4

Health Literacy and Care Integration1

The second panel of the workshop explored in greater depth how health literacy and care integration can act together to improve health and well-being. One scheduled speaker, Brian Hill, the founder and executive director of the Oral Cancer Foundation, suffered a medical emergency related to his long-term health issues and could not attend the workshop. Hill is a stage IV oral cancer survivor and, in the words of session moderator Alice Horowitz, research associate professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Health, “has probably done more to raise awareness about oral cancers than any other single person in the world.” Horowitz noted that the workshop would miss hearing about his 20 years of experience dealing with the many things that, as he has put it, “fall through the cracks when dentistry and medicine are detached from what should be their common grounds.”

THE NEED FOR PUBLIC HEALTH LITERACY

Dean Schillinger, professor of medicine in residence at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and chief of the UCSF Division of General Internal Medicine at San Francisco General Hospital, opened the panel

___________________

1 This chapter is based on presentations by Dean Schillinger, professor of medicine in residence at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), chief of the UCSF Division of General Internal Medicine at San Francisco General Hospital, and director of its Health Communications Research Program; and Meg Booth, executive director of the Children’s General Health Project. Their statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

by discussing a particular form of literacy: public health literacy. Schillinger defined public health literacy as the degree to which individuals and groups can obtain, process, understand, evaluate, and act on information needed to make public health decisions that benefit the community (Freedman et al., 2009; Schillinger et al., 2018). The target populations for communications designed to build public health literacy are the general public and policy makers, not just patients or clinicians, and the purpose of these communications is to improve the health of the general public. The objectives of greater public health literacy are to engage more stakeholders in public health and prevention efforts—beyond clinicians, the people who are affected, and advocates—so as to better address the upstream determinants of health that drive the burden of suffering and health care costs.

Public health literacy is a multidimensional construct, Schillinger said. At its conceptual foundation is the socio-ecological model of health, a concept that has been accepted and operationalized more in Europe than in the United States. Public health literacy also requires a degree of critical skills and critical thinking—“so that one can reconcile the difference between what one sees and what one believes, and how one explains the world”—and a civic orientation based on the idea that actions not immediately beneficial to an individual will be beneficial at a later date to that individual, their families, and their community.

From the 21 recommendations in the commissioned report, Schillinger cited three that are particularly relevant to public health literacy:

- Apply a comprehensive framework that includes integration theory, oral health, primary care, and health literacy into [public health] practice, education, research, and policy making. (Schillinger said that he added the term “public health” to expand the recommendation beyond clinical practice.) (Recommendation 1)

- Prioritize oral health promotion and disease prevention in integration activities in order to reduce disparities. (Recommendation 5)

- Encourage the conduct of studies of the impact of health literacy on integration of primary oral health services into primary care and preventive health services into dentistry. (Recommendation 14)

Schillinger both expanded on and applied these recommendations particularly to vulnerable populations, which he defined, drawing on epidemiology, as subgroups of the larger population that, because of social, economic, political, structural, geographic, and/or historical forces, are exposed to greater risks and are thereby at a disadvantage with respect to their health and health care (Frolich and Potvin, 2008; Schillinger et al., 2017). He noted that this definition frames the problem as one of exposures and not behaviors, thereby eliminating some of the “shame and blame” that

is associated with the higher burden of disease in poor people. “It is not something intrinsic to the individuals that makes them socially vulnerable,” he said. “It is how we have constructed our society that makes an individual socially vulnerable. You can transplant someone from one society into another and they may not be socially vulnerable in that second society.”

Schillinger listed the common social vulnerabilities using an acronym (see Box 4-1). This list is not exhaustive, Schillinger acknowledged, but it covers many of the social exposures that affect health, and these social issues generally have a much greater effect on health outcomes than the health care someone receives.

These social factors are particularly influential given the limited reach of health care and dental care. Schillinger reviewed some of the numbers drawn from studies of the ecology of health care. He explained that over the course of 1 year, of 1,000 children younger than age 18, only 167 will visit a physician’s office and only 82 will visit a dentist’s office. He added that the comparable figures for adults ages 18 and older are just 235 and 73, respectively.

Access is even more limited for vulnerable populations. Schillinger cited the inverse care law—“access to and quality of health care is inversely proportional to the needs of the population” (Tudor-Hart, 1971)—noting

that this rule began as a hypothesis “but now it is known as a law, because it has been shown in every society to be true.” Much of progressive health policy has sought to reverse or mitigate this inverse care law.

