The first session of the workshop, moderated by Megan Nechanicky, nutrition manager for General Mills Canada, provided a grounding in the discipline of communications and an overview of effective communication strategies. Two speaker presentations were followed by a panel discussion that included viewpoints from two additional experts.

A COMMUNICATIONS AGENCY PERSPECTIVE

Adelaide Feuer, executive vice president at Edelman, set the stage by sharing foundational communications concepts based on her experience in a communications, marketing, and public relations agency. Focusing on the broader landscape of communications, she reviewed key definitions, examples of seismic shifts impacting communications, and approaches to strategic communications planning.

In its simplest form, began Feuer, communication includes a sender of information whose goal is to convey a message and a receiver of that information. She remarked that this seemingly straightforward process has grown increasingly more complex as communication channels have proliferated. Receivers filter a large volume of content, she said, because of the excess of information competing for their attention.

Public relations, Feuer continued, is a strategic communication process that builds mutual trust among organizations, communicators, and their publics, according to the Public Relations Society of America. She described three major categories of public relations: organizational communications (such as employee engagement, fundraising, or investor and shareholder relations); consumer-facing brand communications (promotional marketing, such as product launches, event management, and influencer relationship development); and public affairs communications (which include science, research, and policy communications). One-on-one and small-group dialogues fall within all three categories, she noted, but are less relevant to her presentation’s focus on broader public and mass communications.

Feuer explained that communications are effective only if they produce their intended effects, which may include generating education and awareness; building relationships and trust; and ultimately, changing attitudes and behaviors. These outcomes, she said, are indicators that measure the impact of communications.

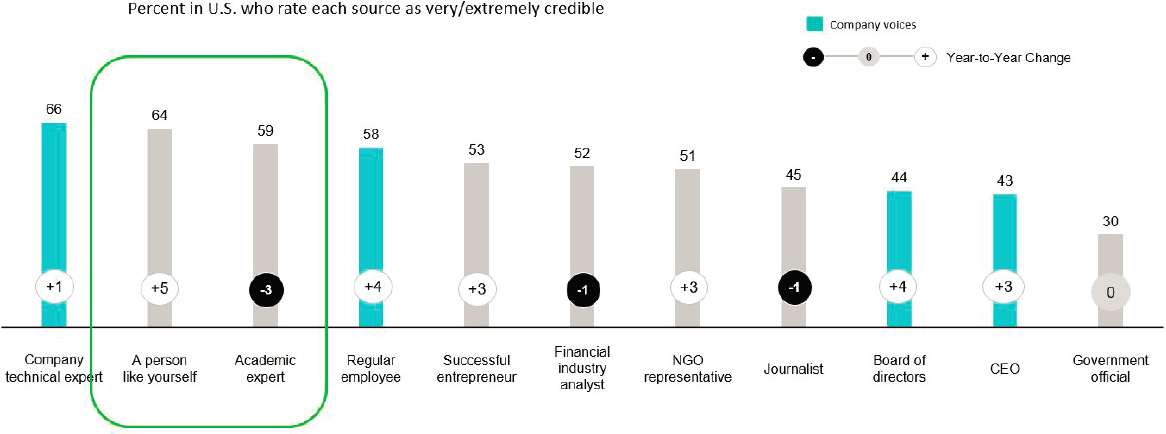

Feuer moved on to discuss macro-level changes impacting communications, with a focus on two key areas. She first addressed the global implosion of trust, reiterating the importance of building trust with communication recipients to increase the likelihood of achieving a communication’s intended outcomes. Feuer referenced Edelman’s annual survey of consumer trust in multiple sectors, reporting that the survey has measured a substantial erosion of trust worldwide, particularly in recent years. According to the survey, she said, consumers now consider peers (i.e., “people like me,” perhaps a blogger or a neighbor) more credible than academic experts, journalists, business leaders, and government officials, for example (see Figure 2-1). Furthermore, she added, their definition of “experts” is subjective.

Feuer next illustrated how consumers are influenced by entities they perceive to be experts. In this model, reputational influencers (e.g., credentialed thought leaders), cultural influencers (e.g., celebrities and famous bloggers), and media influencers simultaneously influence one another and their target audiences. The three sets of influencers reach target audiences both directly and through the audiences’ peers, who, Feuer said, serve as an echo chamber for the influencers’ messages. She suggested that this model has implications for messaging as communicators seek to determine whom their target audiences trust.

