7

Promoting Health Equity Through Early Care and Education

INTRODUCTION

Several important threads are evident throughout this report: the importance of intervening early, preferably before adversity occurs, but if not, soon after; the inextricable interplay between genes and the child’s environment in producing health; the need to support caregivers of children—those who spend significant time with children and therefore have an important impact on children’s growth and development; and the need to create healthy, supportive environments. Knowing that most young children participate in some type of nonparental care on a regular basis (formal or informal arrangements), the early care and education (ECE) platform is a significant opportunity for health promotion and advancing health equity (see the committee’s conceptual model, Figure 1-9, in Chapter 1). ECE is defined here as nonparental care that occurs outside the child’s home. ECE services may be delivered in center-based settings, school-based settings, or home-based settings (i.e., a setting other than a child’s home) (NASEM, 2018); however, this chapter also discusses programs that support parents, such as home visiting. Education itself is incredibly important when it comes to health (García, 2015). Because educational attainment positively correlates with health outcomes, investments in ECE are critical to decreasing disparities to set the stage for future success (Barnett, 2013; NASEM, 2017a). In this chapter, the committee discusses how to apply the important learnings from early development to the ECE system, including the importance of a properly supported and trained ECE workforce, access to quality ECE, and

resources to support these needs. At the end of the chapter, the committee provides recommendations detailing the specific actions needed to ensure that ECE meets its potential to promote child health and well-being. See Box 7-1 for an overview of the chapter.

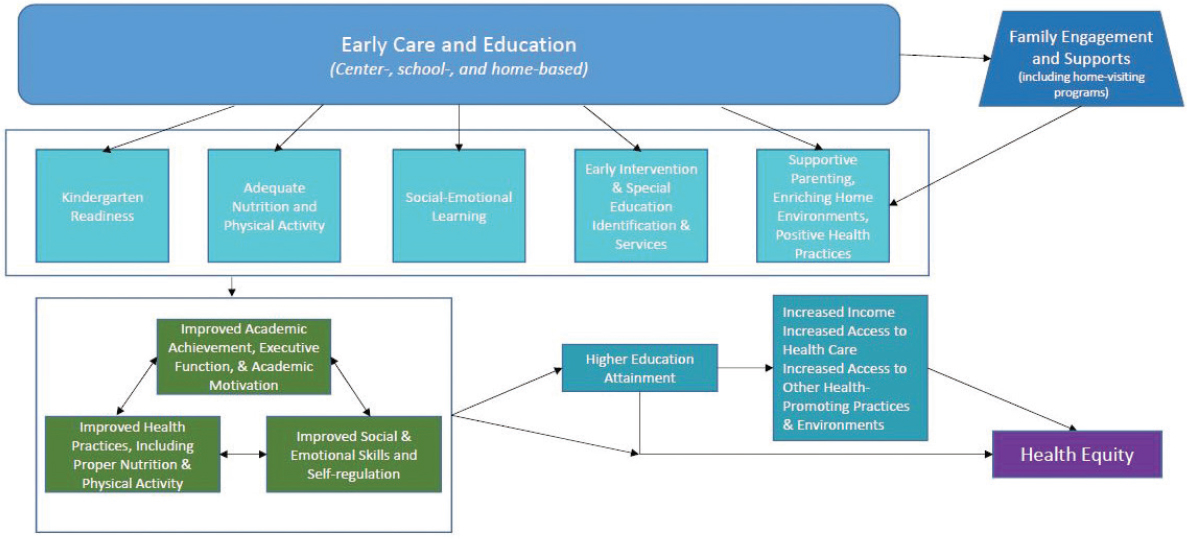

While ECE has primarily focused on whether it improves children’s cognitive and social-emotional development, as well as academic readiness, there is some indication that ECE may influence child (and even adult) health outcomes, including physical, emotional, and mental health (Campbell et al., 2014; D’Onise et al., 2010; Muennig et al., 2011). What is also of critical importance is how ECE is related to children’s cognitive development, social-emotional development, academic readiness and achievement, and health and well-being, as well as how it can lead to health equity. Hahn and colleagues (2016) postulate that ECE advances health equity through several interrelated systems (see Figure 7-1).

ECE programs increase children’s cognitive, social, and health outcomes through enhancing children’s motivation for school and readiness

to learn and identifying problems that impede learning. This, in turn, helps children improve their cognitive ability and social and emotional competence while increasing their use of preventive health care. There is also evidence that participation in a high-quality early learning program is associated with children’s self-regulation; approaches to learning, such as their motivation and persistence; and executive function (EF) skills, which are domain-general skills that transfer to many areas of development, including learning to read, making friends, and dealing with new challenges (Holliday et al., 2014; Pianta et al., 2009; Yoshikawa et al., 2013). These short-term outcomes of ECE are then expected to lead to lower risk of dropping out of school, greater school engagement, and subsequently better educational attainment, which results in increased income and health care, decreased social and health risk, and improved health equity. Traditionally, ECE is thought of as being confined to a specific age range. For this report, the committee discusses ECE in the context of birth through 8–10 years of age. Another National Academies report,

SOURCE: Informed by Hahn et al., 2016.

The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth, picks up from here, discussing health and development from the onset of puberty into adolescence and early adulthood (NASEM, 2019).

DIRECT LINKS BETWEEN ECE AND HEALTH EQUITY

Health, social-emotional, and other health-related behavioral outcomes are some of the most commonly reported from evaluations of ECE programs, aside from the often-cited cognitive outcomes (Cannon et al., 2017; Carney et al., 2015; Fisher et al., 2014; Rossin-Slater, 2015). ECE programs have been shown to reduce externalizing and internalizing behaviors (Carney et al., 2015), improve social-emotional skills (D’Onise et al., 2010; Hahn et al., 2016), reduce substance use (Cannon et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2015), and improve physical health or well-being (D’Onise et al., 2010; Rossin-Slater, 2015; Sabol and Hoyt, 2017). ECE can produce this range of results through different pathways. It can provide services to children and/or their parents directly that impact their health outcomes and related skills and behaviors; implement evidence-based curricula or interventions to improve children’s social-emotional skills, which are associated with both short- and long-term health and cognitive effects; and support the training and well-being of early childhood educators.

While reviews of the research literature suggest that ECE programs can be a promising lever for improving health outcomes and equity, they also show instances where ECE programs have weak, nonexistent, or even negative impact on children’s behavior and health (Cannon et al., 2017; D’Onise et al., 2010; Hahn et al., 2016; Herbst and Tekin, 2011; Rossin-Slater, 2015). These mixed and negative findings could reflect factors such as lack of program quality, poor fidelity to the program model, and limited program duration. The following section takes a deeper dive into specific ECE programs or interventions that have produced significant results on health and discusses their characteristics.

Links Between ECE and Health Outcomes

A number of studies and reviews of the literature have found positive relationships between participation in ECE programs and physical health indicators and outcomes (Hahn et al., 2016; Kay and Pennucci, 2014). Most of the associated benefits tend to be related to obesity, access to health care, and early screenings and detection. For example, low-income preschoolers enrolled in a center-based program are less likely to experience food insecurity than if they were cared for by parents exclusively or by an unrelated adult in a home setting (Gundersen and Ziliak, 2014). Using a quasi-experimental methodology on data from the Eunice Kennedy

Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (NICHD SECCYD), Sabol and Hoyt (2017) found that 4-year-olds who attended center-based ECE programs had lower blood pressure when they were 15 years old than those who were in a home-based environment, whether that was with a parent, a relative, or a nonrelative.

