2

Scope of the Problem

This chapter provides an overview of the relationship between infectious diseases and opioid use disorder (OUD). It also summarizes current policies at the national level to end these concurrent epidemics and describes the history of the dissociation between substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, primary care, and infectious disease care.

THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN OPIOID USE DISORDER AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES

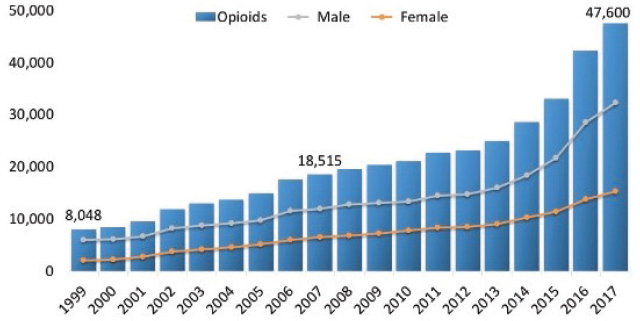

More than two decades into the opioid epidemic, the United States continues to battle this critical public health challenge (Kolodny et al., 2015). According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2.1 million people in the United States have OUD (NIDA, 2018a). In 2016, it was estimated that only 20 percent of them received treatment (SAMHSA, 2016). Furthermore, opioid-related deaths remain high: 47,600 deaths in 2017 (see Figure 2-1) and more than 700,000 since 1999 (CDC, 2018a). These data confirm that there is an urgent need to link and engage persons with OUD to evidence-based treatment. In particular, this means medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), which are highly effective at treating OUD and preventing complications, including overdose death and highly morbid drug-related infections (NASEM, 2019).

Recent reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describe an increasingly complex epidemic in the United States (CDC, 2018a). OUD and the related complications of overdose and

SOURCE: NIDA, 2019, via CDC WONDER.

infectious diseases have long ravaged inner cities and continue to do so. More recently, rural and southern states have also been devastated by the opioid epidemic (Dowell et al., 2016; Joudrey et al., 2019). On average, rural populations are older, poorer, and sicker compared to urban populations (though significant disparities in some cities remain) (NACRHHS, 2015). Many rural regions also have higher opioid prescribing rates. In 2017, residents of Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Tennessee received more than 80 opioid prescriptions per 100 residents (CDC, 2017); the national average was 58.7 per 100 residents. Appalachian states continue to have the highest rate of opioid-related emergency department and hospital admission rates (AHRQ, 2016). From 1999 to 2015, opioid-related deaths in young rural people (18–25 years old) quadrupled; deaths among women tripled (Noonan, 2017). Yet, new data show that overdose deaths are highest in urban areas, at least in part due to an influx of highly lethal, illicitly manufactured fentanyl. In recent years, surprisingly high rates of overdose deaths have migrated west of the Mississippi: Arizona, California, Colorado, Minnesota, Missouri, Oregon, Texas, and Washington are experiencing a sharp increase (CDC, 2018a). In sum, no part of the country has been spared from the devastating health consequences of opioid use, and it will take specific, tailored interventions to treat OUD in these varied demographic regions.

In addition to the suffering caused by OUD alone, increased drug use has brought about a resurgence of infectious diseases. Some infections are directly attributed to drug injection. For example, the incidence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is approximately 1.8 percent for needle-stick exposures (CDC, 2003). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) incidence is

