The objectives of the workshop’s second session, Clarion Johnson explained, were to examine approaches, policies, and models for multi-sectoral engagement, and the goal was to identify barriers to engagement and opportunities for facilitating more effective models (see Box 5-1). Session moderator Mary Lou Valdez further elaborated that the session would review organizations (World Bank Group, PATH, UNICEF, and WHO) representing a wide range of approaches to gain an understanding of their motivations and perspectives in engaging with multi-sectoral models as well as the challenges and barriers these organizations have encountered in developing and implementing these models. These challenges would be reviewed with two goals: finding ways to mitigate them and identifying opportunities to raise organizational competence.

This session had two panels. The first panel reviewed organizational approaches to multi-sectoral engagement from the World Bank Group, PATH, UNICEF, and WHO. The second panel explored models of multi-sectoral engagement that have successfully created value for both private- and public-sector partners. The second panel also focused on initiatives that have developed and distributed medicines for global health. These initiatives included MMV; Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi); Novartis’s efforts to enable access to essential medicines; and the advance purchase commitment (APC) offered by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi) for an Ebola vaccine. This chapter summarizes the discussions of both panels.

ORGANIZATIONAL APPROACHES FOR MULTI-SECTORAL ENGAGEMENT

World Bank Group

Large gaps in coverage of essential health services exist in many countries, particularly for poor and marginalized populations, noted Olusoji O. Adeyi, director of Health, Nutrition, and Population Global Practice at the World Bank. His comment referred to both the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation (IFC)—the World Bank’s private-sector wing. Half of the world’s population cannot access needed health services, and roughly 100 million people fall into extreme poverty each year because of health expenditures (WHO, 2017). In addition, because approximately 800 million people spend at least 10 percent of their household budget on health expenditures (WHO, 2017), they often have to choose between health and other needed expenses for their families. Even in places where health services are available, they are not always high quality—as demonstrated by recent reports from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine;1 WHO; the World Bank; and the Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems in the SDG Era2 (on which Adeyi served as a commissioner).

Adeyi explained that these problems are addressed by the World Bank’s dual missions of eliminating extreme poverty and fostering shared prosperity. The World Bank enables countries to make faster progress toward achieving UHC, which includes quality health care coverage, financial protection, and multiple dimensions of equity. The IFC focuses on health service provision, including core engagements and initiatives to improve health care quality through the cooperation of regional generic pharmaceutical manufacturers, pharmaceutical retail and supply chains, and providers of medical devices and equipment. The World Bank also focuses on supporting public policies that further these objectives through both public and private means. Engaging the public and the private sectors simultaneously is important because both markets and governments can fail. To cover both bases, the World Bank focuses on developing durable country institutions and sustainable business models.

The World Bank uses a “systematic country diagnosis” to inform its country partnership framework, which delineates its engagement with each country over a period of about 3 years. According to Adeyi, in the health, nutrition, and population sectors, the World Bank had 111 opera-

___________________

1 To access the report Crossing the Global Quality Chasm: Improving Health Care Worldwide by the National Academies, visit https://www.nap.edu/25152 (accessed August 7, 2019).

2 To access the Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems in the SDG Era, visit https://www.hqsscommission.org/who-we-are (accessed August 7, 2019).

tions and $14 billion in country-level commitments as of the date of the meeting, and those statistics continue to grow. A core criterion for engagement, as well as a central challenge to overcome, is the grounding of the organization in the operational realities of the countries—which includes understanding that the countries may be constrained by specific economic and political dynamics.

Adeyi concluded by describing the Affordable Medicines Facility—malaria (AMFm) innovation, a PPP that focused on expanding access to affordable antimalarial medications, covered eight countries, and was one of the largest experiments in global health. It was found to be highly successful according to an independent evaluation published in The Lancet in 2012. However, that success challenged the traditional architecture of development assistance for health and for malaria medicines, and the failure of that assistance is what necessitated AMFm in the first place. The political dynamics were such that powerful constituencies on the board of the Global Fund opposed the expansion of AMFm and caused its subsequent “integration” into the Global Fund’s more traditional grant-making activities. In reflecting on this example, Adeyi emphasized the importance of determining whether scientific evidence really informed development assistance and the global development of health systems or whether political interests and the convenience of powerful constituencies were the dominant factors.

PATH

In her opening remarks, Mona Byrkit, managing director of Global Engagement at PATH, noted her presentation would focus on PATH’s activities in the Greater Mekong Subregion of Asia and on its PPPs. PATH is a 41-year-old global health organization that operates in 70 countries. It is composed of a global team of innovators, including health engineers, doctors, information technology experts, and community representatives who work to eliminate health inequities so that people, communities, and economies can thrive. PATH has worked in Vietnam for 38 years and has been interested in PPPs since its inception. It has worked with corporations to bring new technologies to countries.

According to Byrkit, PATH has been successful because of its ability as a nonprofit organization to build trust between the public and private sectors. PATH initially focused on reproductive health and brought new technologies regarding development of state-of-the-art condoms to countries in Asia. The organization then expanded its work to other contraceptive technologies and saw that their approach of connecting private-sector technologies and innovators with government public health programs was very effective. PATH then sought to engage the private sector in

Vietnam on other issues, including control of TB and HIV. At the same time, it also tried to engage the government to promote the idea that working with the private sector would strengthen the country’s overall health system.

Byrkit next described the Health Markets Project, which is a partnership among PATH, PEPFAR, and USAID that focuses on HIV prevention and care. The program was necessitated by the 250,000 people in Vietnam who were living with HIV. Although this was less than 1 percent of Vietnam’s overall population, the prevalence was proportionally higher in populations that included female sex workers, people who inject drugs, transgender women, and men who have sex with men. A recent study in Ho Chi Minh City, noted Byrkit, indicated that approximately 18 percent of transgender women in the city are HIV positive. However, a very strong national program had reduced new infections (since the height of the epidemic in the 2000s) by more than 40 percent. Although the program was government-led, it was largely funded by international donors who had begun reducing their investment in 2009 and 2010 because Vietnam had reached middle-income country status.

