Summary

Opioids have long been prescribed to relieve pain. Acute pain can often be treated and relieved by nonopioid and nonpharmacologic approaches. However, when acute pain is severe or does not respond to other treatments, opioids can provide effective relief.

In the United States opioid prescribing increased steadily from 1999 to 2010, but has decreased modestly since 2012. In spite of the decrease in opioid prescribing, the number of deaths from opioid overdoses, which began to increase noticeably in 1999, has continued to rise, resulting in the ongoing opioid overdose epidemic.

In 2017, 17% of the U.S. population received at least one opioid prescription. To put U.S. prescribing practices for acute pain into context, U.S. dentists prescribe opioids at rates 371 times greater than dentists in the United Kingdom, and U.S. patients undergoing minor surgeries are prescribed opioids 76% of the time compared with 11% of the time in Sweden.

Opioids pose risks not only to patients for whom they are prescribed, but also to family members and the community. Between 6% and 14% of opioid-naïve patients receiving an opioid prescription for pain in the emergency department (ED) or postoperatively continue to use opioids 6–12 months after the initial prescription, and a large number of pills being supplied in the initial prescription is associated with a higher rate of prolonged or high-risk use. However, between 41% and 72% of patients do not use all of the opioids they are prescribed postoperatively. These unused opioids can be misused by the patient and others, particularly family members. There is an association between opioid prescriptions to patients and opioid overdose among family members, particularly among children and adolescents. Finally, most heroin users report misusing prescription opioids prior to initiating heroin use.

The opioid overdose epidemic combined with the need to reduce the burden of acute pain poses a public health challenge. To address how evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for prescribing opioids for acute pain might help meet this challenge, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) to establish a committee to conduct the tasks given in Box S-1.

___________________

1 This text has been revised since prepublication release.

COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

To accomplish FDA’s tasks, the National Academies empaneled a committee of 15 experts who had experience in the development and use of CPGs. The committee recognized that the audience for its report would include not only FDA and other governmental agencies at the federal, state, and local levels, but also professional societies, health care organizations, and health insurers who have developed or may develop guidelines for opioid prescribing. Finally, the committee recognized that individual health care providers, as well as patients, their caregivers, and their communities, all have an interest in optimal prescribing of opioids, not only to manage the patients’ acute pain, but also to prevent opioids from harming them and others. At the request of FDA, the committee focused on opioid prescribing in outpatient settings or at discharge following inpatient care.

The committee held five meetings, three of which included public sessions. At the first meeting, the committee heard from several FDA representatives, a representative of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the general public. At the two following public sessions, subject matter experts presented their views on what surgical procedures and medical conditions are associated with acute pain for which opioid analgesics are prescribed as well as on priorities for a research agenda on medical conditions and surgical procedures (collectively called “indications”) for which no clinical guidelines exist or for which more evidence is required to support existing guidelines.

The committee also conducted literature searches to identify current opioid prescribing practices and trends, existing opioid prescribing guidance, the use of opioids to treat acute pain for selected medical and surgical indications, information on the prevalence and incidence of those selected indications, and standards for CPGs.

MANAGING ACUTE PAIN

The committee’s definition of “acute pain” was derived from multiple authoritative sources (e.g., CDC, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ National Pain Strategy, the ACTTION–APS–AAPM Pain Taxonomy Classification of Acute Pain Conditions, and the Institute of Medicine2). Acute pain is often characterized as not being chronic pain; the latter is almost always considered to be pain that lasts 3 months or longer. Pain that lasts longer than 30 days but less than 90 days is often referred to as subacute pain and represents a transition between acute and chronic pain. The committee determined that for this report, acute pain was the sudden onset of pain that lasts no longer than 90 days.

Acute pain causes physical and emotional distress, affecting a person’s quality of life, sleep, physical functioning, mental health, and ability to meet family, job, school, and other responsibilities. Suboptimal pain management can increase morbidity, slow recovery, prolong analgesic use during and after hospitalization, and increase the cost of care.

Acute pain is common in a number of health care settings. In primary care, back, neck, and joint pain, musculoskeletal injury, and headache are among the most common patient complaints. In EDs the principal reason for more than 20% of visits is some form of pain. Among patients who undergo surgery, approximately 80% report postsurgical pain, and 88% of those patients experience moderate to extreme pain.

