3

A Workforce to Integrate Social Care into Health Care Delivery

Workforce availability and the competence of workers to serve the needs of complex vulnerable populations and address adverse social determinants of health (SDOH) is not a new subject for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). Among the National Academies reports that have addressed this topic are Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce (IOM, 2008), The Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce for Older Adults: In Whose Hands? (IOM, 2012), Measuring the Impact of Interprofessional Education on Collaborative Practice and Patient Outcomes (IOM, 2015), A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health (NASEM, 2016a), Strengthening the Workforce to Support Community Living and Participation for Older Adults and Individuals with Disabilities (NASEM, 2017), and Effective Care for High-Need Patients: Opportunities for Improving Outcomes, Value, and Health (Long et al., 2017). In addition, reports produced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, such as Addressing the Social Determinants of Health: The Role of Health Professions Education (Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry, 2016), shed light on the critical issues of the role of the workforce in addressing social determinants and provide recommendations for improvement. Collectively, these reports establish the foundation required to discuss how to best prepare and support a workforce to address the social needs of populations as one component of health care delivery.

Evidence linking the SDOH with a population’s health status and health care costs has led to efforts to redesign health care and to better

link the provision of health care with the provision of social services in ways that address the factors that contribute to the poor health of patients and communities. Chapter 2 identified five complementary activities that health care systems can adopt in order to strengthen social care integration: awareness, adjustment, assistance, alignment, and advocacy. Implementing and sustaining efforts within each of the five activities will require making systems-level changes, including the development of a well-trained workforce with defined roles, innovations in data and digital tools, and new financing models. This chapter focuses on the necessary elements of a workforce that will have the capability and capacity to improve social care within these five activities.

THE PROMISE OF INTERPROFESSIONAL TEAMS IN IMPROVING SOCIAL CARE

There is a consensus among agencies and organizations as well as among educators and clinicians that addressing the adverse SDOH is complex and requires an interprofessional team (NASEM, 2016b). Teamwork in health care has been associated with improvements in knowledge, practice, and such outcomes as quality, cost reduction, and job satisfaction (Medves et al., 2010). Effective collaboration among teams requires explicitly defined tasks and goals, clear and meaningful roles for each individual, and systematic guidelines to assist practitioner in their decision making. The use of in-person and technology-based mechanisms to minimize gaps in care and to avoid duplication of services is important since many team members may be working remotely from one another. The processes that are important in optimizing the functioning of a team include collaboration and coordination, the pooling of resources, and role blurring, which is defined as creating a shared body of knowledge and skills among team members so that various elements of professionals’ roles can be taken on by others, if necessary (Sims et al., 2015).

Tackling the complex social needs of patients and families requires collaboration, both on the team and outside of the traditional health care sector, such as on the staffs of social service and public health agencies and community-based organizations.1 As such, the list of individuals who may be considered team members has been expanding. For example, lawyers have become critical team members for addressing legal matters related to housing and other social factors among patients in community

___________________

1 As detailed below, types of workers who provide social care can include nurses; physicians; social workers; community health workers; social service navigators, aides, assistants, and trained volunteers; home health aides; personal care aides; family caregivers; case managers; gerontologists; lawyers; and others.

health centers (Regenstein et al., 2018). As more organizations and payers address social needs, competencies should be established to ensure that interprofessional teams are equipped to work together optimally within the complex and shifting landscape of social care. The competencies established for behavioral and primary care workers are an example of how competencies can be used for interprofessional teams (Hoge et al., 2014).

How effectively interprofessional teams are able to carry out their day-to-day work is dependent on several factors that, if not taken into account, can hamper integration and collaboration among team members. One such important factor is role clarity—that is, how well team members know their own and the other’s roles and responsibilities (Ambrose-Miller and Ashcroft, 2016; Sims et al., 2015). Social needs are best addressed when members of the interprofessional team understand the role that each team member plays, both directly and indirectly, in the awareness, adjustment, assistance, alignment, and advocacy activities described in Chapter 2. Team members should understand the knowledge, skills, and competencies that each member brings, and each member should be able to work at the full scope of his or her knowledge, skills, and competencies (Glaser and Suter, 2016; Lombardi et al., 2017; Sims et al., 2015). Other factors aiding in the effective functioning of interprofessional teams include allowing team members to maintain their professional identities, particularly in the case of social care workers who work within health care (Garfield and Kangovi, 2019), and addressing issues related to power dynamics among team members (Ambrose-Miller and Ashcroft, 2016). Attributes of successful interprofessional teams include a commitment by staff members to work in a team environment, communication among the staff, and the ability of staff members to come up with creative ways to conduct their work (Molyneux, 2001). According to Sims and colleagues

Teams are complex entities influenced by human and organizations factors and the field of health they operate in. This makes teamworking highly variable and context dependent, which means that different teams will succeed in different situations depending upon the processes, participants, and context in which they are based. (Sims et al., 2015, p. 20)

Interprofessional education—defined as “when students from two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes” (WHO, 2010a, p. 7)—is an important approach to developing effective interprofessional teams that can address the integration of social care into health care. Recommendations from both the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality report and the Interprofessional Education Collaborative have called for curriculum and learning activities designed

to develop competencies among health care and social service professionals in the delivery of patient-centered team care (IOM, 2003a; IPEC, 2011).

More educational institutions are developing and providing core curricula to health care and social service providers. Some professions have embraced the need for interprofessional team collaboration to assure that their workers are equipped with the skills, knowledge, and abilities necessary to provide effective team care and to address the social needs of patient populations. The most effective interprofessional education programs combine coursework with clinical and service learning experiences in the community (Greer et al., 2018; Siegel et al., 2018; Zomorodi et al., 2018). For example, physicians accompanying a social worker on home visits typically come away with a new appreciation for how the social needs that were identified could compromise the care plan they had in mind (Fulmer et al., 2004).

