5

Strategies and Tactics for Creating the Desired Future

Following a first day that was devoted primarily to discussing what the future of NASA should look like, the workshop’s second day tackled the question of what was needed to build that future. To that end, the workshop participants were divided into four parallel breakout sections that lasted much of the day. The topics of the four sections were Career and Talent Management, Portfolio Management, Program Leadership and Management, and Classical Enablers and Impediments to Innovation. The morning portion of each breakout section included presentations by outside experts followed by a discussion period; the afternoon portion of each section had an exercise (different for each section) designed to produce a large number of ideas for how NASA can reach its 2030 goals. These parallel sections were followed by an afternoon plenary during which representatives from each breakout section briefly described what they had heard from the experts’ presentations and listed some of the ideas for actions that had been generated. That was followed by a general discussion of some of the general themes that had appeared at the workshop.

As a result of a day two format with four lengthy parallel sections, workshop participants generated a great deal of information and a large number of actions, and no single person attending the workshop was exposed to more than a fraction of it. This chapter provides a summary of the presentations in the four sections and a sampling of the ideas developed by the workshop attendees. Most of the details are drawn from the breakout sections themselves, while some are pulled from the summaries and discussions of these sections that took place during the following plenary session, and the sources of the various comments are given.

CAREER AND TALENT MANAGEMENT

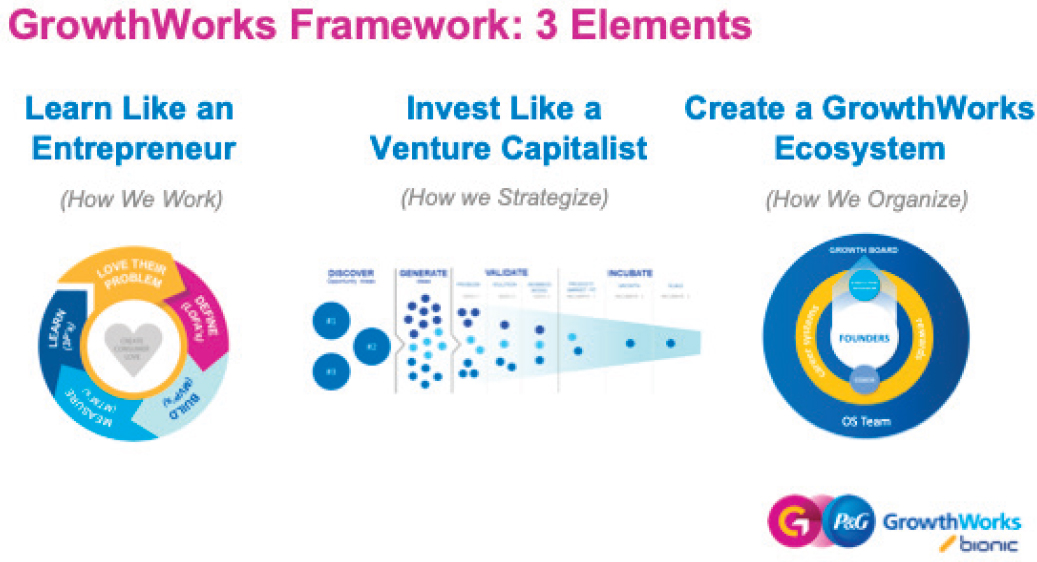

The breakout section Career and Talent Management was led by Janice Fraser of Bionic and Bob Gibbs of NASA. Fraser began the morning portion of the section with a description of four principles, or pillars, that Bionic emphasizes to organizations interested in improving their innovation. That was followed by a panel discussion featuring Erika Long of Procter and Gamble (P&G), Atherton Carty of Lockheed Martin Advanced Development Programs (better known as the “Skunk Works”), and Colonel Rhet Turnbull of the Space Superiority Systems Directorate of the U.S. Air Force. The afternoon portion was devoted to an ideation session in which participants went through a structured exercise to come up with a variety of ideas for improving innovation at NASA.

Four Pillars of Organizational Innovation

Fraser began by describing a model for buy-in, although she noted that she generally avoids using that term “because it’s nonspecific. You think you have it, and then you forget to keep it, and it goes away.” Ideally, she said, buy-in should take place in four steps, beginning with understanding and then moving on to belief, advocacy, and decisions. Belief is the solid foundation on which everything else should sit, she said, and she added that she includes actions as part of decisions since every action is a form of decision.

The best-case scenario is that buy-in follows that sequence—that people understand something before they decide to believe it, before they decide to talk about it and advocate for it, before they make decisions based on it. “But often,” she said, “for very good reasons we have to make decisions before we fully understand what it is that we’re signing up for,” and the problem then is that “that’s a fragile form of buy-in because if we make a decision and we don’t really understand it, when we finally do understand we may not believe it, which means that we might unmake that decision.”

That model, Fraser said, can help explain why people who talk a good game might never actually take any action—they might not truly understand or even believe what they’re advocating for. But a person who has a deep understanding of a subject and speaks with a passion that is rooted in that understanding is more likely to truly believe in something and take action. So Fraser asked the participants in the section to keep that model in mind during the section’s discussion of talent and innovation and to think about their own understanding and beliefs and whether they truly intend to take action on those beliefs “so we can diagnose our own buy-in as well as keeping an eye out for others.’”

Fraser then moved into her discussion of her four pillars, or what she described as the “philosophical underpinnings for the organizational transformation that fosters innovation.” Her company, Bionic, has been working with P&G to transform its innovation culture, she said, and those four principles underlie the transformation that is taking place at P&G. “I’ve used them with a variety of other companies as well,” she added.

The four pillars are as follows:

- “Pigs” and “chickens” both need food

- Safe to try

- Do the easy thing that’s good enough

- Team performance over individual

“Pigs” and “Chickens” Both Need Food

The first pillar, Fraser explains, comes from the business parable, “When it comes to making a breakfast of ham and eggs, the chicken is involved, but the pig is committed.” In short, when a company is undergoing some sort of change, some employees will be truly committed to the change—they are “all in”—while a much larger group will be involved, or affected by the change, while not being totally committed. The principle expressed in the first pillar is that all of these workers, both those who are committed and those who are involved, must be taken into account in the planning and execution of a new program. Often, Fraser said, those who are involved but not committed get mostly ignored at such a time. “We try to feed the pigs, and then we forget the chickens,” she said. “The chickens peck your ankles, it hurts, and you get frustrated.”

At a place like NASA, the pigs would include the persistent innovators and “the people who support and make room for the persistent innovators, who are trying to make the hard organizational change.” They tend to get most or all of the attention during a change because they are driving it or most intimately affected by it. The chickens, by contrast, are “those people around the agency who are not directly involved in radically changing or even incrementally changing the status quo, who instead are keeping humans alive in space” or those working in the legal department or in compliance or in some other part of the agency that will be affected in some way by the change. These people may have understandable concerns or questions about whether the changes are somehow going to hurt their ability to be successful, Fraser said. They have a “legitimate need to feel safe and secure in their current situation,” she said, “and we have to respect that and take care of that.”

Safe to Try

Fraser characterized the second pillar, “safe to try,” as probably the most important for those at the workshop, based on what she had heard in the previous day and a half, and it certainly seemed to generate the most discussion of the four pillars. “By any means, we must create circumstances of real and perceived safety for everyone involved, and for the organization at large,” she said. In particular, she said, an organization’s innovators must believe that it is safe to try, and she noted that the phrase was deliberately written to be ambiguous. Try what? “Big things, little things, process changes. It has to be safe to say, ‘Do we need this regulation? Do we need this level of specificity?’” No one’s career should be threatened by questioning and trying something different.

A NASA employee in the section expanded on Fraser’s point about the importance of being able to question established methods. “Do we have to be A-plus students in everything that we do?” he asked, arguing that the impulse to always be A-plus students can have a “chilling effect on innovation.” He described an experience in which he and a colleague had been talking about delegating hiring authority to carry out some pilot projects or demonstrations at the different NASA centers. “And my folks came back, trying to get an A in compliance,” he said, “and what they had done was they had narrowed that authority and approached it from a perspective of not letting too many people use it. That’s exactly wrong from an innovation perspective.” Unfortunately, he said, that sort of approach is common at NASA—people focused on following the rules precisely just for the sake of following the rules. “What do we get for that?” he asked. “What’s the investment to get to that? What’s the chilling effect on innovation?’

