Proceedings of a Workshop

| IN BRIEF | |

|

May 2020 |

Reorienting Health Care and Business Sector Investment Priorities Toward Health and Well-Being

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

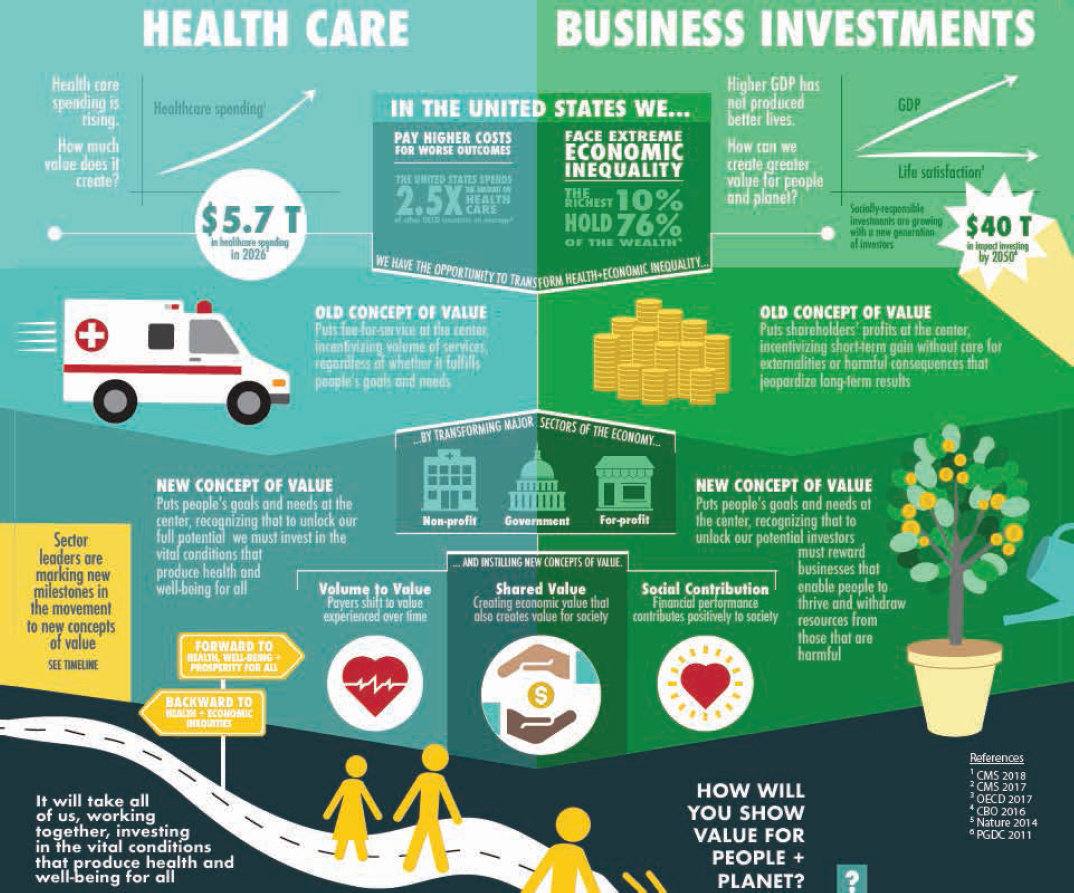

On December 3, 2018, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Roundtable on Population Health Improvement held a workshop on Reorienting Health Care and Business Sector Investment Priorities Toward Health and Well-Being in New York City at NYU Langone Health. The topic was selected based on prior roundtable discussions about how the flow of resources in the economy influences health outcomes. Roundtable members had also discussed how ideas concerning value realized from investment are changing, such as how a greater emphasis is being placed on value in health care (e.g., paying for outcomes rather than services) and on its rough analogs in other sectors. Sanne Magnan of HealthPartners Institute welcomed workshop attendees and opened the gathering with a quote from David Kindig’s Purchasing Population Health: Paying for Results: “population health improvement will not be achieved until appropriate financial incentives are designed for this outcome.” Magnan next referred participants to the commissioned infographic1 shared with attendees to provide some background for the topic of changing concepts of value and investment that would be discussed during the day (see Figure 1).

