1

Introduction

Adolescence is period of immense growth, learning, exploration, and opportunity during which youth develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills that will help them thrive throughout life. While most youth traverse adolescence without incident, some need additional support to promote their optimal health. Sometimes such support comes in the form of a prevention or intervention program designed to capitalize on the rapid, formative changes that occur during this period so as to encourage healthy behaviors that will follow the adolescent through adulthood. However, no program is one size fits all, and too often these programs target specific risk behaviors instead of aiming to support the whole person. Such programs fail to understand not only the interdependence of health behaviors and outcomes but also the diverse needs and experiences of youth. In the face of the constant technological and cultural changes that define each generation of adolescents, moreover, the design, implementation, and evaluation of adolescent

health programming will need to be more innovative to ensure the equitable achievement of optimal health for all youth.

STUDY OVERVIEW

In this context, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH) in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) requested that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convene an ad hoc committee to review key questions related to the implementation of the Teen Pregnancy Prevention (TPP) program using an optimal health lens. To carry out this review, the National Academies convened the nine-member Committee on Applying Lessons of Optimal Adolescent Health to Improve Behavioral Outcomes for Youth; the committee’s full statement of task is presented in Box 1-1. The committee’s membership, based on the study’s statement of task, included expert scholars and practitioners representing a diverse set of disciplines, including program implementation and evaluation, public health, adolescent health policy and research,

psychology, public policy, teen pregnancy prevention, and health disparities. In this report, the committee uses an optimal health framework to (1) identify core components of risk behavior prevention programs that can be used to improve a variety of adolescent health outcomes, and (2) develop evidence-based recommendations for research and the effective implementation of federal programming initiatives focused on adolescent health.

The committee’s statement of task reflects the sponsor’s mission to integrate the concept of optimal health into its projects and initiatives, particularly those related to sexual and reproductive health (HHS, 2019a). OASH’s “optimal health model,” also referred to as risk avoidance theory (HHS, 2018a), indicates that optimal health is achieved when one is in a state of “no risk” (HHS, 2019a). Citing the public health prevention framework (described in the section on definitions later in this chapter), this model posits that optimal health can be achieved through primary prevention, or risk avoidance, and secondary prevention, or risk reduction, with the goal of always moving toward an area of lower or no risk. As originally applied to sexual behavior, risk avoidance refers to refraining from non-marital sexual activity (HHS, 2017a, 2018a), while risk reduction entails choosing to return to a state of risk avoidance or, if continuing to engage in sexual activity, using protection and family planning methods (HHS, 2019a).

In addition to adopting an optimal health lens for this project, OASH asked the committee to identify what could be learned from other risk behavior programs that could be applied to the initiatives it oversees, including not only the TPP program, but also programs focused on mental and physical health, adolescent development, and reproductive health more broadly. To this end, the committee was charged with using a core components approach, a relatively new program evaluation methodology that is already being used in other federal research and evaluation initiatives (Blase and Fixsen, 2013). Briefly, the purpose of core components research is to identify the “active ingredients” of evidence-based programs (EBPs) or interventions instead of evaluating a program as a whole. Once identified, these effective components can be used to implement programs more flexible than the original EBPs, which are often difficult to replicate with fidelity and inflexible to diverse community needs (Blase and Fixsen, 2013). With regards to the present study, the identification of core components that are effective across health behaviors and programs may also help in coordinating programming efforts in areas in which funding has historically been fragmented (e.g., teen pregnancy, substance use) (HHS, 2018b).

BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE TEEN PREGNANCY PREVENTION PROGRAM

The TPP program is a national grant program established by congressional mandate in 2010 under the direction of OASH’s Office of Adolescent Health (now Office of Population Affairs). The purpose of this program is to fund organizations to develop and implement medically accurate and age-appropriate EBPs focused on preventing teen pregnancy among 10- to 19-year-old adolescents. Grantees are given 5 years of funding, and grantmaking is directed toward populations that experience the greatest disparities in teen pregnancy and birth rates.

