2

Societal and Structural Contributors to Disease Impact

I grew up in West Africa, where having sickle cell disease is not something that is shared. You don’t go around telling people that you have sickle cell disease, even though it is not my fault that I have the disease. But it is a stigma attached to having that disease. You don’t go around telling people.

—Jenn N. (Open Session Panelist)

INTRODUCTION

Chapter 1 highlighted the fact that the needs of those affected by sickle cell disease (SCD) have been overlooked by the health care system. However, these needs extend beyond the health care system itself. It is impossible to view SCD as simply a medical condition without an understanding of the sociopolitical and cultural context. In the United States, SCD disproportionately affects African Americans, which has implications for health care access, delivery, and outcomes.

The experience of SCD is shaped by sociocultural factors, environmental factors, and socioeconomic factors, which can exacerbate the disease’s impact for people from racial and ethnic minority groups living with the disease. Because of systemic racism, unconscious bias, and the stigma associated with the diagnosis, the disease brings with it a much broader burden. Socioeconomically, African American children living with SCD are more likely to be in a household below the federal poverty level (Boulet et al., 2010). The additive effects of adverse health outcomes and the associated costs magnify the economic burden.

Complications associated with the disease may also affect the mental health of individuals living with SCD by increasing the risk of depression and overwhelming their coping reserves. For adolescents and children these effects may extend to educational achievement, and for adults they may extend to employment, thus affecting opportunities across the life span.

Environmental factors also affect the experience of people living with SCD. For example, children exposed to environmental hazards are more at risk for low cognitive functioning (Liu and Lewis, 2014). These exposures also contribute to comorbid conditions, such as asthma.

Despite the disproportionate burdens of living with SCD, many individuals are highly resilient. They develop strong coping skills and often have a strong spiritual or faith-based foundation. Individuals from cohesive families also have demonstrated resilience.

This chapter will discuss a variety of non-medical risk factors, describe how they affect individuals living with SCD, and explain the importance of and strategies for mitigating these risks as part of a comprehensive approach to addressing whole-person needs.

SOCIETAL FACTORS

A variety of societal factors tend to add to the burden of SCD. Those factors include the stigma associated with SCD, implicit bias, and racism. Given that most SCD and sickle cell trait (SCT) studies in the United States have focused on African Americans, the available evidence on the impact of these societal factors on other populations in the United States

(the “emerging populations”) is very limited. The discussion in this section therefore focuses primarily on the African American population. As the body of literature on SCD in global populations increases, so should research with the emerging populations in the United States.

Stigma and Bias

Stigma is one of the burdens borne by individuals with SCD. Health-related stigma refers to “a social process or related personal experience characterized by exclusion, rejection, blame, or devaluation that results from experience or reasonable anticipation of an adverse social judgment about a person or group identified with a particular health problem” (Weiss and Ramakrishna, 2006, p. 536). Stigma may also have health-related impacts if it results in individuals having limited access to beneficial services because they are socially judged or excluded because of their identity, such as race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sexual orientation (Weiss et al., 2006). Stigma can create serious barriers to care, intensify existing physiological symptoms, and impose a severe psychological burden. Research has found that stigmatized individuals with SCD have decreased quality of life (QOL) and face numerous mental health challenges (Bediako et al., 2016; Wakefield et al., 2017).

The stigma associated with SCD can be traced to various sources, including racism, disease status, socioeconomic status, and pain episodes that require treatment with opioids (Bediako and Moffitt, 2011; Bulgin et al., 2018; Jenerette and Brewer, 2010; Wakefield et al., 2018), and it can be expressed by family, friends, and medical professionals (Bulgin et al., 2018; Wesley et al., 2016). In the United States, health care providers may ascribe negative characteristics to individuals living with SCD, such as labeling them as drug seekers (patients who use manipulative and demanding tactics to obtain prescription medication [Copeland, 2020]), which reflects and exacerbates the stigma and compromises health care use and quality of care (Bediako and Moffitt, 2011; Bediako et al., 2016; Bulgin et al., 2018; Jenerette and Brewer, 2010; Wakefield et al., 2018). Many patients report experiencing social isolation and a fear of disclosing their disease status because of the stigma associated with the disease (Leger et al., 2018).

Internalized stigma can heighten individuals’ concerns about their employability and, if their disease status is known, affect their ability to interact regularly with others. Stigma can also affect an individual’s use of health care and provider–patient interaction. SCD patients report fearing being viewed by providers as drug seekers and as seeking “unnecessary” pain treatment (Anderson and Asnani, 2013; Glassberg et al., 2013).

SCD-related stigma is a global problem. A study in Nigeria found that individuals with SCD who reported depressive or suicidal symptoms

often reported also having experienced stigma or discriminatory remarks (Ola et al., 2016). The psychosocial impact of stigma also includes the fear of being devalued or viewed as less worthy by others, including close friends and relatives. In Saudi Arabia, SCD patients reported having experienced stigma from health care providers, with some stating that they were called addicts for seeking treatment for their acute vaso-occlusive pain (Asiri et al., 2017). Such experiences prompted some patients to seek consultations online from international clinicians.

Stigma can also affect intimate relationships because of the fear of being viewed differently; the various physiological complications of SCD, such as pain episodes and delayed pubertal development, can magnify the effects of stigma on a relationship (Cobo et al., 2013). In India, a study of 52 adolescents (25 with sickle cell anemia, a specific form of SCD; 12 with SCT; and 15 with neither) found that stigma had tremendous impact on the QOL of the children with SCD (Patel and Pathan, 2005). The children included in the study reported experiencing stigma and perceiving themselves to be a burden on their family. Furthermore, children with SCD—and, to a lesser extent, SCT—were found to have a lower QOL across all domains: physical, cognitive, and psychosocial. Stigma was postulated as being a central factor causing the perceived lack of support and disinterest from teachers for students with SCD.

SCD stigma also affects non-black individuals with the disease. According to a study in New York, health outreach workers at a community-based organization reported a perceived stigma associated with having an “African” disease among Dominicans and that family members requested that knowledge of their SCT status be kept within the family (Siddiqui et al., 2012). Perceptions of SCD as a “black disease” can cause Latinx people and other ethnicities to avoid accessing health care appropriately (Gallo et al., 2010; Siddiqui et al., 2012).

Implicit Bias

Unconscious bias, also known as “implicit bias,” refers to attitudes or stereotypes that are outside one’s awareness but that affect understanding, interactions, and decisions (Staats et al., 2016). Individuals’ ability to quickly and automatically categorize people is a fundamental quality of the human mind: “Categories give order to life, and people group other people into categories based on social and other characteristics daily. This is the foundation of stereotypes, prejudice, and, ultimately, discrimination” (Teaching Tolerance, n.d.).

Researchers have found that all people harbor unconscious associations—both positive and negative—about other people based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender, age, social class, and appearance (Kirwan Institute, 2017). These associations may influence people’s feelings and

attitudes and result in involuntary discriminatory practices, especially under demanding circumstances (Kirwan Institute, 2017). Studies show that people can be consciously committed to promoting equal rights and opportunities for all while still harboring hidden negative prejudices or stereotypes (The Joint Commission, 2016).

Despite progress made against overt bias in medicine, unconscious biases still pose barriers to achieving a diverse and equitable health care system (White, 2011). Considerable research has confirmed that unconscious bias in health care delivery has detrimental effects on patient health outcomes (IOM, 2003).

