3

Policy-Relevant Evidence for Population Health: Promise and Challenges

The second panel of the symposium considered the complexity of policy implementation with attention to mitigating negative unintended consequences for population health. Sandro Galea, dean and the Robert A. Knox Professor in the School of Public Health at Boston University, discussed four key challenges to generating the evidence needed to inform population health initiatives. Paula Lantz, associate dean for academic affairs and professor of public policy at the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan, discussed current definitions of population health and population health management, and the importance of targeting policy efforts upstream to address the fundamental drivers of population health inequities. Jennifer Doleac, associate professor of economics at Texas A&M University and director of the Justice Tech Lab, described ban-the-box policies and policies that increased access to naloxone as examples of how policy interventions can have unintended consequences. The panel was moderated by Allison Aiello, professor of epidemiology at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina. Highlights of this session are presented in Box 3-1.

CREATING POLICY-RELEVANT EVIDENCE

“There is a long tradition of population health interventions,” Galea began. He briefly described an early intervention, a population-wide experiment done in the 1970s and 1980s in Finland, which took a population-level approach to lowering cholesterol and thereby lowering

mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD). As experiments in population health continue, there are challenges to generating policy-relevant evidence. Before discussing the challenges, he emphasized that there is an existing body of evidence to support population health interventions. As an example, he referred participants to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Health Impact in 5 Years (HI-5) website, which is a repository of data from numerous current population health interventions.1 He also drew attention to a recent report from the Yale Global Health Leadership Institute that summarizes the current state of evidence on the social determinants of health.2 Galea then described four key challenges to generating the evidence that is needed to inform population health initiatives: external validity, ubiquitous factors, thinking in dichotomies, and making predictions.

___________________

1 For more information about CDC’s HI-5 initiative, see https://www.cdc.gov/policy/hst/hi5/interventions/index.html (accessed December 23, 2020). The HI-5 initiative “highlights nonclinical, community-wide approaches that have evidence reporting (1) positive health impacts, (2) results within 5 years, and (3) cost-effectiveness and/or cost savings over the lifetime of the population or earlier.”

2 See https://bluecrossmafoundation.org/sites/default/files/download/publication/Social_Equity_Report_Final.pdf (accessed December 23, 2020).

External Validity

The first challenge to generating policy-relevant evidence is the external validity of the intervention. Epidemiology has long favored internal validity over external validity, Galea said, but external validity is important when looking to implement evidence-based solutions to population health problems.

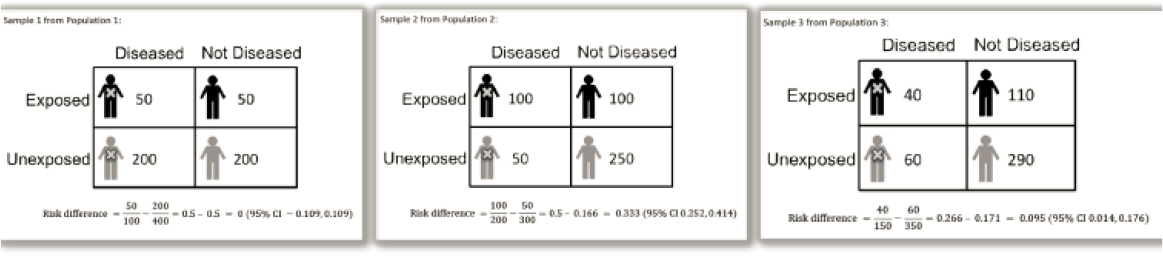

As an example of why external validity matters, Galea described a hypothetical study to determine if a particular intervention results in normal blood pressure levels (see Figure 3-1).3 A population is selected and individuals are sorted to one of four subgroups: diseased and exposed to the intervention; diseased and unexposed to the intervention; not diseased and exposed; and not diseased and unexposed.

The first population studied has a risk difference of zero (i.e., there is no association between normotension and the intervention). A second population is sampled, and a risk difference of 0.33 is calculated (i.e., 33 additional cases of normotension for every 100 cases that receive the intervention). A third population is then studied, and the risk difference is calculated to be 0.10 (i.e., 10 additional cases of normotension for every 100 cases that get the intervention).

