8

A Systems Approach to Advance Early Development and Health Equity

INTRODUCTION

Advancing health equity in the preconception through early childhood periods cannot be achieved by any one sector alone. It will take action, collaboration, and alignment across all sectors that frequently interact with children and families and the professionals who serve them. Additionally, better alignment among systems will need to be accompanied by an increase in overall investment in early life: many of the systems best positioned to address early life drivers of health inequities are chronically underresourced, and improved collaboration may only be possible if resources are available to adopt, scale, and spread best practices within a redesigned and better aligned cross-sector ecosystem. There is likely no single, sweeping change that will create a new and better system of care that can address the variety of needs and challenges identified in this report; rather, steady progress integrating and connecting the efforts of the systems already in place, along with improved investments in those systems, will lead incrementally but steadily to improvements in health equity over time. Systems change is not an easy strategy; it seldom yields speedy returns, and it may not be sufficient without an investment of resources designed to take advantage of new and better aligned approaches. However, given that disparities are systematically generated, it is likely a necessary precursor to real and widespread advances in health equity. (See Box 8-1 for a brief overview of this chapter.)

As defined in Chapter 1, systems are collections of interacting, interdependent parts that function as a whole. For the purposes of this report,

most systems are social constructs and organized around a key functional area (e.g., education, health care, criminal justice). Systems have existing patterns and structures that define how people tend to move through them. This chapter summarizes the opportunities to overcome key barriers to strengthen a systems approach, the crucial stakeholders who need to be involved, and the necessary alignment, measures, and research based on the committee’s assessment of the literature in Chapters 2–7 in this report. The committee identified eight crosscutting recommendation areas where multiple sectors need to take action.

Systems Characteristics That Impede Advancing Health Equity

There are many systems characteristics that act as barriers to spreading and scaling up evidence-based and promising programs and approaches to reduce health disparities and advance health equity.

Sometimes barriers are simply financial—scaling programs requires significant and sustained investments in a world with limited resources and many competing priorities. However, the barriers often stem from policy or structural arrangements that could be altered with sufficient political will or from knowledge gaps that could be addressed with appropriate research, well-targeted dissemination, and thoughtfully considered implementation assistance. Some of the key system barriers that prevent moving forward with what is known to work include the following.

Systems Are Designed to React, Not to Prevent

Many systems are designed in response to a challenge or crisis—people are sick or lack jobs—and operate with the primary goal of mitigating the negative impacts of those challenges. Few systems are set up to think ahead to the root causes of the problem and to address those causes, and as a result, resources are applied downstream. In fact, many systems are explicitly not allowed to spend resources upstream (on prevention, for example) because the upstream factors are seen as a different system’s challenge to address, and that other system has its own budget and goals. Current programs and policies are operating in an interconnected world, where one system’s cause is another system’s effect, and the carefully partitioned systems each address only the portion of the problem that falls explicitly within their purview. From the perspective of a life course approach—where failing to invest early means missing critical windows to set positive health trajectories, and the later an intervention comes, the more difficult it is to change negative trajectories—this fractured approach is an impediment to reaching health equity in the preconception through early childhood periods and beyond.

Systems Are Structured to Take the Short-Term View

Currently, systems are poorly structured to incentivize long-term thinking and planning. The pressures of annual budget and performance cycles make investment in long-term gains challenging, and savings are often disincentivized by penalizing systems that reduce costs with a subsequent reduction in payment rates or budget allocations. Often, payments or budgets for systems are based on prior experiences that do not reflect transformed realities. For example, early efforts to integrate behavioral health into primary care faced formidable barriers because payment rates are based on prior experience that does not include many mental or behavioral health services, making transformation extraordinarily difficult to catalyze. From an economic and political standpoint, the benefits of early care and education (ECE) are generally not realized until after children enter school, and sometimes even later in life. Additionally, when the root

causes of poor outcomes are interconnected across systems but the financial stakes are not, misaligned incentives emerge whereby each partner fears they may put in significant work and expense to change an outcome, only to see the savings realized primarily by someone else. As Teutsch and Berger noted, “If everyone is focused only on his own task, no one is responsible for ensuring that our nation’s investments are well utilized, let alone best utilized, to improve health” (Teutsch and Berger, 2005, p. 486).

Systems Typically Have a Singular Focus

A multisystem approach to health equity is difficult when involved systems are primarily built to specialize in one aspect of the health continuum (and whose main goal might not even be health). Which system responds to risks that might generate poor health outcomes, how that work is organized, which system is allowed to address it, and the way funds flow to support a response are all built within highly specialized silos with distinct rules, regulations, strategies, and normative practices. There are relatively few system architectures ready-made to advance cross-sector work and few easy pathways to conceptualize, implement, or pay for it. In addition, those who work within systems might feel a strong sense of special expertise and ownership over their area of focus, which may cause a reluctance to invite others to share hard-earned professional “turf.” Overcoming both the structural and cultural barriers to integrating systems will be no easy task, but structures that align the interests of different sectors—for example, by creating shared savings or other models that reward systems or actors within systems for contributing to one another’s positive outcomes—may help overcome some of these inherent challenges.