The medical literature shows that a patient’s race can influence clinical decision making, including decisions to offer joint replacement, cardiovascular interventions, and chronic and acute pain management (Katz, 2016; Mody et al., 2012; Wyatt, 2013; Zhang et al., 2016). Nelson and Hackman (2013) used a survey adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2008 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and the Sickle Cell Transfer Questionnaire with specific questions regarding race, racism, and health care delivery in order to investigate the experience of perceived bias among patients, their families, and health care staff at the Sickle Cell Center at Children’s Hospital and Clinics of Minnesota. Half of the patients and their families responding to the survey (a majority of whom identified as black) reported that they saw race as affecting health care, whereas less than one-third of staff (the majority of whom identified as white) felt the same. Based on these findings, the authors suggested that providers’ unconscious attitudes contribute to continued health care disparities (Nelson and Hackman, 2013). A variety of efforts are under way to help reduce provider bias in health care, including the use of social–cognitive psychology and outreach to minority communities (Burgess et al., 2007; Joseph, 2018), but there is a need for studies that evaluate implicit bias against the SCD population.

Racism

Those affected by SCD often also face racism, which is related to but distinct from stigma and implicit bias. Racism is an overarching bias that is responsible for many barriers to SCD care and a social factor that must be addressed as part of a strategic plan for SCD. Because SCD is found mostly among black individuals globally, it is inevitably linked to racism and health inequity.

At the system level, racism manifests in the form of unequal levels of funding and national attention for SCD. One perceived impact of racism is lower funding support for SCD—and the resulting lessened research output—compared with diseases that affect predominantly white

individuals, such as cystic fibrosis (CF) (Strouse et al., 2013). Bahr and Song (2015) argue that SCD should be considered a “neglected disease” based on WHO definitions, as structural violence imposed by racial and economic factors has led to stagnation in treatment advancements. Despite patient interest in participating in clinical trials, more attention is given to CF and other diseases with a lower prevalence (Bahr and Song, 2015). A module embedded in the 2011 Cooperative Congressional Electoral Study to assess perceptions about SCD among participants and how these perceptions were associated with support for government spending on SCD found that white participants supported significantly less funding for SCD than non-white participants did (Bediako and King-Meadows, 2016). This situation affects SCD treatment downstream in the form of stagnant research and development and limited resources for treatment.

At the individual level, some providers express racial biases that result in offering a significantly lower quality of care to African Americans and, by default, individuals living with SCD. There are both similarities and differences among countries with the unique burden imposed by racism. For example, in the United States it is nearly impossible to separate the effects of stigma from racism, as much of the literature does not distinguish between the two. Racism poses an additional burden on the individual and compounds the barriers to treatment and care. In countries with predominantly black populations, racism may still affect treatment, along with related factors, such as colorism or discrimination related to skin color or shade (Bulgin et al., 2018).

Racism and the Treatment of SCD Pain

Acute and chronic pain treatment is affected by racism at an individual level because of provider biases (discussed further in Chapters 5 and 7). The literature shows that many in the medical community hold false beliefs regarding biological differences in perceptions of pain between black and white patients. This perception dates back to the era of slavery (Savitt, 2002). Racist medical knowledge produced during the early 19th century about the black body in pain was used to reinforce existing racialized power structures and justify the U.S. slave system. Clinicians claimed that blacks were built to endure harsh labor conditions due to their limited emotional response capacity. This belief was part of a divisive racial biology that included claims that blacks possess a relative immunity to certain diseases and that they are less sensitive to physical suffering than whites (Hoberman, 2012).

These racist ideas about biological differences between black and white people still persist to a certain degree and affect modern medical practice. In a study of 121 participants with no medical training, the white participants (92) rated the pain that black people would feel across 18 scenarios

(e.g., slamming a hand in a car door, hitting the head, or getting a paper cut) lower than what a white person would experience (Hoffman et al., 2016). Even white medical students and residents are not immune to these misconceptions and may harbor false beliefs about biological differences between white and black bodies, some of which may relate to racial bias in pain perception (Hoffman et al., 2016).

As a result of these racist beliefs about pain, African Americans are more likely to receive a lower quality of pain management than white patients and may be perceived as having drug-seeking behavior. African American patients are significantly less likely to receive pain relief than white patients, even with the same reported levels of pain (Burgess et al., 2006; Tait and Chibnall, 2014), and they may be prescribed fewer pain medications than whites (Green and Hart-Johnson, 2010; Hoffman et al., 2016). People living with SCD may have their pain exacerbated by the emotional distress of not being believed, excessive wait times to get pain relief, insufficient medication, and stigma related to health care use (Haywood et al., 2013).

The racism experienced by individuals with SCD coupled with the longstanding racism in health care and the historical medical exploitation experienced by the African American population has contributed to a mistrust of providers among individuals and families affected by SCD (Stevens et al., 2016; Zempsky, 2010).

The few studies available allude to an association between the experiences of racism and bias and the overall well-being of individuals with SCD. In a 2007 qualitative study, researchers questioned 10 women affected by SCD about their disease-related experiences of stress, perceived racism, and unfair treatment in the health care system and the workplace (Cole, 2007). These underlying risk factors are known to affect African American women to a greater degree, particularly when coping strategies or tools are limited (Cole, 2007). In a very small, non-random sample, eight women reported experiencing stress in the health care system, especially relating to their experience of pain. The women reported that experiences in the emergency department (ED) were a particular trigger for these feelings. As the author stated, “In order to help patients with SCD deal with depression and anxiety, we need to know the source of stress: Is it the disease, the living conditions of the patient, or both?” (Cole, 2007, p. 36).

Lack of Public Awareness

Although public awareness of SCD has increased in recent years, studies indicate that globally there are still significant gaps in knowledge and that individuals living with the disease continue to face stigma. A cross-sectional study conducted in Uganda found that a majority of study participants had heard of SCD but did not know the causes or whether they had the disease

or trait. Close to 70 percent of study respondents stated that they would never marry a person with SCD, indicating high levels of stigma (Tusuubira et al., 2018). Another study of 20- to 32-year-old graduates from Nigerian tertiary educational institutions found a deficit in knowledge about SCD transmission and their carrier status (Adewuyi, 2000).

In the United States, public awareness and misinformation follow similar trends. Individuals with SCD typically lack information about how it is inherited and their carrier status, although they are more likely to be informed if a family member also has the disease (Harrison et al., 2017; Siddiqui et al., 2012). Women are likely to be more knowledgeable than men. This may be because women are provided with genetic counseling during prenatal care (Adewuyi, 2000; Al Arrayed and Al Hajeri, 2010; Harrison et al., 2017; Siddiqui et al., 2012). There are efforts to improve national and international awareness of SCD such as the adoption of June 19 as World Sickle Cell Day by the United Nations General Assembly and the designation of September as National Sickle Cell Month by the U.S. Congress. Despite these milestones, there is a need for activities and public education to promote widespread awareness of SCD and SCT.

INDIVIDUAL FACTORS

The effects of SCD vary based on its severity and a number of individual factors that affect how—and how effectively—an individual deals with SCD. These factors include health literacy, demographic variables, cognitive deficits, mental health challenges (e.g., depression), and coping mechanisms.

Health Literacy Issues

Health literacy is the “degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions” (IOM, 2004, p. 32). Factors such as language barriers, communication challenges, and cultural differences can influence health literacy within and across groups. Health literacy skills include recognizing critical symptoms, managing medications, and making decisions about treatments, as well as other important needs. One study found that most of the caretakers of individuals with SCT who received in-person education as part of the study interventions improved their SCT knowledge over a 6-month period. The caregivers who did not achieve high SCT knowledge after education were those who had lower health literacy at baseline (Creary et al., 2017). In a study of adolescents living with SCD, Perry et al. (2017) found that their health literacy scores were lower than expected for their respective average grades. Examples of poor health literacy range from misunderstanding providers’ instructions to

not understanding the biological bases of SCD or the importance of medication adherence. Although the findings do not suggest that SCD is the cause of poor health literacy, they could be indicative of a need to increase SCD health literacy in the affected population so as to increase adherence to treatment, the likelihood of keeping appointments, and the ability to improve QOL and health outcomes (Adediran et al., 2016; Khemani et al., 2018).

