7

Framework for Improving Birth Outcomes Across Birth Settings

The conceptual model presented in Chapter 1 (refer to Figure 1-7) identifies key areas for improving the knowledge base around birth settings and levers for improving policy and practice across settings. This model recognizes that three elements—access to care, quality of care, and informed choice and risk assessment among care options—contribute to the ultimate goal of positive outcomes in maternity care, and that the maternity care team, the systems and settings in which those personnel care for pregnant people and newborns, and collaboration and integration among providers and systems influence the presence and expression of those elements. It also shows that structural inequities and biases; social determinants of health; and the structure, policies, and financing of the health system itself influence quality, access, choice, and risk across birth settings. Each level of the model presents an opportunity to affect outcomes.

The system-level factors that influence outcomes across settings are responsive to intervention, yet these interventions are largely outside the scope of the health care system. Housing instability, transportation challenges, and intimate partner violence (i.e., social determinants of health) fall into this category. While Chapter 4 reviews these factors in detail and highlights some promising approaches to intervening in the context of maternal health care, given the committee’s charge, we focus in this chapter on factors that can be influenced within the health care system, through changes to either service delivery or the services themselves. Of course, we acknowledge and emphasize that while many disparities in outcomes accrue within the health care system, drivers of inequities in these outcomes begin outside the health care system. This reality undergirds our framework

for maternal and newborn care in the United States, described below, but there is a critical need for more research on how these factors affect birth outcomes (see, e.g., Krieger et al., 2014).

Given our charge to focus on health outcomes by birth setting, we focus our attention in this chapter on the question: How can each setting work to improve outcomes and make birth safer, where safety encompasses both clinical and psychosocial outcomes?

After first reviewing our framework for maternal and newborn care, we discuss opportunities for improving quality and outcomes in hospital births, the setting where the vast majority of pregnant people give birth in the United States. Next, we consider opportunities for improving quality and outcomes in home and birth center births, focusing on improving coordination, collaboration, integration, and regulation of these settings within the health care system. We then discuss efforts to improve informed choice and risk selection as well as access across settings. Finally, the chapter concludes with our assessment of priorities for future research. In each section, we highlight opportunities that prioritize respect for the woman and her infant and family, regardless of their circumstances (including race, ethnic origin or immigration status, gender identity, sexual orientation, family composition and marital status, religion, income, or education) or birth or health choices.

FRAMEWORK FOR MATERNAL AND NEWBORN CARE IN THE UNITED STATES

Culture of Health Equity

As described in Chapter 1, maternal and newborn care is embedded within the broader social context in which a person lives. As stated in Chapter 4 (Conclusion 4-1), system-level factors and social determinants of health such as structural racism, lack of financial resources, availability of transportation, housing instability, lack of social support, stress, limited availability of healthy and nutritious foods, lower level of education, and lack of access to health care (including mental health care) are correlated with higher risk for poor pregnancy outcomes and inequity in care and outcomes. That is, wherever a woman gives birth, the effects of the longitudinal, multifaceted, socially shaped health inputs she brings to her pregnancy and continuing through and beyond maternal and pediatric care influence her birth outcomes. These system-level factors, however, are modifiable, and improving maternal and newborn care in the United States will require interventions outside of the health care system.

Part of addressing these system-level factors is establishing a culture of health that ensures equitable access to quality care for all. As discussed in Chapter 4, a foundational driver of poor outcomes in maternity care is

racism and biased attitudes toward women. The experiences of women of color, especially Black and Native American women, and those of women generally, create risk factors that bear on pregnancy and childbirth. These experiences include intergenerational trauma; marginalization, intolerance, and hostility; and continuing economic disadvantage.

A culture of health delivers on economic, social, environmental, restorative, and birthing justice. Such a culture ensures, for example, that families have clean air and water; fresh, healthy food; safe neighborhoods; freedom from violence; paid family and medical leave and paid sick days; respectful treatment; and other essential social supports. In a culture of health, pregnant people and their partners are able to bring their good health to bear on determining whether and when to have children and, when pregnant, on actively engaging in a high-quality maternity care system that leads to robust pregnancy outcomes and the lifelong health of their children, ultimately contributing to the health of the next generation (Koblinsky et al., 2016; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019).

“Right Amount at the Right Time”

As described in Chapter 6, “too little, too late (TLTL)” and “too much, too soon (TMTS)” patterns in the provision of maternity care contribute to excesses of morbidity and mortality, and in the context of inequality, these extremes often coexist within a single health care system. This means that in the United States, home, birth center, and hospital birth settings each offer risks and benefits to the childbearing woman and the newborn. While no setting is risk free, these risks may be modifiable within each setting and across settings (Conclusion 6-1). We assert that a goal for the nation is to move beyond both TLTL and TMTS to the “right amount at the right time.” Moreover, this care should be delivered “in the right way,” that is, in a way that respects the autonomy and dignity of all birthing people, given that, as reported in Chapter 6, Finding 6-4: Some women experience a gap between the care they expect and want and the care they receive. Women want safety, freedom of choice in birth setting and provider, choice among care practices, and respectful treatment. Individual expectations, the amount of support received from caregivers, the quality of the caregiver–patient relationship, and involvement in decision making appear to be the greatest influences on women’s satisfaction with the experience of childbirth. The committee sees potential for providers with experience across settings to collaborate on strategies for reducing intervention-related morbidity and to find a more beneficial balance between TMTS and TLTL.

Therefore, the committee envisions a transformed maternal and newborn care system that places women and their infants at the center. In such a system, policies and structures are based on the best interests of these service

users. Available care is matched to the physical, emotional, and social goals, preferences, needs, and life circumstances of the woman and her fetus/infant. The woman and infant are matched to appropriate care, including type and intensity of services, with vigilance being exercised to determine whether a change in status calls for a different level of care, which might be of either greater or lesser intensity. Rigorous attention to the best available evidence limits overuse of unneeded care and underuse of beneficial care.

Respectful Treatment

In order to facilitate equitable access to maternity care services, the maternity care system must provide respectful treatment to all women in its care. The objective of respectful maternity care is to support pregnant and birthing women and remove barriers to receiving health care services before, during, and after birth. Across cultures and contexts, the components of respectful care are largely consistent. In a review of 67 qualitative studies on women’s and health care providers’ perspectives, Shakibazadeh and colleagues (2018) identify 12 components of respectful maternity care:

- being free from harm and mistreatment;

- maintaining privacy and confidentiality;

- preserving women’s dignity;

- sharing information and seeking informed consent;

- ensuring continuous access to family and community support;

- enhancing the quality of the physical labor and birth environment and resources;

- treating all women equally, regardless of age, race, ethnicity, religion, ability, or other subgroups;

- using effective communication, including the use of interpreters when needed;

- respecting women’s choices that strengthen their capabilities to give birth;

- having competent and motivated maternity care providers available;

- providing effective and efficient care; and

- ensuring continuity of care.

