8

Improving and Expanding the Evidence Base for Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response

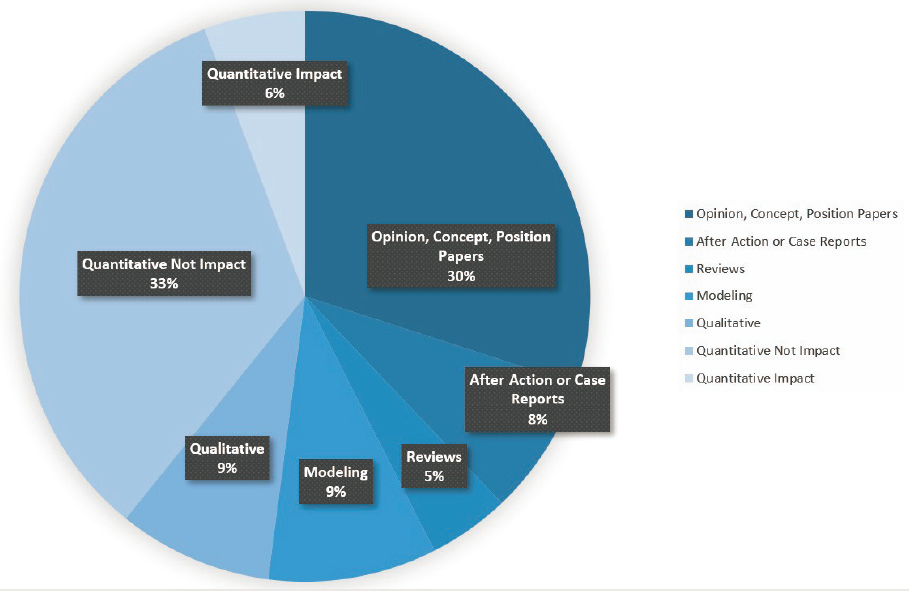

As described in preceding chapters, despite investments in public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) research in the past two decades, the corresponding PHEPR evidence base remains limited (Carbone and Thomas, 2018). Figure 8-1 shows the study design distribution of all articles included in a committee-commissioned scoping review focused on the 15 PHEPR Capabilities (see Chapter 2 and Appendix D for additional detail on the commissioned scoping review). Among the 1,692 articles included, approximately 35 percent were classified as opinion, concept, or position papers or literature reviews, while 65 percent reflected some form of systematic data collection and analysis that could potentially provide evidence regarding 1 of the 15 PHEPR Capabilities. The most common study design category was quantitative nonimpact studies, which accounted for 33 percent of all articles and 51 percent of evidentiary studies. The quantitative nonimpact category includes studies that describe and identify the magnitude, severity, and preventability of a PHEPR problem and could potentially be used to inform the development of PHEPR practices aimed at addressing that problem. The quantitative impact category, accounting for only about 6 percent of all articles, includes studies that evaluate specific PHEPR practices.

This distribution of study designs presents challenges for identifying evidence-based practices, and in Chapter 2, the committee presents the following conclusion:

Conclusion: With the increasing complexity of both public health emergencies and the PHEPR system, policy makers and practitioners have a crucial need for access to guidance based on robust evidence to support their decisions on practices, policies, and programs for saving lives during future public health emergencies. Therefore, a coordinated and comprehensive approach to prioritizing and aligning research efforts and ensuring that research is relevant and consistently connected to practice, along with investments in research infrastructure, is necessary to strengthen the PHEPR evidence base, thereby ensuring that PHEPR practitioners have the scientific evidence they need to guide and inform their actions. At the same time, PHEPR practitioners will require incentives to base their practices, policies, and programs on evidence.

In this chapter, the committee describes a framework to support the systematic development of knowledge in the PHEPR field and sets forth the aspirations for high-quality, rigorous PHEPR research and evaluation.

A NATIONAL PHEPR SCIENCE FRAMEWORK

The generation of a PHEPR evidence base has been hindered by the inherent challenges of conducting research on public health emergencies, which can limit the opportunities to observe and proactively study the effects of practices used to mitigate harm before, during, and after such an event (see Chapter 2 for additional details). In addition to those challenges, federal partners and other stakeholders repeatedly have attempted to enhance PHEPR research capacity. However, many of these efforts have not been sustained or adequately resourced, and the result has been a limited infrastructure to support the generation and dissemination of PHEPR research.

Conclusion: Funding for and prioritization of research before, during, and following public health emergencies are currently fragmented and disorganized, spread across multiple funding agencies, inconsistent, and do not encourage the progression of quality research or the sustainable development of research expertise. This situation has contributed to a field based on long-standing rather than evidence-based practice.

Despite the implications of public health emergencies for the nation’s health and economic security, there is currently no mechanism for ensuring the coordinated resourcing, monitoring, and execution of public- and private-sector PHEPR research.

Key Components of a National PHEPR Science Framework

The importance of developing a disaster research strategy has previously been underscored (Keim et al., 2019). The committee proposes that a comprehensive National PHEPR Science Framework could move the PHEPR field beyond the near-term goal of a research agenda toward a more coherent vision of coordinating and aligning efforts effectively to advance evidence-based practice in PHEPR (see Figure 8-2). The key components of this framework are discussed in the following sections.

System Leadership to Transform the PHEPR Research Enterprise

The foundations of scientific progress in PHEPR lie in building and sustaining a research enterprise. Strong leadership at all levels, but especially at the federal level, is central to the framework and essential to support systems-level change and mobilize agencies to transform the way PHEPR research is coordinated, funded, and conducted. An interagency and multidisciplinary effort led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will be necessary to develop and implement a National PHEPR Science Framework; establish an authority and process for supporting research before, during, and following public health emergencies; and ensure that adequate research funding, capacities, and infrastructure are in place. CDC is the funding agency with the primary mission responsibility in PHEPR, and it is important that the agency responsible for supporting PHEPR planning and implementation also leads efforts to increase the scientific evidence base that supports the execution of that responsibility. However, the committee acknowledges that no one agency can accomplish this transformation of the PHEPR research enterprise, and it will be necessary to leverage the strengths of different partners, including funding partners, in these efforts. Given the complexity of the PHEPR system and the fact that it is nested within many integrated, larger systems (e.g., supply chain, transportation), it will be imperative for this effort to be carried out in cooperation with other fields, industries, and organizations. It will also be essential to provide CDC with adequate resources and expertise to support its lead role in these efforts and to encourage CDC to become a learning organization. Appropriation language will need to be explicit and clear that funding can be used for these research efforts.

An enterprise for coordinating medical countermeasure (MCM) efforts in the federal government could serve as a model for coordinating and funding PHEPR research (HHS, 2017a). The Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise (PHEMCE), established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 2006 and led by the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), has the following core members: the director of CDC, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Key PHEMCE partners include senior leadership from other federal agencies and numerous nonfederal partners. Recognizing that the development of MCMs requires significant resources in terms of time and cost, the PHEMCE helps coordinate funding across portfolios and prioritize efforts through a coherent plan that spans several years (HHS, 2017b). PHEMCE members are motivated and guided by the need to develop responses and cost-efficient methods to protect the nation against novel threats. This enterprise has been successful in bringing attention to the issue of MCM development, generating additional research investment, and prompting government agencies and departments to coordinate their research efforts. Such a coordinated effort can bring common terminology and infrastructure to a fragmented research enterprise.

Recognition of PHEPR Science as a Unique Academic Discipline Within Public Health

PHEPR research is transdisciplinary and draws on the knowledge base from many different fields, from behavioral and social sciences and political science to systems science and operations research, among others. However, recognition that PHEPR science is a unique academic discipline within the broader public health field represents the first step in addressing the substantial need for research; qualified, well-trained researchers; and preexisting, durable, and reliable engagement and partnerships with PHEPR practitioners.

