3

Embedding Health Literacy in Clinical Trials to Improve Recruitment and Retention

A discussion panel explored how to embed health literacy into clinical trials from the beginning of the process in order to improve recruitment and retention. Annlouise R. Assaf from Pfizer Worldwide Medical and Safety served as the moderator. The panelists included Ebony Boulware, professor of medicine, chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine in the Department of Medicine, vice dean for translational science, and associate vice chancellor for translational research in the School of Medicine at Duke University; Catina O’Leary, president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Media (HLM); Alicia Staley, senior director, patient engagement for mHealth at Medidata Solutions; and Christopher R. Trudeau, associate professor of medical humanities, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and associate professor of law, Bowen School of Law, University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Assaf introduced this panel’s topics: communicating about clinical trials and preparing for informed consent; health-literate recruitment strategies; and developing health-literate materials. She explained that the panel would discuss what goes into creating health-literate materials and how these efforts go beyond plain language. She also mentioned that the panel would touch on informed consent documents and issues faced by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs); how to enroll minorities with variable health literacy into clinical trials; and the regulatory trend toward health literacy in clinical trials. Each panelist introduced their work and their interests as they related to improving recruitment and retention in clinical trials. Assaf posed several of her own questions for each panelist to discuss, and she then

facilitated a discussion between the panelists and the audience. A summary of key points made by each speaker can be found in Box 3-1.

ENROLLING MINORITIES WITH VARIABLE LITERACY IN CLINICAL TRIALS

Ebony Boulware, Professor of Medicine, Chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine in the Department of Medicine, Vice Dean for Translational Science, and Associate Vice Chancellor for Translational Research in the School of Medicine, Duke University

Boulware explained that she and her colleagues have focused on clinical trials that enrolled minorities with various literacy levels. She and her team had mainly worked on behavioral and educational interventions that were implemented in clinical settings, she said, as opposed to drug trials. Boulware noted that, as Bierer had previously alluded to, there is a well-justified history of mistrust regarding the research enterprise on the part of minority populations, specifically the African American population, in

the United States.1 For Boulware that has meant that understanding and identifying with those historically marginalized or mistreated populations in the clinical trials context was a crucial aspect of designing a trial, enrolling participants, and conducting the trial with health literacy competencies. Highlighting three studies in which she and her colleagues had worked on enrolling African American participants, she observed, “We’re talking about how we engage people and how we relate to them as real people with real histories.”

PREPARED Study—Baltimore, Maryland

The first study Boulware described had enrolled African American patients with kidney failure and who were being treated at dialysis units in Baltimore, Maryland. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either their usual care alone or that care plus culturally tailored educational interventions to improve their shared and informed decision making about their kidney treatments. The enrollment rate was 66 percent, and the retention rate was 80 percent (Boulware et al., 2018).

ACT Study—Baltimore, Maryland

The second study Boulware described focused on African Americans with uncontrolled hypertension, who were being seen in primary care settings. The interventions included a community health worker, blood pressure cuffs, and other educational interventions to improve blood pressure self-management and control. The enrollment rate was 60 percent, and the retention rate was 83 percent (Boulware et al., 2020).

TALKS Study—Durham, North Carolina

The third study was also focused on providing educational and behavioral interventions, as well as financial support intervention, for African American participants at a transplant center in Durham, North Carolina. The study explored whether the interventions helped participants when considering a kidney transplant. The enrollment rate was 65 percent, and the retention rate was 87 percent (Strigo et al., 2015).

___________________

1 For more information regarding minority population mistrust in the clinical research enterprise, see http://buildingtrustumd.org/unit/informed-decision-making/learning-from-the-past (accessed October 17, 2019).

LESSONS LEARNED FROM BEHAVIORAL TRIALS OF AFRICAN AMERICANS

Boulware observed that the activities were fairly diverse, but the numbers for recruitment and retention were “reasonably successful,” because patient and participant engagement before, during, and throughout the studies had been a critical component of their trial designs (see Table 3-1 for complete statistics on the studies). She added that there were several approaches to these studies that improved the enrollment and retention of diverse populations with various literacy levels, and that investigators should do the following:

- Engage potential participant populations well before the study starts

- Be willing to substantially change designs or materials from the original protocol to accommodate what the potential participant population thinks is more appropriate

- Work with IRBs to clarify and tailor consent forms and communicate with potential participants more clearly

- Tailor recruitment letters, not just with plain language but with accessible and clear formatting, straightforward messaging, and cultural sensitivity

- Continue to tailor materials throughout the study

- Follow up via phone calls and home visits, in addition to the usual postcards or letters, to keep participants engaged and to help them understand the importance of their involvement

Boulware added that she was excited by other examples of newer consent forms she had seen earlier in the day, as well the use of video and graphics to engage and educate potential participants. She asked the workshop to consider whether retention and enrollment are the best metrics of success for a trial, and whether investigators should consider other factors:

Should we really be thinking about other metrics that have to do with the experience of the participant and their satisfaction with their engagement with the trial itself that goes above and beyond the receipt of the intervention?

