4

Framework for Developing Clinical Practice Guidelines

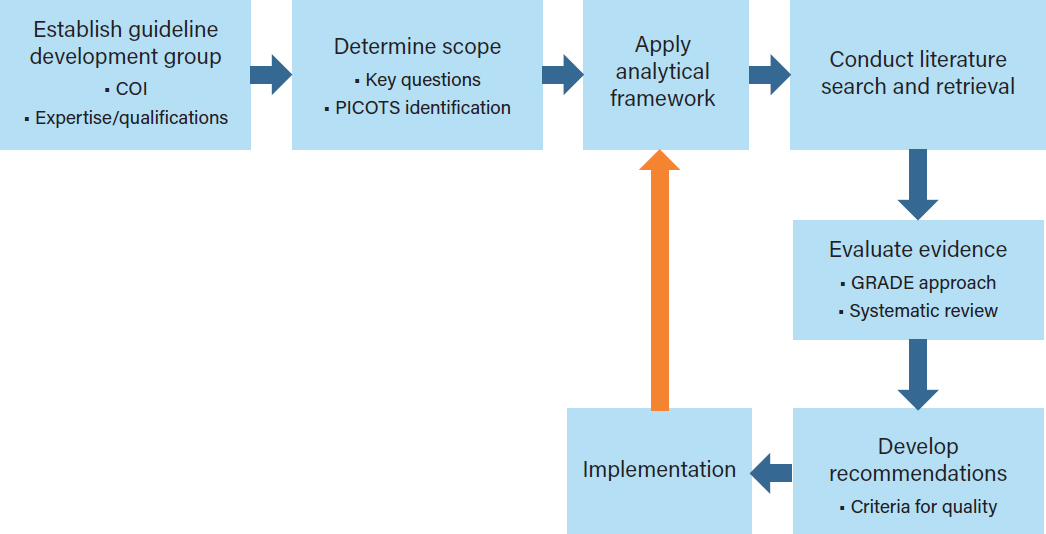

The 2011 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust states, “Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) fundamentally rest on appraisal of the quality of relevant evidence, comparison of the benefits and harms of particular clinical recommendations, and value judgments regarding the importance of specific benefits and harms” (IOM, 2011a, p. 110). Effective and trustworthy CPGs are based on a rigorous review and analysis of the relevant scientific evidence (IOM, 1992, 2011a; Woolf et al., 2012). The review and analysis are parts of a guideline development process that begins with identifying the need for a guideline for a specific surgical or medical indication and then continues with the selection of guideline developers, gathering the scientific evidence, and, finally, approving, disseminating, and assessing the use of the guideline in a continuous quality improvement context (see Figure 4-1).

The development of CPGs is based on two frameworks: an analytic framework, which organizes the specific information required by a group to arrive at a recommendation, and an evidence evaluation framework, which describes the methods for assessing the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The implementation of these frameworks and the dissemination and use of CPGs after they are developed are also important steps in the CPG process. This chapter briefly addresses the entire CPG development process and provides a more in-depth discussion of the analytic framework and the evidence evaluation framework. It also considers how the use of CPGs by clinicians and other health care professionals might be enhanced.

As described in Chapter 3, numerous organizations have developed thoughtful, comprehensive, and widely used processes for developing CPGs. The committee considered that existing body of work when developing the two frameworks in this chapter, with a particular focus on the work by the IOM, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group, the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Collaborative, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, 2015; Brouwers et al., 2010; Guyatt et al., 2008b; IOM, 2011a,b; USPSTF, 2018).

NOTE: COI=conflict of interest; GRADE=Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation;

PICOTS=patient, problem, or population; intervention; comparison, control, or comparator; outcome; time; and setting.

In addition to the two frameworks, the committee also considered how CPGs for opioid prescribing might be used by clinicians. In the last section of this chapter, the committee briefly addresses four aspects of CPG implementation: dissemination, uptake, adherence, and monitoring outcomes.

THE CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

The process for developing CPGs follows three core principles: (1) guidelines should be based on evidence that evaluates the efficacy or effectiveness of interventions on health outcomes, (2) guidelines should use the highest-quality evidence available, and (3) guidelines are developed for application to patient populations, but should allow for the individualization of care when possible (Balshem et al., 2011; Brouwers et al., 2010; Guirguis-Blake et al., 2007; IOM, 2011a; Nobrega et al., 2018; Radcliff et al., 2017; Rahim-Williams et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2019).

To address these core principles, the committee’s overarching CPG development process provides a stepped process for assessing available evidence on opioid prescribing for acute pain indications, identifying research needs, and facilitating the incorporation of new knowledge into clinical practice as it becomes available (see Figure 4-1). Inherent in this process is the understanding that for many indications there are equal or superior nonopioid pain management strategies that might be considered and, in some cases, prescribed and used. However, for some medical indications of acute pain, such as

long bone fractures, sickle cell crisis, and many surgical procedures, initial therapy with a nonopioid or nonopharmacologic treatment may not be appropriate or feasible; for many indications, opioids are a recognized first-line treatment either alone (e.g., for femur fracture presenting in an emergency department [ED]) or in conjunction with nonopioid or nonpharmacologic treatments or both (Chou et al., 2016; Gross and Gordon, 2019; Motov et al., 2018). The committee recognizes that nonopioid modalities may be first-line treatments for some types of acute pain and that opioids may not be indicated for the management of acute pain for these conditions. However, the committee acknowledges that there are significant gaps in comparative studies examining opioid, nonopioid, and nonpharmacologic therapies, especially in perioperative pain management (Gordon et al., 2016).

ESTABLISHING A GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT GROUP

CPGs with optimal impact are created with the end user and stakeholders (e.g., patients, insurers, ancillary health providers) in mind. To achieve this impact, guideline developers consider which health care professionals are most likely to care for such patients individually or as a part of a team—that is, the clinicians who will be using the CPG. CPGs may also address additional health care providers who are involved in a patient’s care as well as the health care organizations that are key partners in the development process.

As discussed at some length in the 2011 IOM report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, the first step in creating an evidence-based CPG is to identify and assemble a group of involved and interested experts who will develop it. Carefully selecting experts to ensure appropriate representation from all key stakeholders and health care providers and to include methodologists, epidemiologists, and statisticians will strengthens the developmental rigor and applicability of the evidence-based CPG (IOM, 2011a). Moreover, given the importance of social determinants of health (see Chapter 3) and the national impact of the opioid epidemic, it is desirable to ensure diversity among the guideline developers with regard to race, gender, age, and geographic location. The 2011 IOM report on guideline development and reports by similar groups such as GRADE have encouraged the incorporation of the patient perspective in the guideline development process; adding this perspective helps support the goal of patient-centered care.

Numerous organizations have stressed the need to reduce the susceptibility of guideline development groups to conflicts of interest and have established detailed procedures for assessing and managing both financial and non-financial conflicts (IOM, 2011a; USPSTF, 2018; WHO, 2015). Once potential group members have been identified, any conflicts of interest they have may be posted publicly to enhance transparency. One publicly available tool for identifying financial conflicts of interest is the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services’ Open Payments national disclosure program, which publicly lists the financial relationships between applicable manufacturers and group purchasing organizations and physicians or teaching hospitals; however, other health care providers may not be included in Open Payments. The committee notes that although it is desirable to have experts from particular fields on CPG development groups, the very nature of their expertise may result in them having conflicts of interest that need to be disclosed.

DETERMINING THE SCOPE OF THE GUIDELINE

The first goal of the CPG development group is to determine the scope of the guideline, including the specific indications to be covered, as well as the populations, interventions, outcomes, and settings

to be addressed. The 2011 IOM report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust recommends that guideline groups consider

a variety of clinical issues, including benefits and harms of different treatment options; identification of risk factors for conditions; diagnostic criteria for conditions; prognostic factors with and without treatment; resources associated with different diagnostic or treatment options; the potential presence of comorbid conditions; and patient experiences with health care interventions. (IOM, 2011, p. 98)

CPGs typically focus on clinical studies, which may be informed by basic research on opioids, including animal models. In the absence of clinical studies, basic research studies might be used to inform recommendations but these would be considered to be weak evidence.

