Proceedings of a Workshop

INTRODUCTION1

The United States is facing an opioid use disorder epidemic, with opioid overdoses killing more than 47,000 people in 2017 (NASEM, 2019). The past three decades have witnessed a significant increase in the prescribing of opioids for pain, based on the belief that patients were being undertreated for their pain coupled with a widespread misunderstanding of the addictive properties of opioids. This increase in prescribing of opioids also saw a parallel increase in addiction and overdose. The 2000s saw a wave of overdose deaths driven by the increased use of illegal drugs such as heroin. Currently, the nation is in the midst of another wave of overdose deaths due to the increased use of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl (CDC, 2018). In an effort to address this ongoing epidemic of opioid misuse, policy and regulatory changes have been enacted that have served to limit the availability of prescription opioids for pain management.

Overlooked amid the intense focus on efforts to end the opioid use disorder epidemic is the perspective of clinicians who are experiencing a

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

significant amount of daily tension as opioid regulations and restrictions have limited their ability to treat the pain of their patients facing serious illness. Increased public and clinician scrutiny of opioid use has resulted in patients with serious illness facing stigma and other challenges when filling prescriptions for their pain medications or obtaining the prescription in the first place. Thus, clinicians, patients, and their families are caught between the responses to the opioid use disorder epidemic and the need to manage pain related to serious illness.

The Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine sponsored a workshop on November 29, 2018, to examine these unintended consequences of the responses to the opioid use disorder epidemic for patients, families, communities, and clinicians, and to consider potential policy opportunities to address them. The workshop, Pain Management for People with Serious Illness in the Context of the Opioid Use Disorder Epidemic, unfolded over five sessions.

- The opening session provided context with an overview of the scope and severity of the opioid use disorder epidemic.

- The second session focused on how responses to the epidemic affect the ability of people with serious illness to access opioid medications for pain. Workshop speakers shared clinicians’ perspectives on their ability to effectively treat their patients’ pain, discussed disparities in access to pain medications, and discussed issues related to pain management for seriously ill infants and children.

- Pain management needs of those with comorbid substance use disorder and serious illness were examined in the workshop’s third session.

- The workshop’s fourth session focused on policy and regulatory responses to the opioid use disorder epidemic, including federal and state regulatory policy, as well as payment policy. Speakers in the fourth session discussed measures that have been developed and implemented to address the opioid use disorder epidemic and whether those measures have been sufficiently flexible to limit unintended consequences for those with serious illness. Policies to expand access to non-opioids for pain management were also examined, as were associated coverage and reimbursement policies.

- The final session of the workshop aimed to identify actionable next steps by focusing on areas such as improving professional medical

education to better prepare clinicians to treat and manage pain and addiction, enhancing the development of, and access to, alternatives to opioids, and expanding access to treatment for substance use disorder.

The Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness serves to convene stakeholders from government, academia, industry, professional associations, nonprofit advocacy groups, and philanthropies. Inspired by and expanding on the work of the Institute of Medicine (IOM)2 report Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life (IOM, 2015), the roundtable aims to foster ongoing dialogue about crucial policy and research issues to accelerate and sustain progress in care for people of all ages experiencing serious illness.

In his introduction to the workshop, James Tulsky, chair of the Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, said that when he moved to Massachusetts in 2015, it became clear that clinicians and members of Dana-Farber’s outpatient palliative care service were experiencing great angst over how to care for people suffering from pain related to their cancer in the context of the opioid use disorder epidemic. Massachusetts, he noted, has been hit particularly hard and was working to develop solutions to address the epidemic. In describing the increased difficulty clinicians faced in obtaining access to opioids for their patients as a result of heightened regulatory oversight of opioid prescribing, Tulsky observed: “They are trying to figure out a way to thread the needle.”

Andrew Dreyfus, president and chief executive officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, explained in his introductory remarks that caring for people with serious illness and opioid use disorder is a major concern for his organization. He pointed out that in 2012, his organization was one of the first in the nation to begin to focus on changing the culture of opioid prescribing by implementing a “comprehensive” opioid utilization program on opioid prescribing rates, which included formal agreements between patient and provider, a requirement for the payer’s approval prior to new opioid prescriptions and quantity limits.3 Some of the policies his

___________________

2 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM name is used to refer to publications issued prior to July 2015.

3 For more information, see https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6541a1.htm (accessed April 1, 2019).

organization developed have since been adopted by others and endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). At the same time, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts began looking holistically and more broadly at issues that served as barriers to treating opioid use disorder, such as cost sharing and administrative constraints. In addition to its commitment to combatting the opioid use disorder epidemic, the organization made a public commitment to focus on improving care for people with serious illness including offering more end-of-life benefits.4

Dreyfus noted that both of these health issues share many similarities: Patients with chronic pain and those with substance use disorder have suffered from being outside of the mainstream of medical treatment. Both illnesses are highly influenced by the social circumstances of patients and their families’ dynamics, as well as the emotional and behavioral health issues of patients and their families.

This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the presentations and discussions. The speakers, panelists, and workshop participants presented a broad range of views and ideas. Box 1 provides a summary of suggestions for potential actions from individual workshop participants. Appendix A contains the workshop’s Statement of Task and Appendix B contains the workshop agenda. The workshop’s speakers’ presentations (as PDF and audio files) have been archived online.5

___________________

4 For more information, see https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2015/12/27/bluecross-expands-benefits-for-end-life-care/5Uduttll3fG3ARVZkktP8I/story.html (accessed April 1, 2019).

5 For more information, see http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/HealthServices/QualityCareforSeriousIllnessRoundtable/2018-NOV-29.aspx (accessed January 18, 2019).

UNDERSTANDING THE OPIOID USE DISORDER EPIDEMIC AND ITS IMPACT ON PATIENTS, FAMILIES, AND COMMUNITIES

The workshop’s first session began with a video featuring Laura Martin, substance use prevention coordinator for the city of Quincy, Massachusetts. Martin shared the story of how her younger brother became addicted to opioids and later died from a heroin overdose in his childhood bedroom just days after being released from a self-committed, 30-day treatment facility and shortly before starting law school. Martin noted how the stigma attached to opioid use disorder inhibits individuals with the disorder and their families from seeking help. This stigma, she stressed, has had the effect of limiting the resources the nation has put into providing evidence-based treatment and support for those who suffer from an opioid use disorder. She also spoke about the multigenerational effect the opioid use disorder epidemic is having on families, as grandparents and even great-grandparents are left to care for their grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Following the video, Jane Liebschutz, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, provided a historical perspective on opioid prescribing and substance use disorders. She also reviewed the criteria for a diagnosis of opioid use disorder; examined the impact of the opioid use disorder epidemic; and briefly discussed treatment options for the disorder.

Liebschutz traced the roots of the current epidemic to the discovery made 200 years ago, when German pharmacist Friedrich Wilhelm Adam Sertürner isolated the molecule, which he named morphine, from poppy seeds and determined that 15 milligrams of morphine should be the standard dose for anesthesia, but not oversedation, and this dose is still used today. Liebschutz explained that morphine was first used to treat pain among wounded soldiers during the Civil War—the first time morphine was used for a large patient population.

In 1899, said Liebschutz, Bayer introduced heroin—a chemical derivative of morphine—as a new medication for chronic cough; by 1914, the addictive properties of medicinal opioids were recognized. As a result, the U.S. Congress passed the Harrison Act of 1914 (approved on December 17, 1914, and effective on March 1, 1915) that regulated non-medical opioid use and made possession of an opioid illegal without a prescription.

Liebschutz explained that a half-century later, in the 1960s and 1970s, heroin use was largely a problem of minority communities, inner cities, and

returning Vietnam veterans. In fact, to combat the high rates of opioid use disorder in Vietnam veterans, in 1972 the Nixon administration approved methadone as a treatment. At about the same time, there was a new sense within the medical community that patients with serious pain, particularly patients with cancer, were being undertreated with opioids. A 1973 study by Marks and Sachar found that despite being treated with narcotic analgesics for pain, 32 percent of medical inpatients continued to experience severe distress, and another 41 percent were in moderate distress. Liebschutz pointed out that in 1980, a letter was published in the New England Journal of Medicine claiming that those treated with narcotics rarely developed addiction. The letter suggested that those who were given opioids for pain would not develop addiction (Jick et al., 1970; Porter and Hick, 1980). “Many of us, including myself, really did think that for a long time,” said Liebschutz.