TABLE 3-1 Three Small Clinical Trials with African American Participants

| Study | Final N | Enrollment Numbers | Enrollment Rate | Retention Rate | Retention Rate by Arm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PREPARED | 92 | Screened/eligible: 189 Declined: 54 Consented: 105 |

66% | 80% | Arm 1: 84% Arm 2: 73% Arm 3: 84% |

| ACT | 159 | Screened/eligible: 308 Declined: 93 Consented: 185 |

60% | 83% | Arm 1: 84% Arm 2: 73% Arm 3: 84% |

| TALKS | 300 | Screened/eligible: 465 Declined: 106 Excluded for other reason: 147 Consented: 300 |

65% | 87% | Arm 1: 89% Arm 2: 86% Arm 3: 87% |

SOURCES: Adapted from a presentation by Ebony Boulware at the workshop Health Literacy in Clinical Trials: Practice and Impact on April 11, 2019; Boulware et al., 2018, 2020; Strigo et al., 2015.

HEALTH-LITERATE MATERIALS FOR RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION

Catina O’Leary, President and Chief Executive Officer, Health Literacy Media

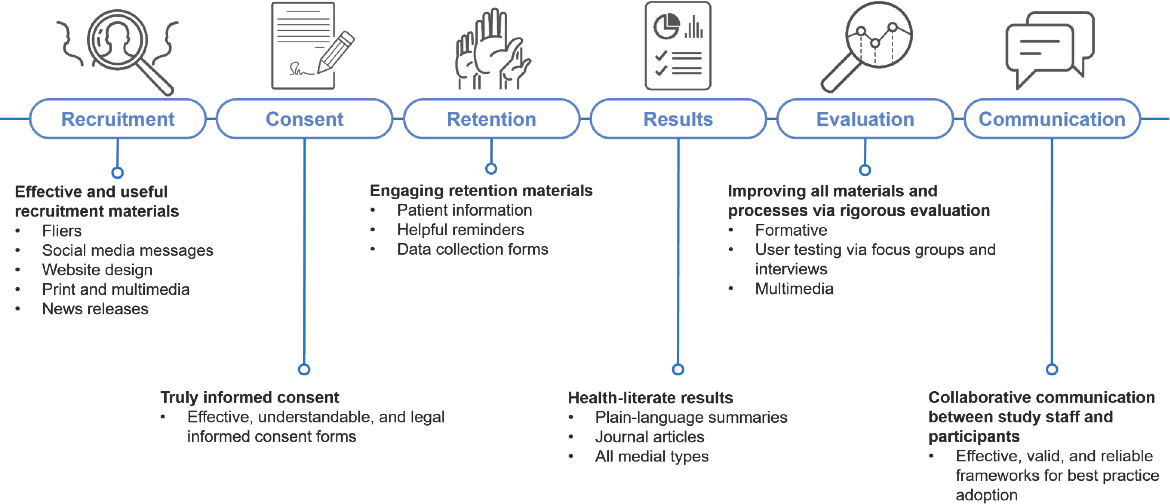

O’Leary emphasized that it is important to think of health-literate materials beyond consent forms and plain-language summaries. She noted that recruitment for clinical trials can involve a range of materials: flyers, letters, social media messaging, websites, and press releases (see Figure 3-1). These materials can be utilized in print or multimedia formats, she added, and “every single material developed to communicate with people about the possible study can benefit from health-literate, usable, accessible language.”

O’Leary pointed out that printed materials about studies can be underutilized by clinical trial investigators and participants:

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Catina O’Leary at the workshop Health Literacy in Clinical Trials: Practice and Impact on April 11, 2019.

People depend on verbal communication to help [hearing] people understand processes. We know that doesn’t work well all the time. People need to be able to go home and review study information, and talk it through with people around them.

She added that there are plenty of ways to engage participants during and after trials, noting that journal articles about the trials should not only be accessible but usable and understandable. Each process within a trial should be rigorously evaluated, she said, but also usable by participants and others. She shared three examples of print materials that HLM had adapted to include health-literate practices.

Sample Informed Consent Form

O’Leary shared two versions of the same sample consent form: one before the health literacy adaptations, and one after. Janssen’s investigators spent a lot of time looking at what participants would need for a global consent form, she said. She added that they performed a lot of user testing, and co-designed the material with users. She noted that one might not expect users to care much about the details of consent form design, but every person in the focus groups cared about the colors, words, and even how heavy the lines were between the sections, or how visually demarcated different segments of the trials were. O’Leary said that each of those elements helped users “understand the difference between what happens when participants are screened, when participants are in the treatment period, and when investigators perform follow-up after the trial.”

The timelines “really mattered” to users, O’Leary continued. When the forms used colors to separate blocks within the timeline, it made more sense to the users, and they really appreciated that. She also noted that HLM converted original paragraphs of text into a table, underscoring how helpful the visual elements were for users. Adding that the updated informed consent form was “not controversial,” she emphasized that IRBs are accustomed to reviewing tables instead of text so developing consent forms like HLM’s could make more patients and participants happy without impeding approval. “I would recommend having conversations [with other investigators] about using forms like this,” she said.

Sample Participant Study Guide

O’Leary showed another example of an original participant study guide alongside a newer version, adapted by HLM for Merck. The original, she noted, is dense with text, titled “Injection Guide for Study Drug or Placebo—Panel A, Days 1–5, and Panel B, Days 6–10,” while the adapted

guide is a more visual and colorful guide, titled “How to give yourself the study medicine.” She continued:

There are a lot of pieces about this guide that just jump out—the use of color, the boxes to chunk information, headings that really make a lot of sense for people. But the most dramatic piece of this is the image at the bottom of the drawings. An artist drew what it looks like to take the injection and how people should use it. This drawing tests really well, and people understand what this means and how to hold the medicine and how to give themselves the medicine. They have both the visual image and the words to go along with it.

The drawings are quite simple, culturally, as well. By using drawings instead of images, the guide doesn’t make any assumptions about who you are or what it means to be using it.