Numerous patient, population, and clinician factors influence the presentation and treatment of acute pain as well as a clinician’s decision whether to prescribe opioids. These factors include the patient’s age, sex, and health literacy as well as the presence or absence of comorbidities. There are various health disparities associated with opioid prescribing for acute pain; people of color may be less likely to have access to or be prescribed opioids for their pain. Genetic variations in how people metabolize opioids may also affect their response to treatment.

THE USE AND DEVELOPMENT OF CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES

Current Availability of Clinical Practice Guidelines

Numerous organizations, ranging from professional societies, federal agencies, and state and local governments to individual health care organizations and departments, have implemented some form

___________________

2 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM name is used to refer to publications issued prior to July 2015.

of opioid prescribing guidelines. For example, opioid prescribing guidelines have been promulgated by the American Academy of Emergency Medicine and the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM). All 50 states and the District of Columbia have some form of opioid prescribing guidelines, which can range from advisory guidelines to legally binding limits on opioid prescribing. Some municipalities, such as New York City and Philadelphia, also have recommendations for opioid prescribing in EDs. Guidelines vary from a short list of prescription recommendations for number and dose of opioids to evidence-based CPGs developed by professional societies (e.g., Society for Pediatric Anesthesia) and federal agencies (e.g., the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain). Some states mandate that prescription drug monitoring programs be used by providers to access a patient’s history of prescription opioids and require that prescribers complete some form of mandatory education.

Trustworthy guidelines help clinicians translate current research in basic science and diagnostic and therapeutic interventions into clinical practice, with the goal of improving patient health and societal outcomes. CPGs provide clinicians with recommendations for treatment based on the best available, up-to-date evidence. CPGs may also address treatments for specific subpopulations, such as patients with physical or mental comorbidities, children or the elderly, patients who are currently are taking opioids for a chronic condition, and patients with a substance use disorder.

Despite the recognized merits of CPGs, they also have limitations, including a lack of evidence on which to develop prescribing recommendations; a lack of evidence to inform individualization of therapy based on patient, setting, clinician, and other factors; and slow uptake by clinicians and policy makers. CPGs may be misinterpreted or result in unintended consequences. For example, the 2016 CDC guideline on opioids for chronic pain was inappropriately used to support policies by other organizations for mandatory opioid tapering when the guideline specifically stated that this was not its purpose. Finally, new evidence can make CPGs outdated.

As described in the 2011 IOM report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, standardized, transparent methodologies are more likely to produce trustworthy, evidence-based, and accepted CPGs. Several organizations, including the IOM, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group, the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation Collaborative, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Defense, and the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, have published methodologies for establishing rigorous approaches to the development of guidelines. Many medical and health care professional societies also have standardized methods for producing CPGs, such as the American Academy of Family Physicians, the Council of Medical Specialty Societies, and ACOEM.