According to Byrkit, as other philanthropies and NGOs reduced their investment in Vietnam’s HIV initiative, the government retained its ambitious public health goal of eliminating HIV by 2030. That goal created an opportunity for PATH’s Healthy Markets Project, which was specifically designed to engage private-sector partners from different industries to communicate about HIV to increase demand for services and to increase the private-sector supply of HIV goods and services. As Byrkit highlighted, PATH had historically used a shared-value model and had worked with companies of all types and sizes to help them identify why they wanted to work in the country and to find shared common goals in terms of societal needs. Byrkit noted that the Healthy Markets Project is a shared-value approach.

Byrkit next outlined, based on the experience of PATH’s team, some of the steps a nonprofit may want to take if it seeks to partner with the private sector. First, nonprofits could do their own market research to identify private-sector partners that are likely to align with their goals. Some questions to ask could include, “Where are people going for their goods and services? How much are they willing to pay for services and goods, and are they able to pay?” She also suggested starting with a few potential partners to avoid spreading too thin. PATH has its own internal due diligence process to vet corporations to determine whether PATH wants to be publicly aligned with the companies and what the potential risks of alignment might be. She noted that nonprofits sometimes have an aversion to collaborating with groups that put profit motives first, but that is changing.

Currently, the Healthy Markets Project is partnering with private-sector entities on both commodities and services. Byrkit explained, for example, that many local condom manufacturers historically manufactured only for export because donors provided so many free or subsidized condoms through NGOs such as PATH that local companies had no incentive to sell to the Vietnamese market. PATH worked with these companies to help them understand that a huge market potential may exist within Vietnam because NGOs were reducing support for existing programs. PATH also helped them consider what marketing tools might work based on PATH’s previous marketing experience. PATH worked with major manufacturers and distributors of drugs and diagnostics who wanted to enter the Vietnamese market to help them understand how to become licensed, how to show a successful pilot, and how to contribute to the overall HIV program. In addition, PATH worked with traditional and nontraditional distributors and retailers.

On the services side, PATH worked with the Vietnamese government on a total market approach, which allowed the government to act as a steward to help private-sector actors expand their reach. The result was that private clinics were created, and they offered quality, low-cost services that included HIV testing, self-testing, and lay-provider testing.

Still, Byrkit noted that PATH has faced challenges related to interest misalignment between partners, slow rates of coalition and partnership building, and perceptions of bias (e.g., that PATH receives compensation for aligning with a particular company or product). Governments have been skeptical of PATH’s motives, and, sometimes, companies have been hesitant to share data that governments could use to understand the effects of products and services on communities. To address perceptions of bias, PATH emphasizes with all partners that its focus is both to expand choices and to lower prices in the overall market.

Byrkit noted that some donors, such as USAID, appreciate PATH’s shared-value approach, but others remain hesitant to adopt it. Still, the public health impact of PATH’s partnerships and initiatives has been undeniably effective: thousands more cases of TB have been diagnosed, and more people have gained access to family planning. Additionally, according to Byrkit, more than 100,000 people have been tested for HIV through private testing, lay testers, or self-testing. As a result, more than 4,000 cases of HIV have been diagnosed, and more than 90 percent of these people have received treatment. Such partnerships are important for helping the Vietnamese government reach its goal of eliminating HIV by 2030.

United Nations Children’s Fund

Oren J. Schlein, senior adviser of Global Philanthropy at UNICEF, explained that UNICEF’s work covers a broad spectrum from birth to adulthood, and its goals include child survival; education; child protection from exploitation and violence; safe and clean environments; and equity. Because health drives a large part of its work, nearly half of the organization’s $5 billion budget is spent in the broader health space.

Schlein noted that UNICEF broadly defines the private sector as including business, foundations, philanthropists, and individuals who give small contributions to the organization. However, the business sector and foundations have been recognized as the central private-sector actors needed to achieve organizational change and results for children.

UNICEF evaluates potential partnerships through three lenses: income, influence, and expertise. Schlein noted that during the past 10 to 15 years, UNICEF has primarily focused on financial partnerships. However, recently, shared-value partnerships have become more prominent, and UNICEF has recognized reasons to work with business, industry, and foundations that extend beyond funding. According to Schlein, the technical expertise UNICEF can obtain through partnerships with private-sector actors is often more valuable than the money itself. Additionally, the organization emphasizes engagement with business across all of UNICEF’s 150 country offices because the cost of not engaging with business can be significant and is not an option for UNICEF. In total, UNICEF has about 50 global corporate partners; 150 large national partners in the countries where UNICEF operates; and many other small and medium partners in program countries. UNICEF engages with the private sector mainly because engagement can have a broad and significant impact on children. Child rights is a topic central to UNICEF’s mission, and actions of businesses in the workplace, marketplace, and community can have profound consequences for children. UNICEF has seven elements of shared value that it uses to examine prospective partnerships: core business and assets, reach, influence, income, child rights and business, procurement, and innovation.

In one example of an effective partnership, Schlein described how UNICEF partnered with a French company 10 years ago. The company made ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), a product used in emergencies to address severe and acute malnutrition. UNICEF wanted to deliver supplies to Africa and to Asia, but the company was unable to deliver supplies quickly enough to address the needs of the target population. As a result, UNICEF worked through colleagues in their supply division to outsource the technology and to take it to markets in Africa and

Asia. Most RUTF that UNICEF uses is now locally produced in the target region. Schlein saw this as a positive example of a shared-value partnership and as a way that UNICEF could support both local communities and local industry.

Next, Schlein provided an example of partner engagement through UNICEF’s collaboration with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Although this is not a private-sector engagement, Schlein believes that foundations are integral to multi-sectoral engagement. UNICEF has worked with the Gates Foundation to address polio for about 20 years. Recently, the two organizations launched a new partnership that outlines a more intentional way of working together in order to deliver significantly better results for children and their families. With the new partnership, UNICEF and the Gates Foundation are moving away from the traditional grantor/grantee partnership model to one that is mission-aligned, strategic in focus, and designed to break down silos across and between both organizations.

As part of this new partnership, UNICEF and the Gates Foundation have a shared goals and partnership framework (see Figure 5-1). The partnership is grounded in primary health care and focuses on nutrition, early childhood development, and adolescent well-being. In developing their shared framework, the organizations considered questions such as the following: “How do we work together to strengthen systems and the country? How do we unite to deliver better results for children? How can we innovate together, advocate, and learn?” Schlein noted that the goal

SOURCE: As presented by Oren Schlein on November 15, 2018.

was for the two partners to identify important learnings to share with the broader ecosystem of partners and not just to collaborate technically. Schlein highlighted the proposed goal of strengthening and supporting the global ecosystem; this goal was developed to inform the broader global health community.