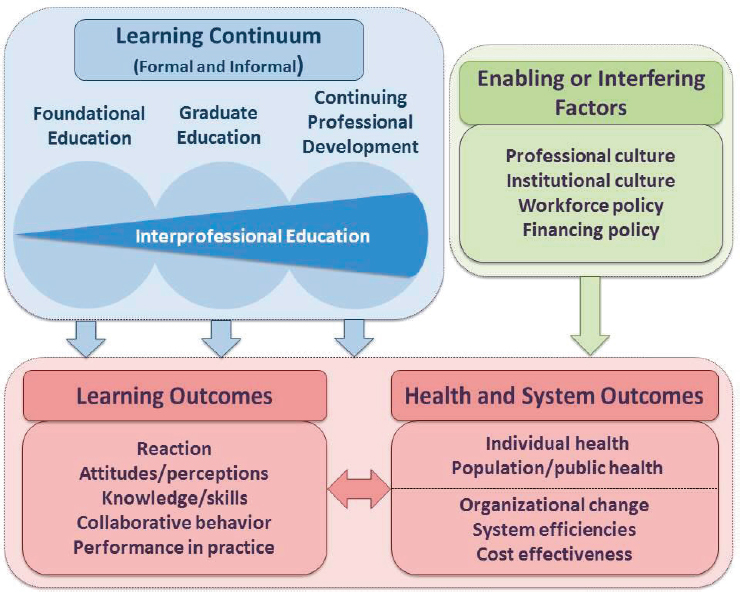

The pathway from initial education to practice behaviors is complex (IOM, 2015) (see Figure 3-1). In considering how best to develop a health

NOTE: For this model, “graduate education” encompasses any advanced formal or supervised health professions training taking place between the completion of foundational education and entry into unsupervised practice.

SOURCE: IOM, 2015.

care workforce that understands and can take into account social factors, it is important to recognize that a health worker’s ability to address social needs can be affected by various external factors. Among the factors that can influence the training of health care workers and their delivery of care are the professional and institutional cultures in which they train and work as well as various workforce and financial policies. The conceptual model shown in Figure 3-1, which assumes interprofessional education to be the gold standard for health and social service training, includes the education-to-practice continuum and a broad array of learning, health, and system outcomes, and it shows the major enabling and interfering factors that affect the education-to-practice pathway. This model was put forth with the understanding that it requires empirical testing and that it may have to be adapted to the particular settings in which it is applied.

The development and implementation of effective interprofessional team training programs face a number of challenges. For example, a national evaluation of The John A. Hartford Foundation’s Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team Training program found that the attitudinal and cultural traditions of the different health professions faculty and students (usually split along disciplinary lines) are important obstacles to creating an optimal interdisciplinary team training experience (Reuben et al., 2004). In general, physician trainees participated least enthusiastically in geriatric interdisciplinary team training. Among the other challenges to establishing effective interprofessional team training programs are various logistical issues, such as dealing with differences in educational calendars among the different professions and class schedules. At the heart of the challenge in installing team-based approaches as a key part of professional education is what Frenk and colleagues referred to as “tribalism of the professions—that is, the tendency for the various professions to act in isolation from or even in competition with each other” (Frenk et al., 2010, p. 1923).

THE TRADITIONAL HEALTH CARE WORKFORCE

As noted above, effectively addressing people’s complex social needs requires that workers within the traditional health care system collaborate with workers from outside of it, such as the staff of social service and public health agencies and community-based organizations. This team approach is not one size fits all. The composition of teams can vary depending on such factors as the available resources (e.g., human, technological, and financial resources), the circumstances (e.g., urban versus rural location), and importantly, which of the five activities (awareness, adjustment, assistance, alignment, and advocacy) is being addressed. An awareness of the SDOH and social care is essential. Just as established

competencies and training measures ensure that professionals within the social care landscape can work together and communicate effectively, it is crucial that traditional health care workers know about social care. Health professional organizations are increasingly interested in adding curricular content on addressing the SDOH to health professional education (HRSA, 2016). The competencies related to the SDOH include cultural humility, reflection, advocacy, cultural competency, partnership skills, patient communication, and empathy.

The nursing profession has long focused on the social needs of people and communities (Buhler-Wilkerson, 1993; Fee and Garofalo, 2010). Acute care nurses are expected to also address the psychosocial needs of patients, whether through referrals to social workers or care managers or as part of the discharge planning process. Some nurses are care managers and have great involvement in addressing social needs within health care delivery. Home care nurses assess patients’ and families’ social needs and may refer patients who have complex social needs to social workers. Nurses in home visitation programs for high-risk mothers and children, such as the Nurse-Family Partnership, address social supports, employment, education, and various other aspects of the mothers’ lives such as how to reduce contact with the criminal justice system. These activities are important to short- and long-term maternal and child outcomes (Olds et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2008). Other examples of nurse-designed models of care that successfully integrate the social needs of individuals and families have been documented in a 2018 RAND report (Martsolf et al., 2017).

In its 2008 report The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) defined the essentials of a baccalaureate education in nursing, noting that programs are expected to educate graduates who can “apply knowledge of social and cultural factors to the care of diverse populations” (AACN, 2008, p. 12) and “facilitate patient-centered transitions of care, including discharge planning and ensuring the caregiver’s knowledge of care requirements to promote safe care” (AACN, 2008, p. 31). The AACN commissioned a “visioning” task force for defining the future of nursing education. The resulting vision includes educating nurses about the SDOH, and this is expected to be included in the next version of The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice.2 The National League for Nursing intends to undertake similar work to include the SDOH and social care in its recommendations for nursing curricula.3

___________________

2 Personal communication, Deborah Trautman, American Association of Colleges of Nursing, October 17, 2018.

3 Personal communication, Beverly Malone, National League for Nursing, October 1, 2018.

Physicians, particularly those working in primary care (including internal medicine, pediatrics, geriatrics, and family medicine) are increasingly expected to recognize the role of social risk factors and social needs in the prevention and treatment of illness and disability. No systematic studies have been done, however, to determine the prevalence of physicians’ awareness of or engagement in social care integration or what types of physicians may use which types of activities more frequently.

For those physicians who have completed medical school and are in postgraduate training, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has identified several competencies that support physician involvement in addressing patients’ social needs. Some of the competencies are related to awareness activities, such as being able to communicate effectively with patients, families, and the public, as appropriate, across a broad range of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. Others of the competencies are related to assistance activities, such as the ability to work in interprofessional teams to enhance patient safety and improve patient care quality; having sensitivity and responsiveness to a diverse patient population, including patients diverse in gender, age, culture, race, religion, disabilities, and sexual orientation; and being able to work effectively as members or leaders of a health care team or other professional group (ACGME/ABFM, 2015; Cate, 2013; Leipzig et al., 2014; Parks et al., 2014).

When physician residency programs do include content on the SDOH, it is largely didactic and provided in short or one-time sessions (Gard et al., 2018). Some residency programs include more extensive content on the SDOH; for example, Florida International University’s Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine has a service-learning experience in the community with an interprofessional team of students (including nursing and public health) that integrates the SDOH, professional teamwork competencies (including nursing and public health), and community collaboration (Greer et al., 2018). There is a growing recognition of the need to include formal education about the SDOH as part of physician training, and some medical schools are calling for a dramatic rethinking of the social mission of medical schools more broadly, including their responsibility to focus educational, research, clinical, and community service efforts on the SDOH, particularly for the communities where they are located (Mullan, 2017). A review of the literature found rising interest in making the SDOH as part of medical education (Doobay-Persaud et al., 2019). Medical education leaders and experts also are supportive of increasing the exposure to the SDOH across the medical education curriculum; doing this, however, will require development of a common curriculum, standardizing teaching methods, and standard approaches to evaluating impact (Mangold et al., 2019).

