4

International Implications, National Security, and Vulnerability Disclosure

Steven Lipner, SAFECode and member of the forum, moderated the third panel, which concerned the complicated global landscape around vulnerability discovery and disclosure, including current and future challenges.

Lipner led the security response team at Microsoft for several years. In the past, he said, the process for discovering and addressing vulnerabilities was fairly standard: a researcher found a vulnerability and reported it to the vendor, who then created a fix, released it, and hoped that it was successful. Under that process, the vulnerability becomes known when the patch is released, and attackers will try to exploit it between when the patch is released and when the fix is deployed by users. The process is less effective if users fail to deploy the patch or if vendors do not learn of the vulnerability until it is already being exploited, but for the most part, he said, the process worked.

Today, Lipner observed, disclosure is much more complicated. Vulnerabilities can be too difficult or too costly to patch, particularly if they are in the hardware or firmware. Multiple vendors may be implicated in the vulnerabilities, and different components can be affected in different ways that require different fixes. Spectre

and Meltdown are especially problematic, he said, because they encompass not just one but all of these ugly scenarios.

ARI SCHWARTZ

Center for Cybersecurity Policy and Law, Venable LLP

Ari Schwartz spoke about the center’s efforts to improve coordination around hardware vulnerability disclosure—in particular, for scenarios involving multiple vendors.

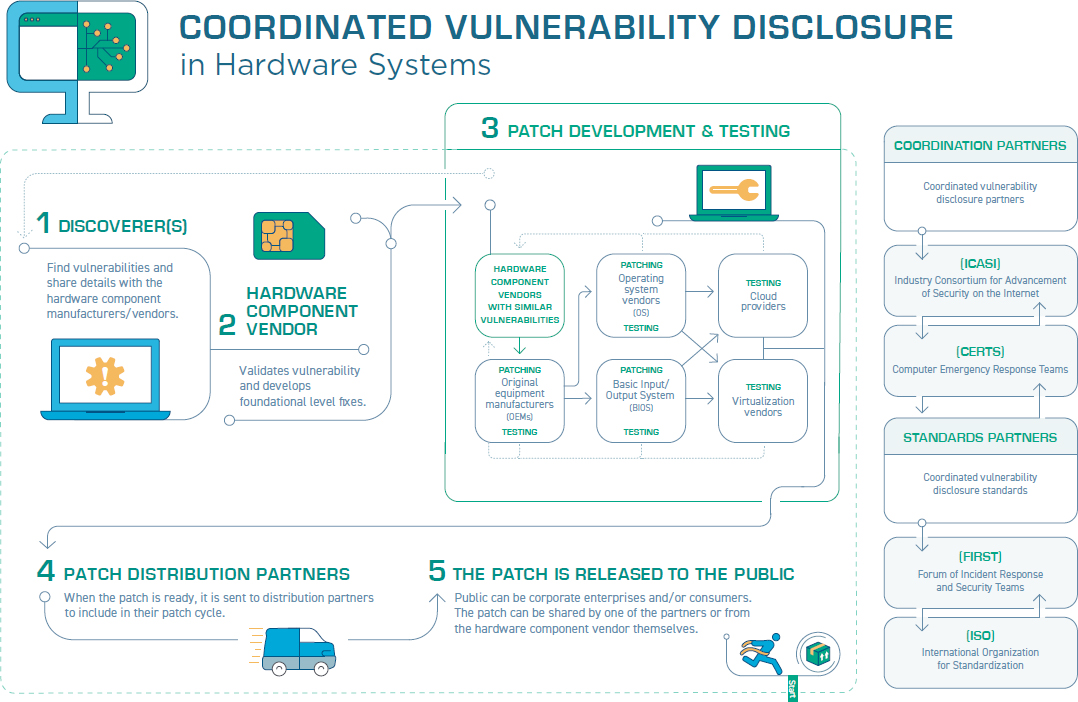

Multiparty disclosures can become quite complicated, Schwartz said, and it is important to remember two key goals throughout the process: (1) patch the vulnerability as quickly as possible and (2) coordinate and communicate with the discoverer. To summarize the process of a multivendor disclosure, Schwartz offered an illustration depicting a coordinated disclosure in five steps (see Figure 4.1).

