6

Delivering High-Quality Sickle Cell Disease Care with a Prepared Workforce

There needs to be a concise way of capturing that information and understanding what the implications are of different treatments and different delivery systems on different people, capture that somehow, and be able to feed that back to the clinician and the patient that are in the midst of trying to make a really important treatment decision.

—Sara van G. (Open Session Panelist)

High-quality care for individuals living with sickle cell disease (SCD) should be evidence-based and accompanied by clear, measurable metrics that assess quality and improve performance. Care should be delivered by a well-trained workforce that is willing and able to provide the necessary services. Chapter 4 discussed the myriad acute and chronic complications that individuals living with SCD experience, and Chapter 5 detailed the comprehensive health care and health-related services that individuals living with SCD and sickle cell trait (SCT) need for optimal health outcomes. This chapter examines the state of evidence associated with clinical practice guidelines for managing the care of children and adults with SCD and the current state of health system performance assessment in delivering those services. This chapter also discusses strategies for addressing the obstacles to developing a cadre of health professionals who are prepared to deliver high-quality care. As discussed in Chapter 5, the committee recommends the use of a multidisciplinary team of providers to address the complex care needs of individuals living with SCD.

Some health care providers may be uncomfortable with providing SCD care because of a lack of knowledge and understanding about the clinical condition and the affected population. Clinical practice guidelines are an effective way of standardizing care and informing health care providers (especially non-experts) of the appropriate services that individuals living with SCD need. Commensurate endorsed quality metrics allow individual providers and systems to measure how well they adhere to available guidelines in providing such care and the consistency of this application to “every patient, every time.”

GUIDELINES FOR HIGH-QUALITY SCD CARE

Introduction

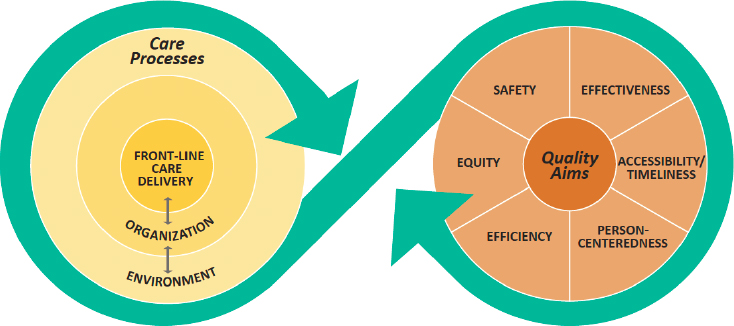

The discussion in this section is guided by the quality framework from two prior National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) publications, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (IOM, 2001) and Crossing the Global Quality Chasm: Improving Health Care Worldwide (NASEM, 2018). As noted in Figure 6-1, achieving quality requires ongoing attention by the health care system to provide care that is safe, effective, accessible/timely, efficient, equitable, and person-centered (NASEM, 2018).

Health care organizations and clinicians assess how well they are achieving these quality aims by assessing performance on metrics indicative of high-quality care. To foster the delivery of high-quality SCD care, health care providers need information and tools that synthesize available knowledge into clinical practice, and clinicians, organizations, and payers

SOURCE: NASEM, 2018.

need to be able to measure, reward, and identify opportunities for improving quality. Quality measures, performance indicators, and clinical practice guidelines are all relevant tools. Where there is a strong evidence base, defined as well-conducted randomized controlled trials and robust data to support performance tracking, these evidence-based SCD services can be defined as quality measures.

Quality measures are tools that help us measure or quantify health care processes, outcomes, patient perceptions, and organizational structure and/or systems that are associated with the ability to provide high-quality health care and/or that relate to one or more quality goals for health care. (CMS, 2020)

There are currently two measures for SCD care that have been endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF) (discussed in this chapter). Quality or performance indicators are “standardized evidence-based measures of health care quality that can be used … to measure and track clinical performance and outcomes” (AHRQ, n.d.). Quality indicators are used to benchmark actual performance against recommended practices; these are collected for reporting purposes and may be tied to payment. When the evidence base is insufficiently robust or still being gathered for services that the expert consensus sees as beneficial, clinical practice guidelines can be developed to guide care delivery. “Clinical practice guidelines are statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence [and expert opinion] and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options” (IOM, 2011a, p. 15). These guidelines help to standardize care by translating the existing research into recommendations for clinicians on the most beneficial services for different patient populations.

The structural aspects of health system design, such as the availability of a trained workforce and the use of data collection systems, are critical to adopting, measuring, and implementing quality measures and performance indicators.

Development of SCD-Specific Clinical Guidelines

As early as 1972 there were efforts to provide treatment guidelines for SCD, which were led by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and a group of funded investigators who were aligned with the establishment of the SCD comprehensive care centers (Prabhakar et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2006). In 1984 NHLBI published the first set of national guidelines for SCD management, which were subsequently updated in 1989, 1995, 1999, and 2002 (NHLBI, 2002). In 2002 the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP’s) Section on Hematology/Oncology and its Committee on Genetics published guidelines specific to SCD management for children with SCD (AAP, 2002).

In 2009 NHLBI convened an expert panel to develop guidelines for SCD management, which included health care professionals in areas such as pediatric and adult hematology, family medicine, and evidence-based medicine (Yawn et al., 2014). The expert panel, along with an independent methodology committee, reviewed the literature, rated the quality of evidence, and evaluated the strength of the recommendations. The quality of evidence was assessed using a modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework (Balshem et al., 2011). The NHLBI expert panel’s process adapts the GRADE process and rates the quality of recommendations as “strong,” “moderate,” or “weak.” The panel therefore added the “moderate” category to the regular GRADE framework of “strong” or “weak” recommendations to capture research that is from either low-quality randomized controlled trials or large, well-conducted observational studies. The expert panel also made consensus recommendations based on evidence-based practice guidelines from other entities, such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (Yawn et al., 2014).

Before finalizing its recommendations, the expert panel sought input from a number of associations with expertise in SCD, including AAP, the American Society of Hematology (ASH), and the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology (ASPHO). The resulting guidelines, Evidence-Based Management of Sickle Cell Disease, were published in 2014 (Yawn et al., 2014). Highlights of the NHLBI clinical guidelines covering health maintenance, the management of acute and chronic complications associated with SCD, and the use of hydroxyurea (HU) and transfusion therapy is included in Box 6-1.

Only a few of the strongly recommended NHLBI guidelines are supported by high-quality evidence. The majority of the recommended health care services had moderate or low evidence, indicating a huge gap in the evidence base for SCD interventions. Despite these gaps, the expert panel indicated that moderate-strength recommendations can be used to develop protocols to guide care delivery (Yawn et al., 2014). Recommended services with low-quality evidence represent areas where some variation in care may be acceptable because the services may be appropriate for only a subset of the SCD population. There is a need to generate research to fill in the evidence gaps for strongly recommended services where the supporting evidence base was moderate or weak or for services with moderate or weak recommendations.

Despite the NHLBI guidelines being a considerable contribution to improving the quality of care delivered, experts have noted that they have shortcomings, which offer valuable lessons for developing the next round of clinical guidelines for SCD. Citing recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, which offers criteria by which guidelines should be assessed, experts note that the NHLBI panel did not include patient representation, thus missing

the opportunity to solicit patient perspective and preferences. Additionally, the perspective of health professional associations representing clinical specialties that have expertise in the management of some of the clinical complications associated with SCD (e.g., chronic kidney disease [CKD], pulmonary hypertension, obstructive lung disease, and stroke) was not solicited in the development of the guidelines (DeBaun, 2014; Thompson, 2014). Also, there are prevalent SCD complications that are notably missing from the NHLBI guidelines, such as asthma, screening for and management of pulmonary hypertension, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (DeBaun, 2014; Thompson, 2014).