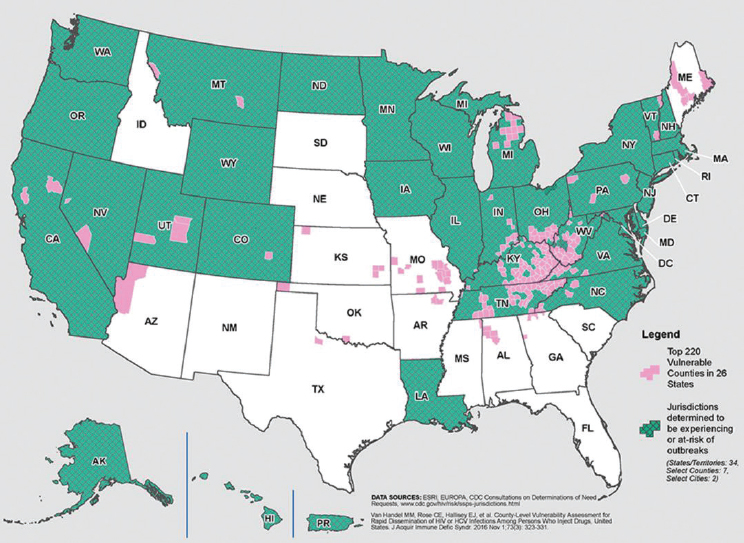

significantly lower: an estimated 23 infections for every 10,000 needle-stick exposures and 63 for every 10,000 needle-sharing exposures (CDC, 2019e). Importantly, the risk of transmitting the virus is highest when an individual is acutely infected but before developing antibodies (CDC, 2015b; Conry-Cantilena et al., 1996; Gerberding, 1994). Despite hepatitis B virus (HBV) being even more transmissible by needle-stick exposure, the population risk of HBV is lower than for HCV because fewer persons are chronically infected with HBV. The roll-out of childhood vaccination for HBV in the 1990s also contributed to this decline in prevalence (Meireles et al., 2015). Unsafe injections also increase the risk of bacterial infections such as staphylococcal skin infections or endocarditis (Wurcel et al., 2016). In addition, OUD increases the risks of other infectious diseases, such as sexually transmitted infections spread through high-risk sexual behaviors in exchange for drugs and/or money and HAV linked to poor sanitary conditions (Hartard et al., 2019; Villano et al., 1997). Infectious disease clusters and outbreaks in recent years include blood-borne diseases, such as HIV and viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis (Brookmeyer et al., 2019). In addition, bacterial and fungal bloodstream infections, heart infections, and skin, bone, and joint infections are increasingly recognized as a common cause of health care use and mortality in persons who inject opioids (Wurcel et al., 2016). As an example of the connection between OUD and infectious diseases, Figure 2-2 provides a snapshot of the increases in HIV attributed to injection drug use across the United States.

Although great strides have been made in recognizing and treating OUD, several notable inequities remain when it comes to access to SUD treatment. Service availability, including residential, rehabilitation programs, intensive inpatient care, and OUD services in primary care or through local health departments is limited in rural areas and for vulnerable populations (Browne et al., 2016; Cole et al., 2019; McLuckie et al., 2019; Priester et al., 2016). Services are also limited for homeless, criminal-justice-involved, and uninsured patients. Barriers to SUD treatment are most obvious in states without Medicaid expansion, as poverty precludes linkage to and retention in SUD treatment (Priester et al., 2016).1 These same barriers apply to access to infectious disease treatment and prevention (McLuckie et al., 2019). Thus, patients who are poor, homeless, or rural and those with a history of incarceration may receive little to no care for SUD and/or infection-related complications (Dean et al., 2018).

___________________

1 Between 2011 and 2018, prescribing of buprenorphine in Medicaid expansion states has steadily increased, from 1.3 million annual prescriptions in 2011 to 6.2 million in 2018. In contrast, annual prescriptions in states that have not expanded Medicaid have remained at 0.5 million or lower over the same time (Clemans-Cope et al., 2019).

SOURCE: CDC, 2018b.

NATIONAL RESPONSE TO HIV AND THE RYAN WHITE CARE ACT

More than 30 years ago, the country confronted the beginnings of the HIV epidemic. As cases grew and care was deemed fragmented, specific funding was needed. In response, Congress passed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources (CARE) Act on August 18, 1990 (Pub. L. No. 101-381), to provide funding to cities, counties, states, and local community-based organizations to offer a comprehensive system of HIV primary medical care, support services, and antiretroviral medication. The CARE Act has been the payer of last resort to provide care for un- and under-insured persons living with HIV, especially in Medicaid non-expansion states. It also supported other behavioral support services, such as mental health care, SUD treatment, and housing assistance, all of which greatly improved HIV care (Cheever, 2016).

To monitor HIV care outcomes at a population level, in 2011, the HIV care continuum was proposed (see Figure 2-3). It includes essential,

SOURCE: HHS, 2016. Used with permission from HIV.gov.

easy-to-measure or -estimate outcomes for persons living with HIV. These include the percentage of persons living with HIV in a given population that are diagnosed, linked to HIV care, starting antiretroviral therapy (ART), and achieving HIV viral suppression. The ultimate goal of the HIV care continuum is sustained viral suppression, as it is linked with reduced individual morbidity and mortality and reduced transmission. Thus, the HIV care continuum shows the proportion of persons living with HIV who are engaged at each stage and allows public health officials and policy makers to measure progress and direct HIV resources most effectively. Several randomized controlled trials (e.g., HIV Prevention Trials Network and PARTNER studies) showed no linked transmission in both same- and opposite-sex serodiscordant couples when the person living with HIV is virally suppressed (Bavinton et al., 2018; Cohen, 2019; Cohen et al., 2016; Rodger et al., 2016, 2019; Safren et al., 2015). Thus, sustaining and maintaining viral suppression means improved length of life for persons living with HIV and decreased transmission to others. These findings underscore the importance of supporting effective interventions for people living with HIV to admit them into care, retain them in care, and help them adhere to ART in order to achieve viral suppression.