USPSTF CPGs provide recommendations on clinical prevention activities such as screening for disease. The USPSTF procedure manual (2015) provides information on how to prioritize issues to be addressed in the CPG, how to frame key questions, and which outcomes to include. The manual states that its

goal for topic selection and prioritization is to provide accurate and relevant recommendations that are as up to date as possible and to balance the overall portfolio of recommendations by population, type of service (e.g., screening, counseling, preventive medication), type of disease (e.g., cancer, endocrine disease), and size of project (e.g., update vs. new topic). (USPSTF, 2018)

AHRQ has a similar approach for prioritizing topics for comparative-effectiveness systematic reviews that includes clear and consistent criteria for prioritizing program activities and emphasizes the need to engage stakeholders in the process (Totten et al., 2019).

The goal of CPGs is to inform clinical practice and policy. However, recent experience indicates that some CPGs may be applied to situations for which they were not developed, with potential unintended consequences. For example, the 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CPG for chronic pain was used by many health care providers, insurers, and state regulators to limit prescribing for populations not intended for inclusion in the guideline, such as those who were opioid tolerant or who were currently prescribed higher doses than recommended. The harms of such misinterpretation have been discussed (Dowell et al., 2019; Kroenke et al., 2019). It is critical that CPGs clearly describe their scope as well as the clinical recommendations to help avoid such situations. Engaging a variety of stakeholders (including patients, payers, and policy makers) in the CPG guideline development process might help reduce unintended applications.

To delineate what surgical or medical indications the guidelines cover, a statement of scope and setting for the CPG is needed (e.g., policy, settings, patient populations, practitioner types). Such a statement is based on a clear description of the patient, problem, or population (P); intervention (I); comparison, control, or comparator (C); outcome (O); time (T); and setting (S)—the PICOTS framework (Schardt et al., 2007; University of Canberra, 2019). The scope of the CPG will be largely based on the PICOTS addressed in the key questions and supported by the systematic literature reviews. The PICOTS framework is used to identify the relevant literature and inform the evidence evaluation process. Health equity issues for various populations and indications may also be considered in the statement of scope (Welch et al., 2017).

Transparent and rigorous methods for guideline development will help optimize their acceptance and application. Together the key questions (discussed in the next section) and the PICOTS framework define the scope of the guideline, inform the analytic framework, and set the stage for the application of the evidence evaluation framework.

ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK

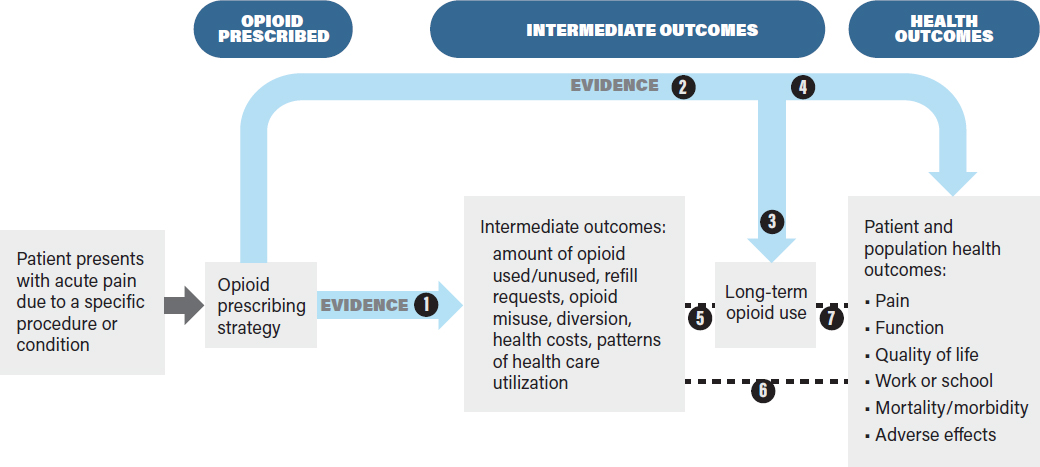

The analytic framework in Figure 4-2 identifies the evidence linkages to be evaluated in a systematic review of the effects of an intervention on health outcomes. The purpose of the analytic framework is to visually depict the evidence that CPG developers need to assess in order to make recommendations on opioid prescribing by indicating the populations addressed, treatment decisions, key health outcomes (rightmost box), the intermediate health outcomes associated with those health outcomes, the linkages between intermediate and health outcomes, and harms.

This framework, while specific to opioids, might be applied to other treatments for pain, including nonpharmacologic ones. It is based on the principle that interventions should improve overall health outcomes, not just intermediate outcomes, and that evaluations of interventions should be based on an assessment of benefits as well as harms. Defining the outcomes and showing the evidence linkages provides a structured framework by which CPG developers can assess the benefits and drawbacks of a given decision (in this case, different opioid prescribing strategies) (Harris et al., 2001; Woolf et al., 2012). The analytic framework enables guideline developers to articulate current evidence gaps and also potential obstacles to establishing the evidence base for assessing the outcomes of different opioid prescribing strategies.

Conceptual Rationale

The analytic framework presents a “roadmap” or chain of logic to guide the process of reviewing evidence to assess the outcomes associated with opioid prescribing for acute pain (Guirguis-Blake et al., 2007; Woolf et al., 2012). In general, analytic frameworks guide decision makers by showing how clinical treatment decisions (in the context of specific patient characteristics and needs) are linked to downstream outcomes of interest. Consistent with the committee’s Statement of Task, the analytic framework is based on the assumption that opioids are appropriate for the management of the patient’s acute pain and that the decision of interest is the optimal prescribing strategy. The analytic framework could be modified to incorporate effects of nonopioid therapies used either prior to or concurrently with opioids. The analytic framework indicates the key questions (typically using a PICOTS framework) (see Box 4-1) that will guide a literature review conducted to gather evidence to support the CPG.

The analytic framework clearly distinguishes intermediate outcomes from health outcomes (Wolff et al., 2018). Health outcomes are “symptoms, functional levels, and conditions that patients can feel or experience” (USPSTF, 2018), and they affect how long a patient lives or the quality of his or her life. For opioid prescribing for acute pain, important health outcomes include mortality, overdose, pain, function, adverse effects (e.g., psychological effects such as depression and anxiety), and quality of life. Intermediate outcomes for opioid prescribing strategies refer to outcomes that do not directly measure health outcomes, but rather measure events or endpoints that may be associated with health outcomes, such as the amount of opioid medication used versus the amount prescribed, the number of refill requests, misuse behaviors, health care use, or long-term opioid use. Both intermediate and health outcomes can be measured at short- or long-term follow-up and are important for the development of evidence-based CPGs.

Proposed Linkages

The analytic framework in Figure 4-2 links the opioid prescribing strategies to intermediate outcomes (e.g., the amount of opioid used, refill requests, long-term opioid use) and to health outcomes (e.g., pain, functional status, mortality, and opioid-related adverse effects). As noted earlier, the analytic framework begins with the assumption that opioids will be used to treat the patient’s acute pain. In the analytic framework, health outcomes may be linked directly to the opioid prescribing strategy (e.g., by studies comparing effects of different opioid prescribing strategies on pain, quality of life, or risk of opioid use disorder). When such evidence is limited or not available, the analytic framework also shows how the effects of an opioid prescribing strategy on health outcomes can be assessed indirectly via a chain of evidence involving intermediate outcomes. Intermediate outcomes may be useful for assessing the effects of opioid prescribing strategies when data on health outcomes are lacking and when the intermediate outcomes (e.g., number of unused opioid pills) are reliable proxies for health outcomes (e.g., accidental overdose) (Deschamps et al., 2019; Wolff et al., 2018). When there is sufficient direct evidence to evaluate the effects of an opioid prescribing strategy on health outcomes, it is not necessary to evaluate the effects on intermediate outcomes. Ultimately, the goal of the analytic framework is to link an opioid prescribing strategy with health outcomes so that the best prescribing strategy can be chosen on the basis of having the best health outcomes while minimizing opioid-related harms.