In addition to the 2014 NHLBI guidelines, ASH initiated an effort in 2016 to develop guidelines for screening, diagnosis, and management for five SCD-related areas: transfusion support, cardiopulmonary and kidney disease, cerebrovascular disease, pain, and stem cell transplantation. The Mayo Clinic Evidence-Based Practice Research Center led the systematic review of evidence for the ASH work. At the time of the development of this report, ASH had released guidelines for the screening, diagnosis, and management of SCD-related cardiopulmonary and renal complications (Liem et al., 2019) and transfusion support (Chou et al., 2020). Final guidelines are in development from ASH for cerebrovascular disease, transplantation, and the management of acute and chronic pain (ASH, n.d.).

National Quality Forum–Endorsed SCD-Specific Measures

NQF was created in 1999 in response to the report of the President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Healthcare Industry (NQF, n.d.c). The commission concluded that an organization like NQF should be created to improve the measurement and reporting of quality health care indicators. An NQF endorsement of quality measures signifies a rigorous review of the science and evidence base supporting the measure and input from key stakeholders, including patients and families, to develop consensus about measures that warrant a “best in class” designation (NQF, n.d.a).

NQF-endorsed measures are used widely at the federal, state, and local levels for payment and reporting. Currently, NQF has endorsed two measures related to SCD for measuring high-quality care for children (NQF, 2018):

- NQF measure #2797, “Transcranial Doppler Ultrasonography Screening among Children with Sickle Cell Anemia: The percentage of children ages 2 through 15 years old with sickle cell anemia (Hemoglobin SS) who received at least one transcranial Doppler (TCD) screening within a year.”

- NQF measure #3166, “Antibiotic Prophylaxis Among Children with Sickle Cell Anemia: The percentage of children ages 3 months to 5 years old with sickle cell anemia (SCA, hemoglobin [Hb] SS) who were dispensed appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis for at least 300 days within the measurement year.”

The evidence on adherence to NQF-endorsed measures in SCD care is not robust. The following section discusses the available information on adherence to these measures.

Transcranial Doppler Screening

TCD screening is a significant advance in identifying and preventing stroke in children and adolescents with SCD. However, studies have consistently demonstrated that fewer than half of all eligible patients have received proper TCD screening. Raphael et al. (2008) found that the average yearly TCD screening rate for eligible pediatric patients (207 in the evaluation) was 45 percent. Eckrich et al. (2013) found that among a cohort of 338 children with SCD who were publicly insured, the cumulative incidence rates of annual TCD screening increased from 2.5 percent in 1997 to 68.3 percent in 2008. While screening increased significantly over the study period, 31 percent of children did not receive TCD screening over the entire study period. Reeves et al. (2016) conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study using Medicaid claims data from 2005 to 2010 and found that among 4,775 children and adolescents (2–16 years old), TCD screening rates increased over the 6-year study period from 22 percent to 44 percent (p < 0.001). The authors also found that screening rates varied substantially across states and that the receipt of well-child visits was associated with higher odds of a TCD screening. In a retrospective chart review of 195 children ages 2–16 years who were eligible for TCD screening, Hussain et al. (2015) found that only 41 percent had achieved the standard of care. Bundy et al. (2016) conducted a retrospective cohort study of children aged 2–5 years and found that only 25 percent of the children had received one or more TCD screenings during the 14-month study period. The children who were most likely to receive a TCD (42 percent) were those with two or more hematologist visits.

A lack of knowledge about TCD guidelines has been identified as a barrier to TCD screening among some physicians. Reeves et al. (2015) conducted a survey of primary care, neurology, and hematology physicians to explore the factors that influence physician adherence to TCD screening guidelines for children with SCD. They found variation in the degree to which physicians felt well informed about screening guidelines. Of the 276 survey respondents, more primary care providers (PCPs) reported

not feeling well informed (66 percent) than neurologists (25 percent) and hematologists (6 percent). Bollinger et al. (2011) found that a lack of knowledge in caregivers may also be a barrier that prevents children with SCD from receiving annual TCD screening.

Penicillin Prophylaxis

Infants and young children with SCD are susceptible to bacteremia and meningitis due to Streptococcus pneumonia; penicillin prophylaxis decreases episodes of pneumococcal bacteremia. Kanter et al. (2017) evaluated commercial and Medicaid claims data for children with SCD and found that more than 80 percent of insured children aged 1–5 received a prescription for penicillin prophylaxis. However, other studies suggest that a prescription does not guarantee receipt of or optimal adherence to the medication, so the rates of adherence are much lower. For example, Beverung et al. (2014) conducted a retrospective cohort study using Wisconsin Medicaid claims data and found that only 18 percent of eligible children 5 years or older were adherent, as defined by a medication possession ratio1 of greater than 80 percent (18.18%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 11.31–25.05). Bundy et al. (2016) conducted a retrospective cohort study (using Maryland Medicaid claims data) of 266 children aged 2–5 years and found that 30 percent had consistently filled prophylactic antibiotic prescriptions. Having more than two hematologist visits or generalist visits that were not for well-child care was associated with more consistent antibiotic prophylaxis. Finally, Reeves et al. (2018) evaluated Medicaid claims data from six states for children aged 3 months to 5 years with SCA (2005–2012) and found that only 18 percent received at least 300 days of antibiotics. Furthermore, well-child visits were found to be associated with increased odds of receiving at least 300 days of antibiotics (odds ratio [OR] 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.13).

These findings indicate that there is a need to promote adherence to NQF-endorsed measures. Some strategies for promoting uptake of measures are discussed later in the chapter.

Recommendations Adapted from Other Stakeholder Groups

Several other associations for health professionals have developed evidence-based recommendations for managing care for adults and children that are relevant for the SCD population. Organizations whose recommendations appear in the 2014 NHLBI guidelines include USPSTF, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the World Health Organization, the

___________________

1 The medication possession ratio is calculated as follows: (sum of days supplied) / [(number of days from first encounter) – (number of days hospitalized)] (Beverung et al., 2014).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the American Pain Society. The consensus-adapted recommendations for SCD care pertain primarily to beneficial preventive services and include immunizations, screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) and retinopathy, contraception use, reproductive counseling, and opioid use during pregnancy, as shown in Table 6-1. The NHLBI guidelines also included adapted consensus guidelines for chronic pain management. As with other recommended services, the National Academies SCD committee’s literature review identified very little data on adherence to recommended vaccinations and preventive services in the SCD population. The next section briefly reviews the available information.

Immunizations

Pneumococcal vaccination

Individuals with SCD are at extremely high risk of fatal pneumococcal infection and therefore are routinely immunized with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV, sometimes referred to as PPV). Neunert et al. (2016) examined retrospective medical record and claims data to identify eligible children with SCA aged 24–36 months between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2008; they found that of 125 children, 73.6 percent received PPV as recommended. Similarly, Beverung et al. (2014) found that 77 percent of eligible children received PCV7,2 and 50 percent of children less than 18 years of age received PPSV23 at least once in a 4-year period, whereas 38 percent of adults over 18 years of age had received PPSV23 at least once in a 4-year period. Ter-Minassian et al. (2019) reviewed the medical records of all persons with SCD seen at Kaiser Permanente Mid-Atlantic States (KPMAS) and the Adult Sickle Cell Disease Program at Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2015, to assess quality of care. Among 146 KPMAS patients, 85 percent had documentation of ever receiving PCV13 or PPSV23, but only 52 percent had received both. Among 308 JHH patients, 87 percent had documentation of receipt of either PCV13 or PPSV23, but only 30 percent had both.

Influenza vaccine

Influenza vaccination is recommended in the United States for everyone 6 months and older and may be even more important for people with SCD, for whom infections can be more serious and associated with additional SCD-related complications. There are several studies evaluating the rates of influenza vaccination for persons with SCD.