Fraser responded that she really liked his story because of the attitude it expressed. “That’s an innovator’s attitude,” she said. “You’re saying, ‘I’m going to ask a little bit of forgiveness, instead of a lot of permission.’” She also liked the fact that the NASA workers were trying to do the right thing as they understood it, she said. “The world is made up of regular people,” she said. “We are all regular people. And regular people want to do the right thing.” However, she added, regular people are also natural innovators, and if just a few adjustments are made to the system—adjustments that might initially be uncomfortable to those regular people—it can unlock a tremendous amount of value.

To create real and perceived safety for everyone at NASA, Fraser said, the agency’s leaders will need to see their jobs differently—not as making sure that everyone under them is doing what they are “supposed” to do, but rather making it safe for them to accomplish their goals. She paraphrased a comment she had heard in a workshop session the day before. One of the participants was describing how leaders in his organization approached their work: “They meet monthly, they review progress, and they have really one function there, one question that they ask: What can I unblock for you?” she said. “That’s their job, and it’s not about oversight. It’s not about ‘i’ dotting and ‘t’ crossing.” That is a different approach to leadership, Fraser said. It is an approach to leadership that is focused on discovering rather than on knowing.

In most organizations, Fraser continued, people are promoted for being the expert, for knowing the right answers. And, she said, she had heard various people at the workshop say that that approach is common at NASA as well. But an innovation-focused organization requires different things from its employees, which in turn requires a different approach from managers and leaders. “The kind of service that [leaders are] providing is not a knowledge-based service,” she said. “It’s a discovery-based service and an unblocking service.” A key role of leaders in such an organization is to remove roadblocks so that others can deliver maximum value from their ideas.

Not only management teams but also human resource (HR) teams should follow this principle, Fraser said. Unfortunately, she added, “this is the opposite of how HR folks tend to think,” and changing how HR functions can be a major challenge. Nonetheless, it is a challenge that is important to take on.

Do the Easy Thing That’s Good Enough

Fraser described the idea behind her third pillar, “Do the easy thing that’s good enough,” as taking the fastest path to the most value. As an example, she mentioned the stories that had been discussed earlier in the workshop about the approach that SpaceX has taken to develop its space transportation capabilities. The company is launching its rockets regularly, and if a rocket crashes, it is not a major failure for the company, because the financial risk is

low. “They’re doing the inexpensive, ‘easy’ thing that’s good enough to just get that next incremental learning,” Fraser said. The early launches in particular might have seemed like failures from the outside because the rocket didn’t behave the way it was supposed to, she said, but SpaceX didn’t care, because the goal wasn’t to get the rocket off the ground—it was to find out whether particular parts worked as planned. So the “failures” were treated as learning experiences rather than true failures.

To put the third pillar into practice, Fraser said, NASA should “make expedient decisions to give people the safety and freedom to create and grow new businesses.” Doing this will often involve implementing short-term fixes that are neither sustainable nor scalable, she said, but that is just fine. At this point, rigor and scalability are red herrings. If a new business becomes successful and begins to add staff in large numbers, it will then be time to figure out how to scale up the different systems. But until that point, the idea is to create “good enough” solutions—what Fraser termed “patches”—that will support a population of a few dozen “pigs” and a few hundred “chickens.”

In response to a comment from a member of the audience, Fraser clarified what she meant by “easy.” Different people define it in different ways, she said. For some, “easy” might mean the path of least resistance, for example, but that just leads to sticking with the status quo. For the purposes of this pillar—Do the easy thing that’s good enough—the idea is to look for the fastest, most efficient way to take the next step along the path, she said. “So we’re going to do an increment of work—what is the smallest amount of work we can do to meet the learning objective we have?” That smallest amount of work that gets the job done is the “easy thing.”

Team Performance over Individual

The final pillar, “Team performance over individual,” concerns how performance is evaluated in an innovation environment, Fraser said. Innovation is a collective endeavor, she explained, so “individual effectiveness is valuable only to the extent that it contributes to team effectiveness.” This means that individual performance evaluations should strongly reflect how an individual performs within and contributes to a team.

To illustrate, Fraser told a story about an experience she had while working with a software company. The company is very focused on teams, it thinks a lot about team dynamics and team behaviors, and it is optimized for team behaviors in very specific ways, she said, and yet there were still teams at the software company that were not particularly functional or effective. In analyzing what made some teams good and some not so good, she and her colleagues found that there were certain individuals who made every team they were on better.

In particular, she noticed a young man named “Alan.” Although he was very smart, he “didn’t really present as an intellectual giant.” He would misspell words on slides and make other mistakes that would generally cause him to not be advanced very quickly. “But we noticed that every team he was on was great,” Fraser said. “He’s a designer, and we noticed that every time we paired him with a young designer, that designer became a [key player] faster.” So where it might take a normal hire 6 months and two projects to reach that level, designers who worked with Alan were generally working well and independently within 2 months. This and similar experiences led the company to make it a policy to recognize those people who, like Alan, would make others great.

Eventually, Fraser said, the company made Alan a manager. A few years later, he returned to an individual contributor role, but at a much higher level and with a tremendous loyalty to the teams he was on. “He’s one of these Gen Z people who would have left after a couple years, had we not noticed the behaviors and noticed the effect he had on everyone around him,” Fraser said. “So that’s my story about team over individual.”

In response to Fraser’s fourth pillar, one participant noted that there are many structures within the federal government that make it difficult to make team performance a major part of individual evaluations. “This is not unique to NASA,” Fraser replied. But one difference between NASA and business organizations is that it can be much more difficult to change systems and processes in a federal agency. Indeed, some of the systems may be essentially impossible to change. So it will be important to understand which can be changed—and to what extent—and which cannot.

Another participant suggested that managers do have one important tool with which to recognize and reward team performance. “We have to use the performance system and document that stuff, and that is all on an individual basis,” he said. “But the thing that motivates people at NASA is the ability to work on a fun project, and that’s not

part of the individual performance management system. That’s at our discretion.” In short, managers can reward individuals for their value to team performance by helping them get assigned to desirable projects. That ability, he said, “is a very powerful incentive that we can use any way we want.”

“Can I just add that it’s not just fun projects, but it’s the fun teams?” another participant added. Even if a project isn’t going into space, and even if the assignment is just working on strategic workforce planning, he said, if it’s a good team, people will want to be part of it, and they can be rewarded in that way.

Career Paths and Advancement

After discussing the four pillars, Fraser spoke about the general patterns of career paths and advancement, which she illustrated with a slide describing Bionic’s talent management system (Figure 5.1). From an organization’s point of view, she said, the first step is to attract the right people and then to figure out whether a potential hire is the right match. From what she had heard at the workshop, Fraser said, it seemed to her that NASA had a lot of process devoted to this recruiting and screening—“perhaps too much.” After hiring workers, an organization must develop them with coaching, feedback, and various experiences. If they grow appropriately, they are promoted, and they must still be supported in various ways—coaching, sponsorship, feedback. The developing and supporting of workers is “about feeding your pigs and chickens,” she noted. And the organization must also work to retain their workers with incentives and other methods. It is a basic model that provides a way of thinking about an organization’s talent management system, she said.