The nuances and complexity of the PHEPR field pose unique challenges for designing research studies that differ from those in the broader public health field (e.g., population health research), and the usual approach for clinical research—randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—is not always feasible. Researching public health emergencies requires specific knowledge and understanding of how the systems involved work, and public health scientists may lack the knowledge, experience, and credibility to conduct research before, during, or following a public health emergency. Given the nuances of PHEPR research, it can be especially important for researchers to be familiar with the strengths and limitations of various approaches to and methods for evaluation. These may include, for example, observational studies designed in real time with strong data collection, predesigned pragmatic trials ready for deployment, simulations and exercises that use RCT approaches, side-by-side qualitative research studies to supplement quantitative methods, and methods for capturing data from after action reports (AARs) in a way that supports knowledge generation.

Recognizing PHEPR science as a unique academic discipline within the broader public health field could generate the resources and efforts needed to better support current and new academic departments or centers focused on PHEPR; establish degree or certification programs; and support career mechanisms that would enhance the conduct of high-quality, rigorous PHEPR research. Training and career development for PHEPR researchers are discussed in greater depth in the section on workforce capacity development for PHEPR research and practitioners later in this chapter. With recognition of PHEPR as a distinct field of study, the PHEPR research community could develop its own unique culture with the support of scientific societies and associations, which currently is lacking.

A Forward-Looking PHEPR Research Agenda and Common Evidence Guidelines

A research agenda is necessary to galvanize the PHEPR research field to meet the needs and respond to the concerns of PHEPR practitioners and society at large (IOM, 2008). This agenda must be more than a simple inventory of research needs (see Box 8-1). It will require leadership, and an organizing entity will need to be identified and made responsible for aggregating research conducted in alignment with the agenda and for tracking progress on and updating the agenda. A component of the agenda could highlight what is and is not known or what PHEPR research is currently under way. PHEPR evidence gaps could, for example, be identified and communicated by the PHEPR evidence-based guidelines group proposed in Chapter 3. Another essential feature of the research agenda will be to describe a process for rapidly identifying and prioritizing research needs during a public health emergency and to establish a minimum set of data elements that would be sought by anyone collecting data during such an event (NBSB, 2011).

A formal research prioritization process will be necessary, including a top-down, bottom-up approach to setting the research agenda. An important consideration is for the process to be inclusive of governmental, nongovernmental, private, and academic organizations, as well as broad public input from practitioners, policy makers, researchers, and the community. Given that outcomes of interest in PHEPR also include process and system improvements (Carbone and Thomas, 2018), it will be valuable to engage in the research agenda development process experts in the fields of health services research; social science; implementation and improvement science; operations research; complex interventions; quality improvement; cost-effectiveness; and systems, policy, and organizational research. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) has conducted a successful town hall model in communities across the country for bringing practitioners, researchers, and community members

together to participate in setting a research agenda, enhance practitioner–researcher partnerships, and foster greater awareness of community and public health needs (O’Fallon et al., 2003). O’Fallon and colleagues (2003) note several best practices for successful town halls:

- the meeting is held in a location that is convenient and comfortable for the participants;

- controversial topics are encouraged, and when such a topic is selected, it is important to ensure that both sides of the issue are presented;

- lecturing is minimized and audience participation is maximized; and

- the final agenda is determined by the host organization.

In addition to town hall models, workshops and leadership retreats for practitioners and researchers can be useful to identify new developments and research topics in PHEPR (O’Fallon et al., 2003).

It will be important for the research agenda to encompass a range of research questions that would be addressed through different methods of inquiry (see the section on common evidence guidelines for PHEPR later in this chapter), including and going beyond the topics covered within CDC’s 15 PHEPR Capabilities. A good starting point for identifying research questions will be to examine previously developed research agendas for PHEPR (Acosta et al., 2009; IOM, 2008). Additional research priorities may be informed by the evidence gaps identified in the committee’s commissioned scoping review (see Appendix D) and the committee’s evidence reviews for practices within the Community Preparedness, Emergency Operations Coordination, Information Sharing, and Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions Capabilities (see the sections on future research priorities in Chapters 4–7).

Meaningful Partnerships Between PHEPR Practitioners and Researchers to Promote Knowledge

Crucial to a National PHEPR Science Framework will be ensuring a strong connection between PHEPR practitioners and researchers, as well as strong community partnerships. Understanding how to promote, improve, and sustain the engagement of PHEPR practitioners and communities in a thoughtful and inclusive process for generating research will be an essential element of a robust and effective PHEPR research field (Miller et al., 2016). With the proper incentives in place, PHEPR practitioners and researchers can be encouraged to engage in more meaningful partnerships to promote knowledge. Academic partners can help public health agencies by providing data and findings to inform practice (especially during a real public health emergency, when public health agencies may be challenged in conducting research), executing studies, facilitating stakeholder meetings, assessing training needs, providing technical assistance, and collaborating on publications (IOM, 2015). Specifying expectations related to the conduct, and subsequent publication, of research and evaluation in practitioner position descriptions, or even designating a dedicated “science” position within the agency, could provide an incentive for collaborating and partnering with researchers. Furthermore, partnerships between PHEPR practitioners and researchers could be strengthened by integrating expectations into Project Public Health Ready (PPHR), a criteria-based training and recognition program that assesses local health departments’ PHEPR capacity, or the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) accreditation process. Additionally, establishing the trust of the community before a public health emergency occurs is critical to ensuring that research can be conducted effectively and equitably. The community also has many resources to offer the PHEPR research enterprise, including its experiences and knowledge of its needs and existing networks that can be leveraged. Overall, PHEPR research requires the collaboration, insight, and trust of professionals from public health, other response agencies, academia, private entities, and members of the community prior to a public health emergency, and an effective National PHEPR Science Framework will support strategies for strengthening and maintaining these partnerships to promote successful PHEPR research. Collaboration and engagement among practitioners, researchers, and the community is a critical element that is highlighted throughout this chapter—from the development of a research agenda and funding of research programs to participation in the design and conduct of the research and translation, dissemination, and implementation of evidence-based practices.

PHEPR Evidence-Based Guidelines Group and Other Efforts to Facilitate the Translation, Dissemination, and Implementation of PHEPR Research

If the PHEPR field is to be grounded in evidence, the translation, dissemination, and implementation of research findings represent a crucial component of a National PHEPR Science Framework. The research and other evidence driven by this framework will need to be translated into clear evidence-based practices for public health agencies through an ongoing evidence review process. Accordingly, it will be important for the PHEPR evidence-based guidelines group proposed in Recommendation 1 in Chapter 3 to be integrated into the activities of the National PHEPR Science Framework, and to review relevant research and distill it into guidelines for the benefit of practitioners.

The use of sustainable strategies and mechanisms, such as training specialists in translation and implementation science, particularly for the PHEPR field, can help bridge the often daunting gap between practice and research (Carbone and Thomas, 2018). Researchers need to engage with potential users of their research, involving them in the research design

and implementation process to increase the likelihood that results will be translatable and practiced (Jillson et al., 2019). At the same time, while practitioners’ perspectives and needs are an important consideration in developing research projects, practitioners also need to be accepting of innovations that emerge from the research community (Carbone and Thomas, 2018). Workforce capacity development programs are necessary to improve the implementation capacity of public health agencies. These issues are explored in depth in the sections on workforce capacity development for PHEPR research and practitioners and on translation of research into practice and dissemination and implementation of evidence-based PHEPR practices later in this chapter.

Ensuring Adequate Infrastructure and Supporting Mechanisms to Facilitate the Conduct of PHEPR Research

To conduct research effectively before, during, and following a public health emergency, additional capacities, infrastructure, policies, and other elements must be strengthened or created. Adequate and sustained federal funding for PHEPR research is necessary to ensure the continual flow of scientific discoveries to mitigate the health impacts of public health emergencies.

Recognizing that this is an applied research field, there needs to be an emphasis on funding mechanisms that facilitate practice-based approaches and support the collection of experiential evidence from real-world practice and public health emergencies. It is imperative to ensure that funded research programs are relevant to practice, and in Chapter 2, the committee concludes that, in addition to investments in research infrastructure, a coordinated and comprehensive approach to prioritizing and aligning research efforts and ensuring that research is relevant and consistently connected to practice is necessary to strengthen the PHEPR evidence base.

