Proceedings of a Workshop

INTRODUCTION1

Millions of people in the United States face the challenge of living with serious illnesses, such as heart and lung disease, cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. Additionally, many suffer from multiple chronic conditions. According to estimates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,2 approximately 40 million people have limitations in their usual daily activities as a consequence of serious illness. Providing care to the large and growing portion of the population with serious illness is further complicated by challenges related to inequitable access and disparities in care. These disparities are partly due to, or exacerbated by, factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, geography, socioeconomic status, or insurance status.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness hosted a public

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

2 For more information, see https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_259.pdf (accessed July 17, 2019).

workshop, Improving Access to and Equity of Care for People with Serious Illness, with the key objective of exploring the barriers that impede access to care and affect health equity for people with serious illness. On April 4, 2019, in Washington, DC, the workshop highlighted different models of care delivery that serve various communities and vulnerable populations, with the aim of addressing opportunities to minimize barriers, inform policy initiatives, and determine areas for further research in improving access to and equity of care for people with serious illness.

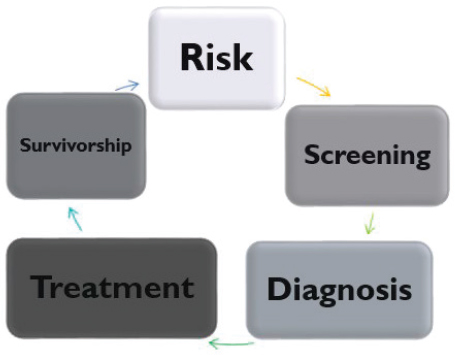

The workshop sessions were developed using the social ecological model (see Figure 1) as a conceptual framework. The social ecological model presents opportunities to understand how stakeholders at various levels throughout the system—including individual, organizational, community, and policy levels—might contribute to advancing access and equity in the care of people with serious illness.

With the social ecological model as a framework:

- The workshop’s first session provided a foundational overview of the challenges and opportunities related to improving access and advancing health equity for people of all ages living with serious illness and explored the role of trauma-informed care.

- The second session illuminated the opportunities for improving access to and equity of care at the community and organizational levels.

- The third session explored access and equity from the perspective of patients, families, and clinicians.

- The fourth session examined policy options to expand access to health care and advance health equity.

- The workshop concluded with a solutions-focused, moderated discussion of practical next steps to advance health equity and expand access to care for people of all ages living with all stages of serious illness.

Workshop planning committee co-chair Peggy Maguire, president of Cambia Health Foundation, opened the workshop with an overview of the day. In her opinion, disparities in serious illness care are best viewed as social justice issues. According to Maguire, “How we advocate for people with serious illness and their caregivers is a measure of who we are as a country.” Therefore, “it requires us to look at these issues through a health equity lens,” which “means listening to people that we serve, acknowledging their experiences, and then challenging ourselves to take a hard look at our own

NOTE: AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

SOURCES: As presented by Darci Graves, April 4, 2019; CDC, 2011.

institutions and organizations and how they may perpetuate bias,” she said. Maguire concluded her introductory remarks by sharing her hope that the workshop would challenge workshop attendees’ thinking about access to and equity of care for people with serious illness. She also hoped the workshop discussions would inspire the attendees to take action to change the status quo so that all people with serious illness have access to high-quality care in the setting that is most appropriate for them.

Darci Graves, workshop planning committee co-chair and special assistant to the director of the Office of Minority Health at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), reminded the workshop attendees that equity is one of the six domains of health care quality (safe, effective, timely, equitable, patient-centered, and efficient care) identified by the Institute of Medicine3 (IOM, 2001). Graves commented that equity is often afforded less attention than other domains: “So, every time we talk about equity today, I want to remind folks that we are talking about a fundamental part of quality.” She emphasized that equity is not “extra” or “someone else’s department.” She asserted that “equity is a fundamental part of quality, and we are all here to improve health care quality.” At the same time, no single individual, organization, or policy is going to fix the challenges regarding access and equity in serious illness care. “It is going to take all of us working collaboratively,” stated Graves.

The Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness serves to convene stakeholders from government, academia, industry, professional associations, nonprofit advocacy groups, and philanthropies. Inspired by and expanding on the work of the IOM’s Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life consensus study report (IOM, 2015), the roundtable aims to foster ongoing dialogue about crucial policy and research issues to accelerate and sustain progress in care for people of all ages with serious illness through workshops and other activities.

This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the presentations and discussions from the public workshop Improving Access to and Equity of Care for People with Serious Illness. The speakers, panelists, and workshop participants presented a broad range of views and ideas, and Box 1 provides

___________________

3 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM name is used to refer to publications issued prior to July 2015.

a summary of individual participants’ suggestions for potential actions. Appendixes A and B contain the workshop’s Statement of Task and workshop agenda, respectively. The workshop speakers’ presentations have been archived online (as PDF and audio files).4

UNDERSTANDING THE CONTEXT FOR IMPROVING ACCESS TO AND EQUITY OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH SERIOUS ILLNESS

The first session provided context for exploring the broader issues of expanding access to care and advancing health equity. It also served to launch the workshop from the individual level of the social ecological model by grounding the discussions in the real-world experience of a person facing the challenges of serious illness.

A Patient’s Perspective on Access to and Equity of Care for People with Serious Illness

Bridgette Hempstead, president and founder of Cierra Sisters, opened the workshop’s first session with the story of her breast cancer diagnosis in 1996: she was about to turn 35 and went to her physician for a mammogram. She was told that the prevailing guidelines for all women to have a baseline mammogram at age 35 was only for White women because African American women are “not affected by breast cancer.” “You have to remember that in 1996, only White women were celebrating breast cancer survivorship,” said Hempstead. Fortunately, Hempstead insisted on getting a mammogram, and her physician called on her 35th birthday to inform her that her mammogram indicated that she had breast cancer. Based on her experience, Hempstead founded Cierra Sisters,5 an advocacy organization with a mission to “break the cycle of fear and increase knowledge concerning breast cancer in the African American and underserved communities” (Cierra Sisters, 2019). “If you have knowledge, you have the power to fight against the effects of breast cancer,” said Hempstead.

In 2014, Hempstead was once again diagnosed with cancer, which had metastasized to her lungs and liver. Unfortunately, she said, it did not

___________________

4 For more information, see http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/HealthServices/QualityCareforSeriousIllnessRoundtable/2019-APR-04.aspx (accessed May 23, 2019).

5 For more information, see http://www.cierrasisters.org (accessed May 21, 2019).

seem like the health care system had improved much for African American women in the 18 years since her first cancer diagnosis. She explained that when she was seen in the hospital emergency department, despite the fact that she was having severe trouble breathing, she was passed from one doctor at the end of a shift to another. In the process, she received unclear orders on what to do next. The first doctor told her that she needed to call her physician the next day to follow up on something unusual on her chest X-ray. In contrast, the second doctor gave her a bottle of cough medicine and told her to come back in a few weeks if her condition did not improve. Fortunately, Hempstead took the first doctor’s advice; her physician reviewed her health record and discovered that the second emergency department doctor had erased the first doctor’s order, even though the X-rays showed an anomaly that warranted further tests.

In delivering the diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer, Hempstead’s oncologist told her that she would not live longer than 1 year and would never sing again, but 6 months later, she sang the national anthem at a Seattle Seahawks football game. By that time, she knew enough about cancer and possible treatments that she was shocked when her oncologist did not offer her the treatment options typically presented to White women; additionally, her oncologist did not refer her for participation in a clinical trial.

Hempstead’s response to her unequal treatment by the medical care system was to launch Community Empowerment Partners (CEPs), a program designed to educate women in the African American community about prevention and early detection and provide the skills to navigate the complex health care system. Initially, 14 women recruited from Cierra Sisters received training; these women have since educated more than 120 others within their social networks. Collaborating with investigators at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Illinois at Chicago, Hempstead and colleague Cynthia Green conducted pre- and post-training tests and found that it is feasible to train peer educators to increase knowledge among community members (Hempstead et al., 2018).

