5

Exploring Pathways to Integration1

The third session of the workshop was on pathways for integrating oral health into systemic health. Research has shown that preventive oral health services save money over the course of a childhood, observed moderator Susan Fisher-Owens, clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), School of Medicine, and clinical professor of preventive and restorative dental sciences in the UCSF School of Dentistry. But these preventive oral health services can take many different forms. The speakers in the panel she moderated, which featured a variety of oral health programs, were among those who had “caught the integration bug,” Fisher-Owens said. She encouraged the workshop participants to spread it to others. “We want to spread this ‘infection’ throughout our colleagues so we can work together. It’s a positive epidemic.”

A FEDERAL INFRASTRUCTURE

The federal government has an opportunity to serve as an infrastructure for integration, said Renée Joskow, chief dental officer for the Health

___________________

1 This chapter is based on presentations by Renée Joskow, chief dental officer for the Health Resources and Services Administration; Amit Acharya, executive director of the Research Institute at the Marshfield Clinic Health System and chief dental informatics officer for the Family Health Center of Marshfield Inc.; John Snyder, executive dental director and chief executive officer of Permanente Dental Associates; and Kelly Close, early childhood oral health coordinator for the Oral Health Section of the North Carolina Division of Public Health. Their statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Such an infrastructure can allow for integration to occur along many pathways, creating a continuum for moving forward based on the past.

The concepts of both integration and health literacy are not new, Joskow noted. In the 1800s, dentistry was a specialty of medicine, and some physicians taught it that way. But other medical school faculties did not agree with this approach, which contributed to the separation between dental education and general health care that exists today.

Taking “a 30,000-foot view,” Joskow discussed the Oral Health Strategic Framework of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS, 2014a). The report was the product of the U.S. Public Health Service’s Oral Health Coordinating Committee (OHCC), which consisted of representatives from HHS and other federal agencies. The HHS operating and staff divisions that contributed to the framework were the Administration for Community Living, the Administration for Children and Families, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Food and Drug Administration, HRSA, the Indian Health Service, the National Institutes of Health, the Office for Civil Rights, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, the Office of Minority Health, the Office on Women’s Health, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Other contributing federal agencies included the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Health Service Corps, and the U.S. Coast Guard.

The report established five overarching goals:

- Integrate oral health and primary health care.

- Prevent disease and promote oral health.

- Increase access to oral health care and eliminate disparities.

- Increase the dissemination of oral health information and improve health literacy.

- Advance oral health in public policy and research.

Joskow focused her remarks on two of those goals: integrating oral health and primary care, and increasing the dissemination of oral health information and improving health literacy. The report established four strategies for achieving the first goal:

- Advance interprofessional collaborative practice and bidirectional sharing of clinical information to improve overall health outcomes.

- Promote education and training to increase knowledge, attitudes, and skills that demonstrate proficiency and competency in oral health among primary care providers.

- Support the development of policies and practices to reconnect the mouth and the body and inform decision making across all HHS programs and activities.

- Create programs and support innovation using a systems change approach that facilitates a unified patient-centered health home.

In turn, these strategies can be linked to recommendations from two Institute of Medicine2 (IOM) reports on oral health (IOM, 2011a,b), which also recommended integrating oral health and primary care. People studying this issue should “not forget about all the good work and the important … documents and workshops like this one that have come before.”

Joskow directed attention to the first of these four strategies, as she has been heavily involved in efforts aimed at the bidirectional sharing of clinical information to improve health outcomes. “It’s not taking oral health and dropping it into a medical environment,” she said. “We need to practice what we preach. We need to embody the principles of integration. We need to be discussing the issues and working with these issues as integrated teams.”

With regard to the fourth of the five goals, on disseminating oral health information and improving health literacy, she cited five strategies from the report:

- Enhance data value by making data easier to access and use for public health decision making through the development of standardized oral health measures and advancement of surveillance.

- Improve the oral health literacy of health professionals through use of evidence-based methods.

- Improve the oral health literacy of patients and families by developing and promoting clear and consistent oral health messaging to health care providers and the public.

- Assess the health literacy environment of patient care settings.

- Integrate dental, medical, and behavioral health information into electronic health records.

The OHCC report contained many examples and objectives from the participating federal agencies. For example, on the fourth goal, the Administration for Community Living, which includes the Administration on Aging, proposed to undertake an oral health literacy and education effort

___________________

2 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM name is used to refer to publications issued prior to July 2015.

directed toward older adults, caregivers, communities, and health professionals. Educational materials developed within the initiative, which provides evidence-based health messaging driven by the needs identified for older adults, is available on the HRSA Oral Health webpage in addition to the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research webpage.3

ACTIVITIES WITHIN HRSA

Integration has been a bedrock of HRSA’s activities over many years, said Joskow. She presented the five strategic goals for the agency:

- Improve access to quality health care and services.