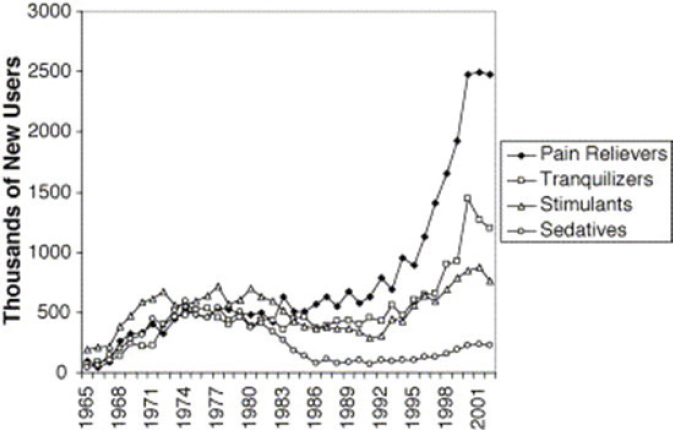

Based on the belief that patients in serious pain were undertreated and that opioids were not addictive, opioid prescribing soared in the early 1990s (see Figure 1). In 1996, Purdue Pharma developed OxyContin, a long-acting form of oxycodone, and marketed it as a painkiller with a lower potential for addiction. In 2001, the Joint Commission determined that

SOURCES: As presented by Jane Liebschutz, November 29, 2018; Compton and Volkow, 2006.

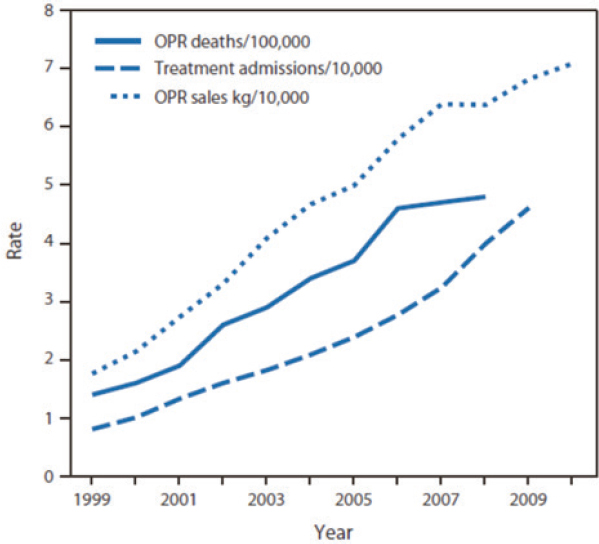

SOURCES: As presented by Jane Liebschutz, November 29, 2018; Paulozzi et al., 2011.

pain should be the fifth vital sign,6 and that hospitals and health care programs would be graded on how well they were treating their patients’ pain. However, “the parallel rise in opioid prescription also went along with the parallel increase in addiction and overdose,” Liebschutz explained (Paulozzi et al., 2011) (see Figure 2).

Liebschutz pointed out that addiction is a brain disease in which drugs “hijack” the brain’s natural dopamine-powered reward circuits (Volkow et al., 2016). According to Liebschutz, normally, these circuits become active when someone engages in joyful activities. Early in the use of addictive drugs, a person feels euphoric, and withdrawal produces a mild reduction in energy. A user looks forward with excitement to using the drug again. With time and further use, neuroadaptation,7 a learning process in which the

___________________

6 The other vital signs are blood pressure, pulse rate, rate of respiration, and temperature.

7 For more information, see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3870778 (accessed April 1, 2019) and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2886284 (accessed April 1, 2019).

brain reacts to a previously inexistent sensory input and its ability to adapt to it by ignoring it or using it properly (Alió and Pikkel, 2014), occurs. This process reduces the euphoria to merely feeling good when using the drug, and the mild reduction in energy due to withdrawal becomes reduced energy. Instead of looking forward to using, the individual starts to “really desire” the drug. As the neuroadaptation continues, the drug does not make the individual feel good, but merely helps them escape dysphoria, a state of unease or dissatisfaction with life. Depression, anxiety, and restlessness affect the individual when the drug is not present, and as a result, the individual starts obsessing over obtaining the drug. At the same time, a cognitive learning process occurs along with this neuroadaptation (Lewis, 2018).

Liebschutz reviewed the diagnostic criteria for opioid use disorder, as listed in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-V) (APA, 2013). Symptoms include

- Use in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended;

- Unsuccessful efforts to cut down/persistent use;

- A great deal of time spent getting, using, or recovering from use;

- Craving, or a strong desire to use;

- Recurrent use resulting in failure to fulfill major obligations at work, school, or home;

- Continued use despite social or interpersonal problems caused by use;

- Social, work, and/or recreational activities given up or reduced;

- Use in situations in which it is physically hazardous;

- Continued use despite physical or psychological harm;

- Withdrawal; and

- Tolerance.

Liebschutz particularly emphasized the last two criteria—tolerance and withdrawal—and noted that patients who take opioids as prescribed can have these particular symptoms of opioid use disorder without having the disorder. For example, patients with end-stage cancer can develop withdrawal and tolerance, but that does not mean they have a substance use disorder. Similarly, a baby whose mother had the disorder can exhibit withdrawal and tolerance, but does not have a substance use disorder. Patients must exhibit more symptoms that these two to be diagnosed with substance use disorder, explained Liebschutz.

Noting that the terms “substance abuse” and “opioid abuse” are no longer used, Liebschutz explained that the correct terminology is “mild,

moderate, or severe opioid use disorder,” depending on whether the patient displays two to three, four to five, or six or more of the above symptoms in 12 months, respectively.

Tracing the early period of the opioid use disorder epidemic, Liebschutz described the emergence of so-called “pill mills.” These are pharmacies affiliated with a physician who, for cash, would administer a minimal examination and prescribe an outsized number of pills, explained Liebschutz. She observed that those pharmacies were responsible for a significant amount of “opioids being diverted and also [for] feeding addiction that had developed during this period of time.” She explained that states responded by creating prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), which are state-based databases used to identify patients who “doctor shop” for multiple opioid prescriptions and clinicians who overprescribe. By 2018, all but one state had created such databases—the Missouri legislature has blocked the creation of a database there.8 Liebschutz explained that law enforcement has used these databases to aggressively pursue overprescribers and shutter nearly all pill mills.

