2

A Framework for a Systems Approach to Clinician Burnout and Professional Well-Being

To consider approaches for improving patient care by supporting the professional well-being of clinicians, the committee developed a conceptual framework that clarifies the structure and dynamics of the system in which clinicians work and reveals potential levers for change. The committee’s framework for a systems approach to clinician burnout and professional well-being is based on theories and principles from the fields of human factors and systems engineering, job and organizational design, and occupational safety and health. Throughout the report, the committee applies this framework to examine many important aspects of the current system and to identify strategies that will foster healthy and safe care systems for the nation’s patients and clinicians. To set the context for the rest of the report, this chapter presents the definitions of burnout, professional wellbeing, and resilience; gives an overview of systems approaches informing

___________________

1 Excerpted from the National Academy of Medicine’s Expressions of Clinician Well-Being: An Art Exhibition. To see the complete work by Zohal Ghulam-Jelani, visit https://nam.edu/expressclinicianwellbeing/#/artwork/347 (accessed January 30, 2019).

the committee’s framework; and presents the committee’s systems model of burnout and professional well-being.

DEFINITIONS OF BURNOUT, PROFESSIONAL WELL-BEING, AND RESILIENCE

“Burnout,” “well-being,” and “resilience” are three distinct terms used in the Statement of Task and, more broadly, in the scientific and popular literature about issues in the work environment for clinicians. Fundamentally, burnout is an obstacle to professional well-being. That said, the absence of burnout does not necessarily indicate the presence of overall well-being. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared that “health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 2006, p. 1). Well-being is a function of complex interplay of physical, emotional, mental, social, and spiritual factors that interact with the ecosystem within which the person resides. In psychology and related fields there is no agreement about the number of factors that constitute well-being (Gander et al., 2016). Many of the same factors that contribute to burnout in some clinicians may lead to other forms of diminished well-being in others (Chari et al., 2018).

In this report, the committee focuses on burnout as a barrier to professional well-being (defined further below). The committee acknowledges that the absence of burnout does not by itself result in a state of professional well-being. However, the committee believes that addressing the drivers of burnout (as well as barriers to well-being and optimal performance) is critical to assisting clinicians reach the goal of professional well-being and will also help health systems in which clinicians work or train reach their maximum potential. The committee acknowledges that there are significant differences in how vulnerable individual clinicians are to burnout because personal resilience and other individual and contextual factors influence each individual’s capacity and approaches to dealing with work-related stress (discussed further in Chapter 4). Below, the committee defines the concepts of burnout, professional well-being, and resilience in relation to the study approach.

Burnout

Burnout is a work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s (Schaufeli et al., 2009). It is a well-established construct that has been the subject of thousands of publications, most focused on professionals who directly serve other individuals (e.g., human service workers, also referred to as the “helping professions”). In 1976 Christina Maslach, a social psychology researcher, further developed the concept after conducting a series of interviews of human service workers (Maslach, 1976), leading ultimately to the definition that burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach et al.,

1996) (see Box 2-1). Although Maslach’s definition of burnout and the accompanying measurement tool, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), are the most widely used approaches (Schaufeli et al., 2009), researchers have conceptualized and defined burnout in various other ways as well. All of these approaches agree on at least one thing, however—that the key feature of burnout is mental exhaustion due to occupation-related factors (Salvagioni et al., 2017).

Consistent with these previous definitions, WHO recently updated its definition of burnout to this:

Burn-out is a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions: (1) feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; (2) increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and (3) reduced professional efficacy. Burn-out refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life.

Burnout has an ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision) code of QD85. It should be noted that WHO defines burnout as a problem associated with employment rather than as an individual mental health diagnosis and that it is considered to be distinct from mood disorders (WHO, 2019).

Burnout is generally considered to be a context-dependent phenomenon that is due to work-related stressors and that primarily affects professional attitudes and behaviors, although it can have ramifications on the personal front as well. It differs from depression, which is a mental health diagnosis that has well-defined diagnostic criteria and is context-independent (Melnick et al., 2017). In North America, burnout is considered to be a work-related syndrome, whereas in Europe it is thought of more as a medical diagnosis—a situation that results in the availability of occupational resources and access to paid work leave for those who have high degrees of burnout (Schaufeli et al., 2009). Philosophically, since the drivers of burnout originate in the work environment, the committee favors the occupational framework that views and addresses burnout as a system issue rather than as a personal mental health diagnosis. While individually targeted interventions may help individual clinicians, they will not address the systemic issues that drive the burnout problem in the first place.

The evidence indicates that burnout is best thought of as a continuous variable, rather than as a dichotomous one; that is, there are “degrees” of burnout with severity in the various dimensions—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and loss of personal accomplishment—manifesting differently in different individuals (Maslach et al., 1997). Greater severity across these dimensions has been shown to relate to multiple negative professional and personal outcomes among clinicians (see Chapter 3). Although it may be more accurate to consider burnout as a continuous variable, research studies often treat it as a dichotomous variable; approaches to dichotomizing burnout, as well as commonly used measurement tools for burnout, are discussed in Chapter 3. The dichotomous-versus-continuous-variable issue for burnout is analogous to the situation with hypertension (Palamara et al., 2018). Blood pressure is a continuous variable for which higher numbers are associated with a greater risk of adverse consequences. Nonetheless, thresholds are set to dichotomize individuals as having or not having “hypertension,” even though it is recognized that not all individuals thus characterized as hypertensive have an equally severe condition. All of these features of blood pressure characteristics (i.e., continuous variable, higher scores associated with greater risk, and thresholds identified as associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes) are consistent with the construct and data on burnout. As with hypertension, any thresholds set to dichotomize burnout should be based on objective data indicating a relationship between the threshold and adverse or undesirable outcomes.

