1

Introduction

In a well-known public health parable—the upstream–downstream story, credited to medical sociologist Irving Zola—the story’s protagonist is standing alongside a river that is slowly filling with drowning people. The protagonist starts pulling each drowning person from the water, but finds the pace of saving drowning people an impossible one to keep. More importantly, the immediacy of the need also prevents the protagonist from traveling upstream to determine how these people have come to be in the river at all (McKinlay, 1979). This parable represents a fundamental challenge facing the U.S. health care delivery system, which largely focuses on downstream activities. The health care delivery system is primarily focused on providing medical interventions to treat or prevent disease, but is not currently equipped to systematically address the many upstream factors that contribute to illness and poor health care outcomes.1

While the upstream-downstream story is often interpreted as enjoining clinicians to focus on disease prevention as well as treatment of acute or chronic illness (e.g., focusing on the role of diet, physical activity, and tobacco use in the onset of heart disease, rather than only focusing on the treatment of heart disease that may occur as a consequence of these behaviors), more contemporary interpretations have suggested the need to move even further upstream. Taking the social conditions in which an individual lives, works, and plays into account is critical to improving both primary prevention and the treatment of acute and chronic illness

___________________

1 For a detailed look at supporting data, see Bradley and Taylor (2013).

because social contexts influence the delivery and outcomes of health care as well as individual health-related behaviors (Bravemen et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2008).

A large and growing body of evidence suggests that these upstream social resources—such as access to stable housing, nutritious food, and reliable transportation—contribute to health outcomes (Dzau et al., 2017a; Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017; Kaiser and Cafer, 2018; Williams et al., 2008). For example, people of lower socioeconomic status (SES) have a higher burden of poor health than those of higher SES (Adler and Rehkopf, 2008; Bor et al., 2017), including both a higher prevalence of most diseases and worse outcomes (Daly, 2014). Such health inequities are unnecessary, avoidable, and unjust and are not explained by differences in access to medical services or by individuals’ genetic and behavioral factors (Heiman, 2015; NASEM, 2019b). Improving social conditions is likely to reduce health disparities and improve the health of the overall U.S. population (Abbott and Elliott, 2017; CDC, 2018).

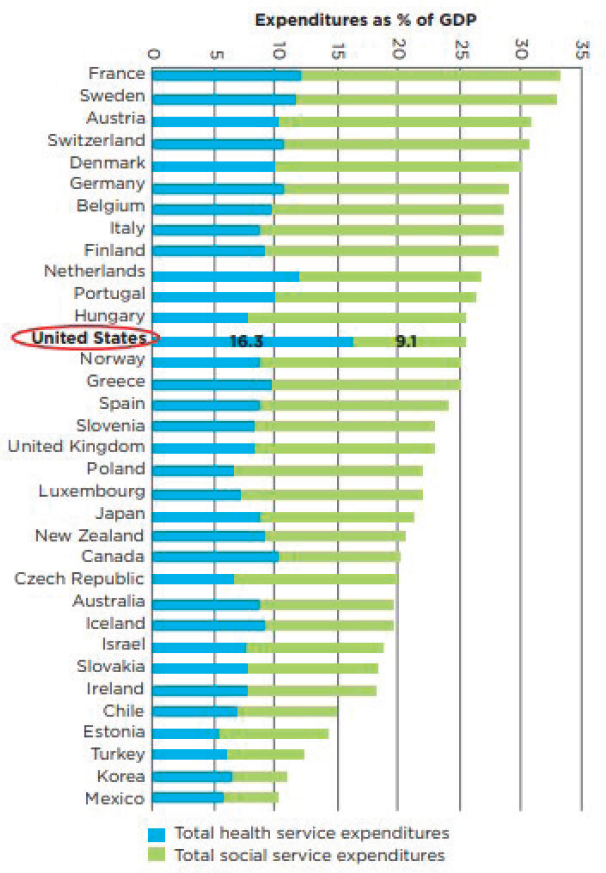

Changes both at the societal level (possibly requiring changes in national law and policies) and at the patient level (requiring the provision of social care) are necessary to improve social conditions. As an example, though many other industrialized nations spend less per capita on medical services that the United States does, they spend a larger proportion on social services relative to medical services, and their residents have better health and lead longer lives (Bradley et al., 2017; NRC and IOM, 2013; Papanicolas et al., 2018; Squires and Anderson, 2015) (see Figure 1-1).