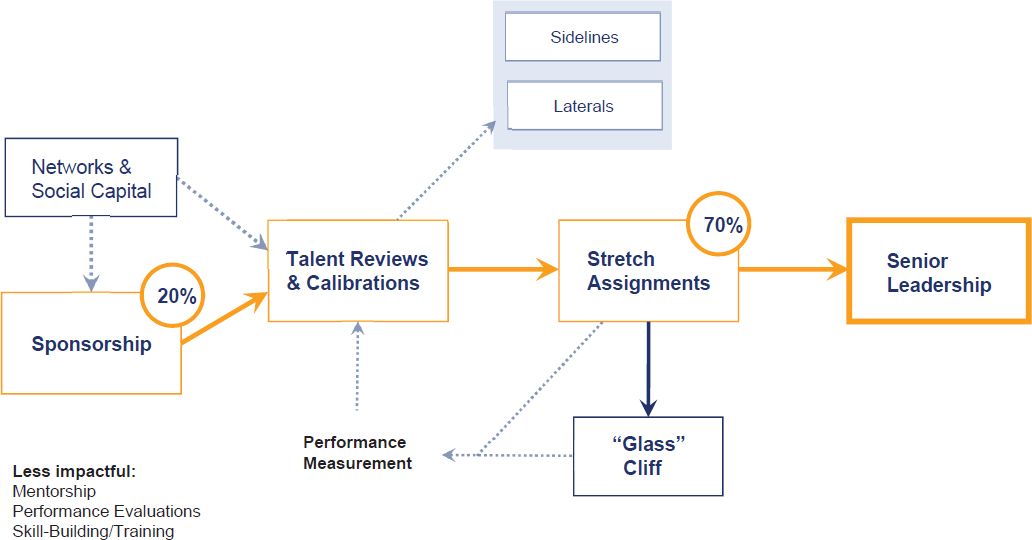

From there Fraser moved to a different model of how careers work, one that was more focused on promotions and advancement (Figure 5.2). That model, she said, was based on a literature review done in 2016 that looked at about 30 different studies. “If you look at what leads to senior leadership roles in general,” she said, “70 percent of advancement comes in the form of a stretch assignment, which is giving someone the opportunity to do something they had not previously had the chance to try.” This is where making it “safe to try” really comes into play,” she said, since it is the people who take on stretch assignments who typically get advanced in an organization.

Another 20 percent of advancement comes in the form of sponsorship, Fraser said. Sponsorship can come in different forms. One form of sponsorship, for example, is helping people get the right sorts of assignments—those that will help them advance. Another type of sponsorship is protecting workers—giving them the chance to fail and then protecting them from any negative repercussions if they do fail.

The final 10 percent of advancement, she said, relies on some combination of performance measurement, mentorship, performance evaluation, skill building, and training—in short, all of the things that are normally considered to determine advancement. It turns out that, when you look at the statistics, these factors actually have much less to do with advancement than stretch assignments and sponsorship, she said, and she reiterated that this was not her opinion but rather the finding of research on a large number of organizations.

Fraser concluded that part of her presentation by saying that she had not done any studies specifically of NASA to see how much of this applies to the agency and asking the participants to comment on the model as it applies to NASA. “Where does it match and where does it not match?” That led to a lively discussion about careers and advancement at NASA.

A number of people in the group agreed that stretch assignments play a major role in advancing at NASA. “If you’re defining a stretch assignment as something that is a very difficult assignment, really pushing the envelope,” one participant said, then Fraser’s model captures the reality at NASA “because those things get noticed, they get recognized, and the individuals who are pushing toward senior leadership, they developed sort of a reputation.” Another participant echoed that opinion: “The majority of your good reputation is difficult assignments—doing things that haven’t been done before, coming up with a different idea or approach to something that’s completely not what we’ve experienced before.”

That participant added a comment about Fraser’s “safe to try” pillar as it applies at NASA. “There’s kind of a small safety zone where it is okay to fail,” she said. “But it doesn’t go all the way up to a general safe zone to make new mistakes, and then once you make a mistake, you end up at the gulag somewhere.”

Fraser responded by pointing out that in her model the “gulag” is part of what she terms “sidelines and laterals.” This is an alternative career path for people who are not given stretch assignments and are thus not given the chance to move up the usual career path. “A lateral is a move from one position to another at the same level,” Fraser said, “and often laterals lead to sidelines [or the gulag], and it’s a way that your career can stumble.”

That then led to a discussion of the difference between lateral assignments and stretch assignments. Several participants noted that at NASA what is called a lateral assignment is actually a stretch assignment—that is, an opportunity to take on new challenges and to learn and grow in new ways.

Fraser explained that her model was originally developed when she was trying to understand why women and underrepresented minorities were not advancing into positions of leadership, and what she found was that being given lateral assignments was one way that people found their careers stymied. So the lateral moves in her model are what might be called “non-growth laterals,” in contrast with what she called “rotational stretch assignments,” which shift people from one place to another in an organization with the goal of having them extend their skill set or their understanding of the organization. Although they are lateral in the sense that they do not involve promotions, such moves should be thought of as stretch assignments. And, indeed, she said, such rotational stretch assignments are among the best ways to help workers in an organization grow.

One participant said that NASA often refers to these lateral moves that are designed to help people stretch as “detail growth opportunities.” Sometimes they are advertised, she said, and sometimes they are just created and do not come with a promotion, so in a sense they are lateral assignments, but they are very different from the sort of going-nowhere assignment that is referred to as the “gulag.”

One participant posed a question for the people from NASA. “Not everybody wants to go up the ladder,” she said. “Not everybody wants to be a senior leader. So my question is, What’s in place for NASA to support those folks who don’t want to be in [a senior leader] position someday?” A participant answered that the general pattern in federal agencies is that it is necessary to take on supervisory management responsibilities if one wishes to advance through the General Salary (GS) pay scale. However, he continued, some people at NASA are working hard to get exceptions to these rules. “So if you just want to be the technology expert in this role,” he said “we want to be able to advance you as far as we can. I think that has to be rewarded as well, and it has to be recognized as well. Often we put people in the senior leadership positions who want nothing to do with it. Wouldn’t it be really great if all of our senior leaders really want to manage people?

Continuing, he noted that the GS scale is a very old structure. It was created in 1949 and redone in 1976. If the system were a person, he noted, it would be 3 years past retirement age. “How many of you are driving a car from 1949?” he asked, and he said that the GS system should be placed into the category of “stop doing stupid.”

Another participant commented that there is one NASA center whose human resources are not operated under the federal system. That is the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), whose employees are not federal workers but rather employees of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). “A few years ago, HR [human resources] at JPL went through an enormous push to restructure the levels and the incentive system to beef up the attractiveness of the individual contributor path,” he said. “So I would say today there’s a much more open recognition that management and managing people is not something that most people at JPL would ever want to do or should want to do, and that that’s just fine.” As a result, he said, the pay structure and the perk structure at JPL have been reworked in an effort to bring the individual contributor track into parity with the management track so that JPL employees do not have to become managers to advance.

On the other hand, another participant said, JPL has a variety of issues that other parts of NASA do not have to deal with. “JPL has to work under the NASA rules,” he said. “They also have to work under the Caltech rules, and the most restrictive of all, under the California state employment rules. So when you layer in all of these rules, there’s a lot of restrictions that I don’t necessarily have with the federal workforce. So it isn’t always grass being greener on the other side.” The same sort of observation applies with the private sector as well, he said.

Returning to the idea of the gulag, Fraser suggested that it might be a good place to find innovators. “Mine the gulag,” she said. “If you want to look for misfits, people who are not toeing the line, that are getting in ‘trouble,’ those are the people who actually have ideas and are willing to take risks.”

A participant commented that she does believe that some of the workers in NASA’s gulag are people whose talents have not yet been identified, but she cautioned that this does not apply to everyone in the gulag. Many of the people in the gulag are there because they do not have the skills to be successful at what they want to be. “They are where they are because they’ve just decided to check out,” she said. “I don’t know how we deal with that, but that’s what I see in our group.”

Fraser suggested that some of these people may be frustrated because they have no interest in managing—and perhaps no skills at managing. “I think that when you have multiple ways to get ahead, multiple ways to have satisfying careers, people will stop aspiring to jobs they’re not suited for,” she said. “Often we aspire to the job that is at the top because that is what has been socially deemed the path forward, the way to get ahead.” Often the system does not give certain types of people ways to excel. “We want to make little boxes that, if you’re going to be extraordinary, you have to look and act like this,” she said. “A different type of system—one that also rewards and recognizes senior individual contributors—could give more people the change to contribute and to excel.”

