3

Development and Use of Clinical Practice Guidelines

The 2011 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust defined clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) as “statements that included recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms or alternative care options” (IOM, 2011a, p. 4). Evidence-based practice is the integration of the best research evidence, clinical expertise, and patient values into the decision-making process for patient care (IOM, 2008; Straus et al., 2019). Thus, CPGs are intended to synthesize the available evidence and knowledge in order to create pragmatic tools for clinicians to optimize care for patients with specific medical conditions or undergoing specific surgical procedures. A trustworthy CPG can help clinicians and patients improve their communications and decision making about the risks and benefits of clinical activities, including treatments and diagnostic procedures, and can improve the safety and effectiveness of those treatments and procedures (Dowell et al., 2016). In particular, the consistent use of CPGs can help clinicians reduce inappropriate prescribing of opioids (Bohnert et al., 2018).

CPGs are used in a variety of setting and by a range of clinicians who prescribe opioids as well as by other health care professionals involved in the management of acute pain. Other users of CPGs can include health insurers; regulatory agencies at the federal, state, and local levels; and pharmacy benefits managers aiming to identify and promote best practices in pain management. Finally, CPGs are of value to patients, caregivers, and advocates for setting expectations for recovery and providing education on the safe use of opioid and nonopioid analgesics. CPGs may be used by clinicians in a variety of clinical settings; consistent with its charge, the committee focused on those settings where opioid prescriptions are written, including primary care clinics, emergency departments (EDs), dental clinics, medical specialty clinics, and ambulatory surgical facilities.

Although many guidelines are publicly available, some that have been developed by professional societies may not be widely available. The committee notes that until 2018, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) maintained the National Guidelines Clearinghouse. Created in 1997 by AHRQ in partnership with the American Medical Association and the American Association of Health Plans (now America’s Health Insurance Plans [AHIP]), the publicly available website provided physicians, other health care professionals, health care systems, and others with objective, detailed

information on CPGs to promote their dissemination, implementation, and use (AHRQ, 2018). With the defunding of the clearinghouse in 2018, the guidelines it contained are no longer publicly available through AHRQ, although some of them may be available from the original source. As of October 2019, AHRQ stated that it is conducting a study to identify new models for disseminating and accessing CPGs. In this report, the committee focused on CPGs that are publicly available.

PRINCIPLES OF CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT

The development of trustworthy and useful evidence-based CPGs requires a standardized process. As discussed in the 2011 IOM report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, transparent and consistent processes can increase the trust in, uptake of, and adherence to a CPG. Many health care organizations not only have created CPGs, but also have established protocols or manuals for the development of CPGs within their specialty areas. Among the organizations that have created such guideline development manuals are the American Academy of Audiology, the American Physical Therapy Association, and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies (CMSS).

Clinical Practice Guideline Development Criteria

High-quality guidelines follow the best-practice guideline development criteria established by the IOM (2011a). The criteria for such guidelines include

- a complete description of development, sponsorship, and funding processes that are transparent and accessible;

- a transparent process that acknowledges and minimizes the potential for bias and conflicts of interest;

- input from stakeholders and experts across multiple disciplines, including representatives of patients who will be affected by the guideline;

- a rigorous systematic review of the current evidence and an assessment of the quality, quantity, and consistency of this evidence;

- a summary of the evidence and gaps in knowledge regarding the potential benefits and harms relevant to each recommendation;

- a disclosure of recommendations that are based on values, opinions, theories, and clinical experiences and a rating of the strength of each recommendation is included based on the available evidence and panel consensus;

- an external peer and public review and public comment process;

- a mechanism for revision when new evidence becomes available; and

- a process for guideline adoption, dissemination, and implementation.

The systematic reviews on which CPGs are based also need to be conducted in a standardized manner to ensure that the evidence accurately supports any recommendations based on that evidence (IOM, 2011a). Several organizations have developed methodologies for systematic reviews, including IOM (2011b), Cochrane (Higgins et al., 2019), and AHRQ (2018b). The IOM (2011b) recommended four broad standards for synthesizing the body of evidence:

- Use a prespecified method to evaluate the body of evidence;

- Conduct a qualitative synthesis;

- Decide if, in addition to a qualitative analysis, the systematic review will include a quantitative analysis (meta-analysis); and

- If conducting a meta-analysis, use expert methodologists, address heterogeneity among study effects, include measures of statistical uncertainty with all estimates, and conduct sensitivity analyses.

Strengths and Limitations of Clinical Practice Guidelines

Trustworthy CPGs provide clinicians, policy makers, and other stakeholders with tools to guide evidence-based practice decisions for the care of patients in specified clinical circumstances. The purpose of guidelines is to help clinicians translate current research in basic science and diagnostic and therapeutic interventions into clinical practice in order to improve the clinical outcomes (Linda et al., 2013; Murad, 2017). The volume of research on opioids for a number of surgical and medical indications is growing daily, and it is difficult, if not impossible, for clinicians to stay informed on and synthesize all of the latest literature into their practice. CPGs provide clinicians with recommendations on opioid prescribing for acute pain based on the latest and best available evidence in order to improve short- and long-term health outcomes, reduce the number of unused pills, reduce the need for refills, and inform the appropriate use of nonopioid medications and nonpharmacologic therapies. Another strength of CPGs is that they can provide treatment recommendations for specific subpopulations, such as patients with physical or mental health comorbidities, children or the elderly, patients who are currently taking opioids for a chronic condition, and patients with substance use or opioid use disorder.