Despite the efforts of Cierra Sisters and other advocacy organizations, the health care system is still “broken” for the African American community, in Hempstead’s view. “We have to continue to scream at the top of our lungs to make a difference in our community,” said Hempstead, “and it should not be like this.” Cierra Sisters has now expanded to address inequities in treatment for African American women with endometrial cancer. The resulting Endometrial Cancer Action Network for African-Americans (ECANA) is using the same CEPs model to educate and empower women

in the community. In March 2019, ECANA held a national workshop at which representatives from 11 states were trained to be educators in their communities. The goal of all of these efforts, noted Hempstead, is for African American women to receive the same care as White women.

Lessons Learned for Achieving Health Equity Across Diverse Populations

Marshall Chin, the Richard Parrillo Family Professor of Health Care Ethics at The University of Chicago, began his presentation with five lessons he has learned from more than 20 years of work on multi-level interventions to achieve health equity:

- There is no magic bullet solution to achieving equity in health care.

- Achieving health equity is a process.

- Addressing the social determinants of health is essential.

- Addressing payments and incentives is essential.

- Equity must be framed as a moral and social justice issue.

The ultimate goal of work in this area, said Chin, should be to improve the national statistics as listed in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Healthcare Quality and Disparities reports.6 “As opposed to a frame of purely improving equity in your own organization, I am talking [about] how do we improve equity nationally, so we move the national numbers,” he stressed.

Chin explained that the first lesson grew out of work conducted around 2005 that documented many causes of health disparities while identifying a few overarching solutions for those causes. As the current director of a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) health equity program, Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change,7 his belief was that the program would fund grantees, develop solutions, and disseminate them widely. It did not take him long, however, to realize that approach was not going to work due to the importance of context. “You might have a wonderful program for African Americans in Birmingham, Alabama, but that may or may not work for African Americans on the South Side of Chicago,” said Chin.

___________________

6 For more information, see https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/index.html (accessed May 1, 2019).

7 For more information, see https://www.solvingdisparities.org (accessed June 26, 2019).

He added that the same holds true for different health care organizations operating in different political and financial contexts. Every health care system, for example, has a different mix of fee-for-service and value-based managed care. An organization’s history and the ways in which disparities developed over time can also influence what interventions will work best, according to Chin.

The bottom line, said Chin, is that every organization has to work through its own solutions. He noted that there is still value in having a selection of evidence-based solutions that organizations can use as a starting point to tailor their own interventions. Chin pointed out that his review of more than 400 papers on interventions to address health care disparities did not find many common themes in terms of what works to reduce inequities. However, he was able to identify a few commonalities among effective interventions, including those that were multifactorial; were culturally tailored quality improvement initiatives; had nurse-led, team-based care; integrated family members and community partners; used community health workers; and provided interactive, skill-based training to patients (Chin et al., 2012).

Chin explained there are multiple levels for taking action in both the clinical and policy areas (Chin et al., 2012), and he presented a model for action in which a person lives in the context of the community and its knowledge of health care. For example, Hempstead’s African American community had little awareness about breast cancer issues. When she became a patient, she encountered health care providers who lacked communication skills and knowledge of breast cancer in African American women.

In addressing the second lesson—that achieving equity is a process—Chin detailed the key components as outlined by RWJF’s Advancing Health Equity: Roadmap for Reducing Disparities (see Box 2).8

Chin noted that the third lesson—addressing the social determinants of health—is currently perhaps the most popular issue in the field of health disparities. He explained that most health care organizations are now looking at individual patients, trying to identify their specific needs and referring them to local community-based organizations that can address those needs. Chin’s ideal world would have a communication conduit that sends information from the community-based organizations to the health care system. According to Chin, fewer health systems are addressing the underlying structural drivers of health care disparities, such as the structural racism

___________________

8 For more information, see https://www.solvingdisparities.org/implement-change/roadmap-reduce-disparities (accessed May 1, 2019).

that leads to segregated housing and income inequality. What is needed, Chin asserted, are free, frank, and fearless discussions about structural racism, colonialism, social privilege, and intersectoral partnerships to address those underlying structural drivers. Having such discussions can be difficult, according to Chin, at least in part because power differentials influence the historical narrative and control over resources, thus affecting the way in which health disparity issues are framed.

In Chin’s view, the fourth lesson—efforts to address payment and incentives—and the social determinants of health are the two frontier areas in the health disparities field. Chin pointed out the large gap between the rhetoric about how the United States values health equity as expressed in documents, such as Healthy People 2020, and actual policies that do little to support and incentivize health equity. Instead, he said, the nation needs to explicitly design quality of care and payment policies to achieve health equity. Policies should provide adequate resources and support for such efforts, while also holding the health care system accountable through mandated public monitoring and evaluation.

Chin noted that the National Quality Forum (NQF) published a roadmap for promoting health equity based on what it called the “Four Is”:

- Identify priority disparity areas,

- Implement evidence-based interventions to reduce disparities,

- Invest in health equity performance measures, and

- Incentivize the reductions of health disparities and achievement of health equity (NQF, 2017).

Of the 10 recommendations NQF made to incentivize the reduction of health disparities and achievement of health equity, Chin focused on the importance of accountability, redesigning payment models to support health equity, and tailoring the safety net. Accountability, he said, entails stratifying clinical performance measures by factors such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, disability status, and serious illness.

Turning to the newest iteration of his RWJF-funded project, Chin explained that he and his colleagues are working with three major stakeholders—state Medicaid agencies, Medicaid managed care organizations, and frontline health care organizations—to align their efforts to use payment and care transformation to advance health equity.

Regarding the fifth lesson—to reduce disparities by framing equity as a moral and social justice issue—Chin referred to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s

1966 observation that “of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhuman.” “If you are trying to have other forms of human attainment, whether it’s well-being, employment, education—unless you have your health, you will not be able to get there,” emphasized Chin.

Chin concluded his presentation by stating that leadership matters (Chin, 2014). “It is our professional responsibility as clinicians, administrators, and policy makers to improve the way we deliver care to diverse patients,” he said. “We can do better.”

Disparities in Serious Illness Care for African Americans

Kimberly Johnson, associate professor of medicine and senior fellow in the Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development at the Duke University School of Medicine, began her presentation with the story of her maternal grandmother, Bertha Stokes, who was diagnosed with cervical cancer in the 1950s. Living in a small town in rural Mississippi, Stokes received care at the local hospital and then from a large public hospital in New Orleans. After several months in New Orleans, she was told there was nothing else that could be done for her, so she returned home, where she was largely cared for by her children, including Johnson’s aunt. Johnson’s aunt told Johnson that Stokes experienced a substantial symptom burden in the last months of her life and received little information about what to do or expect.

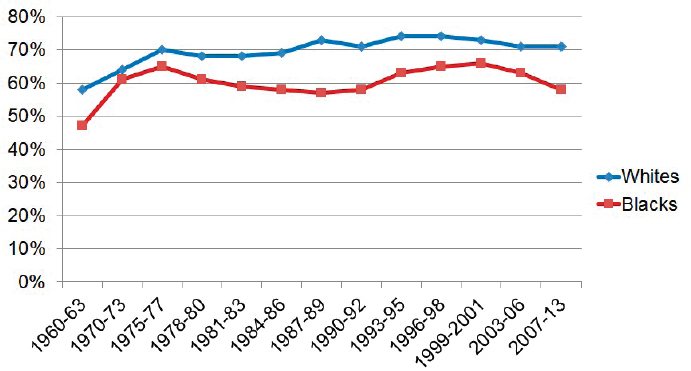

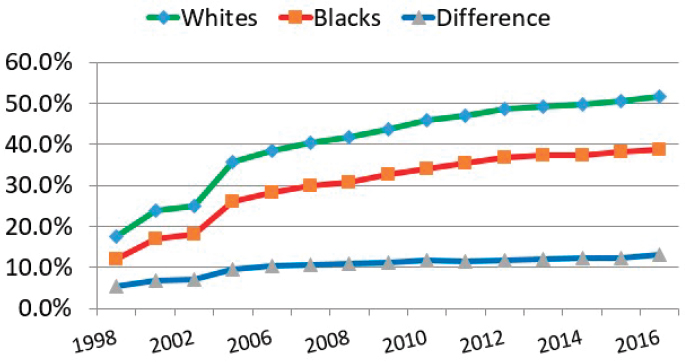

When Johnson’s aunt recounted this story, she asked Johnson two questions. First, with all the medicines we have today, do you think she would have lived longer? Second, even if she could not be cured, do you think she would have lived better? Johnson’s immediate answer was that yes, she might have lived longer, though the 5-year survival rate for cervical and uterine cancer for African American women remains lower than that for White women (see Figure 2). Johnson said the answer to the second question is uncertain because numerous studies have shown that across settings, diagnoses, and age groups, African Americans are less likely than Whites to have pain adequately assessed and treated (Meghani et al., 2012).

