The workshop’s fourth panel moved the discussion from one focused on interventions to address specific social needs to one looking at interventions addressing multiple social needs or the whole person. The four speakers in this session were Shreya Kangovi, Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and founding Executive Director of the Penn Center for Community Health Workers; Sarah L. Szanton, Health Equity and Social Justice Endowed Professor and Director of the Center for Innovative Care in Aging at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing; Marsha Regenstein, Professor of Health Policy and Director of Research and Evaluation at The George Washington University’s National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership; and Stacy Tessler Lindau, Founder and Chief Innovation Officer of NowPow and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medicine-Geriatrics at The University of Chicago. An open discussion moderated by David Chokshi followed the four short presentations.

IMPaCT: A STANDARDIZED, SCALABLE COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKER PROGRAM

To start her presentation, Shreya Kangovi told the story of Purnimaya, a woman who spent 25 years living in a tent in a Nepalese refugee camp until 2 years ago, when she was resettled to Nashville, Tennessee. Maya found herself in a foreign land, overwhelmed by dark memories, so she spent her days laying on a pile of blankets on the floor, too depressed to climb into bed. Concerned about his wife, her husband took her to a refugee clinic in downtown Nashville, where they met Hannah, a community health worker with the Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets (IMPaCT) program. Hannah, when she gently asked Maya in their native Nepalese tongue what she thought would help her to feel better, learned that Maya felt she was dying of loneliness.

Hannah visited Maya in her home each week and eventually convinced her to meet a group of other Bhutanese women, who reminisced about home and brought fresh vegetables from their small gardens to share. Week by week, Maya began to feel joy again, joy that led her to work with Hannah on other things, such as seeing a behavioral health specialist, arranging transportation for appointments, and getting low-cost medications. Maya began to spend her days outside gardening and her nights sleeping well in her own bed.

To Kangovi, Maya’s story gets to what it means to think about the whole person. “Yes, Maya needed linkages to behavioral health and referrals for transportation, but she needed something more,” said Kangovi. “That more is love, the power of human connection.” The challenge she added, is figuring out how to turn the power of human connection into a scalable intervention. Addressing that challenge motivated her and her team to build IMPaCT, a standardized, scalable community health worker program that starts with getting to know each patient as a person and finding out from patients what they need to improve their health.

Kangovi explained that what Hannah did for Maya was magical but not accidental, for Hannah was selected using a specialized algorithm designed to identify natural helpers and listeners. The questions Hannah asked Maya came from an interview guide that Kangovi’s team designed after interviewing thousands of low-income patients, and she documented her notes in an app co-designed with community health workers. Hannah’s supervisor at her clinic was a manager trained using IMPaCT’s online interactive platform.

Kangovi and her colleagues have studied this approach in three randomized controlled trials that demonstrated improved chronic disease control, primary care access, mental health, and care quality while also achieving a 65 percent reduction in total hospital stays (Kangovi et al., 2016, 2017, 2018). These outcomes, she said, translate into a return

on investment (ROI) of $2 for every $1 spent within the same fiscal year, which enabled the program to grow so that it now serves some 10,000 patients in the Philadelphia region. Her team is building IMPaCT programs across the country so that, as she put it, a Nepalese woman in Nashville, a veteran in Pittsburgh, and a migrant worker in Louisiana can use the same standardized operating system to unlock their ability to unleash the power of human connection.