Systems Take a Narrow View of the Biological and Social Context

Scientific and institutional systems tend to segment the biological and social; in the context of early life, they are often poorly set up to address the symbiotic relationship between biological development and social context. Even within settings that address health and development explicitly, such as pediatric clinics, there tends to be segmentation of biological risk (assessed by clinicians or pharmacists) from social risk (assessed by social workers or therapists), lacking clear processes for developing a plan for each that is informed by the other.

Systems Undervalue Community Expertise

Current systems tend to value formal knowledge attained through traditional, credentialed academic channels but often undervalue knowledge of culture, community, populations, or other context gained through

lived experiences. Those making decisions about how to serve some communities, or even those providing the service, often do not reflect or live in the communities being served. When the experiences of those most impacted by inequities are not represented in strategies to address them, there is a risk of developing solutions that do not connect with, will not be used by, or do not meet the actual needs of the population for whom they are intended, which may ultimately exacerbate the very disparities that are intended to be addressed.

OPPORTUNITIES TO STRENGTHEN A SYSTEMS APPROACH

Throughout this report, the committee has explored key factors that help set the odds for long-term health and health equity outcomes and made recommendations suitable for actors within key systems and institutions to help improve those odds. While the actions taken by each system identified in this report are important components of improving health equity, one of the committee’s important findings—that the forces driving health inequities are systemic and profoundly interconnected across those systems—suggests that a larger strategy is also needed to advance health equity in the long term. When outcomes are driven by forces that cut across multiple systems, even doing everything perfectly within one system is not enough. Multisector causality requires a multisector response.

Based on the committee’s assessment of the needed changes in Chapters 2–7, the corresponding recommendations contained in each chapter, and its collective expertise, the committee identified eight crosscutting recommendations that need to be adopted by all systems that frequently touch the lives of children and families and the professionals who serve them. These recommendations represent part of a comprehensive strategy for improving the overall system’s ability to address the early-life drivers of health inequity. These strategies draw on the evidence presented in this report and reflect the key insights from the core principles presented in Chapter 1. These recommendations can optimize the impact of the strategies in this report and create a framework where what is known to work can be made to work for more people, under more circumstances, and with a greater overall impact on health equity.

Support Cross-Sector Initiatives Across the Health Continuum

Achieving health equity is a systems challenge. It will not be improved solely by developing and deploying programs aimed at individuals experiencing poor outcomes—until the root causes are addressed, negative health outcomes will persist. Young people experience adverse and positive exposures that cumulatively help shape their odds for good health over the life course, but within systems, those exposures occur at

systematically different rates for different groups of people. They also intersect profoundly—the early-life exposures and experiences that shape health are multidimensional and fall under the purview of multiple social and cultural systems (see Chapters 2 and 3 for more information). These different exposures and experiences result in different cumulative odds for good health over the life course, odds that are ultimately expressed in the form of disparate outcomes between groups.

Early efforts to adopt cross-sector approaches were often impeded by the challenges of data sharing. The regulatory structure that governs data use and data privacy offers important protections for individual consumers, but it was also largely developed without considering the limitations it might place on cross-sector interventions by communities seeking to collectively address complex problems with roots in multiple systems. The distinct regulations for different sectors (e.g., Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 in health care and Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 in education) have different criteria for data use, and while some allow data to be combined for the purposes of research or evaluation, there are few legal pathways available to make operational use of cross-sector data in ways that would help co-manage common populations or address common root causes with coordinated, cross-sector approaches. By providing a regulatory architecture to support data sharing between the key systems identified in this report, policy makers and systems leaders could dramatically improve communities’ ability to adopt, scale, and spread cross-sector interventions.

A second key challenge of cross-sector work stems from how public dollars are organized. Resources tend to be allocated in a siloed manner: this money is for health care, that money is for education, and so on. In general, most systems have strict administrative rules on how their funding can be spent and limited ability to direct it at work that occurs outside of their system, even if that work is critical to that same system to achieve its desired outcomes. However, in reality, these issues are not confined to the convenient boundaries within which finances are organized, and if the problem that is creating poor outcomes for a system does not happen to fall within its boundaries, that system is left with only a limited ability to address it. Creating pathways for funds within a system to flow to activities outside the system, especially when there is strong evidence that those activities will result in improved outcomes, is critical to building effective cross-sector initiatives. A recent example of this is an effort under way by health care provider Kaiser Permanente—it plans to spend $200 million on fighting homelessness and building more low-cost housing in eight states, plus Washington, DC.1

___________________

1 See https://about.kaiserpermanente.org/community-health/news/kaiser-permanente-announces-three-initiatives-to-improve-communi for more information (accessed April 16, 2019).

In addition to allowing for investments across sectors, it is important to consider how any savings generated by those investments might be shared. In the absence of shared savings models, a “wrong pocket” problem is often created, whereby system partners fear they may invest in the work only to see the outcomes or savings accrue to others. There are currently few validated methodologies for measuring shared savings—especially given the data-sharing challenges that have already been highlighted—or mechanisms for capturing those savings and distributing them among the participating partners. Making headway on shared savings models could help create powerful aligned incentives that help cross-sector initiatives create, sustain, and spread their work. One strategy to address this problem is to develop and test shared savings models that allow sectors whose work helps the outcomes in another sector “share the savings” generated by that work. This would help create aligned incentives that acknowledge intersectional causes and reward intersectional work.