In his context-setting remarks, Bobby Milstein of ReThink Health observed that there is growing recognition that investing for results and value is worthwhile, and he described several shifts in the landscape that appear to confirm this. These shifts include a focus on value over volume in health care and an emphasis in the business sector on investments that do not merely return value to shareholders but are also good for employees, society, and the environment. Examples from the business sector were included in workshop background readings,2 with work from the Nonprofit Finance Fund, JUST Capital, and the Coalition for Inclusive Capitalism. Moreover, Milstein said, the U.S. Surgeon General’s report will articulate the relationship between health and the economy, adding that Surgeon General Jerome Adams would be sharing the framework for this work in his keynote address at the workshop. The workshop would also showcase examples of investments, investment priorities, partnerships (e.g., between investors and health care leaders or between businesses and health care leaders), and engagement with the community in the context of an explicit or implicit recognition of a sense of shared values (e.g., improved patient health or societal conditions, including building healthier places and expanding opportunities for employment). Milstein outlined the day’s agenda, which started with panels on the historical background and milestones in each of two spotlight sectors—health care and business—and proceeded to showcase select case examples offering a close-up view of how leadership opportunities have been seized in each sector.

__________________

1 See the Commissioned Graphic link under Meeting Materials at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/12-03-2018/reorienting-health-care-and-business-investment-priorities-toward-health-and-well-being-a-workshop (accessed March 20, 2020).

2 See the Readings and Resources link under Meeting Materials at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/12-03-2018/reorienting-health-care-and-business-investment-priorities-toward-health-and-well-being-a-workshop (accessed March 20, 2020).

![]()

KEYNOTE ADDRESS

In her introduction to Surgeon General Adams’s keynote remarks, Cathy Baase of the Michigan Health Improvement Alliance said that the Surgeon General has made “better health through better partnerships” the motto of his work, beginning with the core partnerships between health care and public health, but also between the health sector and the business and other sectors. Adams stated that he had chosen to focus the signature Surgeon General’s report on a topic that is not a single health challenge but rather is intertwined with multiple causes of poor health: health and the economy, including the intersection of community health and economic prosperity. “Our society does not get value on the [health care] dollar because we focus on optimizing downstream coverage instead of tackling the upstream factors,” Adams said, adding that people’s health is shaped by the communities in which they live and the opportunities they have to make choices that promote health.

The Surgeon General said there is a growing recognition in the health sector that factors other than clinical care play more important roles in shaping health outcomes and that many in contemporary society are left behind by improvement efforts. Adams said one determinant of health is an individual’s connections to the community, including such things as parks and partnerships with faith-based organizations, and all of those connections are needed to ensure that people are born healthy and stay healthy. Adams said that “we’re not investing in the actions that we know could prevent diseases and truly reduce health care costs.” He added that much of the focus in health care now is on improving downstream coverage, which is important but not sufficient. Embracing an upstream approach (i.e., paying attention to the distal, high-level causes of poor health outcomes) does not exclude personal responsibility, Adams said, but he added that the choices people make are 100 percent dependent on the context, hence the need to recognize the value of the environment and the community in producing better health outcomes. Adams said his Surgeon General’s report will demonstrate the link between community health and economic prosperity, and in the same way that a past Surgeon General’s report “ended the debate on the link between smoking and health,” he said that he hopes his report will end the debate on whether health and economic prosperity are connected. Adams underscored the importance of focusing on the inequities in opportunities for good health, saying that “anyone’s poor health is everyone’s concern and cost.” Adams stated repeatedly—and drew from his personal experience to support his assertion—that collaboration with other sectors and bringing new organizations and nontraditional partners to the table are essential to any effort to achieve better health and economic prosperity.

PANEL DISCUSSION: HISTORY OF VALUE IN THE HEALTH CARE SECTOR

In the panel discussion that followed the keynote address, Magnan moderated a conversation with James Knickman of New York University (NYU) and Mai Pham of Anthem, Inc. on the history of value in the health care sector—key past milestones, recent shifts, and possible future directions, including what would be needed to sustain the current momentum from fee-for-service to value-based health care. Referring to the commissioned infographic (see Figure 1), Magnan noted that the infographic’s authors cautioned that the shifts being observed are fragile and incomplete. She asked, How can the momentum be maintained and funding be freed up to invest in better health and health equity?

SOURCES: Magnan presentation on December 3, 2018; commissioned infographic prepared by Sara Ivey and Bobby Milstein.