While most well studied in medical care, the inverse care law applies to oral health just as it does to physical and mental health, Schillinger observed. Among low-income adults, 42 percent have difficulty biting and chewing, 23 percent reduce participation in social activities due to the condition of their mouth and teeth, 35 percent feel embarrassment due to the condition of their mouth and teeth, and 37 percent avoid smiling due to the condition of their mouth and teeth.2 Though 77 percent of adults say they intend to visit a dentist in the next year, the actual figures depend on income, ranging from 91 percent for high-income adults to 74 percent for middle-income adults to 62 percent for low-income adults, even though lower-income adults have greater oral health needs (Harris et al., 2015). The same observation applies to dental visits. Of the 37 percent of adults who actually visited a dentist within the past year, 51 percent of high-income adults did so, compared with 31 percent of middle-income adults and 20 percent of low-income adults. Because of low reimbursement rates and variable inclusion of dental care as part of public health insurance, Medicaid does not solve this problem for oral health, though it somewhat mitigates it.

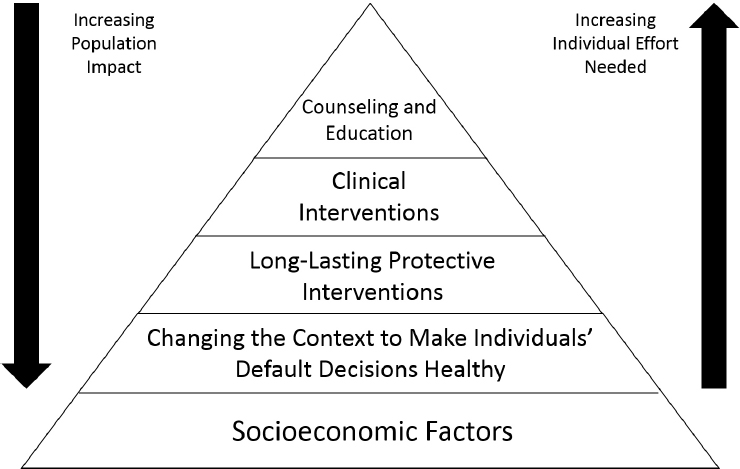

Schillinger cited work by Thomas R. Frieden (2010), as part of his population health pyramid, showing that focusing on socioeconomic factors, changing the context to make individuals’ default decisions healthy, and implementing long-lasting protective interventions have a greater impact on the overall population than do clinical interventions, counseling, and education (see Figure 4-1). In his presentation, Schillinger focused on the first two of these high-impact factors, while touching on the third.

SHARED RISK EXPOSURES AND THE CYCLE OF DISEASE: ADDED SUGAR, NONFLUORIDATED WATER

Why is public health literacy so important for the integration of oral and primary health services? Schillinger asked. First, most oral health, physical health, and mental health problems are driven by common, shared-risk exposures (Schillinger et al., 2018). As a result, these three categories of health problems are linked. “These should not be viewed as siloed health conditions,” said Schillinger. “Social vulnerability, acting through differential exposures to risk and resources (including access), can impact one or more of the three dimensions of health, in interrelated fashions.”

___________________

2 These and many other measures of oral health are available at https://www.ada.org/en/science-research/health-policy-institute/oral-health-and-well-being (accessed April 23, 2019).

SOURCES: Adapted from a presentation by Dean Schillinger at the workshop in Integrating Oral and General Health Through Health Literacy Practices on December 6, 2018; and from Frieden, 2010.

At the same time, greater social vulnerability elevates risk exposures that jeopardize all three dimensions of health. Disease burden in any of the three domains often leads to downward economic mobility, generating greater social vulnerability and creating a vicious cycle that leads to an even greater disease burden.

As such, addressing common social determinants can prevent risk exposure and reduce health disparities across all three health dimensions. Preventing exposures to common risk factors is an efficient, clinically effective, and cost-effective approach to improving oral, physical, and mental health, Schillinger said. He added that secondary prevention, through either public health or clinical interventions, for systemic diseases or diseases of the oral cavity may yield collateral benefits across other health dimensions. Thus, secondary prevention as well as primary prevention adds value.