This report explores how a range of health care sector activities can be focused on improving social conditions as components of a comprehensive strategy to improve the nation’s health and well-being. The United States is not alone in examining how to provide care for the whole needs of its population. For example, the United Kingdom’s National Health System is moving forward with integrating its health and social care systems (NHS, n.d.).

The charge to the study committee is presented below, followed by a description of the committee’s approach to its charge. Next, background information is given on how social, economic, and environmental factors influence health. Last, a roadmap to the rest of the report is provided.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

A broad coalition of foundations, social work associations and educational institutions, and other organizations came together to develop the Statement of Task that the committee was charged with addressing. The committee’s task was to examine the potential for integrating services addressing social needs and the social determinants of health (SDOH)

SOURCE: Adapted from The American Health Care Paradox: Why Spending More Is Getting Us Less by Elizabeth H. Bradley, Lauren A. Taylor, and Harvey V. Fineberg, copyright © 2013, 2015. Reprinted by permission of PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

into the delivery of health care in order to achieve better health outcomes and to address major challenges facing the U.S. health care system. These challenges include persistent disparities in health outcomes between the overall population and certain vulnerable subpopulations, often defined by age, race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, disability status, sexual orientation, SES, family caregiver status, immigrant status, or geographic location. In this report the committee discusses: (1) approaches currently being taken by health care providers and systems and also new or emerging approaches and opportunities; (2) the current roles of different disciplines and organizations as well as new or emerging roles and types of providers; and (3) current and emerging efforts to inform the design of an effective and efficient care system that will improve the nation’s health and reduce health inequities. In creating its report, the committee considered the

- Current scope and conceptual underpinnings of health-related social needs care,2 including (a) the roles of providers such as social workers, gerontologists, physicians, psychologists, nurses, community health workers, and trained volunteers; (b) linkage to community-based organizations and services; and (c) the role of hospital community benefits.

- Current state of the social needs care workforce in preventing, controlling, and treating health-related conditions (e.g., disciplines providing social needs care and their professional qualifications, the breadth of settings, and roles for such care, including administrative, policy, and research roles; current training for each discipline related to the provision of social needs care; and projected workforce needs to meet demographic changes).

- Evidence of impact of social needs care on patient and caregiver/family health and well-being, patient activation, health care use, cost savings, and patient and provider satisfaction.

- Opportunities and barriers to expanding historical roles and leadership of social workers in providing health-related social needs care and the expanding role of other types of providers, such as gerontologists.

- Emerging and evidence-based care models that incorporate social workers or other social needs care providers in interprofessional care teams across the care continuum (e.g., acute, ambulatory, community-based, long-term care, hospice care, public health, care planning) and in delivery system reform efforts (e.g., enhancing

___________________

2 The formal Statement of Task, included here, refers to “social needs care;” however, as noted in Table 1-2, the committee decided to use “social care.”

-

prevention and functional status, care management, and transitional care; improving end-of-life care; integration of behavioral, mental, and physical health services).

- Initiatives to improve population health and reform health care financing that incorporate social needs care (i.e., payments tied to quality metrics and alternative payment models, such as accountable care organizations, bundled payments, managed long-term services and supports, and accountable health communities).

- Realized and potential contributions of social needs care to make health care delivery systems more community based, patient- and family/caregiver-centered, and responsive to social and structural determinants of health, particularly for vulnerable populations and communities, such as older adults and low-income families.

- Opportunities for advancing the integration of social needs care services within community and health care delivery settings, such as expanding and improving interprofessional education; educating health care providers, payers, and patients about the benefits of social needs care services; and ensuring adequate reimbursement for said education by public and private payers.

- Kinds of transdisciplinary research needed to understand the complex interplay of psychosocial and environmental factors on health, and to best inform efforts to develop policies and practices that lead to improved health outcomes.

The committee makes recommendations on how to (1) expand social needs care services; (2) better coordinate roles for social needs care providers in interprofessional care teams across the range of clinical and community health settings; and (3) optimize the effectiveness of social services to improve health and health care. Recommendations address areas such as the integration of services, training and oversight, workforce recruitment and retention, quality improvement, research and dissemination, and governmental and institutional policy for health care delivery and financing.