SOCIAL CARE WORKFORCE

Ideally, all members of an interprofessional team should have a baseline understanding of social care and the SDOH, but that likely will not be sufficient; effectively integrating social care into health care beyond the level of awareness may require developing a workforce with expertise and a scope of work that are specific to social care. The following discussion provides information that should be considered when developing interprofessional teams, including details about the necessary skill sets and the key professions involved with providing social care. Depending on the social needs of a particular population, it may make sense to include other professions on the team beyond those discussed below (e.g., clergy, medical interpreters, or oral health providers). The composition of interprofessional teams will vary depending on the model of care.

Social Workers

There is a long history of professional social workers providing social care within both the health care and social service sectors, and many social workers have expertise in these fields (Gehlert and Browne, 2011). Social workers assess and address the social needs and well-being of people’s lives, whether through direct interventions at the micro level (awareness and assistance activities aimed at the individual and family) or through activities at the meso level (adjustment and alignment activities within the health care system) and macro level (alignment and advocacy at the socio-structural level) (Newman et al., 2015; USC, 2019).

Social workers have led efforts to build bridges between the silos of social services and health care through interventions such as care management and transitional care that take advantage of social work expertise in patient and family engagement, assessment, care planning, behavioral health, and systems navigation (Fraser et al., 2018). By speaking the “language” of—and understanding the important roles of—both community and medical providers, social workers can play an important role in ensuring effective collaboration and communication across the care continuum. They also lead community-based organizations that focus on the social needs and well-being of individuals and families in communities (Pecukonis et al., 2013). Medical social workers are directly involved with the health of individuals and work in a variety of settings, typically hospitals, outpatient clinics, community health agencies, social service agencies, skilled nursing facilities, long-term care facilities, hospices, and health insurers’ offices.

Professional social workers obtain a baccalaureate or master’s degree in social work, and both bachelor’s- and master’s-level social workers

can seek licensure. Master’s-degreed social workers can also seek licensure as a clinical social worker as a specialty within the master degree.4 Licensure requirements vary by state, but typically involve an exam and a minimum amount of clinical hours with supervision by a licensed clinical social worker. Social workers’ education and training cover many of the SDOH competencies noted above. For example, the social work profession, through the National Association of Social Workers, has developed a number of specialized standards of practice that focus on the needs for clinical services of special populations or within specific care settings (NASW, 2016). Several of these standards are particularly relevant to social care in health care delivery. One notable standard for clinical social work in social work practice is: “Clinical social workers shall be knowledgeable about community services and make appropriate referrals, as needed” (NASW, 2005, p. 4). A comprehensive set of standards exists for social work practice done within health care settings, including, for example,

Social workers practicing in health care settings shall advocate for the needs and interests of clients and client support systems and promote system-level change to improve outcomes, access to care, and delivery of services, particularly for marginalized, medically complex, or disadvantaged populations. (NASW, 2016, p. 29)

In the area of practice in interprofessional teams, the standards for social workers in health care settings include, for instance, “Social workers practicing in health care settings shall promote collaboration among health care team members, other colleagues, and organizations to support, enhance, and deliver effective services to clients and client support systems” (NASW, 2016, p. 31).

Community Health Workers

Community health workers (CHWs) provide linkages among health, social services, and the community (APHA, 2019). Often recruited from the communities they serve, CHWs work in health systems, social service agencies, and community-based organizations. There is a growing number of CHWs employed in hospitals and health systems as well (Malcarney et al., 2017). They are engaged in awareness, assistance, and advocacy activities. All but three states have efforts related to integrating CHWs into health care systems (NASHP, 2017).

There is growing evidence of their positive impact on health, particularly for low-income and minority patients. Several outcome studies

___________________

4 This text has been revised since prepublication release.

related to the use of CHWs have been conducted. The Penn Center for Community Health Workers developed and tested the IMPaCT model, a standardized and scalable CHW intervention; two clinical trials have documented the positive effect of the model (Kangovi et al., 2017, 2018). A systematic review of the literature concluded that there is some evidence that the use of CHWs to help care for the chronically ill could reduce the use of health care and costs (Jack et al., 2017). It is important to note, however, that these studies of the role of CHWs in bridging medical and social care did not clearly articulate whether the CHWs’ social care was the component of the intervention that actually achieved health outcomes.

Efforts are under way to develop competencies and standardize educational requirements for CHWs (Rosenthal et al., 2016). The North Carolina Community Health Worker Initiative provides technical assistance from CHW experts through the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials with the aims of confirming the roles and competencies of CHWs, standardizing their training and certification, and identifying the infrastructure and policy supports necessary for the effective use of CHWs (NC DHHS, 2019). The global need for such standardization of the CHW role, training, and infrastructure development has been recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2010b).

According to a 2003 IOM report, barriers to the integration of CHWs into health care delivery include inconsistencies in the scope of practice, training, and qualifications; a lack of sustainable funding; and insufficient recognition by other health professionals (IOM, 2003b). Certification has been established in a number of states, but the requirements (both education- and career-wise) vary widely. Training requirements range from 80 hours to 160 hours, with various provisions for “grandfathering” experienced CHWs (CDC, 2016). The lack of universal professional standards has been described as part of the rationale for the establishment of the National Association of Community Health Workers, which launched in April 2019 (NACHW, 2019).

Social Service Navigators, Aides, and Assistants

Social service navigators, aides, and assistants, and also trained volunteers often work outside of the health care sector in awareness, assistance, and advocacy roles in social service agencies and community-based organizations. Examples include housing and transportation experts, people who work at food banks, people who provide employment assistance, outreach and enrollment workers, navigators, and trained volunteers. These workers assist patients and families on a wide range of activities and often help them find and access services in the community. There is currently no national certification or credentialing for social service

navigators, aides, and assistants, or for trained volunteers. Requirements for these workers vary by state, but the workers typically must have at least a high school diploma and must complete a brief period of on-the-job training.

Home Health Aides and Personal Care Aides

Within the health care sector, home health aides and personal care aides provide extensive social support services to assist older adults and disabled and post-acute care patients in their homes. These direct care workers have close contact with the country’s most disadvantaged patients. Working in the home, they can directly observe a wide variety of their clients’ social needs and then provide this information to other members of the care team. They have an important role to play in the assistance activity in providing social care.