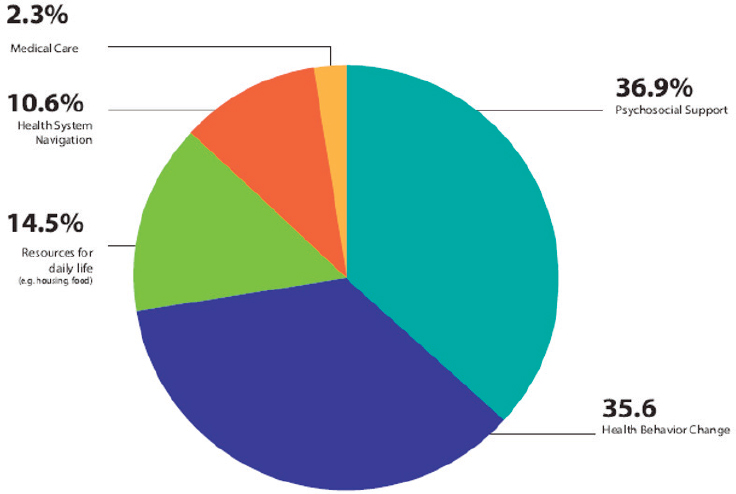

Concluding her remarks, Kangovi noted that while the workshop was well attended by experts, those are not the people these programs serve. “I do think it is important that we anchor this conversation in what actual low-income people would want in order to improve their own health,” she said. In her case, speaking with 10,000 low-income individuals and asking them what they thought would improve their health identified five major categories (see Figure 5-1). Most individuals, she said, want informal psychosocial support or support for making health behavior changes, while nearly 15 percent want referrals to resources for daily life, such as housing or transportation. Almost 11 percent want support with health system navigation, and only 2 percent want help with a specific medical issue.

SOURCE: Presented by Shreya Kangovi, April 26, 2019, at the Workshop on Investing in Interventions That Address Non-Medical, Health-Related Social Needs.

COMMUNITY AGING IN PLACE—ADVANCING BETTER LIVING FOR ELDERS (CAPABLE)

What the CAPABLE program does, said Sarah Szanton, is unleash people’s own goals and desires to help them age in place in their home through 16 weeks of care by a nurse, an occupational therapist, and a handyman. As a long-time house-call nurse practitioner, Szanton had seen how much someone’s home environment could be as disabling as a medical condition. Too often, she said, clients would answer the door on hands and knees or had to drop their keys out of an apartment window because they could not go down the stairs to greet her. One 100-year-old woman had to crawl into the kitchen because her wheelchair would not fit through the door, so all she could eat was whatever food she could reach from her knees.

Szanton reminded the workshop that close to 5 percent of Medicare spending is preventable and that the frail elderly account for 51.2 percent of the total of potentially preventable spending (Figueroa, 2017), and those are the instances CAPABLE is trying to prevent. The program costs less than $3,000 per patient and provides an ROI of between sevenfold and tenfold, including savings for Medicare and Medicaid, within 2 years. The program is now in 27 locations in 12 states and has been shown to improve activities of daily living disability in older adults with multiple conditions, as well as reduce depressive symptoms. Overall, some 79 percent of participants improve, she added.

The core concept driving CAPABLE is that the person and the environment have to fit together, which is why the program includes a handyman to make repairs and modifications that eliminate the physical barriers in the home that keep individuals from getting around in their homes or getting out of their homes to engage in their communities. One common complaint of CAPABLE clients is that they are lonely because they cannot leave their home. A client may have a hard time getting dressed, for example, so the occupational therapist will work with the client to achieve the goal of self-dressing using a zipper helper and a sock aid provided by the program. The program might also provide a portable car hook and swivel seat so the client can get into her daughter’s car, for example. Together, those items cost less than $100, but they represent the difference between someone being able to participate in the community and not. Another client might want chairs placed around the home so he can practice getting up and walking instead of crawling around the home. “It is their own motivation and their own strengths that dictate what the nurse, occupational therapist, and handyman work on,” said Szanton.

This approach, she added, builds self-efficacy for tackling new challenges. She noted that CAPABLE clients will sometimes call months after finishing the program to talk about new goals they want to achieve.

ADDRESSING SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH THROUGH MEDICAL–LEGAL PARTNERSHIPS

The National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership, explained Marsha Regenstein, is a group of people who work with hundreds of organizations around the country to try to advance the notion of bringing lawyers to the bedside to help patients get access to the benefits and the services to which they are entitled. The key element of the program is a civil attorney who partners with a health care organization that has a mechanism in place to identify patients in need. The lawyer then provides services that can range from a 5-minute phone call that unlocks some benefit for the patient to months of work on a more challenging issue. Because the intervention is highly variable, it suffers the same evaluation challenges faced by other programs addressing social determinants of health that are highly variable, she added.

Regenstein described three examples (see Table 5-1) of the different constructs of medical–legal partnerships that health care organizations have adopted (Regenstein et al., 2018). An example of the general population model, which she called the bread-and-butter medical–legal partnership, is a joint effort between the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and the Legal Aid Society of Greater Cincinnati. This program referred 825 patients in 1 year to program lawyers, who largely dealt with legal issues involving housing, public benefits, and education.

The special population model targets specific clinical issues or life-stage issues. One example of this model addresses postpartum depression and involves a partnership between the Delaware Division of Public Health and the Community Legal Aid Society, Inc. In this case, lawyers make home visits to help patients with issues involving family law, immigration, and housing.

