2

Modeling Methodologies

This chapter covers two presentations and a discussion on data collection and modeling considerations for facilities staffing at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The topics covered included modeling methodologies for staffing and various work measurement techniques, along with factors influencing the choice of appropriate techniques, as well as future trends important in workforce modeling.

MODELING FOR THE FUTURE

For the session on future trends in the applicability and aggregation of staffing models in both the field of facilities management and in the specifics of staffing models themselves, the committee had asked the speaker to address the following questions:

How do you determine when a heuristic model is good enough? Can you have several models with different structures, even bases, for different groups of staff? And, how do you know what level of aggregation is “best” for a model: individual departments, groups of departments, or whole organizations?

Brian Norman (Compass Manpower Experts, LLC) began his presentation by responding directly to the guiding questions posed by the committee. For the first question, on when a heuristic model1 is good enough for staffing modeling requirements, Norman said that, in his opinion, a model that can explain at least 80 percent of the staffing needed to perform the mission is a good model. He then noted, however, that whether a model is “good enough” actually depends on a number of factors including, but not limited to, the purpose of the model (strategic versus tactical); the precision required, in terms of acceptable levels of operational risk; what the organization can afford and the cost of getting it wrong; and whether or not the model is useful and straightforward enough to be applied by the organization.

As examples of heuristics that can be used for staffing modeling, Norman provided some of the staffing benchmarks for health care facilities from the International Facility Management Association/American Society for Healthcare Engineering, noting that these “rule-of-thumb” ratios are a recommended starting point for understanding the needs of a system. He suggested that, as a first step, current staffing data should be gathered VHA-wide

___________________

1 Heuristic models are those that reflect the imprecise observed aspects of a modeled system, including uncertainties in the modeled environments that are not easily estimated mathematically (such as ignorance).

and compared with other campuses across the VHA. Once an overview exists of what is going on at each facility, variations of the staffing can be explored, and the staffing needs of facilities with varying needs can be used to refine the model ratios to prepare for a more advanced model.

Turning to the committee’s second question, on whether one can have several models with different structures or even bases, Norman said that it is normal to use a mix of tools to build out models to quantify different work centers. In addition, he said, models can be bundled together into a larger model that depicts the whole requirement. To illustrate the use of multiple models in a given organization, he said that “an organization might have a chief position that is staffed with only one person and does not rely on a calculation. The modeler just gives them a ‘one’ in the model and moves on checking if they have support staff, etc. Support or indirect workers can be included as staff using ratios or percentages, but it is good to do time measure studies on those employees to better understand the various positions.” Norman stated that what he really likes to tie his measures into is where one can count a “widget,” an outcome, or some kind of specific production level to the staffing level. Norman reiterated that all of these core models are subject to workload variances, based on the unique situations present at different locations.

In response to the committee’s third question, regarding the level of aggregation that is best for a model, Norman replied that, again, it depends on the purpose of the model. He stated: “I like models that you can take and roll up to higher levels but that you can apply locally to practically get a realistic operational answer.” He warned that aggregation without understanding can sometimes provide unrealistic results, particularly when there are variations in processes and procedures, environment, and facilities.2

Norman then switched from the committee’s questions to a discussion of future trends that will drive new staffing models. He first focused on trends in the field of facilities management. He explained that advances in information technology will move health care into an era of “smart” systems, similar to what has happened with airliners and military aircraft. These systems will let operators know when preventive maintenance should be performed or if a system needs to be repaired. Entire facilities will eventually be connected by “the Internet of (health) things” and mapped out in a virtual model that will make the entire system observable from a “dashboard”3 at a high level. Such a model will require changes in the number and type of maintenance staff required for a facility.

Another trend in facilities management that will influence future staffing models is the use of advanced facility/maintenance management systems. Norman stressed that investing in a robust system not only decreases the paperwork burden on maintenance workers, but is also “very powerful, because that kind of data can drive good answers to what you need for staffing things.” Norman explained that certain areas of health care facilities in which it is imperative that the systems function properly, such as outpatient surgery centers, might require a more robust, and therefore more expensive, maintenance management system than other areas of a facility. He acknowledged that, compared with other types of industries, health care facilities face a difficult task in terms of staffing because the nature of the work and the strict accreditation requirements, such as those of The Joint Commission,4 which mandate that high maintenance standards must consistently be met to minimize risk.