Professional Well-Being

Professional well-being is related to the broader concept of psychological well-being, or subjective well-being, which stems from various life

and non-work sources of satisfaction enjoyed by individuals (Diener, 2000). Worker well-being (which in this report applies to clinicians) is defined “as an integrative concept that characterizes quality of life with respect to an individual’s health and work-related environmental, organizational, and psychosocial factors. Well-being is the experience of positive perceptions and the presence of constructive conditions at work and beyond that enables workers to thrive and achieve their full potential” (Chari et al., 2018, p. 590). Professional well-being is further conceptualized as job-related and is a function of being satisfied with one’s job, finding meaning in one’s work, feeling engaged while at work, having a high-quality working life, and finding professional fulfillment in one’s work (Danna and Griffin, 1999; Doble and Santha, 2008). Although professional well-being can be measured by a variety indicators (Chari et al., 2018), work engagement, linked to the motivational aspects of work, has been a common proxy for professional well-being. Work engagement is a positive, fulfilling state of mind characterized by “vigor, dedication, and absorption” with work (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2010, p. 2).

Although research suggests that professional well-being can be influenced by both the physical and the psychological aspects of work (Chari et al., 2018), little is known about how to best measure professional wellbeing, what contributes to professional well-being, and which benefits are derived from the professional well-being of clinicians (Brady et al., 2018; Diener et al., 2015).

Resilience

While there is no generally agreed-upon definition of resilience (Aburn et al., 2016), the term generally reflects the ability of a person, community, or system to withstand, adapt, recover, rebound, or even grow from adversity, stress, or trauma (IOM, 2012b; Luthar et al., 2000; Szanton and Gill, 2010). Resilience is something that emerges (or not) as a sum of an individual’s or system’s traits, states, external stimuli, mediators, and prior responses. Resilience can be viewed as a kind of “dynamic adaptive capacity” to support the ability to rebound and to ultimately improve the function of an individual, community, or system (Szanton and Gill, 2010). All entities, including health care systems and the clinicians who work in these systems, have limits to the magnitude of changes, disturbances, or stressors they can absorb before their structures, processes, and relationships begin to degrade. When stress overpowers resilience, performance and, in the case of individuals, health can degrade. In this report the term “resilience” is used to refer both to individual clinicians and to the clinical systems in which they work. The former usage, individual resilience, is discussed in Chapter 4, under individual mediating factors.

A SYSTEMS VIEW OF CLINICIAN BURNOUT AND WELL-BEING

The committee’s framework for a systems approach to clinician burnout and professional well-being is based on theories and principles from the fields of human factors and systems engineering and job and organizational design (see Box 2-2) and draws on the literature and programs from the field of occupational safety and health (Lamontagne et al., 2007; NIOSH, 2019). The committee’s systems framework emphasizes identifying interventions aimed at the critical factors contributing to burnout in order to foster an improved state of professional well-being (defined above) while improving patient care. The evidence-based interventions that the committee highlights in the report (see Chapter 5) focus on organizational strategies addressing the primary drivers of burnout (see Chapter 4). The committee believes that burnout prevention efforts should involve both risk reduction and wellness promotion and that every stakeholder at every level of the system must embrace the responsibility to build a healthy and safe work environment and to foster a culture of wellness while also supporting individuals’ efforts to improve their own well-being. The committee’s framework for a systems approach to clinician burnout and professional well-being is in line with recommendations in multiple Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Academies reports targeting quality of care (IOM, 2001), patient safety (IOM, 2000), diagnostic errors (NASEM, 2015), global quality of care (NASEM, 2018), and learning health care (IOM, 2007). The literature offered many opportunities to better understand work organization, job stress, and professional well-being and provided the committee with a number of health work design approaches to consider. Chapter 5 further discusses these approaches and their integration in well-being systems.

A SYSTEMS MODEL OF CLINICIAN BURNOUT AND PROFESSIONAL WELL-BEING

The committee concluded that the processes associated with clinician burnout and professional well-being are complex and occur over time within the context of a multi-level system that influences those processes. The committee’s systems model of clinician burnout and professional wellbeing is an adaptation of various models of multi-level systems in health care and workplace safety that describe hierarchical levels that interact with each other to influence the health care process (Berwick, 2002; Carayon et al., 2015; NASEM, 2018; Rasmussen, 2000; Shanafelt and Noseworthy, 2017; Skeff, 2018).

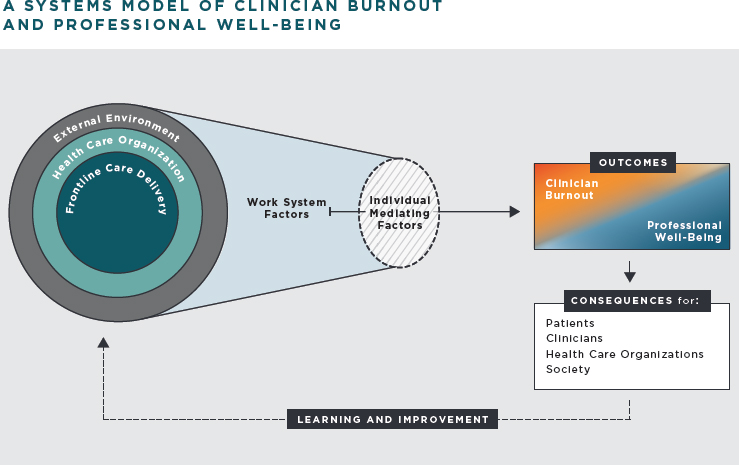

Figure 2-1 is the committee’s conceptual model of the clinical work system and its relationship to burnout and professional well-being and the consequences.2 In this model, there are three interacting system levels—frontline care delivery, health care organization, and external environment—whose characteristics influence the factors contributing to burnout and professional well-being. Decisions made at the three levels of the system have an impact on the work factors—job demands and resources—that clinicians experience.

