In the workshop’s fourth session, the panelists discussed current and future policies that govern clinical trials and their relevance to virtual trials. They examined the challenges and potential solutions to issues involving the collection of remote data from participants (e.g., how to ensure collected data comes from the actual participant and if participants are using a digital health technology properly) as well as privacy considerations. Leonard Sacks, associate director for clinical methodology in the Office of Medical Policy at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, discussed his views on policy considerations for decentralized trials. Leanne Madre, director of strategy at the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI), discussed her organization’s decentralized clinical trials project. Deven McGraw, general counsel and chief regulatory officer at Ciitizen Corporation, spoke about privacy protections for virtual trials, and Matthew McIntyre, senior scientist for data collection at 23andMe, discussed considerations for informed consent in relation to passive data collection and its associated paradata. An open discussion moderated by John Wilbanks, chief commons officer at Sage Bionetworks, and David McCallie, senior vice president for medical informatics at Cerner, followed the four presentations.

A REGULATORY PERSPECTIVE

Leonard Sacks, Associate Director for Clinical Methodology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Sacks highlighted the opportunities to use mobile technologies and engage local providers to promote inclusivity and convenience for trial participants, and for gathering information on real-world patient experience. These opportunities will require policies and regulations to address patient safety, privacy, the integrity of the data that remote technologies produce, and the responsibilities of the investigators involved in technology-enabled decentralized trials.

Decentralized clinical trials are not new, said Sacks, but recent advances in communication, data capture, and transmission technologies have created opportunities to conduct decentralized trials better—as has the recognition of local health care providers’ value in performing trial-related functions. While the considerations for using new technologies in decentralized trials are not unique, there is the need to apply existing regulations to a new environment. Those regulatory considerations may vary, he added, depending on the disease area, the type of investigational drug, and the types of trial activities that are decentralized.

According to Sacks, there are four areas of interest for regulators when thinking about policy considerations for technology-enabled decentralized clinical trials: (1) the personnel involved in the trial, (2) the trial site, (3) the tools being used, (4) and participant safety.

Clinical Trial Personnel

Current FDA regulations say little about encounters with study participants, said Sacks, but they do address personnel oversight responsibilities. The Code of Federal Regulations defines an investigator as an individual who actually conducts a clinical investigation, that is, the person under whose immediate direction the drug is administered or dispensed to a subject.1 He pointed out that this definition does not require a face-to-face encounter. In the event that a team is conducting the study, the investigator is the responsible leader of the team. A sub-investigator includes any other individual member of that team. The investigator and any sub-investigators need to have a good understanding of the protocol and investigational product and they need to have direct and substantial involvement in the trial, regardless of whether it is a site-based or decentralized trial. The

___________________

1 21 CFR § 312.3.

investigator and sub-investigator are listed on the Form FDA 1572, a legal agreement signed by the investigator that he or she will comply with FDA regulations2 related to the conduct of a clinical trial. Local providers, such as phlebotomists or those who prepare pathology reports, do not have to meet those criteria.

Clinical Trial Site

A clinical trial site traditionally has been a physical location. However, FDA regulations do not have a clear definition for this term. Typically, a site is where the intervention is provided and where assessments for the trial are conducted. Given this lack of clarity, a key issue to consider is whether there are practical limits to the decentralization of trial activities under a single investigator’s supervision. Another issue regulators may need to address is how supervision, monitoring, and inspection will be conducted at decentralized sites, said Sacks. For some trials, investigator supervision of participants may not be much of a concern, but for others, such as a trial for a new antidepressant during which participants’ behaviors may not be predictable, closer supervision might be necessary.

Clinical Trial Tools

Regardless of the type of communication tool used in a clinical trial, an important consideration will be to ensure the integrity and security of electronic records, said Sacks. Additional concerns include the attribution of data and appropriate use of audit trails to reconstruct how data are generated. Lastly, Sacks emphasized that the accuracy and precision of remote biosensors are critical to prevent false-positive readings.

