4

Engaging with and Training Community-Based Partners to Improve the Outcomes of At-Risk Populations

Engaging and training community-based partners (CBPs) serving at-risk populations is recommended as part of state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) public health agencies’ community preparedness efforts so that those CBPs are better able to assist at-risk populations they serve in preparing for and recovering from public health emergencies.

Finding Statements and Certainty of the Evidence

| •••• High ••• Moderate •• Low • Very Low | ||

| Finding Statement | Certainty | |

| Culturally tailored preparedness training programs improve public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) knowledge of CBP representatives | •• | |

| Culturally tailored preparedness training programs improve attitudes and beliefs of CBP representatives regarding their preparedness to meet needs of at-risk individuals | • | |

| Culturally tailored preparedness training programs increase CBP disaster planning | • | |

| Culturally tailored preparedness training programs improve the PHEPR knowledge of trained at-risk populations | ••• | |

| Culturally tailored preparedness training programs improve attitudes and beliefs of trained at-risk populations regarding their preparedness | •• | |

| Culturally tailored preparedness training programs improve preparedness behaviors of trained at-risk populations | ••• | |

| CBP engagement in preparedness outreach activities improves the attitudes and beliefs of at-risk populations toward preparedness behaviors | • | |

| CBP engagement and training in coalitions addressing public health preparedness/resilience increases the diversity of coalitions, the coordination of CBPs with other response partners, or capacity to reach and educate at-risk populations before an emergency | • | |

Recommended CBP training strategies include

» the use of materials, curricula, and training formats targeted and/or tailored to the individual CBPs and the at-risk populations they serve

» train-the-trainer approaches that utilize peer or other trusted trainers to train at-risk populations

CBP engagement and training should be accompanied by targeted monitoring and outcome evaluation or conducted in the context of research when feasible so as to improve the evidence base for engagement and training strategies.

Implementation Guidance

![]() Ensure that CBP engagement efforts feature a clearly articulated purpose and goals, a shared language, an acceptable power balance, and a sense of shared ownership

Ensure that CBP engagement efforts feature a clearly articulated purpose and goals, a shared language, an acceptable power balance, and a sense of shared ownership

![]() Ensure that multistakeholder collaborations with CBPs are diverse and inclusive, with particular attention to those groups that are often excluded and marginalized

Ensure that multistakeholder collaborations with CBPs are diverse and inclusive, with particular attention to those groups that are often excluded and marginalized

![]() Engage umbrella organizations (e.g., American Red Cross, United Way) to reach smaller, local, community-based organizations

Engage umbrella organizations (e.g., American Red Cross, United Way) to reach smaller, local, community-based organizations

![]() Consider participatory engagement strategies that allow for ongoing, bidirectional communication with CBPs to build trust and buy-in prior to an emergency

Consider participatory engagement strategies that allow for ongoing, bidirectional communication with CBPs to build trust and buy-in prior to an emergency

![]() Develop formal agreements to clarify the nature of membership roles and responsibilities in collaborations with CBPs

Develop formal agreements to clarify the nature of membership roles and responsibilities in collaborations with CBPs

![]() Consider designating a coordinator to maintain the focus of coalitions, mitigate problems of competing priorities, and minimize perceptions of uneven power dynamics

Consider designating a coordinator to maintain the focus of coalitions, mitigate problems of competing priorities, and minimize perceptions of uneven power dynamics

![]() Identify information technology (e.g., resource databases) and existing data sources that can be used to facilitate more timely engagement of CBPs and to link at-risk populations with needed services during an emergency

Identify information technology (e.g., resource databases) and existing data sources that can be used to facilitate more timely engagement of CBPs and to link at-risk populations with needed services during an emergency

![]() Tailor the curriculum and format of CBP preparedness training programs to the learning needs and preferences of specific audiences, and ensure that they are culturally sensitive and appropriate

Tailor the curriculum and format of CBP preparedness training programs to the learning needs and preferences of specific audiences, and ensure that they are culturally sensitive and appropriate

![]() Consider soliciting stakeholder feedback in the evaluation of training program materials and content

Consider soliciting stakeholder feedback in the evaluation of training program materials and content

DESCRIPTION OF THE PRACTICE

Defining the Practice

The committee examined the evidence for strategies used to engage with and train community-based partners (CBPs) to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations (defined in Box 4-1) who may be disproportionately affected by a public health emergency. The committee also examined the factors that may facilitate or act as barriers to CBP engagement and training (e.g., trust, organizational capacity). Engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations falls primarily under Capability 1: Community Preparedness (CP Capability) in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capabilities: National Standards for State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Public Health (CDC PHEPR Capabilities) (CDC, 2018a). However, addressing the access and functional needs of at-risk individuals is a topic that cuts across the CDC PHEPR Capabilities (see Box 4-2).

For the purposes of this review, the committee defined CBPs to include those organizations and individuals that are representative of a community or a defined segment of a community and have established relationships with and/or serve at-risk populations. CBPs may include governmental (e.g., social services agencies) and nongovernmental (e.g., faith- and community-based organizations) entities, as well as individuals who represent or routinely work with populations that may be at increased risk of adverse outcomes during and following a public health emergency (e.g., community health workers and tribal leaders). This definition of CBPs distinguishes practices considered for this review from the broader class of community engagement practices that fall within the CP Capability and are aimed at improving community preparedness and resilience more generally. Practices aimed at directly engaging at-risk populations without the involvement of CBPs as an intermediary were outside the scope of this review.

In public health, the engagement and training of CBPs to better reach and improve outcomes for individuals with social vulnerabilities has much broader application beyond preparedness and response. For example, public health practitioners may seek to leverage relationships with trusted community-based organizations to improve childhood vaccination rates (Willis et al., 2016) or HIV management (Remien et al., 2015) in socially vulnerable groups. Although limitations of time and resources necessitated the committee’s narrow focus on CBP engagement and training practices oriented specifically to public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR), the committee recognizes that this broader body of evidence from public health practice may have some applicability to the practices evaluated in this review.

Scope of the Problem Addressed by the Practice

The impacts of disasters and public health emergencies on health and well-being are not distributed equally across an affected population (HHS, 2011). Rather, the impacts are often felt disproportionately by groups with features that limit individuals’ capability to respond or the effectiveness of such traditional response practices as evacuation or English-language messages (CDC, 2015). These at-risk populations are often those who are already the most vulnerable in a community and suffer from health and other disparities (Blumenshine et al., 2008). In the PHEPR context, social determinants of health (e.g., access to health care services, safe housing, and healthy food) can also be framed as social determinants of vulnerability (IOM, 2015). Such issues, which are often structural in nature, can be resolved only

| BOX 4-2 | HOW ENGAGING WITH AND TRAINING COMMUNITY-BASED PARTNERS TO IMPROVE THE OUTCOMES OF AT-RISK POPULATIONS RELATES TO THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION’S PHEPR CAPABILITIES |

Capability 1: Community Preparedness—emphasizes the need for processes to identify at-risk populations that may be disproportionately impacted by public health emergencies and the need for collaborations with community partners to assess and plan for the access and functional needs of those populations. It also promotes training and education of community partners and stakeholders to support preparedness and recovery for at-risk populations.