Norman noted the trend toward viewing facilities management as an operational partner in the health care industry, rather than simply as a cost. He advised the VHA to treat its facilities management teams as if they are “vested in the life of that system,” as a partner in delivering good outcomes for patients.

In terms of future trends in staffing models themselves, Norman mentioned the leveraging of “big data”5 as a key aspect in the evolution of these models. Advances in data visualization tools now allow immediate identification of outliers and trends that can influence the building of models, including digital views of entire facilities. The use of big data can result in sophisticated machine learning that can be integrated into self-diagnostic systems software.

___________________

2 See, for example, this seminal paper on the challenges associated with the mixing or aggregation of model variables when they are correctly different in purpose and definition: Robinson, W.S. (1950). “Ecological Correlations and the Behavior of Individuals.” American Sociological Review, 15(3) pp. 351–357, doi:10.2307/2087176. JSTOR 2087176.

3 A dashboard is a single view of useful information that is easily readable. It is usually a graphical display of the key performance indicators a team wants to monitor regularly.

4 The Joint Commission is a U.S.-based nonprofit organization that accredits more than 21,000 U.S. health care organizations and programs.

5 Extremely large data sets that can be analyzed computationally to reveal patterns, trends, and associations.

In concert with the rise of big data, Norman said he sees a trend in the rebirth of manpower modeling, which was effectively used as early as World War II, before the age of advanced computers. Traditional modeling practices, such as certain measurement techniques, are making a comeback, now coupled with today’s powerful analytic tools. Norman noted that high staffing costs, which can be as much as one-third of the costs of any large system, are often the impetus for the rebirth of interest in modeling techniques. Furthermore, because of the increasing demand for modeling, very effective “boutique” types of modeling tools are being developed for very specific industries, such as law enforcement and call centers.

Another trend that will affect the future of staffing models, Norman said, is the changing workforce. In the past, the workforce consisted primarily of three classifications of workers: full time, part time, and contractors. Today, in contrast, there are many more classifications of workers, including, but not limited to, freelancers, seasonal, temporary, and job-share. For the VHA, Norman advised that the entire system should be examined in terms of the mix of workers involved, because this complexity affects the creation of a staffing model: “You’ve got to look at the whole thing. What are your responsibilities for facility maintenance, and are they in-house or are they outsourced? That’s a big deal. You’ve got to look at the whole picture to get a whole-picture answer. And you have got to decide then what should be and should not be in-house or outsourced, and for what reasons.”

Norman’s presentation generated discussion on the importance of good data and accurate data labeling. He cautioned against accepting the data provided for modeling at face value, noting that, in addition to issues with inaccurate reporting, data pulled from different locations can be labeled differently, preventing accurate comparisons or meaningful aggregation. If an organization has not performed a proper review of its data, Norman suggested that time for that review be built into the modeling time. Relatedly, when systems are developed for collecting staffing data, he said, those systems should not be so difficult that workers entering the data get frustrated and “put in the wrong data, just to get through their day.”

To conclude, Norman reiterated what he sees as a common theme of the session’s discussions: staffing models need to be developed with a specific purpose in mind and created to operate within an organization’s overall system of budgeting and planning. Moreover, the exact framework for the model—whether it will be implemented strictly or used as a guide only—should be determined up front, in order for the model to be of use to the organization. He concluded with a caution about building and using models: “You’re looking at this as a system. You don’t build a model just to have somebody maybe try to apply it. It has got to operate in your budgeting system and your planning system and how you fund things. It has got to have some muscle. You can’t just say, ‘I don’t feel like using this.’”

WORK MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES

For the session on work measurement techniques and the conditions that contribute to their success, the committee had asked the speaker to address the following questions:

What is the measured validity of work measurement (WM) techniques? Job completion time may be highly variable for maintenance tasks: How do WM techniques take this into account when many were developed for short-cycle repetitive tasks? How do WM techniques deal with quality of task output? Is the traditional speed/accuracy trade-off considered? What are the costs and benefits of the various measurement techniques? Are archival data a valid predictor of how long a task should take, or just of how long it does take currently? Is the use of focus groups of subject matter experts (SMEs) a valid way of measuring time for a job? Are there automated measurement processes and what is their validity and cost? How granular are the measurements and how granular do they need to be? What are the respondents’ reactions to the measurement process and to implementation of any measurement-based policies? Do the measurement techniques meet such basic measurement requirements as minimizing criterion deficiency and criterion contamination?

