5

The Effects of Children’s Circumstances on Summertime Experiences

In order to examine the availability and accessibility of summertime experiences for the nation’s 56.6 million school-age children and youth (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019), it is helpful to first understand some key characteristics of this population and the settings that shape their experiences throughout the year. In this chapter, therefore, we review the contextual and individual factors that affect their summertime experiences, including family structure, parental influence, and community environments (see Box 5-1).

We first briefly describe the demographic characteristics of where children, youth, and their families live and how these demographic trends are changing. We then examine how community contexts and children’s circumstances may affect children’s summer experiences, both generally and in connection with such specifics as safety, health, social and emotional development, academic learning, and opportunities for enrichment. Special attention is given to variations around racial, cultural, ethnic, and other individual attributes. This review places emphasis on the concepts of disparity, equity, and multisectoral interactions (i.e., complex social-ecological systems) for understanding the systemic factors that produce and perpetuate inequitable outcomes during the summer.

WHERE CHILDREN AND FAMILIES LIVE

According to surveys by the Pew Research Center, for a majority of Americans across community types, living in an area that is a “good place to raise children” is a high priority. About 6 in 10 Americans in urban areas (57%), suburban areas (63%), and rural areas (59%) say it is very important to them, personally, to live in a community that is a good place to raise children. Smaller shares say the same about living in a place with access to recreational and outdoor activities (42% overall), where they have family nearby (38%), and where there is a strong sense of community (27%) (Pew Research Center, 2018a).

Demographic trends for children and families have been shifting in recent years (see Table 5-1), but these changes are manifesting differently in the nation’s rural, suburban, and urban communities. In recent decades, the flow from central cities and rural areas to suburban areas has led to

| Population, 2000 (millions) | Population 2012–2016 (millions) | Change (%) | Proportion of Total Population (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 87 | 98 | 13 | 31 |

| Suburban | 150 | 175 | 16 | 55 |

| Rural | 45 | 46 | 3 | 14 |

SOURCE: Pew Research Center (2018b).

suburbanites now accounting for more than half of the U.S. population (Burdick-Will and Logan, 2017; Lichter and Brown, 2011).

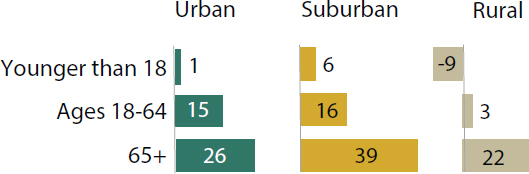

Total populations in rural, suburban, and urban communities are growing (albeit at different rates), but trends for the population under age 18 reveal a different story (see Figure 5-1). Rural populations may have less of the total population than suburban and urban communities, but within rural communities, children and youth under age 18 represent nearly the same proportion of the population—between 22 and 23 percent—as in other county types (Pew Research Center, 2018b). In 2016, about 13.4 million children under age 18, out of a total 74.2 million in the United States, lived in rural areas (Census Bureau, 2016). In recent decades, the flow from central cities and rural areas to suburban areas has led to suburbanites now accounting for more than one-half of the U.S. population (Burdick-Will and Logan, 2017; Lichter and Brown, 2011). Poor and minority families are moving into suburban neighborhoods at increasing rates. By 2008, the poor population in the suburbs was growing faster than in the cities or rural areas. Immigrants are also moving directly into suburban and rural areas (Burdick-Will and Logan, 2017; Ehrenhalt, 2012; Kneebone and Garr, 2010; Lichter and Brown, 2011).

Of the country’s 25.8 million elementary public school students, approximately one-half go to school in the suburbs, a little under one-third attend urban schools, and 15 percent attend schools in a rural area. Unsurprisingly, there are stark differences between these groups. Overall, the proportion of White students grows substantially the farther schools are located from the urban core. There is a steep urban-to-rural decrease in Black and Hispanic students and a sharp increase in American Indian students. Free and reduced-price lunch eligibility, on the other hand, is lowest in suburban areas (42.8%), and it is only slightly lower in rural areas (58.0%) than in urban ones (62.5%) (Burdick-Will and Logan, 2017).

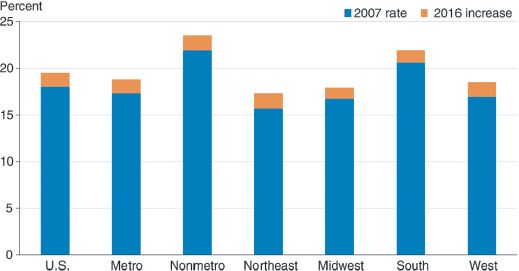

Children in poverty still tend to live in rural (“nonmetro”) counties—many with persistently high poverty (see Figure 5-2). Child poverty rates

SOURCE: Pew Research Center (2018b).

SOURCE: Farrigan (2018).

continue to be highest in the South and Southwest, particularly in counties with concentrations of Native Americans and along the Mississippi Delta. In 2016, 23.5 percent of rural children were poor, compared with 20.5 of urban (metro) children (Farrigan, 2018).

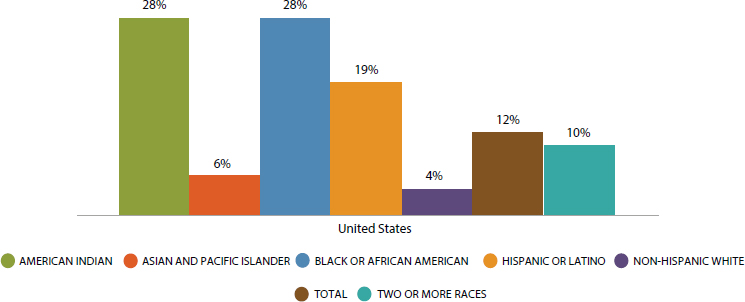

Across the country, 14 percent of children are now living in high-poverty communities (see Figure 5-3), up from 9 percent in 2000 (Kids Count Data Center, 2017a). Residents of these neighborhoods contend with poorer health, higher rates of crime and violence, poor-performing schools, and limited access to support networks and job opportunities.

NOTE: In this figure, areas of concentrated poverty are defined as those census tracts with overall poverty rates of 30 percent or more.

SOURCE: Kids Count Data Center (2019).

They also experience higher levels of financial instability (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2018).

The outcomes associated with living in areas of concentrated poverty are well documented and extend to nonpoor as well as poor residents of these communities. These outcomes include diminished school quality and academic achievement; diminished health and health care quality; pervasive joblessness, employment discrimination, and reduced employment networks; increased crime, especially violent crime; declining and poorly maintained housing stock and devaluation of home values; and difficulty building wealth and experiencing economic mobility. Compounding these problems, individuals living in poverty-saturated areas are less likely than others to live in the vicinity of nongovernmental social service organizations, proximity to which is a key factor in service utilization. Poor individuals who live in more-advantaged areas are, in some respects, safeguarded from the most negative impacts of poverty (Meade, 2014).

Disparities in neighborhood environmental conditions among racial and ethnic groups contribute to inequities in health outcomes and economic opportunity for children and youth over the course of their lives (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2014; Chetty et al., 2016). For example, chronic stress and adversity in childhood, such as chronic exposure to neighborhood violence, poverty, and discrimination, can have negative, persistent, and cumulative effects on neurological, physical, and psychosocial development (Shonkoff et al., 2009). Consequently, improving the economic and safety conditions of neighborhoods where children live could reduce exposure to chronic stress and, in fact, such improvements have been associated with improved health outcomes over the life course for some populations (Chetty et al., 2016; Ludwig et al., 2011). Housing mobility, urban planning, and community development policies may mitigate disparities by supporting healthy community development, access to educational opportunity, access to healthy foods, and safer neighborhoods (Ludwig et al., 2011; Pollack et al., 2014; Thornton et al., 2016).