___________________

2 PCV7 was the first pneumococcal conjugate vaccine licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine recommended currently is PCV13, which offers protection against an increased number of types of pneumococcal infection. For more information, see https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/public/index.html (accessed December 23, 2019).

Beverung et al. (2014) found that only 30.3 percent of children and 11.6 percent of adults were considered adherent3 over a 5-year period. The percent of non-adherence (zero vaccinations per influenza season) among children was 17.5 percent and 38.2 percent in adults (Beverung et al., 2014). Bundy et al. (2016) conducted a retrospective cohort study of children aged 2–5 years and found that 41 percent received at least one influenza immunization during the study period. Children with two or more hematologist visits were most likely to be immunized (62 percent versus 35 percent for children without a hematologist visit).

Ter-Minassian et al. (2019) reviewed the medical records of persons with SCD seen at KPMAS and JHH for adherence to seasonal influenza vaccination. They found documentation of influenza vaccination in 75 percent of KPMAS participants and 51 percent of JHH participants.

Meningococcal vaccination

Ter-Minassian et al. (2019) also reviewed the medical records of persons with SCD seen at KPMAS and JHH to assess meningococcal vaccination rates. Vaccination rates were low prior to 2016, with only 24 percent of KPMAS and 17 percent of JHH patients having had documentation of meningococcal vaccination.

The little evidence available on adherence to immunization guidelines suggests that there is room to promote adherence to recommended immunizations for individuals with SCD. At least one of the consensus-adapted recommendations—influenza vaccination—is NQF endorsed, meaning that it can be included in reporting and payment programs to promote accountability and adherence. The National Academies SCD committee was able to identify only limited evidence on adherence to the other strongly recommended services for SCD.

PATIENT-CENTERED DIMENSIONS OF HIGH-QUALITY CARE

The available guidelines for management of SCD focus primarily on managing the disease and associated complications and thus miss other important dimensions of high-quality care that pertain to the impact of the disease on an individual’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL) or their experience with the health care system, especially in care transitions for children from pediatric care into adult care.

___________________

3 “Adherence rate was calculated by dividing the number of influenza vaccines received by the number of eligible influenza seasons.… Individuals were considered adherent if their vaccination rate was greater or equal to 0.80 per influenza season.” Other categories of adherence were moderate (vaccination rate of 0.05–0.79 per season) and low (vaccination rate of 0.01–0.49 per season) (Beverung et al., 2014).

Health-Related Quality of Life

HRQOL refers to the effects of health, illness, and treatment on an individual’s quality of life (QOL) (Ferrans et al., 2005; Wilson and Cleary, 1995). Seminal work on HRQOL proposed measuring patient outcomes in five areas: biological function, symptoms, functional status, general health perceptions, and overall QOL (Ferrans et al., 2005; Wilson and Cleary, 1995).

Tools for measuring HRQOL have been adapted over time to assess the health effects of specific illnesses or conditions. In 2002 stakeholders participating in NHLBI gatherings that were focused on the treatment needs of individuals living with SCD identified the need to document patient-reported outcomes (PROs) (Treadwell et al., 2014). In response to this need, efforts began to develop SCD-specific tools as part of an NHLBI-sponsored Adult Sickle Cell Quality of Life Measurement Information System (ASCQ-Me) project (Treadwell et al., 2014). ASCQ-Me was developed as a set of self-administered items that assess the impact of SCD on adult functioning (Keller et al., 2017; Treadwell et al., 2014). The health domains assessed by the ASCQ-Me include emotional impact, pain impact, sleep impact, social functioning impact, stiffness impact, pain episodes, and an SCD medical history checklist (Keller et al., 2017; Treadwell et al., 2014).4 In a recent systematic literature review of PRO instruments used in SCD, the ASCQ-Me was considered to have strong content validity and internal reliability and good construct validity with respect to psychometric properties (Sarri et al., 2018). The tool was recently validated in a UK population (Cooper et al., 2019).

In addition, to assess the experiences of adults living with SCD in accessing care and the quality of care received, the ASCQ-Me Quality of Care (ASCQ-Me QOC) tool was developed. The tool has four domains focusing on access, provider communication, emergency department (ED) care, and ED pain treatment. Results based on the ASCQ-Me QOC indicate that adults with SCD report deficiencies in ED care related to race and their disease condition (Evensen et al., 2016).

It should be noted that in the design of the ASCQ-Me QOC a number of domain questions (access and provider communication) are very similar to or identical to those found in the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS)5 surveys (Evensen et al., 2016). These surveys were designed to understand patient experiences with health care. There are a number of surveys; some surveys ask about a patient’s experience with

___________________

4 For more information on the tool, see www.HealthMeasures.net/ASCQ-Me (accessed January 6, 2020).

5 For more information on the CAHPS surveys, see https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/aboutcahps/cahps-program/index.html (accessed January 6, 2020).

providers (clinician and groups), while others ask about experiences with care delivered in facilities (e.g., adult and child hospitals). Supplements to these surveys have been developed, such as one that provides questions specific to children with chronic conditions. While a CAHPS survey specific to SCD has not been developed (e.g., parallel to the CAHPS Cancer Care Survey6), items from the various surveys could be helpful in understanding the patient experience of care for individuals with SCD.

Efforts to develop a tool to assess the HRQOL of children living with SCD resulted in the development of the Pediatric QOL™—Sickle Cell Disease Module (PedsQL™ SCD Module). The module is a self- or parent proxy-administered survey that assesses HRQOL in children aged 2–18 years (Panepinto et al., 2013). The PedsQL™ SCD Module comprises nine scales: (1) pain and hurt, (2) pain impact, (3) pain management and control, (4) worry I, (5) worry II, (6) emotions, (7) treatment, (8) communication I, and (9) communication II (Panepinto et al., 2013). In the systematic review of PRO instruments, the PedsQL™ SCD Module was found to have strong internal reliability, but its other psychometric properties were unclear (Sarri et al., 2018). The SCD module complements other non-SCD-specific PRO instruments such as the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales (Varni et al., 2001) and the PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale (Panepinto et al., 2014), which assess other aspects of HRQOL in children.

A number of other tools specific to the SCD population have been developed with a focus on pain and self-efficacy. With respect to pain assessment, Zempsky et al. (2013) developed the Sickle Cell Disease Pain Burden Interview–Youth for use in youth and young adults aged 7–21 years. The brief tool, which consists of seven items, is administered by interview and inquires about days of pain and the impact of pain in the past month. Questions assess the impact of pain on mood, functional ability, and QOL. The tool has strong internal reliability and good content validity, construct validity, and test-retest reliability (Sarri et al., 2018).

According to Edwards et al. (2001), disease self-efficacy refers to an individual’s beliefs about his or her ability to achieve a desired health outcome. With respect to SCD and self-efficacy, Clay and Telfair (2007) and Edwards et al. (2000) used a nine-item scale focusing on the ability of adults and adolescents living with SCD to engage in daily functional activities. They found that high levels of self-efficacy were related to fewer physical, psychological, and total SCD symptoms (Clay and Telfair, 2007; Edwards et al., 2000). The instrument was assessed as having strong internal reliability in the recent systematic review (Sarri et al., 2018).

___________________

6 For information on the CAHPS Cancer Care Survey, see https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveysguidance/cancer/index.html (accessed January 6, 2020).

The above-cited SCD-specific tools provide an opportunity to develop a better understanding of the burden that SCD imposes on the QOL of individuals living with SCD and their experiences with providers and health systems. HRQOL outcomes also point to areas of clinical practice that may need improvement, such as deficiencies in how patients are assessed and treated for pain in EDs as well as non-clinical interventions and strategies to better support individuals in developing self-efficacy, carrying out activities of daily living, and social functioning.