As an example, Schillinger pointed out that one in eight adult Americans has diabetes. Access to medical, mental, and oral health care for these and other people, whether integrated or not, is essential but insufficient. Unless public health literacy is addressed, the underlying problems will not be solved.

Schillinger provided several other examples of how preventing exposures to common and shared risk factors can be efficient, clinically effective, and cost effective:

- Diet, specifically added sugars and sugar-sweetened beverages, is a major cause of caries, periodontal disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and depression.

- Nonfluoridated water can lead to tooth loss, which can lead to poor dietary quality and intake, malnutrition, and anxiety and depressive symptoms (leading to chronic illness).

- Tobacco use is much more likely in people with depression and schizophrenia, and tobacco use can lead to a wide variety of systemic diseases.

- Excess alcohol use, itself a behavioral health problem, can lead to oral health problems, cancer, liver disease, and cardiovascular disease, among other problems.

These common epidemiologic risk factors are concentrated primarily in socially vulnerable populations, Schillinger observed. He discussed as an example the correlations in San Francisco between the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, low income, diabetes hospitalization rates (which can differ 10-fold by neighborhood), and caries prevalence among kindergartners. Despite the existence of all these correlations, when San Francisco was debating whether to impose a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages, journalists, tax advocates, and others in news stories most often connected sugary drinks to obesity and diabetes, not to oral health (Somji et al., 2016). Though dental caries is the most prevalent chronic disease caused by consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, diabetes was discussed 17 times and obesity 19 times more frequently than oral health consequences. When oral health appeared, it was mentioned only in passing or briefly listed among other chronic diseases.

On a related issue, Schillinger described an effort in San Francisco to pass an ordinance that would require warning labels on advertisements for sugary drinks saying, “Warning: drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay. This is a message from the City and County of San Francisco.” Originally scheduled to go into effect in 2016, trade groups for the beverage and billboard industries claimed that such a warning would infringe on their constitutional free-speech rights and that its content was false, misleading, and scientifically controversial. Expert testimony written by the former scientific director of the American Diabetes Association claimed that there is no evidence that sugary drinks cause cavities, among other health problems. In response, Schillinger, who provided expert testimony on behalf of the city, wrote an article about

how industry had hijacked science to undermine truth and was placing the public’s health at significant jeopardy (Schillinger et al., 2018). As such, promoting public health literacy related to the interrelationships between physical and oral health is critical.

Schillinger explained that another exposure that disproportionately affects vulnerable populations and their oral health is nonfluoridated water. He also noted that bottled water is the fastest growing drink choice in the United States, representing expenditures of more than $100 per year per person, and is hundreds of times more expensive than tap water. But, Schillinger added, only 15 bottled water products out of 640 represented by the International Bottled Water Association contain fluoride. “The regulatory standards on this are simply inadequate,” said Schillinger. If bottled water meets specific standards from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, manufacturers may include the following health claim: “Drinking fluoridated water may reduce the risk of [dental caries or tooth decay].” But there is no affirmative warning label to state that a bottled water does not contain fluoride. In fact, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency only states on its website that consumers are encouraged to “check with bottlers to find out if their water contains fluoride.”

The consumption of tap and bottled water differs by race, ethnicity, nativity, and education. One-third of U.S. adults drink bottled water on any given day, and non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, and adults born outside of the 50 United States and Washington, DC, had 2.20, 2.37, and 1.46 times the odds, respectively, of consuming bottled water than their non-Hispanic white and U.S.-born counterparts (Rosinger et al., 2018). At the same time, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults had 0.44 and 0.55 times the odds, respectively, of consuming (fluoridated) tap water compared with non-Hispanic whites. Low-income parents and caregivers of young children in Maryland rarely drink tap water and do not give it to their children; rather, they use bottled water and were found to have a limited understanding of the use of fluoride to prevent caries (Horowitz et al., 2015). Of note, Schillinger added, low-income and racial and ethnic minority populations often drink sugar-sweetened beverages at higher rates, creating synergistic risk.

Water filtration has been associated with higher odds of drinking plain or tap water, but filtration has differing effects on fluoride. Reverse osmosis, which is the most common sink-filter system, as well as distillation and active alumina filtration systems, all remove fluoride, whereas carbon filters do not remove fluoride. “This too is a public health literacy issue,” said Schillinger.

