5

Mentorship Behaviors and Education:

How Can Effective Mentorship Develop?

Mentorship is a learned activity, and developing effective mentoring relationships depends on mentors and mentees engaging in specific behaviors. This chapter discusses current knowledge about mentor and mentee behaviors that have some evidence of effectiveness. It also discusses the importance of mentor and mentee education as a means of inculcating effective mentor and mentee behaviors. Box 5-1 highlights how theory may inform the concepts that are discussed.

EFFECTIVE MENTORSHIP BEHAVIORS

As discussed in Chapter 4, mentoring relationships occur in many forms. A growing body of evidence suggests that regardless of the configuration of mentorship, effective mentoring relationships are characterized by trust, responsiveness, and career and psychosocial support.

One set of desired mentor behaviors is outlined in the Entering Mentoring curriculum, now in its second edition (see Box 5-2) (Handelsman et al., 2005; Pfund et al., 2006, 2015). Although this curriculum focuses primarily on mentorship in research training environments, the stated aim—to help mentors at all stages in developing and refining their mentorship abilities—serves as a basis for mentoring relationships more broadly.1 The committee could not find any systematic investigation of how particular mentoring

___________________

1 The Entering Mentoring curriculum is discussed later in this chapter.

behaviors included in Entering Mentoring relate to mentee perceptions of psychosocial and career support or particular mentee outcomes.2

In the ideal situation, regardless of the configuration of a mentoring relationship, mentors and mentees will work together to define the knowledge, skills, abilities, and

___________________

2 The Entering Mentoring curriculum has been adapted to suit different disciplines and career stages of the mentee.

outcomes each person expects at the beginning of the relationship (Arthur et al., 2003).3 These conversations involve mentors and mentees engaging in self-assessment and self-reflection. In other words, significant discussions are vital for successful initiation of mentorship.

A personalized mentoring relationship—one responsive to the needs, goals, interests, and priorities of both the mentor and the mentee—is likely to be more effective than one that is not personalized.4 Often, this is what distinguishes a mentoring relationship from a transactional or advising relationship (Baker and Griffin, 2010; Kirchmeyer, 2005; Montgomery, 2017; Montgomery et al., 2014; Ramirez, 2012).5 A successful transactional relationship is determined by institutionally defined measures of success, such as completion of a program or degree, and there is often a fixed term for the transaction. This type of transactional interaction may not necessarily have the interpersonal elements that can transform such important interactions into mentoring relationships.

The scope of traditional mentoring relationship hierarchies has focused less on the needs of the mentor, yet operating on the assumption that the mentee is the only one who benefits limits our understanding of the full value of mentorship. Rather, there are bidirectional, and sometimes unexpected, benefits to mentors that are both instrumental—a means to an end—and intrinsic—having value in and of itself (Dolan and Johnson, 2009; Hayward et al., 2017; Lechuga, 2011; Limeri et al., 2019; Varkey et al., 2012).6 Studies of mentors show that they report learning new knowledge, skills, dispositions, and perspectives from their mentees (Dolan and Johnson, 2009; Hayward et al., 2017; Laursen et al., 2010; Limeri et al., 2019; Thiry and Laursen, 2011). Mentors also report that the satisfaction and enjoyment gained from working with mentees improves their professional life and helps build future generations of science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) professionals (Bozionelos, 2004; Dolan and Johnson, 2009; Hayward et al., 2017; Limeri et al., 2019).

Balancing Trust and Privacy

Effective mentoring relationships are built on active bilateral trust, as well as on mutual accountability and responsibility (Greco, 2014; Hund et al., 2018; Johnson-Bailey and Cervero, 2004; McGee et al., 2015; Montgomery, 2017). Mentorship that aligns with institutionally defined paths to success often grants those in the mentor role with an implied trust by virtue of their having attained a certain level of success in that career path. However, this assertion can contribute to or exacerbate differentials in power

___________________

3 The beginning of the relationship is referred to as the initiation stage in Chapter 1.

4 This type of personalization is also implied in the discussions about identity in Chapter 3.

5 An example of a transactional relationship is one comprising a graduate student, a research advisor, and a dissertation committee that only functions to meet graduate program requirements and ends upon student graduation.

6 The motivations and experiences of mentors are discussed more in Chapter 6.

between the mentor and mentee. Neither the mentor nor mentee role should dictate whether someone is trusted or not—each participant should be able to assume that some level of trust is present when entering into a mentoring relationship and expect that trust will be actively cultivated and will not be violated.

Mentoring behaviors that build trust are likely to be responsive to a range of characteristics of the mentee. For example, if the mentee is a member of an underrepresented (UR) population in STEMM,7 the mentor(s) may encourage and support attendance at affinity-based conferences and workshops. As the committee heard during their listening sessions, this type of personalization or responsiveness recognizes aspects of identity that are valued by mentees and that will contribute to a stronger STEMM identity.

In mentorship, like in all interpersonal relationships, self-disclosure can help to build a trusting, responsive relationship (Wanberg et al., 2007). However, mentors must be respectful of mentees’ right to choose not to disclose personal information. Mentees have the right to privacy (i.e., the choice not to disclose personal information, such as gender, race, or religion, as stipulated in Title IX federal law8) and mentees have the right to confidentiality (i.e., if they disclose information to mentors, mentors are obligated to keep this information in confidence). The power difference in mentor-mentee relationships can be coercive to mentees, making them feel obligated to disclose personal information that they have the right to keep private.

Many formal mentoring relationships in STEMM involve a mentor who is also a research advisor or supervisor responsible for making evaluative judgments about their mentee’s progress and performance.9 Research from workplace settings indicates that, because supervisors and employees are part of different social groups, complete trust may not be possible but certain communication characteristics can help to promote trust (Wanberg et al., 2007; Willemyns et al., 2003).

Mentorship education can help mentors learn about and practice strategies for establishing good relationships, aligning expectations, and communicating effectively with mentees, all of which may help to build a trusting, reciprocal relationship (Pfund et al., 2015). For example, mentors’ provision of psychosocial support, such as telling personally relatable stories of when they have faced professional struggles or experienced professional failures, may help to create a safe space for mentee self-disclosure without crossing professional boundaries or compromising mentees’ right to privacy.