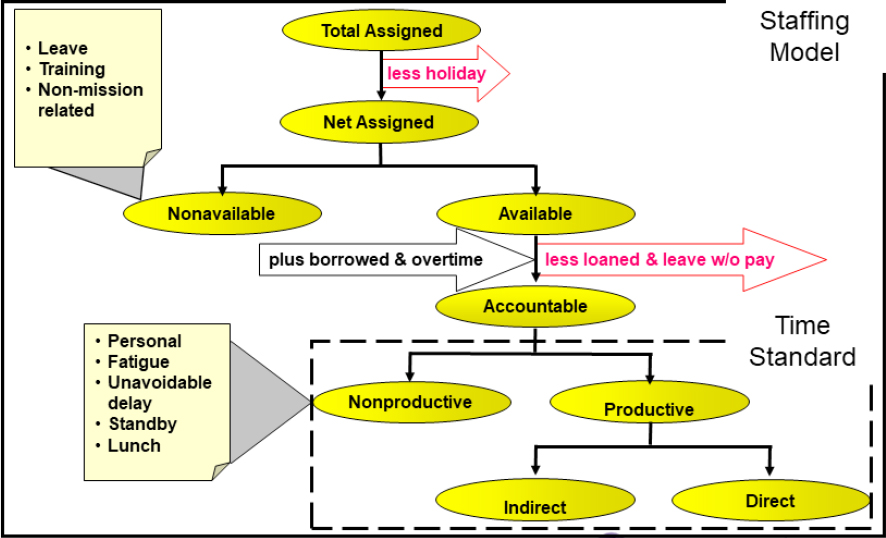

Neal Schmeidler (Grant Thornton) explained that, to model staffing, it is important to first understand how employees’ time is spent, which can be accomplished through the process of work measurement. To clarify this basic prerequisite of a staffing model, Schmeidler illustrated the way that an employee’s total assigned time is broken down: see Figure 2-1. Tight job time standards can be obtained by a study of accountable time, and all aspects of assigned time have to be considered for a staffing model.

SOURCE: Schmeidler, N. (2019). Work Measurement Operations Research. Presentation for the Workshop on Resourcing, Workforce Modeling, and Staffing (slide #6). Reprinted with permission.

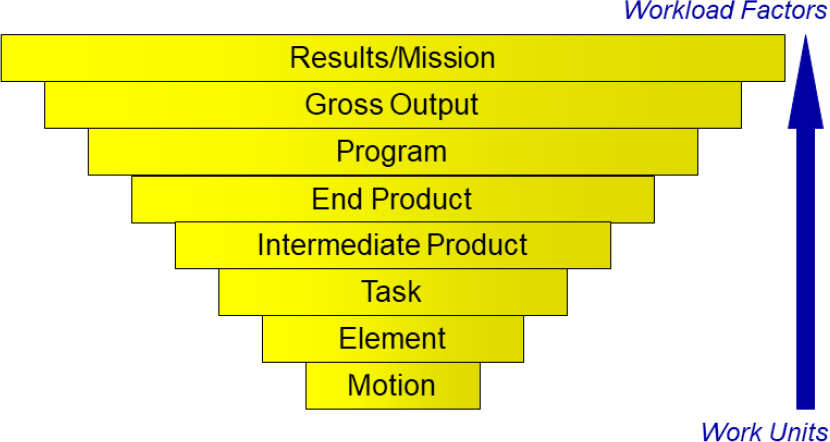

The second basic concept that has to be understood prior to performing work measurement for the purpose of a staffing model is the hierarchical levels of the work being performed. In order to accurately measure work, the method in which detailed-level work rolls up to the desired mission must be clearly delineated: see Figure 2-2. Schmeidler acknowledged that this is not always simple, but it is critical for structuring the measurement such that nothing is missed or double-counted.

