1

Introduction

The U.S. maternity system is fraught with uneven access and quality, stark inequities, and exorbitant costs, particularly in comparison with other peer countries. At the same time, the United States has among the highest rates of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity of any high-resource country, particularly among Black and Native American women1 (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2019; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a; Petersen et al., 2019). There is also growing recognition of a mismatch between the collective expectations of the care and support women deserve and what they actually receive (Vedam et al., 2019).

Childbirth services play a critical role in the provision of American health care. Childbirth is the most common reason U.S. women are hospitalized, and one of every four persons discharged from U.S. hospitals is either a childbearing woman or a newborn (Sun et al., 2018). As a result, childbirth is the single largest category of hospital-based expenditures for public payers in the country, and among the highest investments by large employers in the well-being of their employees (Podulka et al., 2011).

___________________

1 For the purposes of this report, the committee uses the term “women” throughout to describe pregnant individuals. However, we recognize that people of various gender identities, including transgender, nonbinary, and cisgender individuals, give birth and receive maternity care. See Box 1-1 for a more detailed discussion. In addition, the committee recognizes that multiple terms may be used to describe different cultural and ethnic groups, and that “race” is a social construct. For the purposes of this report, we use Black, White, Native American, and Latino (women) throughout. Box 1-2 provides additional context for the committee’s use of terminology in reference to ethnicity, race, and racism.

Cumulatively, this spending accounts for 0.6 percent of the nation’s entire gross domestic product (Rosenthal, 2013), roughly one-half of which is paid for by state Medicaid programs (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019).

For most American women, childbirth is also the first memorable time they are hospitalized, an episode that can frame their future engagement with the broader health system. Particularly for otherwise young and healthy women, pregnancy often serves as an initial entry point to receiving sustained health services as an adult. It is also common for some women to newly acquire health insurance during the months leading up to the birth of a child (The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, 2014). As a result, pregnancy can unmask existing chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, which require ongoing management. It can also reveal high-risk behaviors such as excessive drug or alcohol use, and high-risk situations, such as no or poor housing, issues with food availability, exposure to racism, stress, and negative family dynamics that can be mitigated by behavioral interventions, social support, and community support.

Despite their vital role in U.S. health care and in the lives of individual women, it is clear that the systems supporting childbirth in the United States are in need of improvement, and several examples of promising approaches to that end have shown reductions in cesarean and preterm births (see, e.g., Schneider et al., 2017). This report focuses on opportunities for improvement in one crucial component of U.S. maternity care: the settings in which childbirth occurs. It is important to note that this report recognizes variation among and within birth settings. Broadly speaking, possible intended birth settings include hospitals, birth centers, and home. There is extensive variation among hospitals and in the management of labor and birth and related staffing within any given hospital. Birth centers can be adjacent to or even within hospitals or can be freestanding, with varied transfer and backup arrangements. And home births vary by type of birth attendant and transfer and backup options. These and many more variations in models of care and resources are explored in this report, along with available evidence on birth outcomes in each setting.

While the vast majority of U.S. women—nearly 98.4 percent (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019)—experience childbirth in hospital settings, a small (but growing) percentage give birth in birth centers or at home. Not all women are able to access these options should they desire them, and within hospitals, not all women are able to access models of care that minimize interventions and allow for social support and informed decision making. In this context, and given the issues of cost, access, and content that characterize current U.S. maternity care, two urgent questions for women, families, policy makers, and researchers arise: How can an evidence-informed maternity care system be designed that allows multiple

safe and supportive options for childbearing families? How can birth outcomes be improved across and within all birth settings?

PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THIS STUDY

In 2018, the Congressional Caucus on Maternity Care, led by Congresswoman Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA) and Congresswoman Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-WA), recognized the great need for policy solutions to better the health of mothers and children. The March 2018 omnibus appropriations bill included language calling on the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) to request that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine conduct the study that resulted in this report. In response, the National Academies convened an ad hoc committee of experts that was tasked with examining the evidence on health outcomes across birth settings, particularly with regard to subpopulations of women. (See Box 1-3 for the committee’s full statement of task.)

This study served as an update to two previous activities of the National Academies (see Box 1-4). In examining the research on birth settings, the committee was asked to analyze the current state of the science on six topics:

- What risk factors affect maternal mortality and morbidity overall? (See Chapters 3 and 4.)

- What factors affect the choice of and access to birth settings? (See Chapters 3 and 4.)

- What are the social determinants of health that influence risk and outcomes in varying birth settings? (See Chapter 4.)

- What are the financing models for childbirth across settings? (See Chapters 2 and 7.)

- What are the licensing, training, and accreditation issues pertaining to professionals providing maternity care across all settings? (See Chapters 2 and 7.)

- What lessons are learned from international experiences? (See Chapters 6 and 7.)

During its first meeting, the committee had the opportunity to discuss the objectives of the study with congressional staff and representatives from NICHD. In the course of these discussions, the sponsors made clear that they hoped the committee’s report would be used “to create policies to better the health of mothers and children” and “to find policy solutions to save lives.” They highlighted the need for a synthesis of evidence to inform decision making by members of congress and other policy makers, regulators and payers, practitioners, pregnant women, and the research community.