The use of fluoride varnish as a long-lasting protective intervention is another public health issue, Schillinger added. If other preventive measures, like the influenza vaccine, can be available at a local drugstore rather than a health clinic, fluoride varnishes could become similarly available. “We

should really be thinking about this as a public health literacy campaign as well,” he said.

Schillinger briefly listed some of the other preventable risk exposures that jeopardize all three dimensions of health. Food insecurity leads to poor dietary quality because people tend to eat calorically dense foods, which leads to caries, gum disease, tooth loss, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, stress, and depression—all from one social determinant. Domestic violence and trauma can lead to tooth loss, poor dietary quality, diabetes, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression. Low educational attainment and limited health literacy can lead to high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and poor oral health; Schillinger mentioned that consumers with low health literacy drink on average 240 calories of soda per day more than those with high health literacy. Immigration status can lead to poor access to health care, which leads to problems in all three health dimensions, and poverty adds poor access to resources to poor access to care.

Greater rates of illness in any of these three dimensions can lead to downward economic mobility and greater social vulnerability. Schillinger cited newspaper stories (Frakt, 2018), books (Otto, 2017), magazines (Gaffney, 2017), and academic research that all make this point. The American Dental Association found that one-third of adults with incomes less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level—meaning that they could be eligible for Medicaid in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act expansion states—reported that the appearance of their teeth and mouth affected their ability to interview for a job, versus just 15 percent of people with incomes above four times the federal poverty level.3 Another study found that fluoridation increased the earnings of women by 4 percent on average, and even more for women of low socioeconomic status (Glied and Neidell, 2008). A randomized controlled trial in Brazil, which showed employers two images of the same person, one with no dental problems and one with uncorrected teeth, found that those with dental problems were perceived to be less intelligent and less likely to be considered suitable for hiring (Pithon et al., 2014).

Finally, Schillinger mentioned the issue of secondary prevention—and specifically the interactions between diabetes, periodontitis, and depression (Kane, 2017; Preshaw et al., 2012). Hyperglycemia negatively affects oral health, increasing the risk of periodontitis three-fold along with other oral health problems, including alveolar bone loss, abscess formation, and poor healing. In turn, periodontitis negatively impacts glycemic control in diabetes and leads to inflammatory responses that accelerate complications such as heart attacks and kidney failure. Treatment of gingivitis can

___________________

3 These and many other measures of oral health are available at https://www.ada.org/en/science-research/health-policy-institute/oral-health-and-well-being (accessed April 4, 2019).

improve glycemic control, while treatment of diabetes can improve oral health. Both tooth loss and diabetes are potent triggers for depression, and depression treatment can improve oral hygiene and diabetes control. The costs and disability related to excess care for dental and diabetes complications can have severe economic consequences, leading to stress, depression, downward income mobility, and poverty. “The economic consequences of dental problems reflect both direct (health care–related) and indirect (work productivity) costs, but are largely unstudied,” said Schillinger.

COUNTERING HARMFUL COMMUNICATIONS

The messages being communicated to the public around risk factors are entirely misaligned with public health literacy principles, said Schillinger, instead focusing on personal choice and behaviors. One campaign to counter harmful communications has been undertaken by an initiative called The Bigger Picture, which encourages young people to “raise your voice and join the conversation about diabetes.”4 Four of the 25 short films created by The Bigger Picture integrate oral, physical, and mental health in their prevention messages. Schillinger particularly recommended the films Bottled Up, which is about the value of fresh water, and Chocolate Smile, which frames the disproportionate marketing and exposure of sweets to young people of color—and its physical and oral health consequences—as a social justice issue.

Public health communications and advocacy efforts need a more integrated set of messages across physical and oral health, Schillinger observed. He has been working with a group of physicians and dentists to build these skills in a program called the Champion Provider Fellowship, which is run out of UCSF and funded in part by the California Department of Public Health and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.5 The program provides a model for harnessing public health literacy for oral and general health and is building skills for policy, systems, and environmental change. At the time of the workshop, it had 78 current Champion Provider Fellows, including 10 dentists, many of whom had years of experience in their professions.