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH TO ITS CHARGE

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) appointed a committee of 18 subject-matter experts to carry out this task. The committee members have expertise in social work, nursing, gerontology, public health, clinical medicine, health law and policy, health services research, health care workforce, health care

financing, and health insurance design.3 The committee held four in-person meetings and two Web meetings over the course of the 18-month study to gather evidence, review and deliberate on the evidence, and develop conclusions and recommendations. To address this broad task, it was necessary to take into consideration several types of evidence, including peer-reviewed literature, reports from governmental agencies and private organizations (such as The Commonwealth Fund, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the Milbank Memorial Fund, the National Academies, the National Academy of Medicine, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, among others), books, websites, and invited presentations to the committee during public sessions. Although the committee cast a wide net to identify relevant sources of information, it did not conduct a systematic literature review.

The purpose of the evidence review was to gain an understanding of opportunities for and barriers to integrating social care and health care and to identify both evidence-based and emerging approaches to such integration. Several literature searches were conducted. First, a broad search was conducted using key words related to the overarching topic areas of social work, social services, social welfare, the SDOH, care settings, models of care, integrated care, financing of care, workforce, quality assessment, and vulnerable populations, which were linked in various combinations using Boolean operators. Databases searched included Embase, Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science. The types of literature included peer-reviewed articles, reviews, grey literature reports, and conference proceedings. The websites of organizations conducting work in the area of social care were searched for relevant reports and papers. During the study, several narrowly defined literature searches were conducted to identify additional articles. Further information was gathered by querying committee members, representatives from the study sponsors, and others who work in the field. Studies of integration of health care and social care from nations other than the United States were not included in the review because of fundamental differences in how health care is delivered among nations and the inability to extrapolate findings from other countries to the United States. The committee aimed to identify the best available evidence, ideally evidence that included outcome data. Because integration of health care and social care is an area of active investigation and because assessment of emerging approaches is called out in the study charge, a variety of types of evidence, as noted above, were used as the evidence base to support findings and recommendations presented later in this report.

___________________

3 Biographical information on the committee members can be found on the National Academies’ website: https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/projectview.aspx?key=49935 (accessed May 15, 2019).

In conducting the study, the committee held three public sessions to obtain information and perspectives not readily available in the literature. The first public session was held on July 16, 2018, in Washington, DC, and provided an opportunity for the study sponsors and the committee members to discuss the Statement of Task, how the study supports the sponsoring organizations’ missions, and, more broadly, why the study is important to carry out at this time. The second public session was held on September 24, 2018, in Washington, DC. The committee invited representatives from eight organizations to give presentations. Topics included the experiences of providing social care by several social service and health care organizations, support programs for family caregivers, and select federal government programs in support of providing social care. The third public session was held on November 13, 2018, via Web conference. During this public session, presentations focused on several social work–based models of care.

In addition to the public sessions noted above, the committee met five times in closed session to deliberate on the evidence and to develop findings and recommendations. Chapters 2–6 of this report summarize the evidence and present the committee’s findings. Chapter 7 contains the committee’s recommendations.

BACKGROUND

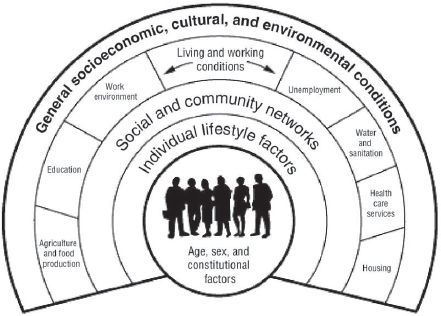

Inherent in the phrase “social determinants of health” is the implication that health is shaped by more than medical care. Defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age” (WHO, 2010), the SDOH have been conceptualized in terms of a socioecological model in which the person is at the center of micro, meso, and macro spheres of external influence (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991) (see Figure 1-2).4 These radiating spheres reflect the second part of WHO’s definition of the SDOH as being “shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels” (WHO, 2010).

Importantly, the SDOH are often misinterpreted as being negative or meant to apply only to a select group of people. All people experience social factors that influence their health. Some of these factors contribute favorably to health outcomes and others negatively. Healthy People 2020 categorizes these interrelated determinants in five groups (see Table 1-1).5

___________________

4 For more information related to the social determinants of health and conceptual socioecologic models, see Andersen, 1995; Bradley and Corwyn, 2002; and Taormina and Gao, 2013.