It is not uncommon for different samples to have different results, Galea said; there could be issues with the internal validity of the study (e.g., design flaws). However, different results are often related to the external validity of the study. The intervention alone does not result in normotension, Galea said. Rather, “the intervention needs to happen together with exposure to other conditions.” He explained that a basic principle of epidemiology is that two causes of an outcome might both be necessary, but individually insufficient. This is why the different samples resulted in different outcomes. In this example, one cause is the intervention being applied. The other cause is often a population-wide factor or social condition that is not being measured. Neither alone results in normotension. Galea explained further that in the first population sample the social condition was absent, and no one developed normotension from the intervention as the other factor was absent. In the second and third population samples, 50 percent and 40 percent, respectively, had the social condition, and correspondingly achieved normotension.

In summary, Galea said, it is plausible to assume that there are co-occurring causes. The association between the intervention and the health outcome can only be understood by also understanding the other factors that influence the outcome, and how they vary across samples.

___________________

3 For full details see Keyes and Galea (2014).

SOURCE: Galea presentation, October 3, 2018.

Ubiquitous Factors

Populations are affected by the social forces that surround them. As they are ever present, it is easy to forget about these ubiquitous forces when designing studies, noted Galea. He listed several examples, including racism, gender inequity, income inequality, and lack of social cohesion. These factors can be difficult to see and difficult to measure, he said.

As an example of the errors that can happen when ubiquitous factors are ignored, Galea reminded participants of the early coverage of the risks of gestational crack cocaine in the 1980s. Despite early conclusions to the contrary, it later became clear that there was no difference in cognitive functioning between children exposed to crack cocaine in utero and children who were not exposed, Galea explained (Betancourt et al., 2011). The differences in cognitive functioning were likely caused by different levels of environmental stimulation. Many of the mothers who used cocaine while pregnant were also deeply poor, Galea noted, and poverty was a ubiquitous factor for these children that was not considered.

As another example, Galea asked participants to consider the extent to which one’s cognitive ability is determined by one’s genes versus being raised in a positive environment. He described a population in which some people have a gene for being “smart” (which might or might not manifest), some people are raised in an environment that fosters intellect (and they might or might not become smart), and some people happen to be smart despite lacking the genes or environment. He illustrated two scenarios that demonstrated that, when genes and environment both contribute to cognitive ability, it is not possible to determine what proportion of intellect is attributable to one’s genes unless details about their environment are also known.

Thinking in Dichotomies

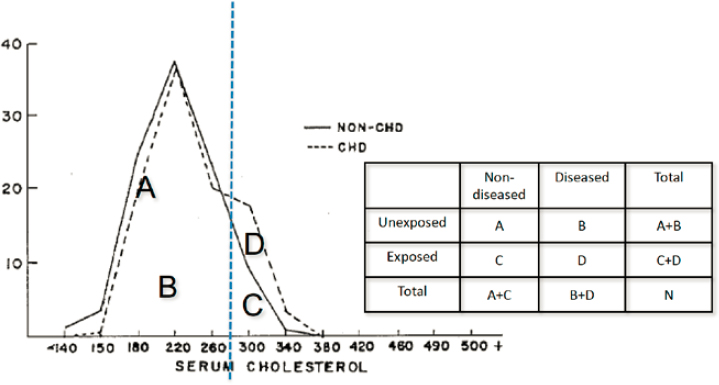

People “are used to thinking in dichotomies,” Galea said, such as thinking in terms of disease versus no disease. He cautioned against thinking in dichotomies. To illustrate, he shared cholesterol data from the Framingham Study. (The study developed a CHD risk formula on the premise that high cholesterol increases risk.) As a result of the study, cholesterol screening is commonly done for many people, and actions are prescribed for those predicted to be at high risk (e.g., drugs, exercise). The Framingham data on serum cholesterol for people who do and do not develop CHD look quite similar (see Figure 3-2). Although one might wonder if the data or the risk equation are wrong, Galea explained that such confusion is because defining (high) cholesterol as a risk factor is dichotomizing. When the data curves are viewed relative to individuals who are diseased or nondiseased and exposed or unexposed, it becomes clear that exposure

SOURCES: Galea presentation, October 3, 2018; adapted from Rose, 2001, Figure 3. Geoffrey Rose’s seminal 1985 paper Sick Individuals and Sick Populations examined the difference between interventions for individuals versus populations, explaining the greater benefits of preventive interventions at the population level (Rose, 2001).

to high cholesterol is a risk factor for CHD (see populations C and D in Figure 3-2). “A population health intervention approach should focus on shifting population curves,” Galea said, but relative risk measures do not provide population level differentiation and curve separation (Pepe et al., 2004).