Based on our review of the literature and of public testimony before the committee, listening to women should be added to this list, as women may describe important symptoms not obvious to caregivers. Respectful maternity care is not a given for all women and pregnant individuals. Recent studies from the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia document women’s experiences of disrespect and mistreatment across lines of race/ethnicity (McLemore et al., 2018; Vedam et al., 2018),

ability (Hall, 2018), and nativity (Hennegan et al., 2014). Black and American Indian/Alaska Native women, immigrant women, and other women and individuals from marginalized groups face both structural racism and interpersonal bias within the health system, which likely contributes to disparities in pregnancy outcomes. To rectify these inequities, the maternity care system needs to strive to provide respectful care to all women by listening to them and responding appropriately, providing risk information in understandable terminology, providing culturally and linguistically appropriate care, providing informed choices around care and interventions, and providing clear and supportive communication for women who seek delivery care in hospitals before labor onset or too early in labor to admit.

HOSPITAL SETTINGS

Quality Improvement

The committee recognizes that many interventions are overused in U.S. hospital settings today. As discussed in Chapter 6, Finding 6-3: In the United States, low-risk women choosing home or birth center birth compared with women choosing hospital birth have lower rates of intervention, including cesarean birth, operative vaginal delivery, induction of labor, augmentation of labor, and episiotomy, and lower rates of intervention-related maternal morbidity, such as infection, postpartum hemorrhage, and genital tract tearing. These findings are consistent across studies. The fact that women choosing home and birth center births tend to select these settings because of their desire for fewer interventions contributes to these lower rates. There are promising strategies and approaches for lowering the rates of nonmedically indicated morbidity-related interventions, for example, the primary cesarean rate in hospital settings (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019a; Gams et al., 2019).

Such initiatives take a variety of forms and can be implemented at the regional or state level, in a particular health care system, or by an individual hospital or group of hospitals. Perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs)—“networks of perinatal care providers and public health professionals working to improve health outcomes for women and newborns through continuous quality improvement” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016, p. 6)—are a major mechanism for large-scale quality improvement. Within these networks, members from different stakeholder groups (health system administrators, physicians, midwives, state departments of health, childbearing women and their advocates, and others) work together to identify and address deficiencies in perinatal care processes as quickly as possible (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a). These state—and occasionally regional—networks contribute to important improvements

in health care and outcomes for childbearing women and infants, as well as cost savings for hospitals and systems (Horbar et al., 2017). The National Network for Perinatal Quality Collaboratives is a driving force for communication across PQCs and shared learning and teaching.

For example, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC), founded by the California Department of Public Health (Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Division) and the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative and headquartered at Stanford University, now includes more than 40 partner organizations and 200 participating hospitals. Since its inception in 2006, the CMQCC has developed a number of evidence-based quality improvement (QI) toolkits, which are combined with outreach efforts to help hospitals implement the initiatives. It uses data-driven approaches to understand the root causes of maternal mortality, including conducting mock emergencies, making quality improvements in hospital settings, and training staff to work more collaboratively. Its efforts have resulted in measurable improvements in maternal and infant outcomes:

- Among 56 participating hospitals, low-risk first-birth cesarean rates were reduced from 29.1 percent in 2015 to 24.6 percent in 2017, with no worsening of maternal and infant outcomes (Main et al., 2019).

- In contrast to the rise in maternal mortality in the United States as a whole, California’s maternal mortality rate was cut in half by 2013, down to 7.0 deaths per 100,000 live births (Main et al., 2018).

- Among 99 hospitals that used a collaborative mentorship approach to implement a hemorrhage safety bundle, severe maternal morbidity was reduced by 20.8 percent between 2014 and 2016 (Main et al., 2017).

- After the release of a toolkit designed to reduce elective early induction, along with an implementation playbook by the National Quality Forum, an additional 8 percent of California births were full term (California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, n.d.).

While these results are encouraging, ethnic group differences in improvements show that significant racial disparities persist (Main et al., 2018; McLemore, 2019). To address these persistent racial disparities, the CMQCC has initiated a new hospital-based racial equity pilot throughout several communities to redesign obstetric practices. Results from the pilot initiative are expected in 2020 (McLemore, 2019).

Other states have also seen striking results from PQCs. Participating hospitals in Ohio saw their nonmedically indicated early-term birth rate decrease by 68 percent between 2008 and 2015. Participating hospitals in New York experienced a 92 percent decrease in the proportion of early-

term scheduled births that were not medically indicated between 2012 and 2013 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014, 2016). In terms of maternal outcomes, PQCs have also contributed to reductions in primary cesarean births and maternal morbidity in some states. For example, the New York PQC saw a decrease of 91 percent in scheduled early-term primary cesarean births without medical indication among participating hospitals (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Additionally, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) supports QI through its infant mortality Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Networks (CoIINs). Through infant mortality CoIINs, multidisciplinary teams of local, state, and federal leaders work together to reduce infant mortality and related perinatal outcomes. These teams use real-time data to determine effective strategies and support distribution of best practices across states. Currently, there are four infant mortality CoIIN teams covering 25 states (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2018).

In an assessment of the CMQCC, Markow and Main (2019) attribute improvement through the QI initiatives to four key components: engagement of many disciplines and partner organizations, mobilization of low-burden data to create a rapid-cycle data center to support QI efforts, provision of up-to-date guidance for implementation using safety bundles and toolkits, and availability of coaching and peer learning to support implementation through multihospital quality collaboratives. While PQCs have shown promising results, currently they include primarily hospital settings in their initiatives. To promote improvement across settings and better outcomes for all women and infants, it is essential for all birth settings to participate in sentinel event reporting and root-cause analyses as part of PQC efforts.

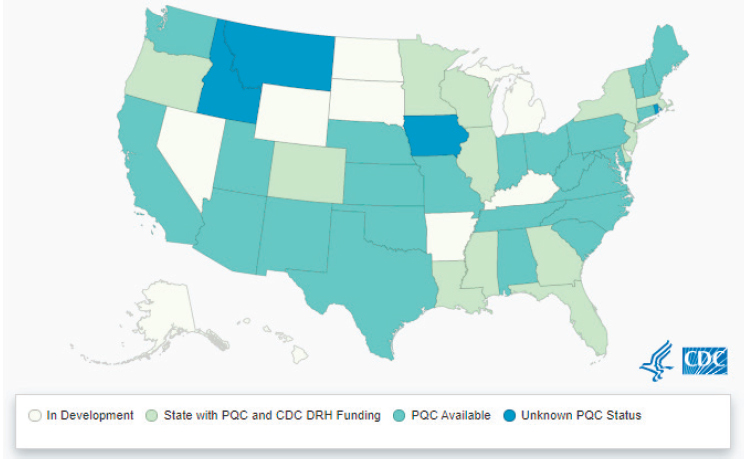

Moreover, 13 states either do not yet have a PQC or their status in this regard is unknown (see Figure 7-1). As noted above, while QI initiatives can lead to cost savings, many such initiatives are currently underfunded and receive no federal funding support. At present, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides support for state-based PQCs in Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Wisconsin. Sufficient and sustainable financing of QI initiatives by both government and private entities is needed if QI is to be implemented effectively at all levels of health care.

