6

Evaluating Clinical Practice Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Acute Pain

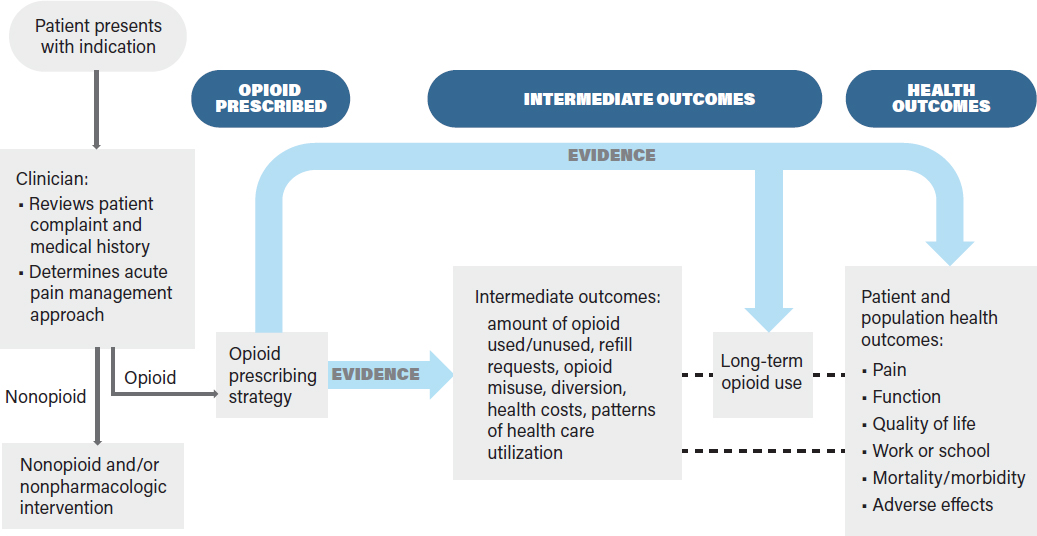

In Chapter 4 the committee proposed an analytic framework that professional societies, state and federal policy makers, health care systems, payers, and key stakeholders could consider when developing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for prescribing opioids for acute pain associated with surgical or medical indications. The analytic framework is for opioid prescribing strategies only and is based on the assumption that a clinician has already determined that opioids are needed for acute pain management. However, this framework does not exclude the consideration and use of nonopioid options, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic, with or without opioid analgesics.

In Chapter 5 the committee identified priority surgical and medical indications for which CPGs should be developed or improved. These indications are associated with acute pain episodes and were prioritized according to the prevalence of the indication—which was used as a proxy for the indication’s public health impact—and evidence that opioids play a role in acute pain management for these indications. In addition, the committee ascertained whether evidence-based CPGs were publicly available for any of the indications. If a CPG did not exist, other forms of guidance were considered.

In this chapter, the committee addresses its task of evaluating existing opioid prescribing guidelines for acute pain for selected indications from Chapter 5, against the analytic framework presented in Chapter 4. To do this, the committee identified seven indications—three surgical procedures and four medical conditions—that have public health impact, have some guidance and evidence regarding opioid prescribing, and were different in scope and context, to determine how the analytic framework might be applied to a range of indications that affect different populations. The three surgical procedures—cesarean and vaginal delivery, third molar (wisdom tooth) extractions, and total knee arthroplasty (TKA)—and the four medical conditions—renal stones, migraine headaches, low back pain, and sickle cell disease—differentially affect children, adolescents, adults, older populations, women of reproductive age, and minority populations. Evaluating any CPGs and other existing guidance chosen for each indication allowed the committee to identify opportunities for data optimization and research gaps for prescribing opioids.

The committee recognized that its task is predicated on the determination that opioids will be prescribed for acute pain for a given indication. However, in clinical practice the decision to use opioids

for acute pain often is made in the context of a comprehensive treatment plan tailored to an individual patient. Ideally, such a treatment plan considers the patient’s health status (obtained from a patient interview and review of the patient’s health record), including pre-existing conditions, comorbidities, prior reactions to opioids and other pharmaceuticals, treatment preferences, and the availability of and access to all recommended treatments. The comprehensive treatment plan for acute pain may include opioids alone or in conjunction with nonopioid and nonpharmacologic treatments prior to, concurrent with, or following the use of opioids. These other treatments may include heat, ice, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), massage, and acupuncture, among others, depending on the specific indication and patient preferences. Patient education may also occur prior to prescribing opioids to ensure the patient understands his or her risks and benefits and is able to take the drug as prescribed. To acknowledge this need for a comprehensive treatment plan, the committee added the need for the clinician to consider the patient’s medical history and to develop an acute pain management approach to its analytic framework, as shown in Figure 6-1. A CPG would consider evidence for all aspects of Figure 6-1 in order to provide an accurate and effective recommendation on opioid use and dosing for the treatment of acute pain for the indication. Should the opioids not provide the expected pain relief or if unexpected adverse effects occur, the clinician may reevaluate the patient to determine if the diagnosis is correct and if other treatments are warranted.

APPLYING THE ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK TO SELECTED SURGICAL INDICATIONS

The committee selected three surgical procedures on which to apply its analytic framework: cesarean and vaginal delivery, third molar (wisdom tooth) dental extractions, and TKA. These indications were

selected because they represent varied patient populations (e.g., women, adolescents, and older individuals) and are performed in different settings (e.g., inpatient or outpatient care). Moreover, across these procedures the majority of patients undergoing them are prescribed opioids for immediate postsurgical pain. Access to care and prescribed opioids may also vary for each of these procedures, depending on the patient’s comorbidities, finances, health insurance, geography, and the care provider.

Cesarean and Vaginal Delivery

Childbirth is the most common reason for hospital admission and the most common procedure in the United States, with 3,855,500 births in 2017 (CDC, 2017a). Of these, approximately 32% (1,233,760) are cesarean deliveries and 68% are vaginal deliveries (2,621,740); of the latter, it is estimated that about 9% will have a severe perineal laceration (ACOG, 2016). In one study, opioids were prescribed for 86.7% of 3,288 women who delivered by cesarean delivery, with a median dose of 300 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) (interquartile range, 200–300); of the women who had a vaginal delivery, 30.4% were prescribed opioids at discharge with a median dose of 200 MMEs (interquartile range, 120–300) (Badreldin et al., 2018b). The amount of opioids prescribed for either delivery did not vary between women with a pain score of 0 of 10 and those with a pain score greater than 0 of 10 immediately prior to discharge. Bateman et al. (2017) found that among 720 women admitted to a hospital for cesarean delivery, 615 (85.4%) filled a discharge prescription for opioids. Mills et al. (2019) examined opioid prescribing data at discharge for women with uncomplicated vaginal delivery and found that almost 30% received opioids on the day of discharge; by contrast, Komatsu et al. (2018) found that fewer than 10% of women with vaginal deliveries used opioids after discharge. Compared with women in other countries, including Canada, Germany, and Sweden, patients in the United States were far more likely to receive opioid prescriptions after vaginal and cesarean delivery (Wong and Girard, 2018).

The committee chose childbirth as a priority procedure because of the prevalence of the procedure, the prevalence of opioid prescribing, the evidence of over-prescribing (Badreldin et al., 2018a), and the risk of persistent use of opioids after discharge (Peahl et al., 2019). The committee also notes that there is the potential for exposure of infants to opioids through breast milk (Ito, 2018). The committee applied its analytic framework to vaginal and cesarean deliveries to highlight how standardized methodology for CPG development may help identify the most effective opioid prescribing strategies along with the intermediate and health outcomes that may be associated with that prescribing.

Opioid Prescribing Guidelines

Although there is no evidence-based guidance that is labeled as a CPG and addresses opioid prescribing after vaginal or cesarean delivery, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG’s) Committee Opinion on Postpartum Pain Management makes a number of recommendations on the use of acetaminophen and NSAIDs, reserving opioid use for breakthrough pain (ACOG, 2018). The opinion recommends a shared decision-making model to optimize pain control and minimize unused opioid pills (ACOG, 2018).