Capability 2: Community Recovery—the transition between response and recovery is rarely well defined, and in both phases community-based partners (CBPs) can provide critical services to mitigate the effects of public health emergencies on at-risk populations and to assist with their recovery. Partnerships established with CBPs during the preparedness phase may be leveraged during recovery to coordinate services, identify and address gaps, and ensure that at-risk populations are integrated into community recovery planning efforts.

Capability 3: Emergency Operations Coordination—includes the ability to coordinate with emergency management, internal public health stakeholders, and external CBPs and to direct and support the response to an incident or event with public health or health care implications. Central to this Capability are identifying and sharing knowledge about public health risks, hazards, threats, and vulnerabilities. In this function, CBPs are important to understanding the needs of at-risk populations and help coordinate emergency response.

Capability 4: Emergency Public Information and Warning—includes practices to reach at-risk populations with public health messages during an emergency. There is growing recognition of the need to leverage trusted messengers when communicating risks and guidance to at-risk populations.

Capability 6: Information Sharing—refers to the effective interagency exchange of health-related information and situational awareness among different government agencies and other partners. CBPs offer vital avenues to and from at-risk populations that are necessary to conduct health-related information exchange and to gather situational awareness data.

SOURCE: CDC, 2018a.

through a substantial commitment to reducing the conditions that contribute to increased risk of adverse outcomes, so that the response of a community can be more effective when an emergency rises. Hurricane Katrina and its effects on at-risk populations served as a wake-up call for the need to prioritize and invest in preparedness for these populations and communities (Gibson and Hayunga, 2006; HHS, 2011; Turner et al., 2010; Wells et al., 2013). Failure to attend adequately to the needs of these populations before an emergency occurs risks exacerbating the underlying conditions that contribute to disparities in outcomes.

The challenges faced by at-risk populations may intersect and magnify each other. For example, ethnic communities with limited English proficiency may have difficulty receiving public health messages and may be distrustful of the government agencies disseminating them, or may have fewer resources for response actions, such as evacuation (Messias et al., 2012). This pernicious combination of factors was evident during the 2017 California

wildfires, when it took several days to get appropriately translated risk messages to migrant farmworkers who continued working in the fields, often without proper respiratory protection, despite the hazardous conditions (NASEM, 2020). Moreover, the same family networks that may be supportive in one set of circumstances may make evacuation more challenging if elder members are difficult to move and strain the network’s resources (Eisenman et al., 2007; Messias et al., 2012; Rowel et al., 2012). This example emphasizes the interconnectedness of populations such that when the needs of vulnerable populations are not adequately attended to, the risks to those who otherwise would not have been identified as at risk may be exacerbated. Consequently, focusing on meeting the needs of these populations before, during, and after a public health emergency has the potential to benefit the community writ large.

Integration of at-risk populations into emergency preparedness has been identified as a pressing need that requires more than recognizing that these populations will face particular challenges or including mention of them in preparedness plans; proactive planning for responses is needed (Edgington et al., 2014; Gibson and Hayunga, 2006; NCD, 2005). Hurricane Sandy demonstrated that socially, physically, and geographically vulnerable populations often have limited capacity to take protective action when facing acute adversity (Hernandez et al., 2018). Understanding and overcoming the barriers faced by such populations will necessitate their engagement in the development of response protocols. Failure to adequately meet the needs of at-risk populations following a disaster or public health emergency contributes to mistrust that may pose a barrier to their engagement and the engagement of CBPs that serve them in future events.

Historically, governmental preparedness programs, messages, and messengers have been best suited to mainstream audiences (Eisenman et al., 2009; Fothergill et al., 1999). Racially and ethnically diverse at-risk populations of low socioeconomic status may perceive government as unfair, and cultural and language factors may impede the uptake of institution-derived programs and messages (Andrulis et al., 2011; Eisenman et al., 2004, 2012). Furthermore, government entities themselves face institutional-level barriers to best serving at-risk populations, such as a lack of funds for at-risk and diversity initiatives, limited knowledge about diverse communities, and limited collaboration with communities and potential partners based therein (Bevc et al., 2014).

CBPs can be vital partners in reaching at-risk populations both before and after a public health emergency as they are often trusted agents familiar with and relied on by these populations for care and information during nonemergency situations (Eisenman et al., 2009; Gin et al., 2016). Existing networks with at-risk populations established for other purposes (e.g., focused on ensuring access to health and social services) can be useful in engaging these populations in preparedness efforts. Public health plays a key role in establishing and maintaining partnerships that promote community preparedness and response activities targeted at at-risk populations. However, little guidance is available on evidence-based strategies for developing and maintaining these partnerships or on the best approaches for related training for CBPs. PHEPR practitioners have expressed the need to better understand how best to implement partnerships and train CBPs in PHEPR (DHS, 2018).

OVERVIEW OF THE KEY REVIEW QUESTIONS AND ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK

Defining the Key Review Questions

The overarching review question that guided this review addresses the effectiveness of different strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk

populations after public health emergencies. Engaging with CBPs to meet the needs of at-risk populations may take place in the preparedness, response, and recovery phases of the emergency cycle. Recovery practices were outside the committee’s scope of work, but separate key review sub-questions were formulated for the preparedness and response phases. The committee also posed sub-questions related to documented benefits and harms of CBP engagement and training strategies and the factors that create barriers to and facilitators of implementation of such strategies (see Box 4-3).