At the national level, the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) is another example of a QI initiative. AIM—a collaboration among numerous associations, including the American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and the American Hospital Association (AHA), funded through a cooperative agreement with HRSA’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau—produces patient safety bundles and provides implementation and data sup-

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019b).

port for states or health systems that wish to implement these care practices. There are currently eight AIM patient safety bundles, on issues that include opioid use disorder and reduction of racial/ethnic disparities. Preliminary evaluation of the initiative showed promising results, with reductions in the maternal morbidity rate in states that implemented the hemorrhage and hypertension bundles (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018b). Federal and state government support for and implementation of national data-driven maternal and newborn safety and QI initiatives such as AIM and the National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives would enhance the use of maternal safety and rescue protocols and best practices.

Specific national practice guidelines and adoption of those guidelines could also improve outcomes in hospital settings. For example, professional organizations such as the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetrics and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) (2018), ACNM (2015), ACOG (2019a), the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, 2014), and AIM (Lagrew et al., 2018) have published recommendations and clinical guidelines outlining the importance of supportive nursing care during labor and birth, such as nurse staffing. These guidelines are informed by research on the content of care and practice. For instance, researchers in several studies evaluated nursing care during labor as part of an overall approach to decreasing cesarean birth. One study showed that labor care

that included such nursing interventions as repositioning and use of a peanut ball was associated with lower cesarean birth rates when incorporated in a comprehensive program that implemented the ACOG-SMFM (2014) labor management guidelines proposed to prevent the first cesarean (Bell et al., 2017). Likewise, a unit culture in which nurses were encouraged to be at the bedside of women in labor as part of a program designed to reduce cesarean births and incorporating the ACOG-SMFM guidelines was found to be associated with lower cesarean birth rates (White VanGompel et al., 2019). The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative project (56 hospitals with more than 119,000 births) saw similar results in decreasing the cesarean birth rate among nulliparous term singleton vertex (NTSV) women by using the ACOG-SMFM guidelines regarding supportive nursing care, such as increased ambulation, upright positioning, peanut balls, and interpersonal coaching (Main et al., 2019). Finally, two randomized controlled trials of nursing care involving use of a peanut ball during labor had favorable results: Roth and colleagues (2016) found that nurses’ use of a peanut ball for nulliparous women shortened first-stage labor, while Tussey and colleagues (2015) found that this practice both shortened labor and deceased the risk of cesarean birth.

The quality of maternity care would also be improved if hospitals and hospital systems universally adopted national standards and guidelines promulgated by ACOG, SMFM, AWHONN, the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and ACNM for care in hospital settings—in particular, the ACOG-SMFM guidelines on levels of maternal care and the AAP guidelines on neonatal levels of care.

CONCLUSION 7-1: Quality improvement initiatives—such as the Alliance on Innovation in Maternal Health and the National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives—and adoption of national standards and guidelines—such as the Maternal Levels of Care of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Neonatal Levels of Care; and guidelines for care in hospital settings developed by the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses, the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology, and the American College of Nurse-Midwives—have been shown to improve outcomes for pregnant people and newborns in hospital settings.

QI initiatives may also lead to cost savings. For hospitals, such initiatives provide timely performance feedback (Henderson et al., 2018), training measures, and toolkits for quality improvement, all of which can lead to better individual outcomes and greater efficiency, as well as cost savings. For ex-

ample, hospitals that participated in neonatal infection prevention initiatives saved an estimated $2.2 million (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a). Similarly, in Ohio, participating hospitals saw an estimated savings of $28 million over 7 years by reducing the number of early-term births without a medical indication (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). States also see benefits when PQCs work to improve birth certificate data; for example, a 10 percent increase in the accuracy of birth certificates in Illinois resulted from a PQC-led QI initiative (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017b). However, QI initiatives can sometimes lead to financial losses for hospitals, depending on the revenue streams and mix of payers involved. For this reason, financial support from federal and state sources is critical to the successful implementation of such initiatives at all levels of health care. For example, in California, the state provides an incentive for hospitals to participate in the Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative. Hospitals that participate and provide a quality report to the state for ongoing evaluation and certification purposes receive extra reimbursement. This way, the hospital benefits, the Collaborative receives stable member funding to run its operations, and the state benefits from better care and lower cost.

Additionally, key to improving outcomes for pregnant women and infants in the United States is the ability to measure and report performance on meaningful aspects of care and priority outcomes. Box 7-1 addresses performance measures for quality improvement.

Access to Care Options

While some women desire vaginal birth, and births for high-risk pregnancies require well-equipped hospital settings (Bovbjerg et al., 2017), some women cannot find hospitals and physicians offering such care. This includes such maternity care services as planned vaginal birth after cesarean, external cephalic version, vaginal breech birth, and planned vaginal twin birth. Further, some women face challenges in finding hospitals that support intermittent auscultation, nonpharmacologic measures for labor comfort and progress, freedom to drink fluids and eat solids, freedom of movement in labor, and freedom of choice of birth positions, as well as the related essential care option of the choice between midwifery- or medical-led care (National Partnership for Women & Families, 2018).

Women’s ability to exercise choice with regard to birth setting is limited by this lack of access to care options. To promote safety, it is essential for informed choice of care that fosters physiologic childbearing to be readily available in all settings for women who desire such care. Moreover, access to such options is important for improving outcomes, as care that supports physiologic birth offers benefits for both childbearing women and their fetuses/newborns. These include onset of labor when the woman is ready to give birth and the fetus is ready to be born; comfort, progress, and safety in labor; healthy transitions of the woman and newborn after birth; and readiness and support for mother–infant attachment and establishment of breastfeeding (Buckley, 2015).

To promote better outcomes for pregnant woman and newborns, the majority of whom receive care in hospital settings in the United States, hospitals—individually and within geographic areas—have a clear and urgent responsibility to make available forms of care that appear to be safest in the hospital setting (e.g., planned vaginal breech birth), recognizing that comparative safety may change with greater integration within maternity care (Bovbjerg et al., 2017). Hospitals could meet this responsibility by developing in-hospital, low-risk, midwifery-led units; adopting these services in existing maternity units; and enabling greater collaboration among maternity care providers (including midwives, physicians, and nurses) at all levels of education and practice, as well as ensuring cultivation of these skills in obstetric residency and maternal–fetal medicine fellowship programs.

Evidence from the international literature also shows that alongside midwifery units (AMUs) (a midwifery unit located in or collocated with a hospital) have been successful in reducing the number of non–medically indicated interventions as compared with traditional obstetric units (Schroeder et al., 2017; Homer et al., 2014; Laws et al., 2014). The Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) model provides an illustra-

tive case study in the U.S. context. Certified nurse midwives manage care for both low- and moderate-risk patients, collaborating with physician colleagues to co-manage the care of women with high-risk pregnancies (e.g., gestational diabetes requiring medication, hypertensive disorders, chronic disease). Most recently, the obstetrical unit committed to the ACOG/ACNM Reducing Primary Cesareans Project initiative and has seen a decline in these rates (American College of Nurse-Midwives, 2017b). As part of that initiative, measures to support physiologic birth are routinely employed. These include use of birth and peanut balls, intermittent auscultation as the standard of care for all low-risk women, an in-house volunteer doula program, and use of hydrotherapy in labor. Mercy Hospital in St. Louis offers an additional example of a hospital setting providing access to midwifery care within the context of a minimal- to low-intervention model and a more conventional maternity care unit (see Box 7-2).