Despite the recognized merits of CPGs, they do have limitations. First, CPGs are often limited in the extent to which they address the individualization of therapy based on patient, setting, clinician, and other factors, frequently because of a lack of evidence. Second, the impact of CPGs may be limited due to low uptake by clinicians and policy makers. Third, the implementation of CPGs may result in unintended consequences. For example, the 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guideline on opioid use for chronic pain has been applied to patients with active cancer pain and has been used to support policies for mandatory opioid tapering—even though the guideline explicitly states that it is not intended for patients with active cancer pain and does not recommend tapering in all patients (Dowell et al., 2019; Kroenke et al., 2019). Finally, the publication of new evidence can make CPGs outdated, particularly for recommendations supported by low-quality evidence (Shekelle, 2014).

Several strategies are used by CPG developers to address these challenges. To facilitate greater individualization of therapy, CPGs can explicitly consider patient, setting, clinician, and other factors that affect response to therapy, to the extent possible. When evidence is lacking with which to guide individualization of therapy for certain subgroups (e.g., patients with history of opioid use disorder), CPGs can acknowledge the evidence gaps and indicate situations in which deviation from recommendations may be warranted.

Scope of Clinical Practice Guidelines

CPGs differ in scope. Some are broad in scope and describe how to prescribe opioids for a general medical indication; these include the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine’s (ACOEM’s) ACOEM Practice Guidelines: Opioids for Treatment of Acute, Subacute, Chronic and Postoperative Pain (ACOEM, 2014), the joint American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine’s 2009 Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy for Chronic Noncancer Pain, and the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. Other CPGs may be relatively

narrow in focus and provide recommendations for the treatment of a specific population or surgical or medical indication, such as the Consensus Statement for the Prevention and Management of Pain in the Newborn (Anand and the Internal Evidence-Based Group on Neonatal Pain, 2001). The variation in scope may be the result of differing missions and goals among the authoring organizations as they seek to address the needs of their members, patient populations, and clinical specialties; resource constraints; and the availability of scientific evidence.

Guidelines that are intended to help clinicians manage acute pain may also include recommendations for chronic pain, general pain, or pain resulting from specific causes, such as surgery, dental treatments, or cancer. Furthermore, not all guidelines for pain management are specific to opioid prescribing, and some may address other treatments such as nonopioid pharmacotherapeutics (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], gabapentinoids, and steroid injections) and nonpharmacologic therapies (e.g., physical therapy, heat, acupuncture, and chiropractic care).

METHODOLOGIES FOR DEVELOPING CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES

Numerous organizations have proposed standardized, transparent methodologies for CPG development with the aim of producing more trustworthy and accepted documents. Several organizations, including the IOM; the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Collaborative; the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD); and the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, have published methodologies for establishing rigorous approaches to the development of guidelines. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group is a resource for quality assessment of evidence and guidelines. Many medical and other health care professional societies also have standardized methods for producing CPGs. In some cases, the description of methods for developing the guidelines is brief and details regarding the criteria used to grade or rate the scientific strength of studies may be lacking (e.g., American Academy of Audiology, 2006), whereas others are based primarily on the precepts advanced by the IOM, GRADE, or other organizations (e.g., American Academy of Family Physicians, 2017). Organizations such as CMSS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation, and the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines oversee and direct the CPG development processes and have standardized methodologies to do so. The World Health Organization (WHO) provides a handbook on guideline development that incorporates GRADE for evaluating the quality of evidence.

The committee briefly summarizes these various methodologies below.

Institute of Medicine

Building on work done by the IOM in the early 1990s (IOM, 1990, 1992, 1995), in 2010 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services asked the IOM to further examine what might be done to improve the impact that CPGs have on clinical practice and also to examine the research on which they are based. The resulting 2011 IOM report, Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, laid out a number of criteria that, if addressed, would be expected to produce high-quality and trustworthy CPGs that could help enhance the translation of research, particularly randomized controlled trials, into better clinical decisions and ultimately improve patient care. The IOM report recommended eight standards for developing CPGs (see section on Clinical Practice Guideline Development Criteria). Thus, the IOM report addresses composition of the guideline development group, management of conflicts of interest,

decision-making processes, evidence synthesis, and reporting of recommendations, among other important aspects of GPG development.

The IOM committee acknowledged that even the most trustworthy and scientifically valid CPG must be used at the clinician level to be effective. To that end, the report recommended that CPGs should be structured “to facilitate ready implementation of computer-aided CDS [clinical decision support] by end-users” (p. 13). The IOM further stated that transparency in how the methods were actually applied and in the choices made is critical for developing high-quality systematic reviews of comparative effectiveness research.

In a 2011 companion report, Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews, the IOM described the advantages of a systematic review versus a narrative review (IOM, 2011b). Systematic reviews use a predetermined set of criteria that are intended to reduce bias in the identification, selection, assessment, and synthesis of information from similar but separate studies. Systematic reviews may be either qualitative or quantitative; a systematic review may also include a meta-analysis, that is, a statistical analysis of the data from several studies. A meta-analysis may inform clinical decision making for a CPG (IOM, 2011b), help estimate the statistical heterogeneity among studies, and highlight factors that affect different estimates of the harms and benefits of a particular clinical practice (Chou, 2008). The IOM proposed 21 standards with 82 elements across the systematic review process, from formulating the topic to developing a final systematic review report.