Frameworks for Clinical Practice Guidelines

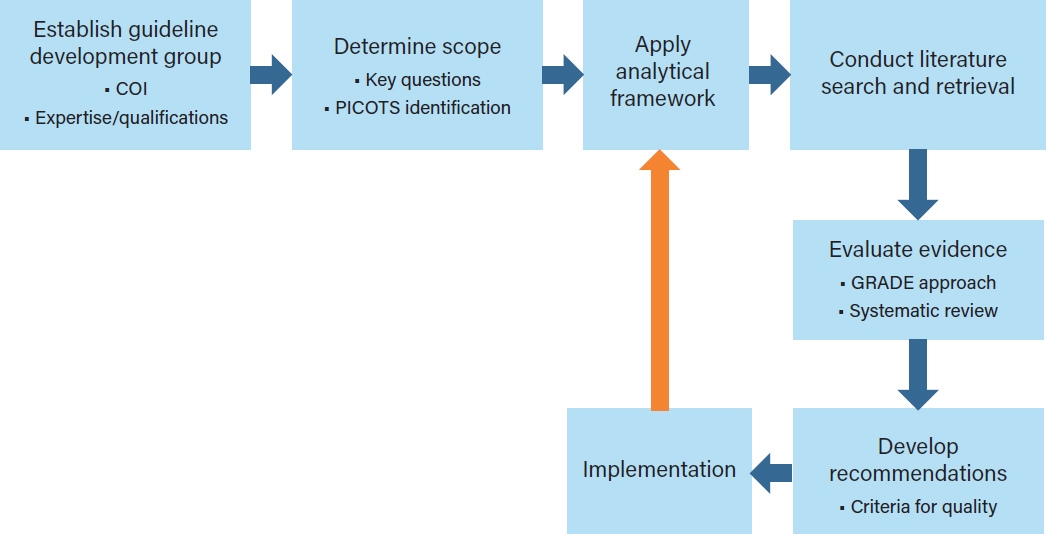

The development of CPGs is based on three core principles: (1) guidelines should be based on evidence that evaluates the efficacy or effectiveness of interventions on health outcomes; (2) guidelines should use the highest-quality evidence available; and (3) guidelines by their nature are developed for application to populations of patients, but should allow for individualization of care to the extent possible. High-quality CPGs are based on a guideline development process that begins with identifying the need for recommendations for a specific surgical or medical indication and proceeds through the selection of guideline developers, gathering and evaluating the scientific evidence, approving the guideline, disseminating the guideline, monitoring its use, and, finally, revising it in a continuous quality improvement context. The committee’s CPG development approach provides a stepped process (see Figure S-1) for assessing the available evidence on opioid prescribing for acute pain indications,

NOTE: COI=conflict of interest; GRADE=Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation;

PICOTS=patient, problem, or population; intervention; comparison, control, or comparator; outcome; time; and setting.

identifying research needs, and facilitating the incorporation of new knowledge into clinical practice as it becomes available.

Establishing a Guideline Development Group

A guideline development group that includes experts and representatives of key stakeholders and health care providers as well as methodologists, epidemiologists, and statisticians will strengthen the rigor and applicability of evidence-based CPGs. Diversity among the guideline developers with regard to expertise, experience, and geographic location is desirable, and the incorporation of the patient perspective will help support the goal of patient-centered care.

Reducing the susceptibility of guideline development groups to conflicts of interest through the use of established, detailed procedures for assessing and managing both financial and non-financial conflicts is essential. Once potential group members have been identified, any conflicts of interest may be posted publicly to enhance transparency.

Scoping the Guideline

The first task of the CPG development group is to delineate which surgical or medical indications the CPG will cover via the statement of scope and setting (e.g., interventions to be assessed and patient populations). The statement is based on a clear description of the patient, problem, or population (P);

intervention (I); comparison, control, or comparator (C); outcome (O); time (T); and setting (S)—the PICOTS process. The PICOTS process helps to define the scope of the guideline, develop the key questions to be addressed by the systematic literature reviews, identify the relevant literature, and inform the evidence evaluation process. Health equity issues for various populations and indications may also be considered in the statement of scope.

