3

Processes of the Minerva Program

This chapter provides an overview of the processes involved in the awarding and management of the Minerva Research Initiative grants, including (1) selecting topics for research funding, (2) soliciting submissions, (3) reviewing proposal submissions (white papers and full proposals), (4) selecting awardees, (5) awarding the grants, (6) managing the grants and monitoring grant progress and performance, (7) supporting dissemination activities, and (8) supporting translation activities. This overview is followed by the committee’s evaluation of ways in which these processes could be refined to enhance the performance and efficiency of the program going forward.

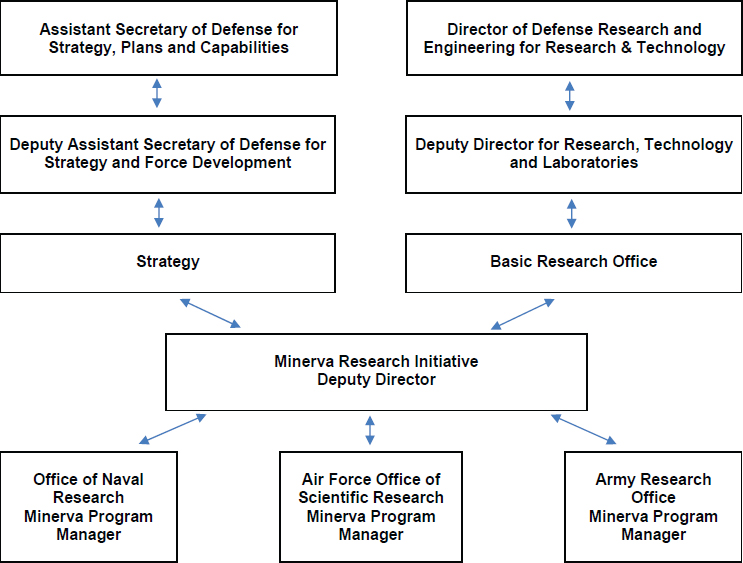

As discussed in Chapter 1, the Minerva Research Initiative was envisioned as a unique collaboration between research and policy divisions within the Department of Defense (DoD). The vision for the program was to work together to support basic research on social science issues deemed to be important to national security, and then find ways of integrating insights from this research into the policy-making context. The collaboration was structured to involve the research units and program managers from three military service branches: the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), the Army Research Office (ARO), and the Office of Naval Research (ONR). The grants are executed through the service branches, with the program managers providing technical oversight for the projects. Figure 3-1 illustrates the organizational structure of the Minerva program. At the time this study was initiated, the ARO program manager served as interim director for Minerva. When a new deputy director was brought in, the interim director became assistant director, but the assistant director position was dropped when ARO

NOTES: The bottom row of the figure represents the military service branches. The Army withdrew its support as of October 1, 2018, and will no longer manage new grants. The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans and Capabilities is in the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (OUSD-Policy). The Director of Defense Research and Engineering for Research and Technology is in the Office of the Under Secretary for Research and Engineering (OUSD-R&E). Both OUSD-Policy and OUSD-R&E are units within the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). The Minerva Research Initiative is housed in OSD and managed jointly by OUSD-Policy and OUSD-R&E.

pulled out of the program. Minerva is currently overseen by a “deputy” director instead of a director for administrative reasons, and aside from the deputy director, the Minerva program office contains no additional staff.

OVERVIEW OF PROGRAM PROCESSES

Until 2017, the Minerva program was overseen primarily by the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (OUSD-Policy) and the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (ASD-R&E) within the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). The service branches were responsible primarily for executing and managing the

SOURCE: Adapted from Montgomery (2019).

grants and had a relatively minor influence on the white paper and proposal review processes. Beginning in 2017, DoD restructured the program to emphasize a more equal partnership between OSD and the service branches. The service branches are now involved in all aspects of grant operations. Table 1-1 in Chapter 1 shows the division of responsibilities before and after the restructuring.