Making Predictions

Populations are complex systems that frequently behave in unpredictable ways, making it difficult to make predictions in population health, Galea said. He illustrated this by using another example from the Framingham Study. When genotype scores for diabetes (calculated based on 18 risk alelles) are plotted against the cumulative incidence of diabetes, it is clear that a higher genotype score is associated with a greater risk of developing diabetes (Meigs et al., 2008). Seeing this might make a person wonder what his or her genotype score is, Galea said. Galea then shared another graph from the same publication that compares genotype scores of those with diabetes and those without (genotype score versus percentage of subjects) in which the overlaid curves of those with and without

diabetes are quite similar. “The distinction at the population level is not usefully predictive of who will have diabetes or not,” Galea said. He elaborated on the mathematical limitations of prediction, cautioning that genetic prediction does not necessarily lead to disease prediction.

In studying the predictive capacity of particular genes, Galea and colleagues took into account the prevalence of genetic factors and the level of presence of environmental conditions (Keyes et al., 2015). They found that, at every level of gene prevalence, “the risk ratio ultimately is driven not by the gene itself, but by the environment, and by the likelihood of particular factors such as the background rate of disease.” Specifically, “the risk ratio increases as the prevalence of the environmental factor increases,” and “the risk ratio decreases as the background rate of disease increases.” The forces are ubiquitous, he said, and shifting a ubiquitous factor leads to a shift in the population’s health.

Principles of Population Health Science

In closing, Galea explained that these four challenges to creating evidence to inform population health policy fit into a larger set of principles of population health science (Keyes and Galea, 2016; see Box 3-2). Popu-

lations are complex, and in generating evidence for population health policy there are few simple solutions, he concluded. There have been successful population-based interventions, he reiterated, and there is evidence to support interventions that work. The challenges to generating the evidence must be met to be able to address the population health challenges described by Crimmins and Williams.

THE IMPERATIVE TO STAY UPSTREAM

Lantz began her presentation by referring to how Kindig and Stoddart (2003) define population health as health outcomes and their distribution within a population as being influenced by patterns of determinants over the life course. These determinants and outcomes are shaped by policies and interventions at both the individual and societal levels. There are many models of health determinants, Lantz said. The social ecological model of health determinants, for example, considers the factors that influence health and health equity from upstream to downstream, spanning the individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy levels. The World Health Organization conceptual framework for social determinants of health also shows the upstream structural determinants (e.g., the social and public policies that influence socioeconomic position).4

Interest in the social causes of health spans centuries, and Lantz shared a quote from Johan Peter Frank in a book published in 1790: “The diseases caused by the poverty of the people and by the lack of all goods of life are exceedingly numerous.” She suggested that the term population health really gained traction in 2007 with the development of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim framework. The Triple Aim calls for concurrent attention to improving patient care (i.e., quality), improving the health of the population, and reducing the per capita costs of care (Berwick et al., 2008).

There is a conflation of the fields of population health, public health, preventive medicine, population medicine, population health management, precision medicine, and precision public health, Lantz said, and those working in these fields often define and use these terms in different ways. Lantz said that a cursory search identified 63 institutes of higher education in the United States with degree programs, departments, or colleges of population health, population medicine, or population health management, each using the terms differently. Although different institutions have different definitions of population health and population health management, there are common themes, Lantz continued, includ-

___________________

4 See http://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf (accessed December 23, 2020).

ing the concepts of public health and community engagement. Other themes include training and workforce issues, research, and services and products.

