5

Healthy and Safe Health Care Organizations

As described in Chapter 2, the committee’s conceptual model shows that system factors that contribute to burnout and professional well-being are influenced by multiple system levels. These system factors need to be addressed to decrease, prevent, and mitigate burnout. This chapter addresses the linkages between two levels of the health care system, frontline care delivery and the health care organizations (HCOs) (Berwick, 2002). It focuses on the actions and decisions HCOs make that affect the clinical work system and the care team. Research about complex systems shows that resources, constraints, incentives, and demands produced by organizational leadership shape the work and the behavior of people in the organization (Cook et al., 1998; Reason, 1997). Thus, it is important to understand the interactions between the care team and HCO leadership.

___________________

1 Excerpted from the National Academy of Medicine’s Expressions of Clinician Well-Being: An Art Exhibition. To see the complete work by Julie Shinn, visit https://nam.edu/expressclinicianwellbeing/#/artwork/197 (accessed January 30, 2019).

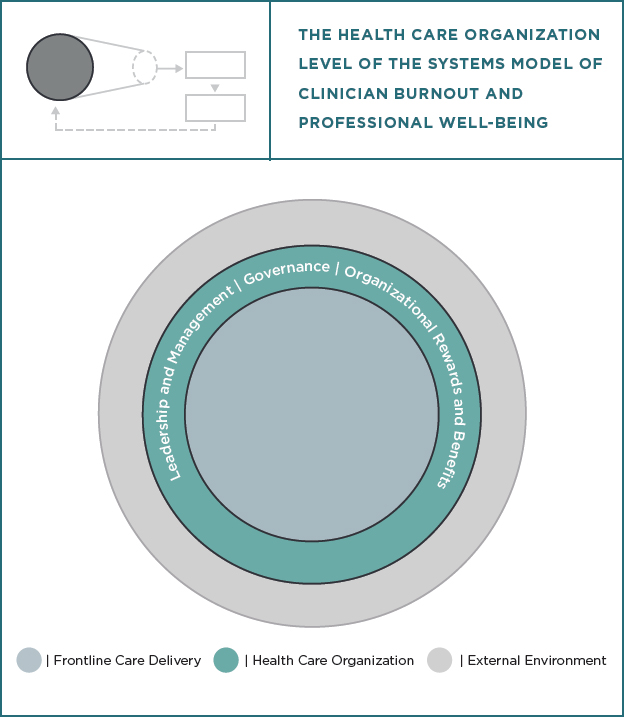

Figure 5-1 highlights the HCO system level in the context of the committee’s systems model for clinician burnout and professional well-being. (See Figure 2-1 for the full systems model.)

As discussed in Chapter 4, the committee found that the factors contributing to burnout are numerous, varied, and are context-dependent, which underscores the need for HCOs to adopt multi-pronged strategies to shift their current structure and practices. The committee is aware that, to combat the factors driving burnout, many HCO leaders are seeking actionable solutions that have proven effectiveness against burnout and detailed specifications rendering them ready for implementation. Unfortunately, the committee found few interventions that meet these expectations. The first part of this chapter presents the committee’s findings about the limited evidence for organization-focused interventions that address burnout

and professional well-being. Nonetheless, there are many opportunities for HCOs to bring about positive change that can reduce burnout and improve professional well-being. The second part of the chapter focuses on guidelines for creating systems that promote professional well-being. These guidelines reflect the characteristics of work systems that produce professional well-being (based on work design theories and models), as well as approaches for improving work systems and worker well-being (e.g., based on human-centered design). The committee developed these guidelines for well-being systems to support HCOs’ efforts to design, implement, and sustain positive work environments and thereby continually improve both professional well-being and patient care.

EVIDENCE ON HEALTH CARE ORGANIZATION INTERVENTIONS

This section discusses the limited literature on the effectiveness of HCO-based interventions designed to address clinician burnout. The majority of published studies have focused on individual versus organizational interventions, with variable results. Of the few systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted to date (discussed below), the evidence suggests that organization-focused interventions are more effective at reducing overall burnout than individual-focused interventions. Gregory and colleagues (2018) reported that “interventions to reduce burnout have sought to improve the resilience of an individual to withstand this [job demand–job resource] imbalance rather than identify and ameliorate the cause” (Gregory et al., p. 339). (See Chapter 4 for a definition of job demands and job resources.) The committee’s charge to examine systems approaches to the problem of burnout is consistent with the evidence. On the basis of the available literature, the committee concludes that while individual-focused interventions can help to reduce burnout, they should be combined with effective organizational or system-level interventions.

Organizational and Individual Interventions

A systematic review and meta-analysis by West and colleagues (2016) examined research published on individual and organizational (or structural) interventions designed to prevent or reduce physician burnout. In the studies reviewed, organizational interventions primarily consisted of changes in duty hour requirements and practice-based delivery changes. Mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussion interventions were the individual-focused approaches that demonstrated the most promise at reducing burnout symptoms. For both individual and organizational interventions, most of the studies reviewed by the authors suggested

reductions in specific dimensions of burnout (i.e., emotional exhaustion or depersonalization), whereas fewer found improvements in overall burnout. Of the studies that measured overall burnout, organizational interventions were more effective than individual-focused ones. However, the authors suggested that “both strategies are probably necessary” (West et al., p. 2278). Another systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions targeting burnout among physicians published 1 year later had similar findings—organizational interventions, such as schedule and staffing changes and reductions in workload intensity, resulted in significant reductions in burnout (Panagioti et al., 2017). While individual-focused interventions also significantly reduced burnout, the effects of the organizational interventions reviewed were significantly greater.

Individual interventions target clinicians’ behaviors and coping strategies, stress and burnout reactions, and resiliency. For instance, there is some evidence that interventions promoting physical exercise can reduce workplace burnout (Bretland and Thorsteinsson, 2015; Weight et al., 2013). Resiliency training, another individual intervention, may also be an effective way to help clinicians manage the unavoidable stress inherent to their jobs (Card, 2018; Epstein and Krasner, 2013).

The evidence is unclear on how best to strengthen an individual’s resilience or how to measure the impact of one individual’s resilience on other team members. These topics warrant further study (Epstein and Krasner, 2013). Despite its popularity, resiliency training does not address the problem of avoidable occupational suffering caused by systemic issues that can be prevented through organizational changes (Card, 2018). Mandatory or required training in this setting, such as mindfulness training, can fuel resentment and disengagement and thus should be avoided. However, having mindfulness and other individual-focused interventions as optional offerings among a menu of choices is a reasonable strategy (Card, 2018; Ripp et al., 2017).

Some individual interventions are embedded into organizational efforts aimed at supporting clinicians. Schwartz Center Rounds are an example of this type of intervention and are in place in more than 400 HCOs in the United States as well as in Australia and New Zealand and in nearly 200 sites in Ireland and the United Kingdom (Schwartz Center, 2019). “The rounds” offer clinicians regular opportunities to discuss the social and emotional stressors they face while caring for patients and families. In a group setting, clinicians share their thoughts and feelings on various topics inspired by real-life cases. A panel presents a case to the interdisciplinary group, which includes physicians, nurses, social workers, and other clinicians, and this is followed by a group discussion about the case and its broader implications. While the committee is not aware of any evidence linking Schwartz Center Rounds with reductions in burnout,

there is some evidence they may foster better communication, teamwork, and provider support (Lown and Manning, 2010) and improve psychological well-being (Maben et al., 2018). Individual interventions such as Schwartz Center Rounds have the potential to be effective if they received adequate HCO support and if clinicians have the resources (e.g., time) to participate in them.

