501(c)(6) and established a nonprofit 501(c)(3) wholly owned subsidiary of the 501(c)(6) to receive funding from other charitable organizations that sponsor workforce development and training activities. Another institute, DMDII, established a for-profit subsidiary to take advantage of DoD’s Mentor Protégée Program designed to provide assistance in securing new sources of DoD funding.

Each institute has a unique membership structure, membership fees, and a legally binding membership agreement executed with its members. The diverse membership agreements stipulate how intellectual property (IP) is managed and shared with the members. Depending on their nonprofit operating philosophy,

TABLE 1.1 DoD Manufacturing Innovation Institute Agreement and Acquisition Timelines as of March 2019

NOTE: *** DMDII renamed to Manufacturing Times Digital (MxD) February 28, 2019; MII, Manufacturing Innovation Institute; TIA, technology investment agreement.

___________________

17 Internal Revenue Service, 2018, Tax-Exempt Status for Your Organization, IRS Publication 557, revised January, http://www.IRS.gov.

TABLE 1.2 Common Differences Between 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(6) Tax Exempt Organizations

| 501(c)(3) | 501(c)(6) |

|---|---|

| Operated exclusively for charitable, educational, religious, literary, or scientific purposes | Operated to promote a common business interest, and to improve business conditions in the industry |

| Includes membership associations (e.g., professional society), if the purpose is to advance the profession with respect to “educational” activities | A membership organization (e.g., business league, industry trade association), advancing a common business interest |

| Lobbying and political activities are significantly restricted. A c(3) will lose taxexempt status if the IRS determines that it has engaged in “substantial” lobbying activities | Allowed a widerange of lobbying. Yet, the main stipulation is that a c(6) is required to disclose to membership the percent of its annual dues that is lobbying (i.e., nondeductible to members for tax purposes) |

| Special Advantages of the c(3) include: | |

| Enhanced fundraising advantages, such as eligibility to receive taxdeductible “charitable contributions” and gifts of property and eligibility to receive many grants | Dues or other payments to a c(6) are only deductible to the extent that they serve an “ordinary and necessary” business purpose of the payer |

| Eligibility to receive other state and local tax exemptions (e.g., sales tax) | |

SOURCE: J. Scott Dick, 2015, “501(c)(3) or 501(c)(6)—What’s the difference?,” The AMR Blog, July 4, https://www.amrms.com/Blog/ArtMID/448/ArticleID/25/501c3or501c6.

not all institutes retain IP ownership for revenue generation in an attempt to avoid competing with their dues-paying members.

Annual revenue from membership fees across the DoD institutes varied from 4 to 12 percent, with one institute not sharing its percentage. Each institute reported substantial industry cost-share commitments that exceeded the federal funding commitment. A committee finding from interviews was that the larger state cost-share contributions came from the states of New York, Michigan, Illinois, and Massachusetts. There were also indications that state and regional cost share was less likely to be available after the initial start-up investment. All anticipate ongoing project cost share from their members.

Largely driven by their respective technologies, the institutes also vary in the cost of their fixed assets. For example, AIM Photonics, much like any leading-edge semiconductor hardware entity, is very capital intensive compared to the other institutes, with a more than $10 billion semiconductor fabrication facility at the SUNY Polytechnic Institute in Albany, New York, and a more than $100 million

AIM Photonics Test, Assembly, and Packaging facility in Rochester. Accordingly, its operational budget is also sizeable.

DoD, as the primary federal partner in these public–private partnerships, assigned responsibility for standing up and overseeing the operation of the institutes to the Director of DoD ManTech in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). In recognition that technological innovation and leadership in manufacturing are essential to maintaining military technical advantage, DoD established a budget line for the manufacturing innovation institutes18 to provide for DoD’s initial and continued share of institute start-up and core funding. This budget is executed through agreements with the institutes managed by Army, Navy, and Air Force organizations, with the OSD ManTech office serving as the overall DoD coordinator and focal point for DoD’s role in co-investing with industry.

DOD MANUFACTURING USA STRATEGY

A core principle of the DoD strategy is combat overmatch. The department supports this principle through the continuous pursuit of innovation and of next-generation defense systems and concepts to deter and prevail in conflict. To effectively mature and transition DoD science and technology advances into production, DoD must have access to a robust and responsive U.S. industrial base, which is equipped with advanced manufacturing technologies that deliver critical products and systems affordably and rapidly.

This requires strong collaboration across DoD’s $12 billion science and technology portfolio with an emphasis on concurrent development of the new manufacturing technologies that will enable transition of science and technology advances.

To better support these requirements, DoD has established its eight Manufacturing USA innovation institutes through its DMS&T program element within the ManTech program. The mission of the eight DoD established institutes addresses both commercial and defense manufacturing needs within specific, defense-relevant technology areas and receives active participation and support from the military departments and defense agencies. The OSD ManTech office provides oversight of the DoD institutes.

The institutes are considered by DoD to be crucial and game-changing catalysts

___________________

18 Defense-wide Manufacturing Science and Technology Program, Program Element PE 0603680D8Z, Project 350: Manufacturing Innovation Institutes.

that bring together innovative ecosystems in various technology and market sectors in the United States, enabling their vibrancy and robustness.19

As such, the DoD Manufacturing USA institutes are industry-led, with dual public–private benefit, carrying large commercial market potential while meeting key U.S. defense industrial preparedness and operational needs.