The first cohort (fiscal 2010 to 2014) included 102 grantees, which collectively worked with approximately 500,000 youth across the United States. The second cohort (fiscal 2015 to 2019) included 84 grantees. Each grant fell under one of four categories focused on preventing teen pregnancy, the majority of which focused on replicating the effects of EBPs that were included in the TPP registry of effective programs. The four categories were (1) capacity building for EBPs (Tier 1A), (2) implementing EBPs to scale (Tier 1B), (3) early innovation (Tier 2A), and (4) rigorous evaluation of new approaches (Tier 2B) (HHS, 2017b).

STUDY APPROACH

An important part of the committee’s charge was to explore the scientific literature on adolescent health behavior programs through an optimal health lens. Thus, the committee first needed to apply the definition of optimal health to the adolescent population and explain adolescent development through this lens. To this end, the committee drew on the National Academies report titled The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2019a), as well as other evidence from established theories of adolescent health and development in the scientific literature (Chapter 2).

This study’s statement of task also directed the committee to select the programs and outcomes to examine for inclusion in this report. Given the broad scope of outcomes that could be considered, the focus on risk behavior in the statement of task, and the limited time period for the preparation of this report, we chose to focus on three specific risk behaviors and their related health outcomes: ultimately, we selected alcohol use, tobacco use, and sexual behavior.

In general, these selections were based on (1) the prevalence of these behaviors among today’s adolescents, (2) the significant amount of data describing demographic trends in these behaviors, and (3) the large number of peer-reviewed studies of EBPs that have targeted these behaviors and

related outcomes. These three areas are not meant to provide exhaustive coverage of all the behaviors and health outcomes that are critical to optimal adolescent health. Rather, they are representative of the challenges that adolescents face and are well suited to review in a consensus study review because of their extensive coverage in the literature. More specifically, we chose sexual behavior given the focus in the statement of task on the TPP program. We selected alcohol use because, like sexual behavior, it is a risk behavior that is age graded; that is, it is generally considered to be socially acceptable once a person reaches a particular age or developmental milestone, rather than consistently considered to be a dangerous or unhealthy behavior across the lifespan. Finally, we chose tobacco use based on the decades of research on primary and secondary prevention programs for nicotine addiction and tobacco-related diseases, which we judged to be potentially informative to our task.

This approach is not without limitations. For example, we did not include a specific focus on obesity prevention programs relevant to healthy diet and physical activity, as the focus of our task was explicitly on risk behaviors. In addition, we did not include a focused review of programs to prevent violence. We made this decision in recognition of the wide breadth of topics that fall under the umbrella of violence, so that we were concerned that the scope of this literature would make it difficult to review and incorporate concisely in this report.1 However, it is important to note that violence often co-occurs with our three selected risk behaviors. For example, violence in the form of bullying can lead to increased substance use behaviors, and sexual behavior under the influence of alcohol can lead to violence in the form of sexual assault. Thus where relevant, we draw connections to violence in our discussion of alcohol use, tobacco use, and sexual behavior.

Importantly, although many comparisons can be drawn among prevention and intervention programs for sexual behavior, alcohol use, and tobacco use, there are also significant differences that need to be addressed. For example, while we chose to focus on alcohol use because it becomes socially sanctioned with maturity, this does not mean that alcohol use and sexual behavior should be interpreted as analogous. Alcohol misuse represents a significant public health problem in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019a), and like tobacco, alcohol is neurotoxic to the developing adolescent brain (Institute of Medicine, 2015; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2004). In contrast, sexual development represents a critical developmental task of adolescence, whereby the necessary building blocks for adult relationships are estab-

___________________

1 See Box 3-1 in Chapter 3 for a list of recent National Academies reports dedicated to violence-related topics.

lished (NASEM, 2019a). It is therefore as important to support healthy sexual development as to prevent the negative health outcomes associated with sexual behavior (e.g., unintended pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections) during the adolescent period.

Chapters 2 and 3 of the report provide the groundwork for the committee’s response to its central charge: to use evidence from a variety of youth-serving programs to identify key program factors that can promote optimal adolescent health. These chapters are based on the committee’s examination of the scientific literature on adolescent development and risk-taking behaviors. To the extent possible, we cite recent reviews of the scientific literature rather than individual studies in these chapters in an effort to present information that is supported by evidence from multiple rigorous scientific studies and across contexts.

