6

Communicating Public Health Alerts and Guidance with Technical Audiences During a Public Health Emergency

Inclusion of electronic messaging channels (e.g., email) is recommended as part of state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies’ multipronged approach for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences in preparation for and in response to public health emergencies.

The practice should be accompanied by targeted monitoring and evaluation or conducted in the context of research when feasible so as to improve the evidence base for strategies used to communicate public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences.

Finding Statements and Certainty of the Evidence

| •••• High ••• Moderate •• Low • Very Low | ||

| Finding Statement | Certainty | |

| Electronic messaging systems such as email, fax, and text messaging are effective communication channels for increasing technical audiences’ awareness of public health alerts and guidance during a public health emergency | ••• | |

| Electronic messaging systems are effective communication channels for increasing technical audiences’ use of current public health guidance during a public health emergency | • | |

Implementation Guidance

![]() Engage technical audiences in the development of communication plans, protocols, and channels

Engage technical audiences in the development of communication plans, protocols, and channels

![]() Consider contextual factors, such as the level of uncertainty or urgency, cultural preferences, and stakeholders’ technical capabilities in the selection of communication channels

Consider contextual factors, such as the level of uncertainty or urgency, cultural preferences, and stakeholders’ technical capabilities in the selection of communication channels

![]() Establish vetting processes in advance of public health emergencies and coordinate with response partners on messaging to prevent information overload, duplication of effort, and conflicting recommendations

Establish vetting processes in advance of public health emergencies and coordinate with response partners on messaging to prevent information overload, duplication of effort, and conflicting recommendations

![]() Reduce message volume when feasible, and highlight new information and any differences from previous or other existing guidance

Reduce message volume when feasible, and highlight new information and any differences from previous or other existing guidance

![]() Develop distribution lists in advance of public health emergencies, and ensure that contact information is kept up to date

Develop distribution lists in advance of public health emergencies, and ensure that contact information is kept up to date

![]() Consider designating liaisons and institutional points of contact and leverage existing networks (e.g., medical societies and associations) to facilitate broad message dissemination

Consider designating liaisons and institutional points of contact and leverage existing networks (e.g., medical societies and associations) to facilitate broad message dissemination

DESCRIPTION OF THE PRACTICE

Defining the Practice

The committee examined the evidence for different communication channels used to share public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences. It also examined the factors that may mediate the effectiveness of such communications (e.g., engagement of technical audiences in communication plans prior to an incident, frequency of messaging, designated liaisons). Communicating with technical audiences during a public health emergency falls primarily under Capability 6: Information Sharing (IS Capability) in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capabilities: National Standards for State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Public Health (CDC PHEPR Capabilities) (CDC, 2018a). Information sharing is “the ability to conduct multijurisdictional and multidisciplinary exchange of health-related information and situational awareness data among federal, state, local, tribal and territorial levels of government and the private sector” (CDC, 2018a, p. 62). The IS Capability and the more specific practices for communicating alerts and guidance with technical audiences are closely linked to other CDC PHEPR Capabilities (see Box 6-1). In particular, the IS Capability is closely related to but distinct from the Emergency Public Information and Warning Capability, which is focused on dissemination of information, alerts, warnings, and notifications to the public. Channels and approaches for communicating with the public, while a critically important aspect of communication during response to a public health emergency, were not within the scope of this review. Elements of effective emergency risk communication with the public were the focus of a recent World Health Organization mixed-method systematic review (WHO, 2018). It should be noted that many of the broad principles of good emergency risk communication (related to, for example, time sensitivity and credibility) are applicable across different audience types and scenarios (CDC, 2018b).

Technical audiences for the purpose of this review include those response partners (governmental and nongovernmental) to whom a public health agency communicates public health alerts and guidance in preparation for and response to public health emergencies. Technical audiences may include multijurisdictional and multidisciplinary partners and stakeholders (see Table 6-1). Alerts and guidance may be disseminated by public health agencies at all levels—federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial. Public health alerts are time-sensitive communications that notify technical audiences of and provide updated status on public health threats (e.g., infectious disease outbreaks). Alerts may convey information requiring immediate action, action in the near future, or no action. Public health guidance specifies actions that should or should not be taken (or considered) in response to a public health threat (e.g., information on diagnostic testing methods, directions for submitting confirmed cases, information on use of personal protective equipment) (CDC, 2018a).

Communication channels (see Table 6-1) may allow only unidirectional reporting of information from public health agencies to technical audiences or may facilitate bidirectional exchange (e.g., dissemination of alerts and/or guidance and receipt of reports from technical audiences). The committee considered unidirectional reporting of information (disease cases or adverse events) to public health agencies to be a public health surveillance activity and did not include it in the scope of this review. However, the review did encompass communication channels that facilitate the bidirectional exchange of information if public health agencies may use the information shared by technical audiences to inform future guidance and alerts.

| Technical Audiences | Communication Channels |

|---|---|

|

|

NOTE: These lists are not intended to be comprehensive but to capture the technical audiences and communication channels reported in the studies examined for this review.