Turning to the second macro-level change, Feuer discussed shifts in the consumption of information and content. She cited statistics concerning collective actions that occur every 60 seconds on the Internet, such as 70,000 hours of Netflix watched and nearly 10,000 pins placed via Pinterest, as examples of the staggering volume of content that flows through present-day communication channels. She reported the estimate of one source that people are presented up to 5,000 messages per day, many of which come from social media (Excelacom, 2016). According to another source, she continued, 51 percent of adults globally get news from social media, and 53 percent get news using a smartphone (Newman et al., 2016). This means that social media algorithms dictate what people see, she explained, which is based not on what they choose but on what others in their social networks are viewing. More recently, she added, occurrences of fake news and privacy concerns have contributed to decreased trust in search engines and social media platforms compared with traditional media sources, such as journalists, according to Edelman’s survey (Edelman, 2018).

Lastly, Feuer outlined an approach to communication planning that begins with clarifying objectives, followed by developing a research-informed

NOTE: Question asked of half of the sample, general U.S. population: “In general, when forming an opinion of a company, if you heard information about a company from each person, how credible would the information be—extremely credible, very credible, somewhat credible, or not credible at all.”

SOURCES: Presented by Adelaide Feuer, September 16, 2019. Copyright 2019. Adapted from 2019 Edelman Trust Barometer. General Population, U.S. Used with permission from Edelman.

messaging strategy and narrative that are distributed and amplified using selected messengers (media, influencers, and/or organizations) and optimized platforms (social media applications, search engines, and content aggregators known as curators). She explained that success is measured by quantifying how many people were reached and qualifying who they were, as well as assessing shifts in those people’s attitudes and behaviors. In closing, Feuer emphasized that simplicity of messages is key, acknowledging that much planning goes into crafting simple yet effective messages.

THE COMMUNICATIONS REVOLUTION AND EQUITY: IMPLICATIONS FOR OBESITY-RELATED COMMUNICATIONS

Kasisomayajula “Vish” Viswanath, Lee Kum Kee Professor of Health Communication in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and in the McGraw-Patterson Center for Population Sciences at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, presented five takeaways for obesity communications in light of the 21st century’s revolution in information and communication technologies.

The first takeaway, Viswanath began, is the proliferation of platforms and (mis)information. Society’s exposure to and consumption of information are staggering, he declared, and this situation is made more complex by what he termed a “marketization of (mis)information” that has resulted from the ability for anyone to produce and share information easily, facilitated by a networked environment. He cited one estimate that more than 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are created each day, and another indicating that the daily amount of data produced would increase 10-fold between 2013 and 2020 (Ahmad, 2018). The challenge, Viswanath proposed, is that this deluge of information circulates with little gatekeeping. Journalists once served as important gatekeepers, he pointed out, but he asserted that this is no longer the case because of the proliferation of information delivery platforms and the shift in how people get news and information.

The second takeaway, Viswanath continued, is that the production of science and health information is not the realm of scientists alone. Although private labs generate scientific information, he said, a host of other actors and stakeholders—including mass media, the private sector, activist groups, and health systems—control its distribution and interpretation. Health and science professionals underestimate the private sector’s “oppositional communications,” he suggested, referencing industry’s tactics for marketing tobacco and sugar-sweetened beverages as examples. According to Viswanath, these communications influence perceptions of risk, promote social norms and risk behaviors, and drown out accurate scientific information. He illustrated health communicators’ challenges in competing with private-sector messages by pointing to public data listing

annual marketing budgets of nearly $1 billion or more for three prominent brands that sell tobacco products, sugary beverages, and fast food (McCloud et al., 2017).

Third, Viswanath stressed that information does not equal communication. One reason that people may have challenges interpreting and acting on information, he suggested, is that they perceive information to be contradictory, an example being conflicting headlines about the healthfulness of a given food. Science works cumulatively, he pointed out, but people do not necessarily understand its iterative nature. Viswanath cited as another challenge that people may not recognize false information and may become confused if the information does not align with their current understanding. In addition, people have an inaccurate understanding of disease etiology, he noted, and they underestimate the impact of lifestyle behaviors on disease outcomes. He touched on the related topic of social media and the spiral of amplification, which he described as information that originates in one corner of social media, acquires legitimacy, and spirals out across social networks (NCI, 2006).