Finally, licensure and certification requirements vary dramatically across fields; in many emerging fields, they are virtually nonexistent. However, services that impact health are sometimes also delivered by paraprofessionals, peers, or other workforces that either lack formal professional licensure standards or use standards that are not recognized by larger, more established systems that would pay for such services (IOM, 2001). Payment rules for many systems often require more traditional certification, so this barrier hinders using nontraditional workforces, which may be closer to the communities being served and could have similar lived experiences, to deliver services that help create health within the context of collaborative cross-sector work.

While there has been significant work around the key components necessary to establish successful cross-sector initiatives (see examples in Chapters 5, 6, and 7), a number of key barriers remain, including cultural, ideological, or normative barriers around perceived ownership of specific content areas that may limit cross-sector communication and cooperation that policy makers and leaders can help address.

These initiatives could include collective impact strategies, Accountable Communities for Health,2 Health in All Policies3 initiatives, or other models of aligned, cross-sector community action in service to shared health and health equity goals. (See Chapter 8 of the 2017 National Academies report Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity for more information on Health in All Policies and other collective impact strategies to foster multisector collaboration.)

Enhance Detection of Early-Life Adversity and Improve Response Systems

As discussed throughout this report, adversities in early life—including adverse childhood experiences and other adverse experiences or exposure to key social determinants of health (SDOH), such as housing instability or food insecurity—help set the odds for poor health outcomes later in life. Early-life adversity is especially important for a number of reasons: first, it occurs at points of high plasticity for key biological systems that shape health over the long term; second, it occurs during a period of critical development in the social, emotional, and cognitive domains of self; third, it increases the likelihood of additional exposures to adversity later in the life course; and fourth, it may impact future resilience to additional exposures (see Chapter 2 for more information). Early adversities make a negative health trajectory more likely; left unaltered, such trajectories will play out across decades and result in differences in health outcomes within and across generations. Early detection and rapid response are essential to help mitigate the long-term effects of exposure to adversity by adjusting the trajectories back toward positive health as early as possible.

Early detection and rapid response would require a number of steps across systems, such as developing and promoting screening tools and procedures that can be adopted, implemented, and scaled to improve monitoring and fast reaction. Screening approaches that can be adopted within

___________________

2 “Accountable health initiatives, most commonly referred to as accountable communities for health (ACHs), have been implemented nationwide in response to or as a result of contributions from state innovation model grants and community transformation grants, through collaborations with state Medicaid programs, or through other policy and financial incentives” (Mongeon et al., 2017). They bring together partners from health, social service, and other sectors to improve population health and clinical-community linkages within a geographic area (Spencer and Bianca, 2016).

3 “Health in All Policies is a collaborative approach to improving the health of all people by incorporating health considerations into decision-making across sectors and policy areas. The goal of Health in All Policies is to ensure that all decision-makers are informed about the health consequences of various policy options during the policy development process” (Rudolph et al., 2013, p. 6).

and connected across settings, such as the health care and early learning systems, and that make frequent contact with young families during the first years of a child’s life are especially critical because they represent the best opportunities to detect early and act decisively in response.

Professionals who frequently interact with children and caregivers—clinicians, teachers, or personnel in social service or other agencies, for example—need training to understand the effects of early-life adversity and the associated toxic stress response on the physiological and psychosocial development of young people. These trainings need to move beyond awareness training to include how to respond effectively within the context of their field and how to refer across sectors when needed.4 Dedicated staff are also needed to help professionals refer children and families to services outside of that system (e.g., social workers embedded within the relevant systems). These professionals need to know how their approach to treatment or service provision will vary based on the results of a child’s adversity screen. (See below for more on transdisciplinary needs.)

It is also necessary to develop rapid response or referral systems that can bring a range of community resources to bear when early-life trauma and adversity is detected. These systems should include information and service pathways and the ability to “close the loop” back to the referring agency or partner so that responses are coordinated across the continuum of health. Accomplishing this will require changes to regulatory limitations on how data can be shared across sectors or between professionals with different qualifications and licensure systems.

Rapid response and referral systems will require implementing and scaling screening across key settings, enhancing trauma response training, and ensuring support for these systems.

___________________

4 For example, the Alberta Family Wellness Initiative in Canada has developed a “Brain Story Certification Course” that teaches the foundational science of brain development to help professionals in all fields who interact with families with children. See https://www.albertafamilywellness.org/training (accessed July 19, 2019) for more information.

