The workshop’s third session considered the issues of access and equity in the context of clinical trials and how a virtual model could alleviate or exacerbate current inequities. The discussions focused on the importance of creating partnerships with participants and underrepresented communities, as well as the potential benefits and risks of using digital health technologies to support clinical trials for populations that are traditionally underrepresented in research and whether this type of trial design could potentially exacerbate current inequities or create barriers to access for other communities. Will McIntyre, a patient advocate for The Michael J. Fox Foundation, provided a patient’s perspective on access and equity. Sally Okun, vice president of policy and ethics at PatientsLikeMe, described innovative opportunities to increase participant engagement for people living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Silas Buchanan, chief executive officer (CEO) of the Institute for eHealth Equity, described an approach to conducting meaningful outreach and engagement for underserved communities, and Sherine El-Toukhy, the Earl Stadtman Investigator at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, offered lessons learned from behavioral interventions on equitable participation of minorities in research. An open discussion, moderated by Kathy Hudson, executive director of the People-Centered Research Foundation, and Rebecca Pentz, professor of hematology and medical oncology in research ethics at the Emory University School of Medicine, followed the four presentations.

Hudson noted that despite the 1993 National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act requiring National Institutes of Health (NIH) investigators to include women and ethnic minorities in clinical research (IOM, 1994), this goal has not been achieved. In 2004, 67 percent of papers presenting results from clinical trials did not include sex in the analysis, whereas in 2015, 72 percent of NIH-funded clinical trials did not include sex in the analysis (Geller et al., 2018). Similarly, in 2004, 83 percent of NIH-funded studies did not include race or ethnicity in the analysis while in 2015, 85 percent of papers did not include race and ethnicity in the statistical analysis (Fornai et al., 2008). Keeping this lack of progress in mind will be important, Hudson emphasized, as new approaches, opportunities, and methods are considered.

A PATIENT PERSPECTIVE

Will McIntyre, Patient Advocate, The Michael J. Fox Foundation

Will McIntyre, a Parkinson’s disease patient, advocate, and volunteer with The Michael J. Fox Foundation, emphasized the need to engage with patients in the design of trials. Making it easy for patients to contribute their feedback on the trial participation experience can result in a plethora of information that researchers can use to improve clinical trials and trial outcomes. High-speed cellular networks should be leveraged to make the clinical trial experience as easy as possible for participants, said McIntyre. Not only could they enable patients to participate remotely, they could also address geographic inequities that result from participants living away from trial sites. As an example, McIntyre described an initiative at Fox Insight,1 in which a team is initiating dialogue with patients enrolled in Fox Insight studies to collect and aggregate information on the daily lived experience of people with Parkinson’s disease. This information is collected remotely, but as McIntyre noted, representation reflects the rural–urban divide in Internet connectivity, highlighting the concentration of participation across coastal urban centers with little geographic representation in the Midwest. To address this unmet need, the research and technology sectors could work together to equip participants with technologies that will better enable them to connect with research studies.

RECRUITMENT FOR CLINICAL TRIALS

Sally Okun, Vice President of Policy and Ethics, PatientsLikeMe

Sally Okun, using ALS as a use-case, focused her presentation on how unique trial designs, such as virtual trials and patient-initiated trials, can not only create new insights, but also increase participation rates of those who are typically excluded from clinical trials. Though PatientsLikeMe now focuses on a variety of disease areas, its story began with the desire to increase access to real-world data for people living with ALS.

One of the first studies conducted by PatientsLikeMe was in response to a request from ALS patients to investigate the efficacy of lithium-carbonate—

___________________

1 Fox Insight is an online study that seeks to build a large, diverse cohort of participants that is representative of Parkinson’s patients. Once enrolled and every 90 days thereafter, participants are asked to enter health and disease information. Fox Insight is meant to complement in-person research, and curated data are made available to researchers worldwide in real time. Launched as a beta study in March 2015, more than 5,000 participants (80 percent with a Parkinson’s disease diagnosis) contributed data before the study’s formal launch in April 2017 (The Michael J. Fox Foundation, 2019b).

a compound found to be effective in slowing ALS progression in a prior study (Fornai et al., 2008). Given ALS’s fatality, it was understandable that patients were both seeking to get access to lithium-carbonate and validate its efficacy, said Okun.