Organization-Focused Strategies

The available literature does not fully elucidate what types of organizational interventions hold the most promise to reduce burnout or its sub-components (e.g., emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, sense of reduced personal accomplishment). One study, however, did attempt to compare organizational interventions that target different work conditions to see which had the greatest effect on clinician stress and symptoms of emotional exhaustion (Linzer et al., 2015). In a cluster-randomized controlled trial in 34 primary care clinics, the interventions were classified into three categories: communications among clinicians and staff, changes in workflow, and quality improvement. While the specific improvement efforts varied, workflow interventions (e.g., reassigning clinic staff work, changing call schedules) and targeted quality improvement projects (e.g., automating prescription phone lines, establishing mechanisms to improve quality metrics for routine screening) were more likely to decrease symptoms of emotional exhaustion (Linzer et al., 2015). These interventions address multiple work system factors that contribute to clinician burnout (see Chapter 4), such as workload, staffing, and professional relationships.

In addition to the interventions assessed in the two systematic reviews discussed above (Panagioti et al., 2017; West et al., 2016), the committee identified studies of organizational interventions that targeted the following work system factors: (1) professional relationships and social support, (2) organization of teamwork, and (3) technology-related factors. These are discussed in the sections below, followed by a discussion of two initiatives designed to foster positive clinical work environments.

Professional Relationships and Social Support

Poor professional relationships and social isolation at work contribute to clinician burnout. Maslach and Leiter (2017) present burnout as a symptom of broken relationships between people and their work and suggest improving workgroup civility as an intervention approach that has shown promise in controlled intervention studies. One example of this type of intervention is CREW (Civility, Respect, and Engagement at Work), developed by the Veterans Health Administration to improve the social

climate of workgroups (Osatuke et al., 2009). Workgroup participants meet weekly or bi-weekly with a trained facilitator to set goals and improve ways in which they work together as a unit. The sessions emphasize respectful interpersonal interactions and building trusting relationships between unit staff and management. In a pre–post comparison, the CREW intervention was found to achieve significantly greater employee civility ratings than the control sites, which showed no improvement. The efficacy of a similar process was demonstrated in a controlled study of Canadian hospitals (Leiter et al., 2011, 2012).

Two studies in 2011 and 2012 (Laschinger et al., 2012; Leiter et al., 2011) examined the impact of CREW on nurses’ empowerment, experiences of coworker and supervisor incivility, and trust in nursing management. Compared with controls, the intervention group reported greater improvements in access to support, resources, total empowerment, trust in management, and supervisor incivility as well as improved job satisfaction and significant reductions in the depersonalization/cynicism dimension of burnout. The changes in emotional exhaustion were not significant. It is notable that while the CREW intervention was not explicitly designed to address burnout, the authors suggest that improving work relationships may, in turn, reduce burnout, and they cite other findings (Bakker et al., 2000; Leiter and Maslach, 1988) that show strong relationships between social support and reduced burnout. Leiter and colleagues subsequently developed a more focused civility intervention, SCORE (Leiter, 2016), that is currently undergoing testing in HCOs in Australia (Leiter, 2018).

A randomized controlled trial of 74 practicing physicians at the Mayo Clinic assessed the impact of an organizational intervention to build professional relationships and social support (West et al., 2014). The intervention consisted of a series of facilitated physician discussion groups that met for an hour about once every other week for 9 months. The 35 participants of the intervention group attended an average of 12 of 19 sessions. Topics discussed during the group sessions included meaning in work, personal and professional balance, and caring for patients. The institution provided the participants with protected, paid time to attend each session. Compared with controls and a non-study cohort, participants in the facilitated small-group intervention reported improvement in meaning, empowerment, engagement in work, and depersonalization (one of three dimensions of burnout). Based on the studies the committee reviewed, initiatives that promote system strategies to foster interprofessional teamwork and civility, reduce disruptive behavior, and build trust among team members can contribute to reducing clinician stress and promote healthier workplaces.

Organization of Teamwork

Reorganizing work to better distribute tasks can be accomplished through various forms of teamwork organization. Organizational strategies that establish well-functioning care teams are likely to target multiple work factors, such as workload, social relationships, job control, and autonomy. Using a pre–post quasi-experimental design, Gregory and colleagues (2018) examined the impact of an organization-level workload intervention at a primary care practice within a large, urban, integrated health care delivery system. The intervention consisted of a distinct work process and model change within the primary care clinics. This involved shifting from a dyad practice structure composed of a clinician (physician, advanced practice nurse, or mental health provider) and a certified medical assistant to a team-based structure of two clinicians and three certified medical assistants who worked together to manage a patient panel. In this team-oriented work model, physicians’ assessments of their workload, the emotional exhaustion dimension of burnout, and depersonalization were lower after 3 months; at 6 months post-intervention, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization improvements were sustained, but the improvement in the workload was not. There could be many reasons for this, which highlight the challenges of sustaining the benefits of interventions. Similarly, a study of clinician and staff perceptions of their work teams showed that positive perceptions of team culture were associated with less emotional exhaustion among clinicians. Clinicians who had positive perceptions of their team culture and also who routinely worked with the same team members, had lower emotional exhaustion scores (Willard-Grace et al., 2014).

Other studies have looked at new models of care based on the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) concept of team-based care. In PCMH, teams work together with the goal of improving clinical continuity, coordination, and patient centeredness. Some studies suggest a potential for team-based care models to reduce stress, anxiety, and burnout among clinicians. For example, Group Health of Puget Sound implemented a medical home prototype that included reductions in panel sizes, expanded staffing model, lengthening of office visits, chronic care management, virtual medicine, visit preparation, patient outreach, and other practice management changes (Reid et al., 2010). In a pre–post study design, implementing the prototype was associated with improvements in patient experience and costs of care delivery as well as with decreases in clinician burnout scores.

In contrast, in a study of the Veterans Health Administration’s team-based model, the Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT), Helfrich and colleagues (2014) found that being assigned to a PACT was an independent predictor of higher risk of emotional exhaustion, as was spending 25 to 50 percent of one’s time on work that could be done by someone with less

training and working in a chaotic work environment with overwhelming work demands. On the other hand, participants on an adequately staffed PACT and those who reported that their teams used employed participatory decision making had significantly lower odds of symptoms of emotional exhaustion. Teams included a primary care provider (physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant), a nurse care manager, a clinical associate (licensed practice nurse or medical assistant), and an administrative clerk. Clinicians with 2 or more years of tenure had higher odds of burnout than those with less than 6 months on the job (odds ratio [OR] = 2.13–2.68). The authors theorize that this may be a common feature of working on a job for a long time—the longer an individual works in the same job, the more emotionally exhausted by it that person may be. Alternatively, the authors suggest, these longer-tenure workers may be more resistant to organizational change, and thus they may feel the stress of the PACT transformation more acutely, and their pre-existing habits and expectations may be more ingrained. These results point to the need for organizational interventions that are deployed over the long run and involve multiple changes that target various work system factors, such as appropriate staffing, participatory decision making, and meaning of work (e.g., increased time spent working at the top competency level or providing care that is aligned with professional values).

Using in-depth interviews, LaVela and Hill (2014) further explored the challenges associated with PACT implementation. One unanticipated negative consequence was that, although PACT was designed to break down silos and de-fragment patient care, there was a perception that the individual PACTs became silos themselves. Understaffing of PACTs, which often meant nurses splitting time between two or more PACTs, often made it difficult for these individuals to fulfill their assigned roles. In another qualitative assessment (Ladebue et al., 2016), many respondents reported that patients had a positive view of PACT and felt more involved in their care under the model. However, many also reported that the model put a strain on staff. Namely, respondents reported insufficient staffing levels, a lack of sufficient training, scheduling complications, new duties without promised resources, less time with patients, and team dysfunction when there was a weak team member.