In establishing the partnership between UNICEF and the Gates Foundation, many conversations about how to engage business at the global and the domestic levels occurred. The two organizations agreed on a set of partnership principles: One principle is co-creation, which involves incorporating the best insights and technical knowledge. Another central principle is co-investing, which means that both organizations contribute cash and in-kind funds to the initiative. A third important principle is building one communication narrative, which means both partners recognize that they have strong brands and that they can better influence policy at country and global levels by working together.

Schlein ended his presentation by sharing a quote from UNICEF executive director Henriette Fore: “[We are committed] to deepen[ing] our partnerships with business and tap[ping] into their innovations, ideas, and market reach to achieve results for children.” He added that Fore understands that UNICEF needs business to not only provide funding but also contribute to solutions by identifying market opportunities, innovating, and developing new ways of collaborating.

World Health Organization

Building on Singer’s earlier presentation, Gaudenz Silberschmidt, director for Partnerships and Non-State Actors at WHO, focused on WHO’s approach for enhancing multi-sectoral engagement based on the FENSA.3

Silberschmidt noted that although Brink proposed in an earlier session the necessity of equitability between private- and public-sector partners, the 194 member states of WHO do not consider themselves to be on equal footing with the private sector because WHO is constrained by the boundaries of its role as an intergovernmental organization. Because WHO is a regulatory agency, private-sector partnerships are required to have clear rules of engagement and address global health challenges with limited funding. WHO’s budget of $2.5 billion is relatively limited for an entity working with 194 countries on a global scale; it is less than the $3.7 billion health budget of the District of Columbia or of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

___________________

3 To view WHO’s Framework for Engagement with Non-State Actors, visit http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/wha69/a69_r10-en.pdf (accessed August 7, 2019).

WHO’s decision-making body is the World Health Assembly, consisting of 194 Member States and the 34 members of the Executive Board. Silberschmidt emphasized that WHO’s constitution, developed in 1946, is visionary and directs the organization to engage with all parts of society. WHO uses the term “non-state actors” in its partnership framework to include all nongovernmental entities such as NGOs and the private sector (WHO, 2016). WHO hosts joint programs, such as Tropical Disease Research, UNAIDS, and the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. WHO also acted as an incubator of partnerships such as the Global Fund, Gavi, Rollback Malaria, and Stop TB. In addition, WHO has hosted partnerships such as Unitaid, which is an initiative related to maternal, newborn, and child health that includes more than 700 non-state actors. The organization also belongs to more than 100 partnerships and collaborative arrangements and has more than 700 collaborating centers in academic institutions and government, 214 non-state actors in official relations, and thousands of individual engagements.

According to Silberschmidt, WHO has accepted in-kind contributions from companies such as Merck and Novartis and has received 1.2 billion tablets of medication for neglected tropical diseases through private-sector donations. Silberschmidt noted that WHO’s previous director-general successfully solicited donations from 11 pharmaceutical companies for diseases where no market existed because the patients are too poor.

As mentioned in Singer’s presentation, WHO’s Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework allows manufacturers to receive the influenza strains they need from WHO in order to produce their products. In response, through an intergovernmentally negotiated framework, these companies provide $14 million per year for technology transfer and capacity building to support greater vaccine production in primarily middle-income countries.

The Meningitis Vaccine Project, Silberschmidt noted, is another example of a WHO partnership with innovative funding. The initiative involves philanthropy, NGO, government, and private-sector partners.

FENSA is WHO’s overarching partnership framework, defines its rules of engagement, and applies evenly to NGOs, the private sector, philanthropic foundations, and academic institutions (WHO, 2016). It was adopted in 2016 after more than 200 hours of intergovernmental negotiation and was approved by member-state consensus. According to Silberschmidt, FENSA tries to balance the needs of industrialized country governments that seek stronger engagement with industry with those of the governments of LMICs, which generally want better protections against undue influence. FENSA provides protection when member states do not agree with WHO’s partnerships. It also allows for other WHO

negotiations that have become stuck in conflicts over engagement processes to progress.

Silberschmidt noted that challenges still remain among member states despite FENSA. At times, FENSA can be too detailed. In addition, while FENSA defines the rules of engagement for partners, strategies for engagement between partners are still necessary and need to be defined. Silberschmidt concluded by emphasizing that WHO is committed to strengthening engagement in order to reach the triple billion targets of its 13th General Programme of Work, which Singer mentioned previously.

DISCUSSION

As session moderator, Valdez opened the discussion by asking speakers for their suggestions about how to raise confidence and comfort levels with public–private engagement and how to expand the reach of public–private collaborations. Silberschmidt stated that WHO’s most significant challenges are generating understanding about the roll-out of FENSA and defining strategies for engagement. Another challenge is ensuring WHO’s staff is able to take risks and to engage with other sectors. WHO is building a strategy to encourage increased engagement, and it is working with the United Nations Foundation to develop recommendations for how to better engage with the private sector.

Byrkit added that she thinks communication and “speaking the same language,” both literally and figuratively, is very important to building trust. Having a partner or a party that can explain terminology and literally translate language can be helpful. Regarding one of PATH’s projects with the government of Vietnam, she emphasized PATH’s role in reassuring the government that it would still be the overseer and steward of the overall health system. PATH also helps explain the role of private-sector actors to the government, and it outlines the ways sectors can achieve mutual goals through partnerships.

Schlein agreed that forging trust takes time, and partners need to understand that any meaningful collaboration may take months or years to develop. He noted this is the case for business and foundation partnerships with UNICEF. Schlein also acknowledged the importance of brokers and partnership leads who, especially in UNICEF’s case, bring different skill sets to collaborations and are important for navigating the subtleties of partner relationships.

Adeyi responded with five points to Valdez’s question about how to better raise confidence and change the culture. First, he suggested making extra effort to communicate clarity of purpose. He also noted the importance of clarifying which partners make decisions and which benefit from

decisions; people who may lose something as a result of a partnership are typically more motivated than people who may gain. He also suggested that public health stakeholders become more familiar with the language of business and markets. Next, Adeyi noted that scaling an initiative is more challenging politically and requires different skill sets than setting up an initial pilot. Finally, Adeyi reiterated his earlier point about the necessity of paying attention to the counterfactual, or the comparison. If an initiative is imperfect, the common assumption for the counterfactual is perfection; however, in actuality, the counterfactual could be much worse than the imperfect initiative.