___________________

7 This report refers to UR groups as including women of all racial/ethnic groups and individuals specifically identifying as Black, Latinx, and American Indian/Alaska Native. Where possible, the report specifies if the UR groups to which the text refers are Black, Latinx, or of American Indian/Alaska Native heritage.

8 Pub. L. No. 92-318, 86 Stat. 235 (1972), available at https://www.justice.gov/crt/title-ix-education-amendments-1972; accessed September 20, 2019.

9 Formal mentoring structures and research mentorship are discussed in the “Formal versus Informal Mentorship” section of Chapter 4.

Mentors can consult campus offices of diversity, equity, and inclusion for professional development and advice on balancing trust building while maintaining professional boundaries. Mentors can also consult campus compliance offices to understand the laws regarding privacy and confidentiality as well as requirements to report misconduct, including discrimination, harassment, and retaliation.

Overcoming Limitations in Mentorship

Mentorship is not without costs. For instance, mentors of undergraduate researchers have reported both improved and compromised research productivity and both positive and negative emotions resulting from their work with mentees (Hayward et al., 2017; Limeri et al., 2019). Investigators have found that benefits of mentorship are directly related to the mentor’s skills, aptitude, and motivation (Rogers et al., 2016), providing further support for mentor professional development (Butz et al., 2018a). Moreover, the limitations and boundaries of the traditional hierarchies of research mentorship have recently been reexamined, leading them to be reframed into a mutually constructed relationship between mentor and mentees. Approaches such as “mentoring up” address this reframing. The idea behind mentoring up is to give mentees the skills, confidence, and responsibility to be active and equal participants in their mentoring relationships (Lee et al., 2015). When combined, the concepts underlying the Entering Mentoring and Entering Research (see below) programs can serve as a foundation upon which to build successful and enduring mentoring relationships. The mentoring up approach is generally well received by both mentors and mentees, with mentees reporting they learned skills to maximize their own relationships as mentee and mentor (Lee et al., 2015).

MENTORSHIP TOOLS

Although this has not been the subject of direct investigation, the mentorship behaviors reported here (see Box 5-2) are likely to be effective because they foster the defining features of an effective mentoring relationship: trust and responsiveness coupled with provision of career and psychosocial support through a working alliance. For example, aligning expectations provides a common basis from which a mentoring relationship can develop (Brace et al., 2018; Cunningham, 1993; Grant, 2015; Washington and Cox, 2016).

Research has shown that mentors alone cannot be the sole determinants of expectations (Byars-Winston et al., 2015; Grant, 2015; Greco, 2014; Montgomery, 2017; Washington and Cox, 2016). Rather, expectations should be responsive to the individuals involved in the mentoring relationship, as well as to particular contexts in which the relationships occur, such as how individuals, circumstances, and environments change over time. Regardless of the approach to mentorship, both mentors and mentees should have the space to communicate expectations and request accountability, a space that entering into a mentorship compact can provide. To facilitate these behaviors, some

mentors rely on dedicated tools. Here, the committee provides a summary of four such tools: individual development plans (IDPs), mentorship compacts, mentorship maps, and mentoring plans.10

Individual Development Plans

The IDP is a tool for providing structure to mentors and mentees in their work together (Vincent et al., 2015). Developing IDPs requires that mentees think through their short- and long-term career plans and formulate a path to enact the plans with support from their mentor. IDPs provide a mechanism for supporting effective mentorship behaviors in a manner tailored and responsive to mentees’ career plans as well as their unique skills, interests, and values (Hobin et al., 2014). The use of IDPs supports structured bilateral engagement and personalization in the mentorship exchange (Hobin et al., 2014; Vincent et al., 2015). Assessments of IDPs indicate they are useful in facilitating skills identification and developing the abilities needed to support career success (Hobin et al., 2014). Given that the use of IDPs is correlated with greater reports of satisfaction and scientific productivity on the part of postdoctoral scientists (Davis, 2009), their expanded use in training programs is expected to benefit a broad range of student scientists (Fuhrmann, 2016).

Mentorship Compacts

Communication of expectations may occur when mentees and mentors begin their relationships through the use of a mentorship compacts. These written agreements provide a structure for mentors to outline expectations from, and commitments to, mentees, and vice versa.11 Compacts differ from an IDP, which focuses on short- and long-term career plans, as they are focused on expectations for the working relationship on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis. More often than not, the explicit conversations between mentors and mentees about these expectations for the working alliance do not occur or only occur at the start of the relationship, and there is little if any external check that expectations are reasonable. Mentoring compacts can prompt more structured and regular discussions of expectations, making expectations explicit. Written compacts can also ensure that all mentees, regardless of their prior experience and socialization to STEMM, have equal access to information regarding expectations.

___________________

10 As discussed in Chapter 1, this is an example of where wide practice provides evidence of possible merit in using such tools to support effective mentorship. In addition, this section is informed by the committee’s listening sessions. Examples of mentoring tools are available on the Online Guide at https://www.nationalacademies.org/MentorshipinSTEMM.

11 Sample mentorship compacts are available to download at https://ictr.wisc.edu/mentoring/mentoringcompactscontracts-examples/; accessed September 19, 2019.

Mentoring compacts are usually distinct from the more strictly contractual agreements that are sometimes utilized in laboratory-based training environments.12 Rather, the term compact connotes something both mutual and aspirational. Indeed, examples of mentoring compacts often invoke inspirational language about “promises” that mentors make to mentees, and vice versa, and those promises can be attached to principles (e.g., loyalty, availability) as opposed to deliverables (e.g., publications, research, or career milestones). As such, the value of mentoring compacts is not necessarily connected to specific terms and conditions or consequences for breach of contract. Rather, as with many commitments people voluntarily make, much of the value arises from declaratively communicating to the other party a serious commitment and set of intentions in support of the success of the mentoring relationship, the parameters and boundaries of those commitments, and a mutual understanding of success in the context of the relationship. The compact can also serve as a positive corrective resource—an objective reminder to the parties of what they had intended to deliver to one another—if failures to hold to the agreements occur. If necessary, such a document can be helpful for an ombudsperson who may become involved in helping to mediate or repair a mentoring relationship.