The ACOG opinion paper (2018) provides a synopsis of the evidence that the authoring committee used to reach its recommendations, but this committee does not consider the opinion paper to be a CPG and recognizes that it is not intended to be. The ACOG committee collaborated with representatives of the American College of Nurse-Midwives and the American Academy of Family Physicians in developing its opinion paper. A conflict of interest statement is included.

In addition to the opinion paper, ACOG frequently publishes a number of practice bulletins, which are “evidence-based documents that summarize current information on techniques and clinical management issues.”1 To date, none of the bulletins apply to opioid prescribing at discharge after cesarean or vaginal delivery. The ACOG practice bulletins, unlike the committee opinions, address specific questions and have an in-depth presentation of supporting evidence for recommendations and conclusions. The recommendations are rated as Level A (good and consistent scientific evidence), Level B (limited or inconsistent scientific evidence), or Level C (primarily consensus and expert opinion). The practice bulletins also contain brief synopses of the literature search and discussions of how the subsequent articles were reviewed. For example, they were reviewed and evaluated for quality according to the method outlined by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (see ACOG, 2016). In contrast, the recommendations in the committee opinions are not rated, nor is there any information as to how the evidence was reviewed or obtained. In the sections below, this committee considers what evidence gaps need to be addressed to develop evidence-based CPGs for vaginal and cesarean deliveries.

Patient Populations

Patients who undergo cesarean or vaginal delivery may experience a variety of types and intensity of pain during the early postpartum period. The AGOC committee opinion paper distinguishes pain management for vaginal versus cesarean deliveries. Special consideration is given to women who experience postpartum pain while breastfeeding, have opioid use disorder, have chronic pain, or are using other medications or substances that may increase sedation. Clinicians are referred to an AGOC committee opinion on opioid agonist pharmacotherapy for women with opioid use disorder, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CPG on chronic pain (Dowell et al., 2016), and the National Academies report on pain management, which has information for women with chronic pain (NASEM, 2017). Considerations regarding opioid prescribing for other pre-existing or comorbid conditions are not discussed, although the ACOG committee recognizes that the range of health and socioeconomic statuses among women who give birth may require opioid prescribing be modified to address an individual’s physical and mental health, comorbidities, and home environment.

ACOG also has a committee opinion paper on Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy (ACOG, 2017), which briefly discusses the use of opioids in postpartum women who used opioids during pregnancy, with a focus on breastfeeding. The opinion paper distinguishes among women who use opioids for medical reasons, who misuse opioids, and who have untreated opioid use disorder. ACOG also acknowledges that women who are ultra-rapid metabolizers of codeine may require close monitoring from their clinicians.

Most women who give birth are opioid naïve, having not filled an opioid prescription in the year prior to delivery, but they may have had varying degrees of opioid exposure prior to pregnancy. In addition, women may have various risk factors for prolonged opioid use following delivery, including pain disorders, mood disorders, and a history of substance use disorders (NIH, 2017; Osmundson et al., 2019; Sanmartin et al., 2019a,b).

Nonopioid Pain Management Strategies

The ACOG committee opinion paper recommends a stepwise nonopioid approach to postpartum pain management after vaginal or cesarean births, including both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic

___________________

1 See https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Bulletins-List (accessed August 28, 2019).

therapies. For vaginal births, the first step is acetaminophen or an NSAID. ACOG states that the most common sources of acute pain following vaginal delivery are breast engorgement, uterine contractions, and perineal laceration, which may be treated with nonpharmacologic modalities and mild anti-inflammatory analgesics.

ACOG does not comment on the use of either acetaminophen or NSAIDs as a first step for cesarean births.

Opioid Prescribing Strategies

The 2018 ACOG committee opinion paper states that if analgesics are insufficient for pain management following a vaginal birth, then milder short-acting opioids in combination with acetaminophen may be an effective second step for pain control while the woman is in the hospital (ACOG, 2018). It further states that using an NSAID and acetaminophen simultaneously on a set schedule with milder opioids, if needed, is preferred over opioid/acetaminophen combinations (two pills containing a maximum dose of 325 mg acetaminophen, administered every 4–6 hours) for vaginal births and cesarean deliveries. Overall, oral opioids should be reserved for breakthrough pain.

With regard to opioid use for postoperative pain following cesarean delivery, the ACOG committee opinion recommends the use of neuraxial opioids supplemented by oral acetaminophen, NSAIDs, opioids, and opioids in combination with either acetaminophen or an NSAID, but it does not specify if this includes pain control at discharge. Oral opioids should be reserved for breakthrough pain (ACOG, 2018). ACOG does not identify the number of pills or duration of opioid treatment to be prescribed at discharge, although it acknowledges that over-prescribing has been documented. It cautions that under-prescribing and inadequate pain control are also of concern and are best approached on an individualized basis. Finally, the ACOG opinion paper recommends that if an opioid is prescribed for postpartum pain, the duration should be limited to the “shortest reasonable course expected for treating acute pain” (p. e39).

The committee notes that a number of opioid prescribing strategies have been recommended for acute pain following vaginal or cesarean birth. However, some of the studies were published after the ACOG opinion paper and thus could not be included in it. Some of these studies are briefly reviewed to highlight the types of evidence that might be considered and graded for an updated ACOG opinion paper or for the development of a practice bulletin on postpartum pain.

Mills et al. (2019) developed expert panel consensus guidelines for opioid prescribing following uncomplicated vaginal births. Using a Delphi approach, the panel recommended that the lowest dose of immediate-release opioids should be used for the shortest period of time for acute pain; however, the type, dosage, and duration of opioid were not specified. A Johns Hopkins expert panel also concluded that opioids should not be routinely prescribed following an uncomplicated vaginal birth (Overton et al., 2018). Of note, these were not evidence-based guidelines and did not assess patient-reported outcomes.

With regard to cesarean delivery, the Johns Hopkins expert panel recommended that opioid-naïve patients be prescribed 0–10 pills of 5 mg oxycodone at discharge. Prabhu et al. (2017) found that in using a shared decision approach to opioid prescribing at discharge, women undergoing cesarean sections preferred to have 20 5 mg oxycodone pills prescribed rather than the standard prescription of 40 pills. The women in this study had a median of four unused pills at 2 weeks postdischarge and 90% (45 of 50) of them reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their outpatient pain management. These results are similar to those obtained by Bateman et al. (2017).

When an intervention to reduce prescribing following cesarean delivery was implemented (no preordered opioids while hospitalized), the use of opioids in the hospital was reduced from 68% to 45% by optimizing NSAID and acetaminophen use; at discharge only 40% received an opioid prescription,

compared with the preintervention rate of 91% (Holland et al., 2019). It is important to note that the discharge opioid prescription was based on inpatient use and shared decision making between the patient and prescriber in which patients could choose the number of pills they were prescribed up to a defined limit. A limitation of this study is that women were not interviewed regarding pain scores after discharge.

Intermediate Outcomes

There are robust data indicating that opioids are over-prescribed following childbirth. For example, approximately 75% of patients have unused opioids following cesarean delivery (Osmundson et al., 2017). On average, about 50% of opioids prescribed following cesarean delivery are unused, with 40 pills prescribed (various opioids) and 20 used (Bateman et al., 2017). Badreldin et al. (2018b) found that 45.7% of women after vaginal delivery and 18.5% of women after cesarean delivery who received an opioid prescription used 0 MME during the final hospital day. These data are in contrast to a small study by Osmundson et al. (2017) that found that 83% of women who had cesarean sections used opioids after discharge for a median of 8 days, and of the women who filled their prescriptions, 75% had unused pills (median per person 75 MME).