Since the introduction of the CARE Act, the United States has made great progress toward ending HIV/AIDS (Cheever, 2016). This includes expanding HIV testing and treatment through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the AIDS Drug Assistance Program, ground-breaking research by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and CDC, and the introduction of HIV PrEP. From 2010 to 2017, viral suppression increased from 69.5 percent to 85.9 percent, and racial/ethnic and regional disparities have decreased (HRSA, 2018). In 2010, the annual number of Americans diagnosed with HIV was more than 41,000. In 2018, this number had dropped to 37,832 (CDC, 2019b).

Still, the annual incidence of HIV infection has increased in some regions and groups. The highest rates of incident HIV are concentrated in the South, where there are 15.7 cases per 100,000 people, compared to the Northeast at 10.0, the West at 9.3, and the Midwest at 7.2. African American and Hispanic/Latino men who have sex with men and African American women bear a disproportionate number of incident HIV cases (CDC, 2015a). Although African Americans account for only 13 percent of the U.S. population, they made up 43 percent of HIV cases in 2017. Subsequent revisions to the national HIV/AIDS strategy over the past decade have emphasized strategies to end transmission in racial/ethnic and gender minorities along with efforts to reduce stigma. For example, PrEP campaigns are targeting young African American men who have sex with men in HIV high-incidence areas, such as the South, and the Department of Justice and CDC have worked together to reform HIV-specific criminal laws (CDC, 2019c). Importantly, substance use exacerbates HIV risk and is correlated with lower overall engagement in the HIV care continuum among both Latinx and African American men who have sex with men in many regions of the country (Jin et al., 2018; Nerlander et al., 2017). While progress has clearly been made to reduce the incidence of HIV and its associated harms, there is still significant work to be done. In 2019, the Trump administration proposed a strategy titled “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America,” which has the goal of reducing incidence by 75 percent in 5 years and 90 percent in 10 years (HHS, 2019c).

NATIONAL OPIOID POLICY AND STRATEGY

The committee anticipates similar challenges to ending the opioid epidemic. Like HIV, OUD is a chronic disease that is not curable but can be effectively managed with daily medication (NASEM, 2019). Evidence-based treatment of OUD also requires treatment adherence, engagement in medical care, and support of comorbidities including mental health conditions and infectious diseases. OUD is associated with stigma. This may lead to shame and a disincentive for patients to seek medical attention, or limit the number of providers who are willing and trained to provide OUD treatment (Kepple et al., 2019). As a result, high-risk behaviors, such as unsafe syringe sharing and sexual practices, that are amenable to harm reduction continue to contribute to the morbidity and mortality of the opioid epidemic (Jones, 2019). The criminalization of OUD may represent an additional barrier to treatment and harm reduction, reminiscent of the criminalization of HIV. The infectious disease consequences of OUD-related stigma are most evident in rural and southern states, such as in Appalachia (CDC, 2018b). With limited health care infrastructure and resources, OUD has concentrated in these poor areas of the country, much like HIV high-incidence areas in the Deep South (CDC, 2019d).

Faced with rising numbers of overdose deaths and recent outbreaks of HIV and viral hepatitis, President Trump declared the opioid epidemic a public health emergency in 2017 (Haffajee and Frank, 2018; White House, 2019). Since that time, clinicians, researchers, and policy makers have begun to disseminate evidence-based strategies. In 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) outlined a five-step action plan, including improved access to OUD treatment and prevention, better surveillance data related to OUD and overdose, improved pain management strategies, optimized delivery of naloxone to high-risk populations and those who could administer it, and cutting-edge research on pain and substance use (Azar and Giroir, 2018). To advance initiatives around treatment, prevention, and recovery services and expand access to Medicaid beneficiaries, the agency issued more than $800 million in grants. In fiscal years 2016 to 2018, Congress approved HHS funds to support syringe service programs under certain circumstances (CDC, 2019a). Among the stipulations are restrictions on the use of funds to purchase syringes and a requirement that CDC determine the regional need for syringe service programs. CDC’s needs assessment includes local patterns of HIV and HCV transmission and public health concerns in people who inject drugs. In 2018, the president signed into law the Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act (Pub. L. No. 115-271), which includes $40 million per year in funding to enhance monitoring of infectious diseases related to opioid use and increase testing and treatment for HIV, HCV, and other infectious diseases (Canzater and Crowley, 2019).