The collection of job demands and resources can be balanced or optimal and thus enhance professional well-being, or it can be unbalanced or less than optimal and thus predispose clinicians to burnout (Carayon, 2009; Demerouti et al., 2001; Siegrist, 1996; Smith and Sainfort, 1989). Individual factors, such as personality traits and personal experiences, play a role in the effects of job demands and resources, although that role is less important than that of the job demands and resources themselves. See Chapter 4 for a further description of the various factors that contribute to burnout. See Chapter 3 for a description of the consequences that burnout and professional well-being have for patients, clinicians, health care organizations, and society.

___________________

2 The concepts articulated in the framework are intended to address burnout and professional well-being in health care clinicians and learners.

Ideally a system will continuously learn and improve using measurements of burnout and professional well-being and findings about the consequences. Learning and improvement activity can be integrated into the system via feedback loops, which lead to changes in various elements at various levels of the system; these changes in turn affect job demands and resources and ultimately improve the outcomes that clinicians experience.

SYSTEM LEVELS AND INTERACTIONS

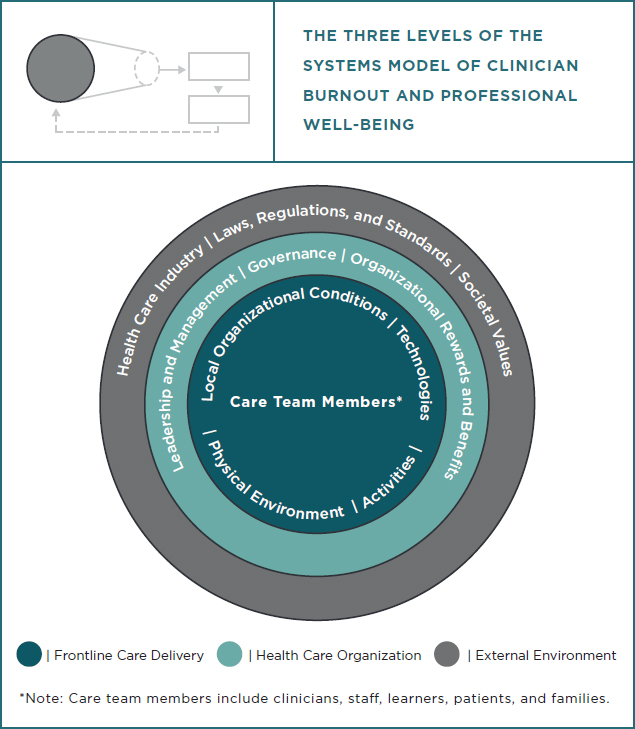

Figure 2-2 shows the three interacting levels of the committee’s systems model of clinician burnout and professional well-being. At each level, decisions are made that influence the balance between job demands and resources (i.e., psychosocial work factors).

Frontline Care Delivery

Frontline care delivery is where interactions between clinicians and patients occur in the local context. In sociotechnical systems terms, frontline care delivery is the “work system” (Carayon, 2009; Kleiner, 2008). Frontline care delivery takes place in the context of a care team, including clinicians, learners (including trainees and students), patients and families, and support staff (Skeff, 2018), who engage in activities using various tools and technologies according to established policies and procedures within the available resources and infrastructure. Clinical care team members have individual characteristics (e.g., age and gender, educational background, clinical experience). The parallel and often interacting activities of the care team members occur in a physical environment and under local organizational conditions (e.g., the role definitions of team members, team cohesion, communication and coordination among the team, unit leadership). Organizational conditions include how members of the care team perceive the organizational culture. This perception informs the organizational climate. This description of frontline care delivery is based on an established work system model (Smith and Carayon, 2001) and is consistent with the description of microsystems3 in health care quality improvement (Mohr and Batalden, 2002; Nelson et al., 2002).

The Health Care Organization

The health care organization, the second level of the systems model, is composed of multiple interconnected work systems that share common structures and processes. Many of their decisions and activities are interdependent; for instance, the transfer of a patient from the emergency department to an inpatient unit requires extensive unit-to-unit communication, coordination, and collaboration, with the different units needing to have common expectations and norms. Thus, the health care organization is characterized by a wide variety of elements (Trist, 1981), including organizational culture, payment and reward systems, the management of human capital/human resources, leadership and management style, and organizational policies (e.g., regarding scheduling, vacation, part-time/full-time, and the use of electronic health records [EHRs] and other technologies). See Chapter 5 for further description of the influence and role of health care organizations in clinician burnout.

___________________

3 Microsystems are the small clinical care teams that provide care during most health care encounters.

The External Environment

The third and final level of the systems model is the external environment, which includes political, market, professional, and societal factors. This level contains opportunities and constraints that influence decisions and actions at the health care organization level and the work done by clinicians at the frontline care delivery level. Many elements of the external environment play a role in clinician burnout and well-being (Trist, 1981), including structural changes in the U.S. health care industry and the landscape of laws, regulations, and standards for the oversight of U.S. clinicians (e.g., those relating to payment policies, clinical documentation, quality measurement and reporting, prescription drug monitoring, privacy rules and procedures, pre-authorization forms, professional and legal requirements for licensure, board certification, and professional liability). Societal factors, such as changing attitudes, expectations, and values about health care, are also part of the external environment influencing the work system. See Chapter 6 for a discussion of these elements of the external environment.