Mentoring Maps

Mentoring maps are versatile tools designed to help an individual identify academic and career goals, sources of support to reach those goals, and areas where unmet needs could benefit from forming new mentoring relationships as part of a mentorship network (Montgomery, 2017).13 The mapping process uses pointed questions rooted in mentorship to drive a personal mentoring needs assessment and a mentoring network–mapping exercise.

Mentoring Plans

Mentoring plans refer to several different tools that can facilitate the roles, responsibilities, and approaches of mentors and mentees. Some people refer to mentoring compacts (see above) as mentoring plans, since they provide a structure for mentors to outline expectations for their work and their relationship. Others describe mentor-

___________________

12 For example, some labs involved in classified or proprietary research may have strict requirements and consequences regarding protocols for secure handling of materials and documents.

13 Some mentoring networks exist that offer useful resources, though at a cost to the individual or their institution. For example, the National Center for Faculty Development & Diversity (https://www.facultydiversity.org/; accessed August 17, 2019) has developed a mentoring network map, which invites new faculty to consider the many different people who can provide support and advice in different areas. This map could be adapted for use with graduate students and undergraduates. In addition, there are free groups that operate in social media or other forums, such as #WomeninMedicine, #DiverseDoubleDocs, #BLACKinSTEM, and VanguardSTEM (https://www.vanguardstem.com/; accessed August 17, 2019), among others.

ing plans as written documents that include both a mentoring philosophy and specific examples of how that philosophy is enacted in their mentoring practices. Mentoring plans can also outline a mentor’s plan of action for assessing their mentoring skills, behaviors, and approaches and detail their plans for advancement by identifying areas of need.14 The National Science Foundation (NSF) requires mentoring plans specifically in reference to training and mentoring of funded postdoctoral researchers;15 these plans can include all of the elements above or a selection of them.

It is important to note that any tool is only as effective as the care with which it is implemented; simply using a tool does not guarantee its success. For example, built into the IDP tool is the expectation of a process whereby mentors and mentees regularly check on progress toward the objectives and milestones laid out with the tool. Similarly, mentoring compacts imply a working agreement about engagement in the mentoring relationship, and it is therefore beneficial to agree explicitly on how to handle any failure to meet expectations by either party. While these tools are intended to be helpful for structuring what should be a positive and mutually beneficial relationship, they can be undermined if the tools are used as blunt instruments of enforcement or of regulatory compliance. However, it is reasonable for mentors and mentees using these tools to agree that the relationship itself is conditioned upon mutual commitment to the objectives and milestones laid out. Mentors and mentees may want to seek out alternative mentoring relationships when there is a breakdown in the ability to follow through on commitments, and these tools can serve as helpful warning indicators of such situations. Ultimately, clarity, follow-up, and open communication are keys to helping ensure successful implementation of these tools.

NEGATIVE MENTORING EXPERIENCES

While there is an understandable focus on effective and positive mentoring relationships, programs, and behaviors, mentorship scholars acknowledge that mentorship quality exists on a continuum (Ragins et al., 2000). Mentorship can include dysfunctional elements or problematic events that are collectively referred to as “negative mentoring experiences” (Eby et al., 2000; Kram, 1985a; Scandura, 1998; Simon and Eby, 2003). Negative mentoring experiences can refer to problematic aspects of an otherwise positive relationship and do not necessarily mean that the entire relationship is negative or harmful (Kram, 1985a; Scandura, 1998; Simon and Eby, 2003). Examining negative mentoring experiences can help mentors and mentees address and avoid harmful mentoring behaviors.

While a dearth of research studies that directly examine negative mentoring experiences of undergraduate and graduate students in STEMM exists, several recent reports

___________________

14 Mentoring plans of this type can be found in the Entering Mentoring curriculum.

15 For more information about the NSF Postdoctoral Researcher Mentoring Plan, see https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/policydocs/pappguide/nsf09_29/gpg_2.jsp#IIC2j; accessed May 3, 2019.

examine related issues. Graduate STEM Education for the 21st Century highlights the growing body of research showing that today’s graduate students are more stressed and experience different stressors than previous generations of graduate students, which can compromise their physical, mental, and emotional well-being (NASEM, 2018a).16 The power differential between graduate students and their research advisors can exacerbate this or even be a cause of it (NASEM, 2018a). The report Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine notes how the graduate advising relationship in STEM creates unique risks for students because of their dependence on the advisor for career advancement and the mentor-mentee structure allowing for time spent alone together in isolated places (e.g., laboratories, field sites, hospitals) (NASEM, 2018b). Furthermore, there is a growing body of essays and blog posts in which former graduate students have shared their personal experiences with negative mentoring, which indicates that it occurs even if it has not been fully and systematically investigated.17 Therefore, to have a scholarly basis for the related findings and recommendations, this section draws more heavily from research on negative mentoring experiences in the workplace.

One of the first descriptions of negative mentoring experiences drew primarily from research on the development and functioning of other close relationships, such as friendship and marriage (Scandura, 1998). This conceptualization combined a characterization of relationships as having good or bad intent (Duck, 1994) with a categorization of mentorship as providing career and psychosocial support (Kram, 1985a) to create a typology of what Scandura termed “negative mentoring” (see Table 5-1). While negative mentoring experiences can result from ill intent—via bullying, revenge, or exploitation, for example—negative mentoring experiences can also arise from otherwise good intentions by both mentors and mentees, such as failing to mention an opportunity to a mentee because a mentor is concerned the mentee is already overburdened or wanting to support a mentee but having too many other obligations or responsibilities to honor a commitment. The mentee may perceive such omissions by mentors as an impression of their own incompetence or lack of belonging as mentees.

Building on this conceptualization of negative mentoring experiences, researchers studied 156 workplace mentees and found that more that 50 percent of them reported at least one negative mentoring experience, and that they collectively reported a total

___________________

16 The National Academies Committee on Supporting the Whole Student: Mental Health, Substance Abuse, and Well-Being in STEMM Undergraduate and Graduate Education has been tasked to “conduct a study of the ways in which colleges and universities provide treatment and support for the mental health and well-being of undergraduate and graduate students, with a focus on STEMM students to the extent fields of study are available.” More information is available at https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/projectview.aspx?key=51350; last accessed August 7, 2019.