The Child Opportunity Index is a nationally available population-level measure that looks at the neighborhood environments of children in the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the United States. This index shows the extent of racial/ethnic inequity among children across levels of “neighborhood opportunity”—that is, neighborhood-based conditions and resources that promote healthy child development. Using 19 indicators in three domains of opportunity (educational, health/environmental, and social/economic), this measure focuses on neighborhood factors that impact child development (see Box 5-2). It also provides a window into the context of neighborhood conditions and resources that may affect the availability,

quality, and variety of summer opportunities available to children and youth in ways that further exacerbate inequities.

Data from this index demonstrate pervasive inequities across the three domains measured, highlighting the differences in exposure to risk and protective factors that children and youth in the United States encounter. The disproportionately high concentration of Black and Hispanic children in the lowest-opportunity neighborhoods is a pervasive issue across U.S. metropolitan areas, with 40 percent of Black children and 32 percent of Hispanic children living in very-low-opportunity neighborhoods, as compared to 9 percent of White children. This inequity is even more extreme in some metropolitan areas, especially those with high levels of residential segregation (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2014).

HOW DO COMMUNITY AND FAMILY CONTEXTS AFFECT THE SUMMERTIME EXPERIENCES OF CHILDREN AND YOUTH?

Socioeconomic Status, Family Structure, and Composition

Summertime experiences across youth populations vary by social and economic circumstances, with consequences for children’s healthy development that can be long-lasting. American youth have a substantial amount of discretionary time when not in school (Mahoney et al., 2005), yet the summertime experience of many children is not characterized by a healthy balance of structured vs. unstructured and self-directed activities in organized programs with a range of other family, peer, and self-directed experiences (see Chapter 2 more in-depth discussion). Therefore, it is critical to acknowledge factors within a young person’s family and environment that can impact their experiences during the summer months. These contextual factors are explored in the section that follows.

There is a high demand for summer programming among families living in rural, urban, and suburban high-poverty neighborhoods. More than 4 in 10 parents living in areas of concentrated poverty (41%) report that their child took part in a summer learning program, a rate that is 8 percentage points higher than the national average (33%) (Afterschool Alliance, 2016). Despite this level of participation, there is considerable unmet demand within these communities. Furthermore, the committee suspects that there may differences in the type and quality of programming available to children living in concentrated poverty and low-opportunity neighborhoods (refer to Box 5-2) such that it is qualitatively different from the programming available to children and families with more economic resources or who live in neighborhoods of opportunity.

Family poverty can harm children’s healthy development insofar as it affects access to resources, and “families who occupy different SES niches because of parental education, income, and occupation have strikingly different capacities to purchase safe housing, nutritious meals, high-quality child care, and other opportunities that can foster health, learning, and adaptation” (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000, p. 268). For example, children in poverty are much more likely than other children (59% vs. 39%) to have a mother who works a non-daytime work shift outside the typical 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. schedule (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000, p. 273).

Children living in poverty are also likely to have a greater than average need for high-quality summertime experiences that provide opportunities for healthy development, but they may be less likely to have access to such experiences and opportunities as a result of economic barriers. Families with higher incomes spend significantly more on goods and ser-

vices aimed at enriching the experiences of their children than families with lower incomes: in 2005–2006, those in the highest income quintile on average spent $7,000 more than those in the bottom quintile, with the differences most pronounced for activities such as music lessons, travel, and summer camps (Duncan and Murnane, 2011, p. 11). Across the board, families are spending more money on children than they formerly did, measured as a percentage of total income, but high-income families spend more than twice as much, on average, as low-income families. Such differences contribute to significant inequalities in access to summertime opportunities across the income spectrum (McLanahan and Jacobson, 2015).

The average cost of summer programs can be viewed in the context of varying household incomes. For example, the average reported cost of a summer program nationally in 2014 was $288/week (Afterschool Alliance, 2015).1 According to the 2018 Federal Poverty Guidelines, a family of four living at 100 percent of the poverty level has $25,100 in yearly income or approximately $483/week. As this comparison of the cost of 1 week of summer programs and the weekly income of a family living at poverty level shows, for many families it is virtually impossible to involve their children in a summer program with average costs.

Because so many children in the United States are growing up in poverty, this cost presents a significant barrier to access. Estimates suggests that greater than 30 percent of children in the United States live in poverty or near-poverty (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019a). This is corroborated by research from the Pew Research Center, which found that approximately 25 percent of parents report barely making ends meet basic expenses, while another 9 percent of parents report being unable to meet their family’s basic needs (Pew Research Center, 2015). Many of these parents are included among the working poor—the majority of children in low-income families have at least one parent who is working full time (National Center for Children in Poverty, 2018).

The proportion of children living in single-mother, female-headed households is increasing, and the largest part of this increase is among children in low-income families. These mothers are younger and have lower workforce participation rates than high-income mothers, which further contributes to economic disadvantage (Center for American Progress, 2019). The proportion of children in single-parent households is substantially higher for Black children and American Indian children than for other racial subgroups (Kids Count Data Center, 2017b). Children growing up

___________________

1 A more recent 50-state analysis by the Center for American Progress (Novoa, 2018) estimates that the typical family would pay $3,000 for 5 weeks of summer care for two children.

in single-parent families typically have access to fewer economic resources and less of the valuable time spent with adults than children in two-parent families, where parenting responsibilities can be shared. Other research suggests that children take on more family responsibilities and spend more time on household chores in the summer when they live with single parents (Hofferth and Sandberg, 2001; Ribar, 2015).

Family size too can influence the experiences a child has during the summer months. For example, smaller families may have more resources in both time and money to support summer enrichment or leisure activities, as they have fewer children to support financially; however, in smaller families, children lack siblings with whom they can play (Hofferth and Sandberg, 2001). Other research supports differences in summertime opportunities based on family size. For example, in a nationally representative survey of 1,250 individuals ages 15 or older, Mowen and colleagues (2016) found that respondents with three or more people in their household were more likely to live within walking distance of a park, suggesting that park-based experiences are more available to larger families.

It is also important to note that some children are living outside of their biological or extended family context due to circumstances such as homelessness or foster care placement. Other children are living outside of their homes or in situations separated from their parents as a result of juvenile justice system involvement. These children may be the most at risk of adverse outcomes, and summertime may represent a unique opportunity for targeted programming or intervention; however, there is little existing research on summer-specific experiences of these populations (see Box 5-3).

Parental Involvement

The extent to which parents are involved with their children or value parent involvement is another factor that can influence children’s summertime experiences (Gershenson, 2013). Providers of summertime programs for children have highlighted parent engagement as a priority (Garst et al., 2016; Roth, 2018); however, parents may not all view parental involvement in the same way (Lareau and Weininger, 2008). For example, parents from high-income households may be more likely to believe that parental involvement is important for supporting their child’s participation in summertime experiences when compared to parents from low-income households (Entwisle et al., 2001).

Employment status may also affect parents’ involvement in the summertime experiences of their children. Children of employed parents, particularly employed mothers, are more likely than are children of unemployed mothers to be involved in daycare throughout the year (Hofferth and

Sandberg, 2001). Similarly, employed parents may have fewer opportunities than unemployed parents to spend time in less structured activities with their children, and as a result their children tend to have more structured summers that fit into working parents’ schedules (Hofferth and Sandberg, 2001). One might therefore expect children of employed parents to spend more time in structured activities in summertime as well, particularly if their mothers are employed. Other factors, such as parents’ language, culture, or immigration status, may also be important considerations that impact children’s summertime experiences.