CONCLUSION 7-2: Providing currently underutilized nonsurgical maternity care services that some women have difficulty obtaining, including vaginal birth after cesarean, external cephalic version, planned vaginal breech, and planned vaginal twin birth, according to the best evidence available, can help hospitals and hospital systems ensure that all pregnant people receive care that is respectful, appropriate for their condition, timely, and responsive to individual choices. Developing in-hospital, low-risk, midwifery-led units or adopting these practices within existing maternity units, enabling greater collaboration among maternity care providers (including midwives, physicians, and nurses), and ensuring cultivation of skills in obstetric residency and maternal-fetal medicine fellowship programs can help support such care.

Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that socially and financially disadvantaged women may thrive in midwifery models of care across all birth settings. (Raisler and Kennedy, 2005; Huynh, 2014; Hill et al., 2018; Hardeman et al., 2019). The woman-centered philosophy of care that characterizes these models affirms agency among women of color, and group prenatal care models offer needed social support. Thus these models likely mitigate the harmful impact of medical models that have historically failed to trust the competence and capabilities of women, particularly Black women, including the experiences of disregard and disrespect described by many Black women in traditional care (Huynh, 2014; Vedam et al., 2019; Yoder and Hardy, 2018; Davis, 2018).

The available evidence is inadequate to determine health outcomes among women of color associated with hospital births that follow the midwifery model of care. Until more data are available to guide policy, there may be important opportunities to integrate midwifery models of care

and doulas (dedicated support persons for laboring women) for labor support into hospital-based delivery settings. Doing so would enable women of color, particularly those with elevated medical, social, or obstetric risk factors, to still garner the benefits of woman-centered midwifery models of care and labor support.

Incentivizing High-Value Care

High-value payment models with measures, performance targets, and value-based payment are a mechanism for accountability. In the current system, 23 percent of persons discharged from hospitals are childbearing women and newborns (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016), and giving birth and being born have together been the most costly hospital conditions for commercial insurance, Medicaid, and all payers (Wier and Andrews, 2011). While costs have risen through fee-for-service models, performance has routinely fallen short and is worsening for some indicators. Payment tied to value, rather than reimbursement for providing services whether or not optimal care occurred or an optimal outcome was achieved, can incentivize quality, create conditions for innovative systems and leaders to lead delivery system reform, improve care and outcomes, reduce costs, allocate resources to most effective services, and foster emulation and competition, among other improvements. While a number of high-value payment models exist, efforts are needed to pilot, evaluate, and refine these models more extensively and across state Medicaid agencies, Medicaid managed-care organizations, and commercial payers.

CONCLUSION 7-3: Efforts are needed to pilot and evaluate high-value payment models in maternity care and identify and develop effective strategies for value-based care.

Two high-value payment models in particular provide promising approaches for fostering care transformation, curbing overuse and underuse, encouraging members of the care team to work toward shared aims, and meeting the individualized needs of women and newborns: episode payment and the maternity care home (Avery et al., 2018). These models are described in detail below. They may be used in tandem and can include other important but less transformative payment reforms, such as increased payments for sustainability of maternity services in low-volume rural settings and blended case rates. See Box 7-3 for an example of implementation of a blended case rates model.

When implementing episode and maternity care home high-value care models, continuous evaluation, refinement, and learning from initial models and pioneer programs are important for accelerating care

transformation and achieving gains in quality, experience, outcomes, and resource use.

Maternity Care Episode Payment

Episode payment encourages collaboration of members of the care team across the three phases of care toward shared goals, and allocation of resources where they are likely to be most effective among a flexible array of services. The timing and types of services included in the episode and the price of the episode are defined. Quality measures are also defined to ensure that mechanisms to decrease costs within the episode foster and do not harm the quality of care. Appropriate adjustments are made for the level of risk involved.

A maternity episode payment program provides a single payment for all services across the episode and encourages members of the team to work together toward shared aims. When designed well, this model offers benefits:

The biggest beneficiary of bundled payments will be the patients, who will receive better care and have access to more choice. The best providers will also prosper. Many already recognize that bundled payments enable them to compete on value, transform care, and put the health care system on a sustainable path for the long run (Porter and Kaplan, 2016).

Innovative developers of episode payment models that drive toward high-value care will recognize that high-performing forms of care such as midwives, doulas, and birth centers are keys to success, including by reducing cesarean birth and increasing breastfeeding rates, improving performance on quality measures, minimizing overuse/waste and underuse/forgoing valuable care, and fostering women’s satisfaction. Proposals for episode payment of birth center care explore this potential (Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, 2018; Nijagal et al., 2018; Calvin, 2019).

While some bundling of services occurs in conventional codes for paying maternity care providers and in some hospital payments, these do not constitute an episode model. For example, the fee-for-service model involves separate billing from multiple entities (including maternity care provider, newborn provider, anesthesia services, facility maternal services, and facility newborn services), with payments not tied to quality and outcomes, as well as reliable periodic payment increases, providing little or no pressure for more judicious use of appropriate services.

Core elements of optimal, mature maternity care episode payment programs include the following (Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network, 2016, n.d.; Avery et al., 2018):

- inclusion of the woman and the baby;

- inclusion of the vast majority of women and newborns of varied levels of risk who benefit from greater accountability for quality and outcomes;

- limited exclusion of selected high-cost health conditions and further adjustments to limit service provider risk (e.g., risk adjustment, stop loss);

- duration from the initial entry into prenatal care through the postpartum and newborn periods;

- single payment for all services across the episode;

- a willing person who assumes role of coordinator;

- meaningful performance indicators that impact a large segment of the population (e.g., the nationally endorsed Cesarean Birth, Unexpected Complications of the Term Newborn, Exclusive Breast Milk Feeding, and Contraceptive Care-Postpartum measures, as well as woman-reported measures of the experience of maternal and newborn care and the outcomes of maternal care), and targets

-

for each measure that progressively raise the bar over time as systems develop ways to improve;

- performance impact on the revenue of all service providers, which begins with “upside” gainsharing and with experience over time moves to include downside potential for risk/revenue reduction;

- inclusion of high-performing care elements such as midwives, doulas, and birth centers, including services that may lack conventional billing codes;

- integration into practice, e.g., to foster communication across the care team, monitor performance, and manage payments;

- meaningful engagement of women and families (e.g., in informed choice of care provider and birth setting, shared care planning, shared decision making, access to health records, and completion of woman-reported measures of experience and outcomes), adding great value; and

- QI initiatives to support continuous improvement and success with high levels of accountability.

Maternity Care Home

The second high-value payment model with potential for reducing costs is maternity care homes. Four of five dollars paid on behalf of the woman and newborn across the entire episode from pregnancy through the postpartum and newborn periods cover the relatively brief hospital phase of maternity care (Truven Health Analytics, 2013). In that context, prenatal and postpartum office visits are limited to about 15 minutes, and a dearth of resources is available to meet the individualized needs of women and families that arise during office visits. As this inability to provide meaningful help for women’s identified needs likely contributes to disparities that could readily be averted or reduced, the maternity care home, modeled on the primary care patient-centered medical home (PCMH), can make a major contribution. The PCMH model has been shown to help reduce disparities (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2019).