The educational tools that are developed to improve health literacy should include information on not only SCD, managing medications, and making decisions about treatments but also curative therapies, such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), gene transfer, and genome editing. They should be culturally appropriate and written with the appropriate attention to literacy levels for laypersons. In considering HSCT as a potential option, for example, patients must undertake a complex decision-making process that requires knowledge about disease-related complications, the availability of donors, relationships with caregivers, and numerous other factors (Khemani et al., 2018). Globally, knowledge about HSCT for SCD is low, indicating a need for educational tools aimed at increasing literacy on this topic among caregivers and patients as well as the general population (Adediran et al., 2016; Bugarin-Estrada et al., 2019). Interestingly, adequately informed patients tend to overestimate the effectiveness of HSCT, whereas patients and caregivers who lack information have less acceptance and belief in its efficacy (Adediran et al., 2016; Bugarin-Estrada et al., 2019).

Impact of Cognitive Deficits from Stroke and Anemia in the Population

Individuals with SCD have been shown to be at a higher risk for cognitive impairments according to a meta-analysis on the topic (Prussien et al., 2019). These impairments include reductions in attention, memory, language, and general cognitive function and may result from not only the highly prevalent stroke and silent cerebral infarcts (SCIs) but also from the impact of chronic illness and chronic anemia that reduce overall oxygen delivery to vital organs, including the brain. Even in individuals without a history of stroke or silent infarcts, cognitive deficits are visible early in childhood, possibly because of the disruption of cerebral blood flow. In studies examining various levels of cognitive function, individuals with SCD who had no history of stroke still performed worse on tests of cognitive function than controls (Kawadler et al., 2016; Prussien et al., 2019; Sanger et al., 2016). Tailoring interventions to address cognitive function early in childhood may increase cognitive capacity following overt strokes and could be included in the vocational rehabilitation services provided for adults with SCD, who may continue to experience SCIs.

Neurocognitive deficits may have a positive feedback effect (causing symptoms to worsen faster). One study found that cognitive impairment

was related to adult SCD patients’ inability to adhere to hydroxyurea (HU) therapy (Merkhofer et al., 2016), which could further worsen physiological and psychosocial symptoms. Some researchers have theorized that poor adherence to treatment in older adults may stem from neurocognitive deficits from early childhood that went unrecognized, such as impairments in episodic memory (Kawadler et al., 2016; Merkhofer et al., 2016). These early cognitive deficits and impairments to processing may also be associated with an increased risk for unemployment later in life (Sanger et al., 2016). Thus, a model for chronic care designed to preserve and optimize cognitive function should be implemented starting in early childhood, with continued support across the life span.

One such model involves the use of community health workers (CHWs) to successfully manage chronic disease treatment and aid in self-management and positive decision-making behaviors targeted to support medically identified cognitive deficits (Hsu et al., 2016). CHWs have been integrated into several SCD programs in the United States, and they aid in finding adolescents and young adults who have been lost to follow-up. Additional CHW-specific services include reminding patients to adhere to medical appointments and HU treatment and helping families overcome social barriers to care. Although long-term follow-up will be necessary to fully examine the efficacy of CHWs, this model can be used to ensure continuous chronic care support for individuals with SCD and to reduce the negative behavioral and social impact of neurocognitive impairments.

Mental Health Impacts

The family carries with it that guilt of the gene, and that heaviness, and that feeling from generation to generation of surrender to this thing that is constantly disrupting life: the feeling of helplessness.

—Adrienne S. (Open Session Panelist)

Research studies show that adults and children living with SCD experience mental health impacts from the condition, as discussed in Chapter 4. These studies have focused primarily on assessing such variables as anxiety, depression, coping, neurological complications, and QOL. The rest of the discussion in this section focuses on the mental health impacts of SCD on caregivers.

Adults who are providing care for children, adolescents, or life partners living with SCD also face impacts on their mental health. Parents and caregivers may have an overall negative perception of their child’s QOL. Palermo et al. (2002) compared health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) scores for children living with SCD to a sample of demographically similar

healthy children without SCD using the Child Health Questionnaire–Parent Report Form. Caregivers of children living with SCD reported that their children had more limited psychological and social well-being than caregivers of healthy children reported for their charges. Caregivers of children living with SCD also reported to be more affected emotionally by their child’s health. Panepinto et al. (2005) compared HRQOL scores for children living with SCD as reported by the children with the scores reported by their parents. Parents were more negative in their perceptions of health, self-esteem, and behavior of their children living with SCD than were the children themselves.

Caregivers of children with SCD were also reported to worry more than caregivers of children without the disease and to be more likely to have poorer mental health outcomes. Noll et al. (1998) compared the responses of 48 caregivers of children living with SCD to questions about their child-rearing practices with the responses of 48 caregivers of comparison peers. Only two items, both pertaining to parental concern or worry, were significantly different between the two groups of caregivers: “I worry about the health of my child” and “I don’t want my child to be looked upon as different from others” (Noll et al., 1998). In a 2006 interview study of maternal caregivers of children living with SCD, mothers caring for children with SCD had higher depressive mood scores than mothers caring for healthy children (Moskowitz et al., 2007). The authors stated that “additional attention is warranted to developing adequate resources for caregivers of children with SCD to mitigate the stress of unexpected crises” (p. 64).

In a recent investigation of caregivers of adolescents living with SCD, based on focus group data, caregivers reported the perception of stigma about SCD across a variety of settings, such as academic, athletic, and medical settings (Wesley et al., 2016). Caregivers also reported internalized stigma and other negative feelings about the disease. Caregivers suggested more education for all individuals who work with children living with SCD and increased public awareness to improve the situation for individuals with SCD and their families (Wesley et al., 2016).

The mental health challenges experienced by caregivers for children living with SCD are understudied. Additionally, interventions designed to ensure that caregivers have an adequate understanding of SCD are needed. Support groups, information about financial assistance, and strong relationships with health care providers could all assist in meeting the needs of caretakers.

Coping Mechanisms

Because of the variability of the SCD phenotype, individuals have adopted different strategies for coping with the related physical and psychosocial complications. Many studies have attempted to identify and classify

these strategies, which range from cognitive and behavioral strategies to religion and spirituality (Anderson and Asnani, 2013; Clayton-Jones and Haglund, 2016; Cotton et al., 2009; Gomes et al., 2019; Harrison et al., 2005; Hildenbrand et al., 2015). One study, for example, examined the utility of Roth and Cohen’s “approach” versus “avoidance” coping framework, which has been used to categorize coping strategies for individuals with chronic diseases, to SCD (Hildenbrand et al., 2015). The approach model refers to strategies that directly deal with or mitigate a stressor, whereas the avoidance model includes strategies that attempt to distance the individual from a stressor. The study found that children with SCD and their parents use both “approach” and “avoidance” strategies to manage disease-related stressors, including pain episodes.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is one effective method that has been used to help the SCD population reduce health care usage for pain and minimize the disruptions in their daily activities caused by pain (Schatz et al., 2015). CBT interventions typically involve psychoeducation, distraction strategies, and coping mechanisms. Recent studies show that introducing a CBT intervention through smartphone technology could increase coping skills and reduce SCD-related complications in children (Palermo et al., 2018; Schatz et al., 2015). Because the majority of pain episodes in children are typically managed at home (Yang et al., 1997), an easily accessible technology, such as mHealth, may be beneficial for promoting positive coping strategies. Cognitive and behavioral coping strategies have also been used by individuals living with SCD in Jamaica to reestablish control over their response to SCD, others’ responses to SCD, and the physical manifestations of SCD (Anderson and Asnani, 2013).

In addition, individuals with SCD may develop various coping strategies and adaptive behaviors on their own to respond to their stressors. A study of adolescents found that building self-esteem, drawing on family support, and strengthening relationships with parents were key adaptations to SCD (Ziadni et al., 2011). Furthermore, as adolescents learned to self-manage their symptoms, their perceived self-competence and self-reliance increased. Understanding how individuals with SCD naturally develop their own coping strategies could aid in tailoring interventions to work in conjunction with natural adaptive behaviors.