5Chapter 2 includes a discussion on screening for social determinants of health and the Appendix contains a list of screening tools for social determinants of health.

SOURCE: Reprinted from Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. (1991). Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Futures Studies.

TABLE 1-1

Five Key Areas of Social Determinants of Health

| Social Determinant of Health | Examples of Underlying Factors |

|---|---|

| Economic stability | Employment Food insecurity Housing instability Poverty |

| Education | Early childhood education and development Enrollment in higher education High school graduation Language and literacy |

| Social and community context | Civic participation Discrimination Incarceration Social cohesion |

| Health and health care | Access to health care Access to primary care Health literacy |

| Neighborhood and built environment | Access to foods that support healthy eating patterns Crime and violence Environmental conditions Quality of housing |

SOURCE: HHS, 2019.

At their best, these SDOH can be protective of good health and wellness. For many people, however, the SDOH include a pattern of social risk factors that contribute to increased morbidity and mortality. The specific factors in each of the five categories that influence health in one way or another—and the ways in which the various factors interact—have been reviewed in multiple prior publications. Together these have contributed to an in-depth understanding of what causes and perpetuates vulnerability as well as of how these risks vary across the life course (e.g., see AARP Foundation, 2012; Acton and Malathum, 2000; Adler and Rehkopf, 2008; Bastos and Machado, 2013; Berkman et al., 2011; Blazer et al., 2007; Bor et al., 2017; Center for Surveillance, 2017; Collins et al., 1998; Council for Disabled Children, 2016; Diez Roux et al., 2001; Dzau et al., 2017b; Eriksson, 2011; Greenstone et al., 2013; Hummer and Hernandez, 2013; Kindig and Stoddart, 2003; Long et al., 2017; NASEM, 2019a,b; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2018; NCEH, 2015; Sachs-Ericsson et al., 2006; Silverman, 2009; South et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2019; Tobin-Tyler and Teitelbaum, 2018; VCU Center on Society and Health, 2014; Williams, 2013; Williams and Collins, 2001).

The consistent and compelling evidence on how social determinants shape health has led to a growing recognition throughout the health care sector that improving health and reducing health disparities is likely to depend—at least in part—on improving social conditions and decreasing social vulnerability. The gradual shift in the health care sector toward value-based payment incentivizes prevention and improved health and health care outcomes for persons and populations rather than service delivery alone. The combined result of these changes has been a growth in opportunities for health care systems to utilize the social and community contexts of patients with the aim of improving health outcomes. Some of these opportunities depend on the capacity of health care systems to link individual patients with government and community social services. Others are more focused on community-level social conditions. But important questions need to be answered about when and how health care systems should be involved in both providing social care and, more broadly, influencing social conditions—and what kinds of infrastructure and technical assistance would be required to facilitate these activities. At both the individual patient level and community level, this work is likely to require more deliberate alignment across sectors through such things as formal business arrangements, data sharing, payment policy and financial arrangements, and, where necessary, enabling legislation and regulation. Table 1-2 defines important terms used throughout the report.

TABLE 1-2

Key Terms Used in This Report

| Health | A state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity; this includes affording everyone the fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. |

| Social care | Activities that address health-related social risk factors and social needs. |

| Social determinants of health | The conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age that affect a wide range of health, functional, and quality of life outcomes and risks. |

| Social needs | A patient-centered concept that incorporates a person’s perception of his or her own health-related needs. |

| Social risk factors | Social determinants that may be associated with negative health outcomes, such as poor housing or unstable social relationships. |

| Social services | Services, such as housing, food, and education, provided by government and private, profit and nonprofit, organizations for the benefit of the community and to promote social well-being. |

SOURCES: Adapted from Alderwick and Gottlieb, 2019; HHS, 2019; WHO, 2010.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

To respond to its charge, the committee examined ways in which health care delivery systems have increased activities to understand and intervene in social conditions as a strategy for improving health. It also examined the structural barriers to these activities. The committee’s report is organized into six chapters beyond this one. Chapter 2 describes five complementary activities—awareness, adjustment, assistance, alignment, and advocacy—that health care systems can adopt to strengthen social care integration. Chapters 3–5 cover three system-level elements necessary to implement and sustain social care. Specifically, Chapter 3 describes the elements of a workforce that has the capability and capacity to improve social care within the five activities and the importance of using a collaborative approach. Chapter 4 describes how data and digital tools can be used to integrate social care and health care. Chapter 5 describes options for financing social care within the scope of health care. Chapter 6 describes challenges to implementing awareness, adjustment, and assistance strategies in health care delivery settings. Chapter 7 presents the committee’s recommendations. The Appendix is a summary table of tools used for social needs screening.