The best practitioner-centered evaluations will be achieved through trusting and durable partnerships between practitioners and researchers. Some example practice-based approaches that could be supported include a researcher residency model, a practice-based research network (PBRN) model, and a research-oriented tabletop exercise model. A researcher residency model (i.e., researchers embedded in the PHEPR system) could enable researchers to attend and observe exercises, have a seat in the emergency operations center during a public health emergency, and participate in the after action reporting. In learning health care systems, it has increasingly been recognized that embedding researchers in the system offers multiple benefits, including the identification of practitioner- and systems-relevant research questions and the ability to close the research and practice gap (both of which are persistent challenges in PHEPR) (Forrest et al., 2018). CDC could also consider requiring the inclusion of PHEPR practitioners in research proposals or implementing a PBRN model within PHEPR that might enable important advances in these areas. PBRNs—groups of practitioners and researchers working together to answer community-based questions and translate research findings into practice—are a result of the increasing need for research conducted in real-world settings (AHRQ, 2019; DeVoe et al., 2012; Mays et al., 2013; RWJF and University of Kentucky College of Public Health, 2020). PBRNs have previously been supported in public health (such a program was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation [RWJF] from approximately 2007 to 2015) (RWJF, 2013), and some of this work focused on PHEPR (CTEC, 2016; Wimsatt, 2017). Additionally, research-oriented tabletop exercises can aid in developing practice-driven research. For example, Chandra and colleagues (2015) developed a community resilience tabletop exercise and administered it to stakeholders from multiple disciplines to assess progress in community resilience and provide an opportunity for quality

improvement and capacity building. The NIEHS Disaster Research Response (DR2) program has previously conducted regional tabletop exercises for researchers and practitioners to facilitate the development of these partnerships and to educate practitioners on ways of incorporating data collection and research into disaster response (NIH, 2019b). Attention to emerging practice-based approaches is needed as well.

An equally important aspect of funding is mechanisms that allow for investigator-driven research, facilitate engagement and collaboration with researchers from different disciplines, and encourage the progression from development to intervention to secondary analysis to center grants—something that is currently lacking in the PHEPR field but is fundamental to any research enterprise. Several models for sustained funding programs for research series and multidisciplinary and collaborative research centers, as well research education and training projects (i.e., career development grants), currently exist at the National Science Foundation (NSF) and NIH and could be replicated for the PHEPR field (NIH, 2019c, 2020a; NSF, 2020b). CDC currently funds research through the use of grants and cooperative agreements (CDC, 2020b). Foundations, such as RWJF, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Open Philanthropy Project, among others, can support research programs when federal support is limited (Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, 2020; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, 2020; Open Philanthropy, 2020; RWJF, 2020a).

Addressing PHEPR knowledge gaps will require sustained lines of research, with multiple studies addressing similar research questions in different contexts and populations in nonemergency times and with the ability to refocus efforts or activate additional protocols, if warranted, in the event of a future public health emergency. Given the inherent challenges of conducting research during public health emergencies, it is important to give careful consideration to opportunities for advancing PHEPR science during nonemergency times and to the pre-event planning needed to enable research during and following future public health emergencies. Types of PHEPR research that could be supported in nondisaster times include modeling, simulations and exercises, and research on public health implementation issues that would likely translate in the event of a public health emergency. One of the challenging aspects of all PHEPR activities, including research, is the natural aversion to creating unused capacity. A solution to this challenge could be providing funding and resources for individuals conducting research in nonemergency times with the expectation—and support—that they will turn their attention to researching a public health emergency at hand. Research funders could consider requiring researchers to account for this possibility by describing such contingency processes in their proposals.

As mentioned above, deliberative planning during nonemergency times is necessary so that the resources and supporting mechanisms needed to rapidly conduct scientific research in the context of a public health emergency will be in place. Past efforts have made strides toward developing mechanisms to support scientific research in the context of a public health emergency, some of which have indeed been developed and even tested (e.g., rapid identification and prioritization of research needs and funding after Hurricane Sandy) (Lurie et al., 2013). In Table 8-1, Lurie and colleagues (2013) describe key components of an integrated approach to research before, during, and after an emergency and explicitly lay out actions that could be taken before as well as during the emergency. One consideration not included in this table is the action of developing metrics and outcome measures, an important component of the conduct of research and evaluation of practices. Future efforts to ensure adequate infrastructure and supporting mechanisms to facilitate the conduct of research during public health emergencies could be guided and informed by these past efforts.

To support research during a public health emergency, sustainable, rapid, and nimble funding mechanisms, together with award criteria and preapproved PHEPR research study

TABLE 8-1 Key Components of Research Response in the Context of Public Health Emergencies

| Component | Actions Before the Event | Actions During the Event |

|---|---|---|

| Identify questions that will need to be addressed for common scenarios and develop generic study protocols |

Identify experts in research design and in key topic areas

Develop and gain approval from institutional review boards for key study protocols |

Convene experts, and review and amend protocols as needed |

| Ensure that appropriate cadres of scientists are available to respond to events |

Roster experts in research design and in topical areas of concern

Develop an on-call research “ready reserve” of clinicians, scientists, and other experts in government, academia, and industry |

Convene experts (and potentially others with concerns) to identify areas for priority research |

| Develop a process for activating research response |

Incorporate the concept of an “incident commander for research” into response plans

Determine criteria for activation of research response |

Identify an “incident commander for research” and representatives from relevant science agencies that will be charged with supporting and conducting research

Notify prerostered experts |

| Identify and prioritize research needs | Identify potential knowledge gaps and research questions | Convene experts and others, such as those in affected communities, to review previously identified gaps, identify unforeseen and emerging knowledge gaps, prioritize research and baseline data collection needs, and recommend to researchers and funders which to pursue in the short term |

| Ensure conditions for rapid data collection |

Develop and preapprove generic protocols and survey instruments so that only changes to them require review when the event occurs

Develop protocols for collecting and storing biospecimens |

Modifying preexisting survey and other data collection tools for event-specific conditions |

| Ensure rapid and appropriate human subjects review |

Establish a Public Health Emergency Research Review Board

Promote a commitment to expedite review by grantee institutions and prepositioned research networks |

Facilitate rapid review of protocols by national or local institutional review boards |

| Ensure mechanisms for rapid funding |

Use prefunded research networks and preawarded but just-in-time funded research contracts

Incorporate research response to public health emergencies in specific aims on grant awards to better facilitate administrative supplements Identify nongovernmental funders, both regionally and by sector, with an interest in addressing knowledge gaps |

Convene potential governmental and nongovernmental funders

Share prioritized research agenda |

| Component | Actions Before the Event | Actions During the Event |

|---|---|---|

| Ensure that response workers and other exposed persons are identified and rostered |

Develop and use a Rapid Response Registry

Identify potential monitoring and tracking devices to facilitate exposure monitoring (e.g., among emergency responders) |

Activate registry enrollment and designated data collection networks, including for biospecimens, when appropriate

Deploy monitoring and tracking devices, when appropriate |

| Understand concerns of affected communities | Identify a generic list of concerns to address, drawing on community-based participatory research and experience with previous events |

Engage community representatives in discussion of concerns and potential studies

Ensure mechanisms to share findings with the community |

SOURCE: Lurie et al., 2013. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

protocols, are needed. Several such mechanisms currently exist, but they are uncoordinated and focused disproportionately on infrastructure, engineering, and environmental health. An example is NSF’s Rapid Response Researich funding mechanism, used when quick-response research on disasters is needed (NSF, 2018). Additionally, with the support of NSF, the National Hazards Center at the University of Colorado administers a Quick Response Research Grant Program that provides small grants to help researchers collect data following an event (National Hazards Center, 2019). This program can be mobilized quickly to put some of the necessary research infrastructure in place in the immediate aftermath of a disaster and could serve as a model for funders, although it is at a smaller scale than that needed for the PHEPR research enterprise. NIEHS’s Time-Sensitive Research Grants Program is another example of a rapid funding mechanism for public health emergencies. Its aim is to receive, review, and fund research applications within 90–120 days, and it supports research to characterize initial exposures, collect human biological samples, and collect human health and exposure data (Miller et al., 2016). Other agencies could replicate these rapid response funding models specifically for PHEPR research. Additionally, partnerships with foundations that are interested in addressing the needs of communities and health-related research could help fill gaps in funding.