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

The GRADE Working Group, based at McMaster University in Canada, developed the GRADE approach to rating the quality of evidence that supports the development of CPGs and grading the strength of recommendations based on that evidence (Siemieniuk and Guyatt, 2019). This approach is widely used by health care organizations, ranging from CDC to professional societies. The integral aspects of the GRADE approach are the production of evidence profiles, systematic reviews, a summary of findings tables, and graded recommendations using a GRADEpro computer program. Beginning in 2011, the GRADE Working Group has published numerous articles that detail the methodology of the approach so that guideline developers may use it to produce high-quality CPGs. The articles cover how to rate the quality of evidence in terms of bias, precision, consistency, directness; how to summarize the evidence for individual, binary, and continuous outcomes; how to apply GRADE to diagnostic tests; how to move from evidence to recommendations; and the challenges of using observational studies (Guyatt et al., 2011).

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

The USPSTF is a volunteer panel of 16 experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine who convene to systematically review evidence to make recommendations about clinical preventive services in asymptomatic persons, such as screening for breast cancer or for abdominal aortic aneurysms (USPSTF, 2018a). The USPSTF guidelines do not provide recommendations for treating populations undergoing surgical procedures or who have medical conditions, although the guidelines may recommend how the preventive services may need to be tailored for such populations. The standards for guideline development closely align with those delineated in the IOM 2011 report (USPSTF, 2018b). The USPSTF published its procedure manual in 2015 to describe its process for selecting topics, reviewing evidence, and arriving at recommendations (USPSTF, 2018a). Some important aspects of the USPTSTF method that distinguishes it from other CPG development methods is the consideration of indirect pathways

and chains of evidence and the use of analytic frameworks, key concepts for this report as discussed in Chapter 4.

To describe the strength of each recommendation and balance the harms and benefits associated with it, the USPSTF developed grade definitions ranging from A (recommends this service and there is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial) to D (recommends against this service and there is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit) (USPSTF, 2018a). When evaluating indirect evidence, observational data, and studies with intermediate endpoints as outcomes, the USPSTF uses the criterion of coherence to assess the certainty of indirect evidence, extrapolation to estimate the magnitude of the net benefit, and conceptual bounding to estimate the theoretical lower or upper limits of the net benefit (Krist et al., 2018). Evidence gaps and special populations are also identified and considered in the evaluation process (Bibbins-Domingo et al., 2017; Kemper et al., 2018; Whitlock et al., 2017). The complete list of USPSTF recommendations is publicly available online.

Other Methodologies

Other organizations have developed methodologies that facilitate CPG development or assessment. These organizations include the AGREE II Collaboration and AHRQ.

AGREE has developed an instrument and user’s manual to “assess the process of guideline development and reporting of this process in the guideline” (Brouwers et al., 2010). The instrument comprises 23 items rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) grouped into six quality-related domains: scope and purpose; stakeholder involvement; rigor of development; clarity of presentation; applicability; and editorial independence.1 Other countries such as Canada, France, and Germany have governmental organizations that develop and disseminate systematic reviews and CPG guidance; international organizations such the Health Technology Assessment International and Cochrane also develop and promote evidence-based assessments.

AHRQ established its Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) program in 1997 to “develop evidence reports and technology assessments on topics relevant to clinical and other health care organization and delivery issues” and the Effective Health Care (EHC) program in 2005 to conduct systematic reviews (AHRQ, 2019). The reviews are performed by 14 EPCs that conduct comparative effectiveness reviews, effectiveness reviews, and technical briefs that are focused on patient-centered outcomes. The AHRQ Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (2008) guides the EHC program’s systematic reviews with the goal of making the health care information accessible to patients, clinicians, and policy makers. The AHRQ guidance contains many standards identified by the IOM reports on systematic reviews and the development of CPGs, including disclosure of competing interests by developers, extensive training for the review team, the use of key questions to guide the review process, and the posting of draft materials at several stages of the development process in order to seek public input. AHRQ also provides guidance on conducting comparative effectiveness reviews on the relative benefits and harms of a range of options, which addresses interventions beyond whether one particular treatment is safe and effective.

___________________

1 All AGREE II information is publicly available from http://www.agreetrust.org, including an online training tool for using the instrument.

EXAMPLES OF OPIOID PRESCRIBING GUIDELINES FOR ACUTE PAIN

There are a vast number of guidelines2 for managing pain, including for the use of opioids for acute and chronic pain, offered by different organizations, ranging from federal government agencies to state legislatures to professional societies and even individual health care institutions. Often, CPGs are issued by clinical professional societies, such as the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and the American Urological Association; however, CPGs have also been issued by federal agencies, such as the VA/DoD VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain (2017). The committee notes that in addition to CPGs on opioid prescribing, there are other types of recommendations for clinicians, including practice guidelines based on consensus rather than evidence; policies and recommendations from health care organizations or departments, consortia of health care organizations, governmental agencies such as CDC, state and local agencies such as state medical boards and municipal health departments, and health insurers; as well as state laws on opioid prescribing. Other organizations have developed documents similarly intended to provide clinical recommendations, such as the 2017 American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons’ white paper Opioid Prescribing: Acute and Postoperative Pain Management, but these documents lack key elements of evidence-based CPGs (see Chapter 4). Several states have also developed guidelines for opioid prescribing, for example, the Minnesota Opioid Prescribing Guidelines, First Edition, 2018, and the Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network’s Opioid Prescribing Recommendations for Opioid-Naïve Patients from 2018. Based on the breadth of CPGs for opioid prescribing, the committee considered these and other types of guidance documents for surgical procedures and medical conditions. The latter may not meet the criteria for a CPG, defined as guidance based on a formal evidence review with rating of the evidence using a prespecified rating scheme. However, the committee uses the term “guidelines” to refer to the entire range of recommendations on opioid prescribing for acute pain.

Selected examples of guidelines developed by a variety of organizations are summarized briefly below.