Analytic Framework

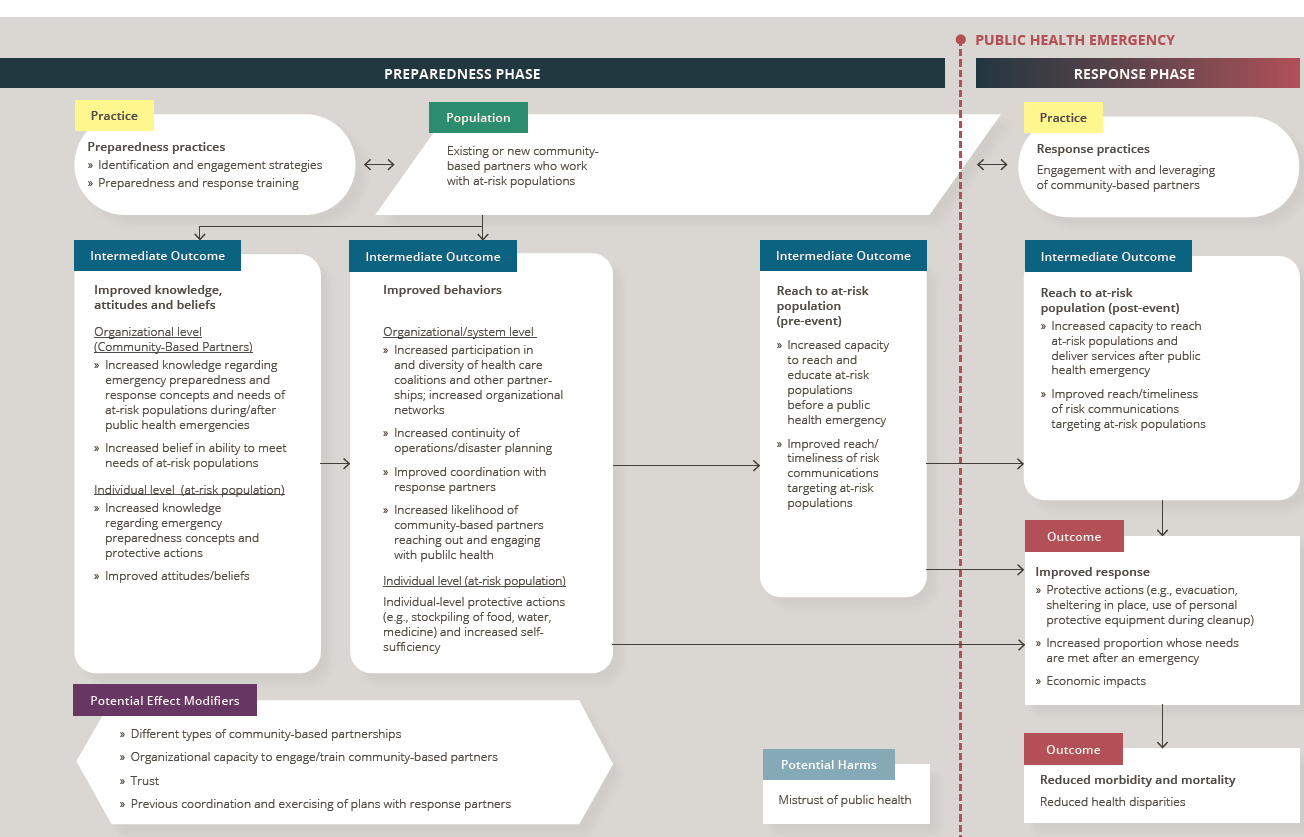

For the purposes of this review, the committee developed an analytic framework to present the causal pathway and interactions between CBP engagement and training approaches and outcomes of interest (see Figure 4-1). The theory behind the practice is that when public health agencies adequately engage with and train CBPs who have established relationships with and/or serve at-risk populations to impart preparedness and response knowledge and concepts, the result is increased capacity to reach these populations before and during a public health emergency, and thus the potential to reduce disaster-associated morbidity and mortality and ameliorate health disparities.

Engaging and training CBPs may improve the outcomes of at-risk populations following a public health emergency through a number of presumed pathways. Such pathways generally focus on ensuring at-risk individuals’ postdisaster access to critical services and/or resources (e.g., food, medication, information). CBP intermediaries may provide needed services and resources directly or may assist public health agencies (or other emergency responders) in reaching at-risk populations to deliver these services and resources before or after an emergency (e.g., by enabling access through their venues or by passing along information on how to access services and resources). CBPs also can be well positioned to help ensure the cultural appropriateness of preparedness and response materials, services, and training so they are functionally accessible (e.g., available in different languages for non-English-speaking individuals) and likely to be well received (Andrulis et al., 2011).

| BOX 4-3 | KEY REVIEW QUESTIONS |

What is the effectiveness of different strategies for engaging with and training community-based partners (CBPs) to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations after public health emergencies?

- What is the effectiveness of strategies for engaging with and training CBPs before a public health emergency?

- What is the effectiveness of strategies for engaging with and leveraging existing CBPs during a public health emergency?

- What benefits and harms (desirable and/or undesirable impacts) of different strategies for engaging with and training community-based partners have been described or measured?

- What are the barriers to and facilitators of effective engagement and training of CBPs?

NOTES: Arrows in the framework indicate hypothesized causal pathways between interventions and outcomes. Double-headed arrows indicate feedback loops.

Training CBPs may help better prepare them to mitigate the effects of public health emergencies on at-risk populations. The objectives of such training may include the following:

- Improving the knowledge of CBP employees and volunteers with respect to disaster risks (to themselves, their organizations, and the at-risk populations they serve) and preparedness approaches. Such training may help ensure continuity of operations and educate CBPs in providing critical services, resources, and information to at-risk populations after a public health emergency.

- Developing collaborations, engaging in constructive interactions, and coordinating efforts with governmental and other response partners in advance of public health emergencies. Preexisting relationships between CBPs and other response partners may facilitate meeting the needs of at-risk populations (e.g., access to culturally and linguistically appropriate risk messages, as well as resources and critical services).

- Educating CBPs in how to train members of at-risk populations so they are better prepared to meet their own needs during and after a public health emergency or to obtain assistance from their social networks. At-risk individuals may be more receptive to training on protective preparedness behaviors when it is delivered by trusted messengers, such as CBP representatives.

OVERVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION1

This section summarizes the evidence from the mixed-method review examining strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations. Following the summary of the evidence of effectiveness, summaries are presented for each element of the Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework (encompassing balance of benefits and harms, acceptability and preferences, feasibility and PHEPR system considerations, resource and economic considerations, equity, and ethical considerations), which the committee considered in formulating its practice recommendation. Full details on the review strategy and findings can be found in the appendixes: Appendix A provides a detailed description of the study eligibility criteria, search strategy, data extraction process, and individual study quality assessment criteria, Appendix B1 provides a full description of the evidence, including the literature search results, evidence profile tables, and EtD framework for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations; and Appendix C links to all of the commissioned analyses that informed this review. Table 4-1 shows the types of evidence included in this review.