Another team-based care delivery intervention, which was assessed in a mixed-methods study, involved assigning advanced practice nurses (APNs) to support, coach, and encourage junior doctors during overtime shifts in an urban hospital in Australia (Johnson et al., 2017). The APNs facilitated collaboration between the junior doctors and ward nurses in order to assist with patient management and delegation of tasks. The junior doctors who worked with APNs reported less stress and anxiety during their shifts,

reported receiving assistance to develop technical skills, and had more opportunities and support to develop cognitive skills. Both the APNs and junior doctors reported that the staffing structure fostered teamwork and eased many of the difficulties seen on overtime shifts. The improvements included improved delegation of tasks, greater awareness across the team of the patients on the ward, and improved interdisciplinary collaboration compared to shifts without the collaborative staffing model. Overall, the intervention had a greater effect on less experienced doctors. The authors hypothesized that early experiences of collaboration among clinicians may play a role in establishing habits that extend through the clinicians’ careers and foster interprofessional practice. Interventions that reorganize the work among team members have the potential to reduce clinician burnout, but team members must have sufficient resources to balance the demands and expectations put on the team.

With any team-based intervention or redesign, it is important to proactively and regularly monitor and, if needed, adjust changes to avoid shifting the work burden from one discipline to another.

Technology-Related Factors

A few studies point to specific strategies that HCOs can undertake to address clinician burnout and frustrations related to technology use. For example, in a small study, Lapointe and colleagues (2018) report on an assessment of a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant text-paging system that was integrated within the existing electronic health record (EHR) at a university-affiliated residency program in an urban hospital. The EHR-based text system was intended to reduce interruptions during patient care or educational activities and reduced time spent responding to traditional telephone pages. Unit clerks, nursing staff, case managers, and physicians could either use a traditional telephone number page with a request for call back or initiate a text page directly from the EHR system. The latter supported consult requests or sending communications about admissions, patient or family requests, diet orders, or medication reconciliation. The system allowed recipients to respond immediately in the EHR (e.g., place an order) without calling the sender. In

surveys of a small sample (n = 25) of resident physicians, the vast majority preferred the text system to traditional paging. Respondents reported decreases in interruptions, stress, frustration, and workload and increased communication and satisfaction with the EHR-based text system. While the survey did not measure burnout or stress with validated instruments, the results seem promising and support the view that technology that improves clinical work efficacy and efficiency can have beneficial effects on clinician burnout and well-being.

In an effort to reduce technology-related workload and administrative burden, another HCO asked all of its employees “to nominate anything in the EHR that they thought was poorly designed, unnecessary, or just plain stupid” (Ashton, 2018, p. 1789). This program led to multiple changes in the EHR (e.g., removing 10 of 12 most frequent alerts for physicians), additional staff training (e.g., regarding documentation tools), and other organizational changes (e.g., reducing the frequency of required evaluation and documentation). While the impact of the program on clinician burnout was not evaluated, such an organizational intervention seems promising since it removes activities and work that should not be performed, therefore reducing clinician workload (a major contributor to clinician burnout). Chapter 7 discusses further how technology can both prevent and reduce clinician burnout, especially if it is designed to support the real-world needs of clinicians and other members of the care team, is usable, and is properly integrated into clinical workflow.

Medical scribes have been proposed as a way of addressing clinician burnout since they can help reduce the EHR-related demands experienced by clinicians and, in particular, by physicians (e.g., the administrative burden of documentation, time spent on the EHRs outside of regular hours, the EHRs interfering with patient–clinician relationships during encounters). Scribes are trained to assist physicians in documenting patient encounters in real time. Physicians review and approve the notes drafted by scribes. Scribes can be in-house personnel (e.g., medical assistants in a primary care clinic) or outsourced personnel hired through a scribe company (Pozdnyakova et al., 2018). Scribes have been mostly used in emergency departments and primary care settings (Heaton et al., 2016). For instance, in primary care the use of medical scribes has produced improvements in physician satisfaction, including satisfaction with EHR use and clinic workflow (Pozdnyakova et al., 2018) and perceptions concerning the amount and quality of time spent with patients (Gidwani et al., 2017). In a crossover study of 18 primary care physicians in 2 primary care facilities, primary care physicians reported spending less after-hours time in EHR documentation and more time interacting with patients (Mishra et al., 2018). Scribes can help improve the timeliness of encounter documentation (Gidwani et al., 2017; Mishra et al., 2018). In general, patients report neutral or positive experiences with

medical scribes (Heaton et al., 2016). Whereas the use of medical scribes seems to improve work system factors known to increase physician burnout (e.g., reducing administrative burden), there is no clear evidence for its impact on physician burnout. In a small prospective pre–post study of six physicians in a single primary care clinic, physician burnout measured by a single questionnaire item was low at baseline and did not change after the implementation of scribes.

While adding scribes to a clinical team requires a financial investment, there is some evidence that the overall increase in efficiency that they bring leads to a net-revenue gain (Nambudiri et al., 2018). Scribes can be a meaningful addition to a team-based model and improve how a practice functions. That said, more fundamental solutions are needed to address issues of EHR design and workflow integration. Thus, it is important that the increased use of scribes does not distract health care actors from exploring and developing other solutions, such as improvements in the usability of EHR documentation (including the use of templates and macros) and the development of assistive technologies (e.g., speech recognition, artificial intelligence tools) (Bates and Landman, 2018). Chapter 7 describes technologies that have the potential to reduce clinician burnout.

Programs for Positive Clinical Work Environments

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (IOM, 2000) and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (IOM, 2001) concluded that the biggest potential for gains in patient safety comes from the ability of organizations to create the work conditions essential for high-quality care. In the context of professional well-being, the committee reviewed the evidence for two national programs designed to improve the clinical work environment, the Magnet Recognition Program®2 and the recently launched American Medical Association (AMA) Joy in Medicine Recognition Program.

Magnet Recognition Program® The American Nurses Credentialing Center’s (ANCC’s) Magnet Recognition Program® is an organizational model designed to improve the work environment for nurses in a hospital setting. The Magnet program emerged from a study by the American Academy of Nursing in 1981 to “examine characteristics of systems impeding and/or facilitating professional nursing practice in hospitals” (McClure et al., 1983, p. 2). This study suggested that the key organizational characteristics needed to support nurses were empirical outcomes, transformational

___________________

2 Registered trademark of the American Nurses Credentialing Center.

leadership,3 structural empowerment, exemplary professional practice, and new knowledge, innovations, and improvements. These components form the Magnet model and serve as a framework for improving nurses’ work environment. The model encourages organizations to improve the modifiable features of the nurses’ work environment, such as staffing adequacy, leadership, clinical autonomy, interdisciplinary effort, and professional governance; this parallels many of the work system factors that contribute to clinician burnout (see Chapter 4). As of 2019, about 10 percent of U.S. hospitals have achieved Magnet Recognition Program® designation (ANCC, 2019b).