Participant Safety

Ensuring participant safety in a decentralized trial is no different than in a traditional clinical trial, said Sacks. Participants would require access to qualified professionals to address adverse events, for example, and investigators would need to make provisions for prompt capture of safety data from participants and their providers during the course of a trial. However, Sacks noted that remote sensing technologies are creating opportunities

___________________

2 Responsibilities include follow the protocol, personally conduct or supervise the study (delegation is permitted), receive informed consent covered by an Institutional Review Board (IRB), report adverse events, understand potential risks and side effects, ensure that all associates assisting in the conduct of the study are informed about their obligations, adequate and accurate recordkeeping and retention, and reports to the IRB.

for greater oversight of safety by replacing episodic monitoring with continuous monitoring of variables such as blood glucose levels or heart rate and rhythm. At the same time, he cautioned, it is important to ensure that technology failure does not jeopardize participant safety or the integrity of the data and that technical support is available for when a digital health technology malfunctions.

Sacks envisions decentralized trials to operate like a hub-and-spoke model, with the investigator and sub-investigator at the center and participants at the periphery, and connected by local providers and mobile technologies. If the technologies used in decentralized trials can collect robust data with high signal-to-noise ratios,3 it may be possible to shorten trials and possibly increase participant retention. Remote tools may also reduce the number of participants required to power a study if the signal-to-noise ratio is high enough. However, for mobile technologies to reach their potential of bringing a clinical trial to the participant, policies and regulations to address participant safety, privacy, data integrity, and the responsibilities of investigators in a decentralized trial environment need to be in place.

CLINICAL TRIALS TRANSFORMATION INITIATIVE: DECENTRALIZED CLINICAL TRIALS PROJECT

Leanne Madre, Director of Strategy, Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative

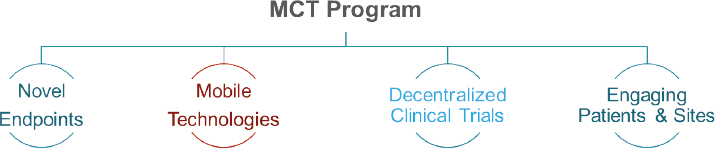

CTTI, explained Leanne Madre, is a public–private partnership co-founded by Duke University and FDA. Currently, more than 80 members, representing stakeholders from academia, biotech companies, pharmaceutical companies, patient groups, regulators, and others, are working to “develop and drive adoption of practices that will increase the quality and efficiency of clinical trials” (Madre, 2018). CTTI started its Mobile Clinical Trials (MCT) program4 (see Figure 5-1) at FDA’s suggestion, with the purpose of influencing the widespread adoption and use of mobile technology in clinical trials.

The MCT program consists of four projects: novel endpoints, mobile technologies, decentralized clinical trials, and engaging patients and sites. The first project focused on how to collect existing endpoints differently using technology and how to validate endpoints that are now available due to emerging technologies (CTTI, 2019d). The second project focused on

___________________

3 Signal-to-noise ratio compares the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise. It is a measure of how much useful information a technology can produce.

4 Available at https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/programs/mobile-clinical-trials (accessed April 20, 2019).

SOURCE: As presented by Leanne Madre, November 29, 2018.

the mobile technologies themselves: how to select one while keeping data quality and implications for regulatory submission in mind (CTTI, 2019c). The third project investigated the benefits of conducting clinical trials outside of traditional brick-and-mortar sites (CTTI, 2019a). The fourth project focused on understanding how patients and investigators viewed the opportunities and challenges of applying digital technology in clinical trials (CTTI, 2019b).

Decentralized Clinical Trials Project

Madre focused her discussion on the third project under CTTI’s MCT program. Key benefits of a decentralized clinical trial that CTTI was able to identify included those that previous speakers discussed: faster trial participant recruitment; improved retention; greater control, convenience, and comfort for participants; and increased participant diversity. To achieve these benefits, CTTI issued recommendations that fell into six categories: protocol design, telemedicine state licensing laws, mobile health care providers, drug supply chain, investigator delegation and oversight, and safety monitoring.