By linking with social and community services, maternity care homes address social determinants of health, for example, by helping with smoking cessation, maternal mood disorders, or intimate partner violence. Similarly, they help coordinate clinical care across the episode, such as by helping the woman make care plans that include shared decision-making processes—for example, carefully weighing birth options after prior cesarean or postpartum contraception options. The care setting could be a birth center, OB/GYN practice, community health center, or health plan. The key attribute would be

responsibility across the episode of care for meeting the individualized needs of the woman and newborn.

Core elements of optimal, mature maternity-care home programs include the following (Rakover, 2016; Avery et al., 2018; Hill et al., 2018; Milliman, 2019):

- payment mechanism, such as a fixed amount per member per month (PMPM);

- personnel (“care coordinators,” “care navigators”) who are tasked with and prepared, resourced, and accountable for helping meet the individualized needs of pregnant and postpartum women (e.g., nurses, community health workers, or social workers);

- performance indicators (e.g., relating to care coordination, engagement, activation, shared decision making, care planning, access to convenience services such as support during evenings and weekends and prescription refills) and performance targets for each indicator;

- program incentives, including health plan support for infrastructure development and a recognition program demonstrating that the entity has developed capacities and meets standards of a maternity care home;

- performance incentives, for example, a health plan bonus or increased PMPM associated with performance;

- dual focus both to connect women and families with community and social services as needed and to plan and coordinate clinical care across episode settings and providers;

- commitment to addressing individualized needs of any woman in the practice, versus risk screening and premature, often faulty, case management segmentation, with potentially undermining “high-risk” labels and exclusion of some who may need services;

- support for women during the prenatal and postpartum periods, extending to 12 months after birth, reflecting the growing awareness that women’s postpartum needs and vulnerabilities are considerable and extend beyond the traditional care trajectory of about 2 months after birth; and

- integration into practice, for example, to foster communication between care navigators and maternity care providers, develop knowledge of/relationships with community and online resources, acquire and develop care coordination tools (e.g., patient portal, decision aids), and keep records.

HOME AND BIRTH CENTER SETTINGS

In reviewing the literature on outcomes in home birth settings, the committee found that statistically significant increases in the relative risk of neonatal death in the home compared with the hospital setting have been reported in most U.S. studies of low-risk births using vital statistics data (see Finding 6-1 in Chapter 6). With regard to birth center settings, we similarly found that, as reported in Chapter 6, Finding 6-2: Vital statistics studies of low-risk births in freestanding birth centers show a slightly increased risk of poor neonatal outcomes, while studies conducted in the United States using models indicating intended setting of birth have demonstrated that low-risk births in birth centers and hospitals have similar to slightly elevated rates of neonatal and perinatal mortality. Studies of the comparative risk of neonatal morbidity between low-risk birth center and hospital births were mixed, with variation across studies by outcome and provider type. Conversely, low-risk pregnant women showed lower rates of interventions and reductions in intervention-related morbidities in home and birth center settings as compared with hospital births (see Finding 6-3).

Because of the committee’s consensus on a woman’s right to choose where and with whom she gives birth, because we recognize that no birth setting is risk-free, because the data are imperfect, and because births are in fact already occurring in homes, birth centers, and hospitals in the United States, we focus in this section on how to improve outcomes and make birth safer in home and birth center settings in the United States.

International studies suggest that home and birth center births may be as safe as hospital births for low-risk women and that neonatal risk can be substantially reduced when (1) they are part of an integrated, regulated system; (2) providers are well qualified and have the knowledge and training to manage first-line complications; (3) transfer is seamless across settings; and (4) appropriate risk assessment and risk selection occur across settings and throughout pregnancy. Such systems are currently not widespread in the United States (see Finding 6-5 in Chapter 6). Thus, we focus on improved collaboration, integration, licensure, and regulation of these settings within the health care system—each representing key levers for improving birth outcomes in home and birth center settings. An integrated and regulated maternity care system aims to promote communication, collaboration, and coordination among health services providers and across care settings, and includes shared care and ready access to safe and timely consultation, collaborative care agreements that ensure seamless transfer across settings, appropriate risk assessment and risk selection across settings and throughout the episode of care, and well-qualified maternity care providers with the knowledge and training to manage first-line complications. Importantly, systems integration appears

to influence safety and outcomes, as does patient selection and matching of risk to setting.

Integration and Collaboration

To support equitable, high-quality maternity care, effective structures that shape care settings, providers, and practices need to be in place (Berwick, 2002). In fact, as observed in Chapter 6, Finding 6-6: Lack of integration and coordination and unreliable collaboration across birth settings and maternity care providers are associated with poor birth outcomes for women and infants in the United States.

Integration creates a single, coordinated, high-functioning system and is an important driver of safety. Moreover, as discussed in Chapter 6, a recent U.S. study suggests that integration of midwifery professionals within a state’s maternal care system may be related to improved maternal and newborn health outcomes (Vedam et al., 2018). Greater midwifery integration was found to be associated with significantly higher rates of spontaneous vaginal birth, vaginal birth after cesarean, and breastfeeding and significantly lower rates of cesarean birth, preterm birth, low-birthweight infants, and neonatal mortality. In the United States, midwifery integration varies from very low in North Carolina to moderate in Washington State (Comeau et al., 2018; Vedam et al., 2018).

A highly integrated maternity and newborn care system also requires the existence of respectful, collaborative relationships across settings and types of providers. The development and maintenance of respectful, collaborative relationships among providers of birth center and home birth care and providers of care in hospitals would foster seamless transfer to hospital care when needed. However, in the current fragmented system, collaboration is often hampered by systems or policies, such as those whereby physicians are not allowed to create these relationships on their own, or legal liability coverage does not permit collaboration with other providers, such as midwives (Sakala et al., 2013a).1 An integrated system offers women planning home and birth center births the safety of ready access to safe and timely consultation, shared care, and transfer of care and seamless transport when additional risk-appropriate care is needed. Such a system recognizes that all maternity care providers need places to turn when circumstances exceed their scope of practice and areas of competence.

___________________

1 Collaboration among providers may be hampered by professional liability concerns. Currently, professional liability restrictions may prevent professionals from providing appropriate care and negatively impact women’s access to maternity care choices. Some policies, for instance, impose surcharges for care, such as vaginal birth after cesarean, obstetricians’ collaborative practice with midwives, and family physicians’ provision of maternity care (Benedetti et al., 2006; Hale, 2006).

CONCLUSION 7-4: Integrating home and birth center settings into a regulated maternity and newborn care system that provides shared care and access to safe and timely consultation; written plans for discussion, consultation, and referral that ensure seamless transfer across settings; appropriate risk assessment and risk selection across settings and throughout the episode of care; and well-qualified maternity care providers with the knowledge and training to manage first-line complications may improve maternal and neonatal outcomes in these settings.

Multidisciplinary guidelines for transport from home and birth center settings are an essential tool for fostering safe, responsible integration of maternity services. As discussed in Chapter 6, the manner in which transfers are conducted, including the level of collaboration between the hospital and the community midwife, impacts birth outcomes (Vedam et al., 2014a). Model consensus guidelines for such transfers were developed through a multidisciplinary process that emerged from the 2011 Home Birth Consensus Summit (see Chapter 6).