In developing Chapter 4, the committee used a systematic review methodology and expert review of contemporary papers on core program components to analyze the available research on adolescent health behavior programs using an optimal health lens. This review was intended to identify the core components of programs with evidence of effectiveness, with consideration of methodological issues. We also considered other methods for our review of effective program components, including a meta-analysis of primary studies, but eventually selected our systematic review approach as a way of examining a larger body of literature within the constraints of the study period.

Broadly, programs were included in our systematic review if they targeted outcomes in one or more of the five optimal health domains (physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and intellectual), with a particular emphasis on programs focused on alcohol use, tobacco use, and sexual behavior in the physical health domain. In addition to this systematic review, we reviewed contemporary papers that are clearly focused on core components of effective programs to ensure that we would examine the most current research on core components of adolescent health behavior programs.

Finally, the committee was asked to develop evidence-based recommendations for (1) adolescent health research and (2) the effective implementation of federal programming initiatives. Our resulting three recommendations and two promising approaches (Chapter 5) are based on the findings and conclusions presented in Chapters 2–4. While these recommendations and approaches are directed largely to federal, state, and local governments, and specifically to OASH offices and program grantees, other audiences of interest include professional associations for adolescent care, program providers, researchers, and community-based stakeholders.

To supplement our members’ own expertise, we commissioned several papers; held a public information-gathering session; and requested information from current TPP Tier 1B grantees in order to hear from researchers,

practitioners, educators, and youth on key topics related to our charge. We also commissioned a text message poll administered to a national sample of adolescents through the University of Michigan’s MyVoice study. Major themes and selected quotes from this poll appear throughout this report to provide a youth perspective on what it means to thrive today. The full MyVoice report can be found in our online resources;2 the MyVoice methodology is described in Appendix B.

DATA SOURCES

This section briefly describes the sources of data used by the committee and the rationale for their selection for use in this report.

The health outcome data derive from a variety of federal sources, including the CDC’s surveillance systems, the U.S. Department of Transportation, and the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). To evaluate risk behavior trends, the committee deliberated over a number of nationally representative datasets—Monitoring the Future (MTF), the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), the NSFG, and the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS)—that could provide information about adolescent alcohol use, tobacco use, and sexual behavior.

The MTF, NYTS, and NSDUH surveys all focus on substance use behaviors. More specifically, the MTF is a school-based survey funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse that has collected data on adolescent drug use and related behaviors in every year since 1991 (Institute for Social Research, 2019). Similarly, the NYTS is a school-based survey that has been administered by the CDC every 1–3 years since 1999 to examine youth tobacco use and associated predictors and attitudes (CDC, 2019b; HHS, 2019b). Finally, the NSDUH is an annual household survey that has been administered by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration since 1971, in which all household members ages 12 and older provide information about their alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use (HHS, 2019c).

In contrast, the CDC’s NSFG is a continuous, household-based survey that has collected detailed data on family life, marriage and divorce, pregnancy, infertility, use of contraception, and general and reproductive health among those ages 15–49 since 1973 (CDC, 2019c). From 1973 to 2002,

___________________

2 See MyVoice (2019). Youth perspectives on being healthy and thriving. Report Commissioned by the Committee on Applying Lessons of Optimal Adolescent Health to Improve Behavioral Outcomes for Youth. Available: https://www.nap.edu/resource/25552/Youth%20Perspectives%20on%20Being%20Healthy%20and%20Thriving.pdf.

the NSFG included only women ages 15–44, but it has since expanded to include men (in 2002) and those ages 45–49 (in 2015).

The purpose of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) is to monitor the prevalence of a variety of health behaviors among U.S. adolescents that are associated with later morbidity and mortality outcomes, including behaviors that contribute to unintentional injuries and violence; sexual behaviors related to unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases; alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use; unhealthy dietary behaviors; and inadequate physical activity (CDC, 2018). Every 2 years since 1991, it has collected data from a nationally representative, cross-sectional sample of in-school adolescents who were in grades 9–12 during the study year using the national YRBS. More than 4.4 million adolescents have participated in the YRBS since 1991, with the most recent survey being conducted in 2017.