PANEL DISCUSSION

Following her presentation, Fraser invited Erika Long, Atherton Carty, and Colonel Rhet Turnbull to the front of the room for a panel discussion on talent management in innovation organizations. Each spoke briefly about his or her work, and then they had a wide-ranging discussion on what it takes for innovation organizations to excel.

Turnbull, an active colonel in the U.S. Air Force, said that he had been working at the Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center at Los Angeles Air Force Base in California for about 3 years. About half his career has been in the space business, he said, and the other half in building nuclear weapons.

“The Space and Missile Systems Center shares a lot of similarities to NASA,” he said, “so I feel your pain. We are also undergoing a major transformation right now.” The center employs about 5,000 people, he said—about 60 percent of whom are civilians and the rest active-duty military.

Carty leads the technology roadmaps organization within the Advanced Development Program (the Skunk Works) at Lockheed Martin. His organization serves as an important piece of the “innovation engine” for Lockheed Martin, he said. Many of the programs that Lockheed Martin has been best known for over the years, such as the F-22 and the F-35, were designed, developed, and tested in the Skunk Works.

“I’ve been with the Skunk Works over 21 years now,” Carty said. “In that 21 years, I’ve had two or three dozen jobs. That’s one of the things that I love about the organization—that there’s a lot of ability to push into different areas that you don’t have expertise in, develop yourself, grow yourself, garner new opportunities based on your ability to adapt and change.” His technology organization is responsible for a wide range of technologies, he said, from those with very low technology readiness levels (TRLs) to mature technologies. “We try to be very intentional about cultivating and incubating very-low-TRL technologies and growing them into things that can be matured,” he said. “And then there’s an element of the portfolio that also focuses on conceptual design, which we consider a core competency of what we do at the Skunk Works—the design process of how you create a new system solution, a new aircraft solution.”

Long said she had been with Procter and Gamble (P&G) for 8 years in human resources, where she supports P&G’s R&D group. For 3 years, she said, P&G has been working to bring lean innovation into the company and transform how it innovates. “We learned early on in the journey,” she said, “that there were some human systems things that needed to change about the company in order to enable this new innovation ecosystem.” She is part of a team that is experimenting with different human systems across the company to determine how best to improve innovation.

Procter and Gamble

After the introductions, Long began the discussion by describing the process that P&G has been going through. At the beginning of the process, she said, she and her colleagues got in touch with the people who were going to be involved—both the pigs and the chickens. “I think that was really important,” she said. “We talked to the innovators, but we talked to the managers, we talked to the leaders to hear what was standing in their way about our systems or processes or culture or organization. We got really clear on the problems to solve.”

From those discussions emerged three “work streams” that needed to be focused on, Long said. The first was leadership and leadership behaviors. P&G learned that entrepreneurial management is a different discipline than general management, with different demands and different required capabilities. P&G is working to develop those capabilities through external coaching with Bionic, Fraser’s organization. “We learned that we had to bring

HR in early, and not just one person, but HR leadership,” Long said. “We really lean on HR to say, How are we growing that leadership capability?”

The second work stream is structure. There are structural elements or principles that lead to teams learning more quickly, she said—things like being fully dedicated, having direct access to decision makers, and having a team of coaches that helps enable the innovators and gets things out of the way. “Where we have these structural elements in place, those teams are learning the fastest.”

The third element is the talent ecosystem. A particularly important aspect of that is how to recognize and reward innovative work. It turned out, Long said, that P&G innovators needed to feel that their work was valued and rewarded like those at the core of our business, so it was important to learn factors, both intrinsic and extrinsic, that would make the innovators feel valued and rewarded. P&G has also been working to determine how to take into account the team versus the individual. “Up to this point,” she said, “we had only rewarded based on individual contributions, and so we’re trying to learn how we bring the team factor into it.”

Another aspect of the talent ecosystem is skill and capability development, Long said. P&G has made a big push to grow skills and capabilities across the organization and not just in certain pockets. “We’ve learned that measures in the innovation space are different than measures in the core business space,” she added, “and so we’re learning what innovation metrics are.”

A key change has been to not assume that those at headquarters know or can figure out solutions and instruct the rest of the organization on what to do. Instead, she said, the approach now is to use lean innovation and run small, fast, disciplined experiments in the business units in order to get clear on the problem to solve. “We measure them, and we make a decision,” she said. “Did this work, did this not work, and what do we need to do next?”

The Skunk Works

Carty began with a brief history of the Skunk Works. During World War II, U.S. propeller-driven fighters were being dominated by the German ME-262, the world’s first jet fighter, and Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson got a contract from the U.S. Army Air Corps to produce a jet fighter that could compete. But Johnson faced a problem of where to carry out his project. At the time, Carty said, Lockheed was building 28 aircraft a day. To put that in context, Lockheed Martin’s current C-130 line builds 28 aircraft a year, and its F-35 line maxes out at 20-some aircraft a month. The Boeing 737 line, which Carty characterized as the most productive production line in the world, produces two aircraft a day. Lockheed was doing 14 times as many, and it had 93,000 people employed. There was no place to put Johnson’s project.

“There was no room in the factory,” Carty said, “so what did Kelly do? He pulled together all the crates that the engines were showing up at the plant in, and that made . . . pillars on which he hung a circus tent.” Skunk Works was the name of the Lockheed division originally created to develop and build the first U.S. jet fighter, and it was born in that circus tent.

“I know that’s a lot of background,” Carty said, “but it frames where this thing came from. It came from boiling things down to the essence of what you needed to get done, always focusing on the essence of the goal.” From the beginning, he said, the Skunk Works has been focused on finding the simplest path to an effective solution, and that is still true today. He described the organization as one that is focused on common goals under the direction of an empowered leader who has the necessary resources and a minimum of administrative burden and who can adapt processes as needed to get the job done.

Today, Carty said, “the real challenge is finding out how to keep things simple in a complicated world and figuring out what are the bounds of taking a model that’s rooted in simplicity and functionality and pragmatism and scaling it up.” The original Skunk Works team was Kelly Johnson and 34 of the best engineers he could pull from Lockheed’s 93,000 workers. Today’s Skunk Works employs thousands of people, Carty said, and now instead of a single product—the first jet fighter—there is a portfolio of products for multiple customers. So it is challenging to maintain the same sort of simplicity that characterized the Skunk Works in the beginning.

Concerning its workers, Carty said that while the Skunk Works certainly values talent, it values perspective and worldview and passion more. Many of the people working there have always dreamed of working there or

working on the sorts of problems that the Skunk Works does. “We tend to gravitate toward bringing folks in that may not have the skills they need because we believe that, as a team, we can teach them those skills,” he said.

The Skunk Works tries to keep communication paths minimal, Carty said. For example, if there is a large project that needs to be done in a short amount of time, the project’s designers and engineers will likely be located together on the production floor. So a mechanic or production engineer can walk over to the desk of the engineer who designed something and say, “Let me show you why this isn’t working” or “Let me show you how this could have been done better” or “Could you change this for us?” That instant feedback is very important, Carty said.

Ownership and accountability are also very important, he said. For example, the designers and engineers on a project will generally follow it all the way through to the end “because the best way to learn is to have to live with your mistakes and then fix them,” he said. “Once you’ve made that mistake and had to fix it, you probably won’t repeat it.”

Finally, he said, those who work at the Skunk Works recognize it as a national institution and a resource to the nation, and they tend to feel an obligation to maintain that status. “So it’s always at the front of our minds that we’re trying to focus on performance and meeting our commitments and doing it quickly and quietly and with quality,” he said. “That’s the mantra.”

U.S. Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center

Working for the military comes with various constraints, Turnbull said. “Our promotions, for example, are done by a central board that reviews your performance records—[people] that have never met you,” he said. “When you have a system like that, you end up with a number of both written and unwritten rules. You’ve got to do A and B and C because the people that are promoting you did A and B and C. . . . So that’s the overall framework.”