Scope of the Problem Addressed by the Practice

Emergencies require exchanging large amounts of information at a rapid pace with multiple stakeholders, often using multiple modes of communication. The rapidly evolving nature of many emergencies and significant uncertainty are critical factors that contribute to changing information and specific challenges in communication with technical audiences (CDC, 2018b). The success of the public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) system relies on the effective communication of information both horizontally across involved organizations and individuals who make up a complex network of response partners and vertically from the federal level down to the regional, state, and local levels. Challenges related to communication with response partners are commonly noted in after action reports (AARs) (Savoia et al., 2012). In an analysis of 31 AARs that addressed information sharing, Savoia and colleagues (2012) note the following themes:

- difficulty sharing information with external partners, often resulting from exclusion of key partners, such as health care and schools, from communication networks, as well as challenges with communication systems and inconsistency of messages;

- difficulty sharing information across different internal groups;

- lack of training in the use of communication technology (e.g., Health Alert Network [HAN], WebEOC, conference call or radio systems); and

- difficulty tracking information in the face of rapidly changing information, lengthy situational reports, and frequent and redundant alerts resulting in information overload.

Public health agencies are often well positioned to notify technical audiences regarding public health emergencies. Clinicians and other stakeholders also rely on public health authorities for guidance on the detection and management of infectious agents and other public health threats. During the H1N1 epidemic, for example, public health guidance informed the use of personal protective equipment, diagnostic testing, and antiviral therapies (Staes et al., 2011). In this context, public health agencies must collect and analyze information and share it with technical audiences during public health emergencies to support decision making and to mitigate health threats (e.g., disease and injury). A notable challenge, however, is ensuring that stakeholders have clear and up-to-date information, particularly in the face of public health guidance that changes as new information becomes available during response (Staes et al., 2011). Moreover, technical audiences may seek and/or receive information from different sources, and inconsistencies across sources can lead to confusion and potentially inappropriate actions by the recipients. In the absence of clear and consistent messaging from public health authorities, technical audiences may obtain and use information from the media or other unreliable sources, which may be inaccurate or out of date.

A wide variety of communication channels are commonly used to disseminate public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences (Revere et al., 2011), and more channels are becoming available as technology continues to evolve at a rapid pace, bringing both opportunities and challenges. In recent years, for example, use of social media during disasters has become both a valuable tool in information sharing and a difficult information-management challenge (Merchant et al., 2011). Facing an ever-growing menu of options for information-sharing vehicles, some of which represent significant resource investments, public health agencies have had little evidence-based guidance to support them in selecting communication channels and strategies. For example, a systematic review by Revere and colleagues (2011) identifies 25 different systems for communicating public health alerts and guidance to health care providers but notes a paucity of rigorous scientific evaluations of

their effectiveness. Ongoing assessment of both traditional technologies and innovations is needed to ensure that public health authorities have the tools and knowledge they need to ensure that urgent public health information reaches target audiences and can be translated into action during public health emergencies. The review described in this chapter builds and expands on the Revere et al. (2011) systematic review.

OVERVIEW OF THE KEY REVIEW QUESTIONS AND ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK

Defining the Key Review Questions

The overarching question that guided this review addresses the effectiveness of different channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency. To answer this question, the committee sought evidence on several sub-questions related to documented benefits and harms associated with the channels themselves, as well as the engagement of technical audiences in the development of communication plans and channels. The committee also examined the evidence on the factors that create barriers to and facilitators of effective communication with technical audiences (see Box 6-2).