Children in many rural communities experience very limited access to summer programming for a variety of reasons, including difficulty for parents and caregivers to offer supervised time while also working, limited programmatic offerings, and geographic isolation. The isolation of youth is an important recurring problem in the summer for rural youth, who may have very limited contact with adults other than their caregivers. These barriers limit access to many summertime experiences for children and youth in rural communities.2

Juvenile and criminal justice system involvement and incarceration also affect parental involvement. Estimates for 2010–2011 indicate that more than 5 million children in the United States experienced the incarceration of a parent (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2016). Between 1991 and 2007, the number of children whose mothers were incarcerated increased by more than 130 percent (Goshin, 2015). Point-in-time estimates suggest that the mothers of more than 145,000 children are incarcerated in the United States on any given day (Goshin, 2015). Despite similar crime rates, juveniles and adults living in communities of color are far more likely to be incarcerated than their White peers (Child Trends, 2016; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2001; The Sentencing Project, 2017).

Differences in families based on racial, ethnic, and cultural background can also influence the types of summertime experiences in which children engage. For instance, concerning free-time activities, Hofferth and Sandberg (2001) found that Black and Asian children watched much more television than White (non-Hispanic) children. Although research across disciplines related to the outcomes of interest for this report documents or describes differences in specific behaviors or preferences, the extent to which these differences are motivated by intrinsic cultural factors alone is unclear. Further, families from racial and ethnic minority and/or lower-income backgrounds report having less access to high-quality after-school programming (Afterschool Alliance, 2014). This may further increase dispari-

___________________

2 Comments made by Jocelyn Richgels of the Rural Policy Research Institute at a public information-gathering session held by the Committee on Summertime Experiences and Child and Adolescent Education, Health, and Safety on September 19, 2018.

ties in educational and psychosocial outcomes apart from any difference in cultural predisposition

Safety

Three aspects of safety during children’s and youth’s summertime experiences merit special attention: the role of parental supervision and interaction, the effects of neighborhood environment, and the nature of policing. We discuss these in turn, next.

Parental Supervision and Interaction

The extent to which children are supervised during the summer—a factor closely related to household income—is another major consideration with regard to children’s summertime experiences. For example, Redford and colleagues (2018)3 found that children from poor households (83%) were more likely than children from nonpoor households (70%) to have irregular care and supervision during the summer. In other words, families of children living in poverty had less capacity to provide supervision directly or to connect with other sources of reliable and consistent supervision. Gershenson (2013) found that children from lower-income households spent less time in conversation with their parents and more time watching television in the summer. Specifically, this research found that children in low-income households watched an average of almost 2 more hours of television per day during the summer when compared to children in higher-income households.

Neighborhood Safety

Parents, children, and youth all view neighborhood safety as an important consideration during the summer (Worobey et al., 2013). Although violent crime has been decreasing over the past two decades, crime is still disproportionately concentrated in communities of disadvantage. Children and youth who are exposed to violent crime may experience adverse stress responses, which can raise their risk of suffering future health conditions in adulthood (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019b).

Both actual and perceived safety within neighborhoods affect how far children venture from home and how they spend their time outdoors (Villanueva et al., 2012; Worobey et al., 2013). Crime, high-volume traffic,

___________________

3 Study of a nationally representative sample of 18,170 children ages 5–6 from 1,310 schools, mentioned in Chapter 2.

and poorly maintained neighborhoods (e.g., litter, broken windows) are among the many neighborhood factors associated with reduced time spent outdoors by people living in lower-income communities (Taylor and Lou, 2011). A study of two low-income neighborhoods in New Orleans looked at the impact of having open and supervised school playgrounds during out-of-school time and summer. The study found that attendance was 84 percent higher at the open and supervised playground compared to the playground without adult supervision. In addition, children who utilized the supervised playground reported less time spent indoors watching television or playing video games (Farley et al., 2006). Another study, which looked at youth in Boston, found that on average playgrounds in areas with greater proportions of youth living in poverty were less safe (Lopez, 2011). In their study of children ages 10–12, Villanueva and colleagues (2012) found that in cases where their parents reported living near a busy road, foot travel by children and youth within their neighborhoods was reduced compared with those not living near a busy road. A 2000 study of children’s perceptions of their neighborhoods found that children living in neighborhoods with a high incidence of violence did not feel safe playing outside and had less trust in law enforcement (Farver et al., 2000).

Policing

According to data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, between 15 and 26 percent of American youth have been arrested by age 18 (Brame et al., 2012). An analysis of more recent population-based data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study examined contemporary urban teens around their 15th birthday and found that, at this age, police contact is prevalent and that racial/ethnic minority youth, particularly boys, face qualitatively different forms of police contact from that faced by their white counterparts (Geller, 2018). Black, Latinx, and multiracial youth experience significantly more intrusive police encounters, such as frisks, searches, and handcuffing, and have significantly more police contact at school. Key results indicate that approximately 25 percent of boys, including 39 percent of Black boys, report having been stopped by the police.

A recent study by Del Toro and colleagues (2019) found that high rates of contact with law enforcement among Black and Latinx boys as a result of proactive policing was a predictor of decreased psychological well-being with the potential to increase the likelihood of their participation in criminal behaviors—especially when these contacts occurred earlier in life. Delinquent behavior was not a predictor of subsequent police stops by the youth in the study; however, frequent police stops were predictive of increased delinquent behavior resulting from psychological distress among

study participants. Law-abiding youth were not found to have a decreased likelihood of being stopped by police. More work is needed to examine differences in the effects of police contact among youth of different races, as well as youth from marginalized groups beyond racial minorities that have been shown to be heavily policed, such as LGBTQ youth (see Box 5-4) (Mallory et al., 2015) and youth with disabilities (U.S. Department of Education, 2018).

Despite their frequent contact with youth (ages 12–24), law enforcement agents/personnel typically receive little training in how to manage encounters with youth or in adolescent development. The police training that does exist varies widely, ranging from just 2 hours in five states to 20–24 hours in two states (Florida and the District of Columbia) (Thurau, 2013), and it tends to focus on the juvenile legal code rather than on youth development or youth psychology (Thurau, 2009).

Attitudes toward the police generally correlate with the frequency of police contacts, such that those groups that have the most contact with

police tend to have less favorable attitudes toward the police, as do students who reported living in less safe neighborhoods or neighborhoods in which crime was a problem (Sanden and Wentz, 2017, p. 420). Although there is much less literature on policing in rural settings, the existing research suggests that youth in small rural and suburban settings tend to have more favorable attitudes toward the police than youth in urban areas (Hardin, 2018).

There is a broad range of potential engagement opportunities for law enforcement interacting with youth in urban neighborhoods that experience a significant police presence that might help improve relationships between communities and police and decrease negative interactions. One approach would be to invest in “buffers and bridges” for youth in these neighborhoods (Jones, 2018). “Buffers” act as intermediaries between the police and young people, while “bridges” facilitate the movement of young people from contexts of violence or over-policing to pro-social community and neighborhood settings. Buffers and bridges should be built for all youth, and especially for those youth most likely to engage in or become victims of violence (Bostic and Buckley, 2012).

Health

Maintaining basic health in the summertime, as during the rest of the year, requires adequate nutrition and adequate physical activity. In this section we look more closely at trends in these areas as well as disparities in access to the resources that make physical activity and a healthy diet possible.

Physical Health

Obesity. In the United States, the percentage of children and adolescents affected by obesity has more than tripled since the 1970s. Data from 2015–2016 show that nearly one in five school-age children and young people (ages 6–19) in the United States has obesity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018a). Childhood obesity rates are higher among certain populations, specifically among Hispanic children (26%) and non-Hispanic Black children (22%), as compared to non-Hispanic White children (14%) (Hales et al., 2017). Childhood obesity prevalence also varies by income and education (Ogden et al., 2018). Social and structural factors such as differential access to clean water, violence-free neighborhoods, law enforcement contact and surveillance, safe outdoor play areas, high-quality enrichment activities, adequate healthy food, and other environmental features shape the environments in which children and youth live and can lead to disparities in outcomes.