So, he asked, how does one succeed as an innovator in that kind of environment? Referring to Fraser’s model, which found stretch assignments to account for 70 percent of advancement and sponsorship to account for 20 percent, he said he believes that the numbers are wrong and that sponsorship is actually a much bigger percentage. The reason, he said, is that sponsorship is what leads to the opportunities to have stretch assignments. Given the opportunity, one must perform, of course, but one must first get the opportunity, and much of that depends on sponsorship. In his case, he said, he was lucky to work for great leaders who wanted to innovate and to get results, even if it required doing something different from what the system expected. They gave him an opportunity, and once he succeeded, they would put him on another project, and so on. “From my perspective,” he said, “that’s the only way to do it within the kind of system that we have.”

It has proved very difficult to change that system, Turnbull said. “We’ve had multiple chiefs of staff—the person in charge of the Air Force—who have tried to change things and failed because the system just has so much inertia,” he said, so he is not going to be able to change the system. But what he can do is figure out how to open doors for other people and give them opportunities.

A worker has to understand what the rules of success are in that system, he said, and so he makes it a point to have a conversation about those rules very early in the career of those people doing innovative work. He tells them, “Look, this is the system. These are the rules. I don’t like them. I didn’t write them, but these are the rules. You’re going to need to do A, B, and C. Let’s figure out how to get you to do A, B, and C, while still giving you the opportunity to do the innovative things you’re trying to do.” So he works to open doors for these innovators while enabling them to check all the necessary boxes.

He has not always been successful, he said, and he spoke in particular of two “crushing blows” he has had. One was a female lieutenant colonel who had been in the Air Force for 20 years and was leading Turnbull’s most sophisticated project. She delivered results several years ahead of plan, was a phenomenal leader, and had been selected for a prestigious fellowship, Turnbull said, but despite everything he could do, she did not get promoted to colonel. She immediately filed her retirement paperwork and left. “That is a complete loss to the system,” he said. “There’s no way for us to get her back. And so it doesn’t always work, because we don’t control that central system.”

Turnbull also described a younger officer, a major, who had won accolades and awards as one of the Air Force’s top program managers because he was delivering really innovative results. But he had not checked off all of the

boxes, and so he did not get promoted to lieutenant colonel. Fortunately, Turnbull said, in this case the officer will have a second chance next year to get promoted, and he hopes the outcome will be different next time. “I think we have stacked the deck in his favor,” Turnbull said, “but we had to proactively reach into the system, pull him out of where he is, and then put him somewhere where he’ll check one of those boxes.”

Turnbull summed up the responsibility of managers of innovators in this way: “If we want innovative people to succeed, . . . we have to be personally and directly involved in trying to reach in and protect those people where we can put them into the right opportunities, open the right doors. And we have to make sure that leaders at all levels of the organization are doing that.”

In response, Fraser told Turnbull that that was “the best description of sponsorship I have ever heard, and I’ve been thinking about this and talking about it for 4 years now.”

QUESTION-AND-ANSWER SESSION

After lunch, there was a question-and-answer session with the three panelists. The first question, from Dan Ward of MITRE, referred back to the third pillar that Fraser spoke about, “Do the easy thing that’s good enough.” In discussing that, she had said that this will often mean implementing short-term fixes that are neither sustainable nor scalable and that this is just fine. At this point, she said, rigor and scalability are red herrings. “That resonated with me so much,” Ward said. “We do fall for the importance of rigor and scalability in places where it isn’t necessarily needed.” So he asked the panel members for their responses to this idea.

Long answered that she has taken that lesson to heart at P&G but that it can require a change in perspective. In running experiments, she finds that people expect that whatever is being tried will be scaled up eventually. “So we’ve had to change the narrative around,” she said, and to make the focus more on the present. Then the major issue becomes what is needed to answer the question in front of you, which for her experiments generally requires just 5 or 10 people instead of 100 or 1,000.

“Two things popped into mind,” Carty said. “One is that we try to be vigilant about watching out for reviews and audits that don’t actually aid in making decisions.” He is not always successful in avoiding those things, he said, but he is conscious of trying to. Furthermore, he added, more and more of those unnecessary reviews and audits are driven by process, and “the process is a substitute for the simplicity that we talked about.” In a situation where there was a truly integrated team that could communicate with each other directly, then the need of process would be less. “So process is something that you feel like you have to bring in as things scale and get bigger and bigger,” he said. “They add complexity, they add abstraction, they add ambiguity, and that’s the challenge as those things creep in—Can you identify what’s actually adding value and what isn’t?”

Turnbull answered that when he heard the comment about short-term fixes that are neither sustainable nor scalable, he immediately thought of computer hacks. “Everybody loves a good hack,” he said, “but if you add enough of those over time, they are certainly not sustainable.” However, he added, if things are changing fast enough, the hacks quickly become irrelevant, and you just find new hacks. If you had taken the time to scale the process, then it would have been overtaken by events by the time you were finished. “It doesn’t matter,” he said. “So just stack the hacks.”

On that topic, Turnbull said that he has found it can be useful to encourage people to hack the system and then to look around and see which things have been hacked by multiple people. “When you find four different product centers hacking the same thing,” he said, “that’s your clue that there’s something we’ve got to put some attention on fixing.” The one-off hacks, by contrast, can be ignored because there probably is not a great enough return on investment to fix those things.

A question about what things people had tried that had not worked generated several responses. Long began by describing an experiment at P&G whose current version is working but whose earlier versions had “failed.” The experiment involved something Long had mentioned earlier—how the entrepreneurs at P&G needed to feel like their work was valued as highly as the work of the people in the core of the business. “One of our early ideas was to come up with something called an entrepreneur track at P&G where you could build your career as an entrepreneur,” she said. However, when the idea was presented to a group of employees, it was rejected immediately. “But we did that in such small, fast experiments that it didn’t feel like a failure,” she said. This happened with a

number of versions of the entrepreneurial track, but it never seemed like they had failed. “We were learning with 5 or 10 or 15 people as opposed to developing something and then rolling it out to the whole organization,” and with each iteration they learned something to apply to the next version. The current version is getting much better reviews, she said, “but the earlier versions of it were terrible.”

Carty had a response that was similar to Long’s. “We work on things all the time that aren’t successful,” he said, “but one part of our culture is we try to drive to demonstration as quickly as we can and learn from it and adapt and try it again.” Even for systems where crashes are not an option, it is still possible to simulate them and learn what the failure modes are. “So those things that didn’t work, I would say they did work because you’re learning and you’re changing your solution, and then you’re trying it again.”

It is possible to learn a lot about the culture of an organization or a research team from its response to failure, Carty said. Is the first thought of retrenchment or cover one’s bases or fear or concern? Or is it to “run faster, get back in the lab, get back on the horse”? Ideally, he said, an organization will have a learning culture that is not inhibited by a fear of failure. The only true failure is “a failure without learning, a failure without some kind of diagnosis or a path forward.”

Turnbull described an episode in which he had attempted to change a security-related process that was inhibiting his ability to deliver warfighter capability. When he came up with a new process that would remove the impediments, he was told that a particular Air Force instruction (AFI) prevented him from doing that. The AFIs are “the rules we live by,” Turnbull explained. “So I went and found the person in the Pentagon who wrote that AFI, and I got them to change it,” he said. “And I came back to the person and said, ‘Look, I changed the rule. You can do this now.’”

But even after he had gotten the rule changed, he said, there was still much resistance to the new process. What was going on? “I figured out that it came down to fears: This is going to make me irrelevant. This is going to make my job disappear. And this affected a large number of people in the organization.” So to this point, he said, he has not yet succeeded in changing that process, although he is still working on it. He needs, he said, to find a way to make those chickens happy.

“Happy chickens don’t make trouble,” Fraser commented. What are they afraid of, and what will it take to make them feel safe? Knowing that their job is safe? Knowing that they have more interesting work rather than more bureaucratic work? “We have to think about our chickens with compassion,” she said. “It’s easy to beat on them and think, ‘You’re an impediment.’ No, they’re humans.”

