6

Creating Healthy Living Conditions for Early Development

MEETING FUNDAMENTAL NEEDS TO SUPPORT PRENATAL AND EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT

I am trying to get gainful employment. . . . We all have that same thing in common of trying to do better for ourselves, trying to turn things around and do the right thing. But it’s hard, it’s hard because the resources that are available to us—we don’t know about them, we are not aware of them, we don’t know how to connect to the resources that are available to us. —Parent on caregiver panel1

As described in earlier chapters, a child’s most proximal influence in early development is the family unit, specifically the primary caregiver. Chapter 4 provides an overview of what children need from caregiver relationships and the critical role those relationships play for children to have the opportunity to flourish and thrive. However, these relationships do not exist in a vacuum, and neither do families—they are shaped by the social determinants of health (SDOH), as laid out in Chapter 3 (see also Figure 1-9). Families exist within the context of their communities, and all children need safe and healthy communities that promote optimal development. Healthy communities continuously create and improve physical and social environments and expand community resources that enable people to mutually support each other in daily life and in developing

___________________

1 This quote is from a public meeting of the committee, held on October 1, 2018. The meeting webcast is available at www.nationalacademies.org/earlydevelopment (accessed July 29, 2019).

to their maximum potential (CDC, 2009). Chapter 4 also makes the case that it is essential to mitigate caregiver stress so that caregivers have the capacity and supports to care for their children and to serve as buffers against adversities. (See Box 6-1 for an overview of this chapter. See Chapter 2 for a brief discussion of the biological mechanisms of buffering and Chapter 3 for discussion of the importance of stable and nurturing relationships.)

This chapter addresses the fundamental needs of families and children that are critical to achieving health and well-being. In the report conceptual framework (see Figure 1-9), these are the “healthy living conditions” situated in the second outermost circle, along with health systems and services (see Chapter 5) and early care and education (ECE) (see Chapter 7). Healthy living conditions are made up of the SDOH, or

more specifically, the social, economic, environmental, and cultural drivers of health and well-being. These determinants are interdependent, and together, they create conditions that influence child health and the ability of a caregiver to fulfill a child’s basic needs for healthy development.

Based on the core scientific findings in this report, this chapter seeks to address the challenges—for example, the barriers highlighted in the quote that opened this chapter—caregivers face with respect to securing economic stability and a safe and healthy living environment during the prenatal through early childhood periods. The committee reviewed promising community-level models and policy opportunities that focus on key neurobiological and socio-behavioral mechanisms needed for healthy development that yield the greatest impact to both mitigate and forestall the impacts of early life adversities on health.

Systems changes are needed to target multiple SDOH that shape early development and well-being. Systems that children interact with are most effective when they take into account developmental science and evidence when they are created, thereby meeting children’s developmental needs. There are changes that could be made based on this science to existing policies that would make them more responsive to the needs of children. The recommendations in this chapter aim to provide predictability and security in the lives of children and their families through ensuring economic stability and a healthy and safe living environment. While the chapter takes a social determinants approach to addressing early living conditions, it should be noted that there are some important contextual factors that are not discussed here. For example, research shows that factors such as public transit, access to parks and green space, and mass incarceration all shape inequities for children and families (see, for example, NASEM, 2017; Wildeman and Wang, 2017); however, these areas of programs, policies, and systems are not the focus of the solutions discussed in this report. The primary focus here is on the programs, policies, and systems changes that the committee has identified as having the most evidence and promise for improving health and wellbeing outcomes for children and their caregivers, in addition to reducing disparities. The chapter includes discussions of the existing evidence and committee recommendations for solutions to address economic stability and security, food security and nutrition, housing, neighborhood conditions, and environmental exposures and exposure to toxicants.

ECONOMIC STABILITY AND SECURITY

Children’s well-being and future health outcomes are strongly related to family income, and as the review in Chapter 3 shows, poverty is associated with significant detrimental effects on children’s health, development, and well-being. A systematic review of the literature concluded that the evidence supports the conclusion that the link between income and child outcomes is causal; that is, “money makes a difference in children’s outcomes” (Cooper and Stewart, 2013). The study also finds evidence that money in early childhood is important, particularly for cognitive outcomes. Thus, reductions in childhood experiences of poverty, and increasing the resources available to families to meet their basic needs, would be expected to improve children’s health and developmental outcomes.

Given the substantial evidence that money matters, an important factor in reducing health disparities in early childhood is to ensure that families with young children have sufficient resources. As the Council of Economic Advisers points out, current policies and public programs provide much less support for families when children are young compared to when they are school age, despite the needs and lower financial wherewithal, on average,

of families with younger children (CEA, 2014). In this section, the committee reviews the evidence about U.S. safety net programs that are intended to increase financial resources of families with children through cash transfers or tax credits. In the following paragraphs, the committee assesses programs that provide targeted benefits to address food or housing shortfalls and programs to address neighborhood conditions. To retain a reasonable scope, the focus is on the largest safety net programs run by federal and state governments that are offered to families with young children or pregnant women, while acknowledging that local governments, nonprofit organizations, and religious organizations also provide resources to help families in need.

Furthermore, the committee acknowledges the importance of providing parents and other caregivers with pathways to sustained economic security, such as educational opportunities and workforce development training. Chapter 3, for example, highlights the salience of parental educational attainment and household income as determinants of child health, wellbeing, and educational outcomes. Thus, an approach that enhances educational and economic opportunities and ultimately financial sustainability for caregivers would benefit children and families. Community-based programs that promote economic well-being for families are one promising avenue for advancing economic security. One such example is the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative’s Fair Chance for Family Success—funded by the Boston Promise Initiative in partnership with the Family Independence Initiative. This is a peer-to-peer financial literacy and learning program, which reports improved outcomes for participating families in terms of amount of money in savings accounts, checking accounts, total assets, and subsidy income (NASEM, 2017). Similarly, programs that enable workforce participation or retention could also help families get on a path to economic security. WorkAdvance is one program that allows employers to place individuals with moderate job skills into training programs for specific sectors that have high demand for local workers (NASEM, 2019). Evaluation data for this program suggested large increases in workforce participation, training completion, and credential acquisition at a 2-year follow-up (Hendra et al., 2016). While these types of programs are relevant to promoting healthy early development, the committee’s approach in this report was to limit its scope to program, practice, and policy changes that had the strongest evidence for direct impacts on children and their well-being. Therefore, the committee did not include in-depth discussion of these types of economic and workforce support programs for caregivers in this chapter.

Policies and programs aimed at reducing the impact of poverty on children’s health and well-being may provide cash benefits (directly, or indirectly through tax credits) or noncash or “in-kind” benefits, such as vouchers to buy food or housing. Alternatively, some programs directly provide food, housing, or education. This section first describes antipoverty programs designed to increase the level of (cash) resources families have,

focusing on the two largest direct cash grant programs, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and then on tax credits, focusing on the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credits (CTCs). Next, paid parental leave is discussed as another option for supporting families’ needs when children are young. The committee examined the evidence on the extent to which these programs (1) increase cash resources and thereby reduce poverty, (2) are associated with improved child health and development, including prenatal and birth outcomes, and (3) are associated with longer-term health,

educational, and economic outcomes. Throughout this section, the committee explores concerns about the strength of the evidence and the possibility of unintended consequences of these programs (which might directly or indirectly impact children’s health). The committee’s conclusions and recommendations build off those made in the National Academies report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty (NASEM, 2019), which provides a thorough analysis of the evidence for approaches to alleviate child poverty. Box 6-2 contains the conclusions from that report that are relevant to and informed this committee’s conclusions and recommendations.