In 2019, CDC released “Evidence-Based Strategies for Preventing Opioid Overdose: What’s Working in the United States,” which outlines several strategies, including expanding access to harm reduction (CDC, 2019f; Haffajee and Frank, 2018). Specifically, CDC identifies increasing access to naloxone, MOUD, and sterile syringes. In particular, syringe service programs for community-based provision of sterile syringes and injection equipment, vaccination, and testing are noted as important linkages to OUD treatment (Carroll et al., 2018a). An additional strategy is the recognition and response to missed opportunities for MOUD in criminal justice settings, recent release, and emergency departments.2 CDC also highlights opportunities to prevent OUD, including safer opioid prescribing practices (Carroll et al., 2018a).

A crucial prong in reducing the harm associated with opioid use is MOUD. The evidence in support of MOUD is strong (NASEM, 2019). The

___________________

2 While this report primarily focuses on outpatient care settings, care for opioid use disorder and infectious diseases can be improved at many points along the health care system, including emergency departments, health care clinics, opioid treatment programs, and other settings.

World Health Organization (WHO) added methadone and buprenorphine to its list of essential medicines (WHO, 2004). WHO cited several systematic reviews as evidence of methadone’s effectiveness in increasing retention in treatment, reduction in opioid use and criminality, reduction in injection drug use and infectious disease incidence, and increase in adherence to treatment for HIV. Buprenorphine has not been studied as extensively as methadone, but WHO’s review of the evidence showed that it is as effective as methadone in reducing opioid use and retaining patients in treatment. MOUD’s effectiveness is contingent upon adequate dosing, and, in the case of methadone, staff attitudes that stigmatize and degrade participants result in poorer outcomes (Uchtenhagen, 2013).

As part of the national response to the opioid crisis, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has developed recommendations based on the prevalence and public health impact of OUD and infectious diseases, specifically HCV. First, in 2019, USPSTF created a draft statement that all adults 18 years and older should be screened for illicit drug use (USPSTF, 2019b). Furthermore, based on rising rates of HCV—especially in young adults—and the existing guideline to screen persons born between 1945 and 1965, HCV testing is now recommended for all adults ages 18–79 (USPSTF, 2019a).

The above strategies all promote harm reduction, which is effective for not just opioid use but also substance use more broadly. Notably, the United States is facing a syndemic of methamphetamine and cocaine use, which are often combined with opioids (Ellis et al., 2018). However, there is no effective pharmacotherapy for reducing methamphetamine use. Thus, harm reduction—such as sterile syringe provision and HIV and viral hepatitis prevention and treatment—is one of the few ways to minimize the public health consequences of methamphetamine use. Methamphetamine also affects rural regions already lacking in access to medical care (Ellis et al., 2018). Pursuant to the committee’s Statement of Task, this report focuses in particular on OUD, yet the link between methamphetamine (or poly-drug use) and infectious diseases is another important area of consideration.

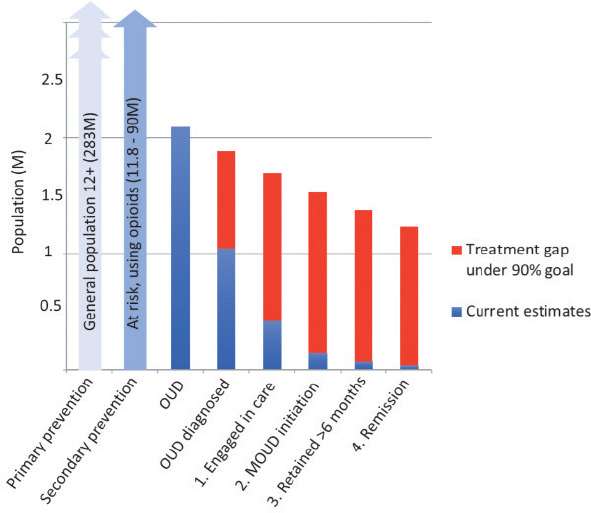

Because of the chronicity of OUD and the many parallels with HIV, including complex barriers to care, researchers are beginning to report OUD outcomes in a cascade (Perlman and Jordan, 2017; Williams et al., 2017, 2019). Although a range of outcomes have been included in recently reported cascade models, most include identification of OUD, linkage to MOUD, and retention in treatment over time. Modeled after the original HIV care continuum frameworks (Gardner et al., 2011), the OUD care cascade provides a set of outcomes that are easily measurable and it allows providers, policy makers, and researchers to examine how various policy initiatives impact treatment, retention, and recovery. Figure 2-4

SOURCE: Williams et al., 2019. Reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis Ltd., http://www.tandfonline.com).

shows an example of this care cascade, illustrating the significant gaps in care at each level of the process. This model is linked to the Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) program, developed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) with the goal of identifying individuals with SUD and immediately engaging them in care across health care settings (Babor et al., 2007). SBIRT has been shown to be effective in reducing illicit drug use and criminal behaviors, as well as improving patients’ general health, mental health, employment, and housing status (Madras et al., 2009).