Family Caregivers

People who provide care for their family members (family caregivers) are another critical part of the care team and provide assistance to many individuals. Because they spend time in the home, family caregivers, similar to home health aides and personal care aides, have a valuable perspective on the social needs of patients. In 2015 more than 43 million Americans provided unpaid care to high-need individuals, with an estimated 85 percent of them being family members (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2016). These caregivers provide a wide range of services, including complex medical–nursing tasks such as managing multiple medications, providing wound care, and using medical-related monitors; assisting with activities of daily living; transportation; and communicating with and visiting with health care providers (Reinhard et al., 2012).

Case Managers

Case managers (and care managers) work intensively with individuals with complex social needs, whether in the health care system or with social service agencies. An increasing number are certified, as health care organizations and other employers increasingly require certification for hiring or continuing employment (Tahan et al., 2006). Case managers focus on coordinating the health and social care of patients and work within the spheres of awareness, assistance, and advocacy (at the individual level). They can be based in hospitals, at home care agencies, in skilled nursing and rehabilitation facilities, or with community-based organizations. Case managers also are found in social services agencies, such as

foster care agencies, child welfare agencies, senior centers, and homeless shelters. Often, the role of case managers is filled by licensed clinical social workers and licensed nurses.

Promising Additional Professions for Improving Social Care

Gerontologists

Gerontology is a discipline that holds promise for addressing the social needs of the older adult population. According to the Academy for Gerontology in Higher Education (AGHE), “gerontologists improve the quality of life and promote the well-being of persons as they age within their families, communities, and societies through research, education, and application of interdisciplinary knowledge of the aging process and aging populations” (AGHE, 2019). Functional health and independence are the goals of care for older adults, and therefore addressing social needs is a component of addressing health care needs. AGHE has identified core and contextual competencies that support the roles of gerontologists in the five categories of activities that promote social care as part of health care delivery (AGHE, 2014).

Gerontology is not well defined in terms of how it relates to social care. Unlike other types of health and social services disciplines, there is no licensure, scope of work, or U.S. Department of Labor recognition for gerontologists. In 2016 the Accreditation for Gerontology Education Council was established to accredit gerontology education programs at the associate, baccalaureate, and master’s levels. This is an important step in the development of the profession and will further link the AGHE competencies to gerontology education programs and social care practice. According to the National Association for Professional Gerontologists, certified gerontologists report holding such positions as direct service providers (health and community support services), administrators, chief executive officers, entrepreneurs and business owners, therapists and counselors, resource navigators and information specialists, program directors, professors, researchers, pastors, and geriatricians and other medical doctors.5 In certain states, organizations employing gerontologists with at least a bachelor’s degree can be reimbursed for services specified in the waiver agreement with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Home and Community-Based Services Program (California Department of Health Care Services, 2019). These services vary by state, but often include a home- and community-based services wellness assessment and case management services. Because older adults often have

___________________

5 Personal communication, Donna Schaefer, August 29, 2018.

complex medical and social needs, expanding the use of gerontologists in these roles will provide an additional resource for increasing social care.

Lawyers

Lawyers who address the social needs of patients and families are increasingly being used in community-based organizations, including some federally qualified health centers, to assist patients and families with legal matters that can compromise health, such as inadequate housing or a loss of housing. Medical–legal partnerships integrate the unique expertise of lawyers into health care settings in order to help clinicians, social workers, and care managers address the social needs of patients in ways that can reduce many health inequities (Regenstein et al., 2018). There are many different types of lawyers, but one type in particular is relevant to social care: the public interest lawyer.

Public interest lawyers work for private, nonprofit organizations that provide legal services to disadvantaged people or others who otherwise might not be able to afford legal representation. They generally handle civil cases, such as those having to do with leases, job discrimination, and wage disputes, rather than criminal cases. (BLS, 2019)

Increasing the availability and involvement of public interest lawyers will help in providing social care to the vulnerable populations.

CHALLENGES AND BARRIERS FOR SOCIAL CARE WORKERS

The social care workforce faces a number of challenges and barriers to practice at the individual level, organizational level, and systems level. More information on the workforce challenges related to integrating social care into the delivery of health care is presented in Chapter 6.

Individual worker-level challenges can be divided into several categories: worker health and well-being, including issues related to burnout, violence, and suicide; worker satisfaction, including issues related to compensation, incentives, perceived value, and sense of identity; and negative attitudes regarding the SDOH and “blaming the victim” (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014; Bride, 2007; Eelen et al., 2014; Hart and Warren, 2013; Kim et al., 2018; Martin and Schinke, 1998). These individual-level challenges can be worsened by a lack of organizational capacity to address adverse social conditions, which can exacerbate professional burnout, particularly by affecting providers’ self-efficacy (De Marchis et al., 2019; Olayiwola et al., 2018; Pantell et al., 2019).

Organizational-level challenges include issues relating to the hierarchy of leadership of health and social service professionals and the siloed nature of health care and social services (Ellner and Phillips, 2017), role limitations in care settings (La Motte, 2012), issues relating to work and case load assignments, and the orientations and values of educational institutions (NASEM, 2016a).

Systems-level challenges include barriers to reimbursement for certain types of workers (Houston and Mahadevan, 2015; HRSA, 2018a), inadequate numbers of workers, and workforces that are not demographically representative of the populations they serve (Lin et al., 2016; NASEM, 2016a; Warshaw and Bragg, 2014).

Medicare payments and policy have substantially influenced medical and clinical social work. In 1989 the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act amended the Social Security Act to include clinical social work services under Medicare Part B covered services, defining clinical social work services as services related to the “diagnosis and treatment of mental illnesses” (summarized in Zarrella, 2005). This change enabled licensed social workers to bill Medicare for individual and group psychotherapy, which contributed to social work becoming the largest behavioral health workforce in the United States (Heisler, 2018; Zarrella, 2005). However, this definition of clinical social work is limiting in that it does not reflect the broad array of services that clinical social workers provide, which creates confusion about social work’s scope of practice despite curricula and core competencies that reach beyond behavioral health diagnosis and treatment. As a result, no matter whether they practice independently, as part of a health care organization, or as part of a community-based organization, social workers are defined in Medicare only as mental health providers and not as carrying out other roles such as care managers or the providers of psychoeducation that help patients adapt to a new diagnosis. This means that no matter the practice setting, social workers’ work is not adequately captured by Medicare fee-for-service billing options. Importantly, the definition’s exclusive focus on behavioral health has largely prevented social workers from using health and behavior assessment and intervention codes for billing, even though it is these codes that reimburse for services that target social factors resulting from or affecting physical health problems and that are unrelated to a behavioral health diagnosis (NASW, 2016). This billing limitation restricts the ability of health care and community-based organizations to build and sustain interventions that integrate health care and social care to address social needs. Thus, the limitation of social workers’ ability to bill for non-mental–health services in a clinical setting by default limits their scope of practice because other sustainable sources of funding for their services often are not available.