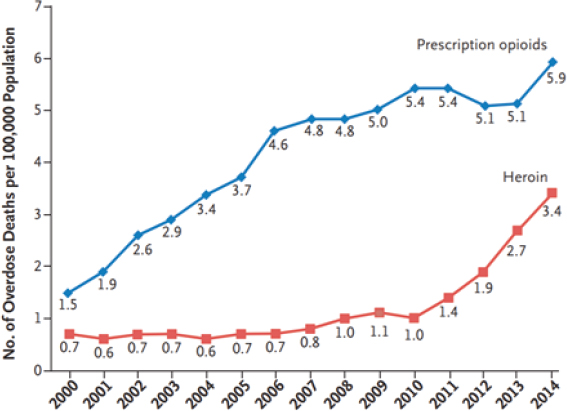

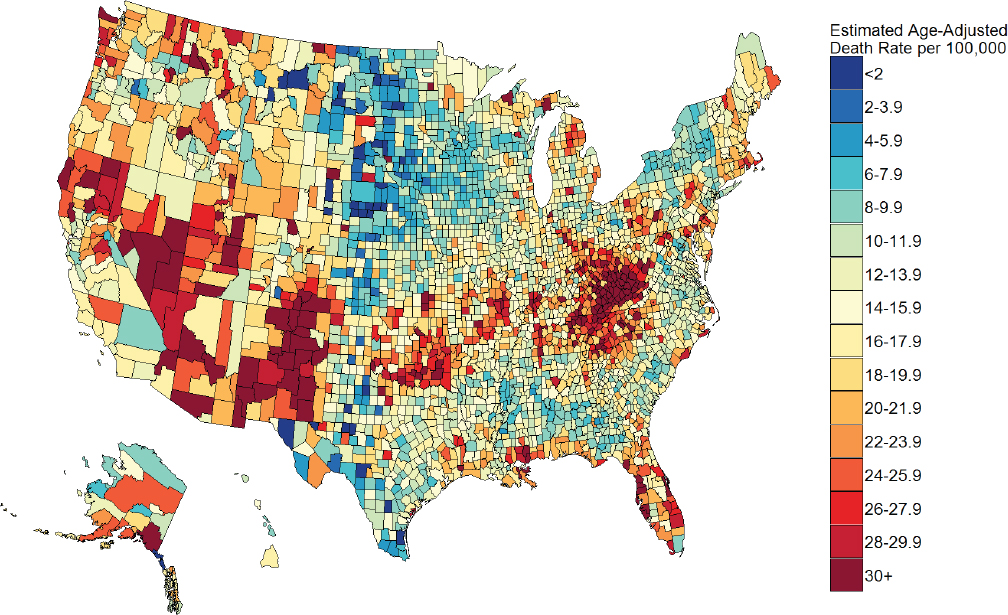

Liebschutz pointed out that while such overprescribing and relatively easy access to opioid painkillers created the first wave of the opioid use disorder epidemic, the second wave (see Figure 3) arose when Mexican drug cartels realized they could produce heroin and market it directly to suburban and rural White customers, bypassing the inner cities. She noted that in 2010, there was an inflection point in the number of heroin deaths while prescription opioid deaths started to level off. Liebschutz stated that this is not necessarily a one-to-one substitution of people switching from prescription opioids to heroin, but instead is an indication of “heroin in and of itself being a problem” said Liebschutz. Liebschutz further pointed out that in 2002, an estimated 400,000 Americans had used heroin in the previous year, but by 2016, the number had risen to nearly 1 million.

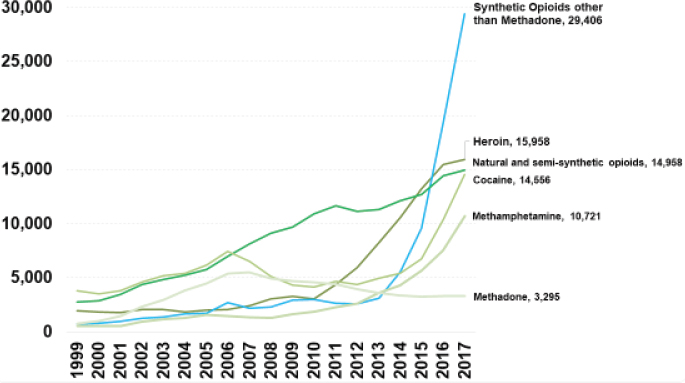

Liebschutz explained that the third wave of the opioid use disorder epidemic is currently sweeping the United States, driven by fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine. Largely manufactured in China, fentanyl is smuggled into the country in small quantities, making it difficult for law enforcement to interdict. Liebschutz explained that drug dealers mix fentanyl with heroin to increase the intensity of the high. Carfentanil, an

___________________

8 The workshop was held in November 2018; the Missouri House voted to approve a statewide PDMP on February 11, 2019 (Dabbs, 2019).

SOURCES: As presented by Jane Liebschutz, November 29, 2018; Compton et al., 2016.

elephant tranquilizer 10,000 times more potent than morphine, has been implicated in a number of deaths around the country, she added.

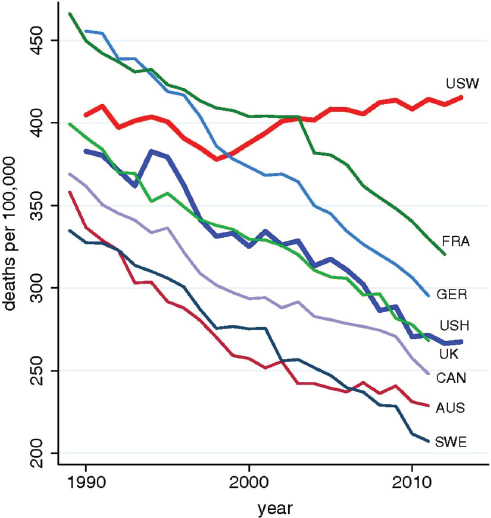

Drug overdoses killed more than 72,000 Americans in 2017 (see Figure 4), with the biggest increase over the past few years caused by fentanyl overdose. Liebschutz explained that because of fentanyl’s potency, people experimenting without knowing exactly what they are getting from their dealers have suffered unintentional overdoses that now dwarf all other causes. Perhaps the most astonishing outcome from the dramatic rise in overdose deaths is that the U.S. mortality curve is bending upward for U.S. non-Hispanic, middle-aged Whites (see Figure 5) for the first time in more than four decades (Case and Deaton, 2015). Notably, the mortality rate of U.S. Hispanics follows the trends of other countries. According to Case and Deaton, this rise in mortality among U.S. non-Hispanic Whites is due to what is referred to as the “deaths of despair”: overdose, alcoholism, and suicide (Case and Deaton, 2015).

As Liebschutz alluded to at the start of her presentation, the opioid use disorder epidemic is having a significant impact on families. In 2010, 5.4 million lived in a household headed by grandparents, up from 4.7 million in 2005 (Scommegna, 2012). The number of grandparents raising grand-

SOURCE: As presented by Jane Liebschutz, November 29, 2018.

NOTE: AUS = Australia; CAN = Canada; FRA = France; GER = Germany; SWE = Sweden; UK = United Kingdom; USH = U.S. Hispanics; USW = U.S. White non-Hispanics.

SOURCES: As presented by Jane Liebschutz, November 29, 2018; Case and Deaton, 2015.

children increased by 7 percent from 2009 to 2016, with 2.7 million grandparents raising grandchildren (Cancino, 2016). Liebschutz noted there are a number of support groups for parents affected by the opioid use disorder epidemic, including Learn to Cope9 and Parents of Addicted Loved Ones.10

Liebschutz pointed out that neonatal abstinence syndrome, now called neonatal withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), has risen in the United States from 1.19 per 1,000 live births in 2009 to 5.63 per 1,000 live births (Stover and Davis, 2015). NOWS is characterized by hyperactivity of the central and autonomic nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. Babies affected by NOWS do not meet the criteria of addiction according to the DSM-V (as described earlier) but are born with physical dependence. Not all babies of mothers who use opioids develop NOWS. The incidence of NOWS is higher in rural areas than in urban areas. As of 2015, in West Virginia—an epicenter of the opioid use disorder epidemic—some 50 babies out of 1,000 are born with this condition (Umer et al., 2018).

Turning to the issue of medications for opioid use disorder, Liebschutz pointed out that the three types of approved medications include full agonists (methadone and off-label morphine in the United States) that activate the opioid receptors, resulting in full opioid effect; partial agonists (buprenorphine, also called Suboxone) that activate the receptors to a lesser degree; and antagonists (naltrexone, also called Vivitrol) that block opioids by attaching to the receptors without activating them (NAABT, 2016). Naloxone, brand name Narcan, is a different type of medication that does not treat opioid use disorder but instead is a reversal agent used to treat overdoses.

Methadone is only dispensed by federally licensed facilities, usually in locations removed from populated areas, and requires dosing that is observed daily, although some patients receive take-home methadone after long periods of sobriety. A 30-day supply of buprenorphine can be given in any outpatient setting, and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) will issue a waiver after special training. Naltrexone can be given by any licensed prescriber without a waiver through an oral form daily or an injectable form every 4 weeks.

A meta-analysis of all-cause mortality during and after either methadone or buprenorphine treatment found that all-cause mortality for methadone treatment was 11.3 per 1,000 versus 36.1 per 1,000 for individuals off treatment. For buprenorphine, the comparable figures were

___________________

9 For more information, see http://www.learn2cope.org (accessed January 25, 2019).

10 For more information, see http://palgroup.org (accessed January 25, 2019).

4.3 per 1,000 for those on treatment versus 9.5 per 1,000 for those who are out of treatment (Sordo et al., 2017). Liebschutz added that observational data from Massachusetts have shown that future mortality of individuals who have experienced a non-fatal overdose and are prescribed either methadone or buprenorphine is about one-third of those who are not on treatment (Larochelle et al., 2018). “These are life-saving medicines,” said Liebschutz.

Behavioral therapies studied as adjuvants to medication include cognitive-based therapies and contingency management. The bottom line after hundreds of studies, said Liebschutz, is that adding behavioral therapy to medication therapy appears to provide no extra benefit to patients. “This is not to say that people will not benefit in some ways from therapy, but it doesn’t necessarily result in improvement in substance use outcomes,” she said. She believes most treatment programs still require adjunctive behavioral therapy because it is a vestige of years of treatment practice.