Analytic Framework

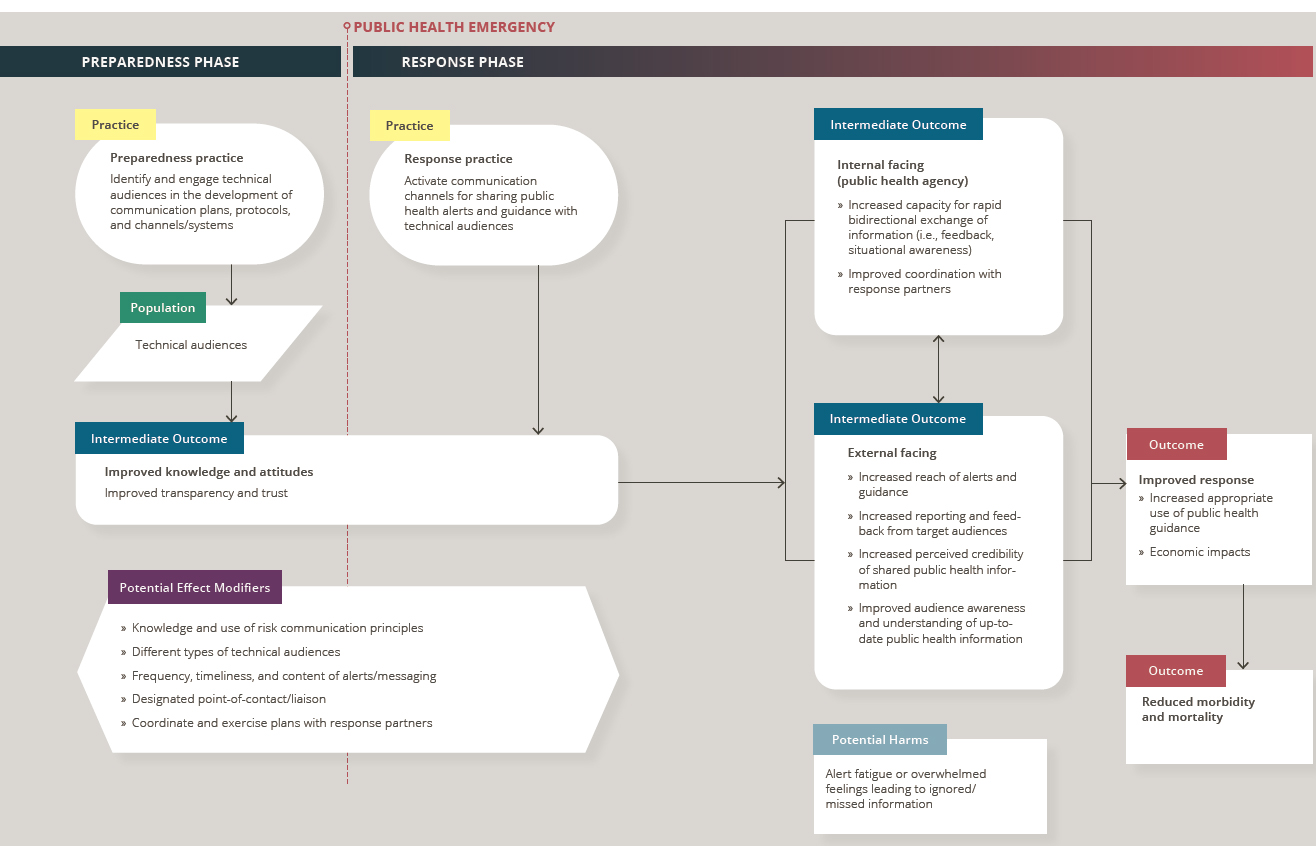

For the purposes of this review, the committee developed an analytic framework to present the causal pathway and interactions between the activation of communication channels during a public health emergency and outcomes of interest (see Figure 6-1). Effective communication channels provide a conduit for the transmission of information from public health authorities to recipient technical audiences (and in some cases, allow for bidirectional exchange). The objective of such information-sharing processes is to ensure that technical audiences are aware of and understand up-to-date information about a particular public health threat. Awareness of current alerts and guidance may influence the behaviors of information recipients (e.g., changes in diagnostic testing protocols, use of personal protective

| BOX 6-2 | KEY REVIEW QUESTIONS |

What is the effectiveness of different channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency (e.g., Health Alert Network, conference calls, bidirectional text-based messaging/SMS, provider access line, email, website, written guidance documents)?

- What are the benefits and harms of engaging technical audiences in the development of communication plans, protocols, and channels?

- What benefits and harms (desirable and/or undesirable impacts) of different communication channels have been described or measured?

- What are the barriers to and facilitators of effective communication with technical audiences?

NOTES: Arrows in the framework indicate hypothesized causal pathways between interventions and outcomes. Double-headed arrows indicate feedback loops.

equipment, case reporting), which may in turn improve the response to a public health threat (e.g., through improved situational awareness and coordination of response partners) and reduce associated morbidity and mortality (e.g., by reducing or better managing infections).

Communication can be categorized as either active (push type) or passive (pull type). Active communication approaches seek to draw the attention of the target audience(s) to information being shared (e.g., emails, alerts embedded in electronic health records), whereas passive mechanisms (e.g., websites) rely on information-seeking behavior among the target audience(s). Understanding the needs and behaviors of the target audience(s) is necessary to combine active and passive approaches effectively. Defining key target audiences and a means of reaching them (e.g., contact information, alert system) in advance of a public health emergency enables more timely information dissemination.

OVERVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION1

This section provides a summary of the evidence from the mixed-method review examining different channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency. Following the summary of the evidence of effectiveness, summaries are presented for each element of the Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework (encompassing balance of benefits and harms, acceptability and preferences, feasibility and PHEPR system considerations, resource and economic considerations, equity, and ethical considerations), which the committee considered in formulating its practice recommendation. Full details on the review strategy and findings can be found in the appendixes: Appendix A provides a detailed description of the study eligibility criteria, search strategy, data extraction process, and individual study quality assessment criteria; Appendix B3 provides a full description of the evidence, including the literature search results, evidence profile tables, and EtD framework for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency; and Appendix C links to all the commissioned analyses that informed this review. Table 6-2 shows the types of evidence included in this review.

Effectiveness

Two quantitative comparative studies directly addressed the overarching key question regarding the effectiveness of different channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency. Both studies evaluated types of electronic messaging systems (e.g., email, fax, text messaging) that are used to push information out to target audiences (rather than relying on target audiences to pull down information). (Refer to Section 1, “Determining Evidence of Effect,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

Consistent with the methods described in Chapter 3, in making its final judgment on the evidence of effectiveness for electronic messaging channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency, the committee considered other types of evidence that could inform a determination of what works for whom and in which contexts, ultimately reaching consensus on the certainty of the evidence (COE) for each outcome. Including other forms of evidence beyond quantitative comparative studies is particularly important when assessing evidence in settings where

___________________

1 To enhance readability for an end user audience, this section does not include references. Citations supporting the findings in this section appear in Appendix B3.

| Evidence Typea | Number of Studies (as applicable)b |

|---|---|

| Quantitative comparative | 2 |

| Quantitative noncomparative (postintervention measure only) | 0 |

| Qualitative | 8c |

| Modeling | 0 |

| Descriptive surveys | 8 |

| Case reports | 12d |

| After action reports | 29d |

| Mechanistic | N/A |

| Parallel (systematic reviews) | N/A |

a Evidence types are defined in Chapter 3.