Effectiveness

Seven quantitative comparative and four quantitative noncomparative studies directly address the overarching key question regarding the effectiveness of different strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations after public health emergencies. (Refer to Section 1, “Determining Evidence of Effect,” in Appendix B1 for additional detail.) All 11 studies describe strategies for engaging with or training CBPs before a public health emergency (preparedness phase); no quantitative research studies were found that address the effectiveness of strategies for engaging with and leveraging existing CBPs

___________________

1 To enhance readability for an end user audience, this section does not include references. Citations supporting the findings in this section appear in Appendix B1.

| Evidence Typea | Number of Studies (as applicable)b |

|---|---|

| Quantitative comparative | 7 |

| Quantitative noncomparative (postintervention measure only)c | 4 |

| Qualitative | 23 |

| Modeling | 0 |

| Descriptive surveys | 7 |

| Case reports | 15d |

| After action reports | N/A |

| Mechanistic | N/A |

| Parallel (systematic reviews)e | 13 |

a Evidence types are defined in Chapter 3.

b Note that sibling articles (different results from the same study published in separate articles) are counted as one study in this table. Mixed-method studies may be counted in more than one category.

c Quantitative noncomparative studies were considered separately for the purpose of evaluating evidence of effect but were included in the synthesis of case reports (or qualitative evidence in the case of mixed-method studies) to identify themes relevant to the Evidence to Decision framework.

d A sample of case reports was prioritized for inclusion in this review based on relevance to the key questions, as described in Chapter 3.

e Parallel evidence for the purposes of this review was derived from existing systematic reviews of similar practices from outside the PHEPR context.

during a public health emergency (response phase strategies). Ten of these 11 studies evaluate strategies that involve both engaging and training CBPs.

Strategies identified by the committee in the body of evidence fall into two broad categories: (1) those aimed at training and/or engaging individual CBPs with a goal of reaching particular at-risk populations (training programs may be targeted solely to CBPs or may be aimed at training both CBPs and members of the at-risk populations they serve); and (2) those aimed at engaging multiple CBPs in a coalition or other multistakeholder partnership. From these two categories, three strategies for training and/or engaging CBPs were identified and evaluated separately:

- implementation of culturally tailored2 preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve,

- engagement of CBPs in preparedness outreach activities targeting at-risk populations, and

- engagement and training of CBPs in coalitions addressing public health preparedness/resilience.

Consistent with the methods described in Chapter 3, in making its final judgment on the evidence of effectiveness for strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations, the committee considered other types of evidence that could inform a determination of what works for whom and in which contexts, ultimately coming to

___________________

2 The committee uses the term “culturally tailored” to describe an intervention that is targeted and/or tailored to ensure that it meets the unique needs of the target group by incorporating its experiences and norms and values.

consensus on the certainty of the evidence (COE) for each outcome. Including other forms of evidence beyond quantitative comparative studies is particularly important when assessing evidence in settings where controlled studies are challenging to conduct and/or other forms of quantitative comparative data are difficult to obtain. Descriptive evidence from real-world implementation of practices offers the potential to corroborate research findings or explain differences in outcomes in practice settings, even if it has less value for causal inference. Moreover, qualitative studies can complement quantitative studies by providing additional useful evidence to guide real-world decision making, because well-conducted qualitative studies produce deep and rich understandings of how interventions are implemented, delivered, and experienced. Other forms of evidence considered for evaluation of effectiveness included findings from quantitative data reported in case reports that involved a real disaster or public health emergency, and parallel evidence from systematic reviews on community engagement and cultural tailoring of interventions outside the PHEPR context. The parallel evidence was considered recognizing that the engagement and training of CBPs to better reach and improve outcomes for individuals with social vulnerabilities has much broader application in public health beyond the PHEPR context, and the committee believed that this broader body of evidence may have some applicability to the PHEPR activities evaluated in this review.

Implementation of Culturally Tailored Preparedness Training Programs for CBPs and At-Risk Populations They Serve

The evidence suggests that culturally tailored preparedness training may be effective in improving outcomes for at-risk populations following a public health emergency, although there is little evidence linking preparedness phase outcomes (e.g., improved knowledge and preparedness behaviors) with health and other outcomes after an event. There is low COE based on three quantitative studies that culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve improve the PHEPR knowledge of trained CBP representatives, and one quantitative study yielded very low COE that such training improves the attitudes and beliefs of CBP representatives regarding their preparedness to meet the needs of at-risk populations or increases their organizations’ disaster planning.

When at-risk populations are trained by trained CBP representatives using a train-the-trainer model or at the same time as CBP representatives, there is moderate COE supported by four quantitative studies that culturally tailored preparedness training programs improve the PHEPR knowledge of those trained at-risk populations. Improved PHEPR knowledge may prompt trained at-risk individuals to engage in preparedness behaviors including stockpiling critical supplies and developing a family communication plan (moderate COE based on four quantitative studies). Three quantitative studies yielded low COE that culturally tailored preparedness training programs improve the preparedness attitudes and beliefs of trained at-risk populations. It should also be noted that, while these findings suggest that this training improves the preparedness of both CBPs and, in some cases, at-risk individuals, short follow-up periods were employed in these studies. Therefore, it is unclear how long these effects last and whether they translate to improved outcomes for at-risk populations following a public health emergency.

Engagement of CBPs in Preparedness Outreach Activities Targeting At-Risk Populations

The committee found limited evidence on the effects of engaging CBPs in preparedness outreach activities targeting at-risk populations. Based on a single quantitative study, there

is very low COE that CBP engagement in preparedness outreach activities improves the attitudes and beliefs of at-risk populations toward preparedness behaviors. No impact data were identified for other relevant outcomes.

Engagement and Training of CBPs in Coalitions Addressing Public Health Preparedness/Resilience

The committee found limited evidence on the effects of engaging and training CBPs in coalitions addressing public health preparedness/resilience. There is very low COE based on a single quantitative study that CBP engagement and training in such coalitions increases the diversity of coalitions, the coordination of CBPs with other response partners, or capacity to reach and educate at-risk populations before an emergency.

Balance of Benefits and Harms

Engagement and training of CBPs in PHEPR can benefit communities in multiple ways, particularly when undertaken using a participatory approach and, in the context of multistakeholder collaborations, when inclusive of diverse membership. These benefits can be observed at the individual, organizational, and community and system levels.

At the individual level, engaging and training CBPs may increase reach to at-risk populations, many of which are traditionally underserved. This increased reach may yield opportunities to improve at-risk individuals’ knowledge regarding risks from public health emergencies and potential mitigation strategies, which in turn may effect change in preparedness behaviors. Increased reach following a public health emergency may also ensure access of at-risk individuals to critical services. (Evidence source: synthesis of evidence of effect, qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis.)

At the organizational level, benefits of CBP engagement and training may include capacity building and enhanced CBP preparedness to meet the needs of at-risk populations following a public health emergency through increased PHEPR knowledge and integration of preparedness into CBP core services. (Evidence source: synthesis of evidence of effect, qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis.) In addition, public health agencies and CBPs may benefit from improved mutual awareness of existing community and organizational roles and capacities during routine times. This improved awareness provides the basis for leveraging and coordinating available services when an emergency event occurs, and also aids in identifying and developing strategies for covering gaps in needed services. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis.)

Benefits observed at the community and system level include new partnerships that enhance the inclusion of CBPs and promote a shared sense of ownership of community preparedness efforts. Relationship building may benefit routine operations, create opportunities for new collaborations, and facilitate coordination of partners during emergencies. Other community and system-level benefits include greater appreciation of varied community and cultural perspectives (cultural competence) and understanding of the needs and expectations of underserved populations, as well as opportunities for shared learning and enhanced trust in public health and other government agencies. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis.)