Federal Government Agencies

Several federal government agencies have produced guidelines and implemented policies to address the opioid epidemic, most notably CDC and VA/DoD. Those guidelines are not indication-specific, but rather aim to address opioid prescribing and pain management for both acute and chronic pain. Examples of those CPGs are summarized below:

- CDC developed and published the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain in 2016 (Dowell et al., 2016). While focused primarily on chronic pain, the guideline also addresses acute pain and recommends that clinicians prescribe a quantity no greater than what is needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids, specifying that 3 days or less will often be sufficient and that more than 7 days will rarely be needed for acute pain indications. The CDC guideline also addresses dose-dependent risks of opioids. This guideline has become the basis for many other stakeholders’ guidelines, including many state prescribing limits (see section on State and Local Governments).

- The 2017 VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain, while focused on opioids for chronic pain, also includes recommendations on their use for acute pain.

___________________

2 Though there are numerous CPGs and other guidelines offered by other countries, including Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, the committee did not review them or consider them for its task, given the different medical systems and prescribing environments.

-

Specifically, the guideline recommends “against prescribing long-acting opioids for acute pain, as an as-needed medication, or on initiation of long-term opioid therapy” (VA/DoD, 2017, p. 8). The recommendations for using opioids to treat acute pain range from strong (use alternatives to opioids for mild to moderate acute pain) to weak (use mulitmodal pain care when using opioids). This VA/DoD CPG is evidence based and follows the VA/DoD Guideline for Guidelines (VA/DoD, 2019). The guideline uses the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the evidence and assign a rating for the strength of each recommendation.

- The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has issued opioid policy guidelines that include safety alerts at pharmacies for initial opioid prescriptions or high doses as well as an adjustment to the default fill of prescription opioids for acute pain for opioid-naïve patients to 7 days for Medicare Part D programs. The policy recommends that states block payment for opioid prescriptions of more than 7 days or more than 90 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) (Brandt, 2019; CMS, 2018) (see section on Health Care Systems and Health Insurers).

Professional Societies

The 2011 IOM report has been used by numerous medical specialty societies and other health care organizations as the basis for creating their own CPG development processes and methodologies, manuals, and guidelines (e.g., APTA, 2018; CMSS, 2017). Medical specialty and professional societies offer an abundance of Web-based patient care guidelines for pain management that focus on opioid prescribing, with many of them publicly available. For example, the American Academy of Emergency Medicine has developed a White Paper Position Statement on the Treatment of Acute Pain in the Emergency Department (Motov et al., 2018) and the American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Acute Pain Management in the Perioperative Setting (ASA, 2012). Some examples of other guidelines developed by medical specialty societies are briefly discussed below (other guidelines for priority surgical and medical indications are presented in Chapter 5, Tables 5-2 and 5-3, respectively):

- In 2016 ACOEM released a guideline statement titled Principles for Ensuring the Safe Management of Pain Medication Prescriptions by Occuptational and Environmental Medicine Physicians (Mueller et al., 2016). It lists selected measures from ACOEM’s Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines to decrease harmful opioid use for chronic noncancer pain as well as one bullet about prescribing for acute pain:

When prescribing opioids for acute pain, physicians should set expectations for discontinuation, and limit quantities of prescriptions to what is clinically needed. In most non-operative cases opioids should be limited to several days, preferably less than a week and not to exceed 2 weeks. (ACOEM, 2011)

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has opioid-related guidance and resources for providers on its website (ACOG, 2019). These range from a webinar titled Maternal Transitions in Care for the Mother–Infant Dyad Affected by Opioid Use Disorder to Guidelines for Perinatal Care, 8th Edition, which was developed jointly with the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2017 and includes a brief guideline regarding prescribing opioids for acute pain. The ACOG Commitee on Obstetric Practice (2018) also released an opinion regarding presribing opioids for postpartum pain management. The ACOG practice bulletins are similar to CPGs, although they are not publicly available; committee opinion documents, however, which also include recommendations but are less rigorous than CPGs, are publicly available.

- In 2018 the American Dental Association (ADA) updated its policy on the use of opioids to treat dental pain and emphasized using nonopioids as the first-line therapy for acute dental pain. ADA supports statutory limits on opioid dosage and a duration of no more than 7 days for acute pain treatment (ADA, 2018). The American Academy of Pediatric Dentristy released a policy statement titled Policy on Acute Pediatric Dental Pain Management in 2017, that offers guidelines for prescribing opioid anelgesics for pediatric patients (AAPD, 2017).

- The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia recently released an evaluation of the available literature on the use of opioids in children during the perioperative period and formulated recommendations. The recommendations were graded based on the strength of the available evidence using the three-tiered classification system developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists. For issues in which evidence was unavailable, expert consensus was used. Recommendations were made concerning opioid administration to children after surgery, including appropriate assessment of pain, as well as the monitoring of patients on opioid therapy, opioid dosing considerations, the side effects of opioid treatment, strategies for opioid delivery, and the assessment of analgesic efficacy (Cravero et al., 2019).

Health Care Systems and Health Insurers

Numerous health systems, large and small, for-profit and not-for-profit, have been involved in the development and implementation of guidelines for prescribing opioids. Health care systems such as Kaiser Permanente, the Mayo Clinic, and Intermountain Healthcare have adopted prescribing guidelines. Two examples are described briefly below:

- The Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association (MHA) and the Tufts Medical Center released a CPG in June 2018 titled Inpatient Opioid Misuse Prevention: A Comprehensive Guide for Patient Management with Regards to Opioid Misuse. MHA’s Substance Use Disorder Prevention and Treatment Task Force also published Guidelines for Prescription Opioid Management within Hospitals and Guidelines for Emergency Department Opioid Management.