One note of caution is warranted here. Laws and regulations governing a profession’s scope are generated in political environments and steeped in historical contexts. As such, the current policies governing the scope of practice for health professionals may not reflect the emerging interest in integrating social care into health care delivery, in the effective use of interprofessional teams, and in having all health care workers practicing to the top of their education and training (IOM, 2011). This issue of practicing to the top of one’s scope of practice applies to social care workers as well as to traditional health care workers. And emerging workforce professions such as CHWs often have only exclusionary guidance on their scope—there are few states that have statutes or regulations defining their scope of practice, so in most states their work is defined by what other professions claim as exclusive territory (CDC, 2016).

Individual- and organizational-level challenges and barriers affect recruitment and retention efforts and contribute to workforce shortages. For example, in addition to the general reimbursement and scope-of-practice challenges experienced by social workers, individual states differ in their qualifications for licensure, categories of licensure, and scopes of practice. There is no system of license reciprocity or portability among states, making both professional relocation and the provision of telehealth services difficult.

In addition to educating the future health care workforce and training the current workforce about health disparities and the importance of addressing social needs in health care delivery, it is important to make sure that the health care workforce is representative of the demographics of the communities it serves. Substantial variation exists in how well health care and social service occupations reflect the diversity of the U.S. population, with minorities being underrepresented in professions requiring master’s level education or higher (HHS, 2017). Employing more underrepresented minority groups in health care may improve how well social care is provided and may better meet the needs of an increasingly diverse U.S. population. Several governmental and nongovernmental bodies have concluded that ensuring that the nation has a diverse health care workforce—especially in terms of gender, cultural, and linguistic representation—is essential (Council on Graduate Medical Education, 2016; HHS, 2006; Wakefield, 2014).

Healthy People 2020 sets goals that include eliminating health disparities, addressing the SDOH, and improving access to high-quality health care (HHS, 2010). Achieving these goals will require the use of culturally informed approaches and the hiring of diverse health care and social services professionals and research investigators who possess the appropriate knowledge and skills. Additional leadership and professional development programs for faculty and students from underrepresented

minority groups may help to meet these goals and rectify the underrepresentation of certain demographic groups in the health care workforce. There also is funding for health professions education for minority-serving institutions and underrepresented minorities, including a multitude of programs sponsored by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Bureau of Health Workforce (HRSA, 2018b).

EXAMPLES OF INTERPROFESSIONAL TEAMS THAT ARE ADDRESSING THE FIVE HEALTH CARE SECTOR ACTIVITIES

A range of knowledge, skills, and competencies are necessary to address the five health care sector activities—awareness, adjustment, assistance, alignment, and advocacy. Individual activities require interprofessional approaches, but, more to the point, the range of the activities requires an interprofessional workforce. Highlighted below are several examples of how interprofessional teams around the country are providing social care as a part of health care delivery.

- Hennepin Health in Minnesota is a health care delivery program formed by joint efforts from the Minnesota Department of Human Services, Hennepin County, and the Northpoint Health & Wellness Center.6 This program seeks to support care delivery reform that can bolster clinical outcomes for patients, both in terms of patient satisfaction and cost. Through multidisciplinary teams, Hennepin Health establishes relationships with patients so its clinicians can best assess the patients’ health risk factors and social needs, allowing them to provide the best care coordination possible. The multidisciplinary teams include both clinical and social care workers to ensure that all lifestyle areas that affect health can be covered. These areas include transportation, nutrition, social support, legal, finances, work, and medications.

- Care Neighborhood is a program in Northern California in which CHWs reach out to those most at risk to address their social, medical, and behavioral health care needs in order to reduce costs and decrease the use of hospitals and emergency departments (EDs).7 Care is delivered by one to two CHWs, who are staff members based at each health center organization and integrated into the medical home team (senior leader champion, social worker, and

___________________

6 For more information, see http://www.healthreform.ct.gov/ohri/lib/ohri/1._hennepincounty-medical-center.pdf (accessed on July 15, 2019).

7 For more information, see https://www.careinnovations.org/resources/signature-project-care-neighborhood (accessed on July 15, 2019).

-

nurse). These interdisciplinary teams support the CHWs, whose focus is on member relationship and connection to community resources. The program has been implemented at 8 health center organizations with 12 CHW positions within the Care Neighborhood Network. Once members have been identified by the embedded care team, a clinic-based CHW, with support from a nurse and social worker, assesses and determines next steps. These next steps can include connecting to basic benefits and community resources, connecting to clinic resources and primary care visits, full case management support (navigation, home visits, and care coordination), and integrated behavioral health or housing support services.

- The Bridge model of transitional care is an example of a successful practice-based, cross-disciplinary, and cross-sector care model that addresses social needs (Altfeld et al., 2013; Boutwell et al., 2016; Xiang et al., 2018). Following a hospitalization or rehabilitation stay, Bridge social workers engage with the patient, family members, and inpatient and outpatient providers to ensure smooth discharges that are attentive to social needs and that reinforce primary care engagement. Bridge’s protocol applies the social work core competencies of patient engagement, person-in-environment (or systems) theory, resource navigation, and psychotherapeutic techniques. Bridge places significant emphasis on collaboration across the health and social care continuum, sometimes convening all relevant inpatient, primary care, specialty care, community-based, and in-home providers to take part in care continuity calls for particularly complex patients in order to ensure that all the providers understand the patient’s care plan and to troubleshoot any issues that arise. In addition to such hospital-driven programs, staff in community-based organizations across the nation who have been trained in Bridge provide transitional care in partnership with hospitals or skilled nursing facilities. In these hospital–community partnerships, the community-based organization generally also provides other services that are commonly included in patients’ care plans, such as home-delivered meals or chronic disease self-management classes. The goal is to create a more seamless connection between social care and medical care and thereby to improve health and quality-of-life outcomes for patients and families after an inpatient stay. In various implementation sites with a diverse range of populations, the Bridge model has been found to be associated with increased follow-up with primary care providers, fewer ED visits, and fewer hospital readmissions. Despite these successes, various

-

challenges, including workforce barriers, exist to scaling up and sustaining these cross-sector, interdisciplinary partnerships.