- Strengthen the health workforce.

- Build healthy communities.

- Improve health equity.

- Strengthen HRSA program management and operations.

All of these goals are related to integrating oral health and primary care. For example, Joskow mentioned a contract between HRSA and the American Academy of Pediatrics to develop a curriculum for learning about oral health integration in primary care practices for children.4 She also described work at the practice interface of interprofessional education, in which HRSA served as a convener and a provider of infrastructure.

Joskow said that HRSA, responding to recommendations in the two 2011 IOM reports, worked to develop interprofessional oral health core clinical competencies for safety net settings in three phases: competency development, systems approach and analysis, and implementation strategies. The competencies had five major domains: risk assessment, oral health evaluation, preventive interventions, communication and education, and interprofessional collaborative practice. A particularly important step has been implementation, in which three most-influential systems have risen to the fore: the health care system, the financing system, and professional associations—all within the overarching context of communication. For example, one of the recommendations of the report Integration of Oral Health and Primary Care Practice was to “develop infrastructure that is interoperable, accessible across clinical settings, and enhances adoption of the oral health core clinical competencies” (HHS, 2014b). Under this recommendation, the following actions were recommended:

___________________

3 The page is available at https://www.hrsa.gov/oral-health (accessed April 4, 2019).

4 The curriculum is available at https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/oralhealth/oralhealthprimarychildren.pdf (accessed April 4, 2019).

- Engage and educate consumers about oral health in primary care as an expected standard of interprofessional practice.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of the application of the oral health core clinical competencies by assessing patient satisfaction and health outcomes.

“It’s the public who we’re interfacing with, whether it’s at a community or individual level,” Joskow observed. Patients may be surprised when a primary care provider asks them whether their gums have been bleeding or if they have problems chewing. But such questions are an opportunity, as a colleague of Joskow’s has put it, “to teach them that their mouth is connected” to the rest of their body.

Joskow also called attention to the recommendation about developing an interoperable and accessible system. Payment modifications and incentives will be a major part of meeting this recommendation, which in turn points to the critical importance of building partnerships and coalitions to educate policy makers. “They’re an important part of the team,” she said.

HRSA has been continuing to invest in this area. Joskow mentioned three projects it has been funding. One is testing the competencies in health centers through a pilot program with the National Network for Oral Health Access, which has resulted in a user guide for implementation of the interprofessional oral health core clinical competencies (NNOHA, 2015). From the pilot-testing level, this initiative has progressed to demonstration projects in health centers and to the state level through funding to the National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center.

HRSA has also been striving to disseminate the results of its work in a culturally competent way. As part of this effort, it provides materials designed to enable health care providers to recognize and address the unique culture, language, and literacy of diverse consumers and communities.5 More broadly at HHS, the Office of Minority Health has developed a curriculum on cultural competency that provides continuing education credits, including a curriculum for oral health providers.6

Joskow noted that HRSA addresses oral health, access to care, and health workforce education in a multitude of programs and activities across the agency. As an indication of the breadth of its concern, Joskow pointed to some of the advisory committees that serve HRSA in ways connected to oral health. The Advisory Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry, which has produced a series of reports related to integra-

___________________

5 More information about these materials is available at https://www.hrsa.gov/cultural-competence (accessed April 4, 2019).

6 More information about these programs is available at https://www.thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov (accessed April 4, 2019).

tion, and the Advisory Committee on Interdisciplinary Community-Based Linkages are among the groups that provide the Secretary of HHS with advice related to integration.7 In addition, HRSA has conducted webinars on topics related to integration, including a webinar on integrating oral health and behavioral health in primary care settings.

“We need to build upon what currently exists,” Joskow concluded.

We have to be connecting all professions and caregivers, communities, and individuals to ensure that we employ appropriately crafted messages and we move toward fully integrated models of care, and not keep reinventing the wheel. Our health and that of the communities we serve and those in those communities where we live all depend upon it.

DRIVING INTEGRATION THROUGH COMBINED ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS

Amit Acharya, executive director of the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute at the Marshfield Clinic Health System and chief dental informatics officer for the Family Health Center of Marshfield, said that he is a clinician who has been infected by the passion to integrate medical and dental care and to use the results of research to improve clinical care.