Rapid funding to support research in the event of a public health emergency is not enough, however; efforts are also needed to enhance capacities to conduct the research and improve data collection capabilities. Such efforts might include establishing formalized academic–public health agency research partnerships and a cadre of researchers and preassembled teams embedded in the response system—specifically within the incident management structure—and available to respond rapidly to public health emergencies (Lurie et al., 2013). In 2012, for example, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Strategic Sciences group was created to meet the immediate need for scientific information during an environmental disaster (DOI, 2020). In the case of PHEPR, CDC could build research expertise into the training for Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) officers, a subset of whom could then be deployed for the sole purpose of conducting PHEPR research during public health emergencies (CDC, 2020a). A benefit of doing so would be that EIS officers are often most knowledgeable about needs and opportunities in communities and have the relationships to carry out the necessary research and evaluations in real time. They can be mobilized quickly and are

positioned to have their results incorporated rapidly into guidance, funding, and translation efforts. With respect to data collection, the NIEHS DR2 program has a central repository1 of publicly available data collection tools, such as surveys, questionnaires, and protocols, that could be used to establish early baselines and cohorts for research.

Also important is to synergize and catalog past, ongoing, and future PHEPR-related research to avoid duplication (unless warranted) and reduce participant burden when research is conducted during or following a public health emergency. A database of PHEPR research studies categorized to facilitate analysis could be created, which would help foster research that would progressively improve PHEPR. Establishing and incentivizing partnerships and networks across research teams and institutions, other disciplines, and other organizations could also help coordinate research efforts.

Research involving human subjects during or following public health emergencies may pose ethical and data sharing challenges (Packenham et al., 2017). The Public Health Emergency Research Review Board was established in 2012 to provide centralized, rigorous, and expeditious reviews of human subject protections for HHS-conducted, -supported, or -regulated research studies addressing public health emergencies (HHS and NIH, 2020). This entity is currently under the auspices of the NIH network of institutional review boards (IRBs), and an IRB Authorization Agreement between NIH and the institutions conducting research is required (IOM, 2015). The NIEHS Best Practices Working Group for Special IRB Considerations in the Review of Disaster-Related Research has also been making progress in this area. The DR2 program has developed a pre-event generic protocol, the Rapid Acquisition of Pre- and Post-Incident Disaster Data (RAPIDD) protocol, for provisional approval by IRBs, which has been used by several universities. The objective of the RAPIDD protocol is to facilitate the collection of epidemiologic information and laboratory test results and the collection and storage of human biospecimens (Miller et al., 2016).

When it comes to research, public health agencies have different sets of concerns from researchers and institutions. A key issue is the security of confidential data and the privacy of subjects. Research during or following public health emergencies can also raise ethical challenges, including the burden on the population, potential harms, and the potential for therapeutic misconception (IOM, 2015). Further guidance and support are needed for academic entities and public health agencies to develop effective and efficient means for reviewing and addressing unique ethical issues in the conduct of PHEPR research, such as through pre-emergency review of standard protocols, training of IRB members on unique aspects of PHEPR research, and the establishment of specific review mechanisms for this research.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion: A National PHEPR Science Framework can establish the goals and objectives necessary to improve coordination, integration, and alignment among existing PHEPR research efforts, but will require adequate resourcing and oversight.

RECOMMENDATION 3: Develop a National Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response (PHEPR) Science Framework

To enhance and expand the evidence base for PHEPR practices and translation of the science to the practice community, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should work with other relevant funding agencies; state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies; academic researchers; professional associations; and other stake-

___________________

1 See https://dr2.nlm.nih.gov/tools-resources (accessed March 10, 2020).

holders to develop a National PHEPR Science Framework so as to ensure resourcing, coordination, monitoring, and execution of public- and private-sector PHEPR research. The National PHEPR Science Framework should do the following:

- Build on and improve coordination, integration, and alignment among existing PHEPR research efforts (e.g., the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ Disaster Research Response Program), and ensure integration of these efforts with the activities of the PHEPR evidence-based guidelines group proposed in Recommendation 1.

- Recognize and support PHEPR science as a unique academic discipline within the broader public health field to address the substantial need for research and diverse and qualified researchers.

- Create a common, robust, and forward-looking PHEPR research agenda that supports advancement beyond traditional epidemiological research to include research in the fields of social science, implementation science, complex interventions, and quality improvement, as well as intervention, operations, systems, and cost-effectiveness research.

- Support meaningful partnerships between PHEPR practitioners and researchers, and develop strategies to better ensure that PHEPR research is relevant to practice.

- Prioritize sustainable strategies and mechanisms for the translation, dissemination, and implementation of PHEPR research.

RECOMMENDATION 4: Ensure Infrastructure and Funding to Support Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response (PHEPR) Research

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with other relevant funding agencies, should ensure adequate and sustained oversight, coordination, and funding to support a National PHEPR Science Framework and to further develop the infrastructure necessary to support more efficient production of and better-quality PHEPR research. Such infrastructure should include

- sustained funding for practice-based and investigator-driven research that allows for the progression from exploratory to effectiveness to scale-up research and encourages researcher diversity;

- support for partnerships (e.g., with academic institutions, hospital systems, and state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies) to facilitate collaboration in research on the preparedness, response, and recovery phases of a public health emergency;

- development of a rapid research funding mechanism and interdisciplinary rapid response teams with applied research expertise (similar to CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service) for deployment to conduct just-in-time studies related to the implementation of PHEPR practices at the time of events; and

- enhanced mechanisms to enable routine, standardized, efficient data collection with minimal disruption to delivery of services (including preapproved, adaptable research and institutional review board protocols and a research arm within the response structure).

SUPPORTING METHODOLOGICAL IMPROVEMENTS FOR PHEPR RESEARCH

The results of the committee’s four evidence reviews highlight the paucity of research that has generated credible evidence to inform PHEPR practice (see Chapters 4–7). In some cases, the committee found few to no studies with which to address the questions of interest (e.g., no quantitative studies were included in the review for emergency operations coordination). In other cases, a sizable body of research exists, but the committee noted limitations in study designs (e.g., lack of baseline measurements or comparison groups, use of unvalidated or subjective and self-reported measures), execution (e.g., underpowered studies, high loss to follow-up), analysis (e.g., failure to conduct statistical tests or lack of statistical adjustment), or reporting of information (e.g., lack of details on the methodology, the PHEPR practice, population characteristics, other contextual factors, and outcomes). Some research methods were also poorly matched to the research questions they were intended to address. To help ensure that future studies yield results from which stronger conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of PHEPR practices, future investments in PHEPR research will need to remedy these common methodological shortcomings. Standards, guidance, and incentives can help raise the quality and evidentiary value of research in the PHEPR field.

Common Evidence Guidelines

Federal agencies can have a significant influence on the generation of the evidence base for practice (Maynard, 2018). In fields other than PHEPR setting priorities and standards for research and using them to guide funding decisions has improved the quality and usefulness of the evidence base. An example is the response of the education research field to shifts in funding priorities to align with agency evidence agendas and guidelines, which began in 2002 with the creation of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) within the U.S. Department of Education.2 Early on, IES established evidence guidelines for causal inference studies; a system for sourcing, grading, and synthesizing evidence; a web-based clearinghouse for evidence reviews; and an active program of funding for professional development (pre- and postdoctoral training grants; professional meetings and association development). These efforts resulted in a dramatic shift in the methodological rigor of education evaluations (Whitehurst, 2018).

Similar improvements could be achieved in PHEPR by drawing on these experiences in other fields to enact policies and practices that can improve how PHEPR research is conducted, disseminated, and used (IES and NSF, 2013). The goal is to ensure that scarce evaluation dollars are used most productively to advance the evidence available to inform policy and practice. Achieving this goal necessitates careful balancing of several factors: the importance of the questions studied, the rigor with which the questions can and will be studied, the timeliness of the research findings, and the accessibility and usability of the findings. Tiered evidence standards for grantmaking can be a useful mechanism to guide funding decisions, as they allow federal agencies to award smaller amounts to promising concepts and larger amounts to practices grounded in strong evidence of success, encouraging innovation while still rewarding programs with robust research backing (GAO, 2016).