In response, Knickman described several less well-known provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act that offer potential opportunities for transforming health care systems, including the work of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Center and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the concept of accountable care organizations, and the Medicaid Innovation Accelerator Program. Knickman said the foundations of these initiatives and programs can be found in such work as the 1993 McGinnis and Foege3 article that described the actual causes of death in the United States and their upstream nature (i.e., how they are shaped by environmental and societal factors). Pham added that there are key concepts that have been articulated in health care, such as accountability to a third party and to the public, and the idea of a shift from a sole focus on institutional revenues and expenditures toward the concept of total cost of care (TCoC). Pham said that before the CMS Innovation Center’s request for information on TCoC was issued,4 the notion of TCoC as outlined by Richard Gilfillan and colleagues was unfamiliar to many working in health care. In an answer to a question from Magnan about the apparent lack of progress, Pham said that people need to be convinced that “this is in their own economic self-interest” and that achieving value-based care and population health and well-being will be a worthwhile accomplishment, but the case has not yet been made with sufficiently convincing arguments. In responding to Magnan’s first question about the fragility of the shift to a new concept of value, Knickman acknowledged that fee-for-service is “still king” and also that there is a need to build up the evidence concerning what is effective in influencing the social determinants of health. Knickman said that physicians understand those social factors are important, but they often do not see a role for themselves. He added that an additional challenge is the high degree of patient turnover, which makes a system focus on the health of populations much more challenging. Knickman described a logic model he developed to assist health system leaders interested in becoming involved with the social determinants of health. The model lists five drivers: (1) mission, which refers to the importance of corporate officers and board members becoming involved in more community-oriented activities; (2) business case, which involves recognizing the return on upstream investments, including the reputational boost of being viewed as an anchor institution and a community leader; (3) market concentration, which refers to whether there are competitors and if they are doing more (comparatively speaking); (4) an existing environment of community-based, cross-sector collaboration; and (5) legislation and government policies.5 Health system leadership is needed to develop a better understanding of how to influence the drivers of community health and increase value-based payment and evidence beyond the level of token action and toward scale, Knickman said (see Figure 2).

Discussion Period

During the discussion with the audience, Kindig of the University of Wisconsin–Madison said that he has long advocated for redirecting resources in the health care sphere, but he admitted to a sense of cynicism. He said the market forces behind genomics and proteomics both nationally and in his own community create powerful incentives in comparison to the modest incentives that exist for early childhood and similar non-clinical investments. As previously highlighted in the roundtable’s June 2017 workshop, Exploring Early Childhood Care and Education Levers to Improve Population Health,6 Kindig added, the marketplace for the people who provide the most valuable services, such as those in early childhood care and education, is “disastrous,” with minimal investments in what is a fundamental contributor to the health of the nation. Pham responded:

I think that we have the health care system we seem to want. We say we value community health, but we won’t stand for our employer cutting out a marquee provider from our network. We say that we want community well-being, but if there is a new $800,000 treatment that doesn’t cure but delays blindness, we’ll feel entitled to cover that and pay for it and apply minimal utilization management to it. We want the long-term strategies, but we’re seduced by new large buildings and new gadgets.

Perhaps, Knickman said, the only argument that works is to recognize that “we won’t have the next generation of people prepared by our investments to build the future we want.”

__________________

3 McGinnis, J. M., and W. H. Foege. 1993. Actual causes of death in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association 270(18):2207–2212. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/409171 (accessed October 13, 2019).

4 HealthPartners defines TCoC as the “cost of care provided to a patient (or ‘total cost index’),” including “professional, inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy, ancillary” along with an “approach to measuring resources used in providing that care (or ‘total resource use index’).” See https://www.healthpartners.com/ucm/groups/public/@hp/@public/documents/documents/dev_057633.pdf (accessed March 8, 2019).

5 See https://med.nyu.edu/chids/projects/enhancing-role-hospitals-improving-public-health (accessed January 21, 2019).

6 This Proceedings of a Workshop is available at https://www.nap.edu/25129 (accessed March 20, 2020).

NOTE: GDP = gross domestic product.

SOURCE: Commissioned infographic prepared by Sara Ivey and Bobby Milstein to inform conversations at the December 3, 2018, workshop.