At the end of the question-and-answer period, Fraser asked Dan Ward to explain his theory, “The Simplicity Cycle,” which he said is intended to help people think about complexity and its effects in designed objects. He described the cycle in terms of a graph where the horizontal axis is “complexity” and the vertical axis is “goodness.” Complexity, he said, means “consisting of interconnected parts.” Greater complexity means a greater number of interconnecting parts. Goodness refers to different things in different contexts, he said. “It could mean fitness for use. It could mean maturity of the design. It could mean effectiveness, efficiency, whatever your measures of merit are.” Thinking about The Simplicity Cycle, he said, is intended to force people to answer the question, What do we mean by goodness? What constitutes better?

A design starts with a blank piece of paper. In that case, both the complexity and the goodness are zero. “So we begin adding things to our design,” he said. “As we add pieces, parts, and functions, complexity rises and goodness rises. I add a bubble canopy to my airplane. Now I can fly higher. It’s a new part, a new capability. Complexity and goodness are directly proportional.”

At some point, however, the design reaches a critical point beyond which adding pieces, parts, and functions does not add to the goodness—indeed, will often detract from the goodness—while still adding to the complexity. On the graph, this looks like a downward bend in a line that had up until this point been going up. “This is not diminishing returns,” Ward said. “This is negative returns.”

At this point, he said, the way to continue to increase goodness is to “adopt a different set of design behaviors and begin simplifying—begin subtracting, trimming, streamlining, using reductive thinking models instead of additive thinking models.” It is important, Ward said, to understand that there is this bend in the curve—that it is not possible to keep increasing complexity indefinitely without eventually affecting goodness—and to keep an eye out for that point at which increasing complexity creates negative returns.

IDEATION SESSION

The rest of the group’s time was spent on what Fraser referred to as an “ideation session.” She divided the group into teams, each of which included one of the section’s invited experts. She then provided five problem areas and challenged everyone to come up with at least 10 ideas that had been inspired by what they had heard during the section. The ideas were to be written on sticky notes so that they were easy to organize by sticking them to boards.

Once everyone had finished their sticky notes, Fraser said, they would be organized by putting them on whiteboards corresponding to the five problem areas. On those boards, the ideas would then be categorized according to how difficult they would be to achieve (easy, less easy, hard, impossible) and by how pressing they were (less urgent, more urgent). Fraser called the approach dump and sort: “You dump out all your ideas, you sort them, you figure out which ones matter and that you can take action on more easily. . . . And by the end of the day, we should have a work plan that can be summarized in a one-pager.”

The five problem areas were as follows:

- Human systems—the hiring, developing, managing, etc., of workers;

- Gen Z magnet—how to attract, inspire, and retain the generation coming out of school and into the workforce now;

- Safe to try—creating a workplace in which people are not afraid to fail;

- Stop the stupid—getting rid of policies and practices that are obviously not effective or are even actively damaging; and

- Ambidextrous leaders—developing a new model of leadership that rests on a culture of “and” rather than “or,” that values discovering over knowing, and that has leaders who ask questions and remove roadblocks. It has been described as the best style of leadership for innovation.

The resulting whiteboards with ideas on sticky notes were organized by difficulty and urgency. In a plenary session later that afternoon, Fraser and section co-leader, Bob Gibbs of NASA, highlighted the top suggestions from each of the five problem areas, focusing more on the suggestions that had been classified as more urgent.

Under human systems, a more urgent task that had been classified as easy was “Incentivize leaders to sponsor innovative people.” It was noted that incentives both provide a signal of what is important in an organization and lead to more of the incentivized behavior. Another more urgent but easy task suggested was “Create short-term stretch jobs to identify innovative leaders early in their careers.” This was a product of the extensive discussion in the section about how stretch jobs can provide tests of people’s capabilities. A more urgent task that was classified as less easy was “Disrupt the one-size-fits-all approach to rewards and benefits.” Different people are motivated by different things; the reward system should recognize that. Other more urgent suggestions that were rated as less easy or hard included “Experiment with reward systems (intrinsic and extrinsic),” “Experiment with career systems,” and “Redefine success measures.”

The next subject area was Gen Z magnet, or how to become a magnet for the next generation. A suggestion for an urgent but easy task was “Do more cheerleading and spotlighting,” while an urgent but less easy task was “Define what is best and brightest (it’s not just talent).” Gibbs noted that the sorts of talent required will differ for every mission. Other urgent, less easy tasks were “Recruit early and often,” “Know what is valued,” and “Try new things willingly.” An urgent but hard task was “Offer early ownership.”

In the category of safe to try, or how to make it safe for innovators to try things, an easy but urgent task was “Create small, fast projects that can accept failure in order to develop the workforce more quickly.” The idea, Fraser noted, is to choose some resilient projects where failure isn’t too impactful so that early-career workers can stretch their wings. Another urgent, easy task was “Visibly reward and recognize failures and learning.” This sends the signal that “failures” are not regarded as negative as long as they involve learning and help the project move toward to the overall objective. An urgent task that was classified as less easy was “Adopt ‘Do more experiments’ as a valued practice.”

The next category was stop the stupid. “This is about creating simplicity,” Fraser said, mentioning Ward’s description of his Simplicity Cycle model. The easiest task that was categorized as urgent was “Create an award

for stopping stupid.” It is a way of drawing attention to the need to identify and modify ineffective practices. A second easy but urgent suggestion was “Find the person who made the rule and ask if it can be changed.” This was, of course, referring to Turnbull’s story about his attempts to get a process changed that was hindering innovation. Unfortunately, as Gibbs noted, in Turnbull’s case, even going to the person who made the rule and getting the rule changed was not enough because of resistance to change inside the organization.

The final category was ambidextrous leadership. In this case, there were a number of suggested tasks that were characterized as urgent but also easy. Some of them were aimed at spreading the word about ambidextrous leadership and its importance: “Educate people about ambidextrous leadership” and “Seek, support, and celebrate ambidextrous leaders.” Others were intended to develop more ambidextrous leadership: “Leadership training/coaching,” “Ask questions without knowing the answers,” and “Encourage rotation.”

That last suggestion prompted a discussion between Fraser and Gibbs. Fraser began by asking whether NASA has leadership rotation. “No,” Gibbs said, “but I would tell you that we’re sharing a lot more talent from center to other centers and to headquarters in D.C. That’s definitely been a trend in the last 3 to 5 years.” Fraser commented that she had heard some discussion about having career NASA people—those who had been with the agency for 10, 20, or more years—have rotations outside the organization. “Yes,” Gibbs said, “that’s something that I’ve heard in a lot of different sessions and a lot of different times.” He added that it was something that he would love to work on and that, indeed, NASA has been working on it. “We have a legislative proposal in right now to allow us to do more of that,” he said. “We’re not getting as much traction as I would hope within the administration, but it’s something we’re continuing to push.” Fraser replied, “I would say that falls into the very hard and potentially impossible if you don’t get support for it.”

In responding to that, Gibbs commented more generally on the urgent tasks that seem hard, if not impossible. “In doing this kind of work,” he said, “you have to know which of the super important, but very, very hard things are worth breaking your back on.” Fraser suggested one way to do that is to break down the task into smaller things and attack them one at a time. So, for example, if an outside rotation is not legally possible, maybe there would be some other way to get that “outside” perspective in the thinking of NASA’s leaders. If NASA people could not work at an outside organization for a year or two, perhaps they could do it for shorter periods of time. “There might be a better return on investment for a longer detail,” Gibbs said, “but at least that’s a great stepping stone.”

PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT

The breakout section on portfolio management examined the general question of what it takes to have a healthy portfolio of investment in innovative technologies. The three speakers in the section were Barbara Dalton, who manages Pfizer’s private equity portfolio, Pfizer Ventures; David Longren, retired vice president of Polaris Industries; and Mark McClusky, the founder and president of the consulting firm Newry Corp. After hearing the speakers’ presentations, the section’s members participated in a brainstorming period to develop ideas for improving NASA’s management of its innovation portfolio.