- The Mayo Clinic used its patient datasets to develop internal opioid prescribing guidelines for its Department of Orthopedic Surgery in 2017. Three opioid dose levels (low, standard, high) are used depending on the severity of the condition and the surgical procedure. Subsequently Mayo developed its clinical surgical outcomes program recommendations for adult discharge opioid pescriptions for a number of surgical procedures across eight surgical specialties. Clinicians were cautioned, however, that the recommendations—which included recommendations on low, standard, and high dose prescribing for both opioids and nonopioids—did not supersede clinical judgment or department-level guidelines (Elizabeth Habermann, Mayo Clinic, presentation to committee, July 9, 2019).

Other stakeholders, including electronic health record (EHR) companies and health insurers, have also tried to address opioid misuse and overprescribing in response to the opioid epidemic. Studies have shown an association between lower prescription default values for postoperative opioids in EHRs and reduced clinician prescribing practices (Delgado et al., 2018). For example, lowering the EHR default from 30 pills to 12 pills decreased the amount of opioids prescribed by more than 15% across an entire health system (Chiu et al., 2018). The Electronic Health Record Association Opioid Crisis Task Force is examining how to best use EHRs to fight the opioid epidemic. The association published an EHR

implementation guide for the CDC CPG. In response to the CDC CPG, Epic Systems3 set its defaults for opioid prescribing based on the CDC prescription limits (Donovan, 2018). The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufactuters of America, which represents several opioid manufacturers, including Bayer, Pfizer, and Merck, announced its support for limiting the supply of opioids to 7 days for acute pain management (PhRMA, 2017). AHIP, a national association of health insurers, announced its Safe, Transparent Opioid Prescribing initiative “to support widespread adoption of clinical guidelines for pain care and opioid prescribing” (AHIP, 2019). AHIP noted that many of its member health insurers are working with federal and state agencies, doctors, and hospitals to reduce inappropriate opioid prescribing and promote the use of effective, alternative treatments for pain.

State and Local Governments

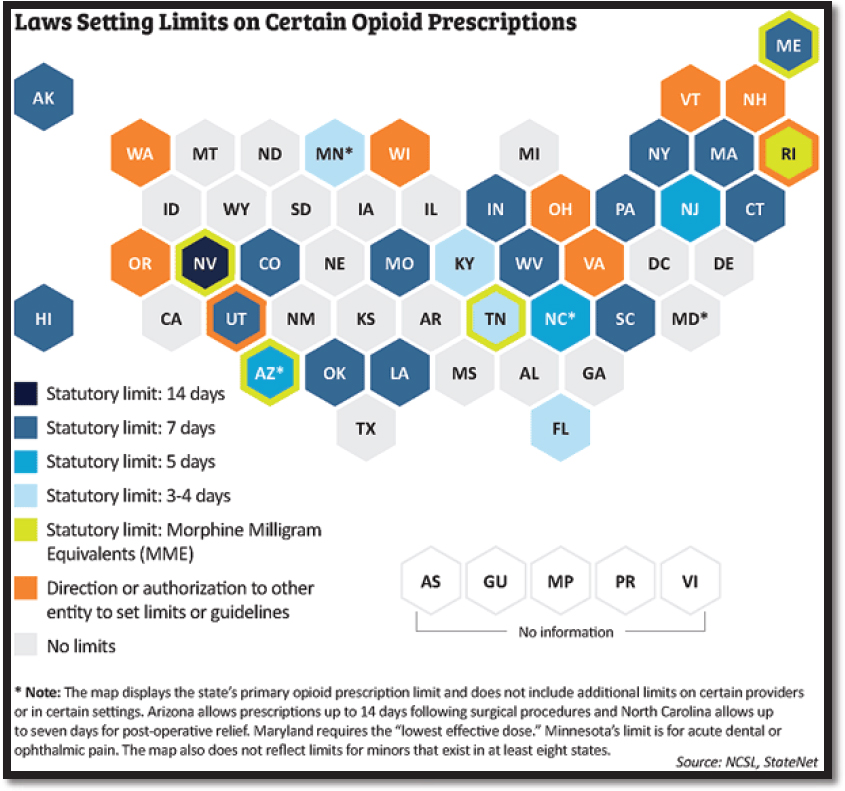

All 50 states as well as the District of Columbia have some form of opioid prescribing guidelines, which can range from advisory guidelines to legally binding limits on opioid prescribing.4 In 2016 Massachusetts was the first state to pass a law limiting first-time opioid prescriptions to 7 days. Since then more than half of all states have enacted laws that restrict the prescribing or dispensing of opioids for acute pain (Davis et al., 2019; NCSL, 2018) (see Figure 3-1). Most state restrictions have established a limit on the number of days’ supply of the drug or a daily MME limit or both. For example, Virginia both regulates the number of days for an opioid supply and imposes a dosage limit; that is, the prescription may not be longer than 7 days, or 14 days for a postsurgical procedure, and unless “extenuating circumstances” are documented by the clinician in the patient’s medical records, the dosage cannot exceed 50 MME/day.5 Maryland restricts prescriptions to the “lowest effective dose” but does not specify a day limit (Davis et al., 2019). Many states also set limits specifically for minors (NCSL, 2018).

Some states emphasize the need for medical education concerning the prescription of opioids. For example, Arizona limits the number of days’ supply of opioids and the MME/day. It also requires 3 hours of opioid continuing medical education for physicians with a Drug Enforcement Administration registration number and 3 hours of education about opioids for medical students (Arizona, 2018).