Robert Kaplan of Stanford University and the former director of the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) remarked that the social determinants of health do not fit the conventional narrative of the health domain, where evidence-based guidelines exist for interventions such as managing cholesterol, but insufficient attention and resources (e.g., less than 3 percent of the NIH budget) go toward building the evidence base on the non-clinical factors that affect population health. Knickman said that building the evidence base for the social determinants of health is doable and that there is guidance, including from Kaplan, on how this research could be built. In the course of speaking about helping health systems engage in improving community health, Pham suggested that populations prioritized by health systems, such as consumers with private insurance and Medicare beneficiaries, could ask providers, perhaps through the advocacy of consumer organizations, to pay attention to social factors of patient populations. This could, Pham said, help make community-oriented interventions or engagement the routine way of doing business not only for those populations with the greatest needs, but also across entire covered populations.

PANEL DISCUSSION: HISTORY OF VALUE IN THE BUSINESS SECTOR

On the panel focused on the history of business investments, Lisa Richter of Avivar Capital moderated a discussion with Maurice Jones, the president and the chief executive officer of the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), and Lisa Williams, a vice president at Goldman Sachs. Richter began by describing key milestones in the way that values have shifted in capital markets. In 1968, the Ford Foundation began making “program-related investments” to advance charitable purposes. At roughly the same time, orders of women religious began making different investment decisions

with their often modest retirement funds (e.g., changing funds and their voting shares to support the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa). In the early days of the impact investing7 movement there were efforts both at the grassroots level and in major corporations aimed at taking into account the effects that investments had on U.S. communities. The field of impact investing and broader socially responsible investing, today increasingly known as “sustainable and responsible impact investing,” has evolved and broadened to include additional sectors, from community development to asset building. Over its 50-year history, impact investing has also evolved from being viewed as “granola fringe” to becoming more mainstream and professionalized, Richter said. This can be seen, for instance, in community development financial institutions (CDFIs), such as LISC becoming S&P rated and in mainstream financial institutions issuing bonds that incorporate “social and environmental criteria because that [i]s prudent risk management” and “might even help you to achieve a better financial return,” Richter said.

Jones provided an overview of the work of LISC, which is a part of the community development finance field. LISC began its work with housing to “catalyze markets for housing” in abandoned neighborhoods, he said. Jones defined a CDFI as “a niche financial institution that has a primary mission of community development in an underserved area or with an underserved population,” and he said that CDFIs work nationally. Jones said that gradually LISC has moved toward a broader range of ways to “spark imperfect markets” (e.g., schools, neighborhood markets, small entrepreneurs) and to be the first lender that would leverage other capital to underinvested or disinvested communities. CDFIs such as LISC take the first investment risk and thus break the path for investments from traditional financial institutions such as banks. Jones added that LISC has made $20 billion in underinvested or disinvested communities over 40 years and has leveraged $60 billion in investments. Current assets under management at LISC total $450 million, and the delinquency ratio on LISC’s investments is below 2 percent. Speaking then about the rural component of LISC’s investments, Jones said that attracting investment capital to rural areas is harder simply because of the lack of density. He added that these areas need more than just capital—they need local organizations and technical capacity and infrastructure, which are more often lacking in rural areas than in metropolitan areas. Furthermore, he said, incentives to bring in more capital are less powerful in rural America. Government is usually a partner in most LISC investments and there may be less governmental capacity to conduct sophisticated financial transactions in rural areas, Jones said. Still, he added, just because it is tougher does not mean it cannot be done, given the fact that LISC operates in 2,000 rural counties.

Jones described a milestone in impact investing. In 2010, leaders in the community development field received invitations to a dialogue with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco in recognition of an insight highlighted by the County Health Rankings. That annual ranking of all U.S. counties on health outcomes and health-related factors has shown that the bulk of factors that shape health reside outside of the health care sector. In response to a question from Richter about how this recognition affected LISC’s thinking, Jones offered an example of LISC’s partnership with the ProMedica health system in Toledo, Ohio, where LISC built a $45 million social determinants of health fund with a focus on housing and economic development (including workforce and small business development). The starting point for ProMedica was observing that food insecurity and poor housing conditions were key factors in the health conditions they were treating, Jones said. As the work progressed, the health care institution began to measure not just jobs created and housing units built, but also hospital readmission rates and other health metrics. LISC committed to a 7- to 10-year effort in Toledo, where the financial institution has a good relationship with community partners, Jones said, which has been an important contributor to the work’s success. He said CDFIs began to notice what hospitals had been observing for some time—namely, that there were disparities in life expectancy between under-resourced census tracts, where CDFIs work, and more affluent census tracts—and this observation indicated a need for a “marriage” between the two fields. At this time, he continued, CDFIs like LISC are looking for ways to scale those cross-sector relationships. Richter remarked that access to capital is a health determinant but that people do not often think about the flow of capital in relation to health—perhaps because, like the market, the connection is invisible. Still, he added, its effects are significant.