Cash Assistance Programs (TANF, SSI)

TANF provides cash assistance and sometimes other supports, such as job search support or child care subsidies, for eligible families with dependent children. Because TANF is a block grant, each state establishes its own eligibility rules, determines the type and amount of assistance to be provided, and sets other requirements and services (within broad federal guidelines). TANF participation is time limited and is intended to promote economic self-sufficiency, work, and marriage (HHS, 2012). In fiscal year 2018, 1.2 million families and nearly 2.4 million children received TANF assistance on average each month (ACF Office of Family Assistance, 2019). TANF has been a shrinking component of the nation’s social safety net for children since the passage in 1996 of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, when Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) was replaced by TANF. In 1996, 68 percent of low-income families with children received cash assistance through AFDC. In contrast, only 23 percent received TANF cash assistance in 2016 (CBPP, 2018a). In addition to reaching fewer low-income families, the size of grants has fallen in inflation-adjusted terms in most states. TANF benefits for a family of three in the median state were $447 per month in 2018 and have fallen by 20 percent in inflation-adjusted terms since 1996 (CBPP, 2018a). Overall, TANF is much less effective at reducing the severity of poverty than was the AFDC program: 18 percent compared to 56 percent of children moved out of deep poverty after receiving TANF versus AFDC grants (CBPP, 2018a).

Additional sources of direct cash support for families include the SSI for children and U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) programs. Children “with physical or mental condition(s) that very seriously limit his or her activities” and that last for more than 1 year may qualify for SSI payments, which families can use to pay for basic needs, such as food and housing or medical care. To qualify, children need to meet the program’s definition of eligibility and the family needs to have limited income and resources. In May 2019, about 1.1 million children under age 18 received an average monthly SSI payment of $674 (SSA, 2019). Nearly half (45 percent) of low-income families with an SSI recipient were lifted out of poverty by receiving SSI, according to a 2015 National Academies report (NASEM, 2015). Another 4 million children receive benefits through the Social Security program as children of deceased workers (survivor benefits), children of workers with disabilities (through Disability Insurance), or children of retired workers. Summing across these groups, about $3.6 billion flowed to children through SSI and SSA programs (SSA, 2019). It is likely that the bulk of these monies goes to older children rather than those under age eight; nonetheless, for the

families receiving these payments, the increase in income helps them to meet basic needs.

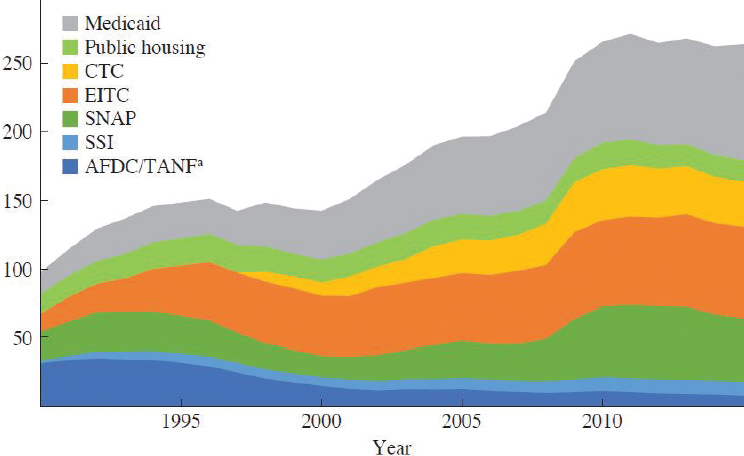

These programs (TANF, SSI, and SSA) all have the potential to improve children’s health by raising family incomes; however, eligibility is limited, and the size of the assistance provided, especially for TANF, has not kept pace with rising costs of basic needs, particularly of housing. In terms of federal expenditures, the $12 billion of TANF spending on children and $12 billion in SSI for children with disabilities are only a small portion of federal spending on children in low-income families (Hoynes and Schanzenbach, 2018; Isaacs et al., 2017b). See Figure 6-1 for a breakdown of government spending on children by program from 1990 to 2015. The 2019 National Academies report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty estimated that reductions in child poverty based on the current TANF program are small because of the low proportion of low-income children receiving TANF and the level of benefits. That report did not include expansion of TANF in the main strategies proposed to reduce

NOTE: AFDC = Aid to Families with Dependent Children; CTC = Child Tax Credit; EITC = Earned Income Tax Credit; SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; SSI = Supplemental Security Income; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

a AFDC became TANF after the 1996 welfare reform. Dollars reported in billions of 2015 dollars.

SOURCE: Hoynes and Schanzenbach, 2018.

child poverty, primarily due to the lack of evidence and the difficulties of assessing the effects of block grants on child outcomes when states have considerable flexibility in how the money is spent (NASEM, 2019). In contrast, they estimated that the child poverty rate (based on the supplemental poverty measure) would be 1.8 and 2.3 percentage points higher without SSI and SSA benefits, respectively (NASEM, 2019). While these programs (TANF, SSI, and SSA) provide some income support for young children, much more of the spending on children is through tax credits and in-kind assistance for food and housing, which we examine next.

Supporting Children Through Tax Credits

In contrast to cash assistance received on a monthly basis, tax credits represent an alternative financing mechanism for income support. When a family receives a tax credit, the taxes they owe to the government are reduced, and when the tax credit is “refundable,” the family receives a payment if the credit exceeds the tax owed. In theory, a tax credit can provide the same amount of income assistance to a family as a direct cash transfer, although in practice, the amount and timing of the payments differ between the two types of mechanisms. Economists generally regard tax credits as having advantages over direct cash transfers in terms of the ease of administering the program (less bureaucracy) and lesser stigma from participation (Nichols and Rothstein, 2016). However, the extra income from a tax credit or refund is typically available only once per year and only if the family files a tax return. The two primary tax credits that apply to U.S. families with young children are the EITC and the CTC, sometimes jointly referred to as working family tax credits. While this section’s focus is the federal level, many states offer similar tax credits to working families. In theory, working family tax credits avoid the potential work disincentives of cash transfer programs, and research has demonstrated large increases in labor force participation, particularly for single mothers with children, as a result of the EITC (Nichols and Rothstein, 2016).

The EITC provides a refundable tax credit to eligible families based on earnings, number of children, and marital status. Initially implemented in 1975, the EITC has seen its level and coverage expanded with bipartisan support several times over the past 45 years. The Internal Revenue Service and the U.S. Census Bureau estimate that nationally, between 77 and 80 percent of eligible families claimed the EITC in 2015 (IRS, 2019). Although the take-up rate is high, outreach campaigns and use of tax preparation services or software can help increase the proportion of eligible families who receive the tax credit (Goldin, 2018). In 2016, the average EITC received by families with children was close

to $3,200, which lifted an estimated 3 million children out of poverty and reduced the severity of poverty for nearly 7 million more children (CBPP, 2018c).

The CTC2 is structured similarly to the EITC as a tax credit that is (partially) refundable. Low- and moderate-income families can claim a tax credit for each of their children up to age 16. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2018 increased the CTC from $1,000 to $2,000 per child, with a maximum of $1,400 that is refundable. More than 90 percent of American families with children receive the CTC, and the average amount received in 2018 was $2,420 (per family) (TPC, n.d.). The average credit and share of families receiving the CTC is lower for families in the lowest income quintile because some of these families will not have enough earnings to qualify and the CTC is not fully refundable. Nonetheless, the estimated effect of the CTC on poverty is notable: the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that the CTC lifted about 1.6 million children out of poverty and reduced the severity of poverty for 6.7 million children in 2017 (CBPP, 2018b). Most families in the second, third, and fourth income quintiles receive the CTC, while those in the lowest bracket benefit less (TPC, n.d.). The boost of $1,000–$2,000 in the CTC is due to expire in 2025 (TPC, n.d.).