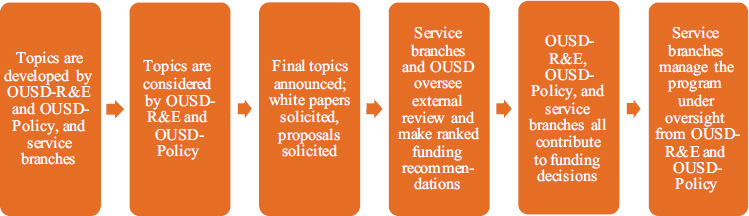

Figure 3-2 shows the current sequence of steps involved in managing the program. The processes entailed in program operations, including the changes that have taken place over the years, are described in further detail below. This description of the program’s processes was compiled on the basis of information provided by DoD staff involved with the program, including current and past Minerva directors and service branch program managers. Given that ARO was part of the Minerva Research Initiative from the beginning and was still part of the program when this evaluation was launched, the discussion of processes includes ARO’s experiences.

Topic Selection

To ensure that the Minerva grants address knowledge gaps and national security needs, funding announcements highlight topics that represent questions of interest to DoD. Box 1-2 in Chapter 1 shows the topics included in the 2018 Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA), while Appendix B shows all topics since 2008. The topics are broad, and proposals are not limited to the topics specified. The general themes are also relatively consistent from year to year. For example, the 2018 list of topics included “Sociopolitical (In)Stability, Resilience, and Recovery,” while the 2017 list included “Societal Resilience & Sociopolitical (In)stability.” Since 2018, the FOA has also discussed topic alignment with the National Defense Strategy.

As discussed, the process used for topic selection has changed over time from one that was top-down (from OSD to the military service branches) to

one that is now more collaborative. Currently, the service branch program managers generate topics and then work with OSD to refine those topics and ensure that they also represent DoD-wide priorities.

The process for generating topics of interest varies by service branch and is dependent largely on the program managers’ preferences. Suggestions for potential topics are gathered by email or discussion with other personnel and leadership in the service branches. Some service branch program managers focus on honing a particular topic over several years and finding what best accords with the service branch’s and OSD’s strategic vision. Other service branch program managers focus on balancing the priorities of their service branch and the objectives of the Minerva program while at the same time aligning potential topics with the portfolio of their own larger research program area.

The topics that originate in the service branches are nominated for inclusion in the FOA. The central Minerva program office may also solicit topics from within OSD. The Minerva program office reviews the draft topics and discusses them with the service branches and then with OSD before the list of topics is finalized.

Soliciting Submissions

Grant announcements are disseminated through grants.gov, which is a primary vehicle for distributing information about government grant research funding and is used by universities to learn about funding opportunities. In addition, information about the announcements is posted on the Minerva website, and the Minerva program office maintains a mailing list of individuals who have expressed an interest in receiving updates about the program. Typically, new Minerva funding opportunities are announced at the beginning of the calendar year; in 2018, however, the announcement was delayed until May because until then, the Minerva program office had only a part-time interim director in place.

Reviewing Proposal Submissions

As noted in Chapter 1, the Minerva program’s proposal process consists of two stages. In the first stage, researchers are asked—but not required—to submit white papers briefly summarizing their proposals. Researchers whose white papers are deemed most competitive then receive an invitation to submit a full proposal.

The turnaround time for white paper submissions tends to be short, and full proposals are due a few months later. In 2018, because the FOA was not posted until May, the turnaround time for full proposals had to be condensed. Thus the FOA was posted on May 24, white papers were due

on June 19, and full proposals were due on August 14. By contrast, in 2016 (a more typical year), the FOA was posted on January 12, white papers were due on February 29, and full proposals were due on July 1.

The 2018 criteria for reviewing proposals were

- scientific merit;

- relevance and potential contributions of the proposed research to areas of interest to DoD;

- potential impact, including potential for building new communities, new frameworks, and opportunities for dialogue;

- qualifications of principal investigators (PIs); and

- cost and value.

The 2018 FOA highlighted scientific merit and relevance as the two, equally important, principal criteria for evaluating proposals. Potential impact, PI qualifications, and cost and value were described as less important.

Prior to 2017, OSD took the lead in reviewing white papers. Under the changes instituted in 2017, the service branch program managers (in topic areas assigned to their branches) or the Minerva program office (in topic areas assigned to OSD) reviews white papers and decides who will be invited to submit full proposals. The white paper review involves the “responsible research area point of contact” (typically the service branch program manager) and one or more subject matter experts. DoD systems engineering and technical assistance contractors also may assist the responsible research area points of contact. The white papers that best meet the evaluation criteria are recommended to the OSD Minerva Steering Committee, which includes representatives from OSD and representatives from the service branches (Department of Defense Washington Headquarters Services/Acquisition Directorate, 2018, pp. 22–23). As noted, a subset of the researchers who submitted white papers are then invited to submit full proposals. For the 2018 funding cycle, DoD received 192 white papers and 52 full proposals.