- In an effort to better connect patients with social service agencies that were already available in their area, Geisinger Health System, which operates in parts of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, started a 3-year pilot using community health assistants and social workers to improve resource access.8 This program was carried out within 5 counties, assisted 16,000 individuals, and closed 24,000 identified “care gaps” in 3 years. The pilot began with five community health assistants and expanded to 36 community health assistants, covering a much wider geography. Community health assistants work with patients to assess their home environment in order to better tailor care access. These health assistants report to a case management team that includes social workers as well as physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. The community health assistants take referrals from primary care physicians and case managers and also directly from community organizations, which can refer someone believed to have a social or health-related need that could benefit from outreach and assistance. In doing so, they make it easier for clinical details to be focused on by case managers.

- When the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities held a hearing on revising regulations concerning utility shutoffs, attorneys and health care team members from Boston Medical Center were able to successfully advocate for protection for high-risk patients during the winter season.9 This was achieved through the Boston Medical Center’s medical–legal partnership, a combined effort that involves attorneys, nurses, doctors, and other health team members. This partnership was able to offer on-site legal clinics within the medical center and screening that identified high-risk patients (such as those with sickle cell disease and asthma) whose health would suffer from utility power cuts. The screening protocol was then combined with training programs for doctors, to ensure that the correct information for demonstrating medical need was included in protection letters for patients. This combined effort protected 193 people during the first year alone and led to a joint testimony that resulted in the regulation itself being changed.

___________________

8 For more information, see https://www.bettercareplaybook.org/_blog/2018/16/geisinger-health-system-deploys-community-health-workers-address-social-determinants (accessed on July 16, 2019).

9 For more information, see https://medical-legalpartnership.org/response/utilities-case-study (accessed on July 16, 2019).

FINDINGS

- Effectively integrating social care into the delivery of health care requires effective interprofessional teams that include experts in social care.

- The social care workforce can include many types of workers. Social workers are specialists in providing social care who have a long history of working within health care delivery. Models that include community health workers show promise. As models continue to evolve and develop, roles may expand for other workers, such as social service navigators, aides, and assistants; trained volunteers; home health aides and personal care aides; and family caregivers. Other fields are emerging to meet the social needs of older adults (e.g., gerontology) and other specific populations. Integrating other professions—such as lawyers through medical–legal partnerships—also holds promise.

- Understanding the role each member of an interprofessional team plays in the awareness, adjustment, assistance, alignment, and advocacy activities is important for ensuring effective collaboration among team members and for maximizing their ability to address patients’ social needs.

- In order to effectively address social care in the delivery of health care, interprofessional team members should operate at their full scope of practice. Federal, state, and institutional barriers limit the scope of practice and the full use of social workers and other social care workers in caring for patients, such as in providing care management as part of an interprofessional team.

- For interprofessional teams to effectively address social care in the context of health care financing structures need to be aligned. Federal, state, and institutional barriers exist that may limit the adequate payment of social workers, gerontologists, and other social care workers.

- Research is needed on workforce issues related to integrating social care and health care, including studying the effect on health and financial outcomes of various configurations of the health care workforce intended to better address the social needs of the population served.

REFERENCES

AACN (American Association of Colleges of Nursing). 2008. The essentials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing practice. http://www.aacnnursing.org/portals/42/publications/baccessentials08.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

ACGME/ABFM (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and American Board of Family Medicine). 2015. The Family Medicine Milestone Project. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/FamilyMedicineMilestones.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

AGHE (Association for Gerontology in Higher Education). 2014. Gerontology competencies for undergraduate and graduate education. Washington, DC: Association for Gerontology in Higher Education. https://www.aghe.org/images/aghe/competencies/gerontology_competencies.pdf (accessed May 24, 2019).

AGHE. 2019. Learn about careers in aging. Association for Gerontology in Higher Education. https://www.pdx.edu/ioa/sites/www.pdx.edu.ioa/files/learnaboutcareersinaging.pdf (accessed May 24, 2019).

Altfeld, S. J., K. Pavle, W. Rosenberg, and I. Shure. 2013. Integrating care across settings: The Illinois Transitional Care Consortium’s Bridge model. Generations 36(4):98–101. https://www.apa.org/careers/resources/guides/careers (accessed May 24, 2019).

Ambrose-Miller, W., and R. Ashcroft. 2016. Challenges faced by social workers as members of interprofessional collaborative health care teams. Health & Social Work 41(2):101–109.

APHA (American Public Health Association). 2019. Community health workers. https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers (accessed April 20, 2019).

BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics). 2019. What lawyers do. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/legal/lawyers.htm (accessed March 25, 2019).

Bodenheimer, T., and C. Sinsky. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine 12(6):573–576.

Boutwell, A. E., M. B. Johnson, and R. Watkins. 2016. Analysis of a social work–based model of transitional care to reduce hospital readmissions: Preliminary data. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 64(5):1104–1107.

Bride, B. E. 2007. Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work 52(1):63–70.

Buhler-Wilkerson, K. 1993. Bringing care to the people: Lillian Wald’s legacy to public health nursing. American Journal of Public Health 32(12):1778–1786.

California Department of Health Care Services. 2019. Home and community-based services (HCBS) billing codes and reimbursement rates. https://files.medi-cal.ca.gov (accessed August 20, 2019).

Cate, O. T. 2013. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 5(1):157–158.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2016. A summary of state community health worker laws. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/SLFS-Summary-State-CHW-Laws.pdf (accessed August 13, 2019).

Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry. 2016. Addressing the social determinants of health: The role of health professions educations. https://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/actpcmd/actpcmd_13th_report_sdh_final.pdf (accessed August 20, 2019).

Council on Graduate Medical Education. 2016. Supporting diversity in the health professions. https://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/cogme/Publications/diversityresourcepaper.pdf (accessed August 20, 2019).

De Marchis, E., M. Knox, D. Hessler, R. Willard-Grace, J. N. Olayiwola, L. E. Peterson, K. Grumbach, and L. M. Gottlieb. 2019. Physician burnout and higher clinic capacity to address patients’ social needs. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 32(1):69–78.

Doobay-Persaud, A., M. D. Adler, T. R. Bartell, N. E. Sheneman, M. D. Martinez, K. A. Mangold, P. Smith, and K. M. Sheehan. 2019. Teaching the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education: A scoping review. Journal of General Internal Medicine 34(5):720–730.

Eelen, S., S. Bauwens, C. Baillon, W. Distelmans, E. Jacobs, and A. Verzelen. 2014. The prevalence of burnout among oncology professionals: Oncologists are at risk of developing burnout. Psychooncology 23(12):1415–1422.