Hahn et al. (2016) sought to examine the impact of ECE on fostering the health equity outcomes of low-income and racial and ethnic minority children through a meta-analysis. They focused on state and district programs, the federal Head Start program, and foundational model programs, such as the HighScope Perry Preschool Project (PPP) and Carolina Abecedarian (ABC) program. They included studies that were for children aged 3 or 4 years; primarily focused on low-income or racial and ethnic minority populations; were not conducted only in the summer; were based on behavioral interventions; included assessment of effects on children’s health and health-related or academic outcomes; and had a control or comparison population and provided enough data for analysts to calculate effect size and adjust for confounding. Findings were included for the following outcomes: standardized achievement (effect found across program types); high school graduation (effect found only for Head Start); grade retention (effect found across program types); assignment to special education (Head Start was not evaluated on this measure; effect found for all other programs); and crime (effect found across all program types) (see Table 7-1 for more information). Additional analyses examining the persistence of effect of programs on academic achievement and cognitive ability showed a rapid decrease of effects after the program ended, then a gradual decline over time. Higher program quality based on observational data and having teachers with a bachelor’s degree or higher had greater effects on student standardized achievement. There were insufficient data to examine impact of class size, hours, duration, or benefits of additional components, such as family engagement or health access. In sum, there was consistent evidence that center-based ECE programs improved educational and health-related outcomes for low-income and ethnic minority preschool-age children, with some indication of long-term outcomes. Hahn et al. (2016) further note that the fade-out of center-based ECE effects for cognitive and achievement outcomes could likely be because many low-income and ethnic minority children are likely to attend low-resourced (i.e., lower-quality) elementary schools and have teachers with fewer credentials. Others, such as Duncan and Magnuson, have postulated that “preschool programs may affect something other than basic achievement and cognitive test scores, and perhaps these other program impacts, unlike achievement and cognitive impacts, persist over time” (Duncan and Magnuson, 2013, p. 120). That

TABLE 7-1 Effects of Center-Based Early Childhood Education Programs on Education, Social, and Health-Related Outcomes (data for all program types combined)

| Outcome (number of studies; program types included) | Mean Age at Follow-Up, y | Standardized Mean Difference (95% CI) | Effect Meaningful? | Consistent Across Body of Evidence? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test scores (27 studies; all types) | 3.7 | 0.29 (0.23−0.34) | Yes | Yes |

| High school graduation (7 studies; all types) | 20.0 | 0.20 (0.07−0.33) | Yes | Yes |

| Grade retention (12 studies; all types) | 17.0 | −0.23 (−0.43 to −0.02) | Yes | Yes |

| Assignment to special education (6 studies; state and district and model programs) | 15.5 | −0.28 (−0.49 to −0.08) | Yes | Yes |

| Crime (5 studies; all types) | 25.0 | −0.23 (−0.45 to 0.05) | Yes | No |

| Teen birth (3 studies; Head Start and model programs) | 18.0 | −0.46 (−0.92 to 0.0) | Yes | No |

| Self-regulation (5 studies; state and district and Head Start programs) | 18.0 | 0.21 (0.14−0.28) | Yes | Yes |

| Emotional development (7 studies; state and district and Head Start programs) | 4.0 | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.12) | No | No |

SOURCE: Hahn et al., 2016.

is, looking at discrete and constrained skills, such as letter naming, may not be good predictors, whereas focusing on unconstrained skills, such as self-regulation and expressive language, would be more appropriate. Thus, there is more to understand about the fade-out effect, or arguably the catch-up effect, especially in the changing landscape where more children are in out-of-home settings.

The research is equivocal, however, especially for health, social, and emotional outcomes. Herbst and Tekin (2011) found that 4-year-old children of single mothers who were enrolled in nonparental care

through a child care subsidy were more likely to be obese or overweight when they were kindergartners than those who stayed home. As with a study by Hawkinson and colleagues (2013), this study also found an association between subsidy use and poor cognitive outcomes. A review of 37 studies found “generally null effects of preschool interventions across a range of health outcomes” (D’Onise et al., 2010, p. 1432), leading the authors to caution against relying on a “flimsy evidence base” to inform policy (D’Onise et al., 2010, p. 1432). However, the study did find “a general trend toward beneficial effects, with particularly beneficial effects for overweight and obesity, mental health, social competency, and crime prevention” (D’Onise et al., 2010, p. 1432). They also found that across the studies, half of the comparisons related to immunization and general health yielded positive impacts (and none produced adverse effects).

Foundational Research in ECE

The foundational studies of the HighScope PPP and Carolina ABC project provide the most robust findings regarding the link between ECE and health equity throughout the life course. As described below, these two programs—which occurred in two different states and were conducted by two different teams in two different decades—have similar short- and long-term outcomes. They also shared some common characteristics: they focused on children with the greatest needs and employed an educated and responsive teacher, low child–teacher ratio, active and language-rich learning opportunities, child assessment, and home visiting and family support activities.

Some caution, however, should be taken in generalizing these findings due to the limitations of these studies. They occurred more than 50 years ago, when most children in poverty did not have access to early education services and programs. The samples, primarily African American children, are not representative of the general population. They were also small and continued to decrease over time. Finally, these controlled programs have not been adequately replicated at a large scale. It is also critical to note that not all children in the treatment groups performed at the highest level and in the end, did not surpass their more economically advantaged peers. For example, in the PPP study almost one-third of children from the treatment groups were arrested five or more times by age 40, almost one-third did not graduate high school, and almost two-thirds of children from the treatment group required public assistance as adults (Gomby et al., 1995). Thus, these programs did not equalize the outcomes for children from low-income households in comparison to their higher-income peers.

While PPP and ABC provide a blueprint to build from to support children’s school readiness, achievement, and health equity throughout the life course, policy makers and practitioners alike need to base their decisions on lessons beyond those from these studies, such as more contemporary ECE programs and interventions discussed in this chapter, to ensure that all children, especially children with the greatest needs, have the same opportunity to thrive and lead healthy lives.

HighScope Perry Preschool Project (PPP)

The HighScope PPP started in 1962 with a focus on serving 3- and 4-year-olds (it was 1–2 years long) with a home visiting component. The program aims to promote social and cognitive development in children who are at risk due to poverty. Schweinhart and Weikart (1997) showed that students enrolled in the program in 1986 had more positive behavior and attitudes than students in the control group (Schweinhart and Weikart, 1997). In addition, experimental evaluations of study participants in their teens and 20s showed that even years later, when study participants were in their teens and 20s, students formerly enrolled in the program “had higher academic grades and earnings, higher rates of high school graduation, fewer arrests and out-of-wedlock births, and lower levels of welfare receipt than their peers who were not in a preschool program” (Child Trends, 2012). Furthermore, children in the intervention group had higher rates of safety-belt use and engaged in fewer risky health behaviors, such as smoking and illicit substance use, in adulthood compared to those in the control group. At age 27, former PPP students were more likely to be employed and had higher earnings than students in the control group (Child Trends, 2012; Schweinhart et al., 2005). This continued into age 40, with former PPP students having higher earnings, committing fewer crimes, and being more likely to hold a job and to have graduated from high school than adults who did not participate in PPP. In 2019, Heckman and Karapakula presented findings from the HighScope PPP Age 55 Study (Heckman and Karapakula, 2019a). They indicated that the program kept parent engagement active longer, which resulted in more warmth and less authoritarian parenting. They also found that at age 55, the female participants in the early childhood intervention group had lower cortisol (39.01 versus 89.29 picograms per milligram) compared to the control group, and the male participants were less likely to have high cholesterol levels (mean differences in high cholesterol1 were 0.71 in the treatment group versus 0.94 in the control group). Female participants

___________________

1 High total cholesterol indicates whether total cholesterol concentration in milligrams per deciliter is 220 or higher.

in the intervention group were also less likely to be uninsured for a prolonged period compared to the control group (Heckman and Karapakula, 2019b). In addition, they reported intergenerational effects for children of intervention participants: completion of high school, good health status, stable employment, and a history of never having been suspended and arrested (Heckman and Karapakula, 2019a).