Spirituality and Religiosity

Spirituality has been found to be a powerful coping mechanism for individuals with SCD, and struggles with spirituality and faith have been associated with poor mental health and psychological outcomes (Adegbola, 2011; Adzika et al., 2016; Bediako et al., 2011; Clayton-Jones and Haglund, 2016; Clayton-Jones et al., 2016; Harrison et al., 2005). Spirituality may

allow individuals to decrease negative attitudes and mental states, such as fatalism and hopelessness, which are known to be key factors in pain perception, to be associated with poor self-efficacy, and to further compound issues in chronic care management (Adegbola, 2011; Jenerette and Murdaugh, 2008; Jenerette et al., 2005). Because of the power of religion as a support and coping mechanism and its cultural importance in navigating community and identity, individuals with SCD may find it useful to explore its benefits.

Managing SCD requires a holistic approach aimed both at decreasing hospitalizations and symptoms and increasing the overall QOL (Adegbola, 2011). Patients’ self-reported religious coping is associated with fewer hospital admissions and decreased pain perception (Bediako et al., 2011; Harrison et al., 2005). It has been theorized that religion works by increasing access to social support, psychological resources, positive health behaviors, and a sense of coherence (Harrison et al., 2005). A study of adults living with SCD in Ghana revealed that strategies for coping with SCD included attending a place of worship and praying and that SCD pain was the main reason for using these strategies (Adzika et al., 2016). A 2015 review of the literature on the roles of spirituality and religiosity in adolescents and adults living with SCD confirmed that they are sources of coping associated with enhanced pain management and improved health care use and QOL (Clayton-Jones and Haglund, 2016). Nonetheless, few studies have examined the effects of spirituality and religiosity on SCD outcomes. More work is needed to understand their influences on SCD experiences and outcomes in diverse populations. Efforts may need to be directed at engaging and educating religious leaders in order to understand their potential role in increasing the coping ability of individuals with SCD and other serious illnesses through spirituality.

Other Protective Factors

Researchers have found that a number of other factors can protect against various harms associated with SCD. For instance, Ladd et al. (2014) found that high family cohesion, as measured by the Family Environment Scale via interviews with parents, was positively correlated with a lower likelihood for grade retention and might protect children with SCD against poor academic achievement. Thus, a positive family environment can serve as a protective factor for these children.

As described earlier in this chapter, Ziadni et al. (2011) looked at self-report data from 44 adolescents to consider the links among stress-processing variables (appraisals of hope and pain coping), QOL, adaptive behaviors, and coping strategies. Low QOL scores were significantly associated with less adaptive behaviors, while appraisals of hope were

significantly associated with more adaptive behaviors. The authors concluded that “stress processing variables (coping and appraisals), essential to successful adaptation to the demands of sickle cell complications and disease course” (Ziadni et al., 2011, p. 341), are important elements of resilience for such adolescents.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

In addition to societal and individual factors, environmental factors also contribute to the variability in how SCD manifests clinically; however, the exact roles that such factors play in influencing symptoms and complications are not well understood. Environmental factors range from the physical, such as climate and temperature, to the socio-environmental, such as place of residence and discrimination. These factors are often interrelated. For instance, residential area is correlated with factors such as air quality, socioeconomic status, school and work environments, and access to healthy foods.

Studies have found exposure to cold or wind to be correlated with higher incidences of pain crises and emergency admissions (Tewari et al., 2014, 2015). Residential area also influences SCD symptoms. A study in Jamaica found that urban patients who lived closer to factories had more severe respiratory events and pain crises than rural patients (Asnani et al., 2017). Severe outcomes were associated with higher poverty and living further away from health care services. Place of residence not only influences access to care but also is related to such factors as socioeconomic status and exposure to pollutants that can initiate or exacerbate common comorbid conditions, such as asthma. Furthermore, socioeconomic stress, financial struggle, and poor parent and family functioning are associated with cognitive deficits in children (Bills et al., 2019; Yarboi et al., 2017). Additional studies are needed to explore modifiable socio-environmental factors and their association with cognitive function and long-term outcomes.

Leg ulcers are one of the most debilitating SCD complications; these are recurrent wounds that appear near the ankles and are challenging to manage for both patients and providers. A cyclical mechanism to explain ulcer formation, proposed by Minniti and Kato (2016), involves malnutrition and underlying vascular damage leading to inflammation and bacterial colonization. Environmental stress, discrimination, and depression can all contribute to heightened pain sensitization and increased inflammation, leading to further ulcer growth and inhibiting healing processes (Minniti and Kato, 2016).

Efforts to improve QOL and outcomes for individuals living with SCD must include attention to environmental contributors, which in general are more amenable to change than molecular and other biological contributors.

Harnessing public will and working with community-based organizations, urban/city planners, and government agencies (e.g., the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development) could be effective in addressing key environmental risk factors.

THE BURDEN OF SCD

Many individuals with SCD are twice burdened: first, by a debilitating health condition and, second, by socioeconomic disadvantage. African American children with SCD are about one-third more likely (47.8 percent versus 34.7 percent, p < 0.05) than other similarly aged African American children to reside in a household that lies below the federal poverty level (Boulet et al., 2010). While the study authors offer no explanation for this disparity, the findings suggest that socioeconomic status could have important implications for access to care and use of treatment for children with SCD. Thus, even if the disease imposed no additional economic burdens, children with SCD would, on average, be disadvantaged by their poorer socioeconomic status. The disease itself results in a range of adverse health outcomes that affect daily functioning and potential early mortality. This results in a constellation of disparate problems that contribute to the burden of the illness, which implies that an equally wide range of policy instruments must be deployed in response. Health insurance, disability insurance, employment accommodation, school-based interventions, and medical innovation all must play a role in addressing the SCD burden.

Health Care Cost Burden

One major part of the economic burden of SCD is the additional health care costs imposed on individuals and families, which are so high that they represent a major financial burden on most families. Some families are not able to pay for it all, which results in leaving some aspects of the disease untreated.

The Magnitude of the Health Care Cost Burden

Individuals living with SCD often have considerable unmet health needs, even compared with patients with other serious illnesses. They and their insurers also face substantial financial costs for the health care that they can access. Using data from individuals enrolled in the Florida Medicaid program during 2001–2005, researchers estimated that the lifetime cost per SCD patient with Medicaid coverage exceeds $460,000 for SCD-related and non-SCD-related health care use (Kauf et al., 2009). Given the inflation in medical prices since 2009, it seems probable that updating this

decade-old estimate would result in a current cost of more than $700,000.1 The Florida Medicaid data suggest that the total annual health care costs ranged from $10,704 for the youngest patients (under age 10) to nearly $31,000 for those aged 50–64 (Kauf et al., 2009). Even this is likely an underestimate, considering that Medicaid spending per patient is typically less than that for commercial payers, and Medicaid covers patients for only a portion of their lives (i.e., the low-income, elderly, and individuals with disabilities are covered) (Clemans-Cope et al., 2016; Rudowitz et al., 2019). For both of these reasons, Medicaid data will typically fail to reflect the full lifetime cost burden borne by a cohort of SCD patients.

According to an analysis using SCD epidemiological and claims data, third-party commercial insurers paid approximately $3 billion for SCD-related charges in 2015; more than half was attributable to inpatient costs (more than $15,000 per patient), and more than one-third to outpatient costs (more than $10,000 per patient) (Huo et al., 2018).

Another study estimates that lifetime cost per SCD patient, assuming a 50-year life expectancy, could be as high as $8,747,908 (not accounting for inflation) (Ballas, 2009). This amount was estimated from the true cost (charges) of care for SCD, as opposed to the amount reimbursed by insurers. The author also notes that this estimate does not include the costs of expensive procedures such as iron chelation therapy and blood exchange transfusion for a stroke patient, which occur repeatedly over the lifetime of an individual with SCD.