Develop Adversity and Trauma-Informed Systems

Early-life trauma and adversity are key factors that help set the odds for poor health outcomes across the life course, but how systems respond to that trauma is nearly as important. Once adversity or trauma occurs, it cannot be erased. However, its effects also are not destiny: effective services can help mitigate the impact of adversity on health across the life course. Most systems are designed to capture discrete data elements about their service domain, but exposure to social adversity or trauma is often contextual, captured via narrative interactions with patients or clients. These are also sensitive personal data with additional layers of privacy protections. Because these data are not easily shared within or across systems, however, people seeking help at multiple points of service often have to tell the story of their trauma over and over again. Mechanisms that allow service providers to have the needed data and context about their clients at the point of care could ensure that their service options are appropriate to clients’ financial, social, cultural, and personal situations. For example, when service options are presented that require resources a client cannot possibly access (e.g., financial cost-sharing, transportation), the client’s status as an “outsider” is reinforced. When systems have mechanisms to meet clients where they are, clients will be more supported and understood and be more likely to adhere to recommendations, remain engaged with the system, and receive the help they need.

Many clients feel distress not just from past life events but from interactions with the system itself: they feel unwelcome or stigmatized when they seek services due to their race, poverty, sexual or gender identity, or other factors. It is critical to train service providers on discrimination and stigma to ensure all persons feel welcome receiving services in any setting, so that they will engage in and benefit from those important services. As noted in Chapter 7, trauma-informed care (TIC) and implicit bias training reflects the understanding that a child’s or family’s behavioral or health challenges are often due to experiences of toxic stress and undiagnosed and untreated trauma, and with implicit bias among those they interact with in the education or other systems. Furthermore, systems delivering services to people with traumatic histories are also at risk of retraumatizing clients if they do not act in a trauma-informed manner. There are strategies for TIC that can be used to prevent and mitigate the impact of implicit biases (see Chapter 7 for more strategies and Recommendation 8-8 for research needs on this topic). Furthermore, harmonizing eligibility criteria across programs and systems is needed so that when children or families experiencing trauma or adversity enter a system, professionals can take a holistic perspective and refer them to cross-sector services; children and families would also be more likely to be eligible for needed services in other systems.

Build a Diverse, Culturally Informed Workforce

Building a high-quality health, early learning, or social services system will not improve outcomes if people do not engage with the system(s), and the populations where health inequities are most strongly expressed are often the least likely to engage in systems designed to serve them because they have not historically felt welcomed in those systems. Most systems are built to specifications that are responsive to dominant culture norms and practices, but there is no perfect system that works for everyone. Systems need to move beyond what works and address the question of what works for whom, and under what circumstances? Some communities may prefer to receive care and services via alternative modes; in a manner of their choosing; or from providers who look and speak like them or understand their unique cultural or community identity. Offering services to caregivers and children in culturally and linguistically appropriate ways is critical to ensuring that good systems exist and that the people who have historically had the poorest outcomes engage in these systems as partners in generating health.

System actions to offer culturally and linguistically appropriate services include training service providers to be attuned to and respect cultural and other identity differences and ensuring that systems have a range of appropriate linguistic services available for providers. Furthermore, systems that ensure that signage, forms, and data processes that clients use are available in multiple modes and languages facilitate participation in these systems. Another system action relates to the integration of workforces across sectors in the early-life period. Complementary disciplines can be drawn from to create teams that promote transdisciplinary service delivery. This might include traditional service providers and the expanded use of paraprofessionals, community health workers, peer support specialists, parent advisors, or others who bring expertise in, and lived experiences that are relevant to, the communities or populations being served. Bringing transdisciplinary providers together

is just the first step; standards and workflows that allow these teams to collaborate effectively may need to be developed so that each functions at the top of its license to provide comprehensive wraparound support for families that need it.

Another system action is expanding the workforce in early-life-serving sectors to ensure that service providers reflect the diversity of their communities and that people of diverse racial, ethnic, cultural, sexual orientation, gender expression, or other identities have access to more service providers who look like them and reflect their experiences. This could be accomplished through mentoring programs, outreach into culturally specific communities when recruiting or hiring, or scholarship programs to “plant the seeds” to introduce more diverse communities into fields where some communities are underrepresented.

Align Across Systems to Enhance Early-Life Supports for Caregivers

Parental and caregiver supports are critical for promoting prosocial attachment, nurturing, and healthy family relationships that foster the healthy development of youth (see Chapter 4). Supporting caregivers should be an essential goal of multiple systems (e.g., caregivers who do not have to worry about access to health care have a better opportunity to remain healthy and maintain positive relationships with their children, caregivers with adequate housing may experience reduced strain and be better able to bond with their children, and caregivers whose children are receiving effective early-life education and developmental supports may feel better equipped as effective and engaged parents).

Better support for caregivers will increase the likelihood of positive nurturing relationships between caregivers and children, and improvements in the multiple systems that are touch points for children and families should explicitly address caregiver support. Such changes may include encouraging the development of programs and policies that provide support for the whole family unit, including parents, children, and other important members of the family’s extended caregiving system. Strategies include moving away from segmented policies, such as those that consider eligibility for supports or services separately for parents

and children (e.g., child-only health insurance versus a family plan), and instead consider programs that incorporate or leverage the extended family unit or other close social networks.

Another strategy is enacting policies and programs that provide assistance to families without requiring a separation between caregivers and children that might negatively impact attachments and family functioning, especially in early life. For example, programs could offer families with young children certain financial or other assistance that does not include extensive requirements to leave the home in order to work or perform other tasks, which reduces the opportunities for developing, maintaining, and supporting healthy family attachments and functioning. (See Chapter 6 for examples.)