Patient Populations

The patient populations to be studied for a given prescribing strategy are defined during the scoping process described earlier. The prescribing strategies to be evaluated in the analytic framework may be based on the characteristics of the patient population in the study. These characteristics include the indication for pain (e.g., underlying medical condition or surgical procedure), demographic factors (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity), clinical factors (e.g., the presence of chronic pain, prior opioid use, the use of other medications or therapies, substance use history, psychiatric comorbidities, medical comorbidities), and practice setting (e.g., primary care, inpatient, ED). For example, the patient population to be studied for opioid prescribing, such as patients with a particular indication (e.g., low back pain), children, or patients who have substance use disorder, could be defined in the scoping process and evaluated with the analytic framework. Many of the studies cited in Chapters 2 and 6 explicitly state whether the study populations are opioid naïve, have prior opioid use, or have conditions that may affect their use of opioids for acute pain (e.g., Badreldin et al., 2018a; Bicket et al., 2019; Mudumbai et al., 2019). These patient factors are likely to be important for understanding the effects of opioid prescribing strategies and will help in individualizing such strategies; ideally they would be addressed in the analytic framework and subsequent CPG.

The effects of potential modifying factors within a population (e.g., children) can be evaluated through subgroup analysis after, for example, stratifying by age (e.g., children less than 5 years of age or older than 12 years of age). Other modifying factors that may need to be considered include sex, age, concurrent health concerns, and the use of prescription or over-the-counter therapeutics. Prescribing strategies may be assessed for a combination of pain conditions as well as for specific indications. Patient risk factors also need to be considered, such as whether patients are opioid naïve or have preexisting opioid use or whether they have underlying mental health issues that may be exacerbated by opioids. Relevant modifying and risk factors should be articulated in the key questions and presented when describing the patient population to be studied and the study results. Explicit and well-defined study populations, including comparison groups when appropriate, are important for ensuring that the subsequent studies provide the necessary evidence to determine the effectiveness of a prescribing strategy.

Opioid Prescribing Strategies

The prescribing strategies indicated in the analytic framework are generally taken to mean that different opioid prescribing strategies are being compared across comparable populations with the same acute pain diagnosis (e.g., low back pain). For example, opioid prescribing strategies may refer to variations in the amount (dose or duration or both) of opioids that are prescribed (e.g., opioids for 3 days or 7 days or a dose of 20 morphine milligram equivalents [MMEs] versus 40 MMEs) for a particular indication (e.g., low back pain) or population (e.g., pediatric or geriatric patients); thus the effectiveness of one prescribing strategy may be compared with the effectiveness of another prescribing strategy (Daniels et al., 2011; Friedman et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2017; Pathan et al., 2018). Converting opioid doses to MMEs allows for evaluation of opioid prescribing strategies that involve different opioids and formulations; the method or tables used to make the conversions should be indicated. For example, if hydrocodone, tramadol, and oxycodone are all reported MMEs, evaluating their effects may be facilitated. MMEs may not be the only factor informing or defining prescribing strategies—the route of administration or the specific opioid could also affect outcomes. CPGs should be clear about whether they address the route of administration or the use of a specific opioid.

Most assessments of opioid prescribing strategies have focused on effects of the amount of opioids prescribed, the number of unused opioid pills, and refill rates. However, some studies have evaluated effects of opioid prescribing strategies on health outcomes. For example, the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota evaluated opioid prescribing across 25 elective surgical procedures to determine what prescribing strategies were effective in reducing patient postoperative pain with the least number of leftover pills (Thiels et al., 2018). The survey results indicated that although the majority of patients were satisfied with their postoperative pain control regardless of the procedures performed, about 9% of the patients reported that their pain was not controlled with their discharge prescription of opioids.

A number of prescribing strategies have been developed based on patient-reported data on actual opioid use. For example, at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center prescribing guidelines have been developed based on an internal assessment of postoperative prescribing practices for five inpatient surgeries and patients reports of pain management after discharge. Researchers found that the amount of opioids taken the day before discharge was highly correlated with the amount used after discharge (Hill et al., 2018). The Mayo Clinic (Thiels et al., 2018) and the Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network guidelines (PDOAC, 2018) are based on institutional assessments of the amount of opioids prescribed postoperatively versus the amount of opioids actually used by the patients for a variety of surgical procedures. Building on the concept of developing an opioid prescribing strategy that reduces the gaps between the amount of opioids prescribed and the amount used, some researchers and health care systems have begun attempting to “right size” opioid prescriptions by changing electronic health record (EHR) prescribing defaults, with some reports of success (Delgado et al., 2018). Although many of these studies do examine some short-term outcomes, including patient-reported pain, satisfaction, and the need for refills, they generally support the development of an opioid prescribing strategy and do not evaluate an already implemented strategy in terms of broader health outcomes.

The examples of the Mayo Clinic and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center guidelines highlight how to determine what opioid dosing strategies to evaluate, and are based on correlations and actual opioid use, but they do not compare one prescribing strategy with another. The analytic framework however, would compare the Dartmouth or Mayo approach with usual care or another prescribing strategy to determine if either the Dartmouth or Mayo approach actually reduces the amount of opioids used to achieve similar pain relief or other health outcome.

Intermediate Outcomes

Intermediate outcomes for opioid prescribing strategies at both the patient and the health care system level may include such markers as the amount of opioids used or unused, refill requests, and other measures of opioid use. The amount of opioids used by an individual may be a marker for long-term use and is associated with adverse health outcomes such as overdose (Babu et al., 2019; Deyo et al., 2017; Liang and Turner, 2015). Other intermediate outcomes that may be assessed include the development of tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal for both individuals and populations. The committee notes that these outcomes may be difficult to measure and may be highly variable among individuals. Limiting the number of MMEs, pills, or days of opioids to a level that is sufficient for the vast majority but not all patients with a specific condition means that some patients will have inadequate pain control with the amount prescribed. In lieu of evidence directly measuring the effects of an opioid prescribing strategy on pain, the number of refills requested and filled may be markers of inadequate pain control, a key outcome when applying these strategies to patients without ready access to refills. Conversely, basing opioid prescribing recommendations on patients with higher opioid requirements could mean more excess pills for the majority of patients. It is important that CPGs be transparent about how the trade-off between decreased opioid use and inadequate pain relief is evaluated.

Intermediate outcomes can be measured at short- or long-term periods after the intervention. Long-term opioid use, an intermediate outcome, does not directly measure effects on patient morbidity, mortality, or other health outcomes, but it may be a stronger marker for long-term adverse health consequences such as opioid use disorder and overdose than measures of short-term opioid use (Bohnert et al., 2011). Some studies on acute prescribing have assessed the long-term use of opioids (Brat et al., 2018; Brummett et al., 2017; Schroeder et al., 2019; Shah et al., 2017).

Intermediate outcomes can be assessed at the individual patient or health care system level, both of which may be useful for evaluating opioid prescribing strategies and clinical prescribing recommendations. For example, opioid use can be measured at the individual, health care system, or state levels. Assessing the diversion of unused pills from the prescription recipient to others and the misuse of opioids by the prescription recipient (e.g., use of the opioids for other purposes, such as a sleep aid) may also be predictive of opioid use disorder and its associated outcomes, such as overdose (Han et al., 2017).

Health Outcomes

The ultimate goal of an opioid prescribing strategy should be improved health outcomes and reduced opioid-related harms. A comprehensive assessment of health outcomes takes into account short- and long-term outcomes for the individual patient with acute pain and also for the community or population to which the patient belongs. Box 4-2 lists some of the short- and long-term health outcomes associated

with the use of opioids for acute pain (Ferreira et al., 2002). Specific outcomes may be more important for some patients and communities than others. For example, patients may be willing to tolerate a certain level of pain if they are able to resume a favorite activity, whereas a community may be concerned with an increase in opioid overdose deaths rather than concerned about all individuals returning to work. When reviewing the evidence to identify an opioid prescribing strategy, the CPG developers should consider all relevant health outcomes, including adverse effects that may occur following opioid use, which may include but are not limited to constipation, nausea, sedation, respiratory depression, and hyperalgesia (Benyamin et al., 2008). Opioids have also been associated with disrupted sleep patterns in both current and past users (Gordon, 2019). Increased mortality and morbidity may include substance use disorder, opioid overdoses, and deaths from overdoses. For some patients, outcomes such as improved function, return to work, or the ability to breastfeed an infant may be more important goals than the elimination of pain. The health outcomes to be considered by the CPG developers should be determined in the scoping step described earlier. Thus, it is important that CPGs are transparent about the methods they use to prioritize outcomes.