First, the vulnerability is discovered and shared with the hardware component vendor. Then the vendor validates the vulnerability. Next the vendor works to create a patch and test it. Then the patch is sent to its distribution partners. Last, it is released to the public. This process was particularly complex with Spectre, Schwartz noted, because there were multiple variants requiring multiple patches, and there is still the possibility of discovering more.

There is not consensus with regard to what role governments should play in the disclosure process, Schwartz explained, and there are multiple issues to consider in this respect. For example, if one government is notified, should other governments where the vendor does business be notified as well? If a foreign company is notified, will its government find out too? Depending on governing style, different countries are likely to have differing levels of involvement. If computer emergency readiness teams (CERTs) are notified, will other government agencies be informed? Last, what can governments do if there is no patch or mitigation available? Governments may be able to ease the coordination, or they may get in the way of an already complex process.

It is possible to learn and improve on the ad hoc response to Spectre so that future vulnerabilities are handled faster and better.

Because every vulnerability is different, the disclosure process will be different too, but the response can still be improved every time so that the process is less ad hoc and more streamlined, Schwartz argued. Schwartz offered short- and long-term goals for creating a successful disclosure process. One key goal is to create a set of criteria for who gets notified and when, so that a fair system is set before a crisis occurs. It is also important to use nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) for both discoverers and manufacturers and to minimize the number of entities that know about a vulnerability until a patch is ready (while recognizing that business relationships and research priorities often must be taken into account).

Another important consideration, Schwartz argued, is for the organizations involved to identify a lead that can coordinate the response to certain vulnerabilities, initiate and maintain NDAs between industry members and partners, and help guide disclosure activities. There are some existing entities that could potentially take on this role for the semiconductor industry, including the Industry Consortium for the Advancement of Security on the Internet (ICASI) and the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), he said, or a new organization could be created to oversee the process in full. In addition, it is important that NDAs include language about consequences for participants that break the embargo and what the government’s role should be, if any.

Schwartz noted that while getting the patch to the public is the last step in the disclosure process, in some ways it is also another beginning. It is vital to improve the uptake of patches as they are deployed. This will require increased public awareness and a sense of urgency among users, he argued. Additionally, Schwartz emphasized that to develop smart laws in this space, the field must do a better job of detailing vulnerabilities and mitigations to policy makers, who cannot be expected to be cybersecurity experts.

KATIE MOUSSOURIS

Luta Security

Katie Moussouris is a security specialist who has worked as a “hacker for hire” to help companies identify vulnerabilities. She spoke about the strengths and weaknesses of “bug bounties” (an approach that focuses on finding problems after the fact) and related approaches to identifying security vulnerabilities.

Although hackers may sometimes have a bad reputation, Moussouris noted that many have long been motivated by a desire to make the world better, seeking to increase security by exposing areas of fragility. Bug bounties seek to harness this motivation by incentivizing hackers to find and report vulnerabilities. Although bug bounties and the hackers-for-hire ecosystem have expanded over the years, the approach has important downsides.

One key downside, Moussouris said, is that bug bounties can divert companies’ attention and resources away from measures to prevent vulnerabilities in the first place. In Moussouris’s view, investing more in prevention, such as by building security into the lowest-level architecture and creating a pipeline for skilled security engineers, would ultimately yield a better payoff in terms of security.

Bug bounties, Moussouris explained, are fundamentally different from penetration tests—authorized attacks on a system to discover weaknesses. Bug bounties are crowdsourced, following the theory that many eyes will spot more problems, but in reality few people are capable of finding the subtle or multilayer bugs that can cause the biggest problems or be most difficult to fix. Those with that level of skill should not be working as bug hunters, Moussouris argued; instead, companies should be hiring them as employees. Bug bounties, she emphasized, are not a replacement for penetration testing.

Bug bounties can also create complicated trust dynamics between companies and bug hunters. They are typically run as competitions and often require bug hunters to sign NDAs. This complicates the incentives for bug hunters, who, if successful, cannot publicly announce their victory and use the experience to advance their careers. For their part, Moussouris noted, a company’s own

security researchers do not always have a high level of trust that bug hunters’ motivations are in fact aligned with those of the company.