Efforts could be promoted to create wraparound services for families with greater needs, offering multiple types of assistance designed to support caregivers along a variety of dimensions within a single program or setting, even or especially if those services come from traditionally segmented or siloed systems in the community. Bundled services require less time for caregivers to navigate the systems, allowing more time for them to focus on effective caregiving. (See Chapters 4, 5, and 7 for examples of integrated and wraparound care.)

Support Integration of Care and Services Across All Dimensions of Health and Community

Integration refers to establishing standards by which services are delivered in ways that break down traditional silos and are informed by and responsive to the intersection of health and the key drivers of health. This might include social domains (such as social support, cultural identity, or community cohesion; see Chapter 4), clinical domains of health (such as physical, mental, behavioral, or dental health; see Chapter 5),

economic domains (such as income, housing stability, or food security; see Chapter 6), and educational domains (such as access to high-quality ECE programs or others; see Chapter 7). Integrated service models cohesively connect and align along the health continuum, address health holistically, and often include both primary prevention designed to forestall health crises, and screening and response systems designed to act quickly when needs are identified.

A whole-family approach calls for integrating services at the point of care or intervention. Thus, the committee’s vision for programs and services is that families have access to an array of clinical, early educational, family developmental, and psychosocial support and economic help in their communities. Rather than fragmented programs, the vision calls for easy and coordinated access across the breadth of needed services for households—viewed from a life course perspective and one that ensures equity in access and use. Achieving this integration takes substantial work and community leadership, with programs having only limited incentives to collaborate, share accountability, and pool resources across sectors. The 2017 National Academies report Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity provides principles and examples of integration at the community level (NASEM, 2017).

Integration and whole-family clinical care models are one example. This could include integrating the delivery of clinical care to include physical, mental, behavioral, and dental health services and connecting clinical care with other services for families (nutrition, early childhood programs, housing) either through a “one-stop” colocation strategy or a seamless and easy referral process with strong information sharing, “warm” handoffs between providers, and a “no wrong door” policy that helps people get whatever help they need easily through any entry point.

New models that integrate services to address the SDOH should follow this model. These include service delivery models that integrate supports across a range of SDOH, especially housing, transportation, food security, and social support, with a particular focus on family social supports and programs that integrate informal social networks into the health care, ECE, and services ecosystem (see Chapter 5 for recommendations on this for the clinical care system and its connections to other sectors). Another strategy is integration across settings and sectors, such as establishing community centers that include health care, nutrition, parent education, and resources to identify social needs and adversity and to help families find resources, or supporting church- or community-based programs, such as health care/community partnerships (see Chapter 5 of NASEM [2017], for in-depth examples of these types of partnerships), to extend the reach of health or social service programs into culturally specific or otherwise historically underserved communities.

Support Payment Reform to Allow for Upstream Investment

Payment structures have a profound impact on how resources are invested and the ability to address complex, interrelated causes of poor health using multisector approaches. In many sectors, payment remains tied to the delivery of a service rather than its success in achieving an intended outcome, creating incentives to focus on the processes of providing services and maximize the associated billing of those processes rather than on creating better health outcomes. Similarly, the regulatory structure that governs how funds flow within and across systems is a major impediment to both cross-sector work and the spread and scale of interventions or programs that are known to succeed. As noted earlier, nearly every major system or sector has its own regulatory and/or funding structure, which is primarily designed to ensure accountability to spending within that system; there are usually rules that ensure the money within a sector stays within that sector. Accountability policies can also discourage upstream investment. For example, in the education system, schools and districts are not held accountable for school outcomes until 3rd grade at the earliest, which creates disincentives for school leaders to invest in the early grades or before kindergarten.

Another strategy is to move to payment models that attach payment to the value of a provided service or its desired outcome rather than to the delivery of the service. Value-based structures promote efficiency and impact over quantity of services and encourage upstream investment to address root causes rather than downstream work to deliver services. Payment models that emphasize upstream investment have substantial focus on prevention in health care, ECE, and community services. In many cases, as documented in earlier chapters, the downstream payoff may come much later, sometimes years later.

Finally, there is a need to rethink budgeting and contracting to address the “success penalty” problem. For systems that contract with government, budget and contracting policies often set reimbursement rates or budgets by examining expenditures versus costs in previous years. When systems invest upstream and reduce costs, they risk being penalized by

having their budgets reduced or rates cut the following year, thus dis-incentivizing success. Models that allow successful systems to reinvest some portion of saved dollars into scaling and spreading the approaches that helped them achieve that success will incentivize change.

Support Transdisciplinary Research on the Complex Pathways of Health Equity

As described in this report, a tremendous amount is known about what works to advance health equity in early development (and the lifelong benefits of doing so), but there are still many unknowns in the area of implementing and scaling up interventions. Many interventions have shown promising results at small scale but have not been fully tested across multiple settings or in diverse communities and populations. Others have promising preliminary data but little high-quality evidence. The evidence around systems and policy changes—the work needed to address inequities with a multisector and systems-based approach—remains less certain than programmatic evidence in many cases precisely because it is complex and set in shifting environments that make it challenging to confidently attribute effects. There is also a relative dearth of research on heath equity produced through genuinely participatory methods that authentically engage the communities and populations most impacted by health inequities to help formulate, conduct, interpret, and disseminate results to community members, advocates, policy makers, and other decision makers.