Going forward, the PHEPR research field will need to have clear guidelines and standards for evaluation methods and study designs that will produce credible answers to various types of questions of importance to the field. The objective is to encourage a balance

___________________

2 Education Sciences Reform Act. HR 3801, Section 116. 107th Cong. (January 23, 2002).

of research throughout the knowledge-building continuum, from basic science through effectiveness trials and modeling studies, and to foster rather than stifle research innovation.

Guiding the Use of Different Types of Research Methods and Approaches

Well-crafted guidance will incorporate the full spectrum of research methods, which may range from exploratory case studies to RCTs and modeling studies for evaluating PHEPR practices. The PHEPR research field would be strengthened by creating a unified taxonomy of research methods, accompanied by guidelines for judging the credibility of study findings intended to address various types of questions. A first step in developing this guidance will be to identify the various genres of PHEPR research, and for each genre describe its purpose (i.e., how that type of research contributes to the evidence base) (see Annex 8-1). It will also be important for each genre of research to be supported by theoretical and empirical justifications when possible, and to adhere to established expectations for research design, methods, and products of the research. Expectations will need to be established as well for review of the products of each type of research (i.e., what information is required to judge the credibility and applicability of the findings and how that information can be judged).

While acknowledging the value of randomization for demonstrating a causal link between interventions and outcomes, the committee recognizes that it is difficult, if not infeasible or inappropriate, to implement RCTs for some PHEPR practices, particularly in the context of a real public health emergency. As discussed in Chapter 3, other study types (e.g., quasi-experimental study designs) may provide credible estimates of a causal impact (or lack thereof) when PHEPR practices are evaluated. Table 8-2 describes the strengths and limitations of common study designs for quantitative impact evaluation with applicability to PHEPR.

Other experimental study designs have begun to emerge that may also present opportunities for PHEPR research. Adaptive platform trial designs, such as the vaccine trial proposed during the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak, allow for flexibility along the timeline of an event, with interim analysis of data to enable investigators to determine whether to continue moving forward, change course, or divest more rapidly from interventions that are not showing promise (Berry et al., 2016). Pragmatic trials evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in real-life routine practice rather than the highly controlled conditions typical of experimental research studies (Ford and Norrie, 2016; Patsopoulos, 2011). This design incorporates more real-world evidence into controlled trials, allowing for a broader environment for testing, as well as greater generalizability of findings. A stepped wedge cluster design is a type of pragmatic trial used to evaluate the efficacy of service delivery interventions. This type of design may be a good option when operating within logistical or political constraints and has been used in a variety of areas, ranging from vaccine development to social policy and criminal justice (Hemming et al., 2015).

On the other hand, the committee encourages the PHEPR field to move beyond experimental study designs and consider a broader range of methods for exploring what works (and when, why, and for whom). Many PHEPR practices are designed to improve outcomes, particularly systems-level outcomes, in complex settings in response to unpredictable events. PHEPR practitioners and researchers are often interested in whether a practice made a difference or what would have happened had it not been implemented (e.g., what would have happened had the public health emergency operations center not been activated). Qualitative research methodologies (e.g., ethnographic observations, interviews, and focus group discussions) can inform why and how PHEPR practices may or may not be effective (Teti et

| Study Design | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | Provides the most unbiased, robust, and reliable estimates of the effectiveness of a PHEPR practice, which gives confidence that any measured differences between groups are due to the intervention. Depending on the sample size and diversity, it may be possible to conduct sub-group analysis to determine whether impacts vary by conditions in the implementing sites (e.g., urban and rural, diversity of languages spoken by residents) that influence the effectiveness of the PHEPR practice. |

It is often difficult to conduct an RCT at the community or national level, which is often the target of PHEPR practices.

Results from a simulated trial may not mirror those in a true emergency, and it may not be feasible to conduct an RCT during a public health emergency. If there is a desire to conduct an RCT during an emergency, completing the study requires waiting for emergencies to occur. Testing the differential effectiveness of strategies in real emergencies introduces uncertainties in the timeframe, cost, and context for the study. It may be costly to recruit the sample for the study, and it may be difficult to persuade decision makers of the benefits of this design given political and ethical issues concerning randomization. |

| Quasi-experimental study (matched comparison group study, interrupted time series, regression discontinuity design, multivariate analysis) | Provides reasonably strong evidence of the relationship between the PHEPR practice and outcomes measured. It is a powerful method for exploring the impact of a PHEPR practice when randomization is not possible. It can be applied to large communities, and launching such a study may be more feasible than an RCT close to the time of an emergency, which would improve the ability to collect reliable data prior to the emergency. |

There could be systematic differences between the jurisdictions implementing the PHEPR practice that are not captured in the data, and therefore that cannot be controlled for in the analysis. This could result in less reliable findings.

Matching techniques require a great deal of data, and the study could require considerable resources (time and cost) to identify jurisdictions that had implemented the PHEPR practices of interest and collect the data. These designs require complex analytical work and specialized knowledge. |

| Pre-post comparison design |

For studies based on simulated emergency situations, comparison of outcomes pre and post provides plausible indications of whether the PHEPR practice was implemented and whether outcomes changed as a result. In cases in which it is possible to measure outcomes for multiple time periods prior to and after implementation of the PHEPR practice, it is possible to compare not only differences in outcomes immediately before and after the event but also differences in trends before and after.

This design may be the most feasible option given that it requires relatively little time and money, depending on the outcomes of interest and the cooperation of practitioners in the jurisdictions selected for study. Some outcomes of interest may be sufficiently predictable over time that observed shifts after implementation of the PHEPR practice will have high credibility. |

There are significant threats to internal validity, but a study of this type could provide preliminary evidence of effectiveness. Changes may be occurring in the study sites between the pre and post periods, such as the adoption of other PHEPR practices or staff turnover. For some outcomes, there is likely to be considerable variation that cannot be explained by contextual factors, and it may be difficult or impossible to obtain reliable and consistent measures of the outcomes of interest through existing records or recall and reconstruction. |

al., 2020). A range of approaches are gaining recognition, such as realist evaluations3 and qualitative comparative analyses,4 that acknowledge the complexity of causality (Blanchet et al., 2018). There is also defined guidance for evaluating complex interventions (e.g., the UK Medical Research Council, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute), but these concepts have yet to be fully adopted by the PHEPR research field (AcademyHealth, 2017; MRC, 2019; PCORI, 2019). Furthermore, as PHEPR research is transdisciplinary, design methodologies used in such fields as public health services and systems research, operations research, behavioral and social sciences, organizational research, and quality improvement can also provide evidence for understanding PHEPR practices. In particular, simulation-based research methods (e.g., tabletop exercises), systematic expert opinion methodologies (e.g., Delphi), and systems science approaches (e.g., social network analyses, causal process diagrams, adaptive systems theories, modeling, machine learning, and big data analyses) can provide insight on systems-level outcomes and the interdependent relationships among the many components of the PHEPR system. Overall, there are many rigorous methodologies from diverse fields that could be used to evaluate PHEPR practices, and the key takeaway is to match the study design appropriately to the research question to produce credible answers. Annex 8-1 provides a brief summary of genres of research, example research questions, and some appropriate methods.