Large-scale studies that evaluate outcomes in large populations on a community or population level, or both, would help address important unanswered questions such as (1) Does the reduced potential for opioid diversion result in fewer people who start to misuse prescription opioids? versus (2) Does the reduced potential for opioid diversion result in a higher conversion rate of prescription opioid users and misusers to nonprescription opioid users? (NASEM, 2017).

LITERATURE SEARCH AND RETRIEVAL

The analytic framework identifies the links where evidence needs to be gathered and reviewed on opioid prescribing strategies. Gathering that evidence requires that a comprehensive and well-structured literature search be conducted on the basis of the PICOTS framework developed during the earlier scoping step.

Many organizations have established standard methods for searching the literature, such as the 2011 IOM report Finding What Works in Health Care (IOM, 2011b), the 2018 USPSTF Procedure Manual, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al., 2019), and the 2015 AHRQ Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (AHRQ, 2015). Each of these documents discusses the need to have qualified information specialists conduct the searches using relevant terms that have been discussed with the guideline developers who will be using the results (Shekelle et al., 1999).

EVIDENCE EVALUATION FRAMEWORK

The evidence evaluation framework outlines a process by which CPG developers may assess the evidence indicated by the linkages in Figure 4-2. Such evaluations can then be used to determine the strength of recommendations for an effective opioid prescribing strategy.

Conceptual Approach

The primary concept in the evidence evaluation framework is that the most effective and trustworthy guidelines are based on the highest-quality evidence. Discussions of “quality” have often focused on issues related to the internal validity and risk of bias. However, as noted in the 2011 IOM report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, the concept of quality can be broad, that is “the level of confidence

or certainty in a conclusion regarding the issue to which the evidence relates,” with that confidence and certainty frequently expressed as numeric grades or scores of the evidence. The IOM report also noted that the quality of evidence can incorporate other considerations, such as those described by Verkerk et al. (2006, p. 110):

the relevance of available evidence to a patient with particular characteristics; the quantity (i.e., volume and completeness) and consistency (i.e., conformity of findings across investigations) of available evidence; and the nature and estimated magnitude of particular impacts of an individual clinical practice and value judgments regarding the relative importance of those different impacts.

A key issue that arises in using the analytic framework shown in Figure 4-2 is that while ideally there would be a strong evidence base linking each opioid prescribing strategy to a health outcomes, in practice such studies, particularly randomized controlled trials (RCTs) may not be available and can be difficult to conduct, particularly for longer-term outcomes. Thus, the preponderance of evidence will most likely be derived from observational studies, which are useful, but more susceptible to bias and confounding. Therefore, the quality of the overall evidence base for the effectiveness of any specific opioid prescribing strategy is likely to be low. Assessing the effects of opioid prescribing strategies on health outcomes may be difficult, particularly for longer-term and population-level outcomes. Assessing how these strategies affect intermediate outcomes, such as the amount of opioid prescribed or used, may be easier and, indeed, many studies have done so (Hill et al., 2018; Larach et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019). These studies, in the absence of higher-level evidence, may best inform recommendations to reduce excess prescribing and minimize the flow of unused opioids available for diversion to unintended users until better evidence is available.

For many indications, the committee expects that there will be little evidence linking a prescribing strategy to health outcomes, so that indirect evidence on intermediate outcomes will need to be used for the development of CPGs. Evidence can be used to establish the linkages between opioid prescribing strategies and health outcomes via intermediate outcomes.

Types of Evidence

CPGs consider various types of evidence in order to assess the linkages between specific opioid prescribing strategies and intermediate health outcomes in patients with acute pain (White and Schmidler, 2018) (see Figure 4-2). RCTs, observational studies, and quality improvement initiatives may provide evidence for the linkages in the analytic framework, usually evaluated by conducting a systematic review. Each of these types of evidence is discussed below. Although expert opinions are sometimes cited as evidence in CPGs, when they are included they are considered the weakest form of evidence (Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination, 1988; Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2009). Furthermore, the use of the term “expert opinion” is subject to various interpretations depending on the CPG development process. CPGs may need to rely on expert opinion when published evidence is lacking; if there are other reasons for using expert opinion for a CPG, they should be described.

All CPGs require a consensus process to make recommendations, although the specific process used can vary from informal, ad hoc methods to formal consensus methods such as Delphi. An analysis of 69 published guidelines using expert consensus as a means to formulate recommendations found that a rationale for using this method was lacking in 91% of the recommendations. Therefore, when expert consensus is used to develop a CPG, it is important that the developers define what expert consensus means and describe the methods by which it was reached (Ponce et al., 2017).

Randomized Controlled Trials

RCTs, the gold standard for assessing clinical interventions, compare the effect of an intervention with a control (either another intervention or a placebo). The main advantages of RCTs are that, if conducted well, they are the study design most able to minimize or reduce the risk of bias when assessing the effects of interventions. Importantly, the randomization of patients to intervention or control groups removes allocation bias, with the two groups having an unbiased and equal distribution of potential confounders, assuming an adequate sample size (Süt, 2014). The disadvantages of RCTs are that they are typically expensive and time-consuming to perform and that they are often designed in ways that limit the applicability of the findings to clinical practice (Corrigan-Curay et al., 2018). For example, an RCT may enroll only populations that are at low risk of harm (e.g., excluding patients with prior substance use disorders or psychiatric disorders), or it may evaluate an intervention such as a method to enhance adherence that is not feasible in clinical practice (e.g., having a nurse follow-up with a patient on a daily basis).

Of concern for this report is that few RCTs comparing health outcomes of different opioid prescribing strategies have been conducted and published. Given the extensive resource demands of conducting RCTs, they may most easily be designed to evaluate immediate outcomes (e.g., opioid use) or short-term health outcomes (e.g., a reduction in acute pain or improvements in patient function) rather than long-term or uncommon outcomes. For example, it is challenging to conduct RCTs to assess harmful outcomes such as opioid overdose, the development of opioid use disorder, or the development or persistence of chronic pain and reduced quality of life. Other limitations for RCTs include restrictive eligibility criteria, resulting in populations that are easier to evaluate and more likely to respond to a given treatment, and a loss of study participants over time.

The committee recognizes the challenges in carrying out long-term RCTs to assess the effects of opioid prescribing strategies on such outcomes as overdose and opioid use disorder at the individual or population level. One of the major challenges of conducting this type of study is accurately ascertaining the adverse events. For example, overdoses may be mis- or underreported, may occur outside the study venue (e.g., at a different health care facility), or, in the case of death, may not be reported to the researchers at all. The committee notes that new technologies such as machine learning, particularly the use of logic and algorithms, may improve patient selection, provide predictive long-term outcomes, reduce the time and cost of clinical trials, and improve researchers’ ability to process large datasets (Rademacher, 2019). RCTs may also need to control for factors such as the variability in health insurance for the study population or changes to opioid prescribing policies at the individual prescriber, institution, insurer, or state levels.

Observational Studies

In observational studies, researchers make no attempt to affect the outcome of an intervention in a population (NCI, 2019), nor do the researchers control how subjects are assigned to groups or which intervention each group receives (Stat Trek, 2019). Observational studies may be descriptive (e.g., case-report, case series) or analytic (e.g., prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies) (Süt, 2014). Data sources include administrative databases, clinical registries, EHRs, and directly querying patients via surveys or interviews. However, all of these data sources have potential problems, such as the accurate measurement of interventions and the determination of both intermediate and health outcomes. Nevertheless, there are methods that researchers may use to reduce the variability in the data. For example, observational studies based on insurance claims data will typically not provide direct information on pill use, but pill use may be inferred by the timing of refill requests or

by querying patients. The committee notes that observational studies based on administrative or EHR data may not capture patient-centered outcomes such as return to work or improved mobility. Therefore, these studies may need to combine administrative data with data on patient-reported outcomes—for example, unused pills, pain control, and functional status—gathered using methods such as patient surveys to provide a more complete picture of the outcomes of opioid prescribing. Retrospective studies that query patients about past exposures may be subject to recall bias, particularly when the patient is asked to recall information several months in the past; although, there are techniques that may be used to reduce this bias such as timeline follow back.