Physical Activity. Regular physical activity in childhood and adolescence is important for promoting lifelong health and well-being and preventing various health conditions. Less than one-quarter (24%) of children and youth ages 6–17 in the United States participate in 1 hour of physical activity every day (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018b). Structural factors such as walkability, access to recreational facilities, population density (see Box 5-5) (Ding et al., 2011), and crime rates (Kneeshaw-Price et al., 2015) may also influence time use in ways that impact child outcomes by reducing children’s and youth’s outdoor physical activity.

Many low-income communities and communities of color lack the features that promote physical activity and can help prevent childhood obesity, such as bike lanes, sidewalks, safe playgrounds, trees, and appeal-

ing scenery. In addition, lower-income communities and racial and ethnic minorities are less likely than others to have access to such amenities as parks and recreational centers and thus are less likely to be active (Taylor and Lou, 2011). A 2006 study that examined a nationally representative cohort of adolescents found that adolescents from lower-income or racial and ethnic minority neighborhoods were half as likely to live near recreational facilities (either public or private) as other adolescents and that this was associated with decreased physical activity and increased incidence of overweight (Gordon-Larsen et al., 2006).

Population density also affects access to opportunities for physical activity and access to adequate nutrition (refer to Box 5-5). In rural communities, where there may not be enough residents to support new rec-

reation infrastructure and where there are structural barriers to physical activity, schools are often among the few spaces outside of the home where children and youth can be active. There are opportunities for communities to work together with schools and utilize existing infrastructure and to adapt programs such as Safe Routes to School that fit community needs (Dalton et al., 2011; Safe Routes to School National Partnership, 2015; Young et al., 2014). However, staffing, maintenance, safety concerns, and cost may be barriers to keeping schools available outside of normal school hours for some communities (Cox et al., 2011).

Food Insecurity. Children in the United States are exposed to higher rates of food insecurity than the overall population. In 2016, 18 percent of children under age 18 (more than 13 million children) lived in food-insecure households. Food insecurity is more common in low-income households. Along racial lines, household food insecurity was almost twice as prevalent in 2016 among children in households headed by non-Hispanic Black (26%) or Hispanic (24%) parents than in those headed by non-Hispanic White (13 percent) parents. Additionally, the prevalence of household food insecurity among children was three times as high in households headed by single women as in those headed by married couples (33% and 11%, respectively) (Child Trends Databank, 2018). Food insecurity tends to be more prevalent in households with older children: 18 to 19 percent of households with school-age children (ages 5–17) are food-insecure, compared with 14.5 percent of households with children ages 0–4 (USDA, 2017).

As previously mentioned in this report, children and youth in low-income communities often experience food insecurity during the summer. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Summer Food Service Program (SFSP), which was created to fill the gap in access to food between school years, provides meals to students to promote their health and well-being. However, SFSP consistently has difficulty meeting the needs of eligible children, serving only one in seven students who receive free and reduced-price lunch during the school year (Food Research & Action Center, 2018). A key barrier to increasing participation in SFSP is insufficient public and private funding for those summer programs that could serve as feeding sites for it as well as providing some form of enrichment. In addition, eligibility criteria for communities to participate in the program require at least half of the children in the area to be low-income. Thus, in areas where poverty is less concentrated or in rural communities, it may be difficult to establish feeding sites (Food Research & Action Center, 2018).

Children with Special Health Care Needs

As of 2016, an estimated 14.2 million children, or 19 percent of all children in the United States, have special health care needs,4 increasing from 13 percent in 2001. Their needs result from a range of conditions, including Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and autism. They may require services such as nursing care to live safely at home, therapies to address developmental delays, or mental health counseling. Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) covered about half (48%) of children with special health care needs in 2016 (Musumeci and Foutz, 2018). One in four non-Hispanic Black children and youth have special health care needs, as reported by their parents, which is 5 to 15 percentage points more than any other major racial or ethnic group. A lower percentage of Hispanic children and youth have special health care needs, but the reported prevalence among this group rose between 2009–2010 and 2016, from 11 to 17 percent. Non-Hispanic Asian children and youth were the least likely to have special health care needs, at 10 percent (Child Trends, 2019).

Children and youth with special health care needs have chronic health conditions—physical, mental, and developmental—that require services beyond what most children generally require and have implications for summertime experiences (Family Voices, 2019; McPherson et al., 1998). Despite federal laws protecting children and youth with special health care needs, summer educational programming for them is highly variable. Unlike during the school year, federal laws intended to protect these children (along with children with disabilities) do not insure their right to receive any specific services or programming during the summer. This means that, among other challenges, barriers to physical access for children with physical limitations can limit their access to and participation in certain types of recreational experiences.

Transportation challenges can limit opportunities for children and youth with special health care needs when summer programs lack appropriate equipment for securing wheelchairs or summer recreation destinations are inaccessible to those with physical disabilities. For children with significant nursing or home health needs, the summertime puts additional burdens on caregivers when school is out, which can mean inconsistency in home health caregivers over the summer. For families with limited economic resources or inflexible work hours, these are major concerns and can have detrimental impacts on the social, emotional, and cognitive development of their children and youth with special health care needs.

___________________

4 According to the U.S. Department of Health and Social Services, these children “have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions and also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019).

For these children, the challenges to accessing high-quality summertime experiences may be exacerbated if they live in rural communities or belong to low-income families, racial/ethnic minority groups, immigrant families, or families that primarily speak a language other than English.

Health Care Disparities

Research into health disparities and health equity has similarly identified a need to address cultural appropriateness and bias in health care. Addressing bias among health and social service professionals has been identified as an important component of comprehensive efforts to address disparities and inequities in health and health care that manifest along racial/ethnic or cultural lines (see Box 5-6) (Betancourt et al., 2005; Dovidio and Fiske, 2012; Institute of Medicine, 2003; Van Ryn and Fu, 2003).

Work in this field increasingly connects health care disparities to social conditions, and persistent disparities for non-White groups in particular (Zimmerman and Anderson, 2019). In an evaluation of 25 years of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Zimmerman and Anderson (2019) looked at health equity across four measures: disparities across income groups; disparities between Black and White populations; correlation of health outcomes with income, race/ethnicity, and gender; and a summary health equity metric. Findings from this study found that despite improvements in the Black-White gap, there has been an overall lack of progress in achieving health equity.

Social and Emotional Development

As discussed in Chapter 3, there is a lack of research on seasonal trajectories of social and emotional learning and skill development. This makes it difficult to pinpoint the specific effects of family and community influences on youth social and emotional learning during the summer months. However, there is some literature from which we can infer how these influences may operate during summertime.

As noted earlier in the report, disparities have been documented in the social and emotional skills that children have when they first enter formal schooling, disparities that track with socioeconomic status and related social conditions (Greenberg and Weissberg, 2018; Halle et al., 2009; Reardon and Portilla, 2016). Thus, it is important to consider how the social conditions related to socioeconomic status may impact social and emotional skill development. As noted previously, the effects of social conditions may be exacerbated in the summer months for youth from communities with higher levels of stressors and fewer opportunities for enriching programs or activities.

A 2019 National Academies report on adolescence found that high levels of stress have a negative effect on children’s brain development and that children from low-income and minority families are more likely to experience stress than children who are not (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019b). In addition, the socioeconomic status of parents was found to be a driver of parental stress, which can affect the ability of parents to mitigate the harmful effects of stress for their children. Thus, lower-income parents face not only a limited ability to make mone-

tary investments in their children but also challenges to delivering nonmonetary investments in them, such as quality time and caregiving (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019a). While social conditions may affect youth’s development of social and emotional skills, these skills also have important benefits for youth exposed to trauma and chronic stress, as social and emotional skills can help buffer the negative effects of stress and trauma (The Aspen Institute National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, 2019).