The service branches now also have a larger role in reviewing full proposals, in collaboration with the Minerva director. In 2018, another OSD staff member, with a Ph.D. in political science, was invited to comment on the scientific merit of the proposals. The proposals are evaluated for policy relevance only after having been evaluated for scientific merit. Policy relevance may be used to decide between two proposals of equal scientific merit.

Within the service branches, each program manager recruits four to five people for the review panel that evaluates the proposals. Typically, the panel includes some outside academics, individuals with expertise in the topic

area, and at least one DoD staff member. Depending on the topic areas and service branch requirements, some panels comprise larger or smaller numbers of academics or policy experts, some panels include academics from military colleges or universities, and some draw experts from within the relevant service branch (in addition to the service branch program manager leading the evaluation). Proposals are rated by the reviewers on a qualitative scale ranging from unacceptable to outstanding, based on the criteria described above.

The evaluation criteria and processes used by DoD from 2008 to 2018 appear to have remained fairly consistent, except for the structural changes introduced in 2017 and other minor changes over time. Details about the processes, however, do not exist in written form, except to the extent that they are captured in the FOAs.

Because some of the Minerva grants were managed by the National Science Foundation (NSF) when the program was first launched, and because NSF grants are familiar to many academic researchers conducting social science research, the processes used by NSF are also briefly described throughout this section. The survey results discussed later in this chapter provide some insight into how satisfaction with these processes compares between Minerva and NSF grantees. The surveys also asked about experiences with Department of Homeland Security (DHS) grants and other social science grants administered by DoD, but relatively few respondents had experiences with grants other than those of Minerva and NSF.

The merit review criteria and evaluation process used for the Minerva solicitation in 2008 followed NSF procedures, which are similar to DoD’s as just described (National Science Foundation, 2008). NSF sometimes encourages white papers, but this is not typically the case. Often, letters of intent are requested (as was the case in 2008), and these letters are used primarily to gain a sense of the number and content of the proposals being submitted to facilitate planning for the review panels and other logistics. NSF proposals are typically reviewed by ad hoc panels of mainly academic reviewers (in contrast with DoD’s panels of reviewers, which, as noted, often include government civilians). NSF reviewers apply two main review criteria: “intellectual merit,” which addresses the potential to advance knowledge, and “broader impacts,” which denotes the potential to contribute to the attainment of desired societal outcomes. The review also includes attention to the plan for carrying out the proposed activities, as well as the qualifications of the individual or team that will execute the project and the adequacy of resources. Summary ratings with accompanying narratives developed by the reviewers are considered by the program officer, who manages the review and makes recommendations for funding.

Selecting Awardees

The panels reviewing the full proposals rank order the projects they consider fundable and send their recommendations to the Minerva program office, along with a summary of the strengths and weaknesses of all proposals reviewed and the degree of consensus among reviewers. The Minerva program office aggregates the reviews and recommendations of each panel for each topic area and produces a report of the results. Minerva program office staff then meet with OSD staff and the service branch program managers to make final decisions on which projects to fund and the level of funding. The 2018 grant announcement states that “the recommendations of the various area POCs [points of contact] will be forwarded to senior officials from the OSD who will make final funding recommendations to the awarding officials based on reviews, portfolio balance interests, and funds available” (Department of Defense Washington Headquarters Services/Acquisition Directorate, 2018, p. 23).

Awarding the Grants

Once sign-off on the list of grants to be funded has been received, the Minerva program office circulates the list of projects throughout DoD and sends award letters to the PIs who have been selected to receive a grant. As noted above, in 2018, proposals were due on August 14; the awards were then announced in January 2019. A letter is also sent to those who did not receive awards. The program managers from each service branch then follow up and implement the grants though their procurement offices. The proposals, recommendations, ratings, and assessments become part of the grant packages.

Once PIs have been informed that they will be funded, the program managers discuss with them expectations for their projects and any points of concern. A kick-off meeting is sometimes held, particularly for larger projects.

Some service branches require grantees to have human subjects research approval from their home institution and by the service branch’s institutional review board (IRB) before a grant involving human subjects is awarded. A service branch’s IRB may or may not accept the university’s IRB approval, and this can contribute to a considerable delay in the transfer of funds.