Patient Engagement in Care Through Shared Decision Making

Shared decision making (SDM) is defined as “a process of communication in which clinicians and patients work together to make informed health care decisions that align with what matters most to patients and their individual concerns, preferences, goals, and values” (NQF, n.d.b).7 NQF issued a national call to action to ensure that SDM in clinical practice is a standard of care for all patients (NQF, n.d.b). SDM in SCD care is critical but evolving.

Decisions about disease-modifying therapies for SCD often require patient adherence in order to be optimally effective (e.g., HU) or involve significant risks (e.g., bone marrow transplant, CRISPR gene editing). These decisions are complex and preference sensitive, and patients/families should be informed and involved in making them. This requires an effective partnership between patients and families and clinicians based on trust and clear communication.

Results from a study of physicians’ perceptions of patient decisional needs and physicians’ approaches to decision making showed that physicians tended to use two approaches to treatment-related decision making (Bakshi et al., 2017). One approach was characterized by the physician advocating for a specific treatment plan with the objective of convincing the patient to accept that plan. The second approach was characterized by the physician emphasizing the need to discuss all treatment approaches. Bakshi et al. (2017) found that which approach a physician used was influenced by a number of factors, including the characteristics of the patient, disease severity, the nature of the therapies, institutional frameworks, and other decision characteristics. Another study that directly observed dialogue about initiation of HU between patients and clinicians found that clinicians did not uniformly present the risks of HU and that patient concerns about

___________________

7 For more information on NQF shared decision making, see http://www.qualityforum.org/National_Quality_Partners_Shared_Decision_Making_Action_Team_.aspx (accessed January 6, 2020).

HU were not always raised and discussed (Lee et al., 2018). A recent qualitative study of patients’ perspectives on the process of deciding whether to take HU and physician communication found that providers who involved patients in SDM empowered those patients to start HU treatment (Jabour et al., 2019). However, patients who perceived that their providers were not attentive to their concerns reported having disengaged from HU treatment (Jabour et al., 2019).

Researchers are exploring ways to develop decision aids to assist in SDM. Crosby et al. (2015, 2019) developed an HU decision aid that increased HU knowledge and decreased decisional conflict. Other decision aids for transplant and non-transplant treatments exist for SCD (Sullivan et al., 2018). For example, Sickle Options is a website that provides information on treatment options, risks, and benefits and relates them to personal values.8 A Cochrane review of 105 studies on decision aids for a variety of clinical decisions found that when the aids are used, people improve their knowledge of options, feel better informed, and have a better understanding of what matters most to them (high-quality evidence), and they probably have more accurate expectations of the benefits and harms of options and participate more in decision making (moderate-quality evidence) (Stacey et al., 2017). Given the paucity of research in this area specific to SCD, there are ample research opportunities to examine SDM and the effectiveness of decision aids in improving patient knowledge and decision making in SCD care.

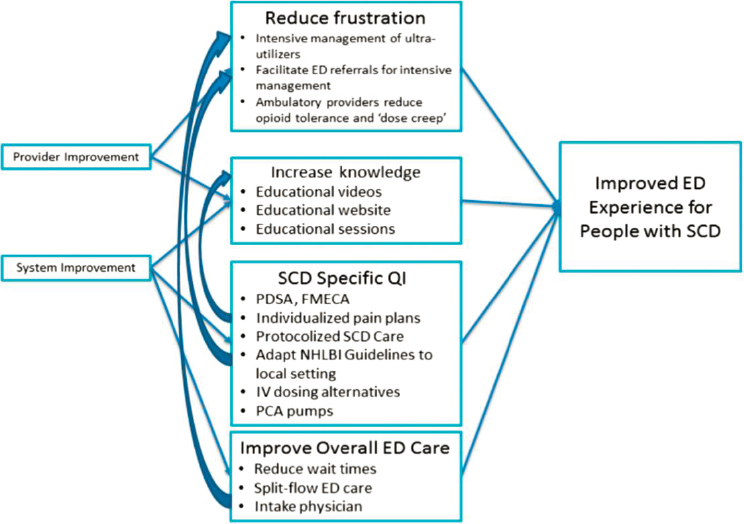

Pain Management

Pain management is a source of frustration for both patients and providers and an impetus for discrimination, confusion, and dissatisfaction; as noted by Anie et al. (2012, p. 1), “sickle cell pain assessment is a crucial and difficult task.” There are some best practices for pain control, but these have not been disseminated widely or implemented outside of institutions serving high numbers of patients with SCD. ASH is creating guidelines for treating SCD-related pain, but the recommendations are still in draft form (ASH, 2019).

There are a number of reasons that pain management for individuals living with SCD is difficult. For example, a number of researchers and health care professionals have noted the difficulty in treating the pain episodes of individuals living with SCD because of the subjectivity associated with the experience of pain (Okwerekwu and Skirvin, 2018). Many providers

___________________

8 For more information on Sickle Options, see http://sickleoptions.org/en_US (accessed January 6, 2020).

underestimate the severity of these pain episodes in spite of the fact that “pain management should be based on patient-reported severity,” according to the 2014 NHLBI sickle cell management guidelines (Yawn and John-Sowah, 2015).

There is also a great deal of variability in the intensity, duration, and frequency of pain episodes, as discussed in Chapter 4 (Geller and O’Connor, 2008). Given the challenges with defining, measuring, and treating pain episodes, it is not surprising that there is little in the quality improvement literature about effective pain management. Added to this is that clinician attitudes and race- and disease-based discrimination significantly affect the implementation of evidence-based guidelines (e.g., administering pain medication in the ED within 30 minutes) and clinical outcomes for individuals living with SCD.

Pain management for individuals living with SCD must be seen in the context of the current opioid crisis. Sinha et al. (2019), for example, collected qualitative data from 15 interview subjects about their perceptions of pain management from 2017 to 2018, after the 2016 CDC guidelines for chronic pain management were published. Interviewees reported that their opioid prescriptions were managed more closely by their health care providers and that their opioid use was monitored more closely than previously. This stigmatization of opioid use in managing SCD pain in light of the opioid crisis has negatively affected the care that these individuals are receiving (Sinha et al., 2019).

The National Academies has published several reports that can be used with this current report to create an effective system of care for people living with SCD and SCT, including Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001), Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (IOM, 2003), Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research (IOM, 2011b), and The Role of Nonpharmacological Approaches to Pain Management (NASEM, 2019), and Telfer and Kaya (2017) suggest an integrated approach to treating sickle cell pain in the absence of a standard protocol.

Transition from Pediatric to Adult Care

As described in Chapter 5, adolescents and young adults who transfer from pediatric to adult care encounter many challenges that affect their care. Individuals may lack the knowledge (e.g., SCD complication history) and skills (e.g., decision making, communication) needed to take an active role in their care and successfully navigate the adult health care system (Jordan et al., 2013). Compounding the transition to adult health care are the many other life transitions that young adults experience (e.g., emotional—establishing new friendships; social—living independently;

academic—graduating from high school/college/vocational program) (de Montalembert and Guitton, 2014). Despite the complexity of the transition to adult care, the field has identified several indicators of a successful transition for young adults living with SCD.

When I was in peds, I got amazing care. I was really encouraged to know … what worked for me. And then when I transition[ed] to adult, it was totally different. I started being accused of drug seeking just because I knew what dose of Dilaudid I needed in the ER.