PatientsLikeMe recruited 160 patients to participate in the study and used a similar method of self-monitoring used in Fornai and colleagues’ (2008) study. While PatientsLikeMe and subsequent NIH studies (Wicks et al., 2011) refuted the results found in Fornai et al. (2008), a recent meta-analysis of all ALS studies using genomic data identified that those with the Unc-13 Homolog A (UNC13A) genetic variant2 may have a response to lithium-carbonate (van Eijk et al., 2017). This finding in a subgroup of patients with ALS is being explored further by researchers in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, noted Okun.

Identifying Off-Label Treatments for Possible Clinical Trials

PatientsLikeMe is also a member of ALSUntangled, a consortium of patients, clinicians, and researchers that seeks to understand the efficacy of alternative and off-label treatments to which people living with ALS turn. ALSUntangled engages in patient-driven inquiry by basing research initiation decisions on patient input regarding which alternative treatments to test further. As of 2015, ALSUntangled has reviewed more than 40 therapies and graded them based on validity and potential benefit, using the following metrics: mechanistic plausibility, strength of relevant pre-clinical data, case reports, existence of trials, and identified risks (ALSUntangled Group, 2015). One such product is Lunasin, a soy peptide for which there is some theoretical basis to believe it could be relevant for ALS, some potentially supporting case study data, and a peer-reviewed trial. As a result, PatientsLikeMe and the Duke ALS Clinic decided to explore this product more.

The resulting study, ALSUntangled No. 26: Lunasin study (ALSUntangled Group, 2014),3 a hybrid virtual trial, required the 50 participants who enrolled to have a clinic visit on day 1, day 30, and day 365. At all other times, participants entered information into their PatientsLikeMe online profile, and they were also contacted by the clinic nurse and community moderator. Lunasin therapy did not produce improvements in progression scores, but the study did show that participants liked engaging in research that did not require frequent trips to the clinic (Bedlack et al., 2019). Furthermore, by

___________________

2 UNC13A is a gene that encodes the Unc-13 homolog A protein, which is involved in neurotransmitter release (Bohme et al., 2016).

3 Available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02709330 (accessed April 22, 2019). Additional information can be found in Appendix D.

eliminating the typical requirements4 for inclusion, the study was able to get a more representative subset of ALS patients (ALSUntangled Group, 2014). Retention in the study was nearly 89 percent, indicating that participants were satisfied with the trial design and were committed to participating in the trial. Regarding access, inclusion, and engagement, Okun and her colleagues concluded that this approach could serve as a model for other diseases in which PatientsLikeMe could become involved.

Based on their experience with the Lunasin trial, PatientsLikeMe and the Duke ALS Clinic are designing two virtual trials: ALS Reversals (Harrison et al., 2018) and ALSUntangled No. 44: Curcumin (Bedlack, 2018). The studies will investigate “differences in demographics, disease characteristics, treatments, and co-morbidities” between patients who have experienced ALS reversals and those who have not, in addition to the efficacy of curcumin in treating ALS, respectively (Okun, 2018). Both studies will include a range of phenotypic data entered online by patients as well as multi-omics data from in-home biospecimen collection.

UNDERSERVED COMMUNITY OUTREACH AND ENGAGEMENT

Silas Buchanan, CEO, Institute for eHealth Equity

Silas Buchanan emphasized the importance of engaging directly with community members when deploying digital interventions. Building a network of partnerships and leveraging trust brokers within the community can be instrumental in the success of public health campaigns. Using his social impact firm, Institute for eHealth Equity, as an example, Buchanan provided key lessons learned for how virtual trials can be designed and positioned to increase inclusion of underrepresented populations, and if there are specific trial design considerations needed to address the unique socioeconomic factors those populations face.