Whitman-Walker Health in Washington, DC, which has embedded medical–legal partnering throughout its activities, is an example of the alternative legal services models. Regenstein said that Whitman-Walker Health thinks of this partnership, which has 11 full-time lawyers on staff, as part of providing care and not as a legal intervention. The most common legal needs that the program addresses include public benefits and transgender identity legal document changes.

In closing, Regenstein noted that several federal agencies have recognized the value of medical–legal partnerships. For example, the Health Resources and Services Administration now recognizes legal services as an “enabling service,” which allows federal health center dollars to pay for a medical–legal partnership. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) classifies “screening for health-harming legal needs” as an improvement activity under Medicare’s merit-based incentive payment system. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

TABLE 5-1 Three Models of Medical–Legal Partnerships

| Health Care Organization | Legal Partner Organization | Referred for Legal Services in 2016 | Primary Site of Legal Services | Patient Population Served by Partnership | Most Common Legal Needs in Order of Prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | Percent of Patient Population | |||||

| General Population Model | ||||||

| Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (Ohio) | Legal Aid Society of Greater Cincinnati | 825 | 3 | Three primary care clinics at nonprofit pediatric hospital | Children and families |

|

| Special Population Model | ||||||

| Delaware Division of Public Health | Community Legal Aid Society, Inc. | 181 | 0.5* | Maternal and child health program | Pregnant/postpartum women |

|

| Alternative Legal Services Model… | ||||||

| Whitman-Walker Health (Washington, DC) |

No legal partner organization | 1,546 | 10 | Ambulatory care/behavioral health sites of FQHC | HIV-positive, LGBTQ, and health center patients |

|

NOTES: * Legal services were not offered to the total patient population; therefore, the share of patients served at this organization underrepresents patient need for these services. FQHC = federally qualified health center; LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer.

SOURCES: Presented by Marsha Regenstein, April 26, 2019, at the Workshop on Investing in Interventions That Address Non-Medical, Health-Related Social Needs. Adapted from Regenstein et al., 2018. Republished with permission of Project Hope/Health Affairs Journal from Addressing social determinants of health through medical-legal partnerships, Regenstein, M., J. Trott, A. Williamson, and J. Theiss. 37, 3, 2018; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

has singled out medical–legal partnerships in recent mental health and substance use disorder treatment block grants, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) encourages its medical centers to provide free space for onsite legal care. In addition, Medicaid is now offering innovative finance opportunities for medical–legal partnerships.

COMMUNITYRx: CONNECTING HEALTH CARE TO SELF-CARE

CommunityRx, explained Stacy Tessler Lindau, was developed with a round one Health Care Innovation Award from CMS, which came with expectations that innovations would lead to a sustainable business model. In this case, she said, that expectation led her to create NowPow, a for-profit technology company, and MAPSCorps, a nonprofit youth workforce development and community asset mapping company. CommunityRx, she added, is an intervention based on two theoretical frameworks: Anderson’s behavioral model of health services use and Grey and colleagues’ model of self- and family management.

During the CommunityRx innovation period, MAPSCorps employed 288 local youth from the South Side of Chicago to conduct a systematic census of more than 19,000 businesses and organizations operating in the community. Lindau and her colleagues built evidence-based algorithms and used computational phenotyping to create a mechanism by which health care professionals could prescribe community services in the same way they prescribe drugs, which is directly from the electronic health record (EHR) workflow. During the innovation period, CommunityRx software was integrated with three EHR platforms at 33 health care sites. More than 113,000 participants received more than 253,000 personalized referrals to more than 7,000 community resources. Lindau noted that one in five participants within 2 weeks of receiving a referral went to a place they had never been before, and 49 percent of the people used this information to help someone else (Lindau, 2019; Lindau et al., 2016, 2019). Currently, three trials of CommunityRx are ongoing (see Table 5-2).

Community is an important factor affecting translation of this intervention, said Lindau. In her experience, clinicians are end users, but it is administrators who are doing the intake of technology-based solutions, so those two groups need to come closer together. She said,

In health systems where clinicians are working with information technologies in a tightly coupled way with administrator or operations professionals, we are early adopters of implementing solutions to connect people to the research of our community and addressing the issues we have been talking about today. When we are not talking to each other, we are laggers.