Fourth, Viswanath declared that how something is said is as important as what is said. He explained that certain features, formats, or structures of messages interact with individual attributes of the audience and influence how they process information. Framing is critical when constructing messages, he observed, because it affects the extent to which the broader context of the message is represented. Viswanath shared the example of a weight-loss contest winner’s plan to reduce obesity in her hometown, explaining that news coverage of the story failed to mention that she had received extensive professional and social support in her weight-loss journey. Such support would not be available to the town’s participants, he pointed out, which he said was an important detail that helps provide the full picture. Viswanath also referenced an example of framing that contributed to the loss of a “winnable battle” related to a policy limiting the size of a glass of sugar-sweetened beverage one can buy in New York City, where opponents used a “nanny state” frame to persuade citizens that the policy proposed by the city’s government was an overreach.

Fifth, inequalities exist in communications as they do in health, Viswanath stated, elaborating that the distribution of communications resources differs among social groups. As an example, he reported that people of higher socioeconomic status (SES) and in urban areas have better access to information compared with people of lower SES and in rural areas, respectively (Viswanath et al., 2012). The concept of intersectionality is important, he noted, referring to overlapping social categorizations describing an individual or a group, such as being both African American and low income, which creates interdependent systems of disadvantage (Kennedy and Hefferon, 2019). Internet access and cellphone ownership are associated

with income, he continued, but even among the relatively large proportion of the population that uses these resources, SES influences how health information is processed and used (Pew Research Center, 2014; Zickuhr and Smith, 2012). Lower SES is associated with differential allocation of attention to information because of the cognitive overload from pressing demands for resources and services, which Viswanath termed “daily hassles” (Shah et al., 2012). Furthermore, he added, people have difficulty using tablets, and sometimes lose cellphone connections. Communication inequalities are neither trivial nor natural, he asserted, suggesting that institutional solutions could help design systems to bridge them. Finally, he identified as another challenge that information communication technologies are outpacing regulation.

PANEL DISCUSSION

A panel discussion following the presentations by Feuer and Viswanath opened with remarks from Suzi Gates, communication team lead in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, and Rebecca Puhl, professor of human development and family sciences at the University of Connecticut and deputy director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity.

Gates began by clarifying that in community health, communications refers to the strategic use of marketing principles to advance programmatic objectives. These kinds of communications are integral program components that go beyond pamphlets and brochures, she underscored, and can be used as an intervention to impact norms and advance policy, systems, and environmental changes that facilitate healthy living. Gates highlighted three key lessons learned from her experience working on the VERB™ social marketing campaign to increase physical activity among children aged 9–13: the importance of (1) precisely defining an audience, identifying its values, and recognizing its barriers to healthy lifestyles; (2) clearly specifying objectives for the communication effort; and (3) growing and evolving with the audience as social and communication environments shift.

Gates briefly reviewed several examples of strategic communication efforts in communities nationwide to promote healthy living among various population groups. These include campaigns in New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Denver, Santa Clara (California), and Alaska, which targeted such behaviors as sugar consumption and physical activity while laying the foundation for programmatic work. Gates affirmed that as well-researched, adaptable efforts, these campaigns were instrumental in softening the ground for obesity-related policy and environmental changes. Examples of these efforts are available in the state and community health media center at CDC (2019).

Puhl focused her comments on the role of stigma and discrimination in the current obesity communication environment. Negative attitudes toward people with obesity have long been ingrained in society, she maintained, noting that society’s weight stigma interferes with the ability to communicate effectively about obesity.

Puhl summarized findings from her team’s research on the role of stigma in obesity communications. She reported that, according to several national experimental studies, when the public is exposed to stigmatizing messages in public health campaigns targeting obesity, the result is less motivation, lower intent, and less self-confidence to change health behaviors. In contrast, she said, when nonstigmatizing messages are used, the result is increased motivation to change behavior, especially when the messages focus on specific health behavior changes rather than on weight. Therefore, Puhl argued, a key question is how to disseminate important messages without stigmatizing or shaming recipients.

In news media communications, Puhl continued, obesity is often described as an issue of personal responsibility to be solved at the individual level. That narrative is overly simplistic, she cautioned, adding that it is as problematic as news stories’ visual depictions of people with obesity. She cited content analyses that have found that about two-thirds of news reports about obesity that include visual depictions of children and adults with obesity portray them in a stigmatizing manner. According to Puhl, those depictions sometimes send more powerful messages than the words they accompany. She elaborated that public attitudes worsen and bias increases in response to such images—even if the narrative’s written content is neutral—but that attitudes improve when nonstigmatizing images are used. Research on obesity communications in social, entertainment, and other forms of media has produced similar findings that indicate a focus on individual responsibility, ridicule, and stereotypes, Puhl added, declaring that a clear disconnect exists between what scientists and health professionals know about the multifactorial causes of obesity and what society communicates about obesity.

