The workshop’s fifth panel session expanded on earlier mentions of return on investment (ROI), particularly with regard to creating a business case for investing in interventions when the benefits of those investments might not accrue to those who make the investments or they might not be realized until far into the future. The three panelists in this session were George Miller, a Fellow at the Altarum Center for Value in Health Care; Dawn Alley, Director of the Prevention and Population Health Group at the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI); and Katherine Hobbs Knutson, Chief of Behavioral Health at BlueCross and BlueShield of North Carolina. Following the three short presentations, John Auerbach moderated an open discussion.

ASSESSING THE VALUE OF THE SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

As the discussions at the workshop have indicated, research suggests that investments in interventions that address the social determinants of health not only improve health but can be cost effective and cost saving. However, said George Miller, there are fairly significant economic impediments to investing in these interventions, not the least of which is a lack of understanding in many instances of the economic value of a particular intervention and the timing of any economic returns. Another impediment, he added, is the “wrong pockets” problem that Sarah Szanton noted in the previous panel session. “A better understanding of these issues might encourage cooperation among stakeholders in investing in social determinants,” said Miller.

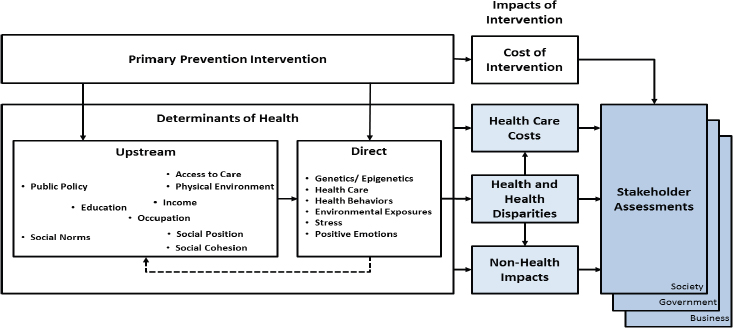

With funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Miller and his colleagues have developed an approach to thinking about how to invest in the social determinants of health and what the value of those investments might be from the perspective of different stakeholders. They are then using this approach to synthesize existing data about the effects of interventions over time of investments designed to modify the social determinants of health on health outcomes and financial returns. Underlying this approach is a high-level framework for describing the effects of the social determinants of health (see Figure 6-1).

The Value of Health Tool uses intervention-specific effects as a function of age on mortality, morbidity, health care costs, earnings, and incarceration costs plus generic economic inputs to produce as its output an overall value to different stakeholders, the effect of health care spending by different stakeholders, and the maximum investment to achieve the

SOURCES: Presented by George Miller, April 26, 2019, at the Workshop on Investing in Interventions That Address Non-Medical, Health-Related Social Needs. Adapted from Miller et al., 2015.

desired ROI and cost effectiveness. Miller and his colleagues have used this tool for a variety of interventions, including

- early childhood interventions;

- trauma prevention;

- smoking prevention;

- obesity prevention;

- the burden of the opioid epidemic;

- lead exposure mitigation at the national, state, and city level;

- pediatric asthma in a Medicaid population; and

- the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives in a Medicaid population.

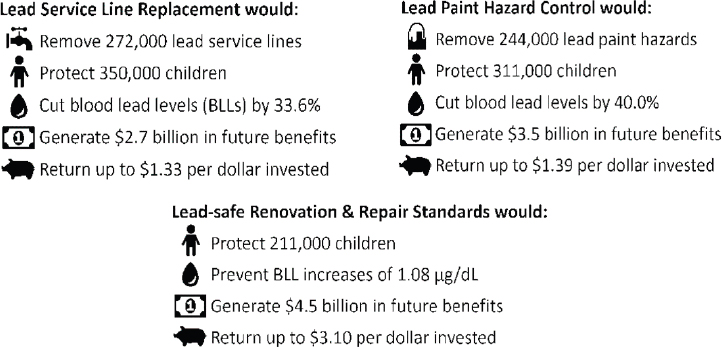

As an example, Miller looked at the effect of reducing childhood exposure to lead poisoning using three particular interventions: service line replacements to eliminate lead in household drinking water, controlling exposure to lead paint in older homes, and using lead-safe standards when repairing older homes that may have lead in them. Each of these interventions produces a significant improvement in blood lead levels and overall health, and in each case, there is a positive ROI for investments in these interventions (see Figure 6-2). These returns, however, accrue to different stakeholders over time. In fact, said Miller, the largest part of these returns has to do with improved downstream income, a payoff many years in the future.