The committee has identified important research needs in this report relevant to the chapter topics (see Recommendations 2-2, 4-1, 4-2, and 4-3); here, however, the committee recommends strategies focused on how to conduct research differently to help translate science to action across sectors, including needed data to inform subgroup analysis and to elucidate the complex causality related to health inequities to better target interventions across sectors. Recommendation 8-8 also identifies research needs that would support strategies identified throughout this

report and relate to all systems that frequently interact with children and their families (e.g., research on addressing discrimination, structural racism, and implicit bias training), and calls for an increase in participatory methods that engage communities, especially historically marginalized or excluded communities, as partners in research on health equity.

An important caution, however, is that although more targeted research is needed, enough is already known to act now to advance health equity in the prenatal and early childhood periods—this has been made abundantly clear in the preceding chapters of this report. The research recommended below is important to continually improve efforts and increase impact, but this should not impede action at the federal, state, tribal, territorial, local, and community levels. Here, the committee provides guidance on charting the course for future research to better meet the needs of the nation’s children in the future and, specifically, to advance health equity.

Research Methods

- Explore alternative methods to address complex causality. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are often considered to be the gold standard for scientific evidence, and they remain a valuable tool (see Chapter 1 for more on their strengths and limitations). However, RCTs are not designed to assess the complex, interconnected causality that lies at the heart of health equity—if anything, they excel at reducing or controlling for complexity to isolate a single cause. It is necessary to embrace new approaches, including data science/data mining, multilevel modeling, integrated mixed methods, rapid-cycle analysis,5 and other methods designed to employ a wide range of data and evidence to uncover

___________________

5 For example, the Frontiers of Innovation platform at the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University employs a “structured but flexible framework that facilitates idea generation, development, implementation, testing, evaluation, and rapid-cycle iteration” (see https://developingchild.harvard.edu/innovation-application/frontiers-of-innovation for more information [accessed July 1, 2019]).

- the most effective approaches. Additionally, research needs to move beyond assessing cause and effect to explore the mediators and moderators of differential effectiveness—to identify not only what works, but what works for whom, and under what circumstances—to pursue a deeper understanding of causality that facilitates the ability to adapt promising and evidence-based models to optimally fit the needs and priorities of diverse populations.

- Expand research into individual differences (heterogeneity) in response to adversity and treatment. Many programs have shown some impact on important health outcomes; yet, in many cases, the effect sizes have been small to moderate. In part, this reflects the differential vulnerability and response to adversity and the differences in response to interventions. Studying heterogeneity in context and how it shapes responses to interventions and promising programs is a critical component of actionable research, but current knowledge to identify these differences is limited. Exploring and understanding these differences will enable more targeted and tailored interventions.

- Promote scientific research that includes individuals and families from underrepresented communities. Even programs with a good evidence base often rely on studies that were conducted in dominant culture settings or with communities that are not representative of the full range of diversity (see Chapter 4) of characteristics such as race and ethnicity, socioeconomic or immigrant status, or sexual minority parent status. Studies are needed that seek to not only understand what works but to move beyond top-line findings to explore variation in outcomes across populations, settings, and subgroups (see Chapter 4 for a discussion on subgroup variation)—what works for whom, and under what circumstances. The results can be used to target efforts to address inequities more precisely in contextually informed ways. This scientific work should be informed by appropriate theoretical frameworks that take into consideration the multifactorial nature of early childhood development in diverse populations. Members of these populations or scientists with extensive research and/or clinical experience working with these populations should be part of the investigative teams.

Research Content

- Promote research that explicitly seeks to understand the interconnected mechanisms of health inequities. Health equity has

- complex, interconnected root causes—factors that unfold across the distinct systems highlighted in this report—and also complex, interconnected mechanisms by which those factors shape health outcomes differentially across the life course. These mechanisms include biological development, social-psychological development, and differential opportunity structures and choice architectures that life presents people based on their circumstances. In addition, the biological and psychosocial responses to these mechanisms vary across the life course, with some developmental periods of high plasticity offering critical windows for establishing long-term trajectories for health outcomes. Understanding the root causes of inequities allows actions to be taken to prevent them; understanding the mechanisms by which root causes shape inequities helps promote more effective intervention when prevention is less than perfect, and understanding variation in responsiveness to those mechanisms across the life course will help ensure interventions are optimally targeted for maximum impact.

- Support research that addresses discrimination and structural racism. There is an urgent need for research on the structural roots of racism; how to stem the development of negative societal stereotypes, attitudes, and implicit biases; how to change those biases once they are formed; and how to develop applications of that knowledge that can help reduce discrimination. The impact of these forces—both the negative belief systems themselves and their structural and historical roots—on health and health outcomes are keenly felt, but there are few proven tools that allow for effective response.