Managing Grants and Monitoring Grant Progress and Performance

The 2018 grant announcement described three categories of expectations for Minerva researchers: project meetings and reviews, research output, and reporting requirements (Department of Defense Washington

Headquarters Services/Acquisition Directorate, 2018, p. 7). Project meetings and reviews include participation in the Minerva Conference, typically held annually in the Washington, DC, area; individual project reviews with the service branch sponsor; project status reviews focused on the latest research results and any other incremental progress; and interim meetings as needed. Research output includes expectations for products, publications, and analytical summaries of findings that can be shared with the government and others. Reporting requirements are for annual and final technical reports, financial reports, final patent reports, and copies of publications and presentations.

Because a grant is executed between the sponsoring service branch and the grantee’s academic institution, the service branches manage the grants. OSD is not directly involved in grant management because it is not structured administratively to perform these types of functions. The Minerva program office obtains information about the status of awards, delays, and progress from the service branch program managers. The Minerva program office has no direct access to progress reports submitted to the service branches (all of which have different requirements and timelines). As discussed in Chapter 1, at the time of this writing, a centralized Minerva grants database was under development to help monitor grant funding and progress.

At the individual service branch level, various methods are used to monitor grant performance and progress. Some service branch program managers write to grantees immediately after their award to let them know what is expected of them, such as obtaining IRB approval, if needed; sending monthly invoices; and maintaining regular contact. Some program managers request to be informed about dissemination activities related to the project, such as briefings, interactions with the media, conference submissions, and awards. Some service branch program managers are able to monitor grantee spending rates more closely than others. ARO’s approach was to conduct site visits for every grant at least once in the life cycle of 3- to 5-year grants. AFOSR and ONR convene their own annual program reviews, which tend to be weeklong events and include a review of Minerva grants—in the case of AFOSR, a subset of those grants, selected by the program manager on a rotating basis.

Each branch also has its own requirements and procedures for obtaining annual progress reports. Some send formal annual progress report forms to PIs with an automated request to complete them by the same date each year, regardless of when the grants started during the year. Some service branch program managers receive reports about which annual reports have been submitted and which are overdue. The forms used for progress reports vary across the branches.

NSF postaward reporting requirements are broadly similar to those of the DoD service branches. They include annual and final project reports

with information on accomplishments, project participants, publications, other products, and impacts. Grantees are expected to monitor adherence to performance goals, time schedules, and other conditions of the grant. Contact between the NSF program officers and PIs is encouraged to address progress and changes in projects.

Supporting Dissemination Activities

Dissemination of the findings from Minerva research commonly occurs at the individual project level; some Minerva researchers are particularly well known in the national security community, publish a great deal, attend professional conferences, and are asked to provide briefings to various audiences on their projects. DoD facilitates several forms of dissemination, but staffing constraints in the Minerva program office limit such efforts, including dissemination about Minerva to the broader social science research community.

The annual Minerva Conference is a major dissemination venue where connections can be forged across research, policy, and national security communities. At the 2018 conference, an effort was made to highlight the National Defense Strategy and to generate more interaction between DoD policy staff and the Minerva researchers so as to showcase who is being funded and what is being learned.

Another avenue for dissemination is the Strategic Multilayer Assessment, a DoD organizational unit operated by the Joint Chiefs of Staff that sponsors a joint lecture series with the Minerva program. Minerva speakers are invited to speak on topics that address challenges faced by the Joint Chiefs.

Efforts also are under way to build the dissemination capacity of the Minerva Research Initiative website. These efforts include redesigning the website by (1) changing the URL to minerva.defense.gov to be less focused on the military (the previous web address was http://minerva.dtic.mil), (2) incorporating a series of social science blogs in which researchers will discuss their research to educate people on social science contributions to national security, and (3) adding information about all of the Minerva grants.

At the service branch level, dissemination often occurs through responses to calls for information on research findings from individuals or organizational units, such as special operations, training groups, or other DoD branches. Colloquium-like events where research can be proactively disseminated are being considered as another vehicle.