In reality, none of the currently available national datasets provide a fully comprehensive picture of youth risk behaviors, as all but the NSDUH and NSFG are school-based surveys. Thus they fail to include adolescents who are incarcerated; homeless; home-schooled; or in private alternative, special education, or vocational schools. This is a critical limitation, since out-of-school adolescents, particularly incarcerated and homeless youth, are at the greatest risk for engaging in unhealthy risk behaviors and are more likely to experience the related adverse health outcomes (Edidin et al., 2012; Odgers, Robins, and Russell, 2010; Tolou-Shams et al., 2019).

Among the above datasets, the YRBS is the only one that provides information on all three of the focal behaviors in this study (alcohol use, tobacco use, and sexual behavior) within the same group of adolescents. It is also the dataset that the sponsor identified as its main source of information about trends in adolescent risk behaviors. We therefore chose to use the YRBS to the extent possible to describe those trends for this report,3 while also noting this dataset’s strengths and weaknesses (see Chapter 3).

DEFINITIONS

The key terms used in this report are defined below.

Adolescence

Although the hallmark developmental changes of adolescence can begin before age 10 and persist after age 19, adolescent is defined in this report as

___________________

3 E-cigarette data are from the NYTS because this survey provides the most up-to-date information on this rapidly growing epidemic.

a young person ages 10–19. This age range was provided to the committee by the sponsor and represents the target age range for the TPP program.

Optimal Health

The statement of task asked the committee to use an optimal health lens. After searching the current peer-reviewed literature for “optimal health” to provide this context, we found only reference to a definition by O’Donnell (1986). This definition was updated in 2009 as part of O’Donnell’s broader model of health promotion, which he shared in an editorial statement for the American Journal of Health Promotion (2009) (see Box 1-2). This is also the definition that OASH has used for its optimal health model (HHS, 2018a, 2019a).

Since introducing the term in 1986, O’Donnell has written extensively about optimal health, providing detailed descriptions of each of its five dimensions (Box 1-2), as well as further interpretation of his original definition (2017). See Chapter 2 for further discussion of O’Donnell’s optimal health definition.

Adolescent Risk Taking and Experimentation

Neurobiological changes that occur during the course of adolescence influence adolescents to seek novel experiences and make sense of their environments through risk taking and experimentation. Although certain risk behaviors can have real and destructive impacts, adolescence is often wrongly viewed as being synonymous with a period of “storm and stress” (Arnett, 1999). Public perception of adolescent risk taking often entails negative connotations, such as the deep-rooted societal view that it is destructive. Instead, it serves as a precursor to the assumption of adult roles (Romer, Reyna, and Satterthwaite, 2017; Wahlstrom et al., 2010), helping adolescents become autonomous, explore their identity, and forge social ties (Maggs, Almeida, and Galambos, 1995). Risk taking therefore is a normal part of the transition away from a childhood state of parental or caregiver dependence to exploring and acquiring independence and self-identity (NASEM, 2019a).

At the same time, although risk-taking behaviors are a normative and adaptive part of adolescence, adolescents are more prone than those in other age groups to participate in unhealthy risk behaviors, such as tobacco use and binge drinking (Duell and Steinberg, 2019). Engaging in unhealthy risk behaviors can lead to adverse outcomes that not only threaten health, but also can endanger others, as in the case of reckless driving or violent aggression (World Health Organization, 2006). Accordingly, the impact of these unsafe behaviors on adolescent health outcomes has been recognized as an important public health issue (DiClemente, Hansen, and Ponton, 2013). Bearing the cost of these behaviors, society shares in the responsibility for helping to set adolescents on a path toward fully realizing their potential by promoting and improving their multidimensional health and by reducing the negative consequences associated with unhealthy risk behaviors through health promotion and prevention efforts.