Analytic Framework

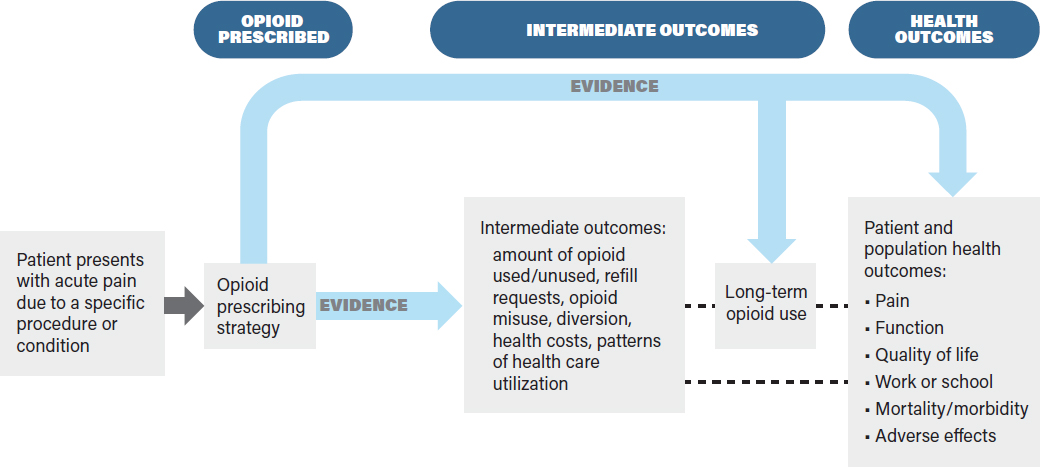

The analytic framework recommended by the committee in Figure S-2 identifies the evidence linkages to be evaluated in a systematic review of the effects of an intervention on health outcomes. The analytic framework visually depicts the evidence and potential data gaps that need to be assessed to make a recommendation on opioid prescribing in order to achieve the best possible health outcomes (see rightmost box of Figure S-2), the intermediate outcomes that are associated with those health outcomes, and the linkages between intermediate and health outcomes. The analytic framework indicates the key questions to be answered by the evidence, typically using a PICOTS approach. Examples of key questions include in patients with acute pain requiring opioid therapy, what is the comparative effectiveness of different opioid prescribing strategies on intermediate outcomes (e.g., refill requests, unused pills, misuse, or diversion)? And in patients with acute pain, what is the association between decreased opioid use and health outcomes?

Defining the outcomes and showing the evidence linkages provides a structured framework by which CPG developers can assess the benefits and drawbacks of different opioid prescribing strategies. The framework is based on the principles that interventions should improve health outcomes, not just intermediate outcomes, and that evaluations of interventions should be based on assessments of both benefits and harms. The patient populations to be studied for a given prescribing strategy are defined during the scoping progress. Prescribing strategies may be based on the characteristics of the patient population, including the indication for pain (e.g., underlying medical condition or surgical procedure), demographic factors (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity), clinical factors (e.g., the presence of chronic pain, prior opioid use, use of other interventions, substance use history, and mental and physical comorbidities), and practice setting (e.g., primary care, inpatient, ED).

The prescribing strategies in the analytic framework are compared across comparable populations with the same acute pain indication. For example, opioid prescribing strategies may compare the effectiveness of variations in the amount of opioids prescribed (e.g., for 3 or 7 days, or a dose of 20 morphine milligram equivalents [MMEs]3 versus 40 MMEs) for a particular indication (e.g., low back pain) or population (e.g., children or the elderly). The prescribing strategies can take into account the specific opioid used, dosing frequency, mechanism of action, mode of delivery, and other factors.

Intermediate outcomes for opioid prescribing strategies at the patient and health care system levels include markers such as the amount of opioids used and unused and refill requests. Individuals who use greater amounts of opioids may increase their risk of adverse health outcomes, such as overdose, and increase the likelihood of long-term use. Long-term use, an intermediate outcome, does not directly measure effects on patient morbidity, mortality, or other health outcomes, but may be associated with these or other long-term adverse health consequences.

A comprehensive assessment of health outcomes takes into account short- and long-term outcomes for the individual patients with acute pain and for the communities or populations to which they belong. Health outcomes to be assessed include pain relief, improved quality of life, improved social and physical function, decreased adverse effects, and increased mortality.

The committee makes the following recommendations regarding the development of a framework to evaluate evidence-based CPGs:

Recommendation: Professional societies; health care organizations; local, regional, and national stakeholders; and other developers of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for opioid prescribing for acute pain should use an analytic framework (e.g., Figure S-2) to develop and assess the evidence base for each CPG. The opioid prescribing strategies, intermediate outcomes, and health outcomes evaluated to develop the CPG should be explicitly described. CPGs should use a well-accepted methodology (e.g., the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation [GRADE] approach) for grading the evidence and rating the strength of the recommendations.

Recommendation: Developers of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for outpatient opioid prescribing for acute pain indications should explicitly state the patient populations to which the CPG is applicable (e.g., adults versus children), and those subpopulations for whom the CPG recommendations may need to be modified such as, for

___________________

3 MMEs are used to standardize reporting of the dose of opioids a person receives across different opioids. For example, 50 MMEs per day is equal to 50 mg of hydrocodone (10 pills of hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/300) or 33 mg of oxycodone (approximately two 15 mg pills of sustained-release oxycodone). See https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf (accessed September 18, 2019).

example, patients with comorbidities, prior opioid exposure, or opioid use disorder. CPG developers should also explicitly define the contextual aspects of prescribing, such as setting, prescriber type, and prior treatments.