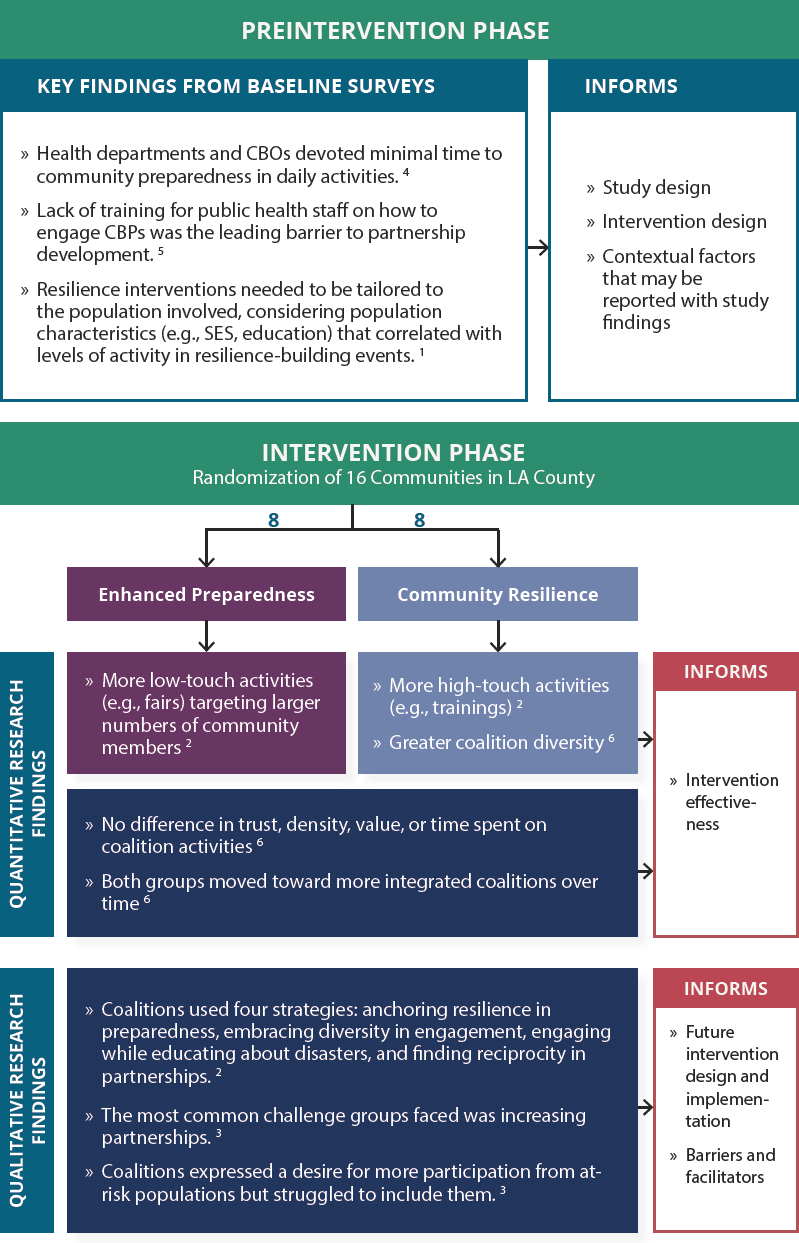

Comprehensive guidance would include suggestions for strategically mixing methods to improve both the design of intervention studies (e.g., through baseline studies conducted before a PHEPR practice is implemented) and understanding of the findings, including their breadth and limitations (postintervention). An example of such a strategic mixed-method approach in PHEPR is the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience (LACCDR) project5 (see Figure 8-3). The PHEPR field could benefit from conducting sequential or parallel studies focused on particular aspects of PHEPR practices. It is also important to note that the LACCDR project used community participatory methods, and the committee’s evidence review on engaging with and training community-based partners (see Chapter 4) found that community and stakeholder involvement in research and programmatic efforts from conceptualization to implementation may correspond with more effective engagement and training through enhanced inclusion, cultural acceptability, shared ownership, and capacity building of community members. Comprehensive guidance would incorporate such participatory methods, and also refer to their use in such emerging fields as engagement science (Dungan et al., 2019).

Standards for Reporting of Study Information

It is essential for all intervention studies to have well-articulated research plans that, when possible, are published before the analysis itself begins (Burlig, 2018; Lupia and Alter, 2014; Moravcsik, 2014). Such plans describe the study design, identify the primary and supplemental research questions to be addressed, provide background on the study setting,

___________________

3 “Realist evaluations are based on an assumption that projects and programs work under certain conditions and are influenced by the way that different stakeholders respond to them. Realist evaluations attempt to answer questions such as what works, for whom, in which circumstances, and why. They are designed to improve understanding about how development interventions work in different contexts” (INTRAC, 2017b).

5 See http://www.laresilience.org (accessed May 11, 2020).

4 “Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is a methodology that enables the analysis of multiple cases in complex situations. It can help explain why change happens in some cases but not others. QCA is designed for use with an intermediate number of cases, typically between 10 and 50. It can be used in situations where there are too few cases to apply conventional statistical analysis” (INTRAC, 2017a).

NOTES: The numbers shown on the figure denote the following sources: 1Adams et al., 2017; 2Bromley et al., 2017; 3Cha et al., 2016; 4Chandra et al., 2013; 5Chi et al., 2015; 6Williams et al., 2018. CBO = community-based organization; CBP = community-based partner; SES = socioeconomic status.

define the target population(s), and explain why the proposed program may change practice and improve decision making and outcomes for PHEPR practitioners or the community. They also detail the data collection plan, including measures to be used, and describe the analysis and reporting plans.

Given that PHEPR research funding and prioritization efforts are currently fragmented, disorganized, and inconsistent, there is no standardized peer-reviewed grant process, and as a result there are currently no specific standard guidelines or benchmarks for reporting the results of evaluations of the effectiveness of PHEPR practices. Reporting guidelines for health-related research have been developed for RCTs (Begg et al., 1996), observational studies in epidemiology (von Elm et al., 2007), systematic reviews of complex interventions (Guise et al., 2017a,b), studies of diagnostic accuracy (Bossuyt et al., 2015), qualitative research (O’Brien et al., 2014; Tong et al., 2007), implementation studies (Pinnock et al., 2015), and quality improvement studies (Ogrinc et al., 2016), among others (Hoffmann et al., 2014; Simera et al., 2008). Given the experience with a wide range of other types of research, it appears likely that developing, publishing, and disseminating tailored guidelines for PHEPR evaluations might well improve the reporting of such studies.

Federal agencies can support standardized reporting (e.g., through the development of guidance and standards and requirements linked to grants), which improves the usability of results and may over time result in efficiencies and cost savings (Maynard, 2018). Professional associations and journals also have important roles in the adoption of and commitment to reporting standards. PHEPR professional associations could establish the need and advocate for well-defined reporting standards, gather and review standards developed by other fields, draft standards for use by journals, and ensure that standards are shared and understood by the PHEPR research and practice fields. Journals play a vital role in communicating research findings to practitioners, as well as making information available to those in other sectors. By requiring the use of reporting standards, they can also promote the transparency and reproducibility of scientific research.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Conclusion: The lack of formal guidance and expectations regarding the various genres of PHEPR research has led to variable levels of credibility of the evidence produced. Given that evidence-based practices are dependent on existing research, efforts to delineate common expectations for PHEPR research need to be a priority to enhance the conduct of high-quality research and evaluation and help organize research investments.

RECOMMENDATION 5: Improve the Conduct and Reporting of Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response (PHEPR) Research

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the National Science Foundation, and other relevant PHEPR research funders should use funding requirements to drive needed improvements in the conduct and reporting of research on the effectiveness and implementation of PHEPR practices. Such efforts should include

- developing guidance on and incorporating into funding decisions the use of appropriate research methods as determined by the level of research (e.g., exploratory, effectiveness, scale-up) and type of research question(s) being addressed, includ

- ing but not limited to encouraging the use of concurrent comparison groups when feasible and assessment of baseline measures;

- establishing guidelines for evaluations using different designs and evidence streams and concepts from emerging evaluation approaches, such as complex intervention evaluations; and

- developing reporting guidelines, including essential reporting elements (e.g., addressing contextual factors, confounding factors, and negative results), in partnership with professional associations, journal editors, researchers, and methodologists for PHEPR intervention studies.

IMPROVING SYSTEMS TO GENERATE HIGH-QUALITY EXPERIENTIAL EVIDENCE FOR PHEPR

Public health agencies typically conduct after action reviews following real or simulated (exercise) public health emergencies in an effort to identify lessons learned and strengths and weaknesses of the response, and ultimately to improve emergency preparedness and response capabilities (Davies et al., 2019). The after action review process is an important source of experiential evidence in PHEPR and is the primary approach used by public health agencies to evaluate public health emergency response. In evaluation of the effectiveness of PHEPR practices, AARs offer the potential for improved understanding of context and implementation considerations that could be difficult to obtain through research. AARs can also be used to develop theories and logic models to inform future research. However, because they are not designed to be research, they are not without their methodological limitations. To help ensure that future AARs result in more useful and meaningful information for the evaluation of PHEPR practices (including the establishment of credible baselines for evaluation), it will be necessary to focus on strengthening methodological approaches, establishing mechanisms for analysis and dissemination of lessons learned from the reviews, and fostering a culture of improvement.