A participant commented that, overall, the session focused on changing from one system to another system and asked the speakers which aspect of the change process happened first: Did leaders make decisions, and actions then followed? Or did actions happen first, and policies were then developed to encourage them? Schlein responded that the process depends on the organization and its experience. At UNICEF, the process starts with actions because the organization has a long history of engaging with a broad range of private-sector actors. UNICEF also enables deep conversations with leadership from the food and beverage industry, and those conversations subsequently influence its actions.

Silberschmidt responded by noting that NGO principles were so controversial when they were first introduced at the World Health Assembly in 1948 that they were not adopted. In 2000, the WHO director-general Gro Harlem Brundtland, former prime minister of Norway, wanted to establish private-sector engagement guidelines, but they were not brought to the World Health Assembly because its executive board decided the guidelines were also too controversial. These and other failed attempts to institute guidelines led to the FENSA negotiations. WHO now focuses on implementing FENSA, and education about how to engage with government and with intergovernmental organizations is needed within the private sector. Mutual learning of how each partner functions is essential for forging and operating successful partnerships. Silberschmidt also addressed the misconception that the only people who are needed to work in the health field are doctors and emphasized how people with other skill sets, including partnership and business expertise, are also needed.

A participant asked for examples of how UNICEF and WHO have been able to develop a solution with the private sector that has been replicated—either elsewhere in the same country or in another country. Schlein responded that UNICEF has collaborated for a long time with Unilever around wash initiatives in South Africa and has also collaborated with Tata Global Beverages in India. He noted that many examples of the organization’s collaborations with business, including both large

and small companies in Africa and in Asia, demonstrate effective shared-value relationships.

Adeyi added that, in Ecuador, the World Bank partnered with the corporation Fybeca, which operated a high-end pharmacy chain that increased access to affordable, high-quality medications by establishing a second chain of pharmacies that enabled poor customers across the country to purchase such medicines and toiletries at reduced prices. As a second example, Adeyi described the World Bank’s support of a managed equipment scheme in Kenya that removed the burden of fixing equipment from doctors by changing from purchasing to leasing agreements. In this initiative, the leasing company manages the risks and controls the equipment installation and maintenance. The IFC and World Bank partnered with the Kenyan government and with General Electric to make these diagnostic services more readily available.

Monahan asked the speakers to elaborate on the brokering function and to specifically address how to understand brokering subtleties within partner relationships. Furthermore, he asked about who owns the brokering function—whether it is the role of each organization or whether external brokers could facilitate more partnerships in the global community. Schlein responded that the brokering function within UNICEF is deemed an essential part of the success of any partnership negotiation. UNICEF has a global division in Geneva and in New York called the Private Fundraising and Partnerships Division, which has 200 employees, and it formulates guidelines and manages partnerships. In addition, UNICEF has national committees, which are nationally registered charities that act as front-facing interlocutors for private-sector partners.

Schlein explained that UNICEF only engaged the private sector at the global level in high-income countries until 10 years ago. Now, with growth in emerging markets and in middle-income countries, 24 of 150 country offices have a formal mandate to engage with the private sector. There is also a growing recognition that technical experts cannot do the work alone. He elaborated by noting that the collaboration with the Gates Foundation, which he previously described, took almost 2 years of engagement with more than 200 colleagues across both organizations to define what the collaboration needed to look like. Schlein said, “You can have the best minds, the best doctors in the world, but unless you know how to fix the problem and have the right kind of conversations, you’re not going to get there.”

Adeyi also responded to the question about brokers by looking at reverse engineering some of the successes. Referring to AMFm, he noted that the pharmaceutical company agreements were established as a result of leadership, vision, and willingness to take risks. He suggested that enti-

ties may want to become more comfortable with and willing to engage in tough and constructive conversations with Big Pharma, and he stated that when “you’re willing to engage in very tough, challenging discussions, you really go to the evidence, you really go to the substance, you can actually get a partnership that works.” Such approaches, he noted, led to the multi-party creation of AMFm, which was hosted by the Global Fund. He also cautioned that new players in health systems development may experience pushback on successful new business models because they erode the dominance of deeply entrenched and under-performing traditional models.

Byrkit responded that all of the panelists and the other development partners in LMICs need to play the role of brokers, and she noted that PATH has specifically played this role for the past 41 years. She also reiterated that development partners leave as countries develop, and, therefore, it is important for governments to learn how to speak with the private sector and for the private sector to understand how to converse with state actors.

Sir George Alleyne pointed out that the speakers in this session discussed how their organizations interact with outside entities and that these interactions urgently need to be written down and categorized as a way to address a particular challenge: lack of trust. He mentioned that FENSA may, in fact, be the reaction of a group of member states to their lack of trust in WHO, and he saw trust as fundamental to the interaction between organization and other sectors.

Alleyne also commented on Adeyi’s earlier discussion about the five components of a successful partnership, and he posited that only three items are essential to establishing partnerships: mutuality of interest, specificity of purpose, and a shared sensibility of the resources to be brought to the table. He also suggested that the word “donor” not be used in the context of a shared-value partnership. All entities need to be called “partners” because even those that donate funds still benefit.

Another participant commented that they were one of the four people involved in starting the Global Business Coalition on HIV/AIDS. They noted that in mobilizing the business sector to respond to the disease, they also recognized a need to mobilize government, NGOs, and other partners to help them understand what business could do. In communicating with these stakeholders, the Global Business Coalition became a type of broker between the business community and other sectors that multiple entities could trust. In doing so, the Global Business Coalition was able to identify opportunities that individual partners were unable to identify on their own. The participant also noted that partners included mining and pharmaceutical companies as well as nontraditional private-sector

partners that focused more on social determinants of health. They suggested that creating a partnership advisory or review board on a global or a country level, similar to an Institutional Review Board for research, may be beneficial. This new entity could consider conflicts of interest, opportunities, and pitfalls and could offer advice on how to accelerate initiatives through partnerships.