REFERENCES

AARP Foundation, K. Elder, and J. Retrum. 2012. Framework for isolation in adults over 50. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/aarp_foundation/2012_PDFs/AARP-Foundation-Isolation-Framework-Report.pdf (accessed May 24, 2019).

Abbott, L. S., and L. T. Elliott. 2017. Eliminating health disparities through action on the social determinants of health: A systematic review of home visiting in the United States, 2005–2015. Public Health Nursing 34(1):2–30.

Acton, G. J., and P. Malathum. 2000. Basic need status and health-promoting self-care behavior in adults. Western Journal of Nursing Research 22(7):796–811.

Adler, N. E., and D. H. Rehkopf. 2008. U.S. disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health 29:235–252.

Alderwick, H., and L. M. Gottlieb. 2019. Meanings and misunderstandings: A social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. The Milbank Quarterly 97(2):407–419.

Andersen, R. M. 1995. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36(1):1–10.

Bastos, A., and C. Machado. 2009. Child poverty: A multidimensional measurement. International Journal of Social Economics 36(3):237–251.

Berkman, N. D., S. L. Sheridan, K. E. Donague, D. J. Halpern, and K. Crotty. 2011. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine 155(2):97–107.

Blazer, D. G., N. Sachs-Ericsson, and C. F. Hybels. 2007. Perception of unmet basic needs as a predictor of depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Gerontology 62A(2):191–195.

Bor, J., G. H. Cohen, and S. Galear. 2017. Population health in an era of rising income inequality: USA, 1980–2015. The Lancet 389(10077):1475–1490.

Bradley, E. H., H. Sipsma, and L. A. Taylor. 2017. American health care paradox: High spending on health care and poor health. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 110(2):61–65.

Bradley, R. H., and R. F. Corwyn. 2002. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology 53:371–399.

Braveman, P., S. Egerter, and D. R. Williams. 2011. The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health 32:381–398.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2018. Social determinants of health: Know what affects health. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm (accessed May 24, 2019).

Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services. 2017. About rural health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ruralhealth/about.html (accessed May 24, 2019).

Collins, J. W., Jr., R. J. David, R. Symons, A. Handler, S. Wall, and S. Andes. 1998. African-American mothers’ perception of their residential environment, stressful life events, and very low birthweight. Epidemiology 9(3):286–289.

Council for Disabled Children. 2016. Identifying the social care needs of disabled children and young people and those with SEN as part of education, health, and care needs assessments. https://councilfordisabledchildren.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/attachemnt/Identifying%20the%20social%20care%20needs_0.pdf (accessed May 24, 2019).

Dahlgren, G., and M. Whitehead. 1991. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Institute for Futures Studies. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6472456.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

Daly, M. 2014. A social rank explanation of how money influences health. Health Psychology 34(3):222–230.

Diez Roux, A. V., S. S. Merkin, D. Arnett, L. Chambless, M. Massing, F. J. Nieto, P. Sorlie, M. Szklo, H. A. Tyroler, and R. L. Watson. 2001. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. New England Journal of Medicine 345(2):99–106.

Dzau, V. J., M. B. McClellan, J. M. McGinnis, S. P. Burke, M. J. Coye, A. Diaz, T. A. Daschle, W. H. Frist, M. Gaines, M. A. Hamburg, J. E. Henney, S. Kumanyika, M. O. Leavitt, R. M. Parker, L. G. Sandy, L. D. Schaeffer, G. D. Steele, Jr., P. Thompson, and E. Zerhouni. 2017a. Vital directions for health and health care: Priorities from a National Academy of Medicine initiative. JAMA 317(14):1461–1470.

Dzau, V. J., M. McClellan, J. M. McGinnis, and E. M. Finkelman (eds.). 2017b. Vital directions for health & health care: An initiative of the National Academy of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

Eriksson, M. 2011. Social capital and health: Implications for health promotion. Global Health Action 4:5611.