Sample Trial Results Summary

O’Leary’s third and final example was a clinical trial summary. In the original summary, the text is dense and full of jargon, she noted. There were several components to adapting the summary to make it health literate. She explained that the first page has a short summary of everything that happened in the trial. “What we know from patients,” O’Leary said, is that patients are “quite happy to read 8 or 10 pages of your summary after they know if a trial has happened with people like them, and whether it made a difference. In that case, they really want to dig in, but they don’t want to do it until they are certain it applies to them. They don’t want to expend the mental energy.”

Because of this, she said, HLM put that information into an executive-level summary, using color chunks, clear headings, and bold titles with clear information. The adapted summary “gets all the elements that are important for participant safety but utilizes a couple of sentences that seem to work well for people,” she said. O’Leary added, “We test these and patients really understand it.”

O’Leary described the story of a 35-year-old study participant who benefited from the health-literate trial summaries. He had a chronic condition that left him with pain and physical disfigurement—so severe that he dropped out of school, she said, and he had been frequently misdiagnosed.

It took a long time to get reasonable treatment. But he said that when he read the [HLM] summary, he understood his condition for the first time and knew what was going on with his body. After participating in trials for many years, after his whole life being affected, it took a summary that was well-written to explain what was going on. And because of that, he

said, he felt hopeful: that understanding led to hope and I think that’s really important.

TECHNOLOGICAL TOOLS TO IMPROVE PATIENT EXPERIENCES

Alicia Staley, Senior Director of Patient Engagement, mHealth Solutions, Medidata

Staley opened by quoting Dr. Warner Slack, an electronic health record pioneer who argued that “patients are the most underutilized resource in healthcare.”2 She noted that her personal patient experience shaped much of the work she did at Medidata. Staley is a three-time cancer survivor, and in 2011, she co-founded the #bcsmcancercommunity social media community. The online community fosters information sharing among breast cancer patients, she said.

Regarding patient comprehension and understanding, Staley explained that she referred to it as the “Charlie Brown theory of clinical trial comprehension,” because adults and teachers in the Charlie Brown cartoon only ever communicate by making the sounds of a muted trombone. When you are first diagnosed with cancer or trying to make a clinical trial, she said, “that’s exactly what you hear. Something like ‘blah, blah blah, informed consent, blah blah blah, and sign here.’”

As a patient, when you receive lot of information, Staley said, you are often not given the proper context in which to evaluate it, take it in, or process it in a way that really makes sense for you in a critical moment. People learn and process information in different ways, Staley noted. “Some people have to take information in through a book, while others need video or audio. We have to be able to present information in a way patients can receive it.” She urged the workshop attendees to consider the context of the patient receiving information:

- Have they just received a new diagnosis?

- Are they returning after one treatment or another has failed?

- What are the technological inputs this patient is encountering?

- Is information being presented over the Web?

- Is information being presented in a clinic or on a tablet?

- How do you judge the comprehension level of the patient?

___________________

2 For more information about Dr. Warner Slack and his work, see https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/362/bmj.k3194.full.pdf (accessed September 17, 2019).

Staley added that she had several doctors over the years ask whether she had understood their conversation. She said her first reaction was always “yes, yes, yes, I’ve got it,” while she walked out of the clinic room, overwhelmed with no context or way to comprehend any of the information she had just received. Now, she said, she knows better:

I have to leave the appointment, take time to process, and then come back to my doctor and talk about it more. I’ve been fortunate to be with the same oncology and primary care team now for more than 25 years. They’ve worked with me to learn how I take in information so they know I might need an extra appointment or a phone call follow-up or an email follow-up to process what they have shared with me. We have to be flexible enough to allow for those kinds of interactions to take place in clinical trials.

Staley urged the workshop attendees to consider “educated consent” as a twin to the informed consent process. “Yes,” she said, “there is a [legal] informed consent process where a patient needs to sign off on their participation, but what can we do to infuse education around that process?” She believes, she said, that investigators do not focus enough on education in this context, which is a true multimodal learning opportunity. “We have to build multimodal learning opportunities into the whole consent process. Are you an auditory learner? Are you a visual learner? Do you need to step away from the information for a moment and process it over time?”

Staley reiterated the importance of communicating and presenting information to caregiving teams who support patients. Patients often rely on family and friends to help them through the diagnosis and treatment process, she added. “Are we doing enough so that the patient can confidently go back to their family or care team to share updates or solicit input?” She highlighted something she had heard Collyar say earlier in the day: “The right information at the right time in the right context is really the key for truly engaging patients in clinical research.”

Staley summarized by emphasizing three components of best practices for technology improving patient experiences in clinical trials:

- Design: Are you creating material with the patient perspective in mind?

- Engagement: Are you building engagement points for the patient to continually learn throughout the process? What works best—audio, video, interactive applications, paper?

- Activation: What’s the environment for information sharing? Can the patient actually act on the information you are presenting to them? Are numbers—figures or statistics—useful information the patient would know what to do with?