Another problem Moussouris discussed is scale. Companies often are not prepared to handle the onslaught of bugs that are found. Even apart from bug bounties, many large technology companies receive 150,000-200,000 bug reports each year. Efforts to automate bug hunting, like the DARPA Grand Cyber Challenge, which aimed to find 10,000 vulnerabilities via artificial intelligence methods, are likely to further compound this problem, she said. The sheer scale of security problems creates challenges for bug hunters and employees alike. It is important, she argued, to create strong supports for workers who will be handing the reports and fixing the bugs; these jobs are often very stressful and have a high burnout rate. Although many companies are aware of and focused on the need for improving processes to prioritize and address bugs, there remains an unmet need for such coordination in the context of bug bounties.

Moussouris pointed to two standards that address vulnerability disclosure: ISO/IEC 29147 and ISO/IEC 30111. The first maps out what to do when a vulnerability notification is received, and the second covers how to process and triage it. However, it takes more than engineering to resolve bugs that emerge through bug bounties; it is also necessary to engage with the hacker community and follow proper disclosure practices. If a company does not have the resources to address the bug reports, bug hunters will feel ignored and may lose their motivation to participate. In short, she argued, a bug bounty program needs adequate internal resources to succeed.

Some bugs are simple, while others are incredibly complex. Moussouris suggested that a taxonomy could be useful to inform how to tackle different classes of bugs, and that processes for identifying bugs should be designed with the awareness that there are not a lot of people in the world who can find or fix the highest class of bugs.

Last, Moussouris argued, it is important for companies to understand bug hunters’ motivations, the kinds of bugs they are targeting, and the black market for those bugs. Companies must avoid getting into a bidding war with black market players willing to pay for information about vulnerabilities, creating opportunities for employees

to collude with outsiders, or creating perverse incentives that cause good employees to quit and make more money as bug hunters.

In the discussion, Bob Blakley, Citigroup, asked Moussouris to expand on what separates effective from incompetent bug bounty programs. Noting that companies have mixed motivations for starting bug bounty programs, she emphasized that they should not be used to find “low-hanging fruit”—when that happens, it is an indication that a company has failed to do its own due diligence. Bug bounties, she argued, ideally should find only the more complicated or severe bugs.

AUDREY L. PLONK

Intel Corporation

Audrey Plonk spoke about Intel’s five-step coordinated vulnerability disclosure process and how it has been refined in the wake of Spectre.

In Phase 0, Intel’s internal security experts receive a vulnerability report and validate it by re-creating the situation in Intel’s own environment. The report could be from a researcher, from an internal source, or from a bug bounty program. Once the vulnerability is determined to be real, the next step is to determine how serious it is and the level of resources required to fix it.

Phase 1 is the architectural assessment. Using what is learned in Phase 0, security personnel determine how and with whom a mitigation can be crafted. The mitigation could be in the microcode, a software update, or, in the case of Spectre, operating system patches until the more critical hardware changes can be made. At this stage, Plonk explained, Intel assembles a small group of key partners under NDAs who can help understand and define the best path to patching, fixing, or mitigation.

Phase 2 is mitigation development. This phase includes additional partners—for example, software, virtual machine, hardware, and operating system vendors. Working with these partners under NDA, Intel develops, tests, and debugs the mitigation code. Adequately pretesting the mitigation before deployment is vital to ensuring that it will work, Plonk said.

In Phase 3, the mitigation is ready to be deployed under NDA to a broader network of customers for testing and validation. In this phase, Plonk explained, Intel issues the patches to their original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), who test it, recompile their devices, and issue new versions of firmware. This involves a large set of companies, many of whom must make firmware with the updated microcode, which can be challenging because firmware is harder to update than operating systems. OEMs often must test and validate many variations of the patches on many different devices.

Once the firmware patches are ready to go, it is time for Phase 4: public disclosure. Plonk agreed with Schwartz: disclosure looks like the last step, but in many ways it is also the first step in a much larger process.

Plonk noted that every time Intel goes through this process, it is further refined both to work better and to stay up to date with standard industry practices and vulnerability disclosure guidelines. She added that Intel has also made a few internal changes since Spectre’s public disclosure. These include the creation of the Security First pledge, which emphasizes customer-focused, transparent, and timely communication, as well as a realignment of resources to improve attention to customer issues.

Intel is also working to create a patching cadence, hoping to create a systemized, quarterly microcode push to vendors and customers. As it gets closer to that timeline, Plonk noted that customers have appreciated the increased predictability, which makes it easier for them to test and deploy updates. The company is also working with Microsoft on making Intel’s firmware patches operating system–loadable, which would allow patches to be pushed through operating system updates instead of new firmware.