In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Osmundson et al. (2018) found that individualized discharge opioid prescriptions based on an algorithm that correlated inpatient opioid use with postdischarge opioid use resulted in a greater than 50% reduction in the number of opioid pills prescribed at discharge after cesarean birth as compared with standard prescribing (average 14 pills versus 30 pills). Women in the individualized prescription group had 50% fewer unused pills and used only half the number of prescribed opioids than the standard group (8 pills versus 15 pills); patient-reported pain outcomes did not differ between the two groups. Prabhu et al. (2018) implemented a two-step strategy that decreased the usual discharge prescription following cesarean from 40 pills (5 mg oxycodone) to a maximum of 30 pills in the first patient education phase and to a maximum of 25 pills in the second phase, for an overall 35% reduction in the number of opioid pills prescribed, without an increase in refill requests (5–8%).

The ACOG opinion paper does not discuss intermediate outcomes such as unused pills, refill requests after discharge, or long-term opioid use. However, ACOG acknowledges that one of the reasons for making its recommendations is that 1 in 300 opioid-naïve patients exposed to opioids after cesarean birth will become a persistent opioid user (this estimate is taken from Bateman et al., 2016). Similar data are not given for vaginal births.

Health Outcomes

The ACOG opinion paper discusses health outcomes for the recommended analgesic therapies, including their effectiveness, possible adverse effects, and impacts on breastfeeding and comorbidities. In general, however, the health outcomes are not linked to specific opioid dosing. ACOG emphasizes that therapy should be individualized to each patient.

The committee notes that both short- and long-term health outcomes are concerns following discharge opioid prescribing. In a study of functional recovery following childbirth, pain- and opioid-free functional recovery occurred at a median of 20 days following vaginal delivery (opioid cessation occurred at a median of 0.5 days, with pain resolution at 15 days); on the other hand, following cesarean delivery, complete functional recovery did not occur until a median of 27 days (8 days for opioid cessation and 21 days for pain resolution) (Komatsu et al., 2018).

Of note, the risk of overdose in young children (median age 2 years) is markedly increased (odds ratio [OR]=2.41, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.68–3.45) when the mother had received a prescription opioid in the preceding year (Finkelstein et al., 2017).2

Data Gaps and Research Needs

The committee identified several studies on specific opioid prescribing strategies used for vaginal or cesarean births and on the relationship of specific prescribing strategies with intermediate and patient outcomes. Areas where further research might be helpful for assessing long-term health outcomes include the use of opioids in patients with chronic opioid use, opioid use disorder, and indirect adverse effects on children in the home, including the effects on infants of mothers taking opioids while breastfeeding.

The committee found several studies of institution-specific quality improvement (QI) initiatives to reduce inappropriate postpartum opioid prescribing (Burgess et al., 2019; Holland et al., 2019; Prahbu et al., 2018). These studies documented a reduction in the opioid pills prescribed after the QI intervention and frequently, but not always, included data on patient-reported outcomes. Further information on opioid refills obtained outside the delivery hospital system and long-term outcomes would also be useful.

Third Molar Extraction

Opioid prescriptions for acute pain management after third molar extractions represent a significant proportion of opioid prescribing by dentists. It is estimated that 7–10 million third molar extractions are performed annually, making this procedure one of the most common procedures in dentistry associated with opioids for acute pain management (Friedman, 2007).

Baker et al. (2016) found that among a national sample of Medicaid patients (mean age 24.9 years) who underwent dental extraction between 2000 and 2010, 42% had filled an opioid prescription within 7 days of the procedure; hydrocodone was the most commonly prescribed opioid (78%). Early exposure to opioids in this population may increase the risk of persistent use and possible abuse, particularly in young females (Schroeder et al., 2019).

Dentists have traditionally managed postoperative pain after tooth extraction using NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and short-duration opioids (33–140 MMEs) (Gupta et al., 2018). The overall short-acting opioid prescribing rate of dentists since 2005 has been in the range of 12–18.5% (median of 16.5%) for all dental procedures according to nationwide studies (Gupta et al., 2018; Levy et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2006). In a study of opioid prescribing practices by dentists in South Carolina, however, the percentage of all initial opioid prescriptions after dental procedures was 45% (McCauley et al., 2016). Thus, regional variations exist for opioid prescribing practices by dentists.

There is evidence that a filled opioid prescription after third molar extractions increases the risk of persistent opioid use among opioid-naïve users aged 16–30 (Harbaugh et al., 2018). Furthermore, using 13- to 15-year-olds as a basis of comparison, the likelihood of persistent opioid use increased with increasing age (OR=1.39, 95% CI 1.01–1.91 for 16- to 18-year-olds; OR=2.13, 95% CI 1.55–2.92 for 19- to 24-year-olds; and OR=2.85, 95% CI 1.87–4.34 for 25- to 30-year-olds).

The committee chose third molar extraction as a priority surgical procedure for which a CPG might be developed because of the patient populations that are affected (e.g., adolescents and young adults), the high prevalence of the procedure, and the data that document the efficacy of nonopioid pain management strategies for this procedure.

___________________

2 This text has been revised since prepublication release.

Opioid Prescribing Guidelines

Currently, there are no evidence-based CPGs that specifically address opioid prescribing for the management of acute pain after third molar extractions. Both the American Dental Association (ADA) and the American Association for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) provide some guidance for opioid prescribing, but they both defer the specific prescribing details to the best clinical judgment of the dental practitioner. The ADA Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry does not have any guidelines for pain control. However, the ADA website3 contains two statements that pertain directly to opioids: the 2018 Policy on Opioid Prescribing and the 2016 Statement on the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Dental Pain. The statement recommends “consideration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics as the first-line therapy for acute pain management” but does not specify the type, release duration, or dosage of opioids to be considered for breakthrough pain (ADA, 2016). The statement also recommends that dentists follow and continually review CDC and state licensing board recommendations for safe opioid prescribing, as well as register with and make use of prescription drug monitoring programs. The policy states that “ADA supports statutory limits on opioid dosage and duration of no more than 7 days for the treatment of acute pain, consistent with CDC evidence-based guidelines” (ADA, 2018). There is no supporting documentation for any of these recommendations, nor is there a description on how the recommendations were derived. The committee did not consider these statements to meet the criteria for CPGs described by the 2011 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. The committee notes that in 2015 ADA also developed The ADA Practical Guide to Substance Use Disorders and Safe Prescribing, and it has a number of webinars that provide more detailed information on specific aspects of opioid use in dentistry. Because the webinars are not CPGs, the committee did not consider them for this report.

The AAOMS white paper Opioid Prescribing: Acute and Postoperative Pain Management has a similar recommendation regarding NSAIDs as a “first-line analgesic therapy” and also states, “When indicated for acute breakthrough pain, consider short-acting opioid analgesics. If opioid analgesics are considered, start with the lowest possible effective dose and the shortest duration possible” (AAOMS, 2017).

The Center for Opioid Research and Education (CORE) Dental Opioid Guidelines, developed by a multidisciplinary consortium of dentists, periodontists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, endodontists, and patients, used a modified Delphi approach to make recommendations for a stepped approach to treating acute pain in opioid-naïve patients undergoing any of 14 common dental procedures (CORE, 2018). For third molar extractions, CORE recommends that pain treatment begin with 1 g acetaminophen or 400 mg ibuprofen every 8 hours and, if needed, the maximum amount of opioids prescribed may be 15 5 mg oxycodone pills at discharge, based on the clinician’s assessment of the patient’s pain needs.

The committee selected ADA’s guidance on opioid prescribing as the basis for its evaluation of the analytic and evidence frameworks presented in Chapter 4 because ADA has a large membership whose members prescribe opioids and it has been engaged in the opioid overdose epidemic for several years.

Patient Populations

The ADA website contains little information on the patient populations that may be prescribed opioids. The 2016 ADA Statement on the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Dental Pain recommends, “When considering prescribing opioids, dentists should conduct a medical and dental history to determine current medications, potential drug interactions, and history of substance abuse.” The ADA Practical Guide to

___________________

3 See https://www.ada.org/en/advocacy/current-policies/substance-use-disorders (accessed August 28, 2019).

Substance Use Disorders and Safe Prescribing has “techniques for managing dental pain for those who may be at risk for substance dependence” (ADA, 2015). However, the committee notes that this is a relatively small population compared with the number of people who have third molar extractions. In addition, the webinars on the ADA website have information regarding opioid prescribing in adolescents.