b Note that sibling articles (different results from the same study published in separate articles) are counted as one study in this table. Mixed-method studies may be counted in more than one category.

c Two surveys containing a qualitative analysis of free-text responses were included in the qualitative evidence synthesis. The two studies were not classified as qualitative research studies and are not included in the qualitative study count for this table. As described in Chapter 3, the findings from these sources were extracted and considered separately in the qualitative evidence synthesis to affirm or question those findings from the more complete qualitative studies.

d A sample of case reports and after action reports was prioritized for inclusion in this review based on relevance to the key questions, as described in Chapter 3.

controlled studies are challenging to conduct and/or other forms of quantitative comparative data are difficult to obtain. Descriptive evidence from real-world implementation of practices offers the potential to corroborate research findings or explain differences in outcomes in practice settings, even if it has lesser value for causal inference. Moreover, qualitative studies can complement quantitative studies by providing additional useful evidence to guide real-world decision making, because well-conducted qualitative studies produce deep and rich understandings of how interventions are implemented, delivered, and experienced. Other forms of evidence considered for evaluation of effectiveness included findings from surveys, case reports, and AARs that involved a real disaster or public health emergency.

The evidence suggests that electronic messaging systems are effective channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences. There is moderate COE supported by two quantitative studies that such electronic messaging systems as email, fax, and text messaging are effective communication channels for increasing technical audiences’ awareness of public health alerts and guidance during a public health emergency. However, these effects may be dampened by alert fatigue associated with excessive message volume. Additionally, awareness of alerts and guidance does not necessarily translate to behavior change. There is very low COE based on a single quantitative study that electronic messaging systems are effective for increasing technical audiences’ use of current public health guidance during a public health emergency. The committee concluded that there is evidence that different technologies used as electronic messaging systems for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency to increase awareness and appropriate use have differing impacts; however, data are insufficient to conclude what technology is best for which audiences in which scenarios.

Of note, some surveys, case reports, and AARs included in this review report on passive electronic messaging systems that rely on information-seeking behavior among the target audience (e.g., websites) and communication channels other than electronic messaging systems (e.g., telephone conferencing, hotlines). In the absence of comparative data from which conclusions about their effectiveness could be drawn, however, these other communication channels were not included in the committee’s synthesis of quantitative evidence. While it is clear that channels other than electronic messaging systems are being used in practice to communicate public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences, the effectiveness of these channels has not yet been rigorously studied in the PHEPR context.

Balance of Benefits and Harms

Although only two quantitative comparative research studies evaluate the effectiveness or benefits of specific channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance, case reports and AARs also cite improved audience awareness and the timeliness of messaging as benefits for some communication channels, such as electronic messaging systems (e.g., fax, email, web-based alerting and surveillance systems), teleconferences, and hotlines. (Evidence source: synthesis of evidence of effect, case report and AAR evidence synthesis.)

Reported harms and undesirable impacts rarely relate to a specific communication channel but arise as a result of how communication is implemented. For example, several evidence sources note the potential for important stakeholders to be left out of the loop if excluded from the systems used to distribute messages (e.g., CDC’s HAN, teleconferences) and/or if contact information is not kept up to date. Also commonly reported as undesirable impacts of public health messaging are alert fatigue and information overload (particularly when guidance is constantly changing), with potential downstream effects of loss of credibility for the public health agency and disillusionment with future preparedness and response efforts. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report and AAR evidence synthesis, evidence from descriptive surveys.) Finally, one study notes that when guidance does not align with what can feasibly be carried out in practice, it may be ignored. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 2, “Balance of Benefits and Harms,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

Acceptability and Preferences

Email and fax have consistently been reported as preferred channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance, although published technology preferences may be outdated given the rapid pace of technology development and adoption. Recent AARs may be useful sources of more current information on preferred communication channels (e.g., webcasts, social media). Technical audiences generally prefer information from local sources (public health or health care institutional sources) or such national authorities as CDC and medical societies. Engaging technical audiences in communication strategies, providing a direct line of communication, offering opportunities for bidirectional exchange, and ensuring information reciprocity (i.e., returning results generated from information submitted by stakeholders to demonstrate the utility and value of the shared information) may improve the acceptability of and responsiveness to messaging. Tailoring guidance to specific audiences, sending just-in-time guidance, and ensuring that guidance is congruent with practice and allows sufficient flexibility in implementation may help enable the translation of information to appropriate action. (Evidence source: quantitative study evidence, qualitative evidence synthesis, case report and AAR evidence synthesis, evidence from descriptive surveys. Refer to Section 3, “Acceptability and Preferences,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

Feasibility and PHEPR System Considerations

Some communication channels are more feasible than others for public health agencies and technical audiences to implement. The widespread use of traditional channels (e.g., email, fax, phone calls) indicates their feasibility, but further research is needed on the acceptability and feasibility of newer channels (e.g., health information exchange–based and electronic health record–based alerting, purpose-built bidirectional surveillance and alert systems). For example, while advances in information technology may lead the public health system to examine and adopt new communication channels, the adoption of these new channels may raise concerns about adding to the burden of message volume and about the availability of needed resources, such as personal or work devices, and technical support. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 4, “Feasibility and PHEPR System Considerations,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