Protocol Design

Protocol design for a decentralized trial, said Madre, does not require an all-or-nothing approach. In fact, elements of decentralization, such as telephone or video conferencing, can be incorporated in a protocol that uses a traditional site. However, engaging with FDA early in the design process and highlighting the unique attributes of a decentralized trial when developing the trial protocol and standard operating procedures will be important for trial success. FDA has a number of established pathways through which investigators can meet with regulators early in the process of designing a study, said Madre. CTTI also encourages investigators to talk to those who have already conducted a decentralized trial, including other sponsors and even technology vendors, to avoid having to relearn lessons and instead build on what others have already accomplished.

Telemedicine State Licensing Laws

When the project started, there was a perception that there were notable legal barriers to conducting decentralized trials, noted Madre. However, there were only a few legal issues to deal with—particularly state licensing. Physicians or health care providers require a professional license from the state in which they practice as well as the state where they see patients. Given that laws can vary by state, conducting a decentralized trial can require different strategies to meet licensure requirements (i.e., maintaining licensed investigators in each active trial state, using investigators licensed in multiple states, or contracting with vendors that have a network of licensed investigators in place). Madre noted that the Center for Connected Health Policy maintains a website5 that compiles information on telemedicine laws across the United States.

Mobile Health Care Providers

As a decentralized clinical trial can cover a wide geographic area, it might be necessary to use mobile health care providers—or health care providers who can travel to participants for protocol contributions. Activities can include blood draws, administration of the investigational products, clinical assessments, and in-home compliance checks. Thus, it will be important for such providers to be properly credentialed and trained.

Drug Supply Chain

Similar to licensure, direct-to-participant shipment of drugs can also vary by state. State laws governing shipment of the investigational product should be reviewed, noted Madre, prior to conducting a decentralized clinical trial. Furthermore, it is also important that the supply chain is well documented so that everyone involved in a study understands their role in the supply chain. Engaging with vendors who have prior experience shipping investigation medical products to participants would be useful to sponsors, noted Madre.

Investigator Delegation and Oversight

Developing procedures for investigator delegation and oversight is highly protocol specific, said Madre. The standards employed in a decentralized trial do not need to be higher than for a standard trial, but the differences between

___________________

5 Available at https://www.cchpca.org/telehealth-policy/legislation-and-regulation-tracking (accessed January 30, 2019).

a standard and a decentralized trial must be accounted for when thinking about delegating responsibilities to investigators, sub-investigators, and local providers. This is another area, she added, where talking to regulators early can pay dividends.

Safety Monitoring

Given the different array of providers involved in a decentralized clinical trial, it will be important for investigators to ensure that trial participants and trial staff are aware of procedures related to adverse events and that the response plans are pre-coordinated. Furthermore, sponsors should consider how communication escalation plans may differ based on the elements of decentralization being used.

PRIVACY PROTECTIONS FOR VIRTUAL CLINICAL TRIALS

Deven McGraw, General Counsel and Chief Regulatory Officer, Ciitizen Corporation

McGraw discussed the importance of protecting participant privacy and data generated by participants, as well as policy mechanisms used in the United States and in Europe to protect privacy. Privacy protections matter, emphasized McGraw, because they build trust and help ensure that people will seek health care and enroll in clinical trials. McGraw noted that one out of six people withhold information about their health because of confidentiality concerns, and as many as two-thirds of adults suffering from a diagnosable mental health disorder do not seek treatment, in part because of fear of disclosure of sensitive health information. Additionally, racial and ethnic minorities express stronger concerns about health privacy, noted McGraw.

Privacy, said McGraw, is about enabling appropriate data use with good data stewardship that engenders trust among trial participants by getting them comfortable with how data will be used and disclosed as a part of the study. Engendering trust also requires investigators to make and keep commitments to trial participants concerning how their data will be used and disclosed. Informed consent plays an important role here, as does honoring the autonomy of the individual participant by being transparent about how data will be used, minimizing the amount of data collected, minimizing who has access to the data, and having some accountability and adherence to policies.