17 For example, https://tenureshewrote.wordpress.com/2013/08/12/toxic-academic-mentors/ or https://smallpondscience.com/2015/12/07/what-to-do-you-have-a-bad-phd-advisor-in-grad-school/; accessed August 8, 2019.

TABLE 5-1 Negative Mentoring Typology

| Psychosocial Support | Career Support | |

|---|---|---|

| Bad Intent | Negative relations (e.g., bullying, harassment) | Sabotage (e.g., revenge, ignoring, career damage) or exploitation |

| Good Intent | Difficulty (e.g., offering conflicting advice, unintentionally forcing difficult choices, such as between work and family) | Spoiling (e.g., mentor not in right career track, not in position of influence) |

SOURCE: Adapted from Scandura, 1998.

of 168 distinct negative mentoring experiences (Eby et al., 2000). After analyzing these experiences, the investigators generated a taxonomy of 15 types of negative mentorship experiences that fit five major themes:

- Mismatched work styles, values, and personalities

- Distancing behavior, such as self-absorption of the mentor and neglect by the mentor

- Manipulative behavior, such as the mentor inappropriately delegating work to the mentee, taking credit for the mentee’s work, or harassing the mentee

- Lack of mentor expertise, including both technical and interpersonal incompetence

- General dysfunctionality, such as mentors having negative attitudes or personal problems

Studies of abusive supervision also provide insight into how negative mentoring experiences might manifest in STEMM mentoring relationships, because formal STEMM mentorship typically involves supervision with evaluative responsibilities that result in an inherent imbalance of power and authority. Abusive supervision is defined as “subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in sustained hostile, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors” (Tepper, 2000). Examples of abusing this supervisory role include telling mentees that their thoughts and feelings are “stupid” or belittling a mentee in front of others. According to research on detrimental research practices, neglectful or exploitative supervision in research is a violation of research integrity and can cause harm to the STEMM enterprise and the supervised party (NAS-NAE-IOM, 1992; NASEM, 2017b).

Incivility is a type of antisocial workplace behavior characterized by its low intensity and ambiguous intent to harm, such as rudeness, ignoring, excluding, and targeting with angry outbursts (Cortina et al., 2001; Schilpzand et al., 2016). Because incivility is defined as having ambiguous intent, it can be attributed either to the instigator’s ignorance or oversight or to the target’s misinterpretation or oversensitivity. A further distinguishing feature of incivility is that it is neutral in the relationship between the instigator and target; that is, uncivil behavior can originate from supervisors, peers, and subordinates. In

STEMM mentorship, incivility might be enacted by other members of a mentee’s research group and thus may be perceived as influenced by the mentor, even if the behaviors are not perpetrated by mentors themselves.

Some studies of mentorship in undergraduate and graduate research in STEMM have acknowledged variation in the quality of mentorship, such as mentors being absent, setting unrealistic expectations, or not providing enough guidance (Bernier et al., 2005; Dolan and Johnson, 2010; Harsh et al., 2011; Thiry and Laursen, 2011). In one study of student mentorship, more than 25 percent of psychology graduate students reported negative mentoring experiences with their dissertation advisor (Clark et al., 2000), and in another study, 50 percent of graduate and undergraduate mentees reported at least one significant conflict with a mentor (Goodyear et al., 1992). These results suggest that negative mentoring experiences do occur in academic training contexts, and by extension in STEMM contexts.18 Calls for reform of graduate education in STEMM note alarming rates of attrition from Ph.D. programs and emphasize the importance of improving mentorship to both reduce or prevent attrition and improve the experience of students who remain (Berg and Ferber, 1983; NASEM, 2018a).

Negative mentoring experiences can arise unintentionally, which parallel the concept of implicit bias.19 In recent years, the concepts and theories underlying implicit bias have become more widely accepted in STEMM and a common part of many institutional interventions and trainings (Carnes et al., 2015). Implicit bias occurs when automatic actions reflect implicit learning about individuals by virtue of their group membership. For example, gender-related implicit bias rooted in deeply ingrained gender stereotypes typically depicts women incorrectly as less competent in STEMM fields, particularly in leadership positions (NAS-NAE-IOM, 2007) or that women may not be as accomplished in math. Individuals do appear to be open to the notion that they may be implicitly biased when they learn that “bias happens”—that it does not necessarily imply ill intent—and that one can be vigilant and intentional about creating structures and processes that are less prone to implicit bias or that at least provide protections from its ill effects (Carnes et al., 2015). Similar trainings and interventions about negative mentoring experiences could be a powerful approach for addressing automatic biases that may contribute to ineffective or negative mentoring experiences.

Because of the potential for negative mentoring experiences to cause harm, additional research to better understand the prevalence and impact of negative mentor-

___________________

18 Although there are anecdotal reports of particular negative mentoring experiences associated with mentors who share surface-level similarities (e.g., harsher or more critical evaluations or even bullying from mentors who share a cultural, racial, or gender identity with their mentees), there is no published scholarship in this area.

19Implicit bias refers to “attitudes or stereotypes that affect [the holder’s] understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner. These biases, which encompass both favorable and unfavorable assessments, are activated involuntarily and without an individual’s [conscious] awareness or intentional control” (OSU, 2015).

ing experiences in STEMM education is necessary. Mentees who experience negative mentorship in the workplace report lower job satisfaction, higher likelihood of leaving their employer, and increased stress (Eby and Allen, 2002; NASEM, 2018b). These undesirable outcomes may result from mentee perceptions that the job, the organization, or the career may not be the right fit (Burk and Eby, 2010; Kristof, 1996; Su et al., 2015). In fact, one study found that workplace negative mentorship may be so damaging that mentees who experience it may be worse off than if they had no mentor at all (Eby et al., 2010). For one specific type of negative mentoring experience—sexual harassment—numerous studies have shown declines in professional and psychological well-being, including withdrawing from engagement with work, having thoughts of quitting or actually quitting a job, physical complaints (such as headaches, exhaustion, and sleep disruption), and symptoms of depression, disordered eating, stress, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Eby and Allen, 2002; NASEM, 2018b).