TABLE 5-2 CommunityRx Trials Under Way

| Targets | Population | Setting | Region | Design | Funder | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCS | CVD risk (N = 226 practices) | Small primary care practices | Midwest states | RCT | AHRQ Evidence Nowa | Dissemination |

| Research recruitment, enrollment | Patients eligible for asthma, COPD studies (N = 13,437) | Academic medical center | Chicago | Prospective implementation study versus usual practice | NIGMS CTSA (pilot)b,c | Dissemination |

| Food insecurity, self-efficacy, health, health care satisfaction | Caregivers of hospitalized children and children (N = 640) | Children’s hospital inpatient units | Chicago | Double blind RCT | NIMHD R01d | Starting |

| HRQOL, self-efficacy | Middle age, older Medicare/Medicaid recipients (N = 411) | Academic primary care and emergency medicine clinics | Chicago | Pragmatic trial, randomized by alternating calendar week | NIA R01e,f | ABM under way |

NOTE: ABCS = aspirin therapy, blood pressure control, cholesterol management and smoking cessation; ABM = agent-based model; AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HRQOL = health-related quality of life; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIGMS CTSA = National Institute of General Medical Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Award; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

a AHRQ R18HS023921 (A. Kho, Principal Investigator). AHRQ, 2019; Lindau, 2019.

b NIH CTSA Pilot 4UL1TR000430 (J. Solway, Principal Investigator; S. T. Lindau, Principal Investigator of Pilot). For information on the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program: https://ncats.nih.gov/ctsa (accessed August 7, 2019).

d NIH/NIMHD R01MD012630 (S. T. Lindau, Principal Investigator).

e NIH/NIA R01AG047869 (S. T. Lindau, Principal Investigator).

SOURCE: Presented by S. T. Lindau, April 26, 2019, at the Workshop on Investing in Interventions That Address Non-Medical, Health-Related Social Needs.

DISCUSSION

David Chokshi opened the discussion by asking the panelists to identify one barrier within the category of an evidence gap or policy gap that affects wider implementation of interventions that promise to address multiple social needs. Kangovi responded that what she has seen in working with thousands of organizations across the country is that many of them have community health worker programs or social determinants of health programs that they think are working but in fact are merely seeing regression to the mean. Programs need to be assessed using better evaluation methods. Regenstein agreed completely with that statement, and she added that the need to work across multiple professional cultures can also be a barrier. As an example, she noted that getting lawyers to think about social needs in the same way that health care organizations do is a difficult task that requires a great deal of training. Defining the problem to address, she said, depends on who is looking at the problem.

For Lindau, a barrier is the lack of knowledge about all the working pieces that come together to make a community and the assets that a community has with which to build a successful program. One policy she would recommend adopting would be that every community organization that receives funding, whether from government or philanthropy, should meet certain infrastructure standards, such as having a full presence on the Internet and an Internet connection to make them easier to find—this would require a shift away from allowing nonprofits to be funded without appropriate coverage of critical overhead costs.

Szanton pointed to the “wrong pockets” problem—organization A might invest the money, but organization B reaps the benefits at some point in the future—as a significant barrier to investing in successful programs. As an example, she noted how CAPABLE pays for the handyman’s work and the nurse and occupational therapist visits, but the resulting savings go to Medicare and Medicaid. In the ideal situation, CMS would pay upfront for CAPABLE’s services. In contrast, the VA can invest in programs knowing that it will reap the savings down the road because it keeps its patients for life.

Lindau, responding to a question about how to expand programs and policies nationwide, suggested the field should operate on the principle of inclusive growth. “As we grow health care from a sick care system to a well care system, we ought to think carefully about how we create opportunity across all sectors, especially those smaller community-based organizations that have been doing this work forever, to be part of the solution not get pushed out of the solution,” she explained. Kangovi agreed and added the importance of including community health workers in any solution because they are likely to be closest to the individuals these programs are meant to help. Regenstein added that an important

question to ask patients is whether they can afford their medications or if they have other financial stresses.

Chokshi asked the panelists if they are confident or skeptical that value-based payments will help increase investments in interventions that address social needs. Szanton said she is optimistic based on developments such as Medicare Advantage plans now having the capability to add programs such as CAPABLE and the need for savings in Medicaid programs. Lindau said that she believes that economic incentives work, and she sees that happening today based on the fact that for the first time in her many years as a practicing physician, she and her colleagues are talking regularly about how to keep people healthy outside the doctor’s office instead of focusing solely on treating people when they are sick. For her, the shift to value-based payments is critical to a system of caring for the whole person.