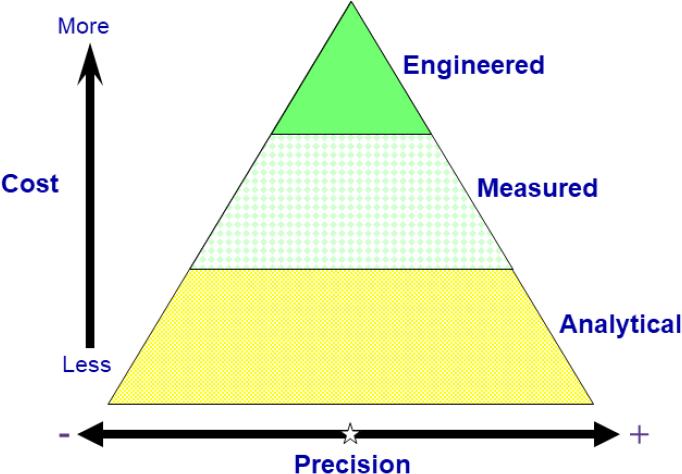

Schmeidler described six techniques that can be used to measure work, first noting that work measurement techniques can be divided into three categories: analytical, measured, and engineered: see Figure 2-3. These categories of tools vary in precision and cost. Analytical tools are the least precise, with a confidence interval in his experience of 15 to 20 percent, but also the least expensive. Engineered tools have the greatest level of precision, plus or minus 5 percent, but they are the costliest. Measured standards fall between the two. The six techniques Schmeidler discussed, in descending order of precision, are predetermined time study, stopwatch time study, work sampling, standard data, historical data, and judgment estimating. Since these tools necessitate varying levels of investment, it is important to determine resource constraints—including the funding, staff, and time that are available for the effort—prior to choosing a work measurement tool.

In addition to resources, Schmeidler continued, a number of other factors need to be considered in the choice of a work measurement technique. Some of the factors relate to the general atmosphere of the workplace. For example, he explained, the relationship between management and labor plays an important role in the choice of technique. If this relationship is tense, a stopwatch study or a predetermined time study will be difficult because of worker resistance, and conversation-based methods, such as judgment estimating, will be easier. Schmeidler noted that even under the best conditions, employees tend to dislike measurement processes and the implementation of measurement-based polices; he suggested that management persistence, coupled with slow and gradual change, can lessen the resistance when these techniques are chosen.

To choose the appropriate measurement technique, the precision and accuracy requirements of the client also have to be understood, as well as any tools that have been used in the past and the client’s belief system regarding which tools are the most accurate. Referring to the hierarchy of work (see Figure 2-2), Schmeidler explained that,

SOURCE: Schmeidler, N. (2019). Work Measurement Operations Research. Presentation for the Workshop on Resourcing, Workforce Modeling, and Staffing (slide #7). Reprinted with permission.

SOURCE: Schmeidler, N. (2019). Work Measurement Operations Research. Presentation for the Workshop on Resourcing, Workforce Modeling, and Staffing (slide #8). Reprinted with permission.

for the purpose of a staffing model, maintenance work should be measured at the level of end product or intermediate product because measurement at deeper levels could be cost-prohibitive, and higher levels are difficult to model. He further suggested that data be collected at least one level “deeper” than the level at which results are desired, so that the underlying data will be easily available if questions about those data arise during model creation.

Other factors that need to be considered in the choice of a work measurement technique concern the character of the work itself. For example, to accurately capture the work process, the business cycle must be fully understood,

so that the proper information is gathered during the appropriate time. Details of the task to be measured, such as duration and variability, need to be well understood. For maintenance tasks, some can take days to complete, and some may be interrupted for long periods if a part has to be ordered. Because completion times can be highly variable for such maintenance tasks, precise measurement methods, such as predetermined time study, stopwatch study, and work sampling, may not be cost-effective or resource appropriate. Other work-specific factors to consider in the choice of a measurement method are the availability of data, the number of work locations available for an appropriate sample, and the location of all work crew members, both on-site and remote.

Schmeidler noted that one of the questions posed to him by the committee concerned the costs and benefits of each of the measurement techniques. He said that he could not provide a quantitative comparison, and he offered some data from a survey on work measurement of the members of the Institute of Industrial Engineers in 2003. This survey showed that, in the private sector, the time study technique is used most frequently, more than 80 percent of the time. In terms of the benefit-to-cost ratio, he noted that almost 80 percent of the survey respondents reported a “payback” ratio of two to one or greater.