Williams offered insights from her work helping individuals and institutions align their capital with their values. Two important considerations are the nature of the organization and its intent, she said. The clients for impact investing services range from high net-worth individuals to institutional offices, and their goals span a range of impact and return objectives. Some clients, such as family offices, use a geographic lens to focus their investment activities and maximize their returns, Williams said. Others may be interested in such areas as environmental and social goals, and the stakeholders of some institutions want to know that their investment capital aligns with the interests of the population being served as well as of the constituents of the investing organization. Williams offered pension pools as an example; if, for instance, such a pool is managing retirement savings for food industry workers, the investor may

__________________

7 According to the Global Impact Investing Network, “impact investments are investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.” See https://thegiin.org/impact-investing/needto-know/#what-is-impact-investing (accessed March 20, 2020).

seek alignment with the employees’ work (e.g., by targeting investments that are health food–oriented or that create local jobs). The perspective in shaping the entire asset mix of an institution goes beyond the philanthropic and includes attention to asset allocation (e.g., bonds, stocks, private venture), Williams said. She asked, if the goal is a more healthy and equitable community, what might investments look like?

Williams said that on the public market side,8 an investment’s proximity to its effects might be the most important consideration. Investors may not want to invest in tobacco or fossil fuels, and the high-level themes for investing may be health and well-being (e.g., in companies positioned for growing wellness trends and sustainability). On the private market side, there are growing investments in traditional companies that are creating health-related innovations, particularly innovations that support the transition to value-based care. For example, administrative burden and poor coordination of care lead to waste, so investors are interested in businesses that transform the business of health care, Williams said. That could include, for example, companies looking to automate “low-value” tasks to enable more clinician time with patients. She said in the domain of affordable housing, opportunities are found in looking at specific populations in need of affordable housing, such as people with intellectual disabilities, and “asking how to create safe, quality housing and do that in an institutional way, and working with hospitals to facilitate this.”

Discussion Period

During the discussion period, Williams responded to a question about quantifying impact. She said that qualitative examples and progress are needed because investors tend not to allocate capital by providing metrics to report on, but rather “ask what are key pieces that tie to the business” and how those pieces increase revenue, as well as ask how progress can be measured. It is also important to communicate with the people making the investment decisions and to incorporate community voices wherever possible, perhaps through grant makers, she added.

Baase asked whether investors focus more on upstream or downstream investments in health. Williams responded that some investors are interested in specific diseases, while others focus on technology to improve information sharing, logistics, and care. Richter added that there are health sector funders who are looking at upstream opportunities from housing to small business, who have a people–place–planet focus. Such funders may, for example, recognize that climate risk is human health risk, or the fact that sectors such as education have a high impact on health later in life, therefore underscoring the importance of investing early in the life course or early in the disease course.

Jones said that LISC partners with investors who are helping to develop supermarkets and engaging in efforts to develop housing and financing for federally qualified health centers.9 Paula Lantz of the University of Michigan spoke about several years of research on pay-for-success financing—private and third-sector (i.e., philanthropic) capital is raised, and the government agency involved pays back the investment if the metrics for success are met—used to address population health and issues related to social determinants of health. Lantz said that the model has promise and has had some success, but she added that there are also pitfalls that her research has highlighted. Jones responded that the private sector needs the bridge financing that pay-for-success models offer. In her response, Williams noted that the fundamentals of a project could change over a few years, as stakeholders and relationships evolve over the life of a bond; these are, she said, “very bespoke projects and hard to put into an easy Excel model.” However, she added, pay-for-success financing is an important instrument, and public–private partnerships are needed to maximize its potential.