Last, Plonk noted that Intel enhanced its bug bounty program after Spectre. This enhancement includes a greater emphasis on

finding side-channel attacks and involving a larger community to get more eyes on such problems.

PAUL WALLER

U.K. National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC)

Paul Waller shared his perspective of the government’s role in vulnerability disclosure and response. With a mission to make the U.K. the safest place to live and work online, NCSC is a government agency that performs technical research and works with academia and industry to improve security for government services, businesses, charities, and citizens.

Waller noted that thousands of vulnerabilities are discovered every year, with varying levels of severity. He reiterated Schwartz’s point that security researchers must actively work to help policy makers understand the problem so that practical solutions can be crafted. It can be a delicate balance: it is important to raise user awareness but not create panic. Most of the time, Waller said, the best course of action for users is to simply wait for the patch and implement it when available. From a government perspective, he said, the global marketplace adds further complications because variation between countries impedes global scaling of vulnerability disclosure processes and solutions.

As a government agency, NCSC’s role is somewhat unique. Although it can discover and disclose bugs, NCSC does not develop, test, or deploy the patches, Waller explained. Its role is more as impartial observer, which can include efforts to convene or coordinate responses, along with providing transparency on how companies are handling bugs. Waller said that NCSC is also working to increase incentives for responsible security practices—for example, by encouraging vendors to push patches and make them easier to find, as opposed to merely making them available.

Although automation may eventually help improve security, the technology is not yet there, Waller said. More important in the near term is to reduce the harm to users by solving problems at the root cause. Although mitigations to add security to the upper layers

is helpful, truly addressing the root cause will sometimes require changes to the hardware, he said. Toward this end, Waller pointed to promising research from Cambridge University around a new hardware architecture called Capability Hardware Enhanced RISC Instructions (CHERI) that provides memory safety and integrity and has marketplace potential.

Waller argued that designers must place less of the burden of security on the user—for example, by eliminating the reliance on complex passwords that merely make things harder for the user. In addition, he argued that every software developer cannot be expected to be a security expert. Instead, he said, the field should create security expectations that can scale, find a way to measure how they are being employed, and direct scrutiny and assistance to where it is needed most.

One important development Waller discussed is the recently drafted Code of Practice for Consumer IoT Security, a set of 14 voluntary guidelines that Internet of Things (IoT) device developers can follow to improve device safety.1 The code of practice recommends, for example, eliminating default passwords, clearly and publicly describing responsive vulnerability reporting procedures, and communicating a timeline for how long a product will be supported so that consumers can make informed choices. Waller noted that the guidelines share many commonalities with other codes of practice, including Microsoft’s seven principles as presented by Galen Hunt earlier in the workshop. This was done intentionally, he said, so that compliance with one set of guidelines can promote compliance with others and make compliance easier for the manufacturer.

As demonstrated in this workshop and another similar one held in the U.K. in response to Spectre, Waller said that the level of cooperation among competitors has been crucial to advancing a collaborative effort to solve an incredibly complex problem. In closing, he urged participants to keep up the momentum and drill down on how government and industry can work together to better

___________________

1 See United Kingdom Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, 2019, “Secure by Design: The Government’s Code of Practice for Consumer Internet of Things (IoT) Security for Manufacturers, with Guidance for Consumers for Smart Devices at Home,” February 28, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/secure-by-design/code-of-practice-for-consumer-iot-security.

anticipate and respond to the vulnerabilities and attacks that are yet to come. Metrics to assess and reward good security behavior can work if they are simple and well targeted, and they can be more effective than rules for improving security, he noted. It is also valuable to encourage transparency throughout these processes to drive better security behavior, he argued.

DISCUSSION

The panel concluded with a wide-ranging discussion of how to enforce a vulnerability disclosure plan, the role of governments and other authorities, the complexities of collaboration, the need to work with non-experts, and other facets of the workshop’s themes.

Mechanisms for Enforcing Vulnerability Disclosure

Fred Schneider, Cornell University, asked the panel to expand upon what it takes for a vulnerability disclosure plan to be implemented and for a recognized authority to enforce it.