The Role of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

McGraw noted that the terms “clinical trial” and “virtual clinical trial” are not defined terms in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act6 (HIPAA) regulations, though HIPAA does define research as a systematic investigation that has as its primary purpose the development of, or contribution to, generalizable knowledge. In the context of a virtual or decentralized clinical trial, HIPAA covers the identifiable data collected by the investigator if the investigator is a HIPAA-covered entity. Furthermore, HIPAA will apply to the data collected by the investigator even if they originated from a participant’s mobile phone. Whether HIPAA covers data that reside in consumers’ mobile devices, such as a Fitbit or an Apple Watch, is less clear, McGraw said. If the mobile device is given to the participant by the study, for example, the data are likely to be covered by HIPAA, but if the participant is using a commercial mobile device that is not under the control of the investigator, the data in the device may not be covered by HIPAA. However, the Federal Trade Commission does have the authority to ensure that vendors of mobile devices are held liable for data breaches.

In terms of data reuse, new laws in place shift the emphasis to consent, as de-identification is potentially more difficult, noted McGraw. Both HIPAA and the Common Rule7 allow for more generalized consents for future research purposes, but in the context of a specific trial for medical product development, consent likely needs to meet both FDA regulations and Common Rule requirements.

Recent developments in privacy laws, such as California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)8 and the European Union’s Global Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),9 are now requiring more explicit consent and set a higher bar for data to be considered “de-identified.” This is not as large of a concern for primary data collection in a clinical trial setting as it is for onward secondary uses, such as replication of results or additional studies, noted McGraw, because CCPA contains exceptions for regulated clinical trials. McGraw explained that GDPR applies to all personal data collected from individuals within the European Union. Although it does allow for scientific research, data use is subject to various safeguards. CCPA, which goes into effect on January 1, 2020, pertains to data collected from any-

___________________

6 The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 addresses security provisions and data privacy to keep patients’ medical information safe (45 CFR § 164.512(j)).

7 Common Rule: The “Common Rule,” or the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, governs biomedical or behavioral research involving human subjects. Codified into separate regulations by 15 federal departments, the “Common Rule” provides a legal baseline on the standard of ethics by which human subjects research is conducted (45 CFR § 46).

8 Available at https://oag.ca.gov/privacy/ccpa (accessed April 10, 2019).

9 Available at https://eugdpr.org (accessed April 10, 2019).

one living in California. It has some retroactive provisions that sponsors will need to address in 2019 in order to be in compliance by the effective date, McGraw cautioned. As noted above, one exception in the law is for information collected as part of a clinical trial that will be subjected to the Common Rule or FDA regulations, a space that California legislators considered well regulated already. However, she added, subsequent uses of data may or may not be covered by that exception. McGraw said privacy is a hot topic and Congress could engage in this area more actively in the future.

INFORMED CONSENT FOR PASSIVE DATA COLLECTION

Matthew McIntyre, Senior Scientist, Data Collection, 23andMe

McIntyre discussed the particular policy and regulatory challenges in developing informed consent processes for remote studies in which data will be collected passively. Passive data collection, explained McIntyre, refers to data that are collected from a source that is remote from the researcher and that flows to the researcher continuously or at regular intervals. McIntyre focused on three aspects of passive data collection: when the participant is unaware of passive data collection, use of a third-party vendor, and existence of paradata.10

A research participant may not be fully aware of passive data being collected, even if informed consent has been provided, because these data may be collected in the background of some other activity. A concern for investigators is to determine how many details need to be provided to research participants on the type of data being collected. Furthermore, passive data being used for research purposes can come from third party mobile applications, such as Apple HealthKit,11 which typically does not collect data for research purposes. While privacy considerations for passive data collection draw primarily on HIPAA, as well as more recent regulations on de-identification of data for research purposes, participants may have specific concerns that go beyond de-identification, such as who will have access to their data and how their data will be used. Trial participants, said McIntyre, want to have a more complete understanding of the different ways their data will be used, a desire that has led to many of the new privacy regulations policy makers are promulgating. It will be challenging,

___________________

10 Paradata are “data about the data” (IOM, 2015), such as where data were collected, how long they took to be collected, and at what time they were collected. While a participant has given consent for data collection, flow of paradata from the participant to the research investigator occurs without the participant’s effort.