Frontline care delivery, the health care organization, and the external environment all influence each other. For instance, documentation requirements by regulators and insurance entities represent an element of the external environment that influences what health care organizations do with regard to EHR implementation and configuration, which in turn influences the actual work of the care team and, in particular, of clinicians who directly interface with the EHR (Erickson et al., 2017). Influences between system levels go both ways. What happens at a lower level can influence what happens at a higher level. An example of this upward influence from the health care organization to the external environment was provided in the 2018 National Academy of Medicine report on interoperability (Pronovost et al., 2018), which supports the belief that if health care organizations demanded more usable, safer, and interoperable health information technology (IT) as part of their purchasing decisions, it would spur vendors to make developing this improved health IT a priority.

IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS RELATED TO THE SYSTEMS MODEL

Learning Health Care Systems

As shown in the committee’s systems model of clinician burnout and professional well-being (see Figure 2-1), learning and improvement feeds back into the three levels of the system in a process of continuous improvement. The model is consistent with the work of the landmark report

produced by the IOM Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, which laid out the foundation for building more effective learning processes and systems across health care (IOM, 2012a). The report called for improving organizational learning throughout the health care industry and highlighted the emerging capabilities offered by information technologies. The report also described “progress in human and organizational capabilities and management science” (IOM, 2012a, p. xii) that could be used to better design health care work systems and improve outcomes for both patients and clinicians. Box 2-3 displays key characteristics of learning health care systems.

The foundation for a learning health care system is “continuous knowledge development, improvement and application” (IOM, 2012a, p. x). This approach is relevant not only to improving care processes and outcomes for patients, but also to improving health care work systems and the work experiences of clinicians. Expanding the focus of health system improvement beyond the triple aim (Berwick et al., 2008) to the quadruple aim (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014; Sikka et al., 2015) is in line with this committee’s proposed approach to expand the concept of learning health care systems to include improving clinician professional well-being.

The 2012 IOM report on learning health care highlights the need to improve health care work systems so as to better support clinicians’ work as well as the need to allow clinicians to continually learn and improve in their work (IOM, 2012a). In addition to the roles played by data collection, measurement, and the greater use of IT (Budrionis and Bellika, 2016), it is important to consider the “human capital” of the learning health care system. For example, consistent with the management and organizational design literature (Argyris and Schön, 1978; Hundt, 2012), clinicians’ workload and work environment must support continual learning and participation in improvement activities. This is based on (and fosters) an organizational culture aimed at continually improving care work systems and processes (Grossman and Salas, 2011).

Human-Centered Design

The learning and improvement feedback loops of the committee’s systems model are in line with human-centered design (HCD), an approach anchored in human factors engineering and aimed at designing work systems that match the needs of the users (clinicians) and, therefore, producing usable, healthy, and safe work systems. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), an international standard-setting body composed of representatives from various national standards organizations, has defined HCD as an “approach to systems design and development that aims to make interactive systems more usable by focusing on the use of the system

and applying human factors/ergonomics and usability knowledge and techniques” (ISO, 2010, p. 2). A key aspect of HCD is the participation and involvement of users through design and implementation whereby inputs from users and stakeholders are incorporated in a systematic approach to work system redesign.

HCD allows iterative design, prototyping, and evaluation of a solution at all system levels, anticipating its effects on the entire work system, that is, individuals, tasks, technology, and the physical and organizational work environment. If appropriate, these design–evaluation–redesign cycles may be performed in simulations (computer-based modeling or clinical simulations of increasing fidelity) under both routine and non-routine conditions. Once a solution has been refined, it can be tested in small pilot trials in a particular care unit. Evaluations need to consider the contextual factors related to success or failure and to seek generalizability across different units, conditions of use, and user populations. Formal assessment and continuous improvement should continue into the post-implementation phase.

The HCD approach can be scaled according to the magnitude and type of problem as well as to the time and resources available. Experience shows that although such techniques may impose additional up-front effort, that effort will be more than made up for by decreased (1) difficulties and expense of initial implementation, (2) time to full adoption, (3) number of workarounds required, (4) rework or other mitigations for design failures, and (5) harm from unintended errors and other negative consequences (Erwin and Krishnan, 2016; Harte et al., 2017; Sanders and Stappers, 2013). HCD should be implemented at multiple system levels, in particular by health care organizations in their effort of reducing clinician burnout and implementing well-being systems (see Chapter 5) and by stakeholders of the external environment who design new policies and need to anticipate potential negative consequences such as clinician burnout (see Chapter 6).

Professionalism

Health professions share an idealistic set of values, codified in historical documents such as oaths (Hippocrates, Maimonides), pledges (Nightingale pledge, Robb’s nursing ethics statement), and more contemporary codes of ethics that describe the aspirational expectations of members of professional organizations (ACP, 2019a; ADEA, 2005; AMA, 2001; ANA, 2015; APA, 2013). These all share a focus on the primacy of clinicians’ dedication to the well-being of the patient.

Professionalism has been defined to include such attributes as integrity, altruism, fairness, compassion, and respect for the dignity of all persons, and it has informed the development of competencies that have been applied across the health care professions (ACP, 2019b; ANA, 2015).

Contemporary codes of ethics have expanded the concept of professionalism to include obligations of clinicians to address transparency and honesty, the appropriate management of conflicts of interest, confidentiality, stewardship of resources, social justice, evidence-informed decision making and treatment, and preserving the integrity of the profession. Increasingly, these codes acknowledge the interplay between the well-being of clinicians and the quality of care they can deliver to those they serve. The ANA code (ANA, 2015), for example, obliges nurses to preserve their own integrity and well-being in order to continue to uphold their ethical commitments to the people they serve. The World Medical Association (2017) revised the Declaration of Geneva (the contemporary Hippocratic oath) by adopting a requirement that obligates physicians to “attend to their own health, well-being, and abilities in order to provide care of the highest standards” (Parsa-Parsi, 2017, p. 1971).