In addition, said Johnson, research shows that there are substantial differences in how effectively physicians communicate with patients depending on the patient’s race, with African Americans receiving less information and less support than White patients, particularly in race discordant patient–physician encounters (Cooper et al., 2003; Gordon et al., 2006;

SOURCES: As presented by Kimberly Johnson, April 4, 2019; NCI, 2015.

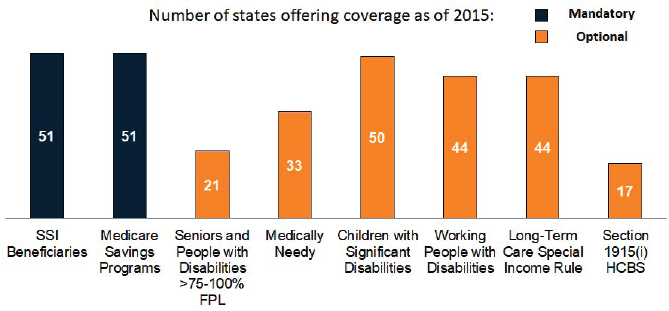

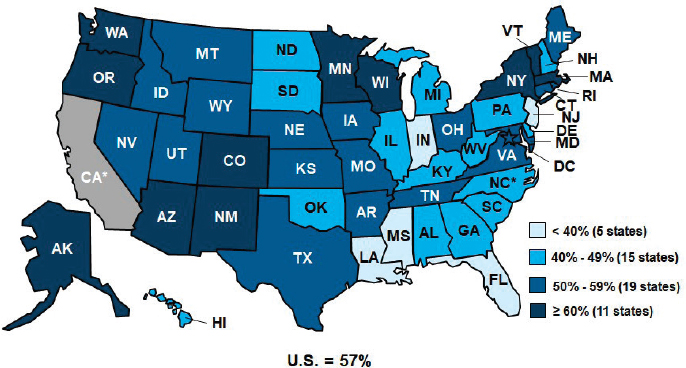

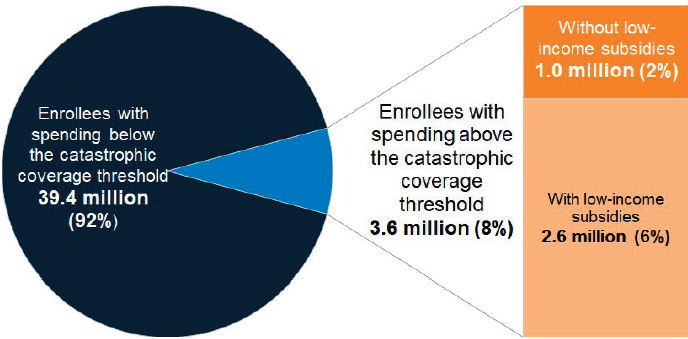

Periyakoil et al., 2015; Welch et al., 2005). According to Johnson, “a Black patient and a White provider [is] the norm in our country since about only 5 percent of physicians are African American.” Family members of seriously ill African American patients who die are more likely to report absent or problematic communication, explained Johnson. African Americans are also less likely to participate either formally or informally in advance care planning (ACP) (Sanders et al., 2016), which means they are less likely to talk about their preferences with providers, and even when they want to, are less likely to complete formal documentation of those preferences (Loggers et al., 2009; Mack et al., 2010). Moreover, African Americans are also less likely than Whites to enroll in hospice at the end of life (see Figure 3), an effect magnified by the fact that African Americans are more likely to suffer from cancer and heart disease, two of the more common conditions among hospice patients (Johnson, 2013).

With regard to palliative care, which did not exist in the 1950s, Johnson said that while more than 60 percent of hospitals with at least 15 beds currently have a palliative care team, the distribution of those programs is uneven across the United States. In Mississippi, for example, only 13 of 45 hospitals, and only 4 of 16 public hospitals, have a palliative care program (CAPC, 2015). This difference is important because the availability and use of palliative care has been shown to reduce disparities in hospice referral, symptom burden, discussion of treatment preferences,

SOURCES: As presented by Kimberly Johnson, April 4, 2019; MedPAC, 2004, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018.

completion of advance directives, and use of pain medication (Sharma et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2015). “Palliative care consultation is one potential intervention to improve disparities,” said Johnson (Rhodes et al., 2007).

Johnson pointed out that ACP discussions may also reduce disparities by improving communication, increasing documentation of preferences, and increasing patient and family satisfaction with the quality of communication and care (IOM, 2015). Johnson explained that she is embarking on a study, funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), to gain clarity on the extent to which ACP can reduce disparities.9 She also noted that hospice use has been shown to reduce some disparities in terms of satisfaction with care, communication, and emotional and spiritual support received (Rhodes et al., 2007).

Johnson explained that a number of barriers still need to be addressed to make access to palliative care, hospice, and ACP more equitable, including a range of patient factors, such as knowledge about these offerings, cultural and personal preferences, spiritual beliefs, and lack of trust in the health care system. Johnson noted that other barriers include provider-related barriers, including poor communication and both explicit and implicit bias, and organizational and system barriers, such as payment

___________________

9 For more information, see https://medicine.duke.edu/medicinenews/kimberly-johnson-get-58-million-pcori-contract (accessed May 28, 2019).

structures, lack of insurance, income differences, and geography (Goepp et al., 2008; Hoffman et al., 2016; Johnson, 2013).

Johnson pointed out that despite these barriers, there are opportunities to improve the care experience and reduce disparities in serious illness care through community education, outreach, and partnership with the people and institutions in the community with whom patients have their daily interactions outside of the health care system. Increased diversity of health care providers and improved cultural competency training can improve trust, interpersonal care, and access, said Johnson, who added that increased diversity among health care teams may improve health outcomes for racial and ethnic minorities (HHS Administration Bureau of Health Professions, 2016). She also noted that including nontraditional workers, such as community health workers, in the health care team can help address the barriers to equitable care (CDC NCCDPHP, 2016).

Finally, Johnson stressed that there is no uniform approach to expanding access and advancing health equity. She noted that one of the strengths of palliative care is that it emphasizes understanding people’s preferences, beliefs, and values as a way to tailor personalized care for each patient.

Trauma-Informed Health Care: A Powerful Tool to Reduce Disparities in Health

“Trauma-informed care10 is a powerful tool to address some of the most daunting challenges in medicine,” said Edward Machtinger, professor of medicine and director of the Center to Advance Trauma-informed Health Care and Women’s HIV Program at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). “It can bring healing to people with serious illnesses, it can increase satisfaction and joy for providers of care, and ultimately, it can be a pathway for us to more effectively address the disparities in health outcomes in our country,” explained Machtinger.

With that introduction to his presentation, Machtinger said his awakening to the impact of trauma on health and behavior came when one of his most beloved patients, a 49-year-old African American woman with HIV named Rose, was murdered by her abusive husband. As is the case when-

___________________

10 Trauma-informed health care is based on the tenet that childhood and adult trauma underline and perpetuate many serious illnesses. For more information, see https://www.capc.org/blog/palliative-pulse-the-palliative-pulse-october-2018-an-interview-with-dr-edward-machtinger-lessons-of-trauma-informed-care (accessed August 20, 2019).

ever a clinic patient died, he and the rest of the clinic’s staff came together for a case conference to mourn Rose and to try to learn some lessons from the circumstances surrounding her death. This time, however, Machtinger also invited representatives from all of the agencies with which Rose had contact and all of the people who knew and loved her. What emerged from the discussions about Rose (and nine other recent patient deaths) was the realization that that the common thread across the 10 different stories was a lifelong history of trauma that led to HIV infection and eventually death. “We realized that while the biomedical focus of HIV care, like so much care for serious illnesses, is incredibly important, it is also profoundly insufficient,” said Machtinger. “We realized then that we needed to transform our clinic to one that addresses trauma.”