There is some evidence that nurses in Magnet hospitals are less burned out and more satisfied with their jobs. In a comparison of nurses in non-Magnet hospitals, Kelly and colleagues (2011) found that nurses in Magnet hospitals rated their work environment better and were 18 percent less likely to be dissatisfied and 13 percent less likely to have high levels of burnout (Kelly et al., 2011; Lake, 2002; Lake et al., 2019). In a longitudinal study assessing improvements to the work environment in Magnet Recognition Program®–recognized hospitals compared with other hospitals, Kutney-Lee and colleagues (2015) found significant perceived improvements over time in the quality of the work environment (e.g., more collegial nurse–physician relations and participation in hospital affairs). By the end of the study, nurses in Magnet hospitals had significantly lower adjusted rates of high emotional exhaustion (29.7 versus 38.4 percent, p <0.001), lower job dissatisfaction (21.2 versus 30.9 percent, p <0.001), and lower intention to leave their employer (8.9 versus 13.4 percent, p <0.01) than nurses in hospitals that were non-Magnet throughout the study period. The authors concluded that better work environments in Magnet hospitals was an explanation for improved nurse outcomes, including burnout (Kutney-Lee et al., 2015). In addition to reduced burnout, job dissatisfaction, and intention to leave, there is some evidence that Magnet-recognition is associated with lower odds of patient mortality (McHugh et al., 2013). Similarly, improvements to the work environment correlate with improved patient safety (Aiken et al., 2018). A recent study also showed an association between Magnet Recognition Program® recognition and improved physician engagement (Dempsey and Lee, 2019). These studies suggest that the Magnet model is one way that HCOs can improve their work environments.

However, two systematic reviews have shown mixed results regarding the association of Magnet Recognition Program® recognition and nurse outcomes. In a 2014 systematic review, while two studies reviewed reported

___________________

3 Transformational leadership includes four components: individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, inspirational motivation, and idealized influence.

higher levels of job satisfaction among nurses in Magnet versus non-Magnet hospitals, a third study failed to find a difference in satisfaction ratings between Magnet and non-Magnet hospitals (Hastings et al., 2014). Another systematic review found mixed results in terms of nurse and patient outcomes in Magnet versus non-Magnet hospitals. Among the four studies included that assessed nurse outcomes, three showed improvements in job satisfaction, burnout, or intention to turnover. The authors of this review noted the lower quality of the research of the included studies (which were largely retrospective or cross-sectional) and concluded that it is difficult to isolate the impact of accreditation programs like the Magnet Recognition Program® from other factors (Petit Dit Dariel and Regnaux, 2015) such as potential differences in resources, culture, and leadership between hospitals that choose to seek Magnet designation and those that do not. It is worth noting that the review did not include the longitudinal study of Kutney-Lee and colleagues (2015) discussed above. Despite these mixed findings, seeking Magnet designation appears to be one way HCOs can improve the clinical work environment, at least for nurses (Lasater et al., 2019).

Pathway to Excellence®4 Program The ANCC Pathway to Excellence (Pathway) Program recognizes an HCO’s commitment to creating a positive work environment that empowers and engages its staff (ANCC, 2019a). To receive Pathway to Excellence recognition, an HCO must meet 12 standards for workplace excellence that demonstrate a positive work environment. While Pathway has not been the subject of substantial research, limited data from HCOs suggested that compliance with the Pathway to Excellence standards may be associated with better patient care and improved workforce outcomes, including reduced emotional exhaustion and higher job satisfaction among nurses (Jarrin et al., 2017).

The Joy in Medicine Recognition Program In 2019 the AMA launched the Joy in Medicine Recognition Program to recognize organizations that have demonstrated efforts to improve physician satisfaction and reduce burnout. The program grants the AMA Joy Award at three levels (bronze, silver, gold) across six competencies—commitment, assessment, leadership, efficiency of the practice environment, teamwork, and peer support. Organizations must meet the criteria for five of six competencies at either the bronze, silver, or gold level to receive the award (AMA, 2019). The Joy in Medicine Recognition Program encourages organizations to address physician burnout and satisfaction by dedicating resources and implementing workplace changes to combat it.

Case studies available on the AMA website describe approaches and specific interventions implemented by HCOs to reduce physician burnout

___________________

4 Registered trademark of the American Nurses Credentialing Center.

and improve satisfaction. The interventions include technology-related changes (e.g., collaborative and streamlined documentation, in-basket management), and teamwork changes (e.g., small group discussion) (AMA, 2017a,b,c). Because the Joy in Medicine Recognition Program just started, it is too early to know if taking the required steps to achieve recognition is associated with improvements in burnout and satisfaction among clinicians.

The Leadership Alliance The Leadership Alliance, convened by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), consists of 40 participating North American hospitals, associations, and other care systems that have developed a set of “radical redesign” principles intended to guide transformational changes in health care (Berwick et al., 2017). One of these principles is dedicated to eliminating administrative barriers that add little or no value to clinical care, interrupt clinician workflow, frustrate patients and clinicians, or are otherwise wasteful of time and resources. To accomplish this, the participating organizations asked their clinicians and patients “If you could break or change any rule in service of a better care experience for patients or staff, what would it be?” Only 22 percent of the rules identified were actual statutory and regulatory requirements. The rest were either organization-specific requirements (62 percent) or organization behaviors with little or no legal or regulatory basis (16 percent). In most cases, local organizations could change or eliminate many of the rules identified in this process without violating any legal, regulatory, or statutory requirement (Berwick et al., 2017). While the impact of this initiative on the work environment has not been evaluated, it does illustrate a relatively simple process by which local organizations can identify and eliminate wasteful and unnecessary rules that are diverting time and resources and may be contributing to clinician burden.

DESIGNING WELL-BEING SYSTEMS IN HEALTH CARE ORGANIZATIONS

As described above, the committee found a dearth of evidence-based interventions that mitigate the multitude of factors contributing to burnout. Thus, the committee concluded that there is a need to provide HCOs with guidance about which actions they can take to reduce burnout in the short term with the ultimate long-term goal of eliminating burnout. In the remainder of this chapter, the committee describes a set of principles for designing, implementing, and sustaining professional well-being systems in HCOs, drawing on a systems perspective and the literature on human factors and systems engineering. In particular, this literature (Clegg, 2000) emphasizes a methodical approach to work system redesign. These guidelines for designing well-being systems, shown in Box 5-1 and described in the remainder of this chapter, are anchored in the committee’s conceptual

framework and its systems approach. These guidelines can serve as the foundation for long-term organizational commitment to eliminating clinician burnout, improving professional well-being, and supporting the high-quality patient care.

Values, Systems Approach, and Leadership in Professional Well-Being Systems

The first set of principles in Box 5-1 outlines three areas that are foundational to successful HCOs’ professional well-being initiatives: the alignment of values, the use of a systems approach, and the engagement and commitment of leadership.

Alignment of Values

Values are the foundation of organizational culture, and they ultimately drive business success and productivity. HCOs often declare their commitment to core values such as respect, equity and inclusion, diversity, transparency, integrity, and compassion in their mission statements, on plaques on their walls, and in their marketing messages (Brinkley, 2013; Graber and Kilpatrick, 2008). Clinicians aspire to uphold similar core values as evidence of their commitment to the basic tenets of their professions. When clinician and organizational values align, clinicians are more engaged. But when values are not aligned, or become dissonant or confused, conflict, discontent, and disengagement emerge, potentially leading to burnout (see Chapters 3 and 4).

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs employees (n = 88,605) were surveyed to examine their perceptions of the ethical practices and ethical leadership in their HCO (Foglia et al., 2013). The survey questions that were most highly associated with the ethics quality in the organization were related to the fair distribution of resources, whether leaders were perceived as giving mixed messages that caused ethical conflict or uncertainty, and leadership follow-up when ethical concerns are raised. The authors suggest that when there is good alignment of stated values, behaviors, and decisions, health care workers view their organization’s culture more positively, which ultimately affects the organization’s performance, employee satisfaction, and worker engagement (Foglia et al., 2013). This could potentially have a positive effect on clinician burnout and professional well-being.