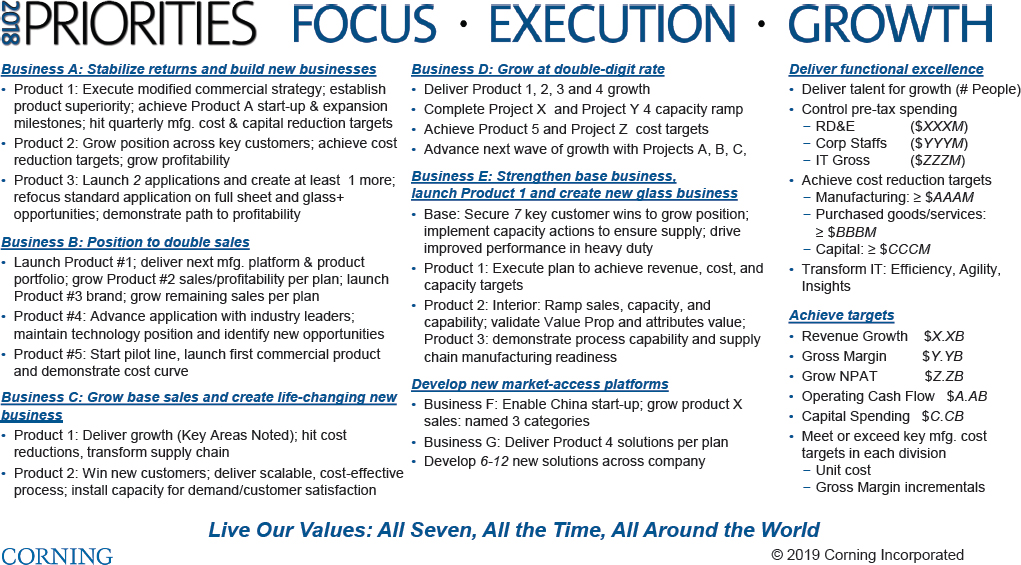

As a lead-in to the presentations, section co-leader Martin Curran of Corning described how that company develops and uses its “one-pager” (Figure 5.3), a brief overview of the company’s current situation and its objectives, which is used to focus the organization and get everyone in the company on the same page. The one-pager originated in 2003, after Corning had experienced what Curran called “a near-death experience.” In the beginning, he said, the company was just trying to survive. “We lost half of our company, half of our sales in the dot-com bubble.” So the company’s management developed the one-pager as a way of getting “all hands on deck.” The first version was focused on financial metrics, as the company was focused on maintaining cash and access to credit lines and restoring profitability. After the company did return to profitability, it maintained the practice of producing the one-pager, which summarized the company’s key objectives as a way of maintaining focus across the company on top objectives and activities that were key for its success. Financial and performance metrics are still a key component, he said, and there is always a reminder to live the company’s values.

Curran showed an example of what Corning’s one-pagers look like and said that it was the only time in 15 years that it had been shown outside the company. It is a dense one page of text, with objectives listed for each of the company’s businesses and, beneath the objective for each business, goals for specific products. The business

objectives are things like “Stabilize returns and build new businesses” and “Grow at double-digit rate,” while the product goals include things like “Deliver growth,” “Win new customers,” and “Demonstrate process capability and supply chain manufacturing readiness.” To one side is a collection of specific financial targets, including for cost reductions, revenue growth, and capital spending.

Having listed the objectives and goals, the company then monitors progress throughout the year and will color the individual items on the one-pager green, yellow, or red to indicate success, still working on it, or failure. “I can tell you without a doubt,” he said, “that in 15 years we’ve never had all the first two columns [with the business objectives and product goals] green. We’ve had many times that the right-hand column [with the specific financial targets] is green.” It is a way of judging at a glance how the company’s overall performance has been and what things in particular need attention. The one-pager is focused specifically on annual goals, Curran said, that also tie strategically to Corning’s 5-year plan, which is refreshed yearly.

The Innovation Portfolio at Pfizer

Pfizer is one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, Dalton said, with more than $53 billion in sales in 2017. The company has approximately 500 drugs on the market and another approximately 400 in the pipeline, so its portfolio includes about 900 products.

Characterizing Pfizer and NASA somewhat facetiously as “twins separated at birth,” Dalton listed a number of parallels between the two organizations beginning with the fact that they both rely on innovation—Moon shots and space exploration for one, drug development for the other. Both are in the knowledge discovery business, and both have long development cycles. Just as it can take a couple of decades to put people on the surface of Mars, it can take a couple of decades to discover, develop, and market a new drug.

In both organizations, she continued, innovation is necessary not only in technology, but in workforce practices, partnering, and business practices. Both are dependent on the federal government, albeit in different ways—NASA

for its funding, Pfizer for various laws and regulations that shape its business. A great deal of innovation that affects each organization takes place outside its walls, so each organization has to be aware of that and determine how to work with it. Both face competition from smaller, more nimble organizations, and both are operating in an environment in which there is a new age of collaboration between competitors. Both NASA and Pfizer manage a large number of projects, Dalton continued, and both provide societal benefits that are not easy to quantify. Finally, she said, both face a situation in which failure is not an option because failure can lead to people dying.

Continuing the theme of parallels, Dalton showed a slide, “Barriers to Innovation at NASA,” where she had crossed out “NASA” and written “Pfizer.” It got a laugh, but her point was serious: “Every single one of those are questions that we grapple with and have to deal with on a daily basis,” she said. “It was amazing to me to read this list.” The items on the list were a risk-averse culture, short-term focus, instability, lack of opportunity, process overload, communication challenges, and organizational inertia. Someone in the audience explained that the list of barriers to innovation was put together by a group of younger scientists and engineers at NASA, sponsored by the chief technologist’s office.

Next, Dalton spoke about Pfizer’s portfolio of products and projects. She broke it down into four categories: in the laboratory (~200 products), being tested in human studies (~200), at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) waiting for approval (~50), and on the market (~500). Each category has its own characteristic rate of failure, she said. About 50 percent of the laboratory projects fail, about 90 percent of the drugs being tested in human studies fail, about 5 percent of the drugs submitted to the FDA for approval fail, and about 20 percent of the drugs that make it to market are commercial failures. The failure rate in human studies is high, she said, because there is no way to know just how a drug will work in humans until the effects are observed; even drugs that prove to be effective in animal models have no guarantee that they will be effective in humans. “We’re operating in the dark,” she said. “So we have a phenomenal failure rate. We fail every day. If we don’t fail, we’re probably not doing our job.”

Making portfolio investment decisions is inevitably a subjective task depending on human judgment, she said, because there are so many unknowns involved. Still, companies try to base those subjective decisions on objective information and analysis to the greatest degree possible. “Successful decision making requires reliable, unbiased inputs as well as a qualitative lens so that any one factor does not dominate,” she said. The decisions are made by people who look at all of the information and apply their experience and expertise, taking a holistic approach that takes into account such things as cost–benefit analyses and consideration of regulatory factors, strategic considerations, platform capabilities, and potential patient benefits. Ongoing projects should be reevaluated regularly, she said.

“Portfolio management is all about where you’re spending your money,” Dalton said, “and you’re spending your money in a place where you think you can make money.” Decision on a portfolio management strategy requires commercial decisions and research decisions and regulatory decisions, and they’re made on the basis of totally different factors, she said. Thus, for example, those on the research end are likely to see the issue in very different terms from those on the commercial end. All of those factors must be balanced.

There are various software tools to help in making portfolio decisions, Dalton noted. She mentioned Monte Carlo simulations used to predict how various portfolios are likely to perform—there are various analytic methods; iPort, which uses an internal enterprise database to track individual projects and aggregate portfolio data; and the Enterprise Portfolio Simulator, which is now in testing.

Dalton’s job at Pfizer, she said, is to manage the company’s venture capital investment portfolio, which she referred to as “a portfolio of disconnected science projects.” The company makes venture capital investments in various ventures in areas that Pfizer is already involved in or that it may become involved in. Decisions about which companies to invest in are generally not highly analytical, Dalton said. Instead they most often rely on “soft analytics”—experience, knowledge basis, and gut feelings. The decisions are made by a small group of people, and success is determined simply by return on investment.