In the United States, several agencies and organizations that fund or oversee aspects of PHEPR, including CDC and ASPR, formally require after action reviews. The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP) developed a framework for agencies, including public health agencies, to use when developing, executing, and evaluating exercises. This program provides AAR templates and guidance to inform agencies in documenting strengths, areas for improvement, and corrective actions (FEMA, 2013). Because the framework is not organized according to the CDC PHEPR Capabilities, however, public health agencies have had to make major adaptations, such that the potential advantages of a standardized AAR have not been realized (Barnett et al., 2020). Thus, current reporting requirements and methodological standards for AARs lack clarity and uniformity. Moreover, evaluations are rarely conducted by independent evaluators with appropriate expertise (Davies et al., 2019; Gossip et al., 2017). AARs are typically reviewed and vetted throughout the agency or agencies that produced them before being submitted or shared with partners or the public, which may limit the candor of the information they contain (Gossip et al., 2017). The result is significant variability in the quality and reliability of AARs. The lack of consistent reporting requirements and variable report structures, together with limited CDC and public health agency resources, impedes the aggregation of AAR data and thus their use as a potential source of evidence for evaluating the effectiveness of PHEPR practices.

Limitations of AARs as a Source of Experiential Evidence for Mixed-Method Evidence Reviews

In recognition of the potential of AARs to inform the effectiveness and implementation of PHEPR practices in different contexts, the committee considered evidence from AARs in two of its evidence reviews. Davies and colleagues (2019) recently developed an appraisal tool with which to compare methodological reporting and document validity for AARs (see Box 8-2). To inform efforts focused on improvements needed to enhance the evidentiary

| BOX 8-2 | 11-ITEM TOOL FOR ASSESSING THE METHODOLOGICAL RIGOR OF AFTER ACTION REPORTS |

- Prolonged engagement with the subject of inquiry—Has the review included lengthy and perhaps repeated interviews with respondents, and/or days and weeks of engagement within a case study site or group?

- Use of theory—Has theory been used to guide sample selection, data collection, and analysis?

- Data selection—Has purposive selection been used to allow prior theory and initial assumptions to be tested or to examine “average” or unusual experience?

- Information sampling—Has the review gathered views from a wide range of perspectives and respondents rather than letting one viewpoint (person, organization, or specialty) dominate? Has it sampled enough people, places, times, etc., to ensure that the influence of these factors on the behavior and views of those people providing the information is minimized? Has sampling been expanded in the light of early findings?

- Multiple data sources—Has the review sought multiple information sources (documents, personal testimony, site visits) and collated multiple examples of each? For example, have duplicate formal interviews with all sampled staff been undertaken? Has the review used researcher observation and informal discussion, and have interviews been conducted with people in different roles and levels of seniority?

- Triangulation—Has the review looked for patterns of convergence and divergence by comparing results across multiple sources of evidence (e.g., across interviewees, and between interview and other data), among researchers, and across different methodological approaches? Has it also made comparisons within data (e.g., comparing different interview accounts)?

- Negative case analysis—Has the review looked for evidence that contradicts its initial findings, explanations, and theory, and refined them accordingly?

- Peer debriefing and support—Has the review included a step whereby the findings and reports have been reviewed by other researchers or investigators?

- Respondent validation—Have findings and reports been reviewed by respondents to check investigators’ interpretation of their input?

- Clear report of methods of data collection and analysis (audit trail)—Has the review kept and reported a full record of activities that is available to others and presented a full account of how methods evolved and were applied?

- Depth and insight—Has the review established the direct and indirect root causes and underlying contributory factors linked to errors, inaction, or latent failures?

SOURCES: Davies et al., 2019; ECDC, 2018.

value of AARs for future use, the committee commissioned a quality assessment of the 38 AARs included in its evidence reviews using this 11-item appraisal tool (Patel, 2019).6,7

Overall, the application of the tool to 38 AARs yielded low scores. Notably, consultants wrote two of the three highest-quality AARs, and AARs based on real events were of better quality on average than those based on exercises. The vast majority of AARs failed to provide a rationale for data selection, and more than half provided no detail on information sampling or multiple data sources, making it difficult to ascertain the appropriateness of the sample or sources used to inform the AAR findings. Practitioners were often surveyed for comments and observations, but the sample size of those practitioners, the timeline for data collection (immediate postevent versus after a reflection period), the information collected, and the format for collection varied widely and were rarely documented. Limiting samples to response leadership potentially skewed findings toward a leadership perspective at the cost of including feedback from staff engaged more directly in response operations. The grouping of leadership with general staff in feedback sessions could have discouraged staff from fully expressing any critiques they may have had regarding how leadership handled a response. Excluding communities from the after action review process also represented a missed opportunity to hear from diverse voices that might not have been reflected in the demographics of the leadership or staff. None of the AARs mentioned negative case analysis or respondent validation. Only three described peer debriefing and support; two of these were written by consultants, and one validated regional findings at the state level.

Overall, findings from applying the AAR quality assessment tool indicate a significant need to improve both after action review processes and the level of detail included in the reports themselves. It is unclear whether AAR authors omitted basic methodological information in a process that was otherwise rigorous, or if the reports would have scored low even if the requisite categories had been included.

In addition to these methodological shortcomings, the committee noted several other gaps and biases in its review of AARs and the AAR generation process that will need to be addressed moving forward:

- local political pressures and fear of judgment or retribution for reporting errors or negative outcomes;

- retrospective, subjective reporting based on the recall of participants, which may be influenced by the experience itself, pressures to “move on” and resume usual workflow, and limited roles in and siloed views of the activities;

- lack of methodological standards and tools for collecting, aggregating, analyzing, and disseminating information and reports;

- limited access to and the variable quality of data, information, and reports; and

- limited formal training, infrastructure, and resources to develop specialized personnel and/or programs to critically analyze AAR data and information in a culture of quality improvement.

___________________

6 This section draws heavily on a report commissioned by the committee on “Quality Assessment of After Action Reports: Findings and Recommendations,” by Sneha Patel.

7 The committee included 38 AARs in its evidence reviews. Approximately 61 percent of those reports were based on real events, and full-scale and functional exercises accounted for 16 percent and 21 percent of the reports, respectively. Hazards and threats included infectious diseases (e.g., H1N1, Ebola, hepatitis A), natural disasters, and human-made disasters (e.g., oil spills, explosions). Incident years ranged from 2009 to 2017 in 20 U.S. states. The AARs were all published either in the same year or the year following the real event or exercise.

Strengthening Methodological Approaches

Given the shortcomings discussed above, there is a clear need for CDC, in collaboration with ASPR and FEMA, to develop after action review policies and guidance that will ensure the capture of data relevant to the evolving response to a public health emergency and allow for in-depth analysis of the response. After action reviews can serve multiple purposes, including continuous quality improvement and, in some cases, accountability as part of grant requirements (Savoia et al., 2012; Stoto et al., 2013), and these purposes often require different methodological approaches to data collection, aggregation, and analysis. After action reviews are frequently completed by public health agencies themselves, and the methods used to collect information and data for the reports vary widely from agency to agency. In general, though, after action reviews use a wide variety of fairly common qualitative and quantitative methods, including surveys, interviews, focus groups or hotwashes, workshops, public forums, document reviews, and site visits (ECDC, 2018).