To carry out its task, the committee needed to define the continuum of care at the core of its scope of interest. While the committee’s charge (refer to Box 1-3) was to focus on the childbirth experience, we elected to focus on the period from conception through the first year postpartum. The effects of the longitudinal, multifaceted, socially determined health inputs a woman brings to her pregnancy influence outcomes for both mother and newborn. Moreover, prenatal care plays a pivotal role in birth outcomes, and these outcomes are reflected throughout the first postpartum year. Prenatal care settings and provider types also can influence maternal choice of birth setting, as, for example, when a woman chooses to give birth in the hospital where her prenatal care provider has admitting privileges or chooses in-home care with a midwife because she lives in a rural community and lacks reliable transportation. The committee understands that broader societal forces and the life circumstances of preceding generations affect birth outcomes, which in turn are modified far beyond the first year of life.2

The committee also recognizes that the model of prenatal and postpartum care varies by birth setting and within types of settings, that pre-

___________________

2 For further information on how critical neurobiological systems develop in the prenatal through early childhood periods and how social, economic, cultural, and environmental factors significantly affect a woman’s and child’s health ecosystem and ability to thrive, see National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019).

natal care plays a role in intrapartum care, and that both prenatal and postpartum care influence birth outcomes. For these reasons, we review the evidence on birth settings across the childbearing year, from preconception to the postpartum period, but dedicate the majority of our analysis to the intrapartum period.

The study’s charge also asked the committee to focus on “subpopulations of women.” In discussions with the sponsors, it became clear that “subpopulations of women” referred to groups of women experiencing higher pregnancy- and birth-related maternal morbidity and mortality. U.S. data indicate that these are Black and Native American women in particular, as well as women in underserved areas, such as certain rural and urban populations.

THE PROBLEM

Maternal and newborn care is critical to the nation’s health. Equitable access to such care and the best possible outcomes for all racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups are also essential. For women, maternal exposures during pregnancy can have profound long-term consequences for health later in life, such as risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension (Arabin and Baschat, 2017; Oliveira et al., 2014). As will be discussed in further detail in this report, U.S. levels of maternal mortality and morbidity exceed those of many other countries, even as more is spent on maternity care.3 To make matters worse, the morbidity and mortality outcomes are worse for Black and Native American women, and the trend is not encouraging.

For children, the appropriate care of newborns is crucial during a window of rapid growth and development at the beginning of life. The effects of exposures to factors that shape the health trajectories of newborns start before conception; thus, the preconception and prenatal periods are

___________________

3 This report uses the terms “maternal mortality” or “pregnancy-related deaths,” and “maternal morbidity” or “severe maternal morbidity.” The World Health Organization (WHO) defines maternal mortality as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes” (World Health Organization, 2019). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines pregnancy-related deaths as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 1 year of the end of a pregnancy—regardless of the outcome, duration, or site of the pregnancy—from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a). WHO defines maternal morbidity as “any health condition attributed to and/or aggravated by pregnancy and childbirth that has a negative impact on the woman’s wellbeing” (Firoz et al., 2013, p. 795). The CDC defines severe maternal morbidity as including “unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery that result in significant short- or long-term consequences to a woman’s health” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019b).

vital to setting the odds for lifelong health (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019). Growing scientific understanding of the early determinants of health (Hanson and Gluckman, 2014) in the fields of the microbiome (Mueller et al., 2015), epigenetics (Dahlen et al., 2013), life-course health development (Halfon et al., 2018), and the hormonal physiology of childbearing (Buckley, 2015) increasingly shows that exposures to such factors during sensitive periods of rapid fetal and neonatal development have the potential for long-term and even lifelong positive or negative effects on the health of the child.

Despite the importance of high-quality maternal and newborn care to the nation’s health, however, access to services essential to such care is a concern for many U.S. women. In 2016, more than 5 million women lived in counties (rural or urban) with neither an obstetrician/gynecologist nor a nurse midwife, nor a hospital with a maternity unit (March of Dimes, 2018a). Among the 42 percent of childbearing women who rely on Medicaid for maternity care coverage (Martin et al., 2019), many live in states that have not expanded eligibility for Medicaid, meaning that some women can gain Medicaid coverage only after becoming pregnant.4 These women then lose Medicaid coverage about 2 months after giving birth (Daw et al., 2017), despite growing recognition of the considerable postpartum health needs and vulnerabilities that persist through at least the first year following birth (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018a; Ranji et al., 2019). Of additional concern is the fact that some women are not eligible for Medicaid because they lack documentation that they are legal residents of the United States. This means that they do not have access to prenatal care and that postpartum care for the woman and infant will be extremely limited, but that hospital deliveries will be covered even though, paradoxically, such births may be complicated by the lack of prenatal care.

Regardless of the type of coverage, moreover, many childbearing women and newborns do not reliably receive quality care that is safe, evidence based, and appropriate for their health needs and preferences. Maternal and newborn care in the United States is characterized by broad variations in practice, with considerable overuse of nonmedically indicated care, underuse of beneficial care, and gaps between practice and evidence (Glantz, 2012; Miller et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2016; Fingar et al., 2018). For example, access to prenatal care varies greatly across racial/ethnic groups, and many U.S. women lack access to essential maternity care services. Prenatal care provides risk assessment and treatment of some conditions, monitoring of the health of mother and baby, and vital health

___________________

4 As of 2019, 33 states and the District of Columbia had adopted and implemented Medicaid expansion, and 14 states had not. Three states had adopted Medicaid expansion and hoped to have it implemented by 2020 (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019a).

information and education for the pregnant woman. In 2018, more than 77.5 percent of all women who gave birth initiated prenatal care in the first trimester. Yet this was the case for only 67.1 percent of Black, 72.7 percent of Hispanic, 62.6 of American Indian/Alaska Native, and 51.0 percent of Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander women, compared with 82.5 percent of non-Hispanic White women (Martin et al., 2019).