Carolina Abecedarian (ABC) Study

The Carolina ABC Study is a center-based intervention that enrolled families between 1972 and 1977 based on a high-risk index. During recruitment, 111 infants were matched on high-risk scores and then assigned to preschool treatment or control status. Fifty-seven infants were assigned to the experimental group and 54 to the control group (Campbell et al., 2012). The families in the study were mostly African American with young mothers, less than a high school education, unmarried, living in multigenerational homes, and reporting no earned income (Campbell et al., 2012). The service delivery model for the experimental group was a 5-year, full-day, year-round, center-based program with a comprehensive curriculum (LearningGames®) (Sparling and Lewis, 1979) focused on educational games addressing children’s cognition, language, and adaptive behavior. The program also emphasized health care and family support programs. Activities were individualized for the child’s needs, with more conceptual and group-oriented activities as children got older. Families in both the experimental and control groups received supportive social services. Findings showed that children in the 0–5 intervention group had better cognitive, academic, and emotional outcomes (Ramey and Ramey, 2004). This also had persistent effects when children were in their 20s, with children in the treatment group having better intellectual test performance and reading and mathematics test scores, more years of education, and a greater likelihood of being enrolled in college (Campbell et al., 2012; Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, 2012). By age 30, the treatment group was more likely to have completed a bachelor’s degree, have consistent employment, not use public assistance, and have delayed parenthood. Regarding health outcomes, Campbell et al. (2014) found through biomedical data that children in the intervention group at age 35 had significantly lower risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic disease, especially for male participants (i.e., mean systolic blood pressure for the control group was 143 versus 126 for boys in the intervention group). “One in four males in the control group was affected by metabolic syndrome, while none in the treatment group were” (Ramey, 2018, p. 539).

Looking across the body of research, Head Start appears to be particularly effective at promoting young children’s physical health (see

Box 7-2 for more information on Head Start). The Head Start Impact Study showed that children enrolled in the program had better access to dental care while they were in the program and to health insurance when they were in kindergarten (Puma et al., 2012). Broader reviews of research on Head Start show positive impacts on obesity, immunization, screening for hearing and vision problems, and even child mortality (Belfield and Kelly, 2013; Rossin-Slater, 2015; Yoshikawa et al., 2013). In addition, in their review of Early Child Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B) data, Belfield and Kelly (2013) found that Head Start provided its participants “protective effects against . . . asthma, respiratory ailments, allergies, and being on medication” (Belfield and Kelly, 2013, p. 322). Lee et al. (2013) used data from ECLS-B to analyze low-income children’s nutrition, weight, and health care receipt at kindergarten entry. They compared (a) Head Start participants and all nonparticipants, and (b) Head Start participants and children in pre-kindergarten (pre-K), other center-based care, other nonparental care, or only parental care using propensity score–weighted regressions. They found Head Start effects were larger compared to informal child care settings rather than center-based settings. Specifically, Head Start children had lower body mass index (BMI) scores and probability of being overweight compared to children in home-based settings; had better healthy eating habits than children in center- and home-based settings; and were also more likely to have dental care checkups compared to children in any other type of setting, including pre-K and center-based settings. Furthermore, dosage appears to matter. Frisvold and Lumeng (2011) analyzed administrative data from more than 1,500 children from Head Start programs in Michigan from 2001 to 2006 and found that children who participated in full-day Head Start were 25 percent less likely to be obese at the end of an academic year than those who enrolled in half-day programs. The effect seems to be more pronounced for boys and African American children.

One reason that Head Start stands out among ECE programs with respect to impact on physical health outcomes may be that the program design includes a robust health component (such as requiring programs to provide diverse nutrition and health services, helping families receive physical examinations by scheduling screening appointments or offering screenings directly onsite, assisting families in applying for age-appropriate health care services, providing health promotion activities directly onsite, and tracking each child’s health progress) (Lee et al., 2013). In their review of the literature, Yoshikawa et al. (2013) concluded that “in contrast to the literature on Head Start and health outcomes, there are almost no studies of the effects of public prekindergarten on children’s health” (Yoshikawa et al., 2013, p. 5) because pre-K programs typically do not provide health-related services.

However, pre-K programs can incorporate such services and potentially achieve similar outcomes. A recent evaluation of the Universal Pre-K (UPK) program in New York City found that the expansion of the program “led to increases in rates of diagnosis of asthma and vision problems, to increased rates of screening for immunization or infectious disease, and to increased rates of treatment of hearing and vision problems” among Medicaid recipients who were eligible for UPK (Hong et al., 2017, p. 3). The researchers attribute some of these findings to UPK’s program requirements, which include immunizations and developmental screenings for all enrolled students. In other words, by incorporating direct services2 into their program design, Head Start and New York City’s UPK initiative have become opportunities to effect broad improvements in young children’s health outcomes.

Head Start and the UPK program in New York City are just two examples of large-scale, publicly funded ECE programs that have demonstrated generally positive results for preschool children. Others include state-funded pre-K programs in Georgia, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Oklahoma and district-run programs, like that of Boston. In a review of the body of research behind these and other large, publicly funded programs, Phillips et al. (2017) concluded that there is robust evidence of short-term benefits, especially in cognitive and academic skills. However, “the available evidence about the long-term effects of state pre-k programs offers some promising potential but is not yet sufficient to support confident overall and general conclusions about long-term effects” (Phillips et al., 2017, p. 10). For example, Lipsey et al. (2018) found that although children who participated in the Tennessee pre-K program demonstrated better cognitive skills than the control group, this advantage was lost or even reversed by 2nd or 3rd grade.

Still, the promising results from large-scale, publicly funded pre-K programs, in light of the impacts that Head Start and New York City’s UPK program have on young children’s health outcomes, suggest that ECE programs that serve significant proportions of young children can be a platform for interventions that promote health equity.

Home-Based Child Care Programs

Home-based child care is regulated family child care and family, friend, and neighbor care (Porter et al., 2010b). As mentioned earlier, it is a common arrangement for many young children in the United States,

___________________

2 For example, immunization and a valid and reliable developmental screening tool to identify students with potential developmental delays and English Language Acquisition support needs.

particularly those from low-income families and families of color (Porter et al., 2010b). As Porter et al. note, “parents use these arrangements for a variety of reasons, including convenience, flexibility, trust, shared language and culture, and individual attention from the caregiver” (Porter et al., 2010a, p. 1). Home-based child care also serves as a primary nonparental care arrangement for infants and toddlers (Corcoran et al., 2019). (See Chapter 3 for statistics by race, ethnicity, and income.)

While most young children who are not yet enrolled in kindergarten participate in some kind of weekly center- or school-based early childhood program, 41 percent of them receive care weekly from a relative, and 22 percent participate in nonrelative care in a home environment (Corcoran et al., 2019). (Twelve percent of young children receive care in more than one of these settings on a weekly basis.) The number of children in center-based care increases as children get older. Furthermore, about 3.6 million of the approximately 3.7 million home-based providers are “unlisted”: they are not registered with, licensed by, or regulated by a public agency. Together, these home-based providers serve more than 7 million young children (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2016). Children of color are more likely to receive care from a relative, while white children are more likely to participate in nonrelative home-based care. Infants and toddlers are more likely to be cared for in a home setting—whether with a relative or nonrelative—while preschool-aged children are more likely to be enrolled in a center- or school-based program. Families with a household income of $75,000 or less are also more likely to put their young children in relative care (Corcoran et al., 2019). Thus, to the extent that regulations and policies related to safety and quality promote better care and child development, the youngest children, low-income children, and children of color could disproportionately lack access to ECE opportunities that are more equipped to support their cognitive, social-emotional, and healthy development.