Clinicians and health care leaders may be unaware of the conditions and pressures that gradually erode the organization’s ethical climate. One of the symptoms of this erosion is the dissonance that clinicians experience in how core organizational values are reflected in decisions, policies, mandates, and the reality of the work environment. For example, HCOs may espouse a patient-centered mission but then limit the number of Medicare or Medicaid patients who can be scheduled for non-urgent outpatient visits. Similarly, organizations may claim that they value diversity of the workforce while hiring or promotion practices indicate otherwise.

Aligning organizational structures and processes with organizational and workforce values requires a sustained intentional focus on collective values. The patterns that created the conditions for values dissonance did not occur overnight, and ethical dimensions of individuals within a system are critical to successful system redesign. As Donabedian, founder of the health care quality movement, said, “Systems awareness and systems design are important for health professionals but are not enough. They are enabling mechanisms only. It is the ethical dimension of individuals that is essential to a system’s success” (Mullan, 2001, p. 140).

Use of Systems Approach

As emphasized in the committee’s conceptual model, multiple work system factors can produce imbalances in job demands and job resources, which can in turn lead to burnout and negative consequences for patients, clinicians, HCOs, and society at large (see Figure 2-1). Effectively and sustainably improving professional well-being in HCOs requires a systems approach. Clinician burnout is not inevitable; it can be reduced and even prevented. The National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience has advocated for a systems approach to dealing with clinician burnout and professional well-being (Coffey et al., 2017; Dzau et al., 2018). This systems approach is in line with similar systems approaches recommended by multiple IOM and National Academies reports to address quality of care, patient safety, and learning health care (IOM, 2000, 2001, 2007; NASEM, 2015, 2018).

Role of Governance, Leadership, and Management

The many work system factors interact with each other and are influenced by decisions and actions throughout the HCO. Therefore, a systems approach to clinician burnout should address all of the critical aspects under the control of the HCO but especially the organization’s governance and leadership. Successfully addressing the challenge of clinician burnout requires the engagement of leaders across the organization, including hospital boards, executive officers and senior leaders, department chairs, and administrative and operational leaders. As stated by Shanafelt and Noseworthy (2017, p. 129), “Leadership and sustained attention from the highest level of the organization are the keys to making progress” in addressing burnout. This statement was about physician burnout, but it applies equally to all groups of clinicians. A systems approach to addressing clinician well-being requires a commitment from leadership at all levels of the organization and should be a shared responsibility across all HCOs and their affiliated associations (e.g., the American Hospital Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges).

The current state of each HCO must be assessed and a comprehensive and coordinated organizational strategy developed to reduce burnout and cultivate professional well-being. Data and progress with respect to clinician well-being should be regularly reviewed by the HCO’s board and its executive leaders. These leaders must build organizational will to make clinician well-being a priority, remove barriers, advocate for needed regulatory reforms, and create the enabling conditions that equip clinicians and non-clinician staff with the time, resources, and skills needed to devote to this effort. Leaders and managers at the frontline care delivery level (e.g.,

unit level) are also instrumental in creating the conditions for positive work environments (Adriaenssens et al., 2015; Gunnarsdóttir et al., 2009; Li et al., 2013; Shanafelt et al., 2015).

Governance of health care organizations Attention to the well-being of clinicians is necessary at the highest levels of the organization, including the board of trustees. Shanafelt and colleagues summarized seven things governing boards should know about burnout and professional fulfillment in clinicians (Shanafelt et al., 2018):

- Burnout is prevalent among health care professionals.

- The well-being of health care professionals affects quality of care.

- Health care professionals’ distress costs organizations a lot of money.

- Greater personal resilience is not the solution.

- Different occupations and disciplines have unique needs.

- Evidence and tactics are available to address the problem.

- Interventions work.

The authors argue that HCO boards play an important role in addressing the problem by insisting that executive leaders provide regular updates on organization-specific data on clinician burnout and well-being and asking the senior leadership team to develop specific plans for improvement. Boards should also encourage and support the allocation of resources by the executive team in ways that address the issue.

Leadership One meta-analysis of leadership across industries (beyond health care) found a link between leadership constructs (e.g., transformational leadership, leadership focused on relationship with employees and abusive supervision) and burnout (Harms et al., 2017). In its review of the literature on leadership in health care, the committee encountered similar findings—HCOs with effective leaders who have good relationships with clinicians are more likely to have better clinician professional well-being, retention, and other workplace outcomes.

Much of the leadership research that the committee reviewed focused on nurses. Two recent systematic reviews reported that effective nurse leaders were essential to creating and sustaining a healthy work environment that could positively affect nursing and patient outcomes (Cummings et al., 2010a; Wei et al., 2018). Nurses working under leaders who are focused on people and relationships report higher job satisfaction than nurses working with nurse leaders focused on tasks. Studies have found associations between resonate and authentic leadership styles and positive nursing and patient outcomes.

In one study, resonant hospital-level nursing leadership styles (e.g., empathic, achievement- and relationship-focused, power and influence sharing, empowering, visionary) had significant positive relationships with patient mortality. Nurses who work with resonant nursing leaders reported that the disruption of hospital restructuring was mitigated by the leader’s style (Cummings et al., 2010b).

Another study reported that nurses who work for managers demonstrating higher levels of authentic leadership (e.g., who are perceived as hopeful and optimistic and who practice with high ethical standards and transparent values) report greater work engagement (Bamford et al., 2013). Expanding these findings, a longitudinal study found that authentic leadership was associated with a lower risk of burnout and improved nurse well-being (Spence Laschinger and Fida, 2014). Data further suggest that developing nurse managers’ “authentic leadership” behaviors to create and sustain empowering work environments may help reduce nurse burnout and increase nurse job satisfaction and retention (Boamah et al., 2017; Spence Laschinger et al., 2012). Shanafelt and colleagues (2015) described the importance of frontline leadership on the well-being and professional satisfaction of physicians who practiced in a large, integrated HCO. In a cross-sectional study, 2,813 physicians rated their immediate supervisor across a range of leadership behaviors. The composite supervisor leadership score was an independent predictor of burnout and job satisfaction of the physicians directly reporting to the physician leader; as leadership scores improved, the likelihood of frontline physicians’ burnout decreased (Shanafelt et al., 2015). Leaders who informed, engaged, inspired, developed, and recognized those working for them were considered effective leaders in this study (Shanafelt et al., 2015).

The research underscores the importance of leaders and managers in creating supportive work environments by, for example, being accessible and fostering collegial relationships (Epp, 2012). These findings can serve as a framework for leadership development programming in HCOs as part of designing, implementing, and sustaining organizational well-being systems.

Work System Redesign in Health Care Organizations’ Professional Well-Being Systems

Box 5-1 outlines three principles for work system redesign that support successful HCOs’ professional well-being initiatives. As described in Chapter 4, multiple work system factors need to be considered in order to systematically address clinician burnout and improve professional wellbeing. The committee’s review of HCO interventions found only limited published evidence for what an organization can do to address clinician burnout. Therefore, the committee relied on the literature on work design

to develop three broad principles for work system redesign. Models, theories, and approaches of work design highlight key principles of job meaning and content (e.g., variety), adequate balance of job demands and resources, and support for team work and good professional relationships (Carayon et al., 2007; Parker et al., 2001, 2017a).