Many other programs exist to counter the social determinants that harm health across physical and oral health domains. For example, Schillinger mentioned a program in the San Francisco area called EatSF, which provides vouchers to low-income people to buy fresh fruits and vegetables, thereby

___________________

4 More information about the campaign is available at http://www.thebiggerpictureproject.org (accessed April 4, 2019).

5 More information about the program is available at https://championprovider.ucsf.edu (accessed April 4, 2019).

helping to prevent chronic disease, including diabetes and diseases of the oral cavity.6

Schillinger concluded that public health literacy must be part of the integration equation, because access to care is helpful but insufficient. Finding the second-hand smoke equivalent that moved the public to think differently about how to respond to tobacco-related epidemic will be important for preventing interrelated physical and oral health problems. Making a public health literacy case for integration may require making the economic case related to the costs of not doing things differently. “How does it affect every American’s pocketbook, either in their taxes, their insurance premiums, or their out-of-pocket expenses?” he asked. “We need to bring public health back into the equation.”

HOW ORAL HEALTH LITERACY SHAPES POLICY MAKING

“No family should be held back from their dreams because of dental disease,” said Meg Booth, executive director of the Children’s Dental Health Project, a nonprofit organization in Washington, DC, that is based on that premise. “We work each and every day to advance innovative policy solutions so that systems changes can remove oral health as a driver of inequities.”

The project works in three broad domains. It seeks to integrate oral health into the existing systems where families live, learn, and work. It seeks to remove race, income, and geography as drivers of oral health. And it seeks to make health and quality of life rather than disease burden the metrics of oral health care.

As a consumer advocate, the Children’s Dental Health Project represents the interests of families rather than industry. It works with policy makers at the state and federal levels on policies that affect oral health, and in the course of that work it has come to recognize the deficiencies in how oral health advocates have talked to policy makers. In the past, they have tended to highlight the prevalence of disease, not the consequences. They have focused on utilization data, not the effectiveness or appropriateness of care. And they have rarely cited the links between oral health and the social determinants of health, including food insecurity, trauma, housing, and insurance.

“We started to ask ourselves, ‘What is it that they really want to know?’” said Booth. In 2017, the project hosted a national focus group of influential community leaders, including pediatricians and state legislators, state advocates, and hospital administrators, to talk about oral health.

___________________

6 More information about the program is available at http://eatsfvoucher.org (accessed April 4, 2019).

That conversation and other research uncovered a fundamental lack of oral health literacy not only among community policy makers but also among those who are influencing policy makers. Advocates and policy makers alike know relatively little about not only the disease burden but about the impact that poor oral health has on their communities.

Digging deeper, the project traveled in 2018 to four communities in Maine and Texas to talk with influential members of those communities, such as educators, business owners, and medical professionals. These conversations revealed that policy makers and influencers tended to overlook oral health as a system issue and viewed it instead as something that is addressed in dental offices. Most were frustrated by the wall separating medical from dental coverage and care. They also believed that the consequences of poor oral health made a more persuasive case than did disease prevalence. “Most [policy makers] … don’t understand that this is a chronic disease that has to be treated on an ongoing basis,” said a member of one focus group. We “need to make the case better about not only health care costs but the cost [of dental disease] to society,” said another. “I don’t think dental care is often talked about as a chronic disease. I mean, that is a very strong word,” was a third representative remark.

On the need for risk assessments, one focus group participant said, “Isn’t prevention always the better tool? How many times are we learning that lesson?” Another, referring to the interest of state legislators in job creation, remarked, “So, if you were to say, ‘these guys can’t get a job because their teeth are holding them back,’ that’s going to make a big difference.” A third remarked with astonishment, “Is this true about the soldiers not being deployable? Wow.” People who are concerned about oral health have delivered these messages in the past, said Booth, but they appear not to have been resonating at the community level.

Booth pointed out that the impacts of oral health are felt across the life span in such areas as social function, education, economic mobility, employment, and overall health. The Children’s Dental Health Project has used these impacts to craft messages about the consequences of oral health. The appearance of the mouth and teeth can impact confidence and mental state, the project points out. Booth added:

Working mothers with better oral health earn 4.5 percent higher wages—a statistic made even more salient since more than half of women are the sole or primary breadwinners of their families, including 70 percent of African American women. Children sitting in a classroom in pain have a harder time learning, and dental disease has consequences for longer-term education and employment. Children with poor dental health are three times more likely to miss school and more likely to earn lower grades. Some research links gum disease with adverse birth outcomes. The comorbidities

of oral health, including diabetes and pneumonia in older adults, along with quality of life issues and long-term health costs are all considerations.