In summary, Liebschutz said that since the discovery of opioid medications, balancing therapeutic use with the potential for addiction has been critical. The brain, she noted, has a strong adaptive mechanism to opioids, which influences many of the subsequent harms and behaviors. The urgency of this issue is clear given that the opioid use disorder epidemic is bending the mortality curve in the United States and negatively affecting a growing number of children and families. Liebschutz concluded that fortunately, medications to treat opioid use disorder exist, and those treatments do save lives.

PAIN MANAGEMENT FOR PEOPLE WITH SERIOUS ILLNESS: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE CONTEXT OF THE OPIOID USE DISORDER EPIDEMIC

Building on Liebschutz’s introductory presentation, R. Sean Morrison, the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Professor and chair of the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, started the second session by highlighting one of the key themes of the workshop. He pointed out that although it has always been assumed that laws and regulations are not meant to limit the use of opioids for people who are dying or have cancer, there are millions of Americans with serious illness who do not have cancer, who are not dying, and yet who are living in pain and genuinely benefit from the analgesic effects of opioids. For those individuals, said Morrison, the lack of access and ability to obtain these medications can have real consequences. He emphasized that research

clearly shows that pain is undertreated in this country and that untreated pain has real consequences, including chronic pain syndromes, disability, and a negative impact on quality of life.

A Patient’s Perspective on Opioid Use in Serious Illness

To provide real-world context for how opioids serve as life-saving medications for someone with a serious illness who suffers from chronic pain, Morrison introduced Rosanne Leipzig, the Gerald and May Ellen Ritter Professor in the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and her wife Ora Chaikin, who for the past 25 years has suffered from a painful condition that destroys her tendons and joints. More than a decade ago, Leipzig asked Morrison if he would serve as the palliative care physician for Chaikin, and he has cared for her since that time.

Leipzig explained that she approached Morrison after consulting with multiple clinicians who were not only unable to provide a diagnosis for Chaikin’s condition, but could not successfully address the extreme pain she was experiencing. When Chaikin first saw Morrison, the pain in her hands and feet made it difficult to walk or perform activities of daily living. Over the subsequent few years, the pain increased and spread to other joints, including her shoulders and back. Her feet and hands, meanwhile, were deforming because her tendons were “breaking,” according to Chaikin; she has endured multiple surgeries to replace her shoulders and reconstruct her feet.

Chaikin said her relationship with opioids has been difficult. “When I initially started the opioids, I would periodically flush them down the toilet or throw them in the trash because I did not want to be taking them, and I did not want to be labeled an addict or become dependent,” she said. “I felt I could beat this some other way.” Eventually, she accepted that opioids had to be part of her life if she was ever going to be able to function at a high level. Not long afterward, she received a letter from her pharmacy benefit company informing her that it was cutting in half the amount of opioids she could receive. Reversing that decision, she said, took many weeks, during which time she went into withdrawal. Even today, she worries that at any moment her access will be restricted once again, and she has been told by various people that she has to get off opioids. “I am made to feel really like an addict,” said Chaikin.

In fact, when a new owner took over the pharmacy that Chaikin had used for 30 years, he told her that he did not want people like her in his

store and that he would lose his license if he filled her prescription. In a store filled with people, the new owner screamed at Chaikin, calling her an addict. According to Chaikin, the worst part of taking opioids is the judgment from others.

Chaikin explained that when using a mail order pharmacy, her prescriptions are only filled if she submits extra paperwork. The resulting delays in receiving her medication lead her to start tapering her dosage so that she will not run out of medication, but the result is that her pain increases. With regard to functioning and her quality of life, “these medications have made all the difference in the world,” Leipzig observed.

Morrison noted that Chaikin has tried multiple non-opioid therapies over the years and has rotated which opioids she takes to minimize various side effects. At one point, Morrison prescribed an extended-release formulation of hydromorphone, which allowed Chaikin to go through the day without taking a pill every 3 hours. However, that drug has been pulled from the market.

Leipzig recounted one incident when Chaikin received letters from their insurance company informing her that it was reducing the amount of medication she could receive. Morrison, Chaikin’s treating physician, was not notified of this change, and all the pharmacists could do was say they were sorry, telling her “rules are rules.” This problem was not resolved until Leipzig happened to be serving on a panel with the insurance company’s chief medical officer and she explained the situation to him directly. Six weeks later, the issue was resolved.

In closing, Morrison noted that Chaikin is not an exception. “I have an entire panel of people like Ora,” he said. “They are quiet, and they feel this is only them, that they are not empowered, and they feel pretty powerless and helpless.” Leipzig added that she is tired of hearing that there is no evidence that opioids work for chronic pain, stating that a lack of evidence is not the same as having evidence of no effect. “I do not know how we get people to recognize this, but there is an N of one right here,” said Leipzig, pointing to her wife. “Somehow, we need to get the word out.”

With Chaikin and Leipzig providing a compelling real-life perspective of the challenges of treating patients with serious illness and chronic pain, Morrison then introduced the three panelists who would further address the issue: Stefan Kertesz, professor in the Division of Preventive Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine; Cardinale Smith, associate professor of medicine and director of quality for cancer services at the Mount Sinai Health System and the Brookdale Department

of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; and Stefan Friedrichsdorf, medical director in the Department of Pain Medicine, Palliative Care, and Integrative Medicine at the Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota. An open discussion followed the three panelists’ presentations.

Opioid Correction Versus Opioid Trauma: Where Policy Meets Chronic Pain

“This is a time of tragedy, and times of tragedy call for questions,” said Kertesz, referring to the rising number of opioid overdose deaths in the United States. The questions he raised include

- How do we know what we think is right is actually right?

- Could what seems right be wrong?

- For whom might it not be right?

Kertesz pointed out that from the mid-1990s until 2012, opioids were vastly overprescribed, which caused harm warranting a systems-level decline in opioid prescribing (Kertesz and Gordon, 2018). Forced reductions in opioid prescribing, however, are now highly incentivized or even mandated for those patients who have been on opioids over the long term. He argued that this violates both the ethical and evidentiary norms traditionally applied to medical practice. “The adverse consequences of this are evident, and better approaches are available to us,” Kertesz emphasized.

Kertesz recounted a case of a 73-year-old veteran who had painful polyarthritis and had received a renal transplant in 2003. He had been prescribed opioids since 2001 at doses ranging from an equivalent of 105 to 140 milligrams of morphine, but for reasons not documented in his electronic health record, his dose was reduced by several 30 to 60 percent cuts between 2014 and 2016, to the equivalent of 22.5 milligrams of morphine by 2017. Kertesz said the patient accepted all of this without protest, but he suffered a progressive loss of energy and the ability to organize himself and keep track of his medications. In March 2017, this patient was admitted to Kertesz’s inpatient hospital service with progressive failure of his transplanted kidney. “The acute rejection would have been prevented had he been able to keep up with his medicines that were intended to prevent a rejection of the transplanted kidney,” said Kertesz. Unfortunately, a mixture of pain and passivity led the patient to lose his ability to do so.

After dialysis stabilized the patient, Kertesz increased his opioid dose modestly and notified his physician that he had probably gone too far in reducing the dosage. However, within 3 weeks of his release from the hospital, the patient’s dose was cut in half, and he was readmitted twice in the next 6 months. The patient passed away shortly after that time.

For Kertesz, this case raises two policy questions. First, was this person’s opioid reduction considered favorable according to metrics used by the National Committee for Quality Assurance, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Office of the Inspector General at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the U.S. Department of Justice, and by all potential payers? If the answer, he said, is yes, then the second question this case raises is whether the tapering of his dosage protected the patient from harm. Because the patient died, Kertesz explained, the answer is probably no. “That really gets to the heart of the matter,” he said. “Where the metrics in play to reverse a very large and very serious crisis are neutral on the question of whether patients live or die.”

Kertesz noted that his patient had not gone through acute withdrawal, but rather experienced what is called prolonged abstinence syndrome. In fact, this patient never qualified for a diagnosis of opioid use disorder as described in DSM-V. Some patients, he said, do feel better and have more energy after a slow opioid taper. Others, however, go through sedating medications, adopt other ineffective procedures, suffer medical deterioration and loss of care relationships, turn to other illicit substances or alcohol, or become suicidal. By his count, some 50 suicides have been reported publicly in the news or social media that mention both pain and opioid reduction; he emphasized that this does not determine a cause-and-effect relationship. He has reviewed two of these cases in depth and they are quite complicated, he added.