First, the committee’s review of contributing factors to clinician burnout points to the role of repetitive, meaningless, low-value work that does not fit with the abilities and motivations of clinicians (see Chapter 4). Systematic efforts at work system redesign should, therefore, aim to eliminate low-value work and enhance the meaning and purpose of work. This may be accomplished by reorganizing work and care processes or by a judicious use of technology. Second, in line with the job demands–job resources model (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007, 2017) described in Chapter 4, clinicians need to have adequate organizational, informational, environmental, and technological resources to do their job in a safe, efficient, and effective manner. Finally, team-based care has been emphasized by multiple experts, health care leaders, and IOM reports (ANA, 2016; IOM, 2001; Mitchell et al., 2012; Schottenfeld et al., 2016). Developing care processes and organizational structures aimed at supporting team-based care can not only produce benefits for patients (e.g., increased care coordination, improved patient safety), but also can help reduce and mitigate clinician burnout (see examples in the section on organizational interventions earlier in this chapter). Work system factors such as social support are important facilitators for clinician well-being and can be enhanced via team-based care.

Below, the committee describes the literature on work design and on healthy work environments that provides the background for the three work system redesign principles summarized in Box 5-1.

Models and Theories of Work Design

Recent approaches to work system redesign and professional well-being use holistic systems approaches and examine the range of work factors that may create imbalances in the work system (Carayon, 2009; Smith and Carayon, 2001; Smith and Sainfort, 1989), such as (lack of) balance between effort and reward (Siegrist, 1996) or between job demands and job resources (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti et al., 2001). This is in line with the conceptual approach used by the committee to describe the work system factors that contribute to clinician burnout (see Chapter 4).

In light of the committee’s systems approach (see Figures 2-1 and 2-2), the level of frontline care delivery is a work system with multiple elements that interact with each other: the care team members, their activities and technologies, and the physical environment and organizational conditions under which they perform their activities (Carayon, 2009; Smith and

Carayon, 2001; Smith and Sainfort, 1989). Work design should therefore ensure that all work system elements and their interactions support the work of clinicians and clinical teams. For instance, using knowledge from the literature on human factors and ergonomics (Salvendy, 2006), principles for the physical design of environments (Alvarado, 2012; Carayon et al., 2011; Lyson et al., 2019) and workstations (Carayon et al., 2007) can be used to design health care facilities that promote positive interactions and support teamwork, which can in turn help reduce clinician burnout and improve well-being. The usability of technologies is another important work design principle (see Chapter 7 for additional discussion of this topic) and there are ways to quantify its impact on clinicians and clinical workflow (Zheng et al., 2010). There is a large body of knowledge on job design that provides information on design principles for positive work environments (Carayon et al., 2003, 2006; Parker, 2014, 2017a,b; Smith and Sainfort, 1989). Models of job stress also provide useful guidance on how to reduce burnout and improve professional well-being as they identify various job stressors (Cooper and Marshall, 1976; Hurrell and McLaney, 1988). See Box 5-2 for selected models of job design and job stress.

Healthy Work Environments

The nature of the overall work environment (i.e., the professional milieu in which the clinicians, staff, patients, and families experience daily health care delivery) is critical for enhancing professional well-being and improving patient care. In the nursing literature, a “healthy work environment” describes a workplace that is safe, empowering, and satisfying and that includes effective cross-disciplinary communication, collaboration, and decision making; appropriate staffing; recognition; and authentic leadership (AACN, 2019; ANA, 2019). The retention of nurses, nurse satisfaction, and patient outcomes are significantly affected by the health of the work environment. Aiken and colleagues (2008, 2011) found that nurses who worked in healthier work environments reported significantly lower rates of burnout and job dissatisfaction and better quality-of-care outcomes. For nursing, a healthy work environment is often measured on five dimensions using the National Quality Forum–endorsed Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (Warshawsky and Havens, 2011): (1) nurse participation in hospital affairs; (2) nursing foundations for quality of care; (3) nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses; (4) staffing and resource adequacy; and (5) collegial nurse–physician relations (Lake, 2002; Lake et al., 2019). Unfortunately, structured descriptors of the characteristics of a healthy work environment for other clinicians have not been as clearly articulated, although they could be expected to include many, if not all, of these dimensions.

A driver for redesigning work and improving clinician outcomes can be the adoption of work design principles, such as the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) standards for establishing and sustaining a healthy work environment: “skilled communication, true collaboration, effective decision making, appropriate staffing, meaningful recognition, and authentic leadership” (AACN, 2016, p. 10). AACN has also developed the Healthy Work Environment Assessment tool to assist organizations in monitoring their progress as they implement these standards5 (Connor et al., 2018). Although the tool was established for critical care nurses, the standards embed concepts that align with principles of good work system design and positive work environments. The effectiveness of these standards—and others like them—to improve clinician professional wellbeing warrants study.

___________________

(5) See details at http://www.aacn.org/hwe (accessed April 10, 2019).

Implementation of Professional Well-Being Systems

Implementing well-being systems requires a major organizational change, which can create new or additional sources of stress. Box 5-1 provides principles for implementing well-being systems in HCOs in a thoughtful, systematic manner. In a review of the literature on individual and organizational interventions designed to reduce or prevent pharmacists’ stress (including burnout), Jacobs and team (2018) documented effective characteristics of organizational interventions across industries that could be adapted to the pharmacy industry in the United Kingdom. Based on their review, the authors identified key criteria that are necessary for a workplace stress-reduction intervention to succeed. These criteria include top-management support to provide the resources necessary to develop and implement the intervention, active participation from employees throughout the development and implementation process, action planning and project management with clear tasks and responsibilities assigned across the organization, and changes brought on by the interventions reflected in the organizational culture to be sustainable. These criteria are in alignment with the extensive literature on change management and system redesign (Barrow and Toney-Butler, 2019; Karsh, 2004).

Infrastructure and Resources for Well-Being Systems

Given the growing importance of clinician burnout, HCOs need to build adequate infrastructure for enhancing professional well-being. This infrastructure should have sufficient resources and rely on effective organizational design principles, such as accountability, continuous measurement and improvement, and organizational learning. It is important to identify an executive leader who has the primary responsibility for facilitating and managing the efforts to address clinician burnout.

Executive leader for professional well-being As with other major organizational endeavors, an executive leader is needed to oversee and coordinate the activities aimed at enhancing professional well-being. Similar to the situation in past decades when the positions of chief medical officer, chief nursing officer, and chief quality and safety officer were created in response to the recognition of a critical unmet need for leadership within HCOs, there is now a clear need for organizations to create a senior leadership position to oversee the new suite of responsibilities to address clinician wellbeing. Much like the chief quality officer, this new leader must be able to transcend individual silos in order to catalyze progress across all divisions, departments, and work units. The committee believes it will be essential that this leader’s focus be exclusively on the professional fulfillment and

well-being of the individuals in the organization and be independent of other activities, such as efforts to improve quality or patient experience. Simply adding responsibility for clinician well-being to the duties of the chief quality officer or chief experience officer is unlikely to be successful, given that these groups already have a broad and expansive charge that will necessarily be the primary focus of their activities.

The committee agrees with a number of organizations and societies that have argued that it is important this person be a positioned at the executive officer level to have appropriate impact (Jha et al., 2019; Kishore et al., 2018). The title of this position may vary across organizations, with the “chief wellness officer” being a common choice. Other organizations designate this person as a senior or associate dean or vice president. The key responsibilities of the executive leader in charge of professional wellbeing include evaluating the current scope of the problem and reporting the results throughout the organization, benchmarking, designing and implementing an interprofessional organization-wide strategy, overseeing broad system-level efforts to drive improvement in the dimensions most relevant to the local organization, and communicating with outside entities. The qualifications required to fulfill this role are not defined by disciplinary expertise but rather reflect a relevant knowledge base and skills necessary to lead large-scale change initiatives and produce meaningful and sustainable results. Designating an executive leader dedicated to well-being in an organization will be insufficient unless a diverse team and sufficient resources are provided to allow collaborative solutions to produce effective interprofessional results (Shanafelt et al., 2019).