The collaborative care model at Cheshire Medical Center (CMC) within the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in New Hampshire is one example of a hospital system collaborating with home and birth center providers. In 2010, the Northern New England Perinatal Quality Improvement Network began work to improve communication and interprofessional collaboration between community midwives and the hospital system. Early products included a Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) report form to be used by the midwife calling in to the hospital, resources for hospital personnel about scope of practice, and transfer guidelines. CMC also adopted protocols for the ambulatory setting and for in-labor transfers related to unaffiliated providers. Out-of-hospital midwives coordinate with the obstetrics and gynecology practice at CMC if their clients need particular tests or consultations. In the case of intrapartum transfer, the relationship is already established, and the transfer is smooth. Midwives retain primary responsibility for their patients, and hospital obstetricians complement their care. Postpartum women are released back into the care of the out-of-hospital midwife unless further collaborative follow-up is needed. Providers can quickly share information and work together effectively when care plans need to change. Postpartum followup and communication have improved as a result of home birth and birth center midwives having access to their clients’ electronic health records (Cheshire Medical Center, 2019).

The U.S. Military Health System also offers cross-cutting lessons for implementing a coordinated and integrated maternal and newborn care system, as described in Box 7-4.

Licensure and Regulation

Currently, nine states do not license birth centers (American Association of Birth Centers, 2016d). Licensure of birth centers in all states and territories would support safety. Licensing statutes, generally written with great specificity, ensure that planned births in birth centers are limited, to the extent feasible, to healthy, low-risk women, and that midwives provide care that keeps their clients healthy and continually assess and identify problems early so they can be properly and rapidly addressed. The American Public Health Association (APHA) has adopted model guidelines for writing state regulations licensing birth centers.2 These regulations cover such topics as definitions, staffing, the facility, fire and building codes, and the services that can and cannot be provided. For example, no states allow cesarean births in birthing centers.

The American Association of Birth Centers (AABC) establishes national standards to enable quality measurement of services provided in freestanding birth centers (American Association of Birth Centers, 2017). Components of external quality evaluation of birth centers include federal and state regulation, licensure, and national accreditation. The standards also encompass a strong internal quality improvement program, as well as criteria for appropriate clinical risk status for birth center admission. The committee supports the accreditation of freestanding birth centers, which provides an additional layer of assurance for women and families. The AABC standards provide the basis for accreditation and the indicators used by the Commission for Accrediting Birth Centers (American Association of Birth Centers, 2017). The standards cover seven areas: philosophy and scope of service; planning, governance, and administration; human resources; facility, equipment, and supplies; the health record; research; and quality evaluation and improvement. Accreditation of a birth center indicates that a high standard of evidence-based and widely recognized benchmarks has been met for clinical care and safety (American Association of Birth Centers, 2016a). The AABC regularly reviews the standards

___________________

2 APHA recommends the following: increasing legislative funding support to strengthen the public health workforce infrastructure, including public health nurses, with a focus on prevention, health promotion, and population-focused practice; developing academic–practice partnerships to prepare public health nurses for changes in the public health delivery system; developing the capacity for public health nurses to function at their highest levels of education, competence, and licensure; developing opportunities for public health nurses to build their capacity for health system and health policy leadership; developing effective strategies to recruit and retain qualified public health nurses; and increasing funding to support a research agenda that measures the effectiveness of public health nurse–sensitive interventions with respect to population health outcomes. See https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/10/13/29/guidelines-for-licensing-and-regulating-birth-centers.

to ensure that they remain consistent with current evidence-based maternity care. No research has been conducted specifically on variation in outcomes for birth centers that follow these standards and those that do not (Illuzzi et al., 2015).

CONCLUSION 7-5: The availability of mechanisms for all freestanding birth centers to access licensure at the state level and requirements for obtaining and maintaining accreditation could improve access to and quality of care in these settings. Additional research is needed to understand variation in outcomes for birth centers that follow accreditation standards and those that do not.

As discussed in Chapter 4, Finding 4:3: Access to midwifery care is limited in some settings because some types of midwives are not licensed in some states and do not have admitting privileges in some medical facilities, but this varies across the country. The wide variation in regulation, certification, and licensing of maternity care professionals across the United States is an impediment to access across all birth settings. Much of the discussion related to the education, training, and licensure of maternity and newborn care providers in the United States has focused on the midwifery profession. The U.S. Midwifery Education, Regulation, and Association (U.S. MERA), a coalition of representatives from seven national midwifery associations, credentialing bodies, and accreditation agencies, was formed in 2013 with the goal of creating a more cohesive midwifery workforce in the United States.3 The global midwifery standards and competencies of the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) (adopted in 2011) were used to underpin the group’s recommendations. Organizations participated in U.S. MERA signed on to support legislative language that includes the following: “by 2020 any new states adding midwifery licensure use language stating that all new applicants for midwifery licensure in that state must have completed an educational program or pathway accredited by an organization recognized by the U.S. Department of Education or have obtained the Midwifery Bridge Certificate. All applicants for licensure must pass a national certification exam, as well as hold CPM, CNM, or CM [certified professional midwife, certified nurse midwife, or certified midwife] credentials” (U.S. Midwifery Education, Regulation, and Association Professional Regulation Committee, 2015b).

___________________

3 The U.S. MERA participating organizations include the Accreditation Commission for Midwifery Education, American Midwifery Certification Board, Midwifery Education Accreditation Council, Midwives Alliance of North America, National Association of Certified Professional Midwives, North American Registry of Midwives, and American College of Nurse-Midwives. The International Center for Traditional Childbearing (ICTC) became a member of the U.S. MERA coalition in 2016.

The committee supports the certification and licensure of midwives who complete midwifery education at an accredited organization recognized by the U.S. Department of Education and who pass a national certification exam. We also discussed the evidence around the efficacy of endorsing licensure for the approximately two-thirds of current certified professional midwives who were trained in apprenticeship and self-study programs that lack accreditation. Under the U.S. MERA model language, the bridge certificate program is a pathway for these certified professional midwives credentialed through nonaccredited apprenticeship programs to meet the higher educational and training standards specified by the ICM. Bridge certificate applicants must complete 50 continuing education units of accredited coursework within 5 years of application.4 The committee did not reach consensus on the evidence for licensing credentialed midwives who use the bridge pathway. We recognize that in 2016, ACOG issued a statement supporting the ICM educational standards as the minimum education and licensure requirement for all midwives practicing in the United States and endorsed the Midwifery Bridge Certificate.5 However, the committee calls on professional organizations, such as those participating in the U.S. MERA process, to continue to study the appropriate level of education and training needed to offer high-quality, safe care to all women and infants.

CONCLUSION 7-6: The inability of all certified nurse midwives, certified midwives, and certified professional midwives whose education meets International Confederation of Midwives Global Standards, who have completed an accredited midwifery education program, and who are nationally certified to access licensure and practice to the full extent of their scope and areas of competence in all jurisdictions in the United States is an impediment to access across all birth settings.

INFORMED CHOICE AND RISK SELECTION

As discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, informed choice requires a set of real options, accurate information about the risks and benefits of those options, appropriate and ongoing medical/obstetrical risk assessment, respect for women’s informed decisions, and recognition that those choices may change over the course of care. True choice occurs when

___________________

4 See https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/State-Legislative-Activities/2017CPMLicensureLawsEducationStandards.pdf.