MODELS OF MULTI-SECTORAL ENGAGEMENT AND VALUE CREATION

As session moderator, Seema Kumar, vice president of Innovation, Global Health, and Science Policy Communication with Johnson & Johnson, explained that the goal of this session would be to examine several models of multi-sectoral engagement that have successfully created value for partners in both the private and public sectors. She would then highlight common themes and engage participants in conversation. Presenters for this session would include representatives from MMV, DNDi, and Novartis.

Medicines for Malaria Venture

MMV is a global R&D product development partnership (PDP) that combines academic, scientific, and pharmaceutical expertise, explained Wiweka Kaszubska, vice president of product development at MMV. Its mission is to reduce the burden of malaria in disease-endemic countries by discovering, developing, and delivering new, effective, and affordable antimalarial drugs to prevent and cure infection. Its ultimate goal is disease eradication.

When MMV was founded in 1999, approximately 300 million cases of malaria occurred each year, and 1 million deaths were attributed to malaria annually. That represents more than the number of current cases and twice as many deaths. Therefore, at the time, treating malaria and developing new therapeutic options was a medical necessity. Since its inception, MMV and its partners have developed and distributed several new antimalarial medicines. In addition, the organization now manages the largest portfolio of antimalarial R&D and access projects.

Initially, MMV was funded under the umbrella of WHO’s Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) and was seeded with $4 million from the governments of the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, as well as from the World Bank and The Rockefeller Foundation. At the time, the drug development pipeline was empty.

Today, MMV’s underlying principle is to partner with entities that share its commitment to developing new antimalarial medications and providing access to them in the developing world. MMV’s organizational model, explained Kaszubska, includes five pillars: syndicated investment, including by government and philanthropies; partnerships; the drug pipeline, which is core to their mission; independent expert scientific review; and a strong contractual framework. MMV offers added value to their partners through

- intellectual property in drug development in the form of patents or patentable material, expertise, and research tools;

- independent scientific and access expertise through MMV’s network of PPPs and through MMV’s External Scientific and Access and Product Management Committees;

- in-house scientific and access expertise (more than half of its staff has extensive experience in pharmaceutical development and/or delivery in the public and private sectors);

- financing through diverse, syndicated funding sources; and

- incentive schemes, accelerated regulatory review, and a Priority Review Voucher from FDA—all of which offer substantial financial rewards.

Kaszubska noted that MMV’s intellectual property model is central both to their operation and to their success. MMV provides for transferability and exclusivity of intellectual property rights as a mechanism to ensure that quality, safety, and public health goals are met. MMV’s work always begins with a legal agreement with the drug development partner that specifies the process and time line, which could take from 10 to 15 years to receive the first registration and another 5 years to gain access. MMV also works to ensure that drugs will be affordable. Kaszubska noted that sufficient quantities of medications are necessary for the public sector. If partners are unable to deliver on their commitments, the ownership and rights of the product revert to MMV so that another partner can be approached.

Regarding governance, MMV uses joint project teams that communicate regularly and execute projects according to an agreed plan and budget. While a legal contract forms the basis of the agreement, it is not a substitute for strong and collaborative partnerships because positive human relationships, noted Kaszubska, are essential in this process.

Regarding funding, Kaszubska explained that pharmaceutical companies typically match every pound MMV donates and provide even more in-kind contributions. With respect to the drug development pipeline,

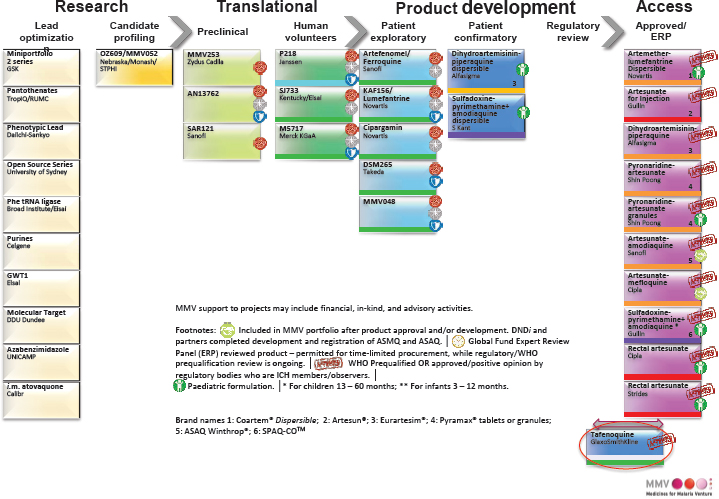

MMV has made significant progress: Figures 5-2 and 5-3 compare the pipeline in 1999 when MMV was founded with the pipeline in Q3 of 2018.4 All of the approved medication products in the far-right column of Figure 5-3 are leading to visible, measurable success in terms of human lives saved. MMV has estimated that more than 1.5 million lives were saved by the end of 2017 thanks to successful partnerships.

SOURCE: As presented by Wiweka Kaszubska on November 15, 2018.

SOURCE: As presented by Wiweka Kaszubska on November 15, 2018.

___________________

4 At the time of the November 2018 workshop, Q3 of 2018 represented MMV’s most up-to-date portfolio.

Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative

Rachel Cohen, the regional executive director of the DNDi, noted that her presentation would cover the DNDi model, which she emphasized has a different history and different associated experiences than some of the other models previously presented.

DNDi is a collaborative, nonprofit, virtual drug R&D organization that is driven by patient needs. It develops new treatments for neglected diseases, most of which fall outside the scope of market-driven R&D. DNDi also focuses on shifting the R&D landscape for neglected diseases toward a needs-driven system by advocating for enhanced political leadership, sustainable financing, and sound public policies. With the goal of sustainability in mind, DNDi works to strengthen research capacity in LMICs by maintaining and building R&D platforms, promoting regionally driven initiatives, facilitating patient access to treatment, supporting training for R&D efforts in-country, and transferring technology to local manufacturers.

DNDi was founded by Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and five public-sector research partners: Kenya Medical Research Institute, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Brazil, Indian Council of Medical Research, the Malaysian Ministry of Health, and the Institut Pasteur in France. In addition, WHO TDR serves as a permanent observer. The leaders of these organizations continue to sit on the governing board of DNDi and make key decisions about its strategic direction.