At the same time, it is important to keep in mind the ways in which gaps in social and emotional skill development may also reflect cultural bias, an issue raised in Chapter 3. For example, research has documented that teachers view the same behavior differently depending on who is displaying it, with harsher assessments of behavior for Black youth than for White youth (Carter et al., 2017; Gilliam et al., 2016; Okonofua and Eberhardt, 2015). This bias may then be reflected in teacher ratings of social and emotional skills in students, which are often used in studies of social and emotional skills in order to avoid self-report bias. At the same time, there is potential for social and emotional learning (SEL) to address rather than reify existing inequities if cultural issues are taken seriously. Jagers and colleagues (2018) coined the term transformative SEL to center issues such as power, privilege, social justice, discrimination, and self-determination within the field. They provide a thoughtful overview of the opportunities for equity to be addressed within core social and emotional competencies.

In their recent review of the evidence on SEL, Greenberg and Weissberg (2018) highlight the importance of a systems-level approach to social and emotional learning. This requires schools to have integrated and developmentally aligned SEL interventions and programs. But it also requires connections between schools, families, and communities to create a more equitable and systemic approach to supporting children and youth’s SEL.

Academic Learning and Enrichment

The frequently mentioned “achievement gap,” which refers to disparities in educational attainment and outcomes for youth from different social groups, persists. Although some narrowing has occurred over the past few decades in the racial academic achievement gap between Black and White students, disparities have actually widened in educational outcomes between youth from lower-income families and those from higher-income families (Reardon, 2013).

Family Characteristics

A parent’s level of education often reflects his or her own academic skills and the emphasis he or she places on academic learning, and therefore children of more educated parents may spend more time on activities such as reading and studying (Hofferth and Sandberg, 2001). Redford and colleagues (2018) found that children whose parents had a high school diploma or less (32%) were more likely to never use a computer for educational purposes during the summer than children whose parents had some postsecondary education (18%) or a bachelor’s degree (15%).

Research suggests a family’s economic resources also play a major role in the nature of summertime experiences for children. A 2017 RAND report found a growing gap in the amount spent on enrichment between families with higher incomes and those with low incomes (McCombs et al., 2017). The result is that without access to more sustained programming (Huggins, 2012; McCombs et al., 2011), many low-income youth will lose even more ground academically during the summer than their middle-income peers.

Redford and colleagues’ (2018) study showed that once children’s summertime experiences are categorized, differences emerge based on household poverty status and parents’ education (see Table 2-1 in Chapter 2). Although this study accurately represents the influence of household poverty status on children’s summertime experience, because it was conducted with children ages 5–6 some experiences may be less likely to be reported than others (such as overnight camp experiences, which are generally unavailable until a child turns age 8 or 9). Redford and colleagues’ research found that children from poor (81%) and near-poor households (82%) were less likely to participate in enrichment experiences such as visiting a beach, lake, river, or national park. Similarly, although 64 percent of children visited a zoo or aquarium, only 54 percent of children from poor households did so (for youth in near-poor households, the figure was 66%). In sum, when a child’s parents had a high school diploma or less, children were less likely to have access to enrichment opportunities. In the case of summer school, no differences were found based on household poverty status or parent education (Redford et al., 2018).

SUMMARY

The reviews and supporting evidence presented in this chapter provide a compelling case that family structure, parental education and employment, the built environment, community resilience and adaptive capacity, and public safety and law enforcement contact all affect summertime experiences for children and youth. Moreover, these elements interact dynamically and have both immediate and delayed effects on learning, health, and social and emotional development.

Summer-specific data are sparse in many areas, and gaps in knowledge have been identified throughout the chapter. Nevertheless, available data make it clear that opportunities are severely restricted for many children and youth as a consequence of poverty, impoverished neighborhoods, geography, and deficiencies of the built environment. As a consequence of this ecosystem inequity, disparities in health and learning are perpetuated or exacerbated during the summer months for many children and youth. Conversely, strong families abound in disadvantaged and low-income communities, presenting assets that can be leveraged along with systemic and substantial investments to reduce poverty and improve system elements and programming for better outcomes in the health, academic learning, and social and emotional development of our children and youth.

CONCLUSIONS

CONCLUSION 5-1: Communities and families have existing resources and infrastructure that can be leveraged through partnerships to increase access to summer programs for children and youth.

CONCLUSION 5-2: Children who are poor or near-poor or live in geographies of concentrated disadvantage have less access to adequate nutrition and high-quality summertime programming that provide opportunities for healthy development in the summer.

CONCLUSION 5-3: Sources of risk (e.g., racial and ethnic discrimination, special health care needs, LGBTQ+ status, trauma history, justice or child welfare system involvement) can heighten inequities in access to summertime experiences that affect health, development, safety, and learning.

CONCLUSION 5-4: More children could have access to high-quality summer experiences if socioeconomic constraints and systemic obstacles that families face (e.g., limited economic means to devote to summertime activities and competing demands from employers) were reduced.

CONCLUSION 5-5: More research on disparities related to family socioeconomic status, racial/ethnic subgroup, family status, and geography is needed to inform policy initiatives that address inequitable access to quality summer experiences.

CONCLUSION 5-6: More research is needed that specifically examine summertime experiences and their distribution across children and

youth living in different types of family and community contexts, particularly underserved populations (e.g., children who are American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, immigrant, migrant and refugee, homeless, system-involved, LGBTQ, and those with special health care or developmental needs).

CONCLUSION 5-7: Systems where the state plays an active role of supervision or custodial responsibility for children and youth, including local policing systems and juvenile justice and child welfare systems, have an enhanced obligation to improve their practices by applying positive youth development principles in their interactions with children and youth.

REFERENCES

Acevedo-Garcia, D., McArdle, N., Hardy, E. F., Crisan, U. I., Romano, B., Norris, D., Baek, M., and Reece, J. (2014). The child opportunity index: Improving collaboration between community development and public health. Health Affairs, 33(11), 1948–1957.

Afterschool Alliance. (2014). America After 3pm: Afterschool Programs in Demand. Washington, DC. Available: https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/documents/America-After-3PM-Afterschool-Programs-in-Demand.pdf.

_____. (2015). Summer Learning Programs Help Kids Succeed. Available: http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/documents/AA3PM-2015/National-AA3PM-Summer-FactSheet-6.11.15.pdf.

_____. (2016). Concentrated Poverty. Available: http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/aa3pm/concentrated_poverty.pdf.

Akee, R., and Simeonova, E. (2017). Poverty and Disadvantage Among Native American Children: How Common Are They and What Has Been Done to Address Them? Report prepared for the Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty by Half in 10 Years. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Available: https://www.nap.edu/resource/25246/Akee%20and%20Simeonova.pdf.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2011). Policy Statement: Healthcare for Youth in the Juvenile Justice System. Washington, DC: Author Available: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/128/6/1219.full.pdf.

Anderson, S., Rosso, R., Boyd, A., and FitzSimons, C. (2018). Hunger Doesn’t Take a Vacation: Summer Nutrition States Report. Washington, DC: Food Research and Action Center.

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2016). A Shared Sentence. Baltimore, MD: Kids Count. Available: https://www.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-asharedsentence-2016.pdf.

_____. (2018). 2018 Kids Count Data Book: State Trends in Child Well-Being. Available: https://www.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-2018kidscountdatabook-2018.pdf.

Baglivio, M., Epps, N., Swartz, K., Huq, M. S., Sheer, A., and Hardt, N. S. (2014). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. OJJDP Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2). Available: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/Prevalence_of_ACE.pdf.