State agencies, in collaboration with other organizations, have also issued procedure-specific opioid prescribing guidelines. In 2015 the Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group, in collaboration with the Dr. Robert Bree Collaborative and an advisory group of the state’s academic leaders, pain experts, and surgeons, created the evidence-based Supplemental Guidance on Prescribing Opioid for Postoperative Pain and Dental Guideline on Prescribing Opioid for Acute Pain Management (Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group, 2019). The Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network—a public–private collaborative that receives support from the State of Michigan as well as federal funding sources—has developed procedure-specific opioid prescribing recommendations for patients undergoing 25 common surgical procedures such as dental extraction, appendectomy, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Michigan OPEN, 2019).

___________________

3 Epic Systems is one of the largest providers of health information technology, used primarily by large U.S. hospitals and health systems to access, organize, store, and share electronic health records.

4 See Corey Davis, The Network for Public Health Law Southeastern Region Office & the National Health Law Program, Appendix B, State-by-State Summary of Opioid Prescribing Regulations and Guidelines, at http://www.azdhs.gov/documents/prevention/womens-childrens-health/injury-prevention/opioid-prevention/appendix-b-state-by-state-summary.pdf (accessed August 5, 2019).

5 See Va. Admin. Code §§ 85-21-10–170, available at http://register.dls.virginia.gov/details.aspx?id=6295 (accessed August 5, 2019).

SOURCE: National Conference of State Legislators, StateNet (with permission).

Several states have used the CDC CPG for chronic pain6 as a model for their opioid guidelines. For example, the Oregon Health Authority publication Oregon Acute Opioid Prescribing Guidelines: Recommendations for Patients with Acute Pain Not Currently on Opioids, used the CDC CPG as the starting point (Oregon Health Authority, 2016), and Alaska, Connecticut, and Kentucky explicitly referenced the CDC CPG in their laws (Davis et al., 2019).

A few states (e.g., New Hampshire, Ohio, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin) authorize state entities to determine opioid prescribing limits. These entities may include departments of health, state and public health officials, or state boards of medicine, nursing, and dentistry. As state medical boards are the primary regulatory authority governing physicians who prescribe opioids, there is an incentive for state legislatures and state medical boards to work in tandem to craft opioid prescribing guidelines. Most of the state medical boards that provide guidelines recommend that nonopioid or nonpharmacologic pain management strategies be considered prior to initiating opioid therapy and that opioids be prescribed in limited amounts and doses consistent with the expected clinical course of pain (NASEM, 2017).

___________________

6 Most states specifically set exceptions for prescription limits for chronic pain treatment, cancer treatment, and palliative care, similar to the CDC guideline.

Along with prescribing limits, some state legislation mandates the use of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs),7 which are electronic databases that track controlled prescriptions. Every state, other than Missouri, has a PDMP. PDMPs provide access to a patient’s history of prescription opioids and help identify health care providers who prescribe high doses of opioids as well as patients who receive them. Evaluations of PDMPs have shown changes in prescribing behaviors, the use of multiple providers by patients, and decreased substance abuse treatment admissions (CDC, 2017). States have also issued policies mandating education for opioid prescribers as well as legislation requiring disclosure of the risks of opioid use and the importance of safe storage and disposal behaviors.

Local governments, including city health departments, have also issued opioid prescribing guidelines. For example, the New York City Department of Health developed opioid prescribing guidelines for primary care providers and then adapted these guidelines for ED discharge prescribing (Kattan et al., 2016; Nagel et al., 2018). The nine recommendations were modeled after the Washington State initiatives for regulating opioid prescribing that were intended to address the problem of excessive opioid prescribing in EDs (Chu et al., 2012; Juurlink et al., 2013). Among these recommendations are starting with the lowest dose of opioids, prescribing no more than a short course of opioids for acute pain (with more than 3 days rarely required), assessing patients for misuse or addiction, and avoiding initiating treatment with long-acting or extended-release opioids (Chu et al., 2012). The City of Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health has also issued postoperative opioid prescribing guidelines that recommend opioid discharge prescription limits for opioid-naïve patients in any of 13 medical specialties (Philadelphia Department of Public Health, 2018).

Given the array of competing guidelines for treating pain, there is the potential for recommendations to overlap or be contradictory. This may be particularly true when state prescribing limits are discordant with prescribing recommendations developed by national professional societies, potentially resulting in confusion or the malalignment of practice.

REFERENCES

AAPD (American Academy of Pediatric Dentristy). 2017. Policy on acute pediatric dental pain management. Pediatric Dentistry 39(6):99–101.

ACOEM (American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine). 2014. ACOEM occupational medicine practice guidelines. https://acoem.org/Practice-Resources/Practice-Guidelines-Center (accessed May 22, 2019).

ACOG (American College of Obsetricians and Gynecologists). 2019. Opioids. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Tobacco--Alcohol--and-Substance-Abuse/Opioids?IsMobileSet=false (accessed July 25, 2019).

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. 2018. ACOG committee opinion no. 742: Postpartum pain management. Obstetrics & Gynecology 132(1):e35–e43.

ADA (American Dental Association). 2018. Substance use disorders. https://www.ada.org/en/advocacy/current-policies/substance-use-disorders (accessed July 25, 2019).

AHIP (America’s Health Insurance Plans). 2019. Health plans work to find solutions to the opioid crisis. https://www.ahip.org/health-plans-launch-new-stop-initiative-to-help-battle-opioid-crisis-in-america (accessed September 27, 2019).

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2008. Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. Rockville, MD. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47095 (accessed April 16, 2019).

AHRQ. 2018. About NGC and NQMC. https://www.ahrq.gov/gam/about/index.html (accessed November 5, 2019).