As an aside, Kertesz explained that injectable opioids, such as fentanyl, injectable morphine, and injectable Dilaudid, have been in short supply over the past 2 years, which has affected inpatient treatment of acute pain. In April 2018, the American Society of Health–System Pharmacists reported that 86 percent of medical facilities indicated that shortages were having a moderate to severe effect. They identified the consequences of such shortages as swapping products and formulations (ASHP, 2018); daily deliberations among pharmacists, nurses, and doctors that led to medical errors in some cases; and limiting the responsibility of opioid care to a small group of specialized providers (Bruera, 2018). These shortages are largely

the result of manufacturing shortfalls, with some contribution from today’s tightly regulated supply chain, he added.

The CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain calls on physicians to back away from the tendency to prescribe opioids on the premise that they are not routinely superior to other treatments for chronic pain.11 The CDC guideline also calls for evaluating the risks and benefits of prescribing opioids because these drugs are deeply problematic due to their highly addictive nature and recommend clinicians prescribe the lowest effective dose. For patients already taking opioids, the guideline calls on clinicians to evaluate the harm versus the benefits for that individual patient, though they do not provide a dose target and do not mandate dose reductions (Dowell et al., 2016). Kertesz noted that although the guideline does represent a reasonable consensus of experts, the evidence supporting this guideline was generally of low quality.

Overall, the nation’s response to the opioid use disorder epidemic has been to control prescriptions by tightening product supply and imposing quality indicators based on pill dose and count, noted Kertesz. In addition, 28 states have passed laws regulating opioid dosage (NCSL, 2018). Payers, in essence, are imposing non-consensual tapering, pharmacies are invoking their own liability and responsibilities to reject prescriptions, and physicians are operating under fear of investigation. As a result, said Kertesz, “a single prescription is now subject to multiple, high-stakes, and often conflicting imperatives.”

Kertesz then provided some examples of how these conflicting mandates are playing out in practice. One example he shared was a 2018 form letter sent from a medical practice to its patients, which stated that CMS had implemented a new law mandating that opioid doses not exceed a maximum of 90 equivalents of morphine. The law this letter cited, however, was a state law. Kertesz noted that incorrect legal citations by authorities are commonly used to taper patients off opioids. Some institutions are sending letters to patients informing them they will be tapered by more than 10 percent per week, stating that most patients have less pain with lower doses, which Kertesz said reflects inferences not supported by the evidence. In some cases, institutions are offering group support, cannabidiol (CBD), or buprenorphine as replacements for opioids.

___________________

11 For more information on the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, see https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html (accessed April 1, 2019).

Kertesz also cited a letter from a chain pharmacy to a provider prescribing opioids stating that the pharmacy would no longer fill that provider’s prescriptions for controlled substances without including the specific metric used to justify this action. “This is a letter that effectively blackballs the doctor and their patients forever from that pharmacy if controlled substances are involved,” said Kertesz, who added that many of these letters were issued around the time that many chain pharmacies were named as defendants in combined multidistrict litigation. Additionally, he pointed out that both-Individual pharmacies are also restricting access. In one instance, a patient received a letter requiring medical records, including imaging results and doctors’ notes, and a recent urine drug test that was positive for the opioid, before the pharmacy would fill the patient’s prescription. According to Kertesz, this is little more than a liability reduction exercise that “positions the pharmacist as the assessor of pain care quality.” Additionally, he pointed out that both insurance coverage policies and state Medicaid programs can mandate dose reductions that the CDC guideline did not endorse.12

Kertesz noted that federal prosecutors also are becoming involved. In 2018, for example, the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Atlanta identified 30 top prescribers of opioids in the Atlanta area, even though the U.S. Department of Justice noted it had not determined if those 30 physicians had broken any laws. Kertesz said such efforts are part of the U.S. Department of Justice’s initiative to reduce opioid prescriptions by one-third over the next 3 years. “Will the threat of prison reduce prescribing?” he asked. In his view, he said it probably would.

Kertesz also noted that some health care organizations are highlighting their success in reducing opioid use, yet there is no discussion of how those reductions are affecting patient outcomes. Nationally, high-dose opioid prescribing fell 48 percent over 8 years, yet “the overdose deaths involving potentially prescribed opioids (i.e., natural and semisynthetic, excluding methadone, fentanyl, or heroin) remain constant at approximately 10,000 per year since 2010, according to a query from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System,” according to a study by Kertesz and Gordon (2018). “To me, this signals we may not be pushing on the right string to get the result we want,” Kertesz said.

The policy conundrum, said Kertesz, is that agencies have prioritized opioid counts as the indicator of quality, safety, and good faith, and most invoke the CDC guideline inaccurately. Opioid counts have become the

___________________

12 This text has been revised since prepublication release.

de facto standards for legal risk and professional liability, which makes any patient who receives any longstanding prescription for opioids, but especially at high doses, a liability to all concerned. “What do professionals normally do with liabilities?” asked Kertesz. They “get rid of them,” he answered. He noted there is a case to be made that tapering, whether consensual or not, is helpful to some individuals, but the science on institutionally mandated tapering requires additional discussion. The bottom line, in his view, is that policy has moved ahead of the science, with the crucial missing piece being that the agencies mandating these policies do not measure, nor are they accountable for, patient outcomes, including mortality associated with these policies.

There is, however, another layer to the response to the opioid use disorder epidemic, and that has to do with how health systems respond to and support their clinicians who have been traumatized by the harm they have caused their patients by restricting their access to pain medications. In health care, said Kertesz, the normal response to a catastrophic event is root cause analysis, remediation, investigation, and the offer of support. For deaths related to opioids stoppage or taper, those customary responses to patient harms are conspicuously lacking. “This is a real departure from the normal way we practice health care,” he said.

Regarding the data to support the new regulatory mandates, Kertesz noted that the literature suggests that many patients who voluntarily taper their use of opioids achieve good results (Frank et al., 2017). What is needed, Kertesz asserted, are studies on the effects of mandated policies and data on adverse events, particularly suicidality. For persons with diagnosable opioid use disorder involving prescription opioids, provision of buprenorphine-naloxone for a limited number of weeks followed by taper of that medication resulted in a failure rate of 91.4 percent (Weiss et al., 2011). Kertesz underscored that not all patients receiving long-term opioids would have qualified for this trial, but asserted that such poor results raise questions about tapering as a general policy for patients who have received opioids for pain on a long-term basis. One study also found high rates of suicidal ideation and suicidal self-direct violence in patients undergoing taper after long-term opioid use (Demidenko et al., 2017).

A better approach, said Kertesz, is to focus on the individual patients and the care they require, and not to treat all high-dose opioid users in the same way. He noted that high-dose opioid patients can have a compendium of serious medical, psychological, and substance use disorder-related morbidities that correlate highly with the receipt of high-dose

opioids. “We can care for these conditions, and they are predictive of the very adverse outcomes that we want to prevent, which are overdose and suicide,” said Kertesz. To make corrections at the systems level, he emphasized two key issues:

- A crucial step is to reverse metrics, policies, and legal threats that jeopardize protection of legacy patients; nearly all of these factors violate the CDC guideline while invoking its authority.

- Any entity using metrics based on prescription numbers must collect and publicly report patient outcomes, including whether they are dead or alive, if their care has been continuous or if they have lost care, and whether they were hospitalized or not, and be held accountable for adverse outcomes.

In closing, Kertesz pointed out that enacting health policy with no measurement of patient outcomes and no accountability is how the nation has gotten into the current mess. “This is a time of tragedy and a time for choosing,” he said. “We professionals are implicated in creating this tragedy, and regulators are as well. We are under the gun, but so are our patients.” While nobody at present has complete knowledge of what is right, he added, it is still important to ask how we know what we think is right is actually right.

Disparities in Access to Pain Medications

People of color overall disproportionately have higher morbidity and mortality rates when facing serious illness “and pain is a significant contributor to that,” noted Cardinale Smith, who has personal experience with these challenges. Smith’s 52-year-old father was diagnosed with Stage IV rectal cancer, and his physician at Mount Sinai prescribed a fentanyl patch to help relieve his pain. Smith, who was a fellow in oncology and palliative medicine at the time, went to five pharmacies in Brooklyn, where her father lived, before finally finding a pharmacy in Manhattan that could fill the prescription. Eventually, her father’s physician changed dosing from every 72 hours to every 48 hours because that worked better for her father. The pharmacist accused Smith’s father of diverting the patches, and called the prescribing physician and told him that fentanyl could not be dosed every 48 hours. As Smith remarked, the fact that she, as a clinician, could not get her father the care he needed underscores the problem facing those indi-

viduals who are not well versed in opioid prescribing, who are not health literate, and who cannot advocate for themselves.