Threats to professionalism mirror work-related stressors thought to contribute to clinician burnout, such as interpersonal conflict, technology, market forces, health care systems strain, and broader sociological shifts in the role of physicians in society (ABIM Foundation, 2005; ANA, 2015) (see Chapter 4). As discussed below, the sources of these threats to professionalism originate from all levels of the system: frontline care delivery, the health care organization, and the external environment (see Figure 2-2).

Threats to Professionalism and Frontline Care Delivery

Unprofessional behaviors, including threats of retaliation, disrespectful and disruptive behaviors (Dang et al., 2016; Hickson et al., 2007; Reddy et al., 2012), harassment, and other issues, occur at the frontlines of care. For decades, nurses have identified ineffective or conflictual professional relationships as a source of moral distress (Burston and Tuckett, 2013; Hiler et al., 2018), which in turn is a factor that contributes to burnout (Moss et al., 2016). Physicians in training have reported longstanding patterns of intimidation, retaliation, and disrespect (Karim and Duchcherer, 2014; Martinez et al., 2017) that can undermine their ability to speak up about clinical concerns (Martinez et al., 2017). Other disciplines, including dentistry (Rowland et al., 2010), have reported similar patterns. If organizations have a culture that tolerates lapses of ethical behavior, that discourages team members to speak up, or that erodes personal integrity, dignity, and sense of fairness—all of which contribute to moral distress (Atabay et al., 2015; Epstein et al., 2019; Hiler et al., 2018; Rathert et al., 2016)—there is an increased risk of clinician burnout, poor professional well-being, and the consequences described in Chapter 3.

Over the past three decades there has also been a discernable shift from medical paternalism to models of shared decision making that emphasize

the role of patients in health care decisions (IOM, 2001; Oshima Lee and Emanuel, 2013). This shift has created a tension between clinicians’ desire to respect patient autonomy and the pressure they feel from being held to quality measures. These two goals may be in conflict with each other, and more research is needed to better understand the relationship between shared decision making, patient outcomes, and how clinicians can effectively include patients in clinical decisions (Hargraves et al., 2016; Montori et al., 2017). The increased emphasis on shared decision making (i.e., including patients to a greater extent in the process and planning of their health care), when done properly, actually leads to more trust between clinicians and patients and gives clinicians more professional fulfilment. This shift could also create more clinician autonomy since shared decision making requires both parties to work together to personalize the patient’s care and maximizes the likelihood that the highest value care (for that patient) will be delivered.

Threats to Professionalism and Health Care Organizations

Clinicians’ primary obligations to patients may conflict with organizational priorities driven by economic and business interests (Rushton and Broome, 2015). Clinicians are buffeted by conflicting pressures that depend on the local context. These pressures include cost reduction, personal or organizational revenue enhancement, and population health interventions, which sometimes conflict with individual patient preferences or needs. Volume-driven throughput incentives, pressures to “do more with less,” and complex regulations (see Chapters 5 and 6 for additional details) confront clinicians with ethical tensions among their obligations to serve individual patients, to be responsible stewards of health care resources, and to contribute to the solvency of their health care organizations. This constant dissonance can be cumulative, culminate in high levels of work stress, and erode even the most resilient clinician’s professional well-being.

Threats to Professionalism and the External Environment

Clinicians’ first duty is to provide care for individuals who need health care services. The ability to do so, however, is influenced by multiple factors outside the sphere of direct influence for most clinicians and even of the health care organizations in which they work. These factors, which contribute to individuals’ health and their access to and the quality of care, include local and national public health issues (e.g., access to clean water and air, affordable housing and nutrition, health education), health care financing (e.g., treatment coverage decisions), and the economic pressures on the health care industrial complex (e.g., the rising cost of medical technology) (Adler et al., 2016). Clinicians have high levels of altruism and generally

want to address patients’ needs. Doing so, however, can be difficult, if not impossible, given multitude of socioeconomic determinants of health and societal constraints.

Health care organizations committed to upholding the “quadruple aim” (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014) are taking intentional and strategic steps to create the culture and conditions for clinicians to practice in accordance with their ethical mandates and to fulfill their social covenant with society. Leveraging the Charter on Professionalism for Health Care Organizations, and its recommendations relating to patient partnerships, organizational culture, community partnerships, and operations and business practices, may be a promising avenue for achieving needed culture change (Egener et al., 2017). The charter espouses developing organizational accountability for creating the conditions for individual professionalism to thrive by focused and sustained attention to systemic barriers and enablers of organizational professionalism. Others have called for shifting organizational cultures to embrace humanism as a means for enabling professional and ethical practice (Rider et al., 2018). Engaging humanistic practices throughout the organization are necessary to align professional and organizational values, norms, and practice and to foster professional well-being.

KEY FINDINGS

Burnout is a work-related phenomenon. WHO defines burnout as a problem associated with employment, not as an individual mental health diagnosis, and sees it as distinct from mood disorders. Maslach’s definition of burnout—a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment—and the accompanying measurement tool, the MBI, are the most widely used definition and measurement tool in studies of clinician burnout. Definitions of professional well-being reflect a clinician’s experience of positive perceptions and the presence of constructive conditions at work and beyond, enabling the achievement of one’s full potential. Professional well-being is further conceptualized as job-related and generally a function of job satisfaction, finding meaning in work, feeling engaged and fulfilled with work, having a high-quality working life, and professional fulfillment. However, little is known about how to best measure professional well-being, what contributes to professional well-being, and which benefits are derived from the professional well-being of clinicians. Resilience generally reflects the ability of a person, community, or system to withstand, adapt, recover, rebound, or even grow from adversity, stress, or trauma. The identification of interventions aimed at tackling the critical factors contributing to burnout is a way of fostering an improved state of professional well-being while improving patient care. Personal resilience and other individual and contextual factors influence

each individual’s capacity and approaches to dealing with work-related stress.