Truven Health MarketScan® data on Medicaid and commercial health insurance plans suggest that children with SCD annually accrue more than $11,000 on Medicaid plans and nearly $15,000 on commercial health plans (Mvundura et al., 2009). These costs are estimated to be approximately 6 and 11 times the costs incurred by children without SCD on Medicaid and commercial health plans, respectively (Amendah et al., 2010).

Health care costs are borne by patients and their health insurers. Among patients with commercial insurance, SCD is estimated to be associated with approximately $1,293 in additional annual out-of-pocket expenditures (Huo et al., 2018). The financial burden is expected to be even higher for uninsured patients and to worsen with age as chronic end-organ damage accumulates. Young adults with SCD are a particularly vulnerable group; they face a high risk of being uninsured when transitioning from child to adult insurance arrangements. Constructing and implementing registries with long-term follow-up could provide more robust evidence of how SCD patients transition across health insurance status over the life course and true lifetime costs of care.

___________________

1 Estimate based on SCD committee’s analysis.

Mitigating Poor Health Outcomes and the Health Care Cost Burden

Even the best managed SCD patient populations will suffer worse health outcomes than their typical non-SCD counterparts. Thus, eliminating the health-related burden of SCD will require medical innovation, a topic addressed later in this report. However, the evidence suggests that gains can likely also be made by using today’s medical technologies more widely and appropriately.

SCD is a rare disease in the United States, affecting only about 100,000 individuals (Hassell, 2010). The small size of this population—compared with the more common chronic conditions in health care—makes it difficult to conduct empirical analyses that indisputably measure the effects of real-world policy interventions within this group. For example, it is impractical to demand natural experimental or randomized data on a range of plausible real-world interventions because there are too few patients to support such a body of evidence. Instead, policy makers will need to base their decisions on a body of suggestive studies rather than a handful of definitive ones.

A key question is whether expanding access to health insurance and the breadth of services covered can improve health outcomes. There is limited research in the SCD population with which to answer this question; the broader health economics literature reports mixed evidence regarding the ability of health insurance to improve health outcomes. While there are indisputable benefits in the form of greater financial security, there is relatively little evidence that health insurance coverage actually causes gains in health (Baicker and Finkelstein, 2011; Finkelstein et al., 2012; Levy and Meltzer, 2008). However, patients with chronic, severe diseases are an important exception. Research suggests that health insurance access can decrease the likelihood of death for patients with serious illnesses, such as HIV (Goldman et al., 2001). Thus, it is worth considering the idea that health insurance will improve health outcomes for those severely ill with SCD. Medicaid expansion, which has increased access to insurance for millions since the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), is associated with greater access to care, more preventive care, and improved chronic disease management (Gruber and Sommers, 2019). Researchers caution, however, that these are process measures that may not actually affect health state (Allen and Sommers, 2019; Gruber and Sommers, 2019). In reviewing evidence from multiple studies, researchers found that a few studies found evidence that Medicaid expansion has been associated with improved health in low-income U.S. residents as measured by self-reported health, acute and chronic disease outcomes, and mortality reductions (Allen and Sommers, 2019).

The available evidence specific to SCD patients demonstrates that health insurance status clearly affects access to care. Research using the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample—a sample of ED visits—found that insurance affected whether SCD patients were admitted to the hospital

when presenting at the ED (Krishnamurti et al., 2010). Insured patients were about 50 percent more likely (42.3 percent versus 30.5 percent) to be admitted. Among the insured, the commercially insured were the most likely to be admitted, followed by those insured by Medicaid and those insured by Medicare (45.4 percent, 42.0 percent, and 39.9 percent, respectively) (Krishnamurti et al., 2010).

While this evidence does not definitively prove a causal link between health insurance and health outcomes, there are at least two possible explanations, both of which suggest a role for health insurance as a policy lever. First, uninsured patients may be denied access to clinically appropriate inpatient care. This would be true if they either avoided presenting to the ED with acute exacerbations or, when they did arrive, they were similar in health status to the insured patients. If so, this would suggest that health insurance can expand access to appropriate care. On the other hand, uninsured patients may be using ED visits for less acute episodes, which would normally be handled by a routine source of care. If so, then the logical conclusion would be that insurance promotes access to routine care for SCD patients. This latter interpretation is indirectly supported by a study of California ED data (Wolfson et al., 2012), which found that patients living farther from a comprehensive SCD care provider ended up with more ED visits but a lower likelihood of inpatient admission in the wake of the ED visit.

There is also evidence for an underlying causal mechanism linking insurance status with health outcomes in the SCD population. First, insurance affects access to HSCT. Commercially insured patients were nearly three times as likely to receive HSCT as Medicaid and uninsured patients (Anand et al., 2017). A review of state Medicaid websites reveals that these programs are more likely to restrict HSCT coverage in various ways, including limiting coverage of donor search and standard transplant indications and imposing ceilings on the number of inpatient days allowed (Preussler et al., 2014). Bone marrow transplantation exhibits qualitatively similar patterns. Among transplant centers, 45 percent and 30 percent faced considerable issues with Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates, respectively. Issues with commercial payers were present but were less prevalent and severe (Silver, 2015).

This evidence suggests that access is best for commercial payers, next best for Medicare patients, and worst for Medicaid patients. While the literature contains no specific comparisons between patients with Medicaid and uninsured patients, this is likely due to low rates of uninsurance and the resulting small sample sizes—as discussed below, uninsurance rates are 1–7 percent, depending on the age group. Insurance status appears to covary with mortality rates in much the same way that it covaries with access. In an inpatient sample, uninsured patients and Medicaid patients were more likely to develop complications and die than were Medicare patients (Perimbeti et al., 2018). For example, uninsured patients were 3.5–7 times

more likely to die from their complications than Medicare patients. This study controlled for demographic factors available in inpatient data, including race, age, sex, income, and comorbidities. Confounding from unobservable disease severity remains an issue, however.

Adverse outcomes for Medicaid patients are of particular concern, because Medicaid likely covers the majority of SCD patients. The committee was unable to find national estimates of health insurance coverage for SCD patients in the literature. However, surveillance data from California shared by the CDC Foundation with the committee provide some relevant insight. Among the sample of SCD patients who visited EDs in 2016, 56 percent had Medicaid, 21 percent had Medicare, 16 percent had commercial insurance, 4 percent were uninsured, and the remaining 3 percent had other types of coverage.2 These data will be used to inform the below discussion of insurance status, with the caveat that the discussion is limited to the California ED population. This is another potential application of sickle cell registry data.

While the estimated 4 percent rate of uninsurance in the California ED population is below the national average, which was 10 percent for all non-elderly Americans in 2016 (Tolbert et al., 2019), the fact that 1 out of every 25 SCD patients lacks health insurance is still a concern. In addition, the average figure blurs differences across age groups. Wider access to Medicaid among children and to Medicare among older people often leaves other adults behind. The rates of uninsurance are 2 percent, 1 percent, and 1 percent for people under 10, 10–19, and over 60, respectively. On the other hand, 7 percent of 40- to 49-year-olds are uninsured, as are 4 percent of 20- to 29-year-olds, despite the ACA provisions that make it easier for young adults to remain on their parents’ health insurance.