Observational studies have several potential advantages over RCTs. While RCTs often enroll a relatively small number of selected participants who meet eligibility criteria, populations in observational studies may better reflect the broader range of patients seen in clinical practice. Observational studies are generally more efficient and require fewer resources, enabling evaluation of larger samples of participants and longer follow-up for outcomes, including patient-centered outcomes such as improved quality of life. The main drawback to observational studies is that they are more susceptible to bias and confounding than well-conducted RCTs. As with RCTs, an observational study may also have poor generalizability or applicability to nonstudy populations if appropriate consideration is not given to how the study populations are defined and obtained, what interventions are to be assessed, what outcomes are evaluated, and what comparisons are to be made. Short-term efficacy outcomes and opioid use outcomes may be more reliably—though not exclusively—assessed in RCTs because they are less susceptible to bias and other issues associated with observational studies (Anglemyer et al., 2014; Hannan, 2008).

The link between intermediate outcomes and health outcomes has to be evaluated by observational studies, as it is not possible to randomize patients to an intermediate outcome. The limitations of observational studies for supporting such linkages also need to be recognized. A major limitation is that the observed association between intermediate and health outcomes can be the result of measured and unmeasured confounding variables. It is critical that such studies control for potential confounders (e.g., age, sex, pain severity, and comorbidities). Other limitations of observational studies may include temporal confounders, changes in the use of other interventions such as opioid-sparing approaches, differences in case mix and selection bias, measurement bias with respect to assessing pain, and opioid-related outcomes.

Quality Improvement Initiatives

Quality improvement initiatives examine the implementation of interventions designed to enhance the quality of clinical care and encourage the uptake of best practices. These initiatives are focused on pragmatic changes intended to address a specific clinical problem, and they typically take advantage of nonrandomized designs examining the effect of a health intervention by examining specific outcomes prior to and after implementation (Chassin and Loeb, 2011). Quality improvement initiatives may be designed specifically to affect local environments, such as institutions or health care systems, and often integrate immediate feedback in order to refine the interventions and optimize their implementation. However, quality improvement initiatives may not explicitly address hypothesis testing, may not assess and minimize bias, and may not provide findings that are generalizable to other populations (Itri et al., 2017). Although each of these components (hypothesis testing, bias evaluation, generalizing findings) may be considered in these studies, they are secondary priorities. Quality improvement initiatives may also commonly involve the creation of targets for best practices, performance assessment, feedback to key stakeholders, and education about and dissemination of interventions.

Quality improvement initiatives may be advantageous in that they allow for the rapid assessment of potential interventions in order to address urgent or important clinical problems, particularly those in which more rigorous designs may be costly, logistically difficult, or ethically challenging (Neuhauser and Diaz, 2007). For example, it may not be feasible to randomize or blind participants to an intervention, or it may be challenging to accrue a sufficiently homogeneous sample in a study with numerous exclusion criteria. In this context, quality improvement initiative designs may lack sufficient rigor to assess causality, and issues with confounding, mediating, and moderating effects may cloud findings. Quality improvement initiatives often leverage a number of different study design types, including qualitative assessment and quasi-experimental approaches, including uncontrolled and controlled pre/post intervention testing using time-series and difference-in-difference analysis techniques.

Criteria for Evaluating the Evidence

Once the literature has been systematically searched and relevant studies have been identified, the next step in the CPG development process is to carry out a critical evaluation of the evidence base for each of the linkages specified in the analytic framework. Several organizations, including GRADE, ARHQ, and Cochrane, have developed formal methods to evaluate the evidence base for clinical questions in systematic reviews. These approaches typically assess the strength of the evidence on the basis of (1) the quantity of evidence (e.g., number of studies) and (2) the quality of evidence (e.g., the type of studies and how well the studies were performed). A brief description of the GRADE approach is given below; ARHQ uses the GRADE principles to review evidence. Cochrane is focused on producing systematic reviews only and is not included here; an in-depth description of the Cochrane methodology may be found online. Other approaches to conducting systematic reviews may be found in the 2011 IOM report Finding What Works in Health Care.

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

GRADE is a standardized and systematic approach to grading the quality of evidence (indicating certainty in findings) and the strength of recommendations based on that evidence. GRADE has been adopted by many health care organizations for evaluating evidence and developing CPGs. The GRADE system classifies the quality of evidence into four levels (Schünemann et al., 2013):

- High: Very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect;

- Moderate: Moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different;

- Low: Confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect; and

- Very low: Very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

These classification levels are applied to the body of evidence rather than to individual studies (Balshem et al., 2011). RCTs begin as high-quality evidence but may be rated lower if there are study limitations, inconsistency of results, indirectness of evidence, imprecision, or reporting bias. Observational studies on the other hand, begin with a low quality rating but may be rated upward if the magnitude of the treatment effect is very large, if there is evidence of a dose–response relationship, or if all plausible

biases would decrease the magnitude of an apparent treatment effect (Guyatt et al., 2008a,b). GRADE rates the quality of the body of evidence using the following criteria (Zhang et al., 2019):

- Study limitations

- Publication bias

- Imprecision (random error)

- Inconsistency

- Indirectness

- Rating up the quality of evidence

- Resource use

In the GRADE approach, study limitations that decrease confidence in the findings include a lack of allocation concealment; a lack of blinding; incomplete accounting of patients and outcome events; selective outcome reporting bias; stopping early for benefit; the use of invalidated outcome measures (e.g., patient-reported outcomes); carryover effects in crossover trials; and recruitment bias in cluster-randomized trials (Guyatt et al., 2011).

FROM EVIDENCE TO RECOMMENDATIONS

The goal of the prior steps in the CPG development process (see Figure 4-1) is to identify, gather, review, and grade the evidence on which CPG developers can make recommendations regarding appropriate prescribing strategies to achieve the best health outcomes for the patient and community and to minimize any harms associated with those strategies. The strength of the evidence gathered in the prior step provides the basis for any CPG recommendations.

One approach for moving from the strength of the evidence to recommendations is the methodology developed by GRADE. This methodology addresses factors such as the magnitude of benefits relative to harms, costs, values and preferences, feasibility and implementability, and equity issues, among others (Schünemann et al., 2008). CPG developers can evaluate the evidence for each of the linkages in the analytic framework using the GRADE criteria and evaluate whether a prescribing strategy is associated with benefits (e.g., decreased overdoses) that outweigh harms (e.g., a slight increase in average pain). Assessing the balance of benefits to harms requires a consideration of how health outcomes have been prioritized by the CPG development group during the scoping step. For example, the development group may decide that reducing opioid overdoses and opioid use disorder is a more important health outcome than patients experiencing slight increases in pain. Weighing the findings accordingly, the CPG developers then determine whether to recommend a particular prescribing strategy.

The GRADE methodology determines recommendation strength (strong, weak, or conditional) based on the certainty and balance of an intervention’s desirable effects versus its undesirable effects (Guyatt et al., 2008a). Using the GRADE criteria, strong recommendations are more likely when the following conditions are met:

- The strength of the evidence has been rated as high;

- There is a large benefit from the prescribing strategy relative to potential harms;

- There are lower costs associated with one prescribing strategy compared with another for either the patient or the health system or both;

- It is feasible to implement the strategy;

- The strategy will improve health equity (e.g., better access to care); and

- The strategy is acceptable to patients and their health care providers.

If the evidence does not support the linkages from a prescribing strategy to improved health outcomes (directly or indirectly) then the CPG developers may opt either to not make a recommendation or to make a recommendation but be very explicit about the low quality of the supporting evidence. Often patients and clinicians will accept strong recommendations, whereas the acceptance of weak recommendations will vary according to patients’ and clinicians’ values and preferences. Therefore, when the evidence is low quality but there is little risk of harm and a high likelihood of benefit, a strong recommendation could be formulated based on weak evidence. The GRADE Working Group has identified five specific contexts for such recommendations, three of which are relevant to opioid prescribing (Andrews et al., 2013):

- Low-quality evidence suggests benefit in a life-threatening situation (evidence regarding harms can be low or high).

- High-quality evidence suggests equivalence of two alternatives, and low-quality evidence suggests harm in one alternative.

- High-quality evidence suggests modest benefits, and low- or very low-quality evidence suggests the possibility of catastrophic harm.