Theories and principles from the fields of human factors and systems engineering, job and organizational design, and occupational safety and health—which underlie the committee’s model for a systems approach to clinician burnout and professional well-being—reveal many opportunities to better understand work organization, job stress, and professional well-being as well as healthy work design approaches. In the committee’s model, there are three system levels—frontline care delivery, health care organization, and external environment—that together influence the factors contributing to burnout and professional well-being. Decisions made at the three levels of the system have an impact on the work factors—job demands and resources—that clinicians experience.

Other aspects of the committee’s model of clinician burnout and professional well-being include the importance of learning and continuous improvement processes, human-centered design approaches that focus on the use of the system and applying human factors and ergonomics and usability knowledge, and the recognition of the professional oaths and values that motivate clinicians.

REFERENCES

ABIM Foundation. 2005. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter. Philadelphia, PA: ABIM Foundation.

Aburn, G., M. Gott, and K. Hoare. 2016. What is resilience?: An integrative review of the empirical literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing 72(5):980–1000.

ACP (American College of Physicians). 2019a. ACP ethics manual, 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians.

ACP. 2019b. Physician charter on professionalism. https://www.acponline.org/clinical-information/ethics-and-professionalism/physician-charter-on-professionalism (accessed June 5, 2019).

ADEA (American Dental Education Association). 2005. ADEA dental faculty code of conduct. https://www.adea.org/about_adea/governance/ADEA_Dental_Faculty_Code_of_Conduct.html (accessed April 12, 2019).

Adler, N. E., D. M. Cutler, J. E. Fielding, S. Galea, M. M. Glymour, H. K. Koh, and D. Satcher. 2016. Addressing social determinants of health and health disparities: A vital direction for health and health care. Discussion paper. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

AMA (American Medical Association). 2001. AMA code of medical ethics. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association.

ANA (American Nursing Association). 2015. ANA code of ethics. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only (accessed April 11, 2019).

APA (American Psychiatric Association). 2013. The principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Argyris, C., and D. A. Schön. 1978. Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Atabay, G., B. G. Cangarli, and S. Penbek. 2015. Impact of ethical climate on moral distress revisited: Multidimensional view. Nursing Ethics 22(1):103–116.

Berwick, D. M. 2002. A user’s manual for the IOM’s “quality chasm” report. Health Affairs 21(3):80–90.

Berwick, D. M., T. W. Nolan, and J. Whittington. 2008. The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs (Millwood) 27(3):759–769.

Bodenheimer, T., and C. Sinsky. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine 12(6):573–576.

Brady, K. J. S., M. T. Trockel, C. T. Khan, K. S. Raj, M. L. Murphy, B. Bohman, E. Frank, A. K. Louie, and L. W. Roberts. 2018. What do we mean by physician wellness? A systematic review of its definition and measurement. Academic Psychiatry 42(1):94–108.

Braithwaite, J., K. Churruca, J. C. Long, L. A. Ellis, and J. J. B. M. Herkes. 2018. When complexity science meets implementation science: A theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Medicine 16(1):63.

Budrionis, A., and J. G. Bellika. 2016. The learning healthcare system: Where are we now? A systematic review. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 64:87–92.

Burston, A. S., and A. G. Tuckett. 2013. Moral distress in nursing: Contributing factors, outcomes and interventions. Nursing Ethics 20(3):312–324.

Carayon, P. 2006. Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Applied Ergonomics 37(4):525–535.

Carayon, P. 2009. The balance theory and the work system model… Twenty years later. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 25(5):313–327.

Carayon, P., P. Hancock, N. Leveson, I. Noy, L. Sznelwar, and G. van Hootegem. 2015. Advancing a sociotechnical systems approach to workplace safety—Developing the conceptual framework. Ergonomics 58(4):548–564.

Carayon, P., A. Wooldridge, B.-Z. Hose, M. Salwei, and J. Benneyan. 2018. Challenges and opportunities for improving patient safety through human factors and systems engineering. Health Affairs 37(11):1862–1869.

Cassel, C. K., and R. S. J. J. Saunders. 2014. Engineering a better health care system: A report from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. JAMA 312(8):787–788.

Chari, R., C. C. Chang, S. L. Sauter, E. L. Petrun Sayers, J. L. Cerully, P. Schulte, A. L. Schill, and L. Uscher-Pines. 2018. Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health: A new framework for worker well-being. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 60(7):589–593.

Cook, R., and J. Rasmussen. 2005. “Going solid”: A model of system dynamics and consequences for patient safety. Quality & Safety in Health Care 14(2):130–134.

Dang, D., S. H. Bae, K. A. Karlowicz, and M. T. Kim. 2016. Do clinician disruptive behaviors make an unsafe environment for patients? Journal of Nursing Care Quality 31(2):115–123.

Danna, K., and R. W. Griffin. 1999. Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management 25(3):357–384.

Demerouti, E., A. B. Bakker, F. Nachreiner, and W. B. Schaufeli. 2001. The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 86(3):499–512.

Diener, E. 2000. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist 55(1):34–43.

Diener, E., S. Oishi, and R. E. Lucas. 2015. National accounts of subjective well-being. American Psychologist 70(3):234–242.