Recommendation: Researchers should specify opioid prescribing strategies in a standardized manner, including the drug, strength, amount, and duration of the opioids. Reporting opioid prescriptions as morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) would facilitate evaluation of different opioids based on analgesic potency.

Evidence Evaluation Framework

The evidence evaluation framework is a process by which CPG developers may assess the evidence indicated by the linkages in Figure S-2. Such evaluations can be used to determine the strength of recommendations for an effective opioid prescribing strategy. CPGs consider all types of evidence to assess the linkages between specific opioid prescribing strategies and intermediate and health outcomes in patients with acute pain. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, and quality improvement initiatives may all provide evidence for linkages in the analytic framework. Expert opinion and consensus statements may be included in CPGs, but are usually considered the weakest form of evidence.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are methods to summarize and synthesize a body of literature that may include RCTs or observational studies or both. The use of systematic review methods reduces bias in how studies are selected and analyzed.

Although several organizations have developed formal methods to evaluate the evidence base for clinical questions, the committee found GRADE to be the most useful. This standardized and systematic approach grades the quality of evidence (indicating certainty in findings) and rates the strength of recommendations based on that evidence. GRADE rates the quality of the body of evidence using the following criteria: risk of bias, publication bias, imprecision (random error), inconsistency, indirectness, rating up the quality of evidence, and resource use. In the GRADE approach, study limitations that decrease confidence in the findings include a lack of allocation concealment, a lack of blinding, incomplete accounting of patients and outcome events, selective outcome reporting bias, stopping early for benefit, use of invalidated outcome measures (e.g., patient-reported outcomes), carryover effects in crossover trials, and recruitment bias in cluster-randomized trials.

Evaluating and reporting the strength of evidence is critical for developing CPGs, so that readers can determine how confident they should be in the recommendations. GRADE methodology also addresses factors such as the magnitude of benefits relative to harms, costs, values and preferences, feasibility and implementability, and equity. CPG developers can evaluate the evidence for each of the linkages in the analytic framework using the GRADE criteria and evaluate whether a prescribing strategy is associated with benefits (e.g., decreased overdoses) that outweigh the harms (e.g., a slight increase in average pain). Assessing the balance of benefits to harms requires a consideration of how health outcomes have been prioritized during the earlier scoping step. If the evidence does not support the linkages from a prescribing strategy to an improved health outcome (directly or indirectly), then the CPG developers may opt to either not make a recommendation or make a recommendation but be very explicit about the low quality of the supporting evidence. When the evidence for a linkage is weak but there is little risk of harm and a high likelihood of benefit, a strong recommendation could be formulated based on weak evidence. Such a recommendation may be appropriate to reduce the likelihood of serious harms when there is evidence

of little impact on effectiveness; this has been done in the acute pain context to avoid adverse effects of opioids when there is evidence that opioids are not superior to nonopioid pharmaceuticals.

Recommendation: Researchers who conduct studies to determine optimal opioid prescribing strategies for acute pain should examine not only the intermediate outcomes (e.g., pills prescribed and unused and long-term opioid use), but also the short- and long-term health outcomes (e.g., mortality, overdose, opioid use disorder, pain, and function) at both the patient and population levels.

Recommendation: Researchers studying opioid prescribing for acute pain should address evidence gaps by linking opioid prescribing strategies to health outcomes using appropriate study designs. Well-designed observational and quality improvement initiatives are helpful for evaluating the effects of opioid prescribing strategies on health outcomes.

Implementation

After recommendations for opioid prescribing strategies have been developed and approved, consideration needs to be given to ensuring the effective dissemination, uptake, impact, and periodic revisions of the CPG, all of which are activities that are part of implementation. Many organizations that develop CPGs already have mechanisms in place to disseminate them to appropriate audiences. For example, members of a medical specialty society may learn about a new or changes to an existing CPG at annual or regional meetings, at continuing medical education activities, or from educational materials from state medical boards. Implementation also addresses how CPGs relate to different clinical practice and clinical settings, how to increase the applicability and impact of guidelines, and how to evaluate the impact of the guideline on health outcomes. A critical aspect of CPG implementation is the need for continuous quality improvement, including audit and feedback. As each CPG is disseminated and applied in clinical practice, outcome data need to be gathered at the patient and community levels to ensure the appropriate uptake and evaluation of the intended and possible unintended effects. Such information can assist guideline developers in revising and updating the CPG when necessary so that it reflects the most current evidence available to ensure that patients with acute pain receive the best care.