Supporting Translation Activities

Translation activities (also referred to as transition or transitional activities) are steps that can be taken to translate basic research to applied research. DoD defines basic research as “systematic study directed toward

greater knowledge or understanding of the fundamental aspects of phenomena and of observable facts without specific applications towards processes or products in mind,” and applied research as “systematic study to gain knowledge or understanding necessary to determine the means by which a recognized and specific need may be met” (Department of Defense, 2017). DoD refers to funding allocated for basic research, such as the Minerva grants, as 6.1 funding, and to the funding allocated for applied research as 6.2 funding. In 2018, the Minerva program office initiated a request for some 6.2 funding, but this request did not receive sufficient support to advance.

Service branch program managers sometimes promote the work of their grantees to other funders and refer them to other funding streams, including 6.2 grants, for follow-on research. Potential funders include the Department of Justice, the Department of Homeland Security, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency. Technical exchange meetings between PIs working on 6.1 and 6.2 projects within the service branches and between PIs and Central Command or Special Operations Command also facilitate translational activities.

In two cases, the results of Minerva research projects were advanced to 6.2 grants. These cases fell into an area of analytics that could be applied to open-source data and a variety of problems.

DISCUSSION OF MINERVA PROGRAM PROCESSES

The committee’s evaluation of the Minerva program processes revealed opportunities for process improvements both to strengthen the program and to enhance the grantees’ experiences.

Process Improvements to Strengthen the Program

A particularly challenging aspect of the Minerva program’s organizational structure is the need to coordinate the interests of the policy office and the service branches. The two bring different perspectives to the Minerva collaboration, and the resulting tensions are understandably difficult to navigate. Policy makers typically need answers quickly and are accustomed to making decisions based on the information available at the time. By contrast, academic research—the focus of the research units within the service branches—involves investigating a question thoroughly before conclusions suitable to inform policy decisions are reached.

As discussed, these tensions lead in practice to challenges associated with the process of identifying research priorities (topics) and projects to fund in a given year. During the early years of the program, the views of the policy office carried more weight in the decision-making process relative to

those of the service branches, and as a result, the service branches felt less invested in the Minerva program. To address this, the service branches were given a much more active role in recent years. It appears, however, that the shift came too late for ARO, which as noted, decided to withdraw from the partnership at the end of 2018 and will no longer participate in supporting new awards (the ARO program manager will continue to manage the existing ARO awards).

Based on the interviews with DoD staff, it appears that the service branch program managers are decidedly more satisfied with their role in the program under the current arrangement. It is important to note, however, that an emphasis on the types of basic research projects that the service branch research units consider a good fit for the program might be less satisfactory for DoD staff who are looking at the merits of the projects funded through the lens of their potential policy applications. In addition, DoD-wide priorities (represented by two of the topics funded in 2018, “Economic Interdependence and Security” and “Alliances and Burden-Sharing”) are, by definition, broader than the topic areas of interest to the service branches.

It is too early to assess how well the new structure is functioning. There are no easy solutions that could result in a completely harmonious process, and it is likely that compromises will always be necessary. However, deepening the understanding of the Minerva Research Initiative and actively nurturing collaborations in support of the program across DoD divisions is essential. Changes in several areas, discussed below, could lead to a smoother process and a stronger program.

The Minerva program operates with a very small staff, and over the course of the past few years was overseen by an interim director who was able to dedicate only 20 percent of her time to the program. The current deputy director was brought on board as part of the Intergovernmental Personnel Act Mobility Program, which facilitates the temporary assignment of individuals from other organizations to government positions. The former interim director (and ARO program manager) served in the capacity of assistant director until ARO withdrew from the program. The service branch program managers oversee individual grants on behalf of their branches. (For further detail on the organizational structure of the Minerva program, see Chapter 1.)

Most of the changes identified by the committee as priorities for strengthening the Minerva program and improving its performance require the attention of a full-time leader, in a position designed for the long term. To ensure continuity and appropriate stature, the director needs to hold a civil service position at the GS-15 level (or higher) and have a relevant Ph.D. or equivalent experience with the types of research that are funded by the program. To implement the committee’s recommendations for improving the program,

the Minerva office might also need an additional staff person, such as a research assistant, or the ability to bring in help for specific tasks as needed.

RECOMMENDATION 3.1: The Department of Defense should ensure that the Minerva Research Initiative has a leader with appropriate credentials and stature in a full-time, civil service position.

RECOMMENDATION 3.2: The Department of Defense should evaluate what additional support staff are needed for the Minerva Research Initiative to achieve its goals and implement the recommendations in this report.