Negative mentoring experiences may be particularly harmful for mentees from UR backgrounds given the facilitative role that mentored research experiences can have in the success of STEMM UR groups. For example, studies investigating positive outcomes of mentorship have shown that undergraduate mentored research experiences in STEMM are particularly beneficial for UR at-risk students (Estrada et al., 2018; Thiry and Laursen, 2011). Furthermore, the effectiveness of undergraduate mentored research for UR students may hinge on the capacity of these experiences to promote a sense of fit with the scientific community (Estrada et al., 2011, 2017; Hurtado et al., 2009, 2011). Therefore, negative mentoring experiences may disproportionately harm these students. Future research should address this more directly by defining and characterizing negative mentoring experiences in STEMM and investigating its prevalence and impacts.

Studies of negative mentoring experiences, abusive supervision, and incivility have operationalized these phenomena primarily in the perceptions of the recipients (Eby et al., 2013; Schilpzand et al., 2016; Tepper, 2000; Tepper et al., 2017). Although perceptions have been criticized for their lack of objectivity (Linn et al., 2015; Tepper, 2000), this approach has multiple merits. First, directly observing mentorship would be intrusive and impractical, and negative mentoring experiences may not always be visible to observers. Second, mentors may not be aware that particular behaviors are problematic and may not be willing to report less-than-ideal behavior, making mentor self-reports of negative mentoring experiences equally subjective. Finally, mentee perceptions of mentoring relationships have been shown to fundamentally alter these relationships and to have long-term effects on mentee outcomes (Eby and Allen, 2002; Eby et al., 2008, 2010; Scandura, 1998).

MENTORSHIP EDUCATION20

The remainder of this chapter describes approaches to mentorship education for both mentors and mentees. The committee uses the term mentor education as the general term for all types of learning and development directed toward the person in the role of mentor and the term mentee education as that directed to the person in the role of mentee.21 The committee recognizes that there are many guidebooks and websites with information for mentors and mentees to help them advance their practice. It is beyond the scope of this committee’s charge to compile them all and report on their effectiveness. Instead, we focus in this section on face-to-face and online education modules developed for and tested with undergraduate and graduate mentees and their mentors.

Mentorship is like any skill: some individuals have natural aptitude, but for most people—and even those with a natural aptitude—instruction, practice, feedback, self-reflection, and intention are involved in becoming proficient. In fact, assuming mentees and mentors have the skills and knowledge needed to develop a successful mentoring relationship is naïve and can disadvantage mentees who lack sufficient social capital to connect with their mentors (Pfund, 2016; Pfund et al., 2013).22 While some progress has been made in educating mentors and mentees (Gandhi and Johnson, 2016; Pfund et al., 2014), standards and metrics can provide a rubric by which mentors and mentees get the most from their mentoring relationship (Lee et al., 2015).

Unweighted results of a special mentoring module from a recent survey of faculty with undergraduate teaching responsibilities found that 63.8 percent of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) faculty who responded to that module have participated in mentorship education, which was a higher participation rate than for all faculty (57.6 percent) (Stolzenberg et al., 2019). When faculty self-rated mentorship skills were analyzed according to who participated in mentorship education, faculty who had taken a mentorship workshop or other educational module rated the strength of their mentorship skills higher than those who had not participated in such education. Perhaps more importantly, faculty who had participated in a mentorship education workshop or program rated themselves higher on a range of skills, including accounting for the

___________________

20 Though the committee did not specifically examine incentives to promote faculty, staff, postdoctoral researchers, and student engagement in mentorship education, the last section in this chapter stresses the importance of “marketing” such programs to these groups. Box 5-3 provides a list of talking points to encourage participation in mentorship education. Chapter 7, in its discussion of culture change and the steps that various members of academic institutions can play in fomenting culture change, also lays out actions that institutions can take to incentivize faculty mentors, in particular, to recognize the importance of learning to be effective mentors and take the time to engage in mentorship education activities as part of their professorial duties.

21 The committee recognizes that individuals often occupy both the mentor and the mentee roles at the same time for certain career stages.

22 A discussion of social capital theory is part of the “Six Theoretical Models for Mentorship” section of Chapter 2.

biases and prejudices they bring into a mentoring relationship and working effectively with mentees whose personal backgrounds differed from their own (Stolzenberg et al., 2019). This survey also found that while the majority of faculty strongly agreed it was among their responsibilities to promote their mentees’ skills, such as their writing, less than a third strongly agreed they should provide for their mentee’s emotional development. These results show that some mentors do not think that provision of mentoring in the form of psychosocial support is their responsibility.

Persistence in STEMM is shaped continually by social and psychological influences that are well described by several social science theories and models described in Chapters 2, 3, and 4. In particular, the theories presented in Chapter 2 describe the factors relevant to effective mentorship and STEMM persistence and can be tied directly to the design of mentor and mentee education. Scholars and researchers of mentorship education incorporate these factors into designing interventions to guide mentors and mentees into highly productive and purposeful relationships. These relationships, in turn, ideally benefit both parties and increase the likelihood that mentees will continue on their path to becoming STEMM professionals.

Mentoring of emerging STEMM professionals should be inclusive and informed by what research has shown to produce positive outcomes for trainees from diverse backgrounds. Few mentors, however, have been educated on effective mentorship methods (Keyser et al., 2008; Silet et al., 2010), let alone on the needs of diverse scholars, and even fewer mentees have been educated about how to guide their mentoring relationships and careers. Indeed, research has shown that UR students’ requests for mentoring meetings are more often ignored than those of White men (Milkman et al., 2015), and that UR students typically receive less mentorship than their majority peers (Helm et al., 2000; Thomas and Hollenshead, 2001).