Schmeidler then discussed several conditions that contribute to the success of work measurement techniques. Foremost is the support of the executive leaders, management, and key stakeholders. Referring to the 2003 survey he had just mentioned, Schmeidler said that leadership was found to be the primary motivator for work measurement in the private sector, higher than market influences, clients, or regulations. This was true for both large and small employers. Another condition for success of work measurement is the involvement of qualified individuals in the development, execution, implementation, and maintenance of a work study. He emphasized that teams should include experienced industrial engineers who understand the process and have solid interpersonal, analytical, and presentation skills. Qualified teams are critical for many aspects of the work measurement process, including the choice of appropriate measurement techniques; the selection of a representative sample; proper data collection; and detailed data analysis, validation, and documentation. In response to one of the questions posed by the committee, Schmeidler stressed that work measurement techniques can accurately predict job completion time only if these conditions of success are met.

Schmeidler next discussed in detail the two analytical work measurement tools: historical data and judgment estimating. In response to one of the committee’s questions, on the validity of archival data as a predictor, Schmeidler answered that historical data can predict how long a task should take if a number of criteria are met. Those criteria include a high-performing workforce, good supervision, and a good work measurement system. In the absence of these criteria, he noted, the measurement will reflect a “does take” time, not a “should take” time. However, he said, even a “does take” time is a start, and, “if the system can’t do anything about ‘does take’ time, what’s the point in knowing that it could be 20 percent less? You’re going to have to factor it back in.”

Schmeidler next responded to the committee’s questions about the judgment estimating method of work measurement. He said he does not favor focus groups composed of subject-matter experts because they can easily be swayed or dominated by a single individual, but he does think that individual interviews of subject-matter experts can result in valid data points. He illustrated this approach with an example of work measurement he did for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The agency wanted a time standard for a long-duration, low-repetition task. Schmeidler used a technique documented by Mundell called fractioned professional estimate.6 In this technique, employees knowledgeable in the subject matter of the work describe the work using discrete steps, providing their estimates of the standard amount of time and the frequency of each step. Using this technique, a 1-hour employee interview resulted in 36 hours of labor data, which would have been extremely expensive to obtain with a time study. This example, said Schmeidler, makes the case that “a quick and dirty answer is probably pretty good. And you can always improve it once you get that reference point.”

To wrap up, Schmeidler provided several recommendations for the committee’s work. First, he suggested that the committee assess the VHA’s understanding of work measurement and, if necessary, advise the agency of the importance of such understanding before work measurement is undertaken. The VHA needs to understand that money and staffing will be required for the measurement and that the process will need to be maintained over time in order to remain effective. Schmeidler’s second recommendation to the committee was to conduct

___________________

6 Mundell, M.E., and Danner, D.L. (1994). Motion and Time Study: Improving Productivity, 7th Edition. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

a literature review, as is standard for any study, and he noted several key sources. Third, Schmeidler suggested that the committee visit and learn from the top 5 to 10 health care companies that have good outcomes and are financially successful. Schmeidler also recommended that the committee collect information about computerized maintenance management systems.

Workshop participants and committee members asked several questions related to the process of judgment estimating. Brian Norman (Compass Manpower Experts, LLC) addressed the drawbacks of using a focus group of subject-matter experts rather than interviewing them individually, acknowledging that one personality often drives the discussion while other participants become disengaged. He noted that he has used a hybrid strategy, in which individual interviews are first performed to collect data, which are used to generate box plots with standard deviations. These data are then used with a focus group that is asked about possible reasons for the outliers, providing a “fine tuning” of the team’s understanding of the dispersion. Schmeidler commented that 10 individual interviews allow the collection of 10 data points, from which an average can be calculated; in contrast, with a focus group of 10 people, it is unclear where each individual stands. He also cautioned that the presence of the supervisor during an interview can influence the responses given by employees.

Cheryl Paullin (committee member) stated that in the field of industrial organizational psychology, using subject-matter experts for estimating is often performed using surveys. The survey approach allows the collection of data from many individuals, making it more efficient than one-on-one interviews, but since surveys are filled out independently, it avoids the possible bias of a focus group. Schmeidler replied that he had not tried the survey approach, but that, in his opinion, the personal, participative nature of interviews can provide a lot of information in a short time and can often help with employees’ buy-in.

Colin Drury (committee cochair) asked Schmeidler how particular subject-matter experts are chosen for work measurement studies. Schmeidler responded that in most facilities the managers will easily be able to identify the employees who are most appropriate to study for this process.

Robert Anselmi (committee member) noted that the VHA has a great deal of variability in terms of its facilities, the skill sets of employees, and yearly project workloads, all of which affect staffing. He asked Schmeidler to address this issue of variability in terms of work measurement. Schmeidler acknowledged the challenge that such variability brings and that differences in work ethic between locations will add to that variability. He said that the VHA should decide up front what the “national standard” should be and then begin the process of slowly moving all facilities toward that standard.