In addition to the problem of “too little” care is that of “too much” care. Healthy women and newborns are often subject to costly care practices that are better suited for those at higher risk or with complications, even though many of these practices can have harmful side effects (Avery et al., 2018; Kennedy et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2016). For example, the United States has one of the highest rates of caesarean birth among high-resource countries (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2019)—31.9 percent of all births (Hamilton et al., 2019). While there is no evidence-based number for the ideal cesarean birth rate, most experts agree that this rate is too high (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019a; World Health Organization, 2015).5 Cesarean births generally carry greater risks to the mother than do vaginal births, including a longer recovery time (Gregory et al., 2012), and data from several countries show lower rates of cesarean birth along with better outcomes for infants and pregnant women (Kennedy et al., 2019).

In addition to the problems of too little and too much care, the quality of care is uneven. Substandard care results in poor maternal and fetal outcomes that are largely preventable (Ozimek et al., 2015; Howell, 2018; Review to Action, 2018). Moreover, structural racism, implicit and explicit bias, and discrimination underlie large and persistent racial/ethnic disparities in the quality of care received by childbearing women and infants (Howell, 2018; McLemore, 2019; Sigurdson et al., 2018).

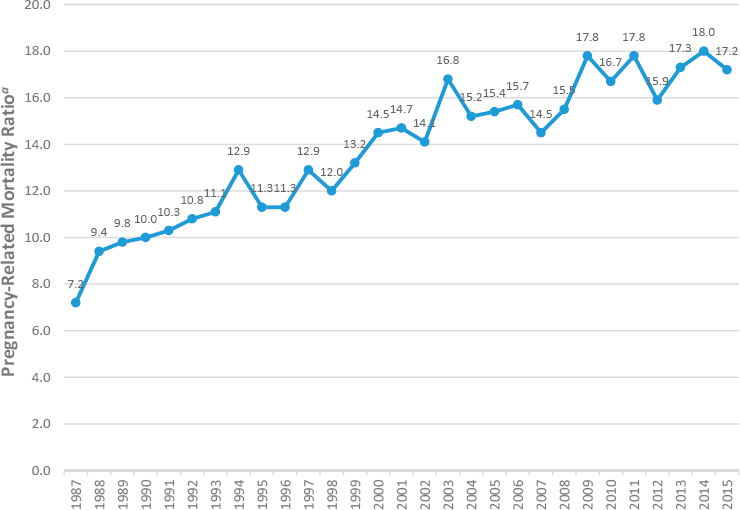

These issues of access and quality—driven by such system-level factors as racism and discrimination and unequal allocation of resources, among others (discussed below and in Chapter 4)—are reflected in trends in maternal and infant mortality and morbidity. Childbearing women and newborns in the United States have worse outcomes than their peers internationally. Unlike other high-resource countries, the United States has seen a rise in pregnancy-related mortality (see Figure 1-1). After decades of decline, the U.S. pregnancy-related mortality rate was recorded at about 7.2 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 1987. The rate then began to increase, and at its height in 2014, there were 18 pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

___________________

5 According to WHO, “the international healthcare community has considered the ideal rate for cesarean birth to be between 10 percent and 15 percent” (World Health Organization, 2015, p. 1).

aNumber of pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births per year.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019a).

2019a). In contrast, the rate of maternal mortality has consistently dropped in most high-resource countries over the past 25 years (Geller et al., 2018).

Severe maternal morbidity has been increasing in the United States as well (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a). It is estimated that for every woman who dies in childbirth, 70 more come close to dying (Montagne, 2018). All told, more than 50,000 U.S. women each year suffer severe maternal morbidity or “near miss” mortality, and roughly 700 die (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019b), leaving partners and families to raise children while coping with a devastating loss. Like the rates of maternal mortality, U.S. rates of severe maternal morbidity are high relative to those in other high-resource countries (Geller et al., 2018). In this context, it is notable that some local efforts in the United States have shown progress in reducing rates of maternal mortality and morbidity. In California, for example, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative led an initiative that reduced rates of maternal mortality by 55 percent (from 2006 and 2013) (Main et al., 2018; see also Chapter 7).

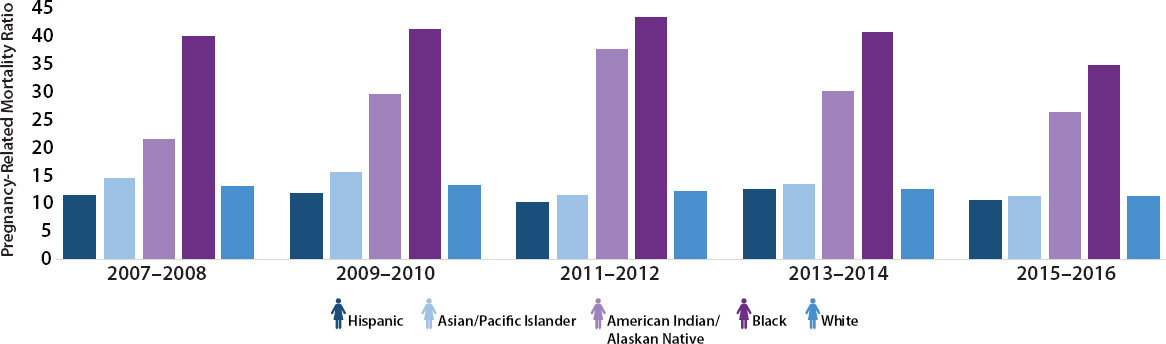

As will be discussed in detail in Chapters 3 and 4, maternal mortality and morbidity rates are not the same for all ethnic groups. Higher rates per-