Will Technology Improve or Exacerbate Problems with Access and Equity?

The Institute for eHealth Equity was formed to address the concern that the adoption of technology in health care might exacerbate health disparities given that developers rarely seek input from underserved populations. For example, Buchanan remarked how academic medical centers in the Cleveland area often receive grants from developers to study African American infant mortality rates, but none have invited community organizations or members to offer input when grants are being written. To address this problem, the

___________________

4 Inclusion requirements for ALS clinical studies include high scores for respiratory and swallowing functions and having ALS for less than 36 months.

Institute for eHealth Equity has built social networks, systems, and platforms for faith- and community-based organizations that have relationships with the individuals in their communities. The Institute for eHealth Equity’s approach to community health is based on Buchanan’s prior experience with a project called Text for Wellness5 in which he and his colleagues asked pastors in five faith-based organizations—in Atlanta, Georgia; Columbus, Ohio; and Dallas, Texas—to talk about health from the pulpit. Churchgoers were also asked to interact with a mobile health service, in which they received evidence-based healthy eating and activity text messages and queries. The five churches generated 2,500 participants, 43 percent of whom responded to the questions. According to Buchanan, the program had a 100 percent retention rate, indicating the success of a public health campaign that leverages faith- and community-based organizations as an entry point.

An Online Portal for Community Engagement and Collaboration in Clinical Trials

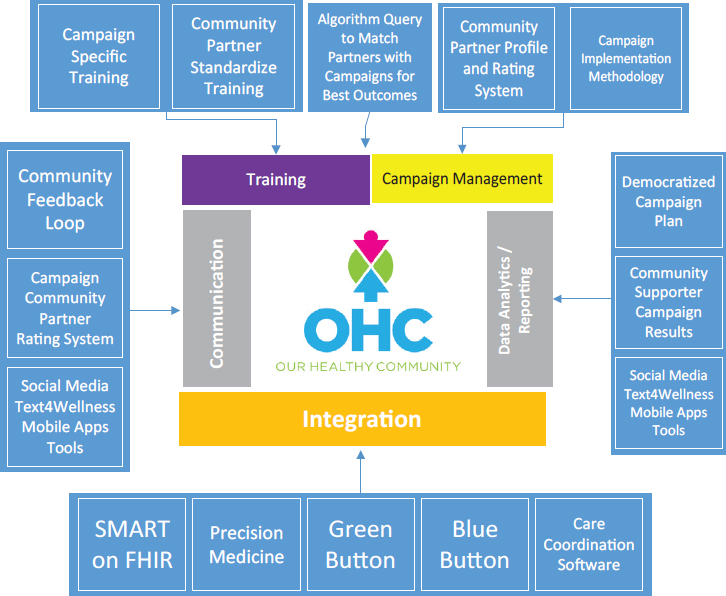

The Institute for eHealth Equity has recently developed a platform called Our Healthy Community6 in collaboration with faith- and community-based organizations, including the African Methodist Episcopal Church.7 Our Healthy Community enables underserved faith- and community-based organizations to coordinate community health improvement campaigns sponsored by health care payers, providers, and government and academic stakeholders. Recently, Our Healthy Community signed a memorandum of understanding with the City of Cleveland Office of Minority Health to provide 30 community-facing organizations with access to this platform in order to cover approximately 30,000 community members in targeted public health campaigns. Our Healthy Community is designed with six broad features to achieve desired, trackable outcomes around sponsored public health campaigns (see Figure 4-1):

- Standardized and public health campaign–specific training for faith- and community-based organizations.

- Coordination of partners to shape campaign scope and strategy (see Box 4-1 for an example of early communication to develop tools for infant mortality).

___________________

5 Available at http://text4wellness.com (accessed April 22, 2019).

6 Available at http://www.ourhealthycommunity.com/Public/About-OurHealthyCommunity (accessed April 22, 2019).

7 The African Methodist Episcopal Church is the largest historically black denomination worldwide, with more than 2,000 congregations and more than 2 million members. Approximately 30 percent of these congregations have a dedicated health minister embedded in the church to foster relationships with health care systems in their communities.