There is extensive research on the effects of the EITC on labor force participation (particularly of single mothers) and on health and educational outcomes for children in the United States. Less research has been conducted on the effects of the CTC, mostly because it was relatively small until recently. Given the similar structure of the CTC and EITC, many of the effects are expected to be the same, with the important exception that the CTC is available to most moderate-income families, unlike the EITC, which is targeted at families with low incomes.

As noted above, the EITC and the CTC together are effective in reducing child poverty: nearly 5 million children lived in families whose incomes were brought above the poverty level after including working family tax credits, and more than 7 million additional children experienced less severe poverty (CBPP, 2018c).3 The poverty rate for children under 18 falls about 6 percentage points with the tax credits (16.4 percent compared to 22.8 percent without them) (Nichols and Rothstein, 2016). The reductions in child poverty are larger for these tax credits than other means-tested programs in the United States (Nichols and Rothstein, 2016). Given the well-established link between family income and health outcomes, by

___________________

2 The refundable portion of the CTC is called the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC); here, both the ACTC and the CTC are included when referring to the CTC.

3 Note that these estimates are based on data using the U.S. Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure.

increasing family incomes, these tax credits are likely to lead to improved child health. One advantage of studying the link between the EITC and outcomes is that researchers can use exogenous policy changes that increase families’ income, avoiding the problem of endogenous income in studies of income–health links (Boyd-Swan et al., 2013).

While most studies have focused on the impacts of the EITC on labor force participation or reductions in poverty, a small but growing number of studies have examined the impacts of the EITC on health and education outcomes of children, both short and long term. Several studies found the EITC associated with higher birth weights and/or a reduction in the incidence of low birth weight (LBW) (Baker, 2008; Hoynes et al., 2012; Komro et al., 2019; Strully et al., 2010). Using quasi-experimental methods, Hoynes et al. (2012) estimated a decline of 2–3 percent in LBW occurrence for a $1,000 increase in the EITC, with larger effects for black than white women (among single women with a high school education or less). This study and one by Strully et al. (2010) also link EITC receipt with reduced rates of maternal smoking. In contrast, Baughman and Duchovny (2016) found that EITC receipt was not associated with improvements in parent-reported health status of children age birth to 5, although there were improvements for older children (age 6 to 14). Evidence linking the EITC to child cognitive or child development outcomes is limited (particularly for younger children). One study by Hamad and Rehkopf (2016) used an instrumental variable approach to estimate the impact of the EITC on child development. They found “modest but meaningful improvements” in child behavior and home environments. The article notes that one mechanism through which the EITC impacts child development is through improved mental health of mothers (Evans and Garthwaite, 2010) and that it may lead to reductions in maltreatment (Berger et al., 2017). Studies focused on older children also find positive associations with EITC receipt on test scores (Chetty et al., 2011; Dahl and Lochner, 2012) and college attendance (Manoli and Turner, 2018).

It is important to note that effects of the EITC on health outcomes may be a result of the increase in family income; however, the EITC also strongly impacts work incentives, and impacts on child health and development may be due to changes in parent employment. Increases in maternal employment may increase the family’s income but also reduce the amount of time mothers spend with their children. How these changes impact children’s health and development likely depends on the quality of nonparental child care used and the stress experienced by parents, in addition to income changes (Hoynes and Schanzenbach, 2018).

Unlike the working family tax credits, minimum-wage policies are not targeted specifically at low-income families with children.

Nonetheless, some economists argue that minimum-wage policies play an important and complementary role in reducing child poverty along with the EITC (Nichols and Rothstein, 2016). Research summarized by Nichols and Rothstein (2016) has demonstrated that the EITC provides a strong incentive for single mothers to work and has been a major factor underlying the rise in labor force participation of single mothers over the past two decades. An increase in the supply of labor, holding all else equal, could put downward pressure on wages, and the minimum wage provides a floor to keep wages from declining (Nichols and Rothstein, 2016). Parents who earn low wages benefit from a higher minimum wage in every paycheck along with receiving the tax credit when they file a tax return (CBPP, 2018c). A small number of studies also link increases in the minimum wage with health outcomes, though few examine children’s health or birth outcomes. Two studies find small improvements in birth weight outcomes related to minimum-wage increases across states over time using quasi-experimental methods (Komro et al., 2016; Wehby et al., 2016). One study also found reductions in child maltreatment associated with higher minimum wages (Raissian and Bullinger, 2017). Given the evidence linking improved child health to higher family incomes, more research on the health effects of minimum-wage increases is needed to inform the policy debate.

Child Allowances

Many wealthy countries provide support to families through a child allowance or child benefit, which may be a cash grant or through the tax code. In the current U.S. tax code, the CTC and dependent child exemption act in many ways like a child allowance. The taxable income of families with dependent children is reduced, resulting in greater disposable income to meet the costs of raising children. A child allowance, distributed monthly, has two main advantages over the tax code approach. First, it helps families with short-term needs for cash to meet expenses, compared to a once-per-year distribution through the tax system. Second, the lowest-income families often cannot take full advantage of tax credits and exemptions if their income is so low that they do not owe income tax. A child allowance paid to families on a monthly basis and not tied to earnings or employment would provide support for many of the lowest-income children in the United States whose parents do not work or have unstable and insufficient earnings.

A number of child allowance proposals have been proposed in recent years (NASEM, 2019; Shaefer et al., 2018). Schaefer et al. (2018) proposed

a universal child allowance of $250 per child per month, possibly offering $300 for children under age 6 and slightly less for each additional child. Schaefer et al. (2018) noted that while this amount would not come close to covering the full cost of raising a child, based on their review of the research, it is large enough to have a meaningful impact on families and children and is comparable to child allowances in other countries. The National Academies report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty considered two options for a child allowance: about $2,000 and $3,000 per year. The reductions in child poverty are larger for these two policies than any of the other individual policy changes considered by the report (although the costs are also higher).

A few key principles are important when considering the parameters of a child allowance that is intended to improve health outcomes for young children. First, targeting payments to families with the youngest children acknowledges that families with younger children have lower incomes on average than families with older children (see Schaefer et al., 2018). In addition, some costs (particularly child care) are higher for younger than for older children. The nation provides sizable public resources to children starting at about age 5 when they enter the public K–12 education system. A child allowance targeted at children under age 5 would help to balance public investments in different age groups.

A universal program—in which all families with young children receive a child allowance—would reduce the stigma of participation relative to a means-tested program and may enhance social inclusion (NASEM, 2019, p. 148). While the costs of a universal program may exceed those of a targeted one, treating the allowance as taxable income would reduce the overall cost to the government. Alternatively, the child allowance could be phased out at 300 percent of the federal poverty level. Replacement of the current child tax credits with a monthly child allowance could provide families with a more regular source of cash income to support their children’s needs (NASEM, 2019). Determining the specifics of a child allowance policy and funding mechanism requires additional research and modeling to compare the potential impacts on child health and health equity. In sum, based on the committee’s review of the evidence and in accordance with the report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, there is strong evidence that programs that provide direct income transfers or basic necessities such as food and housing lead to improvements in child health and well-being (NASEM, 2019, p. 89). At the end of the chapter, the committee recommends expanding resources to support families with young children, with a child allowance as one important option to consider.