AHRQ. 2019. Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) Program overview. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/overview/index.html (accessed November 5, 2019).

___________________

7 See EHRA, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs & Electronic Prescribing of Controlled Substances for a state-by-state summary of mandated PDMPs, at https://www.ehra.org/sites/ehra.org/files/EHRA%20PDMP%20-%20EPCS%20-%20State%20Landscape%20June%202018.pdf (accessed August 8, 2019).

American Academy of Audiology. 2006. The clinical practice guidelines development process. https://www.audiology.org/publications-resources/document-library/clinical-practice-guidelines-development-process (accessed August 22, 2019).

American Academy of Family Physicians. 2017. Clinical practice guideline manual. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/cpg-manual.html (accessed August 13, 2019).

Anand, K.J.S., and the International Evidence-Based Group for Neonatal Pain. 2001. Consensus statement for the prevention and management of pain in the newborn. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 155(2):73–180.

APTA (American Physical Therapy Association). 2018. APTA clinical practice guideline process manual. https://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/Practice_and_Patient_Care/Evidence_and_Research/Evidence_Tools/Components_of_EBP/CPGs/APTACPGManual2018.pdf (accessed April 26, 2019).

Arizona. 2018. Senate bill 1001. https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/53leg/1S/laws/0001.pdf (accessed September 27, 2019).

ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists). 2012. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology 116(2):248–273.

Bibbins-Domingo, K., E. Whitlock, T. Wolff, Q. Ngo-Metzger, W.R. Phillips, K.W. Davidson, A.H. Krist, J.S. Lin, C.M. Mangione, A.E. Kurth, F.A.R. García, S.J. Curry, D.C. Grossman, C.S. Landefeld, J.W. Epling, Jr., and A.L. Siu. 2017. Developing recommendations for evidence-based clinical preventive services for diverse populations: Methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force clinical preventive services recommendations for diverse populations. Annals of Internal Medicine 166(8):565–571.

Bohnert, A.S.B., G.P. Guy, Jr., and J.L. Losby. 2018. Opioid prescribing in the United States before and after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 opioid guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine 169(6):367–375.

Brandt, K. 2019. New Part D polices address opioid epidemic. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/blog/new-part-d-policies-address-opioid-epidemic (accessed September 27, 2019).

Brouwers, M.C., M.E. Kho, G.P. Browman, J.S. Burgers, F. Cluzeau, G. Feder, B. Fervers, I.D. Graham, J. Grimshaw, S.E. Hanna, P. Littlejohns, J. Makarski, L. Zitzelsberger, and the AGREE Next Steps Consortium. 2010. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Preventive Medicine 51(5):421–424.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2017. What states need to know about PDMPs. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdmp/states.html (accessed August 12, 2019).

Chiu, A.S., R.A. Jean, J.R. Hoag, M. Freedman-Weiss, J.M. Healy, and K.Y. Pei. 2018. Association of lowering default pill counts in electronic medical record systems with postoperative opioid prescribing. JAMA Surgery 153(11):1012–1019.

Chou, R. 2008. Using evidence in pain practice: Part I: Assessing quality of systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines. Pain Medicine 9(5):518–530.

Chu, J., B. Farmer, B.Y. Ginsburg, S.H. Hernandez, J.F. Kenny, N. Majlesi, L. Nelson, R. Olmedo, D. Olsen, J.G. Ryan, B. Simmons, M. Su, M. Touger, and S.W. Wiener. 2012. New York City emergency department discharge opioid prescribing guidelines. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/basas/opioid-prescribing-guidelines.pdf (accessed September 19, 2019).

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2018. 2019 Medicare Advantage and Part D rate announcement and call letter. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/2019-medicare-advantage-and-part-d-rate-announcement-and-call-letter (accessed September 27, 2019).

CMSS (Council of Medical Specialty Societies). 2017. CMSS principles for the development of specialty society clinical guidelines. https://cmss.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Revised-CMSS-Principles-for-Clinical-Practice-Guideline-Development.pdf (accessed April 26, 2019).

Cravero, J.P., R. Agarwal, C. Berde, P. Birmingham, C.J. Coté, J. Galinkin, L. Isaac, S. Kost-Byerly, D. Krodel, L. Maxwell, T. Voepel-Lewis, N. Sethna, and R. Wilder. 2019. The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia recommendations for the use of opioids in children during the perioperative period. Pediatric Anesthesia 29(6):547–571.

Davis, C.S., A.J. Lieberman, H. Hernandez-Delgado, and C. Suba. 2019. Laws limiting the prescribing or dispensing of opioids for acute pain in the United States: A national systematic legal review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 194:166–172.

Delgado, M.K., F.S. Shofer, M.S. Patel, S. Halpern, C. Edwards, Z.F. Meisel, and J. Perrone. 2018. Association between electronic medical record implementation of default opioid prescription quantities and prescribing behavior in two emergency departments. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(4):409–411.

Donovan, W. 2018. The epic problem with the CDC opioid guideline. https://ryortho.com/breaking/the-epic-problem-with-the-cdc-opioid-guideline (accessed August 8, 2019).

Dowell, D., T.M. Haegerich, and R. Chou. 2016. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. JAMA 315(15):1624–1645.

Dowell, D., T. Haegerich, and R. Chou. 2019. No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing. New England Journal of Medicine 380(24):2285–2287.

Guyatt, G.H., A.D. Oxman, H.J. Schünemann, P. Tugwell, and A. Knottnerus. 2011. GRADE guidelines: A new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64(4):380–382.