Lastly, Puhl called for improving obesity communications in health care settings. Health care providers receive little training in communicating with patients about weight, she said, and weight stigma can create harmful implications for those conversations. Puhl advocated for language that is sensitive, supportive, and empowering rather than stigmatizing or shaming, and referenced a 2017 American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement on the topic (Pont et al., 2017).

The evidence warrants a shift in the current obesity communications environment, Puhl urged, away from the overly simplistic narrative that emphasizes obesity as an issue of personal responsibility and deserving of blame. Fundamentally, she said in closing, it is important

that communications be respectful and inclusive of people of diverse backgrounds who are affected by obesity.

Following Puhl’s remarks, Nechanicky posed questions to the four panelists. She first asked for their perspectives on whom the senders of obesity communications have been, what has been heard, and what has been acted upon. Viswanath began by proposing that two sides of stakeholders are communicating about obesity: those in the business of promoting health and risk reduction, and those in the business of promoting risk. Gates suggested that misinformation far outweighs accurate information, and the challenge is to break through the clutter. She proposed that narratives hold an opportunity for people to hear from others like themselves. Gates also warned against normalizing unhealthy weight and highlighted the importance of strong messages to normalize healthy weight. Puhl indicated that people hear about obesity as an issue they need to deal with on their own. She appealed for communications that address the complexities of obesity and the importance of broadening the focus to social and environmental implications. She added that messages that are inclusive of different demographic groups and that describe the benefits of nutrition and physical activity beyond weight control would also be helpful.

Alluding to the importance of simple messages, Nechanicky next asked how to break down the complexities of obesity into understandable, actionable terms. Feuer proposed that simplicity is best suited for audience-specific and objective-specific communications. However, oversimplification at the level of mass communications and campaigns is likely not going to be very effective, she asserted, alluding to Gates’s point about defining target audiences precisely and tailoring messages accordingly. Viswanath maintained that people are quite thoughtful, recounting focus groups with women of lower SES who demonstrated savvy in navigating trade-offs related to challenges of paying monthly bills. He argued that communications fail to account for such sophistication and that messages often do not consider the obesogenic contexts in which they are received. He called for providing more support for people to act on messages, asserting that they are capable of thinking deeply about how to navigate their situational challenges. Gates agreed and cautioned against overstressing barriers, which she suggested could lead to fatalism. She appealed for real-life narratives that model how people overcome both individual- and environment-related challenges. Puhl reported that when people attribute obesity to complex, societal-level factors more than to individual contributors, they are more likely to support social policies that address those broader factors. The effectiveness of either simple or sophisticated messages will be limited, she predicted, unless social and environmental policies and approaches are applied simultaneously. Puhl agreed that individual narratives can motivate and inspire, but cautioned that they can also individualize the problem. She

encouraged the use of narratives to illustrate a comprehensive picture that addresses the multiple contributors to obesity. Viswanath concurred, adding that individual narratives can motivate people who already know what to do but face environmental and social constraints.

When asked to discuss the VERB™ campaign’s strategy for identifying target audiences and messages, Gates replied that its national messages were specifically targeted to different ethnic audiences and even further segmented by locality. Although costly, she said, this strategy was effective. Gates maintained that once objectives and key audiences have been determined at the national level, people in communities and states can implement campaigns and carry the momentum forward.

Responding to a question about effective contexts for people-first language, Puhl said that the concept of identifying a person first rather than labeling the person by his or her condition has existed for a long time in the realm of stigmatized conditions and illnesses, and has been adopted in the obesity and medical fields only in recent years. She shared her belief that people-first language is a positive first step and promotes patient-centered care, and referenced research examining preferred language for discussing obesity and body weight. Across studies, she said, people want neutral words, such as “unhealthy weight” or “high BMI [body mass index]” instead of such words as “fat” or “obese” used to discuss their weight. Research on this topic is lacking in terms of participant diversity, she noted, and much remains unknown, including the impact of different language on quality of care. Puhl pointed to the lack of a universally acceptable term or phrase, and said that in the meantime, it is best to respect individual diversity in preferences. She acknowledged the challenge of pleasing everyone when messages are disseminated to large audiences, but maintained that the use of preferred language is more easily practiced in provider–patient interactions. She encouraged providers to ask patients, “As we talk about your weight today, what kinds of words or language would you feel most comfortable using?” Data suggest that patients are more likely to avoid future health care if physicians use stigmatizing language, she added, emphasizing that how obesity is discussed is as important as what is said.

DISCUSSION

Following the panel discussion, panelists addressed participants’ questions about normalizing unhealthy weight, differences between communication and information campaigns, avoiding unintended consequences of messages, and framing obesity as a disease.