The committee identified two tasks that are high priorities going forward (Recommendations 3.3 and 3.4 below). The interviews conducted with DoD staff for this study made it clear that the Minerva program is not as well known within DoD as it could be, and its unique benefits are not well understood by all those in leadership positions across the divisions. Some of this lack of understanding is due to the challenges associated with the program’s focus on basic research and the inherent lack of immediate policy applications. However, there is also a lack of general awareness within DoD and the broader national security community of what the program does, the specific projects that are funded, and the expertise of grantees.

While the aim of basic research is not to produce immediately usable policy insights, the Minerva grantees’ work in particular geographic areas of the world on a variety of priority topics has yielded a wealth of knowledge that appears to be highly underutilized, based on the input received by the committee, and particularly through the interviews with DoD staff. That input and the committee’s own observations showed that a small subset of the grantees actively promote their research, and their work is well known in some national security circles. In some cases, moreover, service branch program managers have been proactive in raising awareness of Minerva research, mostly as ad hoc activities involving specific projects. However, the committee also found that there has been no systematic focus to date on disseminating information about the research funded through the Minerva program or on providing opportunities for the grantees to interact with policy makers or others who might be interested in the work.

As discussed, DoD only recently began developing a centralized database of the grants that have been awarded as part of the Minerva Research Initiative. At the time of the committee’s evaluation, there was no mechanism, other than word of mouth, for identifying relevant research or expertise, even when someone expressed an interest in consulting Minerva research or researchers on a particular topic. Therefore, as a first step toward broadening understanding of the program’s benefits, the Minerva

program office needs to prioritize the completion of this database. The database needs to be searchable and to include detailed information on the focus of each grantee’s research and the researchers’ areas of expertise. The value of the Minerva grants is not only in the research produced but also in the expertise of the researchers, and the database needs to enable the easy identification of relevant expertise whenever the need or opportunity arises for a briefing, input, or some other form of dissemination.

The database needs to be centralized, integrating information about all of the grants funded through the Minerva program from its inception, regardless of which service branch managed them. The database also needs to be widely accessible to everyone within DoD. A public-facing version of the database is needed as well, containing perhaps fewer administrative details about the grants, but sufficient information about the research and the expertise of the researchers to facilitate its broad use (see Chapter 5 and Recommendation 5.2).

RECOMMENDATION 3.3: The Minerva program office should make completing the centralized database of the projects and researchers funded under the Minerva Research Initiative a high priority.

In addition to developing this database, another priority for the Minerva program office is to formulate a more proactive approach to building relationships with leadership across DoD and others who could benefit from learning about the grantees’ work, both within the department and externally. Intentional outreach could not only increase the usefulness of the research produced under the program but also strengthen support for the program among stakeholders.

RECOMMENDATION 3.4: The Minerva program office should develop relationships with potential supporters of the Minerva Research Initiative and users of the research, both among Department of Defense leadership and externally, to increase awareness of the program and expand use of its funded research and the expertise of its grantees.

Process Improvements to Enhance the Grantees’ Experiences

Beyond improvements that would benefit all stakeholders in the Minerva program, the committee also identified improvements that would enhance the grantees’ experience. The committee identified these opportunities primarily from the responses provided to the grantee survey and the survey of administrators of sponsored research at academic institutions (see Chapter 2).

Comparison of Minerva and Other Grant Programs

Generally speaking, the great majority of the grantees who have had experience with NSF grants in addition to DoD’s Minerva grants reported being much more, somewhat more, or at least as satisfied with the characteristics of the Minerva program relative to the NSF grants (see Table 3-1). “Selection of important topics for research” stood out in particular as an area in which more than half of the grantee respondents were “much more” or “somewhat more” satisfied with Minerva grants than with NSF grants. However, it is important to note that some NSF funding opportunities do not specify predetermined topics as does the Minerva program, and that the thematic solicitations do not specifically target researchers focused on national security topics. This difference could explain why respondents to the grantee survey were particularly satisfied with the Minerva program in terms of the topic selection.