Schwartz replied that while the Center for Cybersecurity Policy and Law is issuing a report with a recommended disclosure plan, no existing body is poised to serve as an enforcer. Trade associations have some authority in this space, he said, although most are hesitant to assume the responsibility because they lack security expertise. In particular, ICASI could potentially serve in this role. However, although ICASI includes all the largest companies, it does not represent the industry as a whole, and it would be important to develop a mechanism to reach smaller companies. Schwartz added that creating a new organization is also a possibility, although how such an organization would establish its authority is as yet unknown.

Schneider suggested that laws could be used to mandate that companies follow certain disclosure procedures. Schwartz agreed that this could be an option, although he suggested it may be better for a process to start as voluntary, become the accepted standard, and then be made law. Given that every vulnerability is different, the typical one-size-fits-all nature of laws can be problematic in this space.

Waller pointed out that laws passed in one country would affect other countries, too. As an example, Schneider pointed to the General Data Protection Regulation, which addresses privacy for European Union citizens but also covers the export of personal data outside the European Union. Although it is not a U.S. law, it is nonetheless having a major impact for U.S. technology companies.

Building on the discussion, Plonk expressed doubt that a coordinated, multiparty vulnerability disclosure would be improved by the involvement of a third party, such as governments or other authorities. Experience has shown that it is important to fix vulnerabilities as quickly as possible, and existing business relationships create sufficient incentives for companies to work together as needed to do so, she said. Adding more people to the small group that is capable of solving the problem can bring additional challenges and slow down the process. Even in very complicated cases like Spectre and Meltdown, she observed, outside help is not necessarily useful and can actually impede the process if outsiders do not have the expertise to handle the complexities of creating and testing patches.

Waller pointed to the current ISO/IEC standards 29147 and 30111, which have influenced industry behavior with regard to coordinated vulnerability disclosure. One example of a good practice is that the vulnerability must be first disclosed to the vendor; NCSC, he said, does not collect disclosures unless they pertain to government agencies’ web services or unless a vendor has been notified but has not responded. Building on this, Schwartz emphasized that under any disclosure plan, it would be vital to notify vendors before governments—an approach that is not only more likely to result in a faster, better response, but is also less likely to put vendors on the defensive.

Moussouris agreed, noting that government agencies do not have the capacity to be the first responders when vulnerabilities are discovered. They can coordinate or assist when needed, such as if the

vendor is unresponsive or if there is a national security emergency, but otherwise they should not be the first point of contact, she argued. It is possible to create an organization that would take on this role, or it may be assumed that ad hoc coalitions would spring up to address problems, but she suggested that a centralized government authority is not the answer.

Eric Grosse, independent consultant, posited that governments, based on their intelligence activities, may in some cases have more insight on attacks than companies or researchers do. If companies knew the government would notify them when vulnerabilities are discovered through these activities, he suggested, companies might be more willing to disclose their own knowledge to the government. If the government does have such knowledge, Schwartz said, disclosure can be in the interest of both the company and the government. Waller stated that his agency had done that in the past for certain situations. Participants agreed that if governments want to get involved in companies’ vulnerability disclosure processes, they will need to be able to demonstrate that they can bring value.

Expectations Versus Reality in Vendor Response

Paul Kocher, independent researcher, noted that reporting problems to the vendor first is not necessarily the best move in every case. What if the vendor simply sits on the information without acting to address it? We assume that big companies will take these reports seriously, but will smaller ones, like individual device manufacturers? Kocher reminded participants that if a researcher has signed an NDA, reporting the bug to anyone else can lead to a lawsuit. In the case of Spectre, Kocher reached out to multiple manufacturers. Despite some awkwardness, he argued that doing so eventually led to better communication between the involved companies.

Asked to elaborate, Kocher said that conversations with engineers about their countermeasure attempts yielded the most constructive outcomes. Hardware manufacturers may not have a clearly spelled out responsibility to their competitors, but exchanges between manufacturers and researchers can be helpful in pooling knowledge. Kocher added that he had a positive experience with Intel, but other, less experienced vendors did not engage as constructively.

Plonk stated that the companies really did work together closely for months to respond to Spectre. Although different companies will respond differently, especially if they are not as technically sophisticated, she emphasized that Intel values feedback on its vulnerability responses. Overall, she suggested that there needs to be a bigger push to encourage vendors to be open to receiving outside information and responding appropriately, whether that push comes through legislation or other means.