—Teonna W. (Open Session Panelist)

Indicators of a Successful Transition

National organizations have developed position statements, guidance, and white papers defining a high-quality transition process for youth with chronic conditions and individuals with SCD. One available source of guidance, for example, is Got Transition™, discussed in Chapter 5. NHLBI provides guidance on adolescent health care and transitions in its report The Management of Sickle Cell Disease. That guidance, developed by a multidisciplinary group of experts, highlights transition readiness based on developmental age, transition discussions before transfer, the introduction of adult providers in the pediatric setting, and a focus on the coordination of care (NHLBI, 2002). In 2015, ASPHO and the Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses developed a policy statement for the transition of individuals living with SCD from pediatric to adult health, which identifies the following elements as essential: transition planning, multidisciplinary transition team, transfer process, and confirmation of transfer. In 2017 an expert panel from the Sickle Cell Adult Provider network used a modified Delphi process to identify nine quality indicators for transition, including five that were identified by Oyeku and Faro (2017) in their review of SCD quality improvement indicators for transition from pediatric to adult care: (1) communication between pediatric and adult providers, (2) time to first visit at the adult provider, (3) patient self-efficacy, (4) QOL, and (5) trust with the adult provider (Oyeku and Faro, 2017; Sobota et al., 2017).

The efforts mentioned above to provide guidance and indicators for the transition from adolescent to adult care share common elements, suggesting agreement across the field and a strong foundation for the development of SCD transition quality indicators. Despite this agreement, transition metrics are not routinely collected and tracked across programs, which has resulted in variations in the quality of care in the United States and other countries (Treadwell et al., 2018). The next section briefly reviews some

additional outcomes and process indicators identified through the work of various organizations that can be measured and tracked to improve the quality of transitions.

Insurance coverage and access to adult providers

Young adults with SCD may have limited access to health insurance (de Montalembert and Guitton, 2014). They may lose their health insurance coverage as they move from their parents’ plan to their own. Enrolling in and maintaining health insurance, particularly public health insurance, can be a challenging and time-consuming process, as discussed in Chapter 2. This lack of or delay in obtaining insurance coverage is a significant obstacle in accessing care and may seriously affect quality and continuity of care as young adults may avoid regular care and become more reliant on urgent or emergency care.

Transition education and readiness assessment

There is a need to assess the quality of transition planning and preparation, as individuals with SCD are generally unprepared for transition. The implementation of the transition core elements appears to be challenging. Okumura et al. (2008) found that 89 percent of providers in the survey supported a systematic transition process, but Telfair et al. (2004a,b) found that only 67 percent reported integrating transition core elements in their practice.

It has been shown that young adults may have a poor understanding of their medical history (Williams et al., 2015). DeBaun and Telfair (2012) identified educational milestones for the transition period to improve the transition process. Milestones include the adolescent having knowledge about his or her SCD phenotype, having the ability to articulate the most important components of his or her medical history, being able to manage pain according to a pain plan, and being aware of preventive measures for SCD complication, to name a few (DeBaun and Telfair, 2012). Additional research is needed to describe the interplay between cognition and disease knowledge in pediatric SCD (Hood et al., 2019). Young adults are able to identify specific health topics and barriers (e.g., mistrust, maintaining health insurance, employment difficulties, and managing stress) to be addressed in an individualized transition program (Bemrich-Stolz et al., 2015). Despite high interest in learning about transition (Williams et al., 2015), young adults may not attend transition-specific activities (Sivaguru et al., 2015). Lebensburger et al. (2012) supports starting the transition process early to better meet the needs of the patients from the beginning.

Routine assessment of transition readiness is variable across the United States; only certain SCD clinics and centers have integrated this into usual care. Several tools for measuring transition readiness exist, including the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire and the Transition Intervention Program—Readiness for Transition assessment (Treadwell et al., 2016).

Communication/coordination of adult and pediatric providers

Inadequate communication between adult and pediatric providers may cause poor continuity of care (Treadwell et al., 2011), which sets the stage for recurrent hospitalizations, mistrust, and poorer health outcomes (Hunt and Sharma, 2010). Interventions targeting care coordination have led to improvements in the transfer of care and in overall quality. Hankins et al. (2012) piloted a transition program that helped adolescents identify an adult medical home. Data indicated that the program was feasible and showed promise for improving the transfer process. A patient-centered medical home may be another approach to improving coordination of transition care. In this model the pediatric provider conducts regular monitoring, documents complications and treatments, and communicates with an adult provider during and immediately after transition (Kelly et al., 2002).

Time to first visit with adult provider

Centers with well-established SCD transition programs use a registry to track eligibility, participation, and transfer completion. For example, the Duke University Medical Center conducted a retrospective chart review of individuals with SCD aged 18–23 years to identify care gaps (e.g., time to transfer), successful transition rates (completed appointment at an adult clinic 1 year post-transition), and associated factors (Hill et al., 2014). The data showed that only one-third of patients transitioned successfully and that a care gap exists for 18- to 20-year-olds (Hill et al., 2014). This study supports the importance of tracking individuals with SCD to improve the quality of care pre- and post-transition.

Quality of life

In the transition period, QOL indicators such as Pediatric QOL and Adult Sickle Cell QOL can help identify and prioritize health problems, facilitate discussions between the adolescent and providers, and identify areas needing greater medical, emotional, or social support.

Patient self-efficacy

Self-efficacy (the individual’s confidence in his or her ability to manage SCD on a daily basis) affects transition readiness (Treadwell et al., 2016). A 2015 review and 2016 multisite study found that youth with higher self-efficacy were more ready for transition (Molter and Abrahamson, 2015; Treadwell et al., 2016). Another 2015 study found that adults living with SCD reported improvements in autonomy and self-efficacy after transition (Bemrich-Stolz et al., 2015). Consequently, many transition programs target increasing patient self-management skills as a way of increasing self-efficacy. Moreover, 50 percent of SCD clinics responding to a survey about transition services and needs reported that they had a written list of desirable self-management skills (Sobota et al., 2011).

To better prepare young adults with SCD for the transfer to adult care, there is a need to help them develop increased confidence in their life skills.

In an effort to overcome neurocognitive or health literacy challenges that may interfere with attaining self-management skills (e.g., medication adherence), some programs have begun to integrate technology (e.g., videos, apps) into their care. Additional research is needed to understand essential components for increasing self-management skills and the most effective modalities (e.g., groups, in person, online, mobile apps) (Matthie et al., 2015).

PROMOTING UPTAKE OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SCD CARE

There are a number of beneficial and effective services recommended for SCD care; two of these recommended services are endorsed by NQF as quality measures. Several other specialty organizations (ASH, ASPHO, American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), AAP, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians) and non-specialty organizations and governmental entities (CDC, USPSTF, NHLBI) have also developed consensus guidelines/recommendations to support quality metrics for the general population and SCD that should be applied consistently to the SCD population. In 2011 a panel of experts recommended 41 indicators for managing SCD care for children, including a subset of eight indicators9 that they believe will result in considerable improvement on QOL and health outcomes for children with SCD (Wang et al., 2011). The 41 indicators covered 18 topic areas, including some of the areas identified throughout this report as having opportunity for improvement, such as genetic counseling, transition to adult care, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and comprehensive planning (Wang et al., 2011). These prior efforts can inform future attempts to expand indicators for high-quality SCD care. Internationally, standards of SCD care developed by the National Health Service and the Sickle Cell Society in the United Kingdom are valuable resources for SCD care management in the United States (Public Health England, 2019; Sickle Cell Society, 2018).

Clinical guidelines and metrics that are supported by evidence are, however, not widely applied because there is a lack of systematic efforts to foster the development of evidence-based learnings from iterative quality improvement in the SCD management. As a result, the quality and outcomes for SCD lag behind those of other rare, inheritable, and chronic diseases, such as cystic fibrosis (CF), hemophilia, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. There is a need to implement and measure these underused guidelines and metrics.