Resource and Economic Considerations

Resource requirements for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences include both technology costs (e.g., phones, radios, computers, servers, software platforms) and human resources. Little research has examined the cost-effectiveness of different communication channels. Many public health agencies and technical audiences already have the technology necessary for traditional communication methods, such as email and conference calls. The initial costs for some purpose-built systems may exceed tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars, which does not include ongoing maintenance costs. However, such systems often have multiple functions of value to public health agencies, including situational awareness and surveillance. Moreover, the indirect costs of new technologies related to training and technical support need to be added to the direct costs. Designated liaisons and communication networks may help amplify messaging and build or maintain trusted relationships, but the human resource costs of these strategies need to be considered. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 5, “Resource and Economic Considerations,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

Equity

Equity issues associated with different channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences are rarely raised in research studies and evaluations (e.g., AARs), and represent an important evaluation gap. One such issue is access to technology, which may be a consideration with respect to rural and underserved populations. Improving relationships with technical audiences that serve disadvantaged populations could lead to more targeted and tailored information sharing during a public health emergency, which in turn could help address equity issues. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 6, “Equity,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

Ethical Considerations

In addition to the equity concerns noted above, which are often viewed as reflecting ethical values, the primary value of communication using appropriate channels is often

considered to be instrumental, meaning that it is important because using appropriate channels to convey information presumably leads to better information delivery, which in turn can facilitate better decision making. In the language of ethical principles, communication using appropriate channels is important because it promotes the principle of harm reduction/benefit promotion. But problems of overcommunication (such as information overload or alert fatigue) can also occur when appropriate communication channels are used, problems that can lead to worse or delayed decisions. In addition, communication using appropriate channels has intrinsic value; that is, setting aside whether decision making is improved by better information delivery, communicating with individuals and communities in ways that are most effective for them is important to achieve transparency, which reflects the principle of respect for persons and communities. As in considering the instrumental value of using more effective channels for communication, one should remember that while communication using ineffective channels is obviously disrespectful, overloading effective communication channels is also disrespectful during crises when recipients have limited time and bandwidth. In sum, selecting appropriate communication channels is ethically important, and so is careful selection of the information to be delivered over those channels. (Evidence source: committee discussion drawing on key ethics and policy texts. Refer to Section 7, “Ethical Considerations,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

The following considerations for implementation are drawn from the synthesis of qualitative research studies, the synthesis of case reports and AARs, and evidence from descriptive surveys, the findings of which are presented in Appendix B3. Note that this is not an exhaustive list of considerations, and that it is important to consult additional implementation resources before implementing the practice recommendation.

Engaging Technical Audiences in the Development of Communication Plans, Protocols, and Channels

The act and process of engaging technical audiences prior to public health emergencies supports relationship building that enhances trust and facilitates understanding of institutional needs, sharing of expertise, coordination among response partners, and enhanced situational awareness. It also allows for the identification of designated points of contact that support direct lines of communication. For the development of new communication channels, a bottom-up approach to identification of system requirements may help ensure that the channel is accepted and meets stakeholder needs. Engaging technical audiences in the development of communication plans and channels also appears to help in the dissemination of public health guidance and may improve the usefulness of such guidance through advance consideration of how the guidance will be translated into actionable knowledge. Conversely, insufficient engagement of partners in planning processes may impede effective communication during emergency responses as a result of planning gaps and unclear communication channels and vetting processes, potentially raising questions about the credibility of public health information. Beyond engaging technical audiences in advance of an emergency, public health communication strategies may also be improved by soliciting real-time feedback during a public health emergency to better meet stakeholder needs. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report and AAR evidence synthesis, evidence from descriptive surveys. Refer to Section 8, “Engaging Technical Audiences in the Development of Communication Plans, Protocols, and Channels,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

Considerations for Selection of Communication Channels

Although few studies evaluate the effectiveness of different communication channels, several provide information on considerations that might inform the selection of channels based on contextual factors, such as the level of uncertainty or urgency. Table 6-3 summarizes considerations discussed in the qualitative studies that may inform the use of different channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences, although it should not be considered an exhaustive list of considerations or communication channels.

Multipronged approaches featuring simultaneous or sequential use of multiple communication channels are commonly reported and may facilitate effective communication when

TABLE 6-3 Considerations for Selection of Communication Channels

| Face to Face | Direct contact through in-person meetings is synchronous (i.e., allows real-time exchange of information), which allows for degrees of nuance and flexibility related to the uptake and understanding of public health guidance. In-person meetings between public health personnel and clinicians are useful, especially when there is perceived anxiety or discomfort about particular guidance. |

| Phone Calls | Direct contact through phone calls and teleconferences is also synchronous and is helpful for very urgent communication. Conference calls allow for collaborative, cross-agency decision making. In one example, the use of two-tiered conference calls (a triage call followed by a coordination call) expedited specific decision making for coordinated patient care decisions. |

| Despite its limitations and regardless of situational context (emergency versus nonurgent) and message recipients (target audience[s]), email is a favored modality for receiving public health messages and has been reported as a timely way to convey information to clinicians. This is a push-type channel, generally used in the one-way delivery of alerts and guidance to target audiences. Effective email-based dissemination of alerts and guidance during a public health emergency relies on an established listserv, prepared in advance. Communication failures may result when key people are not on the list and/or the list has not been maintained with up-to-date contact information. | |

| Fax | Fax has often been used in tandem with email. Faxes still may arrive when phone calls cannot connect. |