The lack of information on opioid prescribing for various patient populations undergoing third molar extractions is of concern because the patient population is predominantly between the ages of 15 and 25 years and those patients are typically opioid naïve.

Nonopioid Pain Management Strategies

The ADA Statement on the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Dental Pain states that “dentists should consider nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics as the first-line therapy for acute pain management” and “recognize multimodal pain strategies for management for acute postoperative pain as a means for sparing the need for opioid analgesics” (ADA, 2016).

The committee notes that there is an abundance of strong evidence that NSAID/acetaminophen combination therapy is more efficacious than opioid therapy for acute pain after third molar extractions, with fewer side effects (Moore et al., 2018). Acute pain management after third molar extractions has been shown to respond to nonopioid medications, such as NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen or diclofenac) combined with acetaminophen, for pain relief equivalent to short-acting opioids. However, NSAIDs may be contraindicated in some patients, such as those with kidney or liver diseases. These nonopioids may be combined with physical modalities (ice/heat) and behavioral management for pain management (AAPD, 2018; Abdeshahi et al., 2013). Patients with breakthrough pain should be re-evaluated for other causes of pain such as infection or alveolar osteitis (dry socket). Excluding these causes, consideration of a short-acting opioid for a short duration may be indicated.

The committee recognizes that the adoption and incorporation of these alternatives to opioid prescribing in dentistry has been slow. The result has been dentists prescribing excess amounts of opioids after third molar extraction, resulting in some that are unconsumed (Mutlu et al., 2013), which allows for potential opioid diversion (Ashrafioun et al., 2014).

Opioid Prescribing Strategies

The 2018 ADA Policy on Opioid Prescribing states that “ADA supports statutory limits on opioid dosage and duration of no more than 7 days for the treatment of acute pain, consistent with CDC evidence-based guidelines.” Further information on why ADA supports this recommendation is not provided.

The committee finds that there is a paucity of prescribing strategies for the opioid management of acute pain after third molar extraction. Because third molar extraction pain typically lasts 3 to 5 days after the procedure, a prescription for 7 days of opioids may result in over-prescribing. Although short-acting, short-duration strategies for opioid dosing have been successful (Moore and Hersh, 2013), data on the specific dosing levels and duration have not been adequately evaluated.

Intermediate Outcomes

Neither the ADA Policy on Opioid Prescribing nor the ADA Statement on the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Dental Pain provides information on any intermediate outcomes associated with opioid prescribing, such as the amount of opioids used for acute pain management.

A recent prospective study reported that patients used less than half of the prescribed opioids to manage their pain and reported more side effects when using opioids than when using nonopioid alternative medications (Maughan et al., 2016). However, most studies have been retrospective examinations of combined insurance and prescription databases on such outcome measures as the type of opioid and the strength and duration of prescriptions. The committee notes that one limitation to studies that use these data is that not all patients who have third molar extractions are represented because some patients may not have insurance that covers the procedure.

Health Outcomes

Neither the ADA Policy on Opioid Prescribing nor the ADA Statement on the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Dental Pain provides information on any health outcomes associated with opioid prescribing for acute pain following third molar extraction.

The committee notes that the need for the long-term management of postextraction pain using opioids is minimal, a fact that is reflected in the lack of literature evaluating long-term health outcomes. Other sequalae subsequent to the extraction that may cause pain and require management include chronic infection and nerve injury. These sequalae require nonopioid, alternative approaches that are appropriate for managing these conditions (Bouloux et al., 2007).

Data Gaps and Research Needs

Opioids are commonly prescribed for third molar extractions, but the appropriate prescribing strategies for the typically young, opioid-naïve patients have not been studied. Additional research is needed to establish appropriate dosages because there is evidence that patients have different responses to pain due to, for example, their sex, age, history of substance use disorder, or history of persistent pain, and thus may require higher or lower doses to successfully manage their pain.

Health outcomes after short-term opioid use for third molar extraction pain have received minimal attention and represent another evidence gap. Further research is needed to identify the effects of opioids on such outcomes as the quality of life, the risk of substance use disorder, chronic opioid use, function, and mortality. This information would be useful in the acute pain management discussions between the prescriber and patient prior to third molar extractions.

Total Knee Arthroplasty

TKA, or knee replacement, is commonly performed in the United States for the treatment of symptomatic osteoarthritis, and opioids are typically prescribed for postoperative pain (Murphy and Helmick, 2012). The committee chose TKA as a priority surgical procedure for which a CPG might be developed because TKA is a relatively common procedure, procedure rates have increased in recent years, postoperative opioid prescribing is standard practice, opioid-naïve patients at the time of surgery are at risk for chronic opioid use, and a substantial proportion of patients undergoing TKA have current or recent opioid exposure.

In 2014 there were more than 752,900 knee arthroplasty procedures, making it the third most frequent operating room procedure (rate of 236.1 per 100,000 people) (McDermott et al., 2017). Moreover, given the aging population, TKA rates are expected to increase. Sloan et al. (2018) projected that the number of TKAs performed in the United States will grow by 85% to 1.26 million procedures by 2030, on the basis of 2000–2014 data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the National Inpatient Sample developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

Most patients undergoing TKA receive opioids for postoperative pain control. An analysis of health insurance administrative claims found that 72.0% of opioid-naïve patients undergoing TKA between 2007 and 2016 filled an opioid prescription, while 84.2% of sporadic opioid users and 95.9% of chronic opioid users filled an opioid prescription after surgery (Cook et al., 2019). Opioid prescribing varies considerably following TKA (Holte et al., 2019; Kahlenberg et al., 2019; Sabatino et al., 2018). For example, Sabatino et al. (2018) found that patients who underwent TKA were prescribed a median of 90 5 mg oxycodone equivalent opioid pills, with the number ranging from 10 to 200 pills. The extent to which opioids are under- or over-prescribed following TKA is unclear. Approximately 67% of patients received at least 1 refill, for a total mean number of pills prescribed of 176.4±108.0 (range, 10–480); the mean number of unused pills at 90 days was 29 (Sabatino et al. 2018).

The trajectory of opioid use following TKA varies by patient factors and prior opioid exposure. In a study of insurance claims (Bedard et al., 2017), the percentage of patients filling an opioid prescription fell from 69.3% patients in the first month after TKA to 24.9% at 3 months and to 14.9–16.3% at 6–12 months after surgery. Among opioid-naïve patients, 10.2%, 4.0%, and 3.3% were using opioids at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. In contrast, patients who were using opioids at the time of surgery were more likely to continue to fill prescriptions in the months following surgery, with 50.4%, 38.3%, and 33.2%, doing so at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. In addition, patients younger than 50 years and female patients were more likely to continue to fill prescriptions. Patients with anxiety, depression, low back pain, myalgia, and drug or alcohol dependence or who used tobacco were also more likely to continue filling prescriptions. Finally, Goesling et al. (2016) noted that among opioid-naïve patients, continued opioid use at 6 months was correlated with greater overall body pain, greater joint pain, and catastrophizing reported by patients on the day of surgery.

Importantly, there is growing evidence that opioid prescribing after TKA can be reduced without compromising pain control. In an RCT, 304 arthroplasty patients received either 30 or 90 5 mg oxycodone pills at discharge. The lower dose arm had fewer unused pills at 30 days postoperatively, with no difference in pain score. There was also no difference in patient-reported outcomes at 6 weeks. At 90 days, the lower dose arm also had lower mean MMEs prescribed, with no difference in the number of MMEs consumed (Hannon et al., 2019). Two single-institution QI initiatives also suggested that opioids are currently over-prescribed after TKA. Holte et al. (2019) found that implementing a strict opioid prescribing guideline after TKA resulted in a decline in the initial opioid prescription, the number of refills, and the total postoperative dose. Kahlenberg et al. (2019) reported that after implementation of a new opioid prescribing guideline, which set a limit of 70 pills after total joint replacement, the mean number of pills prescribed decreased from 91±26.6 pills to 65±16.3 pills, and the number of postoperative telephone encounters also decreased (the authors noted that most postoperative calls are typically to nurse practitioners for prescription refills). Neither of these QI reports contacted patients postoperatively about pain or unused pills or opioids prescribed beyond the surgical providers.