The separation of the payment systems for dental care and medical care restricts the ability to look at the impact and the incentives for integration of oral health and primary care, Booth observed. For example, about 80 percent of children in Medicaid below the age of 3 get a well-child visit, but only 20 percent get a dental visit for preventive services. She added that even though fluoride varnish is reimbursed by Medicaid programs in every state, and even though policies are in place to assess children for risk, only about 10 percent of children in the Medicaid program ages 1 and 2 get any type of preventive service from a nondental professional. The rigidity of the dental care system—with its 6-month visit and fairly rigid service limits, separate financing and delivery, separate electronic records, and reimbursement that emphasizes treatment—can be limiting, Booth said. “We are hamstringing ourselves.”

CREATING A PATHWAY TO SOLUTIONS

Booth cited three examples of “low-hanging fruit” for clinical integration: oral health risk assessment, care coordination, and benefit design. Higher reach opportunities for systems integration, which are “more daunting,” she said, include measurement, payment for health outcomes, and electronic health records. “Without the ability to track across the systems, we are always going to have an uphill battle.”

The barriers can quickly become overwhelming for policy makers unless they have a clear path in front of them. Advocates need to take the time to talk with partners outside health care systems to make a broader case for systems change, she said. Booth also noted that primary care is increasingly addressing the social determinants of health beyond a clinical setting. Professionals should ask how oral health literacy can be built into (not outside of) that conversation, she said. How can high-impact, minimally invasive interventions be provided in settings where people live, work, learn, and play?

Booth concluded, “Oral health is intended to be a means to health—an opportunity and not an end point. We need to focus on how we might bring oral health into systems and touchpoints that exist for families and children beyond clinical settings, whether it is early childhood education, social programs, job readiness programs.”

ORGANIZING A PUBLIC HEALTH LITERACY CAMPAIGN

When asked by Horowitz about how health literacy can address disparities in both access to care and health outcomes, Booth replied that this is the case that needs to be made when talking with policy makers. Rather than talking just about the prevalence of disease, the emphasis needs to be on how oral health has created larger disparities in such areas as economic mobility. “What are the driving forces behind that? Is it how we teach? Is it how we pay for care? There are different ways that we can address the issue to point out oral health as part of a larger system instead of just focusing on the disease burden.”

By talking about the consequences of oral health, Schillinger added, advocates also benefit people concerned about diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and other conditions. “It is a win-win,” he said. “You are getting a lot of constituent buy-in and are engaging more advocacy organizations by working on this in this way.”

Booth recalled having a conversation with a state advocate about an oral health policy where the advocate was very focused on what could be accomplished. “You can accomplish more,” she replied. “You should push the envelope.” Dentists are clearly allies, but so are members of the early childhood community, brain researchers, and other groups. “You need to start rallying the troops,” she said.

Showing state legislators that the 0-to-3 brain science people are on board with dental benefits in a different way for young kids is a more powerful tool than walking in just with the dental society and with an oral health advocate. Getting people to start thinking about who else is impacted by the policy change you are trying to seek is going to be more fruitful moving forward.

She also described a recent Medicaid waiver that went through for adults in Kentucky with work requirements and other features that would act to restrict access to all health services. The waiver was designed to free up funds for, as Booth described it, vision services, dental services, over-the-counter medications, and gym memberships. “So, at this point in time, oral health services are equal to a gym membership in the eyes of many policy makers. And while I think a gym membership is great, I am not sure that it falls under the same category as trying to control diabetes.” Yet, undervaluing oral health is a consequence of keeping dental services siloed from the rest of the health system, she said.

In response to another question from Horowitz about how to encourage the conduct of studies on the impact of health literacy on integration, Schillinger discussed several research gaps. One pressing need is to get a handle on the potential costs and potential benefits of integration, which

could be done with modeling studies. As an example, he cited a current evaluation of the impact of the soda taxes in Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco compared with Los Angeles, which is not taxed, to estimate how changes in consumption affect a range of diabetes outcomes. Of note, this study does not include oral health problems and costs. A similar study to determine the costs and benefits of public health interventions that impact common shared risk factors could make a powerful case to policy makers about the benefits of integration.

He also recommended research on how messages are communicated to stakeholders, including the general public and policy makers, on integration. People still do not understand that oral disease is a chronic disease with serious consequences. What words resonate with different audiences, he asked: cavities, gum disease, tooth loss?

