4

The Challenges

The challenges that NASA faces in attempting to reach its desired future was a regular topic throughout the workshop, and it was a particular focus at several points during the presentations and discussions of both day one and day two. The general themes that were touched on again and again included the challenges of attracting, managing, and retaining outstanding innovators; the burdens that the NASA rules and bureaucracy impose on those attempting to move beyond the status quo; and the “failure is not an option” culture and a related fear of failure in many NASA workers. (Communication with the public, while perhaps somewhat off-topic, also came up several times and those discussions are summarized in Box 4.1.) In order to avoid repetition and provide clarity for the reader, this chapter pulls together in one place the descriptions of the discussions about these challenges that took place during various workshop sessions over the 2 days of the meeting. Note that, in addition to the in-depth discussions of challenges that are described here, there were numerous other times when challenges were mentioned more briefly in the context of finding solutions, and many of those discussions are covered in Chapter 5, where the day two sections are discussed more fully.

THE INNOVATOR’S EXPERIENCE

At various points throughout the workshop, NASA innovators and former NASA innovators spoke about their experiences at the agency and the challenges they faced in doing their jobs. Two of the most in-depth discussions occurred during the Leadership Diagnostics and the Career and Talent Management breakout sessions.

Dealing with the Bureaucracy

The Leadership Diagnostics breakout session on the first day of the workshop had two main purposes, said Mona Vernon1 of Thomson Reuters Labs, who led the session. Speaking in the plenary session on the workshop’s second day, when the results of the Leadership Diagnostics session were summarized, she said that the first purpose was to introduce the session’s participants to an approach to innovation called design thinking, which she described as “a really transformational capability that has changed our company.” To this end the participants went through an exercise in which they were given two very similar design tasks phrased in different ways, one of which specified a particular product while the other specified only a function. The second design challenge resulted in much

___________________

1 Ms. Vernon is now employed at Fidelity Investments.

more creative designs than the first, and the lesson was that how a problem is framed plays a major part in how people approach solving the problem.

The second main purpose of the session, Vernon said, was to gain insights from how “persistent innovators”—people who have maintained a high level of innovation for many years—operate within NASA. In order to gain these insights, the session participants were first instructed in a particular way of learning from others that was based on getting people to tell relevant stories and then listening carefully to those stories and engaging with them. Then the breakout session’s participants were divided into five groups, with each group assigned a persistent innovator to speak with as a way for the participants to practice what they had learned. A number of the persistent innovators were current or former NASA employees. All of them offered interesting and inspiring stories, but it was the story of the difficulties faced by a former NASA employee that caused the most discussion over the course of the workshop.

That employee worked for NASA for 13 years on emerging technologies for propulsion. The story she told was of an innovator who loved what she did and loved working for NASA but eventually got worn down by all of the unnecessary negative aspects of her job. For example, in an early design review she was surprised to find that she was subjected to questions from some of her peers—specifically from a group of detractors whom she described as a faction working against her initiatives. “I felt physically ill,” she said.

Generally speaking, she said that there was a sense of competition among the people she worked with and that they would “passively resist” her projects because of the perception that if her project got funded, other projects would not get funded.

“I really believed that pushing the envelope was the way to change the culture,” she said. “I thought I would never leave NASA.”

But she did, and she attributed it to a combination of factors. For one thing, the commercial space industry exploded, and there were suddenly a number of interesting projects going on there. Meanwhile, she said, she stopped believing that the things she was designing were ever going to launch. Even though she chose to leave NASA, she said that she still wants the agency to succeed and that she is still passionate about the future of propulsion.

When asked about a good memory from NASA, she said that she remembered all the hard work and seeing the crew being appreciative of the work they did. “I framed the e-mail from one of the crew to me,” she said, “and it is still in my office.”

She was also asked whether she thought her project would have been successful if she had gotten to choose the people working on it. Yes and no, she said. She appreciated the diversity of the team, but she didn’t have the chance to pick people who could be successful and learn, and she found that not everyone who was chosen for the project wanted to jump in and embrace it.

When asked what she was particularly surprised by in her experiences at NASA, she answered that it was the fact that “every SES [Senior Executive Service member] believed in our project” but none of them had the funding to support it.

