2

Integrating Oral Health, Primary Care, and Health Literacy1

To provide background for the discussions at the workshop, Kathryn Atchison, professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), School of Dentistry, and in the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, summarized the main conclusions of a paper commissioned by the roundtable, titled “Integrating Oral Health, Primary Care, and Health Literacy: Considerations for Health Professional Practice, Education, and Policy.”2 Atchison’s co-authors on the paper were Gary Rozier and Jane Weintraub, both at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

IDENTIFYING RESOURCES FOR THE ENVIRONMENTAL SCAN

Using search criteria for U.S. articles published between 2000 and 2017, Atchison and her colleagues identified peer-reviewed articles and articles from the gray literature. They also identified and consulted with experts listed in conference programs, faculty members and administrators in dental and health professional schools with interprofessional educa-

___________________

1 This chapter is based on a presentation by Kathryn Atchison, professor in the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), School of Dentistry, and in the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, summarizing a paper commissioned by the Roundtable on Health Literacy, “Integrating Oral Health, Primary Care, and Health Literacy: Considerations for Health Professional Practice, Education, and Policy,” by Kathryn Atchison, Gary Rozier, and Jane Weintraub. Her statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

2 See www.nationalacademies.org/HealthLiteracyRT (accessed May 30, 2019) to download the complete paper.

tion programs, representatives of foundations that have funded integration programs, and government officials from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). They posted notices about the project on two listservs—a health literacy listserv and a dental public health listserv—and asked people doing studies that had not yet been published if they would share their results. They excluded intradisciplinary programs (such as adding mid-level providers to dental programs), stand-alone demonstration programs integrating primary care into dental practice, and stand-alone public health programs with no connection to primary care practice. “We conducted a unilateral, unidirectional review of oral health into primary care,” said Atchison in her presentation at the workshop.

To identify the scope of practice for integration, they reviewed guidelines, consensus statements, and national surveys related to what dentists are doing in general health and what physicians are doing in dentistry. They also noted that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reviewed services related to integration three times, Atchison added. Only in the case of pediatric providers conducting preventive oral health services did the task force find enough evidence to make recommendations.3 With both coronary heart disease and oral cancer, the task force found insufficient evidence to make recommendations.4 As Atchison said, these results indicate a lack of current research on integration.

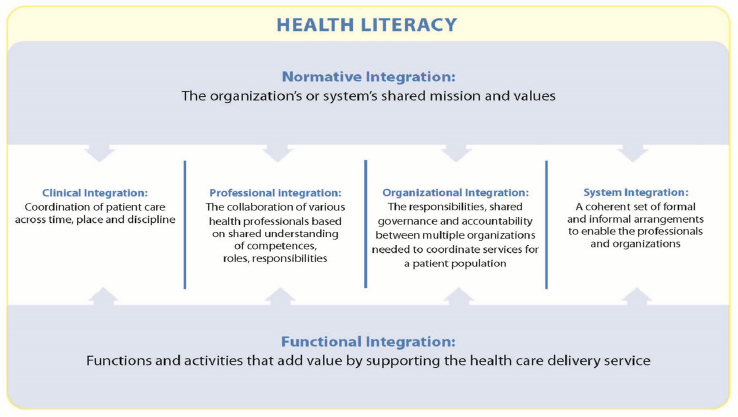

Atchison and her colleagues next sought an integrated care conceptual model that was broad enough to describe demonstrations of integration at multiple levels within an organization. The Rainbow Method of Integrated Care incorporates both functional integration and normative integration at four levels within an organization—the clinic, the professional, the organization, and the system. Atchison described how she and her colleagues modified this model to incorporate health literacy (see Figure 2-1). Reflecting features of this model, they then developed four categories of integration—three involving the integration of oral health into primary care and the fourth involving the accompanying integration of preventive health services provided by dental providers in dental settings:

___________________

3 The recommendations and supporting documents are available at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/dental-caries-in-children-from-birth-through-age-5-years-screening (accessed April 4, 2019).

4 The recommendations and supporting documents are available at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/coronary-heart-disease-screening-using-non-traditional-risk-factors (accessed April 4, 2019) and https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/oral-cancer-screening1 (accessed April 4, 2019).

SOURCES: As presented by Kathryn Atchison at the workshop Integrating Oral and General Health Through Health Literacy Practices on December 6, 2018; adapted from Valentjin et al., 2013, by Atchison et al., 2018.

- Preventive oral health services provided by medical providers

- Preventive health services provided by dental providers in primary care clinics or nontraditional settings

- Case management, coordination, and referral

- Preventive health (nondental) services provided by dental providers in dental settings, but only if accompanied by one of the kinds of integration listed above

RESULTS OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL SCAN

Atchison informed the workshop that the resulting environmental scan found 32 publications, including 15 that were peer reviewed and 17 in the gray literature. The programs represented 28 states plus Washington, DC, and the National Head Start Association. They included statewide programs, countywide programs, and urban and rural programs focused on clinical and system-level quality improvement. Multisite programs were organized by age group, type of practice, setting, and other features. They identified the literature that was available as “robust,” said Atchison, noting that it contains results on programs that have been tested in a variety of venues.