Professional well-being, patient safety, and employee safety Organizational efforts for tackling clinician burnout should be coordinated with activities related to patient safety and employee safety and health because many of the same work system factors influence clinician burnout as well as worker and patient safety (McCaughey et al., 2016; Weinger and Englund, 1990). For example, extended work hours and fatigue have been associated with both medical errors and needlestick injuries (Dember et al., 2009; Olds and Clarke, 2010). High workload, a major contributor to clinician burnout, also adversely affects patient safety (Aiken et al., 2002; Gurses et al., 2009; Hoonakker et al., 2011). For nurses there is good evidence that a “healthy work environment” is concurrently associated with improved patient safety, a reduction in occupational injuries, and improved nurse well-being (Wei et al., 2018). Patient safety, employee safety (e.g., occupational injuries), and clinician burnout are inter-related; they share contributory factors and may influence or affect each other.

On the other hand, improperly designed patient safety or quality improvement initiatives can have adverse effects on employee safety and

clinician well-being as well as on other aspects of patient care. Patient safety interventions that increase frontline clinician workload, time pressure, or clerical burden can unintentionally result in decreased attention to other aspects of care quality, contribute to staff burnout and job dissatisfaction, and even impair clinician health (e.g., work-related stressors that contribute to chronic illness) (Koppel et al., 2008).

The committee agrees with Yassi and Hancock (2005, p. 32) that “a comprehensive systems approach to promoting a climate of safety, which includes taking into account workplace organizational factors and physical and psychological hazards to workers, is the best way to improve the health care workplace and thereby patient safety.” Others have strongly advocated for the coordination and integration of the various goals (patient safety, occupational safety, professional well-being) into a single comprehensive safety program. Stevenson and colleagues (2013, p. 25) at Island Health in British Columbia argue for system-wide commitments to “quality and safety for all,” stating that “we must challenge the paradigms that juxtapose employee and patient safety and move beyond alignment and coordination into integration.” Despite the parallels among patient safety, occupational safety, and clinician burnout, these organizational functions within HCOs tend to be separate, reflecting the largely independent external (e.g., state and federal) infrastructures, regulations, standards, and reporting requirements of these equally laudable goals. There can be tension between the various groups and their goals as well as potential constraints with regard to organizational resources.

While there are likely benefits and disadvantages to either an integrative or collaborative approach to patient safety, occupational safety, and clinician well-being at the organizational level, the goals and organizational mechanisms need to be closely aligned and coordinated. This should include having a strong safety culture (broadly defined), educated and engaged leadership, common organizational processes or infrastructure when possible, clear frontline expectations and engagement, and effective measurement and feedback systems. At a minimum, with organizationally separate entities there must be effective communication, mutual consideration of requirements, constraints and unanticipated consequences, effective coordination, and a substantial alignment of organizational goals and resources at the most senior leadership level. Additionally, a shared focus on improving patient care can align efforts, reduce competition, and contribute to a healthier work environment.

Organizational learning Improvement at scale requires careful attention not only to which changes are theorized to result in improvement but also to how those changes will be tested, evaluated, and implemented and the experiences of the individuals experiencing the change. Organizations should

ensure that a robust learning and improvement system is in place. Such a system should enable those directly involved or affected by the changes to clearly visualize the alignment between professional and organizational values and to understand the ultimate aim of the effort, how progress toward the aim will be measured, expectations around their contribution, and the process by which their feedback and ideas will be surfaced and addressed. See the discussion of learning health system in Chapter 2.

Rewards Management in Well-Being Systems

Reward systems should compensate and recognize clinicians equitably while ensuring that they do not create additional sources of stress and burnout. As discussed in Chapter 4, extrinsic rewards can be a contributor to clinician burnout. HCOs should design and implement organizational systems and processes aimed at compensating and rewarding their workers, in particular clinicians, in a manner that cultivates meaning and fulfillment. There are not “right” or “wrong” models of compensation; however, each compensation model will have both positive and negative consequences. Among physicians, salary-based models run the risk that some people will underperform and take advantage of hard-working colleagues. Productivity-based compensation models can encourage clinicians, many of whom who already work long hours, to work even more in a manner that is unsustainable. Such models can also de-incentivize taking breaks during the work day (e.g., to see an extra patient and generate more relative value units) or vacation. Thus, like the problems with 12-hour shifts for nurses discussed in Chapter 4, the use of heavily incentive-oriented clinician compensation models will have undesirable long-term effects, including an increased risk of burnout (Shanafelt et al., 2009). There has been movement away from volume-based salary structures toward a more hybrid model of physician base salary, production and quality incentives, and other stipends (Kritzer and Mayse, 2018). Ultimately, such models are extrinsic motivators that appeal to a fiscal motive rather than to the altruistic, intrinsic motivations that drew most clinicians into health care professions originally (Pink, 2009; Steers et al., 2004).

HCOs using productivity-based compensation models should recognize that they are using a transactional model that has a high risk of eroding the human–human interaction and altruistic motivation that clinicians bring to their work. At a minimum, they should consider how to counter this risk by creating other safeguards to insure that the intrinsic motivation of clinicians is simultaneously recognized, nurtured, and supported. It will be important to more fully understand the drivers of meaningful and fulfilling work for all clinicians beyond extrinsic rewards. The recent AACN Critical Care Nurse Work Environment study shed some light on the issues facing nurses

and their workplace frustrations. Of the 54 percent of responding nurses who indicated that they planned to leave their current position within the next 12 months, the top three issues they noted as being able to influence them to reconsider leaving were better staffing (50 percent), higher salary or improved benefits (46 percent), and more meaningful recognition (39 percent), suggesting that compensation is only one of many factors that contribute to job satisfaction (Ulrich et al., 2019).

Designing organizational reward systems that are meaningful to clinicians is vital to creating a healthy work environment. Meaningful recognition refers to the mutual responsibility between clinicians and the organization in which the clinicians practice to recognize the value of their own and others’ contributions to patient care (Barnes and Lefton, 2013). For critical care nurses, the most meaningful recognition of their contribution to care comes from their patients and families (Ulrich et al., 2019). Similarly, in a national survey, U.S. physicians reported greater life satisfaction when they had long-term relationships with at least some of their patients, and more time doing personally meaningful work was strongly correlated with life and career satisfaction (Tak et al., 2017). To be meaningful, recognition cannot be an isolated event nor automatically conferred, but rather must be integrated into the fabric of the HCO through formal processes and structures.

Psychological Safety for Individuals and Organizations

HCOs need to support clinicians’ ability to discuss, report, and address burnout, its sources, and its consequences without fear of shame, retaliation, marginalization, or disrespect (Edmondson, 2018). Therefore, organizational culture should support an environment in which clinicians feel safe (i.e., psychological safety) to report and to receive individual support when experiencing burnout or other forms of distress.

For HCOs to improve, it will be necessary to first assess the current state in order to establish a baseline level of burnout and professional well-being within the organization. This is typically accomplished through organization-level surveys, but can also include other methodologies (Sharma, 2017). To achieve honest and accurate data, it is important to attend to psychological safety in the data collection and reporting processes for both individual clinicians and the organization.

Attending to psychological safety at the individual level means that surveys or other data collection should either be anonymous or confidential with appropriate firewalls and safeguards in place to ensure that the responses of an individual cannot be identified by other members of the organization and to alleviate any concerns that an individual’s responses may affect future status (e.g., credentialing or privileging decisions,

employment) in the organization. At the organization level, psychological safety means that the institution’s willingness to ask for honest and unvarnished feedback as a means for improving work environments will not be used to damage or tarnish the reputation of the organization and its leaders (Yuan, 2019). Both practices are necessary to create a trustworthy practice environment.