| Internet/Websites/Social Media | Websites rely on information-seeking behavior among technical audiences (a pull-type channel). In one study, providers were as likely to seek information from Google as from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increasingly, health care providers and community-based organizations (and to some degree public health agencies) are using social media as a communication channel. |

| Text Messaging/SMS | Text messaging provides rapid, in-the-field short messages, probably helpful in emergencies but not for mass communications. When information is lengthy, email appears to be better suited and preferred. Texts may also include hyperlinks to additional information to overcome the space limitation. Both public health agencies and their stakeholders note multiple values and uses as well as concerns regarding two-way public health text messaging. Use of texts may facilitate communication, for example, by readily providing “eyes on the ground” reports, short polls, and postdisaster check-in of status and availability. It also is an alternative when phone lines are out of service. Conversely, there are concerns with text messaging, including the receipt of text messages on personal phones, restrictive screen space, limited cell coverage, security, and the inability to forward messages. Texts also are not persistent and are easy to ignore. Whether mobile phones are sufficiently made available or supported by workplaces appears to be understudied. |

| Electronic Health Records | Use of electronic health records may enable public health guidance to arrive directly to the point of individual care. However, many issues—related to technology, resources, and compatibility with emergency guidance—would need to be considered and managed before effective implementation could occur. |

adequate attention is paid to contextual dynamics (e.g., needs related to access, accuracy, coordination, reciprocity, and timeliness). The choice of a specific communication strategy needs to balance message content (emergency versus routine communications), delivery (one- versus two-way), and channel (e.g., text, email) with stakeholder preferences and technical capabilities while also mitigating the risk of message overload. The decision to use bidirectional communication strategies is complex and needs to be based on consideration of the balance of benefits (e.g., ability to receive confirmation of message receipt and information from recipients for purposes of surveillance or surge capacity awareness) and such concerns as burden; management; technology requirements; and considerations related to privacy, security, or the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act2 when health-related information is transmitted to public health agencies. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 9, “Considerations for Selection of Communication Channels,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

Facilitating Communication with Technical Audiences During a Public Health Emergency

A recurring theme within and across different evidence sources is the challenge posed by the dynamic information environment characteristic of response scenarios. Rapidly changing conditions during response often necessitate repeated messaging to disseminate updated guidance and other public health information. Technical audiences may have difficulty tracking the most current guidance, and additional confusion and frustration may result from inconsistencies in guidance disseminated by different sources (e.g., national, state, local, institutional). Efforts to ensure clearer and more coordinated messaging can help prevent information overload, duplication of effort, and conflicting recommendations. For example, reviewing and comparing multiple guidance notifications for discrepancies is too time-consuming for technical audiences during response, so new information and differences in guidance (e.g., between that from local public health agencies and CDC or that from health care institutions and public health agencies) need to be clearly noted and explained. Including executive summaries at the beginning of informational emails and other sources may be another way to quickly highlight new, important information for technical audiences. In addition, vetting processes for the review of alerts and guidance and their distribution to appropriate target audiences need to be formally documented and shared prior to a public health emergency to minimize confusion over roles and responsibilities. Given the urgency of disseminating updated information, simplified review protocols and easily customizable alerting frameworks are essential for providing timely decision support to technical audiences.

Effective communication of alerts and guidance is dependent on access to communication platforms and contact information for target audiences. A lack of preexisting, accurate, and up-to-date distribution lists can hinder the reach and timeliness of public health guidance. Standard distribution lists with multiple types of individual contact information (e.g., cell phone, email) need to be developed and maintained for health care providers, local health departments, executive leadership, and response managers. Determining in advance which communications will need to be sent to each stakeholder based on that stakeholder’s information needs and developing an automated system for delivery can ensure that targeted audiences receive the appropriate information. Maintaining these lists and systems as part of

___________________

2 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, HR 3103. Public Law 104-901, 104th Cong. (August 21, 1996).

routine preparedness activities can save valuable time during responses. Another commonly reported barrier is a lack of access to common communication platforms, such as WebEOC, across the local, state, and regional levels, and establishing these links can facilitate vertical communication. There are also cases in which communication systems fail because of either technical issues or power outages. Therefore, redundant systems are critical to ensure that technical audiences receive alerts and guidance in a timely manner.

In addition to technological systems, designated individuals and established networks can facilitate message dissemination and coordination, and in some cases may help ensure that guidance is consistent with practice. These message amplifiers might include designated public information officers (who might also be responsible for communicating information to the general public), liaisons, and institutional points of contact. These individuals may be well positioned to reach contacts in target audience institutions and to facilitate bidirectional information sharing. Although existing networks and coalitions may also enhance the dissemination of public health messages, they can be time intensive to maintain. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report and AAR evidence synthesis, evidence from descriptive surveys. Refer to Section 10, “Barriers and Facilitators to Communicating Alerts and Guidance During a Public Health Emergency,” in Appendix B3 for additional detail.)