When reviewing the research on trauma and engaging in advocacy work to support this transformation, Machtinger explained that he and his colleagues realized the following:

- Most illnesses and behaviors that contribute to health disparities are correlated strongly with individual-, family-, and community-level trauma.

- Trauma continues to be an obstacle to successful treatment of many common illnesses.

- Clinics and environments of care often mirror the trauma experienced by patients and can themselves be traumatizing.

Trauma-informed care integrates these realizations into the standard of care to better address individuals’ needs. To address his first realization, Machtinger explained that trauma is an event, a series of events, or set of circumstances that an individual experiences as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects. These can include physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse; neglect; loss; interpersonal or community violence; and structural violence associated with racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and xenophobia (SAMHSA, 2014). He noted that the impact of trauma on adult health and well-being is well documented, citing the results of the Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)11 study as one example illus-

___________________

11 ACEs include exposure to psychological, physical, or sexual abuse and household dysfunction, including substance abuse, mental illness, and a family member imprisoned.

trating the harms resulting from trauma (Felitti et al., 1998). Research has found that ACEs are strong predictors of the major causes of adult morbidity, mortality, and disability in the United States. For example, individuals reporting 4 or more ACEs had 1.6 times the rate of severe obesity, nearly twice the rate of heart and liver disease, twice the rate of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and stroke, more than 3 times the rate of depression, and 10 times the rate of intravenous drug use compared to individuals reporting no ACEs (CDC, 2019a; Felitti et al., 1998).

Machtinger also referenced a study of residents in urban Philadelphia that examined the effect on health of five adverse community environments—experiencing racism, experiencing bullying, witnessing violence, being in foster care, or living in an unsafe neighborhood (Cronholm et al., 2015; Wade et al., 2016). The study found that individuals who experienced three or more of these community-level ACEs as children were more than twice as likely to smoke cigarettes as an adult or to be depressed, more than three times as likely to have a substance abuse disorder, and more than four times as likely to have a sexually transmitted disease compared to those who have not. Additionally, community-level ACEs are separate and additive from individual- and family-level traumas.

For Machtinger, these statistics shed critical light on those affected by the HIV epidemic and why his clinic’s patients were dying. Specifically, he pointed out the following:

- 69 percent of people newly diagnosed with HIV are African American or Latinx12 (CDC, 2019c).

- 30 percent of African American men who had sex with men were diagnosed with HIV (Rosenberg et al., 2014).

- 50 percent of gay and bisexual African American men are expected to be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetimes (CDC, 2019c).

- Almost one in two (44 percent) of transgender African American women are estimated to be living with HIV (CDC, 2019d).

Given that there are few meaningful biological predispositions to HIV infection, these disparities result from the lived experiences and high rates of individual-, family-, and community-level trauma experienced by African

___________________

12 “Latinx” refers to a person of Latin American heritage and is used as a gender-neutral alternative to Latino or Latina. For more information, see https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Latinx (accessed July 18, 2019).

American, Latinx, and gay individuals in America, posited Machtinger. “In other words, HIV is a symptom of the much larger and more insidious reality of trauma,” he said, “and the same is true for the other conditions underlying health disparities in this country.” There are other examples of such disparities:

- African American women have three to four times the rate of pregnancy-related mortality (CDC, 2019e) and double the infant mortality rate compared to White women (HHS Office of Minority Health, 2017).

- Latinx children have the highest rates of childhood obesity (RWJF, 2019).

- American Indians and Alaska Natives have the highest prevalence of cigarette smoking (24 percent) compared to all other racial or ethnic groups in the United States; these groups have almost twice the rates of smoking compared to White Americans (15.2 percent) (CDC, 2019b). Native Americans have twice the rates of smoking and diabetes compared to White Americans (McLaughlin, 2010) and among the highest rates of suicide (CDC, 2018).

Trauma makes people more vulnerable to certain conditions, and it will also continue to act as an obstacle to effective treatments of those same conditions, according to Machtinger. This second realization, said Machtinger, underscores why so many medical conditions are stubbornly refractory to supposedly effective therapies. In his view, the difficulties practitioners have helping people lose weight or stop smoking, even in the face of serious health conditions, such as diabetes and lung disease, can be explained in part by the high rates of co-occurring trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder that go unrecognized and unaddressed in care plans.

Regarding the third realization—that clinics and environments of care often mirror the trauma experienced by patients—Machtinger explained that patients with a history of being abused by an intimate partner or who have had experiences in the foster care or criminal justice systems often feel unwelcome or unsafe in clinic environments. This may be because staff feel overwhelmed or unsupported and, as a result, can be dismissive, reactive, and distant from their patients. “In this way, our clinics can be trauma-inducing for patients, pushing them away from the care they need desperately,” Machtinger explained.

Machtinger suggested that one plausible reason why trauma goes unaddressed in medical care is that health care professionals are trained to solve medical problems, but the sources and effects of trauma are often difficult to fix. According to Machtinger, the instinct for providers is to consider trauma as something outside of their realm of care and responsibility, meaning that this fundamental driver of disparities remains invisible.

In developing a trauma-informed clinic for HIV patients, Machtinger and his partners discovered that this model is applicable to an array of other serious illnesses. One translatable factor is the power of partnerships to break down barriers between the clinic and community organizations. These partnerships, he explained, reduce isolation for providers and offer powerful avenues of healing for patients.

Machtinger described his clinic’s first partnership with Naina Khanna, executive director of the Positive Women’s Network, USA,13 which is the largest body of individuals advocating for and run by women living with HIV, according to Machtinger. Together, Machtinger and Khanna convened a national working group of 27 representatives from the military, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other government agencies, academia, community organizations, and individuals with lived traumatic experiences (Machtinger et al., 2015a).