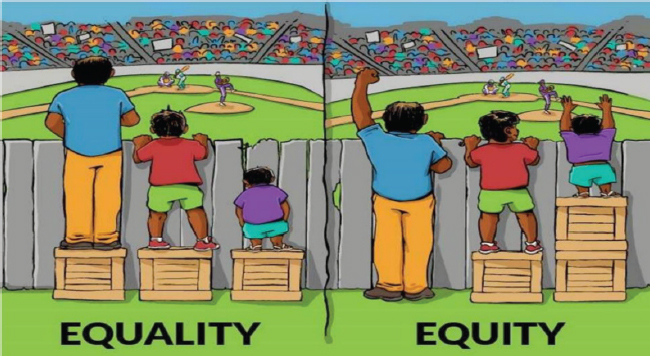

Smith said there are several definitions of health care disparities put forth by different organizations (see Table 1). The definition she favors, from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, notes that a certain population is a health disparity population if there is a significant difference in the overall rate of disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity, mortality, or survival rates in the population as compared to the health status of the general population. Smith also explained the difference between equality, which provides everybody with the same thing, and equity, which provides extra resources to those most in need (see Figure 6). Given the changing demographics of the nation, with minority populations, and particularly the Hispanic or Latino population, growing at a faster rate than the population as a whole, it is likely that there will be an increase in disparities when it comes to having access to pain medication, said Smith.

TABLE 1 Definitions of Health Care Disparities

| Organization/Group | Definition |

|---|---|

| CDC/Healthy People 2020 | Type of difference in health that is closely linked with social or economic disadvantage. Health disparities negatively affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater social or economic obstacles to health. These obstacles stem from characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion such as race or ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, gender, mental health, sexual orientation, or geographic location. |

| IOM | Racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention. |

| NIH | Health disparities are differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and burden of diseases and other adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups in the United States. |

| NIMHD | A population is a health disparity population if there is a significant disparity in the overall rate of disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity, mortality, or survival rates in the population as compared to the health status of the general population. |

NOTE: CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; IOM = Institute of Medicine; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

SOURCE: As presented by Cardinale Smith, November 29, 2018.

SOURCES: As presented by Cardinale Smith, November 29, 2018; Interaction Institute for Social Change, Artist: Angus Maguire, interactioninstitute.org, madewithangus.com.

Chronic pain, said Smith, affects more people in the United States than common diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer, and there is an unequal burden of pain across racial and ethnic populations. In general, said Smith, different races and ethnicities self-report about the same rates of illicit drug use, but the rate of drug-induced deaths is far higher in whites than in Hispanics or African Americans.

The bottom line, said Smith, is that minority patients with pain have less access to pain medications and to the specialists who can prescribe them. They are also less likely to have their pain recorded, assessed, and treated, and are at increased risk for under-treatment of their pain. As Morrison noted earlier, there are real consequences of pain in terms of a person’s ability to work and earn a living, with a significant impact on family dynamics.

There are many factors responsible for these disparities, said Smith, including health system–level factors such as PDMPs and the reluctance of pharmacies to fill prescriptions for opioids when the patient is a member of a minority population. At the clinician level, many providers lack knowledge about how to treat pain, operate on false stereotypes, and have implicit bias regarding minority populations and opioid use disorder. Patient-level factors include a fear of addiction and dependence that may be more prevalent in minority populations, as well as disparities in communication between patient and provider that arise during the clinical encounter.

Smith noted that a meta-analysis of multiple pain studies conducted between 1989 and 2011 found a significant gap in the quality of pain management that African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos received compared with Whites (Meghani et al., 2012). She added that another finding from this study was that Hispanics/Latinos and African Americans were more likely to receive non-opioid analgesics such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Similarly, a study looking at children up to age 21 who came to the emergency department with appendicitis found that African Americans were less likely to have their pain treated with opioids or any pain medication than were White children (Goyal et al., 2015).

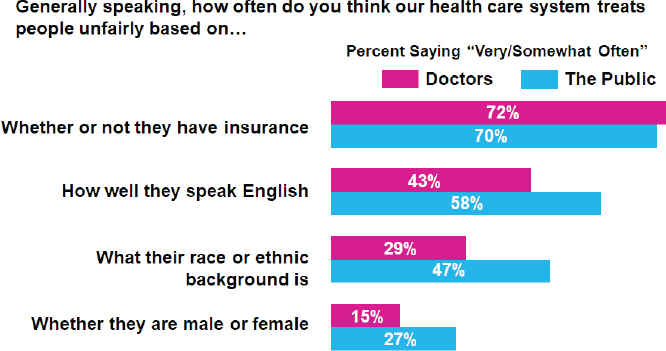

Smith wonders how well-meaning, highly educated health care professionals working in their usual environment with a diverse population of patients can create a pattern of care that appears to be discriminatory. She does not believe her clinician colleagues are purposefully racist or discriminatory, but rather are discriminating because of imposed limitations and implicit bias. She noted studies from the Kaiser Family Foundation that sometimes asked physicians and always asked members of the public questions about how often they think health care systems treat people unfairly based on several criteria (Kaiser Family Foundation, 1999, 2002) (see Figure 7). The overall finding was that physicians believed disparities in care occurred less frequently than did the general public.

SOURCES: As presented by Cardinale Smith, November 29, 2018; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2002.

Another issue, noted Smith, is that physicians underestimate pain, particularly compared with how their patients perceive it. One study, for example, examined patients’ and physicians’ perceptions of chronic, non-cancer pain at 12 academic medical centers and found that “physicians are twice as likely to underestimate pain in Black patients compared to all other ethnicities combined” (Staton et al., 2007). However, researchers have found that even for patients who have been properly assessed and given a prescription of an opioid to treat their pain, those living in neighborhoods where the population was predominantly African American, Hispanic, or Asian had access to far fewer pharmacies with adequate opioid supplies compared with neighborhoods that were predominantly White (Morrison et al., 2000). One study in Michigan, which examined socioeconomic status and race, found that pharmacies in zip codes that contained large minority populations were less likely to carry “sufficient opioid analgesics” than those in zip codes with majority White populations regardless of income (Green et al., 2005).

Regarding PDMPs, Smith said there have been some studies on the impact of those programs on opioid prescribing rates, but few have looked at the effect of those programs on patient outcomes. “I would argue it is great to see numbers go down, but it is really the patient in front of us that matters,” said Smith. One 2017 study found that the number of opioid prescriptions received by Medicaid recipients fell the most in states that have mandated that providers both register to be tracked in a drug monitoring system and use the system when making prescribing decisions for patients (Wen et al., 2017).

State laws are also contributing to limits on opioid prescriptions, said Smith. In New York, for example, the law requires a new prescription for someone with acute pain to be limited to 7 days of medication.13 The law does exempt those with serious illness such as cancer or those in palliative care and hospice. Smith, who treats cancer patients, said that even when she writes a prescription in her health system’s electronic health record and adds the correct diagnostic code, she still receives a call from the pharmacist making sure that she is prescribing the correct amount. “So, when you think about the barriers and the challenges that are put in place for clinicians who already are underestimating pain and not treating it as frequently in minority populations, one can imagine that that disparity only has the potential to increase,” said Smith.

___________________

13 For more information, see https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/program/update/2016/2016-07.htm#opioid (accessed March 6, 2019).

Smith also noted that health plans and pharmacies are developing their own rules and regulations about what they will or will not prescribe. Although she applauds those efforts, Smith said they have the effect of taking a medical decision out of the hands of the frontline clinicians. Her concern is that doing so could make it even more difficult for vulnerable populations to access and receive the treatment they need. “In trying to do well, we are creating an even bigger gap,” said Smith. “We want to be able to provide the care that is best, but at the same time, limit the challenges that we are seeing.”

In closing, Smith suggested that solutions to these challenges might start with changing the narrative from one that stereotypes people of color as the problem, given that the biggest rise in opioid-related deaths has been among White suburban and rural populations. In addition, said Smith, improvements must be made in the way clinicians are trained to treat pain, and access needs to increase to palliative care and pain specialists who are trained to screen for and treat opioid use disorder.