NOTE: FHIR = Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources; SMART = Substitutable Medical Applications, Reusable Technologies.

SOURCE: As presented by Silas Buchanan, November 29, 2018.

- A queriable database to match community partners with the right public health campaign.

- Consistent communication with community members to push the message of the public health campaign.

- Integration with an open-source system, such as SMART on FHIR8 and Blue Button,9 and other care coordination systems to allow community members to own and control health data.

___________________

8 SMART on FHIR “is a set of open specifications to integrate apps with electronic health records, portals, health information exchanges, and other health information technology systems” (SMART, 2017).

9 Blue Button is a system for patients to view their personal health records online and download them into a text file or a PDF (VA, 2018).

- Sharing of data along the value chain, including community members, community organizations, and public health campaign funders, to issue campaign updates and create a feedback loop between community members and funders.

A key to the successful introduction of digital tools in health care is to have a mechanism to hear what the community wants rather than designing them in a vacuum, said Buchanan. This will require a strong ethos for community engagement, including the acknowledgment of histories of discrimination, transparent discussions about power and responsibilities, documentation of community strengths, collection of local knowledge to understand a community’s culture intimately, and building capacity within the community to identify opportunities for co-learning and sustainable, equitable partnerships. Primary outcomes of successfully launching a digital tool ultimately will be the establishment of democratized feedback loops with community members. By being part of Our Healthy Community,

community partners will gain access to tools that will enhance their ability to reach community members. They will also receive accurate and timely feedback reports using community member input that will contribute to a public health campaign’s success.

According to Buchanan, virtual or direct-to-participant (D2P) trials can be positioned and designed to increase inclusion of underrepresented populations, though they will need to address unique considerations to sustainably build relationships with the community. He also believes that data-driven insights and emerging tools can be leveraged to both generate data on access and equity, in addition to improving inclusion of underrepresented populations. Furthermore, Buchanan noted that there are specific disease areas, such as sickle cell anemia, in which access and equity can be improved immediately.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS

Sherine El-Toukhy, Earl Stadtman Investigator, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

Sherine El-Toukhy highlighted lessons she has learned from research on the participation of underserved populations in digital behavioral interventions. She suggested that while health information technology may reduce health inequities, it can unintentionally exacerbate existing disparities or create new ones.

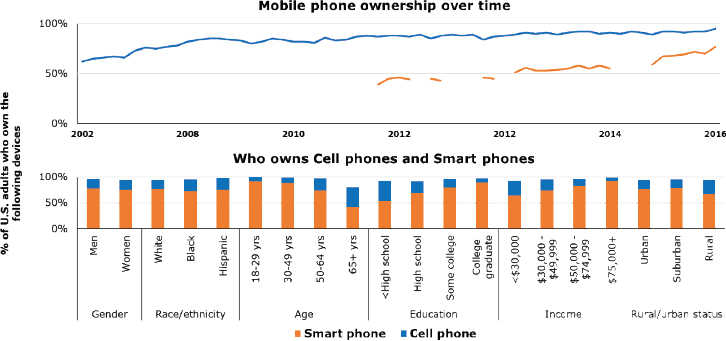

Data show that the digital divide is shrinking in the United States. Cell phone ownership10 of any kind in the United States is now at nearly 95 percent, with smartphone ownership reaching 77 percent (Pew Research Center, 2017). Mobile phone ownership is seen across nearly all socioeconomic groups, though disparities still exist based on age, education, and income level (see Figure 4-2).

Data from the Health Information National Trends Survey, sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, also show that 80 percent of Americans report having Internet access, either through a broadband connection, cellular plan, or Wi-Fi (El-Toukhy et al., In Review). However, older individuals, those of low socioeconomic status, people who are separated or widowed, and those with limited English proficiency are less likely to report using the Internet, noted El-Toukhy. El-Toukhy identified similar trends with respect to patient portal access. Lower educational attainment, she noted, was a main characteristic associated with less access to and use of electronic health records (EHRs) (El-Toukhy et al., In Review).