Opioid Prescribing Guidelines

In 2015 the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) published Surgical Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline, which was endorsed by several professional societies, including the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. This CPG does not specifically mention opioid use for acute pain after TKA, but it does make strong recommendations for the inpatient use of the pain management techniques of peri-articular local anesthetic infiltration, peri-articular nerve blockade, and neuraxial anesthesia to decrease opioid use when performing orthopedic procedures (Weber et al., 2016). The CPG contains both inclusion and exclusion criteria

for the evidence base, and it follows a pre-established protocol for CPG development that tracks closely with the procedures recommended in the 2011 IOM report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust and the rationale of the USPSTF for making expert opinion-based recommendations.

Additionally, in 2015 AAOS also published an information statement supporting the standardization of opioid prescription protocols and policies in all settings to control and limit opioid prescription use and dose (AAOS, 2015). The information statement recommends the following strategies for ensuring safe opioid prescribing:

- Establish ranges for acceptable amounts and durations of opioids to treat postprocedural pain, tailored to the intensity of the procedure (small, moderate, and large procedures);

- Avoid prescriptions from multiple providers, and coordinate prescribing with primary care or the usual prescribers for patients currently on opioids;

- Review prescription drug monitoring programs prior to prescribing;

- Avoid prescriptions for the treatment of chronic pain; and

- Have a strict limit of opioid prescription size that is expected to be appropriate to the pain.

Patient Populations

As discussed previously, approximately 30% of patients undergoing TKA are exposed to opioids at the time of surgery, and opioid requirements for opioid-exposed patients are often higher than for opioid-naïve patients (Bedard et al., 2017; Cook et al., 2019; Goesling et al., 2016). In addition, mental health conditions, overall body and surgical site pain, medical comorbidities, and tobacco and other substance use are correlated with greater opioid use following surgery (Bedard et al., 2017; Cook et al., 2019; Goesling et al., 2016). The AAOS CPG provides evidence and recommendations on risk factors that may affect postoperative outcomes, including the rates of complications, revision, function, and patient-reported outcomes. These risk factors include body mass index, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, liver disease, chronic pain), compliance with preoperative therapy, and depression and anxiety. However, the CPG examines only chronic pain as a risk factor for outcomes following surgery and does not specifically address preoperative opioid use.

Nonopioid Pain Management Strategies

The AAOS CPG for TKA identifies peripheral nerve blockage and peri-articular local anesthetic infiltration as best practices to enhance postoperative pain control, and it cites the supporting evidence and specifies its quality. For example, the CPG notes strong evidence (defined as two or more high-quality studies) to support the use of peripheral nerve block versus parenteral opioids alone to reduce postoperative opioid consumption, minimize opioid-related side effects, improve postoperative range of motion, and enhance patient-reported outcomes in the immediate postoperative period. Similarly, there is strong evidence to support the use of peri-articular infiltration of local anesthesia for postoperative pain control, as it was superior to a placebo in enhancing postoperative function, reducing opioid use, improving patient-reported pain, and increasing patient-reported satisfaction following TKA.

Concerning pharmacologic opioid alternatives, a recent systematic review indicates that NSAIDs offer similar relief to opioids for knee osteoarthritis (Smith et al., 2016). One meta-analysis examined the use of alternative therapies after TKA to reduce pain and opioid use (Tedesco et al., 2017). In that study, electrotherapy and acupuncture after TKA were associated with reduced and delayed opioid consumption, but continuous passive motion, preoperative exercise, and cryotherapy were not.

Opioid Prescribing Strategies

Opioids are routinely prescribed following TKA (Bedard et al., 2017). As noted earlier, numerous studies have examined opioid dosing for TKA and provide an evidence base to be considered when creating guidelines for postoperative opioid prescribing following TKA. The AAOS CPG does not specifically address opioid prescribing following TKA, although it does consider opioid use and pain control as outcomes by which other best practices should be examined. Although enhancing pain control and reducing opioid use are identified as optimal outcomes, the best practices in opioid prescribing are not described (e.g., use, dosing, and timing of opioid alternatives alongside opioid analgesics and the identification of patients at risk for poor pain- and opioid-related outcomes), and no information is given on the type of opioid, dosing, or duration that should be followed in the postoperative period.

The AAOS statements highlight the importance of clinician–patient discussions about pain—including the use of a pain relief toolkit to facilitate those discussions—and behavioral interventions to address “depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and ineffective coping strategies” (AAOS, 2015), but no further guidance on the latter intervention is given. This information is not included in the AAOS CPG.

Intermediate Outcomes

The committee identified several studies that have examined the intermediate outcomes following opioid use, including the amount of opioids prescribed and refilled and health care use for follow-up pain management such as telephone calls, emergency visits, and rehospitalizations. In addition to the previously mentioned 2019 studies by Hannon et al., Holt et al., Huang and Copp, and Kahlenberg et al., all of which found that opioids were over-prescribed after TKA surgery, long-term opioid use of up to 1 year following TKA surgery has also been described (Bedard et al., 2017). These studies typically obtained data from databases such as electronic medical records and administrative databases from health insurers. The results include, for example, the finding that opioid refills declined in the months following TKA, from 69% in the first month after surgery to 15–16% at 6–12 months after surgery (Bedard et al., 2017). Overall, approximately 8% of opioid-naïve patients continue to use opioids at 6 months, compared with roughly 53% of opioid-exposed patients (Goesling, 2016). Importantly, patients with preoperative opioid exposure also reported less pain relief following TKA (Smith et al., 2017). Approximately 60% of patients require refills of opioids, and the refill rates are lower among patients with optimal pain control in the hospital prior to discharge (Wilke et al., 2019).

The AAOS CPG does not address any intermediate outcomes for opioid dosing, although it does state that the use of its recommended pain management techniques may reduce opioid use.

Health Outcomes

Many of the studies described previously did not analyze patient-reported health outcomes such as pain reduction, function, or return to work or other activities. A few studies, however, have interviewed patients at varying times after surgery to ascertain pain status (Huang and Copp, 2019).

Studies using only administrative data do not capture patient-reported outcomes such as pain, opioid use, and satisfaction; however, recent studies have examined the effect of reductions in opioid prescribing on patient outcomes following TKA. For example, in an RCT Hannon et al. (2019) compared 30 or 90 pills of oxycodone following TKA and total hip arthroplasty and found that smaller opioid prescriptions reduced the number of unused pills but made no difference in patient-reported pain (Hannon et al., 2019). Similarly, Huang and Copp (2019) examined 51 consecutive patients undergoing TKA and noted over-prescribing by 34% compared with the amount used and the pain reported.

The 2015 AAOS CPG does address best practices specific to postoperative outcomes including complications, readmissions, revision rates, functional outcomes, and patient-reported outcomes, which indirectly address pain and opioid use following surgery. The guidelines include such statements as “Moderate evidence supports that patients with select chronic pain conditions have less improvement in patient reported outcomes with TKA.” However, the AAOS CPG has no recommendations on opioid prescribing at discharge. It does have strong recommendations regarding perioperative interventions and immediate postoperative outcomes. For example, the CPG states, “Strong evidence supports that peripheral nerve blockade for TKA decreases postoperative pain and opioid requirements.” Four studies are cited that compared opioids with nerve block in terms of patient outcomes; the assessments were made on the first postoperative day, and long-term opioid use and pain outcomes were not well characterized.