sist and have even increased for Black and Native American women. Even such successes as the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative show ethnic group differences in improvements (Main et al., 2018). In 2005, the maternal mortality rate for White individuals was 11.8 per 100,000 live births, increasing to 19.0 per 100,000 in 2014, while the corresponding rates for non-Hispanic Black individuals were 39.2 and 48.7 per 100,000, respectively. Native American and Alaska Native individuals also saw large increases in maternal mortality rates from 2005 to 2014, from 11.1 per 100,000 to 37.8 per 100,000. Increases were seen for Hispanic women as well, increasing from 9.6 per 100,000 to 12.5 per 100,000 between 2005 and 2014 (McLemore, 2019). Figure 1-2 shows the U.S. maternal mortality rate over time, by race and ethnicity. Disparities are also present in maternal mortality rates by geographic location. According to the CDC, in 2015 the maternal mortality rate in large metropolitan areas was 18.2 per 100,000 live births, while in the most rural areas it was 29.4 per 100,000 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a).

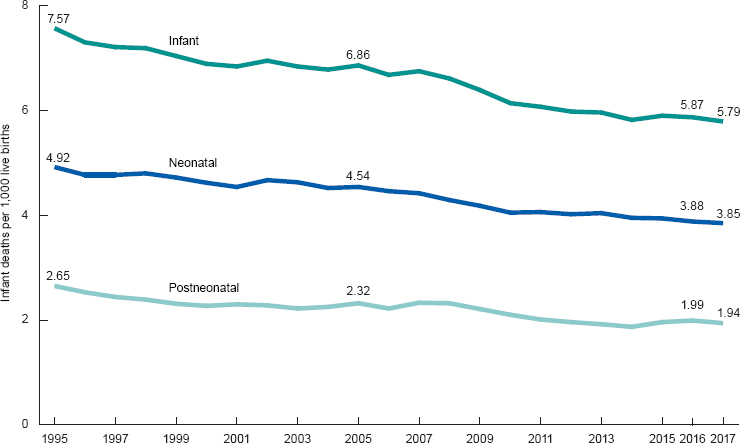

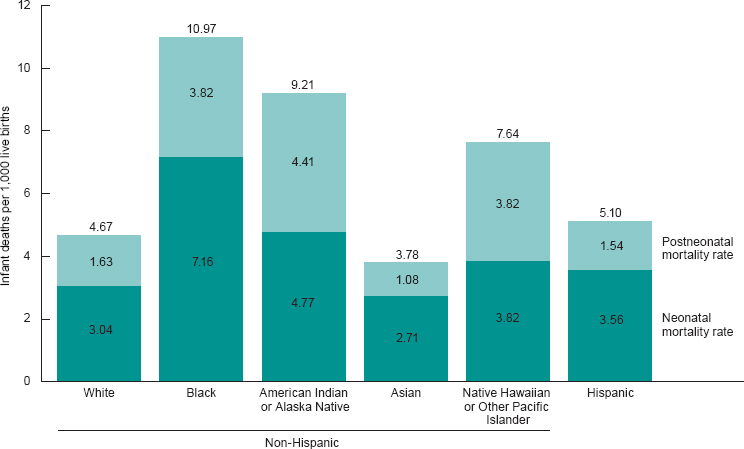

In contrast to maternal mortality, infant mortality in the United States has been declining over the past 20 years (see Figure 1-3), and there are expanded opportunities for survival at increasing levels of prematurity and illness complexity. However, large disparities persist among racial/ethnic groups and between rural and urban populations. In 2017, infant mortality rates per 1,000 live births by race and ethnicity were as follows: non-Hispanic Black, 10.97 per 1,000; American Indian/Alaska Native, 9.21 per 1,000; Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 7.64 per 1,000; Hispanic, 5.1 per 1,000; non-Hispanic White, 4.67 per 1,000; and Asian, 3.78 per 1,000 (Ely and Driscoll, 2019; see Figure 1-4).

Mirroring these disparities, in 2014 infant mortality in rural counties was 6.55 deaths per 1,000 births, 6 percent higher than in small and medium urban counties and 20 percent higher than in large urban counties (Ely et al., 2017). Neonatal mortality was 8 percent higher in both rural (4.11 per 1,000 births) and small and medium (4.12 per 1,000 births) urban counties than in large urban counties (Ely et al., 2017, p. 4). Mortality for infants of non-Hispanic White mothers in rural counties (5.95 per 1,000) was 41 percent higher than in large urban counties and 13 percent higher than in small and medium urban counties (Ely et al., 2017, p. 4). For infants of non-Hispanic Black mothers, mortality was 16 percent higher in rural counties (12.08) and 15 percent higher in small and medium urban counties than in large urban counties (Ely et al., 2017).

Rates of preterm birth and low birthweight have increased since 2014, and as with other outcomes, show large disparities by race and ethnicity (Ely and Driscoll, 2019; Hamilton et al., 2019). Low-birthweight (less than 5.5 pounds at birth) and preterm babies are more at risk for many short- and long-term health problems, such as infections, delayed motor and social

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019g).

SOURCE: Ely and Driscoll (2019).

NOTE: Neonatal and postneonatal rates may not add to total infant mortality rate due to rounding.