The Marshfield Clinic Health System is a large physician group practice of more than 1,000 providers that started in 1916. It has 55 clinical locations in 34 communities in central Wisconsin, including 10 dental clinics. It serves more than 300,000 unique patients and has about 3.5 million encounters annually. It is also a medical campus academic location for the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

One of its guiding principles has been to make sure that it provides all types of medical specialties to the people it serves. As part of that principle, it has sought to operationalize the Surgeon General’s pronouncement that oral health is essential to general health and well-being (HHS, 2000). A key priority, in addition to regionalizing care and eliminating health disparities, has been to foster medical–dental collaboration through a combined electronic health record with decision support capabilities.

In 2018, the 10 federally qualified health centers in the system provided dental services to more than 58,000 people from all of Wisconsin’s 72 counties, with about 165,000 unique patients being treated by family health center dental operations since the program began in 2002. Most of the 40 or so dentists in the centers are general dentists, with a similar number of

___________________

7 More information about these committees is available at https://www.hrsa.gov/about/organization/committees.html (accessed April 4, 2019).

dental hygienists and a larger number of support staff. At this point, the dental care system is close to full capacity, said Acharya.

In terms of health literacy, the system’s service area is fairly rural, with an older population and levels of uninsured care running at about 10 to 15 percent of patients. The literacy level is relatively low compared to other areas, which makes moving to preventive care more difficult.

Given the influence of oral health in a wide variety of diseases, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, obesity, adverse pregnancy outcomes, chronic kidney disease, and others, working with physician care teams is critical, Acharya said. “All of the health care professionals need to come together, because we need to look at this from the patient’s perspective.”

One immediate need was for better ways to exchange patients’ information among medical and dental providers. Almost 90 percent of the 165,000 patients seen in the system’s dental centers are the health system’s medical patients as well. Until 2010, medical and dental records were on separate systems that were not synchronized, which can compromise quality and safety through inconsistencies and discrepancies, said Acharya. Even though medical and dental providers often rely on the same information, it was largely the responsibility of patients to make sure that their medical and dental providers were well informed.

The Marshfield Clinic Health System has emphasized informatics for decades, with its first telehealth project occurring in the 1950s and various informatics initiatives starting in the 1960s. Continuing this tradition, the Integrated Medical-Dental Electronic Health Record went live in 2010. The new approach was based on research studies of what the system’s providers needed to deliver better care (Acharya et al., 2017). For example, when asked whether it was important for them to have access to dental information to provide effective medical care, 75 percent of family medicine providers said yes, followed by 64 percent of pediatricians and oncologists, 61 percent of urgent care providers, 60 percent of cardiologists, 46 percent of neurologists, and 44 percent of obstetrics/gynecology providers. When asked what dental information medical providers would like to access in a combined electronic health record, 62 percent said oral health status, followed by treatment plan (58 percent), dental problems list (56 percent), dental diagnosis (54 percent), dental history (46 percent), dental alerts (45 percent), dental appointments (30 percent), progress notes (29 percent), dental radiographs (13 percent), and odontograms (9 percent).

Integration of the two systems is still ongoing, said Acharya, but the goal is a seamless system. Indeed, he suggested not even using the word integration, because it suggests that two different things are being integrated.

Part of the system is a summary of oral health status and treatment for medical providers that lists, by the end of the day that a dental appoint-

ment occurred, who the dental provider was, the reason for the visit, the periodontal health status, and the treatment plan. Dentists, who are used to thinking in terms of the Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature (CDT), can be challenged to think in terms of dental diagnoses, but physicians are accustomed to looking at diagnoses, making it important to include that information in the integrated record (Shimpi et al., 2018). For their part, dentists have access to the same information that physicians see, including active medications, allergies, and problem lists.

Once a diagnosis is made and entered into the record, clicking on an information button leads to patient education materials. Acharya commented that this information has also proven useful to physicians who want to know more about how a dental condition is related to a patient’s systemic condition. Similarly, he added, appointments and prescribing are centralized, with an e-prescribing application available to both dentists and physicians. Even where dental patients are not medical patients, prescription information is reconciled and put into the integrated record. Finally, after-visit summaries that are made available to patients also go in the electronic record (Horowitz et al., 2014). As of the workshop, the health system had been able to provide an integrated electronic health record to more than 140,000 of its patients. Acharya particularly thanked Delta Dental of Wisconsin for its support in setting up the system.

USING AN INTEGRATED ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORD TO CHANGE PRACTICE

Acharya used the example of diabetes to demonstrate how the integrated record is being implemented. The record provides oral exam alerts for all diabetic patients, which are also useful as part of meaningful use. The exam can be done by physicians, dentists, or other providers. “It’s a care team approach. We don’t necessarily say who needs to do it, but as part of that team they take care of it for the patients.”