Barnidge, E. K., Radvanyi, C., Duggan, K., Motton, F., Wiggs, I., Baker, E. A., and Brownson, R. C. (2013). Understanding and addressing barriers to implementation of environmental and policy interventions to support physical activity and healthy eating in rural communities. The Journal of Rural Health, 29(1), 97–105.

Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E., and Park, E. R. (2005). Cultural competence and health care disparities: Key perspectives and trends. Health Affairs, 24(2), 499–503. doi: 10.131377/hlthaff.24.2.499.

Bostic, J., and Buckley, P. P. (2012). Connecting the dots between conduct and goals: Why the ‘Scared Straight’ approach doesn’t work. The Journal of School Safety, 32–33.

Brame, R., Turner, M. G., Paternoster, R., and Bushway, S. D. (2012). Cumulative prevalence of arrest from ages 8 to 23 in a national sample. Pediatrics, 129(1), 21–27.

Burdick-Will, J., and Logan, J. R. (2017). Schools at the rural-urban boundary—Blurring the divide? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 672(1), 185–201. doi:10.1177/0002716217707176.

Calancie, L., Leeman, J., Jilcott, S.P., Khan, L.K., Fleischhacker, S., Evenson, K.R., Schreiner, M., Byker, C., Owens, C., McGuirt, J. and Barnidge, E. (2015). Nutrition-related policy and environmental strategies to prevent obesity in rural communities: A systematic review of the literature, 2002-2013. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12, E57.

Carter, P. L., Skiba, R., Arredondo, M. I. and Pollock, M. (2017). You can’t fix what you don’t look at: Acknowledging race in addressing racial discipline disparities. Urban Education, 52(2), 207-235.

Center for American Progress. (2019). Breadwinning Mothers Continue to Be the U.S. Norm. Available: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2019/05/10/469739/breadwinning-mothers-continue-u-s-norm/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018a). Childhood Obesity Facts. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/obesity/facts.htm.

_____. (2018b). Physical Activity Facts. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/facts.htm.

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., and Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 106(4), 855–902.

Child Trends. (2016). Juvenile Incarceration. Available: https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/juvenile-detention.

_____. (2019). Children with Special Health Care Needs. Available: https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/children-with-special-health-care-needs.

Child Trends Databank. (2018). Food Insecurity. Available: https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/food-insecurity.

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2017). Foster Care Statistics 2016. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. Available: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/foster.pdf.

Cocozza, J., Skowyra, K., and Shufelt, J. (2010). Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Youth in Contact with the Juvenile Justice System in System of Care Communities: An Overview and Summary of Key Issues. Washington, DC: Technical Assistance Partnership for Child and Family Mental Health.

Cox, L., Berends, V., Sallis, J. F., John, J. M. S., McNeil, B., Gonzalez, M., and Agron, P. (2011). Engaging school governance leaders to influence physical activity policies. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 8(s1), S40–S48.

Craigie, A. M., Lake, A. A., Kelly, S. A., Adamson, A. J., and Mathers, J. C. (2011). Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas, 70(3), 266–284.

Dalton, M. A., Longacre, M. R., Drake, K. M., Gibson, L., Adachi-Mejia, A. M., Swain, K., Xie, H., and Owens, P. M. (2011). Built environment predictors of active travel to school among rural adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40(3), 312–319.

Dank, M., Yu, L., Yahner, J., Pelletier, E., Mora, M., and Conner, B. (2009). Locked in: Interactions with the Criminal Justice and Child Welfare Systems for LGBTQ Youth, YMSM, and YWSW Who Engage in Survival Sex. Available: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/71446/2000424-Locked-In-Interactions-with-the-Criminal-Justice-and-Child-Welfare-Systems-for-LGBTQ-Youth-YMSM-and-YWSW-Who-Engage-in-Survival-Sex.pdf.

Del Toro, J., Lloyd, T., Buchanan, K. S., Robins, S. J., Bencharit, L. Z., Smiedt, M. G., Reddy, K. S., Pouget, E. R., Kerrison, E. M. and Goff, P. A. (2019). The criminogenic and psychological effects of police stops on adolescent black and Latino boys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(17), 8261–8268.

Deutsch, N. L. (2017). Construct (ion) and context: A response to methodological issues in studying character. Journal of Character Education, 13(2), 53–64.

Ding, D., Sallis, J. F., Kerr, J., Lee, S., and Rosenberg, D. E. (2011). Neighborhood environment and physical activity among youth: A review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 41(4), 442–455.

Dobbins, M., Husson, H., DeCorby, K., and LaRocca, R. L. (2013). School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database System Review, 2, CD007651.

Dovidio, J. F., and Fiske, S. T. (2012). Under the radar: How unexamined biases in decision-making processes in clinical interactions can contribute to health care Disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 945–952.

Duncan, G. J., and Murnane, R. J. (2011). Introduction. In G. J. Duncan and R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances (pp. 3–23). New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Duncan, G. J., Katz, L. F., Kessler, R. C., Kling, J. R., Lindau, S. T., Whitaker, R. C., and McDade, T. W. (2011). Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes—a randomized social experiment. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(16), 1509–1519.

Ehrenhalt, A. (2012). The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Entwisle, D. R., Alexander, K. L., and Olson, L. S. (2001). Keep the faucet flowing: Summer learning and home environment. American Educator, 25(3), 10–15.

Evans-Campbell, T. (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(3), 316–338.

Family Voices. (2019). Summer Time Recreation for Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs/Disabilities. Memo submitted to the Committee on Summertime Experiences and Child and Adolescent Education, Health, and Safety.

Farley, T. A., Meriwether, R. A., Baker, E. T., Watkins, L. T., Johnson, C. C., and Webber, L. S. (2006). Safe play spaces to promote physical activity in inner-city children: Results from a pilot study of an environmental intervention. American Journal of Public Health, 97(9), 1625–1631.

Farrigan, T. (2018). Child poverty heavily concentrated in rural Mississippi, even more so than before the Great Recession. Amber Waves, July 2018. Available: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2018/july/child-poverty-heavily-concentrated-in-rural-mississippi-even-more-so-than-before-the-great-recession/.

Farver, J. A. M., Ghosh, C., and Garcia, C. (2000). Children’s perceptions of their neighborhoods. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21, 139–163. doi:10.1016/S0193-3973(99)00032-5.

Food Research & Action Center. (2018). FACTS: The Summer Food Service Program. Available: http://frac.org/programs/summer-nutrition-programs.

Garst, B., Gagnon, R., and Bennett, T. (2016). Parent anxiety causes and consequences: Perspectives from camp program providers. LARNet: The Cyber Journal of Applied Leisure and Recreation Research, 18(1), 21–39.

Geller, A. (2018). Policing America’s Children: Police Contact among Teens in Fragile Families. Working Paper no. WP18-02-FF. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing. Available: https://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/sites/fragilefamilies/files/wp18-02-ff.pdf.

Gershenson, S. (2013). Do summer time-use gaps vary by socioeconomic status? American Educational Research Journal, 50(6), 1219–1248.

Gilliam, W. S., Maupin, A. N., Reyes, C. R., Accavitti, M. and Shic, F., 2016. Do early educators’ implicit biases regarding sex and race relate to behavior expectations and recommendations of preschool expulsions and suspensions. Research Study Brief. Yale University, Yale Child Study Center, New Haven, CT.

Gordon-Larsen, P., Nelson, M. C., Page, P., and Popkin, B. M. (2006). Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics, 117(2), 417–424.

Goshin, L. S. (2015). Ethnographic assessment of an alternative to incarceration for women with minor children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(5), 469–482.

Greenberg, M., and Weissberg, R. (2018). Social and Emotional Development Matters: Taking Action Now for Future Generations. Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center, Pennsylvania State University.