11 Apple HealthKit “provides a central repository for health and fitness data on iPhone and Apple Watch. With the user’s permission, apps communicate with the HealthKit store to access and share these data” (Apple, 2019).

he noted, to develop a way of allowing for mixed uses and sources of data that participants will trust and that will be usable for research.

Handling Paradata

McIntyre addressed the subject of paradata, the additional data collected along with passive data. Paradata can include time stamps, geolocation, digital health technology settings, and other information that could be used in a variety of ways having little to do with a clinical trial. The vast quantity of paradata poses a challenge for researchers to effectively de-identify passively collected data, he explained. His company, 23andMe, faces this challenge with genetic data. There is a vast quantity of genetic data that is nearly impossible to de-identify given that sufficient information about a person’s DNA essentially defines that individual. One current solution, he said, is data minimization—a practice in which only the data needed will be collected. However, paradata can be important for quality control, and data minimization may limit audit trail documentation required by regulatory agencies. It might also take away some of the capabilities of study investigators to monitor safety and protocol compliance, noted McIntyre. This can be crucial in a virtual clinical trial, he added, as an investigator may not always be able to document what is happening with a participant.

McIntyre said that for a traditional trial with a narrow focus, passive data probably do not pose challenges that researchers have not already encountered with other types of data. However, taking full advantage of the opportunity for incorporating passive data in virtual and embedded trials and other research studies may require new policies for mixed uses and sources of data, dynamic ways to inform participants about data collection, and new approaches to seeking informed consent for research uses of data.

DISCUSSION

Raj Sharma, chief executive officer of Health Wizz, started the discussion by explaining that his company has developed a user interface for clinical trial participants that resembles a video game, with badges, prizes, leaderboards, and milestones related to a clinical trial—an approach termed “gamification.” His question was whether this approach was too extreme to be useful in the clinical trials environment. McGraw replied that in her opinion, an appropriate approach is to first develop a clinical trial with its desired outcomes and endpoints, and only then find the technology tool that will help the trial meet its goals, as opposed to developing a tool and then looking for a clinical trial that would benefit from that tool. She acknowledged that a game-based approach might be an effective way to get people

interested in participating and staying in a trial because the user experience could make data entry more fun rather than tedious. She also noted that if such a tool were used in a clinical trial, it would need an informed consent process built into it, and it might be covered by HIPAA, depending on the circumstances.

Andrea Coravos from Elektra Labs asked the panelists to comment on the participant-centered informed consent developed by organizations that may serially use the data collected, such as the All of Us program. McGraw replied that a large effort went into designing the consent process for that program so that it would be understandable and not just a “check the box” encounter. McGraw added that CCPA and GDPR may make mobile consent more challenging because of the amount of information those two sets of regulations will require to be provided to potential participants. Wilbanks noted that several organizations, including RTI International, PatientsLikeMe, and 23andMe, have created effective, mobile, participant-centered consent processes.

John Burch from the Mid-America Angels Investment Group asked Madre if she could talk about the CTTI Registry Trials project.12 Madre replied that this project issued recommendations that addressed two issues on how to conduct clinical trials embedded in registries. First, if the trial uses an existing registry, it is important to ensure that the data can meet regulatory requirements for a clinical trial. With a new registry, the recommendations call for researchers to think more broadly about how to design the registry so it can be used for research in general, and specifically for clinical trials.