Abhishek Pandey of NYU Langone Health asked how investors handle the long time needed to get answers to some questions or to observe outcomes of interventions. Williams answered that there are constructs to help address that issue, such as fund lives, which are 10 years or longer, and evolving evergreen funds, which require people to be comfortable with their capital being locked up for a longer timeline and allow investees to build and observe over a longer time horizon. Williams added that what is needed in those cases are mid-term metrics and other innovative structures that can help mitigate the uncertainty associated with long timelines. Jones noted that it is hard to attract investment in early childhood because the outcomes will not be known for 10, 20, or even 30 years. Foundations can use program-related investment dollars to model successful interventions that can be scaled. Jones offered the example of LISC’s $200 million Healthy Futures Fund (HFF), an initiative to finance the development of federally qualified health centers in underserved areas and invest in affordable housing that incorporates health programs for low-income residents. HFF included philanthropic, private-sector, and nonprofit health care investors. Although the affordable housing issue probably will not be fixed in 15 to 20 years, progress can be made, Jones said. He called this “patient” capital, adding that in order to help secure new investors, those who require capital have the opportunity to orient or familiarize those supplying it with the idea that some work needs to be done over the long term.

__________________

8 Publicly traded as opposed to privately held companies.

9 For example, LISC partners with Morgan Stanley and The Kresge Foundation in the $200 million Healthy Futures Fund that finances the development of federally qualified health centers. See http://www.lisc.org/our-initiatives/health/healthy-futures-fund (accessed March 20, 2020).

Mary Pittman of the Public Health Institute asked how investors deal with gentrification that displaces people who have lived in a community for a long time. Jones answered that there are anti-displacement tools to handle this, and he offered the example of the creation of a housing fund in the San Francisco Bay Area. The key, he added, is to implement investment and anti-displacement measures simultaneously.

PANEL DISCUSSION: HEALTH CARE SECTOR LEADERSHIP

Gary Gunderson of the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center and Stakeholder Health introduced two panelists from Cleveland’s University Hospitals (UH) for the panel on health care sector leadership.

Heidi Gartland of UH began her presentation with an overview of the health system’s 10-year experience with investing in its own neighborhood. Gartland said its foundation began with the system’s recognition that it could invest in brick and mortar buildings or build community wealth, and the system decided to do the latter. In recognition of the 80 percent of non-medical factors that shape health outcomes (per the County Health Rankings model), UH began to tackle the legacy of disinvestment, poverty, real-estate redlining, and other structural racism factors that affected its home neighborhoods. Gartland said the system’s approach was “living local, hiring local, and working local,” referring to the focus of workforce development and employment (e.g., training and hiring), procurement (e.g., establishing a produce co-operative and a laundry), providing forgivable loans to enable staff to purchase housing, and shifting operations to the local urban community being served (as opposed to the suburbs). Eventually the UH anchor strategy that began with the decision to invest $750 million in the local economy for a period of time became a way of life and the spirit that animated multiple relationships with local organizations and residents, Gartland said.

Next, Patricia DePompei described UH’s most recent investment in addressing the health care needs of infants and women in the Greater University Circle area communities served by the Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital and the MacDonald Women’s Hospital. She said in the process of preparing the 2015 community health needs assessment, UH leaders recognized that the organization needed to be much more engaged in and with the community and also to earn the community’s trust. To accomplish this, UH established a community advisory board, consulted with and formed relationships with stakeholders in the community, and surveyed community residents and patients about their needs, DePompei said. In addition to assembling data on health outcomes and the profound health disparities among neighborhoods, which were provided by the Cuyahoga County Board of Health, UH leadership also learned about the health-related social needs of the communities UH serves, such as the fact that patients and their families experience housing instability, food insecurity, and other challenges. The new UH community-based centers, one built with philanthropic funding and new markets tax credits and another built with support from a new CMS Innovation Center competitive grant, also include patient navigation, medical–legal aid, and other supportive services to meet the spectrum of patient needs. These developments have made UH increasingly attractive to newly minted clinicians. In turn, UH residents are becoming familiar with the idea that in order to move the needle on the community’s health, it is not enough just to deliver care, but they also need to address the social determinants of health.

Discussion Period

During the discussion period, Magnan asked DePompei and Gartland what they would put on a policy wish list for Medicaid, which is UH’s biggest payer. Gartland said she would like to have the opportunity to share ideas with the incoming Ohio governor regarding Medicaid managed care and to build on the innovative models for population health that have already shown positive results. Gartland added that one challenge to transforming the way care is delivered across an entire population may arise from payers in a region varying in their willingness to make changes to their models of care.