SOURCE: Ely and Driscoll (2019).

development, and learning disabilities (March of Dimes, 2018b). About one-third of infant deaths in the United States are related to preterm birth; in 2017, the rate of preterm-related infant death was 199.1 per 100,000 births (Ely and Driscoll, 2019). However, the rate of preterm-related infant mortality for non-Hispanic Black women (454.1) was more than three times the rate for non-Hispanic White women (135.1) (Ely and Driscoll, 2019). Rates of low birthweight by race/ethnicity in 2018 ranged from 6.91 percent for births to non-Hispanic White women to 14.07 percent for births to non-Hispanic Black women, with rates of 8.58 percent for Asian women, 8.0 percent for American Indian/Alaska Native women, and 7.40 percent for Hispanic women. Black infants are also more than twice as likely as other infants to have very low birthweight—less than 3 pounds, 5 ounces—at 2.92 percent in 2018 compared with 1.02 to 1.24 percent for White and Hispanic infants, respectively (Martin et al., 2019). Low birthweight is associated with such social and economic factors as low income, low parental education level, maternal stress, racism, and domestic violence or other abuse, as well as maternal smoking, use of alcohol, or low weight gain (Institute of Medicine, 2007).

While the United States lags behind other high-resource nations in terms of maternal and some newborn outcomes, moreover, it continues to outpace its peer countries in the costs of maternity care. Together, maternal and newborn care are the most expensive hospital conditions for Medicaid, private insurance, and all payers (Wier and Andrews, 2011). Just as the United States’ overall health care cost per capita and health care cost as a proportion of gross domestic product far exceed those of any other nation (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2018), maternity care costs also are generally higher than those of other countries (International Federation of Health Plans, 2015). According to the International Federation of Health Plans (2015), the average cost of services for a spontaneous vaginal birth in the private sector is approximately five times higher in the United States than in Spain. While this higher cost is due to a combination of factors, much of it is driven by considerable variation in cost for healthy low-risk births (Xu et al., 2015). Institutional factors—but not quality—are associated with higher costs for low-risk births (Xu et al., 2018). In short, the U.S. maternity care system currently incurs extraordinary costs to produce among the poorest outcomes among high-income nations, while simultaneously failing to effectively redress racially and ethnically driven inequities.

THE OPPORTUNITY

Given the current state of maternity care in the United States as reviewed above, further study of the birth settings chosen by or assigned

to women and the factors that go into those choices is warranted, and examining variation in the outcomes experienced in different types of settings is a priority. Moreover, unprecedented maternity-related developments (described in Box 1-5) have occurred in the 6-year period between the 2013 National Academies workshop and the work of this committee. This report builds upon ongoing efforts toward greater integration of the nation’s maternity care system across care teams and birth settings, major

steps toward responding to the maternal health crisis, the great potential for quality improvement in maternity care, and increased knowledge of and support for women’s and newborns’ experience of perinatal care with a maximum of informed choice based on careful risk assessment and a minimum of interventions unless and until needed. Other important trends include a heightened awareness of disparities, institutional racism, and rural and urban inequities in health outcomes/health resource distribution.

In addition, there is greater recognition of a preconceptual window for assessing women’s desire for pregnancy and their health status, including detecting diabetes and hypertension, as well as behavioral health issues such as use of opioids and other harmful substances. Current trends also focus on postnatal care for the first year, patient engagement, and patient-centered care.

Thus this report coincides with a period of significant efforts to improve the quality, experiences, outcomes, and costs of maternity care in the United States. It provides a path forward for continued improvements to ensure that all women and children have access to quality, affordable, safe, and supportive care across all birth settings.

STATISTICS AND TRENDS IN BIRTH SETTINGS

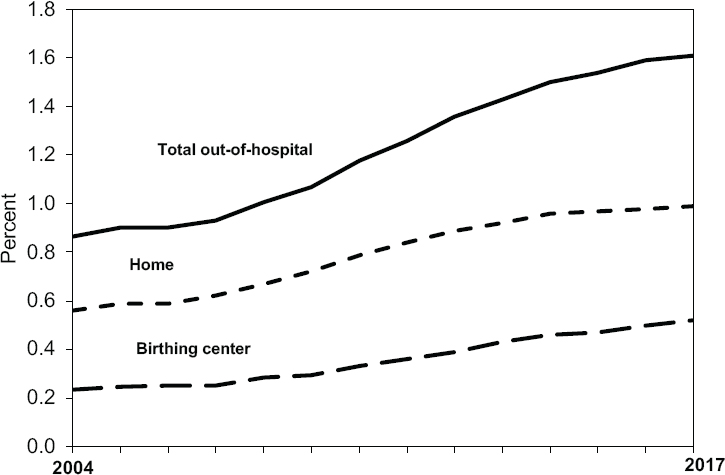

As noted earlier, the vast majority of women in the United States give birth in a hospital, but rates of home and birth center births are increasing, particularly in certain states and among certain populations (see Figure 1-5). At the turn of the 20th century, nearly all births occurred at home. By 1969, only 1 percent of births occurred outside a hospital; this rate remained steady throughout the 1970s and 1980s (Institute of Medicine, 2013). The rate of out-of-hospital births gradually declined during the 1990s and early 2000s, but then began to reverse course. Between 2004 and 2017, the percentage of out-of-hospital births increased 85 percent, from 0.87 percent of all births (35,578 births) to 1.61 percent (62,228 births) (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019); the rate of home births increased by 77 percent, rising to 0.99 percent of all births; and the rate of birth center births more than doubled, rising to 0.52 percent of all births (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019). About 85 percent of home births were planned, while 15 percent were unplanned (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019). Rates of out-of-hospital births vary considerably among states, with higher rates in the Pacific Northwest and lower rates in the South (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019).