The committee notes that for opioid prescribing for acute pain, CPGs are being developed in the context of well-established harms associated with long-term opioid prescribing at the individual patient, community, or population levels and of evidence linking acute prescribing with long-term use. Therefore, opioid prescribing recommendations that have the potential to reduce such harms by decreasing unnecessary opioid use for acute pain may be reasonable even if the evidence showing effects on improved health outcomes is weak. Recommendations supported by low-quality evidence require a clearly articulated rationale, particularly for strong recommendations, and should clearly describe the evidence gaps needed to improve the quality of evidence.

CPG recommendations to clinicians and policy makers will be more acceptable if they are practical, with a focus on relieving patients’ acute pain while minimizing the untoward risks of opioids. Indeed, the risk profile of opioids may justify recommendations to change opioid prescribing patterns based on relatively lower levels of evidence (Ross et al., 2017). Moreover, the potential serious harms that may result from inappropriate opioids prescribing (e.g., misuse, diversion) are challenging to study with RCTs and even observational studies, and may further justify strong recommendations based on weak evidence, if they are determined to have the potential to substantially mitigate such harms (Schünemann et al., 2013; Stancliff et al., 2015).

IMPLEMENTATION

CPG implementation addresses how CPGs relate to different clinical practices and clinical settings, how to increase the dissemination, applicability, and impact of guidelines, and how to evaluate the impact of the guideline on health outcomes. A critical requirement of CPG implementation is continuous quality improvement, including practice audits and feedback (Dulko et al., 2010; Grimshaw et al., 2012; Hysong et al., 2006). As each CPG is disseminated and applied in practice, outcome data need to be gathered at the individual and community levels. Such information can assist guideline developers in revising and updating the CPG when necessary so that it reflects the most current evidence available to ensure that patients with acute pain receive the best care.

Although evidence suggests that CPGs may reduce hospitalization rates, reduce health care costs, and improve clinical outcomes, barriers often exist that limit providers from adopting and implementing them (Kroenke et al., 2019). Guidelines that are overly complex or require a significant change in

practice or resources are less likely to be implemented. An organizational structure that allows for access to high-quality CPGs, strategies for decision making, and collecting outcome data may help overcome challenges to the implementation of guidelines.

After recommendations for opioid prescribing strategies have been developed and approved, consideration needs to be given to ensuring effective dissemination, uptake, and periodic revisions of the CPG. As discussed in the 2011 IOM report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, these activities are part of the implementation process. Many organizations that develop CPGs already have mechanisms in place to disseminate them to appropriate audiences. For example, members of medical specialty societies may learn about a new CPG or changes to an existing CPG through annual or regional meetings, continuing medical education activities, or educational materials from state medical boards. Other dissemination activities may also be used to encourage clinician knowledge of CPGs. Meisel et al. (2016) found that ED physicians who read narrative vignettes that referenced opioid prescription dilemmas published in the daily electronic newsletter of the American College of Emergency Physicians were significantly more likely to read additional information in the newsletter links than were physicians who accessed newsletters that contained traditional summary text.

Some CPGs include recommendations on implementation and how they might best be incorporated into clinical practice. Implementation of opioid prescribing strategies may include components such as EHR standing orders, provider education, and pharmacy reviews. For example, a recent CPG for acute pain management after musculoskeletal injury includes best practice recommendations for health care systems that include supporting opioid education efforts for prescribers and patients and the use of clinical decision support for opioid prescribing in the EHR (Hsu et al., 2019). That CPGs are not necessarily used for clinical decision making was demonstrated by Kilaru et al. (2014), who found that among 61 ED physicians, hospital-based guidelines were primarily used to communicate decisions to limit discharge prescriptions to patients rather than as decision-making tools. Overcoming this lack of clinician uptake may include both provider and patient education efforts. Kaafarani et al. (2019) found that a hospital-based, multidisciplinary pain management intervention to reduce postoperative opioid prescribing was effective in reducing both discharge prescribing as well as refill requests and sex and race prescription disparities. The intervention consisted of consensus-built opioid prescribing guidelines for 42 surgical procedures from 11 specialties, provider-focused posters displayed in all surgical units, patient opioid/pain brochures to set patient outcome expectations, and educational seminars to residents, advanced practice providers, and registered nurses.

Similarly, other CPG developers address strategies to enhance patient engagement, such as patient education and counseling, and to promote patient adherence to and acceptance of the clinical care protocols outlined in the CPG (Engelman et al., 2019). Patient education may include information on the risks and benefits of opioid use, including drug interactions, and what to do should adverse effects occur. Both clinicians and other trained health care providers (e.g., nurses, pharmacists, social workers) can educate patients on the appropriate use and disposal of opioids, and who to contact in the event of adverse effects.

Tools, checklists, applications, algorithms, and pocket guides have been successfully used to increase guideline uptake by clinicians (CDC, 2017). For example, one medical center found that mandatory prescriber training and standardized patient instruction materials along with the availability of evidence-based CPGs significantly reduced opioid prescribing for patients undergoing breast and melanoma surgical procedures (Lee et al., 2019).

States also have mechanisms to encourage clinicians to use opioid prescribing guidelines. Health care providers who are identified as high prescribers on the basis of state prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) may be notified that they are exceeding the guidelines or regulatory limits, alerting

them to reconsider their prescribing patterns (e.g., the State of Illinois Opioid Action Plan, 2018). Moreover, PDMP data can be used to track the impact of these statewide programs on opioid prescribing practices (Deyo et al., 2018).

The use of CPGs in clinical care requires further study, but some reviews have suggested that “multifaceted educational knowledge translation interventions” are effective for improving the use of guidelines by health care professionals (Al Zoubi et al., 2018). The committee emphasizes that without practical approaches to implement guideline recommendations, the impact of evidence-based CPGs will be less than optimal. Such activities can be incorporated into a continuous quality improvement approach for implementation. Other factors that may affect how guidelines are implemented include urban versus rural setting, health care setting (e.g., large or small hospitals, single clinician clinics), the social determinants of health (e.g., access, bias, stress, marginalized groups), opportunity for continuity in patient care, the presence of a definitive diagnosis, and multiple clinicians (e.g., transitioning from surgeon-directed, postoperative pain control to primary care provider postoperative pain control) (Haller and Acosta, 2010; IOM, 2011a; Klueh et al., 2018; Meghani et al., 2012; Sadhasivam et al., 2012). For example, Hill et al. (2018) developed a guideline for opioid prescribing based on the number of opioids used by the patient the day before discharge. Hill et al. (2018) noted that the guideline had a benefit over state-mandated prescribing practices because prescribing was determined with the patient using a shared decision-making model (Osmundson et al., 2018).

Critical to the dissemination and uptake of CPGs is the integration of new and emerging technologies (e.g., telemedicine, e-prescribing, phone or email follow-up) to improve the implementation and monitoring of CPGs. EHRs may be a valuable resource for identifying overprescribing as well as identifying data sources that can be used to establish baseline or default prescribing doses or trends in opioid prescribing (Garcia et al., 2019; Suffoletto et al., 2018). Such records can be modified to capture specific intermediate and health outcomes and to document confounders that may be used in future observational studies. As EHRs are able to incorporate more discrete data, subsequent cohort research can incorporate such data to more accurately address potential confounding factors (e.g., health literacy). Such defaults may require the clinician to justify prescribing opioids in excess of the default amount.

As guidelines are implemented, the appropriate monitoring of patient and populations health outcomes is important to ensure that the changes in clinical practice as a result of the guideline are effective. This monitoring may include identifying such things as unresolved pain, lack of functional benefits, a continued need for opioids, conversion to chronic pain, opioid misuse, opioid diversion, and opioid-related adverse events including serious adverse events (e.g., fatal and nonfatal overdose, central nervous system depression, and respiratory depression).