Recommendation: Organizations that develop evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) on opioid prescribing for acute pain, including governmental entities (federal, state, and local) and nongovernmental entities, such as professional societies, health care organizations and collaboratives, and health insurers, should establish a process for disseminating, implementing, and monitoring the uptake and impacts of the CPG on opioid prescribing practices. These impacts include short- and long-term patient and population-level intermediate and health outcomes, particularly opioid misuse, opioid use disorder, and opioid overdoses and deaths.

PRIORITIZING SURGICAL AND MEDICAL INDICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT

The National Academies committee was tasked with identifying and prioritizing up to 50 specific surgical procedures and medical conditions that are associated with acute pain and for which opioid analgesics are commonly prescribed and considered clinically necessary. The committee was also tasked

with recommending where evidence-based CPGs would have the greatest impact on public health. The committee determined that a priority indication would meet three criteria: the prevalence of the surgical or medical indication was high; there was evidence of variation in opioid prescribing in relation to patient-centered or patient-reported outcomes; and an evidence-based CPG or other guidance on opioid prescribing for acute pain associated with the indication was available for review.

The committee began developing its list of priority surgical and medical indications by conducting literature searches to identify the most prevalent indications associated with acute pain and opioid prescribing. The committee also identified specific indications associated with acute pain for which some type of guidelines have been published or for which CPGs would be helpful but no guidelines currently exist according to literature searches, input from experts at its public sessions, and the committee’s expertise. There were few guidelines that were specific for (1) opioids, (2) acute pain, and (3) a specific indication, but there are several guidelines that met at least two of those criteria.

Given the heterogeneity of the potential indications for acute pain, the committee did not create a standardized algorithm for prioritizing the creation of CPGs for opioid prescribing for acute pain. The committee considered that there are many acute pain conditions for which CPGs may be appropriate and that stakeholders might vary in how they prioritize these and other conditions depending on a number of factors such as emerging science or great variability in opioid prescribing.

The committee deemed the surgical and medical indications in Table S-1 to be priorities for the development of evidence-based CPGs or, if a guideline was already available, as a candidate for modifying the guideline or strengthening the evidence base to meet the standards in the committee’s analytic framework.

Recommendation: Professional societies, health insurers, and health care organizations should consider the prioritized surgical and medical indications listed in Table S-1 for evidence-based clinical practice guideline (CPG) development or, where a CPG already exists, for modification to meet the analytic and evidence frameworks in this report. The committee acknowledges that other surgical and medical indications may emerge as priorities as the evidence base grows.

EVALUATING SELECTED CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES

The committee evaluated seven existing opioid prescribing guidelines for acute pain for selected indications against its analytic framework. It chose three surgical procedures and four medical conditions that have public health impacts, for which there were some type of available guidelines and some evidence regarding opioid prescribing, and that were different in scope and context. The three surgical procedures—cesarean and vaginal delivery, third molar extractions, and total knee replacement—and the four medical conditions—renal stones, migraine headaches, low back pain, and sickle cell disease—vary with regard to the affected populations, such as children, adolescents, adults, older populations, women of reproductive age, and minority populations. Evaluating the guidance chosen for each indication allowed the committee to identify data needs and research gaps for prescribing opioids for each indication.

The committee recognized that its task was predicated on the determination that opioids would be prescribed for acute pain for a given indication. In its review of the available guidance, the committee determined that many CPGs consider the use of opioids for pain control in the context of a broader multimodal approach to pain management (e.g., the CPG for low back pain developed by the American Pain Society) and that opioids are often not a recommended first-line treatment. In clinical practice the decision to use opioids for acute pain is often made in the context of a comprehensive treatment