Data Gaps and Research Needs

The committee considered the available evidence and guidelines, including expert testimony at the committee’s public sessions, and identified the following evidence gaps. First, it has been suggested that there is a need for multicenter prospective studies using common definitions of key terms and data elements and a standardization of multimodal perioperative pain programs (David Jevsevar, Dartmouth, personal communication, July 9, 2019). In addition, it will be critical to ensure appropriate and uniform risk adjustment for baseline predictor variables (e.g., prior opioid exposure, medical comorbidities, mental health conditions, and social determinants of health). Jevsevar also suggested the greater use of quality improvement registries and longitudinal databases of large vertically integrated health systems that have high retention rates. Furthermore, Jevsevar called attention to patients who have additional types of pain and to polypharmacy in frail elderly patients as well as to the importance of the settings of care, including site of surgery and discharge location. The committee concurs with these ideas and notes that other research gaps include risk stratification for complex pain and interventions to treat these individuals.

The committee also identified evidence gaps in intermediate outcomes (e.g., opioid use disorder) and patient-reported health outcomes (e.g., function, quality of life). As noted above, the committee found evidence gaps regarding nonpharmacological pain treatments, including patient education and behavioral therapy (Tedesco et al., 2017). In light of the high prevalence of opioid use among patients before TKA, the committee found evidence gaps regarding co-management strategies among orthopedic surgeons, pain specialists, and primary care clinicians, particularly for opioid-exposed patients. Addiction medicine specialists may also be important to include for patients with opioid use or substance use disorders who are undergoing TKA surgery. Notably, the majority of opioid prescribers for patients with knee arthritis undergoing TKA may not be orthopedic surgeons; primary care and internal medicine physicians have been found to be the highest opioid prescribers before and after total joint arthroplasty (Namba et al., 2018). Moreover, nurse practitioners and physician assistants in orthopedic departments may also prescribe opioids postoperatively. This suggests that a collaborative effort to develop guidelines for opioid prescribing after TKA that includes input from these other prescribers would enhance the reach and impact of such a guideline and improve prescribing practices.

APPLYING THE ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK TO SELECTED MEDICAL INDICATIONS

The acute pain associated with surgical procedures is usually assumed to be time limited as the patient recovers from the surgery or procedure. However, the acute pain associated with many medical

conditions is much more variable and depends on the nature of the indication. For example, the acute pain associated with renal stones is typically limited to the time required for the stone to move from the kidney or ureter to outside the body. Once the renal stones are eliminated, the acute pain is expected to subside. The acute pain resulting from a sprained joint, broken bone, or strained muscle may also be expected to ease once the joint, bone, or muscle heals. Preventing acute pain from becoming chronic is an important consideration in pain management.

The committee chose four medical indications that are known to have acute pain episodes with which to assess its analytic framework for opioid prescribing: renal stones, migraine headache, low back pain, and sickle cell disease. Assessing these indications allowed the committee to determine whether the guidance available for each indication addressed issues such as acute versus chronic pain, specific opioid prescribing, other treatment modalities, population variations, and intermediate or health outcomes. Renal stones generally occur in a mature population and often result in emergency department (ED) visits. Migraine headaches may occur in both children and adults and are frequently treated in EDs, but may also be treated in primary care and specialty clinics. Acute low back pain is relatively common, can be debilitating, and may have a variety of causes that are difficult to diagnose. Sickle cell disease may also occur in both adults and children and affects predominantly black and, to a lesser extent, Hispanic populations. These indications provided a range of medical conditions and varying levels of clinician guidance to help the committee determine whether its analytic framework is broadly applicable to medical conditions.

Renal Stones

Renal stones are a common cause of acute pain. The terms renal stones, kidney stones, renal colic, and nephrolithiasis are used interchangeably to refer to the underlying obstruction in the urinary system that causes the pain. Stones may be composed of a variety of compounds, most commonly calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate (Türk et al., 2016). Based on data from the 2007–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of the U.S. population, the overall prevalence of kidney stones was calculated to be 8.8% (95% CI 8.1–9.5), 10.6% (95% CI 9.4–11.9) among men, and 7.1% (95% CI 6.4–7.8) among women. Compared with whites, blacks and Hispanics were less likely to report a renal stone (OR=0.37, 95% CI 0.28–0.49 and OR=0.60, 95% CI 0.49–0.73, respectively) (Scales et al., 2012). Almost 1 in 11 people in the United States experience renal stones at some point in their lives (Pearle et al., 2014).

Opioids are frequently prescribed for acute pain caused by renal stones. In the 2016 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), opioids were found to have been prescribed for more than 300,000 ED visits for patients diagnosed with renal calculus. Renal stones accounted for 2.1% of all ED visits at which opioids were prescribed at discharge (Schappert and Rui, 2019). In the 2010 NHAMCS, the diagnosis with the highest proportion of discharge opioid prescriptions was nephrolithiasis, with 62.1% of patients receiving an opioid prescription (Kea et al., 2016). In primary care clinics, Mundkur et al. (2018) found that renal stones were the eighth leading cause of opioid prescribing for acute pain, with 15.3% of patients receiving a prescription for opioids at the initial visit.

Opioid Prescribing Guidelines

Practice guidelines exist for acute pain caused by renal stones. In particular, the European Association of Urology (EAU) issued comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and management of renal stones in 2019.4 The committee also found that EAU developed its evidence-based guidelines for

___________________

4 See https://uroweb.org/guideline/urolithiasis (accessed June 27, 2019).

renal colic using a methodology that is consistent with the analytic and evidence frameworks described in Chapter 4. The EAU evidence summary for the management of renal colic declares, “Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are very effective in treating renal colic and are superior to opioids (Section 3.4.1.1), with the level of evidence rated as 1b.” The EAU guidelines made a strong recommendation to “offer a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory as the first drug of choice (Section 3.4.1.1).” The guidelines made a weak recommendation to “offer opiates … as a second choice,” with specific mentions of hydromorphone, pentazocine, or tramadol. EAU also issued guidelines on medical therapy to expel stones and on active stone removal through shock wave lithotripsy, ureteroscopy, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

Nevertheless, Europe and the United States differ with regard to clinical practice, the scale of opioid misuse, and attitudes toward pain relief with opioids. Moreover, the committee noted that several RCTs described in the EAU guideline for acute renal colic were carried out in other countries (e.g., Bansal et al., 2016; Ener et al., 2009) where clinical practice and cultural expectations regarding pain and relief of pain may differ from those in the United States. Thus, the committee did not consider the EAU guidelines to be appropriate for assessing its framework for opioid prescribing for acute pain from renal stones. A systematic review of studies on the prevention of renal stones in adults was performed for the American College of Physicians CPG, but it does not deal with treatment of pain caused by renal stones (Fink et al., 2013).

The American Urological Association (AUA) issued evidence-based guidelines for the medical management of renal stones in 2014 (Perle et al., 2014) and also for the surgical management of renal stones.5 The committee found that these guidelines were based on a systematic review of evidence and that the methodology of the evidence review and standards for guideline recommendations were consistent with the committee’s guideline development process and the evidence framework. However, these AUA guidelines did not consider the management of acute pain due to renal colic or the specific use of opioids. Moreover, the literature review for the medical management guideline was only through 2011, and key studies considered by the EUA guidelines were published after this date. Still, these guidelines demonstrate that AUA has a standardized process in place for developing evidence-based CPGs.

Patient Populations

Renal stones are more common in certain U.S. populations (Scales et al., 2012; Shoag et al., 2015). Between 1994 and 2010 the prevalence of renal stones increased and in 2010 was found to be 10.6% in men (95% CI 9.4–11.9) and 7.1% in women (95% CI 6.4–7.8). Blacks and Hispanics have a lower prevalence of renal stones than whites, although the prevalence among blacks rose by more than 150% during this period (Scales et al., 2012). The prevalence of renal stones has also risen among children and adolescents, and stones are more frequent among girls than boys, unlike the situation in adults (Shoag et al., 2015). Renal stones are more common among people with obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome; the increase in these conditions may be driving the increased prevalence of stones (Scales et al., 2012). Renal stones are also more common in people with a lower intake of fluids and dietary calcium.