She joined NASA because she wanted to work on human space missions, she said, and she loves to innovate, particularly on “cool” projects. She still believes in the values of NASA and still supports the agency, although she is perhaps not as idealistic about it as she once was. In her years at NASA, she said, she found that the technical problems were solvable, but the people problems were almost impossible.

Fear of Failure

A frequent theme throughout the workshop was the image of NASA as an organization where “failure is not an option,” which was both a famous line in the movie Apollo 13 and the title of an autobiographical book by Gene Kranz, the former flight director and, later, director of mission operations at NASA. The phrase initially was used to refer to the importance of doing everything correctly when human lives are on the line, but, as a number of people commented throughout the workshop, it grew to have a much broader meaning—that, at NASA, any sort of failure is something to be avoided—and this in turn has led to a culture where fear of failure is common.

This was the topic, for instance, of a discussion during the Career and Talent Management breakout session on the workshop’s second day. A comment had been made about the importance of creating a safe space for innovation, and a workshop participant responded by describing her own experience at NASA. “You’re absolutely right about creating a safe place,” she said. “I am where I am in my career because I had a supervisor who did not hold it against me when I failed. I failed. I did not meet his expectations. I then continued the task, got it accomplished, and he hired me into my first SES job.” However, she continued, she does not believe that her experience is the norm at NASA. “The problem I have with NASA,” she said, “is that until he came to the agency from outside, we did not have that. We didn’t have anyone who did that [allow people to fail], and I still have people in my office who are fearful of trying because they don’t want to get me upset. It’s still a culture. They are very fearful of trying and failing.” Ironically, she added, that very fear of failure is likely to end their careers because they are not likely to accomplish enough to be retained.

Janice Fraser of Bionic, who was leading the discussion in the breakout session, said that she had heard about this sense of fearfulness at NASA not just at the workshop but even in the planning sessions leading up to the workshop. “I have heard some people in the lead-up to this event say, ‘Well, I’m going to get fired for this’ and there was a frisson of actual fear. It wasn’t just a throwaway statement. I wonder why that perception exists.”

In response, a participant commented that the punishment for failure is not necessarily getting fired—and, indeed, that it’s actually not common to get fired at NASA. “What happens is you don’t get the key assignments,” she said. “You get sidelined. And then your ratings are affected, because you’ve irked somebody.” “In industry,” Fraser said, “I have called that the ‘velvet penalty box.’ And it can last for the rest of your career.”

Another breakout session participant said that he was happy that the group was having this discussion. He said he had just been talking with someone in the hall and had commented to that person that “I hadn’t yet heard the word fear in the workshop.” But now, he continued, “I’ve heard it like 10 times in the last couple of minutes. This is a great conversation to be having.”

Yet another session member echoed that comment, saying that the previous evening at the reception she had spoken with several people who had made a very similar comment about fear. “Lots of people [were] talking about exactly this: I might not get fired, but I’m probably not going to be picked for that project or that role, and I was too afraid to bring that up in the room. It’s very, very real.”

ORGANIZATIONAL ISSUES

The most detailed discussion of the challenges facing NASA in its quest to remain a top-tier innovation organization was provided in the Program Leadership and Management session on the morning of the second day by Michael Gazarik, vice president of engineering at Ball Aerospace and previously the associate administrator for NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD, also known as Space Tech). He described his hopes for Space Tech and also some of the challenges he encountered during his time there.

The original purpose of Space Tech, which was set up in 2011, was “getting NASA back to its roots, getting to failing fast, getting to pioneering on the edge, reconnecting with the academic engineering universities throughout the nation,” Gazarik said. He experienced both successes and failures during the 4 years he was there, and he told the group that he would be honest with his opinions. They should keep in mind that his goal was to help, he said. “My passion is to make [NASA] better.”

In the years leading up to the founding of STMD, Gazarik said, NASA’s research and development (R&D) orientation had been cycling between basic R&D and project-specific R&D. Part of it was due to shifting budgets as Congress trimmed some programs and beefed up others, but Gazarik said it was also about culture and about changing the way the agency had been going about its business. Even today, he said, “the battle continues over the heart and soul of technology and culture and innovation at the agency and what the stakeholders in the community really want NASA to do.”