Paid Parental Leave

Maternal and paternal leave policies are generally intended to support mothers in recovering from childbirth and mothers and fathers in taking time off work to care for new infants. The United States remains one of the very few countries without a national paid guaranteed maternity leave policy. Across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, on average, mothers are entitled to 18 weeks of paid maternity leave (OECD, 2017). Although the United States is the only OECD country without a national-level policy of paid leave, California, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Washington, Washington, DC, and, most recently, Massachusetts have passed legislation to implement paid leave at the state and local levels (Mass.gov, 2019; Raub et al., 2018). See Box 6-3 for more information on California as an example of a state that has implemented a paid leave policy. A number of studies of paid maternity leave have found positive health effects, particularly lower infant and child mortality (Heymann et al., 2011; Nandi et al., 2018). Stearns (2015) estimated that paid maternity leave through temporary disability insurance in the United States reduced LBW by 3.2 percent and early births by 6.6 percent, with larger effects for certain subgroups, including black and unmarried mothers (Stearns, 2015). While improved maternal and child outcomes have been associated with paid leave policies in other countries, a review by Almond et al. (2018) showed mixed findings on child health impacts across studies, depending in part on the length of the leave. They concluded that “facilitating short maternity leaves is highly beneficial, but extended maternity leaves do not have a positive effect” on child outcomes (Almond et al., 2018, p. 1406). Rossin-Slater (2011) estimated that the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), which allows for 12 weeks of unpaid maternity leave, resulted in lower infant mortality and slightly higher birth weight outcomes for college-educated women. Overall, however, based on her review of the literature, Rossin-Slater stated that “while extensions in existing paid leave policies have had little impact on children’s well-being, the evidence suggests that the introduction of short paid and unpaid leave programs can improve children’s short- and long-term outcomes” (Rossin-Slater, 2011, p. 17).

Maternity leave policies have also been associated with higher rates of breastfeeding. As discussed in Chapter 3, breastfeeding provides important nutrition for developing infant brains and bodies; however, rates of exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (as recommended by the World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP]) are low in the United States, especially among black women. Furthermore, the majority of mothers in the United States are not breastfeeding as long as they had planned (Mirkovic et al., 2014; Office of the Surgeon

General et al., 2011). While the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has some protections for mothers who need to express milk while at work4 (a critical component of successful breastfeeding for working mothers), many mothers are not given the time, appropriate space, and support needed to do so when in low-paying jobs (Murtagh and

___________________

4 For example, the ACA updated the Fair Labor Standards Act to require U.S. firms with 50 or more employees to provide breastfeeding mothers with reasonable break time and space to express milk (DOL, 2018).

Moulton, 2011; Office of the Surgeon General et al., 2011). In a survey conducted by Declercq et al. (2013), 58 percent of women reported breastfeeding to be a challenge once they returned to work.

Paid leave “facilitates the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding” (Heymann et al., 2013). For example, a rigorous quasi-experimental study in California found that access to paid leave was associated with increased rates of exclusive and overall breastfeeding during the first 3, 6, and 9 months after birth (Huang and Yang, 2015). Studies (in both the United States and other developed countries) have found associations between maternity leave lasting at least 8 weeks and a higher probability of establishing breastfeeding (Guendelman et al., 2009; Ogbuanu et al., 2011; Skafida, 2012). Paid parental leave is hypothesized to increase mother–child attachment and give new mothers increased time to gain the skills and social support needed to maintain breastfeeding before returning to work.

The AEI-Brookings Working Group on Paid Family Leave published two reports in 2017 and 2018 that focused on paid parental leave and paid family care and medical leave, respectively. Based on the extant literature on paid parental leave and its impact on family outcomes, the 2017 report puts forth a federal paid parental leave proposal. In addition to physical health and cognitive outcomes for children, the report cites improved labor force participation as a positive outcome associated with paid leave. For example, California and New Jersey’s paid leave policies saw increases in labor force attachment among women in the months surrounding childbirth (Byker, 2016). This is important because continued workforce participation can help sustain household income and individual income, as well as other economic indicators that have been linked to health and well-being (see, for example, NASEM, 2017; Woolf et al., 2015). The key elements of the AEI-Brookings federal paid leave proposal are making benefits available to both mothers and fathers, wage replacement of 70 percent up to a maximum limit of $600 per week for 8 weeks, and job protection for the individuals who take leave. The authors also suggest that such a federal paid leave program could be financed by a payroll tax levied on employees and/or savings in other areas of the budget (e.g., reduced tax expenditures in areas such as unemployment insurance or Social Security and disability programs) (AEI-Brookings Working Group on Paid Family Leave, 2017).

Summary and Conclusions

There is considerable evidence that “income matters” for health outcomes, especially in early childhood. The report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty concludes that “the weight of the causal evidence does

indeed indicate that income poverty itself causes negative child outcomes, especially when poverty occurs in early childhood or persists throughout a large portion of childhood” (NASEM, 2019, p. 2). There is also strong evidence that the reverse is true: increasing family resources to meet basic needs supports the health and development of young children. Given the high rate of child poverty in this country compared to other wealthy nations, as well as large disparities across racial and ethnic groups in poverty rates, reducing childhood poverty is a critical, foundational step in reducing health disparities in early childhood.

One way to increase the resources families have for basic needs is through social insurance and safety net programs that provide cash or tax credits to families. Studies demonstrate improved health outcomes when families receive assistance through government programs, such as the EITC and SSI. These programs are associated with improved birth, health, and educational outcomes for young children, which will set them on a better trajectory for lifelong health and well-being.

Much of the support provided to families with children in the United States is in the form of “work supports,” where eligibility and the level of benefits are closely tied to employment and earnings. These policies help to reduce poverty by both increasing resources and encouraging employment (which also can lead to higher family income in the future). However, the report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty determined that a work-oriented package of programs and policies would be the least effective of the four packages they considered in reducing the number of children in poverty (see Table 6-1 for a summary of the components of each of the four packages). That report also concluded that mandatory “work requirements are at least as likely to increase as decrease poverty” (NASEM, 2019) (see Box 6-2).

In addition to a limited impact on reducing child poverty, further expansions of the work-oriented safety net programs may have unintended negative consequences for child health if parent employment results in

TABLE 6-1 Components of the Four Packages and Their Estimated Costs and Impact on Poverty Reduction and Employment Change from A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty

| 1. Work-oriented package | 2. Work-based and universal support package | 3. Means-tested supports and work package | 4. Universal supports and work package | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work-oriented programs and policy | Expand EITC | X | X | X | X |

| Expand Child Care Tax Credit | X | X | X | X | |

| Increase the minimum wage | X | X | |||

| Roll out WorkAdvance | X | ||||

| Income support-oriented programs and policies | Expand housing voucher program | X | |||

| Expand SNAP benefits | X | ||||

| Begin a child allowance | X | X | |||

| Begin child support assurance | X | ||||

| Eliminate 1996 immigration eligibility restrictions | X | ||||

| Percent reduction in the number of poor children | −18.8% | −35.6% | −50.7% | −52.3% | |

| Percent reduction in the number of children in deep poverty | −19.3% | −41.3% | −51.7% | −55.1% | |

| Change in number of low-income workers | +1,003,000 | +568,000 | +404,000 | +611,000 | |

| Annual cost, in billions | $8.7 | $44.5 | $90.7 | $108.8 | |

SOURCE: NASEM, 2019.

lower rates of breastfeeding or disruptions to the attachment between infant and caregiver. Evidence of the importance of attachment and breastfeeding is discussed in Chapters 3 and 4. Work-oriented programs, such as the EITC, that increase families’ incomes and increase employment are an important component of the social safety net. However, additional support for families with young children through paid parental leave or

a child allowance that is not tied to parent employment would recognize the special needs of the earliest years in which parent time and attention are critically important for children’s health and development. Both paid parental leave and income support, such as a child allowance not tied to employment, may provide parents with greater opportunity to take time out of the labor force to attend to their children’s needs.