The data in this section are from a 2019 study by MacDorman and Declerq, “Trends and State Variations in Out-of-Hospital Births,” for which national birth certificate data from 2004 to 2017, as well as national data on method of payment for delivery, were used. While these data are quite comprehensive, including information on the entire population of around 3.9 million births in the United States each year, there are limitations. These limitations include less than national coverage for some variables; for example, two states that account for 15 percent of births do not report on smoking rates. Further, California does not report whether a home birth was planned or unplanned, making it impossible to ascertain the planning status for 12 percent of births nationally. While the other 49 states and the District of Columbia do report planning status, there is no way to differ-

NOTE: Out-of-hospital births include those occurring in a home, birthing center, clinic, or doctor’s office, or other location.

SOURCE: MacDorman and Declercq (2019, p. 11), based on birth certificate data from the National Vital Statistics System.

entiate between planned hospital births and births that were planned for home but transferred to the hospital. Therefore, the number of planned home births reported in the study is an underestimate of the actual number of births that began as planned home births. Finally, births reported as “out-of-hospital” include home and birth center births as well as births that occurred at a doctor’s office, clinic, or other location (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019).

By Race and Ethnicity6

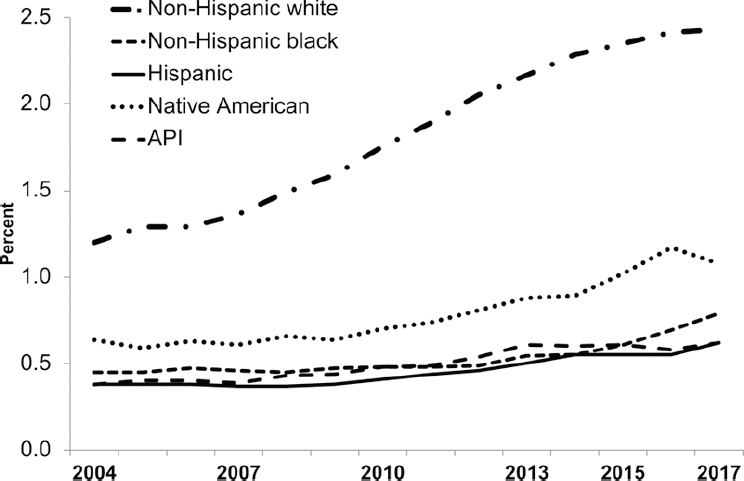

The percentage of out-of-hospital births has increased among all racial/ethnic groups over the past decade, but the most dramatic increase has been among non-Hispanic White women, whose rate more than doubled from 2004 to 2017, from 1.2 percent to 2.43 percent (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019). In 2017, 1 of every 41 births in the United States to a non-Hispanic

___________________

6 Recent changes to race classification data allow for the reporting of multiple race data in vital statistics; however, to ensure consistency of categories over time, multiple race data were bridged back to single race categories for this trend analysis (Martin et al., 2019).

White woman occurred out of hospital (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019). Out-of-hospital births also increased for all other racial/ethnic groups, but with a smaller rate of growth and a lower overall rate (see Figure 1-6). The percentage of home births that were planned varied widely by race and ethnicity, from a low of 39.5 percent for non-Hispanic Black women to a high of 90.9 percent for non-Hispanic White women in 2017 (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019).

By Age and Education

A higher proportion of planned home births (23.5%) were to individuals ages 35 and older compared with birth center (18.1%) and hospital (17.5%) births; see Table 1-1. Conversely, among teens, a higher proportion of births were in a hospital (5.2%) compared with planned home births (<1%). Regarding woman’s education, more planned home (36.3%) and birth center (47.8%) births were to women with a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with hospital (32.2%) births. And a higher proportion of planned home births (23.9%) were to people with less than a high school

NOTE: API = Asian or Pacific Islander.

SOURCE: MacDorman and Declercq (2019, p. 4), based on birth certificate data from the National Vital Statistics System.

TABLE 1-1 Percentage of Births by Level of Education and Place of Birth

| Education of Mother (%) | All Births (n = 3,855,500) |

Hospital (n = 3,793,272) |

Out of Hospitala (n = 62,228) |

Birth Center (n = 19,878) |

Homeb (n = 38,343) |

Planned Homeb,c (n = 28,994) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than high school | 13.3 | 13.2 | 19.9 | 12.8 | 21.9 | 23.9 |

| High school graduate | 25.6 | 25.7 | 14.7 | 11.7 | 15.5 | 13.0 |

| Some college | 28.8 | 28.8 | 26.8 | 27.7 | 26.9 | 26.8 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 32.3 | 32.2 | 38.6 | 47.8 | 35.6 | 36.3 |

NOTES: Column percentage computed per 100 women in specified group. Not-stated responses (<4% for all variables) were dropped before percentages were computed.

aCategory includes 3,273 “other,” 553 “clinic or doctor’s office,” and 181 “unknown” location.

bDoes not include planned home births that were transferred to hospitals.

cExcludes data from California, which did not report planning status of home births.

SOURCE: MacDorman and Declercq (2019).

education, compared with birth center (12.8%) and hospital (13.2%) births (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019).