Cohen explained that DNDi grew out of the frustrations that MSF clinicians experienced in the field during the mid- to late 1990s when the tools they needed to treat patients did not exist because of factors such as prohibitive costs to access treatments; resistance to or toxicity of existing treatments; and a lack of existing research on treatments for particular diseases.

For example, one of the diseases to which DNDi was initially founded to respond to is called Human African Trypanosomiasis, or African Sleeping Sickness, which is currently heavily concentrated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The disease, transmitted by the bite of the tsetse fly, claimed hundreds of thousands of lives between the 1970s and the 1990s, as well as millions of lives during prior centuries. Cohen explained that the only tool to treat the disease at the time was a drug called melarsoprol, a toxic arsenic derivative that killed 1 in 20 patients and was extremely painful to inject.

As of the date of the workshop, explained Cohen, DNDi had delivered seven new treatments for five diseases.5 Each treatment was easier to

___________________

5 As of 2019, DNDi has delivered eight new treatments for five diseases (DNDi, 2018).

use than prior therapies, and it was more affordable, better field-adapted, and non-patented. Within countries, DNDi works in very close partnership with ministries of health, local clinicians, and local communities to define target product profiles, conduct clinical trials, and accelerate the implementation of new treatments. At the earlier end of the R&D pipeline, DNDi works virtually and relies largely on the private sector, where the capacity to discover and develop drugs has historically been concentrated, and on academic institutions. Over the years, DNDi has expanded from focusing on 4 diseases to 8 diseases—with nearly 40 new potential treatments in the pipeline.

While DNDi has many funding partners, the organization has a set of policies regarding from whom it will accept financing. DNDi strives to maintain balance between public and private resources; about 50 percent of its funding comes from the public sector, and 50 percent comes from the private sector. Cohen noted that, to protect against undue influence, the organization does not allow any single donor to provide more than 25 percent of DNDi’s overall funding.

Next, Cohen explained the concept of de-linkage, which is an alternative way of thinking about financing and incentivizing R&D that does not rely on high prices (or volume-based sales) to recoup R&D investments. She noted the intellectual property system does not always incentivize the right kind of innovation, and it can lead to high prices that create barriers to access. De-linkage “de-links” the cost of financing R&D from the price of products and volume-based sales.

DNDi has incubated and helped launch the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP). This partnership is a new, joint initiative between WHO and DNDi that was created to apply some of the lessons DNDi has learned, after 15 years of experience, to research on antimicrobial resistance. GARDP will focus on four issues: neonatal sepsis, drug-resistant gonorrhea and other sexually transmitted infections, memory recovery and exploration, and pediatric antibiotics.

Concluding her presentation, Cohen provided some questions for consideration:

- Should the model of PDPs in general, or of DNDi and GARDP in particular, be limited to areas where an obvious market failure exists? Are there lessons for other areas of public health importance?

- What is the role of the PDP approach? While others might describe DNDi’s PDP approach as focused on reformulating existing drugs, DNDi could argue that they have been functioning with more of a bench to bedside end-to-end approach.

- What types of incentives and financing policies need to be put into place? Are the current ones targeting the right players? Are they incentivizing the right behaviors? Are they targeting the right stage in the R&D process?

- Does access need to be considered only after a product is developed, or should it be a mandated component of R&D strategy?

- Who is setting the rules? Does the public sector need more power in PPPs and in multi-sectoral engagement?

- Should we demand a public return on public investment, and how should societies resolve any tensions between private and public interests?

Novartis

Rebecca Stevens, head of Access Partnerships and Public Affairs at Novartis Social Business, explained that Novartis has had several different models of engagement in the public health space since 2001 and that its goal has been to help enable access to medicine for populations around the world. The company’s first global health program focused on malaria. As part of that initiative, Novartis made a commitment to WHO to provide its malaria treatment at cost to malaria-endemic countries around the world. Novartis also worked with MMV on a pediatric version of the treatment.

Country governments also challenged Novartis to help address their high rates of NCDs, which included hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. In response to this challenge, the company launched an experimental model called Novartis Access in 2015. When it developed this initiative, Novartis compared its portfolio of drugs against WHO’s essential medicines list and decided to offer 15 medicines to address hypertension, diabetes, breast cancer, and asthma to governments at the price of $1 per month per patient. Novartis is still working to increase uptake of the program, which is lower than initially expected.

Stevens also described some of Novartis’s other global health programs. The leprosy donation program, for example, involves donation of leprosy medicines to patients around the world. The Healthy Families Program has both social and commercial arms in which health educators provide education about various diseases and available treatments in communities. The program also ensures that medical facilities and pharmacies in these communities have the medications they need to treat diseases—including Novartis’s medications and others.

Stevens noted that a challenge Novartis has faced in its effort to be a good corporate citizen is a lack of trust from some NGOs; they think the company seeks engagement only to push an agenda, and Stevens

suggested this is not the case. Novartis has faced another challenge in its efforts to fund country programs: identifying additional partners that are able to help make initiatives sustainable after initial Novartis investment. Novartis wants to ensure that a sustainability plan exists to allow the company to scale back its funding over time and to enable the government or another partner to take over.

Yet another challenge is related to the supply chain and to ensuring that Novartis’s drugs make their way to patients. As a result, Novartis has invested in health systems strengthening programs such as SMS for Life and activities such as monitoring stock at hospitals and health care facilities to ensure drugs are being distributed to patients. Because the supply chain continues to present challenges, involving more partners is important.

Stevens concluded by stating that she thinks PDPs have demonstrated progress in accepting the private sector as an integral partner. She noted that some of Novartis’s partnerships, such as those with MMV and DNDi, have allowed the company to show other organizations that it is concerned with similar public health goals. Novartis wants to be a partner in global health efforts because the company has a social responsibility to develop and globally distribute lifesaving medicines. Stevens sees true partnerships and collaboration as essential to achieving the company’s goals: better health and UHC for all patients globally.

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

Gavi is a PPP created in 2000 to improve childhood immunization coverage and accelerate access to new vaccines in developing countries. Gavi works toward its goal by leveraging the financial, technical, and business expertise of its partners, which include United Nations agencies, country governments, the pharmaceutical industry, the private sector, foundations, and civil society.