As noted above, additional income support for families with young children through paid parental leave would recognize the special needs of infants and their caregivers. Unpaid parental leave through FMLA does not cover all employees, and many families with low incomes are unable to afford to take an unpaid leave. Paid parental leave grants parents greater opportunity to take time out of the labor force to attend to their children’s needs. Short, paid parental leave programs have been associated with positive health outcomes and higher rates of breastfeeding.

As of 2019, six states and Washington, DC, have paid leave programs, and the programs are financed through employee payroll taxes (AEI-Brookings Working Group on Paid Family Leave, 2017). Some proposals for paid family leave (PFL) follow a social insurance model in which employees contribute through payroll taxes to a government-administered social insurance fund. Other financing options include an employer mandate, tax credits to encourage employers, or general funds (Isaacs et al., 2017a). Because there are a variety of options to implement, structure, and administer a paid leave policy, cost estimates for this program vary widely. In its 2018 report, the AEI-Brookings Working Group on Paid Family Leave offered three methods for assessing the

cost of a hypothetical 8-week paid family medical leave program5 had it been operational in 2016. The three methods use (1) national-level data, assuming uptake would be similar to private-sector participation under FMLA; (2) state paid leave data, assuming participation would mirror the rates of the states with operational programs; and (3) a simulation model to combine national- and state-level data. Because these methods differ with respect to data sources and assumptions on program use, the cost estimates vary widely and drawing comparisons can be difficult. Based on their analyses, the authors estimate that the program could be expected to cost from 0.10 percent of total wages or $7.65 million total benefits paid (based on New Jersey’s state paid leave program) to 0.61 percent of total wages or $46.3 million total benefits paid (based on the FMLA national survey).

The committee did not study in depth other income-enhancement strategies to boost family resources that are not targeted particularly to health outcomes or early childhood, but these may be important for supporting the health and well-being of families and children. The National Academies report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty details a number of additional strategies to reduce child poverty through, for example, increases in the minimum wage, job training programs, child care subsidies, and child support assurance, in addition to the policies discussed in this section. There is limited evidence of the impacts of these on child health, with the exception of the minimum wage (discussed earlier). The National Academies report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty provides a careful assessment of a set of feasible strategies that could be used to reduce child poverty by half within 10 years (see Table 6-1). As discussed in Chapter 2, the scientific evidence amassed since From Neurons to Neighborhoods has established that access to basic resources prenatally and in early childhood impact the developing child’s brain and nervous system, immune function, and other organs (NRC and IOM, 2000). The toxic stress response of children living in poverty directly impacts behavioral and psychological well-being and substantially increases later-life risk for poor health and educational outcomes. Thus, reducing child poverty is a critically important, foundational strategy for improving child health outcomes and reducing health disparities in early childhood. Expansion of income-support programs that are not tied directly to parent earnings is likely to help those who need it most: children in deep poverty and the youngest children. Determining the specifics of a child allowance policy and funding mechanism requires additional

___________________

5 The hypothetical program provides universal access to up to 8 weeks of family and medical leave, including parental leave, with benefits paid at 70 percent of usual weekly wages up to a cap of $600 per week.

research and modeling to compare the potential impacts on child health and health equity. At the end of the chapter, the committee recommends expanding programs to increase economic resources to support families with young children, with a child allowance as one important option to consider.

Policies that build family assets and wealth also deserve consideration in developing a national strategy to ensure that all children have an equal opportunity to reach their full health and developmental potential. Individual Development Accounts and child savings accounts, for example, are typically targeted toward building savings for home ownership or postsecondary education. These strategies may have longer-term impacts on child and family well-being. Increasing education levels, particularly of mothers, also would likely lead to improved economic security for families. These policies support the broader goal of human capital development and long-term economic growth.

FOOD SECURITY AND NUTRITION

As described in Chapter 3, adequate and nutritious food is critically important for health outcomes during the preconception, prenatal, and early childhood periods. At times, adequacy of specific nutrients is crucial, such as folic acid during pregnancy. In each of these developmental periods, the overall adequacy and healthiness of food intake influence current health and development and have effects lasting into adulthood. Furthermore, food insecurity may affect both children and parents through changes in eating habits and stress related to uncertainty and inadequacy of food availability. The neurobiological (and other) mechanisms underlying these effects were described in Chapters 2 and 3. In this section, we look at the programs and policies in the United States aimed at reducing food insecurity and improving nutrition and healthy eating, with a focus on the prenatal and early childhood periods.

Current Programs and Policies

Two major federal programs in the United States target the adequacy of food and nutrition for children living in households with limited resources: the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as the Food Stamp Program, and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). In this section we examine the evidence on the effects of these two programs on children’s health and development. Note that programs that operate primarily in schools and early education settings, such as the National School Lunch and Breakfast Program, are discussed in Chapter 7.

SNAP

SNAP provides assistance to eligible individuals and families to purchase food. Participants use an Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) card that functions like a debit card to purchase food from authorized retailers, which include supermarkets, grocery and convenience stores, and farmers’ markets (CBPP, n.d.). Many participants enroll in SNAP for a short time—from 2009 to 2012, approximately 48 percent of participants received benefits for 24 months or less (Irving and Loveless, 2015; RWJF, 2018).

Participants need to meet requirements regarding income (gross6 and net7 monthly income), resources (such as cash, money in checking and savings accounts, and vehicles), and nonfinancial standards to be eligible to receive SNAP benefits (Cronquist and Lauffer, 2019). Undocumented noncitizens of the United States are not eligible for SNAP, but noncitizens who have lived in the United States for at least 5 years, receive disability-related assistance, or are less than 18 years of age are eligible (if they also meet the aforementioned income, resource, and nonfinancial eligibility requirements) (USDA, 2018b). The program expects that participating households will spend about 30 percent of their own financial resources purchasing food; thus, the amount in SNAP benefits received by each participating household is calculated by multiplying the household’s net monthly income by 0.3 and subtracting the result from the maximum monthly allotment8 for the household size.

Each month of fiscal year 2017, SNAP served 42.1 million individuals in 20.8 million households. Children were 44 percent of SNAP participants and received 43 percent of SNAP benefits. On average, the program provided assistance to 8.6 million households with children (42 percent of all households served by SNAP) each month. Of the total number of SNAP participants, 8 percent were children with U.S. citizen status living with noncitizen adults (Cronquist and Lauffer, 2019).

While SNAP benefits can be spent only on eligible food items, these benefits add to the total resources the family has to spend on all necessities. The average monthly benefit of $255 per household “represents a sizable income transfer to participants, and is expected to change the amount or quality of food purchased” (Hoynes and Schanzenbach, 2018, p. 13). A recent Urban Institute report estimates that the SNAP program reduced the number of children living in poverty by more than

___________________

6 Includes a household’s total, nonexcluded income before any deductions have been made (USDA, 2018b).

7 Gross income minus allowable deductions (USDA, 2018b).

8 Maximum monthly allotments by household size are available at https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligibility (accessed March 28, 2019).

one-quarter and the number in deep poverty by nearly half (Wheaton and Tran, 2018). The report also found that SNAP reduced the poverty gap (defined as the additional income needed to lift all low-income families out of poverty) by 37 percent for families with children. Given the evidence on the links between health outcomes and income, one would expect these sizable reductions in poverty to lead to improved health outcomes. A growing body of evidence shows that SNAP improves birth outcomes (Almond et al., 2011; East, 2018), although, as discussed below, relatively few studies focus on the effects of SNAP on the health outcomes of young children.