By Financing

Compared with hospital births, women with planned home and birth center births are far more likely to pay for birth out of pocket rather than through Medicaid or private insurance (employer-sponsored or individually purchased) coverage. In 2017, 43.4 percent of hospital births were paid for by Medicaid, compared with 17.9 percent of birth center births and only 8.6 percent of planned home births. People with planned home births were also less likely to be covered by private insurance. Only 19.0 percent of planned home births were paid for by private insurance, compared with 47.5 percent of birth center and 49.4 percent of hospital births. More than two-thirds (67.9%) of planned home births were paid for out of pocket. Almost one-third of birth center births were paid for out of pocket, but this was the case for only a small percentage (3.4%) of hospital births. A small percentage of births in each birth setting category were reported as paid for by some “other” payment method (MacDorman and Declercq, 2019, p. 5). Table 1-2 shows the distribution of type of financing by birth setting.

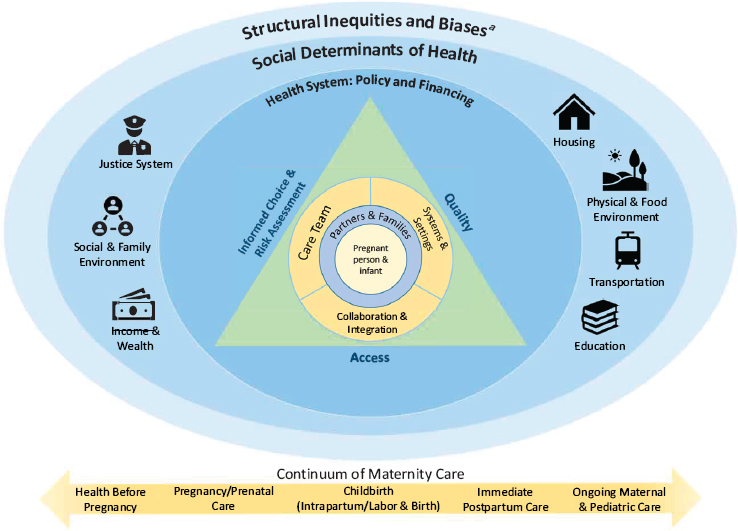

THE COMMITTEE’S CONCEPTUAL MODEL

The committee’s conceptual model (see Figure 1-7) aims to identify key areas for improving the knowledge base around birth settings and levers for improving policy and practice across settings. The triangle at the center indicates three elements that contribute to the ultimate goal of positive outcomes in maternity care: access to care, encompassing both medical insurance and coverage and affordable care options; quality of care; and informed choice about care. The childbearing woman and infant are at the center of that triad (and of the entire graphic), surrounded by the maternity care team; the systems and settings in which the team cares for mothers and infants; and collaboration and coordination, as well as integration, among providers and systems. The maternity care team includes partners, family members, and friends directly involved with support and care during pregnancy and birth, in addition to the clinicians and other professionally prepared members of the team. All of these elements are embedded in the broader social support a woman has or is provided as part of maternity care. The physical setting in which a birth takes place is one part of this overall picture, but it is nested among other elements that are relevant regardless of setting and that can be optimized for positive outcomes across and within different birth settings. As noted in the above discussion of the scope of this study, this triad is equally important along the entire con-

TABLE 1-2 Percentage of Births by Type of Financing and Birth Setting, United States, 2017

| Method of Payment for Delivery (%) | All Births (n = 3,855,500) |

Hospital (n = 3,793,272) |

Out of Hospitala (n = 62,228) |

Birth Center (n = 19,878) |

Homeb (n = 38,343) |

Planned Homec (n = 28,994) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid | 43.0 | 43.4 | 17.5 | 17.9 | 15.4 | 8.6 |

| Private insurance | 49.1 | 49.4 | 29.6 | 47.5 | 20.6 | 19.0 |

| Self-pay | 4.1 | 3.4 | 48.9 | 32.2 | 59.4 | 67.9 |

| Other | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 4.6 |

NOTES: Column percentage computed per 100 women in specified group. Not-stated responses (<4% for all variables) were dropped before percentages were computed.

aCategory includes 3,273 “other,” 553 “clinic or doctor’s office,” and 181 “unknown” location.

bDoes not include planned home births that were transferred to hospitals.

cExcludes data from California, which did not report planning status of home births.

SOURCE: MacDorman and Declercq (2019).

aStructural inequities and biases include systemic and institutional racism. Interpersonal racism and implicit and explicit bias underlie the social determinants of health for women of color.

tinuum of care, beginning with health before pregnancy and continuing through maternal and pediatric care during the first year postpartum.

Around the center triangle are the factors that can affect whether its elements are optimally achieved. These circles illustrate the complex sociocultural environment that shapes health outcomes at the individual level and the opportunities for interventions to improve individual and population health, well-being, and health equity. This environment encompasses social, clinical, financial, and structural factors that contribute to access and informed choice, and to quality of care and outcomes. Of course, many of these factors overlap or interact, and the context and conditions illustrated continue to play an important role in health and well-being throughout the continuum of care. That is, structural inequalities and biases intersect with the social determinants of health as all the layers of the model interact in dynamic, complex ways.

Specifically, the outer circle, “structural inequities and biases,” represents the structural inequities that are historically rooted and deeply embedded in policies, laws, governance, and culture, such that power and resources are

distributed differentially across characteristics of identity (race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexual orientation, and others) (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017).7 This unequal allocation of power and resources—including goods, services, and societal attention—manifests in unequal social, economic, and environmental conditions, represented in the figure as the “social determinants of health” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017, p. 7). These factors include education, employment, nutrition and food, housing, income and wealth, physical environment, transportation, public safety, and social environment (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017, p. 7). It is important to note that although the term “social determinants of health” is widely used in the literature, it may incorrectly suggest that such factors are immutable. It may be more appropriate to say, for example, “social influences on health.” Factors included among the social determinants of health are indeed modifiable, and can be influenced by social, economic, and political processes and policies (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017, p. 116). Thus, one advantage of adopting a social determinants of health lens in the analysis of maternal and newborn health is that it offers the possibility of identifying factors associated with health inequities that may be amenable to change through efforts aimed at prevention or intervention, as discussed further in Chapter 4.