The majority of evidence linking ECE to children’s health, education, and well-being is primarily from center- and school-based programs. Some studies have shown a link between home-based programs and children’s academic skills and social-emotional development. For example, Iruka and Forry (2018) found that children in home-based programs that were high quality and engaged frequently in enriching literacy and numeracy activities (e.g., learning names of letters, learning the conventions of print, using manipulatives, using a measuring instrument, learning about shapes and patterns) were likely to have stronger reading and math skills compared to children in home-based programs that were low quality and engaged in fewer enriching activities. This is consistent with prior work by Forry et al. (2013) using data from a multistate study of a professional development intervention showing that the quality

of home-based programs, their child-centered beliefs (e.g., progressive beliefs that children should have autonomy and be allowed to express their ideas), and their perceptions of job demands were related to children’s school readiness, emotional health (e.g., initiative, self-control, and attachment), and internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors.

However, mostly correlational data indicate that children in centers compared to family child care homes had higher cognitive, language, and school readiness scores but increased likelihood of contracting communicable illnesses and otitis media (ear infection), which is likely due to the large group size (Bradley and Vandell, 2007). While the data are mixed, there is indication that children in home-based programs have stronger social-emotional competence compared to children who attended center-based programs (Belsky et al., 2007). In their analyses examining multiple child care arrangement and children’s academic and behavioral outcomes, Gordon et al. (2013) found that preschool children, on average, scored higher on reading and math assessments when they attended centers alone or centers in combination with home-based programs than home-based programs only or parental care. There were no differences in children’s social-emotional development between families who used or did not use multiple care arrangements. The stronger benefits for children’s cognitive and school readiness skills for center-based compared to home-based programs have also been seen for Latino children (Ansari and Winsler, 2012).

These better academic outcomes for center- versus home-based programs are likely due to higher teacher education and more training opportunities (Bradley and Vandell, 2007). However, the larger group size in center-based programs may preclude sensitive individual care and attending to children’s social-emotional needs, which could exacerbate problem behaviors (Gordon et al., 2013). There is still a need for more rigorous examination of the differential impact based on program type and accounting for differences in teacher education and training, sociodemographics of children and families, and more robust health-related outcomes.

Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRISs)

Motivated in part by ECE research, states and localities have implemented QRISs to promote and enhance ECE program quality across various sectors and settings, including schools, community-based organizations (center- and home-based), and Head Start. State and local policy makers have used research linking high-quality early childhood education and children’s outcomes in developing QRISs to ensure that children, especially disadvantaged children, are attending high-quality education

programs during the early years. QRISs could serve as a unifying framework for defining quality across ECE programs and a defined pathway for achieving it. Moreover, without a strategy such as a QRIS, ECE programs could have inequitable resources for improvement, exacerbating the variance of quality among programs and leading to inequitable outcomes for children, families, and communities. When funded adequately and supported as a unifying strategy for ECE, QRISs can raise the overall quality of the ECE system and create more equity across communities.

Almost all QRISs measure staff training and education and assess the classroom or learning environment (Burchinal et al., 2015). Factors such as parent-involvement activities, business practices, child–staff ratios, and national accreditation status vary by state (Burchinal et al., 2015; Zellman and Perlman, 2008). QRISs serve multiple purposes, including providing a standardized method to rate program quality—based on a set of criteria—and to make the program rating information available to parents, as is done with restaurant ratings. The rating system is built on the primary assumption that parents often lack good information about program quality and that such information would inform their decisions on program selection (Burchinal et al., 2015). Consequently, providers who work with lower-quality programs would be incentivized to enhance the quality of their program or leave the market (Burchinal et al., 2015; Zellman and Perlman, 2008). In addition, QRISs represent a systematic approach to providing a range of technical assistance, resources, and incentives for programs to improve their quality (Burchinal et al., 2015). This could entail consultation on quality improvement, increased investments for professional development scholarships, microgrants for other targeted efforts, and increased subsidy payments for more highly rated programs (Burchinal et al., 2015). It has been noted that regarding QRIS,

the goal of these efforts is to foster and support providers’ efforts to improve the quality of care they provide. Thus, [QRISs] attempt to improve quality by affecting both the demand for high-quality care and the supply of such care. Of course, the success of such efforts rests on the ability of rating systems to accurately identify and measure key aspects of quality and the willingness of providers to participate in a rating system. (Burchinal et al., 2015, p. 255; see also Zellman and Perlman, 2008)

Validation of QRISs has yielded mixed findings. The Race to the Top—Early Learning Challenge Grant resulted in a proliferation of QRIS validation studies. Prior to this, most research on QRISs was descriptive and focused on issues of implementation. A recent synthesis of the validation studies by Tout et al. (2017) from 10 states found that while these ECE rating systems were valid (i.e., independent observations indicated meaningful differences across levels), most programs were, on

average, providing a moderate level of quality and inconsistently associated with child outcomes, mostly for social-emotional development and EF outcomes.

There has been a limited focus on children’s physical health. In their synthesis of states’ QRIS validation studies, Tout et al. (2017) found that only two states focused on physical development, which included BMI and fine and gross motor skills. One state found a link between its QRIS and children’s fine motor development, indicating that higher-rated programs were associated with improved fine motor development. Several states have included nutrition, physical activity, and screen time as part of their QRIS standards (Gabor and Mantinan, 2012). In their report to examine state efforts to address obesity prevention in QRISs, Gabor and Mantinan (2012) found specific standards, including a focus on nutrition (including standards), physical activity and screen time limits, professional development for staff and teachers, and sharing information about nutrition and physical activity with families.

The differences in system designs across states make it difficult to draw general conclusions from these validation studies about their links to various domains of children’s development, especially health. The voluntary nature of QRISs in most states and the varying standards also make it difficult to establish a causal link between them and child outcomes. Even with these limitations, the QRIS is one potential, and perhaps underused, platform that could increase the use of evidence-based, health-promoting practices and standards in a mixed-delivery system by unifying leadership and governance, standards, financing, stakeholder engagement, improvement supports, accountability, and continuous quality improvement. As QRISs expand, mature, and become better funded, they could serve as the one point of entry that promotes high-quality programming across various settings (e.g., home, school, centers) and provides more children, especially children with the greatest needs, with access to beneficial ECE experiences that meet their comprehensive needs regardless of program funding.

Early Intervention for Children with Developmental Disabilities

Early Intervention3 services support the early development of children with developmental delays or specific health conditions that could lead to delay (e.g., genetic disorder, birth defect, hearing loss). These services and programs intend to help children catch up and increase their chances for school and life success, though most of this work falls

___________________

3 Early intervention refers to services for children ages 0–3. Early childhood special education refers to services for children ages 3–5.

to parents and families. Early intervention services are provided under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Eligible children are able to receive services free of charge (or at a reduced rate) through federal grants to states. Each state has its own definition of developmental delay and its own process for determining eligibility and identifying eligible children. Families with children under age 3 who qualify for early intervention receive an Individualized Family Service Plan that defines goals and the types of services that will support the family and child. Children older than age 3 who are eligible for special education services under IDEA meet with school professionals to develop an Individualized Education Program to support their educational goals.

Some of the specialists who work with children include speech-language pathologists, who help with communication speech and language delays; physical therapists, who strengthen children’s movement, gross motor skills, and physical development; occupational therapists, who improve fine motor, cognitive, sensory processing, and communication skills; nurses, who support children’s health status and address feeding and growth concerns; social workers, who assess and support children’s social and emotional development; and developmental therapists, who design learning activities to promote children’s learning and social interaction skills.