5 See https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2016/ACOG-Statement-on-the-US-MERA-Bridge-Certificate and https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2016/ACOG-Statement-on-the-US-MERA-Bridge-Certificate?IsMobileSet=false.

- choice among care providers and birth settings is available;

- choice among care options is available across the episode of care in all birth settings, including safe low-tech alternatives to common practices;

- women have access to high-quality information provided at appropriate literacy levels in culturally and linguistically concordant ways about the experience of birth across the variety of settings and types of providers and possible benefits and harms of the various care options, ideally through shared decision making and quality up-to-date decision aids and with support from a care navigator as needed;

- women receive professional guidance about the suitability of those options given the woman’s specific risk level and circumstances;

- the care team genuinely supports women’s informed choice and recognizes that perceptions of risk may differ among women and between a woman and her care provider; and

- women and their care team recognize that circumstances may change, and women’s choices may change.

However, women’s knowledge of their options and ability to exercise choice with regard to birth setting is limited by systemic barriers to knowledge, including a lack of systematic, objective information on the various options provided in plain lay English or an appropriate language.

A key component of informed choice is risk assessment, which accounts for a woman’s unique physical, social, financial, and emotional needs. In light of this assessment, women are then informed about all choices that align with their unique risk profile and circumstances. To enable this process, high-quality, evidence-based online decision aids and risk assessment tools incorporating medical, obstetric, and social factors that influence outcomes and facilitating clinical risk assessment and a culturally appropriate assessment of the woman’s risk preferences and tolerance are needed. A key feature of such tools would be helping women make decisions related to risk, including settings, providers, and specific care practices, leading to an overall birth plan for use in concert with their providers and care navigators. These tools need to be widely available, and their availability needs to be publicized.

CONCLUSION 7-7: Ongoing risk assessment to ensure that a pregnant person is an appropriate candidate for home or birth center birth is integral to safety and optimal outcomes. Mechanisms for monitoring adherence to best-practice guidelines for risk assessment and associated birth outcomes by provider type and settings is needed to improve birth outcomes and inform policy.

CONCLUSION 7-8: To foster informed decision making in choice of birth settings, high-quality, evidence-based online decision aids and risk-assessment tools that incorporate medical, obstetrical, and social factors that influence birth outcomes are needed. Effective aids and tools incorporate clinical risk assessment, as well as a culturally appropriate assessment of risk preferences and tolerance, and enable pregnant people, in concert with their providers, to make decisions related to risk, settings, providers, and specific care practices.

The committee notes a special challenge with respect to a woman’s ability to exercise informed choice regarding care provider and birth setting. In important respects, these choices are best made before entry into maternity care, a time when such discussions could be awkward, could involve conflicts of interest, and could inhibit women from acting on their informed preferences if doing so involved leaving a provider with whom they had initiated care. Thus, it is ideal to provide high-quality sources of information about these options and access to decision aids when women are planning pregnancy or have just become pregnant and have not yet entered care. Further support for these decisions can be provided by independent care navigators. If a woman pursues care that is not appropriate for her situation, her prospective maternity care provider has the responsibility to facilitate a more suitable match, whether to a higher or lower level of care (see Chapter 3).

In addition, it is important for women with low-risk pregnancies who present for physician-led care to be counseled about options for midwife-led care in the home, freestanding birth center, or hospital. For women who desire home or birth center births, midwives working in those settings need to apply protocols in assessing their eligibility. These protocols need to be aligned with state statutes and developed in concert with midwives, physicians, and policy makers, and to include guidance on physician consultation and facilitation of transfer aligned with model guidelines.

ACCESS

Ability to Pay

As discussed in Chapter 4, Finding 4-4: Access to all types of birth settings and providers is limited because of the lack of universal coverage for all women, for all types of providers, and at levels that cover the cost of care. Currently, only a limited number of insurance providers offer coverage for care in home or birth center settings. Models for increasing access to birth settings for low-risk women that have been implemented at the state level include expanding Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial payer cover-

age to cover care provided in home and birth center settings within their accreditation and licensure guidelines and to cover care provided by certified nurse midwives, certified midwives, and certified professional midwives whose education meets ICM Global Standards, who have completed an accredited midwifery education program, and who are nationally certified.

As an example, the Oregon Health Plan, the state’s Medicaid program, covers home birth for low-risk women in a limited set of circumstances. Out-of-hospital birth is covered if women meet low-risk criteria based on appropriate risk assessment (both initially and throughout pregnancy, labor, and delivery), no exclusion criteria are present, and criteria for consultation and transfer are met. Only pregnancies that meet the Oregon Health Authority’s (OHA’s) criteria for low-risk pregnancy, which include criteria for maternal, fetal, and placental complications for the current and any previous pregnancies, can be covered, and OHA delineates which conditions are allowable for out-of-hospital birth (Oregon Health Authority, 2015). Some risk criteria, such as multiple gestation and placenta previa, must be ruled out by ultrasound, while others, such as gestational hypertension, require continuous assessment over the course of the pregnancy. Out-of-hospital providers must perform clinical and diagnostic assessment for each risk criterion. If a woman refuses a required risk assessment, she is ineligible for an out-of-hospital birth because her risk status cannot be ascertained. The presence of high-risk complications, such as breech presentation, previous preeclampsia or eclampsia, or preexisting hypertension, renders the woman ineligible for a covered out-of-hospital birth (Oregon Health Authority, 2015). In addition to the requirements for risk selection, the Oregon Health Plan delineates situations in which an out-of-hospital midwife is required to consult with a hospital-based maternity care provider (Oregon Health Authority, 2015). When caring for women with high-risk conditions, such as more than one previous preterm birth, consultation between out-of-hospital and hospital-based providers is required to meet coverage criteria. Finally, coverage of out-of-hospital births under the Oregon Health Plan requires out-of-hospital providers to initiate transfer to a hospital during the intrapartum or postpartum period under certain conditions (Oregon Health Authority, 2015). These conditions include maternal infection or fever, hemorrhage, laceration requiring hospital repair, and failure to progress, among others. In the case of out-of-hospital deliveries, certain neonatal complications, such as very low birthweight (weight less than 3 lb 4 oz at birth), low Apgar scores (less than 5 at 5 minutes, and less than 7 at 10 minutes), and unexpected significant or life-threatening congenital anomalies, require transfer to a hospital for the midwife’s pretransfer services to be covered by the Oregon Health Plan (Oregon Health Authority, 2015).

The committee discussed the efficacy of national, universal adoption of Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial payer reimbursement for home

birth. In addition to Oregon, Washington State outlines administrative certification/licensure guidelines for midwives and home births that designate scope of practice standards in that state. Based on those guidelines, payers then designate reimbursable services. As detailed above, Oregon and Washington, for instance, have such licensure requirements for midwives (certified professional midwives, certified nurse midwives, and certified midwives), and Medicaid reimburses providers only for the care they provide within the scope of their licensure.6 These state-based models that include extensive licensure and certification guidelines are consistent with best practices. Unlike these leading states, however, the majority of U.S. states lack widely available integrated health care systems or requirements for collaborative care, as well as high-quality monitoring systems. In addition to these concerns, the committee is aware that disproportionate rates of such risk factors as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, depression and other mental illness, substance use, and smoking are present among the Medicaid population. Therefore, the committee did not reach consensus as to whether national expansion of Medicaid and Medicare for home births would be efficacious or cost-effective, but rather points to the need for additional research, demonstration, and evaluation of these state-level models.