Much like HIV, a range of support services is needed to manage OUD along with comorbid psychiatric and SUD (e.g., methamphetamine use disorder), as well as the social determinants of health (e.g., housing instability, criminal justice involvement). With proper funding and support, ancillary services can be provided alongside medical services in primary care and subspecialty clinics. For example, for persons living with HIV, OUD treatment can be integrated into routine HIV care (TARGET, 2019), and linkages to housing or legal service can be provided. In this way, the OUD care cascade and the HIV care continuum can be used in tandem, given the comorbidity of these two illnesses. The same can be true for those with comorbid OUD and viral hepatitis or other chronic infectious diseases.

DISSOCIATION OF SUBSTANCE USE TREATMENT FROM PRIMARY CARE AND INFECTIOUS DISEASE TREATMENT

Along with the criminalization of substance use, there has historically been a dissociation of SUD treatment from primary care, including care for some infectious diseases. For much of the 20th century, policy related to drug use was divorced from the realm of public health, instead existing in the criminal justice sphere (Mosher and Yanagisako, 1991); between 1980 and 2001, the number of individuals in state and federal prisons for drug-related offenses increased about 13-fold (Jensen et al., 2004). Dating to the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914 and before, antidrug policies and stigmatization have shaped the policy and legal landscape surrounding drug use up until today (Redford and Powell, 2016).

In the modern era, a majority of SUD treatment services are provided in specialized, free standing clinics, many of which are operated by nonprofits or government-owned programs (Buck, 2011). As of 2015, it was common that SUD treatment programs could not bill any type of insurance, public or private (Andrews et al., 2015). SUD treatment services have relied heavily on state and local government sources. Because of these unique stipulations, public SUD treatment services have historically developed and functioned independently of the overall health care system. As a result, there are a number of programs in operation that lack a significant evidence base. Therapeutic communities (such as Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous) are a mainstay of abstinence-based treatment but are characterized by high drop-out rates (between 44 and 91 percent), and relapse after treatment is common (Malivert et al., 2012; Uchtenhagen, 2013). Detoxification is the standard at many SUD treatment centers, despite the fact that treatment after detoxification is typically a medical imperative (NCASA, 2012). In addition, SUD treatment providers in nonmedical settings are not subject to the same regulatory oversight as other health care providers, and often are under less scrutiny to abide by evidence-based practices (NCASA, 2017).

Yet, because the ACA requires parity for mental health services and SUD treatment, policies regarding funding and delivery of care are changing (Maclean and Saloner, 2019; Saloner et al., 2018). For example, mental health and SUD treatment are now essential benefits, and copayments are now similar to other medical benefits (Buck, 2011). These provisions apply to adults and children and could significantly change how SUD care is delivered. Namely, as SUD is viewed and funded in a manner analogous to other chronic diseases, there is greater potential to integrate treatment into routine care in general medical settings (Wang et al., 2006).

Still, there is currently a significant shortage of clinicians pursuing training in addiction medicine relative to the national need (Rasyidi et al., 2012). Those who desire to provide SUD treatment services must receive

specialized training and certification to prescribe SUD medications, such as methadone and buprenorphine, which may further deter providers. In another example of the historical dissociation of medical care and SUD care, methadone may only be prescribed for OUD at an opioid treatment program authorized by SAMHSA (2019e). As of 2018, eight state Medicaid programs did not reimburse for methadone for OUD, and it cannot be prescribed in a primary care setting for OUD (Samet et al., 2018). This is despite the fact that four decades of research support methadone as an effective treatment for OUD (SAMHSA, 2018a). Similarly, fewer than 70 percent of state Medicaid programs reimbursed for implantable or extended-release buprenorphine, illustrating the disconnect between SUD care and medical care (SAMHSA, 2018a). Before the implementation of the ACA, many health insurers offered little to no benefits for SUD treatment. As a result, even in areas with adequate primary care services, there remained an SUD treatment gap (O’Connor et al., 2014). More recently, evidence has demonstrated that increased access to insurance via Medicaid expansion has resulted in increased uptake of SUD treatment services paid for by Medicaid (Mojtabai et al., 2018). Private insurers vary widely in their coverage of SUD treatment (Tran Smith et al., 2018). To shed light on integrating OUD care and medical care for infectious diseases, the following chapters outline current barriers to integration and strategies for overcoming these barriers.

This page intentionally left blank.