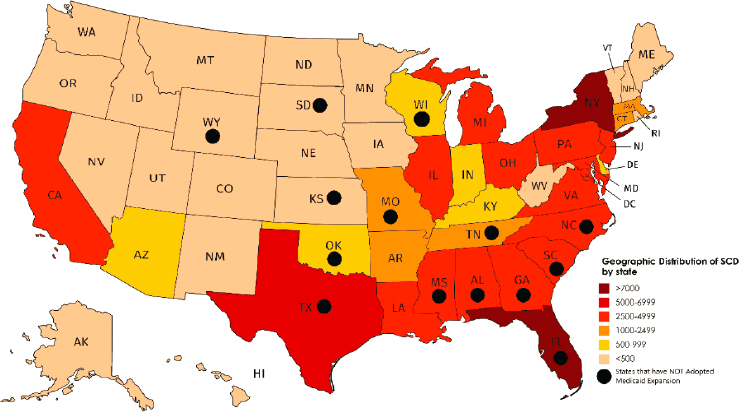

The rate of uninsurance for the SCD population is expected to vary nationwide. Using the California estimates, public insurance continues to be the highest source of insurance for this population, and most of the southern U.S. states, which have the highest estimated number of individuals with SCD, have not expanded Medicaid eligibility per provisions in the ACA (see Figure 2-1). It is worth noting that Medicaid insurance coverage is determined by the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) criteria, which are structured to required “disability” as a prerequisite for coverage, as discussed later in this chapter. This causes various problems as it precludes an individual from participating in the employment sector and being covered by Medicaid at the same time, thus contributing to the economic burden borne by the individual.

___________________

2 Analysis derived from surveillance data for California for 2010–2016, shared with the committee by the CDC Foundation’s Sickle Cell Data Collection program.

NOTE: SCD = sickle cell disease.

SOURCE: Reprinted and modified from Hassell, 2010, with permission from Elsevier. Medicaid expansion data from KFF, 2019.

Taken as a whole, the evidence suggests that health insurance affects access to particular therapies, correlates with access to health care facilities, and correlates with mortality and outcomes in the same direction. It is not possible to rule out that poor health outcomes among, say, Medicaid and uninsured patients result from the patients’ greater disadvantage status rather than from their insurance status. However, because health insurance affects access to effective therapies, it seems plausible that health gains could be made by expanding coverage.

Alongside its effects on health outcomes, health insurance also provides financial protection against catastrophic medical spending. Randomized evidence from the Oregon Medicaid experiment suggests that generous Medicaid coverage substantially reduced the likelihood of beneficiaries going into debt or skipping other bill payments in order to afford their medical care (Baicker and Finkelstein, 2011). While the Oregon experiment was not specific to SCD, it is plausible to believe that the benefits might be even larger for families facing SCD than for a representative sample of Oregonian families at or near Medicaid eligibility. Expanding the generosity of health insurance coverage (e.g., by reducing copayments, cost-sharing, and deductibles) would almost certainly improve financial security and ameliorate the social and psychological burden for families affected by SCD.

Economic Burden Beyond Health Care Costs

Because SCD is a debilitating disease that impairs functional status, affected individuals experience adverse effects on employment and education, which magnify the underlying health burden. The following discusses the magnitude of this burden and potential ways to mitigate it.

Disruptions in Employment

The committee could not find national estimates for unemployment rates in the SCD population. According to Sanger et al. (2016), various studies report that approximately 28–52 percent of individuals with SCD are unemployed. This proportion is substantially higher than the U.S. unemployment rate of 3.6 percent as of January 2020 (BLS, 2020). Several studies have researched the impact of SCD on employment. Sanger et al. (2016) considered the hypothesis that unemployment is related to cognitive deficits. The authors reviewed the charts of 50 individuals living with SCD for employment status and intelligence (as measured by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale). The authors found an unemployment rate of nearly half (44 percent) and an association between lower educational attainment and higher odds of unemployment. It is unclear whether this link is due to cognitive impairment as a result of SCD, although the authors suggest that this may contribute to the risk of unemployment and argue for specific education and vocational services to be made available.

Idowu et al. (2013) compared 20 patients living with SCD to non-SCD siblings. Each patient completed a series of questionnaires about employment history and also answered questions concerning a sibling’s employment history. The authors found that 75 percent of the siblings were employed (15 out of 20) but that only 20 percent of the individuals living with SCD were employed (4 out of 20). Fourteen of the individuals living with SCD received disability benefits, and 14 out of the 16 individuals with SCD who were not employed expressed a desire to have a job. The authors concluded that SCD has a major negative impact on successful employment, and they argue for developing workplace assistance interventions.

The treatment of SCD can also affect employment status. Ballas et al. (2010) compared employment status and changes therein for individuals receiving and responding to HU, individuals who did not respond to the treatment, and a placebo group, all participating in a multi-center study of HU for treating SCD. Although there were no statistically significant differences in employment among the groups, there was a general trend indicating more consistent employment in the HU group. The authors postulate that the lack of a significant difference between the treatment and placebo groups could also be attributed to the fact that most of the enrolled study participants had moderate to severe disease with significant complications.

The authors conclude that “it would be attractive to hypothesize that future treatment of young patients with HU could prevent or mitigate the incidence of complications of sickle cell anemia and, hence, improve the employment status of treated patients” (Ballas et al., 2010, p. 999).

The ability to successfully gain and maintain employment is an important factor in adult mental health. The Office of Disability Employment Policy in the U.S. Department of Labor offers guidelines for workplace accommodations for individuals living with SCD (JAN, 2019). These accommodations may include a flexible schedule that allows the individual to receive necessary medical treatment, an adjustable workstation, and an aide, if needed.

Facilitating employment can be a positive factor in managing health care use. Williams et al. (2018) followed 95 individuals living with SCD prospectively and found that employment was significantly associated with decreased health care interactions. Additional interventions to assist individuals in seeking employment are needed. Educational interventions for potential employers could also make a difference. This is an area for more public investments in research.

An additional factor to consider is that the mortality burden of SCD reduces lifetime income. A recent study estimates that premature mortality alone decreases lifetime earnings by about 40 percent; lifetime income is calculated to be $1.2 million for individuals living with SCD but $1.9 million to $2 million for matched controls (Agodoa et al., 2018).

Family caregivers also experience deficits in employment and income. They are burdened by the time they spend on diagnostic procedures, medication administration, care for in-dwelling tubes, and skin care (Moskowitz et al., 2007). Comprehensive estimates of time costs are not available for the SCD population specifically, but a study on children with special health care needs found that family caregivers for such children spend an average of 260 hours per year3 on caregiving (Romley et al., 2017). This time commitment is estimated to be worth $3,200 per child per year (in 2015 dollars). Improving health insurance access and generosity might address out-of-pocket spending burdens, but there are few financial instruments available for insuring patients against this considerable time cost of caregiving.

Educational Attainment

Perhaps due to the combined effects of socioeconomic status and the disease itself, children with SCD have poorer educational outcomes than those without it. Depending on the severity and location of ischemic

___________________

3 Approximately 5.6 million U.S. children with special health care needs received 1.5 billion hours annually of family-provided health care.

injury from strokes in SCD, overall intellectual capacity may be adversely affected as well as subdomains of attention and executive function, language, memory, and visuomotor skills (Berkelhammer et al., 2007; Boulet et al., 2010). Ladd et al. (2014) studied the neurocognitive effects due to strokes from SCD on poor academic performance using a nationally representative sample of 370 children and adolescents with SCD. The researchers assessed academic achievement via the Woodcock-Johnson tests of cognitive abilities and grade retention history. Parental reports indicated that 19 percent of the youth had been held back for at least one grade. Low math achievement and low reading achievement were both related to a higher likelihood of grade retention. Children with SCD may also experience higher rates of school problems because they disproportionately come from low-income, minority families; both factors that have been shown to confer independent risk for poor outcomes (NRC and IOM, 2000). This increased risk for academic difficulties may make children with SCD eligible for special educational assistance. Nearly one-third of children with SCD must repeat a grade or require special education services; this is more than double the corresponding rates for their non-SCD peers (Schatz, 2004). Herron et al. (2003) reported that in a sample of 26 high schoolers living with SCD in the St. Louis area, only 4 were on target to graduate on time. The authors surmised that these students were receiving inadequate educational support. A brief description of a second study of 39 students (Herron et al., 2003) reported that 28 percent had been held back for at least one grade. However, research on the efficacy of grade retention indicates that it is not an effective educational strategy (Peixoto et al., 2016). Additional resources may be needed to improve educational outcomes (Epping et al., 2013). A recently settled lawsuit was filed against Boston Public Schools to force the schools to provide more services for students with SCD, especially tutoring to keep up with classes (Irons, 2018).