Burch then asked McGraw to comment on any changes to HIPAA that Congress might be considering. The legislation under consideration, McGraw said, is not meant to reform HIPAA, but is rather a response to California’s new regulations and GDPR to achieve regulatory convergence with global trends. Those two laws regulate privacy largely by protecting data regardless of its source, rather than the piecemeal approach used in the United States where some data are protected by HIPAA and others by the Common Rule or the Federal Trade Commission. What Congress is considering, she explained, would make the U.S. approach to personal data regulation, including medical data, more like the rest of the world, but there is debate as to whether to regulate globally or allow states to have more stringent laws. The other issue is whether to establish uniform regulations or carve out exemptions for different data sources, such as those already covered by HIPAA. McGraw predicted that this issue will take significant time and effort to solve.

___________________

12 Available at https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/projects/registry-trials (accessed April 10, 2019).

Some individual workshop participants highlighted the significant complexity arising from the variations between state-by-state regulations for distributing pharmaceuticals in the context of a clinical trial. The only solution to this divergence is for Congress to pass legislation preempting state laws, said McGraw.

An unidentified workshop participant asked the panelists for their thoughts on how to enhance public trust in clinical research enterprise if it is going to use data that were not generated in the research setting. McIntyre replied that 23andMe asks people to consent separately to the company’s use of passively collected data, such as from the Apple HealthKit; the general consent that covers the company’s use of their genetic data and health survey data; and other consents that allow the company to share their data with other parties. Use of aggregated data analyzed for research purposes, added McIntyre, is covered by the general consent because there would be no transfer of any information about a specific person. What is not clear, he said, is whether breaking the consent process into pieces makes it easier for people to understand or if it is overwhelming.

McGraw noted that a scientific hypothesis derived from analyzing aggregated data could count as an inference under CCPA, although if that analysis was conducted in the context of a clinical trial subjected to one of the law’s exceptions, the inference would not be subject to the law. McGraw also highlighted the importance of dealing with passively collected data, such as geolocation data, that are collected by digital health technology, but not as part of the trial during the consent process. One issue, she said, concerns the privacy policy associated with the terms of use of the digital health technology being used (e.g., how the data collected will be shared by the technology vendor/manufacturer). Okun suggested not using digital health technologies for which the privacy policies are not acceptable, a position that stands to create a more trusting relationship with trial participants.

McCallie noted the growing movement that takes advantage of the application programming interfaces required of software regulated by HIPAA, such as electronic health records, that make it relatively easy for consumers to download a copy of their medical record onto a digital health technology they control or give proxy rights to a third party to use those data. His question to the panel was whether this approach will change the regulatory landscape in any way. McGraw replied that patient-facing entities, such as a consumer-directed data exchange, would not have the HIPAA compliance hurdles, and they may, in fact, provide the opportunity to more easily reach people who are eager to participate in clinical trials, who are activated, and who have data they want to contribute. The challenge, she said, is to ensure that people are truly informed about how these consumer-facing entities (e.g., apps) will be sharing their data while not placing all of the responsibility for protecting privacy onto consumers. McGraw sug-

gested that investigators using consumer mobile devices could do a better job of choosing the mobile device to be used in research, or at least make recommendations or provide a ratings score that would help people make good decisions about which mobile devices to use.

Wilbanks asked the panelists to address what will happen when technologies designed to monitor safety become inoperable because of an Internet outage, for example. Sacks responded that safety monitoring is not a task appropriately delegated to automation. A clinician’s responsibilities, he said, are to react to adverse events and stop a drug when it is causing toxicity. While automation can do that to a point, it is important that human intelligence is involved in the process. Depending on the criticality of the data collected by an automated system, back-up systems should be involved, Sacks added.

Steven Cummings asked if it was possible for mobile applications to notify participants of updates to consent forms, for example. McIntyre thought that was a good idea, but expressed concern that too many notifications might affect study retention. Asking people to do things repeatedly can cause attrition, he said, so it is important to know what the proper cadence is for requesting that the participants complete certain tasks.