One change Lindau said she would like to see is for the human and social services sectors to move from the pencil-and-paper era to the digital economy. Health care was slow to make this shift too. Accomplishing this shift would likely require a carrot-and-stick approach, similar to electronic medical record and digital prescribing adoption policies. Uche Uchendu commented that value-based payments are a good start, but they only hold a limited number of people—all in health care—accountable. In her opinion, there is a need for some mechanism to broaden accountability and create a bridge between health care and community-based services. Lindau responded that NowPow, along with many other companies, are trying to build that bridge in order to make digital communication routine across all sectors of what she calls the caring community.

Mita Goel from Northwestern University and the National Collaborative for Education to Address the Social Determinants of Health noted that most of the programs discussed so far have the clinical encounter as the entry point. She wondered how the panelists’ programs were preparing the health care workforce to recognize in a systematic fashion when an individual has unmet social needs and connect them to the necessary services. Regenstein responded that training is a big part of the medical–legal partnership. Program lawyers talk to health care system staff about the importance of screening and recognizing when there is a social need that legal services could resolve. She noted that the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center trains all of its residents how to work with the institution’s medical–legal partnership.

Kangovi said that IMPaCT has training programs for health professionals that it has scaled across the country, as well as a program in which medical and nursing students apprentice for 2 to 4 weeks with community health workers to learn how to recognize the social determinants of health. Lindau added that health care professionals identify people’s

unmet needs all the time, but what they lack is a high-quality, respectful, and reliable process for acting on those unmet needs. To her, the way to deal with that is to incorporate the process for referring patients to services into the standard workflow through the EHR. CAPABLE’s “secret sauce,” said Szanton, is its use of motivational interviewing to elicit patient goals and to identify an individual’s strengths and assets to draw upon when addressing that person’s needs.

Chokshi noted this is a time of growing income inequality and other structural issues that contribute to the multiple social needs these programs are trying to address. His question to the panelists was whether those structural or policy issues are beyond the scope of interventions designed to address multiple social needs. Szanton said the community at large should be working on these structural issues, but every individual needs to work on an aspect that fits their personality and skills. Regenstein said this comes down to deciding how much responsibility the health care system or the individual provider has for individuals once they leave the hospital or doctor’s office. To her, it is “penny wise and pound foolish” to invest in caring for someone in a clinical setting and not look at the whole person, which is why health care is working on solutions that extend beyond their physical walls even though the health care system may not be the most logical place from which such programs should originate.

Lindau, returning to her earlier comment on the need to bring the human and social services sectors into the modern digital economy, said that if the sectors had the resources to make transparent their full inventories of programs and services, then health and human services work-flows could be connected digitally. The result would be digital evidence of transactions that are currently invisible to the 21st-century economy because they are on paper. Digitizing the work of connecting and communicating across the sectors generates data that are essential to understanding the demand for these services, supply of and gaps in these services, and for making data-driven decisions and investments in our communities. “With these powerful data,” she said, “we are in a position to advocate far more effectively for remedies that address true social and structural determinants of health.”

Responding to a question about expanding these programs to rural or smaller metropolitan areas, Kangovi said the IMPaCT program works well in rural areas and was designed deliberately to be a universally adaptable model that can operate in a variety of environments. Medical–legal partnerships, said Regenstein, are highly customized to involve lawyers who work in close proximity to a health care organization, which means that they are challenging to establish in rural communities given there is less legal capacity there. She noted that her center is trying to

work with primary care associations and other groups to stretch the available resources in smaller or rural communities. Lindau mentioned the Healthy Hearts in the Heartland program, which focused on providing tools that small primary care practices could use to connect patients to community-based resources that would prevent cardiovascular disease. A main barrier to success, she said, was a lack of capacity in these small practices to integrate new uses of electronic medical record systems.

Chokshi concluded the discussion period by asking each panelist for one key point regarding what is needed to move interventions that address multiple social needs forward. Szanton replied that physical function is important and modifiable, and the way to get at that is to ask people what they would like to be able to do. Lindau said that the field needs to elevate its attention to detail around the vital assets of communities to at least the same level that it pays to pharmaceuticals. “Community drives health, drugs do not,” she said.

Regenstein’s key point was that law is a social determinant of health, so adding legal competence to a health care team can sometimes unlock great benefits for patients. Kangovi said that science should be used to first channel the voices of people who are often not heard and then use those voices to inform the design of interventions that should be tested in the same way drugs and medical devices are tested, with implementation science being used to scale a successful intervention.

This page intentionally left blank.