SOURCE: Presented by George Miller, April 26, 2019, at the Workshop on Investing in Interventions That Address Non-Medical, Health-Related Social Needs.

RETURN ON INVESTMENT AT THE CENTERS FOR MEDICARE & MEDICAID SERVICES

Dawn Alley began her presentation by noting that figuring out how to determine the ROI for prevention interventions in general and social determinants of health in particular in a value-based context is uncharted territory. She explained that when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is considering a new coverage decision for a medical procedure, it bases that decision on clinical effectiveness, rather than cost effectiveness. However, for a prevention intervention tested through the CMS intervention the goal is to remain at lease cost-neutral and have an ROI of at least 1:1.

One consideration for CMS is how many patients will need an intervention. For example, it may make sense to pay for an air conditioner for someone with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease because it will keep that person out of the hospital. As a payer, however, CMS needs to consider how many air conditioners it will have to pay for to prevent one hospitalization. In the same vein, CMS’s diabetes prevention program targets a narrower group of people with prediabetes than would be included using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of prediabetes.

Alley explained that CMS is looking for opportunities to embed work on health-related social needs into value-based payment models. As an agency, she said, CMS is working to eliminate fee-for-service payments

and delegate more risk to providers. “But we recognize that as we delegate risk to providers and plans, it is also incumbent upon us to think about how we invest in public health solutions and some of these infrastructure elements,” said Alley. On a closing note, she said that CMS recognizes there are other forms of ROI beyond financial and that there are many other drivers of provider behavior in a value-based environment. Some interventions, for example, may improve patient satisfaction, improve provider satisfaction, reduce provider burnout, or improve quality measures.

BEYOND THE RETURN ON INVESTMENT

Katherine Knutson’s first point in her presentation was that a positive ROI may not be enough to justify moving ahead with an intervention. “There are many more things beyond the economic argument that contribute to whether an organization is going to invest,” she said, adding that funders often have many interventions with ROIs presented to them, making it important to be able to articulate how a particular intervention and its ROI stacks up against all the other potential interventions. It is also important, she said, to account for the fact that the funding entity may not have responsibility for the intervention’s outcome or benefit from future economic returns.

When evaluating the ROI, it is important to know the prevalence rates for the non-medical, health-related social needs and what dose of the intervention will be needed to produce a meaningful improvement in the health of the targeted population and cost savings at the expected scale, said Knutson. She acknowledged that with non-medical social needs, the true burden in a given population is often not known. She also noted that even if the ROI is low, some funders will still invest in an intervention if it addresses issues aligned with the organization’s mission.

Knutson said that her organization is building alternative payment models for behavioral health and is focused on addressing the social needs of its clients, understanding that if it does this well, it will see the outcomes it desires. One challenge, she said, is figuring out how to pay for these interventions in a value-based model. Particularly with shared savings, there may be a dozen entities contributing to the intervention, and parsing out the savings to all of them dilutes the financial incentive to any one of the entities.

Another challenge in scaling interventions to address non-medical, health-related social needs across a state, for example, is that there will be different social environments and different kinds of community-based organizations for which to account. As a result, it can be difficult for a payer to trust that it is paying for an intervention at the appropriate scale

and quality while meeting the needs of these disparate communities. “Every population is going to have a different mix of social determinant needs, so figuring out the payment model that accounts for all of the different types of needs that a population could have, and doing that at scale across a large geography, is a challenge,” concluded Knutson.

DISCUSSION

To start the discussion period, John Auerbach noted that most medical services get approved for reimbursement with no ROI analysis, as demonstrated by the incredibly high-cost services offered at the end of life even when the evidence suggests there will be little benefit in terms of extending life or improving the quality of life. In contrast, it seems that interventions to address non-medical, health-related social needs have to meet a high ROI standard. He then asked the panelists if there are specific returns used in their organizations as criteria for deciding about approving a new benefit. Alley replied that cost and utilization are major criteria, and she acknowledged that developing the data needed to determine cost, utilization, and outcomes requires testing the intervention in a large number of people. Her hope is that the Accountable Health Communities model will help generate that type of data. Other considerations include how to recognize which providers are qualified to offer a particular intervention, how many minutes it will take to deliver a particular service, and what a reasonable payment for that service will be. “We at CMS need to be clear on what it is we are paying for, so we need some structure around the intervention as well as the data on how it impacts utilization,” said Alley.