In making investment decisions, Dalton said, she looks for what she called “star clusters.” These are collections of several companies all doing work in a new area. The idea is that if there are several different companies that all believe this new area is worth developing, then there is a good chance something will come out of it. In such cases, Dalton said, the idea is to invest in one of the “stars” in the cluster. At that early point, it is impos-

sible to tell which is likely to be most successful; the idea is to have some presence in that area in case something important develops.

Pfizer’s venture capital investment portfolio has a 10 to 15 percent investment in about 30 companies, Dalton said. And when Pfizer has an interest in a company, it helps increase that company’s chances of success in various ways, she said. It helps the company identify a good management company, for example, and offers various sorts of advice.

This is a strategy that NASA could adopt, Dalton suggested—developing relationships with small, cutting-edge companies and providing help and support to increase their chances of success. Spreading the knowledge and expertise that has been developed at NASA is part of the agency’s mission, she suggested.

One of the benefits of Pfizer’s venture capital portfolio, Dalton said, is that it allows the company to tap into innovation outside the company—which is an important thing for any innovative organization to do. There are various ways to do this, she noted. It is important, for example, to develop external collaborations, even with competitors. In that case, she said, “Trust, but verify” is good advice to live by. An organization should also generate tools to tap into external innovations, she said; you will need several. It is best if these actions are driven by the organization’s workforce, which raises the question of how to get the workforce to see the value of external collaboration. As time goes on, Dalton predicted, organizations like Pfizer and NASA will increasingly find that they need or can benefit from external innovations, and she suggested that organizations could benefit from the generational change that is taking place. Millennials bring different perspectives and experiences to the table, and the diversity they offer can be valuable.

Finally, Dalton spoke of the role of failure in innovation portfolio management. “Failure comes with the business,” she said. Science moves forward through both success and failure, and people learn more from failures than from successes, so it is important to encourage a culture that embraces failure and uses it as a tool, she said. “Fail early, incrementally, knowledgably, repeatedly,” she said, “so the overall mission can be successful.”

Innovative Success at Polaris

Next, Longren described how Polaris recreated itself to become a highly innovative company whose success was driven by a steady stream of new innovations. He noted that his remarks also drew upon his experience as a board member of Rexnord—a leading manufacturer of aerospace, power transmission, and water products—where he led an effort to transform their innovation practices.

Polaris, which manufactures off-road and military vehicles, was started in 1954. In the early 2000s, Longren said, the company’s chief executive officer initiated a series of changes designed to transform the company to a high-growth business. Longren was hired as the chief technology officer to help lead that initiative. “It took us about 3.5 to 4 years of foundational work to transform ourselves,” he said, and the company’s sales began to take off in 2008 to 2009.

Over the next 7 years, Polaris experienced “very high growth,” Longren said, and its total sales tripled. Perhaps the most striking part of the transformation was how the company’s sales came to rely on new products, by which Longren meant products that had been introduced in the previous 3 years. Longren defined the vitality index to be the percentage of total sales that is accounted for by new products, and he said that it is a key measure of how important innovation is to a company’s sales. In particular, there is typically a larger margin on the sale of new products, so it is a rough indication of profitability or, at least, of potential profitability. Polaris’s vitality index averaged 80 percent for multiple consecutive years, Longren said, a number that several people in the audience indicated was quite impressive.

Longren described the elements that combined to allow Polaris to achieve that level of innovation. It starts with a strong leadership focus, he said. The leadership must have a clear vision of where they want to go and allocate resources accordingly. It is vital that the people have a passion for high performance and innovation and that the company’s processes support that.

The leaders should strive to build a culture of collaborative innovation that is focused on the customer. “We have competitions among new products coming down our pipeline,” Longren said. “We can have two or three

products competing to be what’s ultimately going to come out. But it’s all what’s best for the marketplace, whether it’s for our consumer or for our military customers out there.”

The company must invest in innovation, developing an effective infrastructure, tools, processes, and program management. It is important to enable flexibility and agility while maintaining world-class quality, Longren said.

The company must plan for innovation, and Polaris does that mainly through its portfolio management, he said.

Finally, he said, there must be a continued focus of people and processes on innovation. Speed is important, he said, but it is not as important as direction.

To talk about what goes into successful innovation, Longren pointed to three very different examples: the development of the P-51 Mustang, the successful return of Apollo 13, and the U.S. hockey team winning the gold medal at the 1980 Olympics. The three examples point to key “rules” for successful innovation, Longren said:

- Have a clear objective and focus; in each example, there was a real-world problem that forced the people working on it to set solution boundaries.

- Set high expectations—the organization can deliver more than you think.

- Teamwork is more important than individuals; create and reward a strong team culture.

- Speed is as important as precision.

- Use real-time feedback control systems.

Polaris used these guidelines in transforming the company, Longren said.

Next, he spoke about the company’s portfolio management activities. Any company must decide how it will allocate its investments—in high-growth areas, in quality improvements, in new markets, etc. The company decides ahead of time what percentage of its expenditures will be on R&D, and it keeps to that figure or sometimes increases it. The company’s leadership spends a lot of time debating what percentage of the portfolio it is going to invest in each area, he said. Each year the company sets resource allocation and set various goals, and the senior leadership reviews these quarterly. There are also monthly status reviews and product planning and weekly program team meetings. For each product type, the leadership talks about how big the market opportunity is and how risky it seems. They look at both the short term and the long term.

The company has an innovation planning framework that includes both top-down and bottom-up approaches, Longren said. Looking at macro market conditions and doing economic analyses, including looking at new growth-market opportunities and disruptive products, they set top-down goals. And working with their key innovators and scientists, they look at what new tools and technologies they have coming and decide on bottom-up expectations. They merge the two together and go through an evaluation process to decide where to make investment and what their goals should be. The result is a 5-year technology development roadmap, which gets reviewed every 6 months by the company’s senior leaders.

The Polaris culture is designed to encourage innovation. “Our culture is about boundary management,” Longren said. “It’s not about point solutions. So we create space for innovators to innovate within them.” Similarly, projects are guided with priority-ranked boundary requirements.

Work is done in small, integrated project teams of 10 to 12 people, and these teams leverage subject-matter experts in the company as needed. People are constantly rotating in the company, Longren said, and there are also experts who “parachute” into the company to serve as needed for a period of time. Generally speaking, no one at the company stays working in one small area for years at a time. They go where their expertise is needed at the time. “Our workforce is highly flexible,” he said.

The company also has various design challenges to take advantage of crowdsourcing. A problem will be set forth, and people from inside the company or from the company’s suppliers can offer solutions. The challenge will generally run for no longer than a month. People submit their ideas, and winners are announced. “No one cares about the prizes,” Longren said. “It’s about the fun.” And if an idea looks particularly marketable, the company has a reserve of funds that can be used to develop the idea.

Polaris leverages its suppliers to increase its ability to innovate, Longren said. Its key suppliers are treated as strategic partners, and frequently visit and work with the company’s R&D centers (although there are multiple

firewalls that protect certain sensitive information). These partners are encouraged to bring ideas to Polaris about new technologies and solutions that they have created or adapted from other applications.

A key feature of Polaris’s success is how it captures and uses knowledge gained from its business operations. “We have a very formal knowledge management system in place,” Longren said. “It’s all about capturing learnings, capturing discovery.” Technical people do not always like to share the knowledge that they’ve gained in their own work, he said, and that’s understandable. “But that’s not what we want,” he said. “We want you to share it so the next time we don’t have to do it again.” Furthermore, he said, the company wants to capture the assumptions that people are working under, because in the future there may be new technologies that mean those assumptions are no longer valid and the problem can be solved in a new way. The company’s key technical people enter their key learnings into the knowledge database, Longren said. Workers are rewarded for capturing significant knowledge and discoveries.

Finally, he said, the company focuses on continuously improving all its processes. It maps out all of the steps of the processes, sees how long each of the steps takes, and assigns value to each of the steps. Then it looks for changes that can be made to improve quality, add value, and eliminate wasted time and effort. This frees up innovators’ time and reduces their frustration, leading to improved focus and, ultimately, better innovation. The company uses proven technologies and platforms, where possible, in order to free up the design team’s time, allowing them to spend more time on breakthrough technologies.