This information is in turn used to decide whether to make a referral for a patient. If the referral is internal, the department receiving the referral will follow up with the patient. If the referral is external, the system’s referral center will process the referral and ensure that the appointment is scheduled.

Screening for undiagnosed diabetes at the dental center results in alerts for blood glucose screening if patients meet certain criteria. Besides producing information that physicians can use, the screening process provides information for dental providers. A study of such screening found that it was easily implementable in a dental setting (Acharya et al., 2018). Alerts and referrals can even be generated using routinely collected dental data without a blood glucose measurement.

The integrated electronic health record is also a “gold mine” for research, said Acharya. It has produced a comprehensive data warehouse with about 10 million patient-years of data that can be used to support business and biomedical research queries. For example, the Marshfield Clinic Health System was involved in a physician group practice demonstration project under the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that has helped to save close to $100 million from coordinated treatment of chronic conditions. The availability of medical and dental data is now enabling several oral-systemic studies, which are contributing to further the quality improvement initiatives. And oral health data have been incorporated into provider dashboards to improve the quality of care.

Acharya recounted the experiences of a patient who was referred to a dental center by his Marshfield Clinic oncologist. His cancer treatments were negatively affecting his oral health status, and as a result he began losing weight. The patient was initially scheduled for an emergency visit and follow-up dental care. All of his teeth needed to be extracted, and he was fitted for dentures. To date, the patient has improved oral health and has gained 10 pounds.

Acharya also cited a dentist colleague who quoted a patient as saying, “I thought that it seemed dumb that you would take blood pressure at the dentist office, until I had a friend of mine come here and you guys took his blood pressure in hygiene and wouldn’t even see him. You sent him right over to the emergency room. Good thing you did. They took him into emergency surgery. I guess they said he was ready to pop.”

Though the challenges and opportunities are ongoing, diligence pays off, Acharya concluded.

Nicole Holland asked Acharya about what should be in electronic health records for dentists and physicians. Between 50 and 60 percent of the information in an electronic health record would be common to the records of both a dental and medical practice, answered Acharya, who had previously done a study of electronic and paper records for both dental care and medical care. He also mentioned, in response to a question from Holland, that providers in the Marshfield Clinic Health System have access to prescription histories and have been looking at retrospective data to examine past practices.

INTEGRATING ORAL HEALTH AND PRIMARY CARE AT KAISER PERMANENTE

The philosophy of Permanente Dental Associates (PDA) is that it will provide ethical, evidence-based, and integrated care, where integrated means considering the total health of its patients, said John Snyder, the organization’s executive dental director and chief executive officer.

On a more pragmatic level, PDA faced the challenge of integrating dentistry into the primary care setting, despite the fact that primary care physicians are incredibly busy. The approach that worked was to demonstrate that integrated dental care could help physicians do their jobs, including getting paid for their jobs.

PDA is part of a vertically integrated system, from an insurer to physicians to oral health providers. It has a contractual agreement with the broader group that provides a per member, per month global payment. It has 21 offices extending from Eugene, Oregon, to Longview, Washington; about 170 dentists; and about 287,000 patients. It provides both general and specialty care, emergency and urgent care, and Saturday appointments for dental cleanings at select locations.

PDA started taking blood pressure measurements and providing its patients with advice slips in the 1980s. In the 1990s it began doing passive referrals to health monitors, and in the 2000s it began closing preventive care gaps. As an example of this work, PDA has trained its dentists to do the first three As of tobacco cessation—ask whether patients smoke, advise them that smoking is bad for their teeth and gums, and assess whether they are thinking about quitting—after which patients can be urged to talk with tobacco cessation specialists.

Because most of PDA’s patients have both medical and dental insurance through Kaiser Permanente, the dentists have access to medical information that they can use to identify care gaps. In this way, oral health providers can act as extenders of primary care to improve health outcomes while also learning more about approaches that have proven effective in medicine, such as value-based reimbursement, care teams, and medical homes. The care gap reports are written in a patient-friendly manner so that patients can understand exactly what their provider is recommending. “I teased the dentists in our group. I said, ‘If you want to be called doctor, you better engage in the health care system,’” Snyder recounted.