Both of the AUA guidelines address the occurrence of renal stones in adults and children. Both guidelines also offer recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of renal stones based on the stone type and size. No other patient considerations are given in the guidelines.

___________________

5 See https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/kidney-stones-surgical-management-guideline (accessed June 27, 2019).

Nonopioid Pain Management Strategies

Because the management of acute pain is not considered in the AUA guidelines for the medical and surgical management of renal stones, and because consideration of other management strategies is outside the scope of the committee’s task, the committee was unable to assess the use of opioids for acute pain from renal stones. Nevertheless, the committee found numerous studies that have assessed the pharmacologic treatment of pain due to renal stones. Some of this evidence is briefly described below. These studies might provide a foundation for assessing pain management in future guidelines. The committee also notes, as described previously, that the EAU recommends NSAIDs to treat renal stones.

There is considerable evidence to support the use of nonopioid pharmacotherapies for renal stones. Pathan et al. (2018) carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 RCTs on the efficacy of NSAIDs, opioids, and paracetamol (acetaminophen) in the treatment of acute renal colic. In these trials, pharmaceuticals were generally administered intravenously or intramuscularly with a pain assessment conducted about 30 minutes later. The analysis concluded that, compared with opioids, NSAIDs had a marginal benefit for initial pain reduction at 30 minutes, required fewer rescue treatments, and had lower vomiting rates. NSAIDs and paracetamol did not differ in pain relief at 30 minutes, but NSAIDs required fewer rescue treatments. The review concluded that NSAIDs should be the preferred analgesic option for patients presenting to the ED with renal stones, despite heterogeneity among the included studies and the overall quality of evidence. The committee notes that the clinical outcome in these trials was pain relief at 30 minutes and not at discharge. The trials did not study patient-reported outcomes such as longer-term pain relief, function, ability to work, or quality of life.

The 2018 review by Pathan et al. included a large 2016 placebo-controlled RCT whose active arms were 75 mg of intramuscular diclofenac, 0.1 mg/kg of intravenous morphine, and 1 gram of paracetamol (Pathan et al., 2016). In the primary endpoint, reduction of initial pain by 50% or more at 30 minutes, diclofenac was statistically superior to morphine, and paracetamol approached statistical superiority over morphine. Diclofenac had a statistically significant lower frequency of rescue analgesia and persistent pain than the other arms. The study concluded that “intramuscular non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be safely used as the first-line treatment and offer the fastest, most effective, and sustained relief from renal colic presentations in the emergency setting” (p. 2000). The study has been criticized for using a fixed single dose of morphine rather than titrating the dose (Riou and Aubrun, 2016). Of note, the study was conducted in Qatar, and the median age of participants was 34.7 years. Hence, the committee notes that the findings may not be generalizable to the population of the United States. Pathan et al. (2018) reached conclusions similar to those in a 2005 Cochrane review (Holdgate and Pollock, 2005).

In addition, there is some evidence suggesting that nonpharmacological pain modalities may be effective in relieving acute pain from renal colic, and thus, might be part of a nonopioid and nonpharmacologic approach that could reduce the need for opioids (e.g., Ayan et al., 2013; Beltaief et al., 2018; Kaynar et al., 2015).

Opioid Prescribing Strategies

The AUA evidence-based guidelines for the medical management of renal stones (Perle et al., 2014) do not address acute pain management, with or without opioids.

The EAU guidelines for renal stones recommend clinicians “offer opiates (hydromorphine, pentazocine, or tramadol) as a second choice”; this recommendation is based on weak evidence. There is a further recommendation that pethidine be avoided for patients with renal stones. No further opioid dosing information is provided.

An important limitation of the clinical trials analyzed in evidence-based reviews is that opioids were generally used at a single fixed parenteral dose in EDs. This prescribing protocol is outside the scope of this report, which is focused on opioid prescribing for outpatients or at discharge.

Intermediate Outcomes

The AUA evidence-based guidelines for the medical management of renal stones (Perle et al., 2014) do not address intermediate outcomes that may be associated with prescribing opioids for acute pain management. The committee found no studies that address intermediate outcomes of opioids prescribed for acute renal colic, such as the number of pills used and the number left over or relief of pain several days after treatment.

Health Outcomes

The AUA evidence-based guidelines for the medical management of renal stones (Perle et al., 2014) do not address the health outcomes that may be associated with prescribing opioids for acute pain from renal stones. The committee found no reports of functional status, quality of life, or the ability to work or go to school after treatment with opioids or nonopioid interventions for acute pain from renal stones.

Shoag et al. (2019) analyzed NHANES data and found that patients reporting a greater number of passed stones were also more likely to report current opioid use. This relationship persisted when smoking and arthritis, which are known to be associated with opioid use, were taken into account in a multivariable analysis. The authors acknowledged the limitations of the cross-section survey design and their inability to verify the patient-reported history of renal stones.

Data Gaps and Research Needs

Single-dose NSAIDs are effective for the short-term relief of acute pain due to renal colic and are marginally more effective than parenteral opioids in fixed doses, and they have fewer adverse effects. Evidence is lacking from RCTs regarding prescribing opioids or other medications for renal colic. Additional research on QI initiatives to reduce opioid over-prescribing for acute pain from renal colic that assess pain relief several days after discharge from the ED, the dosage of unused opioid pills, or the need for opioid refills would also be helpful (e.g., Motov et al., 2018).

Migraine Headache

Migraine headaches can cause severe pain with significant disability. They are one of the top five pain conditions among 18–44-year-olds that are treated in EDs according to a 2011 national survey (Weiss et al., 2014),6 although the 2016 National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey did not include migraine headaches among the top 20 conditions for which opioids are prescribed in the ED (Schappert and Rui, 2019). Headaches are one of the top 10 conditions treated with opioids in primary care settings (Mundkur et al., 2018), but this categorization also included general headaches.

Migraine headache is common among people presenting for care for acute pain. The 1-year period prevalence of migraines is about 18% in women and 6% in men, with the prevalence peaking between the ages of 25 and 55 years (AHS, 2019). Migraines also occur in children and adolescents, with their prevalence increasing with age (1–3% in 3- to 7-year-olds, 4–11% in 7- to 11-year-olds, and 8–23% by

___________________

6 This text has been revised since prepublication release.

age 15 years) (Oskoui et al., 2019). In adults, migraines may be either episodic (fewer than 15 migraine or headache days in 1 month) or chronic (at least 15 monthly headache days with at least 8 monthly migraine days) (AHS, 2019). Diagnostic criteria for pediatric migraines include at least five headaches over the past year that lasted 2–72 hours when untreated, with requirements for additional features and associated symptoms (Oskoui et al., 2019).

A majority of migraine sufferers (approximately 52%) are seen in primary care settings, while 17% are treated in the ED (Burch et al., 2015). Acute migraine causes 1.2 million visits to EDs annually (Orr et al., 2016). The management of migraine headaches consists of preventive approaches using a wide variety of nonopioid medications and interventions (Silberstein et al., 2012).

The committee selected migraines for its assessment of its analytic framework because they are common, opioids are prescribed for them, and the diagnosis is sufficiently narrow to enable research to fill in data gaps. Despite the fact that opioids are not recommended for migraines as first-line therapy, they are frequently prescribed to patients presenting in emergency outpatient settings. Furthermore, headaches are one of the key conditions associated with a large rise in opioid prescribing in EDs (Dodson et al., 2018; Minen et al., 2018).

Opioid Prescribing Guidelines

Guidelines and supporting documentation for the pharmacological management of acute migraines have been published and updated by the American Headache Society (AHS)7 and the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) (Marmura et al., 2015). These guidelines promote the initial prescribing of a variety of nonnarcotic medications prior to prescribing opioids such as butorphanol for regular use. However, the adoption of these guidelines has been variable in clinical practice.