Of the 37 reports of preventive oral health services provided by medical providers (an article could have more than 1 report), 33 were on pediatric preventive oral health services, 10 were on medical providers who conducted oral health assessments for pregnant women and referred them to dentists, 5 involved patients who had chronic diseases (primarily diabetes), and 2 were not preventive but still involved integrating preventive oral health services into primary care (in Maine and New Mexico medical residents were trained to perform extractions because of a statewide paucity of dentists).

Atchison said that she and her colleagues found 16 examples of dental providers performing preventive and other oral health services in primary care clinics or nontraditional settings. These consisted mostly of dental services offered by hygienists to children in schools, services provided to pregnant women in primary care clinics, and services delivered in public health and community clinics. For example, in a rural area, a hygienist might work off site in a school or elsewhere with a physician rotating in once per month. Several publications referred to the introduction of dentists or dental residents into emergency departments to deal with emergencies and direct people to dental clinics.

Atchison added that they found 22 examples demonstrating integration of case management or coordination of care services. These related to increased access to dental services, community services, and social services, such as transportation, along with increased access to health education and prevention through navigation to dental clinics. “Different types of people, including social workers, community health workers, navigators, [and] nurses … were trying to assist patients to find appropriate primary care locations for their care,” Atchison said. Electronic tools also helped with this navigation.

Finally, Atchison and colleagues found 16 examples of preventive medical services performed by dental providers. For example, dentists would screen and refer patients to a medical home for hypertension, HIV, or blood glucose evaluations. Or a dentist might review care plans to find gaps in preventive services, such as immunizations. Atchison and colleagues found that once an organization did one integration model and discovered that it worked, the organization was more likely to try another.

In general, interest in integration was evident, said Atchison, but the peer-reviewed literature was sparse. Few guidelines exist for establishing such programs, and most of the guidelines that do exist involve physicians doing preventive oral health services. Some pilot studies have been done on implementing integrative programs, but few studies discuss their effectiveness or outcomes in improving oral or general health. A wide variety of information is available about the programs, but the information has little consistency.

The purpose of the studies also varied, noted Atchison. Some focused on educating people about how to integrate services. Others sought to determine best practices for integrating oral health into managed care or accountable care organizations, which have seen some of the strongest work toward developing and understanding integration, according to Atchison. Guidelines for how to conduct and report on studies of integration would be helpful, she added.

INCLUDING HEALTH LITERACY IN INTEGRATION EFFORTS

Health literacy is a facilitator to integration, Atchison pointed out. She listed several applications of health literacy to integration at the clinical level:

- Develop educational materials in relevant languages.

- Use anticipatory guidance during oral health screening of chronic disease patients.

- Develop and use case management and patient navigation.

- Ask patients about dental symptoms (such as toothache, bleeding gums, loose teeth, trouble chewing).

- Ask patients about medical and dental homes and about last medical/dental visit.

- Develop and/or coordinate individualized multidisciplinary care plans.

- Interact in a culturally competent manner.

- Track and follow up on referrals.

At the professional level of integration, Atchison said that applications of health literacy include the following:

- Train the primary care team on how to conduct an oral assessment and caries risk assessment.

- Develop a shared and culturally appropriate vision for a department.

- Develop/foster interdisciplinary collaborations.

- Develop and follow clinical guidelines/protocols.

- Develop interprofessional governance for the collaboration.

- Create value for providers and patients of federally qualified health centers (FQHCs).

As an example, Atchison mentioned a case study of the Grace Health FQHC in Michigan (Atchison et al., 2018). A dental hygienist had been moved into the obstetrics/gynecology clinic but was not able to use the clinic’s electronic health record to make follow-up appointments for patients.

In response, dentistry and the obstetrics/gynecology clinic worked together to open up the dental appointment system in the clinic’s electronic health record to enhance integration.

Atchison noted that applications of health literacy at the organization level include the following:

- Ensure that all providers have buy-in to planned integrative collaborations.

- Develop performance metrics for screening, caries prevention, dental sealant, etc.

- Develop a dental referral network.

- Demonstrate supportive leadership.

- Make cultural competency training available to all providers and staff.

Atchison said that a good example is from the Willamette Dental Group and the InterCommunity Health Network in Oregon, which together chose to concentrate on diabetes in response to a statewide health integration program that required organizations to develop pilot programs to address community problems. The medical and dental practices, which were separate entities, had to work together to develop a pilot program in which they would send education materials about diabetes and periodontal disease to medical patients who had diabetes. Physicians then asked patients if they had been to the dentist in the past year. If not, they had to do a referral, which was unusual; as one nurse said, “We are not used to doing referrals to dentists.” At the same time, the dental clinic had to identify people with a medical history of diabetes, ask them if they had seen a physician in the past year, and if not do a referral. “It does not seem like much, but it is very difficult to change practice like that,” said Atchison.

At the system level, she said that health literacy applications include the following:

- Interface with public health and community organizations.

- Determine community needs.