There are also a number of potential undesirable effects related to engagement and training of CBPs, including the potential to raise difficult and uncomfortable issues (e.g., implicit bias, marginalization), especially when trainers come from socially advantaged groups (e.g., based on race, education, or social status) and those being trained come from

less advantaged groups. Additionally, people can become disenchanted with preparedness-focused collaborations when past collaborations have failed to achieve desired results or when members have had negative experiences (e.g., conflict, perceived power imbalance). Such disenchantment may impede future engagement efforts. There is also potential for disenchantment with preparedness training if there are no opportunities to apply it (in routine or emergency contexts). Finally, when collaborations cannot be sustained because of the often short-term nature of preparedness funding or shifting priorities, trust and confidence issues may be exacerbated. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 2, “Balance of Benefits and Harms,” in Appendix B1 for additional detail.)

Acceptability and Preferences

CBPs generally value inclusion and shared ownership of community preparedness efforts and are willing to collaborate with public health agencies. Participatory approaches, leadership support, organizational commitment to CBP engagement and training, and transparency are likely to be important facilitators of acceptability. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis, evidence from descriptive surveys.)

Some public health departments may require an internal culture change to embrace and align with a community partnering approach. Reframing public health emergency preparedness activities to include a commitment to leveraging existing community health activities, along with a strong emphasis on health equity, can facilitate this organizational shift toward collaborative strategies and community preparedness. (Evidence source: case report evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 3, “Acceptability and Preferences,” in Appendix B1 for additional detail.)

Feasibility and PHEPR System Considerations

Engaging and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations may be time and resource intensive, with intensity varying depending on the specific strategy. Capacity challenges (e.g., human and nonhuman resource limitations, policy impediments) and competing priorities, for both public health organizations and CBPs, are likely to be common barriers. Feasibility may be improved by working strategically to reduce capacity-related barriers through financial support and by leveraging opportunities to expand capacity, for example, through coordination. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis, evidence from descriptive surveys.)

Studies note legal issues regarding separation of church and state as a potential consideration when engaging faith-based organizations. Guidelines in accordance with the U.S. and state constitutions that include nondiscriminatory requirements, separation of public health services and religious activities, and no furthering of religious activities may be helpful in addressing this issue. (Evidence source: case report evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 4, “Feasibility and PHEPR System Considerations,” in Appendix B1 for additional detail.)

Resource and Economic Considerations

Community preparedness efforts may be perceived as having to do more with no concomitant increase in resources. Framing preparedness efforts as an adaptation of existing activities rather than as additional services may reduce concerns regarding resource requirements. Many CBPs and public health agencies are already facing challenges in sustaining

underfunded programs while dealing with high staff turnover, which may discourage engagement efforts and impede the ability of CBP representatives to attend trainings. Competing priorities for limited resources may necessitate prioritization of engagement and training initiatives (e.g., targeting specific at-risk groups based on local needs), but identifying opportunities to leverage existing resources and programs can help address financial constraints. Collaboration building and maintenance require a long-term investment. Such activities need to be undertaken with an understanding of the importance of longitudinal funding and appropriate outcome evaluations. Failure to sustain partnerships and lack of clear outcomes from engagement and training initiatives may contribute to disenchantment with preparedness-related engagement efforts. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 5, “Resource and Economic Considerations,” in Appendix B1 for additional detail.)

Equity

Although none of the studies included in this review assess the potential effects on equity outcomes, engagement and training of CBPs is presumed to yield equity-related benefits by mitigating the often disproportionate effects of disasters on at-risk populations, many of which have been marginalized historically. The body of qualitative studies suggests that representation and meaningful participation in community preparedness efforts may help counteract feelings of being discounted and mitigate mistrust associated with government initiatives in some populations. In the absence of an inclusive approach to engagement and training, however, many CBPs will continue to be underrepresented, with continued marginalization of the at-risk populations with whom they work. Such models as community-based participatory research that promote two-way knowledge exchange, equal power in the development and evaluation of programs, and building of community capacity to apply findings may help promote equitable outcomes, mutual respect, and inclusive participation, but this is an important research gap. As discussed further in the section below on evidence gaps and future research priorities, equity outcomes need to be measured in future studies to better capture the opportunities to embrace a health equity framing and community asset approach to CBP engagement and preparedness training. Careful attention is needed to ensure that participants in CBP engagement and training efforts are representative of the populations intended to be served. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 6, “Equity,” in Appendix B1 for additional detail.)

Ethical Considerations

The section above on equity notes several ways in which engaging communities, when done well, can promote the ethical principles of justice, or fairness, and equity. The earlier section on balancing benefits and harms also describes some ways in which poorly designed or implemented engagement efforts, even when intended to promote principles of transparency and accountability, can generate mistrust, frustration, or alienation. Overall, these observations suggest that engaging communities is ethically justified if it achieves harm reduction and/or benefit promotion for relevant stakeholders. Similarly, if engaging communities in preparedness activities is an efficient means of achieving better preparedness, it is supported by the principle of stewardship, which often is considered to be of special importance in public health emergencies, when resources can be very limited. Still, it is important to bear in mind that community engagement, like all human relationships, also can

hold intrinsic value. That is, building open and trusting relationships is important because it reflects the value placed on respect for persons and communities. The principle of respect for persons and communities posits that one has a fundamental obligation to engage people in decisions that might affect their well-being and the well-being of those they care about, and this holds true even if doing so does not change ultimate decisions. (Evidence source: committee discussion drawing on key ethics and policy texts. Refer to Section 7, “Ethical Considerations,” in Appendix B1 for additional detail.)

CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

The following considerations for implementation are drawn from the committee’s synthesis of evidence of effectiveness, the qualitative evidence synthesis, and the synthesis of case report evidence. The findings from these syntheses are presented in Appendix B1. Note that this is not an exhaustive list of considerations; additional implementation resources should be consulted before the practice recommendation is implemented.

Facilitators for CBP Engagement

The effectiveness of efforts to engage CBPs in preparedness and response to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations will likely be improved by a shared understanding and acceptance of the aims and operating aspects of the collaboration. Specifically, it is important to attend to clearly articulating a purpose and goals, adopting a shared language, bridging differences in decision-making processes, and ensuring that there are no unacceptable differentials in power. Participatory approaches are likely to enhance effectiveness by improving cultural appropriateness, building a sense of shared ownership, and enhancing CBP capacity. Additionally, multistakeholder collaborations are likely to be effective in reaching and improving the outcomes of at-risk populations when CBP membership is diverse and inclusive, with particular attention to those who are often excluded and marginalized and services that are aligned with the needs of the target audience. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis.)