REGULATORY CHANGES IN CLINICAL TRIALS

Christopher R. Trudeau, Associate Professor of Medical Humanities, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and Associate Professor of Law, Bowen School of Law, University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Regulations Informing Health Literacy Practices in Clinical Research

Trudeau explained that he viewed his role as an amplifier of the previous panelists. The regulatory context supports all of the activities and examples the other speakers had shared, he said. There are three recent regulatory changes that promote integrating health literacy into clinical trials: two among the European Union (EU) and one in the United States:

- An EU regulation about clinical trials lay summaries

- The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

- The U.S. Common Rule revisions

Referring to the controversy over the term “lay summaries,” Trudeau noted that everyone could be a “lay” person, depending on the context. “You might be a Ph.D. in epidemiology but you’re a lay person in the law to me.” The European Union now requires lay- or plain-language summaries, accessible to participants of clinical trials, as Collyar had mentioned during her presentation. The GDPR, Trudeau explained, is a regulation that protects the data of those living in the European Union.3 When seeking consent, he continued, organizations should ensure that they use clear and plain language in all cases. This means, he added, the message should be easily understandable for the average person and not only for lawyers. He noted that the language of the GDPR also recognizes that minors merit specific protection when it comes to data protection, and the GDPR requires that any communication addressed to children be written in plain language so they can easily understand. It is a broad regulation, Trudeau said, but it has “huge implications” for multinational clinical trials because it applies to any type of data collected from anyone while in the European Union.

___________________

3 One section of the GDPR focuses on strengthening the conditions for user consent, forbidding the use of illegible terms, and conditions full of legalese. “The request for consent must be given in an intelligible and easily accessible form, with the purpose for data processing attached to that consent. Consent must be clear and distinguishable from other matters and provided in an intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language. It must be as easy to withdraw consent as it is to give it” (Trunomi and CommVault, 2018).

The U.S. Common Rule revisions “really support what it is we’re trying to do here today,” Trudeau said. Having taken complete effect in January 2019, it is the “regulatory hammer that we can use to help encourage others and actually promote health literacy throughout not only the consent process but the entire clinical trial process as well,” he added.

The Common Rule revision requires that research consent materials be understandable, Trudeau continued, quoting from the Federal Register:

[It] must be organized and presented in a way that does not merely provide lists of isolated facts, but rather facilitates the prospective subject’s or legally authorized representative’s understanding of the reason why one might or might not want to participate. (GPO, 2017)

Referring back to the original and revised informed consent documents that O’Leary had shared previously, he lauded Janssen for embracing the challenge to facilitate participant understandings of the timeline, the different stages of the trials, and what happens with each trial visit. “So if you are at an organization where your IRB is not quite up to speed or your organization itself is not, you now have some regulatory support” for incorporating health literacy into your trials, Trudeau said. The change requiring that consent needs to begin with key information, said Trudeau, is “great for us in the health literacy world because it recognizes the individuality of consent, whereas the templates that cover every study, from low risk to phase one and the super high-risk studies, might not work so well.”

Informed consent must begin with a concise and focused presentation, he continued. “That’s not just the wording, it’s the organization and presentation of the document.” Research needs to be done on this, he said. “How do people want to see the information? What’s the most important thing that participants would want to know in a phase 1a study versus a sleep study, for example?” The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP) is the only guidance researchers have, Trudeau said, adding that it is indirect because “they make recommendations to the Office for Human Research Protections, which could then be adopted as guidance.”

Using Health Literacy to Inform Legal Concepts

Trudeau also raised the concept of “a reasonable person,” which has been around in other legal contexts “for hundreds of years.” Quoting SACHRP’s commentary on the Common Rule revisions, he said:

The reasonable person concept recognizes that it is impossible for researchers to determine what information every individual participant would

consider helpful in deciding whether or not to participate. Instead, it asks researchers to include what reasonable people in the same or similar circumstances would want to or need to know (SACHRP, 2018). Health literacy can play a role in this by helping determine what a reasonable person would understand. The reasonable person concept in law [was] developed before we had any research regarding literacy rates and health literacy research and practice, and we can learn from that to create what a reasonable person might be or know or do in various situations, through research. It’s very contextual, as we have heard—it’s going to be different in a cancer study versus other types of studies. So user testing and focus-group testing need to become a standard practice. That is the only way that you can really know for your specific study population what they would prefer and what would help them understand.

DISCUSSION

Assaf began the moderated discussion by emphasizing that investigators need to engage trial participants earlier in the process than they have been doing traditionally. She added that labels and package inserts can be confusing to patients, which is why “we can’t wait until it’s recruitment time to do something about this. We need to have potential participants involved earlier in developing materials,” she said, “so we are asking questions we know they understand.”

Lessons Learned from Failure

Assaf noted that during conferences and workshops, researchers and practitioners often share best practices, but less frequently share failures. “I think there’s a lot we can learn from them,” she said. She shared that as an investigator in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), she and her colleagues tried many recruitment strategies for the trial, and not all of them were successful. She recounted that in this particular trial, some potential participants knew they might not personally benefit from the trial, but understood that the knowledge gained would help future generations. The recruiting relied on the altruistic nature of the trial, she added, and her team tried several print and video messages before they developed an informed consent process that potential participants could understand.

Assaf and her colleagues also found success in identifying different recruitment strategies for different populations. For recruiting African American participants, for example, they found success reaching out to pastors. For recruiting senior citizens, they found success in visiting senior centers and sharing meals with the prospective participants. The researchers also found success through a community coalition, in which volunteers recruited in their own communities for potential participants.

Assaf asked the panelists if they had any experiences in which a strategy for recruitment, informed consent, or developing lay summaries did not work, and, if so, what they learned from the experience.

Staley replied that she had previously worked for a company that aimed to match patients to clinical trials based on genomic information from their cancer tumor profile. The assumption was that messaging could be generic and “put on blast” on social media, print, radio, or the Web, and that that would take care of recruitment, she said. It seemed to her that the recruitment strategy was “filling your funnel and all of these patients will magically fall out of the bottom and be recruited and enrolled in a clinical trial,” she said.