Greater communication could also spur major changes in the clinical domain. For example, people should be coming into dental offices and asking for fluoride varnish, he said. He recalled a recent encounter with a patient with heart disease and diabetes who asked, “Aren’t you going to put me on a statin?” which reflected an “amazing” level of knowledge about her condition. Greater communication could “activate the general public around fluoride varnish as a basic health care right,” he said.

Another issue that brings public health and clinical care together is fluoridated water, Schillinger observed. Today, a countercultural movement has grown up around fear of fluoride—one best-selling toothpaste brand displays prominently on its packaging that it is fluoride free.

How do we, in clinical settings and in public health campaigns, talk about fluoride in a different way, [without being] seen as the mouthpieces of “the nanny state?” We should be telling our patients who insist on drinking bottled water which of the bottled waters have fluoride in them. We should be encouraging them to drink tap water. And we need to figure out how to best communicate to low-income populations, who have real fear around drinking tap water, often for really good reasons.

An even more fundamental problem is related to where people can get treatment for the consequences of oral disease. If patients with diabetes have no place to get oral health treatment, diagnosing their problems is not sufficient. Access to care remains “a huge barrier,” he said.

WHERE SHOULD ORAL HEALTH BE DELIVERED?

Roundtable member Michael McKee, assistant professor of family medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School, noted how useful it is to get an overview of the influences of oral health on general health.

However, much of the focus had been on relying on primary care physicians to deliver oral health, he said, and “we are, right now, overwhelmed, we are overtasked.” Dentistry is a “rather affluent profession, and primary care providers make a lot less than dentists do,” he said, adding that he was “struggling with this business model.” For instance, his clinic is an avid proponent of fluoride varnish and is doing the procedures. But “it is not easy to incorporate it into our daily practice,” he said. “We are reimbursed roughly $8 to $10 for doing this varnish, which is on top of everything that we do. We are averaging five or six clinical problems and then we have this varnish expectation,” with even the dental school approaching primary care physicians to address the gaps that exist.

McKee challenged dentists to “own up and address these gaps in oral health.” Rather than expecting primary care physicians to do more and more to address health disparities, clinical care delivery needs to be assumed by dentistry as well. “We need to get them at the places where there are gaps…. We need to also be realistic about the expectations and where the burdens are and make sure that they are shared and fairly distributed.”

Booth began her response by recognizing the amount of work that happens in a pediatrician’s office—“even when I just witness my own children going to the pediatrician.” She then made two points. First, ways need to be found to reimburse primary care settings adequately to create time and space for such procedures because pediatricians have a natural ability to do them, “probably more so than a dentist.” Pediatricians are already aware of the common risk factors that their patients face, but the current system is inadequate to address those risk factors.

The second point she made is that clinical providers are not needed to address one of the greatest unmet needs, which is identifying children at highest risk for caries and getting them into a management protocol. Families of children at even the youngest ages can be reached in many different ways in order to conduct an oral health risk assessment. Many people who see families every day have a sense of the risks facing those families, and these people could be trusted intermediaries who can get information from and to families. “Kids are not in physicians’ offices every day,” she said. “They are in child care settings. They are in [Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)] clinics. They are in many different places that could serve as the entry point into whatever a management protocol would be.” This would be a better option than relying on the handful of clinicians that families see on only an occasional basis.

Schillinger, too, said that “as a primary care doctor, I completely validate what you are saying.” Furthermore, relying entirely on primary care physicians is inadequate not just for oral health but for other areas of health care, such as mental health. “The individual doc model does not work,” he said. “We have to move to team-based care.” Payment mechanisms are

needed to do that, he observed, as are other health professionals who have the necessary skills. “We are not talking about drilling and root canals in primary care. We are talking about things like behavioral health integration.” He now has a behaviorist in his clinic, and the change has been “amazing,” he said. “Now I have expectations around behavioral health that I did not have before.”