A number of other strategies that may facilitate dissemination of public health information to technical audiences are discussed in individual case reports, AARs, and surveys captured in this review. The following list of these strategies, although potentially of use to public health stakeholders, should not be viewed as exhaustive, and additional evidence is needed before these strategies can be recommended as evidence-based practices:

- posting webinar highlights on relevant websites;

- sharing meeting notes after conference calls;

- leveraging media and social media to amplify message dissemination;

- routing notifications regarding public health alerts and guidance through medical societies and institutional (e.g., health care institution) communication channels; and

- disseminating talking points as an attachment to notifications so recipients can pass information along to others in their institution during in-person meetings.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION, JUSTIFICATION, AND IMPLEMENTATION GUIDANCE

Practice Recommendation

Inclusion of electronic messaging channels (e.g., email) is recommended as part of state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies’ multipronged approach for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences in preparation for and in response to public health emergencies. The practice should be accompanied by targeted monitoring and evaluation or conducted in the context of research when feasible so as to improve the evidence base for strategies used to communicate public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences.

Justification for the Recommendation

The practice recommendation is based on moderate-quality evidence that electronic messaging systems are effective in increasing technical audiences’ awareness of public health alerts and guidance, and substantial evidence from other sources indicating that technical audiences prefer to receive alerts and guidance through electronic messaging channels, such as email. The evidence suggests that different technologies employed as electronic messaging systems for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency to increase awareness and use of appropriate guidance have differing impacts. However, the available data are insufficient to support a conclusion as to what technology is best for which audiences in which scenarios. Stakeholder preferences need to be monitored continuously as technology continues to evolve. The vast majority of the evidence relates to stakeholders from the health care field in the context of a disease epidemic, raising questions about the applicability of the evidence to other technical audiences and settings. No studies examine the communication needs or processes of tribal or territorial public health agencies. Further research and/or evaluation is needed to address these evidence gaps.

Implementation Guidance

- Engage technical audiences in the development of communication plans, protocols, and channels.

- Consider contextual factors, such as the level of uncertainty or urgency, cultural preferences, and stakeholders’ technical capabilities, in the selection of communication channels.

- Establish vetting processes in advance of public health emergencies and coordinate with response partners on messaging to prevent information overload, duplication of effort, and conflicting recommendations.

- Reduce message volume when feasible, and highlight new information and any differences from previous or other existing guidance.

- Develop distribution lists in advance of public health emergencies, and ensure that contact information is kept up to date.

- Consider designating liaisons and institutional points of contact and leverage existing networks (e.g., medical societies and associations) to facilitate broad message dissemination.

EVIDENCE GAPS AND FUTURE RESEARCH PRIORITIES

Few rigorous evaluations salient to this practice have been published since Revere and colleagues (2011) conducted their systematic review. The committee identified only two quantitative studies that evaluated the effectiveness of channels for communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences: one did not evaluate communication channels during a real public health emergency (Baseman et al., 2016), and the other had serious methodological limitations (van Woerden et al., 2007). Both studies evaluated a subset of electronic messaging system channels (i.e., email, fax, text). Other channels (electronic and nonelectronic) were discussed in case reports, surveys, and AARs, but no quantitative data were available from which conclusions regarding effectiveness could be drawn. More research is needed to generate evidence supporting conclusions regarding which communication channels are most effective for reaching which technical audiences in which settings. Quasi-experimental matched comparison designs have been used to evaluate other kinds of public health practices outside of the emergency context (Rabarison et al., 2015) and could be employed to measure the effectiveness of communication channels used in different locations in a real (or simulated) public health emergency. Such designs, which, for example, could be used to identify agencies that are using communication strategy X and those that are not (or identify agencies that are using strategy X but not Y and those that are using strategy

Y but not X), may be more feasible to conduct in a real public health emergency relative to a randomized controlled trial.

It is important to recognize that there are many important aspects to communication with technical audiences, of which the implementation of communication channels is just one. Beyond a focus on communication channels, research is needed to address the influence of message format (e.g., text, infographic) and content (e.g., length of messages, presentation and/or framing) on the effectiveness of communication strategies for different technical audiences. This research would optimally include an evaluation of the most effective formats and approaches for highlighting new information and guidance as information changes during the course of response to an event. Such research could be informed by targeted monitoring and evaluation (M&E) in practice settings that examined where information was going and who was using it. One such channel that could be a good candidate for targeted M&E is CDC’s HAN. In their review, Revere and colleagues (2011) note very few studies attempting to evaluate whether HAN messages were received and acted on by the intended recipients. Similarly, the committee, in its review, found that only case reports and AARs briefly mentioned HAN. As HAN is a strategy already in widespread use to communicate public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences, future research on HAN could benefit from implementation science methods.

The committee found qualitative studies useful for exploring the social factors, including those that create barriers and facilitators, involved in communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences. However, only eight qualitative research studies met the committee’s inclusion criteria, and of those, only three were directly relevant. The result was a weak basis for the study findings based on synthesized qualitative evidence. However, the study by Khan and colleagues (2017) provided an example of a high-quality qualitative research study exploring in-depth perspectives on effective communication between public health and health care stakeholders. These authors conducted a qualitative study guided by complexity theory to explore current practices, barriers, and facilitators, and to develop a framework for promoting effective communication that could eventually be validated and implemented. A gap identified throughout the corpus of studies was the uncertainty around whether some of the intermediate outcomes examined, such as message receipt and recall, translated to action and behavior change. Khan and colleagues (2017) recognized this issue at the outset of their study. Accordingly, they closely linked their objectives to principles of knowledge translation and knowledge to action (Graham et al., 2006) to ensure that the strategies they described would also be related to a rapid knowledge-to-action cycle. It would be valuable for future efforts to focus on ways of ensuring that evaluators adhere to rigorous protocols for data collection, analysis, and interpretation for qualitative research, as such protocols can be useful in developing the program theory for a potential intervention. This is an especially critical point for such topics as communicating public health alerts and guidance when an important consideration is user preference and access to technology (see Chapter 8 for additional detail regarding methodological improvements).