___________________

10 Cell phone ownership indicates the percentage of U.S. adults, age 18 and above, who own a cell phone (Pew Research Center, 2017).

NOTE: Breaks in the line graph for smartphone ownership indicate where there is a gap in data.

SOURCES: As presented by Sherine El-Toukhy, November 29, 2018; data from Pew Research Center, 2017.

Community Member Engagement

El-Toukhy noted that evidence-based behavioral interventions have shown promise for addressing social and behavioral factors that underlie morbidity and mortality. For example, a National Cancer Institute text messaging program, SmokeFreeMOM, can increase smoking cessation rates among pregnant women who want to quit smoking (Kamke et al., In Review). Cessation rates were found to be comparable among Hispanics, African Americans, and whites at interventional milestones (e.g., quit day, intervention end, and 1-month follow-up). However, only 9 percent of study participants were Latina and 16 percent were African American, which is well below the national representation for these groups.

Understanding the target population’s needs, values, and preferences, as well as their barriers to participation, is key to designing culturally and linguistically appropriate clinical trial recruitment material, said El-Toukhy. She noted there are websites11 that can create customized recruitment materials to meet the needs of target populations based on age, race, ethnicity, and other factors. Furthermore, investigators should consider modes and outlets of recruitment to ensure efforts are targeting desired populations.

___________________

11 See Make It Your Own for an example of a platform to facilitate creation of customized health information for targeted populations (MIYO, n.d.).

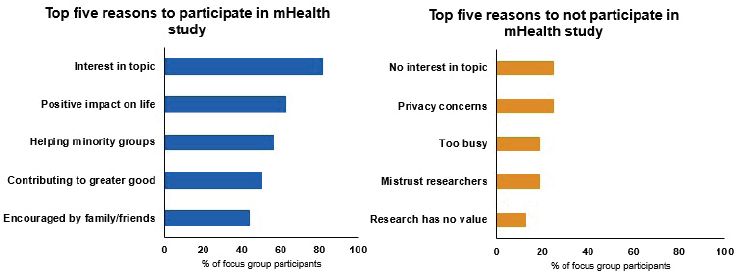

NOTE: mHealth = mobile Health

SOURCE: As presented by Sherine El-Toukhy, November 29, 2018.

Sustained engagement of research participants is important in the context of digital interventions. Unfortunately, high dropout rates can be common. For example, in the text messaging-based smoking cessation intervention mentioned earlier, dropout rates were highest during the first week of the intervention, with continued dropouts over time. To improve engagement, it is important to involve the end users in the creation and design process and to prioritize the needs and wants of marginalized populations, said El-Toukhy. Furthermore, the use of passive or automated data collection or simplified assessment instruments12 can reduce the time and resource intensiveness of assessment. Providing an example of an algorithm used to improve outcomes in Drug Court (Marlowe et al., 2012), El-Toukhy emphasized the potential of adaptive designs to monitor and adapt a trial in case of missing responses based on predetermined rules. In the context of a virtual clinical trial, for example, a reminder schedule can be designed to prompt the participant to enter the missing data only if someone fails to log a piece of information.

While there is a myth that minorities and underserved populations do not want to participate in studies, El-Toukhy presented unpublished data from two focus groups with 16 African American women that found the opposite. In fact, these women are willing to participate in research to generate knowledge that will help their communities and contribute to the greater good (see Figure 4-3). Barriers to participation, El-Toukhy noted, are not as prominent as expected, with the main barriers being lack of interest and skepticism about the researchers or value of a study.

___________________

12 El-Toukhy provided examples of instruments, including PROMIS, Neuro-QoL, ASCQ-Me, and NIH Toolbox (Health Measures, 2019).