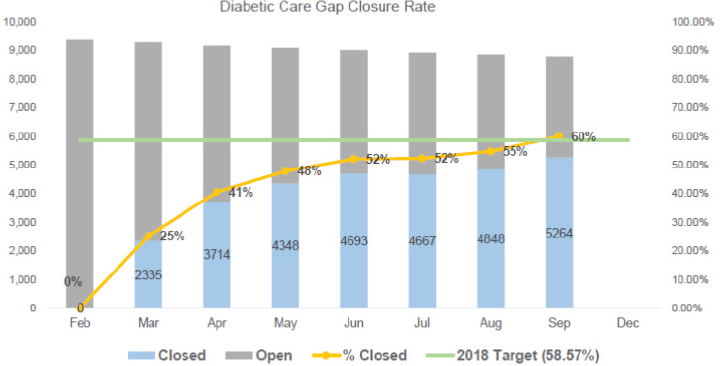

As a measure of success in closing these care gaps, Snyder pointed to the approximately 9,000 patients with diabetes under PDA’s care. Over the course of 2018, PDA closed care gaps for 60 percent of the patients in terms of having them get vision tests, urinalyses, and hemoglobin A1C screening (see Figure 5-1). Among those with a recent dental-only visit, 65 percent had their care gaps closed. “Our whole education is based on preventing disease, so we can be really good at it,” said Snyder.

At the end of 2016, PDA went live with a fully integrated electronic health records system that has interfaces to dental care, pharmacy, social workers, care managers, and other parts of the health care system. It has been a “huge game changer,” said Snyder; “we don’t even know the full capability” of the system. It provides best practice advisories that require some sort of action, such as acknowledging that action has been taken.

SOURCE: As presented by John Snyder at the workshop Integrating Oral and General Health Through Health Literacy Practices on December 6, 2018.

That information populates a provider’s record, making it possible to determine who is engaging with the system and advancing integration. The system has also helped reimagine care teams by making it possible to collaborate and talk across divides so that providers share responsibility for a member’s total health.

Also in 2016, the health care system opened its first dental and medical office that combined medical care with general dentistry and pediatric dentistry. In other cases, dental and medical care were co-located, but the combined office has a higher rate of addressing preventive gaps than at offices that are simply adjacent. Patients are 110 percent more likely to receive the child flu immunization, 81 percent more likely to receive the child human papillomavirus vaccination, 114 percent more likely to receive an adult physical, and 160 percent more likely to receive a cervical cancer screening. “That’s part of the cultural transformation that changes when you get adjacency and interprofessional interactions,” said Snyder, “amazing results.”

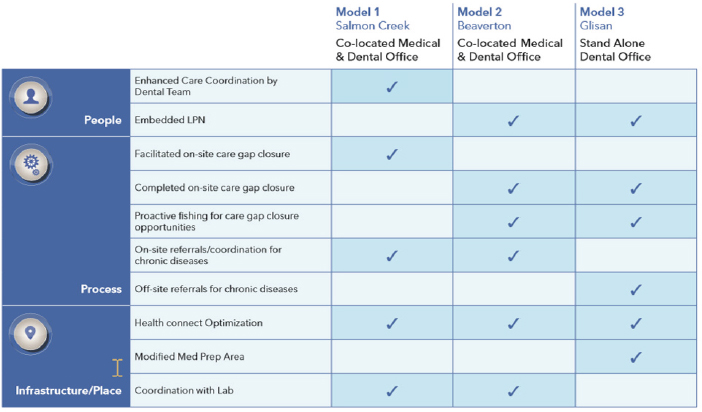

The health care system is now testing three models of dental care that feature different combinations of people, processes, and infrastructure. For example, in the models with licensed practical nurses embedded in a dental setting, dental patients can quickly and easily have their blood drawn or receive an immunization (see Figure 5-2). “We’re looking for the most affordable models, but also to gain the most efficiency and improve outcomes,” Snyder said. As another example of improved integration, Snyder

NOTE: LPN = licensed practical nurse.

SOURCE: As presented by John Snyder at the workshop Integrating Oral and General Health Through Health Literacy Practices on December 6, 2018.

mentioned the new ability to identify people over the age of 65 who did not receive an influenza vaccine the previous year. This information can go to a dental clinic in an effort to encourage vulnerable patients to get vaccinated. “If I prevent one of those people from not having inpatient services associated with an influenza respiratory infection,” Snyder pointed out, “I paid for that whole day, every vaccine and then some.” The system is even able to identify people in the waiting room who are not scheduled for a treatment and pull them into the clinic to fill care gaps.

With value-based compensation, financial returns depend on the individual performance of the overall dental office in terms of patient experiences and integrated care. Furthermore, with a global payment, oral health providers, as a professional group, have the best understanding of what they value and how the health of patients should be measured. Patients appreciate the convenience as much or more as they do better outcomes, saying things like, “I don’t have to drive here again. I can get my flu shot, get all this done.”