TABLE 3-1 Grantee Satisfaction with Aspects of the Minerva Program Compared with National Science Foundation Grants (percentages)

| Aspect | Much/Somewhat Less Satisfied (%) |

About the Same (%) |

Much/Somewhat More Satisfied (%) |

Unable to Compare This Aspect (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection of important topics for research | 10 | 37 | 54 | — |

| White paper process | 12 | 32 | 37 | 20 |

| Full proposal submission process and requirements | 12 | 56 | 29 | 2 |

| Communication during the proposal stage | 12 | 51 | 34 | 2 |

| Postaward grant management (e.g., incremental funding, modifications, no-cost extensions, compliance with terms and conditions) | 15 | 54 | 24 | 7 |

| Institutional review board requirements | 22 | 56 | 12 | 10 |

| Financial and narrative grant reporting requirements | 15 | 68 | 17 | 2 |

| Postaward communication | 15 | 37 | 44 | 5 |

| Assistance with dissemination or translation of research findings | 7 | 56 | 22 | 15 |

NOTES: Sample size = 41. Grantee survey Q4: “How satisfied are you with the following aspects of the Minerva grant program compared to National Science Foundation grants?”

The IRB process was the area in which the highest proportion (22%) of grantees said they found the DoD process much less or somewhat less satisfactory than the NSF process, although the majority of the grantees described their satisfaction with DoD and NSF IRB processes as “about the same.” The human subjects review process was also one of the most frequently noted challenges (mentioned by 12% of the grantees) when grantees were asked to list the challenges they face “in conducting unclassified research relevant to national security that are different from the challenges you face in conducting research in other areas.”

Grantees were also asked to compare their experiences with the Minerva program and those with DHS grants and grants other than Minerva from the DoD service branches. Comparisons with DHS grants showed patterns similar to those for NSF grants, but the number of grantees who had experience with both Minerva and DHS grants was too small to permit meaningful conclusions (n = 9). Not surprisingly given the similarities, the majority of Minerva grantees who also had experience with other grants from the DoD service branches were about equally satisfied with the two programs; very few were less satisfied with Minerva. It is interesting that a little over one in three grantees (37%) said they were much more or somewhat more satisfied with the “selection of important topics for research” in the Minerva program relative to other grant programs run by the service branches. The number of responding grantees who had experience with both Minerva and other service branch grant programs and who were therefore able to make these comparisons was relatively small (n = 19), and grantees who have received a Minerva grant are only a subset of those who have had experience with other grants from the service branches. However, this finding may be an indication that despite the challenges involved in reconciling the priorities of different DoD stakeholders, the collaborative Minerva program produces similar or better results relative to other service branch grant programs from the perspective of grantees. For detailed survey results, see Appendix E.

As discussed in Chapter 2, the committee also conducted a survey of administrators of sponsored research. This survey produced somewhat different results from the grantee survey in terms of comparisons with other grant programs (see Appendix F for detailed results). The number of respondents to this survey who had experience working with the Minerva program was small (11 of 88 respondents who completed the survey), and because the committee anticipated this, respondents to the administrator survey were also asked to compare DoD grant programs in general with NSF and DHS grant programs.1

___________________

1 The grantees were asked to compare their satisfaction with the grant programs, while the administrators of sponsored programs were asked to compare the extent to which various aspects of the grant programs were more or less challenging (see Appendixes E and F, respectively, for the wording of the questions).

TABLE 3-2 Comparison of Aspects of DoD Grant Programs in General and National Science Foundation Grants by Administrators of Sponsored Research

| Aspect | Much/Somewhat More Challenging (%) | About the Same (%) | Much/Somewhat Less Challenging (%) | Unable to Compare This Aspect (%) | Skipped |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposal submission process and requirements | 75 | 14 | 5 | 6 | — |

| Communication during the proposal stage | 51 | 32 | 8 | 10 | — |

| Postaward grant management (e.g., incremental funding, modifications, no-cost extensions, compliance with terms and conditions) | 72 | 16 | 5 | 6 | — |

| Financial and narrative reporting requirements | 58 | 28 | 5 | 9 | — |

| Postaward communication | 56 | 30 | 4 | 9 | 1 |

| Other award characteristics (e.g., indirect costs) | 47 | 46 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

NOTES: Sample size = 79. Survey of administrators of sponsored research Q8: “How do the following aspects of DoD grant programs in general compare to NSF grants?”

In general, respondents to this survey were less likely than grantee respondents to compare aspects of the DoD grant process favorably with aspects of the NSF process. For example, 75 percent described the DoD proposal submission process and requirements as much more or somewhat more challenging relative to NSF grants, and 72 percent said the same about postaward grant management. Most respondents rated the key characteristics of DoD and DHS grants about the same. Tables 3-2 and 3-3, respectively, summarize the comparisons of DoD and NSF and DHS grants.