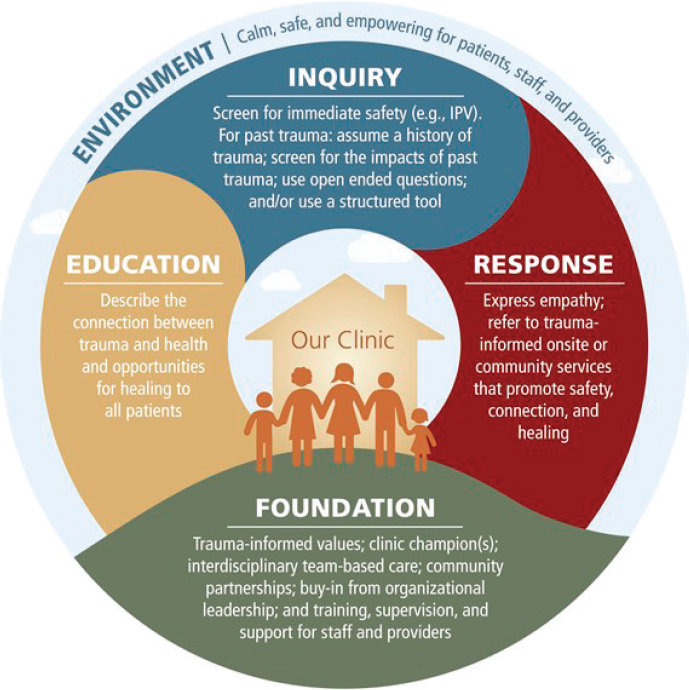

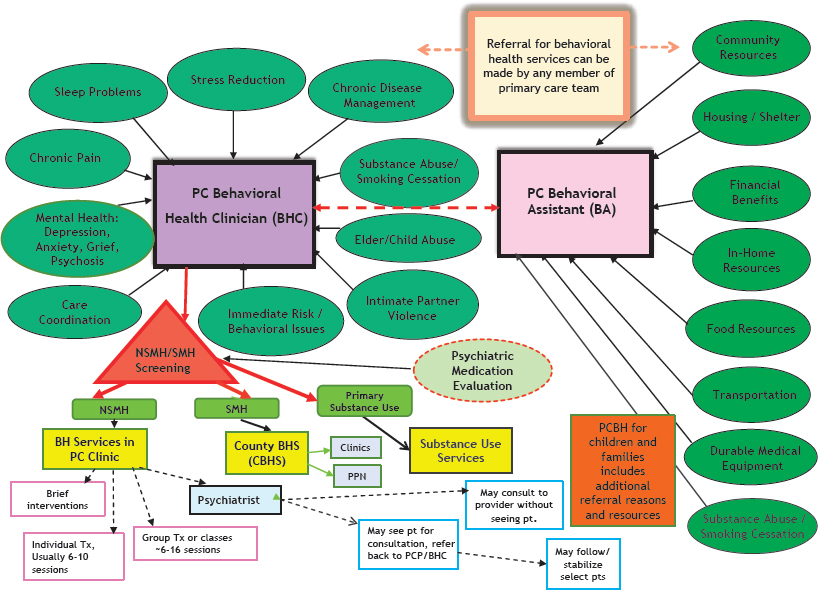

The model that emerged from that convening and follow-up meetings, said Machtinger, is based on existing evidence-based interventions, expert consensus, and input from patients (Machtinger et al., 2019). It encompasses five domains (see Figure 4), with evidence-based interventions available for each domain. The challenge now, he explained, is to determine how to best package these interventions into something that can be adopted by frontline clinics and is most acceptable to providers, most efficacious, and most cost effective. Currently, Machtinger and his colleagues are collaborating with other programs across the nation on a prospective, mixed-method evaluation of the model.14 He noted that the model builds on decades of work developing effective health system responses to intimate partner violence and that the Office of Behavioral Health Equity at the Substance

___________________

13 For more information, see https://www.pwn-usa.org (accessed May 24, 2019).

14 For more information and toolkits for this model, see https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884.html (accessed May 2, 2019), https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/areasof-expertise/trauma-informed-behavioral-healthcare (accessed May 2, 2019), and http://traumatransformed.org (accessed May 2, 2019).

NOTE: IPV = interpersonal violence.

SOURCES: As presented by Edward Machtinger, April 4, 2019; Machtinger et al., 2019.

Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has taken the federal lead on integrating trauma-informed practices into care across many fields of medicine.

Another important partnership that Machtinger’s HIV clinic formed was with Rhodessa Jones, co-founder and co-artistic director of the Medea Cultural Odyssey and the Medea Project: Theater for Incarcerated Women.15 Jones led an expressive therapy intervention with the clinic’s

___________________

15 For more information, see https://themedeaproject.weebly.com (accessed May 24, 2019).

patients using theater and writing. “By watching and studying her method, I learned for the first time that people can heal from even the deepest wounds of trauma, if offered the appropriate types of therapies,” said Machtinger. A subsequent study of Jones’s approach allowed him to better understand the ingredients for such a change that he and his colleagues are now applying to other interventions they are developing (Machtinger et al., 2015b). He noted this as an example of how a partnership within a community organization can build on the strengths of an individual’s community, extend the reach of a clinic, and offer treatments and healing that differ from, and are often far deeper than, what is available in standard clinics.

Machtinger noted that another approach to addressing disparities in health is to engage and integrate peers into health care. “Peers offer opportunities for patients to support each other’s healing in ways medical providers cannot and help guide the medical system’s response to their own needs,” said Machtinger. Integrating peers into care, he said, introduced a different way of thinking about patients and led to viewing them more as partners in their care. His clinic began engaging peers through focus groups and has moved incrementally toward a more integrated approach by including peers in bimonthly stakeholder meetings that help guide the interventions the clinic is implementing. The UCSF clinic now has a peer-led support group and peer-led intervention for co-occurring substance use and trauma and a peer-led leadership council that allows for posttraumatic growth.

An important aspect of this trauma-informed care model, Machtinger stressed, is that it is aspirational and can be implemented incrementally. “We have seen that even small steps can be felt powerfully as clinics move from being trauma-inducing to trauma-informed to trauma-reducing for patients, staff, and providers,” said Machtinger. “It is hard to convey how different our clinic feels now that we have incrementally adopted each element of a trauma approach to care.” He recounted how he recently saw three patients who openly discussed their struggles with cocaine addiction, and he was able to work with them to discuss ways to reduce their use of the drug. The lesson Machtinger took from these encounters was that these individuals felt safe enough in the clinic environment to reveal themselves and to ask for help. “The victory here is that it allows us as a health care clinic to more effectively address the smoking, medication non-adherence, substance use, and other trauma-related conditions that contribute to most of the disparities and health outcomes but have long been considered outside the realm of our expertise and responsibility,” he added.

Concluding his remarks, Machtinger said he believes that adopting a trauma-informed approach to health care is the best way for clinicians to meaningfully address the social issues that underlie most health disparities. Trauma-informed health care, in his experience, provides a pathway to change the culture of health care to one of health equity and the nature of communication and relationships to one where patients feel safe, cared for, and respected. “If we are going to begin to dismantle health disparities in our country, we are going to need to broaden our perspective of care from one that just focuses on treating symptoms and diseases to one that includes healing,” he said. As a bonus, he added, trauma-informed care can help providers heal themselves, connect better with their patients, and find joy in the process of helping people heal. In his view, such experiences are necessary for both patients and providers if the nation is ever going to make substantial progress toward reducing health disparities.

Discussion

Sarah Downer from Harvard Law School began the discussion with the panelists by asking what they thought needs to happen to change provider culture, which she called “one of the toughest nuts to crack.” Chin replied that, in his experience, interactional and experiential trainings on cultural competency and health disparities have the best chance of getting health care professionals to commit to achieving health equity. For example, the course on disparities required of all first-year medical students at The University of Chicago has fewer lectures and more small group discussions and more direct contact with various diverse patient populations and communities.

The other aspect of changing provider culture, said Chin, is having a health care system that supports providers and patients. Machtinger agreed with the importance of supporting providers who are working to address the fundamental drivers of health disparities and providing them with resources and access to knowledge. At the same time, he added, health systems need to hold themselves and their providers accountable for reducing disparities. In care of patients with HIV/AIDS, for example, clinicians are held accountable for patients’ viral load, but, Machtinger asserted, they should also be accountable for patients’ quality of life and for factors such as depression, substance use, and other patient-centered metrics that are causing harm and sometimes leading to deaths.

Chin observed that screening for health-related social needs is increasingly popular in health care. In California, for example, there is excitement

about the idea of screening for ACEs. The questions then become what to do with the resulting information, how to make sure that neither providers nor patients become overwhelmed by it, and how to use it appropriately. Machtinger posited there might not be a need for trauma screening in many patient populations because it is easy to predict that individuals seen in clinics that treat substance use disorders, mental illness, obesity, and HIV, for example, are likely to have a high burden of trauma. For the clinics that see a general population of patients, however, the added value from trauma screening is that it can help both providers and patients realize that trauma may be a key factor contributing to illnesses.

Chin commented that partnerships can expose clinicians to expertise in areas that are not traditionally part of health care. For example, health care systems should not tackle housing issues alone but should work with experts to address housing insecurity in the social services sector. What is important, he proposed, is for health care to know what role it can best play and then effectively partner with experts in those external areas that contribute to disparities and inequities.

Maguire asked the panelists to talk about the relationships they see between the social determinants of health and trauma-informed care. One difference between the two, said Hempstead, is money. Health care systems have the resources, but need to watch their bottom lines, according to Hempstead. Machtinger commented that trauma-informed care can be a helpful framework for connecting the many parallel movements in health care that seek to reduce disparities. Chin suggested that the roundtable could bring together these two fields and act as a conduit for knowledge transfer between them.

Christian Sinclair from the University of Kansas Health System and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine remarked that as a palliative care physician, he has no power to address the social determinants of health because he sees patients when it is too late to do anything about these determinants. He noted that while he can help individuals by advocating for them with their oncologists or health systems, he was unclear what role palliative care and hospice can play to advocate for and help larger populations before they come to palliative care. Johnson replied that if the goal is to provide equitable care for people with serious illness, reaching that goal has to start with talking about equitable care further upstream. When she and her colleagues surveyed hospices about the issue, they found that hospices are thinking about it and see an opening to participate in efforts

that are further upstream, such as blood pressure screenings or other kinds of chronic disease management programs in the community.