An additional model for increasing access to birth settings for low-risk women and improving outcomes is to cover care provided by community-based doulas. As discussed in Chapter 5, the support of labor doulas offers many benefits for childbearing women (Bohren et al., 2017, 2019). In addition, the extended model of doula support (beginning during pregnancy, supporting childbirth, and continuing into the postpartum period), although less rigorously studied, appears to have benefits beyond those provided by labor doulas, such as reduced preterm birth and low birthweight and increased breastfeeding (Gruber et al., 2013). Overall, providing financing to support women’s use of doulas has been shown to be associated with both better outcomes for women and infants and cost savings (Kozhimannil et al., 2016; Greiner et al., 2019). New York, Minnesota, and Oregon have extended coverage for the services of doulas through Medicaid. Evaluation of such efforts to determine the potential impact of these state-level models is needed, particularly with regard to effects on reduction of racial/ethnic disparities in access, quality, and outcomes of care (Meyerson, 2019).

The rise of community-based perinatal health worker groups, which may include or focus exclusively on doula services, also holds promise. Such groups provide respectful, culturally concordant care and may fill a void in the availability of affirming, supportive, salutogenic services within the health care system (Karbeah et al., 2019; Davis, 2018; National Partner

___________________

6 See http://www.gencourt.state.nh.us/rules/state_agencies/mid500.html for an example of licensure/certification regulations for midwives in New Hampshire.

ship for Women & Families, 2019a). Thus, they may serve as a major part of the solution to addressing disparities in access to maternity care, as well as a key to community development (Hardeman and Kozhimannil, 2016; Kozhimannil et al., 2016; Ireland et al., 2019; National Partnership for Women & Families, 2019a). These groups often include training components, and have various models for financial support and various degrees of financial sustainability. While initial evaluations of their services are favorable, further evaluations are needed.

When considering expansion of coverage for care, it is important that reimbursement levels be adequate to support quality and allow providers across settings to sustain the services they offer. Currently, payment to providers through Medicaid and Medicare does not always cover the full cost of care and prevents some providers from accepting more women with Medicaid coverage. To address this issue, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) could analyze levels of payment for maternity and newborn care across birth settings to ensure that payment is adequate to support access to maternity care options nationwide. Just as Congress relies on the payment expertise of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to determine the adequacy of payment, the Medicaid program needs similar analysis to ensure access to quality, affordable maternity care for Medicaid beneficiaries. This analysis would also ensure that guidelines for billing under the various fee schedules are appropriate to all types of maternity providers—a point of particular importance to enable providers to care for a high proportion of uninsured or Medicaid patients.

Moreover, as noted throughout this report, evidence demonstrates that the postpartum period is critical for the adjustment and development of the woman and her infant and continues to set the stage for their long-term health and well-being (see, e.g., National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019). It is a period of exceptional change and transition for families, and there is increasing awareness of their considerable needs at this time. For example, ACOG terms this period the “fourth trimester,” and calls for postpartum care that is continuous throughout the postpartum period rather than a single encounter, as well as coordination between a woman’s maternity care providers and the rest of her health care team (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018a). In addition, awareness is increasing of the extent of adverse pregnancy-related outcomes that occur throughout the first year after birth, including maternal mortality and many types of new-onset and often persistent morbidity (Declercq et al., 2013; Petersen et al., 2019). This awareness is leading to a reconceptualizing of postpartum care needs, including growing calls for extending pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage to 1 year postpartum (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019b).

CONCLUSION 7-9: Access to choice in birth settings is curtailed by a pregnant person’s ability to pay. Models for increasing access to birth settings for low-risk women that have been implemented at the state level include expanding Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial payer coverage to cover care provided at home and birth centers within their accreditation and licensure guidelines; cover care provided by certified nurse midwives, certified midwives, and certified professional midwives whose education meets International Confederation of Midwives Global Standards, who have completed an accredited midwifery education program, and who are nationally certified; and cover care provided by community-based doulas. Additional research, demonstration, and evaluation to determine the potential impact of these state-level models is needed to inform consideration of nationwide expansion, particularly with regard to effects on reduction of racial/ethnic disparities in access, quality, and outcomes of care.

CONCLUSION 7-10: Ensuring that levels of payment for maternity and newborn care across birth settings are adequate to support maternity care options across the nation is critical to improving access.

Underserved Rural and Urban Areas

While the above section focuses on improving access to maternity care services for women lacking access as a result of their socioeconomic status, additional efforts are needed to improve access to services for women in underserved geographic areas. As described in Chapter 4, Finding 4-2: Women living in rural communities and underserved urban areas have greater risks of poor outcomes, such as preterm birth and maternal and infant mortality, in part because of lack of access to maternity and prenatal care in their local areas. Rural and urban maternity care deserts present a challenge to improving maternal and newborn care in the United States, and research is needed to develop sustainable models for safe, effective, and adequately resourced maternity care in underserved areas to resolve disparities in outcomes by geographic location. One approach to making quality maternity care more widely accessible is to build on the concept of community mental health centers, rural health centers, and federally qualified health centers. These centers were established to fulfill a need for services that might not be offered absent some public subsidies. HRSA could establish demonstration model birth centers and hospital services in underserved rural and urban areas and evaluate their impact on birth outcomes and access to care. Such models could focus, for example, on ensuring access by improving health equity. Use of telemedicine may also be appropriate as part of these centers, particularly in rural areas. The Strong Start initiative’s findings with respect to

the results of midwife-led care for Medicaid beneficiaries in birth centers also suggest that such policies could make inroads in lowering rates of preterm birth, low birthweight, and cesarean birth and increasing rates of breastfeeding while reducing costs (see the discussion of Strong Start in Chapter 4). Any intervention effective in reducing preterm birth and low birthweight—two of the most costly and intractable areas of inequality in maternity care in the United States—is worth pursuing (Petrou, 2019; Petrou et al., 2019).

Improving access to underserved rural and urban areas will also require increasing the pipeline of maternal and newborn care providers in these areas. Beyond specific efforts to rightsize and match the distribution of the maternity care workforce described below, research could explore the potential for using a variety of providers, including community health workers, public health nurses, certified nurse midwives, certified professional midwives, and certified midwives. These providers could be used in underserved communities to increase access to maternal and newborn care, including prenatal and postpartum care, while maintaining seamless transfer of information and continuity of care during the intrapartum period. Commonsense Childbirth’s Easy Access Clinic provides a model for extending such care to underserved areas through use of midwives. The clinic provides prenatal services for low-income and racial minority women who are at risk for not receiving prenatal care. Prenatal care is provided by midwives, and women may then choose to give birth in a birth center or an affiliated hospital setting. Designed to address higher-than-average rates of preterm birth, the clinic has succeeded in reducing disparities in the rate of preterm birth and greatly reducing cesarean births in the women served (National Partnership for Women & Families, 2019a). The Family Health and Birth Center (FHBC) in Washington, DC, offers another example of this type of care (see Box 7-5). These models demonstrate the promise of wraparound support for women of color and other underserved communities.