Inherent in the development of a CPG is the need to periodically update and revise the CPG as new evidence becomes available through a defined process of periodic review and updating (orange arrow in Figure 4-1). This process might also include a need to revise either the CPG or the implementation process in light of both intended and unintended consequences or information that suggests the CPG is not effective in improving intermediate or health outcomes (Dowell et al., 2019; Kroenke et al., 2019). As stated in the 2011 IOM report:

CPGs should be updated when new evidence suggests the need for modification of clinically important recommendations. For example, a CPG should be updated if new evidence shows that a recommended intervention causes previously unknown substantial harm; that a new intervention is significantly superior to a previously recommended intervention from an efficacy or harms perspective; or that a recommendation can be applied to new populations. (p. 137)

Monitoring the effectiveness of a CPG for improving opioid prescribing practices may include encouraging, mandating, or expanding access to PDMPs and educating prescription benefits managers (Alexander et al., 2015). The committee cautions, however, that such monitoring may indicate that recommended strategies are having unintended effects. For example, in one case the mandated use of a PDMP did not the reduce the number of opioid pills prescribed to patients following surgery or the number of patients who received opioids in the 6 months after the program was initiated compared with rates prior to initiation of the program nor did the program identify at-risk patients who should not receive opioids (Stucke et al., 2018). Guidelines also create the possibility of unintended consequences, such as a health insurance company placing restrictions on opioid prescribing regardless of individual patients’ needs (Dowell et al., 2019).

Therefore, CPGs should formalize a plan to track how they are being used in order to assess (1) the desired direct effects, (2) undesired direct effects (e.g., greater frequency of uncontrolled pain), (3) desired indirect effects, and (4) undesired indirect effects (e.g., increased use of illicit opioid substances). Guideline developers should consider addressing risk mitigation strategies (e.g., education, opioid disposal, monitoring) as part of developing a comprehensive care plan to address these concerns and to identify others (e.g., PDMPs, concurrent opioid therapy, concurrent benzodiazepine therapy, multiple prescribers or “doctor shopping”).

As pain and opioid-related CPGs are published, it will be important to evaluate the methodological rigor of the guidelines using instruments such as AGREE II, to assess the consistency of recommendations, and to determine best practices to promote the uptake of CPGs. These evaluations will also be useful to help CPG developers align their work with other high-quality CPGs and address shortcomings of existing ones (Al Zoubi et al., 2018; Durán-Crane et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2014).

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2015. Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/cer-methods-guide/overview (accessed May 30, 2019).

Al Zoubi, F.M., A. Menon, N.E. Mayo, and A.E. Bussières. 2018. The effectiveness of interventions designed to increase the uptake of clinical practice guidelines and best practices among musculoskeletal professionals: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research 18(1):435.

Alexander, G., S. Frattaroli, and A. Gielen. 2015. The prescription opioid epidemic: An evidence-based approach. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/center-for-drug-safety-and-effectiveness/research/prescription-opioids/JHSPH_OPIOID_EPIDEMIC_REPORT.pdf (accessed August 26, 2019).

Andrews, J.C., H.J. Schünemann, A.D. Oxman, K. Pottie, J.J. Meerpohl, P.A. Coello, D. Rind, V.M. Montori, J.P. Brito, S. Norris, M. Elbarbary, P. Post, M. Nasser, V. Shukla, R. Jaeschke, J. Brozek, B. Djulbegovic, and G. Guyatt. 2013. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—Determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 66(7):726–735.

Anglemyer, A., H.T. Horvath, and L. Bero. 2014. Healthcare outcomes assessed with observational study designs compared with those assessed in randomized trials. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4):Mr000034.

Babu, K.M., J. Brent, and D.N. Juurlink. 2019. Prevention of opioid overdose. New England Journal of Medicine 380(23):2246–2255.

Badreldin, N., W.A. Grobman, K.T. Chang, and L.M. Yee. 2018. Opioid prescribing patterns among 467 postpartum women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 219(1):e101–e103.

Balshem, H., M. Helfand, H.J. Schünemann, A.D. Oxman, R. Kunz, J. Brozek, G.E. Vist, Y. Falck-Ytter, J. Meerpohl, S. Norris, and G.H. Guyatt. 2011. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64(4):401–406.

Benyamin, R., A.M. Trescott, S. Datta, R. Buenaventura, R. Adlaka, N. Sehgal, S.E. Glaser, and R. Vallejo. 2008. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 11(2 Suppl):S105–S120.

Bicket, M.C., E. White, P.J. Pronovost, C.L. Wu, M. Yaster, and G.C. Alexander. 2019. Opioid oversupply after joint and spine surgery: A prospective cohort study. Anesthesia & Analgesia 128(2):358–364.

Bohnert, A.S.B., M. Valenstein, M.J. Bair, D. Ganoczy, J.F. McCarthy, M.A. Ilgen, and F.C. Blow. 2011. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA 305(13):1315–1321.

Brat, G.A., D. Agniel, A. Beam, B. Yorkgitis, M. Bicket, M. Homer, K.P. Fox, D.B. Knecht, C.N. McMahill-Walraven, N. Palmer, and I. Kohane. 2018. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naïve patients and association with overdose and misuse: Retrospective cohort study. British Medical Journal 360:j5790.

Brouwers, M.C., M.E. Kho, G.P. Browman, J.S. Burgers, F. Cluzeau, G. Feder, B. Fervers, I.D. Graham, J. Grimshaw, S.E. Hanna, P. Littlejohns, J. Makarski, and L. Zitzelsberger. 2010. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal 182(18):E839.

Brummett, C.M., J.F. Waljee, J. Goesling, S. Moser, P. Lin, M.J. Englesbe, A.S.B. Bohnert, S. Kheterpal, and B.K. Nallamothu. 2017. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in U.S. adults. JAMA Surgery 152(6):e170504.

Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. 1988. The periodic health examination: 2. 1987 update. Canadian Medical Association Journal 138(7):618–626.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2017. Guideline resources. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/resources.html (accessed May 30, 2019).

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2009. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine—Levels of evidence (March 2009). http://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009 (accessed September 6, 2019).

Chassin, M.R., and J.M. Loeb. 2011. The ongoing quality improvement journey: Next stop, high reliability. Health Affairs 30(4):559–568.

Chou, R., D.B. Gordon, O.A. de Leon-Casasola, J.M. Rosenberg, S. Bickler, T. Brennan, T. Carter, C.L. Cassidy, E.H. Chittenden, E. Degenhardt, S. Griffith, R. Manworren, B. McCarberg, R. Montgomery, J. Murphy, M.F. Perkal, S. Suresh, K. Sluka, S. Strassels, R. Thirlby, E. Viscusi, G.A. Walco, L. Warner, S.J. Weisman, and C.L. Wu. 2016. Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ committee on regional anesthesia, executive committee, and administrative council. The Journal of Pain 17(2):131–157.

Corrigan-Curay, J., L. Sacks, and J. Woodstock. 2018. Real-world evidence and real-world data for evaluating drug safety and effectiveness. JAMA 320(9):867–868.

Daniels, S.E., M.A. Goulder, S. Aspley, and S. Reader. 2011. A randomised, five-parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial comparing the efficacy and tolerability of analgesic combinations including a novel single-tablet combination of ibuprofen/paracetamol for postoperative dental pain. Pain 152(3):632–642.

Delgado, M.K., F.S. Shofer, M.S. Patel, S. Halpern, C. Edwards, Z.F. Meisel, and J. Perrone. 2018. Association between electronic medical record implementation of default opioid prescription quantities and prescribing behavior in two emergency departments. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(4):409–411.

Deschamps, J., J. Gilbertson, S. Straube, K. Dong, F.P. MacMaster, C. Korownyk, L. Montgomery, R. Mahaffey, J. Downar, H. Clarke, J. Muscedere, K. Rittenbach, R. Featherstone, M. Sebastianski, B. Vandermeer, D. Lynam, R. Magnussen, S.M. Bagshaw, and O.G. Rewa. 2019. Association between harm reduction strategies and healthcare utilization in patients on long-term prescribed opioid therapy presenting to acute healthcare settings: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews 8(1):88.

Deyo, R.A., S.E. Hallvik, C. Hildebran, M. Marino, E. Dexter, J.M. Irvine, N. O’Kane, J. Van Otterloo, D.A. Wright, G. Leichtling, and L.M. Millet. 2017. Association between initial opioid prescribing patterns and subsequent long-term use among opioid-naïve patients: A statewide retrospective cohort study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 32(1):21–27.

Deyo, R.A., S.E. Hallvik, C. Hildebran, M. Marino, R. Springer, J.M. Irvine, N. O’Kane, J. Van Otterloo, D.A. Wright, G. Leichtling, L.M. Millet, J. Carson, W. Wakeland, and D. McCarty. 2018. Association of prescription drug monitoring program use with opioid prescribing and health outcomes: A comparison of program users and nonusers. The Journal of Pain 19(2):166–177.