Engaging umbrella organizations that often serve at-risk populations (e.g., American Red Cross, United Way) may serve to connect local public health agencies with smaller, local, community-based organizations to which these agencies would not otherwise have access. Attention will also be needed, however, to developing connections with populations that are not formally served by an agency or provider (e.g., by reaching out to neighborhood and grassroots groups, including faith-based organizations and limited-English-speaking communities). Strategies that allow for ongoing, bidirectional communication with CBPs may help build trust and buy-in prior to an emergency, which could then be leveraged to foster more effective engagement during an emergency. (Evidence source: case report evidence synthesis.)

Formal agreements may help clarify the nature of membership roles and responsibilities in collaborations, which in turn can aid in setting expectations and minimize conflicts over inequitable participation. It may be beneficial for such agreements to openly address how perceived barriers and harms from past experiences will be minimized. Important elements of such agreements include expectations for attendance, participation, and engagement; roles of individual members within the coalition; and organizational commitment. A designated coordinator may also help maintain the focus of a coalition, mitigate problems associated with competing priorities, and minimize perceptions of uneven power dynamics among the coalition members. Consideration is needed as well to the time commitment required for

this role so as not to add responsibilities to an already overburdened employee. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis.)

One case report shows that leveraging information technology, such as a community-based resource database, may facilitate more timely engagement of CBPs and link at-risk populations with needed services during an emergency. Another suggests that data already being collected by agencies serving at-risk populations could be leveraged if stripped of any identifying or confidential information, although difficulties could be faced in achieving the necessary trust and buy-in from CBPs. (Evidence source: case report evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 8, “Facilitators for CBP Engagement,” in Appendix B1 for additional detail.)

Facilitators for CBP Training

Preparedness trainings are more likely to be effective at recruiting, engaging, and educating CBPs when their curriculum and format are tailored to the learning needs and preferences of specific audiences and are culturally sensitive and appropriate. Soliciting stakeholder feedback in the development and evaluation of program materials and training content can help ensure the quality of materials and promote stakeholder buy-in. Highlighting the importance of personal preparedness and self-care during partner trainings may also help promote buy-in for their role as promoters of client preparedness and may enable providers to serve those in need more effectively. In implementing training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve, the following are also important considerations:

- employing capable, credible, and trusted trainers;

- making training accessible through location (physical or virtual) and affordability;

- adjusting the length of any training session to accommodate learners’ attention spans and availability of time;

- facilitating bidirectional discussion, interaction, and feedback loops in training activities; and

- evaluating training and facilitating opportunities for deliberate practice.

(Evidence source: synthesis of evidence of effectiveness, qualitative evidence synthesis, case report evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 9, “Facilitators for CBP Training,” and Section 1, “Determining Evidence of Effect,” in Appendix B1 for additional detail.)

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION, JUSTIFICATION, AND IMPLEMENTATION GUIDANCE

Practice Recommendation

Engaging and training community-based partners (CBPs) serving at-risk populations is recommended as part of state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies’ community preparedness efforts so that those CBPs are better able to assist at-risk populations they serve in preparing for and recovering from public health emergencies. Recommended CBP training strategies include

- the use of materials, curricula, and training formats targeted and/or tailored to the individual CBPs and the at-risk populations they serve; and

- train-the-trainer approaches that utilize peer or other trusted trainers to train at-risk populations.

CBP engagement and training should be accompanied by targeted monitoring and outcome evaluation or conducted in the context of research when feasible so as to improve the evidence base for engagement and training strategies.

Justification for the Practice Recommendation

The practice recommendation is based on moderate certainty of the evidence (COE) that culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs, when also used to train at-risk populations, improve the public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) knowledge and protective preparedness behaviors of at-risk populations. There is low COE that culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and the at-risk populations they serve are effective in increasing CBP representatives’ PHEPR-related knowledge and improving the attitudes and beliefs of trained at-risk populations regarding their preparedness.

The recommended training strategies were found to be beneficial in multiple different at-risk populations, strengthening the conclusion that the evidence is likely applicable to populations beyond those in which the strategies have been evaluated. However, the limited number of studies for each population indicates a need for additional research and evaluation. For example, only one study evaluates the effectiveness of strategies for engaging and training tribal community partners, and none of the studies were conducted in territorial settings.

Although there is insufficient evidence to recommend specific strategies for engaging CBPs in PHEPR outreach activities targeting at-risk populations or for engaging CBPs in community coalitions, the qualitative evidence suggests numerous benefits of CBP engagement in public health preparedness and response. CBPs appear to support and value engagement and training, particularly when implemented using a participatory approach, but capacity limitations for both CBPs and public health organizations should be considered when selecting specific strategies.

Implementation Guidance

Considerations for CBP Engagement

- Ensure that CBP engagement efforts feature a clearly articulated purpose and goals, a shared language, an acceptable power balance, and a sense of shared ownership.

- Ensure that multistakeholder collaborations with CBPs are diverse and inclusive, with particular attention to those groups that are often excluded and marginalized.

- Engage umbrella organizations (e.g., American Red Cross, United Way) to reach smaller, local, community-based organizations.

- Consider participatory engagement strategies that allow for ongoing, bidirectional communication with CBPs to build trust and buy-in prior to an emergency.

- Develop formal agreements to clarify the nature of membership roles and responsibilities in collaborations with CBPs.

- Consider designating a coordinator to maintain the focus of coalitions, mitigate problems of competing priorities, and minimize perceptions of uneven power dynamics.

- Identify information technology (e.g., resource databases) and existing data sources that can be used to facilitate more timely engagement of CBPs and to link at-risk populations with needed services during an emergency.

Considerations for CBP Training

- Tailor the curriculum and format of CBP preparedness training programs to the learning needs and preferences of specific audiences, and ensure that they are culturally sensitive and appropriate.

- Consider soliciting stakeholder feedback in the evaluation of training program materials and content.

EVIDENCE GAPS AND FUTURE RESEARCH PRIORITIES

None of the strategies for engaging with and training CBPs reviewed by the committee are supported by high COE. For strategies to engage CBPs in preparedness/resilience-focused coalitions or outreach activities targeting at-risk populations, there is very low COE regarding effectiveness, indicating a need for further research to expand the body of evidence on these CBP engagement and training strategies. The committee’s commissioned qualitative evidence synthesis suggests a number of engagement and training approaches for which empirical data are limited (e.g., framing of preparedness efforts in terms of community resilience, use of virtual versus in-person training formats). Other novel strategies for leveraging CBPs to improve preparedness and postevent outcomes for at-risk populations that have not yet been rigorously evaluated through research studies include employing audience segmentation approaches (Adams et al., 2017), activating social networks, activating home health workers (Eisenman et al., 2014), working with pharmacists or the hospital discharge process to improve preparedness (e.g., with respect to medications) (Carameli et al., 2013), and using behavioral economic approaches.