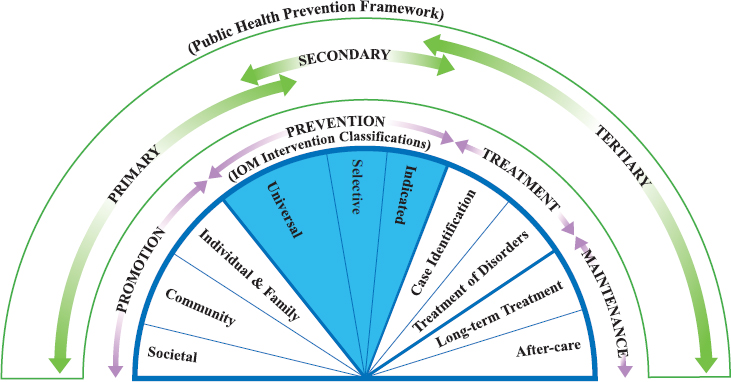

Public Health Prevention Framework

The three-level public health prevention framework (Katz and Ali, 2009) was chosen as the initial model of prevention for this report based on discussion with the sponsor at the committee’s first meeting. In this framework, primary prevention is focused on the risk factors for a disease or condition, with the intent of intervening before it occurs. Included in primary prevention are such interventions as vaccination and behavior change programs, both of which can prevent the onset or reduce the impact of a disease or condition (CDC, 2017; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2018). Secondary prevention focuses on early identification of high-risk populations, which can aid in slowing or stopping the progression of a

disease or condition (CDC, 2017; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2018). It includes such strategies as early testing and monitoring for signs or symptoms of a disease or condition. Finally, tertiary prevention refers to treatment and rehabilitation after the onset or diagnosis of a disease or condition, which can prevent its future incidence (CDC, 2017; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2018).

Importantly, this public health prevention framework is designed with health outcomes as the key target. Although a health behavior is an important predictor of a health outcome, behaviors are considered to be modifiable risk factors that are a focus in primary prevention activities and are distinguished from the health outcome itself.

This separation of health behaviors and outcomes is a subtle yet important part of this framework. Behaviors can be difficult to prevent, and societal attitudes and beliefs about the acceptability of such behaviors as alcohol use and sexual behavior often change with age. Thus, focusing only on avoiding or discontinuing these behaviors does not prepare a person to prevent adverse health outcomes once the behaviors are socially acceptable or age-appropriate.

For example, alcohol use during adolescence can have harmful effects on brain development, which has contributed to the adoption of laws regarding minimum legal drinking ages (HHS, 2017c). However, simply telling youth not to drink alcohol (health behavior) will not prepare them to avoid impairment and injury (health outcome) once this behavior is socially sanctioned. Instead, youth need to learn about the social norms related to drinking and how to make decisions about alcohol that can help prevent impairment or injury once their drinking behaviors are legal.

As another example, preventing an unintended pregnancy (health outcome) is an issue not unique to teens or unmarried people, as many people want or need to control their fertility after marriage. Therefore, an exclusive focus on teaching abstinence from sexual activity (health behavior) does not provide people with the necessary knowledge and skills to prevent an unintended pregnancy once they do have vaginal sex. Rather, targeting communication, decision-making skills, and family planning behaviors is more likely to be successful in preventing unintended pregnancy, not only during adolescence, but also across the life course.

Institute of Medicine (IOM) Intervention Classifications

As the committee began its review of programs and interventions (Chapter 4), we found that the IOM intervention classifications were another helpful way to conceptualize prevention for the purposes of our task. These classifications, based on the prevention model proposed by Gordon (1983), encompass universal, selective, and indicated programs and interventions.

Universal prevention programs and interventions target an entire population, regardless of its members’ levels of risk. Selective programs and interventions target a subset of the population that may be considered at risk. Finally, indicated programs and interventions target those who are already beginning to experience the effects of a specific health outcome (IOM, 1994).