Measures of improved patient satisfaction and care also benefit oral health providers, who are paid more under their contracts for improving overall care. Furthermore, providing integrated medical and dental care has established a new standard for high-quality, convenient, and afford-

able health care. Providers take a shared responsibility for their patients’ total health and wellness, and meeting the needs of members is easier because bridges have been built between departments. “All those things are fundamental and essential elements if you truly want to integrate care—and it’s fun,” Snyder concluded.

DELIVERING PREVENTIVE ORAL HEALTH SERVICES

Into the Mouths of Babes (IMB), which is one of the programs highlighted in the commissioned paper (see Chapter 2), had three goals when it began in the year 2000, observed Kelly Close, early childhood oral health coordinator for the Oral Health Section of the North Carolina Division of Public Health. The first was to increase access to preventive oral health services for low-income children ages 0 to 3. The second was to reduce the prevalence of early childhood caries. The third was to reduce the burden of treatment needs on an inadequate and stretched dental workforce in North Carolina. The state had already identified an early childhood caries crisis and had done a small pilot program in the western part of North Carolina from 1998 to 2000, which became IMB.

When the program went statewide, it had six partners: the North Carolina Academy of Family Physicians, North Carolina Medicaid, the North Carolina Oral Health Section, the North Carolina Pediatric Society, the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, and the University of North Carolina School of Dentistry. Each of these six organizations had an active role and was invested in the program, said Close. The medical organizations negotiated the reimbursement rates with Medicaid. The Oral Health Section and the School of Dentistry worked together to develop training for physicians. The School of Public Health worked to develop the evaluation for the program. The program, which was initially funded by grants, hired Close as a coordinator and paid her salary.

Close agreed with earlier presenters that primary care providers have limited time and resources in offering and providing oral health care to patients, and this barrier has increased over time in North Carolina. Furthermore, dentists could not take on this responsibility for young children, because many parents do not take their children to the dentist by age 1 or even by age 2 (though more do now than in the past, Close added). As a result, the members of the original partnership realized that they needed to offer preventive oral health services where children could be reached, which was in the offices of the family physicians, pediatricians, and local health departments where children were going to get immunizations.

Preventive oral health services include more than just fluoride varnish, Close remarked. These services include an oral evaluation, risk assessment,

varnish application, parent counseling, and a dental referral if the dental workforce is adequate. This referral should occur by age 1, she said. If that is not possible, a priority oral health risk assessment and referral tool is available to refer children based on their risk.

Research has shown that physicians, and particularly pediatricians, tend to view dentists as specialists. They are trained to treat whatever they can in their offices, and when they cannot treat something they make a referral. Therefore, when children have high-risk behaviors for caries, including diet, types of behaviors, and habits, they counsel parents about changing those risk behaviors rather than referring to a dentist based on the risk factors. “Of course they’re great about referring if there’s disease present,” said Close. “But I do think there would need to be a mind shift in how they view dentists as a general provider and practitioner, as we have talked about earlier today. I know that dentists see themselves, at least general dentistry, as primary care. But I can’t say that that’s true across the board for medicine.”

When North Carolina Medicaid reimburses for preventive oral health services, which is approximately $50 when the service is done, two codes are billed. The D0145 code is an oral evaluation for patients under age 3, though North Carolina reimburses for this evaluation up to age 3 and a half. The D1206 code is for fluoride varnish. A provider can do this procedure a maximum of six times for a child from tooth eruption to age 3 and a half with a minimum interval between procedures of 60 days, a time limit designed so as not to interfere with well-child visits, which can be spaced less than 90 days apart. Preventive oral health services can be provided at well-child visits, sick visits, or separately scheduled visits, and both medical and dental providers can be reimbursed for preventive services.

The number of annual visits under the program grew to approximately 170,000 in 2017. In 2016, 57.8 percent of the approximately 47,000 quarterly well-child visits for 1- and 2-year-olds included preventive oral health services. “We have room for improvement,” Close said of these numbers. At the same time, other community programs support preventive oral health services. For example, in North Carolina communities with Early Head Start programs, parents report that about 80 percent of young children received preventive oral health services by a dentist or nondental medical provider by age 3, which is a higher rate than for children on Medicaid but not enrolled in Early Head Start in those communities (Burgette et al., 2018).

Close briefly described three studies of program outcomes, which are among about 50 evaluation and outcomes articles on IMB. Kranz and colleagues (2014) showed that setting and provider type do not influence the effectiveness of the preventive oral health services on children’s overall oral health. Kranz and colleagues (2015) found that children making four or

more IMB visits before age 3 show a 17.7 percent reduction in tooth decay, compared with children making 0 visits. And Achembong and colleagues (2014) showed that the program has contributed to a statewide decline in decay rates since 2004 and has helped reduce the gap in tooth decay between children from low- and other-income families at the community level.