Chin remarked that health care professionals can advocate along different dimensions, starting with their own organizations and then perhaps becoming involved with national organizations. He also suggested speaking to community groups, writing commentaries for the local newspaper, and talking to elected officials.

An online workshop participant asked if there was a role for physician assistants (PAs) in addressing disparities and inequities in care. Hempstead replied that it is important for PAs to be involved with patients from the start of care so that they can form a trusted relationship with their patients. Johnson noted that the roles PAs can take varies across the nation but that she thinks of them as a part of the multidisciplinary care team, just as she does for nurse practitioners (NPs) and social workers. Chin added that there is a great untapped potential for greater involvement of PAs and NPs in serious illness care.

Denise Hess from the Supportive Care Coalition commented that, while she has great admiration for the ACEs study that Machtinger discussed, she has noticed that patients can feel stigmatized by the results of that study. That has led her to be curious about the study’s outliers—individuals who had high ACE scores but defy all expectations, likely due to resilience. Hess then asked Machtinger how he incorporates resilience and growth into his work. In response to the potential stigmatization of patients, Machtinger noted that the ACE screening is not used “dispassionately,” but rather serves to “awaken that provider, that clinic, and that patient, to the prevalence, the high rates of childhood traumas, and the role that that trauma is likely playing in the interaction with the health system [and] that provider, in terms of responses to therapies.” He added that he has observed that when patients can understand that their behavior is a result of what happened to them rather than what is wrong with them, they blame themselves less and can start looking for solutions. He called trauma-informed care a strength-based approach because it allows patients to focus on the strengths that have sustained them despite experiences of trauma instead of their perceived failings. He added that he and his colleagues measure resilience and are trying to understand how such measures can be helpful for providers and patients moving forward. Finally, Machtinger noted that there is an emerging field of research on the physiological effects of toxic stress responses.

IMPROVING ACCESS TO CARE AND ACHIEVING HEALTH EQUITY FOR PEOPLE WITH SERIOUS ILLNESS: ORGANIZATIONAL AND COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVES

Nadine Barrett from the Duke University School of Medicine introduced the second session of the workshop and expressed her excitement about the continued learning opportunities she anticipated from the diverse perspectives that would be heard. Barrett pointed out that this session would focus on the organizational and community levels of the social ecological model and would address some of the opportunities and challenges in navigating the integration of serious illness care with social service and faith-based organizations.

Whole Kids Outreach: Helping to Meet the Needs of Children with Complex Medical Problems

Sister Anne Francioni, executive director of Whole Kids Outreach,16 led off the session by describing how her faith-based organization has been helping families with young children in rural southeast Missouri for 20 years by providing services through home visit outreach and nursing programs. Whole Kids Outreach also offers services through its physical site in Ellington, Missouri. Francioni explained that the challenge her organization faces is delivering care in a region that is socially and geographically isolated and marked by widespread poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Children in this seven-county region in the Missouri Ozarks live in poverty and experience a high level of child abuse, neglect, and poor health as infants, according to Francioni (Missourians to End Poverty, 2018).

Francioni explained that access to pediatric specialty care is extremely limited, with the nearest facility located almost 130 miles away. Many families in the region do not have a car or the money to buy gas for a 260-mile round-trip visit to the nearest pediatrics specialty clinic, noted Francioni. Whole Kids Outreach’s approach is to take evidence-based programs to the home early in a child’s life. This allows the organization’s NPs to both educate parents and identify some of the problems these children will face in their homes as they grow up.

___________________

16 For more information, see https://wholekidsoutreach.org/#/home (accessed May 21, 2019).

Whole Kids Outreach uses Healthy Families America,17 a trauma-informed parent education program, to teach parents how to best support their children’s intellectual development, such as when to call a doctor and how to promote positive behavior without resorting to physical punishment. The basic idea, she said, is to find each family’s strengths and build on those to reveal individuals’ own resilience. Her organization also uses the Maternal–Child Nursing and Parents as Teachers programs,18 two other evidence-based home visiting models. These programs aim to teach parents to teach their children by modeling desired behaviors, such as valuing education. “We are building up the person who hopefully is going to be the shaper of the culture in that family system,” said Francioni. In addition to working with parents on health literacy, Whole Kids Outreach also works on building employment skills in parents to help address financial stress—an important contributor to the pressures that affect these families.

Francioni told several stories of children that Whole Kids Outreach has helped, including Marshawn, a baby born prematurely to a mother with a substance use disorder. Adopted by his foster parents, Marshawn grew into a strong young man who played basketball for his college. Eventually, Marshawn adopted a child who had been born into similar circumstances as he had been many years earlier. “You see the transgenerational problems that we can see with poverty and trauma, and you can see the transgenerational solution,” said Francioni.

Francioni said that the goal of Whole Kids Outreach is to increase the health literacy and networking skills of the parents so that they can tap into the network of providers and local organizations the program has built. The network was developed in an effort to increase the odds that these parents, many of whose families have lived in poverty and neglect for generations, can change the future course of the children they raise. Francioni noted that the communities in which these parents and their children live can be remarkably supportive of families in need, so an important role played by Whole Kids Outreach is to ensure that these families are connected with their communities. To that end, the program sponsors community gatherings to help reduce social isolation, bring families together, and provide fun activities that many of these families would not otherwise be able to afford. It also has a community center in Arrington, Missouri, that offers

___________________

17 For more information, see https://www.healthyfamiliesamerica.org (accessed July 2, 2019).

18 For more information, see https://parentsasteachers.org (accessed May 22, 2019).

a horseback riding program, summer camp, children’s weekend programs, youth volunteer opportunities, water safety lessons, Mom’s Day Out program, and parent cafés.

Francioni also pointed out that she and her colleagues have formed collaborations with several universities outside of the area. These connections are serving as a two-way street that keep her team informed of the latest approaches for dealing with the problems these families face while facilitating the universities’ efforts to engage in research with communities that are normally not accessible to them.

Familias en Acción

Adán Merecias, a community health worker with Familias en Acción19 in Portland, Oregon, explained that the focus of the organization is to engage its community to facilitate a sharing of knowledge between community members. When Familias en Acción first opened in 1998, its mission was to provide services to Latinas dealing with domestic abuse. Its mission has since expanded, Merecias stated, to include community health workers who engage with families confronting chronic disease.

Merecias explained that community health workers, or promotoras, are common in Mexico and are trained to provide health education services to the communities in which they live and to engage with the community to produce better health outcomes. Similarly, Merecias sees his role as a health educator as essential to preventing disease in his community, and therefore developed Familias en Acción’s community health education program. That program offers classes on diabetes, gardening, walking, and how to prepare for health care appointments. One course offering is called Empoderamiento20 (“empowerment”) and provides an introduction to palliative care and advance care directives. This course aids Familias en Acción’s clients with serious illness by helping families to understand what questions to ask of their providers before reaching the stage where they would need palliative care services. The course also helps them identify resources that they may need access to in the community.

Merecias also worked with Kaiser Permanente to better serve Latinxs with chronic disease in his community and facilitate access to services, such

___________________

19 For more information, see https://www.familiasenaccion.org (accessed May 17, 2019).

20 For more information, see https://www.familiasenaccion.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/FAM_HealthClasses-2-2.pdf (accessed July 3, 2019).

as health coaches and mail-order pharmacy services. Kaiser also provided Merecias with specific training on how to engage with his clients around ACP and Kaiser’s Life Care Planning program,21 which deals with some of the social determinants of health, such as food or housing insecurity or procuring transportation to health care appointments. This latter form of planning was possible, he explained, because he went into his clients’ homes and was able to learn about the home environment in a way that is not possible with clinic-based care.

As an example of the work he does, he recounted the story of one of his clients who had terminal cancer but did not understand his prognosis. His client asked him at one point if the treatments he had been receiving for many months were going to cure him. Not knowing the answer himself, Merecias offered to accompany his client to his next appointment with his oncologist and help ask his doctor to explain more about his condition and prognosis. In the end, after finally understanding that he was not going to be cured, the client made the decision to talk to his immediate family about his prognosis. He also decided to return to Mexico to spend time with his extended family, whom he had not seen for many years, before his cancer progressed to the point that he was unable to travel.