The public health prevention framework described above and the IOM intervention classifications are not mutually exclusive, but rather provide two different ways of describing prevention activities. Figure 1-1 illustrates how these two prevention models overlap. The half-moon in the center of the figure represents a health promotion model that was published in the most recent update (NASEM, 2019b) to the original IOM (1994) report. In this model, prevention is distinct from promotion, treatment, and maintenance. In contrast, the public health prevention framework, shown on the outer ring, takes a broader approach whereby promotion, treatment, and maintenance are included among prevention activities. The overlapping arrows in the public health prevention framework represent how program recipients may be at different levels of risk for the targeted health outcome when they receive intervention services.

Protective and Risk Factors

Programs and interventions that use these prevention models to decrease or eliminate negative health outcomes associated with unhealthy adolescent risk-taking behaviors often aim to capitalize on protective factors and mitigate risk factors (CDC, 2019d). Protective factors are characteristics of the adolescent or his or her environments (e.g., family, school, community) that help build resilience in the face of challenges. Research shows that adolescents who possess these protective factors are less likely than others to put themselves at risk for negative health outcomes by engaging in unhealthy risk behaviors (IOM, 2011). Risk factors, conversely, are characteristics of the adolescent and his or her environments that are associated with greater adversity and have been shown in research to be associated with more unhealthy risk behaviors.

Health Inequities, Structural Inequities, and the Social Determinants of Health

As described in a recent National Academies report (NASEM, 2017), health inequities are systematic differences in opportunities that lead to unfair and avoidable differences in health outcomes. There are two root causes of these inequities. First are structural inequities that result in an unequal distribution of power and resources based on race, gender, class, sexual orientation, gender expression, and/or other identities. These struc-

SOURCES: Institute of Medicine, 1994 (IOM Intervention Classifications); Katz and Ali, 2009 (Public Health Prevention Framework); adapted from NASEM (2019b).

tural inequities include, for example, such issues as racism, sexism, classism, ableism, xenophobia, and homophobia. The second root cause is unequal allocation of power and resources that results in unequal social, economic, and environmental conditions, which are also referred to as the social determinants of health (NASEM, 2017). The social determinants of health are defined as the environments and conditions in which a person lives, learns, works, plays, worships, and grows, all of which are influenced by historical and contemporary policies, laws and governments, investments, cultures, and norms (NASEM, 2017). While developmental changes help explain adolescent risk-taking behaviors, it is important to highlight the impact of these social determinants, as biological, behavioral, and social factors all play an important role in shaping adolescents’ well-being, health outcomes, and exposure to risks (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2014; NASEM, 2017).

To design and implement effective and sustainable interventions that reduce disparities and promote health equity, it is necessary first to understand how these social determinants affect adolescents—especially those who are disadvantaged and/or marginalized—and impede their health (NASEM, 2017). The effects of the social determinants of health are felt from the individual level (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and skills) to the systems level (e.g., policies, laws, and regulations) throughout the life course. These levels function both independently and concurrently, creating a complex social environment in which adolescents live and grow.

Studies have demonstrated the long-term protective effects of community socialization against such negative outcomes as deviant peer affiliation, conduct disorder, and unhealthy sexual risk behaviors (Browning et al., 2008; Nasim et al., 2011). Conversely, negative contexts can have deleterious effects on adolescents’ well-being. For example, results from a meta-analysis of 214 studies on racial/ethnic discrimination and adolescent well-being revealed that elevated exposure to discrimination is associated with increased depression and other internalizing problems; greater psychological distress; poorer self-esteem; lower academic achievement and academic motivation; and greater engagement in externalizing behaviors, including substance use and unhealthy sexual risk behaviors (Benner et al., 2018).

Marginalization status is also an important consideration. For adolescents who are marginalized (e.g., those who are homeless, are justice involved, are estranged from their family, identify as LGBTQ, or have a disability), social, family, and individual exclusion can lead to health inequities. While marginalized groups are diverse, they share the likelihood of being people of color and lower-income, compounding the effects of structural inequities and negative social determinants of health that undermine their prospects for future well-being (NASEM, 2017). Marginalized adolescents have the capacity for resilience, but pathways for achieving health and well-being that target their needs must be available to them (Auerswald, Piatt, and Mirzazadeh, 2017; Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015).