David Alvarez (VHA) asked Schmeidler what risk-averse government agencies generally do with work measurement data: “What sort of decisions are they making, what are they trying to solve when you provide these studies to them?” Schmeidler responded that some organizations use the standards to measure individual performance, but there are some labor agreements that do not allow work measurement data to be used against an individual, so it is important to understand what the bargaining units and individual agreements will allow. In the private sector, he noted, performance data can ultimately be used to discharge underperforming employees, but this does not happen in the federal government, where work measurement data are often used to determine staffing needs from a budgeting standpoint. These figures become a reference point for the organization and for Congress.

In Schmeidler’s final recommendation to the committee, he strongly urged it to gain a full understanding of the overall situation for the VHA, in terms of funding, understanding the relationship between management and the bargaining units, and the commitment of management to the change process. He suggested that the committee’s future recommendations should be appropriate to the VHA’s situation because if they are not, or if the resources do not exist to support the recommendations, or if the end goal in the report is too far from the VHA’s starting point, then the recommendations will not be followed or will only be partly followed.

DISCUSSION OF MODELING

In this workshop session, Norman responded to questions generated by his earlier presentation and to the questions the committee had asked him to address, which were touched on in the course of the session:

How do any unique aspects of a health care organization affect the structure of the model? What factors do you consider in staffing modeling for health care facilities engineering? And, how do you relate model outputs to performance parameters that matter to stakeholders?

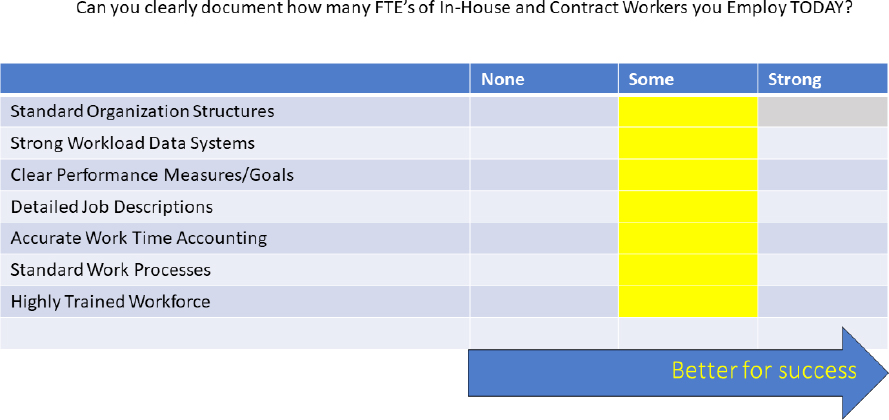

Norman opened the discussion session with a slide outlining conditions for a better model: see Figure 2-4. He acknowledged that budget pressures often do not allow for all these conditions to be met but emphasized that meeting them would greatly improve the success of any modeling effort. In addition to the need for a standard organizational structure, Norman stressed the value of strong workload data systems: “Having really good, verifiable, accurate data to work from just has tremendous power.” He also pointed out that as a modeler he spends a lot of time identifying the tasks and processes that need to be performed by each work center, stressing that documented performance goals not only set an organization up for measurement, but also allow a dashboard view of the organization’s workload, the health of the processes, and how workers’ time is spent. These two tasks alone—building a work center description and a list of “must-dos” and then deploying that list across the organization—can be of great help in terms of setting the stage for successful workforce modeling. Norman also noted the importance of standardizing work processes across locations and of implementing continuous process improvement methods.

In terms of the appropriate staffing necessary to collect quality manpower data, Robert Anselmi (committee member) began the discussion by noting that in many of the medical centers in which he has worked, there were no staff to oversee work orders in this way and, as a result, only the minimum amount of data were collected to keep the medical centers compliant with accreditation standards. Norman acknowledged this reality and stressed the importance of investing money up-front in the technology and the people needed to create a system for collecting good data. He emphasized the leverage that such data can bring to an organization in terms of strategic planning. Drury underscored Norman’s point: “You invest up-front. Even borrow the money to do it. And you get the rate of return. It is absolutely standard. I do not see why anyone objects to doing this.”