Moussouris pointed out that not all organizations have the capacity to plan for high-level attacks, and most have a fundamental misunderstanding of what is required to protect themselves. They may have a process to resolve bugs that they think is adequate, but she said that many are not anywhere near the level of sophistication required to do complex multiparty vulnerability coordination with this sort of vulnerability.

When Embargoes Are Broken

Participants next delved into the responsibilities of parties that become involved in an embargo and what happens when embargoes are broken.

Grosse asked if there are typically actions taken against those who break an embargo. Are they sued? Are they excluded from future disclosure processes? Are there other types of consequences? Schwartz said that loss of reputation is generally an effective deterrent, suggesting that excluding an untrustworthy party from future disclosures would be the most likely response. Suing, he said, would make sense only if someone had broken embargoes multiple times and you could prove a pattern of practice.

Grosse wondered if once a government agency was informed of a vulnerability, it would be compelled to share the knowledge with other government bodies, effectively breaking an embargo? Schwartz responded that most departments do not share information readily, despite a policy in place saying that they should, and that disconnect creates a lack of transparency. Grosse agreed that a lack of transparency from the government is a problem, especially in situations like Spectre, in which knowing whom to trust is very difficult and leaks occur. Taking

legal action seems extreme, he said, but at least when the courts are involved, there is a system of due process.

Plonk added that Intel would need to see compelling evidence that a leak occurred, and if someone was forthright and admitted leaking, Intel would attempt to understand why and put measures in place to avoid similar situations in the future. Kocher remarked that in the context of Spectre, he was not bound by any NDA and thus was free to alert his colleagues in the community. Waller pointed out that in the end, the parties involved largely collaborated effectively, despite lacking a clear process or structure. Moussouris noted that embargo breakers do not necessarily have nefarious motives. These situations are all very nuanced and there could be a good reason for breaking embargo, such as knowledge of an attack that is actively hurting customers. In such a case, Microsoft, for example, would in some cases release technical details of the vulnerability even before the patch was available. Other companies have different triggers that balance secrecy with risks to customers, she said.

Plonk agreed that evidence of an active exploitation usually means that a company will publicly disclose the vulnerability before full mitigation is possible, because there could be temporary fixes that would better protect customers in the meantime. On the other hand, Moussouris noted that customers sometimes ignore initial mitigation measures in favor of waiting for patches to be fully ready, which can save costs but leave them vulnerable.

Waller agreed that evidence of active exploitation can be a game changer for the vulnerability disclosure process, adding that such factors can complicate the creation of set rules because so many decisions are situation-based. Moussouris agreed, noting that at Microsoft there were times when the company followed different processes for various situations because of the unique mix of problems, risks, and mitigations involved.

Tadayoshi Kohno, University of Washington, asked if companies were considering improving detection mechanisms for vulnerabilities that leak before a patch is ready. Waller answered that NCSC already works to advance such detection. Schwartz added that it would be important to make sure the detection mechanism does not open up new vulnerabilities.

Working with Non-Experts

A participant asked the panel to expand on the need to communicate effectively about vulnerabilities with non-experts, a theme that emerged throughout the workshop.

Schwartz noted that starting with basic definitions is critical so that there is a common understanding of the most basic aspects. Plonk agreed and said that security experts could do more to disseminate basic information about the computing ecosystem. Certain companies or researchers are involved because of the technical necessities the process requires. Particularly in the United States, Plonk suggested that getting more computer scientists involved in government, such as through a technical fellows program or other system-level change, would likely educate lawmakers better than the current system, in which industry leaders must constantly come to Washington to explain the latest crisis.

Waller, as a technical expert who works for the government, said scientists need to be trained to talk with lawmakers, which takes a lot of practice but is worth learning. Doing this effectively, he said, requires putting yourself in the shoes of the non-expert, avoiding jargon, and figuring out what motivates the person with whom you are communicating. Those skills can help scientists deliver their messages in a way that explains the basic concepts and puts the bottom-line effects into context.

Moussouris agreed that technical understanding and policy understanding are very different and that it takes work to bridge the two. She argued that it is important to remember that we all have things to learn from other people, and if we refuse to learn them, we will not be able to collaborate to solve problems. For example, when she worked on a committee that wrote ISO standards, she had to work hard to understand the perspective of the policy makers. She noted that creating effective standards takes both technical expertise and diplomacy because of all the different people and countries that must buy in to make the standards successful.