It is important that the results of such surveys be shared transparently with all members of an organization (e.g., those who participated in the survey). This should include both a high-level summary of the results for the organization at large and results that are specific to occupation (e.g., nurses, physicians, pharmacists, advanced practice providers) and specialty or unit. Individuals should receive reports designed to be relevant to them. For example, a nurse should receive the results of the aggregate organization-level results, results summarizing the experience of nurses in the organization, and the nurse’s work-unit-level results. When results are shared, attention should be given to creating an atmosphere of learning. It is critical that organizational leaders avoid any perception of blaming frontline staff for the results or exerting pressure for them to remediate the results (see above discussion on organizational learning). Additionally, when solutions can be co-created rather than imposed, the likelihood of meaningful and sustainable progress is possible (see below discussion about clinician participation).

Although the committee is in favor of transparent sharing of data across and within the organization, there are downsides to the public reporting of the survey data, especially for the purposes of ranking or comparing HCOs. Such public-ranking systems often have negative consequences and create perverse incentives. For example, the public rating systems of the “best hospitals” in the United States has led organizations to try to game the system and the metrics by which they are ranked, rather than to engage in authentic efforts to improve the underlying factors (e.g., quality) that the ranking system is intending to capture. Given the highly subjective nature of questions about burnout and well-being, organizations would have ample opportunity to engage in subtle or overt coercion and manipulation of results. Individual employees could also lose with the public reporting of results since their livelihood is tied to how their organization performs (Yuan, 2019). Public reporting could also influence contracting and the ability to recruit clinicians. Thus, one could easily envision an administrator telling clinicians, “Be sure you remember what a great place this is to work when you fill out your survey so we can recruit people to the open positions and get back to full staffing.” Hence there are tremendous pressures that may prompt euphemistic rather than honest reporting when psychological safety is not created for both individuals and organizations.

Clinician Participation in Enhancing Professional Well-Being

The transformation of HCOs to address clinician burnout needs to be driven by leadership commitment (see Box 5-1), but also requires significant input and involvement from clinicians, who will co-design the solutions and implement the organizational decisions. Such a human-centered design approach with genuine clinician participation (Østergaard et al., 2018), which has been recommended and is being adopted in other health care improvement domains including health information technology design and patient safety, needs to be extended to address clinician burnout (see Chapter 2 for more information on human-centered design). In this human-centered design approach, clinicians are intimately involved in co-designing interventions to improve their work environment and reduce burnout. The co-design approach with genuine clinician participation may actually foster the development of innovative approaches to reduce clinician burnout (Wolstenholme et al., 2017). The most meaningful and sustainable improvements often involve the active participation of those closest to the work (Cotton et al., 1988; Pasmore and Fagans, 1992). Not only should clinicians be asked about their degree of burnout, but they should have an active role in translating their insights, experiences, and expertise into identifying, testing, evaluating, implementing, and continually enhancing proposed improvements that foster well-being and a healthy work culture. The principle of “Nothing about me, without me” applied to patient empowerment and engagement should also be applied to clinicians as HCOs work to create the necessary conditions that foster their well-being.

Clinician participation in developing and implementing solutions for addressing burnout can also be a solution to reducing burnout (Jackson, 1983) as it provides a path for engaging clinicians, giving them opportunities to work with others (social support) and to learn from others (meaning in work), and allowing them to exert greater control over their work environment (autonomy) (Spector, 1986). In addition, since organizational changes can be stressful because of the uncertainty in what the future work environment will look like and of the extra demands to participate in improvement activities, the participation of clinicians in the change process can provide the channels for them to support each other and bring up ideas on how to better manage the change.

KEY FINDINGS

HCOs are a powerful determinant of clinician burnout and have a critical role to play in reducing clinician burnout. There is evidence that interventions focused on work organization can improve burnout. The evidence also indicates that individual-focused strategies may be beneficial but not sufficient to address clinician burnout and that they need to be embedded

in organizational efforts. Furthermore, organizational interventions should be deployed over the long run and should involve multiple changes that target various work system factors, such as appropriate staffing, participatory decision making, and the meaning of work (e.g., increased time spent working to top of one’s competency level). The committee, however, concluded that there is no quick fix to eliminating burnout; there is no single solution at the HCO level.

To identify opportunities to design interventions that address the myriad factors that contribute to burnout, the committee reviewed systematic approaches based on human factors and systems engineering methods and principles and on knowledge from organizational design and change management. The committee concluded that much is known about the characteristics of good work systems that produce professional well-being (e.g., work design theories and models) as well as about approaches for improving work systems and well-being (e.g., human-centered design). HCOs can use this knowledge to foster organizational learning and improvement in addressing clinician burnout and enhancing well-being. This is the essence of the committee’s proposed guidelines for designing the well-being systems described in this chapter. Well-being systems require sustained commitment, leadership, infrastructure, resources, accountability, and a culture that supports clinician well-being. HCOs should support the participation of clinicians in co-designing solutions to address burnout and foster wellbeing. A key approach to the sustainability of organizational interventions to address clinician burnout is a continuous improvement model that includes feedback and organizational learning (see the feedback loop of improvement and learning in the committee’s systems model in Figure 2-1).

REFERENCES

AACN (American Association of Critical-Care Nurses). 2016. AACN standards for establishing and sustaining healthy work environments: A journey to excellence. Aliso Viejo, CA: American Association of Critical-Care Nurses.

AACN. 2019. Healthy work environment. https://www.aacn.org/nursing-excellence/healthywork-environments?tab=Patient%20Care (accessed May 24, 2019).

Adriaenssens, J., V. De Gucht, and S. Maes. 2015. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review of 25 years of research. International Journal of Nursing Studies 52(2):649–661.

Aiken, L. H., S. P. Clarke, D. M. Sloane, E. T. Lake, and T. Cheney. 2008. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration 38(5):223–229.

Aiken, L. H., D. M. Sloane, S. Clarke, L. Poghosyan, E. Cho, L. You, M. Finlayson, M. Kanai-Pak, and Y. Aungsuroch. 2011. Importance of work environments on hospital outcomes in nine countries. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 23(4):357–364.

Aiken, L. H., D. M. Sloane, H. Barnes, J. P. Cimiotti, O. F. Jarrín, and M. D. McHugh. 2018. Nurses’ and patients’ appraisals show patient safety in hospitals remains a concern. Health Affairs 37(11):1744–1751.

Alvarado, C. J. 2012. The physical environment in health care. In P. Carayon (ed.), Handbook of human factors and ergonomics in health care and patient safety. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group. Pp. 215–234.

AMA (American Medical Association). 2017a. Creating Joy in Medicine™ in Baltimore, MD: A case study. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702524 (accessed May 24, 2019).

AMA. 2017b. Creating Joy in Medicine™ in Rochester, MN: A case study. https://edhub.amaassn.org/steps-forward/module/2702523 (accessed May 24, 2019).

AMA. 2017c. Creating Joy in Medicine™ in Salt Lake City, UT: A case study. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702526 (accessed May 24, 2019).

AMA. 2019. AMA Joy in Medicine Recognition Program. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association.

ANA (American Nurses Association). 2016. Promoting patient-centered team-based health care. https://www.nursingworld.org/~4af159/globalassets/docs/ana/ethics/issue-brief_patient-centered-team-based-health-care_2016.pdf (accessed July 15, 2019).