When opening her presentation, Natasha Bilimoria, director of U.S. Strategy at Gavi, explained that she would focus on Gavi’s advanced purchase commitment for the Ebola vaccine. Ebola was first identified in 1976, but the number of people who were infected in the early years was low—partially because people who were infected died quickly. Therefore, a vaccine was not very commercially viable. Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, in the United States, fear of Ebola becoming a bioweapon was widespread, and the United States and other countries started investing in an Ebola vaccine and treatment in case of attack. However, shortly after, investment declined until the West African Ebola outbreak in 2014, which was, by far, the largest outbreak to date; almost 30,000 cases and

nearly 12,000 deaths occurred in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone (CDC, 2019). At the time, attention to Ebola increased again, and Gavi leadership chose to prioritize Ebola’s remediation. Immunizations for other diseases had declined in the countries that experienced the Ebola outbreak, so the organization committed funding to strengthen health systems by providing grants for countries to start rebuilding their immunization system. Gavi also allocated funding to procure a licensed Ebola vaccine; however, no vaccine for Ebola existed. At that time, the organization developed the idea of an APC, which, Bilimoria described, was intended to be an incentive for companies to continue to develop a licensed Ebola vaccine.

According to Bilimoria, Gavi had three goals in mind. First, it wanted to ensure that an Ebola vaccine would be made available in the event that another outbreak occurred and that, if the vaccine were proven to be effective (even before licensure), it would be accessible to affected countries. Second, Gavi wanted to incentivize manufacturers to continue developing the vaccine. Third, once a licensed vaccine existed, Gavi wanted to create a stockpile so that the vaccine could be distributed quickly to affected countries when outbreaks occurred.

In order to achieve these goals, Gavi offered an APC to manufacturers who had an Ebola vaccine in clinical development. Gavi provided a pre-payment of $5 million and promised it would purchase at least $5 million in vaccines once they were licensed. In return, the companies had to ensure a sufficient supply of the vaccine would be available in case an outbreak occurred; apply for approval to use the vaccine in emergency settings; and continue to develop the vaccine and apply for vaccine licensure. Bilimoria noted these efforts were intended to signal to manufacturers that a market for a licensed Ebola vaccine existed. In 2015, Gavi approved an APC with Merck; it agreed to pay Merck $5 million as a credit for a licensed vaccine. In return, Merck was required to keep 300,000 doses of the vaccine available at all times and to fill and finish 100,000 products to act as a stockpile (Gavi, 2016). Merck was also required to apply to WHO for approval to use the vaccine in public health emergencies and to apply for licensure.

Bilimoria explained that Gavi created the initial APC, but other stakeholders were also involved. The U.S. government committed to providing at least $20 million in funding for an Ebola stockpile once the vaccine was licensed. UNICEF participated in creating the initial expression of interest and ensured that Gavi was able to converse with vaccine manufacturers about their plans and time lines. In addition, UNICEF agreed to work to procure the vaccine once it became licensed. Another important stakeholder group included the pharmaceutical companies that were manufacturing the vaccines. Gavi also worked with WHO, which was responsible

for reviewing manufacturer applications to allow the vaccine to be used in emergency settings and for making recommendations about vaccine use once it was licensed. Implementing partners on the ground worked to ensure that the vaccine could be used in emergency situations. Although they were not part of the APC, country governments provided leadership in coordinating and managing the response activities.

Bilimoria believed that the initiative’s greatest success was the creation of a vaccine that has been used to combat outbreaks. The outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in early 2018, for example, was contained largely because of the effective use of the Ebola vaccine (WHO, 2019). However, the country’s outbreak in late 2018 proved more difficult to contain because of security concerns (WHO, 2018b). Another success was the rapid detection of the outbreak and the communication efforts galvanized in response to it.

Bilimoria noted that developing a vaccine during an outbreak is challenging; an outbreak needs to occur in order for a vaccine to be tested, but expediting the clearances required to do the necessary testing can be difficult. Another challenge is balancing proactive versus reactive use of the vaccine; the type of use has implications for manufacturers in terms of the amount of vaccine they should produce. Yet another challenge is that the vaccine is only part of the overall outbreak response, and it is not a “silver bullet” because already-infected individuals cannot be vaccinated. Therefore, other measures also need to be taken to control outbreaks.

AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Kumar opened the discussion portion of the session by summarizing takeaways from the four speakers. The four models they presented illustrated that an initiative can be successfully moved from R&D and discovery to regulatory approval and launch with the right incentives, the right partnerships, and the right levels of trust. She noted the importance of company focus on health systems strengthening to ensure accountability in the market. Speakers also presented novel models for incentivizing private partners to participate in the global health arena. Kumar noted the presentations provided examples of a point related to SDG 17 that Singer outlined earlier in the workshop, SDG 17/Partnership + Impact = Trust, and the presentations also provided examples of multi-sectoral partnerships that created impact and built trust between sectors.

Kumar asked the presenters what their top challenges were and how they were able to solve them. Cohen responded first and acknowledged that a major initial challenge for DNDi was building its scientific legitimacy. There was skepticism that one of DNDi’s founding partners, MSF,

would be willing to engage with the private sector. Given that drug development and discovery historically have been performed almost exclusively in the private sector, DNDi had to attract people from the biotech and pharmaceutical industries and from academia in order to hire experts in those areas. Cohen explained that DNDi was, in some ways, an experiment in figuring out how to overcome tensions or competing interests between sectors in order to create positive outcomes for patients. However, while she agreed sectors share the goal of saving lives, she also believes they encounter many other competing interests along the way. She noted that acknowledging and being explicit about those competing interests is essential. Cohen stated that formal scientific partnership agreements about the overall vision of the initiative, as well as clarity about the “rules of the game” (e.g., intellectual property management, licensing conditions, and opportunities to cooperate and practice in a collaborative manner), allowed DNDi to overcome any initial distrust and to work constructively with multi-sectoral global partners.

Kaszubska responded to Kumar’s question about challenges by stating that MMV was largely a funding organization when it was founded 20 years ago, and it lacked much internal scientific expertise. Even though MMV built its scientific expertise over time and has been recognized for that expertise, MMV still needs to effectively influence pharmaceutical partners when it comes to drug development strategies.

Stevens suggested that trust continues to be a significant challenge. An additional challenge is the unrealistic expectation that another sector (e.g., NGOs for someone in the pharmaceutical industry and vice versa) will solve the whole problem. Stevens noted that many sectors (e.g., technology and logistics companies) can play roles in solving global health challenges, and it is important to broaden mindsets and to look to other sectors for help.