Early Intervention (Children Under 3 Years Old)

A substantial body of research supports the effectiveness of early intervention for children’s functioning (Bruder, 2010; Guralnick, 2005). However, these studies suffer from methodological limitations, such as sample heterogeneity, lack of control groups, narrowly defined outcomes, and inappropriateness of standardized measures of intelligence (Bruder, 2010). Nevertheless, there is a body of research indicating that children who receive early intervention services (Part B or Part C) are less likely to see a decline in their functioning over time, with effect sizes of 0.5 to 0.75 of the standard deviation (Guralnick, 1998). This is supported by a foundational meta-analysis of 31 studies examining the effect of early intervention, which found that early intervention was “effective in promoting developmental progress in infants and toddlers with biologically based disabilities” (Shonkoff and Hauser-Cram, 1987, p. 650). The mean effects of early intervention services ranged from 0.43 for motor development to 1.17 for language development. In particular, they found that “programs that served a heterogeneous group of children, provided a structured curriculum, and targeted . . . parents and children together appeared to be the most effective” (Shonkoff and Hauser-Cram, 1987, p. 650).

In their study of community-based early intervention services for children who were in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), Litt et al. (2018) analyzed retrospective data from the U.S. Department of Education’s National Early Intervention Longitudinal Study and found that longer and more intensive services were associated with higher kindergarten skills ratings and the importance of following up after children left the NICU. These findings are consistent with those from McManus et al. (2012) in their longitudinal study of mother–infant dyads from three NICUs in southeastern Wisconsin. They matched pairs of dyads using propensity-score matching to reduce selection bias and estimate the effect of early intervention services on cognitive function trajectories. They found that service receipt was positively associated with children’s cognitive functioning and trajectory and more maternal supports (e.g., mothers’ report of emotional, informational, child care, financial, respite, and other support) was associated with better outcomes for families over time. Unfortunately, national data indicate that children who qualify for early intervention services are not likely to receive them, with this issue especially pronounced for black children (Boyd et al., 2018).

Most of the recent evidence about early intervention has primarily focused on children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which “is characterized by severe and sustained impairment in communication and social interaction and restricted patterns of ritualistic and stereotyped behaviors manifested [before] 3 years old” (APA, 2013). Children with ASD often qualify for early intervention services, usually because they are not developing in social, play, language, and cognitive domains at the expected pace (Landa, 2018). In her review of the efficacy of early interventions for young children with or at risk for ASD, Landa (2018) found that greater intervention intensity (hours and duration in months) and fidelity of implementation were associated with greater child gains. One of the applied behavior analysis approaches for children with ASD is called Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention (EIBI), which focuses on remediation of deficient language, imitation, pre-academics, self-help, and social interaction skills (Peters-Scheffer et al., 2011). In a meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of EIBI, Peters-Scheffer and colleagues (2011) found that the experimental groups outperformed the control groups on IQ, nonverbal IQ, expressive and receptive language, and adaptive behavior, with differences of 4.96–15.21 points on standardized tests. Reichow (2011) offered a similar conclusion in his overview of five meta-analyses of EIBI for young children with ASD, but he also stressed the importance of more information about child characteristics, additional knowledge on the characteristics of EIBI programs used in real-world settings, and guidelines focused on the intensity, duration, level of treatment fidelity, and therapist experience and/or training necessary to achieve optimal outcomes.

There are disparities in service access for economically disadvantaged and racial and ethnic minority families who have children with ASD (Boyd et al., 2018), and these children are also “at risk for poorer outcomes in comparison to their white and higher-income counterparts, including a more severe symptom presentation (e.g., more severe language and cognitive delays)” (Boyd et al., 2018, p. 20; CDC, 2014; Cuccaro et al., 2007; Fountain et al., 2012). One posited rationale for these poorer outcomes is lower-quality or fewer services (Boyd et al., 2018) and lower likelihood of being referred for services (Delgado and Scott, 2006).

Early Intervention/Special Education (Children 3 Years Old and Older)

Special education provides children with disabilities with specialized services designed to “prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living.”4 “Practitioners are responsible for providing specific services, instructional strategies or routines, and resources that mitigate the impact of the disability on a child’s learning or behavior” (Morgan et al., 2010, p. 236). “Helping the child to benefit from the school’s curriculum should in turn increase subsequent educational and societal opportunities” (ED, 2018; Morgan et al., 2010, p. 236).

The majority of students with disabilities performed in the “below basic” achievement level in all four areas of measurement (mathematics and reading, in 4th and 8th grade) in 2017. The gaps between students with disabilities and those without disabilities are substantial (Advocacy Institute, 2019). Youth with disabilities are also more likely to drop out of school, be delinquent, be unemployed, earn less, and be unsatisfied with their adult lives (Blackorby and Wagner, 1996; Horowitz et al., 2017; Thurlow et al., 2002). There is some evidence that at the end of the school year, youth placed in special education classrooms sometimes score lower on measures of reading, writing, and mathematics skills than they did at the start of the school year (Lane et al., 2005; Morgan et al., 2010).

Establishing rigorous evidence for special education services through randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is not possible because of the legal entitlement to these services for children meeting eligibility criteria, the small sample sizes, and the distinct categories and severities of disabilities (Hocutt, 1996). Thus, different quasi-experimental approaches (e.g., propensity matching) are used to gauge the impact of special education services on children’s outcomes. In one study using propensity-score matching with data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Class (ECLS-K), 1998–1999, which is a large-scale, nationally representative sample of U.S. schoolchildren, Morgan et al. (2010) examined whether

___________________

4 Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act. P.L. 108-446.

children receiving special education services displayed (1) greater reading or mathematics skills, (2) positive learning-related behaviors, or (3) less frequent externalizing or internalizing problem behaviors than closely matched peers not receiving such services. The results indicated that special education services had either a negative or statistically non-significant impact on children’s learning or behavior but a small positive effect on children’s learning-related behaviors, such as their attention on task. Part of these findings may be due to the settings in which children are receiving services. For example, a review conducted by Ruijs and Peetsma (2009) examining the effects of inclusion on students with and without special education showed neutral to positive effects of inclusive education. Specifically, they found that students with special educational needs performed academically better in inclusive than noninclusive settings, possibly because they could learn from more able students or be more motivated to succeed because of the academic focus. Mixed results were found for social-emotional development, with some positive outcomes on social and emotional ratings and negative outcomes based on peer perceptions.

Other Issues in Special Education

Disproportionality in identification Skiba et al.’s (2005) analyses of cross-sectional state-level data indicated that black and Hispanic children were overrepresented in special education. They found this for multiple disability conditions, including intellectual disability, emotional disturbance, speech-language impairment, and learning disability. This supported prior work conducted by Oswald et al. (1999) using cross-sectional, nationally representative, and district-level data showing that minorities were overrepresented in special education, specifically in the mild mental retardation and serious emotional disturbance categories. Oswald et al. (1999) defined disproportionality as “the extent to which membership in a given ethnic group affects the probability of being placed in a specific special education disability category” (Oswald et al., 1999, p. 198), such as mild mental retardation. Morgan et al. (2015), using ECLS-K 1998 data, found minority students were underrepresented, which contradicts previous findings. Analyses of ECLS-K data of multiyear longitudinal observations and extensive covariate adjustment for potential child-, family-, and state-level confounds showed that minority children were consistently less likely than similar white, English-speaking children to be identified as having a disability and so to receive special education services. From kindergarten entry to the end of middle school, racial and ethnic minority children were less likely to be identified as having learning disabilities, speech or language impairments, intellectual disabilities, health impairments, or emotional disturbances. Language-minority children were less

likely to be identified as having learning disabilities or speech or language impairment (Morgan et al., 2015). Many reasons likely account for the mixed findings, including cross-sectional versus longitudinal data, national compared to state or local data, child- versus school-level data, special education category, and trying to equate white and ethnic minority children when the latter are more likely to experience larger risk factors for developmental delay (e.g., poverty).