Milstein asked whether the place-based and community-centered strategy UH adopted has altered its sense of competition with other major health systems in the area. Gartland responded that she chairs the regional hospital association and that the table has been set for collaboration, beginning with community health needs assessments that were carried out through the organization’s work with health departments, but also in additional areas, such as infant mortality, through First Year Cleveland and Northeast Ohio Opioid Collaborative.

Baase introduced the featured business sector leadership example after the health care sector leadership examples. Baase started the conversation with Jamie Rantanen of Bank of America (BofA) U.S. Trust with a question about that financial institution’s social impact vision. Rantanen outlined how BofA issued its first environment, social, and governance (ESG) manual in 2008 and how, informed by lessons from the 2008 financial crisis concerning the importance of understanding and anticipating ESG risk, it has regularly updated this manual as a set of guidelines for growing responsibly. BofA excludes companies that negatively affect environmental or social issues or that lack standard employee benefits, such as a living wage. Rantanen said that public market investment opportunities are growing,

along with opportunities to combine these opportunities with private market and place-based investments. Impact investing is important to millennials, he added. Also, an interest in alignment with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals is among the factors that have led to investment portfolios focused on low carbon, global equality, religious views and values, and girls’ and women’s rights.

Milstein asked how investment advisors are trained, and Rantanen answered that the U.S. Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment provides training for advisors and that the certified financial advisor curriculum has added an ESG requirement for the completion of certification. Inside financial sector organizations, dedicated portfolio management training is available for interested portfolio managers. Rantanen added that portfolio managers and advisors who do not adapt to the ESG movement will not have clients in a decade. As advisors get better at understanding how to allocate, they will come to recognize that traditional investing and ESG and impact investing are “one and the same,” he said. Marc Gourevitch of NYU Langone Health asked what proportion of investments are ESG investments and to what that total might grow. Rantanen responded that it depends on the investment type (e.g., investing in small capitalization stocks is much harder to do with an ESG lens than investing in large companies with track records that can be compared with non-ESG counterparts). Private market ESG is becoming increasingly easier to access, Rantanen added.

CLOSING SESSION

In the day’s closing session, Phyllis Meadows of The Kresge Foundation invited those assembled to participate in a practical exercise intended to help them think about how they might take the information learned throughout the day and apply it in their leadership positions and practices. Meadows described a fictitious mid-size city named Ourlandia, where a former leading manufacturer of industrial glass has fallen on hard times. As a result, the communities in the area are declining in population and having difficulties transitioning in the new economy. The participant handout included a few additional details about the demographics, socioeconomic status, health, and other characteristics of Ourlandia’s population.

For the purpose of the afternoon’s discussion, participants were asked to divide into small groups that would play the role of either (1) a hospital board, or (2) a pension fund board, and as such, to consider the range of investment opportunities and potential pitfalls facing them as they assess how best to support their city’s renaissance. Each “board” received the following hypothetical resources: an annual community health fund of $45 million, 15,000 employees, a $4.5 billion endowment, and $450 million in annual revenues. Participants also received a menu of possible opportunities for investments that their hospital board or pension fund board could consider. These options included food security, nature and land use, clean environment, and transportation.

Meadows invited the small groups to answer each of these four questions:

- What are going to be your most compelling priorities for the renaissance of Ourlandia?

- How do these priorities reposition you, either if you are from the health side or the pension side?

- What trade-offs did you consider when you set those priorities? What trade-offs might you consider if you were to invest in Ourlandia’s renaissance?

- What leadership challenges will you have to overcome in order to invest?

Afterward, when the groups reported their answers, Malcolm Fox of the Global Reporting Initiative spoke about comments made by participants in one of the hospital board groups, which included suggestions to invest in both short-term needs and long-term growth. He said that several participants commented on the importance of engaging community leaders and key organizations such as the local government and the local chamber of commerce. Meg Guerin-Calvert of FTI Consulting, a participant in the same group, said that the information that would be unearthed by a community health needs assessment was part of the discussion and that workforce development (e.g., providing training for medical staff, offering vocational training to community members) was a possible strategy to consider. In response to a question from Meadows about prioritizing those actions that the group members believed would really make a difference, Fox said that the group’s members had different priorities, ranging from advocating for transportation to promoting child care for hospital staff and including a mix of both immediate needs and long-term ideas. He said that the hope was that a group such as the hospital board could do both—tackle some immediate needs in the community, but not get stuck there and also look to the future with more transformative plans.