The 2000 report Practice Parameter: Evidence-Based Guidelines for Migraine Headache (an Evidence-Based Review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology (Silberstein, 2000) was based on four evidence-based reviews performed by Duke University and sponsored by AHRQ. Two of the reviews covered self-administered drug treatment for migraine and parenteral drug treatment for acute migraine. A technical review by AHRQ contains details of the methodology and grading of the evidence considered for the guideline; the technical review considered both the effect on headache pain and the tolerability of self-administered drug treatments for acute migraine headache compared to placebo, alternative drug treatments, and non-drug therapies in controlled trials (Gray, 1999). Efficacy and adverse events are also reported.

In 2018, the AHS Position Statement on Integrating New Migraine Treatments into Clinical Practice was released. Marmura et al. (2015) reviewed the evidence on which the AHS document and the Silberstein (2000) conclusions are based. Marmura et al. (2015) outlined their review process and how they rated the evidence. Their paper also states that the authors’ approach is “consistent” with that in the 2011 IOM report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust.

The AHS paper builds on AAN’s CPG (Silberstein, 2000). For the AAN guideline, seven organizations formed the U.S. Headache Consortium, which developed the document. Members of the consortium were identified, levels of evidence were graded, and the strength and quality of the evidence, scientific effect measures, and clinical impression of effect were defined. According to the AHS (2019, p. 3) position statement, “Input was … elicited from multiple stakeholders, including health insurance providers, employers, pharmacy benefit service companies, device manufacturers, pharmaceutical and

___________________

7 See https://americanheadachesociety.org/resources/guidelines/guidelines-position-statements-evidence-assessments-andconsensus-opinions (accessed August 28, 2019).

biotechnology companies, patients, patient advocates, and experts in headache medicine from North America and Europe.”

It is important to note that this guideline is specific to adults with migraines. However, a study using 2007–2008 commercial claims data of adolescents aged 13–17 years with two or more claims for a headache found that nearly half (46%) of the adolescents had received an opioid prescription (DeVries et al., 2014). On the date of the prescription, 24% had been diagnosed with a migraine, and nearly one-third (29%) received three or more opioid prescriptions during the study’s observation period. The Practice Guideline Update Summary: Acute Treatment of Migraine in Children and Adolescents: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society (Oskoui et al., 2019) recommends both preventive medications and nonopioid analgesics as first-line management in children. However, the guideline also notes that treatment strategies will depend on the exact diagnosis as well as patient characteristics. The pediatric guidelines for migraine state, “There is no evidence to support the use of opioids in children with migraine” (Oskoui et al., 2019, p. 10).

A Canadian primary care group adapted six high-quality guidelines published through 2011 to develop a CPG for the management of adult headaches, Primary Care Management of Headache in Adults, Clinical Practice Guideline, September 2016, 2nd Edition (see Becker et al., 2015). In that guideline, opioids are listed as a fourth-line treatment for migraines.

Patient Populations

The 2019 AHS position statement notes that “the severity, frequency, and characteristics of migraine vary among persons and, often, within individuals over time, and symptom profiles or biomarkers that predict efficacy and side effects for individuals have not yet been identified” (p. 2). The statement goes on to say that treatment plans need to be individualized based on the patient’s preferences and health status, the course of the patient’s migraine episodes (e.g., presence, type, and severity of associated symptoms and attack-related disability), contraindications (e.g., cardiovascular disease), and the use of concomitant medications (AHS, 2019). The position statement also encourages clinicians to pay specific attention to women who may be or wish to become pregnant, as preventive medications may be teratogenic.

Nonopioid Pain Management Strategies

Silberstein (2000) and the AHS (2019) conclude that prevention is critical to migraine management and that both pharmacological and nonpharmacological methods may be effective in preventing migraines. Silberstein (2000) states that nonpharmacologic treatment may be used prior to or during a migraine. Nonpharmacologic treatments include behavioral treatments, categorized as relaxation, biofeedback therapy, and cognitive–behavioral training, and physical treatments such as acupuncture, cervical manipulation, and mobilization. The AHS (2019) recommends the use of NSAIDs or nonopioid analgesics and an acetaminophen and caffeinated analgesic combination for adult patients with mild to moderate migraine episodes and recommends triptans or dihydroergotamine for moderate to severe episodes. For pediatric migraine, the AHS (2019) recommends the use of nonopioid analgesics, such as ibuprofen, as an initial treatment option. The AHS emphasizes the importance of preventive pharmacologic therapies including triptans, but notes that they are underused, are not always effective and may have side effects. The AHS (2019) notes that only 3–13% of patients with migraine use preventive treatments and estimates that approximately 40% of patients with episodic migraine and almost all of those with chronic migraine could benefit from preventive treatment.

Opioid Prescribing Strategies

Overall, there is little evidence about the best opioid prescribing strategies other than that opioid use should be avoided when possible. A gap in the literature needed for CPG development is an indication of which prescribing strategies minimize adverse outcomes if and when opioids are used. Silberstein (2000) grades the pharmacologic treatments for acute migraine as follows:

- butorphanol nasal spray (Grade A quality evidence, strong scientific and clinical effect, frequent adverse effects; consensus role: moderate to severe migraine; rescue therapy, limit use); and

- oral combinations of acetaminophen and codeine (Grade A quality evidence, less strong scientific and clinical effect, occasional adverse effects; consensus role: moderate to severe migraine; rescue therapy, limit use).

The recommended adult prescribing strategies in Silberstein (2000) include the following:

- Butorphanol nasal spray is a treatment option for some patients with migraine (Grade A); and

- Butorphanol may be considered when other medications cannot be used or as a rescue medication when significant sedation would not jeopardize the patient (Grade C).

The AHS (2019) specifically indicates that while there is established evidence that the opioid butorphanol is effective for migraine, it is not recommended for use (p. 10); there is no citation to explain the reason for this recommendation. Codeine/acetaminophen and tramadol/acetaminophen combinations are listed as probably effective for migraines with auras; specific references for the ratings are not given. Marmura et al. (2015) reviewed studies of tramadol alone and of tramadol in combination with acetaminophen and found both to be effective in reducing migraine pain, but not eliminating pain. Pringsheim et al. (2016) stated that in migraine patients for whom initial treatments for acute pain relief have failed,

opioids or acetaminophen in combination with codeine or tramadol can be considered, provided they are used infrequently. While butorphanol nasal spray has received a Level A recommendation, and codeine/acetaminophen and tramadol/acetaminophen have received Level B recommendations in the AHS acute treatment guidelines, these medications are not recommended for routine use because of concerns about dependence, addiction, and the development of medication overuse headache. (p. 1198)

According to the AHS (2019), for acute pediatric migraine treatment there is evidence to support the efficacy of ibuprofen and acetaminophen for children and adolescents and of triptans primarily for adolescents. Additional recommendations focus on early treatment for acute migraine episodes and counseling on lifestyle factors that can exacerbate migraine, including avoiding triggers and medication overuse.

Intermediate Outcomes

Intermediate outcomes were not addressed in either Silberstein (2000) or the AHS (2019).

Health Outcomes

All of the studies included in Silberstein (2000) or the AHS (2019) focused on pain relief and in some cases on adverse effects from the use of opioids such as butorphanol. No other health outcomes or harms were reported.

Data Gaps and Research Needs

There is a paucity of information on the long-term health outcomes associated with the prescribing of opioids for migraine headaches. Lipton et al. (2019) recently examined unmet treatment needs of acute migraine patients using oral medications, including opioids, and found that 96% of respondents to the Migraine in American Symptoms and Treatment survey had one or more unmet treatment needs, such as inadequate freedom of pain after 2 hours (48%), recurrence within 24 hours of initial relief (38%), or delay of treatment secondary to fear of side effects (21%). Among those reporting unmet needs, 8.1% had opioid or barbiturate overuse (defined as use during 10 or more days per month). This suggests the need for further evaluation of opioid misuse and of opioid’s lack of effectiveness for migraines.

The AHS position paper (2019) stated that symptom profiles or biomarkers that predict efficacy and side effects for individuals have not yet been identified (AHS, 2019). The committee concludes that such research would be helpful in refining and individualizing the use of opioids and nonpharmacologic treatments for migraines.

Low Back Pain