Doble, S. E., and J. C. Santha. 2008. Occupational well-being: Rethinking occupational therapy outcomes. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 75(3):184–190.

Dul, J., R. Bruder, P. Buckle, P. Carayon, P. Falzon, W. S. Marras, J. R. Wilson, and B. van der Doelen. 2012. A strategy for human factors/ergonomics: Developing the discipline and profession. Ergonomics 55(4):377–395.

Egener, B. E., D. J. Mason, W. J. McDonald, S. Okun, M. E. Gaines, D. A. Fleming, B. M. Rosof, D. Gullen, and M. L. Andresen. 2017. The Charter on Professionalism for Health Care Organizations. Academic Medicine 92(8):1091–1099.

Epstein, E. G., P. B. Whitehead, C. Prompahakul, L. R. Thacker, and A. B. Hamric. 2019. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: The measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empirical Bioethics 10(2):113–124.

Erickson, S. M., B. Rockwern, M. Koltov, and R. M. McLean. 2017. Putting patients first by reducing administrative tasks in health care: A position paper of the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine 166(9):659–661.

Erwin, K., and J. A. Krishnan. 2016. Redesigning healthcare to fit with people. BMJ 354:i4536.

Gander, F., R. T. Proyer, and W. Ruch. 2016. Positive psychology interventions addressing pleasure, engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment increase wellbeing and ameliorate depressive symptoms: A randomized, placebo-controlled online study. Frontiers in Psychology 7:686.

Grossman, R., and E. Salas. 2011. The transfer of training: What really matters. International Journal of Training and Development 15(2):103–120.

Hargraves, I., A. LeBlanc, N. D. Shah, and V. M. Montori. 2016. Shared decision making: The need for patient–clinician conversation, not just information. Health Affairs (Millwood) 35(4):627–629.

Harrison, M. I., R. Koppel, and S. Bar-Lev. 2007. Unintended consequences of information technologies in health care—An interactive sociotechnical analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 14(5):542–549.

Harte, R., L. Glynn, A. Rodríguez-Molinero, P. M. Baker, T. Scharf, L. R. Quinlan, and G. ÓLaighin. 2017. A human-centered design methodology to enhance the usability, human factors, and user experience of connected health systems: A three-phase methodology. JMIR Human Factors 4(1):e8.

Hickson, G. B., J. W. Pichert, L. E. Webb, and S. G. Gabbe. 2007. A complementary approach to promoting professionalism: Identifying, measuring, and addressing unprofessional behaviors. Academic Medicine 82(11):1040–1048.

Hiler, C. A., R. L. Hickman, Jr., A. P. Reimer, and K. Wilson. 2018. Predictors of moral distress in a U.S. sample of critical care nurses. American Journal of Critical Care 27(1):59–66.

Hundt, A. S. 2012. Organizational learning in health care. In P. Carayon (ed.), Handbook of human factors and ergonomics in health care and patient safety, 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group. Pp. 97–108.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2000. To err is human: Buliding a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2007. The learning healthcare system: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012a. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012b. Building a resilient workforce: Opportunities for the Department of Homeland Security: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

ISO (International Organization for Standardization). 2010. ISO 9241-210: Ergonomics of human–system interaction, part 210: Human-centred design for interactive systems. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization.

Karim, S., and M. Duchcherer. 2014. Intimidation and harassment in residency: A review of the literature and results of the 2012 Canadian Association of Interns and Residents national survey. Canadian Medical Education Journal 5(1):e50–e57.

Kleiner, B. M. 2007. Sociotechnical system design in health care. In P. Carayon (ed.), Handbook of human factors and ergonomics in health care and patient safety. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Pp. 79–94.

Kleiner, B. M. 2008. Macroergonomics: Work system analysis and design. Human Factors 50(3):461–467.

Lamontagne, A. D., T. Keegel, A. M. Louie, A. Ostry, and P. A. Landsbergis. 2007. A systematic review of the job-stress intervention evaluation literature, 1990–2005. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 13(3):268–280.

Luthar, S. S., D. Cicchetti, and B. Becker. 2000. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development 71(3):543–562.

Martinez, W., L. S. Lehmann, E. J. Thomas, J. M. Etchegaray, J. T. Shelburne, G. B. Hickson, D. W. Brady, A. M. Schleyer, J. A. Best, N. B. May, and S. K. Bell. 2017. Speaking up about traditional and professionalism-related patient safety threats: A national survey of interns and residents. BMJ Quality & Safety 26(11):869–880.

Maslach, C., and M. P. Leiter. 2017. New insights into burnout and health care: Strategies for improving civility and alleviating burnout. Medical Teacher 39(2):160–163.

Maslach, C., S. Jackson, and M. Leiter. 1996. Maslach Burnout Inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: CPP, Inc.

Melnick, E. R., S. M. Powsner, and T. D. Shanafelt. 2017. In reply—Defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Paper read at Mayo Clinic Proceedings. October 18, 2018. Rochester, MN.

Mohr, J. J., and P. B. Batalden. 2002. Improving safety on the front lines: The role of clinical microsystems. Quality and Safety in Health Care 11(1):45–50.

Montori, V. M., M. Kunneman, and J. P. Brito. 2017. Shared decision making and improving health care: The answer is not in shared decision making and improving health care. JAMA 318(7):617–618.

Moss, M., V. S. Good, D. Gozal, R. Kleinpell, and C. N. Sessler. 2016. An official Critical Care Societies Collaborative statement—Burnout syndrome in critical care health-care professionals: A call for action. Chest 150(1):17–26.