Ellner, A. L., and R. S. Phillips. 2017. The coming primary care revolution. Journal of General Internal Medicine 32(4):380–386.

Family Caregiver Alliance. 2016. Caregiver statistics: Demographics. https://www.caregiver.org/caregiver-statistics-demographics (accessed March 20, 2019).

Fee, E., and M. E. Garofalo. 2010. Florence Nightingale and the Crimean War. American Journal of Public Health 100(9):1591.

Fraser, M. W., B. M. Lombardi, S. Wu, L. de Saxe Zerden, E. L. Richman, and E. P. Fraher. 2018. Integrated primary care and social work: A systematic review. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 9(2):175–215.

Frenk, J., L. Chen, Z. A. Bhutta, J. Cohen, N. Crisp, T. Evans, H. Fineberg, P. Garcia, Y. Ke, P. Kelley, B. Kistnasamy, A. Meleis, D. Naylor, A. Pablos-Mendez, S. Reddy, S. Scrimshaw, J. Sepulveda, D. Serwadda, and H. Zurayk. 2010. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet 376(9756):1923–1958.

Fulmer, T., L. Guadagno, C. Bitondo, and M. T. Connolly. 2004. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52(2):297–304.

Gard, L. A., J. Peterson, C. Miller, N. Ghosh, Q. Youmans, A. Didwania, S. D. Persell, M. Jean-Jacques, P. Ravenna, M. J. O’Brien, and M. S. Goel. 2018. Social determinants of health training in U.S. primary care residency programs: A scoping review. Academic Medicine 94(1):135–143.

Garfield, C., and S. Kangovi. 2019. Integrating community health workers into health care teams without coopting them. Health Affairs blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190507.746358/full (accessed August 6, 2019).

Gehlert, S., and T. Browne. 2011. Handbook of health and social work. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Glaser, B., and E. Suter. 2016. Interprofessional collaboration and integration as experienced by social workers in health care. Social Work in Health Care 55(5):395–408.

Greer, P. J., Jr., D. R. Brown, L. G. Brewster, O. G. Lage, K. F. Esposito, E. B. Whisenant, F. W. Anderson, N. K. Castellanos, T. A. Stefano, and J. A. Rock. 2018. Socially accountable medical education: An innovative approach at Florida International University Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine. Academic Medicine 93(1):60–65.

Hart, S. M., and A. M. Warren. 2013. Understanding nurses’ work: Exploring the links between changing work, labour relations, workload, stress, retention and recruitment. Economic and Industrial Democracy 36(2):305–329.

Heisler, E. J. 2018. The mental health workforce: A primer. Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43255.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2006. The rationale for diversity in the health professions: A review of the evidence. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

HHS. 2010. HHS announces the nation’s new health promotion and disease prevention agenda. healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/DefaultPressRelease_1.pdf (accessed August 13, 2019).

HHS. 2017. Sex, race, and ethnic diversity of U.S. health occupations (2011–2015). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/diversityushealthoccupations.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

Hoge, M. A., J. A. Morris, M. Laraia, A. Pomerantz, and T. Farley. 2014. Core competencies for integrated behavioral health and primary care. Washington, DC: SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions.

Houston, R., and R. Mahadevan. 2015. Supporting social service delivery through Medicaid accountable care organizations: Early state efforts. Center for Health Care Strategies. https://www.chcs.org/media/Supporting-Social-Service-Delivery-Final_0212151.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2016. Addressing the social determinants of health: The role of health professions education. https://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/actpcmd/actpcmd_13th_report_sdh_final.pdf (accessed August 13, 2019).

HRSA 2018a. Behavioral health workforce projections, 2016–2030. National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/Behavioral-Health-Workforce-Projections.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

HRSA. 2018b. Health careers. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/grants/healthcareers (accessed May 26, 2019).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003a. Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2003b. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2008. Retooling for an aging America: Building the health care workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012. The mental health and substance use workforce for older adults: In whose hands? Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2015. Measuring the impact of interprofessional education on collaborative practice and patient outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IPEC (Interprofessional Education Collaborative). 2011. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice. https://www.aacom.org/docs/default-source/insideome/ccrpt05-10-11.pdf?sfvrsn=77937f97_2 (accessed May 26, 2019).

Jack, H. E., S. D. Arabadjis, L. Sun, E. E. Sullivan, and R. S. Phillips. 2017. Impact of community health workers on use of healthcare services in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine 32(3):325–344.

Kangovi, S., N. Mitra, L. Turr, H. Huo, D. Grande, and J. A. Long. 2017. A randomized controlled trial of a community health worker intervention in a population of patients with multiple chronic diseases: Study design and protocol. Contemporary Clinical Trials 53:115–121.

Kangovi, S., N. M. Mitra, L. Norton, R. Harte, X. Zhao, T. Carter, D. Grande, and J. A. Long. 2018. Effect of community health worker support on clinical outcomes of low-income patients across primary care facilities: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 178(12):1635–1643.

Kim, L. Y., D. E. Rose, L. M. Soban, S. E. Stockdale, L. S. Meredith, S. T. Edwards, C. D. Helfrich, and L. V. Rubenstein. 2018. Primary care tasks associated with provider burnout: Findings from a Veterans Health Administration survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(1):50–56.

La Motte, E. 2012. The nurse as a social worker. Public Health Nursing 29(2):185–187.

Leipzig, R. M., K. Sauvigne, L. J. Granville, G. M. Harper, L. M. Kirk, S. A. Levine, L. Mosqueda, S. M. Parks, H. M. Fernandez, and J. Busby-Whitehead. 2014. What is a geriatrician? American Geriatrics Society and Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs end-of-training entrustable professional activities for geriatric medicine. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 62(5):924–929.

Lin, V. W., J. Lin, and X. Zhang. 2016. U.S. social worker workforce report card: Forecasting nationwide shortages. Social Work 61(1):7–15.

Lombardi, B. M., L. de Saxe Zerden, and E. L. Richman. 2017. Toward a better understanding of social workers on integrated care teams. http://www.behavioralhealthworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Y2FA2P2_UNC-Social-Work-Full-Report.pdf (accessed August 20, 2019).

Long, P., M. Abrams, A. Milstein, G. Anderson, K. Lewis Apton, M. Lund Dahlberg, and D. Whicher (eds.). 2017. Effective care for high-need patients: Opportunities for improving outcomes, value, and health. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

Malcarney, M. B., P. Pittman, L. Quigley, K. Horton, and N. Seiler. 2017. The changing roles of community health workers. Health Services Research 52(Suppl 1):360–382.