This story, Merecias said, illustrates two common roles of a community health worker: serving as a cultural bridge between the clinic and the community and as an advocate in the clinical environment. He explained that he has to tell providers that he is there with the patient as an advocate and explainer, not a language interpreter. “I am there to make sure that my client understands what is happening. I am there to make sure that they understand the diagnosis and that they have questions that they need to ask,” said Merecias. “All those things need to be addressed so that they can have a better health outcome.”

Merecias also told the story of Maria, a longtime volunteer with the organization. Maria worked with the Oregon food bank to modify its gardening program to make it more appropriate for her Latinx community. “Maria is a prime example of what happens when you bring somebody into an agency who is willing to learn, who has a lot of skills, but who might be willing to develop additional skills,” said Merecias. “She was [not only] able … to be trained to give specific classes but … also trained in other classes

___________________

21 For more information, see https://healthy.kaiserpermanente.org/health-wellness/life-care-plan (accessed July 3, 2019).

that she was able to modify so they would have a better fit for our specific community.”

Chinese American Coalition for Compassionate Care

The founder of the Chinese American Coalition for Compassionate Care (CACCC),22 Sandy Chen Stokes, explained that the organization aims to build a community in which Chinese Americans are able to face the end of life with dignity and respect. This is a simple goal, she said, but not easy to achieve, given the unique characteristics of the Chinese culture, language, and belief system. As an example, she noted that buildings in China and Taiwan do not have a fourth floor because the number four in Chinese culture is symbolic of death. “So please do not get upset if a [Chinese] family member or patient refuses to go onto the fourth floor or a room with the number four,” she said. “There is a good reason—they do not want to die.”

In Stokes’s view, the Chinese American community needs language- and culture-appropriate services and educational materials so that its members can communicate effectively with health care providers. The community also needs to trust the members of the care team and feel that that team respects its culture. For example, elaborated Stokes, when a visiting nurse arrives at a house and does something as simple as asking if she should take her shoes off before entering, the odds are high that the family will welcome her more readily.

Having end-of-life discussions is a challenge in Chinese culture because death is a taboo subject, and, in fact, Stokes was warned that CACCC would quickly fail because of that. She and the organization have succeeded, however, using a coalition model that has engaged 150 partner organizations and 1,400 individual members who share resources, train bilingual volunteers, and educate health professionals about how to work in the context of Chinese culture. CACCC has a strong community base of volunteers trained to serve as interpreters for local health systems and to support patients and families at the end of life.

According to Stokes, one unique characteristic of the Chinese community in northern California is that the majority of all Chinese Americans in health care professions are doctors. Stokes emphasized that very few become social workers—one profession that is important to end-of-life care. This is where CACCC’s large cadre of volunteers is helpful—many of them,

___________________

22 For more information, see https://www.caccc-usa.org (accessed May 17, 2019).

including nurses and social workers, have participated in one of six 30-hour trainings on hospice and palliative care so that they can go into hospitals and patients’ homes and provide culturally appropriate support.

One of CACCC’s accomplishments has been to translate and develop Chinese end-of-life materials, including Physician’s Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment forms, the CACCC’s decision aids, the educational series developed by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) and Hospice Foundation of America, and the Conversation Project. CACCC volunteers have also created and translated a variety of books, DVDs, and short documentary films about the end of life. To raise awareness that CACCC materials are available, not just for her community in California but for all Chinese Americans, Stokes has engaged in newspaper and television campaigns and she and other CACCC volunteers regularly conduct community outreach at senior centers and other venues used by the Chinese community.

Another service CACCC offers is a Chinese volunteer hospital ambassador program. At El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, California, CACCC-trained Chinese-speaking ambassadors get a list of all Chinese-speaking patients in the hospital and visit them throughout the day. Hospital staff report that these ambassadors have been helpful in working with Chinese American patients. CACCC is in the process of expanding its ambassador program to other hospitals in the California.

Stokes sees CACCC as a bridge that connects health care providers with the Chinese community and connecting them with families and patients who are facing the end of life. One tool for helping families deal with the taboo of discussing death is CACCC’s Heart-to-Heart® cards. Modeled after the Coda Alliance’s Go Wish cards, each playing card contains a statement or conversation prompt about end-of-life wishes in both Chinese and English, encouraging patients to convey their wishes to family members. Each suit focuses on a different aspect of end-of-life issues—for example, hearts deal with spiritual concerns and diamonds with financial concerns. The cards are often used at Heart-to-Heart® Cafés at which people eat pastries, drink tea, and talk about end-of-life issues in a friendly, non-threatening environment.

In closing, Stokes said her goal now is to replicate what CACCC has done in other communities, not just across the country, and not just for Chinese-speaking communities. She would also like to establish partnerships with universities to research end-of-life issues among Chinese Americans.

Discussion

In the discussion following the presentations, Machtinger commented on Francioni’s organization’s method of involving parents in its work in an effort to interrupt generational cycles of trauma. Too often in the trauma field, he said, the focus is exclusively on children, but children do not exist in isolation. In fact, he said, an adult is involved in every ACE traditionally listed on the ACE questionnaire. For this reason, Whole Kids Outreach’s focus on helping parents heal seems powerful to him. He asked Francioni how her program came to focus on adults and whether that focus creates challenges with funding or generating compassion in the community, given that troubled adults seem to trigger less compassion than troubled children. Francioni replied that her background in pediatrics is what led her to focus on adults because she knew the importance of teaching adults how to care for their seriously ill children once they leave the hospital. She sees her organization’s mission as breaking the cycle that has created five generations of poor health and poverty in the area in which she works. She noted that one of the first things she does when she meets a new family is to administer an extensive parent survey that reveals the traumas they suffered as children. Then, she teaches them about the power they have to create a better life for their children and to heal themselves for the benefit of the entire family.

An online participant asked the panelists to speak about how they managed to convince the hospital decision makers to partner with their organizations to tackle the problem of health equity. Stokes said that health providers heard about CACCC’s status in the community and wanted to learn more about the organization’s work. Once health systems learned about the services CACCC provides to its Chinese-speaking community, they became eager to talk about partnerships. Merecias said his organization’s best connection with the health system is through social workers rather than clinicians. He noted, too, that health systems in the northwestern United States are starting to recognize the positive effect community health workers can have with their patients. The main challenge his organization faces, he pointed out, is reimbursement for services.

Francioni remarked that there are no hospitals in her region in southeast Missouri, so she develops relationships with local pediatricians. Her biggest challenge is funding, and she recently had to drop three counties from her coverage area because she did not have the funds to pay nurses to work in these areas. While she would love to work with a large group of physicians and hospitals, her organization currently does not have the

capacity to do so. Barrett commented that aligning priorities with those of the health care system could provide a means of tapping into reimbursement streams.

Workshop participant Thomas Quinn from Jewish Social Service Agency Hospice in Montgomery County, Maryland, asked Stokes and Merecias to speak more about how they train professionals to interact better with Chinese and Latinx communities. Stokes replied that she focuses on how to help providers communicate more effectively with Chinese-speaking patients and their families by helping them understand Chinese culture. CACCC also holds a forum at least once per year and invites community leaders and health care providers to discuss specific topics in a safe and collegial environment. Merecias noted that Familias en Acción offers training at its annual conference on how to better serve Latinxs and online and in-person training that can earn providers continuing medical education credits. The trainings concentrate on how to build rapport with Latinx patients. For example, something as simple as using the terms señor and señora can go a long way to building trust and a connection with patients and families.

Patricia Bomba from Excellus BlueCross BlueShield thanked the panelists for their consistent message about the value of bridging the community and the health care team. She also applauded the way Merecias worked with his client with terminal cancer to help him understand his prognosis and change the entire dynamic of what his goals were for the last part of his life. She suggested that the panelists examine whether their programs were having any effect on reducing unwanted hospitalizations or emergency room visits, which might open up opportunities for reimbursement.