El-Toukhy emphasized the need to leverage the willingness of minorities and underserved populations to participate in clinical trials. By increasing engagement with minority communities, from outreach and consultation to collaboration and shared leadership (NIH, 2011), trust will be fostered and barriers to participation can be alleviated.

DISCUSSION

Hudson noted that a common theme raised by panelists was the importance of inviting patients to inform study design early in the process, and asked the panelists to provide examples of how to do this effectively. A specific approach on how to do this was proposed by McIntyre, who reflected on a practice at The Michael J. Fox Foundation that involved adjusting language in the recruitment and engagement processes to make participants feel like contribution was more meaningful than just inputting data into their phones or computers. Similarly, Okun shared that PatientsLikeMe has been developing two tools:

- Patient Trial Experience Survey: Queries those who join PatientsLikeMe about their prior participation in a clinical trial and their experiences with previous clinical trials.

- Trial Mark: Targets those who run clinical trials to gauge what they perceive the participant experience to be. Trial Mark will be released in 2019 and will benchmark trials against others in terms of participant centeredness and give participants a voice in being able to measure what is important.

El-Toukhy echoed these comments, indicating that an iterative approach that includes usability testing and focus groups to perfect the design of an application or an intervention would be useful. Another approach could involve crowdsourcing, but would likely prove more useful for diseases that affect large numbers of people.

In addition to involving patients early in the study design phase, patient engagement can be strengthened by returning data. Cynthia Geoghegan from the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI) noted that a survey CTTI conducted on 400 potential research participants revealed that 98 percent of respondents wanted their data retuned in real time. In fact, the National Academies report Returning Individual Research Results to Participants: Guidance for a New Research Paradigm (NASEM, 2018b) called for a return of individual results to participants. According to Hudson, this is a reflection of a broader cultural shift from paternalism to partnership in medicine and research. However, strengthening participant engagement through return of data, according to Geoghegan, may need to

be balanced with impacts on randomization. Both Okun and El-Toukhy acknowledged this risk, emphasizing that participants should be educated about randomization upon recruitment and that data returned should not expose inappropriate information that can damage the integrity of the trial. Creating a mechanism for return of data that people trust will be important, noted Buchanan. Furthermore, establishing a plan on returning data in the research design itself will make it more likely that it occurs, noted Okun, in reference to a data giveback plan that PatientsLikeMe uses.

Valerie Barton from FasterCures asked Buchanan how Our Healthy Community notifies community members once a public health campaign has been completed. She also asked about how data collected by Our Healthy Community are used, aggregated, and analyzed and whether that plays into outreach efforts. According to Buchanan, Our Healthy Community is able to share aggregated data from its campaigns with community organizations for their own uses. Buchanan noted that a long-term goal of Our Healthy Community includes analyzing trends and capturing data on social determinants of health and integrating this information with EHRs.

Cummings commented on the unique needs of patient and community engagement to ensure that clinical trial research can account for differences in outcomes that may be attributable to demographic and/or disease severity differences. NIH requirements to recruit a population that represents the underlying U.S. demographics may not be sufficient to account for the power needs to investigate if, for example, there is a biological reason for why Hispanics and whites respond to an intervention differently, said Cummings. He then remarked that for some studies, such as one he is doing on Parkinson’s disease and aging, people with more severe forms of the disease need to be better represented, which is hard to achieve. More unique and creative forms of engagement would be required to include underrepresented populations for these purposes, Buchanan suggested.

Emily Butler from GlaxoSmithKline asked the panelists if they had ideas on how to incentivize industry sponsors to more actively involve patients in trial planning and design. Hudson replied that her organization, the People-Centered Research Foundation, involves patients as partners from the start of a project and compensates them for their efforts. Then, when the foundation starts working with prospective sponsors of a study, it clearly states that it has requirements for meaningful participation, something that potential sponsors have embraced uniformly. However, for the widespread culture of the pharmaceutical industry to change, said Hudson, there needs to be evidence showing that involving patients to this extent improves outcomes and a continued expectation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that clinical trials focus on patient partnership.

This page intentionally left blank.