Close also called attention to the 2014 recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that oral fluoride supplementation start at age 6 months for children whose water supply is deficient and that fluoride varnish be applied to the primary teeth of all children starting at tooth eruption (Moyer, 2014). The task force has concluded as well that evidence is insufficient for recommending routine screening examinations for dental caries, but the same was said for fluoride varnish in 2004, Close pointed out. “You researchers,” she said, “we need you to do some research on screening.”

Research has shown that parents express satisfaction with having preventive oral health services at primary care visits (Rozier et al., 2005), experience low health literacy demands by medical providers during oral health counseling (Kranz et al., 2013), and are more likely to take their child for a dental visit when referred by a medical provider (Beil and Rozier, 2010). Parents play “a huge role” in their children’s oral health, said Close, “and I feel that they’re overlooked.” Parents have many barriers to seeking preventive oral health services for their children, but common assumptions about what these barriers are may not be right. Close recommended the use of motivational interviewing as a patient-centered, evidence-based behavioral intervention (Borrelli et al., 2015). The use of the technique is associated with improvements in pediatric health behaviors and outcomes, and medical providers in North Carolina have opportunities to be trained in the technique. An e-learning training module for IMB scheduled for release a few months after this workshop features examples of parent counseling using this technique.8

Community integration remains critical, Close said, including not just medical and dental providers but public health programs, child care programs, and other settings. Everyone needs to be able to convey evidence-based messages using plain language. For example, fluoride toothpaste is, along with fluoride varnish, one of the top ways to prevent early childhood caries. The message that fluoride is still the most effective way to prevent tooth decay and that prevention is healthier and cheaper than treatment needs to be disseminated as widely and as clearly as possible, she said. Messages also need to be consistent. For example, the American Academy of

___________________

8 See the “Parent Education” section of https://publichealth.nc.gov/oralhealth/partners/IMBtoolkit.htm (accessed June 10, 2019) for more information about the online training modules.

Pediatrics and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry have differing recommendations about fluoride varnish, with the latter recommending it for high-risk children and the former recommending it for all children. “That’s conflicting,” she said. The website toothtalk.org provides colorful, short, and informative videos, articles, and other evidence-based information for early childhood caregivers, parents, health care providers, and others.

Once a child has a cavity in a baby tooth, that child is much more likely to have cavities in permanent teeth, and fixing those is much more expensive than taking preventive measures. “There’s a lot to be said for starting early with prevention and with children’s parents,” Close concluded.

EFFECTIVE REFERRALS

At the beginning of the discussion session, Fisher-Owens asked the panelists specifically about referral systems, noting that a referral can take many different forms, from writing on a piece of paper that a patient ought to see another provider to walking a patient to another office to be treated immediately. Close responded that she does not know what the most effective referral method is because IMB has not done research on that question. But “we do know that getting kids into the dentist early is important, even with medical providers doing preventive oral health services,” because children with dental treatment needs do not receive this care from medical providers. A pilot program in North Carolina has taught dentists to be comfortable around young children, which can improve rates of preventive dental care. Another initiative has urged medical practices to make referrals, but still only about 50 percent of children make a dental visit.

Medical providers have demonstrated some reluctance to add an oral health risk assessment tool to their already full well-child visits, she acknowledged, which is “a dilemma.” Doing a risk assessment in another venue is a possibility, though she is not sure where that venue would be. “I do know that, within a group of children, some are more at risk than others. And I think the evidence shows us that, for children at high risk, the early dental visit is important.”

Acharya responded that the best way of making referrals is the way that is easiest for patients. In recent years he has been trying to understand more about how medical practices handle oral health and dentistry, and one thing he has found is that medical providers can hesitate to tell their patients to see a dentist because of access and insurance issues. Some patients even come back to their medical providers after a dental referral and say that dentists were not able to see them.

He thought that the best model for making sure a referral takes place is co-located medical and dental care. When a dental practice is in the same place as a medical practice, medical providers have more assurance that

their patients will see a dentist, and vice versa. Clinical referral managers can also help ensure that referrals take place, as can team care that provides both dental and general health services.