The department’s commitment of more than $600 million in start-up funding for these eight institutes demands a coherent and effective strategy to guide their establishment and sustainment and, ultimately, to ensure their value to DoD and the nation. DoD has set five strategic goals20 for its Manufacturing USA institutes:

- Goal 1: Drive impactful advanced manufacturing R&D.

- Goal 2: Encourage the creation of viable and sustainable institute business plans.

- Goal 3: Maintain an optimal program design to maximize value delivery.

- Goal 4: Maximize stakeholder understanding of DoD’s Manufacturing USA institutes.

- Goal 5: Effectively support a capable workforce.

Furthermore, as the institutes continue to progress through their initial federal assistance agreement periods, DoD has committed to assess its changing roles and responsibilities and adjust the strategy accordingly.

DESIGN OF THIS STUDY

To meet the timeline required for this fast-track study of DoD’s Manufacturing USA institutes and DoD’s long-term engagement strategy for its current and future institutes, the study was designed to cover the following five major elements of the statement of task, which describes the workshop to be conducted21 in addition to the consensus recommendations (Appendix A):

- Focus on the business models used to stand up and operate, on a long-term basis, the eight DoD institutes;

- Evaluate lessons learned in developing and implementing the public–private partnerships adopted in those institutes and what changes may be needed;

- Evaluate the potential values and costs that would accrue to DoD from

___________________

19 See Department of Defense (DoD), 2017, Department of Defense Manufacturing USA Strategy, Version Date September 8, Director DoD Manufacturing Technology Program, OUSD(R&E) Strategic Technology Protection and Exploitation.

20 Ibid.

21 A separate workshop proceedings prepared by a designated rapporteur will also be released.

-

further long-term engagement with the institutes under various scenarios and funding structures;

- Receive input regarding similar public–private partnerships developed in other countries; and

- Identify topics to be addressed in a follow-on Phase II study.

Central to the study approach was to identify five key stakeholder groups to include in the gathering of findings: the eight DoD institutes, other DoD stakeholders, industry, academia, and other organizations. That last category of stakeholders included other federal government departments and agencies, technical professional associations, and regional stakeholders for the institutes.

Data-gathering methods consisted of (1) attendance and notetaking at the Defense Manufacturing Conference (DMC) in Nashville, Tennessee, on December 4-6, 2018; (2) 22 face-to-face individual stakeholder interviews conducted at the DMC; (3) four phone interviews; (4) stakeholder questionnaires using tailored study committee working papers; and (5) a 2-day committee-organized workshop held on January 28-29, 2019. Interviewees at the DMC were comprised of a cross-section of representatives from the five stakeholder groups identified above. Responses to the stakeholder questionnaires were subsequently discussed by a stakeholder group in an open session of the study committee meeting of January 30, 2019. The institute questionnaires also captured the business models used to establish and operate the institutes, as summarized earlier in this chapter. The study committee’s observations contained in Chapter 2, “Lessons Learned and Operating Changes to Consider,” were derived from the information obtained from all of the data-gathering methods.

To prepare for the workshop, more than 220 “save the date” emails were sent to known active stakeholders within the stakeholder groups, including names provided by the eight DoD institutes. A total of 166 individuals, including the 10 study committee members, registered for the workshop. Actual attendees totaled 145, including 37 representatives from other DoD stakeholders, 19 from DoD institutes, 26 from industry, 23 from academia, and 30 from other organization stakeholders.

Data gathering at the workshop consisted of two panel discussions, three breakout working sessions with general session report-outs for each, and a general session to collect follow-on study topics from the assembled stakeholders. The panel topics were “Alternate Public–Private Partnership Models” and “International Programs in Advanced Manufacturing,” which are summarized in Chapter 3.

For breakouts I and II, the workshop participants met in separate conference rooms assigned to each stakeholder group (DoD, institutes, industry, academia, and other organizations). Breakout I focused on a list of 20 generic institutes’ offerings compiled by the study committee (see Table 2.1 and Appendix B), with each stakeholder group independently assessing each offering’s high, medium, or

low value and cost impact. The cost impact was defined as the relative difference in cost to obtain the offering by participating in an institute versus the cost to obtain the offering without the benefit of an institute. Input was also collected regarding whether an offering’s benefit was to create new value or to eliminate or reduce a barrier. Each stakeholder group then populated a value-versus-cost impact map for each offering based on their group’s perspective. Chapter 2 includes a summary of the value proposition findings.

Breakout II continued the stakeholder groups’ evaluation of the DoD institutes’ lessons learned from their individual perspectives, beginning with assessments of the institutes’ perceived strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. The five stakeholder groups then provided lessons-learned findings for each of the 20 generic institutes’ offerings, identifying their perceptions of what the institutes should keep doing, stop doing, and start doing for each offering. Chapter 2 summarizes those findings by stakeholder group, with additional details in Appendix C.

The focus for breakout III shifted to DoD’s long-term engagement strategy for its Manufacturing USA institutes, with an assessment of the five goals in the current DoD Manufacturing USA Strategy.22 For this process, the members of the five homogenous stakeholder groups were dispersed into five breakout rooms, resulting in a heterogeneous mix of stakeholders in each room. Using a decomposition of each of DoD’s strategic goals on preprinted posters, the mixed stakeholder groups identified their perceptions of what DoD should keep doing, stop doing, and start doing for each decomposed goal. The potential improvements identified for each goal are summarized in Appendix D.

Immediately following the workshop, the study committee met in closed session for 2.5 days to discuss the findings from all sources and generate the committee’s recommendations contained in Chapter 5, “Committee Findings and Recommendations.”

___________________

22 DoD, 2017, Department of Defense Manufacturing USA Strategy.