Hales, C. M., Carroll, M. D., Fryar, C. D., and Ogden, C. L. (2017). Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief (288). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics.

Halle, T., Forry, N., Hair, E., Perper, K., Wandner, L., Wessel, J., and Vick, J. (2009). Disparities in Early Learning and Development: Lessons from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Birth Cohort (ECLS-B). Washington, DC: Child Trends.

Hansen, A., and Hartely, D. (2015). Promoting Active Living in Rural Communities. Active Living Research, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Available: https://www.activelivingresearch.org/promoting-active-living-rural-communities.

Hansen, A. Y., Umstattd Meyer, M. R., Lenardson, J. D., and Hartley, D. (2015). Built environments and active living in rural and remote areas: A review of the literature. Current Obesity Reports 4(4), 484–493.

Hardin, J. A. (2004). Juveniles’ Attitudes toward the Police as Affected by Prior Victimization. Master’s thesis, East Tennessee State University. Quoted in Interactions between Youth and Law Enforcement: Literature Review, Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2018.

Himmelstein, K. E. W., and Brückner, H. (2011). Criminal justice and school sanctions against nonheterosexual youth: A national longitudinal study. Pediatrics, 127 (1), 49–57.

Ho, M., Garnett, S. P., Baur, L., Burrows, T., Stewart, L., Neve, M., and Collins, C. (2012). Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in child obesity: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 130(6), e1647–1671.

Hofferth, S. L., and Sandberg, J. F. (2001). How American children spend their time. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 295–308.

Huggins, G. (2012). Untapped strategy for ed reform: Summer learning. The Washington Post, June 18. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/post/untapped-strategy-for-ed-reform-summer-learning/2012/06/18/gJQA3L9amV_blog.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.24d7146309e1.

Hunt, J., and Moodie-Mills, A. (2012). The unfair criminalization of gay and transgender youth: An overview of the experiences of LGBT youth in the juvenile justice system. Center for American Progress, 29, 1–12.

Institute of Medicine. 2003. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., and Borowski, T. (2018). Equity & Social and Emotional Learning: A Cultural Analysis. CASEL Assessment Work Group Brief series.

Johnson, J. A. III, and Johnson, A. M. (2015). Urban-rural differences in childhood and adolescent obesity in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Obesity 11(3), 233–241.

Jones, N. (2018). Commissioned paper prepared for the Committee on Summertime Experiences and Child and Adolescent Education, Health, and Safety.

Khan, L. K., Sobush, K., Keener, D., Goodman, K., Lowry, A., Kakietek, J. and Zaro, S. (2009). Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Recommendations and Reports: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 58(RR-7), 1–26.

Kids Count Data Center. (2017a). A Decade of Data: Kids in High-Poverty Communities. Available: https://datacenter.kidscount.org/updates/show/151-a-decade-of-data.

_____. (2017b). Children in Single-Parent Families by Race in the United States. Available: https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/107-children-in-single-parent-families-by-race#-detailed/1/any/false/871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133,38,35/10,11,9,12,1,13/432,431.

_____. (2019). Children Living in Areas of Concentrated Poverty by Race and Ethnicity in the United States. Available: https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/bar/7753-children-living-in-areas-of-concentrated-poverty-by-race-and-ethnicity?loc=1&loct=1#1/any/false/1691/10,11,9,12,1,185,13/14942.

Kneeshaw-Price, S. H., Saelens, B. E., Sallis, J. F., Frank, L. D., Grembowski, D. E., Hannon, P. A., Smith, N. L. and Chan, K. G. (2015). Neighborhood crime-related safety and its relation to children’s physical activity. Journal of Urban Health, 92(3), 472–489.

Ko, L. K., Enzler, C., Perry, C. K., Rodriguez, E., Mariscal, N., Linde, S., and Duggan, C. (2018). Food availability and food access in rural agricultural communities: Use of mixed methods. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 634.

Lareau, A., Weininger, E. B. (2008). Class and the transition to adulthood. In A. Lareau and D. Conley (Eds.), Social Class: How Does It Work? (pp. 118–151). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lichter, D. T., and Brown, D. L. (2011). Rural America in an urban society: Changing spatial and social boundaries. Annual Review of Sociology 37, 565–592.

Lopez, R. (2011). The Potential of Safe, Secure and Accessible Playgrounds to Increase Children’s Physical Activity. Available: https://activelivingresearch.org/sites/activelivingresearch.org/files/ALR_Brief_SafePlaygrounds_0.pdf.

Mahoney, J. L., Larson, R. W., Eccles, J. S., and Lord, H. (2005). Organized activities as developmental contexts for children and adolescents. In J. L. Mahoney, R. W. Larson, and J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Organized Activities as Contexts of Development: Extracurricular Activities, After-School and Community Programs (pp. 3–22). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Majd, K., Marksamer, J., and Reyes, C. (2009). Hidden Injustice: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth in Juvenile Courts. Legal Services for Children, National Juvenile Defender Center, and National Center for Lesbian Rights.

Mallory, C., Hasenbush, A., and Sears, B. (2015). Discrimination and Harassment by Law Enforcement Officers in the LGBT Community. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute. Available: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Discrimination-and-Harassment-in-Law-Enforcement-March-2015.pdf.

McCombs, J. S., Augustine, C. H., and Schwartz, H. L. (2011). Making Summer Count: How Summer Programs Can Boost Children’s Learning. Washington, DC: RAND Corporation.

McCombs, J., Whitaker, A., and Yoo, P. (2017). The Value of Out-of-School Time Programs. Washington, DC: RAND Corporation. Available: https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/The-Value-of-Out-of-School-Time-Programs.pdf.

McLanahan, S., and Jacobsen, W. (2015). Diverging destinies revisited. In P. R. Amato, S. L. McHale, A. Booth, and J. Hook (Eds.), Diverging Destinies: Families in an Era of Increasing Inequality. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3- 319-08308-7_1.

McPherson, M., Arango, P., Fox, H., Lauver, C., McManus, M., Newacheck, P. W., Perrin, J. M., Shonkoff, J. P. and Strickland, B. (1998). A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics, 102(1), 137–139.

Meade, E. E. (2014). Overview of Community Characteristics in Areas with Concentrated Poverty. ASPE Research Brief. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/40651/rb_concentratedpoverty.pdf.

Mowen, A. J., Graefe, A. R., Barrett, A. G., and Godbey, G. C. (2016). Americans’ Use and Perceptions of Local Recreation and Park Services: A Nationwide Reassessment. Prepared for the National Recreation and Park Association. Available: https://www.nrpa.org/uploadedFiles/nrpa.org/Publications_and_Research/Research/Park-Perception-Study-NRPA-Full-Report.pdf.

Musumeci, M. (2018). Medicaid’s role for children with special health care needs. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 46(4), 897–905.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Advancing Health Equity for Native American Youth: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/21766.

_____. (2019a). A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

_____. (2019b). The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

National Center for Children in Poverty. (2018). United States Demographics of Low-Income Children. November 19. Available: http://www.nccp.org/profiles/US_profile_6.html.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Back to School Statistics. Available: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372.

National Indian Child Welfare Association. (2017). Report on Disproportionality of Placements of Indian Children. Available: https://www.nicwa.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/09/Disproportionality.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Available: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/9824/from-neurons-to-neighborhoods-the-science-of-early-childhood-development.

_____. (2001) Juvenile Crime, Juvenile Justice. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

_____. (2002). Community Programs to Promote Youth Development. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/10022.

Novoa, C. (June 11, 2018). Families Can Expect to Pay 20 Percent of Income on Summer Child Care. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. Available: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/news/2018/06/11/451700/families-can-expect-pay-20-percent-income-summer-child-care.