Lantz raised the concern that population health has become medicalized as population health management. She defined medicalization as a “process by which nonmedical, social issues become viewed as medical problems or individual pathologies.” This medicalization is concerning because it shifts the focus of population health from health toward sickness, and it moves population health management downstream toward the individual level. Population health management is growing into a big business, she said, with an interest in providing services and products at the patient level. An Internet search of the phrase “population health management” returns a list of consulting groups and companies offering products and services that health care organizations and providers can purchase to better manage the health of the population they serve. In this regard, she raised concerns that the focus of research, interventions, and policy are also moving downstream to the individual level.

Shifting the focus of population health management to outcomes and individuals has implications for population health research and policy, Lantz said. One issue is denominator shrinkage as data are collected from smaller and smaller groups. There is also conflation of population health and population health management, and of health inequities and health care inequities. The framing of research problems, the targets of policies and interventions, and allocation of resources all move downstream. As such, macrolevel factors (including policy) that lead to population health issues and disparities are ignored. This is particularly concerning because, Lantz said, “When downstream efforts do not solve the problem, it reinforces notions that marginalized and disenfranchised subpopulations and their problems are intractable.”

There is currently a lot of interest in screening patients for social determinants of health. Health systems, community health centers, and others are asking patients about their job status and whether they have a steady source of income, if they have concerns about paying their utility bills, and whether they feel unsafe in their home or neighborhood. On one hand, Lantz said, understanding the social situations and contexts of their patients can help clinicians provide better care. On the other hand, such screening can detect exposures and conditions that are beyond the resources of clinical care. Screening without the capacity to refer to appropriate interventions is ineffective, and may in some ways be unethical, Lantz said, as it “could create a lot of unfulfilled expectations and further mistrust of the health care system.”

Another current area of research is identifying superutilizers of health care (e.g., the 5 percent of patients who account for more than half of

health care costs) and applying interventions upstream to keep them healthier and reduce their need for services. Lantz emphasized the need for high-quality research in this area to fully understand the effects of the interventions. As superutilizers are extreme outliers, it is challenging to determine if improvement (reduction in service utilization) is attributable to the intervention being tested or whether it is simply the result of statistical regression toward the mean.

In closing, Lantz repeated her earlier statement that the health care system cannot solve the fundamental structural and social drivers of health inequities, and she summarized some of the major challenges. As discussed by Crimmins, life expectancy in the United States ranks 36th in the world and is declining. Forty percent of children in the United States live in poverty. Social and racial disparities persist in educational attainment and wealth. Mental health concerns and suicide rates are high among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and/or questioning youth and adults. Expanding on the Kindig and Stoddart definition, Lantz suggested that population health is the “physical, mental, and social well-being in an entire population.” A life-course approach is needed to better understand the drivers of health and health inequities, and interventions are needed both downstream and upstream. She acknowledged that working upstream, where the fundamental drivers of social and health inequities stem from, is much more challenging.

POLICY EVALUATION AND THE RISK OF UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Despite the best of intentions, there are often unintended consequences of policy interventions. Doleac discussed two examples: the ban-the-box policies and the efforts to broaden access to naloxone.

Ban-the-Box Policies

Ban-the-box policies are intended to help individuals with criminal records obtain employment. Specifically, the policies prohibit employers from asking about an applicant’s criminal record until later in the hiring process (i.e., the policies ban including a box to check on a job application if one has a criminal history). Doleac noted that cities, counties, and states across the country have implemented ban-the-box policies.

A key issue with ban-the-box policies is that they do not address employers’ concerns about hiring people with criminal records. When unable to ask directly on the application, employers who are reluctant to hire people with criminal records might resort to guessing, Doleac said. There are large racial disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system, she

noted, and employers attempting to guess which applicants have a criminal record might simply avoid interviewing and hiring applicants from groups more likely to have recent convictions (e.g., young black men). “This policy then has the potential to effectively broaden discrimination to the entire group rather than reducing it,” Doleac said. This potential consequence was raised by economists when ban-the-box policies were first proposed, she added, but the counter argument given was that racial discrimination is illegal (i.e., people would not engage in illegal conduct).