However, identifying these needs can be challenging. There is a major gap in the literature with respect to connecting behaviors that often lead to marginalization, such as juvenile justice involvement, compromised mental health, low school engagement, illicit drug use, early teen pregnancy, and sexually transmitted infections, to stressful conditions occurring in families. In addition, reaching and delivering services to many marginalized adolescents poses inherent challenges. Thus, those who are most in need of and might benefit most from interventions to reduce health inequities are often the least likely to receive them (Auerswald, Piatt, and Mirzazadeh, 2017).

Core Components Framework

Past federal programming has often required grantees to develop or use EBPs, programs that have demonstrated high levels of effectiveness based on (1) rigorous scientific evaluation, (2) large studies with diverse populations or multiple replications, and (3) significant and sustained effects (Flay et al., 2005). However, research indicates that EBPs are often difficult to implement with fidelity, which casts doubt on their effectiveness in diverse settings and populations (Barth and Liggett-Creel, 2014). As a result, more

recent attention has been placed on the common, core components across a variety of EBPs, which may be more effective in improving targeted program outcomes compared with the program as a whole (Barth and Liggett-Creel, 2014; Chorpita, Delaiden, and Weisz, 2005; Embry and Biglan, 2008; Hogue et al., 2017). For this report, core components of programs and interventions are defined as “discrete, reliably identifiable techniques, strategies, or practices that are intended to influence the behavior or well-being of a service recipient” (Chapter 4).

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized into five chapters. Following this introduction, Chapter 2 focuses on normative adolescent development through an optimal health lens. Chapter 3 begins with a discussion of normative risk-taking behavior, then highlights demographic trends in alcohol use, tobacco use, and sexual behavior and their related health outcomes among adolescents. Chapter 4 presents the committee’s review of the core components of adolescent health behavior programs and interventions, with a particular focus on the behaviors identified in Chapter 3. All of the above chapters end with a summary of the committee’s chapter-specific conclusions. Finally, Chapter 5 presents the committee’s three recommendations for research and programs/interventions, as well as two promising approaches for program and intervention improvement.

REFERENCES

Acevedo-Garcia, D., McArdle, N., Hardy, E.F., Crisan, U.I., Romano, B., Norris, D., Baek, M., and Reece, J. (2014). The child opportunity index: Improving collaboration between community development and public health. Health Affairs, 33(11), 1948–1957.

Arnett, J.J. (1999). Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. American Psychologist, 54(5), 317.

Auerswald, C.L., Piatt, A.A., and Mirzazadeh, A. (2017). Research with Disadvantaged, Vulnerable and/or Marginalized Adolescents. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Office of Research.

Barth, R.P. and Liggett-Creel, K. (2014). Common components of parenting programs for children birth to eight years of age involved with child welfare services. Children and Youth Services Review, 40, 6–12.

Benner, A.D., Wang, Y., Shen, Y., Boyle, A.E., Polk, R., and Cheng, Y-P. (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. American Psychologist, 73(7), 855.

Blase, K., and Fixsen, D. (2013). Core Intervention Components: Identifying and Operationalizing What Makes Programs Work. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Human Services Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Browning, C.R., Burrington, L.A., Leventhal, T., and Brooks-Gunn, J. (2008). Neighborhood structural inequality, collective efficacy, and sexual risk behavior among urban youth. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49(3), 269–285.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017). Picture of America: Prevention. Atlanta, GA: Author.

———. (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) Overview. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/overview.htm.

———. (2019a). Alcohol and Public Health. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/index.htm.

———. (2019b). National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS). Smoking & Tobacco Use. Atlanta, GA: Author.

———. (2019c). About the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/about_nsfg.htm.

———. (2019d). Protective Factors. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/protective/index.htm.

Chorpita, B.F., Delaiden, E.L., and Weisz, J.R. (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence-based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7, 5–20.

DiClemente, R.J., Hansen, W.B., and Ponton, L.E. (2013). Handbook of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science+Business Media.

Duell, N., and Steinberg, L. (2019). Positive risk taking in adolescence. Child Development Perspectives, 13(1), 48–52.

Edidin, J.P., Ganim, Z., Hunter, S.J., and Karnik, N.S. (2012). The mental and physical health of homeless youth: A literature review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 43(3), 354–375.