Children with SCD are often ill and miss school. A number of studies have examined relationships between attendance and school performance among children living with SCD. Schwartz et al. (2009) assessed medical and school records and had 40 12- to 18-year-olds complete a series of self-reported measures of psychosocial functioning. They found that more than one-third (35 percent) had missed at least 1 month of school. Overall, these youth missed an average of 12 percent of the school year. Absenteeism was significantly associated with the health variables and psychosocial measures. The authors conclude that school absenteeism remains a significant problem and that there needs to be collaboration among schools, medical providers, and parents to better manage the academic achievement of students living with SCD. The finding was reinforced by a study by Peterson et al. (2005), which gave a brief needs assessment to 72 parents.

One-third of the parents indicated that their child experienced “frequent school absences” of more than 20 days per year.

Tools exist to assess the educational support needs of children with SCD; however, they appear to be underused, meaning that strategies to effectively address these needs are not appropriately deployed. In the aforementioned study by Peterson et al. (2005) the authors surveyed 72 parents of children (ages 5 to 17 years) living with SCD using the Hematology–Oncology Psycho-Educational Needs Assessment (HOPE) tool, which they developed. According to the HOPE survey results, more than half of all parents expressed concerns about their children’s education and reported teacher concerns about the children’s academic performance. Other data indicated that more than one-third of the children repeated at least one grade (36 percent) and that almost half failed to pass a statewide proficiency exam (47 percent). More than one-third had missed at least 20 days of school (35 percent); the authors also reported on behavioral issues noted by teachers (32 percent) and disciplinary consequences associated with these behavioral issues (38 percent). Less than two-thirds of these children had undergone testing for learning disabilities (64 percent), and even fewer had an individualized education plan in place (28 percent). This suggests that elementary and secondary schools need to better address the academic and functional needs of children living with SCD.

These childhood effects of SCD appear to result in long-term educational costs. Based on retrospective reports, one study found that 85 percent of adults with SCD reported missing school once per week (Idowu et al., 2014). This is 6.5 times the corresponding rate of their counterparts without SCD (p < 0.001). Perhaps not surprisingly, SCD adults’ college graduation rates are less than half that of their siblings without SCD (15 percent versus 35 percent, p < 0.001).

Individuals living with SCD and their families also suffer employment costs as a result of the disease. Those who do secure gainful employment often suffer from poor educational attainment, which would depress their earnings.

Mitigating the Economic Burden

Early childhood development

To ease the educational and economic impact of SCD, it is necessary to offer early-intervention programs, with ongoing targeted support across the life span to mitigate the long-term consequences of complications that occurred early in childhood. There are various programs and policies designed to support early childhood development for children with special needs, but their comprehensiveness and participation are highly variable. For example, all children living with SCD (because they have special health care needs) are eligible for services under the Individuals

with Disabilities Education Act, Part C, which covers young children with a recognized disability or at risk for developmental delay (discussed further in Chapter 5). However, there are sizable state-to-state differences in participation rates, and McManus et al. (2009, 2011, 2019) found that most children who access these services come from low-income households and that there is often a delay from diagnosis to receipt of services. There is a need to expand eligibility and shorten the time between application for and receipt of benefits to help mitigate some of these adverse outcomes.

Richardson et al. (2019) presented data indicating that children eligible for early-intervention services are not using these services as intensely as might be expected. Using an administrative database from a large early-intervention program, the authors reported that children appear to be receiving less substantive services than had previously been the case, and they hypothesized that this may be due to an overall decline in federal per child appropriations for early-intervention services.

Access to early-intervention services appears to be spotty at best and influenced by child and family characteristics, such as the primary language spoken in the home, race, and ethnicity. There are few large-scale studies of early-intervention services at a national level, primarily due to a lack of common data collection elements.

Young adulthood and beyond

To optimize functional outcomes for adults living with SCD, it will be important to develop an understanding of how to improve the structure of existing programs and to remove obstacles so as to make the programs more accessible to these adults and their families. Health insurance does not cover the adverse employment and economic consequences of SCD. Instead, that lies within the traditional scope of disability insurance programs, such as SSDI and SSI. The goal of such programs is to provide partial income replacement to people suffering from disabilities that impair their ability to work.

The design of disability programs must account for the well-known trade-off between insurance and incentives for work. Very generous programs provide better insurance, but they also create incentives for moderately or mildly ill workers to opt out of the labor force and receive disability benefits instead, particularly for groups of workers facing bleaker wage prospects (Autor and Duggan, 2003). In contrast, strict programs provide worse insurance but fewer incentives for borderline workers to leave the labor force. Thus, such programs are, in principle, designed to screen out less severe illnesses that do not compromise the ability to work.

Unfortunately, the eligibility rules for SCD create a number of unintended consequences in their effort to screen out less severe cases. Section 7.05 of the U.S. Social Security Administration’s “Blue Book” lists the four ways to qualify for SSI (SSA, n.d.):

- Six pain crises in a 12-month period that required “narcotic medication” and were spaced at least 30 days apart;

- Three or more hospitalizations of 48 hours or more for hemolytic anemia in a 12-month period;

- Three episodes of hemoglobin below 7.0 grams per deciliter in a 12-month period, spaced at least 30 days apart; and

- Beta thalassemia major that requires “life-long [red blood cell] transfusions at least once every 6 weeks to maintain life.”

Notably, the first three criteria reward patients and their providers for poorly managing complications. Diligently managing anemia and pain crises could disqualify the patient for public assistance, including the insurance benefit that helped get the disease under control in the first place. The fourth does not suffer from the same drawback because it identifies a biomarker that cannot be altered by the patient or provider and that results in difficulty maintaining employment.

More generally, recent research in the economics literature on disability insurance programs—not specific to SCD—recommends expanding access to these programs and reducing the number of eligibility reassessments needed (Low and Pistaferri, 2018). The crux of the argument is that the existing disability insurance program involves a very high rate of rejecting worthy applicants and a correspondingly low rate of accepting unworthy applicants. In such an environment, moving toward more generosity can improve well-being because it admits more worthy applicants than unworthy ones.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusion 2-1: Stigma and racism have been shown to negatively affect access to care, treatment, psychological health, and disease outcomes of individuals with SCD in the United States and globally. However, their impacts are often conflated in the literature, and their mechanisms of action are poorly understood. Further studies are needed to understand the separate and combined influences of stigma and racism on individuals with SCD and to develop and implement strategies to address them.

Conclusion 2-2: Public awareness of SCD is still suboptimal, which further perpetuates stigma and bias against individuals with the disease and trait. There is a need for the development of multimedia (e.g., print, text, video, games, apps) educational materials for the general public and for individuals with SCD.

Conclusion 2-3: The SCD disability insurance criteria are restrictive, especially for young adults as they transition from childhood into adulthood. Loss of SSI has implications for transitioning youth, as it affects their eligibility for Medicaid insurance. The disability insurance eligibility criteria are dependent on the individual remaining disabled and unable to hold a job and underscores the need for better biomarkers of SCD severity that are objective and not easily modifiable by providers, patients, or payers. Such biomarkers would be more appropriate mechanisms for judging disability program eligibility.

Conclusion 2-4: Neurocognitive deficits are both a result and a cause of chronic symptoms in SCD. Neurocognitive deficits early in childhood may affect patients’ abilities to manage their disease in the long term and result in missed appointments, poor treatment adherence, and suboptimal outcomes both clinically and throughout the life span.

Conclusion 2-5: SCD imposes psychological, social, and financial burdens on the individual, caregivers, and family.