Technology is continuously evolving, and research studies can quickly become outdated. The body of research studies examined by the committee demonstrated that there is a considerable time gap between the adoption of new communication technologies for use in the field and the publication of research studies evaluating those technologies. For example, although text messaging– and Internet-based technologies (notably social media) have been in use for some time, there is relatively little research looking at their use or effectiveness in PHEPR, indicating an urgent need for more research on these channels. Moreover, as new modalities for communicating alerts and guidance become available, additional research will be needed to assess their effectiveness and their acceptability and feasibility for public

health stakeholders. Given that communication channels are likely to continue to evolve, this topic might be considered for a living systematic review and guideline, which offers a mechanism for continuously updating evidence syntheses and recommendations as new evidence is published (Akl et al., 2017; Elliott et al., 2017).

The vast majority of available evidence related to this practice addresses communication with health care stakeholders during infectious disease epidemics. The committee found limited evidence for other technical audiences or public health emergencies, raising questions about the broad applicability of the existing evidence. The management of Ebola cases in the United States provides a recent example of a situation in which public health agencies needed to communicate with other technical audiences. Specifically, public health agencies had to communicate with hazardous material responders, transportation agencies, and other nontraditional technical audiences to manage potentially contaminated environments (CDC, 2019). Moreover, no studies examine communication channels (simulated or real) with tribal or territorial public health agencies and technical audiences, which the committee believes is a gap in understanding the effectiveness of this practice in these contexts. Future research will need to examine differences in effectiveness and preferences across the range of emergencies, settings, and technical audiences listed earlier in Table 6-1.

REFERENCES

References marked with an asterisk (*) are formally included in the mixed-method review. The full reference list of articles included in the mixed-method review can be found in Appendix B3.

Akl, E. A., J. J. Meerpohl, J. Elliott, L. A. Kahale, H. J. Schünemann, T. Agoritsas, J. Hilton, C. Perron, E. Akl, R. Hodder, et al. 2017. Living systematic reviews: Living guideline recommendations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 91:47–53.

*Baseman, J., D. Revere, I. Painter, M. Oberle, J. Duchin, H. Thiede, R. Nett, D. MacEachern, and A. Stergachis. 2016. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of traditional and mobile public health communications with health care providers. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 10(1):98–107.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2018a. Public health emergency preparedness and response capabilities: National standards for state, local, tribal, and territorial public health. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/readiness/00_docs/CDC_PreparednesResponseCapabilities_OctOcto2018_Final_508.pdf (accessed March 16, 2020).

CDC. 2018b. Crisis and emergency risk communication. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/manual/index.asp (accessed May 9, 2020).

CDC. 2019. Ebola-associated waste management. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/clinicians/cleaning/waste-management.html (accessed Feburary 24, 2020).

Elliott, J., A. Synnot, T. Turner, M. Simmonds, E. Akl, S. McDonald, G. Salanti, J. Meerpohl, H. MacLehose, J. Hilton, I. Shemilt, J. Thomas, T. Agoritsas, R. Hodder, and J. Yepes-Nuñez. 2017. Living systematic review: Introduction: The why, what, when and how. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 91.

Graham, I. D., J. Logan, M. B. Harrison, S. E. Straus, J. Tetroe, W. Caswell, and N. Robinson. 2006. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 26(1):13–24.

*Khan, Y., S. Sanford, D. Sider, K. Moore, G. Garber, E. de Villa, and B. Schwartz. 2017. Effective communication of public health guidance to emergency department clinicians in the setting of emerging incidents: A qualitative study and framework. BMC Health Services Research 17(1).

Merchant, R. M., S. Elmer, and N. Lurie. 2011. Integrating social media into emergency-preparedness efforts. New England Journal of Medicine 365(4):289–291.

Rabarison, K. M., L. Timsina, and G. P. Mays. 2015. Community health assessment and improved public health decision-making: A propensity score matching approach. American Journal of Public Health 105(12):2526–2533.

Revere, D., K. Nelson, H. Thiede, J. Duchin, A. Stergachis, and J. Baseman. 2011. Public health emergency preparedness and response communications with health care providers: A literature review. BMC Public Health 11:337.

Savoia, E., F. Agboola, and P. D. Biddinger. 2012. Use of after action reports (AARs) to promote organizational and systems learning in emergency preparedness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9(8):2949–2963.

*Staes, C. J., A. Wuthrich, P. Gesteland, M. A. Allison, M. Leecaster, J. H. Shakib, M. E. Carter, B. M. Mallin, S. Mottice, R. Rolfs, A. T. Pavia, B. Wallace, A. V. Gundlapalli, M. Samore, and C. L. Byington. 2011. Public health communication with frontline clinicians during the first wave of the 2009 influenza pandemic. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 17(1):36–44.

*van Woerden, H. C., M. R. Evans, B. W. Mason, and L. Nehaul. 2007. Using facsimile cascade to assist case searching during a Q fever outbreak. Epidemiology and Infection 135(5):798–801.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2018. Communicating risk in public health emergencies: A WHO guideline for emergency risk communication (ERC) policy and practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

This page intentionally left blank.