A review of studies prior to 2003 concluded that SNAP participation increased household food expenditures (USDA, 2004), which suggests that SNAP would reduce food insecurity among recipient households. Because families experiencing greater hardship are more likely to participate in SNAP, however, some studies of SNAP’s effect on food insecurity have found mixed and null results (Gibson-Davis and Foster, 2006; Gundersen and Oliveira, 2001; Huffman and Jensen, 2008; Wilde, 2007; Wilde and Nord, 2005). Gregory et al. (2016) illustrate how estimates of the relationship between SNAP participation and food insecurity vary depending on statistical methods, demonstrating positive and negative estimates along with ones that were not significantly different from zero. They did conclude, however, that food insecurity was reduced by SNAP in a dose–response type model. Furthermore, according to an Urban Institute report, “controlling for selection into SNAP is important for disentangling the effect of SNAP receipt on food insecurity” (Ratcliffe and McKernan, 2010, p. 14). The authors found that the relationship between SNAP participation and food insecurity changed direction when they controlled for selection into SNAP using an instrumental variables approach. They concluded that SNAP participation reduced food insecurity by 16 percentage points (results for children not reported separately). Using methods to account for both selection and measurement error in reporting SNAP participation, Kreider et al. (2012) found a reduction of at least 8 percentage points in food insecurity for children, depending on the model assumptions. Deb and Gregory (2018) found that the effects of SNAP on food insecurity vary across the population; while it may have no effect for some, for those starting with low food security, it resulted in a much lower likelihood of food insecurity.

While SNAP increases household resources and reduces food insecurity for (at least) some families, studies of the impact of receiving food assistance on children’s health outcomes are relatively rare. One study found that the introduction of the Food Stamp Program in California was associated with a reduction in infant birth weight, particularly among first-time teen mothers for whom birth rates increased overall

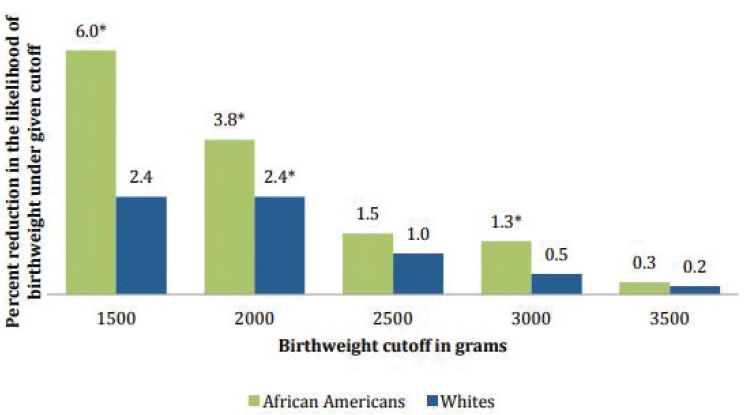

(Currie and Moretti, 2008). Potential mechanisms for this association could be related to fertility changes or the increased survival of LBW babies. The study findings also showed a small reduction in infant mortality for white babies in Los Angeles County. There is more recent evidence of a positive connection between receiving SNAP benefits (or food stamps) and improved birth outcomes. Almond et al. (2011) and East (2018) both found positive associations between food assistance during pregnancy and improved birth outcomes, using quasi-experimental methods. Almond et al. (2011) found larger improvements in birth weight outcomes for African American mothers and those living in high-poverty areas. They noted that these results occurred despite the fact that the Food Stamp Program was not designed to target pregnant women. See Figure 6-2 for data on the impact of in-utero exposures to food stamps on likelihood of birth weight below selected cut-offs.

With respect to other health outcomes for children, there is limited causal evidence. Kreider et al. (2012) reported improvements in child health outcomes (along with reductions in child food insecurity); however, the range of possible effect sizes is large. They accounted for both selection and underreporting of SNAP participation but did not specifically focus on young children. Most studies focus on adult health outcomes and found mixed results for adults (Kreider et al., 2012; see, for example,

NOTES: * Denotes estimate statistically significantly different from zero. Data from Almond et al., 2011.

SOURCE: Hoynes and Schanzenbach, 2016.

Gregory and Deb, 2015; Yen et al., 2012). Overall, there is limited evidence on the causal effects of SNAP on children’s health because there have been few opportunities for random assignment9 or limited variation in policies over time or in different places to exploit with experimental or quasi-experimental methods (East, 2018).

While studies of direct or contemporaneous effects on children’s health are limited, one recent study demonstrated a link between receipt of SNAP in childhood and adult health outcomes. Hoynes et al. (2016) found that adult health measured by the metabolic syndrome index was significantly better for those whose childhood families had access to food stamps, particularly in early childhood (before age 5). Long-term positive health effects of SNAP—that is, adult health outcomes for those receiving SNAP as children—are consistent with short-term health improvements during childhood. Similarly, East (2018) found positive effects of SNAP participation before age 5 on health outcomes when children were age 6–16, using quasi-experimental methods for a sample of children born in the United States to immigrant parents. While conclusions about the immediate impacts of SNAP on young children’s health are provisional given the methodological challenges of estimating causality (Carlson and Keith-Jennings, 2018), the evidence of SNAP impacts on reduced food insecurity and later health outcomes suggests that children benefit in both the short and long run.

One of the concerns about the SNAP program has been the potential linkage between SNAP benefits and obesity, in both adults and children. Earlier studies that did not adequately control for selection into SNAP found positive correlations between SNAP and obesity, while other studies found reductions in obesity or no effects (Fan and Jin, 2015; Kreider et al., 2012). Myerhoefer and Yang concluded “the balance of evidence points to a small positive impact of SNAP participation on obesity for women” but that the results for “childhood obesity are less consistent” (Meyerhoefer and Yang, 2011, p. 313). For children, Kreider et al. (2012) concluded that the obesity rate was 5.3 percentage points lower due to SNAP.

In addition to reducing hunger and food insecurity, a second key objective of the nation’s food assistance programs is to improve the healthfulness of American food consumption and provide nutrition education. Studies have examined the effect of SNAP on the quality or healthfulness of a family’s food consumption as a possible mechanism through which SNAP might affect obesity (and other health) outcomes.

___________________

9 Random assignment demonstration projects have been conducted recently and are under way in several sites as part of the Demonstration Projects to End Childhood Hunger project and the Healthy Incentives Pilot (Olsho et al., 2017; USDA, 2018a).

Most studies have focused on adult food intake, but Yen (2010) found no effect of the SNAP program on young children’s nutrient intake. A number of demonstration projects have been conducted to evaluate ways to incentivize or influence consumption of healthful foods through SNAP. The Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP) project provided a 30 percent rebate on purchases of a specified set of fruits and vegetables using SNAP benefits. Households receiving SNAP were randomly assigned to receive the rebate or not. The HIP evaluation reported that households receiving the rebates increased consumption of targeted fruits and vegetables by 26 percent, although some reported confusion and misunderstanding about how the rebate program worked and which vegetables and fruits were included (Olsho et al., 2017). The Summer EBT for Children pilot also was a random assignment design, but rather than targeting specific purchases, participants were provided with (an extra) $60 per month per school-age child. The evaluation study found modest improvements in several child nutritional outcomes and null effects for others (Collins and Klerman, 2017) even though this program did not specifically target or incentivize healthful food purchases. While SNAP benefits can be used to purchase almost any food item from participating retailers, recent pilot projects found that increased benefits and incentives for purchasing specific healthful foods can modestly impact some health-related and dietary outcomes. Proposals to restrict SNAP purchases to prohibit less healthful foods, such as sugary beverages, or to incentivize purchases of fruits and vegetables are highly controversial (Schwartz, 2017).