The committee noted a number of limitations in the body of research it reviewed that need to be addressed in future research to advance the state of the science on CBP engagement and training strategies. The use of objective, validated measures, when feasible, and the collection of baseline data would mitigate concerns related to risk of bias and strengthen the conclusions that can be drawn regarding causal relationships between practices and outcomes. Particularly concerning is the absence of long-term outcomes from which conclusions can be drawn about the duration of the practice’s effects. For example, evaluation of training effectiveness was almost always conducted immediately following the training, and it is unclear how long such knowledge is retained. Future research needs to include longer-term follow-up outcomes and, for training interventions, to evaluate the frequency of refresher training necessary to ensure that perishable knowledge is retained. As discussed earlier in this chapter, accomplishing this will require that funders acknowledge and support the need for long-term investments in research studies.

Another observed limitation of the existing body of research is the absence of evidence linking pre-event intermediate outcomes (e.g., posttraining knowledge, preparedness behaviors) to improved outcomes for at-risk populations after a public health emergency. Although this evidence gap is challenging to address through prospective research studies given uncertainty as to the location and timing of future emergencies, communities that have made investments in CBP engagement in preparedness activities and training need to consider how the effect of those investments can be rigorously evaluated in the event of a public health emergency.

While it is encouraging that engagement and training strategies have been evaluated for multiple types of CBPs (e.g., nongovernmental social services organizations, faith-based organizations, community health workers) that work with different types of at-risk populations (e.g., low-income minorities, adults with disabilities, tribal populations), the limited number of studies for each such population makes conclusions regarding the applicability of the evidence base premature. It will be important for future studies not only to replicate the findings of previous studies in the same populations, but also to consider other CBPs and at-risk populations not addressed in the current literature base.

There also are important knowledge gaps related to the implementation of CBP engagement and training strategies in real-world settings. For example, capacity limitations of CBPs are cited in the qualitative and case report literature as barriers to engagement and training. There also may be barriers to preparedness behaviors promoted in trainings targeting at-risk

populations, such as insurance barriers to stockpiling extra medications (Carameli et al., 2013). Qualitative studies may inform strategies for overcoming such barriers that can then be tested and evaluated in order to translate research into practice. Simulations and tabletop exercises offer opportunities to identify gaps in partnerships with community organizations serving at-risk populations using real-world scenarios and to better prepare for real-time decision making in the midst of a public health emergency (Chandra et al., 2015; Paige et al., 2010). Simulations and exercises can also be incorporated into a larger research study as a means of evaluating improvements in partnerships and coordination over time as a result of an intervention focused on CBP engagement (Chandra et al., 2015). Pragmatic trial designs whereby whole communities can be randomized (discussed further in Chapter 8) are well suited to evaluating practices in real-world settings and are feasible to execute for preparedness phase interventions. For example, trials with a stepped-wedge design are increasingly used in the evaluation of community-level service delivery and policy interventions (Hemming et al., 2015). In this design, all clusters (e.g., communities) are initially observed in the control condition. In subsequent phases, some are randomly assigned to the intervention until finally all are observed in the intervention condition. While appropriate statistical methods are needed to adjust for the confounding effect of time, this design permits evaluation of each community under both experimental conditions, providing increased statistical power. Importantly, such trials allow for the kind of participatory approach that is valued by communities while meeting the need for robust evaluation, ideally moving the field away from weaker pre-post designs.

The COVID-19 pandemic that emerged in the course of the committee’s work has provided yet another disturbing example of the disproportionate morbidity and mortality observed during and after public health emergencies in those populations that already face health disparities in everyday circumstances. While data are still being collected, early evidence suggests that ethnic and racial minority populations in particular are overrepresented in hospitalizations related to COVID-19 (CDC, 2020). While such disparities are certainly not unique to COVID-19, they underscore how the lack of evidence on equity-related outcomes observed in the committee’s review represents a critical knowledge gap that future research should seek to address. Going forward, the application of critical race theory methods (Ford and Airhihenbuwa, 2010)—which are grounded in social justice—to the design and execution of research may increase understanding of racial and ethnic disparities associated with disasters and public health emergencies and opportunities to address them. The PROGRESS (place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language, occupation, gender/sex, religion, education, socioeconomic status, and social capital) framework is a tool that may facilitate the application of an equity lens to the conduct and reporting of research focused on improving outcomes for at-risk populations after disasters and public health emergencies (O’Neill et al., 2014). As additional research on interventions focused on improving outcomes for at-risk populations is published, it may be helpful to undertake future systematic reviews with an explicit equity focus (Welch et al., 2016).

The COVID-19 pandemic is also challenging some long-standing assumptions based on the more common geological and meteorological hazards that have been the focus of preparedness and response efforts. It has generally been held that the kinds of structural vulnerabilities that put populations at risk cannot be addressed in the midst of a public health emergency. However, a protracted emergency like the current pandemic may illuminate the conditions of vulnerability, such as lack of health insurance or inadequate job site protections, and may provide unique opportunities to address those conditions through, for example, legislation or programs targeting socioeconomic risk factors. It is conceivable that CBPs could be mediators of such efforts, and given the absence of studies identified for this

review examining the effectiveness of interventions that leverage CBPs during a public health emergency, careful consideration of potential methods for measuring the impact of any such interventions that may be implemented in response to COVID-19 is warranted.

REFERENCES

References marked with an asterisk (*) are formally included in the mixed-method review. The full reference list of articles included in the mixed-method review can be found in Appendix B1.

Adams, R. M., B. Karlin, D. P. Eisenman, J. Blakley, and D. Glik. 2017. Who participates in the great shakeout? Why audience segmentation is the future of disaster preparedness campaigns. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14(11).

*Andrulis, D. P., N. J. Siddiqui, and J. P. Purtle. 2011. Integrating racially and ethnically diverse communities into planning for disasters: The California experience. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 5(3):227–234.

*Bevc, C. A., M. C. Simon, T. A. Montoya, and J. A. Horney. 2014. Institutional facilitators and barriers to local public health preparedness planning for vulnerable and at-risk populations. Public Health Reports 129(Suppl 4):35–41.

Blumenshine, P., A. Reingold, S. Egerter, R. Mockenhaupt, P. Braveman, and J. Marks. 2008. Pandemic influenza planning in the United States from a health disparities perspective. Emerging Infectious Diseases 14(5):709–715.

Carameli, K. A., D. P. Eisenman, J. Blevins, B. d’Angona, and D. C. Glik. 2013. Planning for chronic disease medications in disaster: Perspectives from patients, physicians, pharmacists, and insurers. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 7(3):257–265.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2015. Planning for an emergency: Strategies for identifying and engaging at-risk groups: A guidance document for emergency managers. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/hsb/disaster/atriskguidance.pdf (accessed March 11, 2020).