Staley and her team learned a few lessons about recruitment and enrollment quickly, she said, including the following:

- Recruitment and enrollment are about health literacy, technology literacy, and cultural literacy.

- You cannot create a single message that works for everybody.

- You have to be willing to be agile and flexible around your messaging.

- You need to be able to create a feedback loop in your recruitment and engagement process that allows for learning as you step into new communities for the first time.

- Those new communities will often share what works and what does not work for them, and if investigators do not respond in kind, they will violate the trust and respect originally offerred to them.

- Before you begin building your messaging, work with communities from which you want to recruit.

She added that building relationships with communities that need help or care or new treatment options is both a requirement and a new component of cultural competence.

O’Leary agreed with Staley about the importance of messaging, adding that she had faced recruitment and retention challenges while engaged in community research at Washington University in St. Louis.

We had some funding to create a fancy database with algorithms to enroll people from communities, to match them to open clinical trials and deliver them to the site of a trial [that] they had matched and in which they were interested. It seemed like a no-brainer. People qualified, they wanted to do it, and we took them to the door. But we still couldn’t get them all enrolled, because the investigators couldn’t figure out how to do it with folks that didn’t seem to have [the resources] to get back to the site.

Successful recruitment and enrollment are really complicated, she continued, noting that her team at Washington University used that experience to improve the subsequent round of recruitment. “It’s an iterative process that is never right the first time. So I think that flexibility and collaboration with the folks you’re trying to reach is really the gold standard.”

Trudeau explained that several years ago, he worked with a hospital association to develop a website focused on transparency. He had been “really excited” about a new gauge visual on the website that shared safety metrics at various hospitals, in which a high safety rating would read as a high percentage out of 100, resembling a speedometer. However, users interpreted the high scores negatively, because they connected it with speeding in a car. Trudeau and his team then reconfigured the visual for the website, he said, adding, “I would venture to say that every time I have user-tested a document that I’ve written, I have learned something.”

Boulware noted that she had extensive experience in testing people’s understanding of information they are given about their medical condition and also that she spent 1 year developing materials for patients with kidney disease, so she was familiar with experiencing failures and learning from them quickly. She agreed with O’Leary about health-literate messaging going beyond words, including numbers and numeracy and visual depictions. “We spend a lot of time trying to figure out how to explain a ‘big difference’ versus a ‘small difference’ to a patient,” she added. “We’re even thinking about how people think about French fries: small, medium, large? How do people think about magnitudes and quantities?”

User testing is a constant, she added. “I’ve never put a document out there that didn’t need at least ten iterations to improve it, and it wasn’t perfect at the end, either. I think this is evolving; we’re all constantly undergoing and moving on from failures.”

Assaf agreed that numeracy was an essential component of health literacy, recounting that many participants in the WHI had trouble understanding relative risk compared with absolute risk. She added that Pfizer, with help from Staley, has developed infographics and a web page that help explain the difference between absolute and relative risk for patients looking to make choices about their treatment.4 The web page puts the concept of risk into context, she said, for example, crossing the street versus getting into an airplane.

___________________

4 To view some of Pfizer’s infographics, see www.pfizer.com/MedicineSafety (accessed September 18, 2019) and to view Pfizer’s web page on understanding risk, see www.pfizer.com/products/patient-safety/Making-Good-Treatment-Choices/Understanding-Risk (accessed September 18, 2019).

Strategies for Sharing Trial Results

Olayinka Shiyanbola from the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy expressed her appreciation for each of the panelists’ presentations. She asked two questions:

- What are some other strategies for distributing results at the end of a trial?

- What are some strategies for sharing information with people who have reading difficulties or are unable to read the trial summary?

O’Leary replied that there is a focus on lay summaries because they are a regulatory requirement. Because of the nature of some large or cross-continental trials, she said, the summaries are already not necessarily the best approach to sharing information, just the required one. She continued

I also don’t think [lay summaries] are bad. It’s important that participants have a piece of paper that is readable that they can find online or get from their doctor’s office. It’s good support for conversation and understanding, and it’s an easy box to check off, that everybody received one—it’s a good start. But in community-based research, investigators often try to gather initial groups of participants, discuss what happened, and use it as an opportunity to think about what’s next and what was missing. Based on feedback from research participants, some investigators have started writing scientific papers that are published in journals and go on your CV, as well as another version that is more public facing, and is published in a newspaper or in a neighborhood newsletter. I hear that participants really like those. I think some of the advocates here might agree that they would want to be engaged all the way through the process and that includes deciding at the end [and after] how we describe the trial itself.

Video is always great; it’s just so expensive. I have found that researchers don’t have a lot of money on the back end of a trial to pay for a complicated production, so you have to figure out what your investment is going to be: is it worth more for you to have a video that everyone can see, or to have deep engagement with a smaller group? Those are all choices that reflect the philosophy and values connected with the community and the trial.

Boulware added that at Duke, she is developing an information portal where study participants can log in at the beginning of the trial, and have constant communication with the investigative teams throughout the entire journey. This option is limited because it requires access to technology, she noted, but it will enhance communication for many participants, including at the end of the study.

Assaf said that she had held small group sessions at the ends of the trials she had worked on, especially for particularly vulnerable populations. The participants would come and have snacks and meet with others who had participated in the trial, she said, and the research team would run a presentation, explain the results, take questions, and generally make themselves available to chat with participants about any questions or concerns they had. “Obviously everyone can’t do that,” she added, “but it was really powerful and impactful to do it.”