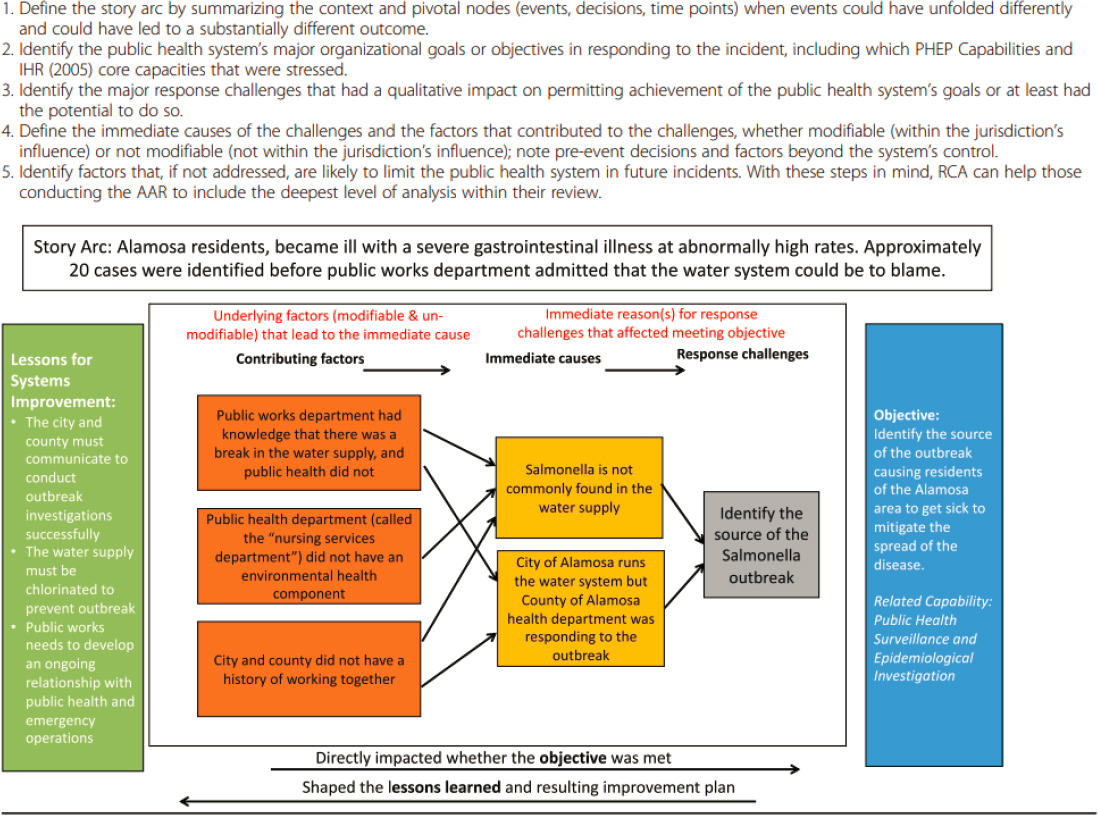

There is broad agreement that an after action review should seek to establish more than the immediate cause of response and recovery issues, and should analyze the factors behind the immediate causes, aiming to get to the root causes (Barnett et al., 2020; Davies et al., 2019; ECDC, 2018; Piltch-Loeb et al., 2014b; Singleton et al., 2014; Stoto et al., 2015, 2019) (see Figure 8-4 for an example depicting the steps of root-cause analysis). This systematic approach to root-cause analysis forms the basis of most approaches, such as peer assessment approaches8 and facilitated look-backs.9Gossip and colleagues (2017) note that public health agencies frequently utilize partner agencies and academic centers in the evaluation of exercises, but only rarely utilize this same expertise during or after a real-life response. Furthermore, while there is consensus that after action reviews should identify root causes, gaps remain in public health agencies’ use of this approach. An analysis of AARs conducted by Barnett and colleagues (2020) found several cases in which stated recommendations did not identify an underlying problem; an earlier analysis by Singleton and colleagues (2014) also highlighted the frequent failure of recommendations and corrective actions to include root-cause analysis.

AARs are at risk of the same biases as the qualitative and quantitative methods on which they rely, and findings from the committee’s commissioned quality assessment of AARs indicate that the reports typically omit the majority of important validity categories that could foster greater confidence in after action findings. Guidance aimed at improving after action review methods and the level of detail included in AAR methods sections is needed for both transparency and quality purposes, and AARs need to meet some minimum criteria concerning methods and reporting (Davies et al., 2019). The PHEPR field could benefit from drawing on the broader public health field to apply more rigorous evaluation processes when assessing lessons learned from public health emergencies. Training for evaluation participants, including academic programs in HSEEP certification and evaluation design, need to be encouraged and supported, if not required (Stoto et al., 2019). Standards and expectations regarding AARs could be strengthened by being integrated into PPHR (Summers and Ferraro, 2017). Similarly, PHAB could shape the evaluation of PHEPR by modifying its standards and measures to specifically include those that relate to PHEPR, thereby fostering efforts at quality improvement and evaluation (Brownson et al., 2018). Most important is for CDC and state,

___________________

8 The peer assessment approach employs an evaluation conducted by peers in similar jurisdictions. This approach offers the potential for objective analyses by PHEPR professionals and knowledge of the particularities of the system being assessed (Piltch-Loeb et al., 2014b).

9 The facilitated look-back approach uses a neutral facilitator and a no-fault approach to probe the nuances of decision making through moderated discussions (Piltch-Loeb et al., 2014b).

NOTE: AAR = after action report; IHR = International Health Regulations; PHEP = public health emergency preparedness; RCA = root-cause analysis

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Stoto et al., 2019.

local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) public health agencies, in addition to approaching AARs as an administrative requirement, to begin viewing them as a source of experiential evidence that could inform the development of evidence-based PHEPR practices and providing the necessary training, infrastructure, and resources to improve the quality of AARs produced.

Independent After Action Review Panel

According to Gossip and colleagues (2017), partnering with external organizations (e.g., peer agencies, consultants, academic centers) improves the depth and quality of documentation and assessments, as external organizations often have the requisite expertise and skills and capacity (e.g., time and personnel) to conduct or guide more rigorous evaluations. The United States has a strong history of creating objective, independent review panels (e.g., the National Transportation Safety Board and the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s National Construction Safety Team Advisory Committee), consisting of collaborative partners to develop guidelines, evaluate data and findings, and investigate incidents. These objective bodies have been proposed as a model for the PHEPR field (Barnett et al., 2020; Keim et al., 2019; Kirsch et al., 2018). These types of processes ensure objective expertise by eliminating the inherent biases of self-assessment and make use of consistent methods so that findings are comparable over time. Such a panel could review all events reaching the threshold of a Stafford Act or Public Health Service Act event. This process could be conducted by a newly established group, through existing professional associations, accrediting bodies, or regional academic partnerships and networks.

Essential Core Elements of a PHEPR AAR

To enable aggregation and analysis of AAR data for use as a potential source of evidence on the effectiveness of PHEPR practices, it is essential to define the core elements of a PHEPR AAR that builds on the existing HSEEP format but embraces more of a public health perspective. These elements would include a standardized core dataset and root-cause analysis framework that ultimately could be used not only by one jurisdiction, but also across jurisdictions for purposes of aggregation, trend analysis, and systemwide comparison (see Box 8-3 for the committee’s suggested elements for such an AAR template). Focusing on system-level root causes rather than specific problems would help make the experience more broadly applicable (i.e., enhance generalizability) (Stoto et al., 2019). An executive summary with high-level findings for each AAR would aid further in developing the empirical evidence base. An online platform prepopulating evaluation forms for practitioner-specific reporting objectives could also be developed (Agboola et al., 2015). Such a platform, with standardized questions at the national level, would assist practitioners in completing evaluations, integrate consistent measures into the review process, and aid in conducting trend analyses over time.

Establishing Mechanisms for Analysis and Dissemination of Lessons Learned from AARs

Proper conditions for establishing the utility and credibility of AARs as a less biased source are needed to improve the utility of these reports in evidence reviews and guidance for practical decision making. Improved mechanisms for public sharing of lessons learned from AARs, such as an enhanced national AAR repository, that specifically preclude the use of the reports for punitive purposes would foster more accurate and reliable information.

| BOX 8-3 | THE COMMITTEE’S SUGGESTED ELEMENTS FOR A PHEPR AFTER ACTION REPORT TEMPLATE |

- a structured executive summary focused on what agency leadership would find most useful for decision making to inform current and future responses (and designed to be database searchable with a maximum word count);

- a word-limited abstract to provide an overview of the incident, important contextual factors, the tested PHEPR Capabilities, and key findings;

- an acronym and definition list, as jurisdictions often use terms differently;

- a background section that provides enough information for someone with an outsider’s perspective to understand the context of the situation and event without being overburdened by unnecessary details;