Embry, D.D. and Biglan, A. (2008). Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11(3), 75–113.

Flay, B.R., Biglan, A., Boruch, R.F., Castro, F.G., Gottfredson, D., Kellam, S., Mościcki, E.K., Schinke, S., Valentine, J.C., and Ji, P. (2005). Standards of evidence: Criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prevention Science, 6(3), 151–175.

Gordon, R.S. (1983). An operational classification of disease prevention. Public Health Reports, 98(2), 107.

Hogue, A., Bobek, M., Dauber, S., Henderson, C.E., McLeod, B.D., and Southam-Gerow, M.A. (2017). Distilling the core elements of family therapy for adolescent substance use: Conceptual and empirical solutions. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 26(6), 437–453.

Institute for Social Research. (2019). Monitoring the Future: Drug Use and Lifestyles of American Youth (MTF). Available: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (1994). Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. (2011). The Science of Adolescent Risk-Taking: Workshop Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. (2015). Public Health Implications of Raising the Minimum Age of Legal Access to Tobacco Products. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2015). Investing in the Health and Well-being of Young Adults. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Katz, D.L., and Ali, A. (2009). Preventive Medicine, Integrative Medicine, and the Health of the Public. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine.

Maggs, J.L., Almeida, D.M., and Galambos, N.L. (1995). Risky business: The paradoxical meaning of problem behavior for young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 15(3), 344–362.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2017). Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. (2019a). The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. (2019b). Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth: A National Agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nasim, A., Fernander, A., Townsend, T.G., Corona, R., and Belgrave, F.Z. (2011). Cultural protective factors for community risks and substance use among rural African American adolescents. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 10(4), 316–336.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2004). Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Odgers, C.L., Robins, S.J., and Russell, M.A. (2010). Morbidity and mortality risk among the “forgotten few”: Why are girls in the justice system in such poor health? Law and Human Behavior, 34(6), 429–444.

O’Donnell, M.P. (1986). Definition of health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 1(1), 4–5.

O’Donnell, M.P. (2009). Definition of health promotion 2.0: Embracing passion, enhancing motivation, recognizing dynamic balance, and creating opportunities. American Journal of Health Promotion, 24(1), iv.

O’Donnell, M.P. (2017). Health Promotion in the Workplace (5th ed.). Troy, MI: Art & Science of Health Promotion Institute.

Romer, D., Reyna, V.F., and Satterthwaite, T.D. (2017). Beyond stereotypes of adolescent risk taking: Placing the adolescent brain in developmental context. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 27, 19–34.

Tolou-Shams, M., Harrison, A., Hirschtritt, M.E., Dauria, E., and Barr-Walker, J. (2019). Substance use and HIV among justice-involved youth: Intersecting risks. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 16(1), 37–47.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (2017a). Sexual Risk Avoidance Education Program (General Departmental-Funded) Fact Sheet. Available: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/fysb/resource/srae-facts.

———. (2017b). About TPP. Available: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/grant-programs/teen-pregnancy-prevention-program-tpp/about/index.html.

———. (2017c). Underage Drinking Fact Sheet. Bethesda, MD: Author.

———. (2018a). Model on Risk Avoidance Theory and Research, Informing an Optimal Health Model, 2017 - Overview. Available: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/resource/model-on-risk-avoidance-theory-and-research-informing-an-optimal-health-model-2017overview.

———. (2018b). Adolescent Health: Think, Act, Grow® Playbook. Washington, DC: Author.

———. (2019a). Introducing the Optimal Health Model. Washington, DC: Author.

———. (2019b). National Youth Tobacco Survey. Available: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-source/national-youth-tobacco-survey.

———. (2019c). National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Available: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2018). Procedure Manual. Available: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/procedure-manual.

Wahlstrom, D., Collins, P., White, T., and Luciana, M. (2010). Developmental changes in dopamine neurotransmission in adolescence: Behavioral implications and issues in assessment. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 146–159.

World Health Organization. (2006). World Health Organization Youth Violence and Alcohol Fact Sheet. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

This page intentionally left blank.