Joskow shared some best practices for referrals that have emerged from pilot projects and demonstration projects. One is scheduling a follow-up appointment before the patient leaves the medical appointment. “Even if it meant the receptionist or the front desk person contacted the dental clinic or the dental provider, that seemed to be much more successful in a completed dental visit.” Warm handoffs in which care is transferred from one provider to another in front of a patient or a patient’s family member have also proven to be successful. In addition, care gaps, including oral health care gaps, can show up on physicians’ computer screens, so that two populations in particular, people with diabetes and children older than 1 year, are referred to dentists.

Patient navigators, case managers, and transportation facilitators can be aware of an individual’s, family’s, or community’s barriers to care and can facilitate referrals, Joskow continued. An “ingenious” approach has been to give patients some sort of cards or other signifiers and promising them that they will receive something when they arrive for a referral. Snyder recalled a similar experience in which patients with a care gap were given a card and told that when they presented it in another office they would automatically go to the front of the line. Actually, the system did not work exactly this way, Snyder admitted. Rather, when a patient was given a card, the provider called the other office and said that the patient was on the way. “That was the way to get them connected.” Snyder also observed that dentists are lucky to have hour-long visits with their patients, which makes it easier to forge connections. Hygienists are particularly good at this, he said. They can get to know a patient and urge the patient to get something done. “That personal touch really makes the difference,” Snyder said.

Referrals also work in the opposite direction, from dental providers to general health providers, and dentists are good at making these referrals, according to Acharya, because they can be very analytical in terms of closing health care gaps. When the Marshfield Clinic Health System instituted an initiative to make sure that all of its patients were receiving blood pressure screening, dentists were among the leaders in referring their patients into primary care, helping to raise the screening rate from 72 percent to close to 89 percent. “It’s a health system. It needs to be part and parcel of how we care for our patients.”

BEHAVIORAL HEALTH

Fisher-Owens also asked about the role of behavioral health in integration, citing Asian Health Services, a program in Oakland, California, that

introduced a behavioral health team into dental visits to provide behavioral health services.

Joskow mentioned a webinar on integrating oral health and behavioral health in primary care that targeted social workers and other behavioral health providers. Feedback received from dentists after the webinar was that they wanted a webinar specifically on how to incorporate behavioral health into a dental environment. For one thing, such training could help dentists cope with “dental phobics,” who can be very challenging for dental care providers, said Joskow.

INTERPROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

In response to a question about the best way to do interprofessional education, Close talked about the training done for IMB. It is certified for continuing medical education (CME) through the American Academy of Family Physicians with an American Medical Association equivalent. It is renewed every year, physicians get 1 hour of credit for attending the training, and Web-based training now in development will also have a CME component. However, she doubted that the credit is a major draw for those who take the training. She thought instead that providers are motivated to want to provide the services taught, especially because the services have come to be considered a standard of care in North Carolina.

Acharya noted that his organization works closely with primary care providers to make sure that a curriculum is made available to them. The course is not mandatory, and providers already have many training requirements, but the course is available and offers credit. Another training opportunity, he noted, is through grand rounds, where dental researchers or other dental providers have talked about medical–dental integration.

Integrating more content into medical training is a continuing challenge, he said, especially given the lack of time professionals have for such training. But he also predicted that greater patient literacy was going to produce a shift in the thinking of providers. As patients become more educated and ask their providers more questions, providers will need to be more responsive. An important question then becomes how to get patients the information they need given their preexisting levels of health literacy.

LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH

In response to a question from Fisher-Owens about the provision of health literacy information in languages other than English, Joskow observed that the federal government tries to provide information in other languages whenever it can. “We try to leverage whatever resources are already available. But we are cognizant of that and trying to work to expand that.”

At the same time, the need for languages other than English comes up in many different settings. Joskow described, for example, a recent health fair in which head and neck cancer screenings were involved. The health fair was done in a local mall with a very diverse population, and intake was done in five different languages. Referrals also had to be done in multiple languages, which was challenging.

On this point, Joskow described a colleague who begins some of her talks entirely in Spanish to demonstrate what it is like for people who do not speak English. “Her message is, ‘Now you understand how uncomfortable it can be if English is not your first language.’”

QUESTIONS FROM WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS

At the end of the discussion session, Fisher-Owens called for workshop participants to provide questions that could be addressed over the course of the day as well as by the panelists. The following questions were provided:

- Can the location of dental and medical practices cause legal problems due to differing regulatory regimes?

- How can oral health be brought into the community, including into unconventional settings such as barber shops and faith-based organizations?

- How can integration of oral and general health be coordinated with such programs as maternal and infant health programs and home visiting programs?

- How can behavioral change models be applied by providers to further integration?

- How can health literacy be used not only to inform integration but to drive it? For example, do patient portals offer a way for patients to understand the value of integrated systems and demand such systems?

This page intentionally left blank.