The two NQF-endorsed measures can be immediately measured for public reporting and tied to payment. For 2019 the Centers for Medicare &

___________________

9 The eight indicators cover the following topics: timely assessment and treatment of pain and fever, comprehensive planning, penicillin prophylaxis, transfusion, and the transition to adult care (Wang et al., 2011).

Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that it would be maintaining the current core set of pediatric quality measures that states use for reporting the performance of Medicaid programs (CMS, 2018). Freed (2019) said CMS had “missed a historic opportunity to definitively address a national shame, the poor state of care provided to children with sickle cell disease,” because the Pediatric Measure Application Partnership (P-MAP) had recommended certain changes, such as to include the two NQF-endorsed measures in the core measure set. P-MAP is a multi-stakeholder panel that guides the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in selecting performance measurements for federal health programs.

QUALITY INDICATORS FOR SCT AND GENETIC COUNSELING FOR SCD AND SCT

Although SCT may be considered clinically benign, it affects nearly 300 million individuals worldwide (Grant et al., 2011). As stated in Chapter 3, all U.S. newborn screening (NBS) programs are state-based, so there are no requirements for them to report data to a national source. There are also no federal standards or consensus definitions for reporting or governing NBS data (Therrell et al., 2015). In 2009, CDC hosted a meeting on SCT and invited key stakeholders to engage in discussions to identify gaps in public health, health care delivery, epidemiologic research,10 and community-based outreach and to develop an agenda for the future for SCT. The meeting deliberations culminated in recommendations for community awareness and education, screening practices, ethical and legal issues, prevention of negative health outcomes, and epidemiological and clinical research (Grant et al., 2011). The National Academies SCD committee was unable to find any data on adherence to these guidelines other than efforts referenced in Chapters 3 and 5 and found no studies specifically examining quality.

Many individuals with SCT are identified through state NBS programs. Notification of NBS results varies widely by state. No best practices have yet been established for notifying families of results that improve a family’s ability to inform their child about his or her SCT and educate him or her about the implications. Programs that inform families of NBS results in person should be explored (Salm et al., 2012).

There are no guidelines or best practices for genetic counseling for individuals with SCT during adolescence or young adulthood, yet this is typically the time when family planning and decisions about contraception occur. When providing genetic counseling to women about their risk for having a child with SCD, it is important that the correct test is used

___________________

10 For more information on epidemiological research, see https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/cohort-effect (accessed August 3, 2020).

to assess hemoglobinopathy trait status. Hemoglobin electrophoresis and other hemoglobin quantitative separation methods are best (Naik and Haywood, 2015). Solubility tests, such as Sickledex and Sickle Cell Screen, are misleading. These tests do not distinguish SCD from SCT, nor do they detect the presence of other hemoglobin variants that may place a couple at risk for having a child with SCD, and false negatives and false positives are common. These tests should not be used for genetic counseling. Protocols for screening children and adults for SCD or SCT should use hemoglobin electrophoresis or other reliable hemoglobin separation methods, and organizations such as the National Collegiate Athletic Association and others should adopt this screening approach (Tubman and Field, 2015). Other tests such as a complete blood count may be necessary to detect beta thalassemia carriers, who also need genetic counseling. Quality indicators should be developed and tracked to ensure that appropriate tests are used, particularly for pregnant women (ACOG, 2017). In addition, individuals should be screened once in their lifetime, with confirmatory testing when appropriate. Repeated testing for a genetic state is not cost effective. Methods to store information about SCT and other hemoglobinopathy traits should be part of the health record, and NBS results should be stored and available to individuals when requested.

The National Library of Medicine developed a Newborn Screening Coding and Terminology Guide to standardize NBS test results (NLM, 2018). Another effort to standardize definition and data collection is the Hemoglobinopathy Uniform Medical Language Ontology (HUMLO) Project (NIH, 2008). The goal of HUMLO was to create an ontology for researchers and federal programs. Similarly, the PhenX Project sought to identify consensus measures for genetics that could be used in large-scale genomic studies (Hamilton et al., 2011).

There are no consensus guidelines on when or how to screen (e.g., methods, specific tests) individuals living with SCT for clinical complications (see Chapter 4). This is a notable gap in the literature, particularly because there is strong evidence for some clinical complications (e.g., CKD) (Naik et al., 2018b).

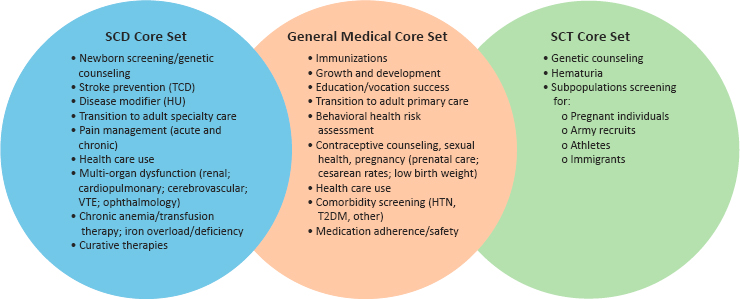

An NQF-like endorsement mechanism is needed for all indicators of high-quality SCD services across the life span, similar to what has been done for asthma, children from low-income families, and other groups. This will require developing measure sets, similar to the ones in Figure 6-2, that incorporate core metrics relevant for all adults and children in addition to core metrics specifically relevant for individuals with SCD and SCT.

Developing and accrediting comprehensive care centers will facilitate adherence to quality indicators and existing and future quality measures, because these centers’ accreditation and performance can be tied to providing recommended services for SCD.

NOTE: HTN = hypertension; HU = hydroxyurea; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus; TCD = transcranial Doppler screening; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

SUMMARY

The evidence supporting the guidelines for SCD care is highly variable, relying on expert consensus but highlighting research gaps. The evidence for a comprehensive, systematic approach to quality care delivery for SCD is lacking, and the science of quality in SCD care appears to lag behind other diseases in several areas:

- The majority of SCD quality indicators are supported with poor-quality evidence, often with consensus expert recommendation as the highest level of evidence available.

- There are multiple sets of quality indicators, but none are comprehensive or universally accepted or applied.

- There is a lack of data streams to measure adherence to quality indicators, requirements for centers to report their adherence to quality metrics, incentives to promote reporting, and public transparency of reports when available.

- There is neither funding nor a priority established for quality metrics in SCD, even in the face of poor performance of clinical systems. Furthermore, there has been no formal, systematic quality improvement of training programs.

There is no metric to support compassionate care in the health care system, particularly in light of the outright mistreatment of individuals with SCD presenting with pain—the most notable feature of SCD outside of death. Continued inaction over the past 18 years and a lack of required certifications has set back quality in SCD care, perpetuated mistrust of the health care system, and delayed the development of life-saving treatments

and standards of care. In the absence of robust evidence from randomized controlled trials, the quality of health care can be improved by leveraging learning collaboratives across health systems to foster the consistent application of available evidence-based guidelines and to obtain data on the effectiveness of consensus guidelines in improving outcomes. The disparities in applying available guideline-based care, the lack of care coordination within the delivery system and across the life span, and other structural deficiencies all contribute to poor outcomes in the SCD population. Defining and measuring high-quality care is a key step to improving outcomes.

THE AVAILABILITY OF A TRAINED AND PREPARED WORKFORCE

The committee believes that achieving the goal of delivering high-quality SCD health care to all will rest in part on the availability of an active, highly trained workforce. This section will describe the challenges associated with accessing such a workforce.