Doleac described two recent studies investigating the effect of ban-the-box policies. Agan and Starr (2018) submitted thousands of job applications from fictitious applicants of various races and criminal histories before and after ban-the-box policies were implemented in New Jersey and New York City. They found that before the policies were implemented, applicants with criminal histories were called back at much lower rates than those with no criminal history, but the racial gap between black and white applicants in both groups was small. After implementation of policies, they observed a six-fold increase in racial disparities in applicant callbacks. These data suggest that, in the absence of the criminal history checkbox, employers were using information on race as a proxy for the likelihood of having a criminal record, Doleac said. She noted that because the applicants were fictitious and the study only looked at callback rates, it is also important to understand the real-world consequences of ban-the-box policies on racial disparities in employment.

A study by Doleac and Hanson took advantage of the gradual roll-out of ban-the-box policies as a natural experiment that allowed them to measure those real-world effects.5 They found that implementation of the policies reduced the probability of employment for young black men by 3.4 percentage points (5.1 percent). She added that the effect increases over time (i.e., it is not a short-term blip attributable to implementing the new policy). This is potentially “a major, long-term effect on employment for a group that was already struggling in the labor market,” she said.

Broadening Naloxone Access

Opioid-related mortality has increased across the United States, Doleac said, and many states have broadened access to the opioid antagonist, naloxone, in an attempt to mitigate the deadly consequences of opioid abuse. There are a range of approaches to expanding access, from standing orders that allow a pharmacy to dispense without a patient having a prescription to distribution by community groups.

___________________

5 A preprint is available at http://jenniferdoleac.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Doleac_Hansen_JOLE_preprint.pdf (accessed December 23, 2020).

Evidence from the field of economics has shown that a reduction in the risk associated with a particular behavior can lead to an increase in that behavior, Doleac said. A classic example is the relationship between the implementation of seatbelts in vehicles and an increase in unsafe driving (as drivers felt they were now less likely to die if they had an accident). There are also studies that suggest that the availability of life-saving HIV medication was associated with increased risky sexual practices and the incidence of other sexually transmitted diseases. These moral hazard effects can counter some of the beneficial effects that are intended from these policies, she said.

In Doleac’s study of laws that gave broader access to naloxone, her and her coauthor’s research suggests that the laws may have made people more likely to abuse opioid drugs or to use more potent opioids (e.g., fentanyl). Doleac also raised concerns that people might be less careful about the source or the content of the heroin they use, potentially resulting in more overdose deaths instead of fewer.

Similar to the design of the ban-the-box study, Doleac and her colleagues made use of the gradual implementation of naloxone access laws across the United States to measure the effects of the policies on a set of outcomes related to opioid abuse. She noted that outcomes such as mortality and emergency department admissions are readily measurable, but it is more challenging to develop a picture of changes in risky use of opioids. She shared data from the Midwest that shows that opioid- and fentanyl-related mortality were both fairly steady in the year or so prior to implementation of expanded naloxone access policies. After the laws went into effect, however, mortality rates associated with use of both drugs increased (Doleac and Mukherjee, 2018).

Pushback and Controversy: The Challenges of Delivering Bad News

Following the publication of the results of the ban-the-box and naloxone access studies, Doleac and colleagues faced a wide range of reactions. There was pushback against the ban-the-box study from advocates, she said, and there was much discussion about the research methodology. With regard to the naloxone access study she said that, while she expected the findings would be controversial, she was taken aback by the viciousness of some of the criticism, especially from the public health community. She added that the conversation was different than the one researchers had had with the criminal justice advocacy groups regarding ban-the-box policies.

Doleac shared a sampling of the comments about the studies that were posted or published on blogs, social media (especially Twitter), and online news sources, as well as in mainstream publications. Many

comments were sincere efforts to understand the methodology, and she noted that others in the economics community joined the conversation to attempt to explain the types of research methods economists use to those less familiar with them. There were discussions of correlation versus causation. Some people expressed fear that policy makers would respond to the findings by reversing the broadened naloxone access policies. Some comments were simply inflammatory. Ultimately, Doleac and Mukherjee posted a response addressing the criticisms and concerns. In the response they emphasized that “academics have a responsibility to facilitate accurate interpretations of their research” and that they “don’t agree that academics should quash research results that don’t fit the narrative of one advocacy group or another.”6 She added that the response from policy makers and practitioners was gratifying in that they recognized that “even worthwhile policies involve cost as well as benefits.”