Bilimoria stated that working on R&D was a challenge for Gavi because it had not historically engaged in that activity. Typically, the organization provides funding to support vaccines that already exist—not to create new ones.

A participant asked the presenters for their thoughts on how to sustain the energy and innovation demonstrated through the four presentations. The participant considered these traits necessary to address terrible and relatively rare health threats to poor people around the globe. Kumar noted that scalability and sustainability are two salient challenges. Cohen responded that a clearer dichotomy between health needs in LMICs versus those in higher-income countries existed about 20 years ago; for example, a line was drawn between communicable diseases and NCDs. Higher-income countries donated to organizations such as Gavi, the Global Fund,

and, to a lesser degree, Unitaid to address health challenges in LMICs. However, “the golden era of global health is over” because the ongoing subsidization of global health initiatives by higher-income countries has declined as nationalism has risen. Cohen suggested that “global solidarity and multilateralism is in serious peril,” and there is an important need to change this. She said older models that previously reigned in global health create a recipient/donor relationship that is probably unhealthy and needs to evolve; however, the move away from such models puts middle-income countries in a particularly challenging situation. Middle-income countries should be especially supported in their efforts to make use of existing leadership, skills, and expertise in regions that have both innovation capacity and extreme health needs.

Stevens responded that energy and momentum could best be sustained through impact measurement, particularly when an evaluation shows that an initiative impacts society positively, saves lives, and allows people in low-income countries to lead productive lives. She pointed out that the “feel-good effect” of receiving this form of positive feedback sustains energy and that “success begets success”—referencing the enthusiasm she witnessed among her R&D colleagues as they worked to develop pediatric versions of existing drugs in order to forge solutions to the burdens of disease. Kumar then agreed with the notions that success begets success and that multi-sectoral global health initiatives are significant drivers of employee engagement within the private sector.

Bilimoria agreed with Cohen’s point about countries acting as leaders and noted that most work to sustain their own immunization programs. Gavi requires co-financing by all countries involved, and Gavi has seen countries begin to assume the financial sustainability of their immunization programs. Bilimoria noted that increasing attention to country leadership and ownership and providing technical assistance are two important strategies to increase funding and to sustain work.

Gaudenz Silberschmidt, director for Partnerships and Non-State Actors at WHO, commented that hearing about the complexity of the situations was helpful and that all stakeholders do not always agree on everything. Silberschmidt then followed up on Cohen’s point about the role of middle-income countries; he asked for her perspective on what steps are needed to engage middle-income countries, which contain about three-quarters of the world’s population, in PPPs. Cohen responded by providing an example of DNDi’s work to develop pediatric formulations of antiretrovirals and affordable, direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C. These diseases have full research pipelines that have delivered “paradigm-shifting technologies,” but they are unaffordable for most people. Cohen explained that DNDi has been working with the Malaysian Minis-

try of Health, a founding partner of DNDi, and an Egyptian pharmaceutical company to develop an NS5A inhibitor that will be combined with sofosbuvir, the backbone of current hepatitis C treatment. Development had not proceeded on this product previously, in part, because the hepatitis C market had been dominated by Gilead and AbbVie. The Malaysian Ministry of Health is a key partner and is helping finance the clinical trials in partnership with DNDi and the pharmaceutical company. As a result, there has been success in overcoming intellectual property barriers, and discussions are taking place about using the resulting product in Malaysia’s national hepatitis C program. Such use would lead to scaled-up access to direct-acting antivirals using a public health approach and progress toward eliminating hepatitis C in Malaysia. Cohen concluded that the public leadership from the Malaysian Ministry of Health helped to transform and contributed to conducting clinical trials in a way that will ensure access.

Next, Sir George Alleyne commented on the importance of framing issues in the right way to elevate their importance within the public domain. He asked panelists how the championing efforts of political entrepreneurs have been useful in framing these issues for the public and whether their efforts have elevated the level of success of certain initiatives.

Alleyne further clarified that his question referred to political champions, such as heads of state, and shared his belief that presidential influence had been important to spur the U.S. government to provide funding to address vector disease. Stevens noted that PEPFAR was also championed by a former president. Bilimoria agreed about the importance of political support and noted the “golden era” of public health support had been beneficial because full-fledged global health programs with billions of dollars in funding exist as a result. However, there is still a need to fight for funding for these programs every year, and funds are declining in many places where budgets are tight. She believes highlighting the impacts of global health program funds for people on the ground is important and noted how such impacts can benefit a country government and allow it to promote its own foreign policy assistance.

Cohen responded that, although the support of political leaders has been very important, this type of support for neglected tropical diseases such as Human African Trypanosomiasis (African Sleeping Sickness) has never occurred. She noted the “political entrepreneurs” in this case were often unknown doctors and nurses, including individuals like Dr. Victor Kande from the Democratic Republic of the Congo Ministry of Health.

Ilze Melngailis with the United Nations Foundation next asked how organizations such as the United Nations and other entities that work

with, through, and for the United Nations can help to accelerate global uptake of the cutting-edge best practices described by the presenters. She elaborated further by asking what role the United Nations could play in financing development progress, accessing ministers of finance, and increasing the adoption of cutting-edge partnerships. Bilimoria responded that she considers working with ministers of finance to be an essential element, and Gavi does this; it manages the funding. Cohen added that she considers SDGs and WHO’s targets to be useful frameworks for describing the overarching goals that partnerships work toward. She added that a PPP cannot itself be a goal, and maintaining clarity of purpose is important. She also noted that PPPs cannot be developed for ideological reasons and could be developed, instead, because they are the most effective way to deliver services to target populations.

In closing the session, Kumar noted themes of impact and urgency in each model presented and illuminated that each example illustrated either a market failure or another pressing issue (e.g., an Ebola outbreak) that brought together people who may distrust each other. She stated the importance of creating a similar type of platform to address other pressing global health issues across the world. Kumar mentioned that the next day’s sessions would focus on convincing people who are not already engaged in PPPs of the importance of this type of work. In closing, Stevens added that, in order to be most effective, partnerships with the private sector need to be authentic and genuine and give each partner a seat at the table.

This page intentionally left blank.