Gunderson reported on his pension fund board group’s conversation. One complicating factor mentioned by a participant was a lack of clarity about the fund’s fiduciary duty to its 200,000 members versus to the larger community of Ourlandia. Some participants in the small group suggested investing in early childhood care and education, but

the long return horizon was a concern for others. One member distinguished between retirement for people who had worked in lower-wage manual labor as opposed to the creative class that experienced less physical wear and tear.

Ivana Vaughn of The New York Academy of Medicine, a participant in another hypothetical pension fund board, spoke about her group’s idea to title their effort “Doing Well by Doing Good for Ourlandia” and described how the group brainstormed about possible opportunities to invest both locally and nationally/internationally. The opportunities the group came up with ranged from early childhood to social justice and from criminal justice to investments in the environment and natural resources/tourism. Some group members also commented on how they saw a shift to a more active role for the pension fund board as well as a recognition of the importance of building leadership among local residents to ensure the sustainability of some of the community change efforts. During the brief question-and-answer period, Terry Allan of the Cuyahoga County Board of Health said that for him the group discussions echoed the real conversations that take place in communities that are working to reimagine their futures and build a path forward. Meadows said that she was struck by the common attention to gross and growing inequalities in the community and to potential solutions for those challenges. Gunderson commented that the pools of assets represented by the hypothetical hospital boards and pension fund boards had been “accumulated under one set of rules” and are “difficult to align with new values, including equity.” Another participant said that it is incumbent on the leaders in the room to make the connection between economic health and health in order to ignite the discussion and that a community like Ourlandia, which had lost 15 percent of its population over the past three decades and has deep disparities in health and wealth, would present a considerable challenge. Another audience member remarked that in a real-life setting, an organization’s staff would likely have set the table for the board discussion. The group dialogue illustrated “a fundamental shift in governance conversations”—who tees up and shapes the agenda community input is integrated into the process. Such conversations could shift the decision regarding “how big of a bet do you play versus protecting the long-term assets of the hospital in the way they’ve always been protected.”

After listing the negative aspects of life in Ourlandia, Meadows commented on the importance of celebrating the assets and promise of communities, even in a context where communities feel the “weight of negative figures and facts.” Meadows asked how leaders in communities could reorient governance structures and historical patterns of giving to become more active. One participant responded by sharing the example of a health system chief executive officer who went to his board and spoke about how developing a rural health—not merely a rural health care—model would call for having conversations with the community and hearing “things that we don’t want to hear.” In response to another question from Meadows about the capacity to do the work of reorienting investments, Gunderson said he believes that many hospital board members serve in that capacity precisely because of their abilities to invest and effectively manage funds. Board members could be “set free” to bring all of their expertise and capacity to bear on their role instead of acting in accordance with a narrow definition as “hospital board members.”

Josh Sharfstein of Johns Hopkins University acknowledged that “people sometimes have very traditional reasons for joining boards” and said that it is easy to lose them when speaking of rethinking health care and changing “some of the underlying drivers of poor health” to “put their community on a more stable path.” “Wouldn’t it be great,” he said, to have “the West Baltimore Investment Fund or the West Philadelphia Investment Fund that people could actually put [money] in and know how much it was and know that there was money being invested in the right things?”

Milstein made closing remarks about the day, acknowledging the reasons for pessimism about how the values that inform where today’s society places resources often seem “contrary to where the evidence has accumulated over decades of where [investments] would generate better health and well-being.” However, he also acknowledged reasons to be optimistic. He said the day’s stories illustrate how wealth is becoming connected to context, from physical places to aspects of what enhances community well-being.◆◆◆

DISCLAIMER: This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Alina Baciu as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. The statements made are those of the rapporteur or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants; the planning committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

*The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s planning committees are solely responsible for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers. The responsibility for the published Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief rests with the rapporteur and the institution.

REVIEWERS: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Meg Guerin-Calvert, Center for Healthcare Economics and Policy, FTI Consulting. Lauren Shern, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS: This workshop was partially supported by Aetna Foundation, The California Endowment, Health Resources and Services Administration, Kaiser Permanente, The Kresge Foundation, New York State Health Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Program Support Center.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/PublicHealth/PopulationHealthImprovementRT/2018-DEC-03.aspx.

Suggested citation: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Reorienting health care and business sector investment priorities toward health and well-being: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25469.

Health and Medicine Division

Copyright 2020 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.