TABLE S-1 Priority Indications for Acute Pain for Clinical Practice Guideline Development or Modification (listed alphabetically)

| Surgical Indications | Medical Indications |

|---|---|

| Anorectal, pelvic floor, and urogynecologic (e.g., colon resection, hemorrhoidectomy, vaginal hysterectomy) | Dental pain (nonsurgical) |

| Breast procedures (e.g., lumpectomy, mastectomy, reconstruction, reduction) | Fractures |

| Dental surgeries (e.g., third molar extraction) | Low back pain (includes lumbago, dorsalgia, backache) |

| Extremity trauma requiring surgery (e.g., amputation, open reduction and internal fixation) | Migraine headache |

| Joint replacement (e.g., total hip arthroplasty, total knee arthroplasty) | Renal stones (also called kidney stones, nephrolithiasis, calculus of the kidney, renal colic) |

| Laparoscopic abdominal procedures (e.g., appendectomy, bariatric surgery, cholecystectomy, colectomy, hysterectomy, prostatectomy) | Sickle cell disease |

| Laparoscopic or open abdominal wall procedures (e.g., femoral hernia, incisional hernia, inguinal hernia) | Sprains/strains, musculoskeletal |

| Obstetric surgeries (e.g., cesarean delivery, vaginal delivery) | Tendonitis/bursitis |

| Open abdominal procedures (e.g., appendectomy, cholecystectomy, colectomy, hysterectomy) | |

| Oropharyngeal procedures (e.g., tonsillectomy) | |

| Spine procedures (e.g., fusion in both adults and children, laminectomy) | |

| Sports-related procedures (e.g., anterior cruciate ligament repair and reconstruction, joint arthroscopy, rotator cuff repair) | |

| Thoracic procedures (e.g., thoracoscopy, repair of pectus excavatum in children [Nuss procedure]) | |

plan tailored to an individual patient. Such treatment plans ideally consider the patient’s health status, including pre-existing conditions, comorbidities, prior reactions to opioids or other pharmaceuticals, treatment preferences, and the availability of and access to all treatment modalities. However, it is difficult to determine the most effective opioid prescribing strategy because many studies that evaluate opioid prescribing fail to mention other interventions that may be prescribed by the clinician or used by the patient, including the use of over-the-counter medications and interventions such as acupuncture.

Recommendation: Developers of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for an acute pain indication should address the appropriate use of opioids for the indication as well as the optimal opioid prescribing strategies. CPGs should explicitly state the role of opioid alternatives, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, as first-line therapies and the role and prescribing of opioids in the context of nonopioid pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic alternatives.

Researchers who evaluate opioid prescribing strategies for an acute pain indication should also specify any other interventions, including nonopioid interventions, used to relieve pain in the patient populations to be studied.

A RESEARCH AGENDA FOR OPIOID PRESCRIBING FOR ACUTE PAIN

The committee reviewed many studies that reported on the short- and long-term intermediate effects of reduced opioid prescribing in various health care systems, and several of these studies also reported on health outcomes in terms of patient reports of satisfaction with their care and pain control. However, there is a paucity of studies that examine the effects of opioid prescribing strategies on population-level outcomes such as fewer opioid overdoses seen in the ED, fewer first overdoses in which naloxone rescue therapy is needed, and fewer opioid-related deaths in the community. Although efforts to address the opioid epidemic are the impetus for many of the strategies to reduce inappropriate opioid prescribing, the societal impact of such strategies is not clearly understood and requires further research. While it seems intuitive that reducing opioid prescribing may result in fewer opioid overdoses and deaths, the impact of such reductions on patient pain control and the risk of unintended consequences for patients, their support systems, and their communities cannot be assumed and should be informed by accurate and comprehensive data.

To address these data gaps and support the development of more robust evidence-based CPGs, the committee makes the following recommendations regarding future research:

Recommendation: Researchers studying opioid prescribing for acute pain should assess how nonopioid interventions (pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic, or both) affect the need for opioids for acute pain as well as assessing their effects on the intermediate outcomes and health outcomes of opioid prescribing strategies.

Recommendation: Researchers studying opioid prescribing for acute pain should address the evidence gaps in the following key priority areas:

- outcomes of opioid prescribing strategies in key patient populations;

- the impact of clinical setting on opioid prescribing strategies; and

- the links between intermediate outcomes, such as the number of unused pills or long-term opioid use, and health outcomes, such as pain, mortality, overdose, opioid use disorder, and function.