Nutrition Support Programs

For young students in elementary grades, schools are critical settings to support their health, such as in the area of nutrition. The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) was established under the National School Lunch Act, signed by President Harry Truman in 1946, to “safeguard the health and well-being of the Nation’s children and to encourage the domestic consumption of nutritious agricultural commodities and other foods” (USDA, 2017). The largest of the five school- and center-based programs, NSLP fed about 30 million children each school day in 2014 and cost $12.7 billion (CBO, 2015). In 2014, 52 percent of school-aged children (ages 5–18) participated in NSLP, and 23 percent participated in the School Breakfast Program (SBP) (CBO, 2015). Almost half of all lunches served are provided free to students, with an additional 10 percent at reduced prices. Ethnic minority students participate in NSLP at slightly higher levels than white students, and students from low-income households participate at higher rates than those from higher-income households (Ralston et al., 2008). Ninety-four percent of schools, both public and private, choose to participate in the program (though they are not required to offer NSLP meals). NSLP accounts for 17 percent of the total federal expenditures for all food and nutrition assistance programs (Ralston et al., 2008). School meals are required to meet nutritional targets for calories, protein, calcium, iron, and vitamins. Recent changes in standards have made these meals healthier by reducing salt and saturated fat and increasing servings of fruits and vegetables. While such policies should theoretically lead to improvements in health and nutrition, there is emerging evidence that children may be less likely to consume healthier meals. Some schools have also stopped participating in NSLP because of the increased costs. To be sure, these findings are from only a few studies, and more research on the overall impact on higher nutrition standards is needed (Gundersen, 2015).

Under separate legislation, this program provides free, reduced-price, and full-price breakfasts to students. Other related programs include the Summer Food Service Program (also known as the Summer Meals Program), which extends the availability of free breakfasts and lunches into the summer months in low-income areas; the Special Milk Program,

which provides subsidized milk to schools; and the After-School Snack Program, which “reimburses schools for healthy snacks given to students in educational after-school programs” (Ralston et al., 2008, p. 5). Food insecurity increases during the summer months, when children do not have access to NSLP, and the Summer Food Service Program could alleviate this problem. As of 2012, the Summer Food Service Program has a budget of under $400 million and serves a fraction of the children that NSLP serves (Gundersen, 2015). Alternatively, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits can be increased during the summer months. Based on one demonstration project, it is estimated that an increase of about $2 billion in SNAP could minimize the spike in food insecurity during the summer (Gundersen and Ziliak, 2014).

Based on the report from Ralston et al. (2008), there is mixed evidence on the impact of NSLP on obesity and nutrition. For example, some studies show that children who participate in NSLP have higher intake of key nutrients and lower intake of sweets compared to nonparticipants. Other studies find high intakes of fat and sodium, which may be due to school programs not following the guidelines about fat and sodium levels. This mixed finding may be due to selection effect. For example, in their examination of NSLP on children’s behavior, health, and academic outcomes, Dunifon and Kowaleski-Jones (2003) found that NSLP was associated with an increase in children’s externalizing behavior and health limitation (i.e., limitation in being able to participate in regular activities) and a decrease in their math scores. However, once family-level factors associated with the selection of children’s NSLP participation were adjusted, the effects attenuated. Even after addressing selection effects, there are still mixed findings about the impact of NSLP, with some studies finding participants likely to be overweight (e.g., Schanzenbach, 2009) and others (Gundersen, 2015; Hofferth and Curtin, 2005) finding no effect on obesity. Recent studies to address missing counterfactuals and systematic underreporting of program participation (Gundersen et al., 2012) through causal analytical approaches found some indication of a positive link between NSLP and health outcomes. For example, Gunderson et al. (2012), using data from the 2001–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey study conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that NSLP reduced the prevalence of food insecurity by at least 3.8 percent, the rate of poor health by at least 29 percent, and the rate of obesity by at least 17 percent.

While questions remain about the impact of NSLP on child outcomes, there is consistent evidence about the SBP. Whereas almost all schools participate in NSLP, about 75 percent are part of the SBP, serving 13.2 million children in 2013 (Gundersen and Ziliak, 2014). Frisvold (2015) used the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) and ECLS-K to

determine the impact of SBP on school achievement. Using the NAEP data, he found that availability of SBP increases math by 9 percent of a standard deviation and reading achievement by 5–12 percent of a standard deviation. ECLS-K data show that SBP increases math achievement by 2.7 percent of a standard deviation, reading achievement by 2.0 percent of a standard deviation, and science achievement by 0.9 percent of a standard deviation each school year. Gleason and Dodd (2009) also found a positive effect of SBP but not NSLP on children’s health. Specifically, they found that participation in the SBP is associated with lower BMI but saw no evidence for participation in NSLP and BMI. This association is strongest among white children and not significant for Hispanic children. The mechanism of the effect between SBP and learning is likely through improvement in nutrition, such as increased milk and fruit consumption and decreased soda consumption (Frisvold, 2015).

Beyond NSLP and SBP, there is a need to conduct in-depth examination of other food and nutrition programs. The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) reimburses child care programs (both centers and homes) and after-school programs for meals and snacks. Funded at about $3 billion and serving 3.3 million children in 2013, it is much smaller than NSLP and SBP. One study using the ECLS-B dataset found that participating in CACFP was not associated with any changes in the experience of food insecurity (Gundersen and Ziliak, 2014).

Summary

The PPP and ABC studies were seminal because they inspired research on why the early years are so important to cognitive and health outcomes. They also inspired the design and implementation of large-scale, publicly funded ECE programs that the field continues to evaluate, improve, and refine over time—many of which are discussed in this chapter. The evidence linking health equity to ECE programs and services, including Head Start, pre-K, early intervention, special education, and nutrition programs, is mixed. However, the totality of the research demonstrates effects that are generally positive, albeit with small effect sizes and non-findings in some instances. This indicates that ECE can play an important role in improving health outcomes that could lead to health equity and there is value in continuing to ensure that children have high-quality early learning experiences from birth, though programs may differ in standards, practices, auspices, workforce, dosage, and timing. In order to maximize the impact of ECE, the field will have to better understand how the lessons of PPP and ABC apply (or not) in the current context, with a different counterfactual (i.e., more children with access to some ECE) and more diverse children and programs that operate under different funding

systems and auspices. The field will also have to learn from contemporary large-scale, publicly funded programs and identify essential ingredients that lead to robust health outcomes and health equity. Only then can ECE be meaningfully part of a health promotion strategy that ensures children with the greatest needs are being served, that their needs are met early and consistently (e.g., through early intervention and nutrition), and in a diversity of settings (e.g., home- or center-based care) through a unifying system that provides high-quality access for all children.

LINKAGES BETWEEN ECE AND HEALTH EQUITY THROUGH SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Social-Emotional/Behavioral Development

Social-emotional skills, including emotional processes, social/interpersonal skills, and cognitive regulation (Jones and Bouffard, 2012), in young children have been shown to predict later health outcomes and behaviors, such as substance use or abuse, mental health problems (e.g., depression), and teen pregnancy (Conti et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2015; Moffitt et al., 2011).5 Conversely, externalizing behaviors are associated with later behavioral and academic problems, such as grade retention, school dropout, and lower school engagement (Schindler et al., 2015). Social-emotional skills are especially critical for children and families who experience trauma because of the ways in which such adverse events can impact brain development and affect children’s cognitive and healthy development (see Chapter 2 for more details). For these children and families, those adults, professionals, and programs in both early childhood settings and public schools that provide nurturing and safe environments and bolster self-regulation and social-emotional skills can help mitigate the effects of and build resilience in the face of traumatic experiences (Bartlett et al., 2017). (See Box 7-3 for definitions of key terms.)