Pain Management for Children with Serious Illness: Challenges and Opportunities in the Context of the Opioid Use Disorder Epidemic

Shifting the focus to the pediatric perspective, Stefan Friedrichsdorf of the Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota opened his remarks by observing that, despite the fact that children ages 17 and younger make up more than 22 percent of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014), the CDC guideline referred to by previous workshop speakers includes nothing about children—the guideline pertains to individuals age 18 years and older. Friedrichsdorf noted that no pediatricians were included in the working group that produced the guideline. Pain, according to Friedrichsdorf, is common, underrecognized, and undertreated in children (Friedrichsdorf et al., 2015). In fact, despite an increase in adult misuse of opioids, adults receive more pain medication than children with the same underlying condition (Beyer et al., 1983; Eland and Anderson, 1977; Schechter et al., 1986). In addition, said Friedrichsdorf, the younger the child is, the less likely they are to receive the appropriate analgesia to treat their pain (Broome et al., 1996; Ellis et al., 2002; Nikanne et al., 1999).

The problem with undertreating pain in children, explained Friedrichsdorf, is that children with persistent pain become adults with chronic pain, anxiety, and depression (Friedrichsdorf et al., 2016). In addition, inadequate analgesia for an initial procedure in children diminishes

the effect of adequate analgesia in subsequent procedures (Weisman et al., 1998), while morbidity and mortality increases in preterm neonates who are undertreated for pain (Anand et al., 1999). Friedrichsdorf noted, too, that children with injury or acute burns are less likely to develop posttraumatic stress disorder in the months following treatment with higher doses of morphine (Nixon et al., 2010; Saxe et al., 2001; Stoddard et al., 2009).

By conservative estimates, there are 237,000 children ages 17 and under in the United States who are living with a life-limiting condition (Friedrichsdorf, 2017). In 1997, deaths attributed to all complex chronic conditions accounted for 7,242 infant deaths, 2,835 childhood deaths, and 5,109 adolescent deaths (Feudtner et al., 2001). On average, said Friedrichsdorf, children with advanced cancer at the end of life had a median of five symptoms, three causing high distress.14 Friedrichsdorf identified three of these symptoms (dyspnea, cough, and pain) that would benefit from opioid treatment. Opioids, he said, are associated with many side effects and are potentially lethal, but “no other analgesics equal in potency and effect have been discovered or developed to reduce suffering” (Krane et al., 2018).

The opioid use disorder epidemic in the United States has produced “many experts, pundits, and politicians who really offer simplistic blameworthy origins for the problem,” and “simplistic soundbites and solutions,” said Friedrichsdorf. His views are shared by Krane and colleagues in a 2018 article. He noted that although physicians may be blamed for prescribing an opioid that leads to addiction and death of a previously healthy child, the fact is that the “first exposure to non-medical use of opioids in adolescents occurs most often from access to family members’ or friends’ prescriptions, not their own” (Krane et al., 2018). In a comprehensive article, Miech and colleagues concluded that “legitimate use of prescription opioids before high school completion does not predict opioid misuse after high school” (Miech et al., 2015).

On average, said Friedrichsdorf, people who die from a drug overdose have six medications in their bloodstream. Although dentists who prescribe too many opioid pills for a wisdom tooth extraction or root canal procedure need to be targeted, for example, the main problem with substance use disorders is that they are embedded in a “complicated matrix in our country of despair and hopelessness,” said Friedrichsdorf. He noted that

___________________

14 The median PediQUEST Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (PQ-MSAS) total score was 9.3 in a study (Wolfe et al., 2015).

such despair and hopelessness correlates closely with socioeconomic factors such as unemployment, poor education, availability of illicit street opioids and diverted prescription opioids, a genetic predisposition to substance use disorder, and psychiatric conditions. There is scant evidence, he asserted, to support the existence of an epidemic of deaths resulting from the appropriate use of prescribed opioids (Krane et al., 2018). “How many children have to suffer needlessly from pain to avoid one opioid death?” asked Friedrichsdorf.

To counter the notion that prescribing morphine to a child with cancer will make it more likely that that child will be addicted to drugs when he or she grows up, Friedrichsdorf cited a study of more than 4,000 high school students. The study showed that medical use of prescription opioids without any history of non-medical use of prescription opioids is not associated with substance use behaviors at age 35 (McCabe et al., 2016). In contrast, adolescents who reported any history of non-medical use of prescription opioids did have an increased risk of substance use behaviors during adolescence (McCabe et al., 2007).

Friedrichsdorf also cited a study of public school students in Detroit. The study revealed that 76 percent of the students who were misusing an opioid by taking more than prescribed did so for pain relief only, while the other 24 percent of students did so to address non–pain relief motives (including experimentation, getting high, counteracting the effects of other drugs, safer than street drugs, and other motives). The study indicated that four out of five students in grades 7 to 11 who were prescribed opioids took them as prescribed (McCabe et al., 2013). Friedrichsdorf added that U.S. government statistics show that misuse of opioids among U.S. 12th graders has dropped dramatically despite the high overdose rates among adults (NIDA, 2017).

Many of the regulations applied to children and adolescents have no basis in scientific fact, noted Friedrichsdorf. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has warned against prescribing tramadol to children because three children died over the past 50 years. Friedrichsdorf stressed that the question to ask is not whether it is appropriate to use opioids to treat pain in children, but rather, what amount of opioid prescribing is appropriate in children.

Friedrichsdorf and his colleagues take a multimodal approach to analgesia in children and use several different medications that act synergistically to provide more effective pediatric pain control with fewer side effects than would be achieved with a single analgesic. For acute pain, opioids are an

important part of this approach in addition to adjuvant analgesia or to basic analgesia, according to Friedrichsdorf.

Friedrichsdorf pointed out that for chronic pain in children, opioids are actually contraindicated, and instead, he and his colleagues rely on physical and occupational therapy, integrative therapies, cognitive behavioral therapy, and getting children back into normal life. The problem, said Friedrichsdorf, is that few children in pain have access to clinics that offer these approaches to pain control, given that there are only eight functioning pediatric pain clinics in the nation. Even if a person happens to live near one of these clinics, insurers often refuse coverage for these evidence-based treatments. His clinic has a waiting list of 5,000 children. In fact, most children’s hospitals do not have a designated inpatient pain team, and most insurers base reimbursements on adult guidelines that are not applicable to children.

In conclusion, Friedrichsdorf said that children in severe, acute pain are suffering today because adult experts crafted adult guidelines with no consideration of the 22 percent of the U.S. population that is under age 18. For Friedrichsdorf, withholding evidence-based analgesia to children is not only unethical, but also causes both immediate and long-term harm. While there are potential safety risks, such risks are manageable and do not justify denying administration of opioids to pediatric patients who have severe tissue injuries or who are at the end of their lives because of serious illness. In addition, he said, limiting access to pain clinics and appropriate pain medication risks driving adolescents in particular to illicit drugs that carry a much greater risk to their health and lives. Pediatric patients, he said, need access to interdisciplinary outpatient pediatric pain clinics, inpatient pediatric services, mental health services, and drug treatment programs covered by health insurance.

Discussion

During the discussion session following the speakers’ presentations, workshop participant Diana Martins-Welch from Northwell Health asked the panelists if they had recommendations on how to treat patients with serious pain from Stage IV cancers and a history of substance use disorder. Although Kertesz pointed out that this topic would be covered in the next workshop session, he did note that his approach is to treat each individual differently, based on his or her unique situation. Some patients, for example, might need an extremely close monitoring program that involves knowledgeable nurses, while others might benefit from a non-opioid treatment.

Whatever the decision, he negotiates it up front through an explicit conversation with the patient.

Tulsky asked the panelists if the current attention paid to opioid use disorder reflects a racial bias, given that it has only come to prominence now that it is affecting White, rural communities. Smith replied that when illicit opioids were affecting minority communities, the response was that this was a legal justice system crisis, not a public health crisis, and the response was to put people in jail rather than treat their substance use disorder. She said “this only leads to and increases the bias.”

Workshop participant Jack Rossfeld, a physician from Ohio, asked Kertesz if there are any policy demonstrations that measure patient outcomes, rather than pill counts. Kertesz replied that there are measurement tools to help determine who is at higher risk of developing an adverse outcome. The question then becomes what to do when such a tool identifies someone who is at high risk for an adverse outcome with opioids. He noted that the VA Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Management (STORM) uses a real-time data dashboard to present an individual patient’s risk level as well as patient-specific clinical risk factors (Oliva et al., 2017). What is missing, though, is evidence supporting what to do for those individuals who are at risk of adverse outcomes with opioids, most of whom have untreated mental health issues. There is no large trial proving how to get patients safely into care, according to Kertesz. He stressed the need for mentorship and support for primary care providers who prescribe opioids.