REFERENCES

Adediran, A., M. B. Kagu, T. Wakama, A. A. Babadoko, D. O. Damulak, S. Ocheni, and M. I. Asuquo. 2016. Awareness, knowledge, and acceptance of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for sickle cell anaemia in Nigeria. Bone Marrow Research 2016:7062630.

Adegbola, M. A. 2011. Using lived experiences of adults to understand chronic pain: Sickle cell disease, an exemplar. i-manager’s Journal on Nursing 1(3):1–12.

Adewuyi, J. O. 2000. Knowledge of and attitudes to sickle cell disease and sickle carrier screening among new graduates of Nigerian tertiary educational institutions. Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal 7(3):120–123.

Adzika, V. A., D. Ayim-Aboagye, and T. Gordh. 2016. Pain management strategies for effective coping with sickle cell disease: The perspective of patients in Ghana. Scandinavian Journal of Pain 12(1):117.

Agodoa, I., D. Lubeck, N. Bhakta, M. Danese, K. Pappu, R. Howard, M. Gleeson, M. Halperin, and S. Lanzkron. 2018. Societal costs of sickle cell disease in the United States. Blood 132(Suppl 1):4706.

Al Arrayed, S., and A. Al Hajeri. 2010. Public awareness of sickle cell disease in Bahrain. Annals of Saudi Medicine 30(4):284–288.

Allen, H., and B. D. Sommers. 2019. Medicaid expansion and health: Assessing the evidence after 5 years. JAMA 322(13):1253–1254.

Amendah, D. D., M. Mvundura, P. L. Kavanagh, P. G. Sprinz, and S. D. Grosse. 2010. Sickle cell disease-related pediatric medical expenditures in the U.S. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 38(4 Suppl):S550–S556.

Anand, S., R. Theodore, A. Mertens, P. A. Lane, and L. Krishnamurti. 2017. Health disparity in hematopoietic cell transplantation for sickle cell disease: Analyzing the association of insurance and socioeconomic status among children undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 130(Suppl 1):4636.

Anderson, M., and M. Asnani. 2013. “You just have to live with it”: Coping with sickle cell disease in Jamaica. Qualitative Health Research 23(5):655–664.

Asiri, E., M. Khalifa, S. A. Shabir, M. N. Hossain, U. Iqbal, and M. Househ. 2017. Sharing sensitive health information through social media in the Arab world. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 29(1):68–74.

Asnani, M. R., J. Knight Madden, M. Reid, L. G. Greene, and P. Lyew-Ayee. 2017. Socioenvironmental exposures and health outcomes among persons with sickle cell disease. PLOS ONE 12(4):e0175260.

Autor, D. H., and M. G. Duggan. 2003. The rise in the disability rolls and the decline in unemployment. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(1):157–206.

Bahr, N. C., and J. Song. 2015. The effect of structural violence on patients with sickle cell disease. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 26(3):648–661.

Baicker, K., and A. Finkelstein. 2011. The effects of Medicaid coverage—Learning from the Oregon experiment. New England Journal of Medicine 365(8):683–685.

Ballas, S. K. 2009. The cost of health care for patients with sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology 84:320–322.

Ballas, S. K., R. L. Bauserman, W. F. McCarthy, and M. A. Waclawiw. 2010. The impact of hydroxyurea on career and employment of patients with sickle cell anemia. Journal of the National Medical Association 102(11):993–999.

Bediako, S., and T. King-Meadows. 2016. Public support for sickle-cell disease funding: Does race matter? Race and Social Problems 8.

Bediako, S. M., and K. R. Moffitt. 2011. Race and social attitudes about sickle cell disease. Ethnicity and Health 16(4–5):423–429.

Bediako, S. M., L. Lattimer, C. Haywood, Jr., N. Ratanawongsa, S. Lanzkron, and M. C. Beach. 2011. Religious coping and hospital admissions among adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 34(2):120–127.

Bediako, S. M., S. Lanzkron, M. Diener-West, G. Onojobi, M. C. Beach, and C. Haywood, Jr. 2016. The measure of sickle cell stigma: Initial findings from the Improving Patient Outcomes through Respect and Trust study. Journal of Health Psychology 21(5):808–820.

Berkelhammer, L. D., A. L. Williamson, S. D. Sanford, C. L. Dirksen, W. G. Sharp, A. S. Margulies, and R. A. Prengler. 2007. Neurocognitive sequelae of pediatric sickle cell disease: A review of the literature. Child Neuropsychology 13(2):120–131.

Bills, S. E., J. Schatz, S. J. Hardy, and L. Reinman. 2019. Social-environmental factors and cognitive and behavioral functioning in pediatric sickle cell disease. Child Neuropsychology 26(1):83–99.

BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics). 2020. Databases, tables & calculators by subject. https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000 (accessed March 9, 2020).

Boulet, S. L., E. A. Yanni, M. S. Creary, and R. S. Olney. 2010. Health status and healthcare use in a national sample of children with sickle cell disease. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 38(4 Suppl):S528–S535.

Bugarin-Estrada, E., A. G. De León, J. M. Yáñez-Reyes, P. R. Colunga-Pedraza, and D. Gómez-Almaguer. 2019. Assessing patients’ knowledge and attitudes towards HSCT in an outpatient-based transplant center in Mexico. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 25(3):S301.

Bulgin, D., P. Tanabe, and C. Jenerette. 2018. Stigma of sickle cell disease: A systematic review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 39(8):675–686.

Burgess, D. J., M. van Ryn, M. Crowley-Matoka, and J. Malat. 2006. Understanding the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in pain treatment: Insights from dual process models of stereotyping. Pain Medicine 7(2):119–134.

Burgess, D., M. van Ryn, J. Dovidio, and S. Saha. 2007. Reducing racial bias among health care providers: Lessons from social-cognitive psychology. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22(6):882–887.

Clayton-Jones, D., and K. Haglund. 2016. The role of spirituality and religiosity in persons living with sickle cell disease: A review of the literature. Journal of Holistic Nursing 34(4):351–360.

Clayton-Jones, D., K. Haglund, R. Belknap, J. Schaefer, and A. Thompson. 2016. Spirituality and religiosity in adolescents living with sickle cell disease. Western Journal of Nursing Research 38(6):686–703.

Clemans-Cope, L., J. Holahan, and R. Garfield. 2016. Medicaid spending growth compared to other payers: A look at the evidence. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Cobo, V. A., C. A. Chapadeiro, J. B. Ribeiro, H. Moraes-Souza, and P. R. Martins. 2013. Sexuality and sickle cell anemia. Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia 35(2):89–93.

Cole, P. L. 2007. Black women and sickle cell disease: Implications for mental health disparities research. Californian Journal of Health Promotion 5:24–39.

Copeland, D. 2020. Drug-seeking: A literature review (and an exemplar of stigmatization in nursing). Nursing Inquiry 27(1):e12329.

Cotton, S., D. Grossoehme, S. L. Rosenthal, M. E. McGrady, Y. H. Roberts, J. Hines, M. S. Yi, and J. Tsevat. 2009. Religious/spiritual coping in adolescents with sickle cell disease: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology 31(5):313–318.

Creary, S., I. Adan, J. Stanek, S. H. O’Brien, D. J. Chisolm, T. Jeffries, K. Zajo, and E. Varga. 2017. Sickle cell trait knowledge and health literacy in caregivers who receive in-person sickle cell trait education. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine 5(6):692–699.

Epping, A. S., M. P. Myrvik, R. F. Newby, J. A. Panepinto, A. M. Brandow, and J. P. Scott. 2013. Academic attainment findings in children with sickle cell disease. Journal of School Health 83(8):548–553.

Finkelstein, A., S. Taubman, B. Wright, M. Bernstein, J. Gruber, J. P. Newhouse, H. Allen, and K. Baicker. 2012. The Oregon health insurance experiment: Evidence from the first year. Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(3):1057–1106.