Ensuring Comprehension in Participants with Lower Health Literacy

Michael Wolf from the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University asked the panelists what they recommended to ensure patient comprehension among patients with lower health literacy. He said that in his experience, incorporating tools like “teach-back” helped improve participants’ comprehension and retention of information, but he added that incorporating some health literacy tools seemed like a deterrent for some participants, because it took up more of their time. He added that “no matter how good the written material is, it will not do anything for people with the lowest levels of health literacy. They are not going to utilize it.”

Trudeau agreed, adding that he believed informed consent should be a memorialization of the education that has occurred between participants and investigators, not just a transactional document to be signed. “I do think that the Common Rule revision is supporting this shift toward facilitating understanding, using teach back, and a whole planned educational process, not just the ‘consent process,’” he said.

Boulware echoed Trudeau, adding that she has often thought that investigators seem to race to get informed consent signatures, but wondered if the consent process should actually be broken up into separate pieces. She continued:

Do we need to ensure a person understands Part A before they can get to Part B and Part C? The chances of decisional regret at the end are much lower when a participant has had time to really digest what it means to participate in the study.

Retaining Participants with Lower Health Literacy

Wolf described a meta-analysis about AIDS studies, which concluded that patients with lower health literacy are “significantly more likely to not be retained, which puts a huge skew on a lot of the scientific evidence we

even know about these groups.”5 He continued, “What do we do to make sure that patients with low health literacy aren’t marginalized?”

O’Leary replied that in her previous work in community research, she worked on HIV prevention among women who used drugs. “We lost participants left and right, for a lot of reasons,” she said, but the way she and her colleagues were able to find people again was by reaching out in person, referring again to Boulware’s comments about home visits.

I would call and say, “This is Catina, I haven’t seen you in 16 months, and your information is really important to me. I want to know how you’re doing and how this worked for you. Do you mind if I drop by?” Nobody ever said no. They were always so happy when I showed up at their house; it was a really big deal that somebody cared enough to come to their house. And then they would call back for the next one. They would never miss a follow-up again after that. I kept the same number for about 14 years even after I wasn’t in the same office at Washington University, because people would call and say “I was in a study a long time ago and it was really great. I just wonder what you are all doing now.”

That effort to connect is so meaningful and transformational that I think we should figure out how to do it more. The hard part is figuring out how to build in enough funding to cover that all the way through. I think a lot of studies just don’t have the financial support to keep that going, and of course, not every interviewer can make home visits.

Staley added that, from a patient perspective, clinical trials are very specific in the sense that everyone prepares for one trial at a time. Investigators may be recruiting from the same populations but behave differently when reaching out to communities, she continued. “If there was a way for more industry collaboration around therapeutic areas or disease states where you’re working for the collective good educating the community, not only about clinical trials, but health in general, we do a better service for everyone in general.”

“Reasonable Person”

Consuelo H. Wilkins from the Meharry–Vanderbilt Alliance cautioned the panelists and workshop audience to be careful using the term “reasonable person.” She added:

___________________

5 The abstract “Exploring the Impact of Low Health Literacy on Participant Attrition in Clinical Research Studies” was authored by L. M. Curtis, A. Federman, R. O’Conor, M. Martynenko, E. Friesmema, S. Persell, and M. S. Wolf and presented by L. M. Curtis at the Health Literacy Annual Research Conference in Bethesda, Maryland, in October 2015.

For me, “reasonable person” is a phrase used from the standpoint of the people who have power and privilege. That can mean that we are missing the people who we want in our trials who don’t have power and privilege.

Trudeau agreed that Wilkins was “absolutely right,” adding it has been a concern for a long time. In the nonresearch world of consent, the “reasonable person” standard applies in about half the states in the United States, he said, but the problem is that

the standard has been developed for privileged folks, privileged judges, privileged juries. I think the health literacy community now has some research showing who “reasonable people” are, which is not necessarily privileged folks with an education and degree from a prestigious university. I hope we can expand the meaning of the term because, as a legal standard, it should apply to the majority of folks.

Health Literacy Metrics

Wilkins, along with Becky Williams from the National Library of Medicine, both asked the panelists about the right health literacy metrics for participants and trials, how to capture them, and how the goal of health-literate practices might compete with the goal of enrolling participants in a study.

Staley replied that she has explored this idea, noting that smoking cessation and weight loss programs often use 22 questions in a clinical setting to evaluate the readiness of a patient for the program. She added she has wondered why trials do not use the same types of questions before participants are in the informed consent stage,

to ensure that they are at a point where they understand what’s needed in general to participate in clinical research. I don’t think we do enough to assess the patient from that kind of perspective because there are financial implications to participating in clinical research. There’s time away from work. There is a whole host of things that the patient has to consider that are not addressed during informed consent. I’ve never seen an informed consent document that says “you need to be away from work 5 days a week for 1 hour” or “you will need to take time off from work and drive to the hospital 2 hours away.” We never really consider those kinds of questions and I think we have to focus on the participant’s context before we even get to informed consent. And the education has to be continuous.

Staley added that patient fatigue is an important consideration too. O’Leary replied that one of the golden rules of health literacy is to engage

people early and often in everything you do, and if you do that, the outcomes are different. She noted that authenticity was a part of meaningful engagement among investigators and participants, but added that it would be impossible to develop documents that were specific enough to address a participant needing to leave their job for a few hours. That, she continued, would be where the investigators come in to support the regulatory document and ensure that participants understand what they are signing up for. Regarding metrics, she said, she was not sure about the best ones for everything, but noted that even though “adherence” and “compliance” were not health-literate terms, they are often proxies for how much people understand and engage, and thus were still relevant.