-

Support research for trauma-informed care and implicit bias training. As discussed in Recommendation 8-3, TIC and implicit bias training are critical tools for advancing health equity in the preconception through early childhood periods. However, that research base needs to be expanded further. Regarding research on structural racism and implicit bias, the 2017 National Academies report Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity provided the following recommendation on this topic, and the committee endorses it:

The committee recommends that research funders support research on (a) health disparities that examines the multiple effects of structural racism (e.g., segregation) and implicit and explicit bias across different categories of marginalized status on health and health care delivery; and (b) effective strategies to reduce and mitigate the effects of explicit and implicit bias.

-

There have been promising developments in the search for interventions to address implicit bias, but more research is needed, and engaging community members in this and other aspects of research on health disparities is important for ethical and practical reasons. . . . In the context of implicit bias in [schools], workplaces and business settings, including individuals with relevant expertise in informing and conducting the research could also be helpful. Therefore, teams could be composed of such nontraditional participants as community members and local business leaders, in addition to academic researchers. (NASEM, 2017, p. 115)

- Support systematic dissemination and implementation research. In many sectors and increasingly across sectors, there are numerous well-tested examples of what works to help young families and improve outcomes. Enhancing and improving access to these programs will benefit from an extensive program of dissemination and implementation research to bring them to scale. Furthermore, a mechanism to capture what has been tested but does not work is needed.

Measuring Success

Disparities have been measured for a long time and show the outcomes of inequity. What is lacking are good tools for measuring the various systemic and personal factors that influence and interact in complex ways to shape health outcomes over the life course. In the absence of such measures, designing the right kinds of system change remains a challenge.

The committee has identified a number of measures and indicators that can currently be measured and are important for tracking progress within each of the systems that act as key leverage points for early childhood development. For example, measures for primary caregivers include maternal depression and stress, parental feelings of rejection or hostility to the child, and support for mothers/primary caregivers. For children, measures include infants born at low or very low birth weight, breastfeeding at 6 months, blood lead levels, social-emotional learning, meeting expectations in language development (e.g., measures of vocabulary), and kindergarten readiness. Measures for families include poverty (using the Supplemental Poverty Measure), food insecurity, homelessness, health care insurance coverage, and exposure to toxicants through the home or early care environments. Taken together, improvements in these key metrics would represent systems that are moving in the right direction to address early-life drivers of inequities. However, other measures will be needed that are not yet available; the following section outlines these.

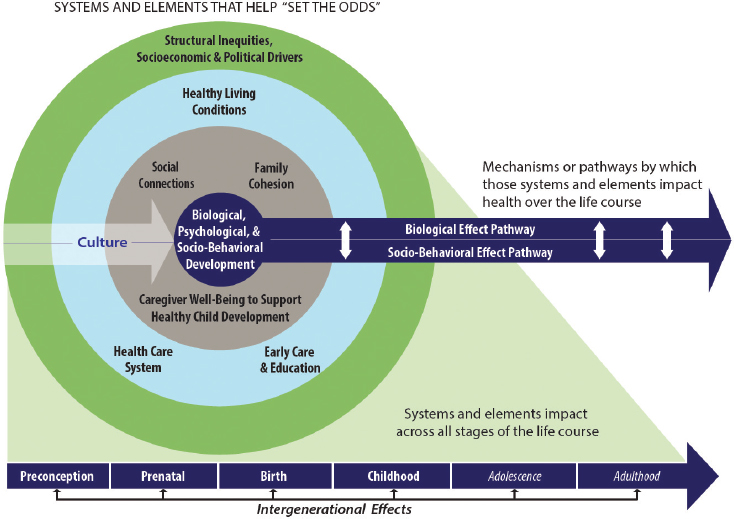

The committee’s conceptual model in Chapter 1 identifies two important dimensions to consider when exploring the early-life drivers of health inequities: the key systems that play the largest role in helping “set the odds” for healthy development and the interrelated mechanisms or pathways by which the influence of those systems are expressed into health outcomes over the life course (see Figure 8-1).

The model leads naturally to several important insights about measurement. First, the systems that set the trajectory for health are explicitly connected and nested in the model—a child’s biological, psychological, and socio-behavioral development (innermost ring) is nested within family and caregiver social systems, but those systems exist within and are shaped by key institutional systems like health care or ECE, which in turn exist within and are shaped by structural inequities and other historical, political, or macroeconomic forces. This means it is not enough to just have a good measure of caregiver attachment or access to health care—it is necessary to have good measures of how those constructs interact to collectively set the odds of healthy early-life development and why systems present some populations with a greater or lesser probability of exposure to those constructs.

NOTE: The elements and systems included in the nested circles impact every stage of the life course.

The mechanistic pathways by which those constructs act to shape health across the life course are also complex and interconnected. They might act via a biological pathway, whereby events or exposures that occur in childhood result in changes to key neurological or other biological systems that act over the years to enable or impede good health. They might also act via a socio-behavioral or psychological pathway, whereby events or exposures that occur in childhood change the likelihood that other events or exposures will occur later in life, alter the way people formulate their own identity or move through and react to key systems, or result in differences in the kinds of opportunities or choices that life ultimately presents to someone. Crucially, these pathways are far from mutually exclusive: things that happen in one may profoundly impact another in positive and/or negative ways. This makes subgroup analyses based on the biological dynamics of the SDOH difficult.