How effective are ECE programs in providing such environments? Some reviews of ECE programs have found adverse effects on children’s social behaviors, especially externalizing behaviors (D’Onise et al., 2010). Analyses of data from the ECLS (Loeb et al., 2007; Magnuson et al., 2007) and the NICHD SECCYD (Belsky et al., 2007) found that participation in

___________________

5 Jones and Bouffard define these core skills further: “Emotional processes include emotional knowledge and expression, emotional and behavioral regulation, and empathy and perspective-taking. Social/interpersonal skills include understanding social cues, interpreting others’ behaviors, navigating social situations, interacting positively with peers and adults, and other prosocial behavior. Cognitive regulation includes attention control, inhibiting inappropriate responses, working memory, and cognitive flexibility or set shifting” (Jones and Bouffard, 2012, p. 4).

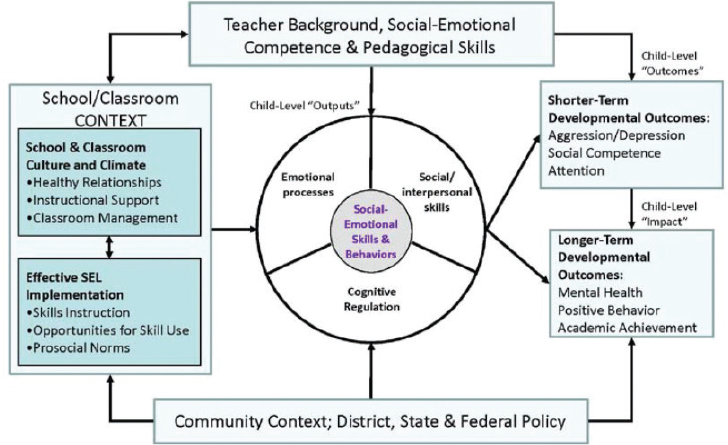

ECE was associated with more reports of behavior problems, including increased externalizing behaviors and lower self-regulation, but also better cognitive outcomes, such as vocabulary and early reading and math skills. More time in ECE appears to be correlated with more pronounced behavioral issues, and the relationship sometimes persisted beyond kindergarten. See Figure 7-2 for an organizing framework for promoting social-emotional outcomes.

However, studies that examined different kinds of ECE or specific interventions in these programs reveal that ECE and public education can be vehicles for cultivating social-emotional skills and reducing bullying behaviors for older children through effective professional development, coaching, and use of evidence-based curricula. For example, an evaluation of the Chicago School Readiness Program shows that the combination of training in classroom management and job-embedded coaching helped Head Start teachers create more “emotionally and behaviorally supportive classroom environments” and reduced children’s emotional and behavioral challenges and improved their EF skills (Raver, 2012, p. 683). Based on the broader body of research, the evaluators further suggested that results like these may lead to “biobehavioral benefits with health impact,” such as lower cortisol in reaction to stress and lower risk of obesity (Raver, 2012, p. 684).

Another teacher training program implemented in Head Start programs, Incredible Years, produced “small but statistically significant improvements in children’s knowledge of emotions, social problem-solving

NOTE: Adapted from collaborative work conducted with Celene Domitrovich as part of the Preschool to Elementary School SEL Assessment Workgroup, Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning.

SOURCE: Jones and Bouffard, 2012.

skills, and social behaviors” but no impact on children’s problem behaviors or EFs (inhibition, working memory, cognitive flexibility), except among those who were exhibiting the most challenging behaviors at the beginning of the school year (Morris et al., 2014, p. 9 of the executive summary). The Good Behavior Game is a behavior management program for elementary schools, and evaluations show that children who participated in it were less likely to behave disruptively. As young adults, they were also less likely to receive diagnoses of conduct or personality disorders or use mental health services than a control group (NASEM, 2016b).

Other trainings for educators offer more direct support inside the classroom. The Early Childhood Consultation Partnership provides mental health consultation to ECE programs that serve children from birth through age 5 in Connecticut. Consultants work with early childhood educators for 8 weeks, at 4–6 hours per week, to improve the social-emotional environment of the classroom, behavior management strategies, and interactions and support for specific children with social-behavioral challenges. An evaluation using randomized assignment showed that preschoolers whose teachers participated in the intervention were rated as exhibiting less externalizing behaviors, such as hyperactivity, restlessness, and impulsivity (Gilliam et al., 2016a).

Research on curricula designed to improve young children’s social-emotional skills yields generally positive but sometimes mixed findings. For instance, a study of Head Start programs that were randomly assigned to implement Preschool PATHS showed that it had “small to moderate positive impacts on . . . children’s knowledge of emotions, social problem-solving skills, and social behaviors” but no impact on their problem behaviors or EF (Morris et al., 2014, p. 13 of the executive summary). Another RCT of the PATHS curriculum led to high levels of social competence, reduced aggression, and improved print knowledge but only for children who started the year with low levels of EF (Bierman et al., 2008). The researchers followed these children for 1 more year, examining 13 child outcomes at the end of kindergarten. In general, they found a sustained, small to moderate impact on social-emotional skills (as opposed to language and literacy), including enhanced learning engagement, improved social competence, and reduced aggression. The effects were especially strong among children who entered low-achieving schools (Bierman et al., 2014).

Another curriculum, Tools of the Mind, was designed to increase EF in young children—especially preschoolers and kindergarteners. The curriculum relies heavily on play-based learning, and teachers who use it with fidelity spend about 80 percent of each day promoting EF. In a study using randomized assignment, children who experienced the curriculum consistently outperformed those who did not on a variety of EF tasks (Diamond et al., 2007). Other studies showed that the curriculum has greater impact on children who may need more support, such as those who attend high-poverty schools (Blair and Raver, 2014) or have issues with hyperactivity or inattention (Solomon et al., 2017). However, Farran et al. (2015) found that children who participated in the Tools curriculum generally performed no better than those in the control group in EF tasks, and in some cases, the control group children performed better. Importantly, the researchers found that the teachers in the treatment group spent less than half of their class time on activities from the curriculum. In addition, while these teachers generally implemented the activities, how they interacted with children (e.g., time spent on content areas, listening versus talking, positive behavioral reinforcement, scaffolding) was not significantly different than their counterparts in the control group. These findings led the researchers to wonder whether a “reliance on a curriculum to affect child outcomes may be less important than changing interaction patterns in the classroom” (Farran et al., 2015, p. 83).

Looking at older, school-aged children, a meta-analysis of 213 school-based social-emotional learning (SEL) programs showed that “students demonstrated enhanced SEL skills, attitudes, and positive social behaviors following intervention, and also demonstrated fewer conduct problems and

had lower levels of emotional distress” (Durlak et al., 2011, pp. 412–413). For example, Second Step is a violence prevention curriculum aimed at a wider range of children from ages 4 to 14. Through short (20–50-minute) lessons, classroom management support, and parent training, the program has been found to reduce aggressive behaviors (NASEM, 2016b, p. 198).

Across the above interventions, one key ingredient for success appears to be curricula that are intentionally designed to promote targeted skills and strong training and professional development (McClelland et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2014). In addition, when they are effective, they appear to have compensatory effects for those children who live or learn in more challenging or adverse environments. As described earlier, SEL can encompass a range of skills. Effective curricula or interventions are explicit about which specific skills are targeted and have intentionally designed activities or program components that target those skills. In their meta-analysis of 31 studies that focused on externalizing behaviors, Schindler et al. (2015) found that ECE programs that implemented “enhancements” or interventions that target specific social-emotional competencies were more effective at improving children’s behaviors than those that relied on a “global” curriculum that addressed children’s learning and developmental domains comprehensively. Durlak et al. (2011) suggest that effective programs use curricula that are “SAFE”: sequenced (activities that are designed to connect and build on each other to strengthen social-emotional skills), active (instruction based on active learning strategies), focused (curricula designed to support SEL), and explicit (targeting specific social-emotional skills rather than general development in this domain).