Normalizing Unhealthy Weight

A participant referenced a public controversy over a popular athletic apparel company’s use of large mannequins to model fitness clothes. The company was accused of normalizing unhealthy body weight and was also defended by advocates for people with obesity, who applauded the accessibility of fitness clothes for larger body sizes. Puhl acknowledged that higher body weight is the norm in the United States, and advocated for representing a diversity of body sizes in communications about obesity or any other topic. It is beneficial for people with high body weight to have role models of diverse sizes who engage in healthy behaviors, she pointed out, and in the case of this example, to have access to clothing for participating in physical activities.

Communication Versus Information Campaigns

A participant asked how to distinguish communication campaigns from information campaigns, and wondered what makes a strong communication campaign. Feuer shared an agency perspective on communication campaigns, describing them as efforts that start with clear objectives; tailor messages and channels to the target audience; and measure outcomes, collecting feedback and making corresponding adjustments along the way. Viswanath referenced community-based campaigns that engage end users to co-design intervention from the beginning, noting that this involvement informs the choice of language, channels, and platforms. He shared an example of a community that informed researchers of its dislike for the word “disparities.”

Reviews of strategic communication campaigns indicate that successful campaigns attempt to change environments in which the targeted individual behaviors occur, Viswanath explained, because campaigns are less likely to succeed without social and environmental supports for behavior modification. Feuer and Gates reiterated the importance of choosing words and phrases that resonate with specific audiences, noting that broader health topics may be of greater interest than obesity to certain groups.

Avoiding Unintended Consequences of Messages

A participant observed that the best messaging approach for one population may be counterproductive for another population, and wondered how to navigate those situations and avoid unintended consequences in a complex messaging environment with an increasingly diverse population. Puhl stressed the importance of soliciting the right language from target audiences, referencing her work with adolescents that found gender

differences in preferred language for discussing weight. Gates said that some population groups, such as parents, comprise multiple ethnicities yet share certain universal values to which communicators can appeal. This may be a safer approach, she proposed, than using targeted messages that resonate with some people but repel others. Viswanath observed that most evaluations of communication campaigns do not measure unintended effects, but those that do sometimes produce surprising or unpleasant results. He also appealed for national surveys to include large enough samples of diverse groups to permit subgroup analysis. If surveys were designed to account for the diversity that exists, he insisted, more confident inferences could be drawn about how to communicate to those groups. In the same vein, he called for communication campaigns to be conducted with diverse audiences.

Framing Obesity as a Disease

Referencing the American Medical Association’s (AMA’s) 2013 declaration that obesity is a disease, a participant observed that although correct from a scientific standpoint, this framing has led to unintended consequences. He asked panelists how to facilitate common consumer understanding of the concept and implications of obesity as a disease. Puhl shared results of survey research that followed AMA’s announcement, reporting that about one-third of respondents expected the disease classification to remove shame and personal blaming and spotlight the contributions of complex social and environmental drivers of obesity. Another one-third expected the announcement to increase stigma because of obesity’s association with disease status. Framing obesity as a disease is a complex message, she acknowledged, and added that many people surveyed were not even aware of AMA’s announcement. According to Gates, a good outcome of the announcement was increased understanding (observed through focus groups) of the complex origins of obesity. She urged that communication plans for such major announcements as AMA’s include consideration of strategies for delivering the message to different audiences. Viswanath proposed that organizations assume responsibility for understanding the impact of their major announcements, given that messages affect different groups of people differently.

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW

Following the first session’s overview of communications, Sylvia Rowe, president of SR Strategy, framed the remainder of the workshop. To align communication approaches with goals, she said, it is important to consider who is the target of the communication, what is the purpose of

the communication, and what message is being communicated. Rowe informed participants that the rest of the workshop would examine these considerations.

The workshop planning committee decided to focus on a specific and tangible topic, Rowe said, and chose communications of obesity solutions. This topic is central to the roundtable’s focus on obesity solutions, she explained, and its discussion could help identify opportunities to move away from the challenges involved and toward strategies that can make a positive difference. She identified three key audiences for communications of obesity solutions: the broader publics; decision makers such as teachers, parents, community leaders, and health professionals; and policy makers. She explained that session 2 would explore the complexity of communicating obesity solutions and address where to start with those three audiences, while sessions 3 and 4 would turn to practical approaches for communicating with impact, including model successes, lessons learned, gaps, and evaluation metrics; unique challenges for different audiences; and the refinement of objectives and development of high-impact messages.

This page intentionally left blank.