Higgins, J., J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M.J. Page, and V.A. Welch. 2019. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.0. http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed August 28, 2019).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1990. Clinical practice guidelines: Directions for a new program. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1992. Guidelines for clinical practice: From development to use. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1995. Setting priorities for clinical practice guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2008. Evidence-based medicine and the changing nature of healthcare. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011a. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011b. Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Juurlink, D.N., I.A. Dhalla, and L.S. Nelson. 2013. Improving opioid prescribing: The New York City recommendations. JAMA 309(9):879–880.

Kattan, J.A., E. Tuazon, D. Paone, D. Dowell, L. Vo, J.L. Starrels, C.M. Jones, and H.V. Kunins. 2016. Public health detailing—A successful strategy to promote judicious opioid analgesic prescribing. American Journal of Public Health 106(8):1430–1438.

Kemper, A.R., A.H. Krist, C.-W. Tseng, M.W. Gillman, I.R. Mabry-Hernandez, M. Silverstein, R. Chou, P. Lozano, B.N. Calonge, T.A. Wolff, and D.C. Grossman. 2018. Challenges in developing U.S. Preventive Services Task Force child health recommendations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 54(1):S63–S69.

Krist, A.H., T.A. Wolff, D.E. Jonas, R.P. Harris, M.L. LeFevre, A.R. Kemper, C.M. Mangione, C.-W. Tseng, and D.C. Grossman. 2018. Update on the methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Methods for understanding certainty and net benefit when making recommendations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 54(1):S11–S18.

Kroenke, K., D.P. Alford, C. Argoff, B. Canlas, E. Covington, J.W. Frank, K.J. Haake, S. Hanling, W.M. Hooten, S.G. Kertesz, R.L. Kravitz, E.E. Krebs, S.P. Stanos, and M. Sullivan. 2019. Challenges with implementing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention opioid guideline: A consensus panel report. Pain Medicine 20(4):724–735.

Linda, M.G., C. Ya-Lin, C. Nancy, H. Roger, and G. Jamshid. 2013. Marked reduction in mortality in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurosurgery 119(6):1583–1590.

Michigan OPEN (Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network). 2019. Prescribing recommendations. https://michigan-open.org/prescribing-recommendations (accessed August 13, 2019).

Motov, S., R. Strayer, B.D. Hayes, M. Reiter, S. Rosenbaum, M. Richman, Z. Repanshek, S. Taylor, B. Friedman, G. Vilke, and D. Lasoff. The treatment of acute pain in the emergency department: A white paper position statement prepared for the American Academy of Emergency Medicine. Journal of Emergency Medicine 54(5):731–736.

Mueller, K., W. Woo, M. Cloeren, K. Hegmann, and D. Martin. 2016. ACOEM guidance statement: Principles for ensuring the safe management of pain medication prescriptions by occupational and environmental medicine physicians. https://acoem.org/acoem/media/News-Library/Principles-for-Ensuring-Safe-Management-of-Pain-Meds.pdf (accessed July 28, 2019).

Murad, M.H. 2017. Clinical practice guidelines: A primer on development and dissemination. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 92(3):423–433.

Nagel, F.W., J.A. Kattan, S. Mantha, L.S. Nelson, H.V. Kunins, and D. Paone. 2018. Promoting health department opioid-prescribing guidelines for New York City emergency departments: A qualitative evaluation. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 24(4):306–309.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Pain management and the opioid epidemic: Balancing societal and individual benefits and risks of prescription opioid use. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NCSL (National Conference of State Legislators). 2018. Prescribing policies: States confront opioid overdose epidemic. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/prescribing-policies-states-confront-opioid-overdose-epidemic.aspx (accessed August 5, 2019).

Oregon Health Authority. 2018. Oregon acute opioid prescribing guidelines: Recommendations for patients with acute pain not currently on opioids. Public Health Division. https://www.oregon.gov/obnm/rules/AcuteOpioidPrescribingGuidelines.10.2018.pdf (accessed September 27, 2019).

Philadelphia Department of Public Health. 2018. Postoperative opioid prescribing guidelines. https://www.phila.gov/media/20181219135328/OpioidGuidelines-12_14.pdf (accessed August 19, 2019).

PhRMA (Pharmaceutical Research and Manufactuters of America). 2017. PhRMA announces major commitment to address the opioid crisis in America. https://www.phrma.org/press-release/phrma-announces-major-commitment-to-address-the-opioid-crisis-in-america (accessed October 2, 2019).

Shekelle, P.G. 2014. Updating practice guidelines. JAMA 311(20):2072–2073.

Siemieniuk, R., and G. Guyatt. 2019. What is GRADE? https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/us/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade (accessed April 26, 2019).

Straus, S.E., P. Glaszious, W.S. Richardson, and R.B. Haynes. 2019. Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM, 5th edition. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier Limited.

USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force). 2018a. Procedure manual. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/procedure-manual (accessed April 26, 2019).

USPSTF. 2018b. Standards for guideline development. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/standards-for-guideline-development (accessed April 26, 2019).

VA/DoD (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense). 2017. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Version 3.0. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/VADoDOTCPG022717.pdf (accessed September 27, 2019).

VA/DoD. 2019. Guidelines for guidelines. https://www.qmo.amedd.army.mil/general_documents/GuidelinesforGuidelines.pdf (accessed September 27, 2019).

Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group. 2019. AMDG. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov (accessed August 23, 2019).

Whitlock, E.P., M. Eder, J.H. Thompson, D.E. Jonas, C.V. Evans, J.M. Guirguis-Blake, and J.S. Lin. 2017. An approach to addressing subpopulation considerations in systematic reviews: The experience of reviewers supporting the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Systematic Reviews 6(1):41.

This page intentionally left blank.