NAE and IOM (National Academy of Engineering and Institute of Medicine). 2005. Building a better delivery system: A new engineering/health care partnership. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2015. Improving diagnosis in health care: Improving health care worldwide. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2018. Crossing the global quality chasm. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nelson, E. C., P. B. Batalden, T. P. Huber, J. J. Mohr, M. M. Godfrey, L. A. Headrick, and J. H. Wasson. 2002. Microsystems in health care: Part 1. Learning from high-performing frontline clinical units. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement 28(9):472–493.

NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health). 2019. What is total worker health? https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/totalhealth.html (accessed February 24, 2019).

Oshima Lee, E., and E. J. Emanuel. 2013. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. New England Journal of Medicine 368(1):6–8.

Palamara, K., M. Linzer, and T. D. Shanafelt. 2018. Addressing uncertainty in burnout assessment. Academic Medicine 93(4):518.

Parsa-Parsi, R. W. 2017. The revised Declaration of Geneva: The modern-day physician’s pledge. JAMA 318(20):1971–1972.

Pasmore, W. A. 1988. Designing effective organizations: The sociotechnical systems perspective. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

PCAST (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology). 2014. Better health care and lower costs: Accelerating improvement through systems engineering. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/systems_engineering_and_healthcare.pdf (accessed July 10, 2019).

Plsek, P. E., and T. Greenhalgh. 2001. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 323(7313):625–628.

Pronovost, P., M. M. E. Johns, S. Palmer, R. C. Bono, D. B. Fridsma, A. Gettinger, J. Goldman, W. Johnson, M. Karney, C. Samitt, R. D. Sriram, A. Zenooz, and Y. C. Wang (eds.). 2018. Procuring interoperability: Achieving high-quality, connected, and person-centered care. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

Rasmussen, J. 2000. Human factors in a dynamic information society: Where are we heading? Ergonomics 43(7):869–879.

Rathert, C., D. R. May, and H. S. Chung. 2016. Nurse moral distress: A survey identifying predictors and potential interventions. International Journal of Nursing Studies 53:39–49.

Reddy, S. T., J. A. Iwaz, A. K. Didwania, K. J. O’Leary, R. A. Anderson, H. J. Humphrey, J. M. Farnan, D. B. Wayne, and V. M. Arora. 2012. Participation in unprofessional behaviors among hospitalists: A multicenter study. Journal of Hospital Medicine 7(7):543–550.

Rider, E. A., M. C. Gilligan, L. G. Osterberg, D. K. Litzelman, M. Plews-Ogan, A. B. Weil, D. W. Dunne, J. P. Hafler, N. B. May, A. R. Derse, R. M. Frankel, and W. T. Branch, Jr. 2018. Healthcare at the crossroads: The need to shape an organizational culture of humanistic teaching and practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(7):1092–1099.

Rowland, M. L., S. Naidoo, R. AbdulKadir, R. Moraru, B. Huang, and A. Pau. 2010. Perceptions of intimidation and bullying in dental schools: A multi-national study. International Dental Journal 60(2):106–112.

Rushton, C. H., and M. E. Broome. 2015. Safeguarding the public’s health: Ethical nursing. Hastings Center Reports 45(1):insidebackcover.

Salvagioni, D. A. J., F. N. Melanda, A. E. Mesas, A. D. Gonzalez, F. L. Gabani, and S. M. Andrade. 2017. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLOS ONE [Electronic Resource] 12(10):e0185781.

Sanders, L., and P. J. Stappers. 2013. Convivial toolbox: Generative research for the front end of design. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers.

Schaufeli, W., and A. Bakker. 2010. The conceptualization and measurement of work engagement: A review. In A. B. Bakker and M. P. Leiter (eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research. New York: Psychology Press. Pp. 10–24.

Schaufeli, W. B., M. P. Leiter, and C. Maslach. 2009. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Development International 14(3):204–220.

Shanafelt, T. D., and J. H. Noseworthy. 2017. Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 92(1):129–146.

Siegrist, J. 1996. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1(1):27–41.

Sikka, R., J. M. Morath, and L. Leape. 2015. The quadruple aim: Care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Quality and Safety 24(10):608–610.

Sittig, D. F., and H. Singh. 2010. A new sociotechnical model for studying health information technology in complex adaptive healthcare systems. Quality and Safety in Health Care 19(Suppl 3):i68–i74.

Skeff, K. 2018. A crisis in management: Time for reflection. Presentation to the Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. PowerPoint available at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Quality/SupportingClinicianWellBeing/2018-Nov-27.aspx (accessed July 10, 2019).

Smith, M. J., and P. Carayon. 2001. Balance theory of job design. In International encyclopedia of ergonomics and human factors. London, England: Taylor & Francis.

Smith, M. J., and P. C. Sainfort. 1989. A balance theory of job design for stress reduction. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 4(1):67–79.

Szanton, S. L., and J. M. Gill. 2010. Facilitating resilience using a society-to-cells framework: A theory of nursing essentials applied to research and practice. Advances in Nursing Science 33(4):329–343.

Trist, E. 1981. The evolution of socio-technical systems: A conceptual framework and an action research program. Toronto: Ontario Quality of Life Working Centre.

Waterson, P. 2009. A critical review of the systems approach within patient safety research. Ergonomics 52(10):1185–1195.

Waterson, P. 2014. Health information technology and sociotechnical systems: A progress report on recent developments within the UK National Health Service (NHS). Applied Ergonomics 45(2):150–161.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2006. Constitution of the World Health Organization, 45th edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2019. QD85: Burn-out. http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281 (accessed June 5, 2019).

Wilson, J. R. 2014. Fundamentals of systems ergonomics/human factors. Applied Ergonomics 45(1):5–13.

This page intentionally left blank.