Multidisciplinary Teams

Treatment for people with SCD is best managed by a multidisciplinary team of professionals delivering comprehensive care. Traditionally, hematologists coordinate the management of care and liaise with other specialties, as they generally have the most familiarity with the multiple SCD complications and presentations (Grosse et al., 2009). In addition to medical providers, the members of the comprehensive care team should include behavioral health providers (e.g., psychologists, neuropsychologists, and psychiatrists), social workers, dietitians, physiotherapists, massage therapists, community health workers (CHWs), care coordinators, and school liaison officers. Furthermore, strong partnerships with community health services and voluntary agencies enhance the likelihood of the multidisciplinary team’s success (Okpala et al., 2002). Comprehensive care has several beneficial effects, such as improved QOL, reduced ED visits, and shorter hospital admissions (Okpala et al., 2002; Vichinsky, 1991).

The importance of social services and psychological support should not be underestimated. Services that may be needed include psychological treatment (e.g., mindfulness techniques and cognitive behavioral therapy), neuropsychological testing, general information and advice, disability assistance, transportation, financial allowances, practical help in the home or school, and assistance with care transition. However, access to these services is often institution dependent and further reduced in adult care. Such services often require specialized clinical experience and technical expertise and are harder to access outside of comprehensive care centers.

Although SCD is more common than CF in the United States, only a minority of individuals with SCD are seen at specialized centers (Smith et al., 2006). In stark contrast, there are more than 115 comprehensive, multidisciplinary CF care centers in the United States that are accredited and funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF). CFF also maintains a national registry of CF patients who attend accredited centers (CFF, 2019). Using expert panels made up of physicians and scientists, it published consensus guidelines for best practices in CF care (e.g., guidelines for the management of infants with CF) (CFF et al., 2009; Conway et al., 2014). CFF also supports quality improvement activities to improve medical and care process at CF centers (Godfrey and Oliver, 2014; Grosse et al., 2009). A comprehensive network of care that can surveil health outcomes, develop best practices, and monitor the quality of care for SCD does not exist.

Strategies recommended in the IOM report Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Healthcare Workforce (IOM, 2008) to increase health workers for the geriatric population may be applicable to SCD. These strategies include the following:

- Congress should allocate money in the budget to monitor the workforce.

- Hospitals should encourage resident training across all settings.

- All licensure, renewal, and maintenance of certification activities should measure competence in areas relevant to the topic.

- States and the federal government should increase minimum training standards in this topic.

- Public and private payers should include financial incentives to increase the number of topic specialists in all professions.

- Payers should promote and reward models of care shown to be effective.

- Federal agencies should promote advances in technology to increase the efficiency and safety of caregiving.

- Public, private, and community organizations should provide funding and ensure that adequate training opportunities are available in the community for informal caregivers.

Table 6-1 presents the essential care team members (core team) required to provide high-quality care for individuals with SCD, the specific roles for care team members, the level of training/experience necessary, and potential barriers to an available and well-prepared workforce. The committee employed a variety of methods in determining team members. First, the committee identified specialists and clinical services historically involved in SCD care. Next, the committee identified providers and specialists essential for addressing the routine, acute, and subacute care needs of individuals

| SCD Team Member or Service | Guideline for Provider Training | Team Member Role | Workforce Barrier | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Level Core Team Members | Hematologist/physician with expertise in SCD | Expertise in the evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Provide core treatment for individuals with SCD; coordinate overall management and liaise with other specialties. | There is a workforce shortage because older hematologists are retiring and fewer new physicians are entering the field. |

| Emergency medicine | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Recognize the acute manifestations of SCD, provide early pain management and resuscitation, and quickly determine patient disposition. | Negative provider attitudes toward individuals with SCD are a barrier to the delivery of guideline-adherent pain care. | |

| PCP | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Recognize manifestations of SCD and implement clinical advances in treatment in clinical practice; assist with patient education, medication/transfusion monitoring, and disease complication screening follow-up. | There are not enough PCPs with the comprehensive knowledge and expertise to care for individuals with SCD. There is a reluctance to devote time and effort to support a rarely seen population. |

|

| Nurse practitioner/physician assistants | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assist with patient education, medication/transfusion monitoring, and disease complication screening follow-up. | There is no formal training with the SCD population. | |

| Nurse care coordinator and nurses with SCD expertise | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Conduct initial assessment in clinics, assist with appointment scheduling, address patient-specific insurance issues, administer infusions in cooperation with the pharmacist, and perform exchange blood transfusions. | There is no formal training with the SCD population (negative provider biases and attitudes can influence care). Nurse care coordinators are only available at larger institutions. |

| Blood bank and transfusion medicine services | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Provide testing for extended RBC antigens and RBC alloimmunization. Exchange transfusion services. |

Individuals with SCD commonly become alloimmunized to RBC antigens—a contributing factor is that the donor base is predominantly Caucasian. | |

| Psychologist/psychiatrist | Comfortable discussing evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Provide psychological support for mental issues, such as depression, anxiety, pain management, grief counseling, transition to adult care, and pharmacological treatment. | Knowledge gaps about SCD and negative provider attitudes contribute to poor communication. | |

| Neuropsychologist | Comfortable discussing evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assess for cognitive challenges, as individuals with SCD are at high risk of neuropsychological problems (i.e., cognitive, emotional, social, or behavioral). | Social, cultural, linguistic/communication, and financial issues interfere with making and keeping appointments for traditionally scheduled neuropsychological evaluations. | |

| Social worker | Comfortable discussing evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assess the specific needs to ensure that services are provided to meet the identified needs; address social determinants of health and barriers to care. | Available options for social services are often inadequate for the specific needs of individuals with SCD. |

continued

TABLE 6-1 Continued

| SCD Team Member or Service | Guideline for Provider Training | Team Member Role | Workforce Barrier | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Level Core Team Members | Pulmonologist | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assess and provide treatment recommendations for pulmonary complications, which include ACS, asthma, lower airway obstruction, and airway hyper-responsiveness/bronchodilator response. | There is limited formal training with the SCD population. |

| Neurologist | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assess and provide treatment recommendations for neurologic complications, which include stroke, silent cerebral infarct, moyamoya syndrome, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, cerebral fat embolism, and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. | There is limited formal training with the SCD population. | |

| Dentist/dental hygienist | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assess and provide treatment for dental complications, which include caries or cavities, tooth hypomineralization, orofacial pain, neuropathy, facial swelling, pallor of oral mucosa, malocclusions, infections, pulpal necrosis, cortical erosions, medullary hyperplasia, and abnormal trabecular spacing. | There is limited formal training with the SCD population. | |

| Ophthalmologist | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Screen and provide treatment recommendations on vision complications. Every part of the eye can be affected by microvascular occlusions in SCD. The major cause of vision loss is proliferative sickle cell retinopathy. Screening before age 10 is recommended. | There is limited formal training with the SCD population and a lack of evidence regarding the optimal management of sickle retinopathy. |

| Nephrologist | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assess and provide treatment for renal manifestations, which include hyperfiltration, hypertrophy, impaired urinary concentration, microalbuminuria, macroalbuminuria, hematuria, acute and chronic kidney injury, and end-stage renal disease. | SCD presents unique challenges in the marked heterogeneity of renal involvement. Current therapeutic approaches are largely adopted from other kidney diseases. | |

| Obstetrician/gynecologist | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Perform SCD screening and adult patient care through prenatal screening, folic acid supplementation, and pregnancy management. | Many OB/GYNs who care for individuals with SCD are not consistent with the College Practice Guidelines on the screening of certain target groups and folic acid supplementation. | |

| Pharmacist | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Provide pharmacologic management of SCD pain, which may involve the use of non-opioid medications, opioids, and adjuvants; HU monitoring; patient education and health maintenance counseling. | The focus of training is oncology rather than benign hematology. | |

| Genetic counselor | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Provide premarital and prenatal counseling and testing. | This role requires additional sensitivity when working with a majority black population. | |

| Transition coordinator | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Evaluate patients for transfer readiness; prepare for transition and undertake an ongoing discussion about the transition process when patients reach their early teens; coordinate transfer to adult providers. | This will often be a part-time position shared with nursing or social work and only available at larger institutions. | |