In summary, as discussed throughout this section, food assistance provided through SNAP is a major component of the nation’s social safety net and reduces poverty and food insecurity for millions of families and children (Carlson and Keith-Jennings, 2018). While the evidence of SNAP’s direct impact on children’s health is limited, Hoynes et al. (2016) found that adults who received SNAP as children experienced a reduction of 5 percent in heart disease and 16 percent reduction in obesity. Improvements in adult health outcomes related to receipt of SNAP in early childhood suggest that children are benefiting as well. Based on Hoynes and Schanzenbach’s (2018) summary of the literature examining links between SNAP participation and health outcomes, the National Academies (2019) report on reducing child poverty concluded that “many (but not all) of the methodologically strongest studies show SNAP benefits having positive impacts on health” (NASEM, 2019, p. 83). The report cites evidence that increasing SNAP benefits would substantially reduce child poverty and that current benefit levels do not account for food preparation time or geographic variation in food costs (Ziliak, 2016). Based on the evidence demonstrating the links between child health and family income or

resources, increasing SNAP benefits would likely lead to improved child health and reduced health disparities.

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

WIC provides assistance through breastfeeding support and education, healthy foods, nutrition education and counseling, screening referrals to other services, and vouchers to purchase fruits and vegetables from authorized farmers’ markets (USDA, 2015). WIC services are provided in many locations, including county health departments, hospitals, mobile clinics, community centers, schools, public housing sites, migrant health centers and camps, and Indian Health Service facilities (USDA, n.d.).

To be eligible to receive benefits, WIC participants need to meet all four categories of requirements: categorical, residential, income, and nutrition risk (USDA, 2018c). Infants younger than 1 year; children younger than 5 years; and women who are pregnant, postpartum (up to 6 months), or breastfeeding meet the WIC categorical requirement. To meet the residential requirement, participants need to reside in the state or local service area in which they apply but are not required to have lived in that area for a minimum amount of time. Participants also have to earn incomes at or below income standards that are set by state agencies, and fall within 100 and 185 percent of the federal poverty guidelines issued annually by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Lastly, participants need to be determined by a health professional to have at least one medical (e.g., anemia, underweight) or dietary (e.g., poor diet) condition from a list of conditions indicating nutrition risk that is set by states (USDA, 2018c).

In fiscal year 2018, WIC served approximately 6.9 million people and cost the federal government about $5.3 billion (USDA, 2019). In 2016, it was estimated that 64 percent of individuals eligible to receive WIC benefits were children ages 1–4, 21 percent were pregnant and postpartum women, and 16 percent were infants for a total of 13.9 million individuals. Of these, 7.6 million (55 percent) received WIC benefits, with 86 percent of eligible infants receiving benefits but only 44 percent of children ages 1–4 receiving them (Trippe et al., 2019).

Numerous studies using varied methods have found evidence of improved birth outcomes for women participating in the WIC program (see, for example, Figlio et al., 2009; Fingar et al., 2017; Foster et al., 2010; Hoynes et al., 2011). These studies find reductions in the likelihood of LBW (Figlio et al., 2009; Hoynes et al., 2011) and reductions in infant mortality (Khanani et al., 2010). Figlio et al. (2009) studied the effect of WIC in Florida between 1997 and 2001 by matching infant birth records with school records for older siblings to identify those who were

marginally eligible and marginally ineligible in order to form groups for comparison. They estimated a significant reduction in the likelihood of LBW among WIC participants, although there was no significant effect on average birth weight or gestational age. Studies generally have found that the effects of WIC on birth outcomes are stronger for women with lower education levels, those living in areas of high poverty, and African Americans (Hoynes et al., 2011; Khanani et al., 2010). Fingar et al. (2017) accounted for gestational age, which might bias estimates in other studies, and reported a significantly reduced risk of preterm birth, LBW, and prenatal death.

One of the potential channels through which WIC impacts birth outcomes is through changes in dietary quality and access to nutritional information and support for healthy behaviors, such as quitting smoking, for pregnant women. Participants can use their WIC vouchers only for specific foods, and changes in the approved foods after 2008 reflect dietary recommendations from AAP and the Institute of Medicine. The U.S. Department of Agriculture published a final rule in 2014 that provides for more purchases of fruits and vegetables, whole-grain options, yogurt and soy options in place of milk, and more flexibility to tailor food packages to individuals (Carlson and Neuberger, 2018). While there has been concern about the possibility that providing infant formula to new mothers reduces breastfeeding, the changes to food packages and incentives after 2014 have encouraged breastfeeding (NASEM, 2016). The rate of breastfeeding among WIC participants has risen 45 percent over 12 years, reducing the difference between all women and WIC participants (Carlson and Neuberger, 2018).

There is solid evidence linking the WIC program to improved nutrient intake and eating more healthful food, although many of the studies report household-level consumption and do not focus specifically on children. The introduction of the improved food packages in WIC led to noticeable improvements in the percentage of families reporting that they eat more whole grains, drink lower-fat milk, and consume more fruits and vegetables (Andreyeva and Luedicke, 2013; Chiasson et al., 2013; Whaley et al., 2012). Thus, the additional resources to purchase specific food items provided by the WIC program is associated with changes in the types of food consumed by households (Whaley et al., 2012). In the case of the HIP, these changes may have been due in part to “promotional effects,” whereby the incentive for certain foods provides information to participants about which foods are healthier (Olsho et al., 2017).

By providing access to healthier foods and nutrition information, WIC would be expected to improve the health and developmental outcomes of young children. WIC may also reduce food insecurity. One study found that WIC participation reduced the number of children experiencing food

insecurity by 20 percent (Kreider et al., 2016). There is also some evidence about the impact of WIC on young children’s cognitive and socioemotional development. Jackson (2015) used matching and fixed effects estimation methods and found improvements in cognitive development at age 2 and reading and math scores at age 11 for children whose mothers participated in WIC prenatally. In contrast, Arons et al. (2016) found no significant improvement in socio-emotional development among young children receiving WIC; however, their sample size was small. Based on the current literature, the extent to which WIC supports cognitive and noncognitive development in young children is still uncertain.

Overall, the evidence is solid that WIC leads to improved birth outcomes and improved dietary intake for participants, although there is less evidence that it directly improves children’s health and development in the early years. Revisions to the food package and incentives for purchasing specific fruits and vegetables have led to improvements in dietary quality. Evidence of savings on health costs, particularly postpartum, from the mid-1990s suggested that (back then) the cost savings far exceeded program costs (GAO, cited in Carlson and Neuberger, 2018, p. 24). Nearly two-thirds of all infants and half of pregnant and postpartum women are eligible for WIC.10 The broad reach of the WIC program has been viewed as a positive attribute, but some feel that it indicates that the program is not sufficiently targeted and resources could be spent more efficiently (Besharov and Call, 2009). However, many eligible families do not receive WIC benefits. In 2014, only half of eligible pregnant women participated, while 80 percent of eligible infants did (Johnson et al., 2017). While the WIC program is largely successful in supporting the health and nutrition of its recipients, investigating the barriers to participation and further studying heterogeneous effects on different subgroups are necessary to further understand its potential to reduce health disparities in early childhood. Furthermore, better coordination between the WIC program, ECE systems, and prenatal, postpartum, and pediatric care would allow for a more integrated systems approach to addressing children’s nutrition and developmental needs. (See Chapter 8 for more on applying a systems approach to promoting equitable healthy development.) Box 6-4 describes Healthy Mothers on the Move as an example of a promising model to improve nutrition and healthy lifestyles.

Summary

Both the SNAP and WIC programs have been studied extensively, and a large body of literature points to strong associations between program participation and positive outcomes, including less food insecurity,

___________________

10 See https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-eligibility-and-coverage-rates (accessed July 14, 2019).

reductions in poverty, and greater consumption of healthy foods. The evidence is convincing that WIC, which is targeted to pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and young children, improves birth and postpartum outcomes. There is also strong evidence that SNAP improves birth outcomes and child health. In evaluating the impacts of both programs,

however, confounding factors are important to consider: participants may be more disadvantaged than nonparticipants but also may self-select into the programs, and either factor may bias study estimates. A small but increasing number of studies use experimental and quasi-experimental methods to estimate causal effects, although few focus specifically on health outcomes for young children. In addition to providing additional resources to the family to meet their basic needs, both SNAP and WIC can increase the consumption of healthful foods through nutritional education and incentives.