Around 2010, he said, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine was commissioned to examine the question of how NASA was carrying out its mission and what that mission should be. The resulting report led to space technology roadmaps for NASA, but the report also found that the technology cupboard at NASA was bare and that the demands of carrying out missions often led to future-oriented work being neglected.

“I think that’s still true today,” Gazarik said. “I think it’s true in a lot of places.” The question, then, was what could be done to protect technological innovation at NASA. The report called for NASA to return to its roots of pioneering advances, taking risks, and failing quickly. It also called for the agency to re-engage with academia and the university community. At the time, Gazarik said, university engineering departments had largely stopped working on NASA projects, in part due to a lack of steady research funding over time.

Gazarik showed a slide on risk that he used around 2011 as a way of showing the thinking at the time that STMD was created. The slide made the distinction between the “failure is not an option” mindset that was necessary in spaceflight and other areas and the appropriate mindset in technology development and testing, where failure is—or should be—an option. The slide mentioned “failing forward” as a way of garnering knowledge and experience even when a particular test or technology did not pan out, and it offered a quote from a Sandia National Laboratories publication: “Risk intolerance is a guarantee of failure to accomplish anything of significance.” In short, at that time it was clear to some at the agency that failure—as long as it was done in such a way to advance knowledge—was a necessary part of innovation. However, Gazarik said, there were challenges getting that message to resonate.

Regarding how the effort to take NASA back to its roots went, he continued, “I don’t think it went as well as I had expected,” he said. The agency tailored its approach to risk management and the portfolio using existing tools and standards, such as NM 7120-81, NPR 7120.5D, and NPR 7120.8. “Each center, and even organizations within each of the centers, had a different approach to the tailoring process,” Gazarik said. “Anyone who had a project in Space Tech had to work the entire leadership chain to do the tailoring, and it was completely wearing out the projects and programs.” The exception was when leaders embraced the opportunity to modify how they managed technology development.