| Community health worker | Basic knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assist with medication adherence, transitions of care, patient education, and education/vocation assistance. | There are no national standards for training, which is designed by the organizations that employ CHWs. |

continued

TABLE 6-1 Continued

| SCD Team Member or Service | Guideline for Provider Training | Team Member Role | Workforce Barrier | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancillary Team Members | Patient and family advisory group(s) | Basic knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Identify and drive projects important to individuals with SCD. Engage in decisions that affect quality of care. Promote patient- and family-centered care. Advise and advocate for children and their families. | This is only available at larger institutions. |

| Data quality analyst | Knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Develop and implement databases, identify trends, and interpret data from SCD clinical research. | There is no formal training with the SCD population. This position is only available at larger institutions conducting clinical research. | |

| Palliative care/integrative medicine | Basic knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Provide therapies, including non-pharmacological approaches to improve QOL. Integrative medicine may also include herbal remedies, diet and exercise interventions, acupuncture, acupressure, and aromatherapy. | Palliative care model has limited use with SCD population. There is no formal training with the SCD population. This position is only available at larger institutions. | |

| Physical therapist | Basic knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Provide therapies to reduce stress and pain and improve range of motion, which can include aerobic and breathing exercises, massages, or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation to disrupt pain sensors and relax muscles. | There is no formal training with the SCD population. |

| Education/vocational rehabilitation services | Basic knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assist with obtaining special education services for youth (school intervention); provide counseling and assistance related to educational attainment, vocational counseling, job training opportunities, and academic and employment accommodations. | There is no formal training with the SCD population. This position is only available at larger institutions. | |

| Financial advisor/counselor | Basic knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Assist with completing insurance applications and paying medical bills. | There is no formal training with the SCD population. This position is only available at larger institutions. | |

| Pastoral care | Basic knowledge of evidence-based management of individuals with SCD | Provide emotional and spiritual support; explore spiritual questions and concerns. | There is no formal training with the SCD population. This position is only available at larger institutions. |

NOTE: ACS = acute chest syndrome; CHW = community health worker; HU = hydroxyurea; OB/GYNs = obstetricians and gynecologists; PCP = primary care provider; QOL = quality of life; RBC = red blood cell; SCD = sickle cell disease.

SOURCES: Informed by Agrawal et al., 2019; CFF, n.d.; Farooq and Testai, 2019; McIntosh, 2016; Mulimani et al., 2016; Okpala et al., 2002; Scott, 2016; Simon et al., 2016; Wilkie et al., 2010; and National Academies SCD committee judgment.

with SCD, as discussed in Chapter 4. Finally, the committee considered multidisciplinary care team models from other chronic, inheritable diseases, such as CF (CFF, n.d.).

The SCD care team members are classified as core or supplementary based on their level of involvement in managing the clinical and psychosocial complications of SCD (see Chapter 4) or in decreasing disparities in care (e.g., CHWs). The committee also considered disciplines currently providing care that are perceived as beneficial by clinicians or patients (e.g., financial counselors). Some members of the core team, such as hematologists and ED physicians, currently treat children and adults with SCD in the United States. However, the committee determined that PCPs, nurses, and other advanced practice practitioners, with the right level of preparation, could manage the care of patients with SCD as needed. Second-level core team members assist with managing SCD complications but are designated as level 2 because they may not serve the entire SCD population and instead focus on individuals with a specific complication or need (e.g., a pulmonologist may work with patients with pulmonary hypertension, but not all patients with SCD will have pulmonary complications). Ancillary team members may provide services on an ad hoc basis or may provide enabling services but influence the way that care is delivered or managed by addressing key social contributors (determinants) of health.

TRAINING THE NEXT GENERATION OF SCD CARE PROVIDERS

There have been some efforts by national organizations and health care systems to recruit and retain the SCD workforce of the future. For example, ASH offers a training series for hematologists and internists to guide them in starting an adult SCD clinic. However, additional programming and resources are needed to foster the development of a well-trained multidisciplinary SCD workforce. In addition, a lack of diversity among health care providers may contribute to disparities in health care service. Having providers who are similar to the patients in important dimensions, such as race, ethnicity, and language, promotes effective communication and can improve patient–provider relationships. Diversity among faculty, staff, and trainees enhances creative problem solving and fosters robust decision making, innovation, and productivity both in the health care setting and the workplace in general (Alsan et al., 2018; Cohen et al., 2002; Forbes Insights, 2011; Hunt et al., 2015). Thus, to identify the best and brightest, national organizations and the health care system should implement specific recruitment and retention strategies that address identified gaps in training and professional development; this is essential for achieving and maintaining high-quality care. The next section summarizes current efforts

in workforce development and identifies gaps and opportunities for training in hematology, emergency medicine, primary care, and non-hematologic disciplines.

Hematology11

The growing need for greater clinical and research training in benign hematology has long been recognized. The number of physicians entering the field is decreasing, and many are not engaged in research (Hoots et al., 2015; Soffer and Hoots, 2018). Minorities are also under-represented in hematology/medical oncology, with only about 6 percent of individuals identifying as black/African American and about 8 percent as Hispanic (Santhosh and Babik, 2020). Further exacerbating the problem, hematology/medical oncology trainees receive little early clinical exposure to nonmalignant hematology (Marshall et al., 2018).

Curriculums in combined programs of hematology/medical oncology have been hypothesized to contribute to a shortage of researchers in benign hematology (Naik et al., 2018a). Of the 134 fellowship programs in the United States, 132 are combined double-board programs for hematology/medical oncology; only two institutions currently offer hematology-only programs (Naik et al., 2018a). Further reducing opportunities for training, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education no longer mandates the number of months required for nonmalignant hematology instruction in fellowships. Traditionally, one-third of a fellow’s time used to be spent in nonmalignant hematology training (Wallace et al., 2015). These difficulties are mirrored outside of the United States. For example, in UK medical schools, rotations are offered in cardiology, surgery, and psychiatry, but there is no dedicated rotation in hematology. Instead, exposure to hematology is largely tested as part of a syllabus focused on pathology (Mandan et al., 2016).

Intellectual curiosity and stimulation are significant determining factors for medical students and internal medicine residents when choosing a focus (Marshall et al., 2018). Hematology covers a wide breadth of topics that relate to both malignant and nonmalignant diseases, which makes hematologists important in advancing the research and treatment of many diseases. Third-year fellows have described benign hematology as more “complicated” and “overwhelming” than malignant hematology or medical oncology (Bernstein et al., 2017). Currently, there is little early clinical exposure to benign hematology that highlights its intellectual excitement (Marshall et al., 2018). Less than 6 percent of graduates plan to practice primarily in nonmalignant hematology (Todd et al., 2004). Importantly,

___________________

11 See Appendix J for additional training models for hematologists.

even at programs where exposure to benign hematology is mandatory, such as the University of Pennsylvania, only around one out of seven or eight fellows is training in benign hematology (Loren, 2009).

Additionally, there are generally fewer available mentors than in other specialties. A lack of or ineffective mentorship has been observed for potential hematology fellows, which can contribute to difficulty in hiring and retaining junior faculty, disillusionment with academia, and reduced grant funding (Straus et al., 2013). Fellows in hematology/oncology training programs have reported that mentorship opportunities tend to happen “randomly,” rather than individuals being able to actively seek out a relationship. Additionally, there are generally more available mentors in oncology, which can play a decisive role in the career decision process (Wallace et al., 2016). Without effective mentorship, it is difficult to generate excitement and inspire the same enthusiasm, and there are fewer networking opportunities to develop other productive relationships (Sambunjak et al., 2010).