Following up on Drury’s point, Norman suggested that organizations may object to investing in facilities management because it is seen as a cost instead of a partner in the organization’s mission. He pointed out that the cost of not investing in these systems can be greater, in terms of lost billing time or even in terms of patient lives, than the cost of the investment. Oleh Kowalskyj (VHA) added to Norman’s assessment, noting that, when an organization’s leaders need to cut costs, they find it easier to cut employees who perform data collection than to cut electricians or plumbers. This choice, continued Kowalskyj, perpetuates the problem of poor data availability, quality, and validity. Norman agreed with Kowalskyj, cautioning that the VHA has peer competitors—both

SOURCE: Norman, B. (2019). Modeling Best Practices for the Future. Presentation for the Workshop on Resourcing, Workforce Modeling, and Staffing (slide #34). Reprinted with permission.

corporate and large nonprofit health care associations—that have robust systems in place to measure workforce data, transaction data, cost per procedure or output and more, which gives these organizations an advantage.

The discussion turned to considerations for applying staffing models in VHA facilities, given that the enterprise is inherently diverse, decentralized, and nonlinear. David Alvarez (VHA) raised several questions: “How do you apply something this granular to such an organization that is inherently decentralized? What is the measurement model? How do you approach something like that?”

Norman responded that the process should begin with a “tremendous baselining effort” to obtain a full understanding of the diversity across the entire VHA enterprise. The data from that baseline effort should then be compared with that of similar organizations, he said, or even with peer organizations that are not medically oriented: “Using internal and external benchmarking for getting that order of battle ready right now . . . could be very productive,” Norman said. Furthermore, such benchmarking will set the VHA up for a better chance for success with the subsequent modeling effort.

In terms of the inherent nonlinear character of the VHA, Wesley Harris (committee member) asked Norman how that should be accounted for in a staffing model. Norman acknowledged that in certain organizations with a high degree of nonlinearity, a linear model can sometimes be created that both the modeler and the customer believe is “good enough” in terms of the amount of risk assumed. However, Norman said, he recognizes that in other cases such risk is unacceptable, noting that “there are just certain things that cannot be wrong,” and in such cases more resources have to be invested to make the model extremely precise. He explained that modeling can sometimes accommodate diversity in an organization using “bolt-ons” or variances in a model, noting that the diversity of functions across the varied locations in the VHA could potentially be accommodated by a model in which some locations get extra, customized pieces along with the standard model framework.

In discussing the use of a single model or multiple models, Fred Switzer (committee member) asked: “Where is the sweet spot between fitting your data into a single model or going ahead and biting the bullet and using multiple models for different parts of the organization?” Norman replied that there is no rule of thumb and that every organization must be examined individually to determine what it can afford, the amount of coverage desired, and the level of integration needed. For example, he said, there are cases in which a single model will not work for a complex organization because too many assumptions must be made, resulting in the loss of fidelity of the model at the lower levels. In these cases, Norman said, he prefers a model made of smaller pieces that are easy to maintain and can be fed into a larger model.

James Smith (committee cochair) observed that much of the prior discussion was focused on the process of building a model when one does not exist. He asked Norman how he would determine the shortcomings of an existing model—whether the model is not sophisticated enough or whether the data being collected are not accurate enough to support the modeling goal. Norman replied that the health of a model can be diagnosed primarily through discussions with the organization, with questions about what types of models have been attempted, an analysis of those models, and how effective they have been. In his words: “A lot of brilliant people have had these same problems before. There is no doubt in my mind that there are brilliant people in the VHA world who have already dealt with these kinds of things and could give me an earful. That is what I would want; I would go out and get them.”

David Alvarez (VHA) asked whether the same staffing model could be used by various aspects of the organization for slightly different purposes, such as at the national level to forecast budgets, at the executive level to determine the amount of risk assumed, and at the facility manager level to determine staffing needs. Norman replied that this was in fact desirable, but it is only possible if the systems at each level are integrated to share data. In Norman’s words: “What you do is you take the model results. You publish that in this big thing that can be rolled up at installation level or local level up to your district, up to the federal level and say, ‘these are the total requirements. This is how many gapped. This is the risk we are taking, or this is the budget we need.’ . . . It is so tremendously powerful, because you can quantify what it is you need and not only by just gross numbers, but by skill, grade, or whatever. Now you can send your staffing teams to wherever it is that you need to recruit and get those filled up. It is a whole system.”

This page intentionally left blank.