Patient Portals

Collyar asked the panelists for their thoughts or experiences around the use of patient portals in trials or clinical settings.

The burden is on the patient to ensure continuity of care by carrying their medical information between clinical research and primary care providers (PCPs), said Staley, and “it’s a nightmare.” Referring to her own experience as a cancer patient, she said:

I’ve told my oncologist and PCP that they can’t retire until I do, because they know my story. I’ve made a conscious decision to stay with the same health care team because I actually feel that having the longevity that I’ve had with my oncology and primary care team has made me healthier and safer as a patient than going from one system to another. Yes, I seek out second or third opinions, and I always return to my primary care physician and my oncologist, because as long as they are the center of truth for my health care story, I feel confident in that.

But I’m the one carrying records and connecting information sets about my journey when I need to make a decision, and I think my challenge to industry is to develop a central source for the patient who wants to participate in trials that might be with different sponsors or pharmaceutical companies. If I’m on a pharma company A trial, and then enroll in a pharma company B trial, I want continuity of my clinical research journey available to the researchers, not just data points of a very specific moment in time.

How can industry build this framework to allow for seamless information exchange and allow for continuous educational processes throughout so the patients, physicians, and researchers are constantly learning and evolving?

The Importance of Building Trust and Relationships

Patty Spears from the University of North Carolina Lineberger Patient Research Advocacy Group said that she believes the paradigm of clinical trials needs to be flipped to be patient-focused, instead of trial-focused. “It’s a partnership where you build a relationship, and then you focus on what trial is best for the patient, not which trial you are pushing today,” she said. There are a lot of different people involved in this process, she continued, including patients, clinicians, and research professionals, but “the number one reason why patients enroll in clinical trials is because their physician asked them to.”

Terry C. Davis from the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center reiterated that relationships between patients and providers were important, and that includes clinical research assistants. She asked O’Leary about user reactions to the table O’Leary showed.

O’Leary replied that there were many iterations of the HLM informed consent form, starting with the original draft from Janssen. She said that HLM tested it with more than 100 people during the first round, and continued to make changes through several focus groups. “I don’t think there’s a standard application,” she added, and the graphics, tables, colors, charts, and lines will require participation to test every one, every time.

Boulware added that, as a general internist, she felt that PCPs were often left out of the clinical trials process with regard to their patients. She said that despite playing a key role in trial participants’ care, PCPs frequently have little information about the actual trials.

Boulware said that PCPs should be thoughtfully integrated into the process of clinical trials, developing an understanding of the role of the PCP, and how they can continue to help their patients throughout the trial. It was exciting to hear PCPs included in the conversation, she said, but it will be difficult in practice if they are never actually prepared to help patients with trials.

Davis added that many PCPs she had worked with were from federally qualified health centers and did not have time to search for clinical trials that would be appropriate for their patients. Many rural PCPs are unfamiliar with academic researchers, which is also a hindrance, she said. “If we want PCPs to help us [as investigators],” she said, “we’ve got to make it easy for them to find out about appropriate trials to mention to their patients. We need relationships—trust is everything.”

Assaf agreed, adding that PCPs could really benefit from having health-literate information (with brief talking points, for example) to share with patients. She also noted that a particularly delicate time for trial participants is when the results of a trial are made public; some of the results may startle participants. If PCPs are notified about these results ahead of time,

they can counsel the participants on the best decision to make for their care around stopping or changing a drug.

Lawrence G. Smith from the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell and Northwell Health added that trust between PCPs and patients is at the root of successful patient understanding and treatment, and developing that trust is an ongoing process.

O’Leary said that printed materials are a necessary supplement to a structured conversation with patients and trial participants.

Regarding the trial process and, specifically, informed consent, Staley said:

Everything is a race. We’re in a race for the patient’s signature on informed consent. We’re in a race to bring a new drug to market. We’re in a race all about speed. It’s got to be faster, and it’s got to be cheaper. It’s got to be done yesterday.

But what we’re talking about is the fact that we have to stop, take time to build relationships, and take time to process information. The system is built around speed, and making decisions in this rapid-fire mindset. It’s very hard to slow it down; it feels almost counterintuitive.

She added that there is a dichotomy between the clinical care side and the clinical research side of medicine.

If you’re focused on clinical care, your focus is to deliver care to the patient at that very moment. If you’re focused on clinical research, you’re looking at the end goal: does this therapy work or not? A patient sits in the middle and doesn’t look at it as clinical care or clinical research. They look at it as health care. They look at it as getting better or staying well.

We can go a long way in helping patients understand that there are subtle differences between the two worlds, but let’s find a way to begin building bridges that allow for the health care journey to be as seamless as possible for the patient. We’ve got the tools. We have the technology. It’s about building the relationships at this point.

Referring to Smith’s point about the process of developing trust, Trudeau said, “it made me think about the European Medicines Agency having a regulation that requires conversations for informed consent.” The conversation is not just in writing; it is a requirement that helps you build trust with participants, he added.

In terms of informed consent, he said,

we shouldn’t be thinking about this as one document, maybe “talk about the study and sign,” and then “talk about the risk and sign,” and continue

with different conversations. It might not be something you can do logistically for low-risk studies but for the really high-risk first-in-human studies, this seems like something that needs to be embedded into the culture of what we do during the educational process. And if the lawyers need signatures, that’s fine, but we’ll get them on different days.