KEY TERMS

The committee was charged with assessing health outcomes by birth setting. In general, we interpreted this task to mean assessing pregnancy, birth, and postpartum outcomes. Pregnancy outcomes are the results of pregnancy from preconception and conception through childbirth. They can include outcomes during pregnancy, such as spontaneous abortion,

___________________

7 The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recently summarized this large body of literature in its report Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity: “The dimensions of social identity and location that organize or ‘structure’ differential access to opportunities for health include race and ethnicity, gender, employment and socioeconomic status, disability and immigration status, geography, and more. Structural inequities are the personal, interpersonal, institutional, and systemic drivers—such as, racism, sexism, classism, able-ism, xenophobia, and homophobia—that make those identities salient to the fair distribution of health opportunities and outcomes. Policies that foster inequities at all levels (from organization to community to county, state, and nation) are critical drivers of structural inequities. The social, environmental, economic, and cultural determinants of health are the terrain on which structural inequities produce health inequities. These multiple determinants are the conditions in which people live, including access to good food, water, and housing; the quality of schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods; and the composition of social networks and nature of social relations” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017, pp. 100–101).

induced abortion, fetal death, and maternal morbidity (illness) or death; they also include positive outcomes, such as a live birth of a healthy baby or patient satisfaction. Birth outcomes are the results of pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, and they may also be influenced by the woman’s health status prior to pregnancy. They can be positive or negative and encompass the condition of both mother and infant following childbirth. For this report, birth outcomes are considered to be both clinical and psychosocial. As noted in the discussion of the scope of this study, moreover, while most of the literature focuses on birth outcomes that are measured early in the postpartum and newborn period, effects of childbearing are salient for this study through the first year postpartum. Limiting outcomes to those that can be measured before hospital discharge fails to include many outcomes that are of great interest to women, families, and society, including maternal–infant attachment, breastfeeding, maternal mood, and general maternal health status. While the committee recognizes that effects of childbearing can be important through the life course, that analysis is beyond the scope of this report. Additional key terms of relevance to this study are defined in Box 1-6.

STUDY METHODS

The committee convened to conduct this study consisted of 14 prominent scholars and practitioners representing a broad array of disciplines, including health care, nursing, midwifery, obstetrics, neonatology, statistics, medical ethics, anthropology, sociology, and financing and public policy. The committee held four in-person meetings and conducted additional deliberations by teleconference and electronic communications during the course of the study. The first and second in-person meetings were information-gathering sessions during which the committee heard from a variety of stakeholders, including the study’s sponsors and representatives from government, academia, health care provider organizations, third-party payers, and women’s health organizations. The third and fourth meetings were closed to the public so the committee could deliberate and finalize its conclusions.

The information-gathering process revealed some strongly held values and goals in both the testimony provided and some of the literature. These values and goals served as important context for the committee’s deliberations, and are reflected in our conclusions when justified by the evidence and models reviewed. The most salient of these values and goals emerging from public testimony and the literature are outlined below:

- The need of women and their children for access to affordable, respectful, responsive, clinically and culturally safe, high-quality care from the prenatal period through at least 1 year postpartum.

- Women’s right to informed choice in maternity care. Informed choice includes having access to options for and choices among birth settings, care providers, and care practices whereby women are cared for with the highest level of respect, bodily autonomy, bodily integrity, quality care, safety, and protection from abuse, and respectful, culturally concordant care is provided in health systems that are actively addressing implicit bias and the pernicious legacy of racism.

- Women’s need for a continuum of health care. Women’s maternal care ideally involves a continuum within a health care and financing system in which affordable, accessible, integrated, risk-stratified, coordinated, comprehensive, and equitable care is delivered by interdisciplinary teams of health care professionals across multiple birth settings.

- Recognition of midwives, obstetrician/gynecologists, family physicians, labor and delivery nurses, pediatricians, neonatologists, doulas, and laborists, among others, as critical contributors to the maternal and child health continuum of care team. Interdisciplinary team col

-

laboration among these personnel, supported by interprofessional education and communication within seamlessly integrated systems of care, can improve the quality of care as well as maternal and infant birth outcomes.

- Community co-located, culturally matched, integrated, and comprehensive services provided by personnel who are knowledgeable about and responsive to that community and have connections and collaborations with a regionalized network of services.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized into seven chapters. Following this introduction, Chapter 2 describes the current landscape of maternal and newborn care in the United States, including the variety of providers and birth settings. Chapter 3 summarizes the epidemiology of clinical and social risks in pregnancy and childbirth at the individual level, such as medical and obstetric risk factors, and the relationship among choice, risk assessment, and informed decision making. Chapter 4 reviews system-level risks in pregnancy and childbirth, including structural inequities and biases, as well as the social determinants of health that influence psychosocial, medical, and obstetric risk. Next, Chapter 5 outlines the data sources and methodology typical of research on birth settings and describes the general strengths and limitations of this literature. Chapter 6 synthesizes and assesses the available literature on health outcomes for home, birth center, and hospital births. Finally, the report concludes with Chapter 7, which summarizes the committee’s key findings and conclusions and presents a path forward for improving maternal and neonatal care for childbearing women and infants in the United States. The Appendix contains biographical sketches of the committee members and staff.