FOSTERING PREVENTIVE INTERVENTIONS

In response to a question about how fluoride varnish applications can be more widely used, Booth described the situation in California as the best example. Almost anyone in California can apply varnish without worrying about credentialing issues. Companies can mail varnish to adults who want to do it themselves, and applying varnish is not a difficult thing to do, she said. Susan Fisher-Owens, clinical professor of pediatrics in the UCSF School of Medicine and associate clinical professor of preventive and restorative dental sciences in the UCSF School of Dentistry, who served as a moderator later in the workshop, elaborated that California is working on initiatives that would take varnish to children in different ways, such as through WIC and Head Start sites. They are also training different professionals, such as teachers, to apply fluoride varnish. “The skill itself is simple,” she said. “I taught my 5-year-old to do it. So now when I train other providers, I say, ‘If you have the skills of a 5-year-old, you too can do this application which can be a major benefit to our children.’” Furthermore, varnish can be applied multiple times without causing problems. In California, it is covered three times per year in medical care and twice per year in dental care, and additional treatments do not cause any sign of problems such as fluorosis. Fisher-Owens mentioned “a hypothetical risk of the allergy to colophony, which is part of the resin.” But her medical practice has done the treatment more than 10,000 times and has never had a problem. Questions remain about reimbursement, because now the treatments are being covered in pilot projects, but efforts are under way to integrate it into federally qualified health center billing.

Jennifer Dillaha, medical director for immunizations and medical advisor for health literacy and communication at the Arkansas Department of Health, asked about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations as a primary prevention for oral cancer. If immunization could be integrated into medical care, providers could write a prescription, and the pharmacist would fill it and provide the immunization. Furthermore, health literacy is a major consideration because dentists need to be able to communicate with patients about the HPV vaccination, just as any other health care provider would be able to communicate about vaccination.

Schillinger responded that he had diagnosed a young man with cancer of the base of the tongue, stemming from HPV, just 2 weeks earlier. “Pri-

mary care providers do not know about this problem,” even though it is a major cause of head and neck cancer. “Maybe they know about Michael Douglas’s cancer, and that is an opportunity. But we need to improve health literacy simply around this collateral benefit…. If we are focusing on health literacy to make the link that the same virus that causes cervical cancer is causing head and neck cancer, oral cancers, it would be a very big accomplishment.”

Jane Grover, director of the Council on Access Prevention and Interprofessional Relations at the American Dental Association (ADA), noted that the ADA has a policy on HPV education and has enthusiastically supported application of topical fluoride varnish in a variety of settings. “We applaud the opportunity to work with physician colleagues and promote oral health and prevention of disease.” She noted that before coming to the ADA she was at a community health center for 12 years, and such centers act as living laboratories and networks for medical–dental integration. For example, a community dental health coordinator program developed out of community health centers and is spreading across the country.

Gayle Mathe, director of community health policy and programs at the California Dental Association, noted that the dental association in California has been working for years to advocate with policy makers for more oral health research. She also noted that many stakeholders came together to advocate for the tobacco tax instituted in 2016 that is now funding activities in the state Office of Oral Health, including the establishment of “an oral health public infrastructure that never existed in California.” Much of that funding is going to local health departments to do on-the-ground work. This success was the product of an interprofessional and cross-cultural group of advocates, and it is being closely watched to determine its effects.

Suzanne Bakken, alumni professor of nursing and professor of biomedical informatics at Columbia University, asked about the extent to which oral health has been integrated into the All of Us initiative, which is doing broad data collection on all types of health issues.7 Workshop participant Martha Somerman, director of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, said that the institute was involved in the early stages of compiling survey questions. As the survey was narrowed, the questions on oral health were reduced, but the current version of the survey does contain questions about oral health. Schillinger asked whether biological samples would be gathered as part of the project, and Somerman responded that blood is still the principal biological sample, but with young children, for whom blood draws are more difficult, salivary samples are planned.

___________________

7 More information on the All of Us research program is available at https://allofus.nih.gov (accessed April 4, 2019).

In response to a comment about how to encourage people to engage in preventive activities that are not necessarily pleasurable, Booth made the point that dentistry has changed over the years. Practices have evolved so that dentistry is no longer painful or intimidating for children. They “watch videos. There are fish. There is a cool dentist there. Awesome things happen.” When children begin going to the dentist early and get used to having people probing in their mouths, they are not fearful.

Nicole Holland, assistant professor and director of health communication, education, and promotion at the Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, closed the discussion by pointing to the many research opportunities that exist, not only with respect to the messages that are conveyed but the messengers who convey those messages and how they are interpreted by and influence different audiences. As Horowitz concluded, “Research funding is what we need.”