When asked about the changes they would like to see to the Minerva program, four respondents to the survey of administrators of sponsored research provided comments that indicated a need for increasing awareness about the program and providing additional detail on how the program works. In terms of changes to DoD grant programs in general, the most frequently volunteered open-ended responses were related to the standardization of procedures (reporting and administrative requirements) across the department’s various grant programs and the need to improve the DoD online systems used for the management of the grants.

TABLE 3-3 Comparison of Aspects of DoD Grant Programs in General and Department of Homeland Security Grants by Administrators of Sponsored Research

| Aspect | Much/Somewhat More Challenging (%) | About the Same (%) | Much/Somewhat Less Challenging (%) | Unable to Compare This Aspect (%) | Skipped |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposal submission process and requirements | 15 | 48 | 19 | 17 | 2 |

| Communication during the proposal stage | 11 | 56 | 11 | 20 | 2 |

| Postaward grant management (e.g., incremental funding, modifications, no-cost extensions, compliance with terms and conditions) | 15 | 54 | 13 | 17 | 2 |

| Financial and narrative reporting requirements | 13 | 52 | 13 | 20 | 2 |

| Postaward communication | 11 | 56 | 11 | 20 | 2 |

| Other award characteristics (e.g., indirect costs) | 9 | 59 | 11 | 19 | 2 |

NOTES: Sample size = 54. Survey of administrators of sponsored research Q9: “How do the following aspects of DoD grant programs in general compare to Department of Homeland Security grants?”

Human Subjects Review Requirements

One area in which changes would notably improve the grantee experience is the human subjects review process. Currently, studies often require approval by the IRBs of both the service branch managing the grant and the grantee’s home institution. In the case of grants with more than one PI, several academic institutions may be involved. The service branches each have their own rules about the human subjects review process, and grantees are encouraged to work with the service branch program manager overseeing their project to navigate the process. AFOSR does not release funds until IRB approval has been obtained. Projects managed by ARO can receive funds that do not involve human subjects research prior to obtaining IRB approval for the portion of the work that involves data collection, and the ARO Human Research Protections Office reviews the IRB approval obtained by PIs from their academic institutions for compliance with ARO standards. ONR does not require separate review by the ONR

IRB either, and instead reviews the approval obtained by grantees from their own academic institution. This model imposes the least burden on the grantees while ensuring that the necessary human subjects protections are in place and providing DoD with an opportunity to identify any potential issues of concern.

In principle, NSF also requires IRB approval before an award is made, but exceptions are possible if preliminary work needs to take place before the research protocol has been finalized. In these cases, the grant can be set up in a way that permits some work, with the exception of data collection, to begin before IRB approval (National Science Foundation, 2014, p. II-30).

Information obtained from the interviews with DoD staff and the responses to the grantee survey suggest that the human subjects review procedures of some of the service branches place an extra burden on the grantees and delay the start of work. Perhaps this issue could be addressed by developing, to the extent feasible, common procedures that would apply to all Minerva grants, regardless of which service branch is overseeing them. A combination of the ONR, ARO, and NSF approaches could result in a reasonable compromise that would facilitate the grantees’ work. Providing funding for some preliminary work that does not involve data collection prior to IRB approval appears especially reasonable.

The revisions to the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (also known as the Common Rule) that began taking effect in 2018 and are being introduced in several phases require “U.S.-based institutions engaged in cooperative research to use a single IRB for that portion of the research that takes place within the United States.”2 This change appears to be applicable primarily to multisite projects, but the underlying intent is to reduce the overall challenges associated with navigating the review process for studies that require approval by multiple IRBs. DoD could also consider having one IRB of record for the Minerva grants.

RECOMMENDATION 3.5: The Department of Defense (DoD) should reduce the burden and project delays associated with the human subjects review process for Minerva grants by using a single Institutional Review Board (IRB) of record for each grant. For example, the IRB of record could be that of the principal investigator’s academic institution, with DoD reviewing that approval. DoD should also consider releasing funds prior to IRB approval for portions of the work that do not involve human subjects research.

___________________

2 Available: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2017-01-19/pdf/2017-01058.pdf.