- Seek available resources to initiate needed programs.

- Develop and implement programs that meet the community’s needs.

- Demonstrate good community-participatory governance.

- Develop a positive climate.

HealthPartners provides a good example of a health-literate application at the system level, Atchison said. When the organization realized that patients experiencing homelessness were being released from surgical care

and had no place to go where they could practice effective postoperative care, senior management arranged to pay for housing for several days.

At the functional level, Atchison said that health literacy applications include the following:

- Develop accessible, integrated electronic record systems with clinical decision tools.

- Develop systems monitoring and benchmarks.

- Apply resource management.

- Develop needed support systems and services.

- Provide regular feedback on performance.

HealthPartners’s use of a patient experience questionnaire to measure patients’ satisfaction is an example of functional integration, Atchison observed. Similarly, the Willamette Dental Group used common screening questions for diabetic patients and organized a communication group that ensured that all communications and outreach were tailored to the appropriate reading level and language.

Finally, at the normative level, Atchison said that health literacy applications include the following:

- Foster visionary leadership to develop a dental home initiative.

- Create a shared vision for optimal oral health for all.

- Develop a collective attitude with the community.

- Let the community come to know you are a reliable, trustworthy partner.

- Create a sense of urgency about the community’s total health (including oral health).

- Build quality features of the collaboration at the operational, tactical, and strategic levels.

In the Willamette Dental Group’s transformation program in Oregon, integration partners took concrete steps for the collaboration by developing goals, considering the social determinants of health, and conducting a review of physician language to determine whether patients could understand their providers. Grace Health described their mission as looking “to fill gaps in the care system” for their community, which is why they focused on pregnant women.

TRAINING AND EDUCATION OF HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

To assess the type of training and education provided to health professional students and through continuing education, Atchison and her

colleagues reviewed the published literature from 1995 to 2017, training grants funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the websites of 43 nondental health professional associations, in addition to surveying the oral health curricula in nondental profession programs and the interprofessional education curricula in dental programs, and contacting key individuals and organizations.

This environmental scan identified a number of challenges to integration of oral health and health professional education and practice, she said. First, dental education programs were severely siloed. The United States has twice as many medical schools as dental schools, and many academic health centers lack a dental school. Even where the two were co-located, challenges to coordination included different schedules, different cultures, and a lack of interest in trying to change curricula. Atchison added that before 2000, oral health was almost nonexistent in primary care provider education. It is now included in predoctoral primary care or residency training, but it still generally accounts for less than five hours in the entire curriculum, she said. Furthermore, she added, little peer-reviewed and published research has been done on either integration or patient outcomes resulting from integration.

Continuing education is critical for training professionals who are in practice and not involved in an ongoing training program such as a residency, said Atchison. But she and her colleagues found it difficult to conduct a scan on continuing education because of the difficulty of accessing and determining the content and quality of continuing education programs. Also, the joint accreditation for interprofessional continuing education includes medicine, pharmacy, and nursing but not dentistry. And of the 43 websites of nondental health professional associations that were reviewed, 42 percent had minimal or no oral health information available.

Nonetheless, favorable changes are occurring in education and training, Atchison observed. The recognition is growing that nondental health providers can have a key role in improving oral health, especially for vulnerable and underserved populations, and new curriculum initiatives, toolkits, train-the-trainer programs, and webinars have become available. She cited a number of examples, such as adding an oral assessment to the general physical examination; the development of the nurse-practitioner-dentist model; referral networks built with local dental practices; the National Interprofessional Initiative on Oral Health and the Oral Health Nursing Education and Practice; New England’s Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative training programs and practices; and the online curriculum of Smiles for Life, which more than a quarter million people have been able to access. In addition, some organizations, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Physician Assistants, The Gerontological Society of America, and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine,

have been educating their members about oral health, though this material is still not a large proportion of the curriculum.

Facilitators for education and training include the interprofessional education accreditation standards across professions, oral health integration throughout the existing primary care curriculum that goes beyond just sitting in classrooms together, interprofessional education focused on clinical activities with team-based learning among different types of professional students, networks established with local dentists for help with teaching and referrals, nondental oral health champions, university and institutional leadership, internal and external funding to initiate and sustain educational activities, and the growth of large-group, multidisciplinary delivery systems. In particular, employers want graduates to be “practice ready” to work in teams, Atchison said.

CONCLUSIONS

The integration of oral health into primary care is in its infancy, Atchison concluded. Few guidelines or published surveys exist of integration except in early childhood. Few peer-reviewed studies have been done on integration, and most of those integration programs were pilot demonstrations and did not discuss effectiveness or outcomes in improving oral and general health. Atchison added that there are some projects in development to advance interprofessional education, but few programs have yet to appear in practice. At the same time, health literacy applications also exist, but they are generally offered by accountable care organizations.

A major challenge is to work outside of managed care and accountable care organizations with the majority of dental practitioners, who are still in private practice and are not part of a network, said Atchison. “There need to be ways that we can bring those people into the network so that they are able to communicate with physicians.”

This page intentionally left blank.