Formal Mentor Education

A range of organizations, including research-intensive universities, professional societies, government laboratories, nonprofits dedicated to mentorship, and corporations, have developed mentorship education programs or embedded mentorship education into their programming. Some of these programs are aimed specifically at STEMM research mentorship. Unfortunately, not much data have been published on the outcomes of these education programs. A few programs that include mentor education descriptions are noted in Chapter 4;23 two additional examples of mentorship education for mentors of undergraduate and graduate students in STEMM are

___________________

23 While there are many programs designed to benefit STEMM students and increase retention in STEMM that include mentorship as a component, few studies have isolated the effect that mentorship and mentoring relationships play in benefiting students.

- The U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, which has created an online mentor orientation program for faculty, project staff, and others who advise or mentor students, research participants, or interns in a formal or informal program.24 This program is aimed at both first-time and experienced mentors.

- The Nucleus Learning Network,25 which has developed customizable workshops and training options aimed at development of STEMM mentors for UR students.

One of the most well-studied and well-known approaches to mentorship education in STEMM is the Entering Mentoring program, developed originally in 2005 (Handelsman et al., 2005) and revised in 2015 (Pfund et al., 2015). This program introduces core mentorship competencies, allows mentors to experiment with various mentorship strategies, links mentors to mentorship tools (including those discussed above), and provides a forum in which small peer groups of mentors can address and solve mentorship issues. Training sessions, or modules, can be implemented and conducted as a series of hour-long, interactive sessions facilitated by one or two faculty, staff, or postdoctoral researchers. The six competencies from the curriculum are (1) maintaining effective communication, (2) establishing and aligning expectations, (3) assessing mentees’ understanding of scientific research, (4) addressing diversity within mentor-mentee relationships, (5) fostering mentees’ independence, and (6) promoting mentees’ professional career development (Pfund et al., 2015). This curriculum has been used to educate thousands of mentors throughout the United States across career stages and STEMM disciplines.

Research using both qualitative and quantitative methods has shown that mentors who participated in Entering Mentoring–based education assess their mentees’ skills and communicate with them more effectively, when compared with untrained mentors, a finding supported by reports from undergraduate researchers, who indicated that they had better experiences with trained mentors (Pfund et al., 2006). Entering Mentoring’s developers have tested a version of their program in a randomized, controlled trial at 16 sites, including 15 National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award institutions. Faculty mentors, 17 percent of whom were members of UR racial or ethnic groups, and their junior faculty and postdoc mentees, 43 percent of whom were members of UR racial or ethnic groups, reported a positive effect on participants’ mentorship knowledge, skills, and behaviors (Pfund et al., 2014). This was the first randomized trial to show a positive effect on both mentors and mentees from a research

___________________

24 More information is available at https://orise.orau.gov/stem/mentoring/index.html; accessed April 5, 2019.

25 More information is available at http://www.nucleuslearningnetwork.org/stemmentor; accessed April 5, 2019.

mentor education intervention. The Entering Mentoring curriculum has been adapted for mentors working with mentees across career stages and across STEMM disciplines.26

Entering Mentoring has been shown to be an effective approach to improving mentoring skills in the areas it targets, and it has been successfully adapted for use across multiple disciplines and career stages. However, there are opportunities to develop and test training interventions that address other factors that are known or hypothesized to affect mentoring relationships and mentee persistence. These include factors such as power dynamics, cultural awareness, research self-efficacy, and motivation. Some training modules that target these factors have been developed using the Entering Mentoring template.27 Other modules have been developed using other approaches (Lewis et al., 2016). All of these modules have been tested as real-time, process-based, interactive interventions.

The approach used for Entering Mentoring has served as a template for the development of new modules targeting factors known to engender student persistence, such as research self-efficacy (Butz, Branchaw et al., 2018). This approach may also prove useful for developing modules that can prepare those engaged in co-mentorship, peer mentorship, and near-peer mentorship, each of which is discussed later in this chapter.

Culturally Responsive Mentorship Education

Educating mentors to engage in culturally responsive mentorship is an area of intense interest by national, federal, and institutional leaders (Valantine and Collins, 2015). Despite its positive effects, same-race mentoring is challenged by the scarcity of UR faculty in STEMM. This scarcity can be overcome in part by matching mentors and mentees who share similar attitudes and values beyond demographics. This challenge can also be addressed by training all mentors to be more culturally responsive so that they can effectively mentor trainees from diverse backgrounds.

Mentors of various social identities may teach at diverse institutions. However, while they may express confidence in their ability to mentor diverse students, they may have never had education in culturally responsive mentorship. Inclusive practices require both education and intentional implementation even in the most racially/ethnically diverse institutions (NASEM, 2019). Even faculty engaged in various forms of mentorship or research professional development and support score only slightly higher than the mean on a national mentoring self-efficacy measure (Guerrero, 2019). Though there is some variation by racial background of the faculty, the sample sizes for specific UR racial groups were too small to detect significant differences in mentoring self-efficacy. However, national data and intervention programs reflect greater mentoring

___________________

26 All versions are freely available on the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Center for the Improvement of Mentored Experiences in Research website at https://cimerproject.org; accessed April 5, 2019.

27 For example, Butz et al., 2018, and Byars-Winston et al., 2018.

self-efficacy among faculty women than among men, and greater self-efficacy among those engaged in a faculty development intervention, although selection effects cannot be ruled out (Guerrero, 2019; Stolzenberg et al., 2019).