Moving Forward

In closing, Doleac emphasized the need to rigorously evaluate policy initiatives because not all of them will meet expectations. Many efforts in public health, education, criminal justice, and other areas will not have the intended effects because human behavior is complicated. “Be humble and aim to fail quickly,” she said, and keep trying because there are solutions to these problems. “Even worthwhile policies involve trade-offs,” she continued. There are costs, and rigorous evaluation helps to clarify the costs relative to the desired benefits and to possibly mitigate those costs. Finally, implementation should include a plan for evaluation, she said.

DISCUSSION

Tim Bruckner of the University of California, Irvine, commented that he has observed academic researchers downplaying potentially controversial study findings about the benefits or lack thereof of implemented policies. When pressed as to why, he said some expressed concern about how decision makers opposed to the policy might use the results. Bruckner asked how population health professionals can move forward on difficult issues while being respectful of academic discourse. Doleac added that she has heard from junior researchers in public health who are so concerned about backlash they might experience from publishing

___________________

6 Quoted text presented by Doleac is taken from the response that is posted on the Institute of Labor Economics Newsroom webpage and is available at https://newsroom.iza.org/en/archive/research/the-moral-hazard-of-life-saving-innovations-naloxone-access-opioid-abuse-and-crime (accessed December 23, 2020).

their research that they consider abandoning it or not publishing. “There is a cultural norm here that needs to change,” she said. Researchers need to be able to discuss study findings even if they are not what they (or the field) anticipated.

In response, Jeffrey Levi of The George Washington University referred to the presentations by the first panel of the symposium and said that they demonstrate that the field of population health is willing to acknowledge that there are problems and to discuss current findings that are not ideal. He also suggested that the association between the availability of HIV medication and risky sexual behaviors mentioned by Doleac is not commonly accepted, and wondered what other explanations might be plausible for the increased opioid mortality rates observed after implementation of expanded naloxone access. Galea responded that the specifics of the studies presented by Doleac were better addressed in a separate discussion. Instead, he said that a key takeaway from her presentation for him was the need for tolerance in discussions about potentially controversial studies. He also said it would be a disservice to the public to not attempt to explain the complexities of the research. He observed that public health, as a scholarly community, is often conflating scholarship with advocacy.

Joshua Sharfstein of John Hopkins University agreed with the need for respectful dialogue and added that serious academic critiques should not be discounted as invalid or simply as an affront by advocates because they question the findings. He mentioned, for example, a naloxone study done at Boston University that had a strong design and was peer reviewed; it found a significant reduction in opioid mortality after broadened access (Walley et al., 2013). There is “a real evidentiary discussion that can be had respectfully,” he said. Galea agreed that dialogue is needed and should be encouraged, but he also repeated his concern that there are increasing “instances of conflating what should be a scientific discussion with what might suit an advocacy agenda.” Doleac emphasized that she and her coauthor are very open to serious academic discussions about the methodology, especially conversations across the disciplinary lines of health and economics.

Levi also felt that the discussion about health care turning attention to the social determinants of health was unnecessarily negative, as health care has resources, access to people, and political clout that are useful to population health. He mentioned, for example, that accountable communities for health focus on upstream factors. He felt that downstream attention to population health in the form of population health management was positive. Lantz said she agreed but reiterated her concerns about the monetization and medicalization of population health. She clarified that she is not against population health management, but rather, she was

emphasizing the need for continued attention to upstream factors that shape health.

Philip Alberti of the Association of American Medical Colleges raised the need to engage the community and end users in the development and evaluation of population health policies. He observed that policy makers often fail to anticipate unintended consequences or to consider other outcomes that might be relevant to stakeholders beyond the health field. Doleac agreed that academic researchers need to expand beyond their silos, policy makers need to take research findings into account, and input from the community is needed to inform research and policy making. Galea, referring to the prior discussion, underscored both the value of discussion among the experts who have the knowledge and expertise to understand the methodological nuances and complexities of the issues, and the value to “being responsive to and sensitive to contemporary concerns” to ensure that policies are relevant to the community. These are not necessarily contradictions, he said.

This page intentionally left blank.