Dowell, D., T. Haegerich, and R. Chou. 2019. No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing. New England Journal of Medicine 380(24):2285–2287.

Dulko, D., E. Hertz, J. Julien, S. Beck, and K. Mooney. 2010. Implementation of cancer pain guidelines by acute care nurse practitioners using an audit and feedback strategy. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 22(1):45–55.

Durán-Crane, A., A. Laserna, M.A. López-Olivo, J.A. Cuenca, D. Paola Díaz, Y. Rocío Cardenas, C. Urso, K. O’Connell, K. Azimpoor, C. Fowler, K.J. Price, C.L. Sprung, and J.L. Nates. 2019. Clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements about pain management in critically ill end-of-life patients: A systematic review. Critial Care Medicine 47(11):1619–1626.

Engelman, D.T., W. Ben Ali, J.B. Williams, L.P. Perrault, V.S. Reddy, R.C. Arora, E.E. Roselli, A. Khoynezhad, M. Gerdisch, J.H. Levy, K. Lobdell, N. Fletcher, M. Kirsch, G. Nelson, R.M. Engelman, A.J. Gregory, and E.M. Boyle. 2019. Guidelines for perioperative care in cardiac surgery: Enhanced recovery after surgery society recommendations. JAMA Surgery 154(8):755–766.

Ferreira, P.H., M.L. Ferreira, C.G. Maher, K. Refshauge, R.D. Herbert, and J. Latimer. 2002. Effect of applying different “levels of evidence” criteria on conclusions of Cochrane reviews of interventions for low back pain. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 55(11):1126–1129.

Friedman, B.W., A.A. Dym, M. Davitt, L. Holden, C. Solorzano, D. Esses, P.E. Bijur, and E.J. Gallagher. 2015. Naproxen with cyclobenzaprine, oxycodone/acetaminophen, or placebo for treating acute low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314(15):1572–1580.

García, M.C., C.M. Heilig, S.H. Lee, M. Faul, G. Guy, M.F. Iademarco, K. Hempstead, D. Raymond, and J. Gray. 2019. Opioid prescribing rates in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties among primary care providers using an electronic health record system—United States, 2014–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 68(2):25–30.

Gordon, D.B., O.A. de Leon-Casasola, C.L. Wu, K.A. Sluka, T.J. Brennan, and R. Chou. 2016. Research gaps in practice guidelines for acute postoperative pain management in adults: Findings from a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Pain 17(2):158–166.

Gordon, H.W. 2019. Differential effects of addictive drugs on sleep and sleep stages. Journal of Addiction Research 3(2):10.33140/JAR.03.02.01.

Grimshaw, J.M., M.P. Eccles, J.N. Lavis, S.J. Hill, and J.E. Squires. 2012. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implementation Science 7:50.

Gross, J., and D.B. Gordon. 2019. The strengths and weaknesses of current U.S. policy to address pain. American Journal of Public Health 109(1):e1–e7.

Guirguis-Blake, J., N. Calonge, T. Miller, A. Siu, S. Teutsch, and E. Whitlock. 2007. Current processes of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Refining evidence-based recommendation development. Annals of Internal Medicine 147(2):117–122.

Guyatt, G.H., A.D. Oxman, R. Kunz, Y. Falck-Ytter, G.E. Vist, A. Liberati, H.J. Schünemann, and G.W. Group. 2008a. Going from evidence to recommendations. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Education) 336(7652):1049–1051.

Guyatt, G.H., A.D. Oxman, G.E. Vist, R. Kunz, Y. Falck-Ytter, P. Alonso-Coello, and H.J. Schünemann. 2008b. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. British Medical Journal 336(7650):924–926.

Guyatt, G.H., A.D. Oxman, G. Vist, R. Kunz, J. Brozek, P. Alonso-Coello, V. Montori, E.A. Akl, B. Djulbegovic, Y. Falck-Ytter, S.L. Norris, J.W. Williams, D. Atkins, J. Meerpohl, and H.J. Schünemann. 2011. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—Study limitations (risk of bias). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64(4):407–415.

Haller, D.L., and M.C. Acosta. 2010. Characteristics of pain patients with opioid-use disorder. Psychosomatics 51(3):257–266.

Han, B., W.M. Compton, C. Blanco, E. Crane, J. Lee, and C.M. Jones. 2017. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. adults: 2015 national survey on drug use and health. Annals of Internal Medicine 167(5):293–301.

Hannan, E.L. 2008. Randomized clinical trials and observational studies: Guidelines for assessing respective strengths and limitations. Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Interventions 1(3):211–217.

Harris, R.P., M. Helfand, S.H. Woolf, K.N. Lohr, C.D. Mulrow, S.M. Teutsch, and D. Atkins. 2001. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: A review of the process. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 20(3, Suppl 1):21–35.

Higgins, J., J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M.J. Page, and V.A. Welch. 2019. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.0. http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed August 28, 2019).

Hill, M.V., R.S. Stucke, S.E. Billmeier, J.L. Kelly, and R.J. Barth. 2018. Guideline for discharge opioid prescriptions after inpatient general surgical procedures. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 226(6):996–1003.

Hsu, J.R., H. Mir, M.K. Wally, R.B. Seymour, and the Orthopaedic Trauma Association Musculoskeletal Pain Task Force. 2019. Clinical practice guidelines for pain management in acute musculoskeletal injury. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 33:e158–e182.

Hysong, S.J., R.G. Best, and J.A. Pugh. 2006. Audit and feedback and clinical practice guideline adherence: Making feedback actionable. Implementation Science 1:9.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1992. Guidelines for clinical practice: From development to use. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2011a. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011b. Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Itri, J.N., E. Bakow, L. Probyn, N. Kadom, P.-A.T. Duong, L. Mankowski Gettle, M. Mendiratta-Lala, E.P. Scali, R.S. Winokur, M.E. Zygmont, J.W. Kung, and A.B. Rosenkrantz. 2017. The science of quality improvement. Academic Radiology 24(3):253–262.

Kaafarani, H.M.A., A.I. Eid, D.M. Antonelli, D.C. Chang, A.E. Elsharkawy, J.A. Elahad, E.A. Lancaster, J.T. Schylz, S.I. Melnitchouk, W.V., Kastrinakis, M.M. Hutter, P.T. Masiakos, A.S. Colwell, C.D. Wright, and K.D. Lillemoe. 2019. Description and impact of a comprehensive multispecialty multidisciplimary intervention to decrease opioid prescribing in surgery. Annals of Surgery 270(3):452–462.

Kilaru, A.S., S.M. Gadsden, J. Perrone, B. Paciotti, F.K. Barg, and Z.F. Meisel. 2014. How do physicians adopt and appply opioid prescription guidelines in the emergency department? A qualitative study. Annals of Emergency Medicine 64(5):482–489.

Klueh, M.P., H.M. Hu, R.A. Howard, J.V. Vu, C.M. Harbaugh, P.A. Lagisetty, C.M. Brummett, M.J. Englesbe, J.F. Waljee, and J.S. Lee. 2018. Transitions of care for postoperative opioid prescribing in previously opioid-naïve patients in the USA: A retrospective review. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(10):1685–1691.

Kroenke, K., D.P. Alford, C. Argoff, B. Canlas, E. Covington, J.W. Frank, K.J. Haake, S. Hanling, W.M. Hooten, S.G. Kertesz, R.L. Kravitz, E.E. Krebs, S.P. Stanos, Jr., and M. Sullivan. 2019. Challenges with implementing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention opioid guideline: A consensus panel report. Pain Medicine 20(4):724–735.

Kumar, K., M.A. Kirksey, S. Duong, and C.L. Wu. 2017. A review of opioid-sparing modalities in perioperative pain management: Methods to decrease opioid use postoperatively. Anesthesia & Analgesia 125(5):1749–1760.

Larach, D.B., J.F. Waljee, H.-M. Hu, J.S. Lee, R. Nalliah, M.J. Englesbe, and C.M. Brummett. 2018. Patterns of initial opioid prescribing to opioid-naïve patients. Annals of Surgery. July 24. [Epub ahead of print].

Lee, G.Y., J. Yamada, O. Kyololo, A. Shorkey, and B. Stevens. 2014. Pediatric clinical practice guidelines for acute procedural pain: A systematic review. Pediatrics 133(3):500–515.