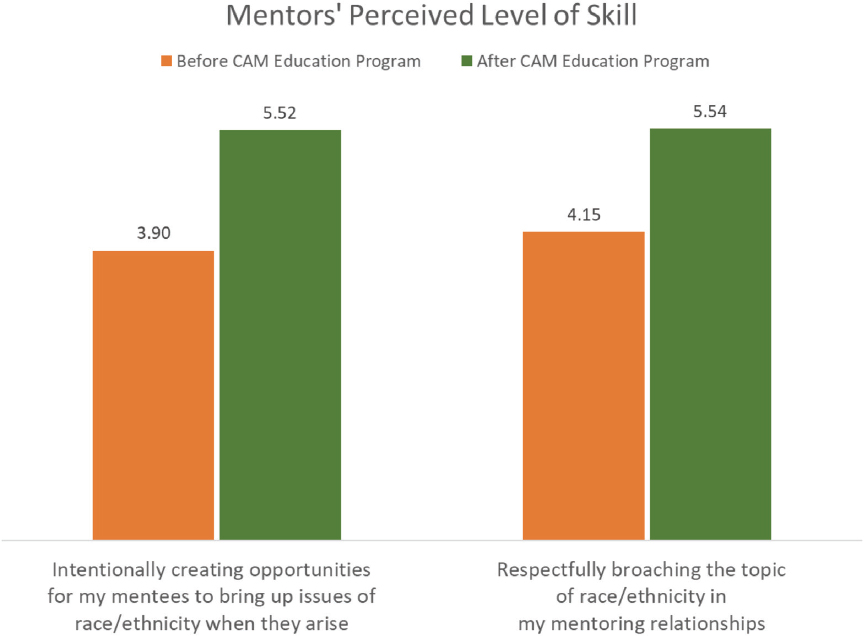

One pilot-scale evaluation involving 64 research mentors from three research-intensive universities tested a 6-hour program called Culturally Aware Mentoring (CAM) for research mentors. CAM includes a facilitator guide, an online pretraining module, and a set of measures to evaluate the effectiveness of CAM education. Participants reported they found the program valuable in that their cultural responsiveness and cultural skills increased, as did their intentions and confidence to deal directly with cultural diversity in their mentoring relationships (see Figure 5-1) (Byars-Winston et al., 2018).

Other efforts similar to CAM are under way, including the Promoting Opportunities for Diversity in Education and Research program at the National Institutes of Health–funded Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity site at California State University,

NOTES: N = 64. All differences significant at p < 0.001.

SOURCE: Recreated from Byars-Winston et al., 2018.

Northridge. Incorporating tenets of critical race theory into their mentor training based on Entering Mentoring, the program’s interventions include faculty participation in 16 hours of training.28 Mentor participants increased their understanding of structural racism and its impact on student development in STEMM, facilitated discussions of race, and strengthened their interpersonal skills (Saetermoe et al., 2017). Together, these findings underscore the importance of intentionality in implementation of mentor education,29 especially incorporating culturally responsive and inclusive practices, and better assessment to understand the effect of these interventions.

Formal Mentee Education

Various institutions and organizations have developed and implemented additional approaches to prepare mentees to effectively engage in a mentoring relationship. These approaches take many forms, including activities at orientation sessions, professional development conference workshops, department seminars, or full-semester courses.30 The overall goal of these approaches to mentee education is to help mentees be more proactive in their mentoring relationships. As previously noted, in some settings this has been referred to as mentoring up (Lee et al., 2015).

Few studies have examined the outcomes of mentee education approaches and programs for undergraduate and graduate students. One well-studied and extensive approach to mentee education for undergraduate students is the Entering Research curriculum (Balster et al., 2010; Branchaw et al., 2010). This curriculum was developed in an effort to formalize the programming that was being done with undergraduate students engaged in mentored research and to help undergraduate students gain knowledge and skill in navigating their mentoring relationships and research environments. Entering Research is a process-based curriculum that brings undergraduate researchers together to discuss the challenges they face as novices in learning to conduct research and in navigating their mentoring relationships. Entering Research can be integrated into existing undergraduate summer research programs or offered as a one-credit seminar in the academic year. Qualitative and quantitative data from diverse undergraduate student mentees who participated in Entering Research reported significantly higher gains in research skills, knowledge, and confidence when compared with a control group who participated in undergraduate research experiences but not in the Entering Research

___________________

28Critical race theory “analyzes the role of race and racism in perpetuating social disparities between dominant and marginalized racial groups.” Its purpose is to “unearth what is taken for granted when analyzing race and privilege, as well as the profound patterns of exclusion that exist in U.S. society” (Hiraldo, 2010, pp. 53–54).

29Intentionality refers to a calculated and coordinated method of engagement to effectively meet the needs of a designated person or population within a given context.

30 Some of these programs are noted in the “Intervention Programs that Include Mentoring Experiences” section in Chapter 4.

training. Of particular relevance were student-reported gains in “understanding the career paths of science faculty” and “what graduate school is like,” which were significantly greater than those of the control students. In addition, 41 percent of Entering Research students reported that this curriculum helped them learn how to effectively communicate and interact with their research mentors (Balster et al., 2010).

A revised version of Entering Research, developed by 27 scholars from 15 institutions, includes 96 activities and a trainee learning assessment tool (Branchaw et al., 2019). The new materials are designed for both undergraduate and graduate student mentees across STEMM disciplines, and are available from the Center for the Improvement of Mentored Experiences in Research website.31 The activities and assessment tool are organized by the Entering Research conceptual framework, which includes seven areas of trainee development: (1) research comprehension and communication skills, (2) practical research skills, (3) research ethics, (4) researcher identity, (5) researcher confidence and independence, (6) equity and inclusion awareness and skills, and (7) professional and career development skills. These activities can be integrated into existing undergraduate or graduate research training programs, or offered as stand-alone workshops, for-credit seminars, or courses in the academic year.

Mentorship Education for Peers and Near-Peers

It is also important to teach students the skills of serving as effective peer and near-peer mentors. The literature on team science (NRC, 2015a) indicates that creating effective teams requires more than simply putting people together and assuming that their interactions will be effective. Therefore, it is necessary to offer mentorship education for peer and near-peer mentors. As described in Chapter 4, many programs are embedding peer and near-peer mentorship into their overall approach. For example, the Canvas Network’s online 6-week mentorship education program, offered by the Ohio State University Global One Health Initiative, works specifically with third- and fourth-year undergraduates who will be peer mentors for UR freshmen and sophomores majoring in STEM. This program offers a course, delivered online and developed through a supplement to the university’s NSF Louis Stokes Alliances for Minority Participation grant, to “prepare student mentors for the critical role they will assume in improving the academic and social transition of their mentees by helping them achieve social and academic success” (OSU, 2019).