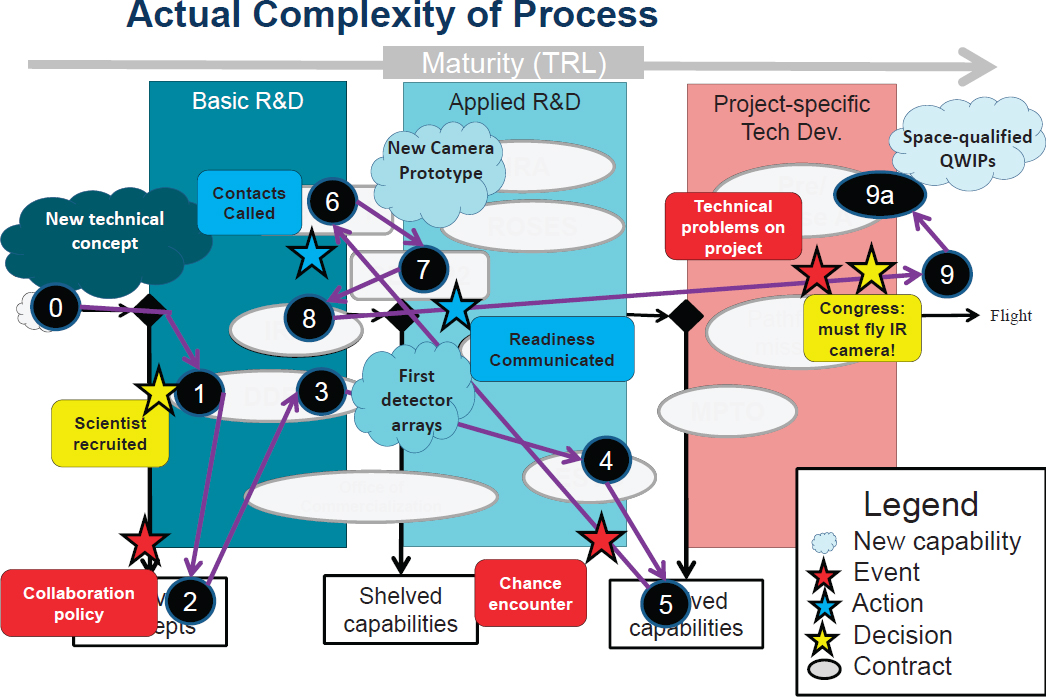

Gazarik then showed a slide, based on the work of Zoe Szajnfarber, that traced the process of one particular project, a new type of camera at NASA (Figure 4.1). The typical conception of a technological innovation, he said, is that it proceeds linearly from basic R&D to applied R&D to project-specific technology development, but this one bounced back and forth in a very nonlinear manner. It would advance for a while, then it would stop. It would go backward, then forward. And when the project would advance, Gazarik said, it was thanks to the efforts of one or two champions. The lesson he took away from the experience was that successful technology innovation at NASA depends on stable funding and reliable champions. The whole process is nonlinear, he said, so using linear management concepts is not going to work.

Looking back on the effort to create Space Tech, Gazarik spoke of how he and his colleagues went back to Congress several times trying to get a budget. Over time they learned to tell a better, more convincing story, and eventually they succeeded. The Obama administration was a major supporter, he said. “In the end, the hardest part was getting the buy-in of the centers and the workforce,” he said.

Now, from his perspective as part of the private space sector, he said, “I see the broader aerospace ecosystem, I’m part of it, and I think the agency still has some work to do in the area of technology development.” He qualified that statement by saying that he appreciates NASA’s missions, but in terms of fundamental technology, some in the industry do not see NASA as a leader in many areas.

Generally speaking, he said, it is his observation that NASA tends to focus inward. The agency follows its own path and its own interests. A related issue, he said, is that it is very difficult to stop projects at NASA, even those that clearly should be shut down.

To illustrate some of these issues, Gazarik told a brief story about supersonic retro-propulsion technology that involves firing a jet into a supersonic flow. It was an interesting technology because it could be used to slow a vehicle for a landing on Mars, where, because of its thin atmosphere, it is difficult to land anything that weighs more than a metric ton. “We turned to NASA Langley and said, ‘We’ve got to figure this out.’ What we got back was a multi-year, multi-million-dollar program, step by step, very conservative, very slow, very expensive. And we said, ‘We don’t have that kind of time.’” So, he said, they made a deal with SpaceX, and for a million dollars and a trading of some imagery, “we solved the problem in less than a year.”

There have been successes at Space Tech, Gazarik said. For instance, there are a number of new Tipping Point partnerships between STMD and private U.S. companies to develop future space exploration technologies, including a lunar lander and deep space rocket engine technologies. There has also been increasing engagement with research universities.

To conclude, Gazarik offered several closing suggestions. Work on the right problems—they should be challenging and relevant. Get external—make connections with innovators outside the agency. Reduce reporting—a certain amount of reporting is necessary, but beyond that it uses time and resources that could be applied to innovation. Reward doing—the best way to get more of something is to reward it. To close, he quoted Betty Sapp, the director of the National Reconnaissance Office, who said, “The ratio of doers to reviewers is off. We need to change that ratio. It needs to be more doers and fewer reviewers.”

In the final plenary session of the workshop, one participant echoed Gazarik’s point. He identified himself as having been in the business for 31 years, the first 17 at NASA and the last 14 in the NASA family. He said he understood the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) viewpoint about what innovation is and said that a DARPA-type process is what NASA needs. “It is not technical solutions we need,” he said. “We do that all the time, and we’re really good at it. What we need is to change this bureaucracy—this semi-moribund agency that is comprised of people who love it and love what we do, but which is on a path that we saw defined yesterday to partial irrelevance or being sideswiped by other entities that are now starting to do some of the things that we do, may even overtake us in some areas. And it is not just technical innovation we need. It’s institutional innovation. It’s behavioral innovation. And it’s innovation of expectations about who we are, what we mean, and how we operate.” The audience in the auditorium erupted into enthusiastic applause.

Daniel Dumbacher, the executive director of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, who was moderating the session, replied that the comment dovetailed with the other comments about technical fixes.

“I think there’s some common ground here,” he said. “Unless we fix the process side of things, we can’t get to the technical side right now because of all the things that were just said—there is such a constraint on how we secure things, how we buy things, how we support them, how we get people, how we get talent in and out of the system. All of these things I think are true, and I think they are the supporting mechanisms for the important mission.”