Beyond the design of the intervention or curriculum, the support provided to early childhood educators who implement SEL programs also appears to matter. In their study of Head Start programs, Morris et al. (2014) attribute successful interventions to high-quality training followed by opportunities to practice new strategies in the classroom and ongoing support from coaches who provide feedback. Raver (2012) and Gilliam et al. (2016a) also emphasize this level of support for educators. However, Schindler et al. (2015) found that interventions that focused more on improving children’s social-emotional skills directly (e.g., through specific activities or lessons in a curriculum) are more effective than training teachers to use more effective behavioral management strategies: while “the addition of a caregiver behavior management training program enhancement was not associated with significant reductions in externalizing behavior problems” (Schindler et al., 2015, p. 253), the “addition of a child social skills training enhancement . . . resulted in half of a standard deviation reduction in externalizing behavior problems . . . which is nearly twice as large as the effect found in a previous

study for high-quality social and emotional learning programs implemented in primary and secondary schools” (Schindler et al., 2015, p. 257).

That said, as described above, research on early childhood mental health consultation programs may point to a promising way to improve teachers’ performance in the classroom. In a qualitative analysis of six statewide or local early childhood mental health consultation programs, Duran et al. (2009) found that effective programs share three core components:

- A robust infrastructure for implementation, including strong leadership, clear program design, clear organizational structure, effective hiring, training, support and supervision of staff, strong partnerships, evaluation, and funding;

- Highly qualified consultants, defined as having a master’s degree in a mental health field, demonstrating core knowledge and skills, and able to develop strong relationships with colleagues, providers, and families; and

- High-quality and comprehensive services that are child centered and targeted to both classrooms and homes, including referral to services that providers and families may need beyond consultation.

In addition, interventions at the classroom or teacher level are more likely to be effective if they are supported by the leadership and broader culture of the school or ECE program. Effective educators are more able to demonstrate their competencies if they work under supportive leadership and policies (IOM and NRC, 2015). Similarly, in its review of the research on antibullying efforts, which focuses mostly on school-aged children, the National Academies’ Committee on the Biological and Psychosocial Effects of Peer Victimization: Lessons for Bullying Prevention emphasized the importance of implementing interventions across all school contexts (not just the classroom) and involving all school staff (NASEM, 2016b). For example, the playground or the lunch room can be a “hotspot” for aggressive behaviors as well as an opportunity to promote prosocial interactions. (See Box 3-4 in Chapter 3 for this committee’s findings on the effects of bullying in early childhood.)

Finally, it is unclear how critical it is for SEL interventions—whether through a curriculum or consultation—to include a parent education or engagement component. Many programs do so to ensure that the strategies implemented in the classroom are reinforced at home (Duran et al., 2009; McClelland et al., 2017). For example, Fast Track is an intervention for students in grades 1 through 10 that is designed to improve children’s social, cognitive, and problem-solving skills by addressing the “interactions of influences” across the school, the home, and the individual

(NASEM, 2016b, p. 201). Longitudinal RCTs of the program found that participants showed lower incidence of diagnoses of psychiatric or behavioral disorders through high school and “reduced adult psychopathology at age 25 among high-risk early-starting conduct-problem children” (NASEM, 2016b, p. 201). Unfortunately, the evaluation was not able to disaggregate the impact of the parent engagement component.

Other research had ambiguous findings. In one small, quasi-experimental study of the Incredible Years program, Williford and Shelton (2008) found that parents in the intervention group were more likely to report the use of effective parenting skills, but they did not observe a significantly lower or different level of disruptive behavior when compared with those in the control group. The two groups also did not differ in their experience of stress. The researchers posited that more robust and targeted interventions may be needed for families, as opposed to relying on a supplement to a classroom-based or teacher-focused intervention. In their qualitative review, Duran et al. (2009) also found that “engaging parents/caregivers can be difficult because they believe the services are unwarranted, unfamiliar, or stigmatizing, or because various factors impede their ability to actively participate in consultation activities (e.g., transportation, time constraints)” (p. 8 of the executive summary).

Perhaps a better approach to strengthening social-emotional development through ECE is to consider the comprehensive array of cross-sector strategies that meet the needs of children and families. The evidence described above suggests that early childhood educators are more effective at promoting social-emotional development when they have access to effective training and consultation and evidence-based curricula. But even with those supports, ECE programs and educators may lack the capacity to fully provide what children and families need, especially recipients who have experienced trauma, chronic stress, or adverse experiences. ECE programs and teachers may need to partner with other community agencies that provide services, such as screening, referrals, and enrollment in programs outside the ECE sector (e.g., mental health, legal, child welfare) (Caringi et al., 2015). Such an approach would be aligned with the way the National Child Traumatic Stress Network conceives of a “trauma-informed child- and family-services system” (Bartlett et al., 2017, p. 8) (see Box 7-8 in this chapter for more).

An example of such a cross-sector strategy to support the multiple domains of children’s development, especially the environments of school-aged children, is through implementation of full-service schools (Zigler and Finn-Stevenson, 2007). Full-service community schools (FSCSs) focus on “integrat[ing] academic, health, and social supports with youth and community development strategies,” (Biag and Castrechini, 2016, pp. 157–158), which is especially critical for children and families

experiencing multiple challenges. “The goal is to more efficiently use resources to bolster students’ learning, strengthen families, and promote healthy communities” (Biag and Castrechini, 2016, pp. 157–158; Blank et al., 2003). By coordinating services at school (by colocating or other mechanisms), community schools try to address service fragmentation and encourage more communication and collaboration among providers and educators (Biag and Castrechini, 2016). There is mixed evidence relating FSCSs with student outcomes. Using longitudinal data from six high-poverty majority-Latino community schools, Biag and Castrechini (2016) examined how participation in a FSCS influenced students’ educational outcomes. The results indicated that participating in a FSCS that included family engagement opportunities and extended learning programs was associated with modest gains in students’ attendance and achievement in math. In another example of FSCS, Whitehurst and Croft (2010) found that the Harlem Children’s Zone did not produce higher academic gains than some other charter schools not identified as FSCSs. These mixed findings are likely due to the variation in FSCSs and their communities (Sanders, 2016), thus indicating a need for more effectiveness studies. Unfortunately, many of the evaluations on FSCSs to date have focused on academic outcomes, which calls for an intentional focus on health and social-emotional outcomes. See Box 7-4 for an example of a promising model that was designed to close the achievement gap by providing wraparound services for families.

Other school and education reform efforts found to have an effect on children’s learning and behavior are the Comer School Development Program (SDP) and the 21st Century Community Learning Centers (21st CCLC). The Comer SDP was developed by James Comer and the Child Study Center at Yale University in 1968 to improve the educational experiences of low-income ethnic minority children. This model includes three mechanisms (School Planning and Management Team, Student and Staff Support Team, and Parent/Family Team); three operations (Comprehensive School Plan, Staff Development Plan, and monitoring and assessment); and three guiding principles (collaboration, consensus decision making, and no-fault problem solving) (Lunenburg, 2011). SDP is implemented in 1,150 schools across the world. Studies of SDP schools show significant student gains in achievement, attendance, behavior, and overall adjustment (Lunenburg, 2011). It is theorized that the SDP model effect manifests through improvement in school climate, indicated by improved relationships among staff and students, collaboration among staff, and central focus on students (Lunenburg, 2011). Quasi-experimental design studies have shown that students in SDP schools in comparison to students in matched non-SDP schools showed significant gains in achievement, behavior, and overall school adjustment (Haynes

and Comer, 1990a,b). Studies have emphasized the importance of implementation of key components of the SDP to find evidence of effectiveness (Cook et al., 1999; Haynes et al., 1998).