Phyllis J. Pettit Nassi from the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute explained that part of her responsibility in her program is to do outreach to rural frontier populations, including American Indian and Alaska Native farmers, ranchers, polygamists, and Hutterites. She added that clinical trials are a component of the health education programs she runs, and they are included along a continuum of patient experiences. Pettit Nassi believes that we need to restructure how we speak about clinical trials so that people understand that trials are a part of the health care system and the patient experience. She noted that people cannot access something that they have never heard of and do not know about. She also suggested relating clinical trials to people or experiences that are familiar. She added that she often mentions former President Jimmy Carter’s participation in a clinical trial as an example of someone who is in a trial but still active and engaged with other activities.

Staley said that she would like to see the health care system move from reactive to proactive. “Every health care interaction I’ve had since I was 19 years old was reactive in nature,” she said, “from the first moment I was diagnosed with cancer. It’s been that way ever since. We can’t continue to work in this reactive mode.”

Jennifer Dillaha from the Arkansas Department of Health commented that she saw clinical trials as an opportunity to support patients toward increasing their health literacy. “It seems that a clinical trial would be a wonderful opportunity to coach patients, empower them, and develop trust, so by the time the patient finished the clinical trial, their health literacy skills would be much more robust than when they started,” she said.

Behtash Bahador from the Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation asked how professionals from academia, industry, clinical practice, and research have navigated engaging trial participants in a health-literate manner while still dealing with the operational need for expediency.

Boulware, speaking as a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded investigator, replied that she found there to be several issues around funding for such practices. Typically, she said, investigators are expected to begin enrolling participants as soon as the funding is granted, making it difficult for investigators to do any pretrial work of engaging communities and potential participants. She added that NIH Clinical Translational Science Awards (CTSA) support community engagement by providing some

financial support, but they are rather underfunded. At the Duke University Clinical & Translational Science Institute, which Boulware directs, the community engagement core is their largest, but it shares its funding with 14 other cores.6 To accommodate this type of pretrial community engagement that occurs before, during, and after a study’s standard funding timeline, Boulware continued, the entire mechanism of funding needs to change.

As a final comment from the panelists, O’Leary explained that her earlier career focused on community-engaged research. She noted that those studies had community-engagement strategies built in, so funding was structured accordingly. The broader trial industry has not picked it up, she said, but “it’s not impractical.” Wrapping up the discussion, she continued:

Advocates want to be included before a trial is even funded and to think about research questions. They want to be engaged—not just regarding the research question, but the logistics questions, as well. I think those models from community-engaged research can be more broadly utilized. It can be uncomfortable and complicated, and it is a real challenge to the scientific model as many people know and understand it. But I think it works. Investigators will have to be really thoughtful about what their intentions are and who their audience is and what their purpose is.

REFERENCES

Boulware, L. E., P. L. Ephraim, J. Ameling, L. Lewis-Boyer, H. Rabb, R. C. Greer, D. C. Crews, B. G. Jaar, P. Auguste, T. S. Purnell, J. A. Lamprea-Monteleagre, T. Olufade, L. Gimenez, C. Cook, T. Campbell, A. Woodall, H. Ramamurthi, C. A. Davenport, K. R. Choudhury, M. R. Weir, D. S. Hanes, N. Y. Wang, H. Vilme, and N. R. Powe. 2018. Effectiveness of informational decision aids and a live donor financial assistance program on pursuit of live kidney transplants in African American hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrology 19(1):107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-018-0901-x.

Boulware, L. E., P. L. Ephraim, F. Hill-Briggs, D. L. Roter, L. R. Bone, J. L. Wolff, L. Lewis-Boyer, D. M. Levine, R. C. Greer, D. C. Crews, K. A. Gudzune, M. C. Albert, H. C. Ramamurthi, J. M. Ameling, C. A. Davenport, H.-J. Lee, J. F. Pendergast, N.-Y. Wang, K. A. Carson, V. Sneed, D. J. Gayles, S. J. Flynn, D. Monroe, D. Hickman, L. Purnell, M. Simmons, A. Fisher, N. DePasquale, J. Charleston, H. J. Aboutamar, A. N. Cabacungan, and L. A. Cooper. 2020. Hypertension self-management in socially disadvantaged African Americans: The Achieving Blood Pressure Control Together (ACT) randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine 35(1):142–152. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05396-7.

GPO (U.S. Government Printing Office). 2017. Federal policy for the protection of human subjects. Federal Register 82:7149. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2017-0119/pdf/2017-01058.pdf (accessed January 25, 2020).

___________________

6 For more information about CTSA cores at Duke University’s Clinical & Translational Science Institute, see https://www.ctsi.duke.edu/about/ctsa-cores (accessed September 19, 2019).

SACHRP (Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections). 2018. Attachment C—New “key information” informed consent requirements. SACHRP, October 17, 2018. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp-committee/recommendations/attachment-c-november-13-2018/index.html (accessed September 17, 2019).

Strigo, T. S., P. L. Ephraim, I. Pounds, F. Hill-Briggs, L. Darrell, M. Ellis, D. Sudan, H. Rabb, D. Segev, N.-Y. Wang, M. Kaiser, M. Falkovic, J. F. Lebov, and L. E. Boulware. 2015. The TALKS study to improve communication, logistical, and financial barriers to live donor kidney transplantation in African Americans: Protocol of a randomized clinical trial. BMC Nephrology 16(160). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-015-0153-y.

Trunomi and CommVault. 2018. GPDR FAQs. https://eugdpr.org/the-regulation/gdpr-faqs (accessed September 17, 2019).

This page intentionally left blank.