Because safety net programs, such as WIC and SNAP, have been shown to improve birth outcomes and to reduce food insecurity for young children, the committee recommends:

As noted earlier, the National Academies report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty concludes that the current level of SNAP benefits is inadequate. That report considers two options for increasing benefit levels: a 20 or 30 percent increase (along with a higher benefit amount for households with teenagers and a boost in summer benefits). The report also notes that SNAP has a larger effect on reducing deep poverty than other government assistance programs do. Given the strong evidence linking improved child food security and SNAP, along with evidence of longer-term positive outcomes, increases in SNAP benefit amounts are likely to reduce health disparities. This committee had insufficient evidence to compare the effects on health disparities of alternative means of increasing family resources, such as increasing SNAP benefits or providing a monthly child allowance. For the most part, a dollar increase in SNAP benefits will have the same effect as a cash dollar, although some families

might increase food expenditures more with an increase in SNAP. Increasing family resources is a critical, foundational step to reduce child health disparities (see Conclusion 6-1). Careful study and modeling is needed to determine the most cost-effective way to do so, with particular attention to the potential impacts on child and caregiver health and well-being and maternal employment, attachment, and breastfeeding. At the end of the housing section in this chapter, the committee recommends expanding resources to support families with young children, with an increase in SNAP benefit levels as one important option to consider.

HOUSING

Housing Affordability and Child Health and Equity

Access to affordable housing is considered an “upstream” determinant of child development, as it has implications for housing quality (Evans et al., 2000), instability (Garboden et al., 2017; Jelleyman and Spencer, 2008), and loss of housing (Sandel et al., 2018)—all of which are well-established determinants of child health (Leventhal and Newman, 2010). Unaffordable housing, or “high housing cost burden”—typically defined as housing costs above 30 percent of household income—is a critical social issue (Desmond, 2018) that has worsened during the past several decades (Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, 2017). In 2016, 47 percent of all renters and more than three-quarters of families earning less than $30,000 had unaffordable housing (Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, 2017). At the extreme, nearly 110,000 children are estimated to be homeless on any given night in the United States, and more than half of families who used shelters in 2016 identified as African American or black (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, 2018).

The evidence discussed in Chapter 3 suggests that lack of affordable and quality housing, housing instability, and overcrowding have significantly detrimental effects on the health, well-being, and development of infants, children, and families. For more information on the evidence supporting the role of affordable housing in promoting positive outcomes for child health and development, see Chapter 3.

Improving Housing Affordability and Quality

Federal housing assistance is provided through a number of programs, including the Housing Choice Voucher Program, public housing, and the Low Income Housing Tax Credit. The Housing Choice Voucher Program is the largest federal housing assistance program for people with

low incomes. Administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), this program provides funds to local public housing agencies (PHAs). PHAs have latitude in how the program is administered and what populations are prioritized. Eligibility is based on average median income in the geographic area and stratified by extremely low income, very low income, and low income. A PHA has to provide 75 percent of its vouchers to people with extremely low incomes (Eligibility.co, 2019). Although HUD provides housing assistance through the Housing Choice Voucher Program to more than 2 million families per year (CBPP, 2019)—which ensures that participating households contribute no more than 30 percent of their income to rent (CBPP, 2017)—only one-quarter of all income-eligible households receive housing assistance (CBPP, 2017), and the average family will spend 26 months waiting for assistance (HUD, 2016). One analysis found that the percentage of families with children receiving rental assistance decreased by 13 percent since 2004, while “the number of families that paid more than half their income for rent or lived in severely substandard housing rose by 53 percent between 2003 and 2013, to nearly 3 million” (Mazzara et al., 2016).

HUD housing assistance can help families obtain improved housing quality and residential stability (social factors that are associated with child development and disparities) (Fischer, 2015; HUD, 2014, 2015). There is some evidence to suggest that housing assistance has a beneficial impact on child health (Slopen et al., 2018), although this is an underexplored area of research. Only a small number of studies have rigorously controlled for selection bias, thereby limiting interpretation of the results for many of the existing studies (Ahrens et al., 2016; Fenelon et al., 2018; Fertig, 2007; Jacob et al., 2015; Kimbro et al., 2011; Leech, 2012; Newman and Holupka, 2017; Slopen et al., 2018). According to an analysis by Chetty et al. (2016) of the Moving to Opportunity demonstration, the benefits of the voucher program may be greater for children who move when they are young (less than 13 years of age) and may “reduce the intergenerational persistence of poverty and ultimately save the government money” (Chetty et al., 2016, p. 860). (See the section on Improving Neighborhood Conditions for more on the Moving to Opportunity study.)

Although this program is designed to provide families with choices about residential location, new evidence suggests that the program falls short on multiple neighborhood characteristics for families with children (Mazzara and Knudsen, 2019). A 2019 study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities using HUD administrative data and Census survey data revealed that in the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the United States, voucher-assisted families with children are disproportionately clustered into high-poverty, low-opportunity, or minority-concentrated areas relative to the distribution of voucher-affordable housing across the

metropolitan area. For example, 33 percent of families with children using vouchers reside in high-poverty neighborhoods (Census-tract poverty rate at or above 30 percent) even though only 22 percent of voucher units are in high-poverty neighborhoods. Similarly, 61 percent of voucher-assisted families of color with children reside in “minority-concentrated” areas (Census-tract percent of people of color is at least 20 percentage points greater than the proportion in the entire metropolitan area), although only 32 percent of voucher units are allocated to minority-concentrated areas (Mazzara and Knudsen, 2019). Some programs, such as the Baltimore Mobility Program, include intensive counseling and require the use of vouchers in low-poverty areas for at least 1 year (Darrah and DeLuca, 2014). However, lack of affordable units in higher-opportunity neighborhoods remains a barrier (Misra, 2016). Other barriers include inflexible limits on search periods for families to find units and landlord resistance to voucher clients (Sard et al., 2018).

A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty modeled “expansions of voucher availability rather than other modifications, such as an increase in the level of housing subsidies, primarily because most experts agree that limited availability is currently the primary barrier preventing subsidized housing programs from having a larger impact on poverty reduction” (NASEM, 2019, p. 146). That committee also noted that “there is as yet no consensus among researchers as to whether existing housing subsidy levels set by the government are sufficiently aligned with true market rents faced by low-income families” (NASEM, 2019, p. 146).

As discussed in Chapter 3, housing quality is also a contributor to child health and development. A systematic review found strong evidence of effectiveness for home interventions focused on addressing asthma triggers, including multifaceted, in-home, tailored interventions (including mattress and pillow covers, high-efficiency particulate air vacuums and air filters, and cleaning), cockroach control through integrated pest management (including e-strategies, reducing access points, and using low-toxicity gel-bait pesticides), and combined elimination of leaks and removal of moldy items (Krieger et al., 2010). Several of the reviewed studies focused on children. A systematic review conducted by Crocker et al. (2011) found that home-based, multitrigger, multicomponent interventions reduced asthma symptoms and school absenteeism, as well as asthma acute symptoms, among children and adolescents. These assessments and interventions are often performed by home visitors or community health workers and have been found to be effective in both urban and rural areas (Chew et al., 2003; Crain et al., 2002; Levy et al., 2006; Morgan et al., 2004). The actions taken as a result of these assessments and interventions have been found to reduce disparities in asthma-related outcomes based on race/ethnicity and income (Postma et al., 2009).