CDC. 2018a. Public health emergency preparedness and response capabilities: National standards for state, local, tribal, and territorial public health. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/readiness/00_docs/CDC_PreparednesResponseCapabilities_October2018_Final_508.pdf (accessed March 11, 2020).

CDC. 2018b. Public health workbook—to define, locate, and reach special, vulnerable, and at-risk populations in an emergency. https://emergency.cdc.gov/workbook/pdf/ph_workbookfinal.pdf (accessed March 11, 2020).

CDC. 2020. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1–30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6915e3.htm?s_cid=mm6915e3_w (accessed May 23, 2020).

Chandra, A., M. V. Williams, C. Lopez, J. Tang, D. Eisenman, and A. Magana. 2015. Developing a tabletop exercise to test community resilience: Lessons from the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience Project. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 9(5):484–488.

DHS (U.S. Department of Homeland Security). 2018. Engaging faith-based and community organizations: Planning considerations for emergency managers. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1528736429875-8fa08bed9d957cdc324c2b7f6a92903b/Engaging_Faith-based_and_Community_Organizations.pdf (accessed March 11, 2020).

Edgington, S., D. Canavan, F. Ledger, and R. L. Ersing. 2014. Integrating homeless service providers and clients in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Silver Spring, MD: National Health Care for the Homeless Council.

Eisenman, D. P., C. Wold, C. Setodji, S. Hickey, B. Lee, B. D. Stein, and A. Long. 2004. Will public health’s response to terrorism be fair? Racial/ethnic variations in perceived fairness during a bioterrorist event. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science 2(3).

Eisenman, D. P., K. M. Cordasco, S. Asch, J. F. Golden, and D. Glik. 2007. Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Public Health 97(Suppl 1):S109–S115.

Eisenman, D. P., D. Glik, R. Maranon, L. Gonzales, and S. Asch. 2009. Developing a disaster preparedness campaign targeting low-income Latino immigrants: Focus group results for project PREP. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 20(2):330–345.

Eisenman, D. P., M. V. Williams, D. Glik, A. Long, A. L. Plough, and M. Ong. 2012. The public health disaster trust scale: Validation of a brief measure. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 18(4):E11–E18.

*Eisenman, D. P., A. Bazzano, D. Koniak-Griffin, C. H. Tseng, M. A. Lewis, K. Lamb, and D. Lehrer. 2014. Peer-mentored preparedness (PM-PREP): A new disaster preparedness program for adults living independently in the community. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 52(1):49–59.

Ford, C. L., and C. O. Airhihenbuwa. 2010. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: Toward antiracism praxis. American Journal of Public Health 100:S3–S35.

Fothergill, A., E. G. M. Maestas, and J. D. Darlington. 1999. Race, ethnicity and disasters in the United States: A review of the literature. Disasters 23(2):156–173.

Gibson, M. J., and M. Hayunga. 2006. We can do better: Lessons learned for protecting older persons in disasters. Washington, DC: AARP. https://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/better.pdf (accessed March 11, 2020).

Gin, J. L., R. Saia, A. Dobalian, and D. Kranke. 2016. Disaster preparedness in homeless residential organizations in Los Angeles County: Identifying needs, assessing gaps. Natural Hazards Review 17(1).

Hemming, K., T. P. Haines, P. J. Chilton, A. J. Girling, and R. J. Lilford. 2015. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: Rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 350:h391.

Hernandez, D., D. Chang, C. Hutchinson, E. Hill, A. Almonte, R. Burns, P. Shepard, I. Gonzalez, N. Reissig, and D. Evans. 2018. Public housing on the periphery: Vulnerable residents and depleted resilience reserves post-Hurricane Sandy. Journal of Urban Health 95(5):703–715.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2011. Guidance for integrating culturally diverse communities into planning for and responding to emergencies: A toolkit: Recommendations of the national consensus panel on emergency preparedness and cultural diversity. https://www.aha.org/system/files/content/11/OMHDiversityPreparednesToolkit.pdf (accessed March 11, 2020).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2015. Healthy, resilient, and sustainable communities after disasters: Strategies, opportunities, and planning for recovery. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

*Messias, D. K. H., C. Barrington, and E. Lacy. 2012. Latino social network dynamics and the Hurricane Katrina disaster. Disasters 36(1):101–121.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2020. Implications of the California wildfires for health, communities, and preparedness: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NCD (National Council on Disability). 2005. Saving lives: Including people with disabilites in emergency planning. https://ncd.gov/rawmedia_repository/fd66f11a_8e9a_42e6_907f_a289e54e5f94.pdf (accessed March 11, 2020).

O’Neill, J., H. Tabish, V. Welch, M. Petticrew, K. Pottie, M. Clarke, T. Evans, J. Pardo Pardo, E. Waters, H. White, and P. Tugwell. 2014. Applying an equity lens to interventions: Using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67(1):56–64.

Paige, S., M. Jones, L. D’Ambrosio, W. Taylor, D. Bonne, M. Loehr, and A. Stergachis. 2010. Strengthening community partnerships with local public health through regional pandemic influenza exercises. Public Health Reports 125(3):488–493.

Remien, R. H., L. J. Bauman, J. E. Mantell, B. Tsoi, J. Lopez-Rios, R. Chhabra, A. DiCarlo, D. Watnick, A. Rivera, N. Teitelman, B. Cutler, and P. Warne. 2015. Barriers and facilitators to engagement of vulnerable populations in HIV primary care in New York City. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 69(Suppl 1):S16–S24.

*Rowel, R., P. Sheikhattari, T. M. Barber, and M. Evans-Holland. 2012. Introduction of a guide to enhance risk communication among low-income and minority populations: A grassroots community engagement approach. Health Promotion Practice 13(1):124–132.

Turner, D. S., W. A. Evans, M. Kumlachew, B. Wolshon, V. Dixit, V. P. Sisiopiku, S. Islam, and M. D. Anderson. 2010. Issues, practices, and needs for communicating evacuation information to vulnerable populations. Transportation Research Record 2196(1):159–167.

Welch, V., M. Petticrew, J. Petkovic, D. Moher, E. Waters, H. White, P. Tugwell and the PRISMA-Equity Bellagio group. 2016. Extending the PRISMA statement to equity-focused systematic reviews (PRISMA-E 2012): Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Development Effectiveness 8(2):287–324.

*Wells, K. B., B. F. Springgate, E. Lizaola, F. Jones, and A. Plough. 2013. Community engagement in disaster preparedness and recovery: A tale of two cities—Los Angeles and New Orleans. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 36(3):451–466.

Willis, E., S. Sabnis, C. Hamilton, F. Xiong, K. Coleman, M. Dellinger, M. Watts, R. Cox, J. Harrell, D. Smith, M. Nugent, and P. Simpson. 2016. Improving immunization rates through community-based participatory research: Community health improvement for Milwaukee’s children program. Progress in Community Health Partnerships 10(1):19–30.

This page intentionally left blank.