For Knutson’s organization, it is important to first define what return means, because there will be different returns for different audiences. The chief financial officer, for example, is likely to be interested in financial returns, the clinical team will want to know about health effects, and the chief executive officer might be more concerned with whether an intervention will help the organization fulfill its mission.

Auerbach then asked the panelists if their organizations have a specific time period in mind when they consider the ROI for a given investment. Knutson responded that this represents a major challenge to investing in interventions that may pay off decades later, such as prevention and early intervention efforts. Alley said she feels the same way about this issue, adding that she was not aware of an industry-wide standard. CMS, she noted, typically looks at returns over a 10-year period.

Miller said that it is incumbent on health systems to cooperate with other stakeholders to find ways to invest in interventions that everyone agrees are effective and a good idea in a global sense but for which no one stakeholder will earn a significant return on their investment in the

near term. An approach to doing this, he said, might be to have a trusted broker who can elicit from each stakeholder how much they are willing to invest in an intervention. The trusted broker would then add those investments and if the total exceeds the amount needed to deploy the intervention, the trusted broker can go back to each stakeholder and tell them the investment they need to make will be smaller than expected (Nichols and Taylor, 2018). Alley commented that CMS’s Accountable Health Communities might be able to serve in the role of trusted broker.

Responding to a question from Auerbach about how to frame the “wrong pockets” problem for effective interventions, Miller said that altruistic investors may not care about returns going to the wrong pockets. Some investors, however, do care about financial returns and may pass on paying for an intervention unless there is a positive ROI for them.

Seth A. Berkowitz asked the panelists for ideas on how to change the emphasis on a narrowly defined financial ROI as a consideration for investing in a health-related social needs intervention. Alley replied that value-based payment frameworks represent a tremendous opportunity to move forward with these interventions, but these frameworks potentially exclude interventions that would generate tremendous value when considered from a broader perspective that includes driving improvements in health and the quality of care. Another concern of hers is that organizations are going to do the easy things first, such as engaging in activities aimed at high utilizers, under these value-based frameworks, and that harder challenges, such as addressing non-medical, health-related social needs, will take a back seat to these easier opportunities to reduce costs quickly.

After each of the panelists called for more research on the non-medical, health-related determinants of health and social needs and on the effectiveness of interventions designed to address those issues and their associated ROIs, Kelly Doran from the New York University School of Medicine asked the panelists to comment on the potential role of health care system regulation that might encourage more investment in social needs. Alley replied that CMS has issued a proposed set of questions that patients should be asked in a post–acute care setting, such as a skilled nursing facility, regarding their social needs, including transportation. She then noted the need for anyone considering regulatory proposals to consider what specific requirements they would want and how they would codify evidence-based interventions or the desired health outcome.

Knutson did not suggest any recommendations but did note that she has seen through her experience of being part of three accountable care organizations that value-based payment arrangements are incentivizing health systems to look at the non-medical drivers of health care costs and make investments in behavioral health, social determinants,

and social needs interventions. Polsky added that he has seen a culture clash between health care systems, which are being forced to look at costs and the ROI, and social services, which historically have not cared if there was an ROI associated with providing food or housing for those in need. Addressing that culture clash is going to need a better evidence base, which in turn requires more research, he said. Alley cautioned that such change is going to be hard and will take time, as evidenced by the experience CMMI has had with some of the models it has tested. Many interventions, in fact, showed slight increases in costs before they started to decline over time.

Karen DeSalvo raised the possibility of tapping into the pharmaceutical industry’s clinical trials process to collect data on unmet social needs. She noted that in the course of conducting research in some of the nation’s poorest communities, they identify unmet needs and address them so people continue participating in clinical trials.

After commenting that regulations around quality metrics might be able to play a role in incentivizing health care systems to work more on social needs, Miller suggested that it would be helpful if Medicare and Medicaid continued loosening some restrictions around what constitutes an appropriate investment beyond those on direct health care. Knutson added that value-based reimbursement policies applied to the total cost of care have the potential to turn the current system on its head and make health and prevention rather than illness the focus of care.

In a final comment in the session, Alley said it is still unclear in a value-based system who should be held accountable and how to pay for which outcomes. As an example of progress, she said that CMS is working with Maryland on population health credits that will allow the state to keep a larger part of any savings based on reducing the prevalence of diabetes in the state. While she characterized this experiment as exciting and remarkable, it is not something that would be feasible at the practice level, for it would not make sense to pay providers based on the incidence of diabetes in their patient populations.