Greenstone, M., A. Looney, J. Patashnick, and M. Yu. 2013. Thirteen economic facts about social mobility and the role of education. The Hamiliton Project, The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/THP_13EconFacts_FINAL.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

Health Research & Educational Trust. 2017. Housing and the role of hospitals. Social Determinants of Health Series, American Hospital Association. https://www.aha.org/ahahret-guides/2017-08-22-social-determinants-health-series-housing-and-role-hospitals (accessed July 12, 2019).

Heiman, H. 2015. Beyond health care: Role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-beyond-health-care (accessed May 26, 2019).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2019. Healthy people 2020: Social determinants of health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (accessed May 8, 2019).

Hummer, R. A., and E. M. Hernandez. 2013. The effect of educational attainment on adult mortality in the United States. Population Bulletin 68(1):1–16.

Kaiser, M. L., and A. Cafer, 2018. Understanding high incidence of severe obesity and very low food security in food pantry clients: Implications for social work. Social Work in Public Health 33(2):125–139.

Kindig, D., and G. Stoddart. 2003. What is population health? American Journal of Public Health 93(3):380–383.

Long, P., M. Abrams, A. Milstein, G. Anderson, K. Lewis Apton, M. Lund Dahlberg, and D. Whicher (eds.). 2017. Effective care for high-need patients: Opportunities for improving outcomes, value, and health. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

McKinlay, J. 1979. A case of refocusing upstream: The political economy of illness. In E. G. Jaco (ed.), Patients, physicians, and illness. A sourcebook in behavioral science and health, 3rd ed. London, UK: The Free Press. Pp. 9–25.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019a. The promise of adolescense: Realizing opportunity for all youth. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2019b. Vibrant and healthy kids: Aligning science, practice, and policy to advance health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2018. The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html (accessed August 12, 2018).

NCEH (National Center for Environmental Health). 2015. CDC’s built environment and health initiative. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/information/built_environment.htm. Last Modified: December 8, 2015 (accessed May 24, 2019).

NHS (National Health Service) England. n.d. Integrated care systems. https://www.england.nhs.uk/integratedcare/integrated-care-systems (accessed July 12, 2019).

NRC and IOM (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine). 2013. U.S. health in international perspective: Shorter lives, poorer health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Papanicolas, I., L. R. Woskie, and A. K. Jha. 2018. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 319(10):1024–1039.

Sachs-Ericsson, N., C. Schatschneider, and D. G. Blazer. 2006. Perception of unmet basic needs as a predictor of physical functioning among community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Aging and Health 18(6):852–868.

Silverman, M. 2009. Issues in access to healthcare by transgender individuals. Women’s Rights Law Reporter 30(2):347–351.

South, E. C., B. C. Hohl, M. C. Kondo, J. M. MacDonald, and C. C. Branas. 2018. Effect of greening vacant land on mental health of community-dwelling adults: A cluster randomized trial. JAMA Network Open 1(3):e180298.

Squires, D., and C. Anderson. 2015. U.S. health care from a global perspective: Spending, use of services, prices, and health in 13 countries. Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) 15:1–15.

Taormina, R. J., and J. H. Gao. 2013. Maslow and the motivation hierarchy: Measuring satisfaction of the needs. American Journal of Psychology 126(2):155–177.

Thompson, T., A. McQueen, M. Croston, A. Luke, N. Caito, K. Quinn, J. Funaro, and M. W. Kreuter. 2019. Social needs and health-related outcomes among Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Education and Behavior 46(3):436–444.

Tobin-Tyler, E., and J. Teitelbaum. 2018. Essentials of health justice: A primer. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

VCU (Virginia Commonwealth University) Center on Society and Health. 2014. Why education matters to health: Exploring the causes. https://societyhealth.vcu.edu/media/society-health/pdf/test-folder/CSH-EHI-Issue-Brief-2.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010. About social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en (accessed May 24, 2019).

Williams, D. R., and C. Collins. 2001. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports 116(5):404–416.

Williams, D. R., M. C. Costa, A. O. Odunlami, and S. A. Mohammed. 2008. Moving upstream: How interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice 14:S8–S17.

Williams, J. 2013. Social care and older prisoners. Journal of Social Work 13(5):471–491.

This page intentionally left blank.