Mangold, K. A., T. R. Bartell, A. A. Doobay-Persaud, M. D. Adler, and K. M. Sheehan. 2019. Expert consensus on inclusion of the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education curricula. Academic Medicine, January 14 [Epub ahead of print].

Martin, U., and S. P. Schinke. 1998. Organizational and individual factors influencing job satisfaction and burnout of mental health workers. Journal of Social Work in Health Care 28(2):51–62.

Martsolf, G. R., D. J. Mason, J. Sloan, C. G. Sullivan, and A. M. Villarruel. 2017. Nurse-designed care models and culture of health. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Medves, J., C. Godfrey, C. Turner, M. Paterson, M. Harrison, L. MacKenzie, and P. Durando. 2010. Systematic review of practice guideline dissemination and implementation strategies for healthcare teams and team-based practice. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 8(2):79–89.

Molyneux, J. 2001. Interprofessional teamworking: what makes teams work well? Journal of interprofessional care 15(1):29–35.

Mullan, F. 2017. Social mission in health professions education: Beyond Flexner. JAMA 318(2):122–123.

NACHW (National Association of Community Health Workers). 2019. NACHW home page. https://nachw.org (accessed May 26, 2019).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016a. A framework for educating health professionals to address the social determinants of health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016b. Systems practices for the care of socially at-risk populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2017. Strengthening the workforce to support community living and participation for older adults and individuals with disabilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASHP (National Academy for State Health Policy). 2017. State Community Health Worker Models. https://nashp.org/state-community-health-worker-models (accessed August 8, 2019).

NASW (National Association of Social Workers). 2005. NASW standards for clinical social work in social work practice. https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=YOg4qdefLBE%3D&portalid=0 (accessed August 20, 2019).

NASW. 2016. NASW standards for social work practice in health care settings. https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=fFnsRHX-4HE%3D&portalid=0 (accessed May 26, 2019).

NC DHHS (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services). 2019. Community health worker initiative. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities/community-health-worker-initiative (accessed April 15, 2019).

Newman, L., F. Baum, S. Javanparast, K. O’Rourke, and L. Carlon. 2015. Addressing social determinants of health inequities through settings: A rapid review. Health Promotion International 30:126–143.

Olayiwola, J. N., R. Willard-Grace, K. Dubé, D. Hessler, R. Shunk, K. Grumbach, and L. Gottlieb. 2018. Higher perceived clinic capacity to address patients’ social needs associated with lower burnout in primary care providers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 29(1):415–429.

Olds, D. L., L. Sadler, and H. Kitzman. 2007. Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: Recent evidence from randomized trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 48(3–4):355–391.

Pantell, M. S., E. De Marchis, A. Bueno, and L. M. Gottlieb. 2019. Practice capacity to address patients’ social needs and physician satisfaction and perceived quality of care. Annals of Family Medicine 17(1):42–45.

Parks, S. M., G. M. Harper, H. Fernandez, K. Sauvigne, and R. M. Leipzig. 2014. American Geriatrics Society/Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs curricular milestones for graduating geriatric fellows. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 62(5):930–935.

Pecukonis, E., O. Doyle, S. Acquavita, E. Aparicio, M. Gibbons, and T. Vanidestine. 2013. Interprofessional leadership training in MCH social work. Social Work Health Care 52(7):625–641.

Regenstein, M., J. Trott, A. Williamson, and J. Theiss. 2018. Addressing social determinants of health through medical–legal partnerships. Health Affairs (Millwood) 37(3):378–385.

Reinhard, S., C. Levine, and S. Samis. 2012. Home alone: Family caregivers providing complex chronic care. AARP’s Public Policy Institute. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/health/home-alone-family-caregiversproviding-complex-chronic-care-rev-AARP-ppi-health.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

Reuben, D. B., L. Levy-Storms, M. N. Yee, M. Lee, K. Cole, M. Waite, L. Nichols, and J. C. Frank. 2004. Disciplinary split: A threat to geriatrics interdisciplinary team training. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52(6):1000–1006.

Rosenthal, E. L., C. H. Rush, and C. G. Allen. 2016. Understanding scope and competencies: A contemporary look at the United States community health worker field. https://www.healthreform.ct.gov/ohri/lib/ohri/work_groups/chw/chw_c3_report.pdf (accessed May 26, 2019).

Siegel, J., D. L. Coleman, and T. James. 2018. Integrating social determinants of health into graduate medical education: A call for action. Academic Medicine 93(2):159–162.

Sims, S., G. Hewitt, and R. Harris. 2015. Evidence of collaboration, pooling of resources, learning and role blurring in interprofessional healthcare teams: a realist synthesis. Journal of Interprofessional Care 29 (1):20–25.

Tahan, H. A., W. T. Downey, and D. L. Huber. 2006. Case managers’ roles and functions: Commission for Case Manager Certification’s 2004 research, part II. Lippincott’s Case Manager 11(2):71–87, quiz 88–89.

USC (University of Southern California). 2019. Do you know the difference between micro-, mezzo- and macro-level social work? https://dworakpeck.usc.edu/news/do-you-know-the-difference-between-micro-mezzo-and-macro-level-social-work (accessed May 24, 2019).

Wakefield, M. 2014. Improving the health of the nation: HRSA’s mission to achieve health equity. Public Health Reports 129(Suppl 2):3–4.

Warshaw, G. A., and E. J. Bragg. 2014. Preparing the health care workforce to care for adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Health Affairs (Millwood) 33(4):633–641.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010a. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en (accessed August 13, 2019).

WHO. 2010b. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related millennium development goals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/chwreport/en (accessed August 13, 2019).

Williams, D. R., M. V. Costa, A. O. Odunlami, and S. A. Mohammed. 2008. Moving upstream: How interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice 14(Suppl):S8–S17.

Xiang, X., A. Zuverink, W. Rosenberg, and E. Mahmoudi. 2018. Social work-based transitional care intervention for super utilizers of medical care: A retrospective analysis of the bridge model for super utilizers. Social Work in Health Care 14:1–16.

Zarrella, D. 2005. Resource manual: Social workers & social work services as defined in Medicare law & regulations. National Association of Social Works. https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=IyaZ9lqQfLQ%3D&portalid=0 (accessed May 26, 2019).

Zomorodi, M., T. Odom, N. C. Askew, C. R. Leonard, K. A. Sanders, and D. Thompson. 2018. Hotspotting: Development of an interprofessional education and service learning program for care management in home care patients. Nurse Educator 43(5):247–250.

This page intentionally left blank.