Some initiatives have described efforts to prepare peer and near-peer mentors. For example, one study described the effect of peer mentorship on women’s experiences and retention in engineering during their first year of college. The peer mentors attended a half-day training that included reflections on being first-year students, preparation for their meetings with mentees, and discussion of expectations for the program

___________________

31 See http://www.cimerproject.org; accessed April 4, 2019.

(Dennehy and Dasgupta, 2017). Another study found that e-mentorship modules that train graduate students for peer or near-peer mentorship improve self-efficacy for women in STEMM, facilitate student success in STEMM programs and the workplace, and increase persistence and graduation rates through college STEMM programs (Wendt et al., 2018). One study examined the risks and benefits for being a peer mentor or having one mentor in a first-year undergraduate course. Findings from this study indicate that “even in programs where peer mentor training is ongoing and established, assumptions cannot be made about the understanding of the roles, risks, and benefits involved in such relationships. This study demonstrates that students, instructors, and mentors all have different perspectives about a mentor’s role and how that role should be enacted” (Colvin and Ashman, 2010).

In general, many programs integrating peer-mentoring approaches and the preparation of students for these roles have not published evaluation data, let alone conducted rigorous studies, of peer mentoring. A 2014 review of undergraduate mentoring programs identified only three studies that included some form of peer mentoring, only one of which used a quasi-experimental design (Gershenfeld, 2014). There is an opportunity to contribute to the literature on outcomes of graduate student peer-mentoring interventions. One study examined the effects of 35 dyads in a graduate student peer-mentoring program (Grant-Vallone and Ensher, 2000). Results showed that peer mentoring provided the graduate students with both increased levels of psychosocial and career support, with peer mentors providing higher levels of psychosocial support than career support.

High-Touch and High-Tech Synchronous, Online Education

The original Entering Mentoring curriculum has been adapted and implemented in synchronous, online platforms such as Blackboard Collaborate through the NSF-funded Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning. As with the face-to-face version of Entering Mentoring, the online version allows participants to engage in small- and large-group discussions, chat-room discussions, collaborative writing, and group problem solving. Participants from three implementations of Blackboard Collaborate describe similar learning gains for online and face-to-face education, with all of the 39 responding participants indicating they felt the online environment promoted an inclusive learning environment and that the experience improved their confidence in their mentorship ability (McDaniels et al., 2016).

The National Research Mentoring Network Mentor Training Core offers other trainings and modules, such as the one on cultural awareness described earlier in this chapter, some of which have been prepared and tested for online delivery. Preliminary findings from a national randomized control study testing the effectiveness of a culturally responsive mentorship module added to the Entering Mentoring curriculum revealed that faculty mentors receiving the additional module content were more likely to view their

personal racial/ethnic identity as relevant to their mentoring than did those receiving the standard curriculum (Byars-Winston and Butz, 2018). The Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning also offers online mentor training regularly to graduate students and postdoctoral and faculty mentors.32

Asynchronous Online Education

For some mentors, engagement in real-time, interactive mentorship education can be difficult due to scheduling and other professional responsibilities, such as clinical duties. Another approach to mentor education is the use of asynchronous, self-paced, online professional development. One example is Optimizing the Practice of Mentoring (OPM), developed in 2012 by investigators at the University of Minnesota (Weber-Main et al., 2019).33 This course, which takes 90 to 120 minutes to complete, prepares faculty to be effective research mentors to graduate students, junior faculty, and postdoctoral researchers by providing descriptions of different mentorship approaches, an overview of roles and responsibilities within the mentoring relationship, a structured approach to mentorship, a toolkit of resources, and interactive learning exercises to illustrate strategies for effective mentorship. At the end of the course, participants develop an individualized mentorship action plan for applying what they have learned. Since mid-2012, mentors from more than 300 institutions, averaging 225 mentors per year, have accessed this module. Early evaluations demonstrated that 87.5 percent of survey respondents reported “making” or “planning to make” changes in their mentorship practices as a result of online training (Weber-Main et al., 2019). Statistically significant increases between pre-to-post–OPM completion were reported in self-ratings for overall mentorship quality and confidence to mentor effectively. In partnership with the University of Wisconsin–Madison and other NRMN collaborators, OPM has been expanded to now include three additional modules that have been tested in combination with face-to-face discussion sessions.

Other examples of self-paced online education for mentors of undergraduate and graduate students include a range of recorded webinars and videos, such as the NRMN training videos that are part of its virtual guided mentorship program and training,34 or the mentoring science trainees’ playlist from iBiology.35 While these aids may be helpful in preparing mentors and mentees to effectively engage in their online relationship, little has been published on their impact; thus, a comprehensive listing of all such approaches is not included in this report.

___________________

32 More information is available at https://www.cirtl.net/; accessed April 26, 2019.

33 More information is available at https://www.ctsi.umn.edu/education-and-training/mentoring/mentor-training; accessed April 26, 2019.

34 More information is available at https://nrmnet.net/mymentor/; accessed April 24, 2019.

35 More information is available at https://www.ibiology.org/playlists/mentoring-science-trainees/; accessed April 24, 2019.

Education in Small Groups

All the mentor and mentee education approaches described above use small-group discussions in which peers learn from one another.36 The small-group setting creates a safe space where mentors or mentees can talk openly about pressures and challenges that are often difficult to reveal and share. In particular, UR mentees benefit from learning in settings where they can feel safe to share the hurdles they face as UR individuals. The effect of small groups has been noted for Entering Mentoring and Entering Research (Branchaw et al., 2010; Handelsman et al., 2005; Pfund et al., 2015), and has been demonstrated in several other mentorship programs as well.

Incentivizing Engagement in Mentorship Education

For institutions and organizations that want to implement mentor and mentee education, it is important to have a plan in place to effectively market the program to faculty, students, and postdoctoral researchers and engage them in mentorship and mentoring relationships. The desire to have practical strategies for garnering interest of mentors and mentees in mentorship education was one of the most asked-about topics in the listening session conducted for this report. This interest was also expressed at the second national conference on the Future of Bioscience Graduate and Postdoctoral Training, which highlighted the desire for institutions to make it widely known among faculty, students, and postdocs that mentorship education brings with it tangible benefits that can improve the outcomes of and satisfaction with mentoring relationships (Hitchcock et al., 2017). Some potential talking points are highlighted in Box 5-3.

___________________

36 More information on small-group learning is available in Springer et al., 1999; Svinicki and Schallert, 2016; and Wilson et al., 2018.

This page intentionally left blank.