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Fakhouri, T. H., Hales, C. M., Fryar, C. D., Li, X., and Freedman, D. S. (2018). Prevalence of obesity among youths by household income and education level of head of household—United States 2011–2014. MMWR/Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 186–189. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6706a3.

Okonofua, J. A., and Eberhardt, J. L. (2015). Two strikes: Race and the disciplining of young students. Psychological science, 26(5), 617–624.

Pereira, R. F., Sidebottom, A. C., Boucher, J. L., Lindberg, R., and Werner, R. (2014). Assessing the food environment of a rural community: Baseline findings from the heart of New Ulm project, Minnesota, 2010-2011. Preventing Chronic Disease, 11, E36.

Perry, C. K., Garside, H., Morones, S., and Hayman, L. L. (2012). Physical activity interventions for adolescents: An ecological perspective. Journal of Primary Prevention, 33(2–3), 111–135.

Pew Research Center. (2015). Parenting in America, The American Family Today. Available: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/12/17/1-the-american-family-today/#fn-21212-4.

_____. (2018a). What Unites and Divides Urban, Suburban and Rural Communities. Available: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2018/05/Pew-Research-Center-Community-Type-Full-Report-FINAL.pdf.

_____. (2018b). Demographic and Economic Trends in Urban, Suburban and Rural Communities. Available: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/05/22/demographic-and-economic-trends-in-urban-suburban-and-rural-communities.

Piontak, J., and Schulman, M. (2014). Food insecurity in rural America. Contexts, 13(3), 75–77.

Pollack, C. E., Thornton, R. L. J., and DeLuca, S. (2014). Targeting housing mobility vouchers to help families with children. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(8), 695–696.

Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D. P., Garcia-Hermoso, A., Alvarez-Bueno, C., Sanchez-Lopez, M., and Martinez-Vizcaino, V. (2018). Effectiveness of school-based physical activity programmes on cardiorespiratory fitness in children: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(19), 1234–1240.

Puzzanchera, C., Hockenberry, S., Sladky, T. J., and Kang, W. (2018). Juvenile Residential Facility Census Databook. Available: https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/jrfcdb/.

Ream, G. L., and Forge, N. R. (2014). Homeless lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth in New York City: Insights from the field. Child Welfare 93(2), 7–22.

Reardon, S. (May 2013). The widening income achievement gap. Educational Leadership, 70(8), 10–16.

Reardon, S. F., and Portilla, X. A. (2016). Recent trends in income, racial, and ethnic school readiness gaps at kindergarten entry. Aera Open, 2(3), 1–18.

Redford, J., Burns, S., and Hall, L. J. (2018). The summer after kindergarten: Children’s experiences by socioeconomic characteristics. Stats in Brief. NCES 2018-160. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Ribar, D. C. (2015). Why marriage matters for child wellbeing. The Future of Children, 11–27.

Roth, K. (2018). Parks and recreation: Out of school time leaders. Parks & Recreation Magazine, December. Available: https://www.nrpa.org/parks-recreation-magazine/2018/december/parks-and-recreation-out-of-school-time-leaders.

Safe Routes to School National Partnership. (2015). Rural Communities: Best Practices and Promising Approaches for Safe Routes. Available: https://www.saferoutespartnership.org/resources/toolkit/rural-communities-best-practices-srts.

Sanden, M., and Wentz, E. (2017). Kids and cops: Juveniles’ perceptions of the police and police services. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 33(4), 411–430.

Shikany, J. M., Carson, T. L., Hardy, C. M., Li, Y., Sterling, S., Hardy, S., Walker, C. M., and Baskin, M. L. (2018). Assessment of the nutrition environment in rural counties in the Deep South. Journal of Nutrition Science, 7, e27.

Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., and McEwen, B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(21), 2252–2259.

Singh, A. S., Mulder, C., Twisk, J. W., van Mechelen, W., and Chinapaw, M. J. (2008). Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Review, 9(5), 474–488.

Taylor, W., and Lou, D. (2011). Do All Children Have Places to Be Active? Disparities in Access to Physical Activity Environments in Racial and Ethnic Minority and Lower-Income Communities. Available: https://activelivingresearch.org/sites/activelivingresearch.org/files/Synthesis_Taylor-Lou_Disparities_Nov2011_0.pdf.

The Aspen Institute National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development (2019). From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope. Available: http://nationathope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018_aspen_final-report_full_webversion.pdf.

The Sentencing Project. (2017). Black disparities in youth incarceration. Available: https://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Black-Disparities-in-Youth-Incarceration.pdf.

Thornton, R. L., Glover, C. M., Cené, C. W., Glik, D. C., Henderson, J. A., and Williams, D. R. (2016). Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Affairs, 35(8), 1416–1423.

Thurau, L. H. (2009). Rethinking how we police youth: Incorporating knowledge of adolescence into policing teens. Children’s Legal Rights, 29(3), 30.

Thurau, L. H. (2013). If Not Now, When? A Survey of Juvenile Justice Training in America’s Police Academies. Cambridge, MA: Strategies for Youth.

Umstattd, M. M., Perry, C. K., Sumrall, J. C., Patterson, M. S., Walsh, S. M., Clendennen, S. C., Hooker, S. P., Evenson, K. R., Goins, K. V., Heinrich, K.M. and O’Hara, N. T. (2016). Physical activity-related policy and environmental strategies to prevent obesity in rural communities: A systematic review of the literature, 2002–2013. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, E03.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). New Census Data Show Differences Between Urban and Rural Populations. Available: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2016/cb16-210.html.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2017). Children’s Food Security and USDA Child Nutrition Programs. Available: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84003/eib-174.pdf.

U.S. Department of Education. (2018). Credit Recovery. Issue Brief. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development, U.S. Department of Education.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). The AFCARS Report. Washington, DC. Available: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport25.pdf

_____. (2019). Children with Special Health Care Needs. Available: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/maternal-child-health-topics/children-and-youth-special-health-needs.

Van Ryn, M., and Fu, S. S. (2003). Paved with good intentions: Do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? American Journal of Public Health, 93, 248–255.

Van Sluijs, E., Kriemler, S., and McMinn, A. (2011). The effect of community and family interventions on young people’s physical activity levels: A review of reviews and updated systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45, 914–922.

Van Sluijs, E., McMinn, A., and Griffin, S. (2008). Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: Systematic review of controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(8), 653–657.

Villanueva, K., Giles-Corti, B., Bulsara, M., McCormack, G. R., Timperio, A., Middleton, N., Beesley, B., and Trapp, G. (2012). How far do children travel from their homes? Exploring children’s activity spaces in their neighborhood. Health & Place, 18(2), 263–273.

Waters, E., de Silva-Sanigorski, A., Burford, B. J., Brown, T., Campbell, K. J., Gao, Y., Armstrong, R., Prosser, L. and Summerbell, C. D. (2011). Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database System Review, 12, CD001871.

Worobey, J., Lelah, L., and Gaugley, Y. (2013). Environmental barriers to children’s outdoor summer play. Journal of Behavioral Health, 2(4), 362–36.

Young, D. R., Spengler, J. O., Frost, N., Evenson, K. R., Vincent, J. M., and Whitsel, L. (2014). Promoting physical activity through the shared use of school recreational spaces: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. American Journal of Public Health, 104(9), 1583–1588.

Yousefian, A., Ziller, E., Swartz, J., and Hartley D. (2009). Active living for rural youth: Addressing physical inactivity in rural communities. Journal of Public Health Management Practice, 15(3), 223–231.

Zimmerman, F. J., and Anderson, N. W. (2019). Trends in health equity in the United States by race/ethnicity, sex, and income, 1993-2017. JAMA Network Open, 2(6), e196386-e196386.

This page intentionally left blank.