None of this is deterministic. Rather, the committee conceptualizes health equity as a probabilistic challenge, with each element in the model contributing some adjustment to the odds of experiencing healthy development in early life and continued good health across the life course. Each factor contributes a probability that someone experiencing that factor will have good health outcomes; a person’s overall odds of experiencing good health are a cumulative function of all of those probabilities. When populations experience different rates of exposure within systems for any reason, their cumulative odds will systematically differ. Even though the odds are not individually predictive—a given person may or may not “beat the odds” and experience any particular outcome—when applied to populations and expressed over time, different odds play out as systematically disparate outcomes between groups of people.

There is also a need to learn from and continuously collect data on both intervention successes and failures to better understand which program elements do or do not work for which subgroup populations. In light of this approach to understanding health equity, more robust measures are needed:

Understanding and measuring cumulative exposure. In this report, the committee identified a number of key factors that impact early-life development, ranging from influences in the microsocial or family environment, such as attachment, nurturing, and maternal well-being, to institutional levers, such as access to prenatal care or effective responses to trauma exposure, to macrosocial forces, such as racism and poverty. There are good tools available to measure exposure to some of these factors, but there are few methods for empirically understanding how exposures to risks or protective factors accumulate and combine over time to establish a cumulative overall risk profile. In the absence of a means to measure

cumulative exposure, there is a lack of “math” for how to most effectively intervene when exposures occur.

Understanding the interaction among developmental pathways. Significant gains have been made in understanding how biological processes react to some contextual exposures—for instance, in the areas of science of trauma and toxic stress. However, there are few frameworks for understanding the multidirectional relationship between the biological, social-behavioral, and psychological development of young children. In particular, it is critical to understand how that interaction may vary across the life course in response to changing plasticity of biological systems, different stages of personal and cognitive development, and different life conditions and accumulated experiences in order to build a health equity strategy that puts the right responses in the right places at the right points of optimal potential impact.

Measuring interactions between systems. There are good methods for measuring how distinct elements of systems or policies impact health outcomes—for example, assessing whether systems with a given feature tend to produce better outcomes than systems without it. But understanding the dynamic interplay between systems—how a design decision in health care might interact with an economic policy or early learning curriculum to cumulatively shape the odds of good health—is not as developed. Models that can estimate “integrated risk” by combining key data from across the sectors where people live their lives are needed. Similarly, measures that examine results from cross-sector collaboration can help in documentation and accountability. As an example, school readiness at age 5 reflects both a child’s health status and the family’s access to basic income and housing, prevention of early adversity through support of maternal well-being, and community early education systems. Other measures, including variability in high school completion, 3rd-grade reading readiness, unemployment, or arrest rates, may hold similar multisector significance as a lens on equity, though more work is needed to understand how measures like these ripple through the health continuum to impact disparities measures within other connected systems.

Improving methods to assess complex causality. As outlined in Recommendation 8-8, perhaps the biggest challenge facing health equity research is that of complex causality. As noted, many of the preferred tools of science, such as RCTs, are designed to control for and isolate single causes rather than embrace complex, interrelated causality that may include multilevel, multidirectional, and nested effects. For example, there needs to be greater exploration of effective community-based

intervention approaches that use existing resources (e.g., as in “natural experiments”).

CONCLUSION

These measurement needs represent a significant barrier to advancing the understanding of the biological and social pathways by which early life experiences are translated into health inequities, and the committee calls for improved measurement and research methodologies that can advance the state of the science and better inform effective societal responses. However, as noted earlier, there is no reason to wait for the science to solve all of these challenges before taking action. There are systemic disparities in health outcomes between populations, and the groundwork is laid for those disparities in early life. There are many solutions available to start now (see Chapters 4–7 and the system-level recommendations in this chapter). Measuring progress and refining approaches needs to continue, but there is no reason not to deploy the tools that are already available. Chapter 9 summarizes these actions and the key principles discussed in this report that provide a roadmap to advance health equity in preconception through early childhood.

REFERENCES

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Improving the quality of long-term care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Mongeon, M., J. Levi, and J. Heinrich. 2017. Elements of Accountable Communities for Health: A review of the literature. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. doi: 10.31478/201711a.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Rudolph, L., J. Caplan, K. Ben-Moshe, and L. Dillon. 2013. Health in All Policies: A guide for state and local governments. http://www.phi.org/uploads/application/files/udt4vq0y712qpb1o4p62dexjlgxlnogpq15gr8pti3y7ckzysi.pdf (accessed July 12, 2019).

Spencer, A., and F. Bianca. 2016. Advancing state innovation model goals through Accountable Communities for Health. Center for Healthcare Strategies. https://www.chcs.org/media/SIM-ACH-Brief_101316_final.pdf (accessed July 12, 2019).

Teutsch, S. M., and M. L. Berger. 2005. Misaligned incentives in America’s health: Who’s minding the store? Annals of Family Medicine 3(6):485–487.