Workshop participant Marian Grant, a policy consultant and palliative care nurse practitioner, noted that she has seen the pendulum swing to where clinicians are now reluctant to prescribe opioids for patients with appropriate need. Recently, she explained, she had two cancer patients who used heroin, and one went back to using street drugs. The other patient, who was highly adherent with her methadone program, was struggling to deal with her pain without turning to street drugs. Grant’s question to the panelists was what can be done to change the attitudes of clinicians, many of whom seem to have a “just say no” attitude to prescribing opioids. Kertesz said those clinicians need a safe harbor, which will require a robust statement from a public authority such as CDC, the American Medical Association (AMA), and perhaps the DEA, that they will be protected in these situations. His institution offers a consultative service where senior physicians can offer advice and support for difficult cases, but there is only so much safe harbor a senior doctor can provide. “We need insurers and officials to speak up,” said Kertesz. Grant added that she was encouraged by

a recent resolution15 from AMA that pushed back at regulations that limit how doctors practice medicine.

As a palliative care clinician, Smith said she is comfortable managing pain and prescribing high doses of opioids when needed. However, what she has not learned is how to treat substance and opioid use disorder other than through an 8-hour course. Therefore, she is not comfortable treating substance and opioid use disorder. “I am fortunate that I have friends who are experts, but that is not true for the vast majority of clinicians who practice in this country,” said Smith. Though her institution does have a substance use disorder clinic, she is unable to enroll her Medicaid patients in it.

Noting that he has heard from hospice medical directors that physicians in hospice settings refuse to write prescriptions for opioids and instead want the medical director to take the responsibility and possible liability of writing the opioid prescription, workshop participant Paul Tatum asked how to convince primary care providers that they are the best prescribers. Kertesz responded that, in fact, primary care providers might not be the best prescribers given that they may lack training on addiction, dependency, and treating pain. That said, it would not be practical to send every patient in need of an opioid prescription to the medical director of a hospice or palliative care program. “We are going to have to offer a degree of support and training that is beyond merely alluding to a guideline or a website,” said Kertesz. In his opinion, those clinicians are clearly afraid and there is a need to address their fears with education, mentoring, and help.

Salimah Meghani from the University of Pennsylvania noted that the CDC guideline is of low quality, yet has been widely adopted by states, payers, insurers, pharmacists, and others as being evidence based. In her opinion, CDC and other federal agencies have turned a blind eye to the misapplication of the guideline (Meghani, 2016); this is particularly so in the case of pediatrics. At the same time, the President’s Opioid Commission’s report, issued in November 2017, recommends removing pain assessment from patient satisfaction surveys. Liebschutz questioned what could be done to increase the federal government’s accountability regarding the widespread adoption of the CDC guideline. Friedrichsdorf said he did not have a good answer other than reworking the guideline with input from pediatricians and including evidence to support the guideline.

___________________

15 For more information, see https://www.medpagetoday.com/meetingcoverage/ama/76322 (accessed April 1, 2019).

ADDRESSING THE CHALLENGE OF PATIENTS WITH COMORBID SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER AND SERIOUS ILLNESS

Jessica Merlin, associate professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, introduced herself as a general internist who trained in infectious diseases and palliative care and now practices as an addiction physician and behavioral scientist who runs a chronic pain clinic for people living with HIV/AIDS. She then provided some definitions for chronic pain, addiction or substance use disorder, and serious illness.

Chronic pain, explained Merlin, is distinguished from acute pain by duration, with chronic pain lasting at least 3 months (Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee, 2016; IOM, 2011). Chronic pain, she said, affects some 10 percent of the U.S. population (IOM, 2011). Although chronic pain can originate from an initial tissue injury, in some conditions, such as fibromyalgia or chronic lower back pain, the brain receives a strong pain signal even when there is no inflammation in the periphery. Chronic pain is not a symptom, observed Merlin, but is a chronic disease in and of itself. Thus, chronic pain is heavily influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors, and the optimal treatment should be multidisciplinary and include both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches.

Addiction, now called “substance use disorder,” is also a chronic disease, Merlin explained, that hijacks the brain’s pleasure reward system and can result in compulsive use of any number of substances, often simultaneously. As Liebschutz noted in her presentation, the DSM-V criteria for a substance use disorder includes a long list of items. Treatment involves both medication and psychosocial therapies.

Serious illness, said Merlin, is defined as a health condition that carries a high risk of mortality and either negatively affects a person’s daily function or quality of life or excessively strains their caregivers (Kelley and Bollens-Lund, 2018). Examples of serious illness include cancer, pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and dementia, among others.

Chronic pain, serious illness, and substance use disorder can intersect in a given patient in many ways, said Merlin (Paice, 2018). Chronic pain and substance use disorder are both common, and individuals who develop serious illness may already experience chronic pain, have a substance use disorder, or both. She noted that while pain and substance use disorder do not always occur together, addiction is more common in people with pain

than in the general population. This may be because the opioids used to treat pain can be powerful triggers for addiction in people who are predisposed to it, or who have had a substance use disorder prior to developing chronic pain. In addition, pain is a common complication of serious illness, particularly as people live longer with their serious illness as a result of the development of new therapies. Moreover, serious illness can trigger a great deal of stress, which itself can exacerbate pain and be a powerful trigger for addiction. The result can be that individuals with serious illness will have chronic pain and develop a substance use disorder, Merlin explained.

Merlin said there is limited research at the intersection of serious illness, chronic pain, and substance use disorder despite it being an important clinical problem. In particular, there have been few studies on approaches for managing patients with serious illness, chronic pain, and a substance use disorder. The current literature focuses on patients with cancer in oncology and those in palliative care settings. Most cancer treatment programs, she said, do not screen their patients for opioid use disorder or substance use disorder risk (Tan et al., 2015). Those that do screen find that 20 to 40 percent of their patients have an elevated risk of opioid misuse when prescribed opioids for pain (Koyyalagunta et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2014; Yennurajalingam et al., 2018), and 10 percent report elevated and unhealthy alcohol use (Giusti et al., 2019). One study revealed that approximately 6 percent of cancer patients studied were diagnosed with a substance use disorder (Ho and Rosenheck, 2018). Merlin pointed out that concerning urine drug testing findings include toxicology results that are positive for substances not prescribed (e.g., cocaine, opioids that are not prescribed) or negative for substances that are prescribed (e.g., opioids). According to at least two studies, a significant share of oncology patients has these unexpected findings. In one study by Rauenzahn and colleagues, 46 percent of oncology patients at high risk for substance misuse tested positive for non-prescribed opioids, benzodiazepines, or potent illicit drugs such as heroin or cocaine. Thirty-nine percent of patients tested inappropriately negative (Rauenzahn et al., 2017). In another study, 54 percent of advanced cancer patients who were receiving chronic opioid therapy had abnormal urine drug test results (Arthur et al., 2016).

Merlin noted that pain management is an important component of palliative care, which is specialized medical care for people living with serious illness. It focuses on providing relief from the symptoms and the stress of serious illness to improve the quality of life for both the patient and family. She pointed out those individuals who have both pain and a substance use disorder often present to palliative care settings. Merlin and her colleagues

conducted a national study of palliative care providers in which they asked about cancer survivors with chronic pain who were not at the end of life. More than half of the physicians and nurse practitioners who responded to the survey reported that they spend more than 30 minutes per day managing opioid misuse behaviors. At the same time, the respondents said that on a scale of 0 to 10, they rated their confidence in their ability to manage substance use disorder at a 5. Only 27 percent of the respondents reported having training or access to systems in place to address substance use disorder in their practices. Only 13 percent had a DEA waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, and 36 percent had no access to a substance use disorder specialist (Merlin et al., 2019).

Given the limited evidence base and the prevalence of comorbid serious illness, pain, and substance use disorder, Merlin and her colleagues have called for more research on:

- how to assess opioid risks, harms, and benefits in those with serious illness;

- what other pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches might benefit patients;

- how to manage concerning behaviors tied to substance use disorder in patients with serious illness; and

- efforts in education and policy around these issues (Schenker et al., 2018).