IMPROVING ACCESS TO CARE AND ACHIEVING HEALTH EQUITY FOR PEOPLE WITH SERIOUS ILLNESS: PATIENT/FAMILY AND CLINICIAN PERSPECTIVES

The workshop’s third session began with a video provided and produced by Liz Margolies, founder and executive director of the National LGBT Cancer Center, which told the story of Jay Kallio, who was age 58 and a two-time cancer patient at the time the video was made. Kallio, a transgender man who came out as a lesbian at age 12, spoke about the abuse and bullying he lived through as an adolescent. When he finally transitioned to male at age 50, he suddenly felt that as a White man, he was in a privileged position and was treated better. “I found that when I talked, people

stopped interrupting me and took my ideas seriously. People accepted my authority and leadership in situations,” he said.

The one caveat, he noted, was that when he had to seek medical care for cancer, his health care providers did not consider him a “real man.” The result, he said, was that he would “plummet off this cliff of respect and authority I had gained with the outside world into a pit of being a freak, mentally ill, and someone who was needing psychiatric care rather than cancer care.” Not long after the video was made, Kallio died from metastatic lung cancer.

Following the video, session moderator Graves commented that she also carries a great deal of privilege with her, but unlike Kallio, she has been able to bring that privilege into her health care experiences, including when she was treated for cancer. Her privilege showed, she said, every time she was viewed as assertive rather than aggressive or angry, when she insisted that her tests be done sooner rather than later, and when she gently called out her radiologist for not reading her chart prior to giving her his clinical advice. “My privilege showed when I laid face down in that breast MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] machine and the happy images that they had placed in the sightline were of three happy, smiling, White babies, when I knew I was in a predominantly African American county,” Graves added.

Communication Can Drive Health Equity in Serious Illness Care

Justin Sanders, faculty member of the Serious Illness Care Program at Ariadne Labs and an attending physician in the Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care Department at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, spoke about the ways in which communication can drive health equity. He began his presentation by commenting on a remark that Kallio made at the end of the video: that he felt that his body was worn out from fighting discrimination, bigotry, and poverty all of his life. Sanders noted that this statement is supported by the theory of allostatic load—the cost of chronic exposure to fluctuating or heightened neural or neuroendocrine response resulting from repeated or chronic environmental challenges that are stressful to the individual. “Ample evidence supports a relationship between race and ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and even social relationships on allostatic load,” said Sanders.

Kallio’s experiences are unfortunately not unique, and they actually characterize the experiences of many individuals with serious illness who

come from marginalized communities, explained Sanders. What stands out from the interviews he conducted with community members, patients with serious illness, and bereaved caregivers in the African American community, he recalled, are the small traumas and microaggressions to which they become accustomed and the mistrust that many members of that community bring to their clinical experiences. Fortunately, he added, because good communication relates to rapport, and rapport tends to grow with mutual exposure, patients with serious illness often express a high degree of trust in their clinicians.

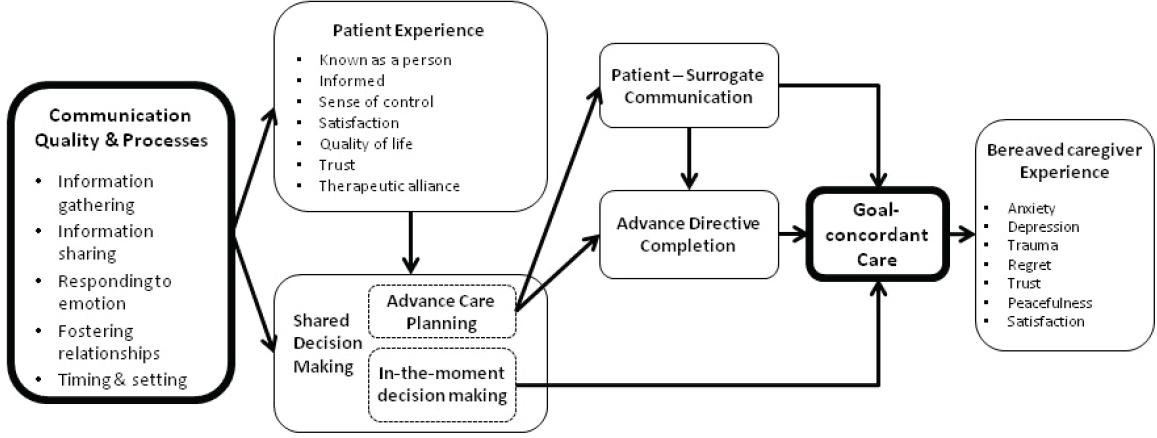

Health equity, he continued, is not equality—ensuring that everybody has access to the same thing—but rather means that the resources are allocated in ways that address systematic inequalities in the outcomes of clinical care. In that context, health equity in serious illness care is more than just access to a specialist or primary palliative care physician. It must also consider the outcomes around which health equity is achieved—through care that reflects the patient’s goals, values, and preferences (goal-concordant care). What enables goal-concordant care, Sanders added, is communication.

Sanders and his colleagues have developed a conceptual model and approach for measuring serious illness communication and its effect on achieving goal-concordant care (Sanders et al., 2018) (see Figure 5). He explained there is a significant amount of literature and personal experience demonstrating the failure of communication for people of color and other marginalized communities. There is evidence of deficits in every one of the communication, quality, and process indicators in this model. These deficits result in people from these communities feeling less informed, less in control, and less satisfied; believing that they have a lower quality of life; and having less trust in health care institutions (Johnson, 2013; Loggers et al., 2009; Sanders et al., 2019). This is true, Sanders said, even though nationally representative studies, such as the Health and Retirement Study and the National Health and Aging Trends Study, suggest that there are no differences by race in receiving goal-concordant end-of-life care from the perspective of bereaved caregivers.

Sanders and his colleagues have been conducting interviews with bereaved caregivers of African American and White patients, and a preliminary analysis of the data yielded results that were both unsurprising and surprising. The degree to which the quality of communication reflected the quality of care was unsurprising. What was surprising, Sanders explained, was that no matter how bad communication was, no caregivers said that

SOURCES: As presented by Justin Sanders, April 4, 2019; Sanders et al., 2018.

their loved ones received care that was inconsistent with their goals. “This suggests to me that we have set a really low bar in health care for what good communication is,” said Sanders. “My hope would be that people would have a goal, or an expectation at least, of experiencing communication that feels supportive and improves their illness experience.”

Sanders pointed out that there is substantial evidence for individuals with serious illness that links conversations about patients’ values and goals with improved quality of life, better patient and family coping, reduced anxiety and depression, enhanced goal-consistent care, more and earlier hospice care, and fewer hospitalizations at the end of life (Sanders et al., 2018; Wright et al., 2008). Sanders noted that given the multiple benefits of good communication, it is a wonder that it happens so rarely. He added that one reason is that professional training for many clinicians does not include communication skills. Clinicians can, however, be trained to communicate better, and there are a variety of programs that support clinician training in high-quality serious illness communication. “We need to incentivize clinicians to take advantage of these programs and to ensure that the innovations developed by these programs work their way into undergraduate and graduate health professional training,” said Sanders.

Sanders further explained that clinicians’ implicit biases, some of which are driven by an overinterpretation of what individuals from some communities do or do not want as it relates to decision making or the elements that support it, can lead to poor-quality communication. Poor communication in turn contributes to health disparities (Penner et al., 2014). Sanders compared bias to a chronic illness that may be cured in the future but is presently incurable. However, he elaborated, it can be controlled, and part of doing so involves educating clinicians about how bias can influence their interactions, their communications, and their decision making in ways that systematically affect one type of patient differently than another.

As an example of how it is possible to work with health systems to ensure that bias plays less of a role in communication and decision making, Sanders described an approach he and his colleagues at Ariadne Labs have developed. This approach, which he believes addresses discrimination and bias by attempting to ensure that every patient with serious illness has access to skilled clinician communication, involves clinical tools, clinician training and coaching, and several systems innovations to elicit and make accessible the information about patients’ goals, values, and priorities. This approach includes selecting the right patients who are at risk of dying, working with them to make sure they are prepared for and expect these conversations,

providing reminders to clinicians about when to have these conversations, and documenting the conversations in ways that are accessible at multiple points of care.

In thinking about ways to ensure that communication will advance health equity, Sanders noted that key issues to consider include the following:

- Are clinicians trained to initiate conversations about things that matter to patients?

- Do they feel supported to have these conversations?

- Are the conversations happening?

- Are the conversations improving patient experiences?